Abstract

We assessed the effects of the COVID19 lockdown on the mental health of transgender and gender non-conforming (TGN) youth (n = 18) vs cisgender youth (29 males; 29 females). Coronavirus Health Impact Survey (CRISIS) and Emotion Regulation Questionnaire were used in an online study. No group differences were found in demographic variables and exposure to COVID19. Negative emotions/feeling increased for all groups. Cisgender youth reported using more adaptive emotion regulation strategies than TGN youth. While the lockdown similarly affected TGN and cisgender youth, the former showed elevated levels of symptomatology and fewer adaptive emotional regulation strategies.

Keywords: Gender dysphoria, Youth, Covid19

1. Introduction

With COVID19, most countries have implemented social distancing measures, home quarantine, and economic shutdowns. These restrictions, along with health concerns and economic uncertainty, are risk factors for psychopathology (Wang et al., 2020), especially among vulnerable subgroups at risk of adverse psychological outcomes. Adolescents experiencing incongruence between assigned gender at birth and identified gender represent one such subgroup (Becerra-Culqui et al., 2018).

This pilot study assessed the effects of COVID19 and the associated lockdown on the mental health of transgender and gender non-conforming (TGN) compared to cisgender youth. Previous work shows transgender adults at early stages of their gender transition use less adaptive emotion regulation strategies than those at later stages of their gender transition (Budge et al., 2013). We therefore hypothesized TGN youth would report higher levels of psychopathology before the lockdown, and the restrictions would affect them more severely. We also expected TGN youth would show fewer adaptive coping strategies and increased levels of the pandemic's adverse effects.

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

Eighteen TGN males, 29 cisgender males, 29 cisgender females, and their main caregivers participated in an online study including retrospective reports related to three months before COVID19 and the previous two weeks of the lockdown. Recruitment used social media, specific mailing lists, and word-of-mouth. Fifty-six youth (12 TGN males/22 cisgender males/22 cisgender females) and 66 caregivers (15 TGN males/27 cisgender males/24 cisgender females) completed a follow-up survey two-three weeks after initial assessment. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board. Youth and caregivers signed informed consent before participation.

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Coronavirus health impact survey (CRISIS-V0.2)

CRISIS measures the specific effects of the pandemic. The questionnaire is comprised of youth self-reports (9–18 years) and caregivers’ reports on youth (Nikolaidis et al., 2021). It has six parts: coronavirus exposure status; life changes; emotions/feelings; daily behavior patterns; media use; substance use. Participants were asked to rate these for two time points: retrospectively three months before COVID19 and during the preceding two weeks when lockdown was in effect. The follow-up questionnaire included the same questions but referred only to the preceding two weeks.

2.2.2. Emotion regulation questionnaire (ERQ)

ERQ measures tendencies to regulate emotions using two strategies: cognitive reappraisal and suppression. Cognitive reappraisal refers to changing the way we think about an emotion-eliciting situation; suppression refers to actions taken to reduce the intensity of the experience. Reappraisal is an efficient strategy to decrease negative emotions; suppression is less adaptive. ERQ comprises 10 items rated on a 7-point Likert scale (Gross and John, 2003).

2.3. Procedure

Questionnaires were delivered online. In Israel, the official lockdown began 12 March 2020 with the closure of educational institutions and gradual lockdown of other public and private establishments. Throughout April, nationwide restrictions included remaining within municipal boundaries and shopping only for essentials. A full curfew was in place. Participants completed the initial assessment that month. Two-three weeks later, when most restrictions were still in effect, participants completed the follow-up survey.

2.4. Data-analysis

Repeated measures (RM)-ANOVAs and follow-up t-tests assessed changes in daily behaviors, emotions/feelings, media use and sports activities. Similar analysis examined differences in emotion regulation. We also conducted moderation analyses, with group as focal predictor, emotions/feelings as moderator, and emotion regulation strategy as dependent variable. Parents’ reports are presented in the supplemental materials.

3. Results

3.1. Group differences before COVID19

Participants did not differ in age, socioeconomic status, or religion. However, TGN and caregivers reported poorer physical and emotional health before the pandemic than cisgender males/females and caregivers (see TableS1 supplement materials).

3.2. Exposure to coronavirus

No group differences were found in exposure to COVID19. No participants had lost a family member or friend.

3.3. Effects of COVID19

3.3.1. Emotions/feelings

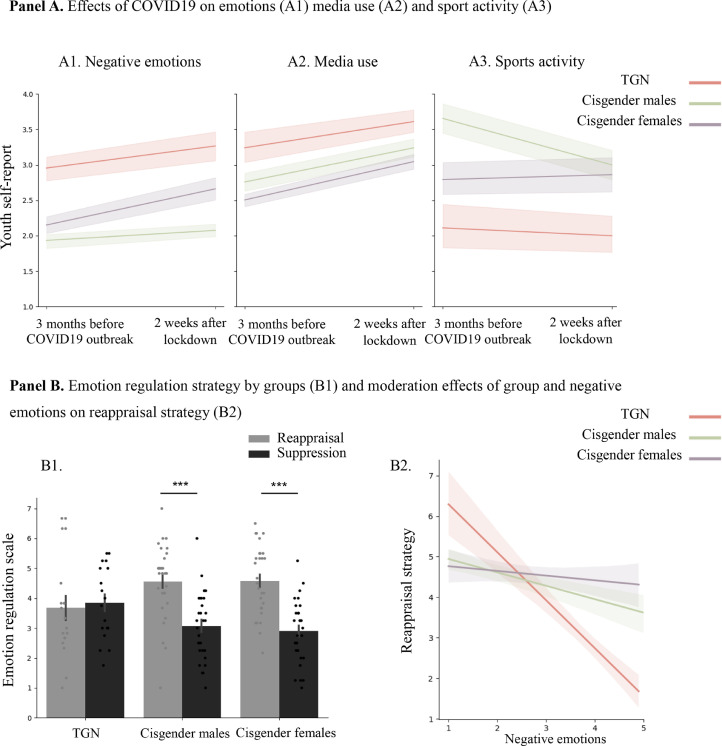

A main effect of time emerged, F(1,73)=15.61, p<.001, η2p=0.18, indicating an increase in negative emotions following the outbreak for all groups. A main effect of group also emerged, F(2,73)=17.76, p<.001, η2p=0.33. TGNs reported more negative emotions than cisgender males and females, ps<0.002. However, cisgender females reported higher levels of negative emotions than cisgender males, p=.047 (Figure A1).

3.3.2. Media use

A main effect of time emerged, F(1,73)=56.35, p<.001, indicating an increase in media use for all groups. A main effect of group emerged, F(2,73)=6.21, p=.003, η2p=0.14. with TGNs reporting more media use than cisgender males and females, p<.024 (Figure A2).

3.3.3. Sports activity

A main effect of group emerged, F(2,73)=7.52, p=.001. TGNs reported less sports activity than cisgender males and females, p<.022, η2p=0.13 (Figure A3).

3.4. Emotion regulation questionnaire

A two-way interaction emerged, F(2,73)=7.37, p=.001, η2p=0.17. Cisgender males and females (ps<0.001) exhibited more reappraisal than suppression, TGNs did not differ in their use of reappraisal and suppression emotion regulation strategies (p=.695).

3.5. Moderation effects of group and emotions/feelings on emotion regulation

A main effect of negative emotions on cognitive reappraisal was significant (β=−6.98, p<.001), indicating they were inversely related to the implementation of cognitive reappraisal. The interaction between group and negative emotions was also significant (β=3.34, p=.007), with TGNs showing decreased cognitive reappraisal with increased levels of negative emotions (see FigureS1, supplemental materials)

3.6. Follow-up assessment

A main effect of time emerged, F(2106)=9.21, p<.001, η2p=0.15. All youth showed increased negative emotions during COVID19 and a decrease at follow-up. A main effect of group emerged, F(2,53)=12.14, p<.001, η2p=0.31, with TGNs reporting more negative emotions than cisgender males and females, ps>0.003.

Fig. 1.

A. Effects of COVID19 on emotions (A1) media use (A2) and sport activity (A3) B. Emotion regulation strategy by groups (B1) and moderation effects of group and negative emotions on reappraisal strategy (B2).

4. Discussion

The effect of the lockdown on mental health seemed comparable for the three groups, with negative emotions increasing significantly. Other studies show the pandemic and its associated restrictions have an adverse effect on the mental health of youth in general (Liang et al., 2020). In our study, levels of negative emotions were higher among TGNs than cisgender males and females. Furthermore, TGNs and caregivers reported lower levels of physical and emotional health than cisgender groups before the outbreak. Previous studies have similarly found mental health conditions are common among TGN adolescents (Becerra-Culqui et al., 2018). The pre-COVID19 mental health of TGNs was already comparatively poorer: their status worsened during the lockdown, presumably making them more vulnerable to pandemic effects.

While sports activities did not change before and during COVID19 in any group, TGNs reported less participation than cisgender males and females. A recent study similarly found lower levels of physical activity among TGN youth (Bishop et al., 2020). Media use increased in all groups and was greater among TGN than cisgender youth. The observation of increased media use during lockdown is compatible with quarantine regulations and could represent a strategy for coping with social distancing.

Cisgender males and females used cognitive reappraisal more than suppression, but TGNs did not differ in their use of the two. This is similar to a previous study in adults (Budge et al., 2013). Moreover, the association between levels of negative emotions and the use of cognitive reappraisal was moderated by group: more negative emotion were associated with less reappraisal mainly in the TGN group.

Our study has several limitations. First, the TGN sample was small and included only males. Given the urgency of collecting data during the first lockdown and recruitment using social media and word-of-mouth, we opted for the small sample. Second, recruiting via social media support groups may cause a selection bias due to the supportive nature of the families. Third, given the prolonged nature of the pandemic, long-term changes are of interest, but we examined only two time points, both at the height of the lockdown. Fourth, pre-COVID19 status was reported retrospectively during lockdown.

This pilot study assessed mental health in TGN adolescents during the lockdown. While results suggest it similarly affected TGN and cisgender youth, the former showed elevated levels of symptomatology and fewer adaptive emotional regulation strategies.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Liat Perl: Conceptualization, Writing – original draft, Data curtion, Writing – review & editing. Asaf Oren: Conceptualization, Writing – original draft, Data curtion, Writing – review & editing. Zohar Klein: Software, Formal analysis, Data curtion, Visualization. Tomer Shechner: Conceptualization, Methodology, Validation, Formal analysis, Writing – review & editing, Supervision.

Conflict of interest

Authors have no conflict of interests

Footnotes

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2021.114042.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

References

- Becerra-Culqui T.A., Liu Y., Nash R., Goodman M. Mental health of transgender and gender nonconforming youth compared with their peers. Pediatrics. 2018;141(5) doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-3845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bishop A., Overcash F., McGuire J., Reicks M. Diet and physical activity behaviors among adolescent transgender students: school survey results. J. Adolesc. Health. 2020;66(4):484–490. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2019.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budge S.L., Adelson J.L., Howard K.A. Anxiety and depression in transgender individuals: the roles of transition status, loss, social support, and coping. J. Consult Clin Psychol. 2013;81(3):545. doi: 10.1037/a0031774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross J.J., John O.P. Individual differences in two emotion regulation processes: implications for affect, relationships, and well-being. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2003;85(2):348. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.85.2.348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang L., Ren H., Cao R., Mei S. The effect of COVID-19 on youth mental health. Psychiatr. Q. 2020;91(3):841–852. doi: 10.1007/s11126-020-09744-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nikolaidis A., Paksarian D., Alexander L., Merikangas K.R. The Coronavirus Health and Impact Survey (CRISIS) reveals reproducible correlates of pandemic-related mood states across the Atlantic. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):1–13. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-87270-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang C., Pan R., Wan X., Ho R.C. Immediate psychological responses and associated factors during the initial stage of the 2019 coronavirus disease epidemic among the general population in China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Pub. Hea. 2020;17:1729. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17051729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.