Abstract

Social media constitutes a pervasive communication media that has had a prominent role during global crises. While crisis communication research suggests that individuals use social media differently during a crisis, little is known about what forms of engagement behavior may emerge and what drivers may lead to different forms of social media users’ engagement behavior toward a global crisis. This study uses netnography and in-depth interviews to explore social media users’ behavioral manifestations toward the COVID-19 crisis; thereby, we identify nine forms and six drivers and develop a framework of relationships between these forms and drivers. Those findings provide a better understanding of social media engagement toward the crisis from individual users’ perspectives, which helps commercial and non-commercial marketers to determine the users’ sentiments and reactions reflected in their engagement behaviors, hence, communicate more effectively and in a more engaging way during and beyond a global crisis.

Keywords: COVID-19, Crisis communication, Engagement, Facebook, Social media, Twitter

1. Introduction

Social media is extensively used as a relevant media channel in crisis communication and management (Chamberlain, 2020, Fraustino et al., 2012). Social media fosters collective action and organization, both in communities and professional networks, to collaborate and deal with the crisis's impact (Tsui, Rao, Carey, Feng, & Provencher, 2020). Monitoring social media during a crisis can help social media and communication managers determine the user’s sentiments and reactions and identify potential shifts in users’ behavior (Coombs & Holladay, 2012). Given the increasingly important role social media plays during a crisis, it is essential to deeply understand social media use during a crisis.

The COVID-19 pandemic exemplifies one of the extreme forms of global crisis, which continues to have an unprecedented impact on the global population (Donthu and Gustafsson, 2020, Kabadayi et al., 2020) with severe economic and social consequences worldwide that are likely to continue for many months, if not years (Weforum.org. , 2020, Int, 2019). This is a sharp reminder that such a crisis caused by pandemics will continue to happen in the future and may have more permanent effects on how social media users behave in the future (Donthu & Gustafsson, 2020).

Particularly during national lockdowns and social distancing, people’s ability to socialize normally was curtailed (Hollebeek et al., 2020, Nabity-Grover et al., 2020). On top of the need for information to determine the magnitude of the crisis, this lack of socialization elevated social media's role in most people’s lives; feelings of loneliness and isolation increased social media use (Donthu and Gustafsson, 2020, Roose, 2020). Social media has become the main mode of contacting or socializing with others and even essential services (Donthu & Gustafsson, 2020). Consequently, social media platforms have seen a 61% increase in usage during the current crisis (Holmes, 2020), and changes in media consumption and social media engagement behavior for both users and brands have been witnessed (Arens, 2020, Bern, 2020).

Prior crisis communication research suggests that individuals use social media differently in times of crisis with drivers specifically stemming from the crisis such as seeking emotional support, humor, self-mobilizing and maintaining a sense of community (Fraustino et al., 2012, Sweetser and Metzgar, 2007). Recent engagement research suggests that users' engagement behaviors are expected to differ during and beyond a period of great uncertainty and social disruption (Karpen & Conduit, 2020).

To maintain relevance in these unprecedented times, businesses are considering new approaches to engage their audience to help deliver messages and engage in conversations that are considered valuable and helpful (De Valck, 2020, Karpen and Conduit, 2020). Brands need to consistently review and reprioritize their social media marketing strategy (Arens, 2020, He and Harris, 2020, Nabity-Grover et al., 2020). Recent research suggests that, more than ever, social media posts should be user-centric and not producer-centric (De Valck, 2020, He and Harris, 2020) in order to embrace social media's communal logic, thereby understanding how social media users engage with other users toward the crisis (De Valck, 2020), hence, determine the user’s sentiments and reactions reflected in their engagement behaviors (Coombs & Holladay, 2012).

Although prior engagement research has paid specific attention to user’s engagement behavior in online and social media contexts (e.g., Azer and Alexander, 2018, Blasco-Arcas et al., 2020, Bowden et al., 2017, Brodie et al., 2013, Hollebeek et al., 2014, Jaakkola and Alexander, 2014, Naumann et al., 2020), the extant typologies are brand-related. Even if they reflect a C2C interactive relationship, the brand/product/service is what the users are interacting about (Brodie, Hollebeek, Jurić, & Ilić, 2011). Therefore, it is unclear which forms of engagement behavior will emerge when the focus of engagement is the global crisis. The unique characteristics of this pandemic, such as its global scope, high levels of uncertainty, a clear shift towards online media due to the higher perceptions of immediacy and urge for updates, and the need for connectedness due to social distancing and lockdown measures, create a clear and urgent need for a better understanding of social media users’ engagement behavior about the global crisis (Donthu & Gustafsson, 2020).

This study seeks to fill a gap in research around social media users’ engagement behaviors toward a global crisis. The study focuses on C2C engagement behaviors, elevated in crisis communication, to conceptualize forms and drivers of social media users’ engagement behavior toward a global crisis such as the COVID-19 pandemic. This study builds on both the crisis communication and customer engagement literature and implements an extensive netnography of user-generated content across Twitter and Facebook and in-depth interviews with social media users. Ultimately, this study conceptualizes a typology of nine forms and five drivers of social media users’ engagement behavior toward the global crisis and offers a framework of relationships between these forms and drivers. This study contributes to theory by bridging a gap between the engagement and crisis communication research bases. Furthermore, building an understanding of the relationship between forms and drivers of engagement is necessary to show what drives social media users to engage in specific forms, which, in turn, facilitates the development of social media marketing strategies during a crisis.

2. Global crisis and social media: a user perspective

2.1. The role of social media during crisis

According to the National Science and Technology Council, a global crisis is a serious disruption of the functioning of a community or a society, causing widespread human, material, economic or environmental losses that exceed the ability of the affected community or society to cope using its resources (SDR.gov, 2005). In a crisis, people take in, process and act on information differently than during normal times (CDC.gov., 2019, Fraustino et al., 2012). This is because people may experience a wide range of emotions and psychological barriers that can interfere with how they react and behave during a crisis (CDC.gov, 2019). Consequently, communications during a crisis should take into consideration certain patterns that affect people’s behavior, such as uncertainty, anxiety, fear, panic, hopelessness, and denial (Addo et al., 2020, CDC.gov., 2019), in addition to positive ones such as coping, relief, and elation at surviving the crisis (Bern, 2020).

Crisis communication is a significant area of multi-disciplinary research. It deals with crisis information disseminated to the public by governments, emergency management organizations, crisis responders, and crisis information created and shared by individuals (Fraustino et al., 2012). Crisis communication literature highlights the central role of social media in how crises are discussed, framed, and perceived (Jin et al., 2012, Zhang et al., 2018). Given the increasingly important role social media play during a crisis, it is essential to understand what is known about social media use during a crisis and what remains to be tested. Otherwise, businesses, policymakers and emergency managers risk making crisis communication decisions based on intuition or inaccurate information.

Social media has changed how individual users experience a crisis, becoming an important communication channel for users to communicate (Jung et al., 2018, Park, 2018). During a crisis, users turn to social media platforms to seek information or cope with uncertainty (De Meulenaer, De Pelsmacker, & Dens, 2015). In addition to seeking information, users turn to social media to cope, look for support, and share their emotional states (Brummette & Sisco, 2015). In this way, crises are now framed by people’s reactions, comments, and posts on social media, at least as much by organizational stakeholders, such as the mass media. While there is a clear interest in understanding the role of social media in a crisis, most of the contributions so far have focused on the organizational side, looking at how organizations can communicate more effectively under these situations (Wang & Yang, 2020). The existing evidence from individual users or a citizen perspective is still scarce. There is a lack of understanding regarding how social media users’ engagement behavior about crises at a broader level and not only in social media interactions with specific organizations.

The COVID-19 pandemic exemplifies a global crisis with severe economic and societal consequences across the globe (Kabadayi et al., 2020). The COVID-19 pandemic crisis has also impacted how people interact and relate to others (Nabity-Grover et al., 2020). In most countries, local governments introduced quarantine and lockdown measures to enforce social distancing and restrict unnecessary trips outdoors (Donthu and Gustafsson, 2020, Hollebeek et al., 2020, Kabadayi et al., 2020). Such changes to people’s lives were abrupt and indefinite in length; social isolation extended into several months, and social distancing rules were ever-evolving (Nabity-Grover et al., 2020).

Recent market research shows that people worldwide have eased the transition to social distancing by spending more time on social media platforms (Nabity-Grover et al., 2020). Social media platforms generally have seen a 61% increase in usage (Holmes, 2020). Facebook and Twitter show more than a 40% increase worldwide from February to March 2020; and between February and April 2020, people spent 13% more time on YouTube, 16% more time on TikTok, and 31% more time on the social gaming apps (Holmes, 2020, SocialMediaWeek.org., 2020).

COVID-19 has also changed social media engagement behavior for both brands and users (Arens, 2020, Bern, 2020). The worldwide pandemic has influenced brands’ social media strategy and performance (He & Harris, 2020). This can be seen in various areas, including lower demand for paid ads on Facebook and increased organic content performance (Bern, 2020). Due to lockdown and social distancing measurements, users have more time to consume and engage with social media content, creating new opportunities for marketers to create engaging content (Bern, 2020, Nabity-Grover et al., 2020). However, given the fluid situation around COVID-19, the only certainty is that users’ behaviors will continue to change dramatically over the next few months (Arens, 2020).

According to recent market research, brands will continue to face challenges, highlighting the need to consistently review and reprioritize their social media marketing strategy (Arens, 2020, He and Harris, 2020, Nabity-Grover et al., 2020). Typically, marketers should relate their social media contributions to the real-time context; otherwise, they will not refer to the situation and seem misplaced (He & Harris, 2020). Similarly, trying to leverage a crisis for branding purposes can quickly be perceived as distasteful (De Valck, 2020). Recent research suggests that brands should consider complexities such as the user’s state as the situation continues (Arens, 2020) to deliver messages and engage in conversations that are considered valuable and helpful, thus coming out of the crisis stronger (De Valck, 2020). Specifically, prior research points to the fruitfulness of monitoring social media during a crisis; however, there is a lack of understanding of the pattern of social media users’ engagement behavior toward a global crisis and the specific drivers underlying these behaviors.

2.2. Social media users’ engagement behavior

User engagement has recently been the focus of attention for marketing planners. Being engaged ‘is to be involved, occupied, and interested in something’ (Higgins, 2006, p. 422). Engagement goes beyond mere participation and involvement, as it encompasses an interactive relationship with an engagement object (Brodie, Fehrer, Jaakkola, & Conduit, 2019), which involves voluntary and discretionary behavior toward the object (Jaakkola & Alexander, 2014). Engagement is considered a multidimensional concept comprising cognitive, emotional, and behavioral investment in specific interactions (Brodie et al., 2011, Hollebeek et al., 2021). This paper focuses on the behavioral manifestations of engagement consistent with previous engagement examinations in a social media context (Dolan et al., 2016, Van Doorn et al., 2010).

In the social media context, social media engagement behavior (SMEB) is referred to as behavioral manifestations with a social media focus resulting from motivational drivers (Dolan et al., 2016). It includes customers’ creation of, contributing to, or consuming content within a social network (Dolan, Conduit, Frethey-Bentham, Fahy, & Goodman, 2019; Van Doorn et al., 2010). The degree of engagement itself varies, falling on a continuum from basic forms of engagement (e.g., “liking” a page on Facebook) to higher forms of engagement depicting users participation in co-creation activities (e.g., writing posts) (Azer and Alexander, 2018, Dessart et al., 2020).

Several authors have paid specific attention to user’s engagement behavior in online and social media contexts. Within these contexts, authors conceptualized the construct of engagement (e.g., Azer and Alexander, 2018, Blasco-Arcas et al., 2020, Bowden et al., 2017, Brodie et al., 2013, Hollebeek et al., 2014, Jaakkola and Alexander, 2014, Naumann et al., 2020) and identified different antecedents and outcomes (e.g., Azer and Alexander, 2020b, Blasco-Arcas et al., 2016, Dessart et al., 2016, Dolan et al., 2019, Harrigan et al., 2017, Hollebeek and Chen, 2014). However, the engagement literature typically focuses on the engagement interaction that occurs between the customer and the brand (e.g., Brodie et al., 2013, Hollebeek et al., 2019) or the interactions among customers but still maintains the focal object of engagement as the brand (e.g., Azer and Alexander, 2018, Vivek et al., 2012). It is unclear what sentiments and behavioral manifestations will manifest when the engagement object is the crisis itself.

During and beyond a period of great uncertainty and social disruption, users' engagement behaviors are expected to differ (Addo et al., 2020, Ali and Kurasawa, 2020, Karpen and Conduit, 2020). Social isolation may be harmful (Reeves, Carlsson-Szlezak, Whitaker, & Abraham, 2020); feelings of loneliness have, among other things, been connected to poorer cognitive performance, negativity, depression, and sensitivity to social threats (Donthu & Gustafsson, 2020). Accordingly, recent studies suggest that businesses should consider complexities reflected in their behavioral manifestations on social media (Arens, 2020). Therefore, it is important to understand the nature of the user’s engagement behavior on social media toward a global crisis, such as COVID-19.

In this paper, the engagement object that social media users interact about with other users is the global crisis. According to prior crisis communication research, when crises strike, social media audiences are involved, occupied, and interested in creating, consuming, and responding to information (Fraustino et al., 2012), which aligns with the notion of engagement according to Higgins (2006) – being involved, occupied, and interested in something and involves voluntary behavioral manifestations (creating and responding) about the crisis according to Jaakkola and Alexander, 2014, Dolan et al., 2016. Importantly, echoing actors’ investments of resources according to Brodie et al. (2019). To illustrate, COVID-19 impacts one’s basic cognitive processes, willingness to initiate action, emotions, and interaction (Muraven, 2012, van Grunsven, 2020). Lessening these challenging impacts entails investing resources by actors in the crisis (Finsterwalder & Kuppelwieser, 2020), and such investment comprises individual interactions (Brodie, Ranjan, Verreynne, Jiang, & Previte, 2021). These resources are cognitive (how an actor responds to the pandemic), psychological (elements of optimism and coping with the pandemic), physical (actor feeling energized in functional and instrumental activities of daily living), emotional (overcoming feelings of fear and insecurity), and social (the social networks available to an actor) resources.

Prior research suggests engagement objects may include other customers, firms, or other non-human actors (Brodie et al., 2019, Ng et al., 2020, Storbacka, 2019). However, the engagement object can also be a crisis, a cause, or an idea. For instance, during the West African Ebola crisis of 2014–2015, the religious leaders' engagement about the crisis manifested in advocating hygiene practices (e.g., handwashing and safe burials) was considered a turning point in the epidemic response (Bavel et al., 2020). Moreover, community engagement with the Ebola crisis was manifested in social and behavioral change communication (Gilmore et al., 2020). Such community engagement involved multiple actors and took multifaceted approaches for prevention and control. Engagement object could also be a cause; for instance, according to Brodie et al. (2019), the engaged actors (e.g., volunteers, social workers, government bodies, and the public) in the network St. Vincent de Paul Society brings together are cognitively and emotionally invested in the cause of this global not-for-profit organization. The engagement could be about an innovative idea manifested in creating ideas on an innovation platform, echoing actors’ cognitive engagement state (Brodie et al., 2019).

The concept of social media user’s engagement behavior toward a global crisis is currently undefined; by theoretically adapting the extant definition of SMEB (cf. Dolan et al., 2016), this paper defines it as social media users’ behavioral manifestations that have a global crisis focus and resulting from drivers. This definition will guide the empirical inquiry.

2.3. Forms and drivers of social media user’s engagement behavior

Prior research draws together a range of user engagement behavior within social media and virtual brand communities, identifying various engagement behaviors that users exhibit in social media platforms, namely, co-creation, positive contribution, consumption, dormancy, detachment, negative contribution and co-destruction (Dolan et al., 2016). While on online brand communities (OBCs), engagement behaviors such as constructive, learning, advocating, socializing, boycotting, recommending and warning behaviors are captured (Azer and Alexander, 2018, Bowden et al., 2017, Brodie et al., 2013, Jaakkola and Alexander, 2014, Naumann et al., 2017).

Notably, the extant typologies of engagement behavior reflect what customers do on social media platforms and OBCs, rather than how they engage in different engagement behavior forms. For example, they engage in OBCs by learning, socializing, recommending a product or service or brand to others, boycotting a brand community, warning or mobilizing others against it (Azer and Alexander, 2018, Bowden et al., 2017, Brodie et al., 2013). Similarly, on social media, the typology of SMEBs reflects users’ engagement behavior via social media about a focal brand. For example, customers can create or consume content and contribute negatively or positively about a brand (Dolan et al., 2016). However, it is unclear which forms of engagement behavior will emerge when the focus of engagement is the global crisis. Recent research calls for studying engagement objects beyond those commonly investigated (Ng et al., 2020) as the extant typologies are brand-related even if they reflect a C2C interactive relationship; the brand/product/service is what the users are interacting about (Brodie et al., 2011).

Although the SMEB typology suggests that users may engage in negative or positive contributions (Dolan et al., 2016), it is unclear what forms of behaviors are considered negative or positive contributions. In other words, it is more valuable to capture not only what customers say (negative or positive contributions) but also how they say it (Hennig-Thurau et al., 2010), thereby providing measurable components (Mazzarol, Sweeney, & Soutar, 2007). Recent business research during COVID-19 addressing consumer social media behavior's evolution identified entertainment and informational content (e.g., COVID-19 news and gathering food and supplies) (SocialMediaWeek.org, 2020). Nevertheless, these are kin to social media content rather than behaviors. It would be more valuable to capture how users engage about the crisis using entertainment content, what sentiments manifest, and in which category of entertainment. Moreover, sharing news to inform others is not like self-mobilization to support others by gathering food and supplies. Such a phenomenon involving groups on social media created around user needs by the users themselves is associated with COVID-19, which has revealed social media networks' power in a crisis (Chamberlain, 2020).

Most of the extant research has identified different motives to engage in online contexts. These include concern for others, self-enhancement, advice-seeking, realizing social/ economic/hedonic benefits, social/personal integration, helping the company, utilitarian motive, the pleasure derived from sharing information, a desire to help others, social interaction, information seeking, pass the time, entertainment, relaxation, communicatory utility, convenience utility (Balaji et al., 2016, Chi, 2011, Hennig-Thurau et al., 2004, Juric et al., 2016, Ranaweera and Jayawardhena, 2014, Whiting and Williams, 2013, Zeelenberg and Pieters, 2004). However, these are all motives to engage in or adopt social media platforms. They are unique individually-based motives to generally engage in online activities (Hennig-Thurau et al., 2004) rather than drivers that may drive social media users to engage in a specific form of engagement behavior (Van Doorn et al., 2010), which this study focuses on conceptualizing especially when the focus of engagement is the global crisis.

In the engagement literature, studies suggest that customers are triggered by their feelings of hatred, anger and stress towards a service provider, brand or firm (Bowden et al., 2017, Juric et al., 2016, Naumann et al., 2017). Furthermore, a typology of triggers provided by Hollebeek and Chen (2014) that elicit customers to engage in positively (negatively)-valenced brand engagement based on favorable (unfavorable) perceived brand action, quality, value, innovativeness, responsiveness, and delivery of promises. Similarly, Azer and Alexander (2018) suggest that overpricing, deception, service failure, insecurity, and disappointment trigger customers to engage in negative engagement behavior about service providers in online contexts. Importantly, these are all predominantly relate to common times, and on top of that, these are all brand-related drivers.

Drawing from prior literature addressing media consumption and motivation in times of a crisis, such drivers differ from normal times and specifically when the focus of engagement is not the brand but the crisis itself. This is because, during a crisis, people may experience a wide range of emotions and psychological barriers that can interfere with how they behave during a crisis, hence what drives such behavior (CDC.gov., 2019, Van Doorn et al., 2010). Consequently, unlike normal times and brand-related experiences, during a crisis, certain patterns affect people’s behavior, such as uncertainty, anxiety, fear, panic, hopelessness, and denial (Addo et al., 2020, CDC.gov., 2019), in addition to positive ones such as coping, altruism, relief, and elation at surviving the crisis (Bern, 2020).

The media consumption and motivation literature suggests that social media users often use social media to meet specific informational and emotional needs stemming from the crisis (Fraustino et al., 2012). Such drivers may include seeking emotional support, humor, self-mobilizing (organize emergency relief and ongoing assistance efforts), maintaining a sense of community (Procopio and Procopio, 2007, Sweetser and Metzgar, 2007), coping, and altruism (CDC.gov, 2019). However, drivers specifically stem from the crisis itself, and COVID-19 is an unprecedented crisis with unique characteristics, such as its global scope, heightened levels of uncertainty, an explicit shift towards online media due to the higher perceptions of immediacy and urge for updates, and the need for connectedness due to social distancing and lockdown measures (Donthu & Gustafsson, 2020). Accordingly, drivers that stem from such an unprecedented global crisis are worth further exploration.

Importantly, none of these studies has identified how these drivers are related to various forms of social media users’ engagement behavior toward the global crisis. Understanding the relationship between forms and drivers is necessary as it shows what drives users to engage in specific forms of behavior, which in turn facilitates the development of strategies for social media marketing during a crisis. As such, these relationships will guide marketers to design relevant content that appeals to their customers amidst crisis and ultimately facilitates engagement.

3. Methods and data collection

To better understand the engagement phenomenon about this unprecedented global crisis and capture user’s sentiments and behavioral manifestations about such a crisis, netnography and depth-interviews qualitative techniques were adopted. Netnography was selected to provide a typology of the forms and drivers of social media users' engagement behavior about the global crisis, followed by interviews to corroborate the findings. Compared to other qualitative research techniques, the unique value of netnography is that it excels at telling the story, understanding complex social phenomena, and assists the researcher in developing themes from the users' points of view (Kozinets, 2010). Multiple authors have advocated using netnography when studying online user-generated content in business research (Vo Thanh and Kirova, 2018, Weijo et al., 2014) and engagement research (Azer and Alexander, 2018, Brodie et al., 2013, Hollebeek and Chen, 2014).

In line with Kozinets (2010) recommendations for the site selection and to ensure diversity of contexts and robustness of findings, Twitter and Facebook were selected. Both social media platforms are active and have recent and regular communications. Facebook and Twitter are among the biggest social network worldwide. Almost 2.5 billion and 330 million monthly Facebook and Twitter active users, respectively (Statista.com, 2020). Moreover, they have a substantial and critical mass of communicators, in addition to the high levels of interactivity and flow of communications between users. Furthermore, the percentage of global populations using Facebook (26.3%) and Twitter (28%) (Statista.com, 2020) satisfies the heterogeneity aspects of the chosen contexts for the study (Kozinets, 2010).

To strengthen the stability and validity of findings, using the NCapture facility of Nvivo pro software, we extracted 20,000 Facebook and Twitter posts from January to May 2020 that used the most frequent hashtags, according to Ipsos.com. (2020). These hashtags are #wuhanvirus #coronavirus, #covid19, #quarantine, #lockdown, #stayathome, #stayhomesavelives, #workingfromhome. Following recommendations for netnographic studies, it was deemed appropriate to copy publicly shared archival data comprising all posts for this period and then filter this for relevance (Kozinets, 2010). Publicly communicated online messages are open to researchers, and, legally, it is the user’s responsibility to identify what information to share publicly on social media (Kozinets, 2010, Langer et al., 2005). Accordingly, only public posts in English were included, also to avoid redundancy, a filtration option of NVivo automatically excluded all retweeted posts. The research focuses on individual users, not firms, organizations, governments, sponsored ads, or ads; accordingly, ads, businesses, governments, and organizations' posts were manually excluded. Hence, we proceeded with 4000 relevant Facebook (800) and Twitter (3200) posts for analysis.

To ensure the relevance of the data to the stated research aim; the theoretically informed definition of social media users engagement behavior about global crisis guided the study in addition to consulting research papers that address textual discourse (e.g., Broadbent, 1977, Giora, 2002, Polanyi and Zaenen, 2006) to aid the identification of the valence of behavior. To provide empirical definitions for the conceptualized forms of behavior, Jaakkola and Alexander (2014) definitions of the forms of customer engagement behavior were theoretically adapted; thereby, the definitions of the conceptualized forms in this study reflect social media users’ contributions that have a global crisis focus, occur in interactions with other actors. Furthermore, the extant conceptualization of SMEB by Dolan et al. (2016) was employed, focusing on the positive and negative contribution classification. Besides, model of C2C engagement behaviors forms and drivers by Azer and Alexander (2018), research on crisis communication and social media consumption and motivation in times of a crisis were consulted and recent COVID-19 market research addressing changes in social media users/consumers' behavior.

Followed by the netnographic study, semi-structured interviews via Zoom and Facebook Messenger were conducted, each took around 40 min, with a sample of 50 (females 60.5%, average age = 25.5 years, SD = 1.30) participants randomly selected from those who shared the COVID-19 posts this study sampled from Twitter and Facebook. The participants' random selection involved picking those who engaged in at least one of the nine forms discovered in the netnographic phase, especially recently posted, to ensure the drivers are still fresh in their minds. Out of 70 participants approached, 50 agreed to participate. The participants were approached via Facebook and Twitter messaging facilities, and when they agreed to participate, they were asked to either use Facebook messenger or Zoom to have a video interview. The participants were asked about their recent COVID-19 post, then asked to discuss their behavioral manifestation aspect in greater depth. For example, when ‘supporting,’ ‘commending,’ or ‘informing’ is mentioned, the participant was asked to discuss that aspect of behavioral manifestation deeper. They were then asked what drove them to write these specific posts, which permitted the emergence of drivers' key themes. These in-depth interviews act as a means of data triangulation, thus corroborating the netnographic findings and providing a framework of forms-drivers relationships.

4. Interpretation and analysis

Thematic analysis is conducted using open and axial coding (Corbin & Strauss, 2008). Open coding involves breaking data apart and considering all possibilities within, followed by coding conceptual labels on the respective data. Axial coding involves ‘crosscutting or relating concepts to each other’ (Corbin & Strauss, 2008, p. 195). The open/axial coding represented an iterative process of going back and forth between extant literature, data, and the emerging theory (Danneels, 2003).

This study initially identified themes inductively from the raw data and deductively from the literature review on engagement and crisis communication. To illustrate, initially emerged themes during open coding were supportive, humorous, commending, criticizing, inspiriting, gaming, and dispiriting. We used to code gloating as criticizing, but by applying scrutiny, referring to psychology literature, gloating differs from mere criticism, which matches the nature of the coded pieces of gloat. Additionally, by applying scrutiny to the themes generated in open coding, we found a difference according to crisis communication literature between supportive and informative, also in engagement literature (cf. Azer & Alexander, 2018). Hence, further inspection of the users’ posts showed a difference when they are just sharing information and when they are mobilizing themselves to support others.

Axial coding involves looking at how larger pieces of data fit, group, and cluster together (Corbin & Strauss, 2008). Therefore, themes initially emerged using open coding gained further scrutiny and/or linking to social media users' engagement behavior in a global crisis and, specifically, to positive and negative contributions during axial coding. This process corresponds to the analytical sequence of abstracting and comparing, followed by checking and refinement, which is also recommended for netnographic data analysis (Kozinets, 2010, Miles and Huberman, 1994).

To illustrate, during data analysis, themes emerging from the netnographic study were compared for similarities and differences within the data sets collected from Twitter and Facebook and then in the subsequent interviews phase. This resulted in the corroboration of the emerged themes of forms and the discovery of new drivers. To illustrate, the netnographic data analysis revealed the nine forms and only three drivers (altruism, escapism, and disapproval), which were found in both Facebook and Twitter posts. The interviews served as corroboration of forms and the already revealed drivers and discovering new drivers in the participants' responses. For example, the first 20 interviews revealed a couple of more drivers (despondency and optimism); the next 20 interviews revealed, in addition to the previously captured drivers, an additional one (reciprocity). The final 10 interviews resulted in no new drivers. Thus, theoretical saturation was achieved (Corbin & Strauss, 2008).

Following Creswell (2014) recommendations, crosschecking of coding was undertaken, and the research team reached an agreement on coding. According to Creswell (2014), we had more than two coders agree on codes with a high (98%) overall consistency between coders (Miles & Huberman, 1994). The analysis reveals nine forms and six drivers of social media users’ engagement behavior about the global crisis. These are introduced and discussed in the following sections with exemplars (bold font is used in exemplars to highlight specific forms and drivers).

5. Findings

5.1. Forms of social media users’ engagement behavior toward the global crisis

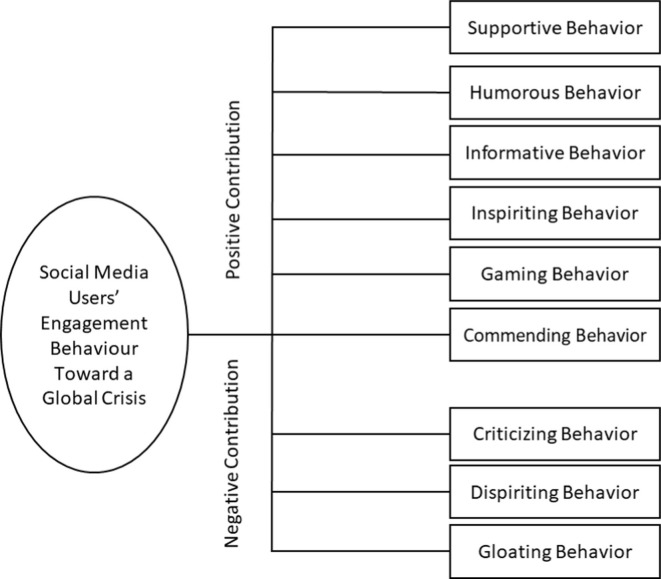

This study conceptualizes a typology of nine forms of social media user’s engagement behavior toward the global crisis and classifies them into positive and negative contributions (see Fig. 1 ).

Fig. 1.

Forms of social media users’ engagement behavior toward a global crisis.

5.1.1. Positive contributions

Supportive Behavior

Supportive behavior refers to social media users' contributions that have a global crisis focus to help other actors deal with the crisis. In 21% of posts, individuals engage toward the global crisis on social media by mobilizing themselves to reach out to vulnerable and isolated people to help solve their problems. Users share posts that provide supportive tips to help others cope with these unprecedented times, such as relaxation tips, breathing, chilling exercising and/or activities, and working from home, for example: ‘For those who feel a bit stressed about #covid19, here are some tips on relaxation and some chill skills ’. In other instances, they share contact numbers of crisis relief helplines for mental and psychological support, for example: ‘ These helpline numbers are available for providing support to the elderly in distress . We reached out last week, and they are very helpful.’ Also, volunteering to do grocery shopping and/or prescription delivery for people in quarantine, for example: ‘My friends and I are volunteering to collect grocery shopping and a prescription for those self-isolating or in quarantine , we are here to help.’

Engagement about COVID-19 manifested in supportive behavior, emerged around needs by the users themselves rather than centrally coordinated. It appeared as a response to the disruptive events caused by COVID-19. Particularly its relation to the crisis in the type of support users offers to others. Such support is not brand-related advice to help others make a purchase decision (e.g., Azer and Alexander, 2018, Chang and Wu, 2014, Hennig-Thurau et al., 2004), or in response to health-seeking advice (Naslund, Aschbrenner, Marsch, & Bartels, 2016) that is found to be common among peers on social media seeking mental health support. Instead, users voluntarily mobilize themselves to reach out to others by contributing their knowledge, skills, and labor. In fact, offering support to others has been associated with crisis relief efforts via social media users such as ‘voluntweeters’ (Starbird & Palen, 2011) and ‘groupsourcing’ (Chamberlain, 2020), thus revealing the power of social media networks in a crisis.

Humorous behavior

Humorous behavior refers to social media users’ contributions that have a global crisis focus to cause other actors’ laughter about the crisis. Humor is typically perceived as a positive communication attribute that people employ, especially in less humorous situations such as distress (Booth-Butterfield & Booth-Butterfield, 1991) and a way of seeing the funny sides of things that trigger positive affective states such as joy, fun, or cheerfulness (Jäger and Eisend, 2013, Pundt, 2015). The stress conditions and the undercurrent of anxiety unleashed by the COVID-19 lockdown are the perfect breeding ground for engaging in humorous behavior (Arning, 2020). In 19% of posts, customers contribute the required skills to semantically manipulate a message about the COVID-19 crisis with humor elements. Notably, this study captures data demonstrating two main humor approaches: incongruity (life now vs. before), for example: ‘ Fencing will be the perfect covid19 sport , masks, gloves, if anybody gets closer than 6 feet to you, you stab them’. ‘ Masks are apparently the new bra . They are uncomfortable, you only wear them in public, and when you do not wear one, everyone notices.’ Also, self-deprecating (users saying funny things at their own expense), for example: ‘Having all of us at home during this pandemic lockdown is like hosting the tiger who came to tea . All the food has gone from the fridge & the cupboards, and almost all of Daddy's beer too. We need to speak to the virus’ manager. ’

Although engaging toward a crisis in humorous behavior seems discordant, positive emotions such as those elicited by humor can be important coping mechanisms with a crisis (Fraustino et al., 2012, Jäger and Eisend, 2013). According to social psychologists, there is a neurobiological aspect of humorous behavior; it brings joy and pleasure, which is associated with cognitive and emotional dimensions of engagement (Gimbel & Palacios, 2020), besides the aspect of interaction created by a bond that builds a sense of connectedness vital to cope with the crisis (Gimbel & Palacios, 2020). Our findings show that social media users tend to be following these psychological processes, turning to and relying on social media for humor and levity (Fraustino et al., 2012), evidenced by the percentage of humorous behavior in the data.

Informative behavior

Informative behavior refers to social media users’ contributions that have a global crisis focus to keep other actors informed about the crisis. Without offering support or additional comments, in 16% of posts, users tend to share the latest news, for example: ‘ Breaking News : Two detected as covid19 positive including Food Delivery boy in Nagpur, Maharashtra. Admin tracing the places where delivery boy visited by order details’ and updated death tolls and infected numbers for example: ‘UK records a further 861 coronavirus deaths with over 100,000 infected . Global Data: Total Cases: 2,097,101 . Total Recovered: 523,365 . Total Deaths: 135,662 ′.

Informative content (e.g., from a brand's post) leads to passive engagement such as reading or active engagement (Dolan et al., 2016, Ko et al., 2005), which this study captures in contributing information about the global crisis. In normal times, sharing informative posts about a brand would likely cause lower engagement levels than sharing persuasive posts (Azer and Alexander, 2020a, Cvijikj and Michahelles, 2013, Dolan et al., 2016). However, crises often breed high levels of uncertainty among the public (Mitroff, 2004). It follows that, according to crisis communication research, social media users will engage in heightened informative behavior (Fraustino et al., 2012). We find this where users inform others with timely and unfiltered information in crises such as COVID-19, which is inherently unpredictable, unprecedented, and consistently evolving. Such informative behavior helps others to determine crisis magnitude.

Inspiriting behavior

Inspiriting behavior refers to social media users’ contributions that have a global crisis focus to spread hope to other actors about the crisis. In 15% of posts, users tend to share reflections and personal experiences that focus on the current events' bright side, for example: ‘ Lovely walk in the woods near me came across a bug hotel and some lovely wildflowers. Amazing what you see when you open your eyes , lockdown coming in as a blessing in disguise’ . By engaging in inspiriting behavior, users are avoiding much focus on the inevitable problems that crop up in a fast-moving COVID-19 crisis and rather try to spread hope as people navigate these hard times (LeBreck, 2020) for example: ‘Keeping the bright side out, this is a cute reminder for all of us to stay positive while fighting the virus.’

Such behavior is associated with COVID-19 and, specifically, social distancing. According to Donthu and Gustafsson (2020), an increase in more positive behaviors caused by social distancing happened as people started to nest, develop new skills, learn how to bake, read more, and take better care of where they live. Such offline positive change in people’s behavior is reflected in their behavioral manifestations on social media to make others see the bigger picture and numerous benefits (Boyd, 2020). To illustrate, users in their posts highlight the opportunities created by the crisis exemplified in the availability of more time to appreciate the natural scenery, quality time with the family, redecorating houses, new hobbies they learned under lockdown (e.g., baking, cooking, painting, and playing music), and online reunions with social networks. For example: ‘ Before lockdown , if someone had asked me my hobbies, I would never know what to say, but I can now say walking, cooking and painting. it's beautiful, gives you time to think and appreciate.’

According to health and social psychology literature, inspiriting others serves as a health-promoting behavior that stems from physiological concomitants of coping with the COVID-19 crisis (e.g., coping with Lockdown, working from home, restrictions…etc.) and plays a significant role in enhancing actors’ physical health (Carver & Scheier, 2014).

Gaming behavior

Gaming behavior refers to social media users’ contributions that have a global crisis focus to challenge other actors in crisis-called games. In 5% of posts, social media users tend to engage in gaming behavior, such as sharing crosswords and puzzles that they call after the crisis and its associated activities such as quarantine and lockdown. For example, ‘ Lockdown is boring! Games can make it more fun. Here is a Lockdown Puzzle: Can you see the nest, the duck, and the butterfly? Message me if you need to check’, and IQ challenging games, for example: ‘Okay! Quarantine game time : Name a movie that starts with the letter A. No googling! Let's Play’. ‘I accepted the challenge and won. Now it’s your turn: You enter a room, and there are 34 people, you kill 30. How many are left in the room? if you answered correctly, share it and keep the lockdown games on. ’

According to psychologists, people tend to escape from a complex reality (Tuan, 1998) in an ephemeral manner (Anderson, 1961); games make it easy to lose track of time and escape undesired situations (Vorderer, 1996). Gaming behavior has been associated with the COVID-19 crisis, where recent market research has shown that gamers worldwide are spending more time on online games during the COVID-19 crisis. During the crisis and specifically social distancing, users are increasingly opting for more multi-player games with greater online social interaction (Nabity-Grover et al., 2020), including 23% of users who had never engaged in gaming before the COVID-19 crisis (Simon-kucher.com., 2020). Specifically, in times of lockdown and social distancing, games afford the ability to engage with, compete against, and collaborate with remotely located friends in their living rooms (Calleja, 2010).

Commending behavior

Commending behavior refers to social media users’ contributions that have a global crisis focus to commend other actors’ behaviors toward the crisis. In 5% of posts, social media users tend to give other actors (e.g., governments, organizations, authorities & citizens) kudos on the steps taken to curb the virus, for example: ‘Thanks to the tracing app developed by the government , monitoring people who may be infected with coronavirus should be much easier now.’ Also, commend cooperative reactions to restrictions in places, such as lockdown and social distancing, for example: ‘I am extremely grateful and commend everyone who has done and continue to do their best to practice social distancing and stay home to save others’ lives.’

Unlike recommending brands to others based on one’s brand-related favorable experiences (e.g., Jaakkola and Alexander, 2014, Van Doorn et al., 2010), engaging in commending behavior about the crisis appears to be at a more macro level that involves the general society, and the environment (He & Harris, 2020). As captured in the users’ posts, there is a shift towards commending a firm’s responsible and prosocial behavior rather than the quality of its offerings. They recommend services or products that are more responsible to themselves, others, society, and the environment. For instance, users commend companies based on their safety measures and social responsibility: ‘Extremely happy with the way Amazon has packed and delivered a small package considering safety measures. Huge kudos for taking packaging to the next level’. These findings align with research that has shown increased consumer awareness of brands’ values and their role in decision-making (Schamp, Heitmann, & Katzenstein, 2019).

5.1.2. Negative contributions

Criticizing behavior

Criticizing behavior refers to social media users’ contributions that have a global crisis to criticize other actors’ behaviors toward the crisis. In 11% of posts, social media users criticize other actors’ (e.g., governments, organizations, authorities & citizens) behavior in dealing with the crisis. In their posts, they focus on incompetency, inefficiency and failure of governments, organizations, and authorities (Rose and Miller, 2010, Young, 2007, Zaidi, 2009), for example: ‘It is very clear that the government acted very late almost two months after WHO declared the Corona outbreak , now the current politicians are looking for a scapegoat to cover up their failure.’ Besides, criticizing other citizens’ misbehavior, such as breaking the lockdown and social distancing rules, for example: ‘Sadly, many people in my country have broken the lockdown and social distancing rules and spend their time on the beach! This is so careless and unacceptable. ’

During a global crisis, such as the COVID-19 pandemic, people feel insecure, stressed and scared. Consequently, they tend to assign negative meaning to others’ behaviors to help themselves feel better (Mason, 2020). For instance, by criticizing others’ lack of discipline for staying at home, people think they care enough to stay home and not risk others' health. However, criticizing others does more harm than good as it is distinct from offering a critique or voicing a specific complaint (Mason, 2020, Peel, 2020). To illustrate, the unclear definition of outdoor activities, essential purchases, and stay-home orders has led some people to define these for others. As captured in our data, users’ posts indicate not only that they believe such activities are not essential, but some believe doing them is irresponsible: ‘This is crazy, people are loitering in town centers! Very irresponsible ! Stay at home, people. Lockdown rules have not been relaxed!! .’

Dispiriting behavior

Dispiriting behavior refers to social media users’ contributions that have a global crisis focus to spread negative thoughts to other actors toward the crisis. In 6% of posts, social media users tend to spread negative thoughts, either metaphorically or straightforwardly, focusing only on the situation's very dark side, death, uncertainty, for example: ‘Streets are quiet, yet there is despair, there is unrest, and there is a whole lot of uncertainty. Nothing compares to the pain of losing lives !’ and the end of normal lives, for example: ‘You will be shocked if you think things are ever going to go back to normal ; you are just caged birds.’

The COVID-19 crisis has provoked feelings of loneliness (Donthu & Gustafsson, 2020), linked to negativity and depression (Cacioppo & Hawkley, 2009), which our findings around users’ dispiriting behavior support. According to social psychology, public health and political literature streams, these shared dispiriting moods are likely to cause other actors to lose enthusiasm and hope (Warren, Strauss, Taska, & Sullivan, 2005), for example: ‘We are not fighting, we are actually cornered by COVID19 !’ Stop calling it a fight, this is NOT!! For the rest of our lives, we have to wear masks’. Such behavior provokes the fear of uncertainty, chaos, destructions, dark historical memories of wars, collapsing nations (Ostbo, 2016), and previous pandemics.

Gloating behavior

Gloating behavior refers to social media users’ contributions that have a global crisis focus to dwell on other actors’ misfortune caused by the crisis, with malignant pleasure. In 2% of posts, social media users tend to engage about the crisis by pointing out the consequences of others’ misfortune because of the crisis and feel better about themselves and their worth. For instance, in their posts, users tend to gloat about being vegetarians as the virus is presumed to be originated from eating meat, for example: ‘This pandemic seemed to come from people eating animals, and it is becoming more well known that eating animals is not the greatest thing for your health! Happy to be a vegetarian!’. In other instances, they gloat about being happy environmentalists with the lockdown and suspension of air travel as they give a break to the planet earth from the pollution caused by others: ‘I think COVID19 is boon for Earth and curse to human . You are killing the Earth !’. ‘Animals caged to amuse all humans. I hope in this lockdown you realized that even animals feel the pain like how you are now ’.

This behavior is consistent with social psychologists' prior views (Cf. Jones, 2013, Shamay-Tsoory et al., 2007). According to (Smith, 2013), ‘schadenfreude’(an emotion as ignoble as gloat, from the German for harm (Schaden) and joy (Freude)) is a reason that misfortunes of others give some others a lift. In short, it can pay psychological dividends by enabling some people to feel better about themselves through downward comparison with others. We find that this behavior is eminent about the COVID-19 crisis, where personal feelings of insecurity are likely heightened (Mason, 2020).

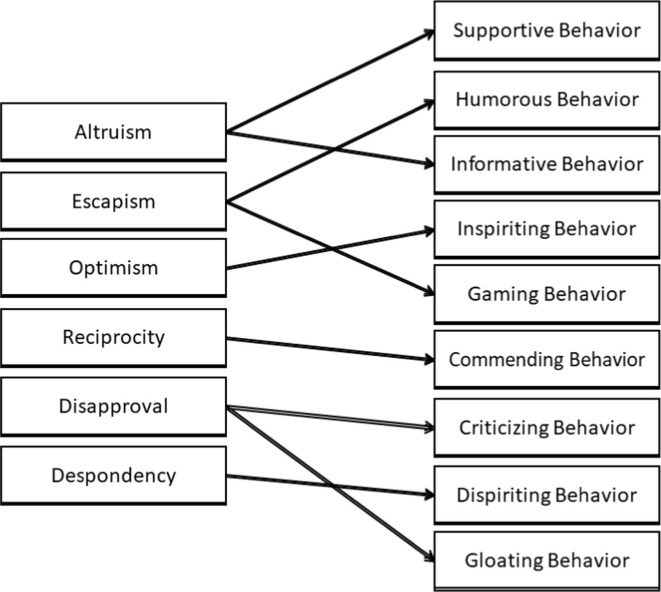

5.1.3. Drivers of social media users’ engagement behavior toward the global crisis

This study identifies six drivers that elucidate social media users to engage in specific forms of engagement behaviors toward the global crisis: Altruism, Escapism, Optimism, Disapproval, Despondency and Reciprocity. In addition to the conducted interviews that helped identify the drivers, further analysis was applied to explore the drivers and forms' relationships. The matrix coding query function of NVivo pro (see Table 1 ) shows the coverage of each form and possible co-occurrence with drivers by searching for data coded to multiple pairs of items simultaneously using the row percentage matrix (Hutchison, Johnston, & Breckon, 2010). This matrix considers the total number of coded words across all cells for each row, and then a percentage is given for each cell to represent its proportion compared to other cells in the same row (QSRInternational.com., 2016).

Table 1.

Matrix coding query – row percentages.

|

Altruism is captured in this study in 30% of data and picked up in the crisis psychology literature as selfless concern for the well-being of others (CDC.gov., 2019, Fraustino et al., 2012), which is not quite like the altruistic brand-related drivers aiming to help others make good brand-related decisions (Engel et al., 1993, Hennig-Thurau et al., 2004). In social media posts and interview responses of social media users, several emphases demonstrated such as ‘out of care for lives,’ ‘support others, ’ ‘well-being of others,’ ‘ duty to care.’ Social media users update others with essential information about the pandemic quoting ‘to raise awareness’ and ‘to keep everyone updated.’ From the results of the table above and interviews, driven by altruism, users engage in informative behavior ‘I share information to raise awareness , information is necessary in uncertain times’ and supportive behaviors: ‘The least to do is to support others in crisis’.

Escapism is captured in 25% of the data and consumer literature as breaking away from mundane untransformed reality (Arnould and Price, 1993, Cova et al., 2018). This study reveals that social media users are driven by escapism during the global crisis. Times of the pandemic are frustrating, seeking to escape from such frustration; according to psychologists, customers tend to escape from a complex reality (Tuan, 1998) in an ephemeral manner (Anderson, 1961). The interview responses and social media quotes included several escapism emphases such as ‘losing track of time during the lockdown ,’ ‘escaping the frustrating reality of the pandemic’ and ‘engaging electronically with other social actors.’

Escapism drives gaming and humorous behaviors. Games are associated with escapism as games are the opposite of seriousness and somehow set apart from ordinary, everyday life (Calleja, 2010). The feedback loop that games set up between actors, especially during social distancing measures, extends the capacity to be engaged by virtue of players' need to act. For example: ‘ Escape the lockdown and complete this #lockdown puzzle tonight , who’s in?’,

Escapism also drives humorous behavior. Although humor is picked up in various leadership and organizational studies, it has barely been related to escapism. In this study, people escape the unpleasant reality and distract the mundanity of checking news and death figures with humor. Humor is known in social psychology to distract and offset recipients and raise their adaptation levels (Jäger & Eisend, 2013). In their quotes, users explicitly mentioned ‘escaping the pandemic reality,’ ‘making fun of a frustrating situation,’ ‘coping with unpleasant restrictions by making jokes’ such as working from home and lockdown. For example: ‘Coping with working from home , here is our office team wearing pajamas to work.’

Optimism is captured in 18% of the analyzed data. The study of optimism began largely in health contexts, finding positive associations between optimism and better psychological and physical health. Recently, the scientific study of optimism has extended to the realm of social relations (Carver & Scheier, 2014). Driven by optimism, users have a stable tendency to believe that good rather than bad things will happen, and according to psychologists, this optimism is steady across contexts and time (Bailey, Eng, Frisch, & Snyder†, C. R. , 2007). Hence, their optimism is unchangeable even during fearful times of pandemics, which according to contemporary psychology of crisis research, is picked up as their belief that growth may come from the experience (CDC.gov, 2019).

Driven by optimism, social media users tend to engage in inspiriting behavior. In their quotes, users emphasize the ‘need to look for the positive in bad situations,’ ‘the bright side of things’ and ‘the light at the end of the tunnel.’ In some other instances, they clearly mention optimism to be their approach in life. For example: ‘It is time to reframe COVID19 and despite the lockdown we all need to look for the positives, sing a song for the beautiful scenery ’.

Disapproval, captured in 15% of the data, drives users to engage in criticizing and gloating behaviors. From the analyzed data and the participants’ responses, disapproval has a negative opinion of someone or something. This is captured in this study where users publicly criticize other actors (e.g., governments, authorities & citizens) as they disapprove of their reactions/actions towards the pandemic. They explicitly use the word ‘disapprove’ in their quotes. This is, according to social psychologists, considered to be rational disapproval (Fraenkel, 2020). For example, ‘I personally disapprove that the govt is not acting against the reporters breaching the lockdown rule.’

On the other hand, irrational disapproval drives gloating behavior. Psychologically, people believe that irrational disapproving of things makes them better persons and drives them to gloat; thus, they feel better about themselves through downward comparison with others (Smith, 2013). This is also clearly demonstrated in their quotes that show not only their disapproval of some people’s habits but also a downward of those habits compared to themselves ‘I have always had a problem with junk food lovers , thanks to corona we can live without junk food, and it’s the best lesson to start living a healthy life.’

Despondency, which is captured in 7% of the data, drives users to engage in dispiriting behavior. Based on the participants' responses and prior psychology and health studies, despondency is a belief that the worst in life will happen (Bailey et al., 2007). The participants repeatedly expect that things will never turn out well, emphasizing verbal cues such as ‘suicide ,’ ‘ suicidal ,’ ‘ end of life’ and ‘ end of times,’ and the like. According to social psychologists, factors such as financial problems, isolation, lack of support, and separation from important relatives cause despondency (Wright, Zalwango, Seeley, Mugisha, & Scholten, 2012). This study indicates that these factors are happening and clearly driving some to engage in dispiriting behavior about the COVID-19 crisis. For example, isolation and separation: ‘Social distancing is suicide !’ financial and lack of support: ‘My company decided they don't need us anymore; life is over for me .’

Reciprocity, which is captured in 5% of the data, drives commending behavior. Based on the participants' responses and extant reciprocity theories, this study refers to reciprocity as a social norm to respond to positive action by rewarding kind actions. In services literature, recommending a service provider based on a good offering is considered rewarding (Kumar et al., 2010). This study reveals that users commend other actors’ actions toward handling the crisis as they want to ‘reciprocate ,’ ‘give credit ,’ ‘spread kudos ’ such kind actions. They commend after evaluating the kind of actions based on their consequences and the intentions underlying these actions. In their quotes, they not only spread kudos; they also mention what action they are reciprocating and how it helped others during the crisis. This is consistent with reciprocity theories (Cf. Falk and Fischbacher, 2000, Gouldner, 1960).‘The HelpHub has dealt with over 1500 cases . Superb effort by all involved helping people shielding. We all should spread kudos ; it’s the least we can do in return. ’

To summarize this paper's findings, Fig. 2 illustrates the six drivers and their relationships with the nine forms of social media users’ engagement behavior about the global crisis. The next section discusses the research findings and their theoretical and practical implications and limitations.

Fig. 2.

Relationship between forms and drivers of social media users’ engagement behavior toward a global crisis.

6. Discussion

6.1. Theoretical implications

This study contributes to theory by bridging a gap between the engagement and crisis communication research bases. While recent research has explored crisis communication on social media, it has not done so with an underpinning in contemporary engagement research. This paper explores the nature of social media users’ engagement behavior toward the COVID-19 pandemic and provides a typology of its forms and drivers. Recent research suggests that users’ engagement behavior is expected to differ due to the current period of great uncertainty and social disruption (Addo et al., 2020, Ali and Kurasawa, 2020, Karpen and Conduit, 2020). Ultimately, this paper provides a set of forms and drivers of social media users’ engagement behavior beyond commercial settings and shows how users engage with other users when the crisis is the engagement object.

Although the social media engagement behavior typology suggests that users may engage in social media via negative or positive contributions (Dolan et al., 2016), it was unclear what forms of behaviors could be considered a negative or positive contribution. This paper captures such forms, especially when the focus of engagement is the global crisis and classified them into positive (supportive, humorous, informative, inspiriting, commending, and gaming behaviors) and negative (criticizing, dispiriting and gloating behaviors) contributions. Thereby, responding to recent research calls to explore types of positive and negative social media engagement behaviors caused by social distancing (cf. Donthu and Gustafsson, 2020, Nabity-Grover et al., 2020) and study engagement objects beyond those commonly investigated (Ng et al., 2020).

Importantly, this paper contributes to the engagement literature that has, to date, tended to explore engagement behavior with a brand focus, with the first typology of engagement behavior with a global crisis focus. The conceptualized forms and drivers specifically highlight how the COVID-19 pandemic – the focus of engagement- has affected individual users’ behavioral manifestations. For instance, although helping others is captured in prior research to help others make a purchase decision (e.g., Azer and Alexander, 2018, Chang and Wu, 2014, Hennig-Thurau et al., 2004), engagement about COVID-19 in supportive behavior emerged around users’ needs by the users themselves rather than being coordinated centrally. Such behavior appeared as a response to the disruptive events caused by COVID-19 and its relation to the crisis in the type of support users offer to others that are not brand-related.

This paper captures humorous behavior as an engagement behavior, which is new to literature. By integrating social psychology and engagement research, humorous behavior fits the description of an engagement behavior. Humorous behavior brings joy and pleasure, which is associated with cognitive and emotional dimensions of engagement (Gimbel & Palacios, 2020), besides interaction created by a bond that builds a sense of connectedness vital to cope with crisis (Gimbel & Palacios, 2020). This study also captures two main humor approaches that, up to our knowledge, have not been captured in engagement models; these are incongruity and self-deprecating.

Furthermore, the paper conceptualizes informative behavior not as brand-related as it was commonly captured in prior e-WOM and engagement literature streams (e.g., Azer and Alexander, 2018, Dolan et al., 2016, Hennig-Thurau et al., 2004), but rather as specifically helping others determine crisis magnitude. This study shows inspiriting behavior as stemmed from positive offline changes in people’s behavior. According to Donthu and Gustafsson (2020), such positive change is complex, novel, and worthy of investigation, which this study captures as reflected in people’s engagement behavior toward the crisis. Another form of behavior that has increasingly emerged in engagement about the COVID-19 crisis and reflects a change in people’s behaviors (Simon-kucher.com. , 2020) is gaming behavior that specifically affords users engagement remotely located players and friends using games they named after the crisis and its associated activities.

Additionally, this study captures a difference in the way users ‘recommend.’ Prior engagement and e-WOM research capture customers' behavioral manifestations by recommending brands, products, or services to others based on their brand-related favorable experiences (e.g., Harrigan et al., 2018, Jaakkola and Alexander, 2014, Van Doorn et al., 2010, Verhoef et al., 2010). However, as captured in this study, there is a shift towards commending a firm’s responsible and prosocial behavior rather than the quality or value of its offerings.

This paper shows that social media may also bring out the worst in people during a crisis (Donthu & Gustafsson, 2020). During the COVID-19 pandemic, people feel insecure, stressed and scared; consequently, they tend to assign negative meaning to others’ behaviors toward the crisis to feel better about themselves (Mason, 2020), which this paper captured in criticizing behavior. Importantly, such a crisis provokes feelings of loneliness, which, in prior research, has been linked to negativity and depression (Cacioppo & Hawkley, 2009), and the users’ dispiriting behavior is picked up in their social media posts indicate this is happening when their engagement focus is the current pandemic. Finally, by capturing gloating behavior, this paper extends on prior psychology research (cf. Smith, 2013) with empirical evidence of social media users’ downward comparison with others.

This study extends findings in crisis communication literature, limiting social media users’ drivers to seeking emotional support, self-mobilizing and maintaining a sense of community (Procopio and Procopio, 2007, Sweetser and Metzgar, 2007) and that of engagement literature that captured brand-related drivers (Azer and Alexander, 2018, Bowden et al., 2017, Hollebeek and Chen, 2014) with a more nuanced view of drivers to engage in specific forms of users’ engagement behavior toward the global crisis. Altruism is captured in this study as selfless concern for the well-being of others (CDC.gov., 2019, Fraustino et al., 2012), which is not quite like the altruistic brand-related drivers aiming to help others make good brand-related decisions (Engel et al., 1993, Hennig-Thurau et al., 2004). This study reveals that social media users are driven by escapism, consistent with prior social psychology research suggesting they sought to escape a complex reality (Tuan, 1998) and the frustration caused by the pandemic in an ephemeral manner (Anderson, 1961). Optimism is also captured as a driver, thereby extending findings in the contemporary psychology of crisis research (CDC.gov, 2019), suggesting that in crisis, people may still think good rather than bad things will happen (Bailey et al., 2007), and growth may come from the experience (CDC.gov, 2019). Reciprocity captures rewarding kind actions toward handling the crisis, spreading kudos and how these actions helped others in the crisis. This is consistent with reciprocity theories (Cf. Falk and Fischbacher, 2000, Gouldner, 1960), and it is not quite like the brand-related reciprocity driver; recommending a brand or service provider based on a good offering (Kumar et al., 2010). Disapproval is captured in this study as having a negative opinion of someone or something, and in line with social psychology research, this paper captured both rational and irrational disapproval (Fraenkel, 2020). Finally, despondency is captured as a belief that the worst in life will happen (Bailey et al., 2007). Consistently with social psychologists, this study showed examples of factors caused by the pandemic, such as financial problems, isolation, and lack of support nurture despondency (Wright et al., 2012).

Noteworthy is that none of the previous studies has shown relationships between drivers and specific forms of social media users’ engagement behaviors. The relationships this study develops between drivers and forms is a unique contribution to both engagement and crisis communication research. Understanding the relationship between forms and drivers is necessary as it shows what drives social media users to engage in specific forms, which, in turn, facilitates the development of strategies of social media marketing during a crisis.

Finally, the focus on C2C engagement behaviors, elevated in crisis communication, is a unique contribution of this study. This paper provides an understanding of social media users’ engagement behavior toward crises at a broader level and not only in social media interactions with specific organizations. Therefore, aligns with recent research assertions that marketers and organizations should consider the social media user’s state in their efforts to foster engagement during a global crisis (e.g., Donthu and Gustafsson, 2020, He and Harris, 2020, Karpen and Conduit, 2020, Nabity-Grover et al., 2020).

6.2. Managerial implications

This paper provides interesting insights for managers and organizations to better engage and communicate through social media in a global crisis. Specifically, the results offer a sense of social media users’ real-time sentiments reflected in their behavioral manifestations, which managers should consider to deliver messages and engage in conversations that are considered valuable and helpful (De Valck, 2020). Facing a global crisis, social media managers may need to pause their ongoing campaigns and listen to their social media audiences to understand how their consumers react to the issue. While informing the users is important, our results also offer insights regarding how different social media users may engage about a global crisis.

Managers also need to focus on developing social media content to engage with users on their terms. Based on the results, this paper provides managers with some recommendations as follows. Organizations should not only do their best to make sure their actions are not negatively affecting their consumers but also think about the crisis to enhance relationships with the local communities in which they operate. For instance, firms can engage in supportive behavior; Lidl UK is a great example of a brand showing support for its shoppers by posting reassuring updates using social media. Similarly, Nike devoted some effort to social media via ‘play inside, play for the world’ posts to support people during the lockdown and social distancing (Nanji, 2020).

Organizations may also engage in inspiriting behavior to help spread hope and calm the communities down; this is likely to enhance the organization’s likability and credibility. A good example is a campaign launched by French Connection - #TreatTuesday– where the brand gives their social media users the chance to tag family members or friends who needed a little love and help spread hope and lift their spirits.

Furthermore, people extensively turn to social media for humor and levity (Fraustino et al., 2012); as captured in this study, engagement in humorous behavior demonstrates a higher percentage than informative. Fields like entertainment, home goods, and fast food started to shift their message to be more humorous while focusing on benefits to their consumers or frontline healthcare workers (Ho, 2020). Additionally, gaming behavior creates an environment of engagement which people seeks during crisis more than normal times. The famous beer brand Budweiser engaged with its users via the ‘#Whassup’ campaign about checking in with friends, engaging in games, reviving old games and having a beer (Ho, 2020). Accordingly, managers may think clearly about their brands' unique role in people’s lives and may engage in humorous and gaming behaviors to provide their consumers with a fun distraction during the crisis.

Adjusting social media content during a global crisis should also encompass informing. Businesses could be helpful by engaging in informative behavior with their customers, for example, by simply sharing their opening hours and any disruptions that might be caused by the crisis. British Airways uses Twitter to inform its users of flexible changes due to travel (Read, 2020). Notably, managers should seek to consider the recent shift in users’ behaviors towards commending a firm’s responsible and prosocial behavior rather than its quality or value. Therefore, managers are recommended to align how they offer services and products to the recent consumers’ interest in prosocial behavior raised by this crisis.

Finally, identifying the underlying drivers of social media users’ behavior manifestations is crucial to increasing social media communications in a crisis. We have shown that different drivers may drive different forms of engagement behaviors. Identifying those users with altruistic motives who exhibit positive behaviors such as informing and supporting may help increase the reach of relevant messages for them and their networks. Nurturing and benefiting communication with those driven by optimism that exhibits an inspiriting behavior may also foster a more positive sentiment in the organization’s audiences. As identified in this study, negative behaviors in crisis are related to despondency and disapproval, which may require a very different kind of treatment than other negative behaviors based on dissatisfaction or revenge. For example, companies may focus on empathy rather than trying to create a selling opportunity. All in all, using the identified forms as a potential segmentation base to organize the social media content strategy might be a powerful tool to develop impactful social media strategies in a crisis.

6.3. Limitations and future research

Despite the contributions and implications indicated above, this study's limitations also offer future research directions in this area. Netnography has inherent limitations that lend themselves to inductive rich insights rather than generalization (Kozinets, 2010). However, sampling was intended to be meticulous to ensure diversity of contexts, robustness and stability of findings (Miles & Huberman, 1994), and depth interviews were conducted to corroborate findings. Twitter and Facebook were selected as the focus of this study for appropriateness rather than representativeness (Kozinets, 2010); however, this research's findings reveal a convergent pattern across both contexts. Despite this rigor, future research might explore different online contexts.

This research provides empirically driven definitions of the forms of social media users’ engagement behavior toward a global crisis. Future research can use these conceptualizations and test their impact on other actors in social networks (e.g., other individual receivers, firms, governments and public health organizations), specifically, how these forms differ in their impacts on other actors in online social networks. That would contribute to engagement literature with insights about the intensity levels of these forms. Further research could investigate the relationship between engaging in these forms and the users' interaction levels from their audience. This is likely to contribute to the influencer's marketing, engagement and e-WOM literature streams.

This paper provides a framework of relationships between drivers that trigger social media users to engage in specific engagement forms toward the crisis. Future research can use this framework to test forms-drivers’ relationships quantitatively. The paper also provides percentages of each form of users’ engagement behavior frequency, which further research can investigate the mechanism behind such frequencies.

This paper focuses on C2C engagement behaviors toward a global crisis, which is a unique contribution. Future research can replicate this study by focusing on communications by organizations, governments, and brands toward the crisis and how they influence social media audiences. Finally, future research may investigate differences in social media users’ engagement behavior with the ‘new normal’ as a focus of engagement.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Biographies

Jaylan Azer is an Assistant Professor of Marketing at Adam Smith Business School, University of Glasgow, UK. Her research interest focuses within the services domain on the complementary concepts of Service Dominant Logic, value co-creation and actor/customer engagement. Within this domain, Jaylan has a focus on consumer behaviors in online social networks. Her research has been published in marketing and service journals including Journal of Business Research, Journal of Service Management, Journal of Marketing Management and Journal of Services Marketing.