Abstract

The COVID-19 pandemic and corresponding public health mitigation strategies have altered many facets of human life. And yet, little is known about how public health measures have impacted complex socio-ecological systems such as recreational fisheries. Using an online snowball survey, we targeted resident anglers in Ontario, Canada, to obtain preliminary insights on how the pandemic has impacted recreational fishing and related activity. We also explored angler perspectives on pandemic-related restrictions and other aspects of fisheries management. Our results point to the value of recreational fisheries for the mental and physical well-being of participants, as well as the value and popularity of outdoor recreation during a pandemic. Although angling effort and fish consumption appeared to decline during the early phases of the pandemic, approximately 21 % of the anglers who responded to our survey self-identified as new entrants who had begun or resumed fishing in that time. Self-reported motivations to fish during the pandemic suggest that free time, importance to mental and physical health, and desires for self-sufficiency caused some anglers to fish more, whereas a lack of free time, poor or uncertain accessibility, and perceived risks caused some anglers to fish less. Respondents also expressed their desires for more clear and consistent communication about COVID-19 fishing restrictions from governments, and viewed angling as a safe pandemic activity. Information on recreational angler behaviours, motivations, and perspectives during the pandemic may prove valuable to fisheries managers and policy makers looking to optimize their strategies for confronting this and other similar crises.

Keywords: Coronavirus, Pandemic, Angling, Fisheries management, Lockdown, Communications

1. Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has altered many facets of human life profoundly on both local and global scales. Restrictions aimed at limiting the spread of the virus have not only changed how humans interact with each other, but also with the natural world. Lockdown measures such as shelter at home orders, and the curtailing of transportation (i.e., global trade, business travel, tourism; Bakar and Rosbi, 2020; Chakraborty and Maity, 2020) during the early phase(s) of the pandemic led to such dramatic changes in human-environment interactions that some are now referring to this period of reduced human mobility and activity as the “Anthropause” (Rutz et al., 2020). Efforts to characterize the Anthropause’s effect(s) on biodiversity (relative to the Anthropocene; Steffen et al., 2007) and the environment are underway (e.g., Bates et al., 2020; Buckley, 2020; Corlett et al., 2020; Diffenbaugh et al., 2020).

Recreational angling is a globally popular activity, and has significant cumulative effects on ecosystems and the environment (Arlinghaus and Cooke, 2009; FAO, 2012). Given that recreational angling can involve travel, group congregation, and organized events, participation has likely been affected by the pandemic and corresponding restrictions. Impacts may be even more significant in densely populated areas (Rice et al., 2020). In particular, lockdowns are likely to have impacted fishing effort, as they involved strict prohibitions against non-essential travel, along with other typical parts of recreational fishing and related activities. Also note-worthy, is the fact that regulators in some jurisdictions have sought to reduce the spread of COVID-19 by cancelling permits for competitive fishing events, as well as closing boat ramps, marinas, and other access points used for fishing (Paradis et al., 2021). However, restrictions have been modified and eased over time, and recreational fishing effort has fluctuated and increased accordingly. Despite this, little is known about the effects of the pandemic on the recreational fishing sector, and more specifically, angler and government agency responses.

Given that the pandemic will persist in some form for years, and that an increase in pandemic frequency is anticipated in the future (Billington et al., 2020), there is an urgent need to learn from current and ongoing experiences. For instance, it is important for researchers and regulators to know how the pandemic is affecting the behaviours and perceptions of individuals and groups as they navigate new life circumstances and social norms (Standl et al., 2020). More generally, the current moment provides an opportunity to understand what lessons can be drawn from the Anthropause for the management of recreational fisheries in the future. Currently, fisheries scientists are learning about the impacts of the Anthropause on fisheries using traditional stock assessment tools (e.g., creel surveys, netting surveys; Cooke et al., 2021). Similarly, much can be learned about the human dimensions of the pause by using social science research methods. Angler perspectives are important predictors of behaviour and compliance, as well as major determinants of policy success (Hunt et al., 2013; Nguyen et al., 2016). Moreover, given that government restrictions on fishing have been met with opposition from some members of the angling community (Paradis et al., 2021), it is worth conducting a retrospective analysis of this strategy and its result(s).

The purpose of our study was to assess the effect(s) of the pandemic on recreational angler practices and perspectives. We conducted an online snowball survey designed to provide preliminary information and an exploratory analysis of angler perspectives, experiences, and behaviours related to the impact(s) of COVID-19 on recreational fishing in Ontario, Canada. As such, it is important that readers regard our results as preliminary, and use them cautiously (e.g., to generate new hypotheses, to identify relevant considerations). Ontario is home to nearly 1 million resident anglers, and more than 1 million anglers—both resident and non-resident—fish in Ontario annually (Government of Ontario, 2020). Approximately 1.5 billion Canadian dollars (CAD) are spent annually on recreational fishing by Ontario anglers (Canada, Fisheries and Oceans, 2019). Angling also supports a vibrant tourism industry in Ontario, although travel restrictions prevented international travel to Ontario during the study period. Our research provides a snapshot of the pandemic’s effect(s) on Ontario’s vast, multitudinous, and both socio-economically and culturally significant recreational fisheries.

1.1. The case

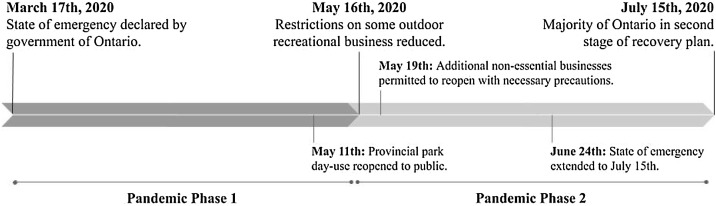

On March 17th, 2020, the government of Ontario declared a state of emergency in response to COVID-19 outbreaks, curtailing all non-essential activities and gatherings related to work, education, social interaction, and entertainment (e.g., schools, restaurants, entertainment venues, parks). After more than one month in lockdown, select businesses, public facilities, and services were allowed to resume and begin gradually reopening in the month of May. Provincial park day use, for example, was reopened to the public on May 11th. On May 16th, restrictions on several other outdoor recreational businesses and activities (e.g., marinas, camping) were loosened, and many more businesses were allowed to reopen three days later, on May 19th (Nielsen, 2020). Select regions of Ontario began entering the next stage of the province’s recovery plan during the month of June, while more strict pandemic procedures were maintained in densely populated areas (e.g., Toronto). On June 24th, the Ontario government extended the state of emergency to July 15th. Some areas of Ontario began entering the third stage of the province’s recovery plan in late July.

Due to major differences in pandemic restrictions between the initial province-wide lockdown and the subsequent ‘reopening’ phase, we chose to study the effect(s) of the pandemic on recreational fisheries during two distinct time periods: March 17th to May 16th, and May 16th to July 15th. This division of study periods allowed us to compare and distinguish the impacts of the pandemic during two important phases lasting ∼60 days, and helps capture the most significant changes that affected the highest number of Ontarians. To minimize confusion, we refer to the first distinguished period from March 17th to May 16th as Pandemic Phase 1, and the second period from May 16th to July 15th as Pandemic Phase 2, for the remainder of this article (Fig. 1 ).

Fig. 1.

Ontario pandemic lockdown and response timeline. The first ∼60 day period is referred to as ‘Pandemic Phase 1′ or ‘Phase 1′ for the remainder of this article, and the second ∼60 day period is referred to similarly, as ‘Pandemic Phase 2′ or ‘Phase 2.’.

2. Methods

We used an online survey with purposive snowball-style recruitment (i.e., using participant referrals to build the sample; Penrod et al., 2003) to target resident anglers in Ontario, Canada. Non-random recruitment was necessary because it was not possible to gain access to the provincial license database (it is used as part of a national survey (Brownscombe et al., 2014) and managers of the database did not share the contact information for licensees due to their concerns about potential respondent fatigue), nor was a broader mail or telephone survey possible given the lack of quick-turnaround funding opportunities. Although some scholars have been critical of online snowball-style surveys (e.g., Duda and Nobile, 2010), there is a growing volume of research testing the validity of this method (e.g., Baltar and Brunet, 2012; Brickman Bhutta, 2012; Kosinski et al., 2015; Forgasz et al., 2018; Schneider and Harknett, 2019). Snowball-style surveys involve a validity trade-off. On the one hand, non-random sampling means we cannot infer that the population of respondents is representative of a larger population (Szolnoki and Hoffmann, 2013). On the other hand, research has found that online snowball-style surveys are highly effective for accessing subpopulations and hard-to-reach groups that may be missed with random or stratified-random sampling (Brickman Bhutta, 2012; Schneider and Harknett, 2019), for example casual, occasional, or new anglers (Griffiths et al., 2010). We acknowledge this trade-off and consider our results to be exploratory and preliminary, thus we are prudent not to make inferences from our results to the broader population of Ontario anglers. We also acknowledge the limited reach of online snowball surveys which can online reach those who have internet (Szolnoki and Hoffmann, 2013). However, our strategies align with the conclusion that social media is best able to recruit individuals for survey-type studies (Topolovec-Vranic and Natarajan, 2016).

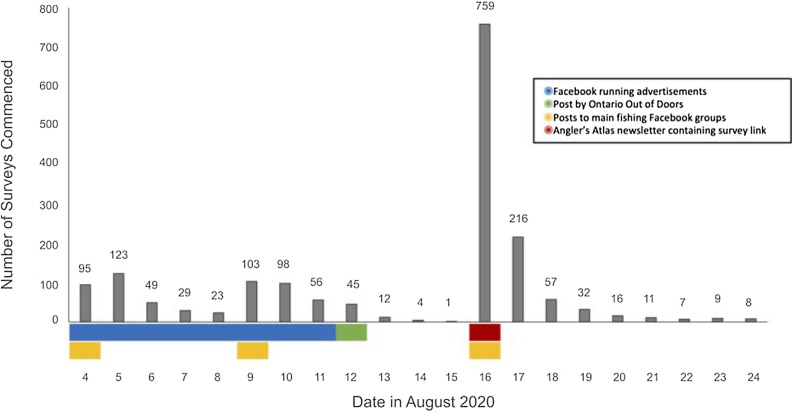

Respondents were recruited in several ways, showcasing the seed diversity (Kirchherr and Charles, 2018) of our multipronged approach. First, we shared the survey link to the ∼13,000 members on the Ontario Fishing Club Facebook group and the ∼40,000 members on the Fishing Ontario Facebook group. Next, we used paid Facebook advertisements targeting users from Ontario who included recreational fishing as a topic of interest and were between the ages of 18 and 65. We also partnered with the organization Anglers Atlas which maintains an email list of over 20,000 active members in Ontario to distribute the survey link via email. We also collaborated with a major fishing magazine in Ontario (i.e., Ontario Out of Doors) to develop a news item that was shared on their online site (see https://oodmag.com/researchers-surveying-angler-behaviour/). These activities were supplemented with posts to Twitter, Instagram, and Facebook by members of the research team, thus leveraging prior contacts which has been shown to be helpful in snowball sampling (Kirchherr and Charles, 2018). Respondents were encouraged to share the survey with their peers (e.g. Ontario anglers). We began recruitment on August 4th 2020 and ceased recruitment and closed the survey on August 24th 2020. Although it is not possible to know with certainty which methods yielded the majority of the responses, we did observe noticeable increases in responses that coincided with the paid Facebook advertisements and the Anglers Atlas emails (see Fig. 2 ). As such, the snowball-style recruitment had multiple points of origin (i.e., a large number of snowballs were seeded), which improves the chances of reaching diverse subpopulations compared to single-seeded samples (Kirchherr and Charles, 2018). Our target was ∼1000 anglers which we exceeded which is consistent with other studies that have used social media for recruitment (Stokes et al., 2019).

Fig. 2.

Visualization of survey initiation associated with different recruitment strategies.

Even in random sample surveys, voluntary participation can lead to self-selection bias, and the demographic diversity of social media users is an additional advantage of our approach (Kosinski et al., 2015). Facebook, one of the primary means in which we accessed participants, has long been used as a means for snowball sampling especially when posts are made in groups where there are members with common interests (see Baltar and Brunet, 2012; Brickman Bhutta, 2012). Use of paid advertisements is somewhat newer and allows for more targeted sampling (see Forgasz et al., 2018; Bennetts et al., 2019). We also relied heavily on emails to members of the Anglers Atlas. Anglers Atlas is associated with a phone-based app where anglers are able to log their fishing experiences. Their members receive regular correspondence so inclusion of a link to our survey was an effective way to reach Ontario users. Anglers Atlas has been previously used to survey anglers in British Columbia regarding their pro-environmental behaviours (see Jeanson et al., 2021). Overall, our choice of angler-oriented Facebook groups and outlets shows that our sampling considered how the target population uses social media (Topolovec-Vranic and Natarajan, 2016).

Survey questions addressed changes in recreational fishing effort, years of experience with angling, fishing-related travel and spending, retention and consumption of caught fish, quality of fishing during the pandemic, and the roles and responses of both government and recreational anglers in recreational fisheries during the pandemic (see Supplemental Material). The survey consisted of 41 questions (14 demographic), the majority of which were closed-ended and sought numeric estimates (e.g., number of days fished, percentage of fish harvested, amount of money spent on recreational angling, number of fish caught), as well as Likert-style questions involving the reasons and motivations behind behaviours and/or behavioural changes (e.g., for increasing or decreasing fishing effort, for consuming fish during the pandemic). Respondents were provided with open-ended ‘other’ options when applicable. Additional open-ended questions about governments and anglers, and their respective roles in ensuring safe and responsible recreational fishery use during the pandemic, were also included. All questions were optional, and filtering questions allowed respondents to skip parts of the survey that did not apply to them. Skipped questions and/or non-responses were not counted as incomplete, and all respondents who reached or exceeded the 90 % completion point were included in our sample and analyses.

Survey data provided insight on three distinct themes: (1) the general patterns in recreational fisheries during the pandemic (i.e., total days fished, number of fish caught, percentage of fish kept and [or] consumed, fishing-related spending), (2) participant motivations and/or reasons for change (i.e., for increased or decreased effort, increased or decreased consumption of fish), and (3) the communications and response(s) of governments and recreational anglers to the pandemic. Methods and findings for each respective theme are organized under distinct subheadings in subsequent sections (See Supplemental Material).

Survey questions were generated and refined over a period of approximately one month by a team of professors and graduate students from Carleton University and the University of Ottawa, as well as collaborating fisheries researchers from other institutions. The survey was tested by ten members of the Fish Ecology and Conservation Physiology Laboratory (FECPL), prior to its official launch on August 4th, 2020. A research ethics application was completed and submitted to the Carleton University Research Ethics Board B (CUREB-B), and the project was granted ethical clearance on July 22nd (Project #113,204). The survey was administered using the Qualtrics online survey platform. Survey submissions were removed from analysis if they were <90 % complete, and/or if respondents did not identify as Ontario residents who had previously fished recreationally in Ontario. This was done to eliminate any non-serious or mostly incomplete submissions.

2.1. General patterns

We obtained paired samples for the main hypothesized impacts on recreational fisheries during the pandemic (i.e., changes in angler effort, fish consumption, fishing-related spending, quality of fishing) in questions that sought estimates (e.g., of total days fished) across four distinct periods: Pandemic Phase 1, Pandemic Phase 2, and the same time periods in 2019. We performed Wilcoxon signed-rank tests in SPSS Version 26 to compare sample means and identify potential pandemic-related changes. Because a notable portion of survey respondents (∼21 %) self-identified as new entrants (i.e., individuals who began fishing, or resumed fishing after a hiatus of at least one year, between March 17th and July 15th, 2020), some tests were repeated separately for regular anglers and new entrants.

2.2. Reasons and motivations

Opinion statements regarding angler motivations (e.g., to fish more or less) during the pandemic were sought in closed-ended questions, wherein respondents were asked to indicate their level of agreement with various items using a five-point Likert scale (i.e., strongly disagree, somewhat disagree, neither agree nor disagree, somewhat agree, strongly agree). Likert data were analyzed using a factor analysis with varimax rotation as in Forina et al. (1989) in SPSS Version 25, in order to identify the important components of motivators.

2.3. Communications and response

Likert data on the pandemic response and quality of communications between governments and anglers were imported and organized in NVivo 12 (QSR International, 1999). Angler suggestions and perspectives on the role(s) of government in managing recreational fisheries during the pandemic were qualitatively analyzed with inductive thematic coding, as in Thomas (2006). Codes were created by identifying recurring themes in a subsample of survey responses, and then added inductively upon further reading. This process was repeated until a final list of codes was established, and then applied to the full list of responses. Descriptive statistics were obtained in SPSS Version 26, and a Kendall τb correlation coefficient was used to measure the association between respondent ratings of communication quality by Ontario’s Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry (MNRF), various municipal governments in Ontario, and the recreational angling community.

To analyze angler responses to questions about subsequent pandemic waves and emergent impacts of COVID-19 on recreational fisheries, a codebook was created deductively based on a preliminary overview of the data, as in Roberts et al. (2019). We used the values 1, 0, and 88 as proxies for agreement, disagreement, and uncertain agreement or disagreement with the predetermined codes. Additional codes were created inductively using the same process described in the previous paragraph (see Thomas, 2006). Respondent comments were described qualitatively for the most frequently agreed-upon codes.

3. Results

Of the 1620 surveys that were commenced, 811 were only partially completed, of which 32 were only opened. From the remaining 809 surveys, 789 were retained after eliminating submissions from respondents who did not identify as Ontario residents, or exceed 90 % completion. On average, respondents took 46 min to complete the survey, but this was probably a result of some respondents completing the survey intermittently over a much longer period of time, as the median completion time was ∼16 min, and the most common completion time was ∼10 min.

3.1. Socio-demographics

Most respondents to our survey identified as male (90.7 %, n = 706), with the remaining respondents identifying as female (8.5 %, n = 66) or other (0.8 %, n = 6). The mean age of respondents was 51, with a range of 12–81. The only fisheries management zone (FMZ) that was not selected as a common fishing region by respondents was Zone 1, in the province’s far north. Other northern FMZs (e.g., 2, 3, 4, 5, 7, 9) were identified in <10 responses. FMZ 15 in southcentral Ontario (n = 134), 16 in southwestern Ontario (n = 136), and 18 in eastern Ontario (n = 143) were selected most commonly by respondents as primary fishing regions. Respondent levels of education ranged from “Some high school” (n = 36), to “High school diploma” (n = 135), to “College diploma” (n = 284), “Undergraduate degree” (n = 180), and “Post-graduate degree” (n = 141). Annual household income (CAD) among respondents varied, but was skewed toward the high end of our income categories (<20 K, n = 18; 20–40 K, n = 72; 40–60 K, n = 87; 60–80 K, n = 111; 80–100 K, n = 113; >100 K, n = 308). When asked about fishing-related income, approximately 95 % of respondents reported earning their income from sources unrelated to fishing (n = 741 of 782), and the remaining 5% of respondents whose income was earned partially or fully from recreational fishing identified as members of angling media, guides, tourism professionals or outfitters, tackle and gear salespeople, and sponsored professional anglers. Approximately 90 % of respondents were born in Canada (n = 692 of 768), and the remaining 10 % identified the United States (US), China, and countries in the United Kingdom, for example, as their birthplaces. Approximately 98 % of respondents identified as Canadian citizens (n = 763 of 779), with approximately 2% self-identifying as permanent residents, and only one respondent identifying as a temporary resident.

3.1.1. Centrality to lifestyle and fishing experience

When asked about their skill level, approximately 50 % of all respondents reported having intermediate angling expertise (n = 387 of 778), with approximately 45 % self-identifying as advanced or expert anglers (n = 349), and approximately 5% identifying as novice anglers (n = 42). When asked about their agreement with the statement “fishing is an important part of my life” approximately 92 % of all respondents either agreed strongly (n = 458 of 780) or agreed (n = 256), with approximately 1% disagreeing with the statement and 7% responding neutrally (n = 57). Approximately 64 % of respondents were not members of fishing clubs and/or organizations (n = 491 of 767), whereas approximately 36 % (n = 276) reported belonging to a variety of provincial organizations (e.g., Ontario Federation of Anglers and Hunters [OFAH], Ontario Women Anglers, Ontario Fishing Club), regional organizations (e.g., North Bay Fishing Club, Hamilton Area Fly Fishers and Tyers, Bluewater Fishing Club), and species-specific groups (e.g., Muskies Canada, Bass Anglers Sportsman Society, Ontario Steelheaders).

3.2. General patterns

3.2.1. Angling effort

When asked directly about their participation in recreational fishing during the pandemic, approximately 19 % of respondents (n = 148 of 785) reported not fishing at all during Pandemic Phase 1 and Pandemic Phase 2 (see Table 1 ). Approximately 81 % of respondents reported fishing at some point during Phase 1 and/or Phase 2, and four respondents provided no answer. Approximately 7% of respondents (n = 46 of 635) reported not fishing at all between March 17th and July 15th in both 2019 and 2020, while approximately 93 % did fish during the aforementioned time period in both years. The remaining 154 survey respondents provided no answer. Approximately 50 % of all respondents (n = 390 of 781) reported fishing less than normal during Phase 1 and Phase 2, while the other 50 % stated that they did not fish less at any point during or as a result of the pandemic. Perhaps most notably, approximately 21 % of all survey respondents (n = 166 of 789) reportedly began fishing, or resumed fishing after a hiatus of at least one year, at some point during Phase 1 or Phase 2 (Table 1).

Table 1.

Summary of reported changes in fishing effort by respondents during Pandemic Phase 1 (i.e., March 17th to May 16th, 2020) and Pandemic Phase 2 (i.e., May 16th to July 15th, 2020).

| Pandemic Phase 1 |

Pandemic Phase 2 |

Both Phases |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | n (336) | % | n (571) | % | n (343) | |

| I returned or began fishing again after a one-year hiatus (break from fishing) during this period | 4.5 | 15 | 21.7 | 124 | 7.9 | 27 |

| I continued to fish as usual during this period | 10.1 | 34 | 33.6 | 192 | 46.4 | 159 |

| I have increased my fishing effort during this period | 6.9 | 23 | 31.4 | 179 | 20.1 | 69 |

| I have decreased my fishing effort during this period | 29.5 | 99 | 11.9 | 68 | 24.2 | 83 |

| I did not fish during this period | 49.1 | 165 | 1.4 | 8 | 1.5 | 5 |

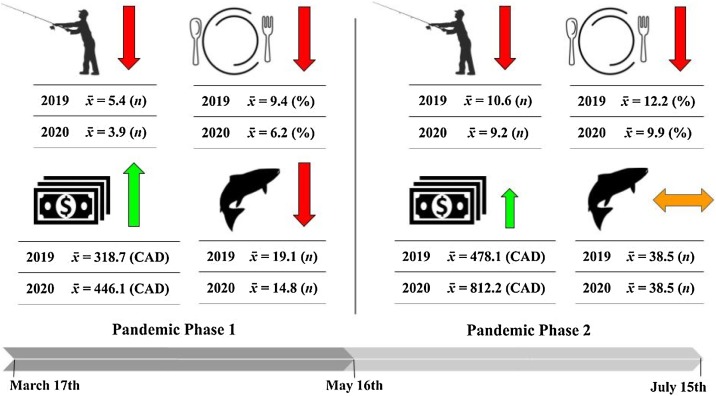

Wilcoxon signed-rank tests comparing the estimated total days fished by respondents during Pandemic Phase 1 and Pandemic Phase 2 to the previous year revealed a significant decrease during Phase 1 (n = 749, x̄ = 3.90, SD = 8.01) compared to the same period in 2019 (n = 754, x̄ = 5.37, SD = 8.00; z = –7.28, p < 0.001), and a significant decrease during Phase 2 (n = 705, x̄ = 9.17, SD = 10.89) compared to 2019 (n = 703, x̄ = 10.64, SD = 9.85; z = –5.16, p < 0.001). After excluding new entrants, tests comparing the estimated days fished by regular participants during Phase 1 and Phase 2 to the previous year revealed significant decreases during Phase 1 (n = 596, x̄ = 4.46, SD = 8.69) compared to the same period in 2019 (n = 597, x̄ = 5.87, SD = 8.48; z = –6.00, p < 0.001), and during Phase 2 (n = 562, x̄ = 9.23, SD = 10.75) compared to 2019 (n = 559, x̄ = 10.98, SD = 10.12; z = –4.90, p < 0.001).

3.2.2. Fishing-related travel

In our survey, fishing-related travel was defined as respondents travelling specifically to go fishing (e.g., short trips to local fishing spots, day trips, overnight trips). When asked directly about fishing-related travel during Phase 1, approximately 40 % of all survey respondents (n = 83 of 789) reported travelling far less compared to the previous year. However, when asked about fishing-related travel in Phase 2, approximately 45 % of all respondents reported either much more, or somewhat more fishing-related travel compared to the same period in 2019. Approximately 30 % reported about the same amount of fishing-related travel during Phase 2 as in the previous year. When asked about fishing-related travel in both periods, approximately 42 % of all survey respondents reported “About the same” amount of fishing related travel during both Phase 1 and Phase 2, compared to 2019, and an additional 26 %, reported “Much less” fishing-related travel, compared to the previous year (Table 2 ).

Table 2.

Reported changes in fishing-related travel by survey respondents during Pandemic Phase 1 (i.e., March 17th to May 16th, 2020) and Pandemic Phase 2 (i.e., May 16th to July 15th, 2020), and the same periods in 2019.

| Pandemic Phase 1 |

Pandemic Phase 2 |

Both Phases |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | n (207) | % | n (353) | % | n (263) | |

| Much more than 2019 | 14.5 | 30 | 24.4 | 86 | 10.7 | 28 |

| Somewhat more than 2019 | 11.1 | 23 | 21.0 | 74 | 8.8 | 23 |

| About the same as 2019 | 16.9 | 35 | 29.8 | 105 | 42.2 | 111 |

| Somewhat less than 2019 | 17.4 | 36 | 15.9 | 56 | 12.6 | 33 |

| Much less than 2019 | 40.1 | 83 | 9.1 | 32 | 25.9 | 68 |

3.2.3. Fish consumption

When asked about their retention and/or consumption of fish during Phase 1 and Phase 2 (i.e., March 17th to July 15th, 2020), approximately 57 % of all respondents (n = 361 of 638) reported keeping and/or consuming fish at some point, while approximately 47 % reported not keeping and/or consuming any caught fish. The remaining survey respondents provided no answer. Wilcoxon signed-rank tests comparing estimated percentages of caught fish that were kept and/or consumed during Phase 1 and Phase 2 to the previous year revealed a significant decrease during Phase 1 (n = 739, x̄ = 6.20, SD = 20.04) compared to the same period in 2019 (n = 744, x̄ = 9.42, SD = 26.02; z = –4.66, p < 0.001), and a significant decrease during Phase 2 (n = 698, x̄ = 9.94, SD = 22.97) compared to the same period in 2019 (n = 698, x̄ = 12.22, SD = 23.96; z = –4.83, p < 0.001). Tests were repeated with new entrant responses excluded, but results consistently pointed to a significant decrease in the estimated percentage of caught fish that anglers kept and/or consumed during the pandemic.

3.2.4. Fishing-related spending

Wilcoxon signed-rank tests comparing estimates of fishing-related spending during Phase 1 and Phase 2 to the previous year revealed a significant increase during Phase 1 (n = 739, x̄ = 446.05, SD = 2526.16) from the same period in 2019 (n = 746, x̄ = 318.68, SD = 1545.02; z = –3.28, p = 0.001), and an increase during Phase 2 (n = 698, x̄ = 812.18, SD = 5221.14) from the same period in 2019 (n = 694, x̄ = 478.08, SD = 1788.01) that was not statistically significant (z = –1.10, p = 0.27). With new entrants excluded, there was also a significant increase in fishing-related spending by regular anglers during Phase 1 (n = 588, x̄ = 488.79, SD = 2744.42) compared to 2019 (n = 594, x̄ = 324.64, SD = 1393.62; z = –2.65, p = 0.008). Although fishing-related spending by new entrants increased by more than $900.00 CAD in Phase 2, the result was not statistically significant. Respondents were asked about the likelihood of them making typical fishing-related purchases during Phase 1 and Phase 2 using a three-point Likert scale. Descriptive statistics for responses to the likeliness-to-pay question are presented in Table 3 . In Phase 1 and Phase 2, respondents were least likely to make online purchases at US-based big box stores. In Phase 2, respondents were reportedly more likely to buy fishing gear and tackle, particularly from local specialty stores.

Table 3.

Likeliness to pay responses (1 = Likely, 2 = Neither likely nor unlikely, 3 = unlikely).

| Pandemic Phase 1 |

Pandemic Phase 2 |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | x̄ | SD | n | x̄ | SD | |

| Fishing licenses/outdoor cards | 439 | 1.86 | 0.64 | 346 | 1.82 | 0.63 |

| Fishing license/outdoor card renewals | 440 | 1.83 | 0.65 | 346 | 1.82 | 0.64 |

| Fishing gear and tackle | 452 | 1.83 | 0.76 | 354 | 1.66 | 0.68 |

| Fishing-related travel | 434 | 2.15 | 0.77 | 354 | 1.96 | 0.77 |

| Boating-related expenses (e.g., launch fees, fuel) | 432 | 2.03 | 0.77 | 350 | 1.85 | 0.76 |

| Online big box store purchases (Canada-based) | 432 | 1.97 | 0.76 | 349 | 1.91 | 0.76 |

| Online big box store purchases (US-based) | 414 | 2.31 | 0.7 | 341 | 2.27 | 0.73 |

| Local specialty store purchases (e.g., tackle/fly shops) | 436 | 1.89 | 0.76 | 347 | 1.73 | 0.73 |

| Local online store purchases | 425 | 1.97 | 0.76 | 345 | 1.95 | 0.75 |

3.2.5. Quality of fishing

A Wilcoxon signed-rank test comparing the estimated number of fish caught by respondents during Phase 1 to the previous year revealed a significant decrease during Phase 1 (n = 728, x̄ = 14.85, SD = 70.31) from the same period in 2019 (n = 729, x̄ = 19.12, SD = 47.83; z = –7.24, p < 0.001). Comparing the estimated number of fish caught by respondents during Phase 2 (n = 692, x̄ = 38.45, SD = 112.83) to the same period in 2019 (n = 688, x̄ = 38.51, SD = 67.03) also revealed a significant decrease (z = –3.90, p < 0.001), but the difference was very small. With new entrants excluded, the estimated number of fish caught by regular anglers increased significantly in Phase 2 (n = 550, x̄ = 40.94, SD = 121.95) compared to 2019 (n = 549, x̄ = 40.10, SD = 70.69; z = –3.35, p = 0.001), although the difference was once again very small.

Mean changes in estimated days fished, percentage of caught fish consumed, fishing-related spending, and number of fish caught by all respondents during the study period are summarized in Fig. 3 .

Fig. 3.

Mean changes in estimated days fished (top right), percentage of caught fish consumed (top left), fishing-related spending (bottom left), and number of fish caught (bottom right) by all respondents during Phase 1 and Phase 2, compared to the previous year. Small arrows represent statistically insignificant changes.

3.3. Reasons and motivations

3.3.1. Increases in effort

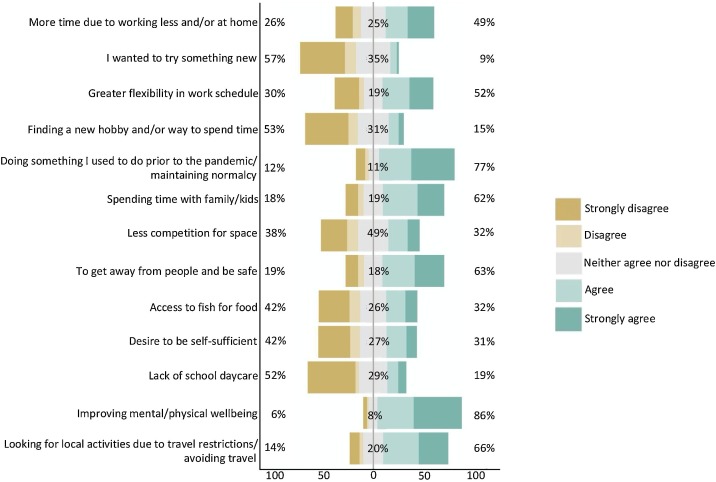

Three components of angler motivations to begin, resume, or continue fishing during the pandemic (n = 208) were identified (Fig. 4 ). Together, the three distinct constructs explain 58 % of the variance, and Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity indicates p < 0.001. Component 1 was related to what respondents perceived as an opportunity or desire to engage in a hobby, whereas Component 2 items were general motivations to maintaining physical and mental wellbeing in a relatively safe manner. Component 3 items were related to a desire for self-sufficiency by means of fish harvest.

Fig. 4.

Motivations to fish during the pandemic as indicated by agreement with Likert-style response options.

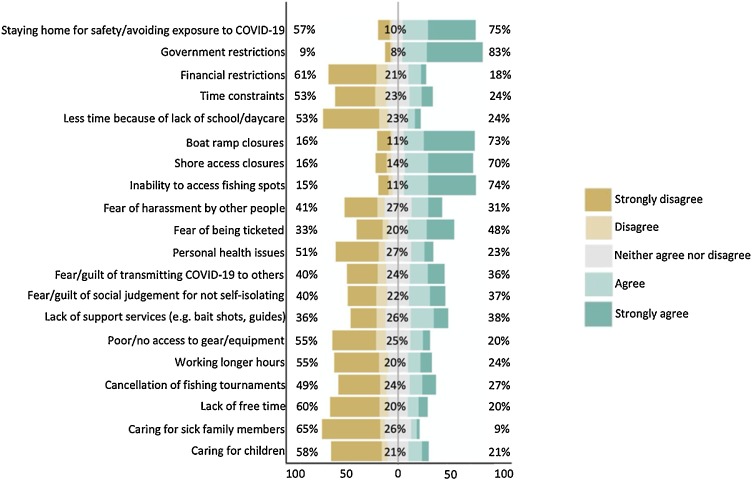

3.3.2. Reductions in effort

Four motivators for anglers to fish less at any point during the pandemic (n = 157) were identified. Collectively, these constructs explain 66 % of the variance, and Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity indicates p < 0.001. The following four components were identified: (1) lack of free time (e.g., due to work, familial obligations); (2) inability to access fishing spots and fear of being ticketed; (3) lack of support services; and (4) fear and/or anticipated guilt of transmitting COVID-19, or being socially judged for not self-isolating. Motivations to fish less during the pandemic are visualized in Fig. 5 .

Fig. 5.

Motivations to fish during the pandemic as indicated by agreement with Likert-style response options.

3.3.3. Consumption of fish

Two motivators for anglers to keep and/or consume fish at any point during Phase 1 and Phase 2 (n = 214) were identified. The two constructs explain 66 % of the variance, and Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity indicates p < 0.001. Component 1 was related to new opportunities as a result of reduced fishing pressure, and Component 2 items were general motivators for maintaining normalcy and safe self-sufficiency.

3.4. Communications and response

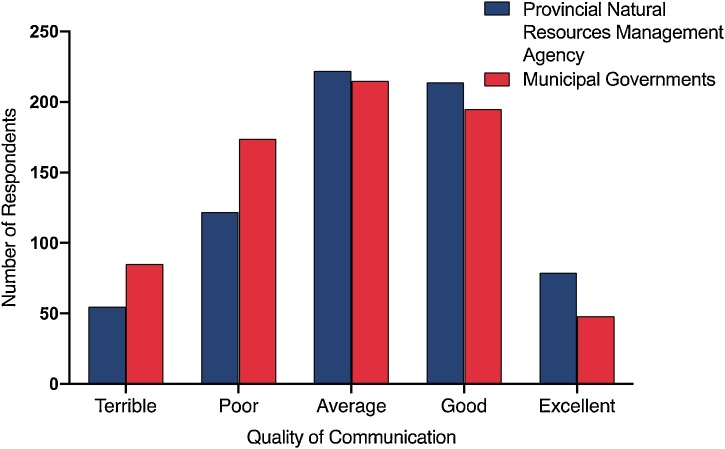

3.4.1. Communications between anglers and governments

When asked to rate the quality of communications between the MNRF (n = 781) and municipal governments, and anglers (n = 778), the majority of respondents rated MNRF (∼55 %) and municipal government (∼52 %) communication with anglers as average or good, while a minority of respondents rated MNRF (∼15 %) and municipal government (∼22 %) communications as poor. Ratings of MNRF and municipal government communication were moderately associated (τb = 0.341, p = <0.001; Fig. 6 ). When prompted, respondents who expressed dissatisfaction were more likely to contribute suggestions.

Fig. 6.

Respondent ratings of communications quality for the Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry (i.e., the provincial natural resources management agency) and Ontario municipal governments in relation to recreational fisheries and angling during the pandemic. Additional respondents selected “I Don’t Know” in regard to MNRF (n = 89) and municipal government communications (n = 61).

3.4.2. Angler perspectives

Many respondents suggested ways to improve communications between the MNRF and anglers (n = 171), and between municipal governments and anglers (n = 179). Many of these suggestions were related to the belief that access to public boat launches, parking, and shoreline fishing spots should not have been restricted during the pandemic, although other respondents acknowledged the necessity of such measures despite their dissatisfaction. Angler views on enforcement varied notably; some survey respondents felt that rules and enforcement were unnecessarily prohibitive toward fishing, whereas other respondents viewed the same measures as appropriate. Fishing was viewed by some respondents as a relatively safe pandemic activity due to its conduciveness to social distancing (3% of all comments). Additional comments touched on food security (1%), and many respondents testified to the benefits of fishing and outdoor recreation for their mental health (3%). Some respondents felt that institutions were not adequately prepared to manage crises due to a lack of funding and capacity. The perceived need for more funding in fisheries conservation appeared partially attributable to more people discovering and rediscovering fishing during the pandemic. Approximately 4% of all respondents expressed a desire for governments to take a more active role in ensuring safe use of fisheries during the pandemic.

3.4.3. Suggestions for communication

Respondent suggestions highlighted a common desire for greater clarity and communication by the MNRF and Ontario municipal governments in relation to (1) legal and/or permissible pandemic activities, (2) facility accessibility, and (3) special closures. Regarding their confusion about restrictions and the rationale(s) for closures, respondents cited mixed messaging, a general lack of communication, and a lack of information in intermittent or rare communications as causes for uncertainty. Respondents who provided additional input suggested that government communication be clear across different regions, proactive in nature, and updated in a timely manner.

In response to such uncertainty, some respondents reportedly obtained information from OFAH, confirming the strengths of such organizations in mediating and communication roles. The OFAH maintained a website with details on fishing closures across the province (see https://www.ofah.org/covid19closures/) and also provided anglers with guidance for how to fish safely during the pandemic (https://www.ofah.org/safetytips/). Respondents also alluded to the possibility of municipalities and the MNRF using social media to provide updates and counteract misinformation, or devoting specific websites and/or web pages to detailing access point closures. Among other things, respondents noted that the use of lay language would be important to maximize and ensure accessibility. Additional respondents suggested that the MNRF send information by email to all license holders. Respondents found local signage that was posted by municipalities to be particularly useful, and expressed their desire to see more, noting that this varied significantly across jurisdictions.

3.4.4. Preparing for future waves

Participants were asked directly about their conceptions of the MNRF’s role in ensuring safety, sustainability, and accessibility in Ontario’s recreational fisheries during the COVID-19 pandemic, and response to potential long-term effects. Only 2% of all respondents believed that the pandemic would have no long-term impact(s) on Ontario’s fisheries. Approximately 4% believed that the MNRF should play a greater role in protecting public health, and approximately 6% felt that the MNRF should play a greater role in ensuring fishery accessibility. Approximately 39 % of the respondents who offered suggestions believed that the MNRF should modify management practices in order to protect fisheries in response to any threats (e.g., increased exploitation) that emerged or were exacerbated by the pandemic. Respondents also offered suggestions that were loosely related to the pandemic, and more closely related to fisheries management in general: according to respondents, the MNRF should increase enforcement and monitoring efforts, stocking, bag limits and restrictions, and angler education (e.g., about responsible catch-and-release practices for new anglers). Approximately 11 % of respondent anglers felt that the MNRF’s ongoing efforts were effective, and should not be modified.

Approximately 40 % of all respondents believed that the pandemic presented opportunities for fishing and conservation in Ontario. However, 8% believed that the pandemic would ease pressure on fisheries, and 16 % felt that the pandemic would cause increases in both the number of anglers and cumulative fishing pressure. Only 2% of respondents felt that the pandemic would create economic opportunities (e.g., due to increases in local tourism, fishing-related purchases, license sales). Approximately 9% of respondents believed that the pandemic presented opportunities to educate new and existing anglers on sustainable practices such as catch and release, and approximately 5% felt that the pandemic would create more support for the protection of natural resources. Some of the approximately 18 % of respondents who believed that the pandemic did not present any opportunities for recreational fisheries argued that more restrictions were necessary, and that ongoing conservation efforts were disrupted by the pandemic.

Finally, respondents were asked how anglers and governments should respond to a second wave of COVID-19, to which approximately 57 % responded that governments should either continue to allow fishing with procedures and restrictions similar to those used during the first wave, or return to ‘business as usual.’ Some of these respondents suggested the following actions during the anticipated second wave: (1) education on best fishing practices, etiquette, catch and release, and pandemic health and safety precautions (∼2%); (2) enforcement of social distancing and fishing limits (∼6%); and (3) better communication of restrictions (∼10 %). Only 12 % of respondents believed that governments should shut down or further restrict fisheries (e.g., by limiting access to local residents and/or modifying bag limits). Approximately 48 % of all respondents believed that anglers should continue fishing and follow public health guidelines during a second wave, and 3% felt that anglers should only fish locally (Table 4 ).

Table 4.

Percentages of angler responses to the second wave of the COVID-19 pandemic. Percentages do not add to 100, as some respondents provided no answer, and some responses were coded in multiple categories.

| Response category | Respondent suggestions (%) |

|---|---|

| Stay home and forego fishing | 7.0 |

| Only fish locally | 3.3 |

| Fish with precautions for COVID-19 | 48.0 |

| Sustainable fishing practices | 5.1 |

| Continue fishing as usual | 9.8 |

| Fish more | 1.4 |

4. Synthesis

4.1. Survey limitations

The federal government’s 2015 Canadian Recreational Fishing Survey is statistically robust (i.e., it uses license databases, stratified random sampling according to license category and region, and is administered by mail), contains province-specific information, and provides insight on the demographic consistency of our sample with the population of resident anglers in Ontario. According to Fisheries and Oceans Canada (DFO), 77 % of Ontario anglers are male, and 23 % are female. Women were comparatively underrepresented in our survey, at 8.5 %. The average age of anglers in our survey was 51 years, which is two years older than the average male angler in Ontario, and five years older than the average female angler, according to DFO’s survey. DFO does not ask questions about the centrality of recreational fishing to respondent lifestyles, and our survey lacks a comparator in this regard. We also note that some of our results align with previous findings about angling communities (e.g., section 4.3). However, because >91 % of respondents indicated that they strongly agreed or agreed with the statement “fishing is an important part of my life,” our study was likely subject to an avidity bias. This hypothesis is supported even further by the high levels of participation and membership in fishing clubs and organizations in our respondent group, and most respondents self-identifying as anglers with intermediate or advanced expertise. This type of avidity bias is not specific to our sampling method and is likely in both online and telephone surveys (Szolnoki and Hoffmann, 2013). Participation in the online survey was also voluntary. Although we did ask questions about fishing effort, harvest, catch rates, and fishing-related expenditures, responses were limited to periods of interest (i.e., Pandemic Phase 1 and Pandemic Phase 2) rather than full seasons or years. We relied heavily on social media for distribution (e.g., Facebook groups, targeted advertising) which requires individuals to sign up and join fishing groups, and/or identify fishing as one of their hobbies.

Despite previously mentioned biases, a high number of new entrants (∼21 %) responded to our survey, indicating that it did reach beyond the regular angling community. Although we do not yet have access to any formal numbers about fishing license sales in 2020, recent news items report that overall license sales for 2020 were up 20 % in Ontario (see https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/edmonton/fishing-alberta-pandemic-1.5726943) which aligns with the percentage of new entrants observed in our study. Some questions required anglers to recall activities and expenditures from approximately one year prior, and it is possible that our results were affected by recall bias (Tarrant et al., 1993). However, recall bias tends toward overestimation of things like angling effort and catches (Connelly and Brown, 1995, 2011), which may explain the relatively small effect sizes that were observed in comparisons of fishing and related activities between Phase 1 and Phase 2, and the previous year. Limitations considered, we suggest that other researchers exercise—as we do here—appropriate caution when considering the broader implications of our results (e.g., in the greater angling community). Our results serve more appropriately as an exploratory snapshot of the pandemic’s effect(s) on a subset of recreational anglers in Ontario, Canada.

We acknowledge the limitations of online snowball-style surveys (Johnson, 2005; Baltar and Brunet, 2012), but do not attempt to make inferences or extrapolations beyond our respondent group. We are aware of several government-led, state or province-wide surveys elsewhere in North America that use license databases and other strategies (e.g., angler apps) to obtain more statistically robust samples and perform in-depth analysis. The research reported here is timely and exploratory, and aims to identify a range of perspectives, experiences, and behaviours that may exist within a broader population, as opposed to precisely measuring their prevalence or interactions. The analysis that we present cannot be generalized, but is valuable for those studying or managing Ontario fisheries including fisheries managers, the fishing industry, fishing organizations (e.g., clubs, advocacy groups), and resource management agencies who are concerned with threats and opportunities that have arisen due to COVID-19.

4.2. General trends

Mean estimated fishing effort for regular anglers and new entrants decreased during Phase 1 and Phase 2 compared to the same periods in 2019. Although results were statistically significant, mean decreases were small (i.e., 1–2 days less over 60 days). In general, the effects of the pandemic and corresponding restrictions on fishing appeared minimal. Approximately 21 % of survey respondents (n = 166 of 789) self-identified as new entrants who began or resumed fishing (after a hiatus of at least one year) during Phase 1 and/or Phase 2. This result appears supportive of the notion that recreational fishing is relatively unaffected by pandemic conditions compared to other leisure activities, and also speaks to the benefits of recreational fishing for participants’ physical and mental well-being.

Estimates of fishing-related travel decreased significantly during Phase 1, compared to the same period in 2019. Conversely, during Phase 2, fishing-related travel increased significantly relative to the previous year. Two potential explanations for this increase are (1) lack of access to local fishing spots (e.g., due to municipal bylaws, park closures), and (2) increased free time and/or flexibility during the pandemic lockdown. Across the entire study period, fishing-related travel appeared relatively unaffected by pandemic conditions, with the exception of some anglers who elected to abstain from non-local fishing, or travelled far less than in previous years. As with angling effort, notable percentages of respondents reported increasing or decreasing their fishing-related travel drastically during Phase 1 and/or Phase 2. Participation disparities in recreational fishing and other recreational activities have been attributed to physical disabilities and inequality in previous research (Freudenberg and Arlinghaus, 2009; Sotiriadou and Wicker, 2014), and some polarities in recreational fishing and related activity during the pandemic may be explained by differences in perceived vulnerability and risk (e.g., due to age, pre-existing medical conditions) across different participants and groups. This notion is also supported by motivational components related to lacking support services.

Mean estimated percentages of caught fish that were kept and/or consumed by respondents decreased significantly in Phase 1 and Phase 2, compared to the same periods in 2019. Prior to conducting the study, our team had considered that fears of food and nutritional insecurity could be reflected in more consumptive recreational angling behaviours, as has been observed in some subsistence fisheries (see Pinder et al., 2020). This result may be partially attributable to changes in angling effort and culture, such as the growing emphasis on catch and release, angler and fishery heterogeneity (Nguyen et al., 2013), pursuit of different species, and/or catching fewer legally harvestable fish. Statistical interpretation and testing revealed significant increases in fishing-related spending by all respondents during Phase 1, and by regular anglers during Phase 1. Early pandemic boredom and increased screen time may partially explain this. Respondents also showed a preference toward Canadian stores, and in particular local specialty shops, while seemingly avoiding US-based big box stores. Although fishing-related spending by new entrants increased by more than $900.00 CAD in Phase 2, the result was not statistically significant.

Catch rates appeared to decline significantly in Phase 1 compared to the previous year. Although statistical tests revealed significant differences between the mean estimated number of fish caught by all respondents, as well as regular anglers during Phase 2, these changes were very small (i.e., less than one fish per angler). Based on this, it seems that reductions in angling effort during Phase 1 may have led to a decline in overall catch rates for that period, before returning to the previous year’s average in Phase 2. It is possible that a drastic increase in angling effort by some individuals in Phase 2 compensated for a drastic reduction in angling effort by others. Given the presumed avidity bias with our nonrandom sample, it is entirely possible that our findings are more reflective of the most avid anglers, rather than the “average angler.”

4.3. Reasons and motivations

Some anglers elected to fish more than usual during Phase 1 and Phase 2, while others did the opposite, and our analysis of estimated days fished revealed small, yet notable differences in recreational fishing effort between the study period and the same dates in 2019. Anglers who increased their effort cited opportunities to engage in a new or preferred hobby, benefits to mental and physical well-being, and desires for self-sufficiency as important motivations. These findings are consistent with prior research on the importance of recreational fishing for participants’ mental and physical health (McManus et al., 2011; Griffiths et al., 2016), as well as the contribution of recreational fishing to food and nutritional security (Cooke et al., 2017).

Respondents who fished less during Phase 1 and Phase 2 did so due to lack of free time (e.g., due to work, familial obligations), a lack of access to fishing spots and/or fear of being ticketed, insufficient support services, and fear or guilt associated with contracting or transmitting the virus or failing to comply with and uphold social distancing norms. These results suggest that the different individual angler responses resulted from differences in perceived risk (e.g., due to age, pre-existing conditions, proximity to high-risk individuals) and familial obligations. Individuals with a lower perceived risk and fewer constraints appeared more likely to fish for reasons related to mental and physical well-being. Disparities in recreational fishing and related activity during the pandemic appear attributable, in part, to the balance of costs (e.g., health risks, social stigma) and benefits (e.g., improved mental and physical health) perceived by each individual.

4.4. Communications and response

The COVID-19 pandemic reinforces calls for improved environmental governance and resilience building in preparation for crises in socio-ecological systems such as recreational fisheries (Berkes, 2017). Although most Ontario anglers were satisfied with government communications, our survey highlights gaps and opportunities for improvement. It is worth noting that angling communities are heterogenous (Arlinghaus, 2007), and that Ontario anglers have diverse views on closures and other pandemic-related public health recommendations. In response to angler dissatisfaction, governments may improve their communication strategies by making information more consistently available and accessible (e.g., by using online resources; Hyland-Wood et al., 2021). Coordinating messages and communication across geographical and institutional boundaries, building and utilizing relationships with influential groups, centralizing information management, communicating with the public in a clear and transparent way, and creating mechanisms for public input and engagement may aid in this endeavour (see Kim and Kreps, 2020). In addition to transparency, science and/or evidence-based rationales may increase angler compliance and support for restrictions.

The pandemic also highlights the importance of non-governmental organizations (NGOs) like OFAH in information sharing. Communication and management could be improved through multilevel collaborations that nurture dialogue and increase coordination between community organizations and municipalities, and across levels of government (Armitage, 2008). This is crucial in a pandemic context wherein relevant issues extend beyond jurisdictional and political boundaries, and demonstrate the value of coordinated multilevel governance in complex crisis management (Ryan, 2020).

Inconsistent closures and pandemic responses across municipalities can ‘funnel’ anglers into adjacent “open” areas, creating what some researchers refer to as spillover effects (Andrés et al., 2012). This type of response has the potential to exacerbate crowding, which poses a risk to both public and fishery health. Consequences of this phenomenon may emerge and persist as long as mitigation strategies remain inconsistent (e.g., across municipalities), and may intensify if perceptions of crowding are met with further restrictions, creating a positive feedback loop. Improved coordination could help to minimize this spillover effect, and both researchers and managers should consider how drastic increases in free time and flexibility have affected the location and intensity of angling effort during the pandemic. Respondents also expressed their desires for the MNRF to take a more active role in pandemic mitigation, although many additional suggestions were related to pre-existing concerns (e.g., education, enforcement, stocking, monitoring, budget; Galea, 2019).

4.5. Conclusion

The COVID-19 pandemic sparked immediate changes in human behaviour, due largely to government-ordered ‘shelter-in-place’ restrictions, and other drivers such as health concerns, financial instability, psychological stress, and leisure time availability (Corlett et al., 2020). Restrictions that related specifically to outdoor recreation (Freeman and Eykelbosh, 2020; Rice et al., 2020) and recreational fishing (see Paradis et al., 2021) were also enacted, and played a role in this. Despite the inherent biases of online snowball surveying, our research yielded valuable insight on the diverse perspectives of anglers in relation to pandemic restrictions, and their impact(s) on recreational fisheries. Our findings suggest that survey respondents from Ontario’s recreational fisheries did alter their fishing-related behaviour(s), albeit not as drastically as we had anticipated. Particularly noteworthy, and consistent with reports from legacy media sources (e.g., McEwan, 2020; Thomas, 2020), was the fact that a significant minority of respondents (∼21 %) reportedly resumed or began fishing during the pandemic. Increases in fishing-related travel during the study period, increased fishing-related spending, and the influx of new participants in ours and other studies, point to the apparent resilience of recreational fishing to the Anthropause.

Subsequent pandemic waves are now occurring across the globe and are forecast to continue for much of 2021, even during mass vaccination. Given this, as well as the potential for future pandemics, our findings provide insight on effective communication, management, and mitigation strategies, as well as restrictions that regulators may find useful in future attempts to protect public health. Ensuring public safety is the ultimate responsibility of governments, and the diverse perspectives shared here may help to inform future decisions, as well as enhance communications between management authorities and the angling community. Among other things, this may help to improve compliance with imposed measures (Van Bavel et al., 2020). Early efforts to restrict outdoor recreation and reduce potential consequences did not benefit sufficiently from scientific information and stakeholder input, due largely to the need for swift action. However, expectations about consultation, the use of evidence (Kadykalo et al., 2021), and matters beyond public health (e.g., natural resource management, recreational fisheries) will change going forward. This snapshot may encourage fisheries managers to consider how the pandemic has influenced anglers in various regions, and provide a basis for more comprehensive angler surveys (e.g., using phone app data that may not contain recall bias, or statistically rigorous mail/phone surveys targeting anglers non-randomly) that explore central issues across different regions, and with more robust sampling and survey designs.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgements

We kindly thank the respondents for their participation in our survey. We also thank Sean Simmons at the Anglers Atlas, and the team at Ontario Out of Doors for assisting with dissemination of the survey instrument. Funding was provided by Carleton University and the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada via the CREATE FishCast project, and Genome Canada via the GenFish project. We also thank Steve Midway and an anonymous referee for commenting thoughtfully on our manuscript.

Handled by Steven X. Cadrin

Footnotes

Supplementary material related to this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fishres.2021.105961.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is Supplementary data to this article:

References

- Andrés S.M., Mir L.C., Bergh J.C., Ring I., Verburg P.H. Ineffective biodiversity policy due to five rebound effects. Ecosyst. Serv. 2012;1:101–110. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoser.2012.07.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Arlinghaus R. Voluntary catch‐and‐release can generate conflict within the recreational angling community: a qualitative case study of specialised carp, Cyprinus carpio, angling in Germany. Fish. Manag. Eco. 2007;14:161–171. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2400.2007.00537.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Arlinghaus R., Cooke S.J. In: Recreational Hunting, Conservation and Rural Livelihoods: Science and Practice. Dickson B., Hutton J., Adams W.M., editors. Blackwell Publishing Ltd; 2009. Recreational fisheries: socioeconomic importance, conservation issues and management challenges; pp. 39–58. [Google Scholar]

- Armitage D. Governance and the commons in a multi-level world. Int. J. Commons. 2008;2:7–32. doi: 10.18352/ijc.28. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bakar N.A., Rosbi S. Effect of Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) to tourism industry. Int. Adv. Res. J. Sci. Eng. Technol. 2020;7 doi: 10.22161/ijaers.74.23. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Baltar F., Brunet I. Social research 2.0: virtual snowball sampling method using Facebook. Internet J. Rescue Disaster Med. 2012;22:57–74. doi: 10.1108/10662241211199960. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bates A.E., Primack R.B., Moraga P., Duarte C.M. COVID-19 pandemic and associated lockdown as a “Global Human Confinement Experiment” to investigate biodiversity conservation. Biol. Conserv. 2020:108665. doi: 10.1016/j.biocon.2020.108665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennetts S.K., Hokke S., Crawford S., Hackworth N.J., Leach L.S., Nguyen C., Nicholson J.M., Cooklin A.R. Using Paid and Free Facebook Methods to Recruit Australian Parents to an Online Survey: An Evaluation. J. Med. Internet Res. 2019;21 doi: 10.2196/11206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berkes F. Environmental governance for the Anthropocene? Social-ecological systems, resilience, and collaborative learning. Sustainability. 2017;9:1232. doi: 10.3390/su9071232. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Billington J., Deschamps I., Erck S.C., Gerberding J.L., Hanon E., Ivol S., Shiver J.W., Spencer J.A., Van Hoof J. Developing vaccines for SARS-CoV-2 and future epidemics and pandemics: applying lessons from past outbreaks. Health Secur. 2020;18:241–249. doi: 10.1089/hs.2020.0043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brickman Bhutta C. Not by the book: facebook as a sampling frame. Sociol. Method Res. 2012;41:57–88. doi: 10.1177/0049124112440795. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brownscombe J.W., Bower S.D., Bowden W., Nowell L., Midwood J.D., Johnson N., Cooke S.J. Canadian recreational fisheries: 35 years of social, biological, and economic dynamics from a national survey. Fisheries. 2014;39:251–260. doi: 10.1080/03632415.2014.915811. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Buckley R. Conservation implications of COVID19: effects via tourism and extractive industries. Biol. Conserv. 2020;247 doi: 10.1016/j.biocon. 2020.108640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canada, Fisheries and Oceans . 2019. Survey of Recreational Fishing in Canada 2015.https://www.dfo-mpo.gc.ca/stats/rec/can/2015/index-eng.html Ottawa. [Google Scholar]

- Chakraborty I., Maity P. COVID-19 outbreak: migration, effects on society, global environment and prevention. Sci. Total Environ. 2020;728 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.138882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connelly N.A., Brown T.L. Use of angler diaries to examine biases associated with 12-month recall on mail questionnaires. Trans. Am. Fish. Soc. 1995;124:413–422. doi: 10.1577/1548–8659(1995)124<0413:UOADTE>2.3.CO;2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Connelly N.A., Brown T.L. Effect of recall period on annual freshwater fishing effort estimates in New York. Fish. Manag. Eco. 2011;18:83–87. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2400.2010.00777.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cooke S.J., Twardek W.M., Lennox R.J., Zolderdo A.J., Bower S.D., Gutowsky L.F., Danylchuk A.J., Arlinghaus R., Beard D. The nexus of fun and nutrition: recreational fishing is also about food. Fish Fish. 2017;19:201–224. doi: 10.1111/faf.12246. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cooke S.J., Twardek W.M., Lynch A.J., Cowx I.G., Olden J.D., Funge-Smith S., Lorenzen K., Arlinghaus R., Chen Y., Weyl O.L.F., Nyboer E.A., Pompeu P.S., Carlson S.M., Koehn J.D., Pinder A.C., Raghavan R., Phang S., Koning A.A., Taylor W.W., Bartley D., Britton J.R. A global perspective on the influence of the COVID-19 pandemic on freshwater fish biodiversity. Biol. Conserv. 2021;253 [Google Scholar]

- Corlett R.T., Primack R.B., Devictor V., Maas B., Goswami V.R., Bates A.E., Koh L.P., Regan T.J., Loyola R., Pakeman R.J. Impacts of the coronavirus pandemic on biodiversity conservation. Biol. Conserv. 2020;246 doi: 10.1016/j.biocon.2020.108571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diffenbaugh N.S., Field C.B., Appel E.A., Azevedo I.L., Baldocchi D.D., Burke M., Burney J.A., Ciais P., Davis S.J., Fiore A.M., Fletcher S.M., Hertel T.W., Horton D.E., Hsiang S.M., Jackson R.B., Jin X., Levi M., Lobell D.B., McKinley G.A., Moore F.C., Montgomery A., Nadeau K.C., Pataki D.E., Randerson J.T., Reichstein M., Schnell J.L., Seneviratne S.I., Singh D., Steiner A.L., Wong-Parodi The COVID-19 lockdowns: a window into the Earth System. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2020;1:470–481. doi: 10.1038/s43017-020-0079-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Duda M.D., Nobile J.L. The fallacy of online surveys: No data are better than bad data. Hum. Dimens. Wildl. 2010;15:55–64. doi: 10.1080/10871200903244250. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Forgasz H., Tan H., Leder G., McLeod A. Enhancing survey participation: facebook advertisements for recruitment in educational research. Int. J. Res. Method Educ. 2018;41:257–270. doi: 10.1080/1743727X.2017.1295939. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Forina M., Armanino C., Lanteri S., Leardi R. Methods of varimax rotation in factor analysis with applications in clinical and food chemistry. J. Chemom. 1989;3:115–125. doi: 10.1002/cem.1180030504. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman S., Eykelbosh A. 2020. COVID-19 and Outdoor Safety: Considerations for Use of Outdoor Recreational Spaces.https://ncceh.ca/documents/guide/covid-19-and-outdoor-safety-considerations-use-outdoor-recreational-spaces [Google Scholar]

- Freudenberg P., Arlinghaus R. Benefits and constraints of outdoor recreation for people with physical disabilities: inferences from recreational fishing. Leis. Sci. 2009;32:55–71. doi: 10.1080/01490400903430889. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Galea S. 2019. Provincial Budget Cuts Hit MNRF Hard.https://oodmag.com/provincial-budget-cuts-hit-mnrf-hard/ [Google Scholar]

- Government of Ontario . 2020. Fisheries in Ontario.https://www.ontario.ca/page/fisheries-ontario (accessed 16 November 2020) [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths S.P., Pollock K.H., Lyle J.M., Pepperell J.G., Tonks M.L., Sawynok W. Following the chain to elusive anglers. Fish Fish. 2010;11:220–228. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-2979.2010.00354.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths S.P., Bryant J., Raymond H.F., Newcombe P.A. Quantifying subjective human dimensions of recreational fishing: does good health come to those who bait? Fish Fish. 2016;18:171–184. doi: 10.1111/faf.12149. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hunt L.M., Sutton S.G., Arlinghaus R. Illustrating the critical role of human dimensions research for understanding and managing recreational fisheries within a social-ecological system framework. Fish. Manag. Ecol. 2013;20:111–124. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2400.2012.00870.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hyland-Wood B., Gardner J., Leask J., Ecker U.K.H. Toward effective government communication strategies in the era of COVID-19. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2021;8:1–11. doi: 10.1057/s41599-020-00701-w. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jeanson, A.L., Cooke, S.J., Danylchuck, A.J., Young, N. In Press. Drivers of pro-environmental behaviours among outdoor recreationists: The case of a recreational fishery in Western Canada. J. Environ. Manage. 00:000-000. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Johnson T.P. Snowball sampling. Encycl. Biostat. 2005;7 doi: 10.1002/0470011815.b2a16070. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kadykalo A.N., Haddaway N.R., Rytwinski T., Cooke S.J. Ten principles for generating accessible and useable COVID‐19 environmental science and a fit‐for‐purpose evidence base. Ecol. Solutions and Evidence. 2021;2(1) doi: 10.1002/2688-8319.12041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim D.K.D., Kreps G.L. World Med. Health Policy; 2020. An Analysis of Government Communication in the United States during the COVID‐19 Pandemic: Recommendations for Effective Government Health Risk Communication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirchherr J., Charles K. Enhancing the sample diversity of snowball samples: recommendations from a research project on anti-dam movements in Southeast Asia. PLoS One. 2018;13 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0201710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosinski M., Matz S.C., Gosling S.D., Popov V., Stillwell D. Facebook as a research tool for the social sciences: Opportunities, challenges, ethical considerations, and practical guidelines. Am. Psychol. 2015;70:543–556. doi: 10.1037/a0039210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McEwan T. 2020. Pandemic Fishing Hooks New Anglers in Alberta As Permit Sales Increase.https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/edmonton/fishing-alberta-pandemic-1.5726943 [Google Scholar]

- McManus A., Hunt W., Storey J., White J. 2011. Identifying the Health and Well-being Benefits of Recreational Fishing. FRDC Project Number: 2011/217.http://hdl.handle.net/20.500.11937/27359 [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen V.M., Rudd M.A., Hinch S.G., Cooke S.J. Recreational anglers’ attitudes, beliefs, and behaviors related to catch-and-release practices of Pacific salmon in British Columbia. J. Environ. Manage. 2013;128:852–865. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2013.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen V.M., Young N., Cooke S.J., Hinch S. Getting past the blame game: convergence and divergence in perceived threats to salmon resources among anglers and Indigenous fishers in Canada’s lower Fraser River. Ambio. 2016;45:591–601. doi: 10.1007/s13280-016-0769-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen K. 2020. A Timeline of the Novel Coronavirus in Ontario.https://globalnews.ca/news/6859636/ontario-coronavirus-timeline/ [Google Scholar]

- Paradis Y., Bernatchez S., Lapointe D., Cooke S.J. Can you fish in a pandemic? An overview of recreational fishing management policies in North America during the COVID-19 crisis. Fisheries. 2021;46:81–85. [Google Scholar]

- Penrod J., Preston D.B., Cain R.E., Starks M.T. A discussion of chain referral as a method of sampling hard-to-reach populations. J. Transcult. Nurs. 2003;14:100–107. doi: 10.1177/1043659602250614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinder A.C., Raghavan R., Britton J.R., Cooke S.J. COVID-19 and biodiversity: the paradox of cleaner rivers and elevated extinction risk to iconic fish species. Aquat. Conserv. 2020;30(6):1061–1062. doi: 10.1002/aqc.3416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- QSR International . 1999. NVivo Qualitative Data Analysis Software Version 12.https://qsrinternational.com/nvivo/nvivo-products/ Available from. [Google Scholar]

- Rice W.L., Mateer T.J., Reigner N., Newman P., Lawhon B., Taff B.D. Changes in recreational behaviors of outdoor enthusiasts during the COVID-19 pandemic: analysis across urban and rural communities. J. Urban Ecol. 2020;6 doi: 10.1093/jue/juaa020. juaa020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts K., Dowell A., Nie J.B. Attempting rigour and replicability in thematic analysis of qualitative research data; a case study of codebook development. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2019;19:1–8. doi: 10.1186/s12874-019-0707-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutz C., Loretto M.C., Bates A.E., Davidson S.C., Duarte C.M., Jetz W., Johnson M., Kato A., Kays R., Mueller T., Primack R.B., Ropert-Coudert Y., Tucker M.A., Wikelski M., Cagnacci F. COVID-19 lockdown allows researchers to quantify the effects of human activity on wildlife. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2020;4:1–4. doi: 10.1038/s41559-020-1237-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan E. 2020. Lessons from the Coronavirus Pandemic for Environmental Governance.https://seeingthewoods.org/2020/05/31/lessons-from-the-coronavirus-pandemic-for-environmental-governance/ [Google Scholar]

- Schneider D., Harknett K. What’s to like? Facebook as a tool for survey data collection. Sociol. Method Res. 2019;(November):1–33. doi: 10.1177/0049124119882477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sotiriadou P., Wicker P. Examining the participation patterns of an ageing population with disabilities in Australia. Sport Manage. Rev. 2014;17:35–48. doi: 10.1016/j.smr.2013.04.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Standl F., Joeckel K.H., Kowall B., Schmidt B., Stang A. Subsequent waves of viral pandemics, a hint for the future course of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic. medRxiv. 2020 doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30648-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Steffen W., Crutzen P.J., McNeill J.R. The Anthropocene: are humans now overwhelming the great forces of nature. Ambio. 2007;36:614–621. doi: 10.1579/0044-7447(2007)36[614:TAAHNO]2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stokes Y., Vandyk A., Squires J., Jacob J.-D., Gifford W. Using facebook and LinkedIn to recruit nurses for an online survey. West. J. Nurs. Res. 2019;41:96–110. doi: 10.1177/0193945917740706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szolnoki G., Hoffmann D. Online, face-to-face and telephone surveys—comparing different sampling methods in wine consumer research. Wine Econ. Policy. 2013;2:57–66. doi: 10.1016/j.wep.2013.10.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tarrant M.A., Manfredo M.J., Bayley P.B., Hess R. Effects of recall bias and nonresponse bias on self-report estimates of angling participation. N. Am. J. Fish. Manag. 1993;13:217–222. doi: 10.1577/1548-8675(1993)013<0217:EORBAN>2.3.CO;2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas D.R. A general inductive approach for analyzing qualitative evaluation data. Am. J. Eval. 2006;27:237–246. doi: 10.1177/1098214005283748. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas M. 2020. Fishing License Sales Jump 20% With Covid-19 Outdoor Recreation Boom.https://triblive.com/news/pennsylvania/fishing-license-sales-jump-20-with-covid-19-outdoor-recreation-boom/ [Google Scholar]

- Topolovec-Vranic J., Natarajan K. The use of social media in recruitment for medical research studies: a scoping review. J. Med. Internet Res. 2016;18:e286. doi: 10.2196/jmir.5698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Bavel J.J., Baicker K., Boggio P.S., Capraro V., Cichocka A., Cikara M., Crockett M.J., Crum A.J., Douglas K.M., Druckman J.N., Drury J., Dube O., Ellemers N., Finkel E.J., Fowler J.H., Gelfand M., Han S., Haslam S.A., Jetten J., Kitayama S., Mobbs D., Napper L.E., Packer D.J., Pennycook G., Peters E., Petty R.E., Rand D.G., Reicher S.D., Schnall S., Shariff A., Skitka L.J., Smith S.S., Sunstein C.R., Tabri N., Tucker J.A., van der Linden S., van Lange P., Weeden K.A., Wohl M.J.A., Zaki J., Zion S.R., Willer R. Using social and behavioural science to support COVID-19 pandemic response. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2020;4:460–471. doi: 10.1038/s41562-020-0884-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.