Abstract

Background

Lymphoedema is a chronic condition that is estimated to affect up to four people per 1000 of the UK population with this increasing with age. Men account for up to 20% of lymphoedema service caseloads with research focussing upon women affected.

Aims

To retrieve primary qualitative research on the experiences of men with chronic lymphoedema.

Methods

A qualitative review was undertaken using the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) meta-aggregation method. A search strategy was applied to 12 databases, from inception to February 2021, with 22 studies identified and appraised. The findings were extracted and synthesised via the JBI approach.

Results

Four synthesised findings were identified: (1) The ‘New Norm’, how diagnosis led to men being faced with a ‘new version’ of themselves; (2) ‘Journey into the Unknown’ relates to the unforeseen diagnosis of the condition; (3) ‘Access’ – challenge in receiving a diagnosis, and support; and (4) ‘Personhood’ – the impact of the condition upon external constructs and relationships.

Conclusions

Men are faced with similar challenges as women coupled with societal expectations with respect to gender identity and expression. This leads to those wishing to engage with men to adopt ‘gender-based tailoring’ within healthcare services, information and support.

Keywords: chronic, lymphoedema, men, narrative, oedema, qualitative

Introduction

Chronic oedema is an umbrella term for what is a long-term condition (LTC), in which lymphoedema is a sub-category, with lymphoedema containing other categories, such as primary and secondary (Rankin, 2016). Primary (intrinsic) is due to developmental abnormalities within the lymphatics, such as Milroy’s or Turners; this condition is estimated to affect between one in 2763 and up to one in 8000 people in the United Kingdom (UK) (Cooper and Bagnall, 2016; ILF, 2006; Rankin, 2016). Secondary (extrinsic) is linked to damage to the existing lymphatic system, such as infection, cancer or surgery, with this representing the most reported diagnosis within lymphoedema caseloads (Cooper and Bagnall, 2016; ILF, 2006; Rankin, 2016). It is estimated that between 140 and 250 million people across the world are affected by lymphoedema, with this figure being up to four people per 1000 of the UK population, with 20% of cases involving men, with incidence increasing with age (Cooper and Bagnall, 2016; Moffatt et al., 2019b). This qualitative systematic literature review aims to address an imbalance in the current evidence base between men and women diagnosed with lymphoedema.

Methods

This qualitative systematic review utilised the meta-aggregation approach to synthesise the best available evidence (Lockwood et al., 2020; Table 1). This approach was adopted following a scoping exercise, that led to no other systematic reviews being identified within this subject area. It also led to retrieval and review of primary research studies that lacked depth and richness required for other approaches, such as meta-ethnography (Booth et al., 2013). Meta-aggregation has been described as having similarities with the Cochrane and Campbell guidance for quantitative systematic reviews, which takes a pragmatic approach that is preferred by policymakers and clinicians (Lockwood et al., 2020).

Table 1.

Joanna Briggs Institute 5-stage approach to meta-aggregation.

| Stage | Details | Evidence |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Critical appraisal – All included studies were subject to critical appraisal prior to data extraction. This also included a review of the credibility and dependability of the studies included. | Joanna Briggs Institute Critical Appraisal Tool |

| 2 | Extraction – Study characteristics were extracted including study methods, phenomenon of interest, theme and sub themes (verbatim and illustrative quote). | Joanna Briggs Institute Qualitative Extraction Tool |

| 3 | Categorisation – The results of the studies (themes and sub-themes) were initially grouped and then given a categorisation. | Joanna Briggs Institute Meta-Aggregation Approach |

| 4 | Synthesised findings – The categories generated then lead to the creation of ‘synthesised findings’ that provide a comprehensive and representative conclusion to the categories. | Joanna Briggs Institute Meta-Aggregation Approach |

| 5 | Evidence level – Each study that forms parts of the synthesised finding was given a designated evidence levels of 1) unequivocal (open to challenge), 2) credible (interpretation) and 3) unsupported (no supporting evidence) – this relates to themes being supported by citations or interview excerpts provided by participants. This is then taken into account for the ConQual score regarding the confidence for each finding. | Joanna Briggs Institute Meta-Aggregation Approach and ConQual |

Search strategy and appraisal

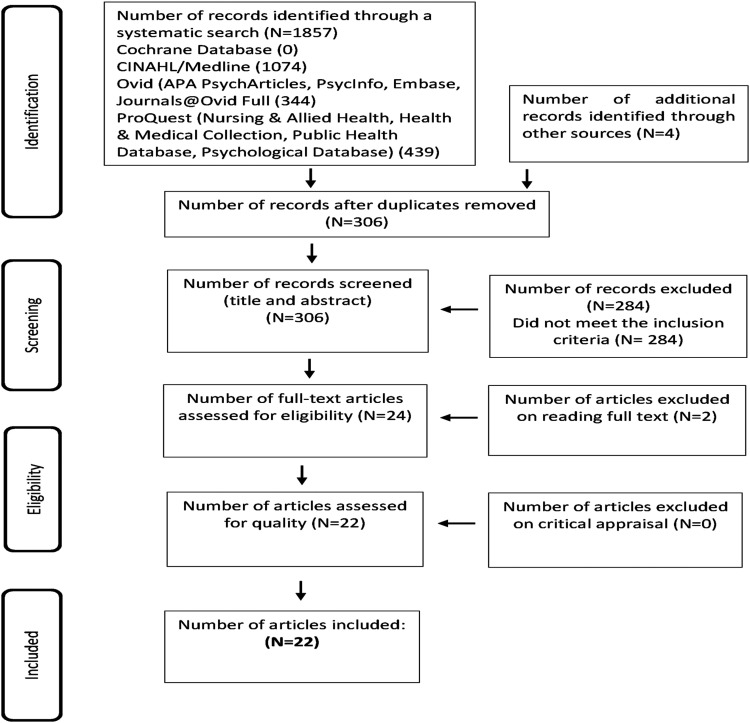

The review applied a two-stage approach following question generation and construction as shown within Table 2. This built upon the previous scoping exercise, in terms of the search strategy, such as MESHterms, and identifying keywords from articles, which were applied within PEOT (population, exposure, outcome and type) (Bettany-Saltikov, 2016; Table 2). This approach led to multiple combinations via Boolean terms as shown with Table 3 within multiple databases and grey literature sources (Table 3). All retrievals were subject to the inclusion and exclusion criteria (Table 2) after duplication removal with these uploaded into Mendeley (2019) version 1.19.4 and presented in the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) (Lockwood et al., 2020: Figure 1). Twenty-two articles underwent the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) Critical Appraisal Checklist with information taken forward within the JBI Qualitative Data Extraction tool (Lockwood et al., 2020; Tables 4 and 5).

Table 2.

Review question breakdown, inclusion/exclusion criteria for retrievals.

| Question? | To establish the perceptions of male patients diagnosed with lymphoedema from a biopsychosocial perspective? | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Population | Adult men over the age of 18 years old | ||

| Exposure | Diagnosed with lymphoedema | ||

| Outcomes | Perceived impact of their conditions from a biopsychosocial perspective | ||

| Types | Qualitative research and the varying research designs including meta-ethnography reviews | ||

| Details | Inclusion | Exclusion | |

| Date range | Any year up until 2020 | n/a | |

| Gender | Men, or combined with females | Female only | |

| Geography | Worldwide | n/a | |

| Language | English text | Non-English text | |

| Condition | Diagnosed with lymphoedema, primary, secondary, and chronic oedema | Not diagnosed with lymphoedema, or its sub conditions | |

| Types | Qualitative research/Literature/reviews/meta-ethnography | Quantitative | |

| Two-stage process | |||

| (1) | Title and abstract review | Ascertain relevance based upon keywords, inclusion, and exclusion criteria, set against the research question | |

| (2) | Full texts review and duplication removal | Establish suitability based upon the inclusion and exclusion criteria, plus research question for further review/appraisal | |

Table 3.

Search strategy table – keywords, Boolean combinations and databases.

| Boolean | No | P | No | E | No | O | No | T |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| or | 1 | Male | 12 | Lymphoedema | 27 | Experiences | 44 | Qualitative |

| or | 2 | Man | 13 | Lymphedema | 28 | Life experiences | 45 | Qualitative research |

| or | 3 | Men | 14 | secondary lymphedema | 29 | Narratives | 46 | Qualitative approach |

| or | 4 | Man’s | 15 | secondary lymphoedema | 30 | Stories | 47 | Qualitative Method? |

| or | 5 | Men’s | 16 | chronic oedema | 31 | Perceptions | 48 | Qualitative Methodolog? |

| or | 6 | Adult Male | 17 | chronic edema | 32 | Perception | 49 | Qualitative stud? |

| or | 7 | Adult men | 18 | Primary lymphoedema | 33 | Attitude | 50 | Qualitative inquiry |

| or | 8 | Adult Man | 19 | Primary lymphedema | 34 | Attitudes | 51 | Narrative inquiry |

| or | 9 | Adult men’s | 20 | Cancer related lymphoedema | 35 | Quality of life | 52 | Narrative research |

| or | 10 | Adult man’s | 21 | Cancer related lymphedema | 36 | well-being | 53 | Narrative stud? |

| or | 11 | AND | 22 | Non cancer related lymphoedema | 37 | View | 54 | Narrative analysis |

| 23 | Non cancer related lymphedema | 38 | beliefs | 55 | Ethnography | |||

| 24 | Lower limb lymphoedema | 39 | live experience | 55 | Auto Ethnography | |||

| 25 | Lower limb lymphedema | 40 | perspective | 56 | Phenomenology | |||

| 26 | AND | 41 | Findings | 57 | Grounded theory | |||

| 42 | Accounts | 58 | Case stud? | |||||

| 43 | AND | 59 | AND | |||||

| Combined | 11+26+43+59 (AND) | |||||||

| Databases | Cinahl, Medline, Nursing and Allied Health Database, Psychology Database, PTSD pubs, Public Health Database available via ProQuest. APA PsychArticles, Journals@Ovid, Embase, Ovid Meline, APA Psych info available via Ovid. This extended to the retrieval of grey literature, sources from open grey EU and EThOS offered from the British Library, and Google Scholar | |||||||

Figure 1.

PRISMA flowchart indicating the phases that formed the systematic review

Table 4.

Data extraction table for included studies.

| Study | Country | Title | Phenomena of interest | Methodology/Method | Setting/context/culture | Participant characteristics and sample size | Research notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bogan et al. (2007) | USA | Experiences of living with non-cancer-related lymphoedema: Implications for clinical practice | The purpose of this study was to gain insight into the perspective of individuals with non-cancer-related lymphoedema to increase understanding of their experiences and, thereby, enhance treatment and guidance by healthcare professionals. | Qualitative – Qualitative approach within a naturalistic inquiry. Semi-structure interview with guide/open questions, broad themes with interviews audio recorded and transcribed with field notes. Analysis – was completed via content analysis and ethnography. Male and female integrated into one account. | Patients own home, diagnosed with non-cancer related lymphoedema or primary lymphoedema, who were or had received inpatient treatment in a regional hospital. | Purposive sampling, 7 participants (3 male and 4 female, 5 White, 1 Black, 1 Alaskan Indian), bilateral leg oedema (5), unilateral leg oedema (1), bilateral leg oedema and hand (1). Age (mean) 52 years, range 36–75 years, inpatient involvement 3 years, and discharge 8 months to 5 years. | No application to gender. |

| Results | Three comprehensive themes emerged with sub themes identified: Three themes emerged: (1) nowhere to turn, (2) turning point and (3) making room | ||||||

| Borbasi et al. (2004) | Australia | Getting it together: men’s and their carers' experience of lymphoedema | The meaning and understanding of the experiences of men diagnosed and living with lymphoedema. | Semi structured interviews which lasted between 30 and 60 min, which audio taped and transcribed. | Men and their partners following the development of secondary lymphoedema related to surgery. | Over 18 years diagnosed with secondary lymphoedema following surgery and their spouses. | No application to gender. |

| Results | Four broad themes emerged from the data: (1) the nature of lymphoedema; (2) sequelae of lymphoedema; (3) scarcity of information about lymphoedema and 4) spouses' perspectives. | ||||||

| Crow (2020) | USA | Illuminating the experiences of growing up and living with primary lymphoedema: a life history story. | The purpose of the qualitative research study was to collect, preserve, and understand the life histories of young adults who grew up with and are living with primary lower limb lymphoedema in the USA. | Qualitative – Life histories related to interpretivist paradigm embedded within social constructivism. This led to the use of guided conversations as part of the life history story telling. | Men and women diagnosed with primary lymphoedema in the lower limbs. | Purposive sampling participants – 5 (4 women and 1 man) age range of 19–40 years, diagnosed with primary lymphoedema. | Social constructivism, mentioning of a gendered lens (sociocultural/medica-historical contexts). |

| Results | (1) striving to matter to and for others and self; (2) complexities, complications, and confusions: Life difficulties along the journey and (3) lymphie conundrums: Grappling with normalising/othering. The first includes sub-themes about mattering to significant others, healthcare providers, others with primary lymphoedema and to self. The second includes sub-themes about the complexities of decongestive therapy and self-management, schooling, other chronic diseases, and other priorities that push lymphoedema to the background, the complications of biographical disruption and transformative brushes with cellulitis and lingering confusions about cause and heritability. The third includes sub-themes about stigmatisation, rejection, and discrimination, hiding to pass as ‘normal’ and its costs and straddling the lymphie conundrum with clothing. | ||||||

| Deng and Murphy (2016) | USA | Lymphoedema self-care in patients with head and neck cancer: a qualitative study. | Reporting head and neck cancer patients’ perceived lymphoedema: Self-care education: Self-care practices Self-care suggestions. |

Mixed methods – semi structured interviews which lasted between 30 and 60 min, which audio taped and transcribed. | Men and their partners following the development of secondary lymphoedema related to surgery. | 20 participants – male 65% (n=13) and women 35% (n=7), 100% White, diagnosis and cancer was also present majority 50% were oropharynx location stage 4. | No application to gender. |

| Results | Themes generated related to the aims – Aim 1: Perceived lymphoedema self-care education components – (1) components of self-care education, (2) positive comments of self-care education and (3) insufficient or inappropriate information on self-care education; aim 2: reported lymphoedema self-care practices levels of engagement and methods; Aim 3: suggestions on lymphoedema self-care. | ||||||

| Frid et al. (2006) | Sweden | Lower limb lymphoedema: Experiences and perceptions of cancer patients in the late palliative stage. | The aim of this study was, therefore, to explore patients' experiences and perceptions regarding the influences of LLL, and how they manage this in the late palliative stage. | Qualitative – Phenomenology, semi-structured interviews, open ended questions – experiences and thoughts about having lower limb lymphoedema (LLL). Analysis – phenomenographic approach using second order perspective rather than first. | Outpatient clinic who were diagnosed with cancer related lymphoedema who were palliative. | Participants – 13 (9 women and 4 men), diagnosis cancer related lymphoedema and who were palliative (pancreatic – 2, cervical – 2, renal – 1, breast – 1, prostate 3, adrenal – 1, lung – 1, unknown origin – 1, cecal – 1), recruited from three different clinics in Stockholm and via ‘maximum variation sampling strategy, interview and death (12–168 days), severity mild – 4, moderate – 3, severe – 6. | No application to theory, or gender. |

| Results | Four main categories were identified: (1) the future – hope – the patients were aware that the LLL was permanent, but still they held hope for improvement, (2) the physical aspects – discomfort and disgust – related to the appearance of the limb. (3) interactions with others – persons' reactions affected the way in which they perceived their limb. (4) efforts – made by staff had a great influence on the patient’s situation, (5) dealing with problems – to adapt oneself – or not – (6) control through knowledge – but also avoidance strategies. | ||||||

| Hamilton and Thomas (2016) | Canada | Renegotiating hope while living with lymphoedema after cancer: a qualitative study. | The purpose of the present analysis, then, was to assess the hope experiences of individuals living with SLC (including underrepresented groups such as men and those with lower limb SLC), an area which has been unexamined. | Qualitative – Qualitative approach – semi-structured interviews, open ended questions – experiences and thoughts about having lower limb lymphoedema (LLL). Analysis – phenomenographic approach using second order perspective rather than first. | Clinic and people’s home via the telephone and who were diagnosed with cancer related lymphoedema and self-managing. | Participants – 13 from two sites on Fredericton and Ottawa which included 11 women and 2 men. The age range is between 31 and 77 years with a diagnosis of cancer ranging from 2 to 34 years with a mean of 10 years with CRL diagnosis being 1–11 years with a mean of 8.5 years. Cancer diagnosis, cervical – 1, breast 6, melanoma 4, endometrial 1, prostate, and colorectal 1. Eight lived in an urban are with five working full time. | Hope based theory, No gender theory |

| Results | Four themes emerged: (1) renegotiating hope in the context of a chronic condition – one striking finding was that participants struggled to articulate what hope meant, even though the term is popularly; (2) the objects of hope – when participants were asked generally about hope, they most often oriented towards a description of the objects of their hope; (3) hope as an outcome – while some participants struggled to define what hope was, they were much more capable of discussing hope as an outcome – or the factors that contributed to hope; (4) hope as action – while the distinction between coping and hope is subtle when exploring hope as action, it is important to note that participants talked about acting as a way of living hopefully | ||||||

| Jeans et al. (2019) | Australia | Patient perceptions of living with head and neck lymphoedema and the impacts to swallowing, voice and speech function. | The aim of this study is to explore the experiences of patients with HNC who have HNL following treatment and examine their perceptions of the impact of HNL on their swallowing, voice and speech function. | Qualitative – Qualitative approach, semi-structured – face to face (6 people) and telephone (7 people), with a socio-demographic and illness questionnaire administered, followed by a series of open-ended questions. The answer to these questions was audio recorded. Analysis – led to the preliminary coding through NVivo 10 reflexivity was considered through debriefing sessions to discuss and refine interpretations. | Secondary setting/hospital/maxillofacial | 12 participants – male 66.7% (n=8) and female 33.3% (n=4), 50% had either neck dissection or not, with almost a 50% split between tumour and node staging. | No application to theory, or gender. |

| Results | Four themes: (1) it feels tight; (2) it changes throughout the day; (3) it requires daily self-monitoring and management and (4) it affects me in other ways. | ||||||

| Maree et al., (2016) | South Africa | ‘Just live with it’: Having to live with breast cancer related lymphoedema. | The objective of the study was therefore to explore how people living with breast cancer related lymphoedema experience this complication. | Qualitative – Qualitative approach, unstructured interview an opening question asked, ‘Please tell me what it is like for you to live with lymphedema’, conducted in Afrikaans or English, and audio taped. Teschs open coding was undertaken to reach data saturation. Reflexivity was mentioned as being continuous in the study. | Lymphoedema initiative at a university to explore breast cancer related lymphoedema in men and women. | Purposive sampling, eight women and one man. The age range was 43–61 years with the average being 61 years. Seven with Afrikaans, one Greek and one Tswana. Six participants had stage two, one had stage two to three and two had stage three lymphoedema. The presence of oedema was between two to 60 months. | Roy Adaptation Model of Nursing (biopsychosocial). |

| Results | Four themes emerged: Theme 1: ‘Just live with it’: Lymphoedema the unknown and unspeakable, Theme 2: ‘My arm is painful’: Living with the physical consequences of lymphoedema, Theme 3: ‘You cannot hide it’: living with an altered body and Theme 4: ‘I am grateful’: Coping with the lymphoedema. | ||||||

| McGarvey (2014) | Australia | Lymphoedema following treatment for head and neck cancer: impact on patients, and beliefs of health professionals. | This study aimed to explore the relationships between: How lymphoedema affects head and neck cancer patients. Beliefs of medical and health professionals regarding which patients might be more at risk of developing lymphoedema, How it affects patients, How lymphoedema might be effectively managed. |

Qualitative – Study design unclear – semi-structured interview (one-on-one), interview schedule/guide, audio recorded (unclear), transcribed verbatim (no software stated), codes/themes (no mention of the framework applied), 2nd researcher involved in the code/theme generation. | Secondary setting/hospital/maxillofacial | 20 participants, 10 patients (8 male and 2 female), age range 32–75 years, mean age 60 years 10 healthcare professionals – n=2 consultant maxillofacial surgeons, n= 1 dietitian, n= 1 speech pathologist, n=2 physiotherapist, n=1 radiation therapy nurse and n=1 head and neck co-coordinator. No statement of gender, age, experience or qualifications. | No application to theory, or gender. |

| Results | The results 6 themes related to patients with a further 3 related to healthcare professionals: Patients: (1) physical effects of lymphoedema, (2) diurnal pattern, (3) tightness and reduced cervical spine range of motion, (4) mucous secretions and swallowing, (5) psychosocial aspects (negative body image) and (6) strategies to assist with facial lymphoedema. Healthcare professionals: (1) clinical features, (2) beliefs about the effects of secondary lymphoedema and (3) management strategies. | ||||||

| Meiklejohn et al. (2019) | Australia | How people construct their experience of living with secondary lymphoedema in the context of their everyday lives in Australia. | The purpose of this study was to apply a social constructivist approach to explore how men and women construct their experiences living with lymphoedema following treatment for any cancer in the context of everyday life. | Qualitative – Qualitative approach, focus group and telephone interviews with all other participants, with two to four participants in each group. Interview guide with open-ended questions (questions provided). Analysis – Interviews were transcribed verbatim and transcripts were imported into NVivo8 qualitative software, in accordance with the constructivist grounded theory, initial, focused, and theoretical coding were performed. | Secondary setting/hospital following cancer treatment. | Participants were 29 in total with men (n=3) and female (n=26), age median 63 years (range 39–80 years). Majority (n=20) were breast cancer related diagnosis. | Social constructionism and social constructivist framework. |

| Results | Three conceptual categories were developed from the data. (1) altered normalcy – physical and psychosocial effects of lymphoedema and their impact on everyday life, (2) accidental journey – explores the secret society of having a lymphoedema diagnosis and the importance of finding a healthcare professional and (3) ebb and flow of control elements that influenced participants’ perceived control over lymphoedema. Core category – sense of self. | ||||||

| Michael et al (2016) | Australia | The experiences of prostate cancer survivors: Changes to physical function and its impact on quality of life. | The aim of this research is to help understand the experience of prostate cancer survivors in relation to physical function and how these changes impact on prostate cancer survivors’ quality of life. | Qualitative – Phenomenology, semi-structured interviews, verbatim transcripts, thematic content analysis, reflexivity/member checking and 3rd part verification were stated. | Prostate Cancer Support Group for those whom had received treatment. | Purposive sampling – 7 men, mean age 64.5 years (51–83 years, despite the work stating 41–80 years). Five men were married, one divorced and one widowed, with diagnosis ranging from 1993 to 2010. Radiotherapy was received by 3 men, with 4 receiving prostatectomy. | No application to theory, or gender. However, masculinity was mentioned, and related to other research studies. |

| Results | The main themes generated were (1) masculinity – related to physical changes, (2) loss of control of over daily lives – related to incontinence and impotence and (3) age-specific perspectives – this considered employment. | ||||||

| Nixon et al. (2018) | Australia | A mixed methods examination of distress and person-centred experience of head and neck lymphoedema. | Examine distress and QoL in people undertaking a 22-week HNL treatment program following treatment for HNC Explore the person’s experience of HNL and distress and the impact on day-to-day functioning following completion of HNL treatment. |

Mixed methods, QoL: was assessed using EORTC QLQ and H&N43, with these subject to Freidman test, with pairwise comparisons and Bonferroni correction, Wilcoxon signed rank test, SPSS version 22. A single semi-structured interview was conducted 10–22 months after completion of the 22-week HNL treatment, once the data from. An eight-question interview guide, analysis of the interviews was conducted using the model proposed by Braun and Clarke. | Secondary setting/hospital/maxillofacial | 10 participants – male (n=9) and female (n=1), age 65.1 (mean) with a range of 42–89 years, inclusion and exclusion criteria stated, convenience sampling appears to be present, due to the location, but is stated directly in this article. | No application to theory, or gender. |

| Results | The six main themes were: (1) the psychosocial impact; (2) the physical experience and pattern/timing; (3) experience of receiving treatment; (4) day-to-day distress; (5) supports that helped manage distress and (6) adjustment to a ‘new normal’. The three sub-themes were (1) emotional, (2) appearance changes and 30 socialisations. | ||||||

| Perera et al. (2007) | Sri Lanka | Neglected patients with a neglected disease? A qualitative study of lymphatic filariasis. | The objective of the study was to inform future interventions and policy to help these vulnerable, neglected people. By doing so, it responds to needs for specific research identified in the most recent review of the sociocultural aspects of filariasis. | Qualitative – Qualitative approach, semi-structured, guided interviews in the local language, Sinhalese. Interviewers worked in single-sex pairs: one conducting the interview, the other recording the responses manually. Interview notes were transcribed and later translated into English for analysis. Analysis – An adaptation of the affordability ladder framework was employed to organise and analyse the data. | The infection currently endemic in Sri Lanka due to W. bancrofti and is presently confined to eight districts in the southern, western, and north-western provinces [20]. Our study took place in three villages in Matara and one in Galle in 2004–2005. Reference to lymphoedema n Sri Lanka has been traced to the 13th century AD. | Purposive sampling to select 60 (29 men and 31 women with filarial lymphoedema, 45 with filarial elephantiasis and 15 men with filarial hydrocoele) from the south of Sri Lanka in 2004–2005. Participants were selected by poverty status, sex and lymphoedema stage. Low income (male 4 and 11 women), middle income (male 8 and female 13), and high income (male 2 and female 7). A separate sample of 15 men with filarial hydrocoele. | An adaption of the healthcare affordability ladder framework, but no application to gender theory. |

| Results | Reference ladder (illness) – (1) delayed diagnosis was common and had irreversible consequences, (2) household economy ladder – struggling to find work and (3) impact ladder – The stigma associated with LF was a dominant theme | ||||||

| Río-González et al., 2018 | Spain | Living with lymphoedema – the perspective of cancer patients: a qualitative study. | To illuminate the impact of LE on-cancer patients’ lives through their experiences, perspectives, challenges and barriers. | Qualitative – Phenomenology, stage 1 – unstructured interview with an ‘What is your experience with lymphoedema?’ and stage 2 semi-structured interviews with a question guide developed following stage 1. All interviews were tape recorded and transcribed verbatim. Researcher field notes were used. Analysis – thematic analysis undertaken, no data analysis software was used. Rigour – Guba and Lincoln for establishing trustworthiness of the data. | Two outpatient physiotherapy clinics focussing on people men and women diagnosed with cancer related lymphoedema. | Purposeful sampling, 11 participants being recruited between 2014 and 2016 (1 male and 10 female). | No application to theory, or gender. |

| Results | One main theme and four sub themes emerged: (1) living a life with multiple barriers – subthemes: (1a) discovering physical and psychological barriers – (1b) searching information, (1c) uncomfortable moments, (1d) building relationships – the social barriers, (1e) controlling expenses. | ||||||

| Shakespeare, L (2012) | Scotland | Lymphoedema in a remote and rural area: An investigation into the prevalence of lymphoedema and its effect on daily living and quality of life in a remote and rural area in the far north of Scotland. | To estimate the prevalence of lymphoedema/chronic oedema and to investigate the characteristics of the condition in a very remote and rural area of Scotland and to explore the experience of a sample of people living with the condition in that area. | Mixed methods – Stage 1 quantitative data collection (GP survey), stage 2 – Individual survey with closed and open questions, stage 3 – semi-structured interviews. | GP practice survey (stage 1), with survey sent to individuals via the GP (stage 2). Telephone interview with participants (stage 3). | Stage 1 – GP lymphoedema prevalence survey = total 17 GP practices. Stage 2 – Patient characteristics of lymphoedema = total 49 (10 male and 39 female). Stage 3 – Semi-Structured interviews = total 10 male 1 and 9 female. |

No application to gender theory |

| Results | In stage 3 (interviews) this led to the identification of five themes: (1) physical effects of lymphoedema on everyday life, (2) psychological effects, (3) treatments, (4) knowledge about lymphoedema and (5) provision of information about lymphoedema. | ||||||

| Stolldorf et al. (2016) | USA | A comparison of the quality of life in patients with primary and secondary lower limb lymphoedema: A mixed-methods study. | The purpose of this study was to describe and compare the impact of the symptoms of lower-limb lymphoedema and the associated symptom intensity and distress on the quality of life of patients by lymphoedema type. | Mixed methods – web-based survey (demographics, Lymphedema Symptom Intensity and Distress Survey-Leg (LSIDS-L), and one open-ended qualitative question). Participants’ responses to the qualitative, open-ended question were analysed using ATLAS.ti, (version 6.0; Dowling). | Online web-based questionnaire derived from a validated tool and followed by open ended question | Participants – 213 participants. Four categories of participants by lymphoedema type emerged: primary lymphoedema (n=96, 45%), secondary cancer-related lymphoedema (n=37, 17%), secondary non-cancer-related lymphoedema (n=45, 21%), and lymphoedema of unknown causation (n=35, 17%). Lower-leg lymphoedema of unknown origin were not included due to the ambiguity of lower-limb lymphoedema. Participants were predominantly female (n=159, 89.3%) male (n= 54), employed full-time (n=75, 42.1%), and with lymphoedema in both legs (n=72, 40.4%). | No application to theory, or gender. |

| Results | Qualitative outcomes: 1) impacting psychosocial well-being altering body image that impacts their psychological and social well-being, 2) lacking resources – lack the financial resources, and availability of lymphoedema practitioners, 3) physical and functional impairments – physical consequences and functional impairments, and 4) treatment and care – care by others and self-care, problems, and challenges. | ||||||

| Thomas and Hamiton (2014) | Canada | Illustrating the (in)visible: Understanding the impact of loss in adults living with secondary lymphoedema after cancer. | To explore experiences of loss and hope in men and women living with SLC. | Qualitative – interpretive descriptive design, a brief questionnaire (socio-demographics, cancer and SLC diagnoses, and treatment). Semi structured interview guide. Analysis – interpretive description draws on several methodological strands, including contemporary phenomenology (Thorne, 2008), within the software program, NVivo 10. | The project was based out of two research sites (Fredirection, NB, and Ottawa, ON). | Participants – 13 (11 women, 2 men) ranged from 31 to 77. Eight of the 13 participants lived in urban areas. Five participants were working full-time. Participants had been diagnosed with cancer from 2 to 34 years (mean 10 years) prior to being interviewed. Six participants had breast cancer, four had melanomas, and three had reproductive cancers. Participants had been diagnosed with SLC from less than 1 year to 11 years post-cancer diagnoses (mean 8.5 years). Seven participants had lower limb SLC, while 6 were experiencing upper limb SLC. | No application to theory, or gender. |

| Results | Three key themes emerged: Theme 1 – (in)visibility and appearance, Theme 2 – (in)visibility and action, is connected to function and Theme 3 – (In)visibility of the present and future – loss of the present). | ||||||

| Towers et al., 2008 | Israel | The meaning of success in lymphoedema management. | What do people with lymphoedema consider to be the meaning of success in the intensive phase of lymphoedema management? What do people with lymphoedema consider to be the meaning of success in the long-term phase of lymphoedema management? |

Qualitative – Phenomenology, semi-structured interviews and followed an interview guide. | Maccabi Healthcare System in the south district of Israel and with those diagnosed with cancer related lymphoedema who had received intensive treatment and now had moved to maintenance therapy. | Purposive sampling, total 10 = 3 male and 7 female. Time since diagnosis being 1–35 years. | Biopsychosocial model (Armer). No application to gender theory. |

| Results | Two themes emerged from the data: (1) detachment and bad feelings/experiences immerged and (2) lack of clarity as to moving to long-term phase of treatment – The second aim meaning of success in the maintenance (long-term) phase. Two themes: (1) empowerment – ‘not getting worse’, ‘stable’, ‘maintain’ and the goal of maintaining, she said: Expectations – they talked about acceptance, about having no other choice, but dealing with their condition. | ||||||

| Towers et al., 2008 | Canada | The psychosocial effects of cancer-related lymphoedema. | Seek further understanding of the psychosocial context of the suffering in those with cancer related lymphoedema. | Qualitative – Phenomenology, semi-structured interviews with open ended questions were used in the interview which followed the interview guide. Analysis – the content analysis approach was used once all verbatim transcription was completed. | To recruit and interview men and women with cancer induced lymphoedema from hospital based lymphoedema service, local therapists and lymphoedema association and support group. | Participants – 19–11 patients (10 female and 1 male) and 8 spouses, with diagnosis related to breast cancer (9), melanoma (1) and penile (1), affecting arm (9) and leg (3 with 1 unilateral and 2 bilateral). Age range 50–75 years with a mean of 63.7 years. | No application to theory, or gender. |

| Results | Four themes emerged from the data: (1) frustration with lack of financial support from government and insurance companies, (2) being alone with this life-long problem: This related to conflicting information on the subject and treatment options and limited knowledge by physicians and society, (3) the burden of living with a swollen limb: this focused upon the realisation that the condition was chronic and (4) the importance of support systems: spouses, peer support groups and exercise sessions. | ||||||

| Viehoff et al. (2016) | Netherlands | Functioning in lymphoedema from the patients’ perspective using the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and health (ICF) as a reference. | The aim of this study is to determine relevant aspects of functioning as well as relevant environmental and personal factors from the lymphoedema patients’ perspective and to quantify these using the ICF. | Qualitative – Qualitative approach, six different focus groups were used, each with 3–8 participants. These groups consisted of patients with: (A) lymphoedema with non-oncology background (mixed locations), (B) lymphoedema with oncology background (mixed locations), (C) lymphoedema of the upper limb (mixed causes), (D) lymphoedema of the lower limb (mixed causes), (E) lymphoedema in the genital region (mixed causes) and (F) lymphoedema in the head and neck region caused by cancer treatment. Analysis – the data analysis was conducted in four steps and followed the method of ‘meaning condensation’ with step four, each MC was linked to one or more ICF categories. | Outpatient location and with individuals that had been diagnosed with cancer or non-cancer related lymphoedema. | Patients were recruited from five different centres during 2012–2013. Stucki and Cieza. Thirty-one patients were recruited (men 10 and women 21), with a mean age of 55 years and locations ranging from upper limb (7), lower limb (11), midline (5), mixed locations genital (6) and breast/upper limb (2). Lymphoedema related to cancer (18) and non-cancer related (13) with 15 employed in work. | ICF Framework, but no application to theory, or gender. |

| Results | Body function – the top five frequently mentioned categories were 1) ‘b435, Immunological system functions’, (impairments in the lymphatic system); 2) b152, Emotional functions’ (emotions such as fear, anger, joy); 3) b280, Sensation of pain’; 4) b126, temperament and personality functions’ (including psychic stability, confidence and optimism); and 5) ‘b840, Sensations related to the skin’ Body Structures – the top five mentioned categories were 1) ‘s750, Structure of lower extremity’; 2) ‘s730, Structure of upper extremity’; 3) ‘s630, Structure of reproductive system’; 4) ‘s710, Structure of head and neck region’; and 5) ‘s760, Structure of trunk’. Activities and participation – the top five categories identified were 1) ‘d920, Recreation and leisure’; 2) ‘d415, maintaining a body position’ (lying, sitting, standing, etc.), 3) ‘d570, Looking after one’s health’ (ensuring comfort, maintaining health, and managing diet and fitness); 4) ‘d450, Walking’; and 5) ‘d475, Driving’. In focus group C (upper limb lymphoedema with mixed backgrounds), 1) ‘d640, doing housework’ occurred most frequently, whereas 2) ‘d415, maintaining a body position’ occurred most frequently in the genital lymphoedema group (E). Environmental factors – 1) ‘e115, Products and technology for personal use in daily living’ prostheses); 2) ‘e580, Health services, systems and policies’, 3) ‘e355, Health professionals’; 4) ‘e310, Immediate family’; and 5) ‘e110, Products and substances for personal consumption’. Personal factors can be broadly divided into sociodemographic factors (including gender and race), personal living situations and coping strategies. | ||||||

| Watts and Davies (2016) | Wales | A qualitative national focus group study of the experience of living with lymphoedema and accessing local multi-professional lymphoedema clinics. | What is it like to live with lymphoedema in terms of its effect on quality-of-life and well-being? In what ways has access to local lymphoedema clinics made a difference to their lives? |

Qualitative – Qualitative approach, convenience sampling via eight local lymphoedema clinics in Wales. Digitally recorded focus group interviews. Analysis – content analysis (Coffey and Atkinson). | Local lymphoedema clinic with men and women interviewed through focus groups that were mixed gender and causes (cancer and non-cancer related). | Total 59 = 10 male and 49 women with an age range of 22–86 years. Twenty-four participants were diagnosed with cancer (7 men and 18 women) with 34 diagnosed with non-cancer related lymphoedema (3 men and 31 women). | No application or gender theory |

| Results | Themes: (1) it is a battle: Living with lymphoedema, (2) delays in correct diagnosis – (3) the impact of the local specialist led lymphoedema. | ||||||

| Williams et al., 2004 | United Kingdom | A phenomenological study of the lived experience of people with lymphoedema | Explore the lived experiences of people with various types of lymphoedema. | Qualitative – Phenomenology, demographical data was gathered as a baseline from lymphoedema clinic semi-structured interviews, open questions analysis – via the ‘open coding’ offered by Straus and Corbin (1990). | Specialist lymphoedema clinic in London to explore the lived experiences of various types of lymphoedema. | Participants 15 (12 women and 3 men with an age range of 35–89 years with a mean of 57 years. Lymphoedema presentation was 1–41 years. Causes – breast cancer (3), cervical cancer (2), carcinoma penis (1), primary lymphoedema (7), venous insufficiency. | No application to theory, or gender. |

| Results | Three main themes were identified: 1) the experience of lymphoedema diagnosis – 1a) uncertainty, 1b) fishing in the dark and 1c) tension with health-care professionals. 2) experiencing and dealing with lymphoedema – 2a) facing others – the social, 2b) keeping it hidden – difficulties with self-image, 2c) rehearsing the story and learning to open, 2d) making sense of it and 2e) getting on with it – a variety of coping strategies. 3) lymphoedema treatment – 3a) starting on a firm footing, 3b) knowing what I need and 3c) reading my body and judging the effect | ||||||

| Total | 22 | Qualitative appro = 9 Phenomenology = 6 Mixed methods = 5 Unclear = 2 |

Total male = 182 Total female = 425 |

Gender theory = 0 Gendered lens = 1 Biopsychosocial = 1 Social construction = 2 Adaptation model = 1 Adaption framework = 1 |

|||

Table 5.

Joanna Briggs Institute Appraisal Tool and Scoring System.

| Studies/citations | Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | Q5 | Q6 | Q7 | Q8 | Q9 | Q10 | Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| McGarvey (2014) | U | Y | Y | U | U | U | U | Y | Y | Y | 5/10 |

| Frid et al. (2006) | U | U | Y | Y | Y | N | N | U | Y | Y | 5/10 |

| Perera et al. (2007) | Y | U | Y | U | Y | N | N | U | Y | Y | 5/10 |

| Michael et al., 2016 | U | Y | U | Y | Y | U | Y | Y | U | Y | 6/10 |

| Nixon et al. (2018) | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | U | U | U | Y | Y | 7/10 |

| Deng and Murphy (2016) | U | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | U | Y | Y | Y | 7/10 |

| Río-González et al., 2018 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | U | U | Y | Y | 7/10 |

| Stolldorf et al. (2016) | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | U | Y | 7/10 |

| Towers et al. (2008) | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | U | U | Y | U | Y | 7/10 |

| Viehoff et al. (2016) | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | U | U | Y | Y | 7/10 |

| Williams et al., 2004 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | U | Y | Y | 7/10 |

| Meiklejohn et al. (2013) | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | U | N | Y | Y | Y | 8/10 |

| Borbasi et al. (2004) | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | U | U | Y | Y | Y | 8/10 |

| Jeans et al. (2019) | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | U | N | Y | Y | Y | 8/10 |

| Hamilton and Thomas (2016) | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | U | Y | Y | 8/10 |

| Thomas and Hamiton (2014) | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | U | U | Y | Y | Y | 8/10 |

| Towers et al., 2008 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | U | Y | U | Y | Y | 8/10 |

| Watts and Davies, 2016 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | U | Y | U | Y | Y | 8/10 |

| Bogan et al. (2007) | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | U | Y | Y | 9/10 |

| Maree and Beckmann (2016) | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | U | Y | Y | Y | Y | 9/10 |

| Shakespeare, L. (2012) | Y | Y | Y | U | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 9/10 |

| Crow, E. (2020) | Y | Y | Y | U | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 9/10 |

| % | 82 | 91 | 95 | 86 | 95 | 14 | 36 | 55 | 87 | 100 | % |

| Key: | Y (yes), N (no), U (unclear) | ||||||||||

| Questions | 1. Is there congruity between the stated philosophical perspective and the research methodology? 2. Is there congruity between the research methodology and the research question or objectives? 3. Is there congruity between the research methodology and the methods used to collect data? 4. Is there congruity between the research methodology and the representation and analysis of the data? 5. Is there congruity between the research methodology and the interpretation of the results? 6. Is there a statement locating the researcher culturally or theoretically? 7. Is the influence of the researcher on the research, and vice-versa, addressed? 8. Are participants, and their voices, adequately represented? 9. Is the research ethical, according to current criteria, or for recent studies, and is there evidence of ethical approval by an appropriate body? 10. Do the conclusions drawn in the research report flow from the analysis, or interpretation, of the data? |

||||||||||

Data synthesis

Data synthesis was completed through the completion of meta-aggregation supported by the JBI SUMARI (Lockwood et al., 2020; Table 1). After completing the appraisals process, each of the study’s findings was included and then grouped into categories based upon similarity, with an overall synthesised finding formed as a representative conclusion (Lockwood et al., 2020; Tables 1 and 6). Each of the synthesised findings was then given a designation based upon the confidence of that finding, in terms of credibility and dependability that led to a ConQual being generated for each synthesised findings (Lockwood et al., 2020; Tables 1 and 7).

Table 6.

Synthesised Findings – Process for categorisation and synthesis formation.

| Study | Study findings | Categories | Synthesises findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Crow (2020) | Lymphie conundrums: Grappling with normalising/Othering | Forced Normalcy | The ‘New Norm’ (This refers to the way in which those diagnosed with the condition are faced with a ‘new version’ of themselves, and how that is accommodated, and ‘normalised’ in their lives.) |

| Meiklejohn et al. (2013) | Accidental journey | ||

| Meiklejohn et al. (2013) | Altered normalcy | ||

| Nixon et al. (2018) | Adjustment to a new normal | ||

| Michael et al., 2016 | ‘An old man’s disease’: prostate cancer and the younger male | ||

| Michael et al., 2016 | ‘Only half a bloke’: changes to self-perception | ||

| Michael et al., 2016 | ‘It’s dictated my life’: disruption to function and its impact on daily life and life quality | ||

| Crow (2020) | Complexities, complications and confusion: Life difficulties along the journey | Psychological and Social Journey | The ‘New Norm’ (This refers to the way in which those diagnosed with the condition are faced with a ‘new version’ of themselves, and how that is accommodated, and ‘normalised’ in their lives.) |

| Crow (2020) | Striving to matter to and for others and self | ||

| Jeans et al. (2019) | It affects me in other ways | ||

| Meiklejohn et al. (2013) | Ebb and flow of control | ||

| Nixon et al. (2018) | Supports that helped manage distress | ||

| Nixon et al. (2018) | Day-to-day distress | ||

| Nixon et al. (2018) | Psychosocial impact | ||

| McGarvey (2014) | Psychosocial aspects of facial lymphoedema | ||

| Shakespeare (2012) | Psychological effects | ||

| Deng and Murphy (2016) | Suggestions on lymphoedema self-care | Management Process and Adoption | Journey into the ‘Unknown’ ( This pertains to the journey taken by those diagnosed with lymphoedema. It also considers that the journey started alongside another journey, which has led a ‘mystery tour’ that is less than wanted.) |

| Deng and Murphy (2016) | Perceived lymphoedema self-care education | ||

| Deng and Murphy (2016) | Reported lymphoedema self-care practices | ||

| Jeans et al. (2019) | It requires daily self-monitoring and management | ||

| Nixon et al. (2018) | Experience of receiving treatment | ||

| Shakespeare (2012) | Treatments | ||

| Shakespeare (2012) | Knowledge about lymphoedema | ||

| Shakespeare (2012)) | Provision of information about lymphoedema | ||

| Jeans et al. (2019) | It changes throughout the day | Physical Journey | Journey into the ‘Unknown’ ( This pertains to the journey taken by those diagnosed with lymphoedema. It also considers that the journey started alongside another journey, which has led a ‘mystery tour’ that is less than wanted.) |

| Jeans et al. (2019) | It feels tight | ||

| Nixon et al. (2018) | Physical experience and pattern/timing | ||

| McGarvey (2014) | Physical effects of lymphoedema | ||

| McGarvey (2014) | Diurnal pattern | ||

| McGarvey (2014) | Tightness and reduced cervical spine range of motion | ||

| McGarvey (2014) | Mucus secretions and swallowing | ||

| Shakespeare (2012) | Physical effects of lymphoedema on everyday life | ||

| Study | Study findings | Categories | Synthesises findings |

| Maree and Beckmann (2016) | ‘I am grateful’: Coping with the lymphoedema | Affordability and Access – The few or the many? (CB) | ‘Access, Access, Access’ (This pertains to the receiving of a diagnosis, information, and support. Set against the challenges in reaching this stage, and the benefits when it is achieved.) |

| Perera et al. (2007) | Expenditure | ||

| Perera et al. (2007) | Household economy ladder | ||

| Río-González et al., 2018 | Controlling expenses | ||

| Stolldorf et al. (2016) | Lacking resources patients | ||

| Towers et al., 2008 | Frustration | ||

| Maree and Beckmann (2016) | ‘Just live with it’: Lymphoedema the unknown and unspeakable | Information and Knowledge Generation – sufficient vs insufficient (CB) | ‘Access, Access, Access’ (This pertains to the receiving of a diagnosis, information, and support. Set against the challenges in reaching this stage, and the benefits when it is achieved.) |

| Río-González et al., 2018 | Searching information | ||

| Towers et al., 2008 | Lack of clarity about moving to the long-term phase of treatment | ||

| Towers et al., 2008 | Being alone | ||

| Towers et al. (2008) | Support systems | Support Networks – Knowing where to turn? (CB) | ‘Access, Access, Access’ (This pertains to the receiving of a diagnosis, information, and support. Set against the challenges in reaching this stage, and the benefits when it is achieved.) |

| Viehoff et al. (2016) | Environmental factors | ||

| Watts and Davies (2016) | ‘It has changed my life’: The impact of the local specialist led lymphoedema clinic | ||

| Perera et al. (2007) | Illness | Diagnosis – Lucky dip or serendipity (CB) | ‘Access, Access, Access' (This pertains to the receiving of a diagnosis, information, and support. Set against the challenges in reaching this stage, and the benefits when it is achieved.) |

| Watts and Davies (2016) | ‘Nothing was done until about a year ago’: Delays in correct diagnosis | ||

| Williams et al., 2004 | Experience of lymphoedema diagnosis | ||

| Frid et al. (2006) | Interaction with others | Sociability, Status and Power – what are the returns (CB) | ‘Personhood’ (This refers to the notion that a person exists as part of existential and relational constructs. How that is acknowledged by services and others is variable.) |

| Perera et al. (2007) | Impact ladder | ||

| Río-González et al., 2018 | Building relationships | ||

| Williams et al., 2004 | Experiences and dealing with lymphoedema | ||

| Hamilton and Thomas (2016) | Hope as action | ||

| Thomas and Hamiton (2014) | (In)visibility and appearance | ||

| Bogan et al. (2007) | Making room | Temporality – past, present, and future (CB) | ‘Personhood’ (This refers to the notion that a person exists as part of existential and relational constructs. How that is acknowledged by services and others is variable.) |

| Frid et al. (2006) | The future | ||

| Hamilton and Thomas (2016) | Renegotiating hope in the context of a chronic condition | ||

| Thomas and Hamiton (2014) | (In)visibility of the present and future | ||

| Tidhar (2018) | Hope | ||

| Tidhar (2018) | Maintenance versus back to normal (acceptance vs hope) | ||

| Bogan et al. (2007) | Turning point | ||

| Frid et al., 2006 | Dealing with problems | ||

| Hamilton and Thomas (2016) | The objects of hope | ||

| Stolldorf et al. (2016) | Impacting psychosocial well-being patients | ||

| Tidhar (2018) | Empowerment | ||

| Viehoff et al. (2016) | Personal factors | ||

| Bogan et al. (2007) | Nowhere to turn | Daily Life – Remembrance (CB) | ‘Personhood’ (This refers to the notion that a person exists as part of existential and relational constructs. How that is acknowledged by services and others is variable.) |

| Frid et al. (2006) | The physical aspects | ||

| Maree and Beckmann (2016) | ‘My arm is painful’: Living with the physical consequences of lymphoedema | ||

| Río-González et al., 2018 | Discovering physical and psychological barriers | ||

| Stolldorf et al. (2016) | Physical and functional impairments | ||

| Stolldorf et al. (2016) | Treatment and care | ||

| Thomas and Hamiton (2014) | (In)visibility and action | ||

| Towers et al., 2008 | Burden | ||

| Viehoff et al. (2016) | Body functions | ||

| Viehoff et al. (2016) | Body structures | ||

| Viehoff et al. (2016) | Activities and participation | ||

| Watts and Davies (2016) | ‘It’s a battle’: Living with lymphoedema | ||

| Williams et al. (2004) | Lymphoedema treatment |

Table 7.

Joanna Briggs Institute ConQual Score – Determination of the study’s credibility/dependability within the findings.

| Systematic review title | A systematic meta-aggregation literature review of the male experiences of chronic oedema/lymphoedema | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Population | Men over the age of 18 years | ||||

| Phenomena | Experience and perceptions of chronic oedema and lymphoedema | ||||

| Context | Men living with lymphoedema across the UK and globally | ||||

| Synthesised finding | Type of research | Dependability | Credibility | ConQual Score | Comments |

| The ‘New Norm’ (This refers to the way in which those diagnosed with the condition are faced with a ‘new version’ of themselves, and how that is accommodated, and ‘normalised’ in their lives.) | Qualitative | Unchanged | Downgraded 1 level | Moderate | Downgraded 1 levels due to moderate credibility |

| Journey into the ‘Unknown’ (This pertains to the journey taken by those diagnosed with lymphoedema. It also considers that the journey started alongside another journey, which has led a ‘mystery tour’ that is less than wanted.) | Qualitative | Unchanged | Downgraded 1 level | Moderate | Downgraded 1 levels due to moderate credibility |

| ‘Access, Access, Access’ (This pertains to the receiving of a diagnosis, information and support. Set against the challenges in reaching this stage, and the benefits when it is achieved.) | Qualitative | Unchanged | Downgraded 1 level | Moderate | Downgraded 1 levels due to moderate credibility |

| ‘Personhood’ (This refers to the notion that a person exists as part of existential and relational constructs. How that is acknowledged by services and others is variable.) | Qualitative | Unchanged | Downgraded 1 level | Moderate | Downgraded 1 levels due to moderate credibility |

Review finding results

Four synthesised findings were identified. The first two findings, (1) The ‘New Norm’ and (2) Journey into the ‘Unknown’, had a high representation of men and their accounts, which were constructed from eight studies, 32 findings and four categories. The remaining two findings, (3) Access and (4) Personhood, were constructed on 13 studies, 47 findings and seven categories. However, the sample of men and their accounts were smaller in representation or integrated into a single account:

Synthesised finding 1: The ‘New Norm’

The diagnosis of lymphoedema can have a negative impact upon men, with the need to meet other men like themselves

The baseline that men form of themselves which represent their perception of normal, alters when this is challenged by a new diagnosis especially one that is long-term. One man stated, ‘it’s dictated my life’, with another perceiving the condition as, ‘an old man’s disease’, reinforced by their contact with men, ‘You go to the support group…they are all elderly men, it felt old’ (Michael et al., 2016: 326, 325). The baseline of men was affected by their perceived vulnerability, between physical strength and its projection of manhood, ‘My legs ache,.., I don’t have the strength in my legs that I used to have.’, and its complications, ‘the most distressing part of…was cellulitis’ (Michael et al., 2016: 325; Nixon et al., 2018: 4). In the study by Crow (2020: 237) there was a perceived ‘feminisation’ of the condition by men, due to a perceived notion that body image was only a female concern, rather than being one that would affect both genders equally. This led to some men wishing to see, speak and interact with men like themselves, to lead to a ‘life calibration’, and to assist them to reconstruct their ‘new normal’ (Meiklejohn et al., 2013: 463; Nixon et al., 2018).

The psychological and social journey of men are not equal with the need for varied mechanisms to manage distress

It impacts upon the alterations to a man’s physical appearance, such as facial oedema, affected their expression of their masculinity, and led to social avoidance, such as recreational activities (McGarvey, 2014; Nixon et al., 2018). However, this was not homogenous, with some stating the effects of lymphoedema were ‘part and parcel of it’, which has been described as the ‘ebb and flow’ but can perpetuate notions of stoicism (McGarvey et al., 2014: 321; Meiklejohn et al., 2013: 463). This has also been noted as a potential transitional process similar to a grieving process with some men wishing to be ‘..re-diagnosed.’ (Meiklejohn et al., 2013: 463, Michael et al., 2016). Significant others were seen by men to play a key role within their lives, with this described as ‘supports that helped manage distress’ (Nixon et al., 2018: 21). Men also drew strength from their occupational identity, but this strength could lead men to prioritise work over their own health (Crow, 2020: 196–196; Nixon et al., 2018; Shakespeare, 2012).

Synthesised finding 2: ‘Journey into the unknown’

The physical manifestation of lymphoedema is the first challenge that men face but with limited knowledge and experience to manage it

This journey for some men occurred soon after treatment, such as cancer (Nixon et al., 2018). This led to experiences of physical discomfort and sensory changes, ‘. really tight around the bottom half of my chin’ and ‘It’s much firmer…’ (Jeans et al., 2019: 5). This rapid change did not allow time for preparation or even adaption for men, to the reduced range of movement, facial oedema, but also thick and viscous secretions, with one man stating, ‘It’s certainly affecting [me]’ (McGarvey, 2014: 320). The limited time led men to disengage from their recreational activities, due to limited knowledge and experience, of the ‘diurnal patterns’ within the presentation of their oedema (McGarvey, 2014: 320; Nixon et al., 2018). When this pattern was established, ‘..mainly there first thing in the morning…’, it led to men employing strategies to help them (Jeans et al., 2019: 5; McGarvey, 2014; Nixon et al., 2018; Shakespeare, 2012).

Self-management and the tools for educating men can be effective and empowering if tailored

The ability to undertake ‘self-monitoring’ and then implement strategies was seen as ‘empowering’ for men (Deng and Murphy, 2016; Jeans et al., 2019; Nixon et al., 2018). Expanding a man’s knowledge in this area can be received positively by men, but must equally be balanced against their specific condition, education and even their level of acceptance (Deng and Murphy, 2016; Nixon et al., 2018). This has led to words, such as being ‘fed up of it’, related to their perception of self-management and having, ‘no treatment at all, I just wear the elasticated stocking at work’, despite compression therapy representing the mainstay treatment option (Shakespeare, 2012: 136). Tailoring of education has been seen as requiring the understanding of the person’s learning style, access to peer support and even technological support in terms of self-care reminders to achieve empowerment (Deng and Murphy, 2016; Nixon et al., 2018: 20).

Synthesised finding 3: ‘Access, Access, Access’

Access to knowledgeable healthcare professionals and services can improve biopsychosocial outcomes for patients

The level of access to those with knowledge and expertise was filled with challenges from diagnosis to treatment (Perera et al., 2007). This has led to multiple referrals to receive a diagnosis, with some receiving this outcome via serendipitous events, thus increased levels of anxiety and risk of permanent physical changes (Perera et al., 2007; Watts and Davies (2016); Williams et al., 2004). Despite, reports of, ‘I went through several diagnoses’, this was compounded by the level of disinterest, but also observed lack of observed compassion, by being told, ‘just live with it’ (Maree and Beckmann, 2016: 82; Perera et al., 2007; Watts and Davies, 2016; Williams et al., 2004: 282).

Access to resources and support are affected by occupation and level of income

The type of support offered after a diagnosis was perceived as being affected by the level of household income examples (Perera et al., 2007; Río-González et al., 2018). This was linked to the ability to purchase aids for the donning or doffing of garments, or to buy shoes as a result of the oedema as examples (Perera et al., 2007; Río-González et al., 2018). In addition to the household income, the type of occupation and the tasks involved within it were seen to affect patient outcomes (Río-González et al., 2018). For example, low-income households engaged in more precarious work, that had a direct impact upon their condition, such as increased risk of trauma, or that an infection may lead to workplace disruption, such as sickness or absence (Río-González et al., 2018; Perera et al., 2007). This was associated with a level of ‘frustration’, due to the condition’s impact but also the perceived lack of financial support, such as from government to support as a result of their LTC (Stolldorf et al., 2016; Towers et al., 2008: 138).

Access to appropriate information can support a person to build their knowledge base surrounding lymphoedema

Limited access to appropriately tailored information led those affected to see information, but came across some that were not appropriate, such cancer-focused literature (Río-González et al., 2018). Shakespeare’s (2012) study connected with the notion that information needs to be understandable but also how it is related to its management (Tidhar, 2018; Towers et al., 2008). The absence of this being addressed led to feelings of loneliness, anger and disillusionment, ‘…haven’t had someone tell me, to give me a straight answer’. Whilst some suggest ‘the more I know, the more I will suffer’, acknowledges the individual concept of sufficient knowledge (Shakespeare, 2012: 139; Tidhar et al., 2018; Towers et al., 2008). Access to knowledge was also present when referring to effective support networks, such as significant others or peer support, who shared similar levels of knowledge and experiences to support their chosen strategies (Tower et al., 2004; Viehoff et al. (2016)).

Synthesised finding 4: ‘Personhood’

The diagnosis and development of lymphoedema was perceived as affecting the person’s past, present and future

The altered baseline of individuals was seen as a biopsychosocial shift, with the presence of grief alongside varying ‘turning points’ and the perception of ‘making room’ for what had occurred (Bogan et al., 2007: 219). However, within the studies this was not universal, with those that continued to ‘worry’, or were ‘waiting for a miracle to happen’, with the notion of ‘acceptance’ being a destination yet to be reached (Frid et al., 2006; Hamilton and Thomas (2016): 826; Towers et al., 2008: 41). In ‘dealing with problems’, such as the use of donning tools, patient education or support, the ability to accept led to choices focussing upon the future (Frid et al., 2006: 9). This represented ‘objects of hope’ (Hamilton and Thomas (2016): 826), but some were ‘not at that point yet’ (Bogan et al., 2007: 828; Stolldorf et al., 2016; Viehoff et al. (2016)).

Lymphoedema affects the person’s perception of power and status within their lives

‘Stigma’ was present within the study by Perera et al., (2007: 6), but also the reduced ‘social standing’ caused by the visibility and reaction to their lymphoedema. Williams et al. (2004) study commented on how the reactions and actions of those around them caused them distress. Thomas and Hamiton (2014) referred to the problem of having a condition that was ‘highly visible, while they live with a largely invisible or unknown condition’, due to the limited social awareness (Río-González et al., 2018; Thomas and Hamiton (2014): 4). The change in status and perception, altered existing relationships, such as caring duties, with others needing to be rebuilt even within themselves (Frid et al. (2006)). Especially when it affected their occupational identity, ‘The senior nurse took me off the ward and I was office based. I decided then I had had enough, and I just retired. I feel really grieved’ (Watts and Davies, 2016: 3151). This led to seeking of havens with those who held knowledge and experience to support them and to avoid feelings of loneliness (Thomas and Hamiton (2014), Williams et al., 2004).

The presence of lymphoedema acts as a constant reminder within a person’s daily life

The oedematous limb acted as a symbol, and a reminder of the changes that had occurred, but also led to a level of ‘discomfort’, beyond its physical appearance (Frid et al. (2006)). This affected the person’s constructed baseline (Viehoff et al. (2016)), in which there was a focus upon controlling the impact of the condition through strategies, until this was challenged by external forces. ‘..in the summer when it is hot, you get the feeling that your leg is swelling and you can’t move forward’ (Viehoff et al. (2016): 415). This loss of control acted as a reminder of what had come to pass, with refuge sought through hiding the condition even from themselves, ‘In winter it is a little better, I can hide it, but in summer it is very bad an emotional thing’ (Maree and Beckmann, 2016: 81). The relationship between the conditions and its presence in their daily lives was one that is contentious, and hard to resolve.

Discussion

The qualitative review provides one of the first collective insights of the daily lives of men diagnosed with lymphoedema. This resonates with the work by Monyihan et al. (2017) regarding men diagnosed with a LTC and the complexity that is added to a person’s life when faced with another LTC diagnosis. This is relevant when other international studies suggest that lymphoedema often co-exists with another LTC condition (Cosgriff, 2010; Moffatt et al., 2019b). Moniyan et al. (2017: 1988) goes on to suggest a LTC can cause a level of ‘Ambiguity in a masculine world’, in which vulnerability and weakness are associated with ill health by men and society (Moynihan et al., 2017: 1988). This feeds into the work by Leventhal et al. (2016) regarding a person’s existing prototype of themselves (baseline) and how this develops into their ‘illness representation’. This has been suggested as affecting masculinity and associated traits, such as older men and ‘stoicism’, but may also play a beneficial part in developing ‘optimism’ and even ‘self-determination’ (Moynihan et al., 2017: 1989). Masculinity is considered to have varying typology and expression, with some suggesting there are dominant versions (hegemonic) (Coles et al., 2012).

The changes to what is a perceived ‘norm’ and their masculinity is a challenging area for men, with them seeking a sense of control and empowerment to manage the LTC (Leventhal et al., 2016; Reigel et al., 2019; Zanchetta et al., 2017). This reflects other work regarding the need for appropriate access to information that is accurate and tailored (Deng and Murphy, 2016; Nixon et al., 2018). This not only takes into account how it is delivered, but also by whom, such as knowledgeable healthcare professionals, and the ability to interact with men similar to themselves (Flurey et al., 2018; Williams et al., 2004). This has the potential to change a man’s prototype of themselves (baseline), but also the strategies for the management of their condition, thus altering their ‘illness representation’ (Leventhal et al. 2016). However, this requires men to allow a level of vulnerability in seeking support, linked to their internal beliefs surrounding men and ill health (Dale et al., 2015; Robertson and Baker, 2017). This may be magnified, due to the suggested inequity of service provision to those affected by lymphoedema in the UK (Moffatt et al., 2019a).

Multiple referral and delays in the receipt of a diagnosis and treatment is a documented issue, leading to complications (Dale et al., 2015; Perera et al., 2007; Stolldorf et al., 2016). For example, persistent infections and sickness, leading to men to place ‘occupational demands’ ahead of their own health (Dale et al., 2015: 9). This was to project ‘strength’ within a workplace that considers ill health as unacceptable (Jønsson et al., 2020: 109; Zanchetta et al., 2017). This is alongside the deployment of ’push back’ as a tactic, to distance themselves from the condition, but to also create a sense of normality in their lives (Dale et al., 2015: 10). This reflects the notion of personhood in which there is ‘a moral and ethical category, tied to the concepts of autonomy, agency and self-determination’ (Sofronas et al., 2018: 407). This is caused by their perceived loss, but also the uncertainty of their role in future (Gentili et al., 2019; Persson et al., 2019). Gender-based delivery of services has been suggested as a means to remedy some of the aspects mentioned, whilst acknowledging men are one homogenous group (Robertson and Baker, 2017). Despite this approach being advocated, at the present time it has yet to be fully developed or delivered (Lönnberg et al., 2020; Robertson and Baker, 2017).

Strengths and limitations

The qualitative review is one of the first to identify, appraise and undertake a meta-aggregation in this area. This extended to the systematic review and process that was undertaken across the available databases. However, the study also has limitations by not including non-English studies caused by no access to translation services. Equally, there are several studies that did not present a clear separation between male and female accounts, thus making it challenging to ensure they fully represented men and their narratives.

Conclusion

Lymphoedema impacts widely across men within the studies retrieved. Studies with a higher representation, or had a clearer account of men, led to two synthesised themes, (1) ‘forced normalcy’ and (2) ‘journey into the unknown’, that identify the challenges men face in both accepting and managing their lymphoedema condition. Whilst still offering insight, the disruption faced by men was less apparent within the two remaining themes, due to the combination of men and women into one account, still offered insight. It equally took a different tone and focus, with the concept of having ‘access’, coupled with overall impact upon ‘personhood’. Appropriate knowledge information and access to expertise negated some of the biopsychosocial complications of lymphoedema. However, this was connected to their ‘personhood’, and the value they derive for themselves and from the wider society. The surrounding literature resonated with the findings of the review, and the way men engage within their health set against their perception of masculinity. This places a greater demand on services to consider intersectionality within the healthcare economy and requires further empirical research to be undertaken within men and lymphoedema.

Key points for policy, practice and/or research

• The involvement of men within the design and commissioning of lymphoedema services to ensure that their needs are understood and met is crucial.

• Men with lymphoedema require access to a wide range of sources of support, therefore policymakers should collaborate with these men, especially those with non-cancer related causes, and with representative organisations public, private and charitable.

• Policymakers should recognise the importance of gender appropriate information resources and how these can be developed within existing services.

• Policymakers should take into consideration that lymphoedema will exist alongside other Long Term Conditions.

Biography

Garry R Cooper-Stanton - Doctoral Researcher/Lecturer, University of Birmingham, Lymphoedema Clinical Nurse Specialist, Queen’s Nurse. Alongside, clinical experience across public, private, and charitable sectors Gary undertakes research in primary care, long-term conditions and lymphoedema.

Nicola Gale - Professor, University of Birmingham, Health Sociologist within single-discipline sociological research and interdisciplinary health research in the fields of health services research, public health, primary care, community-led and complementary health care.

Manbinder Sidhu - Research Fellow, University of Birmingham, working within the Health Services Management Centre (HSMC) as part of the BRACE Rapid Evaluation Centre. Focusing upon patient experiences and service evaluation of interventions.

Kerry Allen - Senior Lecturer, University of Birmingham, within the Health Services Management Centre. Focusing upon medical sociology and applied research to improve health and care services, with complex needs or long-term conditions.

Footnotes

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethical approval: This was a systematic review and thus exempt from ethics approval.

ORCID iD

Garry R Cooper-Stanton https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8758-8665

References

- Bettany-Saltikov J. (2016) How to Do a Systematic Literature Review in Nursing: A Step-by-step Guide. Second Edition. London: Open University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bogan L, Powell J, Dugeon B. (2007) Experiences of living with non-cancer-related lymphedema: implications for clinical practice. Qualitative Health Research 17: 213–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borbassi S, Hawes C, Addicoat R, et al. (2004) Getting it together: Men's and their carers' experience of lymphoedema. Cancer Nurses Society of Australia 5(2): 25–33. [Google Scholar]

- Booth A, Carroll C, Ilott I, et al. (2013) Desperately seeking dissonance: identifying the disconfirming case in qualitative evidence synthesis. Qualitative Health Research 23(1): 126–141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coles R, Watkins F, Swami V. (2012) History and the challenge of gender history. Men and Masculinities 15(1): 103–113. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper G, Bagnall A. (2016) Prevalence of lymphoedema in the UK: focus on the southwest and West Midlands. British Journal of Community Nursing Supplement 21(40): S6–S14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cosgiff N. (2010) Cancer-related lymphoedema in males: a literature review. Journal of Lymphoedema 5(2): 49–61. [Google Scholar]

- Crow E. (2020) Illuminating the Experience of Growing up and Living with Primary Lymphedema: A Life History Study. USA: PhD Thesis: Oklahoma State University. [Google Scholar]

- Dale C, Angus E, NielsenKramer-Kile SM, et al. (2015) “I’m no superman”: understanding diabetic men, masculinity, and cardiac rehabilitation. Qualitative Health Research 25(12): 1648–1661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng J, Murphy BA. (2016) Lymphedema self-care in patients with head and neck cancer: a qualitative study. Supportive Care in Cancer 24(12): 4961–4970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flurey C, White A, Rodham K, et al. (2018) ‘Everyone assumes a man to be quite strong’: men, masculinity and rheumatoid arthritis: a case-study approach. Sociology of Health & Illness 40(1): 115–129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frid M, Strang P, Friedrichsen MJ, et al. (2006) Lower limb lymphedema: experiences and perceptions of cancer patients in the late palliative stage. Journal of Palliative Care 22: 5–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gentili C, McClean S, Hackshaw-McGeagh L, et al. (2019) Body image issues and attitudes towards exercise amongst men undergoing androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) following diagnosis of prostate cancer. Psycho-oncology 28(8): 1647–1653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton R, Thomas R. (2016) Renegotiating hope while living with lymphoedema after cancer: a qualitative study. European Journal of Cancer Care 25(50): 822–831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- International Lymphoedema Framework (2006) Best Practice for the Management of Lymphoedema. London: ILF. [Google Scholar]