Abstract

Background

Fatigue is a frequently reported symptom of Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD), having a negative impact on Health-Related Quality of Life (HRQoL). Patients’ experiences of this have not been researched in IBD.

Methods

Semi-structured interviews were conducted with adults with Crohn’s Disease from out-patient clinics in the United Kingdom. Interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim, then analysed using thematic analysis.

Results

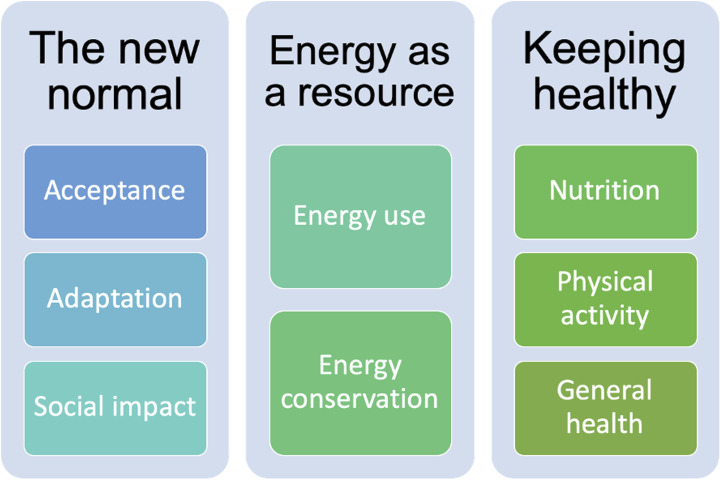

Fourteen participant interviews were conducted. Three key themes were identified: 1) ‘The new normal’ established through adaptation and acceptance; 2) ‘Energy as a resource’ describing attempts to better manage fatigue through planning and prioritising tasks; 3) ‘Keeping healthy’ encompasses participants’ beliefs that ‘good health’ allows better management of fatigue.

Conclusion

Participants establish a ‘new’ normality, through maintaining the same or similar level of employment/education activities. However, this is often at the expense of social activities. Further research is required to explore patient led self-management interventions in IBD fatigue.

Keywords: Crohn’s disease, fatigue, health related quality of life, inflammatory bowel disease, interview

Introduction

Fatigue related to Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD) and other long term conditions (LTCs) is defined as an ‘extreme and persistent sense of tiredness, weakness or exhaustion’ (Dittner et al., 2004) which can be physical, mental or both and is not easily resolved by sleep or rest (Arnett and Clark, 2012; Dittner et al., 2004). The International Classification of Diseases code presents fatigue as an assortment of physical, cognitive and emotional symptoms affecting undertaking of daily tasks (Haney et al., 2015).

Prevalence of IBD fatigue is reported as 41–48% for patients in remission and as high as 71–86% for patients with active disease (Czuber-Dochan et al., 2013). IBD fatigue is one of the top five research priorities highlighted by the Nurses European Crohn’s and Colitis Organisation (N-ECCO), and a top 10 research priority identified through the James Lind alliance (Dibley et al., 2017; Hart et al., 2017; Mowat et al., 2011). Recently, the symptom of fatigue in LTCs has received greater attention as part of overall Health-Related Quality of Life (HRQoL) (Swain, 2000). However, to date, there has been no specific consideration of the impact of IBD fatigue on an individual’s HRQoL.

The aim of this interview study is to explore patient experiences of IBD fatigue and its impact on HRQoL. Undertaking this work will highlight areas for future research focus, by emphasising areas of daily life that are most impacted by IBD fatigue, and have the most negative impact on HRQoL. This will allow us to better understand and design interventions to improve the lives of people living with IBD.

Health-Related Quality of Life

Increasing life expectancy has highlighted the need for other measures of health, capturing the quality of the years someone lives. IBD is incurable and, owing to the physical and psychological impact of the disease, significantly reduces patients’ HRQoL (Huppertz-Hauss et al., 2015). The concept of quality of life (QoL) is not a new one, in 1995 the World Health Organization (WHO) recognised the importance of improving people’s QoL (‘The World Health Organization quality of life assessment (WHOQOL): Position paper from the World Health Organization, 1995). When QoL in considered in the context of health and disease, it is commonly referred to as HRQoL to differentiate from other aspects of QoL. Health is a multi-dimensional concept; HRQoL is also multi‐dimensional and incorporates areas related to physical, mental and social functioning (Ferrans, 2005). HRQoL goes beyond the direct measures of health and focuses on the QoL consequences of health status. HRQoL represents the functional effect of an illness and its consequent therapy upon a patient, as perceived by the patient. It encompasses several dimensions of life, including physical functioning, psychosocial functioning, role functioning, mental health and general health perceptions. HRQoL is determined by socio-demographic, clinical and psychological and treatment-related determinants (Cohen, 2002; Diener and Seligman, 2018; Peyrin-Biroulet, 2010). Clinicians and public health officials use HRQoL to measure the impact of chronic illness. Additionally National Institutes of Health, for example, Cancer Institute, have included evaluation and improvement of HRQoL as a public health priority (Diener and Seligman, 2018).

This is the first interview study if its kind to specifically focus on the impact of IBD fatigue on the HRQoL of adults living with IBD fatigue. This work will complement previous and ongoing work in similar areas and will highlight areas of focus for future research in the understanding of IBD fatigue.

Methods

A qualitative semi-structured interview study utilising thematic analysis (Braun and Clarke, 2006) was chosen.

Interviews are amongst the most accustomed way of collecting qualitative data. Interviews are best suited to collecting information regarding people’s understanding, perceptions and experiences (DiCicco-Bloom and Crabtree, 2006; Flick, 2009). Interviews were organised around a set of pre-determined, open ended, questions, with other questions emerging from the dialogue of the interview. Interviews were conducted in this manner to gain greater clarification through exploration of detailed descriptions of the study’s topic from participants (Miller and Crabtree, 1992). Reflective questioning was used to allow deviation from the interview schedule to pursue topics guided by the participants (Agee, 2009; Lee and Barnett, 1994).

All interviews were conducted by the same researcher (SR). This was an important step in reducing the risk of bias. Interviews were digitally audio-recorded and later transcribed verbatim by the same author. To maintain confidentiality, with no loss of contextual data, information containing identifiable data, such as names of individuals or places, were replaced with general or explanatory terms in square brackets (Wiles et al., 2007). Given the substantial dataset generated from the study, coding and organisation of the data were conducted within NVivo 12 software. Transcripts were coded line-by-line, assigning sections of data to a code which summarised the material according to what each extract revealed.

The researchers assumed a critical realist position (Nightingale and Cromby, 1999) and recognising the research team as an active part of the research process, aware of the importance of considering the influence of individual experiences (including contact with participants and patients) in the shaping of the study and interpretation of the results (Bhaskar, 2013). This was chosen as the epistemological stance as it best fits the exploration of participant beliefs and experiences in constructing the understanding of the impact of IBD fatigue on the HRQoL of adults with IBD. The distinctive feature of this form of realism is the denial that there is objective or certain knowledge of the world, and the researcher should accept the possibility of alternative valid accounts of any phenomenon.

Sample size and recruitment strategy

Using guidance from literature regarding qualitative sampling and previous research considering similar cohorts, an initial sample size of 20 participants was chosen (Ritchie and Lewis, 2003; Silverman and Silverman, 2013). The adequacy of the final sample size was continually assessed during the data collection process, when a point of ‘data saturation’ was established the study was closed.

Access to participants was facilitated through an existing working relationship with the National Institute of Health Research Nottingham Biomedical Research Centre (NIHR Nottingham BRC). The study recruited 14 participants in total. Purposive sampling was used, seeking to maximise the depth of the data collected (Miller and Crabtree, 1992). Only participants with a confirmed diagnosis of IBD, by endoscopy, histology or MRI, and described as fatigued using the Multidimensional Fatigue Index (MFI-20) (Gentile et al., 2003) questionnaire, were approached. The MFI-20 was used to confirm the presence of fatigue, rather than the IBD Fatigue Scale (Czuber-Dochan et al., 2014) as the MFI-20 has a clinically validated cut off point for diagnosing fatigue, where the IBD Fatigue Scale does not. The IBD Fatigue Scale was used to help guide the interview process by highlighting the areas of their daily life that participants may have felt the most functional restrictions around due to IBD fatigue (Czuber-Dochan et al., 2014). Those participants, who met the inclusion criteria and provided a written consent, were interviewed at a convenient time for them.

Eligibility criteria

Inclusion and exclusion criteria are detailed in Table 1. It was decided that the study sample, would consist solely of patients with Crohn’s Disease (CD). This decision was based on higher prevalence of fatigue in CD than in Ulcerative Colitis (UC) patients, making recruitment more feasible (Gajendran et al., 2018; Hashash et al., 2012; Hashash et al., 2018).

Table 1.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria.

| Inclusion criteria | Exclusion Criteria |

|---|---|

| Aged 16–75 years of age | HADS >8 |

| BMI <30 kg/m2 | Haematological or biochemical abnormalities (e.g. iron anaemia) |

| Diagnosed with CD | Renal failure |

| In remission, as displayed by | Hypokalaemia |

| HBI score <436 | Pregnancy or childbearing in the last 6 months |

| CRP <5 mg/L | Vitamin B complex deficiencies |

| Faecal calprotectin <50 μg/g37,38 | Active or previous prescriptions of corticosteroids in the last 12 weeks |

| Fatigued as defined by | Overt muscle wasting (defined as 2 standard deviations outside the age-related norm as measured by DEXA) |

| MFI-20 score >14 in any domain39 | Fatigue starting after the onset of Thiopurine therapy |

| Present arthritis or arthralgia | |

| Surgical intervention in the last 12 weeks |

Data collection

Early introduction of the study information ensured that the participant was aware of the purpose and level of their involvement. Verbal consent was obtained in order to book the time and place for the interviews. Valid informed consent was received by the lead author on the day of interview, prior to undertaking the interview.

When beginning the interview, it was important to establish background information to contextualise the rest of the interview (Blandford, 2013). This enables the researcher to access a deeper understanding of the data, and also guide the interview and interview questions in order to obtain richer data (Blandford, 2013).

During this phase, broad open-ended questions were used to help the participant establish confidence. This helps the participant ‘settle into’ the interview, reducing feelings of anxiety and increasing their willingness to share personal details and detailed responses (‘A Four-part Introduction to the Interview: Introducing the Interview; Society, Sociology and the Interview; Anthropology and the Interview; Anthropology and the Interview—Edited’, 2014). The themes of interest shaped the interview, derived from the IBD fatigue scale and the participant’s responses to questions, meaning that the direction and content of the interview was dictated by those topics that arose and those deemed interesting and relevant by the interviewer (Ritchie and Lewis, 2003). This enables thorough exploration of topics and allows the interviewee to provide detailed, in-depth responses to questions that are also sensitive to the nature and depth of the information willing to be disclosed by the participant (Booth and Booth, 1994). Continuity of theme is important as participants are likely to be thinking in a focused way about topics they don’t naturally consider in as much depth. During the core phase of interviewing a technique used to help with recall, the Critical Incident Technique (Flanagan, 1954), was used to extract details of specific incidents or examples. This involved asking people to focus on the details of specific incidents rather than generalisations and allowed the collection of much more detailed responses than might have been given with open ended questioning.

The end of the interview was clearly signalled to the participant by stating ‘we are coming to the end of the interview now’ during the conversation. This allowed participants to wrap up the conversation, making any final statements. After the close of the interview the participants were thanked for their time and contributions. Interviews were digitally recorded and later transcribed by the lead author. Careful consideration was given to the placement of the recorder and the environment that the interview was conducted in to reduce such issues as poor recording quality and background noise (Bailey, 2008).

Data analysis

Thematic analysis (TA) was considered a suitable method to gain an overall exploratory understanding of the pattern of experience in this population.

Traditionally TA has been seen as a process performed within major analytic traditions such as grounded theory (Boyatzis, 1998; Ryan and Bernard, 2000); however, more recent work, particularly in the field of psychology, have framed TA as a method in its own right (Braun and Clarke, 2006). In contrast to other exploratory methods such as interpretive phenomenology, which follows an in-depth, idiographic approach, TA allows greater flexibility to include participants from a somewhat heterogenous background (Braun and Clarke, 2014). This was considered important for the present research, seeking to gain an overall insight into the experience within the patient population living with Crohn's Disease rather than a particular sub-group. An inductive, semantic TA was designed, in accordance with the research question and the researcher’s epistemological position. An inductive approach means the themes identified will be strongly linked to the data, without trying to fit into pre-existing coding frames (Patton and Patton, 2002).

Data collection and analysis occurred in parallel, allowing the adequacy of the final sample size to be continually assessed during the data collection process, when a point of ‘data saturation’ was established this was discussed with the principal investigator of the study and recruitment to the interview study was closed.

Generally it is considered that saturation is the point at which additional data do not lead to any new emergent codes or themes (Birks and Mills, no date; Urquhart, 2013; Given, 2016). The concept of data saturation originates in grounded theory (Charmaz, 2000); it is now used across a range of approaches in qualitative research. Some researchers claim that a failure to reach saturation has a negative impact on the quality of the research (Recommended Apa Citation Fusch and Ness, 2015). Saturation is the most commonly billed measure of qualitative rigour offered by authors (Guest et al., 2006; Morse, 2015; Morse et al., 2002).

Results

Interviews took place between September 2018 and July 2019. Interview duration averaged 54 minutes, with a range of 37–62 minutes.

Sample characteristics

Fourteen participants were recruited, of which nine (64%) were females. All participants identified themselves as of a ‘White British’ ethic origin. Respondents were an average of 37.3 years of age, (SD ±13.5.). Participants reported they experienced symptoms of IBD fatigue for an average of 10.9 years (SD ±4.6). All participants were considered as experiencing fatigue using the MFI-20 questionnaire as part of the inclusion criteria (Beck et al., 2013). Using the IBD Fatigue Scale (Czuber-Dochan et al., 2014), 11 out of 14 participants reported that fatigue was constant and three reported intermittent fatigue. Further sample demographics are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Sample characteristics.

| Sample characteristics | SD | |

|---|---|---|

| Age in years, mean (SD) | 37.3 | 13.5 |

| Female gender (%) | 64 | |

| Disease status | ||

| Mean HBI score (SD) | 2 | 1.5 |

| Average disease duration (mean time since diagnosis of IBD in years) | 9.2 | 7.4 |

| Fatigue status | ||

| Mean length of time fatigue has been present in years (SD) | 10.9 | 4.6 |

| Reported constant fatigue symptoms (%) | 79% | |

| Reported intermittent fatigue symptoms (%) | 21% | |

| Mean MFI-20 score (SD) | 12.5 | 2.6 |

| Mean IBD Fatigue Scale score (SD) | ||

| Introduction | 9 | 5.4 |

| Methods | 47 | 15 |

| Medications | ||

| Immunosuppresants (%) | 36 | |

| Biologicals (anti-TNF) (%) | 21 | |

| Aminosalysate (Penstasa). (%) | 7 | |

| Antidepressants (%) | 14 | |

| Employment status | ||

| Full time Working/Student (%) | 86 | |

| Part time (%) | 14 | |

| Unemployment (%) | 0 | |

| Level of education | ||

| A level or equivalent (%) | 50 | |

| Degree level (%) | 21.5 | |

| Postgraduate level (%) | 21.5 | |

| Doctoral level (%) | 7 | |

| Surgical intervention | ||

| Ileostomy (%) | 7 | |

| Ileal resection (%) | 29 | |

| Hemicolectomy (%) | 7 | |

| Relationship status | ||

| Married (%) | 36 | |

| Relationship/Co-habiting (%) | 28 | |

| Single (%) | 36 | |

| Smoking | ||

| Never (%) | 79 | |

| Past (%) | 14 | |

| Current (%) | 7 | |

(%)=percentage of total sample (N=14); (SD)= standard deviation; HBI= Harvey Bradshaw Index Score; MFI-20= Multiple Fatigue Inventory- 20 questionnaire.

Themes

Data analysis resulted in identifying three main themes and eight sub-themes (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Main themes and sub-themes.

Theme 1 - The new normal

Participants described how living with IBD fatigue had become ‘normal’ for them. A sense of a ‘new normal’ was established by some. One participant reported that through undertaking the interview study it ‘made me realise how much [IBD fatigue] does affect me, and how normal it has become’ (IT06, Male, 27 years of age).

Acceptance

Participants described and defined IBD fatigue in their own words. They described differences between tiredness and fatigue; ‘fatigue is much worse, like a whole-body lack of energy, tiredness can pass but fatigue sticks around no matter what I do’ (IT08, M, 26). Definitions used language to describe the physical feelings of fatigue; ‘Like I am wearing a heavy coat all of the time’ (IT14, F, 25) and ‘I feel like my bones are heavy and I am tired all over’ (IT08, M, 26). Participants also described impact on mental feelings of fatigue; ‘fatigue is a blanket that covers every kind of thing I try and do’ (IT04, F, 34). Participants were keen to distinguish the differences between ‘physical’ and ‘mental’ fatigue: ‘I think I am just much better at managing my physical symptoms and maybe just get on with my mental fatigue’ (IT03, F, 30).

IBD fatigue was ‘accepted’ by some participants, and its impact on their ability to undertake daily tasks at home, ‘I have just come to accept it, it is a way of life now’ (IT13, F, 27), and at work ‘there’s no question, I definitely can’t do as much as I used to do’ (IT02, F, 45). Motivation to keep up with the same daily activities as before IBD fatigue and in comparison, to those without fatigue, was important to participants; ‘I just don’t let it get on top of me. It’s the motivation thing, so long as I keep going, embrace the fact that things will take a bit more effort for me to do the same things as other people do’ (IT03, F, 30).

Adaptation

The most predominant adaptation discussed was making plans; ‘if I plan and use my day wisely it means I have enough energy left at the end of the day for more fun things’ (IT11, M, 51). Making plans allowed participants to take control of their day-to-day life; ‘I can take control of my workday, manage my day better’ (IT11, M, 51).

Adaptation comes about from previous maladaptive techniques such as all or nothing behaviours; ‘I used to think about what I wanted or needed to do the most and then I would do that and hope that I had enough energy left to do the rest, if I didn’t, I would cancel plans or call in sick to work, I did my best to stop doing that as that’s unhealthy behaviour’ (IT13, F, 27). Some participants acknowledged that utilising adaptive behaviours requires greater effort ‘[fatigue] makes things harder to do, it takes more effort, both in the actually doing the thing, like going out or making dinner, but it takes times to plan it too. I have to put in a lot of effort planning’ (IT03, F, 30). Adaptation involved establishing new limits encompassing activity at home, work and leisure activities; ‘I plan to do enough with my day so that I am tired, but not exhausted, I know my limits’ (IT09, F, 44).

Social impact

IBD fatigue appears to have a meaningfully negative impact on social interactions. ‘It has the biggest impact on my social life’ (IT04, F, 34). One participant reported that they felt interacting socially actually alleviated feelings of fatigue ‘laughing and joking and seeing my friends helps me feel better’ (IT08, M, 26).

Participants state that intimate relationships are adversely impacted on by IBD fatigue, as fatigue can lead to extended periods of little or no intimate relations with partners ‘when I’m really worn out it can be weeks where we don’t do anything’ (IT06, M, 26). Weekly routines, designed to prioritise work, can de-prioritise intimacy ‘we don’t really spend any time together in the bedroom, except for weekends’ (IT05, F, 25).

Understanding of IBD fatigue by family, friends and colleagues was important to participants. Most participants reported having good social support; however, understanding of the disease was often lacking; ‘I think that they understand that I have an illness that can mean I can’t always do things with them, but I don’t think that they actually understand the disease’ (IT10, M, 49). Not all participants reported a lack of understanding. One participant reported their partner’s understanding and appreciation of the impact of IBD fatigue ‘has contributed to us being close’ (IT07, M, 52). Support of colleagues has been discussed in the adaptations sub-theme, but it was also reported as a way of alleviating fears of social stigma in the workplace, ‘I felt I was able to say “I don’t feel like I can do that”, and I didn’t get judged or laughed at’ (IT09, F, 44).

Participants discussed worries related to how they would be perceived by others, ‘I worry about looking like I am always ill, like the flaky friend who is constantly cancelling plans’ (IT08, M, 26). Participants often based this feeling on comparison to others, ‘I feel like I get much more tired, more quickly, than those around me, and it can be annoying and sometimes embarrassing’ (IT05, F, 25). This was frequently related to the workplace ‘I don’t want people to think any less of me, like I can’t do my job, like it is something that stops me from being able to do things like other people can’ (IT11, M, 51). This could lead to lessened feelings of self-worth, lowered self-esteem and reduced motivation to maintain social relationships and interactions, even though participants acknowledged that these are important to them.

Theme 2 - Energy as a resource

Participants referred to energy as a commodity, describing how energy levels could be managed through prioritisation and planning of tasks. This belief might be a way of contextualising and understanding fatigue, and may also be way of better communicating fatigue to others. A prominent feature of most interviews was that participants believed that they were constantly at a ‘deficit’ in terms of levels of energy; ‘I feel like I start off with a negative balance anyway, like I wake up in the morning and I already don’t have enough energy to make it through the day before I have even done anything’ (IT05, F, 25).

Energy use

Energy use was discussed through the allocation of observed amounts of energy to prioritised and planned tasks; ‘every task I do has to be weighed up in terms of how much time and energy it will take to complete it’ (IT11, M, 51). Often employment or studying was prioritised over other activities; ‘I give all I have got at work, which leaves me really tired and with no energy left for outside of work things’ (IT06, M, 27). Only one participant reported ‘I try and strike a balance between my work life and home life’ (IT11, M, 51).

All or nothing behaviours were prevalent throughout the interviews; ‘By the time I get home, I don’t have any energy left to do anything around the house’ (IT05, F, 25). This type of behaviour was often weighed against the need for energy for ongoing daily tasks, or activity over subsequent days; ‘I start out at a deficit, if I then go and blow all of the energy I have on doing all of the washing and hoovering and cleaning in one go, then I won’t be much good for the rest of the day, or even the day after’ (IT13, F, 27). The abundance of all or nothing behaviours suggests that there is a lack of awareness of fatigue management techniques, such as poor task prioritisation or lack of motivation.

Energy conservation

‘Making plans’ was integral to establishing a sense of ‘normality’; ‘I plan what I need to do each day and make sure I have enough energy to be able to do all the things I want to do’ (IT08, M, 26). A primary management technique employed was to introduce more rest into daily routines; ‘I just have to make sure that I have to rest, sleep, to make sure I have time to catch up on my sleep and have the energy to go to work the next and the next day’ (IT12, F, 51). However, most participants agreed that even after rest they were unable to feel well rested; ‘incapable of catching up on the energy I am using up’ (IT03, F, 30). Energy conservation techniques included tendency to ‘sacrifice’ the undertaking of an activity; ‘I do just write things off as too much effort’ (IT06, M, 27).

Theme 3 - Keeping healthy

General health

Participants reported that having a good general health was beneficial for them as it helped them to overcome the feelings of fatigue; ‘I think maybe I have a good level of general health, so I have a better ability to be able to compensate for fatigue’ (IT09, F, 44). Most participants reported that they were able to maintain a good level of personal care even when experiencing high levels of IBD fatigue. However, two participants reported that high levels of IBD fatigue would impact on their choices regarding personal care; ‘I’ll skip having a shower and go straight to bed and shower the next day if it’s really bad’ (IT10, M, 49). As only two participants reported this, it could be suggested that for most people, IBD fatigue does not have an impact on personal or self-care though this issue might be underreported due to embarrassment.

Nutrition

Participants reported that at times, food preparation was impaired by their high levels of fatigue; ‘I don’t want to use the last of my energy on cooking us something to then not be able to eat it and enjoy it. If it takes longer than 30 minutes to cook, then I’m not going to make it’ (IT03, F, 30). Conversely, the majority of participants reported that they ensured they maintained a healthy diet as they believed this would help them reduce levels of IBD fatigue and improve the ability to cope with it.

Physical activity

Physical activity was considered important in being better able to better overcome feelings of IBD fatigue; ‘I think by keeping up regular exercise it keeps me healthy, making it easier to get through that heavy fatigue feeling’ (IT13, F, 27).

Participants reported that physical activity reduced levels of IBD fatigue; ‘I can sometimes feel like I have a little more energy, like I have managed to access some reserves in my body, sometimes that helps’ (IT05, F, 25). One participant reported that undertaking physical activity gave them a sense of achievement; ‘When I go to the gym I do feel better in myself, like I have achieved something’ (IT04, F, 34). This sense of achievement could encourage feelings of accomplishment and boost motivation. Participants reported that keeping up a level of physical activity/exercise was something that they included in their daily planning; ‘I like to go to the gym. I try and go at least three times a week….For me it is just as important to stay active as it is to get lots of rest. It is a momentum thing’ (IT03, F, 30).

Discussion

Impact of IBD fatigue on HRQoL extends beyond the impact upon the individual as a feeling or experience, but instead, impacts the structure of their daily lives and every decision made (Kalafateli et al., 2013). Since many of those diagnosed with IBD are young, the impact of fatigue on an individual’s education, personal and professional life may be greater in IBD than in other LTCs (Floyd et al., 2015; Lesage et al., 2011).

Throughout the interview study participants reported strategies used to better manage daily life with fatigue. These strategies often incorporated planning and prioritisation of tasks in order to coordinate utilisation of energy and control energy levels. Through task prioritisation favouring work and education, participants reported that they would often miss out on social interactions and reduce or remove leisure activities from their daily life.

The individuals’ ability to deal with stress and cope with IBD fatigue has been shown to have an impact on HRQoL. ‘Normalising behaviours’ were described during the interview study in terms of the participants incorporating fatigue management techniques into their daily lives in order to reduce the negative impact that fatigue has on daily functioning. Those with high levels of acceptance, ‘good’ ways of coping and adapting to life with IBD, have better HRQoL (Bol et al., 2010; Graff et al., 2011a, 2011b; Tanaka and Kazuma, 2005). A variety of different words were used to describe fatigue such as ‘tiredness’, being ‘worn out’ and ‘run out of energy’. The acceptance of illness is a significant factor affecting the level of HRQoL in patients with LTCs, such as cancer (Chabowski et al., 2017), rheumatoid arthritis (RA) (Kostova et al., 2014) and heart disease (Obiego et al., 2017).

Self-motivated acceptance processes relate to people’s perceptions of independence and dependence, as well as feelings of helplessness, and efficacy in coping with chronic symptoms (Gignac et al., 2000; Megari, 2013; Pollock, 1987). If individuals self-manage their chronic illness successfully, it is likely that their HRQoL will be enhanced (Weinert et al. 2008). It is well reported that individuals with IBD have higher HRQoL when they feel they have some control over their symptoms (Sainsbury and Heatley, 2005; Skrautvol and Naden, 2017; Woodward et al., 2016). Self-management techniques instil a sense of responsibility upon the individual to take ownership over their own health and promote a positive perception of self (Harper and The Whoqol Group, 1998; Bishop, 2005; Living well with chronic illness: A call for public health action, 2011). Individuals who display acceptance by improving their coping behaviours through therapy, such as cognitive behavioural therapy, have been shown to have better HRQoL (Artom et al., 2017; Fukuda et al., 1994; Luo et al., 2018; Power et al., 2008; Repping-Wuts et al., 2008).

Feelings of fulfilment are determined by levels of satisfaction in specific areas of an individual’s life (Pavot and Diener, 1993). How individuals with LTCs perceive societal demands can lead to feelings of stigmatisation. Stigma can negatively impact an individuals’ personal identity, social life and economic opportunities, in turn contributing to sense of unfulfillment (Ablon, 2002; Joachim and Acorn, 2000). Through task prioritisation, favouring work and education, participants reported that they would often miss out on social interactions. This has a negative impact on HRQoL. Patients with IBD have been shown to feel like IBD fatigue stops them from achieving what they perceive as their full potential (Rooy et al., 2004). Some of the study participants discussed their feeling relating to feelings of isolation and reliance on family members leading to feeling like a burden. Patients worry that their fatigue restricts not only their own but also their family’s social activities (Woodward et al., 2016).

Acceptance of IBD and using effective coping strategies improve levels of HRQoL. Study participants discussed their sense of acceptance in terms of how they manage their daily life. Negative attitude and ineffective strategies, such as all or nothing behaviours, worsens HRQoL (Radford et al., 2020; Sainsbury and Heatley, 2005; Sammut et al., 2015; Tanaka and Kazuma, 2005; Todorovic, 2012). Successful lifestyle modification has a positive effect on patients' HRQoL in LTCs (Allison et al., 1997; Van der Have et al., 2015). Individuals with LTCs often have to adjust their aspirations, lifestyle and employment arrangements due to chronic symptoms such as fatigue (Obieglo et al., 2014; Van Houtum, Rijken and Groenewegen, 2015). Previous studies have shown that people with LTCs experience tension between managing their symptoms whilst being able to do what they would like to with their lives (Nio Ong et al., 2011; Townsend et al., 2006). ‘Normalising behaviours’ were described during the interview study in terms of the participants incorporating fatigue management techniques into their daily lives. Participants using poor methods of fatigue management, such as task avoidance and all or nothing behaviours, experience higher levels of fatigue and worse HRQoL than those who do not (Artom et al., 2017; Habibi et al., 2017).

| Study Title (Main study) | Non-invasive approaches to identify the cause of fatigue in inflammatory bowel disease patients |

|---|---|

| REC reference | 17/EM/043 |

| Protocol number | 17083 |

| IRAS project ID | 233722 |

Group education for fatigue management in MS has been shown to offer improvements in fatigue and HRQoL when compared to no intervention. Participant education included elements from cognitive behavioural therapy, focus on energy effectiveness, self-management and self-efficacy theories (Blikman et al., 2013; Thomas et al., 2014).

Multiple studies in IBD report that disengagement from social activity due to high levels of fatigue negatively impacts HRQoL (Faust et al., 2012; Sammut et al., 2015; Tanaka and Kazuma, 2005; Woodward et al., 2016). The interview study revealed that the most common adaptation in the day-to-day lives of participants was a reduction of social interaction. Patients worry that their fatigue restricts not only their own but also their family’s social activities (Woodward et al., 2016). However, close relationships with friends, social support groups, networks and counselling are evidenced to positively impact on ability to better manage IBD fatigue, improving HRQoL (Faust et al., 2012; Sainsbury and Heatley, 2005). Echoing the reports from study participants, perceived lack of social support has been shown to be related to increased levels of IBD fatigue (Tanaka and Kazuma, 2005). Social support, the sharing of concerns and experiences with family, friends and HCPs helps to maintain high levels of HRQoL (Haapamäki et al., 2018; Lesage et al., 2011).

Throughout the interview study the participants reported they made extra efforts to maintain a level of ‘good general health’, such as sustaining good nutritional intake and keeping physically active, this was done in order to better overcome feelings of fatigue. This was a particular element of ‘self-management’ reported by participants.

In some LTCs, such as MS, there is patient focused information available relating to the importance of making time to prepare and eat a healthy diet when managing a LTC, even when fatigued; however, there is scarce information in IBD (Diet and Nutrition for Energy with COPD, Cleveland Clinic, no date; Healthy eating/MS Trust, no date; Forbes et al., 2017). Managing dietary intake offers the individual a sense of control when living with a LTC which often presents unpredictable symptoms (Czuber-Dochan et al., 2020). In IBD concerns related to diet only add to the level of discomfort and stress, for many this affects their ability to socialise. Food preparation is a task reportedly most put off by study participants due to levels of IBD fatigue. People with IBD strive for control, but this doesn’t mean that many achieve that sense of control over their symptoms, failing to maintain a healthy diet or having the ability to even prepare their own meals may compound the sense of a lack of control.

Graded exercise has been suggested as way of managing fatigue in LTCs including IBD, RA and MS (Hulme et al., 2018). There is no evidence of negative side effects of moderate physical activity in people with stable IBD in remission (Engels et al., 2018; Narula and Fedorak, 2008). Study participants reported that they found physical activity to reduce their levels of fatigue. Exercise has been shown to reduce fatigue and improve HRQoL in MS (Andreasen et al., 2011; Khan et al., 2014) RA (Cramp et al., 2013) and chronic fatigue syndrome (Castell et al., 2011; Larun et al., 2017). Although not yet described in IBD, this has been discussed in various other LTCs with a focus on the health benefits of physical activity (Warburton et al., 2006). Most exercise interventions described utilise aerobic exercise, some use a combination of both aerobic and resistance exercise (Andreasen et al., 2011; Castell et al., 2011; Cramp et al., 2013; Khan et al., 2014; Larun et al., 2017; Hulme et al., 2018). There is little data regarding the impact of exercise on HRQoL in IBD, that which does exist is either of poor quality or is contradictory.

Conclusions

This is the first study to explicitly examine the experience of IBD related fatigue and its impact on HRQoL. Insights have been gathered into participants’ experiences of IBD fatigue and its effect on daily life.

The factors of HRQoL most impacted on by IBD fatigue were alterations made to daily life, through incorporation of management techniques into daily routine and the negative impact on social activities and relationships.

The recommendation for future research is to explore the role that patient self-management of symptoms has in improving levels of IBD fatigue and HRQoL in this cohort.

Limitations

Although adequate for an effective TA, the sample size of 14 was smaller than the planned 20. However, data saturation was met and has been shown to be achievable in TA with a sample size of 12 (Guest et al., 2006). Participants were self-selected, with many coming from the same established research patient group. It is possible that self-selected participants were inherently more open to talking about their experiences and are less representative of the wider IBD population. Further to this, it is also possible that those patients who are most symptomatic are the ones most willing to discuss symptoms and impact, also making this sample less representative of the wider IBD population. The data were coded, and themes identified by one person, the lead author, and the analysis then discussed with academic supervisors. This process allowed for consistency in the method but failed to provide multiple perspectives from a variety of people with differing expertise. For future research using this method, the coding of data should involve several individuals (Nowell et al., 2017).

The lead author was aware of her previous professional experience of working with patients with IBD, recognising the importance of acknowledging, through reflexivity, the way these previous experiences may impact upon the approach and interpretation of information gathered during the course of the study. Although presented as a linear procedure, the research analysis was an iterative and reflexive process. The data collection and analysis stages in this study were undertaken concurrently, actively revisiting the previous stages of the process before undertaking further analysis to ensure that the developing themes were grounded in the original data. In the process of reflexivity, the researcher was constantly adjusting behaviour, such as the type of questioning utilised, to benefit the research process (O’Connor, 2011). Recording thoughts after interviews and reflecting on these at the time of data analysis as a way of controlling for bias and consequently to improve the study rigour (Creswell et al., 2007; Finlay, 2006). The position of the lead author throughout the research process presented an interesting point surrounding possible role conflict; novice researcher versus experienced Registered Nurse (RN). For this reason, the lead author was explicit in detailing that participation was voluntary, had no implication on routine clinical care, participants were not under the clinical care of the researcher at the time of their participation and that withdrawal at any time was possible.

Key points for policy, practice and/or research

• IBD fatigue is mutli-factorial and affects people living with IBD in multiple ways, impacting on daily life and significantly reducing health related quality of life (HRQoL).

• The factors of HRQoL most impacted on by IBD fatigue were alterations made to daily life through incorporation of management techniques into daily routine and the negative impact on social activities and relationships.

• Patients living with IBD describe and experience IBD fatigue in different ways, which can make its detection and management in the clinical setting difficult.

• More research is required in order to better help support people living with IBD fatigue and understand the impact that patient self management may have on the level of IBD fatigue experienced.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the NIHR Nottingham BRC for hosting this interview study and the University of Nottingham for providing the data analysis software.

Biography

Shellie J Radford grew up in Awsworth and Kimberley near Nottingham and graduated from the University with a BSc in Nursing in 2013. After completing a research MSc last year, she has now embarked on a PhD in the School of Medicine, looking into the use of ultrasound in Crohn's Disease alongside her work as a clinical academic IBD nurse specialist at Nottingham University Hospitals NHS Trust.

Gordon W Moran is an academic gastroenterologist with a special interest in the clinical management of Inflammatory Bowel Disease. He has completed his gastroenterology training in Birmingham, UK and his PhD studies with Professor John Mclaughlin at the University of Manchester in 2011. He advanced his clinical training in Inflammatory Bowel disease by undertaking a one year advanced clinical fellowship in Inflammatory Bowel disease at the University of Calgary, Canada under the supervision of Professor Remo Panaccione. He has been appointed as an Associate Professor in Gastroenterology at the University of Nottingham in 2013. Since then, his primary research aim is investigating the altered whole body physiology (eating behaviour, gut motility and altered muscle physiology) in Crohn's patients as well as optimising new MRI techniques for measuring disease active and disease burden in IBD.

Wladyslawa Czuber-Dochan is a Senior Lecturer in Adult Nursing and Associate Dean, Director of Postgraduate Research Studies at the Florence Nightingale Faculty of Nursing, Midwifery & Palliative Care, King's College London. Her research has contributed to the current understanding of fatigue in IBD. She has published extensively on a range of topics related to IBD, such as fatigue, pain, distress, stoma formation, and food-related quality of life. She is a member of the Scientific Boards for Crohn's & Colitis UK and N-ECCO. Wladzia's main research interests are in patients' reported outcomes in IBD symptom management. She integrates education and research and is passionate about developing evidence based practice through translational research.

Footnotes

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by a research project grant from Crohn’s and Colitis UK charity.

Ethical approval: The study was conducted in accordance with ethical principles that have their origin in the declaration of Helsinki, the principles of good clinical practice (GCP) and the framework for Health and Social Care (NHS Health Research Authority, 2020; World Medical Association, 1996). Favourable ethical opinion was given by the East Midlands research ethics committee (REC No: 17/EM/043).

ORCID iD

Shellie J Radford https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2226-0810

References

- A Four-part Introduction to the Interview: Introducing the Interview; Society, Sociology and the Interview; Anthropology and the Interview; Anthropology and the Interview—Edited (2014) The Interview: An Ethnographic Approach. Oxford, UK: Berg Publications, pp. 1–49. DOI: 10.5040/9781474214230.0006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ablon J. (2002) The nature of stigma and medical conditions. Epilepsy & Behavior 3(6): 2–9. DOI: 10.1016/s1525-5050(02)00543-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agee J. (2009) Developing qualitative research questions: a reflective process. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education 22(4): 431–447. DOI: 10.1080/09518390902736512. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Allison PJ, Locker D, Feine JS. (1997) Quality of life: a dynamic construct. Social Science & Medicine 45(2): 221–230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andreasen A, Stenager E, Dalgas U. (2011) The effect of exercise therapy on fatigue in multiple sclerosis. Multiple Sclerosis Journal 17(9): 1041–1054. DOI: 10.1177/1352458511401120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnett SV, Clark IA. (2012) Inflammatory fatigue and sickness behaviour - lessons for the diagnosis and management of chronic fatigue syndrome. Journal of Affective Disorders 141: 130–142. DOI: 10.1016/j.jad.2012.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Artom M, Czuber-Dochan W, Sturt J, et al. (2017) Cognitive behavioural therapy for the management of inflammatory bowel disease-fatigue with a nested qualitative element: Study protocol for a randomised controlled trial. Trials 18(1). DOI: 10.1186/s13063-017-1926-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Artom M, Czuber-Dochan W, Sturt J, et al. (2017) The contribution of clinical and psychosocial factors to fatigue in 182 patients with inflammatory bowel disease: a cross-sectional study. Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics 45: 403–416. DOI: 10.1111/apt.13870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey J. (2008) First steps in qualitative data analysis: transcribing. Family Practice 25(2): 127–131. DOI: 10.1093/fampra/cmn003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck A, Bager P, Jensen PE, et al. (2013) How fatigue is experienced and handled by female outpatients with inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology Research and Practice 2013: 1–8. DOI: 10.1155/2013/153818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhaskar R. (2013) A realist theory of science. A Realist Theory of Science. DOI: 10.4324/9780203090732. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Birks M, Mills J. (n.d) Grounded Theory. Available at: https://researchonline.jcu.edu.au/37746/1/37746_Birks_and_Mills-2015_Front_Pages.pdf (Accessed: 23 September 2018). [Google Scholar]

- Bishop M. (2005) Quality of life and psychosocial adaptation to chronic illness and disability. Rehabilitation Counseling Bulletin 48(4): 219–231. DOI: 10.1177/00343552050480040301. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Blandford A. (2013) Semi-Structured Qualitative Studies. In: Soegaard M, Dam R. (eds) The Encyclopedia of Human-Computer Interaction. Denmark: Interaction Design Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Blikman LJ, Huisstede BM, Kooijmans H, et al. (2013) Effectiveness of energy conservation treatment in reducing fatigue in multiple sclerosis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation 94: 1360–1376. DOI: 10.1016/j.apmr.2013.01.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bol Y, Duits AA, Vertommen-Mertens CER, et al. (2010) The contribution of disease severity, depression and negative affectivity to fatigue in multiple sclerosis: a comparison with ulcerative colitis. Journal of Psychosomatic Research 69(1): 43–49. DOI: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2009.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Booth T, Booth W. (1994) The use of depth interviewing with vulnerable subjects: Lessons from a research study of parents with learning difficulties. Social Science & Medicine 39(3): 415–424. DOI: 10.1016/0277-9536(94)90139-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyatzis RRE. (1998) Thematic Analysis and Code Development: Transforming Qualitative Information. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications. DOI: 10.1177/102831539700100211. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Braun V, Clarke V. (2006) Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology 3(2): 77–101. DOI: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Braun V, Clarke V. (2014) What can “thematic analysis” offer health and wellbeing researchers? International Journal of Qualitative Studies on Health and Well-Being 9(1): 26152. DOI: 10.3402/qhw.v9.26152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castell BD, Kazantzis N, Moss-Morris RE. (2011) Cognitive behavioral therapy and graded exercise for chronic fatigue syndrome: a meta‐analysis. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice 18: 311–324. DOI: 10.1111/j.1468-2850.2011.01262.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chabowski M, Polański J, Jankowska-Polanska B, et al. (2017) The acceptance of illness, the intensity of pain and the quality of life in patients with lung cancer. Journal of Thoracic Disease 9(9): 2952–2958. DOI: 10.21037/jtd.2017.08.70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charmaz K. (2000) Grounded theory: objectivist and constructivist methods. In: The Handbook of Qualitative Research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. DOI: 10.1007/s13398-014-0173-7.2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen RD. (2002) The quality of life in patients with Crohn’s disease. Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics 16(9): 1603–1609. DOI: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2002.01323.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cramp F, Hewlett S, Almeida C, et al. (2013) Non-pharmacological interventions for fatigue in rheumatoid arthritis. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD008322.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creswell JW, Hanson WE, Clark Plano VL, et al. (2007) Qualitative research designs. The Counseling Psychologist 35(2): 236–264. DOI: 10.1177/0011000006287390. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Czuber-Dochan W, Norton C, Bassett P, et al. (2014) Development and psychometric testing of inflammatory bowel disease fatigue (IBD-F) patient self-assessment scale. Journal of Crohn’s and Colitis 8(11): 1398–1406. DOI: 10.1016/j.crohns.2014.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czuber‐Dochan W, Morgan M, Hughes LD, et al. (2020) Perceptions and psychosocial impact of food, nutrition, eating and drinking in people with inflammatory bowel disease: a qualitative investigation of food‐related quality of life. Journal of Human Nutrition and Dietetics 33(1): 115–127. DOI: 10.1111/jhn.12668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czuber-Dochan W, Ream E, Norton C. (2013) Review article: description and management of fatigue in inflammatory bowel disease. Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics 37: 505–516. DOI: 10.1111/apt.12205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dibley L, Bager P, Czuber-Dochan W, et al. (2017) Identification of research priorities for inflammatory bowel disease nursing in Europe: a Nurses-European Crohn’s and Colitis organisation delphi survey. Journal of Crohn's and Colitis 11(3): jjw164–359. DOI: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjw164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiCicco-Bloom B, Crabtree BF. (2006) The qualitative research interview. Medical Education 40: 314–321. DOI: 10.1111/j.1365-2929.2006.02418.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diener E, Seligman MEP. (2018) Beyond money: progress on an economy of well-being. Perspectives on Psychological Science 13: 171–175. DOI: 10.1177/1745691616689467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diet and Nutrition for Energy with COPD, Cleveland Clinic (n.d). Available at: https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/articles/9451-nutritional-guidelines-for-people-with-copd (Accessed: 27 December 2019).

- Dittner AJ, Wessely SC, Brown RG. (2004) The assessment of fatigue: a practical guide for clinicians and researchers. Journal of Psychosomatic Research 56(0022–3999): 157–170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engels M, Cross R, Long M. (2018) Exercise in patients with inflammatory bowel diseases: current perspectives. Clinical and Experimental Gastroenterology 11: 1–11. DOI: 10.2147/CEG.S120816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faust AH, Halpern LF, Danoff-Burg S, et al. (2012) Psychosocial factors contributing to inflammatory bowel disease activity and health-related quality of life. Gastroenterology & Hepatology 8(3): 173–181. Available at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22675279 (Accessed: 6 February 2019). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrans CE. (2005) Definitions and conceptual models of quality of life. In: Lipscomb J, Gotay CC, Snyder C. (eds) Outcomes Assessment in Cancer: Measures, Methods, and Applications. Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Finlay L. (2006) ‘Rigour’, ‘Ethical Integrity’ or ‘Artistry’? Reflexively reviewing criteria for evaluating qualitative research. British Journal of Occupational Therapy 69(7): 319–326. DOI: 10.1177/030802260606900704. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Flanagan JC. (1954) The critical incident technique. Psychological Bulletin 51: 327–358. DOI: 10.1037/h0061470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flick U. (2009) An Introduction to Qualitative Research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. DOI: 10.1017/CBO9781107415324.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Floyd DN, Langham S, Séverac HC, et al. (2015) The economic and quality-of-life burden of Crohn’s disease in Europe and the United States, 2000 to 2013: a systematic review. Digestive Diseases and Sciences 60(2): 299–312. DOI: 10.1007/s10620-014-3368-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forbes A, Escher J, Hébuterne X, et al. (2017) ESPEN guideline: clinical nutrition in inflammatory bowel disease. Clinical Nutrition 36(2): 321–347. DOI: 10.1016/j.clnu.2016.12.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukuda K, Straus SE, Hickie I, et al. (1994) The chronic fatigue syndrome: a comprehensive approach to its definition and study. Annals of Internal Medicine 121: 953. DOI: 10.7326/0003-4819-121-12-199412150-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gajendran M, Loganathan P, Catinella AP, et al. (2018) A comprehensive review and update on Crohn’s disease. Disease-a-Month 64(2): 20–57. DOI: 10.1016/j.disamonth.2017.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gentile S, DELAROZIèRE JC, Favre F, et al. (2003) Validation of the French 'multidimensional fatigue inventory' (MFI 20). European Journal of Cancer Care 12(1): 58–64. DOI: 10.1046/j.1365-2354.2003.00295.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gignac MAM, Cott C, Badley EM. (2000) Adaptation to chronic illness and disability and its relationship to perceptions of independence and dependence. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences 55(6): P362–P372. Available at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11078106 (Accessed: 19 February 2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Given L M. (2016) 100 Questions (and answers) about Qualitative Research. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications Ltd. Available at: https://researchoutput.csu.edu.au/en/publications/100-questions-and-answers-about-qualitative-research (Accessed: 23 September 2018). [Google Scholar]

- Graff LA, Vincent N, Walker JR, et al. (2011. a) A population-based study of fatigue and sleep difficulties in inflammatory bowel disease. Inflammatory Bowel Diseases 17(9): 1882–1889. DOI: 10.1002/ibd.21580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graff LA, Walker JR, Russell AS, et al. (2011. b) Fatigue and quality of sleep in patients with immune-mediated inflammatory disease. The Journal of Rheumatology Supplement 88: 36–42. DOI: 10.3899/jrheum.110902 10.3899/jrheum.110902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guest G, Bunce A, Johnson L. (2006) How Many Interviews Are Enough? Field Methods 18(1): 59–82. DOI: 10.1177/1525822X05279903. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Haapamäki J, Heikkinen E, Sipponen T, et al. (2018) The impact of an adaptation course on health-related quality of life and functional capacity of patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Scandinavian Journal of Gastroenterology 53(9): 1074–1078. DOI: 10.1080/00365521.2018.1500639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahdavi S, Habibi F, Habibi M, et al. (2017) Quality of life in inflammatory bowel disease patients: a cross-sectional study. Journal of Research in Medical Sciences 22(1): 104. DOI: 10.4103/jrms.JRMS_975_16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haney E, Smith MEB, McDonagh M, et al. (2015) Diagnostic methods for myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome: a systematic review for a national institutes of health pathways to prevention workshop. Annals of Internal Medicine 162(12): 834–840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harper A, The Whoqol Group (1998) Development of the World Health Organization WHOQOL-BREF quality of life assessment. Psychological Medicine 28(3): 551–558. DOI: 10.1017/S0033291798006667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hart AL, Lomer M, Verjee A, et al. (2017) What are the top 10 research questions in the treatment of inflammatory bowel disease? A priority setting partnership with the James Lind alliance. Journal of Crohn’s and Colitis 11: 204–211. DOI: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjw144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashash J, Benhayon D, Szigethy Rivers E, et al. (2012) Fatigue in IBD is related to poor quality of life and sleep, not inflammation. Inflammatory Bowel Diseases 18(Suppl 1): S33. doi: DOI: 10.1002/ibd.23058 10.1002/ibd.23058. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hashash JG, Ramos-Rivers C, Youk A, et al. (2018) Quality of sleep and coexistent psychopathology have significant impact on fatigue burden in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Journal of Clinical Gastroenterology 52(5): 423–430. DOI: 10.1097/MCG.0000000000000729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Healthy Eating/MS Trust (n.d). Available at: https://www.mstrust.org.uk/life-ms/diet/healthy-eating#why-is-diet-important-in-ms (Accessed: 27 December 2019).

- Hulme K, Safari R, Thomas S, et al. (2018) Fatigue interventions in long term, physical health conditions: a scoping review of systematic reviews. Plos One 13(10): e0203367. Public Library of Science. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0203367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huppertz-Hauss G, Høivik ML, Langholz E, et al. (2015) Health-related quality of life in inflammatory bowel disease in a European-wide population-based cohort 10 years after diagnosis. Inflammatory Bowel Diseases 21(2): 337–344. DOI: 10.1097/MIB.0000000000000272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joachim G, Acorn S. (2000) Stigma of visible and invisible chronic conditions. Journal of Advanced Nursing 32(1): 243–248. DOI: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2000.01466.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalafateli M, Triantos C, Theocharis G, et al. (2013) Health-related quality of life in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: a single-center experience. Annals of Gastroenterology 26(3): 243–248. Available at: www.annalsgastro.gr (Accessed: 12 September 2019). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan F, Amatya B, Galea M. (2014) Management of fatigue in persons with multiple sclerosis. Frontiers in Neurology 5. DOI: 10.3389/fneur.2014.00177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kostova Z, Caiata-Zufferey M, Schulz PJ. (2014) The process of acceptance among rheumatoid arthritis patients in Switzerland: a qualitative study. Pain Research and Management 19(2): 61–68. DOI: 10.1155/2014/168472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larun L, Brurberg KG, Odgaard-Jensen J, et al. (2017) Exercise therapy for chronic fatigue syndrome. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 4(4): CD003200. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD003200.pub7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee GV, Barnett BG. (1994) Using reflective questioning to promote collaborative dialogue. Journal of Staff Development. [Google Scholar]

- Lesage A-C, Hagège H, Tucat G, et al. (2011) Results of a national survey on quality of life in inflammatory bowel diseases. Clinics and Research in Hepatology and Gastroenterology 35(2): 117–124. DOI: 10.1016/j.gcb.2009.08.015 10.1016/j.gcb.2009.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Living well with chronic illness: A call for public health action (2011) Living Well with Chronic Illness: A Call for Public Health Action. Washington, DC: National Academies Press. DOI: 10.17226/13272. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Luo H, Sun Y, Li Y, et al. (2018) Perceived stress and inappropriate coping behaviors associated with poorer quality of life and prognosis in patients with ulcerative colitis. Journal of Psychosomatic Research 113: 66–71. DOI: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2018.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Megari K. (2013) Quality of life in chronic disease patients. Health Psychology Research 1(3): 27. DOI: 10.4081/hpr.2013.e27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller WL, Crabtree B F. (1992) Depth interviewing: the long interview approach. In: Stewart MA, Tudiver F, Bass MJ, et al. (eds) Tools for primary care research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, pp. 194–208. Available at: http://psycnet.apa.org/record/1992-97744-013 (Accessed: 23 September 2018). [Google Scholar]

- Morse JM, Barrett M, Mayan M, et al. (2002) Verification strategies for establishing reliability and validity in qualitative research. International Journal of Qualitative Methods 1(2): 13–22. DOI: 10.1177/160940690200100202. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Morse JM. (2015) “Data Were Saturated …”. Qualitative Health Research 25(5): 587–588. DOI: 10.1177/1049732315576699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mowat C, Cole A, Windsor A, et al. (2011) Guidelines for the management of inflammatory bowel disease in adults. Gut 60: 571–607. DOI: 10.1136/gut.2010.224154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narula N, Fedorak RN. (2008) Exercise and inflammatory bowel disease. Canadian Journal of Gastroenterology, 22, pp. 497–504. DOI: 10.1155/2008/785953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NHS Health Research Authority (2020) UK Policy Framework for Health and Social Care Research - Health Research Authority. London, UK: NHS Health Research Authority. Available at: https://www.hra.nhs.uk/planning-and-improving-research/policies-standards-legislation/uk-policy-framework-health-social-care-research/ (Accessed: 24 October 2018). [Google Scholar]

- Nightingale D J, Cromby J. (1999) Social Constructionist Psychology: A Critical Analysis of Theory and Practice. Maidenhead, UK: Open University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Nio Ong B, Jinks C, Morden A. (2011) The hard work of self-management: living with chronic knee pain. International Journal of Qualitative Studies on Health and Well-Being 6(3): 7035. DOI: 10.3402/qhw.v6i3.7035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nowell LS, Norris JM, White DE, et al. (2017) Thematic analysis. International Journal of Qualitative Methods 16: 160940691773384. DOI: 10.1177/1609406917733847. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- O'Connor SJ. (2011) Context is everything: the role of auto-ethnography, reflexivity and self-critique in establishing the credibility of qualitative research findings. European Journal of Cancer Care 20(4): 421–423. DOI: 10.1111/j.1365-2354.2011.01261.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obiegło M, Uchmanowicz I, Wleklik M, et al. (2016) The effect of acceptance of illness on the quality of life in patients with chronic heart failure. European Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing 15(4): 241–247. DOI: 10.1177/1474515114564929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obiegło M, Siennicka A, Jankowska EA, et al. (2017) Direction of the relationship between acceptance of illness and health-related quality of life in chronic heart failure patients. Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing 32(4): 348–356. DOI: 10.1097/JCN.0000000000000365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patton MQ, Patton MQ. (2002) Qualitative Research and Evaluation Methods. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Pavot W, Diener E. (1993) Review of the satisfaction with life scale. Psychological Assessment 5(2): 164–172. DOI: 10.1037/1040-3590.5.2.164. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Peyrin-Biroulet L. (2010) What is the patient’s perspective: how important are patient-reported outcomes, quality of life and disability? Digestive Diseases 28(3): 463–471. DOI: 10.1159/000320403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollock S E. (1987) Adaptation to Chronic Illness. Analysis of Nursing Research. Washington, DC: Nursing Clinics of North America, pp. 631–644. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Power JD, Badley EM, French MR, et al. (2008) Fatigue in osteoarthritis: a qualitative study. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders 9. DOI: 10.1186/1471-2474-9-63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radford SJ, McGing J, Czuber-Dochan W, et al. (2020) Systematic review: the impact of inflammatory bowel disease-related fatigue on health-related quality of life. Frontline Gastroenterology 12(1): 11–21. (in press). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Recommended Apa Citation Fusch and Ness (2015) Are We There Yet? Data Saturation in Qualitative Research, the Qualitative Report. Available at: http://www.nova.edu/ssss/QR/QR20/9/fusch1.pdf (Accessed 23 September 2018). [Google Scholar]

- Repping-Wuts H, Uitterhoeve R, van Riel P, et al. (2008) Fatigue as experienced by patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA): A qualitative study. International Journal of Nursing Studies 45(7): 995–1002. DOI: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2007.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritchie Jane, Lewis J. (2003) Qualitative Research Practice : A Guide for Social Science Students and Researchers. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications. Available at: https://books.google.co.uk/books?hl=en&lr=&id=IZ3fJlD5x8gC&oi=fnd&pg=PA109&dq=designing+fieldwork+strategies+and+materials+2003+arthur+and+nazroo&ots=e2QCaU6BWa&sig=xyQbvzWHHCpmvAiHPkeMPjx299I#v=onepage&q&f=false (Accessed 11 October 2018). [Google Scholar]

- Rooy EC, Toner BB, Maunder RG, et al. (2001) Concerns of patients with inflammatory bowel disease: results from a clinical population. The American Journal of Gastroenterology 96(6): 1816–1821. DOI: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.03877.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan G, Bernard R. (2000) Data Management and Analysis Methods. In: Denzin NK, Lincoln YS. (eds) Handbook of Qualitative Research. 2nd Edition. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications. 769–802. DOI: 10.2307/2076551. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sainsbury A, Heatley RV. (2005) Review article: psychosocial factors in the quality of life of patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics 21(5): 499–508. DOI: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2005.02380.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sammut J, Scerri J, Xuereb RB. (2015) The lived experience of adults with ulcerative colitis. Journal of Clinical Nursing 24: 2659–2667. DOI: 10.1111/jocn.12892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverman D, Silverman D. (2013) Doing Qualitative Research: A Practical Handbook. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Skrautvol K, Naden D. (2017) Tolerance limits, self-understanding, and stress resilience in integrative recovery of inflammatory bowel disease. Holistic Nursing Practice 31: 30–41. DOI: 10.1097/HNP.0000000000000189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swain MG. (2000) Fatigue in chronic disease. Clinical Science 99(1): 1–8. DOI: 10.1042/CS19990372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka M, Kazuma K. (2005) Ulcerative colitis: Factors affecting difficulties of life and psychological well being of patients in remission. Journal of Clinical Nursing 14: 65–73. DOI: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2004.00955.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The World Health Organization (1995) The World Health Organization quality of life assessment (WHOQOL): position paper from the World Health Organization. Social Science & Medicine. DOI: 10.1016/0277-9536(95)00112-K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas PW, Thomas S, Kersten P, et al. (2014) One year follow-up of a pragmatic multi-centre randomised controlled trial of a group-based fatigue management programme (FACETS) for people with multiple sclerosis. BMC Neurology 14(1): 109. DOI: 10.1186/1471-2377-14-109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Todorovic V. (2012) Providing holistic support for patients with inflammatory bowel disease. British Journal of Community Nursing 17: 466–472. DOI: 10.12968/bjcn.2012.17.10.466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Townsend A, Wyke S, Hunt K. (2006) Self-managing and managing self: practical and moral dilemmas in accounts of living with chronic illness. Chronic Illness 2(3): 185–194. DOI: 10.1177/17423953060020031301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urquhart C. (2013) Grounded Theory for Qualitative Research: A Practical Guide. Thosand Oaks, CA: SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- van der Have M, Brakenhoff LKPM, van Erp SJH, et al. (2015) Back/joint pain, illness perceptions and coping are important predictors of quality of life and work productivity in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: a 12-month longitudinal study. Journal of Crohn’s and Colitis 9(3): 276–283. DOI: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jju025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Houtum L, Rijken M, Groenewegen P. (2015) Do everyday problems of people with chronic illness interfere with their disease management? BMC Public Health 15(1): 1000. DOI: 10.1186/s12889-015-2303-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warburton DER, Nicol CW, Bredin SSD. (2006) Health benefits of physical activity: the evidence. Canadian Medical Association Journal 174: 801–809. DOI: 10.1503/cmaj.051351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinert C, Cudney S, Spring A. (2008) Evolution of a conceptual model for adaptation to chronic illness. Journal of Nursing Scholarship 40: 364–372. DOI: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2008.00241.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiles R, Crow G, Charles V, et al. (2007) Informed consent and the research process: following rules or striking balances? Sociological Research Online 12: 99–110. DOI: 10.5153/sro.1208. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Woodward S, Dibley L, Combes S, et al. (2016) Identifying disease-specific distress in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. British Journal of Nursing 25: 649–660. DOI: 10.12968/bjon.2016.25.12.649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Medical Association (1996) Declaration of Helsinki 1996 – WMA – the World Medical Association. Ferney-Voltaire, France: World Medical Association. Available at: https://www.wma.net/what-we-do/medical-ethics/declaration-of-helsinki/doh-oct1996/(Accessed: 24 October 2018). [Google Scholar]