Abstract

The shutdown in economic activity due to the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) crisis has resulted in a short-term decline in global carbon emissions, but the long-term impact of the pandemic on the transition to a low-carbon economy is uncertain. Looking at previous episodes of financial and economic stress to draw implications for the current crisis, we find that tighter financial constraints and adverse economic conditions are generally detrimental to firms’ environmental performance, reducing green investments. The COVID-19 crisis could thus potentially slow down the transition to a low-carbon economy. These findings underline the importance of climate policies and green recovery packages to boost green investment and support the energy transition.

Keywords: Corporate sustainability, Climate change, Transition risks

1. Introduction

The shutdown in economic activity as a result of the COVID-19 crisis has resulted in a temporary decline in global carbon emissions, but the long-term impact of the pandemic on the transition to a low-carbon economy remains uncertain. While the economic fallout from the crisis may constrain firms’ ability to invest in green projects, thus slowing down the transition, the COVID19 crisis could also induce a structural shift in consumer and investor preferences toward environmentally friendly products, providing an opportunity to introduce mitigation policies that help diversify away from fossil fuel production.

Against this backdrop, in this paper we aim to address the following key questions: (1) How has the COVID-19 crisis affected green investments? (2) What can be learned from past economic crises about the likely behavior of the corporate sector in the near and medium terms with respect to the greening of the economy?

First, we document that the COVID-19 crisis has not led to a sustained decline in green financing so far. In fact, flows into sustainable funds and the performance of sustainable assets has been robust. However, there is a real risk that the COVID-19 crisis may adversely affect the transition to a low-carbon economy, notwithstanding the possibility that it induces a structural shift in preferences that leads to a greater focus on climate-related risks by firms than in the past.

Second, focusing on a sample that extends from 2002 to 2019 and comprises 62 countries, we show that tighter financial constraints as well as economic downturns are associated with weaker environmental performance and lower levels of green investments by firms. These results suggest that adverse financial and economic shocks, which limit real activity and tighten firms’ financial constraints, could reverse progress in corporate environmental performance by several years.

Therefore, in the current context, public policies and recovery packages that boost green investments are warranted to support the transition to a low-carbon economy.1 Fostering growth of the sustainable finance sector through better disclosures, the development of green taxonomies, and product standardization may further help to mobilize green investments (IMF, 2019).

Our findings are related to a growing literature on corporate social responsibility (CSR) and firm-level performance. The paper most closely related to ours is (Hong et al., 2012) who focus on the United States and argue that less financially constrained firms have higher corporate social responsibility scores. Looking at the determinants of CSR, Ferrell et al. (2016) find that firms with fewer principal-agency problems engage more in CSR. Our results support the findings of Hong et al. (2012), while specifically focusing on firms’ environmental performance and extending the analysis to a broad panel of countries. Moreover, our analysis contributes to the literature with a novel analysis of the effects of aggregate shocks—global financial stress and real economic activity shocks—on firms’ environmental performance.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows. Section 2 discusses the development of the sustainable finance sector at the onset of the COVID-19 crisis. Section 3 provides an overview of the data and econometric framework to analyze how past economic and financial shocks have impacted firms’ environmental performance. Section 4 concludes with possible policy implications.

2. The COVID-19 crisis and financing the energy transition

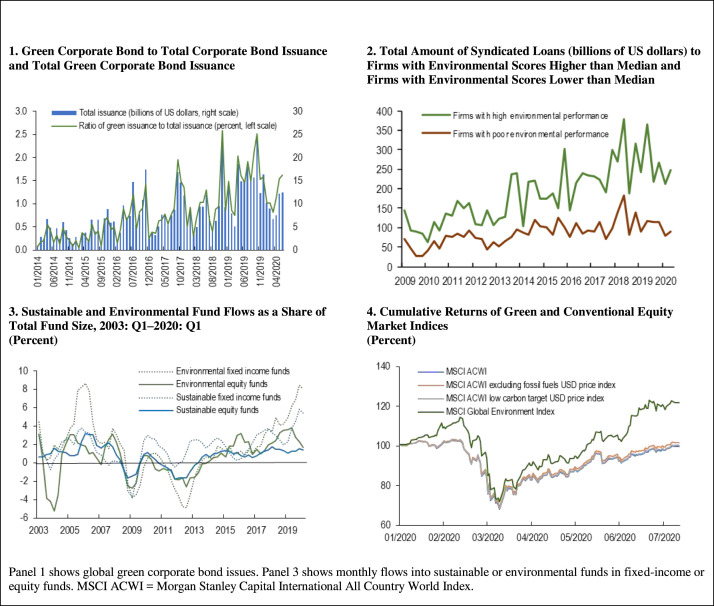

The COVID-19 crisis does not seem to have led to a sustained decline in green financing. The issuance of green corporate bonds, which has trended up over the past decade, declined in March 2020 during the peak of the financial market turmoil resulting from the crisis, but stayed well within the range of historical deviations (Fig. 1, panel 1). Issuance has picked up since then, with the share of green bonds in total corporate bond issuance more than doubling between March and June 2020. In the syndicated loan market, loans to firms with an above-median score in environmental performance have increased over the past decade compared with loans to firms with a below-median score.2 Lending to both types of firms dropped slightly in the first quarter of 2020 (Fig. 1, panel 2).

Fig. 1.

The COVID-19 crisis and Green investments.

Investment funds, especially fixed-income funds, with a focus on sustainable or environmental investments have continued to attract investment throughout the crisis, with only a small drop in aggregate inflows in some asset classes (Fig. 1, panel 3).3 A possible driver for the good performance of sustainable and environmental funds may have been the relatively high returns that green investments have generally experienced during this crisis (Fig. 1, panel 4).

Overall, the impact of the COVID-19 crisis on environmental finance thus seems to have been modest and short-lived. However, given the persistence and severity of the shock—in terms of the decline in output, the extent of potential scarring, and the heightened economic uncertainty, which are straining corporate balance sheets—it is difficult to say whether such trends will continue and what the overall impact of the crisis will be on firms’ actual environmental performance and on their ability to contribute sufficiently to global climate change mitigation efforts in the near and longer terms. In view of this, and to draw implications for the current pandemic crisis, the following analysis examines firms’ environmental performance during previous episodes of financial and economic stress.

3. Lessons from past economic crises for the energy transition during the COVID-19 crisis

3.1. Financial constraints and firms’ environmental performance

Drawing on Hong et al. (2012) and Dyck et al. (2019), we estimate the following baseline specification to evaluate the linkages between financial constraints and firms’ environmental performance (environmental score):

| (1) |

where indicates the environmental score for firm i in sector s, country c, and time t. , and are sector, country and time (year)-fixed effects, respectively. are firm-level controls such as the logarithm of total assets and earnings before interest and taxes. The variable is a firm-level financial constraint measure, which following the literature is defined in several alternative ways outlined below:

-

•

Firm size: captured by the logarithm of firm’s total assets, with large firms expected to be less financially constrained than smaller firms4 ;

-

•

Dividends: a dummy variable equal to one if a firm does not pay dividends, and is therefore considered as financially constrained, and zero otherwise;

-

•

Ratings: a dummy variable equal to one if a firm with a positive debt-to-asset ratio is not rated according to Standard and Poor’s, and hence may not have easy access to capital markets (indicating that it is financially constrained), and zero otherwise;

-

•

KZ score: a dummy variable equal to one if the Kaplan–Zingales score, an aggregate measure of financial constraints (Kaplan and Zingales, 1997), is above the median of its distribution; and zero otherwise;

-

•

Size–Age score: a dummy variable equal to one if the Size–Age score from Hadlock and Pierce (2010) is above the median of its distribution; and zero otherwise.

Our dataset comprises about 7000 listed firms—for which information on environmental performance is available—corresponding to 69 industries (as per the Global Industry Classification Standard) from 62 economies. The data is at annual frequency and covers the period 2002 to 2019. For summary statistics of the key variables of interest see Table 1. Information on environmental scores is obtained from Refinitiv and is based on 68 metrics covering three environmental categories: Resource use, Emissions, and Innovation. Category scores are calculated using a rank scoring methodology to evaluate firms’ environmental performance relative to all other firms each year. Firms’ overall environmental scores are then calculated from a weighted average of the category scores, where the category weights vary by industry. We use the proprietary environmental aggregate scores as our main dependent variable. These scores range between 0 (low performance) and 100 (high performance).

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics.

| Mean | Standard deviation | 25th percentile |

Median | 75th percentile |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | |

| Environmental scores (Aggregate) | 31.366 | 28.755 | 2.304 | 25.300 | 55.118 |

| Environmental investments initiatives | 0.142 | 0.349 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| Firm size [log(Total Assets)] | 14.595 | 2.085 | 13.325 | 14.590 | 15.873 |

| Ratings | 0.715 | 0.452 | 0.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| Dividends | 0.294 | 0.456 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 1.000 |

| Kaplan–Zingales score | 0.500 | 0.500 | 0.000 | 0.500 | 1.000 |

| Size–Age score | 0.000 | 0.461 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 1.000 |

Environmental score is the Refinitiv Asset4 Environmental Pillar Score. Environmental Investments Initiatives is a binary variable that takes value one if a firm undertakes environmental investments in year t. “Ratings” refers to firms that do not have a rating from Standard & Poor’s, “Size” to the log of total assets, “Dividends” to firms that do not pay dividends, “Kaplan Zingales score” to firms above the median of the Kaplan–Zingales index score distribution, and “Size–Age score” to firms with above the median of Size–Age score distribution.

The estimation results, reported in Table 2, show that tighter financial constraints are associated with worse environmental performance. The environmental performance of financially constrained firms for each measure is significantly weaker than that of unconstrained firms. Specifically, environmental performance falls by 10 points when firm size drops from the median to the 25th percentile of the firm size distribution. When a firm does not pay dividends or when it is not rated, its environmental score is 4 points and 3 points lower, respectively, than the score of dividend-paying and rated firms. The environmental score is about 2 and 3 points lower when the Kaplan–Zingales score or the Size–Age score is above the median of the sample distribution, respectively.5

Table 2.

Environmental performance and financial constraints.

| Ratings | Size | Dividends | Kaplan–Zingales score | Size–Age score | Ratings | Ratings | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | |

| Financial constraint measure | −3.226*** | −9.848*** | −4.111*** | −1.656*** | −2.818*** | −3.107*** | −1.764*** |

| (0.490) | (0.177) | (0.532) | (0.470) | (0.576) | (0.498) | (0.433) | |

| Control variables | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Country, Sector, and time fixed effects | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No |

| Country-time, sector fixed effects | No | No | No | No | No | Yes | No |

| Firm and time fixed effects | No | No | No | No | No | No | Yes |

| R2 | 0.491 | 0.489 | 0.493 | 0.480 | 0.490 | 0.505 | 0.445 |

| Observations | 54,106 | 54,106 | 53,482 | 46,853 | 54,106 | 54,106 | 54,461 |

| # of firms | 7016 | 7016 | 6925 | 6144 | 7016 | 7016 | 7080 |

This table reports regression estimates of environmental scores on measures of financial constraints and control variables. The data are from Refinitiv Datastream and Standard and Poor’s. “Size” is the log of total assets, and the sign of this variable is reversed so that higher values indicate smaller firms). All right-hand side variables are lagged by one year. Control variables are firm size (log of total assets) and firm profitability (earnings before interest expense and income taxes). Standard errors are clustered at the firm level. ***, **, or * indicates that the coefficient estimate is significant at the 1%, 5%, or 10% level, respectively.

It is conceivable that firms with high levels of environmental performance also happen to be less constrained. For example, well-governed firms may both be less likely to become constrained and may also be more likely to invest in corporate social responsibility (Ferrell et al., 2016). To control for such time invariant firm-level characteristics we also consider firm fixed effects. Similarly, to control for macroeconomic conditions that could be a driver of both CSR and financial constraints (such as accommodative monetary policy or strong economic growth), we include country-time fixed effects. Our original conclusions are robust to these changes (columns (6) and (7) of Table 2).67

3.2. Firms’ environmental performance and macro-financial shocks

Adverse macro-financial shocks that increase uncertainty and dampen economic activity can amplify firms’ financial constraints and significantly impede their ability to invest in green projects, thereby weakening their environmental performance.8 To assess the impact of macro-financial shocks on firms’ environmental performance, two types of shocks are analyzed here: (1) a global financial stress shock (proxied by the Chicago Board Options Exchange Volatility Index, VIX) and (2) a real economic activity shock capturing a sudden drop in domestic output.

The following model is estimated to evaluate the dynamic responses of firms’ environmental performance to these shocks:

| (2) |

where i is a firm, s is a sector, c is the economy and t is time (year). denotes the horizon of the projection. is the environmental score from Refinitiv. and are sector and country fixed effects. are firm-level controls: the logarithm of total assets and earnings before interest and taxes. The macroeconomic controls include the price of oil (logarithm of the WTI), country-specific output gaps, and the VIX.

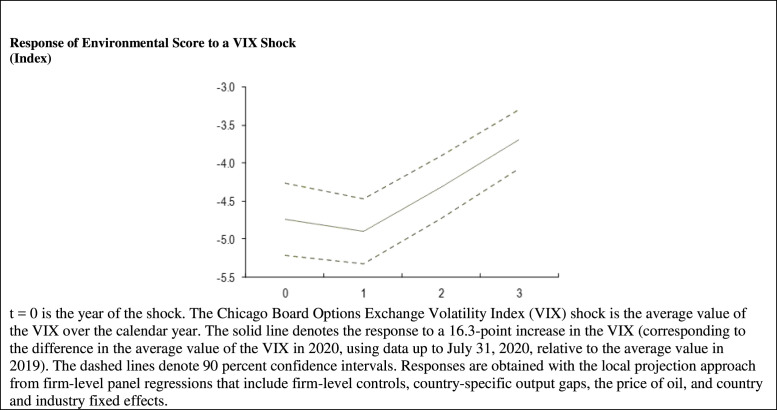

The analysis shows that a sudden jump in the VIX, comparable to that observed during the first half of 2020 in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, would lead to a persistent drop in firms’ environmental performance by up to 5 points, with the pre-shock performance level not attained for at least three years after the shock (Fig. 2).9 Absent policy actions and behavioral changes, this would imply that average corporate environmental performance would return to the levels that prevailed in 2006.

Fig. 2.

Environmental Performance and a VIX shock.

Moreover, to test the conjecture that financial stress weakens corporate environmental performance when firms are financially constrained, we augment Eq. (2) by interacting VIX with a financial constraint measure. The results show that the adverse effect of global financial shocks on environmental performance is magnified when firms are financially constrained (Table 3). For example, for firms not paying dividends or for unrated firms in 2019, the global financial stress shock observed thus far in 2020 is estimated to lower environmental performance by 1 and 2 additional points, respectively, compared with dividend-paying or rated firms. As above, the findings are robust to the inclusion of firm fixed effects to control for time invariant firm-level characteristics.

Table 3.

Environmental performance, financial stress and financial constraints.

| Ratings | Size | Dividends | Kaplan–Zingales score | Size–Age score | Ratings | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | |

| VIX | −0.291*** | −0.243*** | −0.987*** | −0.288*** | −0.226*** | −0.305*** | −0.240*** |

| (0.017) | (0.024) | (0.146) | (0.018) | (0.025) | (0.787) | (0.022) | |

| VIX x Financial constraint measure | −0.098*** | −0.045*** | −0.066 | −0.048 | 0.047 | −0.046** | |

| (0.034) | (0.177) | (0.044) | (0.037) | (0.037) | (0.022) | ||

| Control variables | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Country and Sector Fixed Effects | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

| Firm Fixed Effects | No | No | No | No | No | No | Yes |

| R2 | 0.443 | 0.453 | 0.451 | 0.454 | 0.445 | 0.453 | 0.247 |

| Observations | 53,118 | 53,489 | 53,489 | 52,294 | 45,073 | 53,489 | 53,844 |

| # of firms | 6838 | 6908 | 6908 | 6667 | 5906 | 6908 | 6971 |

This table reports regression estimates of environmental scores on the VIX and control variables. The data are from Refinitiv Datastream and Standard and Poor’s. The estimation frequency is annual, and the estimation sample extends from 2002 to 2019. Control variables are the domestic output gap, the log of the price of oil (WTI), as well as firm size (log of total assets), firm profitability (earnings before interest expense and income taxes) and a dummy for firms that do not pay dividends. “Size” is the log of total assets, and the sign of this variable is reversed so that higher values indicate smaller firms). Standard errors are clustered at the firm level. ***, **, or * indicates that the coefficient estimate is significant at the 1%, 5%, or 10% level, respectively.

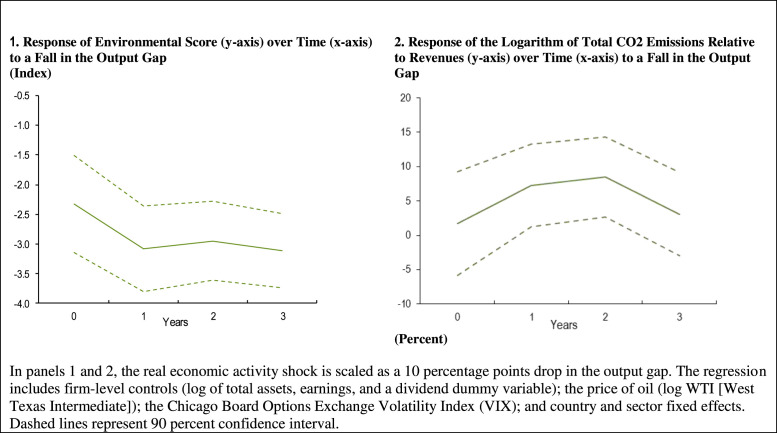

Turning to the analysis of a sudden drop in economic activity, a large decline in the output gap (10 percentage points, about 50 percent larger than that observed in the Group of Seven (G7) economies during the global financial crisis), would lead to a 3 point decline in firms’ environmental performance in the medium term (Fig. 3, panel 1).10 Similarly, firms’ carbon intensity—captured by their total carbon emissions relative to revenue—could increase by up to 8.5 percent in the medium term after such a decline in the output gap (Fig. 3, panel 2), even though the initial response of carbon intensity to economic shocks may be small because of the cyclical dynamics of carbon dioxide emissions observed amid recessions (Hale and Leduc, 2020).

Fig. 3.

Economic shocks and environmental performance.

3.3. Financial constraints and firms’ investments in Green technologies

A key channel through which financial constraints can affect firms’ environmental performance is through investments in green technologies, as constrained firms may postpone or reduce such investments if they do not directly contribute to revenue generation. Moreover, financially constrained firms may face difficulties in borrowing against future profits to invest in research and development, consequently postponing investments in intangibles that could potentially improve their environmental performance.

We test this hypothesis using the following Probit model:

| (3) |

where is the cumulative distribution of the normal function and is a binary variable that indicates whether a firm i, in sector s, economy c undertakes environmental investments in year t.11 are sector, country and time fixed effects. is one of the five firm-level financial constraints defined above, and are the same firm-level controls as in the previous analysis to control for observable firm characteristics.

Table 4 shows that financially constrained firms are indeed less likely to make investments that reduce future environmental risks, such as treatment of emissions or installation of cleaner technologies. For example, the probability that a firm will make an environmental investment falls by 6 percentage points when firm size drops from the median to the 25th percentile of the firm size distribution. Similarly, a firm unable to pay dividends has a 3 percentage points lower likelihood of making a green investment.12

Table 4.

Environmental investment decisions and financial constraints.

| Ratings | Size | Dividends | Kaplan–Zingales score | Size–Age score | Ratings | Size | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | |

| Financial constraint measure | −0.052 | −0.344*** | −0.190*** | −0.025 | −0.068 | 0.055 | −0.170*** |

| (0.041) | (0.177) | (0.048) | (0.037) | (0.043) | (0.037) | (0.012) | |

| Control variables | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Country, Sector, and time fixed effects | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No |

| Macroeconomic controls | No | No | No | No | No | Yes | Yes |

| Log-likelihood | −16 901 | −16 905 | −16 784 | −15 062 | −16 898 | −20 935 | −19 769 |

| Observations | 54,222 | 54,222 | 53,593 | 46,946 | 54,222 | 54,608 | 54,537 |

| # of firms | 7044 | 7044 | 6965 | 6169 | 7044 | 7088 | 7073 |

This table reports regression estimates of environmental investment decisions on measures of financial constraints and control variables. The data are from Refinitiv Datastream and Standard and Poor’s. “Size” is the log of total assets, and the sign of this variable is reversed so that higher values indicate smaller firms). All right-hand side variables are lagged by one year. Control variables are firm size (log of total assets) and firm profitability (earnings before interest expense and income taxes). Standard errors are clustered at the firm level. ***, **, or * indicates that the coefficient estimate is significant at the 1%, 5%, or 10% level, respectively.

4. Conclusion

The COVID-19 crisis has resulted in a temporary decline in global carbon emissions, but the long-term impact of the crisis is uncertain. While the crisis may increase awareness of catastrophic risks and bring about a major shift in consumer preferences, corporate actions, and investor behavior, the analysis presented in this paper suggests that there is a real possibility that, barring policy interventions, investment by firms to improve their environmental performance may decline in this time of macro-financial stress.

To achieve the reduction in emissions needed to keep global warming below 2 °C, an increase in green investments, in combination with steadily rising carbon prices, is critical (IMF, 2020). Public policies and green recovery packages to support firms’ environmental performance during the COVID-19 crisis are therefore warranted.

In addition, to alleviate firms’ financial constraints and to aid green investment, it would be key to put in place policies that support the sustainable finance sector, such as better disclosure standards, development of green taxonomies, and product standardization (see IMF, 2019).

Going forward, macro-financial models that take climate change into account may be able to shed further light on the interactions between macro-financial stress, environmental performance, and economic policies (see e.g. Yang, 2021, Diluiso et al., 2020).

The views expressed in this paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the IMF, its Executive Board, or IMF management. We would like to thank Pierpaolo Grippa, Harrison Hong, Samuel Mann, Fabio Natalucci, Mahvash Qureshi, Jérôme Vandenbussche, Germán Villegas Bauer, and Yizhi Xu, as well as participants at IMF seminars for helpful comments and suggestions at different stages of this project. Ken Gan and Oksana Khadarina provided excellent research assistance. Additional results are reported in the working paper version of this paper.

As noted in IMF (2020), an initial green investment push combined with steadily rising carbon prices could deliver the needed reductions in emissions to reach net zero emissions by 2050.

Firm-level environmental, social, and corporate governance data come with several caveats. First, the data cover only publicly listed firms. Second, there is a lack of standardization and transparency across data providers. Hence, environmental scores from different providers may capture different features of environmental performance. Third, as some scores are self-reported by firms, accuracy may vary across the sample.

Sustainable funds explicitly indicate all kinds of sustainability; impact; and environmental, social, and corporate governance (ESG) strategies in their prospectus. See IMF (2019) for a discussion of sustainable finance and financial stability.

The results are robust to alternative definitions of the financial constraint variables (see the working paper version of this paper).

For brevity, the specification with firm and time fixed effects, as well as country-time fixed effects, is presented only for one measure of financial constraint (rating status). The results with firm fixed effects are qualitatively robust when using alternative measures of financial constraints.

Similar results are obtained when considering two sub-categories of the environmental score directly related to climate change, firms’ emissions and their resource use.

For example, Gulen and Ion (2016) document the negative effect of aggregate uncertainty on firm-level investment. Caggiano et al. (2014) find that uncertainty shocks lead to a contraction in economic activity and that the effects of uncertainty on economic activity are stronger in recessions than expansions.

The analysis is robust to using alternative definitions of financial stress shocks (see the working paper version of this paper).

Other more global measures of economic activity shocks such as the forecast error for the current-year global GDP growth relative to the April WEO or the global economic activity shock from Baumeister and Hamilton (2019) also suggest a fall in corporate environmental performance in the medium term.

Specifically, it is the answer to the following question: “Does the company report on making proactive environmental investments or expenditures to reduce future risks or increase future opportunities? (i) investment made in the current fiscal year to reduce future risks and increase future opportunities related to the environment; (ii) investments made in new technologies to increase future opportunities; (iii) treatment of emissions (e.g., expenditures for filters, agents); (iv) installation of cleaner technologies”.

Several robustness checks have been performed to assess the robustness of this analysis: (i) alternative definitions of the financial constraint variables; (ii) replacing country fixed effects with variables capturing climate policies; (iii) to circumvent the incidental parameters problem that may arise in non-linear panel data models, replacing fixed effects with the lagged country-specific output gaps, the lagged price of oil and the lagged VIX; (iv) the use of a balanced panel of firms, starting from 2010. The original conclusions are robust to these changes (see the working paper version of this paper).

In the estimations, the sign of this variable is reversed such that higher values indicate smaller firms. The rationale for using size as a measure of financial constraints is that small firms are typically young and less well known, hence more vulnerable to capital market imperfections (Almeida et al., 2004).

References

- Almeida Heitor, Campello Murillo, Weinback Michael S. The cash flow sensitivity of cash. J. Finance. 2004;59(4):1777–1804. [Google Scholar]

- Baumeister Christiane, Hamilton James D. Structural interpretation of vector autoregressions with incomplete identification: Revisiting the role of oil supply and demand shocks. Am. Econ. Rev. 2019;109(5):1873–1910. [Google Scholar]

- Caggiano Giovanni, Castelnuovo Efrem, Groshenny Nicolas. Uncertainty shocks and unemployment dynamics in U.S. recessions. J. Monetary Econ. 2014;67:78–92. [Google Scholar]

- Diluiso Francesca, Annicchiarico Barbara, Kalkuhl Matthias, Minx Jan. CESifo; 2020. Climate Actions and Stranded Assets: The Role of Financial Regulation and Monetary Policy: CESifo Working Paper Series 8486. [Google Scholar]

- Dyck Alexander, Lins Karl V., Roth Lukas, Wagner Hannes F. Do institutional investors drive corporate social responsibility? International evidence. J. Financ. Econom. 2019;131(3):693–714. [Google Scholar]

- Ferrell Allen, Liang Hao, Renneboog Luc. Socially responsible firms. J. Financ. Econom. 2016;122(3):585–606. [Google Scholar]

- Gulen Huseyin, Ion Mihai. Policy uncertainty and corporate investment. Rev. Financ. Stud. 2016;29(3):523–564. [Google Scholar]

- Hadlock Charles J., Pierce Joshua R. New evidence on measuring financial constraints: Moving beyond the KZ index. Rev. Financ. Stud. 2010;23(5):1909–1940. [Google Scholar]

- Hale Galina, Leduc Sylvain. FRBSF Economic Letter. Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco; 2020. COVID-19 and CO2. July 6. [Google Scholar]

- Hong Harrison, Kubik Jeffrey D., Scheinkman José A. National Bureau of Economic Research; Cambridge, MA: 2012. Financial Constraints on Corporate Goodness: NBER Working Paper 18476. [Google Scholar]

- International Monetary Fund (IMF) Global Financial Stability Report. 2019. Sustainable finance: Looking farther. Chapter 6. [Google Scholar]

- International Monetary Fund (IMF) World Economic Outlook. 2020. Mitigating climate change. Chapter 3. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan Steven N., Zingales Luigi. Do investment-cash flow sensitivities provide useful measures of financial constraints? Q. J. Econ. 1997;112:169–215. [Google Scholar]

- Yang Biao. Mimeo; 2021. Explaining Greenium in a Macro-Finance Integrated Assessment Model. [Google Scholar]