Abstract

Background and study aims Underwater endoscopic mucosal resection (UEMR) does not always result in en bloc resection of large colorectal lesions. The aim of this study was to demonstrate the feasibility of en bloc resection with progressive polyp contraction with underwater endoscopic mucosal resection (PP-CUE) of large, superficial colorectal lesions. The advantage of PP-CUE is to enable resection of a superficial non-polypoid lesion that is larger than the snare diameter.

Patients and methods Eleven consecutive lesions in ten patients who underwent UEMR with PP-CUE of large superficial colorectal lesions (20 mm or greater) were included.

Results The median lesion diameter was 24 mm (interquartile range [IQR], 20–24 mm). All lesions were larger than the 15-mm rotatable snare that was used. Median procedure time and PP-CUE time were 11 minutes (IQR, 8.5–12.3) and 2.3 minutes (IQR, 1.9–3.4), respectively. Pathological diagnoses of resected specimens included six adenomas, three sessile serrated lesions, and two slightly invasive submucosal carcinomas. En bloc and R0 resection rates were both 91 % (10/11). No adverse events occurred.

Conclusions PP-CUE is useful to resect superficial non-polypoid colorectal lesions 20 to 25 mm in diameter in an en bloc fashion.

Introduction

Video 1 PP-CUE of a laterally spreading tumor, granular type (LST-G), in the transverse colon. 1) A 24-mm laterally spreading tumor, granular type (LST-G) with JNET Type 2A in the transverse colon. 2) Placing the snare tip at normal mucosa beyond the lesion while securing an adequate proximal margin. 3) Opening the snare while keeping the snare tip at normal mucosa to stretch the proximal mucosa to capture it without skipped areas. 4) Capturing most of the lesion while confirming the margin. 5) Opening the snare again while fixing the snare tip at normal mucosa. 6) Ensnaring uncaptured lesion and more surrounding mucosa with direct visual confirmation 7) The lesion is progressively contracted by repeated snaring to assure complete resection. 8) Cutting with pure-cut mode diathermy. 9) Confirming there are no residual lesion fragments. 10) Closing with endoclips while maintaining water immersion. 11) Tubulovillous adenoma with a negative margin.

Endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) has become a standard endoscopic treatment for large, superficial colorectal lesions in east Asian countries and is becoming more commonly performed in western countries. Recently, establishing ESD techniques and developing dedicated devices have made colorectal ESD easier and safer. However, ESD is still technically challenging for most endoscopists. Dedicated ESD devices including ESD knives, hemostatic forceps, and traction devices are more expensive than routinely used endoscopic devices such as loop snares. In addition, most colorectal ESDs require more highly skilled support staff to assist the operating endoscopist. ESD procedures occupy the endoscopy suites for a much longer time than conventional endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR). However, conventional EMR does not facilitate en bloc resection of large colorectal lesions. High local recurrence rates were detected at follow-up colonoscopy after piecemeal EMR (12 %–26 %) 1 2 3 4 .

Underwater EMR without submucosal injection (UEMR) was reported as a revolutionary approach to EMR for the resection of large sessile colon lesions by Binmoeller et al. in 2012 5 . Although the efficacy and safety of UEMR for large superficial colorectal lesions has been fully evaluated and widely disseminated 6 , lesions larger than the snare diameter cannot always be resected in an en bloc fashion even using UEMR. A snare that is too large cannot be controlled well in the contracted intestinal lumen filled with water. Further, the endoscopic visual field with water immersion is narrower than in air due to a difference in the refractive index of light, which may lead to positive horizontal margins of UEMR specimens. Therefore, even with UEMR, a large lesion can hardly be captured in the snare to allow visual confirmation of its margin.

We previously reported on the utility of progressive polyp contraction with underwater endoscopic mucosal resection (PP-CUE) in 2020 as a case report 7 ( Fig. 1 , Fig. 2 , Video 1 ). We have performed PP-CUE for superficial colorectal lesions > 20 mm diameter for which en bloc resections cannot be performed without ESD. The main advantage of PP-CUE is enabling resection of a superficial lesion that is larger than the snare diameter. The aim of this study was to demonstrate the feasibility of en bloc resection with PP-CUE for superficial non-polypoid colorectal lesions > 20 mm in diameter.

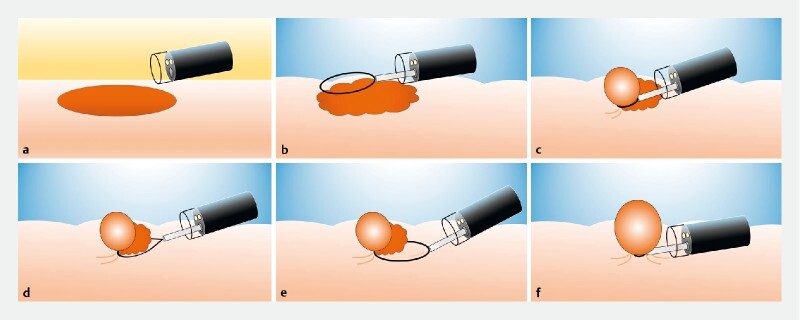

Fig. 1 .

Schema for progressive polyp contraction underwater endoscopic mucosal resection (PP-CUE). a A large, flat, superficial colorectal lesion is extended with insufflation. b Although the lesion contracts with water immersion, a medium-size snare with controllable size cannot capture the entire lesion if it is too large, even in the contracted narrow intestinal lumen after water immersion. c The far side of the lesion is securely captured by the snare under direct visualization, identifying the lesion margin and involving as much area of the lesion as possible. Then, the lesion is captured to a certain extent without damaging it. d The snare is carefully opened again while hooking the far side of the strangulated protrusion. e The snare is pulled back to include the remaining part of the lesion before the previously snared area can extend again. f The entire lesion is completely captured within the snare.

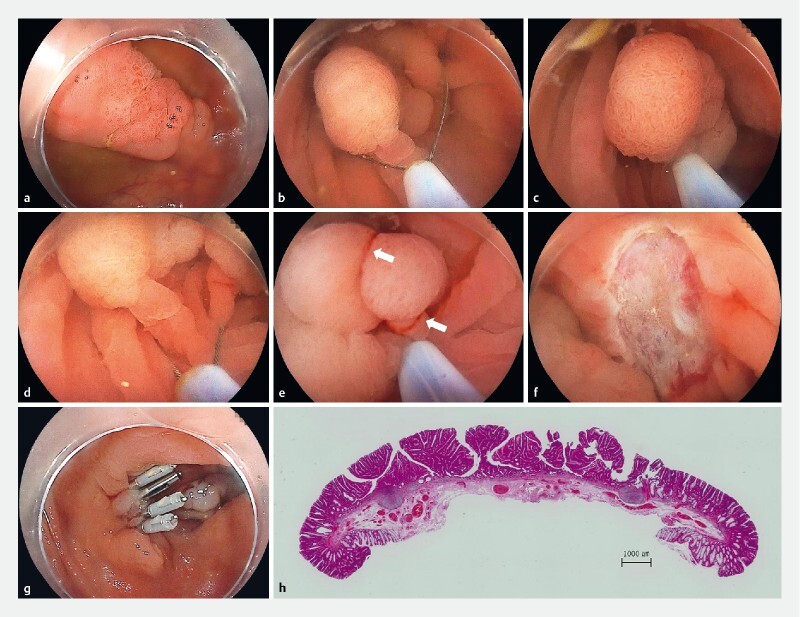

Fig. 2 .

Sequential endoscopic images of the PP-CUE procedure. a A 24-mm laterally spreading lesion, granular type with Kudo’s type IV pit pattern, Type 2A of the Japan narrow band imaging expert team (JNET) classification in the transverse colon. b The tumor morphology was transformed from flat to protruded after water immersion. Most of the lesion was captured in the snare, with direct visual confirmation of the margin. c The snare was carefully closed until resistance was felt through the snare handle. d The snare was opened again while fixing the snare tip at the normal mucosa. e Ensnaring the uncaptured part of the lesion and more surrounding mucosa with direct visual confirmation. The lesion was progressively contracted by repeated snaring to assure complete resection. Arrows indicate the first and second snaring marks. f The specimen was cut with pure-cut mode diathermy. There were no residual fragments of lesion nor sites of perforation. g The mucosal defect was completely closed with endoclips. h Pathology was a tubulovillous adenoma with negative margins.

Patients and methods

Study population

The inclusion criteria were: (1) a superficial non-polypoid colorectal lesion, including sessile serrated lesions resected by UEMR; (2) no visible stigmata of invasive malignancy during magnified observation; (3) ≥ 20 mm size; (4) endoscope withdrawal recorded on video; and (5) use of PP-CUE. From January 2020 to February 2021, UEMR was performed for 130 superficial colorectal lesions at Jichi Medical University Hospital, and 11 lesions met the inclusion criteria. Medical records and endoscopic videos on which the entire endoscope withdrawal including PP-CUE was recorded were retrospectively reviewed. The Institutional Review Board approved this retrospective review (No. 20–103).

Procedure for progressive polyp contraction with underwater endoscopic mucosal resection

A submucosal injection was not used. While the submucosal layer is thickened when underwater, the muscularis propria remains circumferential and does not follow the involutions of the folds during UEMR ( Fig. 1 ) 5 . This allows high- quality endoscopic resection without the need for submucosal injection. PP-CUE was developed to allow resection of colorectal lesions larger than the diameter of a dedicated polypectomy snare. The decision to use PP-CUE is made when it is recognized that the target lesion is larger than the snare diameter. In short, the snare was embedded in the portion of a large, superficial lesion distal to the endoscope. After that, intentional and incomplete strangulation was performed without resection, such that the snare was gently closed until tactile resistance was felt in the handle. The snare then was reopened and the entire lesion was ensnared. After confirming that the whole lesion was captured, resection was completed with diathermy. The resulting mucosal defect was closed using endoclips immediately while maintaining water immersion ( Fig. 1 , Fig. 2 , Video 1 ).

A magnifying endoscope (EC-L600ZP or EC-760ZP-V/M, Fujifilm, Tokyo, Japan), carbon dioxide insufflator (GW-1 or GW-100, Fujifilm), water irrigator (JW-2, Fujifilm) with distilled water, transparent distal attachment (D-201-14304, Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) and diathermy unit (ESG-100, Olympus) were used. For resection, a 15-mm Rota snare (Medi-Globe GmbH, Achenmühle, Germany) was used for all PP-CUE. Reopenable endoclips (SureClip, Micro-Tech Co. Ltd., NanJing, China) and ordinary clips (EZ clip, Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) were used to close the mucosal defect.

Evaluation of PP-CUE

Procedure time was defined as the time between the start of water irrigation and closure of the mucosal defect by endoclip application. PP-CUE time was defined as the time between the snare exiting the working channel under endoscopic vision and confirmation of the mucosal defect. Lesions size was measured by comparison with the 15-mm width of the fully opened Rota snare. En bloc resection was defined as lesion resection in a single piece. R0 resection was defined as en bloc resection with negative pathological margins. Delayed bleeding was defined as hematochezia with a decrease of hemoglobin level > 2 g/dL, requiring transfusion or endoscopic hemostasis within 14 days after the procedure. Intraprocedural perforation was defined as visualization of the peritoneal cavity through damaged muscularis during PP-CUE, and delayed perforation was defined as presence of free air on computed tomography scan with abdominal symptoms after the PP-CUE procedure even though there no intraprocedural perforation was seen.

Results

Table 1 shows the characteristics of lesions in patients who underwent PP-CUE. Ten lesions were in the right colon and one lesion was in the left colon. Tumor morphologies included nine 0-IIa and two 0-IIa + IIc. Median lesion diameter was 24 mm (IQR 20–24 mm, range 20–26 mm). All lesions were larger than the 15-mm rotatable snare used. Median procedure time and PP-CUE time were 11 minutes (IQR, 8.5–12.3) and 2.3 minutes (1.9–3.4), respectively. Pathological diagnoses of the resected specimens included six adenomas, three sessile serrated lesions, and two slightly invasive submucosal carcinomas. Magnifying endoscopy of the two slightly invasive submucosal carcinomas before PP-QUE was classified as Japan narrow band expert team (JNET) type 2A and 2B, indicating intramucosal cancer, but there were no visible stigmata of invasive cancer during magnified endoscopy 8 . The three sessile serrated lesions were JNET type 1. Both en bloc and R0 resection rates were 91% (10/11). The lesion with a failed en bloc resection was on the haustra. The lesion was resected in a two-piece fashion unintentionally because the tip of the Rota snare failed to capture the edge of the lesion distal to the endoscope. However, no residual lesion was observed around the mucosal defect even with magnified observation, and the pathological diagnosis was adenoma. No adverse events (AEs) occurred.

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of patients and outcomes.

| Number of lesions, n | 11 |

| Number of patients, n | 10 |

| Age, years, median (IQR) | 77 (62–80) |

| Gender, male/female, n | 8/2 |

| Tumor location, n (%) | |

|

10 (91 %) |

|

1 (9 %) |

| Macroscopic type, n (%) | |

|

9 (82 %) |

|

2 (18 %) |

| Tumor diameter, mm, median (IQR) | 24 (20–24) |

| Pathological findings, n (%) | |

|

6 (58 %) |

|

3 (25 %) |

|

2 (17 %) |

| Lymphovascular invasion, n (%) | 0 (0 %) |

| Cylindrical cap use, n (%) | 11 (100 %) |

| En bloc resection, n (%) | 10 (91 %) |

| R0 resection, n (%) | 10 (91 %) |

| Resected specimen diameter, mm, median (IQR) 1 | 24 (20–24) |

| Procedure time, min, median (IQR) | 11 (8.5–12.3) |

| PP-CUE time, min, median (IQR) | 2.3 (1.9–3.4) |

| Perforation, n (%) | 0 (0 %) |

| Delayed bleeding, n (%) | 0 (0 %) |

IQR, interquartile range; PP-CUE, progressive polyp contraction with underwater endoscopic mucosal resection.

Only lesions resected en bloc were included.

Discussion

In 11 consecutive lesions > 20 mm in diameter resected with PP-CUE, both en bloc and R0 resection rates were 91 % with short procedure times and without AEs. The major advantage is that PP-CUE enables resection of superficial lesions larger than the snare diameter. PP-CUE can be an alternative to performing piecemeal EMR or ESD for non-polypoid colorectal lesions ≥ 20 mm.

The “underwater revolution” recently has broken the mold for endoscopic resection. UEMR reportedly is safe and reliable for resection of not only superficial colorectal lesions but also superficial non-ampullary duodenal epithelial tumors 9 . The underwater technique is also useful to facilitate ESD 10 11 . However, the more UEMR is performed, the more its limitations are revealed. Although the en bloc resection rate using UEMR for colorectal non-polypoid lesions is as good as that of conventional EMR, both en bloc resection rates are lower when evaluating resections of > 20 mm lesions 12 . Risk of piecemeal resection is still considerable when performing UEMR for > 20 mm lesions. However, piecemeal resections have a high risk of local recurrence and require that patients are followed with short-interval surveillance colonoscopy 3 . If one performs endoscopic en bloc resection even for > 20 mm lesions with low malignant potential, such as serrated lesions without obvious dysplasia, ESD is an ideal choice, which makes the procedure more expensive and less cost-effective than piecemeal EMR. The present study shows that PP-CUE potentially achieves a high-rate of en bloc resections for superficial colorectal lesions ≥ 20 mm. A recent prospective randomized controlled trial revealed that en bloc and R0 resection rates for UEMR are not significantly different from conventional EMR 13 . The R0 resection rates for conventional EMR and UEMR for 20- to 30-mm lesions were 20.0 % and 37.7 %, respectively 13 , which means that PP-CUE achieved a much higher R0 resection rate (91 %) for > 20 mm lesions compared with both conventional EMR and UEMR. The present study also included an unexpected R0 resection of a T1a carcinoma using PP-CUE, although PP-CUE would not have been performed if the lesion had been correctly diagnosed as a T1a carcinoma.

Generally, a large snare is used to resect a large lesion. It is not easy to manipulate an entire snare > 20 mm even with gas insufflation because the tip of a large snare on the proximal side often goes beyond the visual field. Therefore, appropriate anchoring of the tip and subsequent capturing of the lesion while closing the snare may sometimes fail by slipping, which results in piecemeal resection. A large snare is more difficult to manipulate in the narrowed space due to intestinal contraction under water immersion. In addition, being underwater changes the reflective index of light with a further narrowed visual field. An intermediate-size rotatable snare such as a 15-mm Rota snare may be appropriate to perform UEMR because it represents a balance between maximal width and controllability. The tip of the intermediate-size snare can be placed at the normal mucosa beyond the lesion because the entire snare can be identified even in the narrowed endoscopic view under water immersion. Even if a targeted non-polypoid lesion is > 20 mm, PP-CUE can be used to completely resect it using an easily controllable intermediate-size rotatable snare by multiple snaring maneuvers that transiently make it smaller. Above all, PP-CUE is a useful technique when performed underwater without injection. In case of presence of submucosal injection, the first application of the snare makes a groove and subsequent applications of the snare tend to go back into the same groove. In the case of an air-filled lumen, the compressed polypoid shape after the first application of the snare does not remain and returns to its original flat shape easily due to intraluminal pressure. However, if it is performed underwater without injection, the compressed polypoid shape after the first application of the snare remains even after reopening the snare and an even larger area can be grasped by the next application of the snare because the mucosa floats in the water without tension. If a weak point of PP-CUE has to be described, it would be that the anchored tip of the snare cannot be observed during re-snaring. The failed en bloc resection of a lesion in this study was caused by failure to continuously capture the proximal edge of the lesion. Sure fixation of the snare tip to normal mucosa beyond the lesion may resolve this weakness 14 .

Conclusions

In conclusion, PP-CUE is useful to resect superficial non-polypoid colorectal lesions 20 to 25 mm in diameter in an en bloc fashion.

Footnotes

Competing interests Dr. Yamamoto has a consultant relationship with the Fujifilm Corporation and has received honoraria, grants, and royalties from the company.

References

- 1.Hotta K, Fujii T, Saito Y et al. Local recurrence after endoscopic resection of colorectal tumors. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2009;24:225–230. doi: 10.1007/s00384-008-0596-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Papparella L G, Barbaro F, Pecere S et al. Efficacy and safety of endoscopic resection techniques of large colorectal lesions: experience of a referral center in Italy. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;34:375–381. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0000000000002252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Belderbos T D, Leenders M, Moons L M et al. Local recurrence after endoscopic mucosal resection of nonpedunculated colorectal lesions: systematic review and meta-analysis. Endoscopy. 2014;46:388–402. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1364970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Terasaki M, Tanaka S, Oka S et al. Clinical outcomes of endoscopic submucosal dissection and endoscopic mucosal resection for laterally spreading tumors larger than 20 mm. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;27:734–740. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2011.06977.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Binmoeller K F, Weilert F, Shah J et al. “Underwater” EMR without submucosal injection for large sessile colorectal polyps (with video) Gastrointest Endosc. 2012;75:1086–1091. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2011.12.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yamashina T, Hanaoka N, Setoyama T et al. Efficacy of underwater endoscopic mucosal resection for nonpedunculated colorectal polyps: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Cureus. 2021;13:e17261. doi: 10.7759/cureus.17261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee R F, Nomura T, Hayashi Y et al. En bloc removal of a colonic polyp using progressive polyp contraction with underwater endoscopic mucosal resection: the PP-CUE technique. Endoscopy. 2020;52:E434–E436. doi: 10.1055/a-1147-1240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sano Y, Tanaka S, Kudo S E et al. Narrow-band imaging (NBI) magnifying endoscopic classification of colorectal tumors proposed by the Japan NBI Expert Team. Dig Endosc. 2016;28:526–533. doi: 10.1111/den.12644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kiguchi Y, Kato M, Nakayama A et al. Feasibility study comparing underwater endoscopic mucosal resection and conventional endoscopic mucosal resection for superficial non-ampullary duodenal epithelial tumor < 20 mm. Dig Endosc. 2020;32:753–760. doi: 10.1111/den.13524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Harada H, Nakahara R, Murakami D et al. Saline-pocket endoscopic submucosal dissection for superficial colorectal neoplasms: a randomized controlled trial (with video) Gastrointest Endosc. 2019;90:278–287. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2019.03.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Despott E J, Murino A. Saline-immersion therapeutic endoscopy (SITE): An evolution of underwater endoscopic lesion resection. Dig Liver Dis. 2017;49:1376. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2017.08.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Binmoeller K F, Hamerski C M, Shah J N et al. Attempted underwater en bloc resection for large (2-4 cm) colorectal laterally spreading tumors (with video) Gastrointest Endosc. 2015;81:713–718. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2014.10.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nagl S, Ebigbo A, Goelder S K et al. Underwater vs Conventional endoscopic mucosal resection of large sessile or flat colorectal polyps: a prospective randomized controlled trial. Gastroenterology. 2021;161:1460–1474 e1461. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2021.07.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nomura T, Nakamura H, Sugimoto S et al. Reopenable-clip band-assisted underwater endoscopic mucosal resection to obtain a large specimen. Endoscopy. 2022 doi: 10.1055/a-1860-1856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]