Abstract

Throughout the COVID-19 pandemic, the application of residual free chlorine has been emphasized as an effective disinfectant; however, the discharged residual chlorine is associated with potential ecological risk at concentrations even below 0.1 mg/L. However, the influence of free chlorine at ultralow-doses (far below 0.01 mg/L) on phytoplankton remains unclear. Due to limitations of detection limit and non-linear dissolution, different dilution rates (1/500, 1/1000, 1/5000, 1/10000, and 1/50000 DR) of a NaClO stock solution (1 mg/L) were adopted to represent ultralow-dose NaClO gradients. Two typical microalgae species, cyanobacterium Microcystis aeruginosa and chlorophyta Chlorella vulgaris, were explored under solo- and co-culture conditions to analyze the inhibitory effects of NaClO on microalgae growth and membrane damage. Additionally, the effects of ultralow-dose NaClO on photosynthesis activity, intracellular reactive oxygen species (ROS) production, and esterase activity were investigated, in order to explore physiological changes and sensitivity. With an initial microalgae cell density of approximately 1 × 106 cell/mL, an inhibitory effect on M. aeruginosa was achieved at a NaClO dosage above 1/10000 DR, which was lower than that of C. vulgaris (above 1/5000 DR). The variation in membrane integrity and photosynthetic activity further demonstrated that the sensitivity of M. aeruginosa to NaClO was higher than that of C. vulgaris, both in solo- and co-culture conditions. Moreover, NaClO is able to interfere with photosynthetic activity, ROS levels, and esterase activity. Photosynthetic activity declined gradually in both microalgae species under sensitive NaClO dosage, but esterase activity increased more rapidly in M. aeruginosa, similar to the behavior of ROS in C. vulgaris. These findings of differing NaClO sensitivity and variations in physiological activity between the two microalgae species contribute to a clearer understanding of the potential ecological risk associated with ultralow-dose chlorine, and provide a basis for practical considerations.

Keywords: Sodium hypochlorite, Microcystis aeruginosa, Chlorella vulgaris, Growth suppression, Co-culture

Graphical abstract

1. Introduction

Chlorine has been used widely during the COVID-19 pandemic as one of the most effective disinfectants for inactivating the SARS-CoV-2 virus (Bogler et al., 2020), and residual free chlorine has subsequently been emphasized in the effluent of wastewater treatment plants (Ministry-of-Ecology-and-Environment, 2020; WEF, 2020; Lu et al., 2021). Notably, water with free chlorine, even below 0.1 mg/L, is known to be toxic to sensitive aquatic species (Saeed et al., 2019; Añasco et al., 2008; Vannoni et al., 2018; Abarnou and Miossec, 1992). The potential ecological risk of chlorine, in the context of its increasing use and dosage, has therefore attracted attention. Stormwater samples have indicated that total active chlorine occasionally exceeds the permitted discharged level, posing a potential aquatic risk (Zhang et al., 2018). Enhanced disinfection wastewater has been reported to inhibit growth of phytoplankton and photosynthetic performance at least for 3 d (Kudela et al., 2017), and insufficient dechlorination in seawater has previously caused toxicity to marine polychaete embryos via residual chlorine (Pan et al., 2019).

Furthermore, acute toxicity from low chlorine on microalgae species has been explored. For bacillariophyta, NaClO at 0.2 mg/L caused immediate inhibition of photosynthesis, as well as algal growth suppression of Phaeodactylum tricornutum within 24 h of exposure in cooling wastewater (Ma et al., 2011). Both free and immobilized marine benthic diatoms were found to be sensitive to chlorinated seawater, even with total residual oxidants at an EC10 value of 0.02 mg/L on Achnanthes spp. (Vannoni et al., 2018). For cyanophyta Microcystis aeruginosa, rapid cell rupture within 30 min has been reported at 3 mg/L NaClO in tertiary treated effluent water (Fan et al., 2014a). For chlorophyta, NaClO at 0.1 mg/L induced growth inhibition within 6 h and caused a significant reduction in chlorophyll autofluorescence over 12 h in Closterium ehrenbergii (Sathasivam et al., 2016). A higher NaClO concentration, of 0.25–0.5 mg/L, was lethal to Chlorella vulgaris (Zargar and Ghosh, 2007). However, the influence of undetectable free chlorine at ultralow-dose (far below the detection limit of the N, N-diethyl-1, 4-phenylenediamine sulfate method, 0.01 mg/L) on phytoplankton growth within days remains unclear, especially under solo-cultivation and co-cultivation, which is very important for ecological risk assessment of chlorine in the real environment.

Based on previous reports, cell density and membrane integrity are two key parameters for evaluating damage to algal growth and viability. Furthermore, these parameters can also demonstrate chlorine sensitivity differences among various microalgae species. The kinetics of NaClO-induced inactivation of microorganisms are dependent on the production of hypochlorite ions (ClO−) and hypochloric acid (HClO) (Fukuzaki, 2006; Garoma and Yazdi, 2019) which react with various organics, leading to inactivation and decomposition of cellular elements such as amino acids (Hazell and Stocker, 1993; Hazell et al., 1994), proteins (Hawkins and Davies, 1998; Hawkins and Davies, 1999), fats (Spickett et al., 2000), and nucleic acids (Prutz, 1998). The physiological activities of microorganisms can be inhibited by NaClO through reduction in photosynthetic activity (Ma et al., 2011), decreases in esterase activity (Zhang et al., 2017), and production of intracellular reactive oxygen species (ROS) (Han et al., 2016). ROS represent the radicals and derivatives of oxygen generated by environmental stimulation (Halliwell, 2006), which may subsequently induce damage to the photosynthesis system (Kale et al., 2017). Esterase activity characterizes the intracellular metabolism of algal cells (Ebenezer et al., 2012), and the esterase activity of Microcystis aeruginosa may be a feasible monitor for potential ecological toxicity (Blanchette, 2006). Thus, the stress response level and reaction sequence among photosynthetic activity, ROS and esterase activity warrant substantial investigation for understanding the physiological changes induced by ultralow-dose chlorination.

The main objectives of this study are: (1) to investigate the inhibitory effects of ultralow-dose NaClO on cyanophyta Microcystis aeruginosa and chlorophyta Chlorella vulgaris, and their differences in physiological response; and (2) to assess the difference in sensitivity between the two microalgae species under solo-culture and co-culture conditions. This study contributes to a clearer understanding of the potential ecological risk of ultralow-dose chlorine and informs further practical considerations.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Microorganisms

Cyanophyta Microcystis aeruginosa (FACHB-905) and chlorophyta Chlorella vulgaris (FACHB-8) were obtained from the Freshwater Algae Culture Collection of the Institute of Hydrobiology (FACHB Collection; Wuhan, China), and incubated with sterile BG-11 medium (Andersen et al., 2005) at 25 °C. M. aeruginosa is the most widespread and health-threatening blooming cyanobacteria species (He et al., 2016), and C. vulgaris is also a typical chlorophyta in landscape water (Li et al., 2020a). The illumination intensity by cold white fluorescent lamps was kept at 2000–3000 Lux and the light/dark cycle was set as 12/12 h. The initial cell density of each solo-culture microalgae sample used for the experiment was approximately 1 × 106 cell/mL during the exponential phase. The co-culture microalgae samples were mixed with two equivoluminal microalgae samples, with an initial cell density of 2 × 106 cell/mL.

2.2. Chlorine exposure

The microalgae samples were exposed to sodium hypochlorite (NaClO) to establish different doses of chlorine. Free chlorine concentration was determined by the N, N-diethyl-1, 4-phenylenediamine sulfate method (Walter, 2005), with a detection limit of 0.01 mg/L. The stock solution of NaClO was prepared by diluting a commercial NaClO solution (10% w/v, Tianjin Fuyu Chemical, China) with Milli-Q water, and the free chlorine concentration of the stock solution was set at 1.00 mg/L. The relationship between the free chlorine concentration and dilution rate was determined, as shown in Fig. A1. Due to the detection limitation and non-linear dissolution, the concentrations of ultralow-dose chlorine doses were conducted with NaClO dilution rates (DR) of 1/500, 1/1000, 1/5000, 1/10000, and 1/50000. The theoretical calculated chlorine concentrations were 4.64 μg/L, 2.47 μg/L, 0.57 μg/L, 0.31 μg/L, and 0.07 μg/L, respectively. The control tests were set without the addition of chlorine, illustrated as 0 DR in the figures. Three parallel replications were conducted for each DR group. The dosages were presented as the number plus dilution rate, e.g. 1/500 DR represents the dosage of a 500 times dilution of the stock solution (1.00 mg/L free chlorine), so that the concentration of free chlorine is lower if the DR is lower.

Microalgae samples were taken and measured at 10 min, 30 min, 1 h, 4 h, 8 h, 12 h, 1 d, 4 d, and 7 d after chlorine exposure. At each time interval of sample collection, chlorination was quenched by addition of a sodium thiosulfate (Na2S2O3) solution at a stoichiometric ratio (Walter, 2005), which neither induced impact on microalgae cells nor reacted with the dyes for flow cytometry analysis.

2.3. Cell analysis through flow cytometry and PHYTO-PAM

Cell density, membrane integrity, reactive oxygen species (ROS), and esterase activity of the microalgae samples were analyzed by flow cytometry. A FACSCalibur flow cytometer (FCM, Becton Dickinson, USA) with an air-cooled 15 mW argon laser emitting at 488 nm was employed for all fluorescence measurements. The results obtained from the FCM were then post-processed using CellQuestTM Pro (Becton Dickinson). Microalgae sample analysis and data analysis was conducted according to the procedures and equations from previous studies (Zhou et al., 2020; Li et al., 2020a; Tao et al., 2010; Tao et al., 2013).

Cell density was determined by adding AccuCheck Counting Beads (Invitrogen, USA), following the procedures of previous research (Tao et al., 2010). In terms of the mixture of the two microalgae species, M. aeruginosa and C. vulgaris cells were detected with a proper voltage adjustment.

Cell membrane integrity was determined by double staining with SYBR green I (SYBR, Sigma, USA) and propidium iodide (PI, Invitrogen, USA), and were expressed as the percentage of the cells with damaged membrane to total cells (P md). The experimental procedure followed the description from a previous paper (Li et al., 2020a).

Intracellular oxidative stress was characterized by the concentration of reactive oxygen species (ROS), and intracellular ROS were measured by flow cytometry using 2′, 7′-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate (H2DCFDA, Sigma, USA), following previous methods (Gerber and Dubery, 2003; Zhou et al., 2020). First, a volume of 1 mL microalgae solution was prepared by centrifuging and resuspending the 1 mL microalgae sample with PBS three times. Second, a volume of 10 μL H2DCFDA stock solution was mixed with 1 mL microalgae solution. Third, the microalgae solution was darkly incubated for 1 h before detection.

The esterase is the biocatalyst used for the metabolism of cells (Agusti et al., 1998). It is an essential hydrolase enzyme that cleaves esters into acids and further assesses environmental pollutants on microalgae (Wang et al., 2016). The esterase activity of the microalgae cells was detected by fluorescein diacetate (FDA) staining (Battin, 1997). FDA (Sigma, USA) powder was dissolved in acetone to prepare the FDA stock solution at a concentration of 2.5 mM (1.041 g/L), and the stock solution was stored at −20 °C. The FDA stock solution (10 μL) was added to 990 μL microalgae sample, the sample was incubated in darkness at 25 °C for 8 min and then detected by channel FL1 of FCM.

Photosynthetic activity can characterize the intensity of photosynthesis in microalgae. The photosynthetic activity of microalgae cells was expressed as effective quantum yield (Y, Fv/Fm) (Wu et al., 2019; Li et al., 2020a), which can be detected using a phytoplankton pulse-amplitude-modulated fluorometer (PHYTO-PAM, Heinz Walz GmbH, Germany) according to a previous paper (Tao et al., 2013).

2.4. Data analysis

FCM data were analyzed with either dot plots or histogram plots based on previous analysis methods (Tao et al., 2013; Tao et al., 2010; Zhou et al., 2020). The data from dot plots were used to measure cell density and membrane integrity. Total cell density, intact cell density, and percentage of cells with membrane damage (P md) were measured through FCM and determined using Eqs. (1), (2), (3), according to previous studies (Tao et al., 2010; Zhou et al., 2020; Tao et al., 2013).

| (1) |

| (2) |

| (3) |

where C 0 is the initial cell density, C t is the cell density at a certain time t, μ (d−1) is the specific growth rate, C intact is the intact cell density, and C dead is the dead cell density.

The data of measured fluorescence intensity from histogram plots were used to assess variations in ROS and esterase activity of microalgae cells exposed to NaClO treatments, according to a previous analysis method on ROS (Zhou et al., 2020), and esterase activity (Yu et al., 2007). The relative fluorescence intensity (R) is the ratio of the mean fluorescence intensity of the treatment group to the mean fluorescence intensity of the control group, which are expressed as R(ROS) in Fig. 4, and R(esterase activity) in Fig. 5, respectively.

| (4) |

Fig. 4.

The ROS mean value relative to control (R(ROS)) of two microalgae species with different dilution rates (0, 1/50000, 1/10000, 1/5000, 1/1000, 1/500 DR) of NaClO.

Fig. 5.

The esterase activity mean value relative to control (R(esterase activity)) of two microalgae species with different dilution rates (0, 1/50000, 1/10000, 1/5000, 1/1000, 1/500 DR) of NaClO.

The effect of NaClO treatment on microalgae cells was estimated by the inhibition percentage of the average specific growth rate (Ir), which was defined by Eq. (4) (OECD, 2006; Tao et al., 2010), where Ir indicates percent inhibition in average specific growth rate μ, μ c is the value for average specific growth rate in the control group (d−1), and μ T is the value for average specific growth rate in the treated group (d−1).

The relationships between the CT values of NaClO and microalgal cell membrane damage were assessed as the time integration over the concentration for estimating the required dosage of disinfectant (Dow et al., 2006). For the exposure of NaClO, CT-value = C × T, C is the initial concentration of free chlorine, mg/L, and T is the exposure time (h). The data obtained from the three initial NaClO dosages, including 1/5000, 1/10000, and 1/50000 DR, were chosen to compare the differences between the two microalgae species and culture conditions.

For the comparison of photosynthetic activity at the same dosage of NaClO, the inhibition effects (Ei) of NaClO on photosynthesis activity were calculated from Eq. (5), following the previous analysis method (Tao et al., 2013). As shown below, in which i is the dosage of NaClO, two sensitive dosages were chosen for each microalgae species (1/50000 and 1/10000 DR for M. aeruginosa, 1/10000 and 1/5000 DR for C. vulgaris); Y and Y 0 were the measured effective quantum yield (Y) of the treated and control groups, respectively.

| (5) |

2.5. Statistical analysis

All treatments were conducted in triplicate. The data were processed and analyzed using Origin Pro 8 software (OriginLab, USA). Data are presented as an average value with standard deviation (mean ± SD). Differences between groups were analyzed using MATLAB software through one-way ANOVA, where p < 0.05 were considered significant.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Growth suppression and cell vitality under solo- and co-culture condition

3.1.1. Total cell density and intact cell density

For M. aeruginosa in solo-culture, shown in Fig. 1 -A & D, the dosage of NaClO at 1/50000 DR and above induced marked growth suppression effects. Moreover, doses of NaClO at 1/5000 DR and above resulted in significant cell density reduction within 10 min, indicating that immediate cell lysis occurred. In contrast, with a dose of NaClO at 1/10000 DR, cell lysis was moderate until no cell was detected after 12 h. The inhibition effect on algal cells at 1/50000 DR only lasted for less than 1 d, after which the regrowth of intact cell density was observed.

Fig. 1.

The total (A, B, C) and intact (D, E, F) cell density of two microalgae species (M. aeruginosa in A, D, C(a), F(a); C. vulgaris in B, D, C (b), F (b)) with different dilution rates (0, 1/50000, 1/10000, 1/5000, 1/1000, 1/500 DR) of NaClO, where A, B, D, E were under solo-cultivation, C, F were under co-cultivation.

For C. vulgaris in solo-culture, shown in Fig. 1-B & E, the chlorine dosage required for causing growth suppression effects rose to NaClO at 1/10000 DR and above, significantly higher than that of M. aeruginosa. The total cell density of C. vulgaris experienced a re-growing stage after 4 h when exposed to NaClO at 1/10000 DR, while cell lysis was observed within 12 h at 1/5000 DR and above. The regrowth of intact cell density at 1/10000 DR after 1 d indicated the termination of growth inhibition by NaClO. The results indicated that C. vulgaris was more resistant to NaClO than M. aeruginosa when cultivated individually.

A similar difference in algal sensitivity upon NaClO was found in co-culture samples, as shown in Fig. 1-C, F. Furthermore, the sensitivity of M. aeruginosa to NaClO was significantly enhanced when co-cultured with C. vulgaris. For example, intact cell density in M. aeruginosa hardly regrew at 1/50000 DR compared with solo-culture. However, the resistance of C. vulgaris to NaClO was remarkably increased as its total cell density loss was less than 30% after 7-day co-cultivation, significantly lower than the complete loss within 12 h of solo-cultivation. Furthermore, as summarized in Table 1 , the regrowth time of M. aeruginosa at 1/10000 DR was twice that of C. vulgaris, and six times longer than that of M. aeruginosa at 1/5000 DR. Moreover, M. aeruginosa never recovered to the initial concentration upon NaClO at 1/10000 DR or above, but C. vulgaris rapidly recovered within several hours.

Table 1.

Regrowth time and recover time from total cell density of M. aeruginosa and C. vulgaris under solo- and co-culture at sensitive dilution rates.

| Treatment | Dilution rate | Species | Regrowth time | Time of recover to the initial concentration |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Solo-culture | 1/50000 | M. aeruginosa | 1 d | 4 d |

| C. vulgaris | 4 h | 8 h | ||

| 1/10000 | M. aeruginosa | NA | NA | |

| C. vulgaris | 4 h | 4 d | ||

| 1/5000 | M. aeruginosa | NA | NA | |

| C. vulgaris | NA | NA | ||

| Co-culture | 1/50000 | M. aeruginosa | 1 h | 1 h |

| C. vulgaris | 1 h | 1 h | ||

| 1/10000 | M. aeruginosa | 8 h | NA | |

| C. vulgaris | 4 h | 1 d | ||

| 1/5000 | M. aeruginosa | 1 d | NA | |

| C. vulgaris | 4 h | 4 d |

(NA: not applicable).

The intact cell density and density of cells with integrated cellular membranes showed similar tendencies but significantly lower values compared to the total cell density, indicating that the inhibitory effects on microalgae cells upon NaClO at the sensitive dosages (1/50000 DR in M. aeruginosa and 1/10000 DR in C. vulgaris) led to cell death without rapid lysis. Regardless of the dilution rate, the regrowth time of M. aeruginosa appeared marked later than C. vulgaris, and the time required to recover to the initial density of M. aeruginosa was significantly longer than that of C. vulgaris. Analysis of the surface properties of the two microalgae species showed that M. aeruginosa has a lower hydrophobic character and a greater number of functional groups than C. vulgaris, especially carboxyl groups (Hadjoudja et al., 2010). Thus, M. aeruginosa was more sensitive to NaClO than C. vulgaris and resulted in more severe damage to M. aeruginosa cells under co-cultivation.

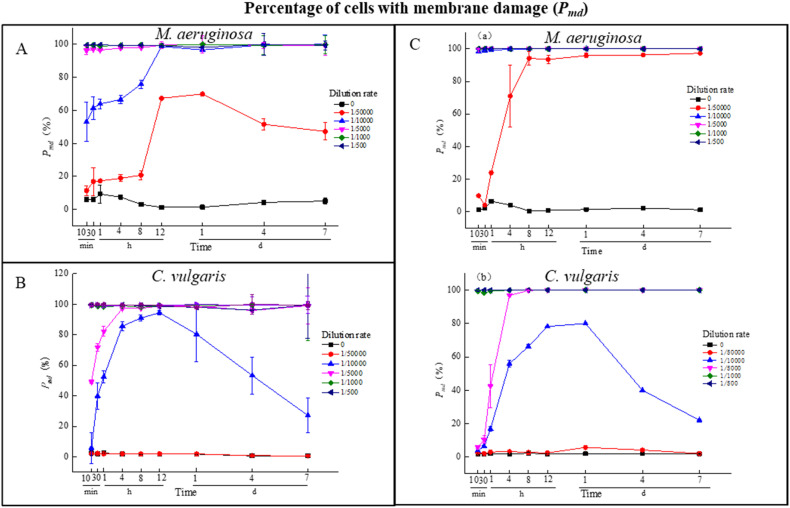

3.1.2. Membrane integrity change

The variations in cellular membrane integrity of microalgae cells upon NaClO are indicated by P md, as shown in Fig. 2 , and the regrowth time and recovery time are listed in Table 2 . The rapid elevation of P md values confirmed the lethal effects of chlorination on both M. aeruginosa and C. vulgaris. Specifically, regardless of the solo- or co-culture condition, the sensitivity of M. aeruginosa cells to NaClO was significantly higher than that of C. vulgaris exposed to the same NaClO dosage. The time for P md values reaching 20% and above of M. aeruginosa were shorter than those of C. vulgaris, as well as the peak value of P md under solo-cultivation. Moreover, damage to the M. aeruginosa cell membrane tended to be more severe under co-culture conditions, in which P md values under co-culture increased faster and achieved higher peak values than that in the solo-culture treatment at a sensitive NaClO dosage (1/50000 DR, 1/10000 DR). However, the peak values of P md for C. vulgaris under solo-culture were lower than those of co-culture at 1/10000 DR, and the time for reaching the peak was prolonged at 1/10000 DR and 1/5000 DR, suggesting that the damage to the C. vulgaris cell membrane was alleviated under the co-culture condition.

Fig. 2.

The percentage of cells with membrane damage (Pmd) under solo-cultivation (A, B) and co-cultivation (C) with different dilution rates (0, 1/50000, 1/10000, 1/5000, 1/1000, 1/500 DR) of NaClO.

Table 2.

Time for Pmd reached 20% and above, the peak value of Pmd and its time point of M. aeruginosa and C. vulgaris under solo- and co-culture at sensitive dilution rates (1/50000 DR, 1/10000 DR, 1/5000 DR).

| Treatment | Dilution rate | Species | Time for Pmd reached 20% and above | Peak value and its time point |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Solo-culture | 1/50000 | M. aeruginosa | 8 h | 69.9%, 1 d |

| C. vulgaris | NA | NA | ||

| 1/10000 | M. aeruginosa | 10 min | 98.7%, 12 h | |

| C. vulgaris | 30 min | 94.4%, 12 h | ||

| 1/5000 | M. aeruginosa | 10 min | 99.5%, 12 h | |

| C. vulgaris | 10 min | 97.2%, 4 h | ||

| Co-culture | 1/50000 | M. aeruginosa | 1 h | 24.0%, 1 h |

| C. vulgaris | NA | 5.8%, 1 d | ||

| 1/10000 | M. aeruginosa | 10 min | 100%, 8 h | |

| C. vulgaris | 4 h | 80%, 1 d | ||

| 1/5000 | M. aeruginosa | 10 min | 100%, 30 min | |

| C. vulgaris | 1 h | 99.8%, 8 h |

(NA: Not applicable).

Chlorine has been known to effectively inactivate microalgae by penetrating cells, oxidizing pigments, and leading to programmed death and further cell lysis (Dong et al., 2021). The present study indicated that chlorination at ultralow doses (1/10000 DR to 1/500 DR) caused striking suppression effects on the growth of M. aeruginosa and C. vulgaris, even on membrane permeability. NaClO has exhibits a rapid damaging effect on algal cells at high doses, according to Han's speculation that C C double bonds in the membrane can be attacked by Cl+ coming from NaClO (Han et al., 2016), which may cause membrane damage in 10 min. The results of cell density and membrane integrity indicated that a relatively higher dosage of NaClO (higher than 1/1000 DR) within 10 min can cause severe membrane breakage and cell lysis, and few intact cells could be detected. However, a lower dosage of NaClO (lower than 1/5000 DR) may require more time to induce damage through physiological processes. In other words, relatively higher dosage (above 1 mg/L) of free chlorine usually causes cell lysis within 20 min (Li et al., 2020b), but ultralow-dose free chlorine in the present study still presented suppression results for days without immediate cell lysis. Therefore, based on the different sensitivities of growth suppression and membrane integrity under solo-culture and co-culture, the inhibitory effects of discharged residual free chlorine diluted into a broader area may cause a continuous change in phytoplankton, and further cause potential ecological problems.

3.2. Physiological activity variation

3.2.1. Inhibition on photosynthetic activity

Variations in photosynthetic activity of M. aeruginosa cells exposed to NaClO are shown in Fig. 3 . As shown in Fig. 3-A, when M. aeruginosa was solo-cultured, the dosage of NaClO at 1/10000 DR resulted in rapid declines in photosynthetic activity from 0.52 to 0.17 in 30 min. At the lowest dosage of 1/50000 DR, the photosynthetic activity initially decreased and then increased after 4 d. The results indicated that the photosynthetic activity of M. aeruginosa cells was sensitive to ultralow-dose NaClO treatment. As for C. vulgaris cells under solo-culture conditions, Fig. 3-B shows that NaClO dosages at 1/10000 DR and above caused rapid reductions in photosynthetic activity, however, in markedly slower trends than that of M. aeruginosa.

Fig. 3.

Photosynthetic activity (Y) under solo-cultivation (A, B) and co-cultivation (C) with different dilution rates (0, 1/50000, 1/10000, 1/5000, 1/1000, 1/500 DR) of NaClO.

However, the variations in photosynthetic activity for both microalgae species under co-culture conditions were different. As shown in Fig. 3-C, the decrease in photosynthetic activity of M. aeruginosa cells under co-culture at 1/50000 DR was faster than that of solo-culture without a recovery trend. On the contrary, the photosynthetic activity of C. vulgaris cells at 1/10000 DR recovered after 4 days, which was never observed in solo-culture. Similar to the variations in cell density and membrane integrity, the results of photosynthetic activity confirmed that co-culture of these two microalgae species had enhanced effects on M. aeruginosa sensitivity to NaClO, while weakening inhibition effects on C. vulgaris cells.

Based on previous reports on the damage of chlorophyll-a through chlorine treatment, NaClO at 0.1–0.5 mg/L caused significant decrease of chlorophyll-a and carotenoids concentrations (Ma et al., 2011; Sathasivam et al., 2016). The photosynthetic activity of microalgae cells is strongly suppressed by an increase in the concentration of chlorine (Chuang et al., 2009; Sathasivam et al., 2016; Ma et al., 2011). In the present study, the inhibitory effect on algal photosynthetic activity was caused by ultralow dosages of NaClO, but the sustained inhibition of photosynthesis could not be ignored, which further demonstrated that the continuous growth suppression and membrane damage were related to the impact on photosynthetic activity. Meanwhile, the sensitivity difference of NaClO on photosynthesis system under solo-culture and co-culture also corresponded with the difference in cell density and membrane integrity, so that the community variation was originally caused by the damage to photosynthesis of phytoplankton, and the potential ecological risk may further affect aquatic photosynthetic organisms.

3.2.2. Variation of reactive oxygen species

Based on the analysis of R(ROS), the variations in ROS of two microalgae species in the solo-culture upon NaClO exposure are shown in Fig. 4 . The ROS increase in M. aeruginosa cells is presented as the mean value shown in Fig. 4-A. The dosages of NaClO at 1/10000 and 1/50000 DR resulted in much greater mean values of ROS, which can reach 27–28 times of control in one h or 17–14 times that of the control between 12 h and 24 h, respectively. The variations in ROS for C. vulgaris cells are shown in Fig. 4- B. NaClO at 1/10000 and 1/5000 DR led to rapid increases in ROS within 1 d, then declined to a relatively normal level, and finally regrew to a high level after 4 days. A similar regrowth trend was found at 1/50000 DR for M. aeruginosa, which also matched the decline in photosynthesis activity. The increasing ranges of ROS for C. vulgaris cells were much lower than those of M. aeruginosa. Thus, the higher intracellular ROS production in M. aeruginosa cells should contribute to the higher sensitivity of M. aeruginosa cells upon NaClO exposure.

ROS at low-to-moderate doses are essential for the life cycle of the cell, but excess abundance of ROS causes further intracellular damage, including to DNA, proteins, lipids, membranes and organelles, and by inducing other mechanisms of cell death (Yang et al., 2019; Redza-Dutordoir and Averill-Bates, 2016). The appearance of a sharp increase in ROS (1/10000 DR for M. aeruginosa, 1/5000 DR for C. vulgaris) coincided with that of the decrease in photosynthetic activity and P md raising. The results indicated that an increase in intracellular oxidative stress occurred even at ultralow NaClO concentration. Previous research has indicated that ROS production is able to be induced by 0.1 mg/L Cl2 in Closterium ehrenbergii, causing a physiological reaction in green algae (Sathasivam et al., 2016). Combined with the related photosynthetic activity results in Fig. 3-A, B, the abovementioned regrowth fluctuation of ROS at 1/50000 DR for M. aeruginosa and 1/10000 and 1/5000 DR for C. vulgaris illustrated that, after the first rapid increase in ROS caused by NaClO, these ROS declined through the recovery process, likely due to increased activity of antioxidant enzymes such as superoxide dismutase (SOD) and catalase (CAT) which lower levels of ROS (Park et al., 2009). Meanwhile, ROS are known to damage the D1 and D2 proteins of photosystem II, causing photoinhibition and further decrease in effective quantum yield (Y) as D1 and D2 are susceptible to oxidative modification by ROS (Kale et al., 2017). The damage to photosystems may further induce the production of intracellular ROS after a certain period (Pospíšil, 2012), which has the potential to cause more severe damage to cells. Thus, the increase of ROS stimulated by ultralow NaClO has the potential to be one of the primary factors of microalgae inhibition, which acts as a trigger for further damage to microalgae, particularly their capacity for photosynthesis.

3.2.3. Variation of esterase activity

Based on the analysis of R(esterase activity), variations in esterase activity of the two microalgae species upon NaClO exposure are shown in Fig. 5 . As shown in Fig. 5-A and B, for M. aeruginosa, rapid increase in esterase activity only occurred when NaClO at 1/50000 and 1/10000 DR, which remained at a relatively high level for 8 h (1/10000 DR) or 4 d (1/50000 DR). Similarly, fleeting increases (within 30 min) of esterase activity were observed when C. vulgaris cells were exposed to NaClO at 1/10000 and 1/5000 DR, which then rapidly decreased below the control group within 1 h. In contrast to M. aeruginosa, the esterase activity of C. vulgaris was less affected by NaClO.

Similar to the process of ROS, the abovementioned results suggested that M. aeruginosa and C. vulgaris cells had a rapid response to NaClO by increasing esterase activity within 10 min, but then reduced to a relatively low level compared with the blank. It has been reported that esterase activity is impacted quickly after NaClO exposure compared with chlorophyll activity, and the delayed effects or post-treatment recovery cells can be monitored through esterase activity (Ebenezer et al., 2012). Other toxic treatments on microalgae also indicated that enzyme activity declined faster than that of photosynthetic activity (Wang et al., 2016; Yu et al., 2007). Moreover, the esterase activity of M. aeruginosa was a sensitive endpoint compared with other microalgae (Yu et al., 2007), so that the esterase level of M. aeruginosa was initially higher than that of ROS at the beginning, which was opposite to the situation in C. vulgaris. Thus, the difference in physiological reaction on ultralow-dose NaClO exposure was the reason for the sensitivity among microalgae species, which is usually covered by high-dosage NaClO.

3.3. Prospects of application

3.3.1. Eco-implication based on free chlorine sensitivity

The growth suppression of M. aeruginosa and C. vulgaris upon NaClO co-culture was assessed by comparing the inhibition percentage of average specific growth rate (Ir) at three dosages (1/50000, 1/10000, and 1/5000 DR) on days 1, 4, and 7, as shown in Table 3 . The Ir of M. aeruginosa was higher than that of C. vulgaris at the same DR, especially on days 4 and 7, which reflected that the inhibition of M. aeruginosa was more serious than that of C. vulgaris. Usually, growth suppression declined with time for both microalgae species, but ultralow NaClO at 1/50000 and 1/10000 DR was still increased to inhibit M. aeruginosa after 1 d, which potentially reflected the persistent growth inhibition from physiological activity.

Table 3.

Growth inhibition of Microcystis aeruginosa and Chlorella vulgaris under co-cultivation.

| Microalgae species | NaClO dilution rate |

Ir |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 day | 4 day | 7 day | ||

| M. aeruginosa | 1/50000 | 0.5% | 70.2% | 63.3% |

| 1/10000 | 74.7% | 95.4% | 95.0% | |

| 1/5000 | 856.2% | 234.0% | 196.4% | |

| C. vulgaris | 1/50000 | 26.4% | −2.5% | 2.0% |

| 1/10000 | 6.9% | 0.0% | 7.2% | |

| 1/5000 | 280.3% | 34.5% | 20.8% | |

(Ir: the percentage of inhibition of the average specific growth rate)

As shown in Fig. 6 , the CT value of ultralow-dose NaClO on microalgal membrane damage was much lower than a previous study due to different experimental condition (Fan et al., 2014a, Fan et al., 2014b), but the scatter plots for the relationship between P md and CT value of the two algal species were discrepant. The raise of P md of both microalgae species corresponded to the increased of CT value in most cases, when CT value below 0.005 mg·h/L. However, the P md of M. aeruginosa was at least 10% higher than that of C. vulgaris at same CT value (1/50000 and 1/10000 DR), especially under co-cultured condition. The chlorine dosage at 1/5000 DR had severe damage on both microalgal membranes, all the CT value disrupted over 96% membrane of M. aeruginosa, but only CT value above 0.0008 mg·h/L had the ability to destroy over 96% membrane of C. vulgaris. This phenomenon indicated the membrane damage of M. aeruginosa from ultralow-dose of NaClO was more severe than that of C. vulgaris under the low-CT condition, and the same CT value in co-culture conditions increased cell rupture in M. aeruginosa when compared to solo-culture. Meanwhile, when the CT value above 0.005 mg·h/L, the P md of M. aeruginosa were all above 99%; however, the P md of C. vulgaris may decrease to lower than 27% in solo-culture or 22% in co-culture at 1/5000 DR. This indicates that the high CT value was effective for membrane damage on M. aeruginosa but may not have the same effect on C. vulgaris due to recovery of microalgae.

Fig. 6.

Relationship between CT-value of NaClO with Pmd, data from three NaClO dosages including 1/50000, 1/10000, 1/5000 DR.

Since discharged residual free chlorine is usually diluted and may flow to wider areas, these results support the notion of residual free chlorine-induced suppression of microalgae. The inhibitory effects on growth, and demonstrated membrane damage, resulting from ultralow-dose NaClO indicate that ultralow-dose residual free chlorine potentially triggers the inhibition algal growth for a certain period of time. Furthermore, M. aeruginosa was more sensitive to NaClO than C. vulgaris, particularly in a multispecies microalgae system, the inhibitory effects might eventually alter the ecological composition of algal species in a community. It is necessary to monitor the dominant microalgae species and associated variation of physiological change such as photosynthetic activity, as these structural variations may consequently lead to toxic microalgae death. Similar to the sensitivity of M. aeruginosa in a multispecies microalgae system to UV-C (Li et al., 2020a) and copper (Yu et al., 2007), co-cultivation under NaClO further enhances its efficacy in eliminating M. aeruginosa cells. The differences in sensitivity among species of microalgae to ultralow-dose NaClO indicates that residual free chlorine is a potential threat to the phytoplankton community, and cautions against further release of cyanophyta-related toxic components, and the possibility of chlorophyta-related algal bloom.

3.3.2. Implications based on physiological activities

To compare the differences in the three measures of physiological activity in this study, the ROS, esterase activity, and inhibitory effects on photosynthesis activity (Ei) at two selected dosages of NaClO on M. aeruginosa and C. vulgaris are illustrated in Fig. 7 . For the samples exposed to the same NaClO dosage, the relative response of ROS and esterase activity had a remarkably higher level (more than 100% at most data points) than the control. In detail, ROS can reach 10–28 times to the control group, and the ratio of esterase activity can reach 5–17 times that of the control group. However, compared with C. vulgaris, the ROS level was higher than esterase activity at most time points, the situation of M. aeruginosa was opposite, where esterase activity was higher than ROS for most time points at low levels, and ROS increased remarkably higher than esterase activity for time points at high levels. This could be because the esterase activity was a sensitive endpoint in M. aeruginosa (Wang et al., 2016; Yu et al., 2007), but less sensitive in C. vulgaris. Therefore, based on the exploration of esterase activity in natural environments (Battin, 1997; Blanchette, 2006; Agusti et al., 1998), the esterase activity of M. aeruginosa might be a feasible monitor for potential M. aeruginosa-related harmful algal death, and further indicate ecological problems.

Fig. 7.

Variations of ROS, esterase activity, and inhibition effects of NaClO on photosynthesis activity (Ei, solo-culture) in the same coordinates with selected NaClO dosages (A: 1/50000 DR for M. aeruginosa, B: 1/10000 DR for M. aeruginosa, C: 1/10000 DR for C. vulgaris, D: 1/5000 DR for C. vulgaris).

ROS can be stimulated higher than esterase, and faster than the inhibition of photosynthetic activity (Ei) (Fig. 7). High concentrations of NaClO also caused a great response to ROS (Fig. 4- D), especially the potential regrowth after days. Due to the damage to the photosynthetic system (Yang et al., 2019; Kale et al., 2017), the continuous influence of ROS activated by ultralow-dose NaClO indicated that ROS could be a warning index for potential photosystem damage and cell death in algal species, even for more photosynthetic phytoplankton.

Although photosynthetic activity declined much faster than cell density (Fig. 1 and Fig. 2), photosynthetic activity inhibition (Ei) was a delayed physiological process after ROS and esterase activity, usually inhibited after the increase of ROS or esterase (Fig. 7). Similarly, the delayed response of photosynthesis was also reported under other toxicities (Yu et al., 2007; Eigemann et al., 2013), but still responded more rapidly than cell density (Wang et al., 2016). However, the damage to photosynthetic activity has an immediate impact on algal biological activity and directly causes further change to the ecosystem. Thus, photosynthetic activity could be presented as an index of the microalgal community when evaluating the risks of residual free chlorine.

Based on the findings of the three types of physiological activity in this study, three prospective implications were suggested in terms of potential ecological risk: photosynthetic activity could be treated as an index of microalgal community risk from residual free chlorine; ROS could be a warning index for potential photosystem damage and cell death; and esterase activity could be a feasible monitor for the response of M. aeruginosa-related harmful algal death.

4. Conclusions

This study concluded that ultralow-dose NaClO had growth-inhibitory effects and physiological impacts on cyanobacterium M. aeruginosa and chlorophyta C. vulgaris, demonstrating that residual free chlorine in wastewater could be a potential trigger for ecological risk. Analysis of cell density, membrane integrity, and photosynthetic activity showed that the sensitivity of M. aeruginosa to NaClO was more significant than that of C. vulgaris under solo-culture conditions. Moreover, the sensitivity of M. aeruginosa to NaClO was enhanced when these two microalgae species were co-cultured. Based on the physiological responses to ultralow-dose NaClO in two typical microalgae species, the following practical implications were offered: photosynthetic activity may be an indicator of potential damage to the microalgae community under chlorination; ROS may act an indicator of potential photosystem damage and cell death; and esterase activity may indicate M. aeruginosa-related algal death. This study further provides theoretical support for the potential ecological impacts of undetectable residual free chlorine in wastewater.

The following are the supplementary data related to this article.

The fitting curve of free chlorine concentration with dilution rate.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Song Cao: Formal analysis, Data curation, Visualization, Writing-original draft, Writing-review, and editing. Di Zhang: Investigation, Data curation, Writing-original draft. Fei Teng: Validation, Software, Writing-review, and editing. Ran Liao: Resources, Project administration, Funding acquisition Zhonghua Cai: Conceptualization, Resources, Supervision, Project administration, Funding acquisition Yi Tao: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing-review & editing, Resources, Supervision, Project administration, Funding acquisition. Hongying Hu: Conceptualization, Resources, Supervision, Project administration, Funding acquisition.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgements

Financial support from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (52070117), Major Science and Technology Program for Water Pollution Control and Treatment (2017ZX07202002), and the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2018YFC0406300) are gratefully acknowledged.

Editor: Huu Hao Ngo

References

- Abarnou A., Miossec L. Chlorinated waters discharged to the marine environment chemistry and environmental impact. An overview. Sci. Total Environ. 1992;126(1):173–197. [Google Scholar]

- Agusti S., Satta M.P., Mura M.P., Benavent E. Dissolved esterase activity as a tracer of phytoplankton lysis: evidence of high phytoplankton lysis rates in the northwestern Mediterranean. Limnol. Oceanogr. 1998;43(8):1836–1849. [Google Scholar]

- Añasco N.C., Koyama J., Imai S., Nakamura K. Toxicity of residual chlorines from hypochlorite-treated seawater to marine amphipod Hyale barbicornis and estuarine fish Oryzias javanicus. Water Air Soil Pollut. 2008;195(1–4):129–136. [Google Scholar]

- Andersen R.A., Berges J., Harrison P.J., Watanabe M.M. Algal Culture Techniques, Elsevier Academic Press. Academic Press; London: 2005. Recipes for Freshwater and Seawater Media; pp. 429–538. [Google Scholar]

- Battin T.J. Assessment of fluorescein diacetate hydrolysis as a measure of total esterase activity in natural stream sediment biofilms. Sci. Total Environ. 1997;198(1):51–60. [Google Scholar]

- Blanchette M.L. Master Thesis of James Cook University; 2006. The Use of Esterase Activity as a Measure of Copper Toxicity in Marine Microalgae. [Google Scholar]

- Bogler A., Packman A., Furman A., Gross A., Kushmaro A., Ronen A., Dagot C., Hill C., Vaizel-Ohayon D., Morgenroth E., Bertuzzo E., Wells G., Kiperwas H.R., Horn H., Negev I., Zucker I., Bar-Or I., Moran-Gilad J., Balcazar J.L., Bibby K., Elimelech M., Weisbrod N., Nir O., Sued O., Gillor O., Alvarez P.J., Crameri S., Arnon S., Walker S., Yaron S., Nguyen T.H., Berchenko Y., Hu Y., Ronen Z., Bar-Zeev E. Rethinking wastewater risks and monitoring in light of the COVID-19 pandemic. Nat. Sustain. 2020;3:981–990. [Google Scholar]

- Chuang Y., Yang H., Lin H. Effects of a thermal discharge from a nuclear power plant on phytoplankton and periphyton in subtropical coastal waters. J. Sea Res. 2009;61(4):197–205. [Google Scholar]

- Dong F., Lin Q., Li C., He G., Deng Y. Impacts of pre-oxidation on the formation of disinfection byproducts from algal organic matter in subsequent chlor(am)ination: a review. Sci. Total Environ. 2021;754141955 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.141955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dow S.M., Barbeau B., von Gunten U., Chandrakanth M., Amy G., Hernandez M. The impact of selected water quality parameters on the inactivation of Bacillus subtilis spores by monochloramine and ozone. Water Res. 2006;40(2):373–382. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2005.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebenezer V., Nancharaiah Y.V., Venugopalan V.P. Chlorination-induced cellular damage and recovery in marine microalga, Chlorella salina. Chemosphere. 2012;89(9):1042–1047. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2012.05.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan J., Ho L., Hobson P., Daly R., Brookes J. Application of various oxidants for cyanobacteria control and cyanotoxin removal in wastewater treatment. J. Environ. Eng. 2014;140(7):04014022. [Google Scholar]

- Eigemann F., Hilt Nee Körner S., Schmitt-Jansen M. Flow cytometry as a diagnostic tool for the effects of polyphenolic allelochemicals on phytoplankton. Aquat. Bot. 2013;1045-14 [Google Scholar]

- Fan J., Hobson P., Ho L., Daly R., Brookes J. The effects of various control and water treatment processes on the membrane integrity and toxin fate of cyanobacteria. J. Hazard. Mater. 2014;264313-322 doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2013.10.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukuzaki S. Mechanisms of actions of sodium hypochlorite in cleaning and disinfection processes. Biocontrol Sci. 2006;11(4):147–157. doi: 10.4265/bio.11.147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garoma, T. & Yazdi, R. E. (2019), "Investigation of the disruption of algal biomass with chlorine", BMC Plant Biology, Vol. 19 No. 1, pp. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Gerber I.B., Dubery I.A. Fluorescence microplate assay for the detection of oxidative burst products in tobacco cell suspensions using 2′,7′-dichlorofluorescein. Methods Cell Sci. 2003;25(3–4):115–122. doi: 10.1007/s11022-004-3851-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hadjoudja S., Deluchat V., Baudu M. Cell surface characterisation of Microcystis aeruginosa and Chlorella vulgaris. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2010;342(2):293–299. doi: 10.1016/j.jcis.2009.10.078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halliwell B. Reactive species and antioxidants. Redox biology is a fundamental theme of aerobic life. Plant Physiol. 2006;141(2):312–322. doi: 10.1104/pp.106.077073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han X., Wang Z., Wang X., Zheng X., Ma J., Wu Z. “microbial responses to membrane cleaning using sodium hypochlorite in membrane bioreactors: cell integrity, key enzymes and intracellular reactive oxygen species”, Water Research. Vol. 2016;88293-300 doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2015.10.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins C.L., Davies M.J. Hypochlorite-induced damage to proteins: formation of nitrogen-centred radicals from lysine residues and their role in protein fragmentation. Biochem. J. 1998;332(3):617–625. doi: 10.1042/bj3320617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins C.L., Davies M.J. Hypochlorite-induced oxidation of proteins in plasma: formation of chloramines and nitrogen-centred radicals and their role in protein fragmentation. Biochem. J. 1999;340(2):539–548. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hazell L.J., Stocker R. Oxidation of low-density-lipoprotein with hypochlorite causes transformation of the lipoprotein into a high-uptake form for macrophages. Biochem. J. 1993;290(1):165–172. doi: 10.1042/bj2900165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hazell L.J., Vandenberg J., Stocker R. Oxidation of low-density-lipoprotein by hypochlorite causes aggregation that is mediated by modification of lysine residues rather than lipid oxidation. Biochem. J. 1994;302(1):297–304. doi: 10.1042/bj3020297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He X., Liu Y., Conklin A., Westrick J., Weavers L.K., Dionysiou D.D., Lenhart J.J., Mouser P.J., Szlag D., Walker H.W. Toxic cyanobacteria and drinking water: impacts, detection, and treatment. Harmful Algae. 2016;54174-193 doi: 10.1016/j.hal.2016.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kale R., Hebert A.E., Frankel L.K., Sallans L., Bricker T.M., Pospíšil P. Amino acid oxidation of the D1 and D2 proteins by oxygen radicals during photoinhibition of Photosystem II. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2017;114(11):2988–2993. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1618922114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kudela R.M., Lucas A.J., Hayashi K., Howard M., Mclaughlin K. “Death from below: investigation of inhibitory factors in bloom development during a wastewater effluent diversion”, Estuarine, Coastal and Shelf Science. Vol. 2017;186209-222 [Google Scholar]

- Li S., Dao G., Tao Y., Zhou J., Jiang H., Xue Y., Yu W., Yong X., Hu H. The growth suppression effects of UV-C irradiation on Microcystis aeruginosa and Chlorella vulgaris under solo-culture and co-culture conditions in reclaimed water. Sci. Total Environ. 2020;713136374 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.136374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X., Chen S., Zeng J., Song W., Yu X. Comparing the effects of chlorination on membrane integrity and toxin fate of high- and low-viability cyanobacteria. Water Res. 2020;177115769 doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2020.115769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu, J., Guo, J. & Sills, J. (2021), "Disinfection spreads antimicrobial resistance", Science, Vol. 371 No. 6528, pp. 474. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Ma Z., Gao K., Li W., Xu Z., Lin H., Zheng Y. Impacts of chlorination and heat shocks on growth, pigments and photosynthesis of Phaeodactylum tricornutum (Bacillariophyceae) J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 2011;397(2):214–219. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry-of-Ecology-and-Environment (2020), "Emergency monitoring plan for the outbreak of COVID-19", http://www.mee.gov.cn/xxgk2018/xxgk/xxgk15/202001/t20200131_761095.html;http://www.mee.gov.cn/hdjl/hfhz/202004/t20200424_776143.shtml,.

- OECD . Guideline 201: Alga, Growth Inhibition Test. OECD; Paris: 2006. Sixteenth addendum, to the OECD guidelines for the testing of chemicals. [Google Scholar]

- Pan L., Zhang X., Yang M., Han J., Jiang J., Li W., Yang B., Li X. “Effects of dechlorination conditions on the developmental toxicity of a chlorinated saline primary sewage effluent: excessive dechlorination is better than not enough”, Science of The Total Environment. Vol. 2019;692117-126 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.07.207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park S.Y., Choi E.S., Hwang J., Kim D., Ryu T.K., Lee T.K. Physiological and biochemical responses of Prorocentrum minimum to high light stress. Ocean Science Journal. 2009;44(4):199–204. [Google Scholar]

- Pospíšil P. Molecular mechanisms of production and scavenging of reactive oxygen species by photosystem II. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Bioenergetics. 2012;1817(1):218–231. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2011.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prutz W.A. Interactions of hypochlorous acid with pyrimidine nucleotides, and secondary reactions of chlorinated pyrimidines with GSH, NADH, and other substrates. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1998;349(1):183–191. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1997.0440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redza-Dutordoir M., Averill-Bates D.A. Activation of apoptosis signalling pathways by reactive oxygen species. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Molecular Cell Research. 2016;1863(12):2977–2992. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2016.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saeed S., Deb N., Varghese L., Thornhill B., Al-Shaikh I., Warren C. “Toxicity to residual chlorine: comparison of sensitivity of native Arabian Gulf species and non-native species”, International Journal of Scientific Research in Environmental Science and Toxicology. No. 2019;4(1):1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Sathasivam R., Ebenezer V., Guo R., Ki J. Physiological and biochemical responses of the freshwater green algae Closterium ehrenbergii to the common disinfectant chlorine. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2016;133501-508 doi: 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2016.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spickett C.M., Jerlich A., Panasenko O.M., Arnhold J., Pitt A.R., Stelmaszynska T., Schaur R.J. The reactions of hypochlorous acid, the reactive oxygen species produced by myeloperoxidase, with lipids. Acta Biochim. Pol. 2000;47(4):889–899. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tao Y., Zhang X., Au D.W.T., Mao X., Yuan K. The effects of sub-lethal UV-C irradiation on growth and cell integrity of cyanobacteria and green algae. Chemosphere. 2010;78(5):541–547. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2009.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tao Y., Mao X., Hu J., Mok H.O.L., Wang L., Au D.W.T., Zhu J., Zhang X. Mechanisms of photosynthetic inactivation on growth suppression of Microcystis aeruginosa under UV-C stress. Chemosphere. 2013;93(4):637–644. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2013.06.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vannoni M., Creach V., Barry J., Sheahan D. “Chlorine toxicity to Navicula pelliculosa and Achnanthes spp. in a flow-through system: the use of immobilised microalgae and variable chlorophyll fluorescence”, Aquatic Toxicology. Vol. 2018;20280-89 doi: 10.1016/j.aquatox.2018.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walter, W. G. (2005), "APHA Standard Methods for the Examination of Water and Wastewater", American Journal of Public Health & the Nations Health, Vol. 56 No. 3, pp. 387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Wang R., Hua M., Yu Y., Zhang M., Xian Q., Yin D. "Evaluating the effects of allelochemical ferulic acid on Microcystis aeruginosa by pulse-amplitude-modulated (PAM) fluorometry and flow cytometry", Chemosphere. Vol. 2016;147264-271 doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2015.12.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WEF (2020), "The Water Professional's Guide to COVID-19", Water Environment Federation, No. https://www.wef.org/news-hub/wef-news/the-water-professionals-guide-to-the-2019-novel-coronavirus/, pp.

- Wu Y., Guo P., Zhang X., Zhang Y., Xie S., Deng J. "Effect of microplastics exposure on the photosynthesis system of freshwater algae", Journal of Hazardous Materials. Vol. 2019;374219-227 doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2019.04.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang L., Mih N., Anand A., Park J.H., Tan J., Yurkovich J.T., Monk J.M., Lloyd C.J., Sandberg T.E., Seo S.W., Kim D., Sastry A.V., Phaneuf P., Gao Y., Broddrick J.T., Chen K., Heckmann D., Szubin R., Hefner Y., Feist A.M., Palsson B.O. Cellular responses to reactive oxygen species are predicted from molecular mechanisms. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2019;116(28):14368–14373. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1905039116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu Y., Kong F., Wang M., Qian L., Shi X. Determination of short-term copper toxicity in a multispecies microalgal population using flow cytometry. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2007;66(1):49–56. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2005.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zargar S., Ghosh T.K. Thermal and biocidal (chlorine) effects on select freshwater plankton. Arch. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 2007;53(2):191–197. doi: 10.1007/s00244-006-0108-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H., Dan Y., Adams C.D., Shi H., Ma Y., Eichholz T. “Effect of oxidant demand on the release and degradation of microcystin-LR from Microcystis aeruginosa during oxidation”, Chemosphere. Vol. 2017;181562-568 doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2017.04.120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Q., Gaafar M., Yang R., Ding C., Davies E.G.R., Bolton J.R., Liu Y. “Field data analysis of active chlorine-containing stormwater samples”, Journal of Environmental Management. Vol. 2018;20651-59 doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2017.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou T., Cao H., Zheng J., Teng F., Wang X., Lou K., Zhang X., Tao Y. "Suppression of water-bloom cyanobacterium Microcystis aeruginosa by algaecide hydrogen peroxide maximized through programmed cell death", Journal of Hazardous Materials. Vol. 2020;393122394 doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2020.122394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

The fitting curve of free chlorine concentration with dilution rate.