Summary

Background

Acute kidney disease (AKD) defines the period after kidney damage and it is a critical period of both repair and fibrotic pathways. However, the outcomes of patients with AKD have not been well-defined.

Methods

In this meta-analysis, PubMed, Embase, Cochrane and China National Knowledge Infrastructure were searched on July 31,2022. We excluded studies including patients undergoing kidney replacement therapy at enrollment. The data was used to conduct a random-effects model for pool outcomes between patients with AKD and non-AKD (NKD). This study is registered with PROSPERO, CRD 42021271773.

Findings

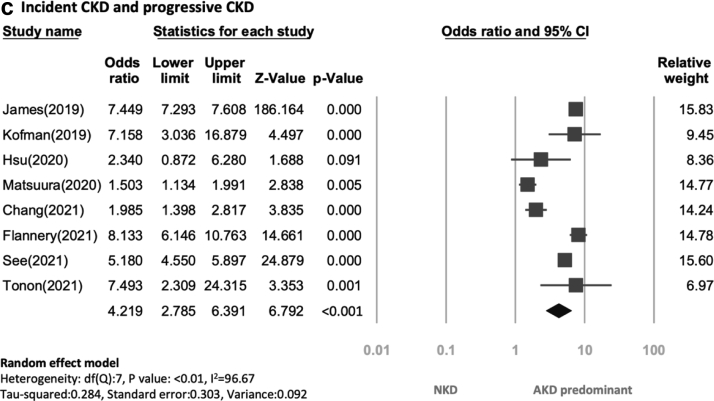

The search generated 739 studies of which 21 studies were included involving 1,114,012 patients. The incidence rate of community-acquired AKD was 4.60%, 2.11% in hospital-acquired AKD without a prior AKI episode, and 26.11% in hospital-acquired AKD with a prior AKI episode. The all-cause mortality rate was higher in the AKD group (26.54%) than in the NKD group (7.78%) (odds ratio [OR]: 3.62, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 2.64 to 4.95, p < 0.001, I2 = 99.11%). The rate of progression to end-stage kidney disease (ESKD) was higher in the AKD group (1.3%) than in the NKD group (0.14%) (OR: 6.58, p < 0.001, I2 = 94.95%). The incident rate of CKD and progressive CKD was higher in the AKD group (37.2%) than in the NKD group (7.45%) (OR:4.22, p < 0.001, I2 = 96.67%). Compared to the NKD group, patients with AKD without prior AKI had a higher mortality rate (OR: 3.00, p < 0.001, I2 = 99.31%) and new-onset ESKD (OR:4.96, 95% CI, p = 0.002, I2 = 97.37%).

Interpretation

AKD is common in community and hospitalized patients who suffer from AKI and also occurs in patients without prior AKI. The patients with AKD, also in those without prior AKI had a higher risk of mortality, and new-onset ESKD than the NKD group.

Funding

This study was supported by Ministry of Science and Technology (MOST) of the Republic of China (Taiwan) [grant number, MOST 107-2314-B-002-026-MY3, 108-2314-B-002-058, 110-2314-B-002-241, 110-2314-B-002-239], National Science and Technology Council (NSTC) [grant number, NSTC 109-2314-B-002-174-MY3, 110-2314-B-002-124-MY3, 111-2314-B-002-046, 111-2314-B-002-058], National Health Research Institutes [PH-102-SP-09], National Taiwan University Hospital [109-S4634, PC-1246, PC-1309, VN109-09, UN109-041, UN110-030, 111-FTN0011] Grant MOHW110-TDU-B-212-124005, Mrs. Hsiu-Chin Lee Kidney Research Fund and Chi-mei medical center CMFHR11136. JAN is supported, in part, by grants from the National Institute of Health, NIDDK (R01 DK128208 and P30 DK079337) and NHLBI (R01 HL148448-01).

Keywords: Acute kidney injury, Acute kidney disease, Chronic kidney disease, End-stage kidney disease

Research in context.

Evidence before this study

Increasing evidence suggests that acute kidney disease (AKD) is a common entity associated with higher risks of mortality and adverse kidney events. Among the existing studies evaluating outcomes of AKD patients, most focused on patients with AKD following acute kidney injury (AKI), while minor studies focused on those without prior AKI. So we searched PubMed, Embase, China National knowledge infrastructure (CNKI), and the Cochrane library database using the keywords “acute kidney disease,” “acute kidney diseases,” and “subacute kidney injury” to identify all relevant studies published from January 1, 2000, to July 31, 2022, without any language limitations. We used the Newcastle Ottawa Scale (NOS) to evaluate the methodological quality of the included publications. The strength of evidence regarding primary and secondary outcomes was graded with the Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, and Evaluation (GRADE) system. We also performed the trial sequential analysis (TSA) to control type I and type II errors and calculate the required information size (RIS) for all-cause mortality. At the time of writing, no high quality systematic review and meta-analysis of studies of AKD and outcomes conducted in any setting was identified that synthesized studies published between 2000 and 2022.

Added value of this study

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first meta-analysis assessing the outcomes of AKD patients. The current study demonstrated the incidences of 4.60% for community-acquired AKD, 5.67% for AKD in hospitalized patients, as well as 26.11% and 2.11% for hospital-acquired AKD with and without a prior AKI episode, respectively. Our results showed that the patients with AKD had a higher risk of mortality, end-stage kidney disease (ESKD), incident CKD, and progressive CKD than those without AKD. Further, AKD patients without prior AKI also had a higher mortality rate and risk of new-onset ESKD than those without AKD. This systematic review and meta-analysis provides the most up-to-date synthesis of the current evidence base on AKD with and without prior AKI, and importantly also synthesizes available data regarding their outcomes.

Implications of all the available evidence

AKD is common in community and hospitalized patients regardless of prior AKI. The patients with AKD had higher risks of mortality and ESKD when compared with their non-kidney disease counterparts. This observation was consistent in the subgroup analyses according to prevalent CKD, variable follow-up periods, patient characteristics (surgical versus medical patients), and study designs. Our review recommends clinicians should pay more attention to patients with AKD regardless of prior AKI, from hospital or community and highlights the need for future research to identify the components and mechanisms of effective interventions to inform future public health policy about AKD care.

Introduction

Different from acute kidney injury (AKI) and chronic kidney disease (CKD), which have well-established definitions in clinical practice and public health, acute kidney disease (AKD) is a relatively novel entity.1 According to the latest KDIGO consensus, AKD defines abnormalities of kidney function and/or kidney structure with implications for kidney health last for 7–90 days.2

In clinical practice, AKD is common among patients in the universal health system, but most of the patients with AKD are not routinely recognized by the current care system.3 AKD plays a critical role in linking patients to subsequent kidney damage and other adverse events. AKD may occur in a patient without known prior AKI. According to KDIGO consensus conference,” kidney disease and disorder “are used to describe abnormalities of kidney function and/or structure. And AKD and CKD are harmonized under kidney disease and distinguished by duration. On the other hand, “acute” means a condition of recent or sudden onset which is short-lived and reversible. AKD may include AKI, but, more important, also includes abnormalities in kidney function that are not as severe as AKI or that develop over a period of >7 days.2 Recent data suggest AKD without prior AKI is common and that, like AKI, is associated with higher risks of mortality and progression to CKD.3

Nevertheless, previous studies mainly focus on AKD following AKI and confirm that AKD following AKI is associated with increased risks of both mortality and incident CKD. Only a few studies illustrated AKD without prior AKI and its related outcomes.3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8 And there remains a gap in clinical care and treatment for patients with AKD, even those without prior AKI.

Therefore, we conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis to assess the clinical outcomes, including incident CKD, progressive CKD, new-onset end-stage kidney disease (ESKD), and all-cause mortality of patients with AKD.

Methods

Search strategy and selection criteria

We performed this systematic review and meta-analysis following the Preferred Reporting Items of Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) recommendation and Cochrane methods. The systematic review protocol had been prospectively registered on PROSPERO [CRD42021271773].

We comprehensively searched PubMed, Embase, China National Knowledge infrastructure and Cochrane using terms associated with "acute kidney disease", "acute kidney diseases", “subacute kidney injury” and “AKD” to identify all relevant studies published from January 1, 2000 to July 31, 2022 without any language limitations (Supplementary Material S1). We also manually checked the reference list of related review articles and editorials to identify additional studies. The full texts of potentially eligible studies were retrieved and evaluated for quality assessment and data synthesis. The summary data was extracted from enrolled studies. In addition, we further contacted the authors of eligible studies for missing data if the relevant information was incomplete or missing.

We included all studies that enrolled adult patients (≥18 years old) diagnosed with AKD who did not receive chronic kidney replacement therapy (KRT) at enrollment in each study and compared the outcomes with those who did not have AKD (i.e., non-AKD [NKD]).

We excluded studies of animals or patients undergoing KRT before enrollment, did not provide mortality information and were published as editorials, correspondences, conference abstracts, and commentary articles.

Data analysis

Two reviewers (CC Su; JY Chen) independently extracted all the relevant data from the included studies. We documented the following characteristics: sample sizes, population setting and site (i.e., single-centre, multi-centres/mix population, surgery), average age, genders, and comorbidities (i.e., hypertension, type 2 diabetes mellitus, heart failure). All discrepancies were resolved by discussion with a third investigator (CC Shiao) and the fourth investigator (VC Wu).

We used the Newcastle Ottawa Scale (NOS) to evaluate the methodological quality of the included publications.3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23 The scale contains eight domains, including four domains in the "selection" category, one in the "comparability" category, and three in the "exposure" category. A study with a total score of >7 was graded as a high-quality study.

In our study, AKD is defined as presence of AKI, a >50% increase in serum creatinine, or a ≥35% decrease in eGFR from baseline for <3 months or as a newly developed eGFR <60 ml/min/1.73 m2 for <3 months based on KDIGO criteria.24 Some of the included studies defined AKD according to the KDIGO consensus.3,4,7,13,16 Some of the included studies5,6,8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13,15,18, 19, 20, 21,23 defined AKD according to Acute Disease Quality Initiative (ADQI) 16 Workshop.1 We identified AKD stage 0 which is defined according to ADQI 16 workshop as the NKD group. Of note, Lin et al.14 followed the criteria of the ADQI 16 workshop, and the patients with AKD enrolled in the study were identified as successfully weaning from dialysis after an episode of AKI. Fujii et al.22 described a progressive subacute kidney functional impairment which was defined as subacute-acute kidney injury (s-AKI).

The primary outcome of the current study was all-cause mortality. The secondary outcomes included ESKD, incident CKD, and progressive CKD. ESKD was defined as the initiation of long-term KRT. Incident CKD was defined as a development of estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) < 60 ml/min/1.73 m2 for at least three months during follow-up periods in patients with a baseline eGFR > 60 ml/min/1.73 m2. Progressive CKD was defined as a decreased eGFR to <15 ml/min/1.73 m2 or a reduced eGFR of ≥50% in patients with a baseline eGFR <60 ml/min/1.73 m2. All outcomes were prespecified.

The strength of evidence regarding primary and secondary outcomes was graded with the Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, and Evaluation (GRADE) system. The certainty of the evidence for each outcome was categorized as high, moderate, low, or very low.

We used a random-effects model to compare the outcomes of interest between AKD and NKD patients quantitatively. The raw data was used from included studies to calculate the outcomes. And the odds ratio (OR) and the 95% CI were extracted from included studies. In addition, the hazard ratio (HR) of mortality was also analyzed. We conducted a meta-regression to evaluate possible reasons for the differences in the AKD vs. NKD group or across studies. We applied Funnel plots to examine potential publication bias. The included studies' statistical heterogeneity was calculated using the χ2 test and the I2 statistic. An I2 >50% or a P < 0.05 for the Q-statistic indicated substantial heterogeneity. The extent of heterogeneity was categorized into mild (I2 < 30%), moderate (30% ≤ I2 < 50%), and substantial (I2 ≥ 50%).

We also performed the trial sequential analysis (TSA) (Copenhagen Trial Unit, Centre for Clinical Intervention Research, Denmark, software 0.9.5.10 Beta software) to control type I and type II errors and calculate the required information size (RIS) for all-cause mortality. The conventional non-superiority boundaries were set at significance levels of 0.05 and a power of 90%, and the α-spending boundaries were calculated using the O'Brien-Fleming procedure. TSA tested the all-cause mortality to assess each article's temporal and cumulative effect on the present study.

We used the Comprehensive Meta-Analysis software (Version 3.3.070, November 20, 2014, New Jersey, USA) for all statistical analyses. Statistical significance was defined as p-values < 0.05.

Subgroup analyses were subsequently conducted using the baseline characteristics, e.g., CKD or prior AKI history, population setting (surgical versus. non-surgical populations), site (single-centre versus multi-centres), study design (prospective versus retrospective), follow-up period, ICU admission, total included numbers of the trial and diabetic mellitus (DM) population. In addition, prespecified subgroup analyses of all-cause mortality and new-onset ESKD were conducted, and the 95% confidence interval (CI) was provided for further evaluation. In our study, AKD without prior AKI was defined if the index eGFR was less than 60 ml/min/1.73 m2 and the preceding measure was greater than or equal to 60 ml/min/1.73 m2 or there was no preceding creatinine or eGFR measurement and albuminuria was absent or not measured prior to the index date.3

Role of the funding source

The funder of the study had no role in the study design, data collection, data analysis, interpretation or writing of the paper. CCS, JYC and VCW had access to dataset. VCW had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

Results

Study search outcomes and included patients

We identified 1334 studies through a comprehensive search and excluded 595 duplicate articles and 739 papers by eligibility criteria. Finally, 21 studies, including 1,114,012 patients with complete data and outcomes of interest, were enrolled for the final meta-analysis (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

The flow chart showing the study's enrollment.

Among the included patients, 67,173 patients were diagnosed with AKD (AKD group) while 1,046,839 patients did not (NKD groups) (Table 1). Among the 21 studies, 17 enrolled patients diagnosed as AKD with previous AKI,4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21,23 and the three did not include patients who had previous AKI.3,14,22 The remaining study did not express whether or not the included patients with AKI history.16

Table 1.

Summary of the baseline characteristics of the included studies.

| Study/year | Population | Study design | AKD definition | Male (%) | Age (years) | Patient number (n) (AKD/NKD) |

Follow up period | DM/HTN/CHF/CKD (%) | AKI before enrollment (%) (AKD/NKD) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mizuguchi17 (2018) |

Single-center operation population | Retrospective | kidney damage for less than 3 months after AKI, GFR less than 60 mL/min/1.73 m2 for less than 3 months, or a decrease in glomerular filtration rate 35% or more or increase in sCr by more than 50% for less than 3 months | 62.9 | 66.9 | 53/1141 | 2–4 weeks | NR/NR/NR/43 | 74/26.6 |

| James3 (2019) |

Multicenter (health care system) | Retrospective | Decrease in eGFR of 35%, an increase in sCr of 50%, or new onset of albuminuria, eGFR was less than 60 mL/min/1.73 m2 < 3 months | 42.6 | 50.6 | 42487/921116 | 8 years | 2.92/7.11/0.10/0 | 0/0 |

| Kofman13 (2019) |

Single-center Acute STEMI and ICU population |

Retrospective | Lack of recovery of renal function (to a degree of ≤0.1 mg/dl of admission serum creatinine level) within 7 days of renal insult | 70.7 | 71.2 | 81/144 | 1271 ± 903 days | 32.9/53.3/NR/51 | 100/100 |

| Mima16 (2019) |

Single-center HSCT population |

Retrospective | AKI or subacute decreases in GFR (i.e., GFR <60 ml/min/1.73 m2for less than 3 months or decrease in GFR by 35% or increase in serum creatinine by >50% for less than 3 months) | 63.9 | 49a | 17/91 | 100 days | 8.3/11.1/NR/NR | NR |

| Chen9 (2020) |

Single-center CCU admission population |

prospective | Kidney damage lasting between 7 and 90 days according to ADQI 16 workgroup | 75 | 64 ± 1 | 128/141 | 5 years | 41/61/34.6/16.4 | NR |

| Hsu6 (2020) |

Single-center ECMO and ICU population |

Retrospective | Increase of serum creatinine level to 1.5 X occurred or persisted in 7–90 days after renal injury | 66.7 | 53.1 ± 16.2 | 75/93 | 10 years | NR/NR/NR/28.6 | 82.7/64.5 |

| Matsuura15 (2020) |

Multicenter Cardiac surgery and ICU patients |

Retrospective | Elevation in serum creatinine to at least 1.5-fold from baseline in >7 day | 68 | 72.2 | 403/453 | 2 year | 39.7/66.6/99.3/54.3 | 100/100 |

| Tonon4 (2021) |

Single-center Liver cirrhosis population |

prospective | GFR <60 ml/min per 1.73 m2, or a decrease in GFR of >35%, or an increase in sCr of >50% for less than 3 months | 66.9 | 54.0 ± 11.9 | 80/192 | 60 months | 24.6/NR/NR/0 | 21.3/0 |

| See7 (2021) |

Single-center Hospitalized population |

Retrospective | AKI, a >50% increase in sCr, or a ≥35% decrease in eGFR from baseline for <3 months, or as a newly developed eGFR <60 mL/min/1.73 m2 for <3 months. | 49.6 | 58.1 | 1260/32262 | 2.6 years (IQR 0.8–4.4) | 14/8/3/0 | 62.1/0 |

| Yan20 (2021) |

Multicenter | Retrospective | Persistent renal damage and/or renal dysfunction; a >50% increase in sCr or ongoing dialysis for a duration of 7–90 days | 62.7 | 54.3 | 1161/1395 | 1 year | 19/34.6/16.5/4 | 100/100 |

| Gameiro12 (2021) |

Single-center Septic AKI and ICU population |

Retrospective | Presenting at least KDIGO Stage 1 criteria for >7 days after an AKI initiating event | 56.3 | 62.6 ± 22.6 | 138/118 | 45.9 ± 43.3 months | 22.3/46.1/NR/55.5 | 100/100 |

| Flannery10 (2021) |

Single-center Septic AKI and ICU population |

Retrospective | Based on the ratio of the last serum creatinine value (hospital discharge or within 90 days from discharge) and baseline serum creatinine according to ADQI 16 workgroup | 52.4 | 63.2 | 251/2056 | 14.2 months (IQR, 5.3–26.7) | 23.7/44.4/4.2/51.5 | 100/0 |

| Xiao19 (2020) |

Multicenter | Retrospective | Acute or subacute damage and/or loss of kidney function for 7–90 days after exposure to an AKI initiating event; SCr levels were 1.5 X higher than baseline | 75.9 | 55.4 | 1359/1197 | 90 days (from admission) | 19/29.2/NR/12 | 100/100 |

| Fuhrman11 (2021) |

Single center Cardiac ICU |

Retrospective | A serum creatinine ≥1.5 X the baseline creatinine between 7 and 90 days after the diagnosis of acute kidney injury | 59.5 | 28.8 | 24/171 | 5 years | NR/NR/NR/3 | 100/39 |

| Peerapornratana18 (2020) |

Multicenter | Retrospective | Persistent reduction in glomerular filtration rate beyond 7 days but for less than 90 days | 58.5 | 61.3 | 161/318 | 1 year | 36.5/61.6/10.9/15.4 | 100/100 |

| Lin14 (2018) |

Multicenter (healthcare system) | Retrospective | weaning from dialysis after an episode of AKI | 62.2 | 57.16 | 3307/9921 | 5.99 yearsb | 0/54.9/15.8/NR | 0/0 |

| Chang5 (2021) |

Multicenter Post type A aortic dissection surgery |

Retrospective | Serum creatinine levels 1.5 X basline creatinine according to ADQI 16 workgroup | 67.8 | 57.6 | 169/527 | 4.4 years | 7.8/71.8/NR/10.9 | 79.9/45.7 |

| Marques21 (2021) |

Single center COVID-19 |

Retrospective | Present at least KDIGO stage 1 > 7 days after an AKI initiating event | 56.3 | 71.7 ± 17.0 | 87/237 | 33.6 ± 44.3 days | 30.4/70.2/NR/25.4 | 100/100 |

| Chen8 (2022) |

Multicenter Heart failure |

Retrospective | A serum creatinine ≥1.5 X the baseline creatinine between 7 and 90 days | 55.4 | 71.9 | 1592/5927 | 5 years | 39.2/58.5/100/49.2 | 16.8/6.9 |

| Wang23 (2022) | Multicenter (health care system) | Retrospective | loss of kidney function for a duration between 7 and 90 days after exposure to an AKI initiating event | 45 | 75 (IQR, 63–83) | 13723/24988 | 2.1 years (IQR, 0.4–4.7) | 27/37/12/36 | 100/100 |

| Fujii22 (2014) | Single center | Retrospective | A serum creatinine ≥1.5 X the baseline creatinine between 7 and 90 days | 53.6 | 60.1 | 574/43493 | 3 years | NR | 0/0 |

Abbreviations: AKD, acute kidney disease; AKI, acute kidney injury; CCU, coronary care unit; CHF, congestive heart failure; CKD, chronic kidney disease; DM, diabetes mellitus; ECMO, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation; GFR, glomerular filtration rate; HSCT, hematopoietic stem cell transplantation; HTN, hypertension; ICU, intensive care unit; IQR, interquartile ranges; NKD, non-acute kidney disease; NR, not reported; sCr, serum creatinine; STEMI, ST-elevation myocardial infarction.

Median (interquartile ranges, 16–70 years).

Median follow up periods.

Among all included studies, the incidence of community-acquired AKD was 4.60%. In 17 of the 21 included studies, the incidence of AKD was 5.67% in overall hospitalized patients.5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13,15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22 The other four articles enrolled both hospitalized patients and outpatients.3,4,14,23 From 15 of the 21 enrolled studies, the incidence of hospital-acquired AKD was 26.11% with a prior AKI episode in the same index hospitalization.5, 6, 7, 8,10, 11, 12, 13,15,17, 18, 19, 20, 21,23 In 7 of the 21 included studies, the incidence of hospital-acquired AKD was 2.11% without a prior AKI episode.5, 6, 7, 8,11,17,22

Quality of enrolled trials

All the enrolled studies were published within the eight-year period (2014–2022). There were discrepancies between the populations (eg. hematopoietic stem cell transplantation [HSCT], acute ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction [STEMI], health care system, cardiac surgery, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation [ECMO], liver cirrhosis), variable sample size, and observation period.

We categorized the patients of all the enrolled studies into the AKD and NKD groups and compared the outcomes between the two groups (Table 2). The score of the NOS for included studies was 4–8 (Supplementary Table S1).

Table 2.

Summary of the outcome of the included studies.

| Study/year | CKD (%) (AKD vs NKD) |

KRT (%) (AKD vs NKD) |

Mortality (%) (AKD vs NKD) |

HR/RR/OR (CI) for primary endpoint | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mizuguchi17 (2018) |

NR | 22.6 vs 0.97 | 15.1 vs 1.75a | NR | In-hospital mortality 30-day mortality Need for KRT |

| James3 (2019) |

37.4 vs 7.4 | 0.6 vs 0.1 | 25.8 vs 7.3 | 1.42 (95% CI, 1.39–1.45)c | Mortality Development of CKD Progression of CKD ESKD with the initiation of KRT |

| Kofman13 (2019) |

59 vs 7 | NR | 35 vs 11b | 4.87 (95% CI: 1.84–12.9, P = 0.001)c | 90-day mortality Long-term mortality Long-term renal outcome |

| Mima16 (2019) |

NR | 23.5/NR | 29.4 vs 20.2 | NR | The 100-day overall survival rate |

| Chen9 (2020) |

NR | 5.5/0.7 | 22.7 vs 14.2 | NR | Overall hospital Mortality 5-year mortality |

| Hsu6 (2020) |

41.4/11.3 | NR | 74.7 vs 28.0 | NR | Survival rate |

| Matsuura15 (2020) |

45 vs 2.8 | NR | 19.9 vs 2 | 63.0 (95% CI, 27.9–180.6)d | 90-day mortality 90-day renal recovery |

| Tonon4 (2021) |

13.8 vs 2.1 | NR | 65.2 vs 11 | NR | Development of renal impairment 5- year mortality Complication of cirrhosis |

| See7 (2021) |

28.4 vs 7.1 | 0.6 vs 0.07 | 34.2 vs 10.7 | NR | MAKEs CKD Kidney failure Death |

| Yan20 (2021) |

NR | 1.9 vs 0.3 | 25.3 vs 12 | NR | Chronic dialysis One year mortality |

| Gameiro12 (2021) |

NR | 16.7 vs 2.5 | 34.1 vs 6.8e | NR | 30- day mortality Need for long term dialysis Long-term mortality |

| Flannery10 (2021)f |

53.4 vs 12.2 | 22.3 vs 6 | 9.3 vs 8.3 | NR | CKD incidence, progression of CKD, KFRT Death |

| Xiao19 (2020) |

NR | NR | 19.13 vs 6.1 | 1.980 (95% CI, 1.427–2.747)c | Death ESKD |

| Fuhrman11 (2021) |

NR | NR | 50 vs 9.4 | 11.13 (95% CI: 3.79–32.68)g | One- year mortality Five- year mortality |

| Peerapornratana18 (2020) |

NR | NR | 36.6 vs 31.8 | 1.20 (95% CI, 0.87–1.65)c | ICU and hospital length of stay in-hospital mortality, 90-days mortality 1-year mortality |

| Lin14 (2018) |

NR | NR | 31.8 vs 26.8 | NR | New-onset diabetes All-cause mortality |

| Chang5 (2021) |

55 vs 38.1 | 4.7 vs 2.8 | 10.1 vs 6.1 | 1.58 (95% CI, 0.81–3.09)c | Recurrent AKI De novo CKD ESKD All-cause mortality Respiratory failure Ischemic stroke |

| Marques21 (2021) |

NR | 0.4 vs 2.3 | 34.5 vs 6.8a | NR | In-hospital mortality Discharge on KFRT |

| Chen8 (2022) |

14.7 vs 18.4 | 16.8 vs 9.3 | 40.8 vs 24.5 | NR | All cause death ESKD Heart failure hospitalization |

| Wang23 (2022) |

NR | 1 vs 0.2 | 27 vs 20 | NR | Death Progression to chronic KRT |

| Fujii22 (2014) |

NR | 0.17 vs < 0.01 | 7.5 vs 1.2 | NR | Hospital mortality KRT |

Abbreviations: AKD, acute kidney disease; AKI, acute kidney injury; CKD, chronic kidney disease; CI, Confidence interval; ESKD, end-stage kidney disease; HR: hazard ratio; ICU, intensive care unit; KFRT, kidney failure with replacement therapy; KRT, kidney replacement therapy; MAKEs, major adverse kidney disease; NKD, non-acute kidney disease; NR, not reported; OR, odds ratio; RR, relative risk; RRT, renal replacement therapy.

The data was converted from the study figure.

In-hospital mortality.

90-day mortality.

Adjusted hazard ratio.

Adjusted odds ratio.

30-day mortality. fthe data was converted from the study figure.

Odds ratio.

Mortality, ESKD, incident CKD, and progressive CKD

A total of 99,231 patients died during the study periods, attributing an overall all-cause mortality rate of 8.90%. The all-cause mortality rate was significantly higher in the AKD (26.54%) than in the NKD group (7.78%) (OR:3.62, 95% CI: 2.64 to 4.95 p < 0.001). However, the heterogeneity among included studies was high (I2, 99%) (Fig. 2a). Nine articles reported HR for mortality,3,5,6,12, 13, 14,18,19,23 which was also higher in AKD than NKD group (HR:1.39, 95%CI: 1.25 to 1.55, p < 0.001) (Supplementary Fig. S1). The observation period for all-cause mortality ranged from one month to six years.

Fig. 2.

Forrest plots depicting the comparisons of (a) all-cause mortality, (b) ESKD, and (c) incident CKD and progressive CKD between the AKD group versus the NKD group. Abbreviations: AKD, Acute kidney disease; CKD, Chronic kidney disease; ESKD, End-stage kidney disease; NKD, Non-acute kidney disease.

As to the secondary outcomes, the average rate of progression to ESKD was 0.2% among the twelve studies that reported the information on ESKD during an average observational period of 7.7 years.3,5,7,8,10,12,13,17,20, 21, 22, 23 There was a higher possibility of ESKD in the AKD group (1.3%) than in the NKD group (0.14%) (OR: 6.58, 95% CI: 3.75 to 11.55, p < 0.001), but the heterogeneity among studies was high (I2, 94.9%) (Fig. 2b).

In addition, six studies reported incident CKD,3, 4, 5, 6, 7,10 and two studies focused on progressive CKD.5,10 The cumulative rate of incident CKD and progressive CKD was 8.78% during an average follow-up period of 7.8 years, and it was higher in the AKD group (37.2%) than in the NKD group (7.45%) (OR:4.22, 95% CI: 2.79 to 6.39, p < 0.01). The heterogeneity among included studies was also high (I2, 96.67%) (Fig. 2c).

Trial sequential analysis

To determine whether current studies are enough to make a robust conclusion about the comparison of all-cause mortality between patients with AKD and patients with NKD, we conducted a TSA for our primary outcome (Supplementary Fig. S2). We assumed a mortality rate of 26.7% in the AKD group and 8.1% in the NKD group, roughly the median of included studies. By adopting a type 1 error of 5% and a power of 90%, we calculated the mortality-related required information size (RIS) to be 49,618 patients after adjusting for heterogeneity. The cumulative Z-curve crossed the conventional boundary for statistical significance, the trial sequential monitoring boundary, and the RIS without entering the futility zone., indicating that the current evidence reached a solid conclusion that the risk of all-cause mortality of AKD has been consistently higher than that of NKD. The results of TSA confirmed that the sample size and effect size were sufficiently large, and it is unlikely for further evidence to alter this conclusion.

Additionally, Supplementary Fig. S2 showcased the cumulative influence of each included trial temporally. From 2018 to 2022, as trials were progressively reported, we observed a consistently higher risk of all-cause mortality among patients with AKD compared to those with NKD. The cumulative Z-score has constantly been growing along with the total accrued sample size except for the study from Mizguguchi et al.,17 reflecting the unwavering significance of the meta-analysis.

Subgroup analysis

In line with our main findings, all-cause mortality, ESKD, and incident/progressive CKD risks were higher in the AKD group than in the NKD group for all subgroup analyses (Supplementary Fig. S3a and S3b). One study only enrolled patients with liver cirrhosis,4 and one focused on the patients who received HSCT.16 Since these two specific groups are relatively small and have unique characteristics, we conducted a subgroup analysis to avoid selection bias that revealed consistent findings with our principal analysis (Supplementary Fig. S3c and S3d).

On the other hand, different AKD definitions were used, although most included studies defined AKD according to the KDIGO consensus.3,4,6,7,9, 10, 11, 12, 13,15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20 Lin et al.14 followed the criteria of the ADQI 16 workshop, and the AKD patients enrolled in the study were identified as successfully weaning from dialysis after an episode of AKI. Fujii et al.22 described a progressive subacute kidney functional impairment which was defined as subacute-acute kidney injury (s-AKI) (Supplementary Fig. S3e) Additionally, 8 of the 21 enrolled studies12,13,15,18, 19, 20, 21,23 included patients whom all had prior AKI before AKD, and three of the 21 studies excluded patients with previous AKI.3,14,22 (Supplementary Fig. S3f and S3g) Additionally, 7 of the 21 enrolled studies included only critically ill patients who admitted to ICU.6,9, 10, 11, 12, 13,15 (Supplementary Fig. S3h) Besides, the total number enrolled in every trial and the baseline characteristic was diverse, so we conducted a subgroup analysis which divided the total number of the trial included into less or more than 1000 patients (Supplementary Fig. S3i). In addition, the baseline characteristics of enrolled patients were also various, we then made a further subgroup analysis for less or more than 20% of the prevalence of DM in the population. The reason that we chose a cut-point of 20% was that the prevalence of DM in the total population was reported from 0 to 41% (Supplementary Fig. S3j).

In subgroup analysis, the patients with AKD without prior AKI had a higher all-cause mortality rate (26.48% versus 7.48%) (OR:3.00, 95% CI 1.70 to 5.31, p < 0.001) and a higher risk of new-onset ESKD (OR:4.96, 95% CI 1.80 to 13.68, p = 0.002) than those without AKD (Fig. 3a and b).

Fig. 3.

Forest plots depicting the comparisons of (a)all-cause mortality and (b) ESKD between the AKD without prior AKI group versus the NKD group. Abbreviations: AKD, Acute kidney disease; AKI, Acute kidney injury; ESKD, End-stage kidney disease; NKD, Non-acute kidney disease.

Heterogeneity and publication bias

The heterogeneities were 99.1% for mortality, 94.9% for ESKD, and 96.7% for the incident and progressive CKD, according to the I2 test. We used subgroup analysis to investigate the possible heterogeneity and there was the similar result by subgroup analysis of ICU admission, previous CKD more or less than 50%, population from a single centre or multiple centres, retrospective or prospective study, with/without surgery, and follow up time more or less than 180 days.

Besides, we used funnel plots to evaluate the possibility of publication bias and the publication bias showed not significant (Supplementary Fig. S4a–4c). The results showed generally symmetrical distributions for all-cause mortality, new-onset ESKD, and incident/progressive CKD (Supplementary Fig. S4a–4c). Regarding all-cause mortality, the meta-regression revealed that the interactions between multiple variables, including age, gender, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and previous CKD were not significant, which enhances the validity of our results (Supplementary Fig. S5a–5e).

Quality and GRADE assessment

We assessed evidence quality by the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale Quality Assessment, which judged studies from three broad perspectives. The score of the NOS for included studies was 4–8 (Supplementary Table S1). We also utilized subgroup analysis to exclude studies with NOS scores less than 7 (Supplementary Fig. S3k). The strength of evidence regarding all-cause mortality and ESKD measured by GRADE revealed moderate certainty (Supplementary Table S2). GRADE has five aspects, including risk of bias, inconsistency, indirectness, imprecision, and publication bias. The level of evidence regarding primary and secondary outcomes measured by GRADE for observational studies was downgraded to moderate due to high inconsistency.

Discussion

In this meta-analysis containing 1,114,012 patients included in 21 studies,3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23 we showed AKD is common in community or hospitalized patients who suffer from AKI and also occurs in patients without prior AKI. Patients with AKD had higher risks of all-cause mortality, ESKD, incident CKD, and progressive CKD than those with NKD. In light of the main finding, there was also a higher mortality rate and higher risk of new-onset ESKD in patients with AKD without prior AKI when compared with their NKD counterparts. This observation was consistent in the subgroup analyses according to prevalent CKD, variable follow-up periods, patient characteristics (surgical patients versus medical patients), and study designs.

In the past, the outcomes of patients after AKI had been largely neglected, but there are specific AKI recovery phenotypes and reversal patterns to long-term outcomes after AKI.25,26 In this systematic review, we showed that 26.11% of patients progressed to AKD after an AKI episode in hospitalized patients in the same index hospitalization. Likewise, the occurrence of AKD is 15.6% in patients after severe malaria-related AKI, 35.9% in patients with AKI after surgery, and nearly 40% among myocardial infarction patients who developed AKI.5,13,27 In light of this, the incidence of AKD ranges from 15.6%–40% among those who ever developed AKI.

Importantly, in our study, the incidence rate of hospital-acquired AKD without a prior AKI episode was 2.11% and with a prior AKI episode was 26.11%. The incidence rate was 4.60% in the patients with a community-acquired AKD. According to other studies, the incidence rate of AKD without prior AKI episode ranges from 17% to 37.8%.5,7,28,29 In general, our reported incidence is far less than previous reports. One reason could be that we enrolled patients with community-acquired AKD.3,4 Further study is warranted to identify the incidence and consequences of community-acquired AKD that is different from inpatient settings.

Early reversal or recovery from an episode of AKI vs. persistent AKI has been consistently associated with a better survival rate.29 Previous studies have shown that the duration of AKI affects mortality.30,31 The longer the duration of AKI, the higher the mortality.30, 31, 32 In addition, AKD (vs. NKD) was associated with increased risk of major adverse kidney events (MAKE), mostly attributed to higher mortality.5,33 Therefore, it is expected patients with AKD to have higher mortality than patients with AKI with early kidney recovery or patients with NKD.

Patients with AKD have a higher incidence of ESKD or CKD progression than the NKD group. Previous animal models of AKI have demonstrated the potential mechanism for post-AKI residual kidney impairment, including interstitial inflammation, sparse capillary, and chronic hypoxia.27 Moreover, the mechanism of CKD progression after AKI includes tubulointerstitial fibrosis and progressive nephron loss.34 The existing injury signalling suggested that AKI will increase oxidative stress and fibrotic markers through aldosterone and induce kidney hypertrophy and glomerulosclerosis, which contributes to CKD.35,36 Taken together, AKD results from renal structural injury, which can trigger a maladaptive repair process and lead to the development and progression of CKD.

This meta-analysis also confirmed that the AKD without prior AKI group was associated with higher mortality than the NKD group. Also, the AKD without prior AKI group had a higher risk of new-onset ESKD or all-cause mortality than the NKD group.

In the patients with subclinical AKI, structural biomarkers representing renal tubular damage may be elevated, but functional biomarkers (i.e. serum creatinine) did not change.37 When patients had recovery from AKI, there was the possibility of subclinical AKI, which was not fit the traditional KDIGO criteria of AKI but with imaging, histologic or biomarker evidence of kidney damage or dysfunction.38 In constant with our findings, patients with AKD without prior AKI often presented with biopsy-proven crescentic glomerulonephritis.39 Therefore, AKD without previous AKI should be noted for the risk of increased mortality rate and ESKD.

In this study, the heterogeneity among included studies was high, which may arise from variations of baseline characteristics of enrolled patients. In light of the main findings, patients with high percentage of baseline CKD, ICU admission, underwent an operation, and study design from prospective cohort or multicenter study analyses showed similar findings suggesting that the AKD group was associated with higher risk of mortality and new-onset ESKD than the NKD group.

In our study, we showed that patients with AKD had higher risks of all-cause mortality, ESKD, incident CKD, and progressive CKD than those with NKD. Therefore, applying these findings to clinical practice, it is necessary to follow-up on eGFR and albuminuria closely and recognize the cause of AKD while AKD is diagnosed. Additionally, an appropriate post-AKD bundle should be taken into consideration.2,40,41

This is the first systematic review and meta-analysis summarizing the association of AKD with long-term mortality and ESKD. Moreover, most of the studies we identified were published in the past three years, indicating that AKD epidemiology is a relatively new concept; therefore, our findings may provide clinical guidance. For our TSA analysis, since the Z-curve crossed the conventional boundary for statistical significance, the trial sequential monitoring boundary, and the RIS, we could confirm that the existing evidence is sufficient to make a rigorous conclusion that patients with AKD had a consistently higher mortality risk than NKD patients. Moreover, based on the results from TSA analysis, it would be unlikely for future studies to alter our conclusion. Third, we evaluated the most essential and credible outcome of in-hospital mortality as our primary outcome in this review. Fourth, we have nearly ascertained all the detailed data from the original studies to make the meta-analysis more comprehensive. Finally, the fundamental strength of our meta-analysis lies in its large sample size and comprehensive search.

However, there are some limitations in this study that should be addressed. First, some studies did not use the standard AKD definition. Second, there is a high degree of statistical heterogeneity among the included studies, limiting the validity of the point estimates and confidence intervals. However, we reported several essential findings in subgroup analyses to facilitate generalizability. Third, some studies had only a short follow-up (4 weeks–90 days). This could potentially underestimate the incidence of AKD and introduce indication bias or ascertainment bias since patients in the hospital or already discharged could still develop AKD up to 90 days post-AKI. Such being the case, our subgroup analysis showed that the association between AKD and mortality is consistent in various subgroup analyses. Fourth, the difference in diverse follow-up period may be the cause of heterogeneity but there was similar result by extracting proportion data (OR), time-variant data (HR), and subgroups with cutting follow-up time by 180 days to investigate the ascertainment bias. Fifth, 14 studies4,5,7,11,13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22 were scored less than seven by NOS. According to the NOS score, we showed consistency with our main findings that AKD associated with increased mortality rates than NKD. Finally, although there was high heterogeneity across the enrolled studies due to diverse study designs and different definitions of AKD and follow-up periods, we acknowledge that our conclusions are in line with our main findings.

On the other hand, 7 of the 21 enrolled studies assessed the outcomes of the patients with AKD without prior AKI. However, the patients in whom baseline eGFR was unknown were not excluded in James et al.3 This may lead to the misclassification of CKD as AKD and overestimate the prevalence for AKD. About 10% of the patients with AKD had no preceding eGFR or creatinine measurement in James et al.3 The patients with AKI or AKD tended to be hospitalized and have follow-up eGFR testing in James et al.3 So it may increase the opportunity to detect CKD in the cohort.3 Taking together, because of the heterogeneity of the included studies, further researches concerning the different population is necessary to comprehensively investigate the outcomes of AKD patients.

In conclusion, AKD is common in community or hospitalized patients who suffer from AKI and also occurs in patients without prior AKI. This meta-analysis demonstrated that the AKD group had a higher risk of all-cause mortality, new-onset ESKD, incident, and progressive CKD risk than the NKD group. We also demonstrated a higher mortality rate, and new-onset ESKD in patients with AKD without prior AKI group than the NKD group.

Contributors

VCW chaired the group, conceived and made the conceptualization, and project administration of the study. CCS, JYC, YTC, CKH and CHC contributed to data curation and verified the underlying data. CCS and JYC conducted a literature search, and statistical analysis and wrote the manuscript. SYC performed a literature search, statistical analysis, wrote the manuscript, and performed a critical revision of the manuscript. JYC performed a literature search, summary and he also had an investigation and methodology. CCS registered the PROSPERO. CCS and JYC wrote the manuscript and performed a critical review of the manuscript. VCW performed the statistical analysis by CMA and contributed to data interpretation, and critical revision of the manuscript. JYC and HCP made figures with appropriate visualization. SYC performed the statistical analysis by TSA and contributed to data interpretation. Finally, JAN, RM,EN,ES, MHR reviewed and edited this manuscript comprehensively. VCW and CCS funded acquisition. CCS, JYC, SYC, CCS, JAN, RM, EN, ES, YTC, CKH, HCP, CHC, MHR and VCW contributed to subsequent drafts and examined the paper.

Data sharing statement

All extracted and calculated data are available by emailing to the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Acknowledgements

The authors greatly appreciate the Second Core Lab in National Taiwan University Hospital for technical assistance. This study was supported by Ministry of Science and Technology (MOST) of the Republic of China (Taiwan) [grant number, MOST 107-2314-B-002-026-MY3, 108-2314-B-002-058, 110-2314-B-002-241, 110-2314-B-002-239], National Science and Technology Council (NSTC) [grant number, NSTC 109-2314-B-002-174-MY3, 110-2314-B-002-124-MY3, 111-2314-B-002-046, 111-2314-B-002-058], National Health Research Institutes [PH-102-SP-09], National Taiwan University Hospital [109-S4634, PC-1246, PC-1309, VN109-09, UN109-041, UN110-030, 111-FTN0011] Grant MOHW110-TDU-B-212-124005, Mrs. Hsiu-Chin Lee Kidney Research Fund and Chi-mei medical center CMFHR11136. JAN is supported, in part, by grants from the National Institute of Health, NIDDK (R01 DK128208 and P30 DK079337) and NHLBI (R01 HL148448-01).

Footnotes

Supplementary data related to this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eclinm.2022.101760.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

References

- 1.Chawla L.S., Bellomo R., Bihorac A., et al. Acute kidney disease and renal recovery: consensus report of the Acute Disease Quality Initiative (ADQI) 16 Workgroup. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2017;13(4):241–257. doi: 10.1038/nrneph.2017.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lameire N.H., Levin A., Kellum J.A., et al. Harmonizing acute and chronic kidney disease definition and classification: report of a kidney disease: improving global outcomes (KDIGO) consensus conference. Kidney Int. 2021;100(3):516–526. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2021.06.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.James M.T., Levey A.S., Tonelli M., et al. Incidence and prognosis of acute kidney diseases and disorders using an integrated approach to laboratory measurements in a universal health care system. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(4) doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.1795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tonon M., Rosi S., Gambino C.G., et al. Natural history of acute kidney disease in patients with cirrhosis. J Hepatol. 2021;74(3):578–583. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2020.08.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chang C.H., Chen S.W., Chen J.J., et al. Incidence and transition of acute kidney injury, acute kidney disease to chronic kidney disease after acute type A aortic dissection surgery. J Clin Med. 2021;10(20) doi: 10.3390/jcm10204769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hsu C.K., Wu I.W., Chen Y.T., et al. Acute kidney disease stage predicts outcome of patients on extracorporeal membrane oxygenation support. PLoS One. 2020;15(4) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0231505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.See E.J., Polkinghorne K.R., Toussaint N.D., Bailey M., Johnson D.W., Bellomo R. Epidemiology and outcomes of acute kidney diseases: a comparative analysis. Am J Nephrol. 2021;52(4):342–350. doi: 10.1159/000515231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen J.J., Lee T.H., Kuo G., et al. Acute kidney disease after acute decompensated heart failure. Kidney Int Rep. 2022;7(3):526–536. doi: 10.1016/j.ekir.2021.12.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen Y.T., Jenq C.C., Hsu C.K., et al. Acute kidney disease and acute kidney injury biomarkers in coronary care unit patients. BMC Nephrol. 2020;21(1):207. doi: 10.1186/s12882-020-01872-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Flannery A.H., Li X., Delozier N.L., et al. Sepsis-associated acute kidney disease and long-term kidney outcomes. Kidney Med. 2021;3(4):507–514.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.xkme.2021.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fuhrman D.Y., Nguyen L., Joyce E.L., Priyanka P., Kellum J.A. Outcomes of adults with congenital heart disease that experience acute kidney injury in the intensive care unit. Cardiol Young. 2021;31(2):274–278. doi: 10.1017/S1047951120003923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gameiro J., Carreiro C., Fonseca J.A., et al. Acute kidney disease and long-term outcomes in critically ill acute kidney injury patients with sepsis: a cohort analysis. Clin Kidney J. 2021;14(5):1379–1387. doi: 10.1093/ckj/sfaa130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kofman N., Margolis G., Gal-Oz A., et al. Long-term renal outcomes and mortality following renal injury among myocardial infarction patients treated by primary percutaneous intervention. Coron Artery Dis. 2019;30(2):87–92. doi: 10.1097/MCA.0000000000000678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lin Y.F., Lin S.L., Huang T.M., et al. New-onset diabetes after acute kidney injury requiring dialysis. Diabetes Care. 2018;41(10):2105–2110. doi: 10.2337/dc17-2409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Matsuura R., Iwagami M., Moriya H., et al. The clinical course of acute kidney disease after cardiac surgery: a retrospective observational study. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):6490. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-62981-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mima A., Tansho K., Nagahara D., Tsubaki K. Incidence of acute kidney disease after receiving hematopoietic stem cell transplantation: a single-center retrospective study. PeerJ. 2019;7:e6467. doi: 10.7717/peerj.6467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mizuguchi K.A., Huang C.C., Shempp I., Wang J., Shekar P., Frendl G. Predicting kidney disease progression in patients with acute kidney injury after cardiac surgery. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2018;155(6):2455–2463.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2018.01.093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Peerapornratana S., Priyanka P., Wang S., et al. Sepsis-associated acute kidney disease. Kidney Int Rep. 2020;5(6):839–850. doi: 10.1016/j.ekir.2020.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Xiao Y.Q., Cheng W., Wu X., et al. Novel risk models to predict acute kidney disease and its outcomes in a Chinese hospitalized population with acute kidney injury. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1) doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-72651-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yan P., Duan X.J., Liu Y., et al. Acute kidney disease in hospitalized acute kidney injury patients. PeerJ. 2021;9 doi: 10.7717/peerj.11400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Marques F., Gameiro J., Oliveira J., et al. Acute kidney disease and mortality in acute kidney injury patients with COVID-19. J Clin Med. 2021;10(19) doi: 10.3390/jcm10194599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fujii T., Uchino S., Takinami M., Bellomo R. Subacute kidney injury in hospitalized patients. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2014;9(3):457–461. doi: 10.2215/CJN.04120413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang H., Lambourg E., Guthrie B., Morales D.R., Donnan P.T., Bell S. Patient outcomes following AKI and AKD: a population-based cohort study. BMC Med. 2022;20(1):229. doi: 10.1186/s12916-022-02428-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ostermann M., Bellomo R., Burdmann E.A., et al. Controversies in acute kidney injury: conclusions from a kidney disease: improving global outcomes (KDIGO) conference. Kidney Int. 2020;98(2):294–309. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2020.04.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ronco C., Rosner M.H. Acute kidney injury and residual renal function. Crit Care. 2012;16(4):144. doi: 10.1186/cc11426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ronco C., Ferrari F., Ricci Z. Recovery after acute kidney injury: a new prognostic dimension of the syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2017;195(6):711–714. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201610-1971ED. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Namazzi R., Batte A., Opoka R.O., et al. Acute kidney injury, persistent kidney disease, and post-discharge morbidity and mortality in severe malaria in children: a prospective cohort study. EClinicalMedicine. 2022;44 doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2022.101292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Moledina D.G., Luciano R.L., Kukova L., et al. Kidney biopsy-related complications in hospitalized patients with acute kidney disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2018;13(11):1633–1640. doi: 10.2215/CJN.04910418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kellum J.A., Sileanu F.E., Bihorac A., Hoste E.A., Chawla L.S. Recovery after acute kidney injury. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2017;195(6):784–791. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201604-0799OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pannu N., James M., Hemmelgarn B., Klarenbach S. Association between AKI, recovery of renal function, and long-term outcomes after hospital discharge. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2013;8(2):194–202. doi: 10.2215/CJN.06480612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brown J.R., Kramer R.S., Coca S.G., Parikh C.R. Duration of acute kidney injury impacts long-term survival after cardiac surgery. Ann Thorac Surg. 2010;90(4):1142–1148. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2010.04.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Uchino S., Bellomo R., Bagshaw S.M., Goldsmith D. Transient azotaemia is associated with a high risk of death in hospitalized patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2010;25(6):1833–1839. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfp624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chen S.Y., Chen J.Y., Huang W.C., et al. Cardiovascular outcomes and all-cause mortality in primary aldosteronism after adrenalectomy or mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist treatment: a meta-analysis. Eur J Endocrinol. 2022;187(6):S47–S58. doi: 10.1530/EJE-22-0375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gameiro J., Marques F., Lopes J.A. Long-term consequences of acute kidney injury: a narrative review. Clin Kidney J. 2021;14(3):789–804. doi: 10.1093/ckj/sfaa177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sharma N., Anders H.J., Gaikwad A.B. Fiend and friend in the renin angiotensin system: an insight on acute kidney injury. Biomed Pharmacother. 2019;110:764–774. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2018.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chan C.K., Huang Y.S., Liao H.W., et al. Renin-Angiotensin-aldosterone system inhibitors and risks of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 infection: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hypertension. 2020;76(5):1563–1571. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.120.15989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ronco C., Kellum J.A., Haase M. Subclinical AKI is still AKI. Crit Care. 2012;16(3):313. doi: 10.1186/cc11240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Neyra J.A., Chawla L.S. Acute kidney disease to chronic kidney disease. Crit Care Clin. 2021;37(2):453–474. doi: 10.1016/j.ccc.2020.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chen S., Tang Z., Xiang H., et al. Etiology and outcome of crescentic glomerulonephritis from a single center in China: a 10-year review. Am J Kidney Dis. 2016;67(3):376–383. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2015.07.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wu V.C., Chueh J.S., Chen L., et al. Nephrologist follow-up care of patients with acute kidney disease improves outcomes: taiwan experience. Value Health. 2020;23(9):1225–1234. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2020.01.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pan H.C., Chen Y.Y., Tsai I.J., et al. Accelerated versus standard initiation of renal replacement therapy for critically ill patients with acute kidney injury: a systematic review and meta-analysis of RCT studies. Crit Care. 2021;25(1):5. doi: 10.1186/s13054-020-03434-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.