Abstract

With the acceleration of internet use, problematic social media use (PSMU) is included in our lives. When looking at the antecedents of PSMU, being young has been found to be a risk factor for PSMU. In addition to the benefits of technological advances in education and training, rapid technological developments may also result in problematic behaviors, especially among children and young. Recently, possibilities brought by technology and more widespread use of technology by young people have created a new concept, namely, cyberbullying. The present study aims to examine the effects of attachment anxiety and avoidance on PSMU and cyberbullying as with the partial mediating effects of the Dark Triad personality traits, angry rejection sensitivity, and anxious rejection sensitivity among adolescents. In general, the findings supported the proposed theoretical model. The results are discussed in terms of theoretical and practical implications along with suggestions for future research.

Keywords: Attachment, The Dark Triad personality traits, Rejection sensitivity, Problematic social media use, Cyberbullying, Adolescence

With the acceleration of internet use, new habits and new types of addictions are included in our lives. One of these addictions is called social media addiction (SMA). As with substance, alcohol, or internet addictions, SMA also has detrimental consequences (Andreassen et al, 2012). There are different definitions of SMA. Ryan and colleagues (2014) defined SMA as the inability to control social media use and disruption in academic and social functions because of social media use. According to Andreassen (2015), SMA is defined as having strong motivation or inner compulsion to use social media which results in dysfunctional consequences such as work or academic failure, decreased psychological well-being, or social relations. Detrimental consequences and failure to control social media use are distinctive features that distinguish those who score high and low on SMA (Andreassen, 2015). Although there is no consensus in the literature (Casale & Banchi, 2020), throughout the manuscript, the term "problematic social media use (PSMU)" has been used for all related terms, such as social media addiction, addictive use of social media, excessive use of social media, and problematic social media use.

Young age is among the risk factors for PSMU (Andreassen et al., 2017; Reer et al., 2021). It is important to investigate the effects of PSMU on adolescents because, in addition to being in the risk group, adolescents adopt the latest technologies more quickly, and they are vulnerable to the adverse effects of these technologies (Valkenburg & Peter, 2011). Consistently, nowadays, studies investigating the effects of PSMU among adolescents are increasing. For instance, it was found that adolescents who problematically use social media reported lower life satisfaction and higher psychological complaints than adolescents who did not use social media problematically (Boer et al., 2020). Furthermore, PSMU was found to have a significant positive effect on depressive and anxiety symptoms of adolescents (Malak et al, 2022). Yet, the number of empirical studies that examine antecedents of PSMU among adolescents is still few.

Internet is not always used for "innocent" purposes such as self-entertainment or getting information; it can also be used for malicious purposes, such as humiliating or bullying others. Bullying is defined as exposing someone to intentional negative physical, verbal, or covert actions repeatedly and over time (Olweus, 1994). Bullying is one of the most important fields of study encountered in schools today. In addition to the benefits of technological advances in education and training, rapid technological developments may also result in problematic behaviors, especially among children and adolescents (Ybarra & Mitchell, 2005). Recently, possibilities brought by and more widespread use of technology by young people created a new concept, namely, cyberbullying, which expands the concept of traditional bullying, and includes using technology for bullying others (Ayas & Horzum, 2010). It was argued that cyberbullying has more detrimental consequences than traditional bullying because victims may be bullied for seven days and 24 h via the internet (Willard, 2007).

Up to now, a few studies have focused on the antecedents of PSMU and cyberbullying among adolescents, and these studies mainly investigated the effects of the Big Five personality traits, attachment styles, self-esteem, self-regulation, body image dissatisfaction (e.g., Andreassen et al., 2017; Blackwell et al., 2017; Kircaburun et al., 2020a, 2020b; Yıldız Durak, 2020). However, we have limited knowledge regarding the antecedents of PSMU and cyberbullying, especially in the Turkish sample since a few studies have been conducted in Turkey (e.g., Peker et al., 2021; Peker & Nebioğlu Yıldız, 2021). Moreover, the fact that young age is a risk factor for both PSMU and cyberbullying indicates the importance of identifying the antecedents of PSMU and cyberbullying among adolescents.

The present study aims to examine the effects of attachment anxiety and attachment avoidance on PSMU and cyberbullying as distal outcome variables and partial mediating effects of a) the Dark Triad (DT) personality traits, b) angry rejection sensitivity (RS), and anxious RS in the links of attachment anxiety and avoidance on PSMU and cyberbullying among adolescents. Since young age is a risk factor for both PSMU and cyberbullying (Reer et al., 2021) but there are very few studies that employ adolescent samples, we aimed to contribute to the existing body of research by investigating the antecedents of PSMU and cyberbullying among adolescents. Moreover, at least to our knowledge, the current study is the first attempt to reveal the mediating effects of the DT traits and RS in the relationships of attachment anxiety and avoidance with PSMU and cyberbullying. By empirically testing the proposed mediated theoretical model, we aimed to explore the underlying personality characteristics that are partially shaped by attachment anxiety and avoidance, which, in turn, are significantly related to PSMU and cyberbullying.

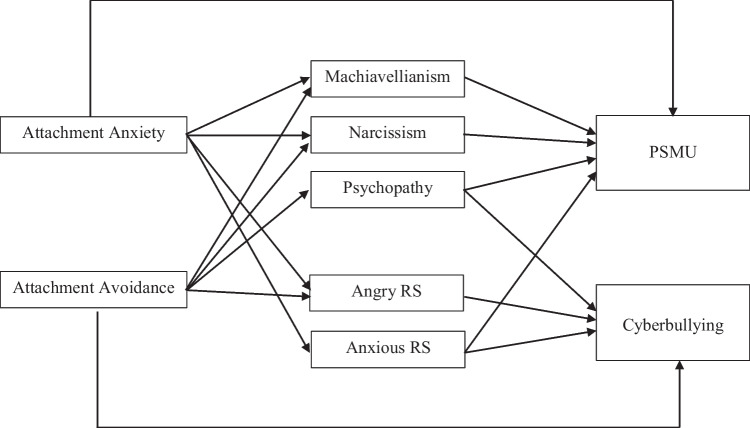

We propose that attachment anxiety is positively and directly associated with PSMU, and attachment avoidance is directly and positively associated with cyberbullying. Attachment anxiety is proposed to be positively related to both angry and anxious RS and the Machiavellianism and narcissism dimensions of the DT. On the other hand, attachment avoidance is proposed to be positively associated with all of the three dimensions of the DT and angry RS. In addition, the DT personality traits, angry RS, and anxious RS are suggested to be positively and directly associated with PSMU. Finally, narcissism and psychopathy components of the DT personality traits and angry RS are expected to be positively and directly; and anxious RS is expected to be negatively and directly linked with cyberbullying. The proposed partially mediated model is presented in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Proposed Model of the Study

Effects of attachment on PSMU and cyberbullying

Attachment is a link between caregiver and baby or the baby's desire to make a connection with the caregiver (Bowlby, 1988). According to Bowlby (1988), attachment styles depend on two dimensions: perception of the newborn regarding the sensitivity of the attachment figure to the demands and calls of the newborn (the model of others), and the perceived value of oneself in the eyes of others (the model of self). Using these two independent dimensions, Bartholomew and Horowitz (1991) created the Four Category Model and characterized four attachment styles as secure, preoccupied, dismissive, and fearful. Attachment is one of the most critical determinants of the forms of interpersonal relationships, including romantic relationships and other types of social interactions with others (Hazan & Shaver, 1987).

In studies following the works of Bartholomew and Horowitz (1991), it has been suggested that attachment dimensions would generally be more descriptive than attachment categories, and defining attachment styles with basic dimensions rather than distinct categories would be a more appropriate and valid approach (Sümer, 2006). Accordingly, Brennan and colleagues (1998) showed that attachment behaviors could be defined in two basic dimensions, which were anxiety in close relationships and avoidance of getting close to others. Attachment anxiety is characterized by hypersensitivity to rejection and abandonment in close relationships; whereas, the avoidance dimension is characterized by discomfort associated with being dependent or close to others. Individuals are classified into four attachment categories using anxiety and avoidance dimensions. The anxiety dimension was highly related to the model of self, and the avoidance dimension was highly related to the model of others in the Four Category Model of attachment (Brennan et al., 1998).

Lei and Wu (2007) argued that securely attached adolescents were less prone to internet addiction than insecurely attached adolescents. In addition, in a study with an adolescent sample, it was found that paternal and maternal attachment security had buffering effects on problematic internet use (Lan & Wang, 2020). Further empirical evidence showed that secure attachment was a protective factor for PSMU both directly (e.g., Monacis et al., 2017; Musetti et al., 2022) and indirectly via its effects on personality characteristics (Rom & Alfasi, 2014; Yaakobi & Goldenberg, 2014). Individuals with secure attachment style can form healthy face-to-face communication rather than online interactions, and their behaviors are likely to be reinforced by their actual social interactions (Weidman et al., 2012). On the other hand, anxious and avoidant attachment styles were positively associated with problematic internet use (Shin et al., 2011). Also, dismissive and fearful attachment styles were risk factors for frequent Facebook usage (Jenkins-Guarnieri et al., 2013). Besides, in a study conducted in Turkey with university students, Demircioğlu and Göncü-Köse (2021) found that fearful attachment was positively associated with PSMU both directly and indirectly via its adverse effects on relationship satisfaction.

Hart and colleagues (2015) found that attachment anxiety was positively related to Facebook engagement both directly and via its effects on the feedback-seeking component of Facebook engagement. Furthermore, attachment anxiety and PSMU were found to be positively related in multiple relational contexts (Musetti et al., 2022). Attachment anxiety is suggested to be positively associated with PSMU because individuals with high attachment anxiety are more likely to be afraid of failure in their actual face-to-face relations (Caplan, 2007) and may tend to decrease their fears with online interactions. Moreover, such individuals tend to use hyper-activating strategies (e.g., being overly dependent on others), and use social media to seek comfort and belongingness online (Worsley et al., 2018). To be more specific, individuals with high attachment anxiety may be more likely to use social networking sites to alleviate distressing emotions such as fear of rejection or loneliness and to seek comfort and sense of belonging online (Costanzo et al., 2021). Consistently, attachment anxiety is expected to be directly associated with PSMU.

Conversely, the nature of the relationship between attachment avoidance and PSMU was controversial. To illustrate, Worsley et al. (2018) did not find any significant association between attachment avoidance and PSMU; and Jenkins-Guarnieri et al. (2012) did not find any effect of attachment avoidance on Facebook use. However, Blackwell and colleagues (2017) found a positive link between attachment avoidance and PSMU; and Marci and colleagues (2021) found a positive relationship between attachment avoidance (to mother) and problematic internet use. It is argued here that attachment avoidance is not likely to be directly related to PSMU since avoidant individuals are likely to refrain from both offline and online forms of interpersonal contact; however, they still may be likely to use social media for other purposes such as following news and media. Rather than having a direct relationship with PSMU, avoidant attachment is proposed to be associated with PSMU via its effects on personality traits and the quality of interpersonal relationships. Therefore, in the light of the attachment theory and the findings mentioned above, the first hypothesis of the study is generated as follows:

Hypothesis 1: Attachment anxiety is positively and directly associated with PSMU.

Parent–child relationships affect adolescents’ psychological well-being and emotional development (e.g., Liu, 2006). Securely attached children and adolescents are more open to communication, emotionally balanced, and their relationships depend on mutual trust (Armsden & Greenberg, 1987). It was found that securely attached individuals were less frequently faced with depression, anxiety, antisocial behaviors, and delinquency than insecurely attached individuals (e.g., Steinberg, 2001). Consistently, Kerr and colleagues (2010) emphasized that emotional ties reduce juvenile crime. Securely attached individuals generally have well-developed emotional ties with others.

Previous studies showed that poor emotional bonds in family relationships were among the antecedents of cyberbullying (Ang, 2015). Furthermore, among adolescents, perceived mother acceptance was found to be a protective factor for adolescent cyberbullying (Geng et al., 2022; Qu et al., 2022). Thus, while secure attachment can be a protective factor, insecure attachment can be a risk factor for cyberbullying. Fanti and colleagues (2012) found that low parental support was an antecedent of becoming a cyberbully offender among adolescents. Consistently, Yusuf et al. (2018) found that the alienation dimension of attachment was associated with cyberbullying. Confirming these findings, a recent study conducted with adolescents found a negative association between security on parent–child attachment and cyberbullying (Li et al., 2022).

We argue that attachment anxiety is not likely to be directly related to cyberbullying since individuals who scored high on attachment anxiety may more or less likely to be perpetrators of cyberbullying to protect their actual relations. Rather than having a direct relationship with cyberbullying, attachment anxiety is proposed to be associated with cyberbullying via its effects on personality traits.

Among college students, cyberbullying was found to be related to a lack of ability to develop and maintain friendships. Cyberbullying was also positively associated with being emotionless and negatively linked with empathy (Dilmaç, 2009). There was also a negative association between insecure attachment and empathy (Mikulincer & Shaver, 2007). Consistently, we suggest that individuals with high attachment avoidance are less likely to show empathy towards others, which may lead them to perform behaviors that may hurt others (e.g., cyberbullying) easily or without hesitation. Therefore, being high on attachment avoidance may be among the antecedents of cyberbullying via its negative effects on empathy. Moreover, individuals with high attachment avoidance have a negative view of others (Sümer, 2006). Also, individuals who get high scores on attachment avoidance have low level of fear of loss (Marazziti et al., 2010). These people may not hesitate to hurt others either because they think they are highly self-sufficient or since they lack empathy. Finally, individuals with high attachment avoidance may be likely to have poor quality face-to-face relationships, which may lead them to engage in cyberbullying to retaliate against others who do not provide the social interactions they desire or those who refuse them. These characteristics may all constitute the underlying reasons for individuals who score high on attachment avoidance to engage in cyberbullying and the second hypothesis of the present study is as follows:

Hypothesis 2: Attachment avoidance is positively and directly associated with cyberbullying.

Effects of the DT personality traits on PSMU and cyberbullying

Subclinical level Machiavellianism, narcissism, and psychopathy were conceptualized as the DT personality traits by Paulhus and Williams (2002). Machiavellianism is defined as having a strong tendency to perform strategic behaviors in accordance with self-interest and being manipulative, directive, and cynical (Gunnthorsdottir et al., 2002). Machiavellians are likely to justify every path to the desired end (Braginsky, 1970). Subclinical narcissism is defined as an excessive need for admiration, an elevated sense of grandiosity, and dominance (Paulhus, 2001). A low level of empathy, excessive self-love, and the strong desire to be appreciated by others are among the main characteristics of narcissism (Paulhus & Williams, 2002). Psychopathy is characterized by lack of controlling behaviors and moral values (Arrigo & Shipley, 2001). Individuals who score high on subclinical psychopathy display anti-social behaviors; exhibit some emotions such as conscience, fear, and empathy less frequently than others; frequently seek excitement; they are manipulative and impulsive (Jonason et al., 2012).

Sensation seeking was found as a common feature of the DT personality traits (Miller et al., 2010). Considering that social media allows individuals to spread their ambitions easily, we propose that the DT personality traits and PSMU are positively associated. In the literature, narcissistic individuals were found to use social media with the purpose of self-promotion (e.g., Carpenter, 2012). On the other hand, psychopathic individuals may easily express their unadmitted behaviors via social media (Jonason & Webster, 2012).

According to the Uses and Gratification approach (Katz et al., 1974), individuals use media or other communication tools to fulfill their social and psychological needs (cognitive, affective, or personal such as the need for personal identity, escape, and self-presentation) which were determined by their personality characteristics; and, social media sites can be need gratification tools for individuals (Papacharissi & Mendelson, 2011). In other words, by social networking sites, individuals can easily satisfy several social needs such as the need for belonging, the need for self-presentation, self-expression, and social interaction and by social media, individuals may easily present real and ideal selves (Lee et al., 2015; Nadkarni & Hofmann, 2012). Therefore, social media may satisfy the needs of these individuals by offering them an online, individualized, and mostly safe environment and it may also provide them with an increase in their likelihood of gaining influence over a broad audience (Kircaburun et al., 2019).

Previous studies revealed that narcissism was positively and significantly associated with Facebook usage (Ryan & Xenos, 2011), internet addiction (Ekşi, 2012), and problematic smartphone use (Servidio et al., 2021). Additionally, adolescents' desire to be liked and PSMU were found to be positively related (Savci et al., 2021). Furthermore, psychopathy was found to be positively linked with PSMU (Demircioğlu & Göncü-Köse, 2021). Besides, Machiavellians may easily manipulate others and reinforce their self-interests using social media (Abell & Brewer, 2014). Additionally, the DT personality traits were shown to be positively related to Instagram addiction (Nikbin et al., 2022) and PSMU both directly and indirectly via its effects on emotional dysregulation among adults (Hussain et al., 2021; Tang et al., 2022) and adolescent samples (Lee et al., 2022). In light of the theoretical background and the findings mentioned above, the next hypothesis is generated as follows:

Hypothesis 3: Machiavellianism, narcissism, and psychopathy are positively and directly associated with PSMU.

Cyberbullying was found to be related to time spent online and engaging in risky online behaviors, but some personality characteristics were found as significant predictors of cyberbullying rather than risky online behaviors (Görzig & Olafsson, 2013). These characteristics are lack of self-control, high psychoticism, aggression, and lack of empathy (e.g., Doane et al., 2014). In the literature, the DT personality traits were associated with undesirable characteristics such as vengeance, anger, and aggressive humor (e.g., Giammarco & Vernon, 2014). Furthermore, distinct characteristics of the DT were positively related to aggression, bullying, and/or cyberbullying (e.g., Ang et al., 2010). Psychopathy was found to be associated with both aggression and cyber aggression among adolescents (e.g., Chabrol et al., 2009). Moreover, Peker and Nebioğlu-Yıldız (2021) found a significant association between aggressiveness and cyberbullying and stated that aggressive individuals might use online technologies to move their resentment, violent intents, and desire for vengeance from the actual world to the virtual one. Consistently, other studies showed that psychopathy was a unique predictor of cyberbullying (e.g., Goodboy & Martin, 2015).

Although all of the DT personality traits were found to be positively related to cyberbullying in a number of recent studies (Nocera and Dahlen, 2020; Safaria et al., 2020; Schade et al., 2021), we suggest that Machiavellianism and narcissism may not directly be associated with cyberbullying since, in contrast to those who are high on psychopathy, individuals with high levels of Machiavellianism or narcissism would deliberately take into account what they will lose or gain by cyberbullying and would behave accordingly. Therefore, the fourth hypothesis of the present study is generated as follows:

Hypothesis 4: Among the DT personality traits, only psychopathy is positively and directly associated with cyberbullying.

Effects of rejection sensitivity on PSMU and cyberbullying

People’s perceptions of and reactions to rejection differ. While some people perceive rejection neutrally, some people easily recognize and overreact to rejection (Özen et al., 2011). Downey and Feldman (1996) defined RS as overreacting to and being extremely sensitive to rejection cues in social relations. High RS individuals tend to expect rejection and are more sensitive to rejection situations than low RS individuals. In other words, high RS individuals discordantly overreact to small or imaginary rejection behaviors that others do not notice or need to react. These reactions were found to undermine and negatively affect high RS individuals' social relationships and personal well-being (Downey & Feldman, 1996).

People who are very sensitive to rejection experience extreme anxiety when they are rejected by others in social circumstances, and they tend to interpret ambiguous cues in interpersonal interactions as rejection (Downey & Feldman, 1996). These individuals may be more inclined to use social media as they have access to a virtual social environment where they can chat without revealing their true identities or feeling uncomfortable on social media (Demircioğlu & Göncü-Köse, 2021). To our knowledge, there were very few studies that focused on the effects of RS on PSMU. One study showed that high RS individuals' Facebook usage was significantly higher than those of low RS individuals (Farahani et al., 2011). Furthermore, Saunders and Chester (2008) found a positive relationship between RS and problematic internet use. More recently, in a study conducted in Turkey with university students, Demircioğlu and Göncü-Köse (2021) found that RS was positively associated with PSMU both directly and indirectly via its adverse effects on (romantic) relationship satisfaction. Furthermore, low RS adolescents’ internet addiction levels were lower than high RS adolescents’ internet addiction levels (Li et al., 2021), and RS was found to be an antecedent of internet addiction in a recent study (Xin et al., 2021).

Among children and adolescents, RS was defined with two dimensions: angry and anxious RS. Angry RS refers to feeling anger when faced with rejection, while anxious RS is defined as feeling anxious because of the probability of rejection. Adolescents with highly anxious RS may prefer communication over social media instead of face-to-face communication to minimize rejection possibilities. Also, since there are no factors such as tone of voice and eye contact in communication via social media, they may notice fewer rejection cues, which may reinforce high anxious RS adolescents' social media use.

Hypothesis 5: Anxious RS is positively and directly associated with PSMU.

Anxious RS is related to flight responses such as social withdrawal whereas angry RS is related to fight responses such as aggression (London et al., 2007). Hence, internalizing problems such as depression are likely to be related to anxious RS, while externalizing problems such as conduct problems are likely to be among the consequences of angry RS (Bondü & Krahé, 2015). In a study conducted by Jacobs and Harper (2013), angry RS was found to be a risk factor for aggressive behaviors. Besides, Bondü and Krahé (2015) found that angry RS was one of the unique predictors of proactive and reactive types of aggression, but anxious RS was not a predictor of aggression. Consistently, angry RS is likely to be directly and positively associated with cyberbullying which is an aggressive act. However, anxious RS was positively related to self-blaming (Zimmer-Gembeck et al., 2016), and bullying others via social media or cyberbullying is likely to increase self-blaming. That is, adolescents who score high on anxious RS may deliberately avoid cyberbullying behaviors because such acts would increase their feelings of self-blame and rejection anxiety. Therefore, contrary to angry RS, anxious RS is suggested to be negatively linked to cyberbullying.

Hypothesis 6a: Angry RS is positively and directly associated with cyberbullying.

Hypothesis 6b: Anxious RS is negatively and directly associated with cyberbullying.

Mediating effects of the DT personality traits and RS in the links of attachment with PSMU and cyberbullying

Machiavellianism was associated with dysfunctional personality, imbalanced and emotional dysfunctionality, hostile and antagonistic attitudes, and depressive symptoms (e.g., Jakobwitz & Egan, 2006). Additionally, Machiavellianism was found to be negatively related to adolescents’ parental emotional warmth (Liu et al., 2021; Yendell et al., 2022), the quality of current relationship with their parents (Tajmirriyahi et al., 2021); and positively related to insecure parental attachment (Bloxsom et al., 2021), ambivalent attachment (Amiri & Jamali, 2019), and the experience of parental rejection (Yendell et al., 2022). Consistently, individuals who score high on Machiavellianism are expected to score high on both anxious and avoidant attachment, which demonstrate overlapping characteristics mentioned above. To illustrate, Ináncsi et al. (2015) found a positive relationship between Machiavellianism and attachment avoidance. In another study, Machiavellianism was found to be positively related to both attachment anxiety and attachment avoidance (Uysal, 2016).

According to Pistole (1995), “different forms of insecure attachment, characterized by varying degrees of avoidance and/or anxiety may actually have the same purpose in that they are manifestations of defense mechanism employed by individuals high in narcissistic vulnerability” (Smolewska & Dion, 2005, p. 59). In addition, insecure attachment in children and exhibiting remarkable and self-centered attitudes are thought to be results of problematic early parent–child interactions with features such as low empathy and carelessness (Watson et al., 1993). Consistently, adolescents’ narcissism levels were found to be positively related to the experience of parental rejection by both parents (Yendell et al., 2022). Therefore, it was suggested that both attachment anxiety and attachment avoidance may be among the predictors of narcissism.

One of the most important predictors of psychopathy is lack of affective attachment to a person (Meloy, 1992). Securely attached individuals were found to display lower levels of psychopathic features than individuals who scored high on avoidant attachment (Jonason et al., 2014). Consistently, we expect that attachment avoidance is positively related to psychopathy. On the contrary, there were inconsistent findings regarding the association between attachment anxiety and psychopathy. Some studies revealed that attachment anxiety was negatively associated with psychopathy (Conradi et al., 2015) while others found that attachment anxiety was positively linked to psychopathy (Mack et al., 2011). Individuals high on attachment anxiety may be less likely to have psychopathic behaviors because of their fragile self-esteem, and psychopathic traits such as fearlessness may not be found among individuals who score high on attachment anxiety. However, such individuals are likely to have a negative view of self and they may have difficulty in controlling their feelings in certain situations and they may also show psychopathic traits in various contexts. Therefore, in the current study the link between attachment anxiety and psychopathy is expected to be insignificant since it was thought that this relation may be moderated by other factors.

Downey and Feldman (1996) claimed resemblance in RS and Bowlby’s working models. It has been suggested that RS depicts some of the basic cognitive and emotional subprocesses involved in attachment (Pietrzak et al., 2005). Compared to insecure working models, RS was found to be more specific and precise. Attachment is about intrinsic representations, whereas RS is about assessment of context and response strategies of individuals. In addition, it was found that rejection of children’s needs by parents were positively associated with children’s RS levels (e.g., Downey & Feldman, 1996). Also, it was found that attachment styles were significantly related to RS (e.g., Erozkan & Komur, 2006). To illustrate, RS was found to be negatively linked with secure attachment and positively linked with fearful, dismissive and preoccupied attachment styles among Turkish university students (Erozkan, 2009). Furthermore, in a study which investigated the link between attachment and RS using with two-dimensional attachment, attachment anxiety was found to be positively correlated with RS (Khoshkam et al., 2012; Sato et al., 2020). Additionally, both anxious and avoidant attachment were found to be positively related to RS in another recent study (Set, 2019).

In a study in which RS was used as a latent variable comprised of adolescents’ angry RS, anxious RS, and rejection expectation scores, RS was found to be positively related to mother-adolescent parentification (Goldner et al., 2019). However, to our knowledge, no empirical study has investigated the effects of attachment anxiety and attachment avoidance on angry RS and anxious RS separately up to now. We suggest that adolescents who score high on attachment anxiety may get high scores on both angry RS and anxious RS because attachment anxiety was also characterized as hypersensitivity about rejection and abandonment in close relationships. On the other hand, adolescents with high attachment avoidance may express their feelings with angry RS because these individuals whose model of self is positive and model of others is negative, and who are not eager to frequently form close relationships are likely to feel anger (rather than anxiety) when they are faced or threatened with rejection in relatively rare situations that they demand interaction with others.

As explained above, attachment anxiety and avoidance are suggested to be both directly and indirectly associated with PSMU and cyberbullying via their effects on the DT personality traits and RS. To be more precise, in addition to the direct effect of attachment anxiety on PSMU, individuals with high attachment anxiety are suggested to be more likely to show narcissistic features which may be antecedents of PSMU. Although a direct relationship is not expected between attachment avoidance and PSMU, we suggest that individuals with avoidant attachment would have more Machiavellian, psychopathic, and narcissistic features and their PSMU and cyberbullying levels may be high partially because of these traits. In addition, adolescents with high attachment anxiety may get high scores on both angry and anxious RS which may increase these individuals’ PSMU and cyberbullying levels. Furthermore, individuals with high attachment avoidance are suggested to get high scores on angry RS which is expected to increase adolescents’ PSMU and cyberbullying levels. Therefore, the final set of hypotheses describing the mediated relationships is generated as follows:

Hypothesis 7a: Machiavellianism and narcissism mediate the relationship between attachment anxiety and PSMU.

Hypothesis 7b: Machiavellianism, narcissism, and psychopathy mediate the relationship between attachment avoidance and PSMU.

Hypothesis 8: Anxious RS mediates the relationship between attachment anxiety and PSMU.

Hypothesis 9: Psychopathy mediates the relationship between attachment avoidance and cyberbullying.

Hypothesis 10a: Angry and anxious RS mediate the relationship between attachment anxiety and cyberbullying.

Hypothesis 10b: Angry RS mediates the relationship between attachment avoidance and cyberbullying.

In summary, we aimed to contribute to the relevant literature by examining the important antecedents of PSMU and cyberbullying among adolescents. PSMU and cyberbullying are highly prevalent among high school students, and they are both negatively associated with personal and academic development (Peker & Nebioğlu Yıldız, 2021). Previous studies consistently showed that attachment anxiety and avoidance were among the main antecedents which were positively associated with PSMU and cyberbullying. However, the present research may contribute to the theoretical knowledge by exploring the underlying personality characteristics (i.e., the DT personality traits, anxious RS, and angry RS) involved in the relationships of attachment anxiety and avoidance with PSMU and cyberbullying. Moreover, the study findings are expected to guide practitioners in their attempts to develop prevention and intervention strategies for PSMU and cyberbullying.

Method

Participants and the procedure

The data were collected from high school students enrolled in four different high schools in Ankara, Turkey.1 By convenience sampling method, four different high schools were selected for data collection according to their education types. The schools represented Anatolian high school, regular high school, and technical and industrial vocational high school. One high school was selected as a representative of Anatolian high schools. Two high schools were selected as representatives of regular high schools, and one high school was selected as a representative of technical and industrial vocational high schools. The principals of the schools randomly assigned the classes for data collection. Participants were given the paper–pencil surveys distributed by one of the researchers, and they were allowed to fill out the questionnaires during lectures by their teachers.

The eligibility criterion for participation was being a high school student (attending at 9th-12th grade). All the students in the assigned classes volunteered for participation resulting in 100% participation rate. Participants were given the paper–pencil surveys distributed by one of the researchers and they were allowed to fill out the questionnaires during lectures by their teachers. The number of participants was 547. Of the 547 participants, 273 were girls (49.9%), 265 were boys (48.4%), and 9 (1.6%) did not specify gender. The average age of the participants was 15.8 (SD = 1.1).

Of the 547 participants, 137 (25%) participants were in the 9th grade, 181 (33.1%) were in the 10th grade, 113 (20.7%) were in the 11th grade, 100 (18.3%) were in the 12th grade, and 16 (2.9%) students did not indicate the class they were attending. Two hundred and eleven (38.6%) of the participants were Anatolian high school students, 270 (49.3%) were regular high school students, and 62 of them (11.3%) were technical and industrial vocational high school students. Four participants (0.7%) did not specify their school.

Out of 547 participants, 388 (70.9%) used Instagram as the most used social media platform, 25 (4.6%) of them stated that they mostly used Twitter, 15 (2.7%) of them mostly used Facebook, 115 (21%) of them stated that they used other social media platforms, and 4 (0.7%) people did not answer this question. In addition, 227 of the participants (41.5%) used social media to interact with their friends, 42 (7.7%) used social media to follow celebrities they are interested in, 39 (7.1%) used it for activity tracking, 25 (4.6%) used it for photo sharing, 20 (3.7%) used it for information sharing, 180 (32.9%) stated that they used it for other purposes and 6 (1.1%) people did not answer this question.2

This study was approved by Cankaya University Social Sciences and Humanities Scientific Research and Publication Ethics Committee. In addition, approval for the study was obtained from the Republic of Turkey Ministry of National Education since the participants were high-school students. Informed consents of all the participants were received via a form detailing the content of the study, and the participants' rights to withdraw from the study at any time. The survey package included measures of attachment styles, the DT personality traits, RS, social media addiction and cyberbullying, and also a demographic section in which information about age, gender, school, class, socioeconomic status, and parental education levels were asked.

Measures

Social media addiction

41-item social media addiction scale developed by Tutgun-Ünal and Deniz (2015) in Turkish was used to measure participants’ PSMU levels. The scale consists of four dimensions which are preoccupation, mood modification, relapse, and conflict/problems. A sample item is “I think about going online for social media intensively when I am not connected to the internet” (preoccupation subscale). Participants reported their answers using a 5-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (never) to 5 (always). In the current study, the Cronbach’s alpha of the overall scale was found as 0.95.

Cyberbullying

The European Cyberbullying Intervention Project Questionnaire, which was developed by Del Rey and colleagues (2015) in English was used to measure high school students’ cyberbullying levels. The scale consists of 22 items and two dimensions which are cyber-aggression and cyber-victimization. In the present study, only cyber-aggression dimension was used. Cyber-aggression subscale was translated into Turkish by Demircioğlu (2020). Unidimensional subscale consists of 11 items and participants report their answers using a 5-point Likert-type scale ranging from 0 (never more) to 4 (more times a week). A sample item of the scale is “I said nasty things about someone to other people either online or through text messages”. In the present study, the internal consistency reliability score of the subscale was found to be 0.88.

Experiences in close relationships

Attachment anxiety and attachment avoidance were assessed by using Experiences in Close Relationships — Revised — General Short Form (ECR-R-GSF) developed by Wilkinson (2011) in English and translated to Turkish by Demircioğlu (2020). The scale was used for adolescents, and it was the modified version of Experiences in Close Relationships — Revised (ECR-R; Fraley et al., 2000) which is used for adults. ECR-R-GSF consists of 20 items selected from ECR-R that can be applied to adolescents. Sample items are “I prefer not to show others how I feel deep down” (avoidance) and “I often worry that other people don’t care as much about me as I care about them” (anxiety). Participants reported their answers using a 7-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (not at all like me) to 7 (very much like me). In the current study, Cronbach’s alphas of the avoidance and anxiety subscales were 0.75 and 0.83, respectively.

Short Dark Triad-Turkish (SD3-T)

The DT personality traits were assessed by 27-item Short Dark Triad (SD3) developed by Jones and Paulhus (2014) in English and adapted to Turkish by Özsoy and colleagues (2017). A sample item of 9-item Machiavellianism subscale is “It’s not wise to tell your secrets”. A sample item of 9-item narcissism subscale is “I have been compared to famous people”. A sample item of 9-item psychopathy subscale is “People who mess with me always regret it.”. Participants reported their answers using a 5-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). The Cronbach’s alphas of Machiavellianism, narcissism, and psychopathy subscales were found as 0.77, 0.65, and 0.74, respectively.

Adolescent rejection sensitivity

RS was measured by Children’s Rejection Sensitivity Questionnaire (CRSQ; Downey et al., 1998) which was developed in English and translated to Turkish by Demircioğlu (2020). The scale consists of two dimensions which are nervous/anxious expectation and angry expectation and 12 hypothetical vignettes which include scenarios about peers or teachers. At the end of each vignette, participants respond to three questions. In the first question, participants rate the situation in terms of their anxiety level by using 7-point Likert Scale ranging from 1 (not nervous) to 7 (very, very nervous). In the second question, participants rate the situation in terms of their anger level by using 7-point Likert Scale ranging from 1 (not mad) to 7 (very, very mad). In the third question, participants rated the likelihood of a rejection response in each vignette using with 6-point Likert Scale ranging from 1 (yes!!) to 6 (no!!). In order to determine the total anxious RS score of the adolescents, anxiety level scores of each item is multiplied by the likelihood of rejection levels and the mean scores of 12 items are calculated. To determine the total angry RS score of the adolescents, anger levels of each item is multiplied by the likelihood of rejection levels and then, the mean scores of 12 items are calculated. In the current study, internal consistency reliability of the angry RS and anxious RS dimensions were found as 0.82 and 0.81, respectively.

Statistical analysis

Out of 595 participants, 18 responded to all questionnaire items with the same scores. In addition, 17 participants did not fill out at least one of the scales. Therefore, 35 participants were eliminated at the beginning of the data analysis. With 560 participants, the data were screened for missing scores. There were five scales in the questionnaire, which included 135 items. Out of 75,600 data points, there were 351 missing data points (0.45%), excluding the demographic variables. According to Tabachnick and Fidell (2007), replacement method can be used to handle the missing values if the missing data points ratio over the total data points is smaller than 5%. Therefore, to keep the sample size as large as possible, the mean replacement method was employed. After replacing the mean values, multivariate outliers were examined by using Mahalanobis distance analysis. Mahalanobis distance analysis revealed that 13 participants were multivariate outliers and excluded from the data set. Therefore, the final sample included 547 participants. Univariate distributions were checked for skewness and kurtosis scores in order to check the normality assumptions and were found to fall within acceptable ranges (between 2 and + 2).

After data screening and data cleaning processes, descriptive statistics and the Cronbach’s alpha reliabilities of the measures were calculated before calculating the scale scores. Mean values, standard deviations of the scores, and the correlation matrix were utilized by SPSS 26.0. For hypothesis testing, Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) technique was used. SEM analysis was conducted by using AMOS 20.0 (Arbuckle, 2013).

Results

Means, standard deviations of the scores and the correlation matrix are presented in Table 1. Hypothesized mediated relationships were tested by using AMOS in which Structural Equation Modeling (SEM). The error terms of the DT personality traits, dimensions of attachment, dimensions of RS and the error term between PSMU and cyberbullying were allowed to correlate in the model testing. The proposed theoretical model provided good fit to the data (χ2 (N = 547, df = 10) = 16.73, p = 0.08, TLI = 0.98, CFI = 0.99, NFI = 0.99, RMSEA = 0.04 [ 90% CI: 0.00, 0.06]).

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics, Intercorrelations, and Internal Consistencies of the Study Variables (N = 547)

| Variable | Mean | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Gender | - | - | - | ||||||||||

| 2. Age | 15.80 | 1.10 | .00 | - | |||||||||

| 3. PSMU | 2.24 | .71 | -.11** | -.06 | (.95) | ||||||||

| 4. Cyberbullying | 0.62 | .73 | .21** | .04 | .23** | (.88) | |||||||

| 5. Attachment Anxiety | 3.70 | 1.14 | -.16** | -.12** | .32** | .05 | (.83) | ||||||

| 6. Attachment Avoidance | 4.28 | 1.04 | -.11* | .04 | .05 | .00 | -.01 | (.75) | |||||

| 7. Machiavellianism | 3.23 | .80 | .11** | .04 | .16** | .21** | .10* | .19** | (.77) | ||||

| 8. Narcissism | 3.00 | .69 | .04 | -.03 | .12** | .20** | -.02 | -.07 | .37** | (.65) | |||

| 9. Psychopathy | 2.67 | .81 | .12** | .05 | .32** | .41** | .06 | .17** | .53** | .34** | (.74) | ||

| 10. Anxious RS | 7.87 | 3.56 | -.05 | -.05 | .25** | -.04 | .40** | .05 | .06 | -.04 | .02 | (.81) | |

| 11. Angry RS | 6.49 | 3.10 | .12** | -.04 | .26** | .15** | .28** | .08 | .14** | .12** | .24** | .73** | (.82) |

* p < .05. ** p < .01. Numbers on the Diagonal are Cronbach’s Alpha coefficients. Gender was coded as “1” for females and “2” for males. Correlations of study variables with gender were point-biserial

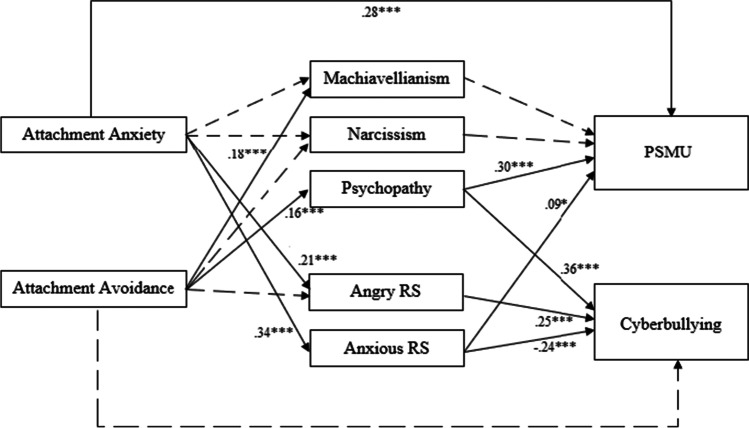

The analyses of the standardized estimates of the paths revealed that Hypothesis 1, which suggested a positive association between attachment anxiety and PSMU was supported (β = 0.28, p < 0.001). Contrary to Hypothesis 2 which suggested a positive link between attachment avoidance and cyberbullying, the association between attachment avoidance and cyberbullying was insignificant (Table 2). Partially supporting Hypothesis 3, which proposed positive links from the DT personality traits to PSMU, and supporting Hypothesis 4, which proposed positive links from psychopathy to cyberbullying, the paths from psychopathy to PSMU (β = 0.30, p < 0.001) and psychopathy to cyberbullying were significant (β = 0.36, p < 0.001).

Table 2.

Standardized and Unstandardized Regression Weights and Standard Errors of the Tested Paths between the Study Variables

| Unstandardized Estimates | S.E | Standardized Estimates | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Attachment Anxiety ➔ Machiavellianism | .05 | .03 | .07 |

| Attachment Anxiety ➔ Narcissism | -.03 | .02 | -.6 |

| Attachment Anxiety ➔ Angry RS | .66 | .13 | .21*** |

| Attachment Anxiety ➔ Anxious RS | 1.2 | .14 | .34*** |

| Attachment Anxiety ➔ PSMU | .17 | .02 | .28*** |

| Attachment Avoidance ➔ Machiavellianism | .14 | .03 | .18*** |

| Attachment Avoidance ➔ Narcissism | -.05 | .03 | -.09 |

| Attachment Avoidance ➔Psychopathy | .12 | .03 | .16*** |

| Attachment Avoidance ➔ Angry RS | .10 | .10 | .03 |

| Attachment Avoidance ➔ Cyberbullying | -.04 | .03 | -.05 |

| Machiavellianism ➔ PSMU | -.02 | .04 | -.02 |

| Narcissism ➔ PSMU | .04 | .04 | .04 |

| Psychopathy ➔ PSMU | .27 | .04 | .30*** |

| Psychopathy ➔ Cyberbullying | .34 | .04 | .36*** |

| Angry RS ➔ Cyberbullying | .05 | .01 | .25** |

| Anxious RS ➔ PSMU | .02 | .01 | .09* |

| Anxious RS ➔ Cyberbullying | -.04 | .01 | -.24*** |

* p < .05; ** p < .01; ***p < .001

Hypothesis 5 was supported since anxious RS was significantly associated with PSMU (β = 0.09, p < 0.05). Hypothesis 6, which suggested that angry RS would be positively associated with cyberbullying (β = 0.25, p < 0.01); and anxious RS would be negatively associated with cyberbullying was fully supported by the data (β = -0.24, p < 0.001).

Hypothesis 7a was rejected since neither attachment anxiety was significantly associated with Machiavellianism and narcissism nor Machiavellianism and narcissism were significantly associated with PSMU. In other words, Machiavellianism and narcissism did not mediate the link between attachment anxiety and PSMU. Partially supporting Hypothesis 7b which proposed that Machiavellianism, narcissism, and psychopathy would mediate the positive link between attachment avoidance and PSMU, only psychopathy mediated the link between attachment avoidance and PSMU (Indirect effect = 0.04, LLCI = 0.01, ULCI = 0.06). More specifically, attachment avoidance was significantly positively associated with psychopathy (β = 0.16, p < 0.01), which, in turn, was significantly and positively related to PSMU (β = 0.30, p < 0.001). On the contrary, although there was a significant positive association between attachment avoidance and Machiavellianism (β = 0.18, p < 0.001), the link between Machiavellianism and PSMU was not significant.

Since anxious RS was significantly associated with PSMU (β = 0.09, p < 0.05), Hypothesis 8 which suggested that anxious RS would mediate the link between attachment anxiety and PSMU was fully supported (Indirect effect = 0.06, LLCI = 0.03, ULCI = 0.09). Fully supporting Hypothesis 9 (Indirect effect = 0.07, LLCI = 0.04, ULCI = 0.10), attachment avoidance was positively associated with psychopathy (β = 0.16, p < 0.01), which in turn, was positively associated with cyberbullying (β = 0.36, p < 0.001).

Attachment anxiety was positively associated with both angry and anxious RS (β = 0.21, p < 0.001; β = 0.34, p < 0.001), and angry RS was positively, anxious RS was negatively associated cyberbullying (β = 0.25, p < 0.001; β = -0.24, p < 0.001). However, indirect effect of attachment anxiety on cyberbullying was insignificant (Indirect effect = -0.02, LLCI = -0.05, ULCI = 0.001).3 Yet, attachment anxiety affected cyberbullying through its effects on angry and anxious RS. Therefore, Hypothesis 10a which proposed that the relationship between attachment anxiety and cyberbullying would be mediated by angry and anxious RS was supported. Finally, Hypothesis 10b which proposed the mediating role of angry RS in the link between attachment avoidance and cyberbullying was rejected since the association between attachment avoidance and angry RS was not significant (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

The Standardized Parameter Estimations of the Proposed Model

Discussion

The current study aimed to examine the direct links of attachment anxiety with PSMU, and attachment avoidance with cyberbullying; and also, to investigate the indirect effects of the attachment anxiety and attachment avoidance on PSMU and cyberbullying through their effects on the DT personality traits and RS among adolescents. In general, the findings supported the proposed theoretical model.

As expected, attachment anxiety was a significant predictor of PSMU among adolescent sample. That is, individuals who got high scores on attachment anxiety were more likely to engage in PSMU. This finding is consistent with the literature (Blackwell et al., 2017; Hart et al., 2015). The possible explanation for this relationship may be that individuals with high attachment anxiety think they can easily form interpersonal relationships on social media, which they cannot form in real life. In addition, Demircioğlu and Göncü-Köse (2021) argued that these individuals may be likely to avoid offline relationships and have a tendency to compensate for these relationships via social media. Indeed, the positive direct relationship between attachment anxiety and PSMU and the partial mediating effect of anxious RS on the relationship between attachment anxiety and PSMU suggest that social media is a safe haven for adolescents with high attachment anxiety and an anxious sensitivity to rejection. Such individuals may find meeting new people or presenting themselves much easier than they do on real, face-to-face occasions, and this may result in gradually increased, excessive use of social media platforms. The first contribution of the current study is revealing the association between attachment anxiety and PSMU among the adolescent sample. Furthermore, most studies focus on the link between attachment and PSMU using the four-category model of attachment. However, according to Sümer (2006), defining attachment styles with basic dimensions rather than distinct categories would be a more appropriate and valid approach. Since the dimensional attachment model rather than the categorical model was employed in the present study, the findings may be more useful for understanding the underlying mechanisms in the association between attachment and PSMU.

Surprisingly, the proposed direct positive link between attachment avoidance and cyberbullying was insignificant. In order to draw more precise conclusions, it is recommended to focus more on the relationship between these two variables in future studies and to examine this relationship with different moderators, especially with adolescent samples while controlling for the effects of social desirability. Although there was no significant direct relationship between attachment avoidance and cyberbullying, psychopathy fully mediated the link between attachment avoidance and cyberbullying. To be more specific, adolescents with high attachment avoidance tended to display more psychopathic traits, which in turn, was positively associated with bullying behaviors in online settings. Infants or children who are rejected by their primary caregivers or who are exposed to excessive control during their early ages are likely to have avoidant and anxious attachment styles (Bowlby, 1969). Avoidant attachment is characterized by a positive view of self and a negative view of others. Moreover, individuals who score high on the avoidance dimension have low levels of relationship anxiety and high levels of avoidance. These characteristics are highly likely to contribute to the development of psychopathic tendencies. Impulsivity, avoiding others, lack of empathy, and negative affectivity are among the main characteristics of psychopathy (e.g., Jonason et al., 2014). Psychopathic tendencies which are partially shaped by attachment avoidance, are likely to lead individuals who score high on these tendencies to engage in cyberbullying since they are indifferent to the feelings of others and highly impulsive (e.g., Demircioğlu & Göncü-Köse, 2021; Goodboy & Martin, 2015; Gumpel, 2014). Another main contribution of the present research was revealing the insignificant direct relationship between attachment avoidance and cyberbullying and the fully mediating effect of subclinical psychopathy in this relationship. In line with the findings, we suggest that adolescents with high attachment avoidance are likely to engage in cyberbullying behaviors when attachment avoidance is accompanied by psychopathic tendencies such as low levels of empathy and high level of impulsivity.

Moreover, psychopathy fully mediated the relationship between attachment avoidance and PSMU. As mentioned above, psychopathic tendencies triggered by high attachment avoidance are likely to lead individuals to engage in impulsive acts and uncontrolled behaviors such as PSMU. Furthermore, the results of the bivariate correlation analyses showed that PSMU and cyberbullying were positively associated. Taking the finding that psychopathy also fully mediated the relationship between attachment avoidance and cyberbullying into account, we suggest that avoidant adolescents who score high on psychopathy are likely to engage in PSMU for cyberbullying or related purposes. Yet, this proposition needs to be empirically examined by future studies which may employ quasi-experimental design or get information regarding the purpose of using social media from participants.

Contrary to expectations, the associations of Machiavellianism and narcissism with PSMU and cyberbullying were insignificant. Demircioğlu and Göncü-Köse (2021) also found the same results among university students. The possible explanation for the insignificant relationship between Machiavellianism and PSMU found in the current study may be that, in contrast to individuals who score high on psychopathy, Machiavellians’ level of social media usage may depend on the context. That is, individuals who get high scores on Machiavellianism may use or avoid using social media depending on perceived benefits, contacted individuals, or the context. Supporting this proposition, Demircioğlu and Göncü-Köse (2021) suggested that this result might be due to variability of the level of social media use among those who scored high on Machiavellianism. On the other hand, Miller and Campbell (2008) argued that narcissism can be categorized under two dimensions which are vulnerable and grandiose narcissism. Vulnerable narcissism includes preoccupation with grandiose fantasies, fragile self-confidence between majestic fantasies, and unstable self-esteem. On the contrary, assertive self-image and high levels of desire to be admired by others characterize grandiose narcissism. One possible explanation for the insignificant relationship between narcissism and PSMU found in the current study may be that the narcissism scale used measured the general (unidimensional) narcissism rather than vulnerable and grandiose narcissism as separate dimensions of the construct. In a meta-analytic study, grandiose narcissism was found to be significantly related to PSMU, while vulnerable narcissism was not significantly associated with PSMU (McCain & Campbell, 2018). It is highly likely that individuals who score high on grandiose narcissism excessively use social media for self-promotion and activities that aim to boost their self-esteem further (e.g., putting filtered selfies). Therefore, each “like” would please them and reinforce their use of social media contributing to PSMU. On the other hand, social media may not be very rewarding for individuals who score high on vulnerable narcissism since even minor negative feedback would damage their fragile self-esteem. Consistently, McCain and colleagues (2016) found that the consequences of online activities also differed depending on the types of narcissism. That is, individuals who scored high on grandiose narcissism were found to experience more positive affect after taking selfies on social media platforms than individuals who scored low on grandiose narcissism. On the contrary, individuals who scored high on vulnerable narcissism were found to experience more negative affect after taking selfies on social media platforms than individuals who scored low on vulnerable narcissism. Future studies may benefit from using the two-dimensional scales of narcissism and investigating the effects of vulnerable and grandiose narcissism on PSMU separately.

Not surprisingly, anxious RS was significantly associated with PSMU. Consistently, Demircioğlu and Göncü-Köse (2021) found a significant positive association between RS and PSMU among undergraduate university student sample. This finding suggests that adolescents who are highly sensitive to and anxious about rejection by others are highly likely to satisfy their needs for affiliation and socialization on social media platforms which provide them opportunities to present themselves in a desirable fashion. Furthermore, the links of both angry and anxious RS with cyberbullying were significant in the expected directions. That is, adolescents who scored high on angry RS were more likely to engage in cyberbullying than those who scored low on angry RS; whereas, adolescents who scored high on anxious RS were more likely to avoid cyberbullying than those who scored low on anxious RS. In other words, although both types of RS may be related to other aversive outcomes for children and adolescents, angry RS was found to be a risk factor and anxious RS was found to be a protective factor for cyberbullying. Another contribution of the current study was revealing that RS was not theoretically unidimensional and the two subdimensions of RS had differential effects on the same variable (i.e., cyberbullying). Future studies are strongly encouraged to use two-dimensional conceptualization of RS, especially while conducting studies with adolescent samples.

Individuals who scored high on attachment anxiety were expected to score high on Machiavellianism because they might be likely to try every means to establish and maintain relationships as well as to get approval from others in their daily lives. Even though attachment anxiety was found to be unrelated to Machiavellianism in the SEM analysis, the bivariate correlation between attachment anxiety and Machiavellianism was significant and future studies are suggested to investigate these links by testing possible moderator variables such as perceived availability of alternatives in close relationships and perceived social support from others.

As expected, there was a positive association between attachment avoidance and Machiavellianism. The positive relationship between avoidant attachment and Machiavellianism may imply that individuals who score high on avoidant attachment tend to direct their relationships in line with their own interests and retain their avoidant attitudes when there is no self-interest. This finding also confirms the proposition that Machiavellianism is characterized by a cold attitude towards others, low levels of empathy, and emotional detachedness (e.g., Paulhus & Williams, 2002).

Neither attachment anxiety nor attachment avoidance was found to be the predictors of narcissism. These insignificant results can also be related to measuring narcissism as a unidimensional construct. Indeed, in a longitudinal study, attachment avoidance was found to be a risk factor for grandiose narcissism whereas attachment anxiety was found to be a risk factor for vulnerable narcissism (Dakanalis et al., 2016). We suggest that attachment avoidance is likely to be positively related to grandiose narcissism since it includes a positive view of self and a negative view of others; whereas attachment anxiety is likely to be positively related to vulnerable narcissism because it includes a negative view of self and a positive view of others. Future studies are suggested to take these findings into consideration while investigating the relationships between attachment anxiety and the DT personality traits and examine the effects of attachment anxiety and attachment avoidance on vulnerable and grandiose narcissism separately in their attempts to replicate the findings and improve the proposed theoretical model.

As expected, attachment anxiety was found to be an antecedent of angry and anxious RS. Consistently, Downey and colleagues (1998) suggested that attachment anxiety and RS were positively related. Therefore, another contribution of this study is to show that angry and anxious RS may have the same antecedents, but they are associated with different outcome variables. The SEM results showed that both angry RS and anxious RS fully mediated the link between attachment anxiety and cyberbullying in the opposite directions. To be more precise, attachment anxiety was positively associated with angry RS, which in turn, increased the likelihood of cyberbullying. On the other hand, attachment anxiety was positively associated with anxious RS, which in turn, decreased the likelihood of cyberbullying. Individuals who get high scores on attachment anxiety may also get high scores on anxious RS and these individuals may attempt cyberbullying less than those who score low on anxious RS because they would not want to lose their existing relationships as a result of cyberbullying. However, if attachment anxiety leads to angry RS, it can also positively affect cyberbullying behaviors. Taking these findings into consideration, another theoretical contribution of this study is suggested to be demonstrating the fully mediated paths between attachment anxiety and cyberbullying, and indicating two main underlying psychological mechanisms (i.e., anxious RS and angry RS) in the association between these two variables.

Moreover, the relationship between attachment anxiety and PSMU was partially mediated by anxious RS. As mentioned above, attachment anxiety characterized by a negative view of self and a positive view of others is likely to increase the expectation of rejection by others. Sustained and elaborated fear of rejection results in a high level of anxious RS. While adolescents or individuals who score high on anxious RS are less likely to engage in cyberbullying to keep their online relationships, they seem to be more likely to engage in PSMU to form new relationships or to keep the existing ones, than those who score low on anxious RS. Moreover, it is likely that adolescents with high levels of anxious RS present only highly desirable characteristics on social media platforms to avoid rejection. Accordingly, the possibility of acceptance or admiration by others increases for them, which in turn, reinforces their social media use further. Therefore, high attachment anxiety is suggested to be the main risk factor for PSMU since it is positively associated with PSMU both directly and via its positive effects on anxious RS.

Practical implications of the findings

With the increasing rate of using social media, PSMU became an important topic of interest for both researchers and practitioners, and cyberbullying became a serious problem especially among adolescents (e.g., Baier et al., 2019). Determination of antecedents of PSMU and cyberbullying may facilitate implementation of effective intervention and training strategies. In line with the significant effects of attachment avoidance on Machiavellianism and psychopathy, the first practical implication of the findings may be guiding intervention strategies designed to convert “model of others” from negative to positive. In other words, within the framework of the findings of the current study, turning the "model of others" of adolescents into positive with early interventions may lead them to have lower levels of Machiavellian and psychopathic characteristics. Secondly, both angry and anxious RS were found to be antecedents of cyberbullying, and designing interventions specifically to decrease angry RS may be among the initial steps to reduce cyberbullying.

Limitations

As every study, the current study also has a number of limitations. Firstly, the data were based on self-reports. Yet, although there are quasi-experimental or experimental studies that focus on cyberbullying (e.g., Alhujailli et al., 2020; Palomares et al., 2020), in the literature, studies that investigated the effects of attachment style and personality traits mostly used self-report measurements (e.g., Safaria et al., 2020; Servidio et al., 2021). Secondly, we did not measure social desirability. Yet, the mean scores of all scales were close to the medium points. Thirdly, we employed a cross-sectional design which prevents us to reveal causal relationships. However, although it is not possible to draw confident inferences regarding the causal relationships with a cross-sectional study, causality aspects of the variables in the proposed model were theoretically supported. Yet, some of the relationships between the study variables may be suggested to have the reverse directions. Therefore, future studies are suggested to investigate the proposed relationships by employing longitudinal and/or quasi-experimental designs in other to draw more precise and confident conclusions. Finally, the present research is a single study and colleagues are encouraged to conduct research that includes multiple studies regarding the relationships of attachment styles with PSMU and cyberbullying to be able to present more robust findings.

Data availability

The dataset generated and analyzed during the current study is available on https://osf.io/beud4/.

Declarations

Ethics approval

Ethical approval for the study was obtained from the Social Sciences and Humanities Ethics Committee of the Çankaya University.

Consent to participate

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Conflict of interest

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

The data were collected right before the COVID-19 pandemic. Therefore, the results are not affected by the pandemic-related behavioral and/or attitudinal changes.

We did not get information about time spent and risks of cyberbullying. It was found that 58% of Turkish adolescents used the internet for more than two hours a day (Kaya & Dalgiç, 2021). Furthermore, in a study conducted with adolescents, it was found that 5% of adolescents were pure cyberbullying perpetrators, and 11.1% of them were pure cyberbullying victims (Eyuboglu et al., 2021).

Total indirect effect is calculated by summing the specific indirect effects which are calculated by multiplying the regression coefficient of the relationship between IV and the mediator (M) with the regression coefficient of the relationship between M and the DV (Hair et al., 2021). In our study, specific indirect effect including anxious RS was negative; whereas specific indirect effect including angry RS was positive, suppressing the total indirect effect. Hence, finding a CI including zero is understandable (Hayes, 2009) and it such cases where M is causally between the IV and the DV even if IV and DV are not related, some researchers prefer to use the term “IV’s indirect effect on DV through M” rather than using the term “mediator” for M. Other researchers (e.g., MacKinnon et al., 2000) advocate that excluding the significant IV → DV relationship as a precondition and assert that “competing effects might mitigate total X → Y relationships, when opposite signed direct and indirect effects are present” (Mathieu & Taylor, 2006, p.1038). We also agree with the latter argument.

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Abell L, Brewer G. Machiavellianism, self-monitoring, self-promotion and relational aggression on Facebook. Computers in Human Behavior. 2014;36:258–262. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2014.03.076. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Alhujailli A, Karwowski W, Wan TT, Hancock P. Affective and stress consequences of cyberbullying. Symmetry. 2020;12(9):1536. doi: 10.3390/sym12091536. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Amiri S, Jamali Y. The mediating role of empathy and emotion regulation in attachment styles and dark personality traits in adolescents. Iranian Journal of Psychiatry and Clinical Psychology. 2019;25(3):292–306. doi: 10.32598/ijpcp.25.3.292. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Andreassen CS. Online social network site addiction: A comprehensive review. Current Addiction Reports. 2015;2(2):175–184. doi: 10.1007/s40429-015-0056-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Andreassen CS, Torsheim T, Brunborg GS, Pallesen S. Development of a Facebook addiction scale. Psychological Reports. 2012;110(2):501–517. doi: 10.2466/02.09.18.PR0.110.2.501-517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andreassen CS, Pallesen S, Griffiths MD. The relationship between addictive use of social media, narcissism, and self-esteem: Findings from a large national survey. Addictive Behaviors. 2017;64:287–293. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2016.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ang RP. Adolescent cyberbullying: A review of characteristics, prevention and intervention strategies. Aggression and Violent Behavior. 2015;25:35–42. doi: 10.1016/j.avb.2015.07.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ang RP, Ong EY, Lim JC, Lim EW. From narcissistic exploitativeness to bullying behavior: The mediating role of approval-of-aggression beliefs. Social Development. 2010;19(4):721–735. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9507.2009.00557.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Arbuckle, J. L. (2013), Amos (Version 22.0), Computer Program, SPSS/IBM, Chicago.

- Armsden GC, Greenberg MT. The inventory of parent and peer attachment: Individual differences and their relationship to psychological well-being in adolescence. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 1987;16(5):427–454. doi: 10.1007/BF02202939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arrigo BA, Shipley S. The confusion over psychopathy (I): Historical considerations. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology. 2001;45(3):325–344. doi: 10.1177/0306624X01453005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ayas T, Horzum MB. Sanal zorba / hurban ölçek geliştirme çalışması. Akademik Bakış Dergisi. 2010;19:1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Baier D, Hong JS, Kliem S, Bergmann MC. Consequences of bullying on adolescents’ mental health in Germany: Comparing face-to-face bullying and cyberbullying. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 2019;28(9):2347–2357. doi: 10.1007/s10826-018-1181-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bartholomew K, Horowitz LM. Attachment styles among young adults: A test of a four-category model. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1991;61(2):226–244. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.61.2.226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blackwell D, Leaman C, Tramposch R, Osborne C, Liss M. Extraversion, neuroticism, attachment style and fear of missing out as predictors of social media use and addiction. Personality and Individual Differences. 2017;116:69–72. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2017.04.039. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bloxsom CA, Firth J, Kibowski F, Egan V, Sumich AL, Heym N. Dark shadow of the self: How the dark triad and empathy impact parental and intimate adult attachment relationships in women. Forensic Science International: Mind and Law. 2021;2:100045. [Google Scholar]

- Boer, M., Van Den Eijnden, R. J., Boniel-Nissim, M., Wong, S. L., Inchley, J. C., Badura, P., ... & Stevens, G. W. (2020). Adolescents' intense and problematic social media use and their well-being in 29 countries. Journal of Adolescent Health, 66(6), S89-S99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Bondü R, Krahé B. Links of justice and rejection sensitivity with aggression in childhood and adolescence. Aggressive Behavior. 2015;41(4):353–368. doi: 10.1002/ab.21556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby, J. (1969). Attachment and loss: Vol. 1. Attachment. Basic Books

- Bowlby J. A secure base: Parent-child attachment and healthy human development. Basic Books; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Braginsky DD. Machiavellianism and manipulative interpersonal behavior in children. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 1970;6(1):77–99. doi: 10.1016/0022-1031(70)90077-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brennan KA, Clark CL, Shaver PR. Self-report measurement of adult attachment: An integrative overview. In: Simpson JA, Rholes WS, editors. Attachment theory and close relationships. Guilford Press; 1998. pp. 46–76. [Google Scholar]

- Caplan SE. Relations among loneliness, social anxiety, and problematic internet use. CyberPsychology & Behavior. 2007;10(2):234–242. doi: 10.1089/cpb.2006.9963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter CJ. Narcissism on Facebook: Self-promotional and anti-social behavior. Personality and Individual Differences. 2012;52(4):482–486. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2011.11.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Casale S, Banchi V. Narcissism and problematic social media use: A systematic literature review. Addictive Behaviors Reports. 2020;11:100252. doi: 10.1016/j.abrep.2020.100252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chabrol H, Van Leeuwen N, Rodgers R, Séjourné N. Contributions of psychopathic, narcissistic, Machiavellian, and sadistic personality traits to juvenile delinquency. Personality and Individual Differences. 2009;47(7):734–739. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2009.06.020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Conradi HJ, Boertien SD, Cavus H, Verschuere B. Examining psychopathy from an attachment perspective: The role of fear of rejection and abandonment. The Journal of Forensic Psychiatry & Psychology. 2015;27(1):92–109. doi: 10.1080/14789949.2015.1077264. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Costanzo A, Santoro G, Russo S, Cassarà MS, Midolo LR, Billieux J, Schimmenti A. Attached to virtual dreams: The mediating role of maladaptive daydreaming in the relationship between attachment styles and problematic social media use. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 2021;209(9):656–664. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0000000000001356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dakanalis A, Clerici M, Carrà G. Narcissistic vulnerability and grandiosity as mediators between insecure attachment and future eating disordered behaviors: A prospective analysis of over 2,000 freshmen. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2016;72(3):279–292. doi: 10.1002/jclp.22237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Del Rey, R., Casas, J. A., Ortega-Ruiz, R., Schultze-Krumbholz, A., Scheithauer, H., Smith, P., ... & Guarini, A. (2015). Structural validation and cross-cultural robustness of the European Cyberbullying Intervention Project Questionnaire. Computers in Human Behavior, 50, 141-147.

- Demircioğlu, Z. I. (2020). Antecedents of social media addiction and cyberbullying among adolescents: Attachment, the Dark Triad, rejection sensitivity and friendship quality [Unpublished master's thesis]. Çankaya University

- Demircioğlu ZI, Göncü-Köse A. Effects of attachment styles, dark triad, rejection sensitivity, and relationship satisfaction on social media addiction: A mediated model. Current Psychology. 2021;40(1):414–428. doi: 10.1007/s12144-018-9956-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dilmaç B. Psychological needs as a predictor of cyber bullying: A preliminary report on college students. Educational Sciences: Theory and Practice. 2009;9(3):1307–1325. [Google Scholar]

- Doane AN, Pearson MR, Kelley ML. Predictors of cyberbullying perpetration among college students: An application of the theory or reasoned action. Computers in Human Behavior. 2014;36:154–162. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2014.03.051. [DOI] [Google Scholar]