Abstract

In current literature, there is uncertainty in the pathophysiology and management of influenza-associated Acute Necrotizing Encephalitis. Because of this and the rarity of the disease, no clear treatment guidelines exist. It is thought that treatment after 24 h of symptom onset or known brainstem involvement are poor predictors of outcome. Here, we present a case that provides support for aggressive management of the inflammatory cascade with combination high-dose steroid, immunoglobulin, and anti-viral therapy with oseltamivir despite initiation after 24 h from symptom onset, brainstem involvement, and a pathogenic RANBP2 gene mutation which mechanistically increases oxidative stress, cytokine effects, and possibly viral invasion into brain tissue and vasculature.

Keywords: encephalitis, cognition, children, autoimmune

Introduction

Case Presentation

An 8-year-old previously healthy Caucasian male was evaluated at an outside emergency department after 2 weeks of cough and five days of fever, emesis, headache, and >24 h of progressively worsening altered mental status and confusion. Two days prior to presentation, rapid influenza testing was negative. Due to worsening lethargy and significant confusion, he was taken to an outside facility where repeat testing was positive for Influenza B. A head CT was performed that showed signal hypodensities in the bilateral basal ganglia. Leukopenia was the only abnormality detected in initial hematology and biochemical studies. Empiric treatment with ceftriaxone, vancomycin, acyclovir, and oseltamivir was provided prior to transfer.

He was encephalopathic on arrival with eye opening only to verbal stimuli, inability to follow commands, and no verbal output. Cranial nerve function was intact. He retained anti-resistance strength but did not localize to painful stimuli. He was hyperreflexic with ankle clonus and extensor plantar responses. Autonomic function was preserved.

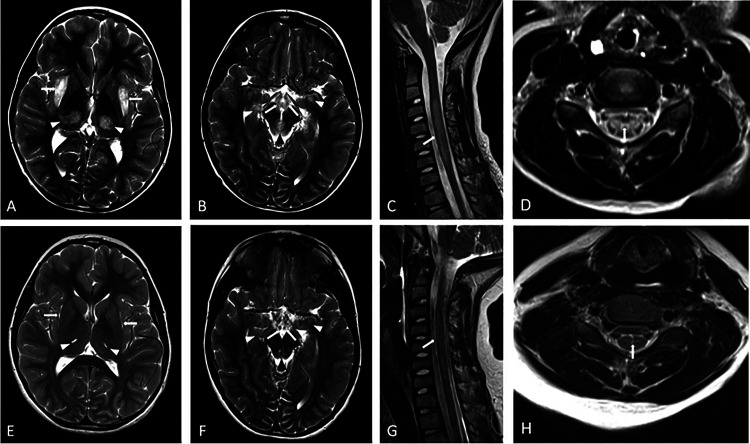

Brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) with and without IV contrast was performed which showed characteristic symmetric T2 prolongation and restricted diffusion within the thalami, external capsule, mammillary bodies, mesial temporal lobes and the brainstem (Figure 1). A cervical spine MRI with and without contrast was also performed which revealed an expansile central non-enhancing increased T2 signal extending from C3-C6 consistent with myelitis (Figure 1). CSF analysis revealed 20 red blood cells per mm3, <1 nucleated cell per mm3, normal glucose of 59 mg/DL, and elevated protein of 67.5 mg/DL. CSF Gram stain, enterovirus, and HSV 1 & 2 PCR were negative.

Figure 1.

MRI brain findings of acute necrotizing encephalopathy caused by a RANBP2 mutation (ANE1) at the time of presentation (top row) and at 3 month follow up (bottom row). Symmetric T2 hyperintensity and swelling of the external capsules (A- white arrows), thalami (A-white arrowheads), mammillary bodies (B- white arrows), mesial temporal lobes (B- white arrowheads) and midbrain (B-black arrowhead) are seen on axial T2 weighted images on the brain (A and B). Sagittal (C) and axial (D) T2 weighted MRI of the cervical spine show expansile T2 hyperintensity extending from C3 to C6 levels (C- white arrow) primarily involving the central gray matter (D- white arrow). 3 month follow up axial T2 weighted images of the brain (E and F) and sagittal (G) and axial (H) T2 weighted MRI of the cervical spine show resolution of areas of edema and swelling with small areas of gliosis and volume loss.

Due to the suspected diagnosis of influenza related ANE, high dose methylprednisolone (30 mg/kg/day) was initiated and continued for five days followed by an eight-week steroid taper. IVIG (1 g/kg) every 24 h was given for two total doses (total dose of 2 g/kg) and euthermia was aggressively maintained. Broad spectrum antibiotics were discontinued after no growth on cultures for 48 h. Oseltamivir (60 mg BID; 4.4 mg/kg/day) was continued for total of ten days. Continuous electroencephalography (EEG) performed for 24 h was significant for diffuse slowing consistent with a moderate encephalopathy without epileptiform abnormalities. During the first 24 h after admission his neurologic examination deteriorated. On day two of admission, his mental status improved slightly, and he regained the ability to open his eyes to voice. On day four, purposeful spontaneous limb movement and movement to commands were noted. He was extubated on day seven and continued to slowly improve over the subsequent two-week period before discharge to a rehabilitation facility. At discharge, he was answering simple questions and following commands. Language was fluent and cogent. Strength testing showed in plane arm movements and full strength in the legs. Neither sensory abnormalities nor ataxia were noted. Reflexes were normal in his arms and remained brisk in his legs.

He participated in three weeks of intensive inpatient rehabilitation followed by twice weekly outpatient physical therapy and occupational therapy. A three month follow up MRI of the brain and cervical spine showed resolution of the previously seen areas of abnormal signal intensity with residual volume loss and gliosis (Figure 1). RANBP2 gene testing was performed revealing a pathogenic variant (c.1754C>T [p.Thr585Met]).

At one-year follow-up neuropsychological evaluation showed average general intellectual function (WISC-V GAI = 95; Full Scale IQ 89) with relative strengths in fluid reasoning skills and complex visual-spatial skills (high average) and relative weaknesses in expressive language, memory for auditory/verbal information (borderline). Academic achievement testing revealed impaired processing speed (WISC-V Processing Speed Index SS = 69-2%; CPT-3 HRT T-score = 66). Social, emotional, and behavioral functioning was impacted with parental reported clinically elevated emotional control and emotional regulation index (BRIEF-2). The patient reported functional problems and ineffectiveness (CDI-2 Scales; high average T-scores) and very elevated scores on the General Anxiety Disorder Index, panic, and tense/restless symptoms (MASC-2 Scales). Overall, it was felt that he had mild neurocognitive disorder due to ANE and an adjustment disorder with mixed anxiety and depressed mood from his experiences. The information gained from his neuropsychological evaluation was incorporated into his individualized education plan (IEP). The subsequent school year, he remained in regular education classes doing grade-level work while achieving awards of academic excellence. The patient was followed up at a 3 years following initial presentation and had maintained his normal neurologic baseline.

History

Acute Necrotizing Encephalopathy (ANE) was first described in 1995 in a series of otherwise healthy Japanese children presenting with a novel acute encephalopathy after upper respiratory infection. This disease was characterized by multiple symmetric necrotic brain lesions, proteinaceous cerebral spinal fluid (CSF), and necropsy showing regionalized breakdown of the blood-brain barrier without direct viral invasion of the central nervous system (CNS).1 Given the necrotic brain lesions and laboratory findings, a wide differential diagnosis of acute disseminated encephalomyelitis, Leigh disease and other metabolic conditions should be considered in cases of suspected ANE.2 In retrospect, it is likely the first unrecognized cases were reported in Japan in the late 1970s after the advent of computed tomography (CT) imaging.3 Additional case series in the 1990s provided support for the existence of ANE and linked it to an influenza epidemic in Japan.4,5

Pathogenesis

The pathogenesis of ANE remains unclear. Due to lack of evidence of direct viral invasion of the CNS, it has been postulated that influenza outside of the CNS triggers a strong inflammatory cascade leading to high levels of cytokines resulting in blood-brain barrier breakdown and subsequent necrosis.6,8 Other infections such as parainfluenza, HHV-6, rotavirus and mycoplasma have been reported to cause a similar clinical and imaging pattern thus supporting the theory that the immune response rather than the pathogen is responsible for the disease process.9,12 There are contradictory reports of direct observation of influenza virus in the brain tissue or CSF of ANE diagnosed patients in the absence of a widespread systemic inflammatory response.13,15

Genetics

Most ANE cases are thought to be sporadic, but there are familial and recurrent cases noted in European and Caucasian patients attributed to mutations in the RANBP2 gene located on chromosome 2q11-13. This gene encodes the nuclear pore of Ran binding protein 2 which facilitates protein importation and exportation, intracellular trafficking, and energy maintenance.16,17 These mutations may impact the development of ANE through mitochondrial dysfunction leading to increased oxidative stress, dysregulation of cytokine signaling, and increased susceptibility to viral CNS vascular invasion.18,19 In addition to typical MRI findings, patients with associated RANBP2 mutations may have more disseminated findings including myelitis.20

Symptoms

The clinical findings of ANE are broad. There is typically an inciting virus which produces prodromal symptoms such as cough, fever, skin exanthems, diarrhea and vomiting.2 This prodromal stage is then followed by acute encephalopathy hallmarked by seizures, focal neurologic deficits and profound disturbances of consciousness.2 For those who develop ANE and survive, the recovery stage usually consists of continued neurologic deficits although there are reports of patients who make a full recovery.2

Treatment

Corticosteroids, intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG), and antivirals have all been used as treatments.21 In patients without brainstem lesions, steroid use <24 h from onset of symptoms has been reported to have a statistically significant correlation with better outcomes while IVIG was not correlated with an outcome difference.22 There is some evidence that outcomes are poor if brainstem lesions are present and if high-dose steroid therapy is started >24 h from onset of symptoms.22,23 Neuraminidase inhibitors such as Oseltamivir have been used with success in influenza infections with significant complications or neurologic signs and in at least one adult case of ANE with observed benefit.13,24,25

Discussion

Despite the presence of the previously described poor prognostic factors including presentation >24 h after onset of altered mental status and having brainstem involvement, our patient had a favorable neurologic outcome. This is contradictory to previous findings where brainstem involvement irrespective of steroid use or timing of administration had a poor outcome in 13/15 patients and death in 8/15.13 Due to the uncertainty on the pathophysiology and management of ANE in the available literature, it was decided to combine several mechanistic interventions in hopes of maximizing potential benefit. Myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein testing was unavailable at the time of this diagnosis, although is now critical in the workup of suspected cases to help differentiate between ANE and ADEM. High-dose methylprednisolone and IVIG were used to target the inflammatory and cytokine cascade. Given his improvement, a prolonged corticosteroid taper was used. Despite absence of fulminant organ involvement outside of the CNS, oseltamivir was used early in the clinical course in hopes of managing brain tissue or vascular invasion of the influenza virus.

Due to a limited number of patients presenting with ANE, it is likely that case reports and retrospective reviews will largely guide management. Although singular, this case provides evidence that aggressive management of the inflammatory cascade with combination high-dose corticosteroid, immunoglobulin, and anti-viral therapy with oseltamivir may provide significant clinical benefit even in patients presenting > 24 h from symptom onset and with brainstem involvement. It may also be considered evidence that aggressive management of the inflammatory cascade with anti-viral therapy may improve outcomes in those with a pathogenic RANBP2 gene mutation which mechanistically increases oxidative stress, cytokine effects, and possibly viral invasion into brain tissue and vasculature.18,19 Additional reports have noted favorable outcomes with aggressive modulation of the inflammatory cascade using an interleukin 6 blocking agent.25 Further studies are needed to determine the optimal use of anti-inflammatory interventions as well as anti-viral agents in the treatment of ANE.

RANBP2 mutations continue to be associated with cases of ANE. Genetics studies have revealed that the genetic mutations follow a heterogeneous clinical course and not all individuals who have the genetic mutation will develop ANE.26 There have been case reports of ANE reported after vaccination to influenza, parainfluenza, HHV, Varicella, and DTP.26 Additionally, there have been described cases of individuals with ANE who have underwent immunizations with no further symptoms. Further research is needed in this area. In any individual with a history of AnE who develops a subsequent attack- or in individuals with a family history- early initiation of therapy with steroids should be considered strongly. Follow up neuropsychological testing and MRI are reasonable studies to consider after ANE, although further research is needed to guide timing and the yield and meaning of these tests.

Acknowledgements

Thank you to the patient and family for their support of this manuscript.

Abbreviations

- ANE

Acute Necrotizing Encephalopathy

- CSF

cerebral spinal fluid

- CNS

central nervous system

- CT

computed tomography

- IVIG

intravenous immunoglobuli

- MRI

Magnetic resonance imaging

- EEG

electroencephalography

- LP

lumbar puncture

- PCR

polymerase chain reaction

Contributors’ Statement Page: Dr Galan participated in the care of the patient and was the primary author of the manuscript.

Dr Nordli revised the manuscript.

Dr Yazdani participated in the care of the patient and provided the images and descriptions for the manuscript.

Dr Klein participated in the care of the patient and reviewed and revised the manuscript as needed.

All authors approved the final manuscript as submitted and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Publication made possible in part by support from the Nemours Grant for Open Access from Library Services.

Table of Contents Summary: Reporting a favorable outcome in RANBP2 mutation associated acute necrotizing encephalitis with combination methylprednisolone, intravenous immunoglobulin, and a neuraminidase inhibitor despite late initiation.

ORCID iD: Douglas R. Nordli https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3995-5467

References

- 1.Mizuguchi M, Abe J, Mikkaichi K, et al. Acute necrotising encephalopathy of childhood: A new syndrome presenting with multifocal, symmetric brain lesions. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry. 1995;58:555‐561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wu X, Wu W, Pan W, Wu L, Liu K, Zhang H-L. Acute Necrotizing Encephalopathy: An Underrecognized Clinicoradiologic Disorder. Mediat Inflamm. 2015;2015, Article ID 792578, 10 pages, 2015. 10.1155/2015/792578 2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mizuta R, Izumi H, Takeuchi S, et al. A case of reye’s syndrome with elevation of influenza A, CF antibody. Japanese Journal of Pediatrics. 1979;32:2144‐2149. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mizuguchi M. Acute necrotizing encephalopathy of childhood: A novel form of acute encephalopathy prevalent in Japan and Taiwan. Brain and Development. 1997;19(2):81‐92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Morishima T, Togashi T, Yokota S, et al. Encephalitis and encephalopathy associated with an influenza epidemic in Japan. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2002;35:5:512‐517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mizuguchi M, Yamanouchi H, Ichiyama T, Shiomi M. Acute encephalopathy associated with influenza and other viral infections. Acta Neurologica Scandinavica. Supplementum. 2007;186:45‐56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Toovey S. Influenza-Associated central nervous system dysfunction: A literature review. Travel Medicine and Infectious Disease. 2008;6(3):114‐124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ichiyama T, Endo S, Kaneko M, et al. Serum cytokine concentrations of influenza-associated acute necrotizing encephalopathy. Pediatrics International. 2003;45(6):734‐736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kim YN, You SJ. A case of acute necrotizing encephalopathy associated with parainfluenza virus infection. Korean Journal of Pediatrics. 2012;55(4):147‐150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hoshino A, Saitoh M, Oka A, et al. Epidemiology of acute encephalopathy in Japan, with emphasis on the association of viruses and syndromes. Brain & Development. 2012;34(5):337‐343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ashtekar CS, Jaspan T, Thomas D, et al. Acute bilateral thalamic necrosis in a child with Mycoplasma pneumoniae. Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology. 2003;45(3):634‐637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee KH, McKie VS, Sekul EA, et al. Unusual encephalopathy after acute chest syndrome in sickle cell disease: Acute necrotizing encephalitis. Journal of Pediatric Hematology/Oncology. 2002;24(7):585‐588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Alsolami A, Shiley K. Successful treatment of influenza-associated acute necrotizing encephalitis in an adult using high-dose oseltamivir and methylprednisolone: Case report and literature review. Open Forum Infectious Diseases. 2017;4(3):1‐5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fujimoto S, Kobayashi M, Uemura O, et al. PCR On cerebrospinal fluid to show influenza-associated acute encephalopathy or encephalitis. Lancet. 1998;352:873‐875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Simon M, Hernu R, Cour M, et al. Fatal influenza A(H1N1)pdm09 encephalopathy in immunocompetent man. Emerging Infectious Diseases. 2013;19:1005‐1007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Neilson DE, Adams CM, Orr DK, et al. Infection-triggered familial or recurrent cases of acute necrotizing encephalopathy caused by mutations in a component of the nuclear pore, RANBP2. Am J Hum Genet. 2009;84:44‐51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Singh RR, Sedani S, Lim M, et al. RANBP2 Mutation and acute necrotizing encephalopathy: 2 cases and a literature review of the expanding clinic-radiological phenotype. European Journal of Paediatric Neurology. 2015;19:106‐113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Neilson DE. The interplay of infection and genetics in acute necrotizing encephalopathy. Current Opinion in Pediatrics. 2010;22(6):751‐757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yao D, Kuwajima M, Chen Y, et al. Impaired long-chain fatty acid metabolism in mitochondria causes brain vascular invasion by a nonneurotropic epidemic influenza-A virus in the newborn/suckling period: Implications for influenza-associated encephalopathy. Molecular and Cellular Biochemistry. 2007;299:85‐92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wolf K, Schmitt-Mechelke T, Kollias S, Curt A. Acute necrotizing encephalopathy (ANE1): Rare autosomal-dominant disorder presenting as acute transverse myelitis. Journal of Neurology. 2013;260(6):1545‐1553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Morishima T, Yokota S. Special therapy of influenza encephalitis/encephalopathy: A proposal. Yokohama: Committee on the Treatment of Influenza Encephalitis/Encephalopathy. 2000;1:34. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Okumura A, Mizuguchi M, Kidokoro H, et al. Outcome of acute necrotizing encephalopathy in relation to treatment with corticosteroids and gammaglobulin. Brain Dev. 2009;31(3):221‐227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mizuguchi M, Iai M, Takashima S. Acute necrotizing encephalopathy of childhood: Recent advances and future prospects. No To Hattatsu. 1998;30:189‐196. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cooper NJ, Sutton AJ, Abrams KR, et al. Effectiveness of neuraminidase inhibitors in treatment and prevention of influenza A and B: Systemic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Br Med J. 2003;326:1235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kwon S, Kim S, Cho MH, Seo H. Neurologic complications and outcomes of pandemic (H1N1) 2009 in Korean children. Journal of Korean Medical Science. 2012;27:402‐407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Martin A, Reade EP. Acute necrotizing encephalopathy progressing to brain death in a pediatric patient with novel influenza A (H1N1) infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;50(8), e50−e52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]