Abstract

Whilst telehealth may overcome some traditional barriers to care, successful implementation into service settings is scarce, particularly within youth mental health care. This study aimed to leverage the rapid implementation of telehealth due to COVID-19 to understand the perspectives of young people and clinicians on how telehealth impacts service delivery, service quality, and to develop pathways for future uses. Youth mental health service users (aged 12-25) and clinicians took part in an online survey exploring service provision, use, and quality following the adoption of telehealth. Service use data from the period were also examined. Ninety-two clinicians and 308 young people responded to the survey. Service use was reduced compared to the same period in 2019, however, attendance rates were higher. Across eight domains of service quality, the majority of young people reported that telehealth positively impacted service quality, and were significantly more likely to rate telehealth as having a positive impact on service quality than clinicians. There was high interest in continuing to use telehealth as part of care beyond the pandemic, supporting its permanent role in youth mental health care for a segment of service users. Future work should explore how best to support its long-term implementation.

Keywords: Telehealth, Mental health, Young people, Digital mental health

1. Introduction

Telehealth is the use of telecommunication technologies, such as telephones, videoconferencing, and the internet to provide health services (Mohr, 2009). The promise of telehealth is in its potential to overcome access-to-care barriers. In mental health, such barriers contribute to poor help-seeking, for example, 78% of young Australians with mental ill-health do not receive care (Slade et al., 2009). A growing body of evidence reports that telehealth can deliver effective mental health treatment that is acceptable to both service-users and providers (Mohr, 2009; Norman, 2006; O'Reilly et al., 2007; Richardson et al., 2009; Simon et al., 2009). Findings from meta-analyses have indicated that the efficacy and retention of telehealth for mental health treatment may be comparable to face-to-face care (Mohr et al., 2008; Osenbach et al., 2013).

The onset of mental ill-health generally occurs in adolescence and early adulthood, which highlights the importance of early intervention during this time period (Kessler et al., 2005). However, the use of telehealth in youth mental health service delivery has not been well documented to date. To our knowledge, the most recent review of telehealth in child and adolescent mental health was published in 2004, with the majority of studies being descriptive reports or case studies with a focus on feasibility (Pesämaa et al., 2004). Likewise, an updated examination of the role of telehealth for mental health in Richardson et al. (2009) noted limited additional research in the interceding years, and a more recent overview of the evidence by Bashshur et al. (2016) also reported much less research in children and adolescents. The comparatively minimal research in youth populations, particularly involving young people aged 14-25, is surprising given that young people are often championed as ‘digital natives’ with regards to technology use, making them prime candidates for technology-based mental health solutions (Burns et al., 2016).

In both adult and youth populations, effectiveness and implementation studies of telehealth delivered mental health treatment are scarce (Hilty et al., 2013), with evidence for acceptability and efficacy drawn from controlled trials and smaller studies. Despite continued calls and plans for the integration of technology into health systems (Australian Government Department of Health, 2012; Burns et al., 2016; UK Department of Health and Social Care, 2018), telehealth is underutilised within mental health services worldwide. For example, in Australia in 2018-2019, only 2.75% of visits to psychiatrists involved telehealth (Australian Government Services Australia, 2019), with government funded telehealth services subject to geographic restrictions and video format (Australian Government Department of Health, 2015). Given this implementation gap, limited information exists about how remote care mediums meet the needs of service-users and providers in real-world settings, particularly in youth mental health services where engagement can be especially problematic, and technology may be readily adopted.

Early 2020 saw the global pandemic caused by SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19) catalyse online delivery of mental health care worldwide. In Australia, due to the need for physical distancing, the Government introduced a $1.1 billion plan to ensure the continued access to essential mental health care by creating government subsidised telehealth billing structures (Australian Government Department of Health, 2020). Consequently, most young people attended sessions virtually via telehealth during this period. Given the paucity of research in telehealth for youth mental health treatment, this rapid and widespread implementation of telehealth within Australian youth mental health services provided a unique opportunity to better understand clinician and young people's perspectives on remote mental health care delivery. Harnessing this opportunity to understand the impact of telehealth on service quality from the dual perspectives of clinicians and service users, provides critical insight into not only how telehealth is received in a real-world context, but how it can be improved. These insights have implications beyond the pandemic, as the world moves towards digitally enhanced health systems that provide more options for young people to seek and receive care, in line with their needs and circumstances.

The aim of the current study was to make use of the unique opportunity offered by the rapid adoption of telehealth within youth mental health services in Australia to: 1) evaluate the impact of these changes on service quality and delivery from the perspectives of young people and clinicians, and; 2) understand the factors that clinicians take into consideration when determining whether to offer telehealth to their clients in the future. Whilst this study did not aim to address the effectiveness of telehealth, evaluating the perceived impact of telehealth services on the quality of care at the stage of implementation offers insight into the real-world impact of this medium of service delivery.

2. Methods

The study was approved by Melbourne University Human Research Ethics Committee (approval number: 2057299) and complied with the Declaration of Helsinki.

2.1. Study design and context

The study forms part of the larger BRACE project. The BRACE project examines the effect of COVID-19 on the mental health and wellbeing of young Australians, the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on primary mental health service delivery, and the potential role of technology in supporting youth mental health. Young people were consulted during survey development, which resulted in the addition of measures being incorporated throughout to capture both potentially positive and negative impacts of COVID-19 on their lives, mental health, and service use. The period of BRACE data collection corresponded to Australian Federal and State government-mandated lockdown restrictions (“Stage 3”) in which all Australians were required to ‘socially isolate’ from anyone outside their primary residence, and limited to leaving their residence for only four essential activities, defined as employment; providing care, including seeking medical care; exercise; and to shop for food and other necessary goods/services (Victoria Government, 2020). Our mental health services shifted to primarily telehealth service delivery, except where clinical considerations necessitated in person review.

The data reported here are the primary findings regarding the impact of COVID-19 on youth mental health service delivery, specifically the effects of the rapid transition to telehealth service provision on service use and quality. Young Australians aged between 12 and 25 who had a scheduled appointment at one of four headspace primary mental health services within North Western regions of Melbourne, Victoria between March 23 and June 11, 2020 were invited to complete the survey. Clinicians who provided youth mental health care at the same four Victorian headspace primary mental health services, Orygen's Primary and Specialist services, as well as two Queensland headspace primary services, during National lockdown during the same period were also invited to complete the survey.

2.2. Procedure

Eligible young people were identified using the appointment calendars of the participating headspace primary service sites. A link to an anonymous online survey was then sent via SMS on 28 May, 2020 to all those with appointments, regardless of whether the appointment was kept. A follow up reminder SMS with the survey link was sent two weeks later (11 June, 2020). Eligible clinicians were sent a link to the anonymous online survey via a clinical staff email list on May 10, 2020 (Victoria) and July 13, 2020 (Queensland), and given 18 days and 14 days to complete the survey, respectively.

Both young people and clinicians completed the survey online via Qualtrics. The surveys were created specifically for the BRACE project; one for clinical staff delivering mental health services to young people and another for young people who were clients of the service, covering identical themes. Survey measures related to this paper's focus on service delivery and quality are described in the measures section below.

2.3. Measures

2.3.1. Service use

-

•

Service attendance and cancellation rates during the lockdown period (March through June, 2020) relative to the same period 12-months prior; and

-

•

Clinician and young people's perspectives on willingness to engage with remote service delivery.

2.3.2. Service quality

-

•

Clinician and young people's perceptions of the impact of telehealth changes on eight service quality domains derived from the National Standards for Mental Health Services (Australian Government Department of Health, 2010);

-

•

Young people's perspectives on the impact of telehealth on the therapeutic relationship;

-

•

Clinicians’ perspectives on the ability to assess risk and provide therapeutic care via telehealth; and

-

•

Young people's reports of technical difficulties experienced during telehealth appointments.

2.3.3. Interest in and clinical considerations of telehealth service provision

-

•

Clinicians’ indicated level of interest in using telehealth in the future with clients, and

-

•

Responses to open-ended questions regarding their main considerations when determining appropriateness of telehealth services for clients.

All quantitative items were measured on Likert scales, with anchors varying depending on the question, as specified in the results. A full copy of the survey is available from authors.

2.4. Data analysis

Quantitative data were analysed using descriptive statistics in SPSS 22.0. Chi-square statistics were used to examine differences in categorical data between clinicians and young people. For analysis and reporting, responses to Likert scales were collapsed to signify those who thought telehealth had a negative, no, or positive impact on the variable in question.

Qualitative data were analysed using qualitative content analysis, an approach that enables the systematic categorisation and summarisation of large volumes of text-based data, and assists in interpreting patterns, with attention given to the context from which sample data is drawn (Crowe et al., 2015). An inductive approach was used, as recommended for areas with little extant research (Elo and Kyngäs, 2008). First, for each of the qualitative question responses, two study team members (HS and PS) read through participant responses to familiarise themselves with the data set and performed open coding to create categories based on reoccurring responses. Team members subsequently met to compare and discuss these first-stage categories; reach agreement regarding appropriate coding; categories; and create higher order categories. The remaining responses were coded into the final categories. The team then met to discuss the coded responses before the findings were consolidated. To ensure validity and rigour within the analysis, the team-based approach allowed for analyst triangulation, such that categories at every step of the analysis and reporting were determined by consensus among the researchers (Tracy, 2010). Further, throughout coding and interpretation of data, reflective logs and memos were used. The identified categories and sub-categories along with a short description and representative quotes are outlined in the results.

3. Results

3.1. Sample characteristics

The survey link was sent to approximately 370 clinicians and completed by 92, a completion rate of 25%. The SMS survey link was sent to a total of 1868 young people, 308 of which started the survey, representing a response rate of 17%. The final sample consisted of 92 clinicians across Orygen Specialist and Primary services and 308 young people (age range 12-25) who were users of the service. Demographic characteristics of the youth sample are displayed in Table 1 .

Table 1.

Characteristics of service users (n=308).

| Characteristic | Young people n(%)$ |

|---|---|

| Age M(SD) | 18.6 (3.4) |

| Gender | |

| Female | 193 (62.7) |

| Male | 84 (27.3) |

| Transgender | 11 (3.6) |

| Non-binary | 7 (2.3) |

| Unspecified | 13 (4.2) |

| Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander | 7 (1.8) |

| Current living situation | |

| Living with parents, caregivers, or siblings | 260 (84.4) |

| Living with friends | 3 (1.0) |

| Living with romantic partner | 15 (4.9) |

| Living in shared accommodation | 13 (4.2) |

| Living alone | 14 (4.5) |

| Homeless or couch surfing | 3 (1.0) |

| Employment status% | |

| Full time student | 170 (55.2) |

| Part time student | 20 (6.5) |

| Number of hours study each week M(SD) | 22.0 (17.1) |

| Full-time worker in paid employment | 16 (5.2) |

| Part-time worker in paid employment | 43 (14.0) |

| Number of hours paid work each week M(SD) | 19.6 (12.4) |

| Unpaid worker as a parent or carer | 1 (0.3) |

| Number of hours unpaid each week | 0 (0) |

| Currently unemployed | 94 (30.5) |

| Number of hours engaged in job seeking each week M(SD) | 4.6 (7.2) |

Unless otherwise indicated.

Categories are not mutually exclusive.

3.2. Service use

3.2.1. Service attendance and cancellation rates

Attendance and cancellation rates for the Victorian headspace primary mental health service settings between the four-month time period from March to June in 2020 and 2019 are displayed in Table 2 . These data indicate that there were fewer total occasions of service during the pandemic than the same period of the prior year, with slightly fewer number of occasions of service per young person (2019: 1.6, 2020: 1.5). However, the cancellation rate was lower per young person (2019: 0.26, 2020: 0.18) and lower as a proportion of the total occasions of service (2019: 16%, 2020: 11%).

Table 2.

A comparison of attendance and cancellation rates during a four-month period in 2020 during pandemic, and the same time period in 2019 prior to pandemic.

| March – June 2019 | March – June 2020 | |

|---|---|---|

| Young people served | 5,626 | 3,753 |

| Occasions of service | 9,172 | 5,625 |

| Occasions of cancelled service | 1,488 | 662 |

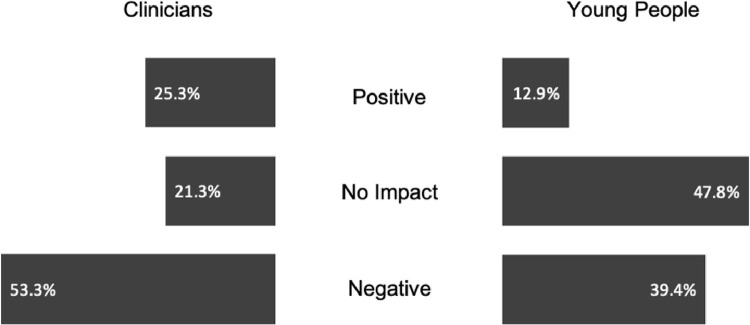

Clinicians and young people differed in their perceptions of how the shift to telehealth had impacted willingness or motivation to engage with the service (Figure 1 ). A Chi-square test for independence indicated that this difference was significant χ2 (2, n = 324) = 18.03, p < .001, Cramer's V = .24, with young people more likely to perceive the change to telehealth as not impacting their willingness or motivation to attend services compared to clinicians.

Fig. 1.

Percentage of clinicians and young people with positive, neutral or negative perceived impact of telehealth changes on willingness or motivation to engage with the service.

3.3. Service quality

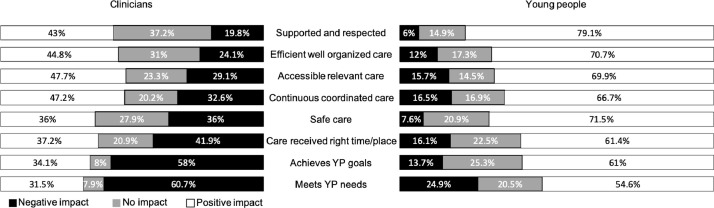

Clinicians and young people's perspectives of the impact of telehealth across domains of service quality are presented in Figure 2 . For each of the quality domains assessed, Chi square tests indicated that young people were significantly more likely to rate telehealth as having a positive impact on service quality than clinicians (all p < .002).

Fig. 2.

Impact of telehealth on service quality domains from the perspectives of young people and clinicians.

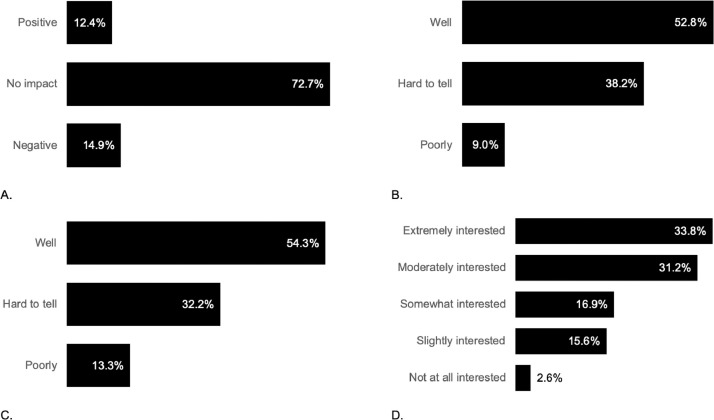

The extent to which young people felt the shift to telehealth impacted their relationship with their clinician, and the extent to which clinicians felt they were able to assess risk and provide adequate therapeutic care over telehealth are presented in Figure 3 , A, B, and C respectively. Overall, the majority of clinicians felt they could perform these clinical duties remotely, and young people reported that the shift to telehealth had not impacted their relationship with their clinician.

Fig. 3.

A. Young people's perspectives on the impact of telehealth on their relationship with their clinician. Clinicians’ perspectives on their ability to manage risk (B), and provide adequate therapeutic care (C) over telehealth. D. Clinicians’ level of interest in continuing to use telehealth to provide care to some of their clients after the pandemic.

Thirty-one percent of young people reported experiencing technical difficulties during their telehealth appointment, the majority of which were brief in nature and resolved within session. Of those reporting a technical difficulty, the most common was the platform being unstable or having poor usability (53.5%). Other problems reported regarded internet connectivity (43.7%), challenges to scheduling or running telehealth sessions (25.4%), technology access issues (11.3%), and challenges around technology literacy or support (4.2%).

3.4. Interest and clinical considerations of telehealth service provision

The majority of clinicians (65%) expressed high levels of interest in continuing to use telehealth to provide care to some of their clients beyond the pandemic (Figure 3D). Content analysis of open response questions indicated that clinicians reported a variety of factors to consider in their decision to recommend telehealth in the future, with themes and frequencies outlined in Table 3 .

Table 3.

Themes and subthemes identified during the content analysis of clinicians open-ended responses regarding factors they would consider when determining whether to offer telehealth to a future client.

| Main themes | Sub-Themes | Description | Quote | n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Preferences | Young person willingness/ engagement | Preference of the young person and their willingness to engage with telehealth compared to in-person appointments, including a lack of appeal for telehealth due to discomfort with features (e.g. being on camera), difficulties with within-session engagement over telehealth, and telehealth increasing accessibility. | “[Young person's]’s strong preference for face-to-face [sessions].”"Most [are] comfortable engaging from their houses." | 89 (97%) |

| Clinician willingness | Preference of the clinician for telehealth compared to in-person appointments, including comfort with technology, additional administrative burdens such as difficulties setting up appointments, impacts such as fatigue from video conferencing platforms, the appeal of working remotely, and its consequences for work life balance and connection with a team environment. | “Very taxing [for] clinician[s] to be staring at a screen all day.”“The impact of online appointments on clinician job satisfaction and burnout”“Own preference for face-to-face” | 20 (22%) | |

| Client Risk & Safety | Complexity/acuity/risk level | Clinicians considered telehealth inappropriate for clients presenting with complex problems, such as psychosis, suicidality, recent history of hospitalisation, or those experiencing acute symptoms. | “Risk level (may not be suitable alterative for [young person] presenting with moderate-severe risk)” | 81 (88%) |

| Assessment & management of Risk | Assessing and managing challenging clinical scenarios including risk and ensuring client safety was considered more difficult through telehealth, particularly through a lack of visual observation needed for risk assessment and the ability to manage emotions or difficulties. Clients must have a safe home environment in which to participate in telehealth. | “Risk assessment reliant on engagement in-person e.g. physical appearance, affect – I would need additional training and supervision regarding synthesising available information in [a] video call.” | 42 (46%) | |

| Accessibility | Technology access & resources | Access to the required technology to run telehealth is critical, including a computer or smartphone with microphone, video, internet and/or data required to access telehealth sessions. | “If a young person doesn't have the necessary resources for telehealth (technology, privacy etc).” | 54 (59%) |

| Safe private space | Clients need access to a safe and private environment in the home in order to receive telehealth sessions and meaningfully engage in the therapeutic process. Shared living, homelessness, or limited space were clear barriers. | “Privacy / confidentiality; challenges for many young people in ensuring they have a safe, private space at home” | 41 (45%) | |

| Facilitating engagement | Telehealth can increase service accessibility for some clients. Telehealth could assist young people overcome barriers related to physical location (rural/ out of catchment area), travel time, transport access, health issues, caregiving responsibilities, significant mental health symptoms, crises such as homelessness, and financial difficulties. | “If using telehealth would overcome barriers that would otherwise prevent a young person from engaging (e.g., inability to attend the centre due to not having access to transport, disability)” | 31 (34%) | |

| Communication | Language and communication barriers, such as lack of interpreters for young people and families for whom English is an additional language, and symptoms related to psychosis and communication (e.g. thought disorder and dissociative symptoms). | “Barriers to clear communication”“Challenges integrating services provided in person e.g. interpreting” | 5 (5%) | |

| Therapeutic Process | Therapeutic risk/benefit | Therapeutic risk versus benefit needs to be determined, considering whether telehealth delivery may be counter-therapeutic due to enabling avoidance or inactivity. For some clients, telehealth may offer a graded step in receiving care. | "Therapeutic benefit to having clients attend face-to-face sessions e.g. needing to be organised and motivated enough to travel…and attend on time." | 48 (52%) |

| Therapeutic approach | Some therapeutic approaches are better suited to in-person therapy, e.g. trauma or cognitive analytic therapy, appeared linked to complexity of the therapy or ability to manage potentially negative responses. | “Needing specific therapeutic approach which is better offered in person (i.e.: trauma-focused work to ensure safety/containment)” | 32 (35%) | |

| Therapeutic alliance | Therapeutic alliance may be more difficult to establish on telehealth with young people, particularly at early stages of building rapport, suggesting telehealth may be more appropriate following initial in-person sessions. | "I do not yet feel confident that I can establish rapport and engagement with young people…via telehealth in the same way that I can in-person." | 27 (29%) |

4. Discussion

This paper reports the findings of a survey to evaluate the perceived impact of telehealth service delivery on the quality of youth mental health primary care services during COVID-19. Across eight domains of care quality, the perspectives of young service users and clinicians on the impact of telehealth on service quality significantly differed. Young people were significantly more likely to rate telehealth as having a positive impact on service quality than clinicians. Indeed, the majority of young people indicated that telehealth had a positive impact on quality in each of the eight domains, foremost the degree to which they felt supported and respected. Clinicians were also generally supportive of telehealth, with the majority believing it had a positive or no impact on service quality. Importantly to the high need and historically limited access to services within this population (Reavley et al. 2010), the majority of clinicians (65%) expressed high levels of interest in continuing to provide care via telehealth in the future. However, an examination of attendance rates indicated that there were slightly fewer occasions of service when delivered via telehealth, compared to the same timeframe in 2019, balanced against proportionally lower cancellation rates.

The high proportion of young people that perceived the change to telehealth service delivery as having a positive impact on service quality and the lower cancellation rates during this time, supports the feasibility and acceptability of telehealth having an ongoing role in youth mental health care. This fits with findings from prior research showing high levels of satisfaction with telehealth amongst youth populations (Boydell et al., 2014). One randomised controlled trial (RCT) found that young people preferred cognitive behavioural therapy for depression when it was delivered via videoconferencing compared to face-to-face, while both were equally effective (Nelson et al., 2003). Survey research has also suggested that alongside high rates of ownership and usage of digital technologies amongst young people, there is also interest in their use for mental health and wellbeing (Burns et al., 2016). Supporting this, qualitative studies suggest that young people view technology as engaging, easy-to-access, informative, and empowering (Montague et al., 2015). Of particular importance to the potential role of telehealth, is the finding that over two thirds reported telehealth had a positive impact on how respected, supported and safe they felt, and how accessible, relevant, efficient, and coordinated the care was.

Young people's overall positive attitudes towards telehealth are important in the context of the trepidation clinicians often describe towards technology supported health services (Lattie et al., 2020). This perspective appeared to be reflected in the current findings, with clinicians less positive about the impact of telehealth on care quality across most domains. These findings are also consistent with prior research that described the attitudes of clinical staff towards technology supported care as ‘cautiously optimistic’ (Berry et al., 2017). Whilst overall clinicians appeared to hold more negative views regarding the impact of telehealth on services, there was variability in opinion. Although this variability was most evident amongst clinicians, a proportion of young people also reported that telehealth negatively impacted service quality across various domains (6-25%). These findings underscore that technological approaches are not a universal solution to mental ill-health, but instead another tool in the box, with telehealth not suitable or appealing to all young people.

The qualitative findings provide further detail regarding the perceptions amongst clinicians, reporting a number of pertinent considerations for the appropriateness of telehealth for young people. Most clinicians indicated that telehealth was not appropriate for young people with very complex or high-risk presentations, or those without access to the required technology or an appropriate environment to receive services. There were also clear individual preferences amongst young people and clinicians, with ability to establish rapport and maintain engagement with young people an important factor. Clinicians also shared insights into the therapeutic risks and benefits of telehealth, highlighting that it provided a gateway to treatment for clients who were difficult to reach, but may perpetuate avoidance or inactivity for others. For example, many clinicians highlighted that the act of coming to in-person appointments was therapeutic in itself and they would not want to remove this option for some clients, even if clients would be more comfortable with telehealth, while for others telehealth could be used as a graded exposure to eventual in-person care. Moreover, some therapeutic modalities were seen as less amenable to video format, particularly those whereby adverse reactions may need to be carefully monitored and managed (e.g. trauma exposure). This rich level of insight has not traditionally been captured within implementation studies and clearly points to a need for further research to establish what and for whom telehealth may and may not be suited.

Despite differences in opinions about how telehealth impacted the quality of care, almost all clinicians (98%) were at least slightly interested in continuing to use telehealth, with two thirds reporting very high levels of interest. Clinicians and young people clearly perceive significant advantages to telehealth, supporting its continued use beyond the pandemic. There are, however, important remaining issues to be addressed. First, technological issues were reported as common, albeit brief and resolvable, and the available telehealth platforms were not entirely suited to the needs of clinicians and young people, suggesting that more stable and purpose-built solutions are needed. This is particularly important in context of broader findings in the digital mental health literature that engagement and usage are improved when technologies are designed for, and alongside, the end user (Garrido et al., 2019). Telehealth platforms that are more fun and appealing to young people, such online virtual environments (Bell et al., 2020; Thompson et al., 2020), might offer powerful tools to increase engagement with services (Burns and Birrell, 2014). Second, as previously mentioned, telehealth is not suited to all young people and further research is needed, drawing on the valuable ‘on-the-ground’ experiences of clinicians and different groups of young people with varying needs. Findings of this study show that the occasions of service decreased compared to the same period in the year prior, which could suggest that a smaller proportion of young people are willing to receive services over telehealth. Further consideration is needed for those in which telehealth is not likely to be appropriate, including those from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds, lower socio-economic status, those with disabilities that may limit capacity to use technology, and young people with particular mental health experiences that may make technology less acceptable (e.g. fearful beliefs about technology, difficulties focusing attention, or impulsive or high-risk behaviours). Finally, additional time burdens for telehealth, technical challenges, and some issues raised regarding usability, reflect a need for better training and infrastructure supporting implementation.

This study had several important limitations. First, response rates for the survey among clinicians and young people were relatively low, limiting the generalisability of the results whilst reflecting good levels for an anonymous quality assurance survey, where those invited were not incentivised to complete the survey. Second, this was a sample of young people who are likely to be existing users of technology, based in a metropolitan area of Melbourne, and it is difficult to determine how generalisable these findings are to a broader population of young people. In particular, the sample consisted of young people who had scheduled an appointment during the pandemic, potentially representing those most willing to receive care this way. However, we did include young people who did not attend appointments they had booked, potentially capturing those who disengaged due to remote delivery. The higher proportion of females within the sample is reflective of the composition of young people who accessed headspace youth mental health services in 2019/2020 (Headspace, 2020). Given young people in rural and remote regions are likely to benefit most from telehealth services, due to the relative lack of service provision, it is important that future research capture perspectives from staff and young people in these regions. Third, whilst it was highly opportunistic to study the implementation of telehealth through its rapid adoption within mental health services at the current time, this is a moment in history of unique transition. Given the circumstances, time for comprehensive planning and training was not available, which may have impacted findings, particularly among clinicians. Further, it is difficult to say what these findings will mean in the context of ‘the new normal’ awaiting the other side of the global pandemic. However, they do offer some clarity for what it should look like, most strikingly that telehealth should form some part of the future of youth mental health care in Australia. Finally, these findings are merely observational and a controlled trial is needed to confirm whether service quality significantly differs between modalities. However, the current findings support prior RCTs showing that telehealth services in adult populations can be equally as effective as face-to-face mental health care, are acceptable to service users, and have potential for cost savings (Mohr, 2009; Norman, 2006; O'Reilly et al., 2007; Osenbach et al., 2013; Richardson et al., 2009; Simon et al., 2009). Further trials in youth populations are needed.

The current research provides an important snapshot of what it looks like when telehealth is adopted within youth mental health services. The findings reflect the readiness of youth services to accept technology to support service delivery, however further investigation into the potential of other digital technologies for enhancing youth mental health care is required. This is particularly important considering that telehealth is merely a different delivery vehicle for a form of service that faces considerable capacity limitations. More novel, innovative technologies, such as smartphone apps, online programs or even in future, virtual reality, might further enhance the quality and reach of youth mental health services within a new model of ‘blended care’ (Bell and Alvarez-Jimenez, 2019; Burns and Birrell, 2014). Central to this is a system which values and strives for innovation in purposing novel solutions for mental ill-health, alongside a commitment to valuing the lived experience and perspectives of young people and clinicians. Further research is needed at this point to determine how best the system can officially adopt telehealth moving forward, including determining who it is appropriate for and building infrastructure to support its long-term implementation.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors. JN is supported by the National Health and Medical Research Council Centre of Research Excellence in Prevention and Early Intervention of Mental Illness and Substance Use (PREMISE; APP1134909).

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Jennifer Nicholas: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Methodology, Investigation, Supervision, Project administration, Writing - original draft. Imogen H. Bell: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Methodology, Investigation, Supervision, Project administration, Writing - original draft. Andrew Thompson: Resources, Supervision, Writing - review & editing. Lee Valentine: Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing - review & editing. Pinar Simsir: Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing - review & editing. Holly Sheppard: Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing - review & editing. Sophie Adams: Conceptualization, Methodology, Resources, Supervision, Writing - review & editing.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The Authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to thank Brendan Pawsey and Irene Opasinov for their assistance disseminating the survey to young people and collecting service use data. We also are grateful to the young people and clinical staff who gave their time to provide feedback on the service changes.

References

- Australian Government Department of Health, 2010. Implementation guidelines for non-government community services. Australian Government. https://www1.health.gov.au/internet/publications/publishing.nsf/Content/mental-pubs-i-nongov-toc~mental-pubs-i-nongov-how#nat (Accessed on 27 Nov 2020).

- Australian Government Department of Health, 2012. E-mental health strategy for Australia. Australian Government. https://www1.health.gov.au/internet/main/publishing.nsf/Content/mental-teleweb (Accessed on 27 Nov 2020).

- Australian Government Department of Health, 2015. MBS Online, Medicare Benefits Schedule, Medicare Rebates for Specialist Video Consultations. http://www.mbsonline.gov.au/internet/mbsonline/publishing.nsf/Content/connectinghealthservices-Program±Overview (Accessed on 27 Nov 2020).

- Australian Government Department of Health, 2020. COVID-19 temporary telehealth MBS services. http://www.mbsonline.gov.au/internet/mbsonline/publishing.nsf/Content/0C514FB8C9FBBEC7CA25852E00223AFE/$File/COVID-19%20Temporary%20MBS%20telehealth%20Services%20-%20Mental%20Health%2008052020.pdf (Accessed on 27 Nov 2020).

- Australian Government Services Australia, 2019. Requested Medicare items processed from July 2018 to June 2019. http://medicarestatistics.humanservices.gov.au/statistics/do.jsp?_PROGRAM=%2Fstatistics%2Fmbs_item_standard_report&DRILL=ag&group=288&VAR=services&STAT=count&RPT_FMT=by±state&PTYPE=finyear&START_DT=201807&END_DT=201906 (Accessed on 27 Nov 2020).

- Bashshur R.L., Shannon G.W., Bashshur N., Yellowlees P.M. The Empirical Evidence for Telemedicine Interventions in Mental Disorders. Telemedicine journal and e-health: the official journal of the American Telemedicine Association. 2016;22:87–113. doi: 10.1089/tmj.2015.0206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell I.H., Alvarez-Jimenez M. Digital technology to enhance clinical care of Early Psychosis. Current Treatment Options in Psychiatry. 2019;6:256–270. [Google Scholar]

- Bell I.H., Nicholas J., Alvarez-Jimenez M., Thompson A., Valmaggia L. Virtual reality as a clinical tool in mental health research and practice. Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience. 2020;22:169. doi: 10.31887/DCNS.2020.22.2/lvalmaggia. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berry N., Bucci S., Lobban F. Use of the internet and mobile phones for self-management of severe mental health problems: Qualitative study of staff views. JMIR Mental Health. 2017;4:E52. doi: 10.2196/mental.8311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boydell K.M., Hodgins M., Pignatiello A., Teshima J., Edwards H., Willis D. Using technology to deliver mental health services to children and youth: a scoping review. Journal of the Canadian Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2014;23:87. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burns J., Birrell E. Enhancing early engagement with mental health services by young people. Psychology Research and Behavior Management. 2014;7:303–312. doi: 10.2147/PRBM.S49151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burns J.M., Birrell E., Bismark M., Pirkis J., Davenport T.A., Hickie I.B., Ellis L.A. The role of technology in Australian youth mental health reform. Australian Health Review. 2016;40:584–590. doi: 10.1071/AH15115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crowe M., Inder M., Porter R. Conducting qualitative research in mental health: Thematic and content analyses. ANZJP. 2015;49:616–623. doi: 10.1177/0004867415582053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elo S., Kyngäs H. The qualitative content analysis process. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2008;62:107–115. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04569.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garrido S., Millington C., Cheers D., Boydell K., Schubert E., Meade T., Nguyen Q.V. What works and what doesn't work? A systematic review of digital mental health interventions for depression and anxiety in young people. Frontiers in Psychiatry. 2019;10:759. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Headspace, 2020. headspace year in review 2019-2020. https://headspace.org.au/assets/HSP10755_Year-in-Review-2020_FA05_DIGI.pdf (Accessed on 9 Feb 2021).

- Hilty D.M., Ferrer D.C., Parish M.B., Johnston B., Callahan E.J., Yellowlees P.M. The effectiveness of telemental health: A 2013 review. Telemedicine Journal and E-health: the Official Journal of the American Telemedicine Association. 2013;19:444–454. doi: 10.1089/tmj.2013.0075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler R.C., Berglund P., Demler O., Jin R., Merikangas K.R., Walters E.E. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Archives of general psychiatry. 2005;62(6):593–602. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lattie E., Nicholas J., Knapp A., Skerl J., Kaiser S., Mohr D. Opportunities for and tensions surrounding the use of technology-enabled mental health services in community mental health care. Administration and Policy in Mental Health. 2020;47:138–149. doi: 10.1007/s10488-019-00979-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohr D. Telemental health: Reflections on how to move the field forward. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 2009;16:343–347. [Google Scholar]

- Mohr D., Vella L., Hart S., Heckman T., Simon G. The effect of telephone-administered psychotherapy on symptoms of depression and attrition: A meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology-Science and Practice. 2008;15:243–253. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2850.2008.00134.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montague A., Varcin K., Simmons M., Parker A. Putting technology into youth mental health practice: Young people's perspectives. SAGE Open. 2015;5:1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson E.L., Barnard M., Cain S. Treating childhood depression over videoconferencing. Telemedicine Journal and E-health. 2003;9:49–55. doi: 10.1089/153056203763317648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norman S. The use of telemedicine in psychiatry. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing. 2006;13:771–777. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2850.2006.01033.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Reilly R., Bishop J., Maddox K., Hutchinson L., Fisman M., Takhar J. Is telepsychiatry equivalent to face-to-face psychiatry? Results from a randomized controlled equivalence trial. Psychiatric Services. 2007;58:836–843. doi: 10.1176/ps.2007.58.6.836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osenbach J.E., O'Brien K.M., Mishkind M., Smolenski D.J. Synchronous telehealth technologies in psychotherapy for depression: A meta-analysis. Depression and Anxiety. 2013;30(11):1058–1067. doi: 10.1002/da.22165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pesämaa L., Ebeling H., Kuusimäki M., Winblad I., Isohanni M., Moilanen I. Videoconferencing in child and adolescent telepsychiatry: A systematic review of the literature. Journal of Telemedicine and Telecare. 2004;10:187–192. doi: 10.1258/1357633041424458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reavley N., Cvetkovski S., Jorm A., Lubman D. Help-seeking for substance use, anxiety and affective disorders among young people: Results from the 2007 Australian national survey of mental health and wellbeing. ANZJP. 2010;44:729–735. doi: 10.3109/00048671003705458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson L., Christopher Frueh B., Grubaugh A., Egede L., Elhai J. Current directions in videoconferencing tele-mental health research. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 2009;16:323–338. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2850.2009.01170.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon G., Ludman E., Rutter C. Incremental benefit and cost of telephone care management and telephone psychotherapy for depression in primary care. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2009;66:1081–1089. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slade T., Johnston A., Oakley Browne M.A., Andrews G., Whiteford H. 2007 National Survey of Mental Health and Wellbeing: methods and key findings. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. 2009;43:594–605. doi: 10.1080/00048670902970882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson A., Elahi F., Realpe A., Birchwood M., Taylor D., Vlaev I., Bucci S. A feasibility and acceptability trial of Social Cognitive Therapy in Early Psychosis delivered through a Virtual World: The VEEP study. Frontiers in Psychiatry. 2020;11:219. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tracy S. Qualitative quality: Eight “big-tent” criteria for excellent qualitative research. Qualitative Inquiry. 2010;16:837–851. [Google Scholar]

- UK Department of Health and Social Care, 2018. The future of healthcare: our vision for digital, data and technology in health and care. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/the-future-of-healthcare-our-vision-for-digital-data-and-technology-in-health-and-care/the-future-of-healthcare-our-vision-for-digital-data-and-technology-in-health-and-care (Accessed on 3 Dec 2020).

- Victoria Government, 2020. Coronavirus (COVID-19) roadmap for reopening. https://www.coronavirus.vic.gov.au/coronavirus-covid-19-restrictions-roadmaps (Accessed on 27 Nov 2020).