Abstract

Heart Failure (HF) patients are at a higher risk of adverse events associated with Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). Large population-based reports of the impact of COVID-19 on patients hospitalized with HF are limited. The National Inpatient Sample database was queried for HF admissions during 2020 in the United States (US), with and without a diagnosis of COVID-19 based on ICD-10-CM U07. Propensity score matching was used to match patients across age, race, sex, and comorbidities. Multivariate logistic regression analysis was used to identify predictors of mortality. A weighted total of 1,110,085 hospitalizations for HF were identified of which 7,905 patients (0.71%) had a concomitant diagnosis of COVID-19. After propensity matching, HF patients with COVID-19 had higher rate of in-hospital mortality (8.2% vs 3.7%; odds ratio [OR]: 2.33 [95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.69, 3.21]; P< 0.001), cardiac arrest (2.9% vs 1.1%, OR 2.21 [95% CI: 1.24,3.93]; P<0.001), and pulmonary embolism (1.0% vs 0.4%; OR 2.68 [95% CI: 1.05, 6.90]; P = 0.0329). During hospitalizations for HF, COVID-19 was also found to be an independent predictor of mortality. Further, increasing age, arrythmias, and chronic kidney disease were independent predictors of mortality in HF patients with COVID-19. COVID-19 is associated with increased in-hospital mortality, longer hospital stays, higher cost of hospitalization and increased risk of adverse outcomes in patients admitted with HF.

Introduction

In January 2020, Severe Acute Respiratory Coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2) was first detected in the United States (US), with more than 96 million cases confirmed to date.1 Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) has evolved into a public health crisis and yet its full spectrum continues to be fully elucidated. Previous reports suggested that patients with various cardiovascular comorbidities are at a high risk of morbidity and mortality.2, 3, 4

HF itself was designated as an emerging epidemic in 1997, and currently there are more than 6 million patients with HF in the US. Heart failure is responsible for 8.5 % of total deaths in the US every year and accounts for 900,000 hospital admissions annually.5 Patients with HF when infected with various respiratory viral infections, can develop acute decompensated heart failure further associated with adverse outcomes including death.6 There is sparse data regarding morbidity and mortality of SARS-CoV-2 infection in hospitalized patients with HF.2 , 3 , 7

We conducted a population-based analysis using a large national representative database to compare the characteristics and outcomes of adult patients hospitalized with HF with and without concomitant COVID-19. We also aimed to elucidate clinical predictors of adverse outcomes in HF patients with COVID-19.

Methods

Data Source

The Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP)—Nationwide Inpatient Sample (NIS) data is the largest all-payer inpatient data set in the US and is available publicly. The NIS represents 95% of US hospitalizations from 44 states participating in HCUP and provides a stratified sample of 20% of discharges which includes up to 8 million hospital discharges per year. The NIS database has been previously demonstrated to correlate well with other national discharge databases and has been validated in various studies to provide reliable estimates of admissions and outcomes of hospitalization within the US. The NIS database for the year of 2020 was recently made publicly available by HCUP.

Study Population

We included hospitalizations in 2020 with diagnosis of HF based on the International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-10-CM) code and identified patients with and without a concomitant diagnosis of COVID-19 based on ICD-10-CM code U07.1.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was in-hospital mortality. Secondary outcomes included incidence of acute kidney injury (AKI), AKI requiring dialysis, acute respiratory failure, respiratory failure requiring intubation, pulmonary embolism and use of either intra-aortic balloon counter-pulsation pump, percutaneous mechanical circulatory support (MCS), or extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, average hospital costs, and length of stay.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using Stata 16.0 (StataCorp. 2019. Stata Statistical Software: Release 16. College Station, TX: StataCorp LLC) and R (R Development Core Team, Vienna, Austria). Discharge weights provided by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality were applied to obtain weighted numbers to calculate regional and national estimates.

Propensity score matching was performed to compare outcomes for patients admitted for HF with concomitant COVID-19 and patients with HF without COVID-19, using a propensity score calculated based on a multivariable logistic regression model. Propensity score matching without a replacement was performed in a 1:1 nearest-neighbor fashion with a caliper width of 0.1 of the estimated propensity scores. Logistic regression models were generated to identify the independent multivariate predictors and are reported as adjusted odds ratio (aOR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI). Continuous variables are expressed as median, interquartile range and categorical variables in percentage. Categorical variables were compared using the Pearson chi-square test and continuous variables using the Student's t'test. All reported P values are 2-sided, with a value of <0.05 was considered significant.

Results

A total of 1,110,085 adult HF-associated hospitalizations in the year 2020 were identified and 7,905 patients (0.71%) had a concomitant diagnosis of COVID-19.

Patients

Table 1 describes the baseline characteristics of patients admitted with HF, with and without COVID-19. HF patients with COVID-19 were younger [69 (58-80) years vs 72 (61-82) years; P<0.001] and more male (58% vs 53.4%, respectively; P = 0.0003). HF patients hospitalized with COVID-19 were more likely to be African American (14.3% vs 8.1%, P<0.001), and have higher incidence of concomitant diabetes mellitus (54.6% vs 50.3%, P = 0.0007), chronic kidney disease (59.2% vs 55.0%, P = 0.001), and coagulopathy (11.1% vs 7.7%, P<0.001). HF hospitalization with concomitant COVID-19 was more likely to be in urban areas (77. 5% in urban teaching hospital, 14.4% in urban non-teaching hospitals and 8.1% in rural areas, P<0.001) and in patients with lower median household income (37% in 0-25th percentile, 25% in 26-50th percentile, 21.9% in 51-75th percentile and 14.2% in 76-100th percentile, P = 0.008).

TABLE 1.

Baseline demographics and comorbidities of study population

| Pre-match cohort |

Post-match cohort |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No COVID-19 (n =1102180) | COVID-19 (n =7905) | P Value | No COVID-19 (n =7905) | COVID-19 (n =7905) | P Value | |

| Age, median (IQR) | 72 (61-82) | 69 (58-80) | <0.001 | 69 (59-80) | 69 (58-80) | 0.8247 |

| Age groups | ||||||

| 18-59 | 242405(22.0%) | 2170(27.5%) | <0.001 | 2125(26.9%) | 2170(27.5%) | 0.9613 |

| 60-69 | 237545(21.6%) | 1800(22.8%) | 1835(23.2%) | 1800(22.8%) | ||

| 70-79 | 277345(25.2%) | 1855(23.5%) | 1898(24.0%) | 1855(23.5%) | ||

| >79 y | 344885(31.3%) | 2080(26.3%) | 2050(25.9%) | 2080(26.3%) | ||

| Female | 513300(46.6%) | 3320(42.0%) | 0.0003 | 3400(43.0%) | 3320(42.0%) | 0.5646 |

| Ethnicity | 0.7847 | |||||

| Caucasian | 237865(21.6%) | 2080(26.3%) | <0.001 | 2115(26.8%) | 2080(26.3%) | 0.5981 |

| African American | 89230(8.1%) | 1130(14.3%) | <0.001 | 1185(15.0%) | 1130(14.3%) | 0.9393 |

| Hispanic | 54580(5.0%) | 405(5.1%) | 0.7663 | 410(5.2%) | 405(5.1%) | 0.6678 |

| Comorbidities | ||||||

| Atrial fibrillation | 322950(29.3%) | 2415(30.6%) | 0.2701 | 2470(31.2%) | 2415(30.6%) | 0.7281 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 554600(50.3%) | 4320(54.6%) | 0.0007 | 4270(54.0%) | 4320(54.6%) | 0.8262 |

| Hypertension | 1027975(93.3%) | 7410(93.7%) | 0.4783 | 7425(93.9%) | 7410(93.7%) | 0.8321 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 605960(55.0%) | 4680(59.2%) | 0.0011 | 4650(58.8%) | 4680(59.2%) | 0.4676 |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 195290(17.7%) | 1335(16.9%) | 0.3938 | 1260(%) | 1335(16.9%) | 0.4368 |

| Dementia | 80875(7.3%) | 665(8.4%) | 0.1114 | 605(7.7%) | 665(8.4%) | 0.5194 |

| COPD | 447000(40.6%) | 2575(32.6%) | <0.001 | 2490(31.5%) | 2575(32.6%) | 0.8711 |

| Valvular heart disease | 319090(29.0%) | 1950(24.7%) | 0.0002 | 1930(24.4%) | 1950(24.7%) | 0.7814 |

| Arrhythmias | 628630(57.0%) | 4600(58.2%) | 0.3709 | 4640(58.7%) | 4600(58.2%) | 0.548 |

| Liver disease | 72225(6.6%) | 610(7.7%) | 0.0567 | 655(8.3%) | 610(7.7%) | 0.3745 |

| Hypothyroidism | 201720(18.3%) | 1240(15.7%) | 0.0055 | 1330(16.8%) | 1240(15.7%) | 0.437 |

| Anemia | 110285(10.0%) | 650(8.2%) | 0.0217 | 710(9.0%) | 650(8.2%) | 0.6778 |

| Cancer | 46785(4.2%) | 235(3.0%) | 0.0107 | 255(3.2%) | 235(3.0%) | 0.7608 |

| Rheumatological disorders | 38665(3.5%) | 255(3.2%) | 0.5659 | 240(3.0%) | 255(3.2%) | 0.7693 |

| Coagulopathy | 85190(7.7%) | 880(11.1%) | <0.001 | 895(11.3%) | 880(11.1%) | 0.8685 |

| Obesity | 322445(29.3%) | 2230(28.2%) | 0.362 | 2100(26.6%) | 2230(28.2%) | 0.2996 |

| Coronary artery disease | 569040(51.6%) | 3865(48.9%) | 0.0292 | 3845(48.6%) | 3865(48.9%) | 0.8877 |

| Prior Stroke | 148855(13.5%) | 1095(13.9%) | 0.6971 | 1110(14.0%) | 1095(13.9%) | 0.8765 |

| Prior PCI | 148320(13.5%) | 1090(13.8%) | 0.7012 | 1005(12.7%) | 1090(13.8%) | 0.3748 |

| Prior CABG | 135085(12.3%) | 985(12.5%) | 0.8044 | 970(12.3%) | 985(12.5%) | 0.8726 |

| Prior MI | 165405(15.0%) | 1035(13.1%) | 0.0337 | 995(12.6%) | 1035(13.1%) | 0.6635 |

| Hospital location and teaching status | ||||||

| Rural | 113600(10.3%) | 640(8.1%) | <0.001 | 740(9.4%) | 640(8.1%) | 0.0073 |

| Urban non-teaching | 209645(19.0%) | 1135(14.4%) | 1415(17.9%) | 1135(14.4%) | ||

| Urban teaching | 778934(70.7%) | 6130(77.5%) | 5750(72.7%) | 6130(77.5%) | ||

| Hospital region | ||||||

| Northeast | 195515(17.7%) | 1865(23.6%) | <0.001 | 1940(24.5%) | 1865(23.6%) | 0.4498 |

| Midwest | 251790(22.8%) | 1810(22.9%) | 1605(20.3%) | 1810(22.9%) | ||

| South | 461815(41.9%) | 2970(37.6%) | 3065(38.8%) | 2970(37.6%) | ||

| West | 193060(17.5%) | 1260(15.9%) | 1295(16.4%) | 1260(15.9%) | ||

| Preferred payer | ||||||

| Medicare | 774735(70.3%) | 5140(65.0%) | 0.0003 | 5340(67.6%) | 5140(65.0%) | 0.4954 |

| Medicaid | 133280(12.1%) | 1220(15.4%) | 1115(14.1%) | 1220(15.4%) | ||

| Private including HMO | 131315(11.9%) | 1060(13.4%) | 1055(13.3%) | 1060(13.4%) | ||

| Self-pay | 34870(3.2%) | 260(3.3%) | 215(2.7%) | 260(3.3%) | ||

| Median household income (%) | ||||||

| 0-25th percentile | 371615(33.7%) | 2925(37.0%) | 0.008 | 3095(39.2%) | 2925(37.0%) | 0.4635 |

| 26-50th percentile | 300785(27.3%) | 1975(25.0%) | 1820(23.0%) | 1975(25.0%) | ||

| 51-75th percentile | 231285(21.0%) | 1735(21.9%) | 1670(21.1%) | 1735(21.9%) | ||

| 76-100th percentile | 177955(16.1%) | 1125(14.2%) | 1155(14.6%) | 1125(14.2%) | ||

| Hospital bed size | ||||||

| Small | 266310(24.2%) | 1770(22.4%) | 0.1191 | 1815(23.0%) | 1770(22.4%) | 0.9134 |

| Intermediate | 317760(28.8%) | 2195(27.8%) | 2150(27.2%) | 2195(27.8%) | ||

| Large | 518110(47.0%) | 3940(49.8%) | 3940(49.8%) | 3940(49.8%) | ||

Values are median, IQR or n (%).

CABG, coronary artery bypass grafting; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; MI, myocardial infarction; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention.

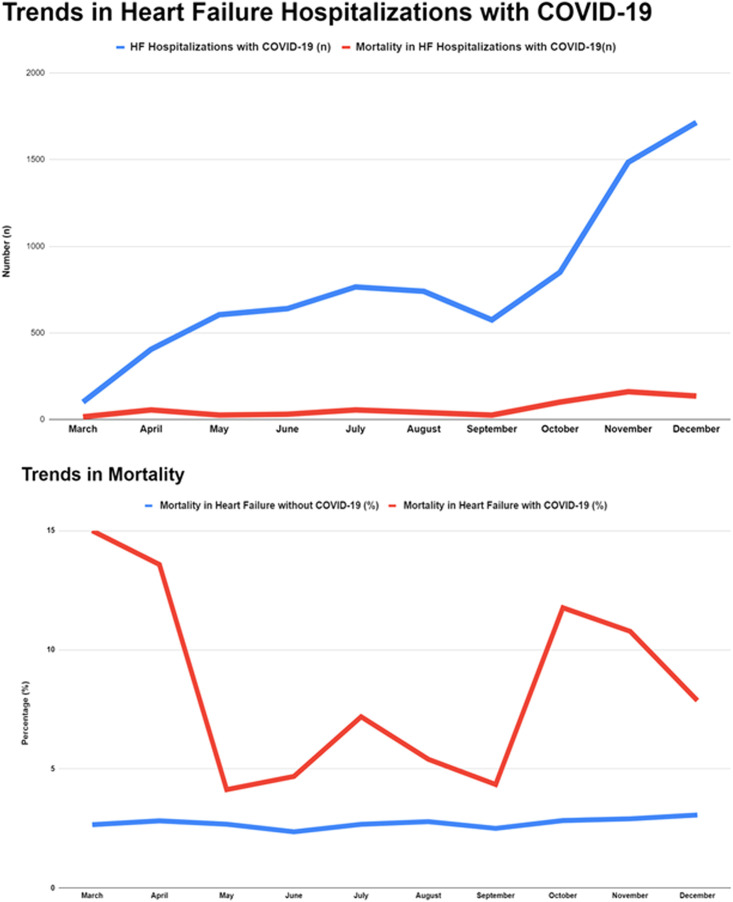

In 2020, there was an increasing month over month HF hospitalizations with concomitant COVID-19 (Fig 1 A).

FIG 1.

Trends in heart failure hospitalizations with concomitant COVID-19 and mortality.

Mortality

In a propensity score matched population with 7,905 hospitalizations in each group, HF patients with COVID-19 when compared with HF patients without COVID-19, had a higher incidence of in-hospital mortality (8.2% vs 3.7%, OR 2.33 [95% CI: 1.69, 3.21]; P <0.001). The risk of in-hospital mortality was noted to be highest for those admitted earlier in the pandemic and overall decrease after the initial months (Fig 1 with 3 distinct peaks of % mortality in March, July, and October).

Predictors of Mortality

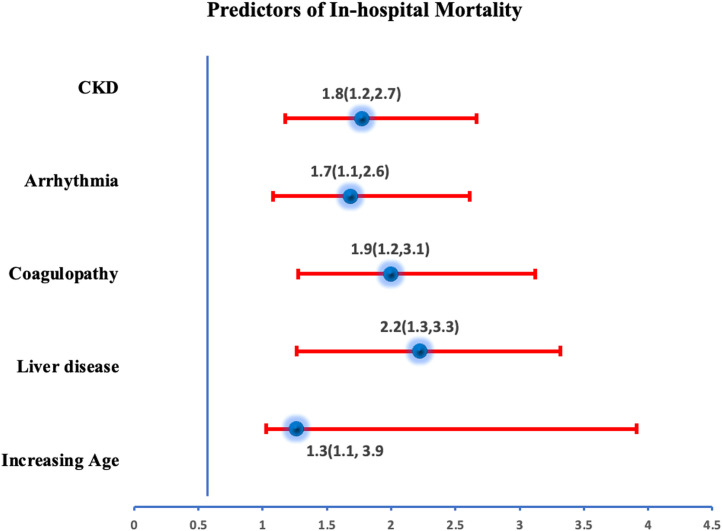

In 2020, COVID-19 was found to be an independent predictor of mortality in patients hospitalized with HF with ∼ 2.3 times increased odds of death. Further, a history of arrhythmia, chronic kidney disease, coagulopathy, liver disease, or older age were found to be independently associated with increased odds of mortality in HF patients with COVID-19 on a multivariate regression analysis (Fig 2 ).

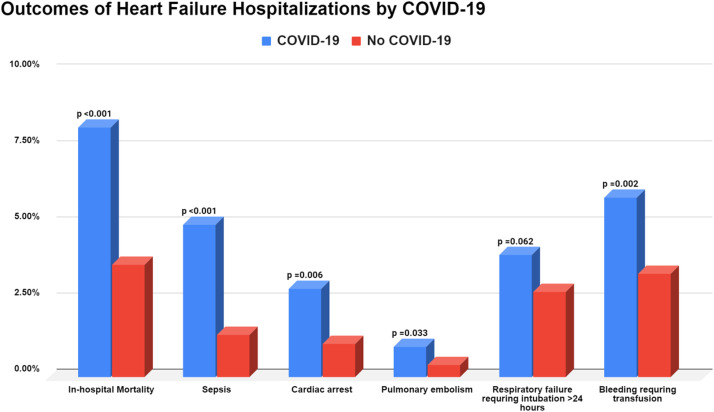

FIG 3.

Outcomes of heart failure hospitalizations stratified by concomitant COVID-19.

FIG 2.

Independent predictors of mortality in patients admitted with Heart failure and concomitant COVID-19.

Secondary Outcomes

Patients hospitalized with HF and concomitant COVID-19 were more likely to have cardiac arrest (2.9% vs 1.1%, OR 2.21 [95% CI: 1.24,3.93]; P < 0.001), pulmonary embolism (1.0%% vs 0.4%; OR 2.68 [95% CI: 1.05, 6.90]; P = 0.0329), sepsis (5.0% vs 1.4%; OR: 3.73 [95% CI: 2.33, 5.98]; P < 0.001) compared to HF patients without COVID-19. Both groups had similar rates of respiratory failure requiring ventilation, AKI requiring dialysis, and utilization of mechanical circulatory support (Table 2 ).

TABLE 2.

In-Hospital outcomes of heart failure hospitalizations stratified by COVID-19

| Pre-matching | Post-matching | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Complications | No COVID-19 (n =1102180) | COVID-19 (n =7905) | P Value | No COVID-19 (n =7905) | COVID-19 (n =7905) | P Value |

| In-hospital mortality | 29935(2.7%) | 645(8.2%) | <0.001 | 290(3.7%) | 645(8.2%) | <0.001 |

| Ref | 2.33(1.69,3.21) | <0.001 | ||||

| AKI | 401280(36.4%) | 3215(40.7%) | 0.0006 | 3010(38.1%) | 3215(40.7%) | 0.1508 |

| OR (95% CI) | Ref | 1.12(0.96,1.29) | 0.151 | |||

| AKI leading to dialysis | 23855(2.2%) | 285(3.6%) | 0.0001 | 240(3.0%) | 285(3.6%) | 0.3776 |

| OR (95% CI) | Ref | 1.20(0.80,1.77) | 0.378 | |||

| Sepsis | 14135(1.3%) | 395(5.0%) | <0.001 | 110(1.4%) | 395(5.0%) | <0.001 |

| OR (95% CI) | Ref | 3.73(2.33,5.98) | <0.001 | |||

| Deep vein thrombosis | 9160(0.8%) | 75(0.9%) | 0.6068 | 65(0.8%) | 75(0.9%) | 0.7055 |

| OR (95% CI) | Ref | 1.16(0.55,2.45) | 0.706 | |||

| Pulmonary embolism | 8255(0.7%) | 80(1.0%) | 0.2274 | 30(0.4%) | 80(1.0%) | 0.0329 |

| OR (95% CI) | Ref | 2.68(1.05,6.90) | 0.04 | |||

| Stroke in-hospital | 3130(0.3%) | 15(0.2%) | 0.4836 | 40(0.5%) | 15(0.2%) | 0.1321 |

| OR (95% CI) | Ref | 0.37(0.10,1.42) | 0.148 | |||

| Cardiogenic shock | 34410(3.1%) | 325(4.1%) | 0.0516 | 295(3.7%) | 325(4.1%) | 0.6082 |

| OR (95% CI) | Ref | 1.11(0.75,1.63) | 0.608 | |||

| Cardiac arrest | 8770(0.8%) | 185(2.3%) | <0.001 | 85(1.1%) | 230(2.9%) | 0.006 |

| OR (95% CI) | Ref | 2.21(1.24,3.93) | 0.007 | |||

| Ventricular tachycardia | 72395(6.6%) | 580(7.3%) | 0.2418 | 580(7.3%) | 580(7.3%) | 0.999 |

| OR (95% CI) | Ref | 1.00(0.76,1.32) | 0.999 | |||

| Ventricular fibrillation | 3945(0.4%) | 60(0.8%) | 0.0076 | 40(0.5%) | 60(0.8%) | 0.3637 |

| Ref | 1.50(0.62,3.65) | 0.367 | ||||

| Bleeding requiring transfusion | 39655(3.6%) | 470(5.9%) | <0.001 | 270(3.4%) | 470(5.9%) | 0.0016 |

| Ref | 1.79(1.24,2.57) | 0.002 | ||||

| Vasopressors | 11300(1.0%) | 165(2.1%) | 0.0002 | 95(1.2%) | 165(2.1%) | 0.0737 |

| Ref | 1.75(0.94,3.27) | 0.077 | ||||

| Prolonged Intubations >24 h | 16205(1.5%) | 260(3.3%) | <0.001 | 170(2.2%) | 260(3.3%) | 0.0623 |

| Ref | 1.55(0.98,2.46) | 0.064 | ||||

| Respiratory failure | 449805(40.8%) | 3185(40.3%) | 0.6864 | 2910(36.8%) | 3185(40.3%) | 0.0522 |

| Ref | 1.16(1.00,1.34) | 0.052 | ||||

| ECMO utilization | 670(0.1%) | <10(0.1%) | 0.9683 | <10(0.1%) | <100.1%) | 0.999 |

| Ref | 1.00(0.06,15.98) | 0.999 | ||||

| Impella | 2125(0.2%) | 15(0.2%) | 0.9782 | 20(0.3%) | 15(0.2%) | 0.705 |

| Ref | 0.75(0.17,3.36) | 0.706 | ||||

| IABP | 3870(0.4%) | 60(0.8%) | 0.0185 | 35(0.4%) | 60(0.8%) | 0.2942 |

| Ref | 1.72(0.62,4.80) | 0.3 | ||||

| PCI | 14135(1.3%) | 40(0.5%) | 0.0061 | 90(1.1%) | 40(0.5%) | 0.0506 |

| Ref | 0.44(0.19,1.03) | 0.057 | ||||

AKI, acute kidney injury; CI, confidence interval, ECMO, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation; OR, odds ratio by propensity matching, Ref, reference.

Health Care Utilization

HF patients with concomitant COVID-19 had longer length of hospital stay (median: 5 [3, 10] days vs 4 [2, 7] days; P <0.001) and higher median cost of hospitalization ($10,890 [6530, 20341] vs $9,175 [5884, 16494], respectively; P <0.001). Further, in survivors of hospitalizations with COVID-19, the need for rehabilitation or skilled nursing facilities at hospital discharge was higher.

Discussion

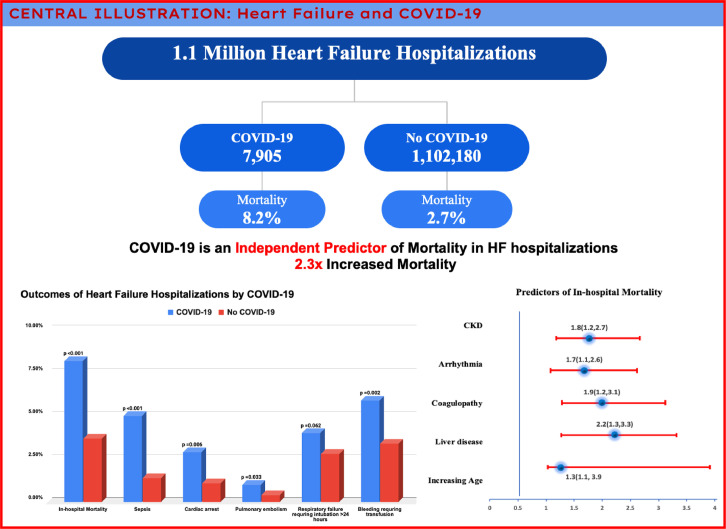

HF patients represent a population who are at a higher risk for adverse outcomes with COVID-19. In this large, national propensity-matched analysis of more than 1 million in-patient admissions, we found that the overall mortality among patients with HF who were hospitalized in 2020 with contaminant COVID-19 was 8.2%. COVID-19 was also found to be an independent predictor of mortality with approximately double the risk of mortality in patients hospitalized with HF (Fig 4 : Central Illustration).

FIG 4.

Central illustration.

The pathophysiological interplay between COVID-19 and its detrimental cardiac effect is multifaceted.8, 9, 10 An increase in mortality in HF patients has been reported in patients with other respiratory illness such as influenza.4 It has also been suggested that a rise in inflammatory cytokines seen in the acute viral infections may suppress myocardial contractility, leading to acute decompensation of previous heart failure.8 , 11 Besides the similar patho-physiological changes associated with other respiratory viral infections, the higher mortality noted in HF patients with COVID-19 could possibly be due to the use of ACE-2 receptors by SARS-CoV-2 for host cell entry, which is often upregulated in patient with HF(11). In addition, endothelial dysfunction and microvascular changes can be exacerbated in HF patients with COVID-19 leading to veno-thrombotic events.12 , 13

A previous metanalysis, which included 21,460 patients from 18 relevant studies, demonstrated an increased risk of hospitalization among HF patients with COVID-19 with an ∼3 times higher odds of mortality.14 Another report from an administrative database of 130,000 patients with HF during the period of April- September 2020, demonstrated a significantly higher in-hospital mortality among HF patients with COVID-19.2 Since the private health care database can be less generalizable than the NIS database,15 results from our study from a larger diverse nationwide population are more representative of overall challenges to healthcare during the early part of the pandemic.

These adverse outcomes in HF patients with COVID-19, especially early in the pandemic were driven by various factors. Uncertainties regarding the spread of infection and no reliable treatment options resulted in a reduction in all hospitalizations for chronic medical conditions including HF by more than 50% during the initial phase of COVID-19 pandemic.16 Furthermore, there was a significant impact in outpatient care with likely delays in diagnosis of new onset HF, and decreased outpatient/emergency room visits resulting in sub-optimal follow up of patients with existing HF as well as their comorbid chronic medical conditions like diabetes, hypertension and kidney disease. As all the critical hospital resources were diverted to care of patients with COVID-19, there was a significant impact on inpatient testing, diagnosis, and availability of in-patient resources among those seeking care for chronic medical conditions like HF during the initial phase of the pandemic.17, 18, 19 This likely resulted in unknown deaths at home/nursing homes/long term care facilities among older patients with HF, as well as a sicker hospitalized HF cohort with subsequent worse outcomes.

Our study also reports on significant socioeconomic and racial disparities in HF patients who were affected by COVID-19. HF patients with concomitant COVID-19 were twice as likely to be African American and come from a lower median income household. Previous studies have also demonstrated worse overall outcomes in patients with COVID-19 among poorer households as well as in African American and Hispanic populations.20 , 21 Our study highlights the need for a concerted long-term effort from policy makers and health care professionals to mitigate the factors leading to these disparities.

Through the currently available data, we were not able to study the effect of vaccination for COVID-19 on outcomes in patients with HF given that the vaccine was introduced at the very end of the study period of 2020. Previous studies have demonstrated vaccination to significantly decrease mortality in HF patients with various respiratory illnesses like influenza and thus patients with HF should be prioritized for preventative efforts including vaccination and early treatment against COVID-19.22

Limitations

Our study is best interpreted in the context of its limitations. Firstly, NIS is an administrative claim-based database that uses ICD-10-CM codes and thus, COVID-19 diagnosis might be susceptible to documentation and coding errors. However, studies have demonstrated accuracy for COVID-19 diagnosis.23 Residual measured and unmeasured confounding may have influenced these findings. Further, management of COVID-19 was evolving in the initial phase of the pandemic, and this study did not compare treatment modalities, radiologic and laboratory clinical findings which were not available. Despite these limitations, the HCUP-NIS is a well validated representation with good generalizability to the US population and with internal and external quality control measures. Lastly, patient selection for this study relied on identification of patients admitted for HF, and then stratified them according to whether the patient was positive for COVID-19. It is possible that the primary disease process for the COVID-19 HF patient was COVID-19 respiratory failure, rather than HF of HF with incidental COVID-19 positivity. Identification of patients by their admission diagnosis and the accuracy of that process is an inherent limitation of retrospective database analyses.

Conclusion

COVID-19 among patients hospitalized with HF is associated with greater in-hospital mortality, adverse clinical outcomes, and higher use of in-hospital resources. In a large inpatient database study, advanced age, chronic kidney disease, liver disease, and coagulopathy were independent predictors of mortality in patients with HF hospitalized with COVID-19 early in the pandemic.

Footnotes

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. WHO Coronavirus (COVID-19) Dashboard, 2020. Available at: https://covid19.who.int/. Accessed October 29, 2022.

- 2.Bhatt Ankeet S, Jering Karola S, Vaduganathan M, et al. Clinical outcomes in patients with heart failure hospitalized with COVID-19. JACC: Heart Failure. 2021;9:65–73. doi: 10.1016/j.jchf.2020.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alvarez-Garcia J, Lee S, Gupta A, et al. Prognostic impact of prior heart failure in patients hospitalized with COVID-19. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;76:2334–2348. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.09.549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Isath A, Malik AH, Goel A, Gupta R, Srivastav R, Bandyopadhyay D. Nationwide analysis of the outcomes and mortality of hospitalized COVID-19 patients. Current Prob Cardiol. 2022 doi: 10.1016/j.cpcardiol.2022.101440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Benjamin EJ, Muntner P, Alonso A, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics—2019 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2019;139:e56–e528. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Panhwar MS, Kalra A, Gupta T, et al. Effect of influenza on outcomes in patients with heart failure. JACC: Heart Fail. 2019;7:112–117. doi: 10.1016/j.jchf.2018.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tomasoni D, Inciardi RM, Lombardi CM, et al. Impact of heart failure on the clinical course and outcomes of patients hospitalized for COVID-19. Results of the Cardio-COVID-Italy multicentre study. Eur J Heart Fail. 2020;22:2238–2247. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.2052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Adeghate EA, Eid N, Singh J. Mechanisms of COVID-19-induced heart failure: a short review. Heart Fail Rev. 2021;26:363–369. doi: 10.1007/s10741-020-10037-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Clerkin KJ, Fried JA, Raikhelkar J, et al. COVID-19 and cardiovascular disease. Circulation. 2020;141:1648–1655. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.120.046941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Weisleder H, Jacobson E, Frishman WH, Dhand A. Cardiac manifestations of viral infections, including COVID-19: a review. Cardiol Rev October 25, 2022. doi: 10.1097/CRD.0000000000000481. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Bader F, Manla Y, Atallah B, Starling RC. Heart failure and COVID-19. Heart Failure Rev. 2021;26:1–10. doi: 10.1007/s10741-020-10008-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Marti CN, Gheorghiade M, Kalogeropoulos AP, Georgiopoulou VV, Quyyumi AA, Butler J. Endothelial dysfunction, arterial stiffness, and heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;60:1455–1469. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.11.082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Libby P, Lüscher T. COVID-19 is, in the end, an endothelial disease. Eur Heart J. 2020;41:3038–3044. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehaa623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yonas E, Alwi I, Pranata R. Effect of heart failure on the outcome of COVID-19 — A meta analysis and systematic review. Am J Emerg Med. 2021;46:204–211. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2020.07.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Forte ML. Not Yet Available: Cheap Data for Nationally Representative Estimates: Commentary on an article by Nathanael D. Heckmann, MD, et al.: “Elective inpatient total joint arthroplasty case volume in the United States in 2020. Effects of the COVID-19 pandemic”. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2022;104:e59. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.22.00047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bromage DI, Cannatà A, Rind IA, et al. The impact of COVID-19 on heart failure hospitalization and management: report from a Heart Failure Unit in London during the peak of the pandemic. Eur J Heart Fail. 2020;22:978–984. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.1925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dupraz J, Le Pogam M-A, Peytremann-Bridevaux I. Early impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on in-person outpatient care utilisation: a rapid review. BMJ Open. 2022;12 doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2021-056086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Czeisler MÉ, Marynak K, Clarke KE, et al. Delay or avoidance of medical care because of COVID-19–related concerns—United States, June 2020. Morb Mortality Weekly Rep. 2020;69:1250. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6936a4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fox DK, Waken RJ, Johnson DY, et al. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on patients without COVID-19 with acute myocardial infarction and heart failure. J Am Heart Assoc. 2022;11 doi: 10.1161/JAHA.121.022625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.DeFilippis EM, Psotka MA, Ibrahim NE. Promoting health equity in heart failure amid a pandemic. JACC Heart Fail. 2021;9:74–76. doi: 10.1016/j.jchf.2020.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Abedi V, Olulana O, Avula V, et al. Racial, economic, and health inequality and COVID-19 infection in the United States. J Racial Ethnic Health Disp. 2021;8:732–742. doi: 10.1007/s40615-020-00833-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vardeny O, Claggett B, Udell JA. Influenza vaccination in patients with chronic heart failure: the PARADIGM-HF trial. JACC: Heart Failure. 2016;4:152–158. doi: 10.1016/j.jchf.2015.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kadri SS, Gundrum J, Warner S, et al. Uptake and accuracy of the diagnosis code for COVID-19 among US hospitalizations. JAMA. 2020;324:2553–2554. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.20323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]