Abstract

In order to identify antigenic proteins of Mycoplasma gallisepticum, monoclonal antibodies (MAbs) against virulent M. gallisepticum R strain were produced in mice. MAb 35A6 was selected for its abilities to inhibit both growth and metabolism of M. gallisepticum in vitro. The MAb recognized a membrane protein with an apparent molecular mass of 120 kDa. The corresponding gene, designated the mgc3 gene, was cloned from an M. gallisepticum genomic DNA expression library and sequenced. The mgc3 gene is a homologue of the ORF6 gene encoding 130-kDa protein in the P1 operon of M. pneumoniae and is localized downstream of the mgc1 gene, a homologue of the P1 gene. To assess the characteristics of MGC3 protein, all 10 TGA codons in the mgc3 gene, which encode a tryptophan in the Mycoplasma species, were replaced with TGG codons, and recombinant fowlpox viruses (FPV) harboring the altered mgc3 gene were constructed. One of the recombinant FPVs was improved to express MGC3 protein on the cell surface in which the signal peptide of MGC3 protein was replaced with one from Marek's disease virus gB. These results should provide the impetus to develop a vaccine based on MGC3 protein which can induce antibodies with both growth inhibition and metabolic-inhibition activities using a recombinant FPV.

Mycoplasma gallisepticum is the aetiologic agent of chronic respiratory disease in chickens and infectious sinusitis in turkeys (37). The disease is characterized by nasal discharge, respiratory rales, coughing, and airsacculitis. M. gallisepticum infection causes reduced feed conversion and egg production, and the outbreaks remain a persistent cause of severe economic loss for broiler and turkey production firms (36). The best solution for controlling this disease may reside in the development of safe and effective vaccines.

An attenuated strain, the F strain, can induce protective immune responses and subsequently improve egg production in vaccinated chickens. However, the F strain is not completely apathogenic for young chickens (25) and turkeys (20), and it may spread to M. gallisepticum-free chicken and turkey farms. Other attenuated strains, ts11 (40) and 6/85 (7) have been used as vaccines in multi-age layers because of lower virulence. These strains, however, confer somewhat less protection than does the F strain (1). On the other hand, for an inactivated vaccine, an experimental immunostimulating complex (ISCOM) vaccine consisting of detergent-solubilized M. gallisepticum antigens and Quillaja saponin induced protective immunity and significantly reduced lesion scores in the air sac after challenge (31). The success of the inactivated vaccine using the special adjuvant suggests that the isolation of specific immunogens responsible for protective immunity may lead to the development of effective vaccines without the adverse side effects associated with the administration of whole organisms.

We have focused on the identification and structural analysis of M. gallisepticum surface antigens which are prominent targets of the chicken immune responses and may influence key host interactions (27). The attachment of M. gallisepticum to mucosal epithelium of the respiratory tract of birds is thought to be prerequisite for infection and disease (19). Therefore, a vaccine designed to induce inhibition responses to the attachment and the growth of M. gallisepticum in vivo should provide protective immunity to the organism.

The present study describes the production of a mouse monoclonal antibody (MAb) that inhibits both growth and metabolism of M. gallisepticum in vitro and the identification of an antigen recognized by the MAb. The antigen, designated MGC3, was a 120-kDa membrane protein and a homologue of 130-kDa protein encoded by the ORF6 gene, which is a part of P1 operon of M. pneumoniae (30). Recently, the 40- and 90-kDa proteins from 130-kDa protein have been shown to be responsible for the tip structure formation associated with P1 (17). Since we demonstrate for the first time that MGC3 protein possesses epitopes recognized by MAbs with growth inhibition and metabolic-inhibition activities, few attempts have so far been made to use the 130-kDa protein or its homologues as vaccine candidates. It is of interest to express the mgc3 gene and to determine whether MGC3 protein is important as a potential target of humoral responses in chickens. For these purposes, we used a recombinant fowlpox virus (FPV) expression system which has been established as a live viral vector for use of vaccines against avian viruses such as Newcastle disease virus (13, 24) and Marek's disease virus (MDV) (23, 35, 38) in our laboratory. Based on the recombinant FPV technology, MGC3 protein expressed by recombinant FPVs was analyzed in chicken fibroblast embryo (CEF) cells.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains and growth conditions.

The sources of M. gallisepticum strains R, F, S6, and KP13 have been described elsewhere (10, 16). These M. gallisepticum strains were grown statically at 37°C for 3 days in Chanock's modified medium (5). M. gallisepticum strains were filter cloned according to the recommendations of the Subcommittee on the Taxonomy of Mollicutes (14, 33) and subsequently freeze-dried. CEF cells were maintained in Leibovitz-McCoy medium (Life Technologies, Inc., Rockville, Md.) supplemented with 4% calf serum and antibotics. A large plaque variant of cell culture-attenuated FPV (22) was used as the parental virus from which recombinants were constructed.

Production of MAbs.

Six-week-old BALB/c mice were immunized subcutaneously with 100 μg of whole M. gallisepticum R strain protein emulsified in Freund's complete adjuvant. Three weeks later, the mice were injected intraperitoneally with the same antigen concentration in Freund's incomplete adjuvant. Three days later, serum was collected, and spleen cells were fused with P3X63Ag8.U1 myeloma cells (American Type Culture Collection, Rockville, Md.), using an established procedure (4). Hybridoma clones were screened by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) using the whole M. gallisepticum R strain (3). ELISA-positive hybridoma clones were used for preparation of M. gallisepticum-specific antibody-producing tumors in pristane (2,6,10,14-tetramethylpentadecane)-primed BALB/c mice. Ascites fluids containing MAbs were clarified by centrifugation at 2,000 × g for 10 min and stored at −20°C. The immunoglobulin concentration of each ascites fluid was measured with a IgG Mouse ELISA Quantitation Kit (Bethyl Laboratories, Inc.). The immunoglobulin class and subclass were typed with the MonoAB-ID EIK kit A (Zymed).

SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting.

Whole-cell preparations of M. gallisepticum strains used in this study were separately suspended at a protein concentration of 1 mg/ml in sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 6.8], 2% SDS, 10% glycerol, 2% β-mercaptoethanol, 0.1% bromophenol blue), heated in a boiling water bath for 3 min, and stored at −20°C until used. Mycoplasma proteins were separated by SDS–8% PAGE, and the gel was either stained with Coomassie brilliant blue or electrophoretically transferred to Immobilon Transfer Membrane (Millipore, Bedford, Mass.) for immunoblotting. The membrane was treated with MAb 35A6 followed by alkaline phosphatase-conjugated goat anti-mouse immunoglobulin G (IgG; Promega, Madison, Wis.). Polypeptide bands recognized by the MAb were visualized by using nitroblue tetrazolium chloride plus 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyphosphate p-toluidine salt.

Growth inhibition assay.

The growth inhibition assay without complement was performed essentially as described previously (27). In brief, M. gallisepticum R strain was grown in Chanock's modified medium at 37°C for 3 days, filtered through a 0.45-μm (pore-size) membrane filter, and diluted to 1.2 × 103 CFU/ml. Three hundred CFU of the suspension cells were cultured in the presence of 50 μg of MAbs or serum dilutions of 1:10 in a volume of 300 μl. The cultures were incubated at 37°C for 3 days. To determine the number of CFU, six serial 10-fold dilutions in modified Chanock's medium were performed in duplicate. Aliquots of 10 or 100 μl were plated on modified Chanock's agar medium following gentle passing of the cultures through a 0.45-μm filter. After 6 to 7 days of incubation at 37°C, the number of CFU was counted under a stereomicroscope (Leitz).

Metabolic inhibition assay.

The complement-independent inhibition of glucose metabolism by MAbs resulting in the reduction of an acidity shift in the medium pH was analyzed in microtiter plates as described previously (32). Twenty-five microliters of MAbs (5 mg/ml) or sera was serially diluted in a microtiter plate. Color-changing units (CCU), representing the number of mycoplasmas, were determined by serial dilution with tubes containing phenol red. One CCU of M. gallisepticum R strain in 150 μl of culture medium containing phenol red was added to each well. When cells proliferated, the medium turned yellow because of the presence of phenol red in the medium. After 3 days of incubation at 37°C, the color of the culture medium was checked. When the medium remained red at the maximum dilution of antibodies, the concentration was determined as the metabolism inhibition titer.

Flow cytometoric analysis.

For analysis of the expression of a 120-kDa protein on the cell surface, 105 M. gallisepticum cells were incubated either with MAb 35A6 or control MAb 1AN86 (29) for 45 min on ice. After a washing, the cells were incubated with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG (Pharmingen, San Diego, Calif.) for 45 min on ice. After a second washing, the cells were analyzed by FACScan (Becton Dickinson, San Jose, Calif.).

Preparation of polyclonal antisera.

For the preparation of chicken polyclonal anti-M. gallisepticum R strain serum, 5-week-old specific-pathogen-free chickens (line M; Institute of Nippon Biological Science, Tokyo, Japan) were immunized subcutaneously in the right thigh with 100 μg of M. gallisepticum R strain whole cells emulsified in Freund's complete adjuvant. Two subsequent boosters of the same antigen concentration in Freund's incomplete adjuvant were administered at 2-week intervals. Sera were collected 2 weeks after the final booster and used to immunoscreen an M. gallisepticum genomic DNA expression library.

For the preparation of mouse polyclonal anti-120-kDa-protein serum, lysates of M. gallisepticum R strain was prepared with lysis buffer (25 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.5], 150 mM NaCl, 0.1% SDS, 1% Triton X-100, 1% sodium deoxycholate). The 120-kDa protein was purified from the lysate by coupling MAb 35A6 to protein A-Sepharose CL-4B (Pharmacia). Female BALB/c mice aged 6 to 8 weeks were immunized subcutaneously with 20 μg of the 120-kDa protein emulsified in Freund's complete adjuvant. Two subsequent boosters of the same antigen concentration in Freund's incomplete adjuvant were administered at monthly intervals. Sera were collected 2 weeks after final booster.

Construction and screening of an M. gallisepticum genomic DNA expression library.

M. gallisepticum genomic DNA was extracted as described previously (15). The genomic DNA of M. gallisepticum R strain was partially digested with AluI and size-selected (1 to 3 kb) DNA fragments were ligated to λgt11 arm DNA (Stratagene GmbH, Heidelberg, Germany) and packaged using Gigapack gold packaging extract (Stratagene) according to the manufacturer's instructions, resulting in a primary genomic library with a size of 106 PFU. The library was immunoscreened with chicken polyclonal anti-M. gallisepticum R strain serum. Positive clones were pooled and reimmunoscreened with the mouse polyclonal anti-120-kDa-protein serum.

DNA cloning and sequencing.

A λgt11 phage DNA was extracted from a plaque that reacted with the mouse polyclonal anti-120-kDa-protein serum. An insert DNA fragment was amplified from the phage DNA by PCR. To obtain a full-length gene encoding 120-kDa protein, the PCR products were radiolabeled with [α-32P]dCTP and used as a probe for Southern blot analysis (28). DNA fragments identified by Southern blot analysis were cloned into pUC18 by a standard procedure (2). DNA sequencing was performed on double-stranded plasmid by the Dye Terminator Cycle Sequencing FS Ready Reaction Kit (Applied Biosystems, Inc., Foster City, Calif.). DNA sequence data was analyzed with the GENETYX-MAC software package, as well as the GenBank and Swissprot databases, for comparison of the 120-kDa protein predicted amino acid sequence with database entries.

Replacement of TGA codons with TGG codons.

To express the mgc3 gene by recombinant FPVs, all 10 TGA codons in the mgc3 gene were replaced with TGG codons using the PCR with a total of 15 primers. The sequence of each primer contains restriction enzyme recognition sites which are created without amino acid substitution. The PCRs were performed as described above except for the use of M11-1, M11-2, and M11-3 clones as templates (see Fig. 2). The PCR products were digested with appropriate restriction enzymes and then inserted into pUC18 to construct the altered mgc3 gene, designated pUC-MGC3.

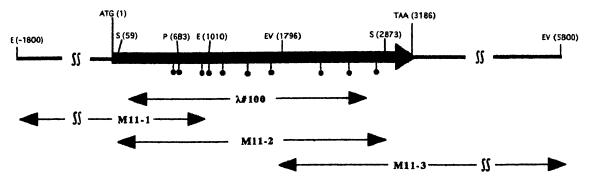

FIG. 2.

Restriction map and ORF of the mgc3 gene. Plasmid subclones of this region (M11-1, -2, and -3) were obtained by colony hybridization with the λ#100 fragment as a probe. These plasmids were used not only as templates for DNA sequence but also as templates for PCR to construct recombinant transfer vectors, pNZ29RMGC3 and pNZ29RMGC3-S, as described in Materials and Methods. The ORF of the mgc3 gene is shown by a box, with an arrow showing the direction of transcription. The 10 TGA codons in the ORF are indicated by closed circles. The entire region of the M11-2 clone and a portion of the M11-1 and M11-3 regions were sequenced in both strands to determine the ORF of the mgc3 gene. E, EcoRI; EV, EcoRV; P, PstI; S, SacI.

Generation of recombinant FPVs.

Transfer vector pNZ29RMGC3 was constructed by inserting a 3,228-bp BamHI-SphI fragment from pUC-MGC3 into the BamHI-SphI site of insertion vector pNZ1829R (24). Transfer vector pNZ29RMGC3-S was constructed by replacing the 5′ terminus encoding the MGC3 predicted signal sequence with the 5′ terminus encoding the MDV glycoprotein B (gB) signal sequence. The 5′-terminal fragment encoding MDV gB signal sequence was obtained from plasmid pNZ29RMDgB (35) by PCR using primers pgB-1 (5′-CCCCAGGATCCAATCATGCACTATTTTAGG-3′; a BamHI site is underlined) and pgB-2 (5′-CCCCCAGAGCTCCTCGAGATGTCACATTTTGGGTACTCGGAGA-3′; a newly created SacI site is underlined). This set of primers had a restriction site flanked by five additional bases to protect the site and facilitate enzyme digestion. Transfer vector pNZ29RMGC3-S was constructed by replacing a 67-bp BamHI-SacI fragment from pNZ29RMGC3 with a 105-bp BamHI-SacI fragment of the PCR products. The procedure for transfection of FPV-infected cells with the transfer vectors by electroporation and generation of recombinant FPVs was described previously (24, 35). The resulting FPVs were designated recFPV-MGC3 and recFPV-MGC3-S.

Expression of the mgc3 gene by recombinant FPVs. (i) Immunoprecipitation.

CEF cells were infected with recombinant FPVs at a multiplicity of infection of 5 PFU/cell. Cell labeling with [35S]methionine and immunoprecipitation with MAb 35A6 were performed as described previously (38).

(ii) Endo H treatment.

Immunoprecipitated proteins were digested with endoglycosidase H (Endo H; Boehringer-Mannheim) and PNGase F (Boehringer-Mannheim) as described previously (38).

(iii) Immunofluorescence.

Indirect immunofluorescence was performed on monolayers of CEF cells grown on eight-chambered tissue culture slides (Miles Scientific, Division of Miles Laboratories, Inc., Naperville, Ill.) infected with recombinant FPVs. At 16 h postinfection, cells were fixed with 100% methanol at −20°C for 10 min or with 3% paraformaldehyde in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) for 15 min and then blocked with 4% bovine serum albumin in PBS. The slides were incubated with MAb 35A6 for 1 h at room temperature. Bound MAb was detected with FITC-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG (Life Technologies, Inc.) by fluorescence microscopy.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The nucleotide sequence of the mgc3 gene has been deposited with GenBank under accession number AB023292.

RESULTS

Production of MAbs capable of inhibiting growth and metabolism.

Hybridoma supernatants derived from mice immunized with whole M. gallisepticum R strain were screened by ELISA. Hybridoma cells secreting high levels of antibodies to M. gallisepticum R strain were selected to produce ascites fluids. The growth inhibition and metabolic-inhibition activities against M. gallisepticum R strain by the representative MAbs are shown in Table 1. MAbs 30G8, 35A6, and 34H1 had very strong growth inhibition activities. The percentages of cell growth in the presence of these MAbs compared with control MAb 1AN86 are even less than 0%, indicating that these MAbs inhibit cell multiplication completely for 3 days after incubation. The highest metabolic inhibition was obtained in the presence of MAb 35A6. On the other hand, MAbs 30G8 and 34H1 that strongly inhibited M. gallisepticum growth were less effective in inhibiting metabolism of the organism than MAb 35A6. As a positive control, the mouse polyclonal anti-M. gallisepticum R strain serum displayed a modest level of both growth inhibition and metabolic-inhibition activities, whereas normal mouse serum or a control MAb, 1AN86, did not have growth inhibition and metabolic-inhibition activities. MAb 35A6 is a IgG2a isotype, and it recognizes the multiple bands with molecular sizes (Mr) of 105 to 120 kDa from a M. gallisepticum lysate (Fig. 1). The prominent band in the complexity of the binding pattern is a 120-kDa protein. Thus, we found MAb 35A6 to be a valuable tool for the identification of immunogenic antigens of M. gallisepticum.

TABLE 1.

Effects of MAbs and polyclonal antibodies on M. gallisepticum growth and metabolism

| Antibody added | Growth inhibitiona

|

Metabolic inhibitionc | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Growth (CFU/ml) | Growth (%)b | ||

| MAbs | |||

| 1AN86 | 2.5 × 107 | 100 | 1/4 |

| 30G8 | 9.8 × 102 | −8.8 × 10−6 | 1/400 |

| 35A6 | 8.5 × 102 | −1.4 × 10−7 | 1/102,400 |

| 34H1 | 3.0 × 102 | −3.6 × 10−7 | 1/1,600 |

| Sera | |||

| Normal mouse serum | 8.7 × 107 | 348 | 1 |

| Mouse anti-M. gallisepticum serum | 7.3 × 102 | −8.8 × 10−6 | 1/258 |

| Mouse anti-120-kDa (MGC3) serum | 4.6 × 103 | 1.4 × 10−2 | 1/126 |

| Normal chicken serum | 1.6 × 108 | 640 | 1 |

| Chicken anti-M. gallisepticum serum | 1.5 × 103 | 1.2 × 10−5 | 1/2,048 |

Samples of 250 μl of M. gallisepticum R strain (1.2 × 103 CFU/ml) were cultured in the presence of 50 μg of MAbs per 50 μl or serum dilutions of 1:10 per 30 μl. Following 96 h of incubation at 37°C, aliquots of serial diluted culture medium were plated on modified Chanok's agar medium. After 6 to 7 days of incubation at 37°C, the number of CFU was counted under a stereomicroscope.

% Growth = [(A − O)/(C − O)] × 100, where A is CFU at 96 h of culture incubated in tested antibodies, C is CFU at 96 h of culture incubated in control MAb 1AN86, and O is initial starting CFU at 0 h.

Twenty-five microliters of MAbs (5 μg/μl) or sera was serially diluted in microtiter plate. M. gallisepticum R strain (1 CCU/well) in 150 μl of culture medium containing phenol red were added to each well. After 3 days of incubation at 37°C, metabolism inhibition titers were determined by a color shift of the medium.

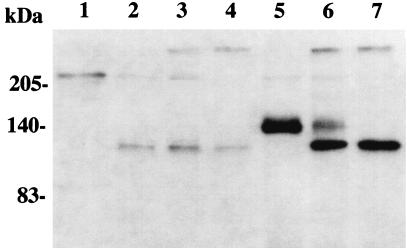

FIG. 1.

Immunoblot analysis of M. gallisepticum with MAb 35A6. A lysate of M. gallisepticum R strain was separated by SDS–8% PAGE, and the gel was either stained with Coomassie brilliant blue (lane 1) or electrophoretically transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane for immunoblotting (lane 2). The membrane was then treated with MAb 35A6, followed by alkaline phosphatase-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG. Numbers to the left of the gel show the sizes of molecular mass markers.

Cloning of a gene encoding 120-kDa protein.

In an attempt to identify a gene encoding a 120-kDa protein, a λgt11 genomic DNA library of M. gallisepticum was constructed. In an earlier study, no positive clone was obtained by immunoscreening with MAb 35A6 from the library. Since the most outstanding feature in the codon usage of mycoplasma species is that the TGA stop codon is utilized for tryptophan (34), a gene encoding an epitope recognized by the MAb would never be obtained from the Escherichia coli expression system, such as a λgt11 library, if the epitope is located on or following TGA codons unless an opal suppressor mutant is used (21). We therefore made a mouse polyclonal anti-120-kDa-protein serum because the polyclonal antiserum was considered to be more reliable. As expected, the polyclonal antiserum had both growth inhibition and metabolic-inhibition activities (Table 1). By immunoscreening with chicken polyclonal anti-M. gallisepticum R strain serum, which had both growth inhibition and metabolic-inhibition activities (Table 1), 100 positive clones were obtained from the library. Of these clones, a single positive clone (λ#100), which contained an insertion of 2.8 kb, was obtained by reimmunoscreening with the mouse polyclonal anti-120-kDa-protein serum. In fact, the λ#100 clone did not react with MAb 35A6.

To obtain a full-length gene encoding the 120-kDa protein, Southern hybridization was performed using the insertion DNA fragment, amplified by PCR, as a probe. Three overlapping fragments (2.8-kb EcoRI, 2.8-kb SacI, and 3.8-kb EcoRV) were cloned into pUC18 and designated M11-1, -2, and 3, respectively (Fig. 2). These fragments were partially sequenced to determine an open reading frame (ORF) encoding 120-kDa protein.

Analysis of deduced amino acid sequence.

The nucleotide sequence of a 4-kbp fragment containing the λ#100 insert DNA has an ORF which comprises 3,186 bp, and the predicted primary translation products would be a protein of 1,062 amino acids with a predicted size of 115.8 kDa. The gene has 10 TGA codons encoding tryptophan. Hydropathic analysis indicates that the protein contains characteristic features of membrane proteins, namely, a 5′ hydrophobic signal sequence at the N-terminal end between positions 1 and 22, an external hydrophilic surface domain, a hydrophobic membrane-spanning domain, and a basic, highly charged cytoplasmic domain (data not shown). The predicted size of the gene product following a signal sequence cleavage (113.5 kDa) is in good agreement with the 120-kDa protein as estimated by SDS-PAGE.

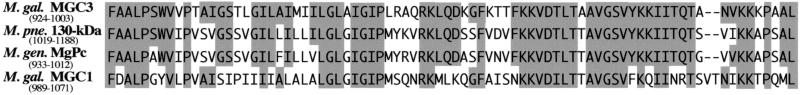

A comparison of the predicted amino acid sequence of the gene to other mycoplasma counterparts revealed that the C-terminal region extending from amino acid residues 927 to 1,003 shares significant homologies with the M. pneumoniae 130-kDa protein, which is encoded by the ORF6 gene (12) (70% identity), and the M. genitalium 114-kDa protein, which is encoded by the ORF3 gene (9) (75% identity) (Fig. 3). Interestingly, the region also has a striking homology with the C terminus of MGC1 (15), which is a homologue of M. pneumoniae P1. We found a partial sequence encoding the C terminus of MGC1 upstream of the ORF, which is consistent with the gene arrangement that the ORF6 gene is located downstream of the P1 gene. Since Keeler et al. (15) and Hnatow et al. (11) have identified that the M. gallisepticum mgc1 and mgc2 genes are homologous to the ORF4 and P1 genes, respectively, we have named the gene encoding 120-kDa protein the mgc3 gene based on their genetic nomenclature. In addition, the absence of cysteine residues in the MGC3 protein sequence is also consistent with the M. pneumoniae 130-kDa and M. genitalium 114-kDa proteins.

FIG. 3.

Alignment of the amino acid sequences from a highly conserved region of MGC3, M. pneumoniae 130-kDa protein (12), M. genitalium 114-kDa protein (9), and MGC1 (15) with the GAP alignment program from the Sequence Analysis Software Package of the Genetics Computer Group (6). The position of the first and last depicted amino acid are shown. Amino acid residues conserved with MGC3 are shaded.

Cell surface localization of MGC3 protein in M. gallisepticum.

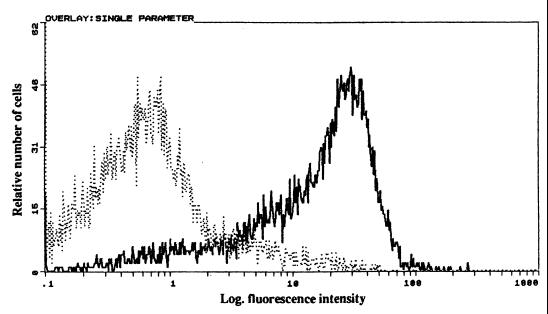

On the basis of the predicted amino acid sequence of the mgc3 gene, MGC3 protein was expected to be located on the cell surface as a membrane protein. To address this, the freshly harvested organisms were treated with MAb 35A6 and analyzed for cell surface expression by flow cytometry. Strong immunofluorescent staining was detected when MAb 35A6 was used (Fig. 4). This observation is consistent with the previous report that the ORF6 gene product was a membrane-associated protein expressing a surface-exposed region (18).

FIG. 4.

Cell surface analysis of M. gallisepticum with MAb 35A6 by flow cytometry. M. gallisepticum R strain was freshly harvested and incubated either with MAb 35A6 (thick line) or 1AN86 (dotted line) as a control MAb. Surface expression was analyzed by FACScan (Becton Dickinson, San Jose, Calif.) following treatment with FITC-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG.

Reactivities of MAb 35A6 for different strains.

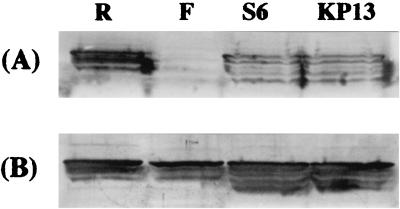

MGC3 protein was affinity-purified with MAb 35A6 and inoculated into mice to produce a polyclonal antiserum to this protein. These sera were found to have high antibody titers against M. gallisepticum and also inhibited the growth and metabolism of M. gallisepticum in vitro (Table 1). To examine the reactivity of MAb 35A6 with other strains, Western blotting analysis was performed on M. gallisepticum strains R, S6, F, and KP13. M. gallisepticum R, S6, and KP13 possessed the 120-kDa protein as recognized by MAb 35A6, whereas M. gallisepticum F strain, an avirulent vaccine strain, was not recognized (Fig. 5A). In the case of M. pneumoniae, mutant missing 130-kDa protein is avirulent (8). In view of the relationship between the lack of MGC3 protein and avirulence, it was of interest to examine whether M. gallisepticum F strain possesses MGC3 protein. For this purpose, the mouse polyclonal anti-MGC3 protein serum was used to detect MGC3 protein by Western blotting. The 120-kDa proteins were detected in all strains tested, including the F strain (Fig. 5B), indicating that the F strain possesses MGC3 protein without the epitope for MAb 35A6.

FIG. 5.

Immunoblot analysis of MGC3 protein from M. gallisepticum strains. Whole M. gallisepticum R, F, S6, and KP13 were subjected to SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted either with MAb 35A6 (A) or with mouse polyclonal anti-MGC3 protein serum (B). The same amount protein was applied to all lanes as determined by Coomassie brilliant blue-staining of SDS-gels.

Expression of the mgc3 gene by using recombinant FPVs in CEF cells.

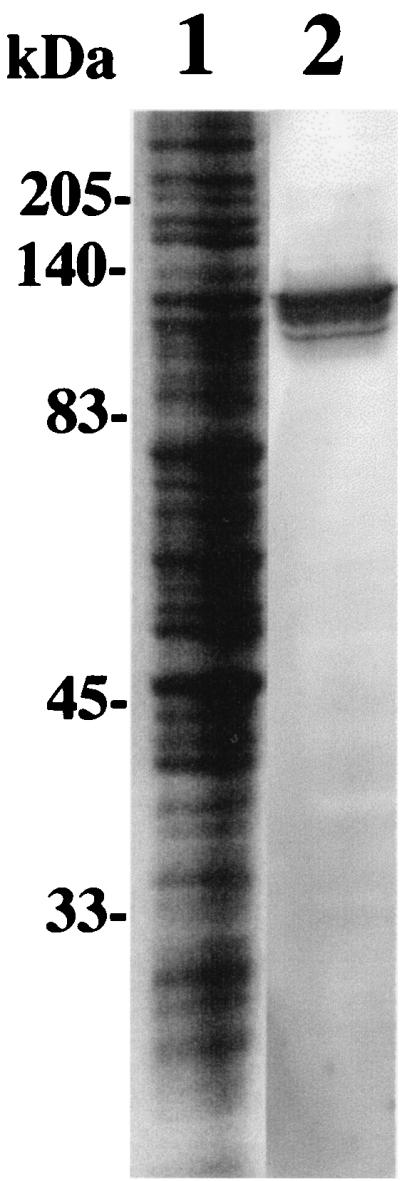

Whereas the antigen can be affinity purified using MAb 35A6 from M. gallisepticum R strain lysate, only a limited amount of the antigen was obtained by this method. Therefore, an alternative strategy, which we have chosen, was the use of recombinant DNA techniques to determine the gene for the protective immunogen and to generate a recombinant FPV for analysis of the expression. All 10 TGA codons in the mgc3 gene were replaced with TGG codons by PCR using 15 primers. A recombinant FPV, recFPV-MGC3 encodes the full-length mgc3 gene under the control of a strong synthetic pox promoter (35). Another recombinant FPV, recFPV-MGC3-S, encodes the mgc3 gene fused to the MDV gB signal sequence in the place of its native signal sequence. The mgc3 gene products were synthesized in CEF cells infected with the recombinant FPVs and were characterized by immunoprecipitation with MAb 35A6 (Fig. 6). A 120-kDa protein was found in CEF cells infected with recFPV-MGC3 (lane 2), which migrated to the same position as native MGC3 protein of M. gallisepticum. In contrast, an approximately 50-fold-higher level of expression of a protein of 145 kDa was seen in CEF cells infected with recFPV-MGC3-S (lane 5). Both 120- and 145-kDa proteins were also recognized by MAb 34H1 with growth inhibition activity (data not shown). No specific band was observed in the parent FPV-infected CEF cells (lane 1). These results clearly demonstrated that the mgc3 gene product possesses growth inhibition and metabolic-inhibiting epitopes recognized by MAbs 35A6 and 34H1.

FIG. 6.

Expression and glycosylation of MGC3 protein by recombinant FPVs. CEF cells infected with parent FPV (lane 1), recFPV-MGC3 (lanes 2 to 4), or recFPV-MGC3-S (lanes 5 to 7) were radiolabeled, lysed, and immunoprecipitated with MAb 35A6. Immunoprecipitated proteins were mock digested (lanes 1, 2, and 5), treated with Endo H (lanes 3 and 6), or treated with PNGase F (lanes 4 and 7). Immunoprecipitates were subjected to SDS–8% PAGE. The gel was fluorographed, dried, and exposed at −70°C. Numbers to the left of the gel show the sizes of molecular mass markers.

N-linked carbohydrate modification of MGC3 in recFPV-infected cells.

To address the size differences between MGC3 proteins expressed by recFPV-MGC3 and recFPV-MGC-S, these immunoprecipitated proteins were treated with endoglycosidases. In recFPV-MGC3-infected cells, no mobility shifts was observed in MGC3 protein either after Endo H or PNGase F treatment (Fig. 6, lanes 3 and 4), whereas a mobility shift was observed at from 145- to 120 kDa after Endo H and PNGase F treatments in recFPV-MGC3-S-infected cells (Fig. 6, lanes 6 and 7). This result demonstrated that the size differences were due to the posttranslational modifications, and the 145-kDa protein expressed by recFPV-MGC3-S was the simple high-mannose type. There are 15 potential N-linked glycosylation sites in MGC3 protein. The altered mobility shift indicated that 10 to 13 glycosylation sites of MGC3 protein are N linked with high-mannose carbohydrates, assuming an increase in size of 1,000 to 2,000 Da per glycosylation. Thus, using FPV expression system, the protective epitopes on MGC3 protein recognized by the MAbs capable of inhibiting both growth and metabolism were unaffected by N-linked glycosylation.

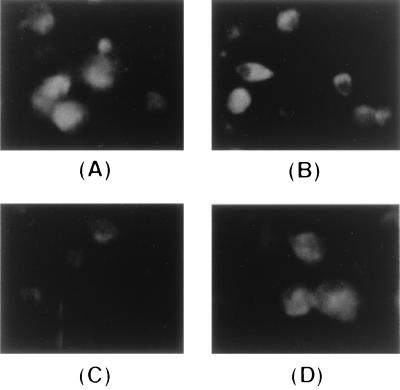

Cell surface localization of MGC3 in recombinant FPV-infected cells.

Expression of MGC3 protein on the cell surface might also play an important role in humoral immunity because this protein elicits growth-inhibiting antibodies. To assess whether MGC3 protein expressed by recombinant FPV is transported to the cell surface, an immunofluorescent analysis was performed with MAb 35A6. Strong cell surface immunofluorescence was observed on the recFPV-MGC3-S-infected cells, whereas only a faint signal was detected on the recFPV-MGC3-infected cells (Fig. 7). This result showed that MGC3 protein was transported to the cell surface by replacing with the MDV gB signal peptide.

FIG. 7.

Immunofluorescent analysis of cell surface localization of MGC3 protein expressed by recombinant FPVs. CEF cells infected with recFPV-MGC3 (A and C) or recFPV-MGC3-S (B and D) were fixed either with cold methanol to detect protein in the cell (A and B) or 3% paraformaldehyde to detect protein on the cell (C and D). Fixed cells were treated with MAb 35A6 followed by treatment with FITC-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG.

DISCUSSION

This study describes the identification of a gene encoding an epitope recognized by MAb 35A6 which is capable of inhibiting both the growth and metabolism of M. gallisepticum in vitro. The gene, designated the mgc3 gene, is a homologue of the ORF6 gene in the P1 operon of M. pneumoniae and is located downstream of the mgc1 gene. The two genes of the P1 operon of M. gallisepticum have been identified as the mgc1 and mgc2 genes homologous to the P1 and ORF4 genes, respectively (15, 11). MGC3 protein encoded by the mgc3 gene may function as a cytoadherence-associated molecule because the M. pneumoniae 130-kDa protein has been implicated in the cellular adhesion process (8).

A striking homology at the amino acid level was found in the C terminus among 130-kDa protein homologues, where the regions might function as a membrane spanning and anchoring. This result implies that there is a similarity in membrane structure among the mycoplasmas. On the other hand, the sequence diversity at N-terminal region might reflect differences in mycoplasma receptor proteins found on the surfaces of human and avian epithelial cells. We found a couple of differences with regard to gene expression and organization between M. gallisepticum and M. pneumoniae. The 130-kDa protein is co- or posttranslationally cleaved to 40- and 90-kDa proteins and is located on the cell surface as a membrane-associated protein (18). In addition, the ORF6 gene carries repetitive DNA sequences (RepMP5) which are dispersed as multiple copies on the chromosome, suggesting that gene conversion between the multiple-copy regions results in antigen variation (26). In contrast to the ORF6 gene, the mgc3 gene exists as a single chromosomal copy, and the gene product does not seem to be cleaved.

We have developed a recombinant FPV expression system to examine its potential to protect against avian diseases. For example, immunization with a recombinant FPV expressing the MDV gB gene elicited neutralizing antibodies in chickens, resulting in protection against a lethal MDV challenge (23). In addition, gB antigen expressed by the recombinant FPV was located on the cell surface (39). We therefore used not only this recombinant FPV expression system but also the gB signal sequence for cell surface expression. To assess the characteristics of MGC3 protein in its host cells, all of the TGA codons in the mgc3 gene, which encode a tryptophan in Mycoplasma species, were replaced with TGG codons. Additionally, recombinant FPVs harboring the altered mgc3 gene were constructed. Replacement of the natural signal sequence of MGC3 protein with the MDV gB signal sequence improved not only the transportation of MGC3 protein with a growth inhibiting and metabolic-inhibiting epitope to the cell surface but also the expression level of MGC3 protein. Although MGC3 protein expressed by recFPV-MGC3-S underwent N-linked glycosylation and would not be the native form in M. gallisepticum, the protective epitopes recognized by MAbs 35A6 and 34H1 were successfully expressed on the surface of its host cells. It is likely that surface-exposed epitopes which induce a neutralizing immune response should increase its immunogenicity. In addition, the MDV gB signal peptide could provide a good model system to express a gene derived from bacteria such as mycoplasma on the eukaryotic cell surface.

Our findings provide the first demonstration that MGC3 protein contains epitopes which can induce antibodies responsible for growth inhibition and metabolic-inhibition activities and is expressed on the cell surface in the recombinant FPV expression system. It is possible that the induction of antibodies to the epitopes recognized by the MAbs in chickens can result in protective immune responses against M. gallisepticum challenge. We are in the process of investigating recombinant FPV-based vaccines for the protection of chickens against M. gallisepticum infection.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank A. Yasuda for DNA sequencing and B. Cowen for critical review of the manuscript. We especially thank K. Kamogawa and N. Yanagida for encouragement and support of this study.

ADDENDUM

The 5′-terminal regions of the mgc3 genes of M. gallisepticum F, S6, and KP13 strains were cloned by PCR and partially sequenced from the ATG start codon to nucleotide position 1,130 downstream of the start codon. An alignment of the mgc3 genes of the four strains revealed that the DNA sequences of M. gallisepticum R and KP13 were identical and that the DNA sequence homologies between strains R and S6 and between strains R and F are 93.1 and 89.7%, respectively. The partial nucleotide sequences of the mgc3 genes of M. gallisepticum F and S6 strains will appear in the DDBJ/EMBL/GenBank nucleotide sequence databases with the accession numbers AB033210 and AB033211, respectively.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abd-El-Motelib T Y, Kleven S H. A comparative study of Mycoplasma gallisepticum vaccines in young chickens. Avian Dis. 1993;37:981–987. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ausubel F A, Brent R, Kingston R E, Moore D, Seidman J G, Smith J A, Struhl K, editors. Current protocols in molecular biology. New York, N.Y: Greene Publishing Associates and Wiley-Interscience; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Avakian A P, Ley D H. Protective immune response to Mycoplasma gallisepticum demonstrated in respiratory-tract washings from M. gallisepticum-infected chickens. Avian Dis. 1993;37:697–705. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carter P B, Beegle K H, Gebhard D H. Monoclonal antibodies: clinical uses and potential. Vet Med Small Anim Clin. 1986;16:1171–1179. doi: 10.1016/s0195-5616(86)50135-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chanock R M, Hayflick L, Barile M D. Growth on artificial medium of an agent associated with atypical pneumonia and its identification as a PPLO. Proc Acad Natl Sci USA. 1962;48:41. doi: 10.1073/pnas.48.1.41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Devereux J, Haeberli P, Smithies O. A comprehensive set of sequence analysis programs for the VAX. Nucleic Acids Res. 1984;12:387–395. doi: 10.1093/nar/12.1part1.387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Evans R D, Hafez Y S. Evaluation of a Mycoplasma gallisepticum strain exhibiting reduced virulence for prevention and control of poultry mycoplasmosis. Avian Dis. 1992;36:197–201. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Franzoso G, Hu P C, Meloni G A, Barile M F. The immunodominant 90-kilodalton protein is localized on the terminal tip structure of Mycoplasma pneumoniae. Infect Immun. 1993;61:1523–1530. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.4.1523-1530.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fraser C M, Gocayne J D, White O, Adams M D, Clayton R A, Fleischmann R D, Bult C J, Kerlavage A R, Sutton G, Kelley J M, Fritchman J L, Weidman J F, Small K V, Sandusky M, Fuhrmann J, Nguyen D, Utterback T R, Saudek D M, Phillips C A, Merrick M, Tomb J, Dougherty B A, Bott K F, Hu P, Lucier T S, Peterson S N, Smith H O, Hutchison III C A, Venter J C. The minimal gene complement of Mycoplasma genitalium. Science. 1995;270:397–403. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5235.397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Garcia M, Kleven S H. Expression of Mycoplasma gallisepticum F-strain surface epitope. Avian Dis. 1994;38:494–500. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hnatow L L, Keeler C L, Jr, Tessmer L L, Czymmek K, Dohms J E. Characterization of MGC2, a Mycoplasma gallisepticum cytadhesin with homology to the Mycoplasma pneumoniae 30-kilodalton protein P30 and Mycoplasma genitalium P32. Infect Immun. 1998;66:3436–3442. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.7.3436-3442.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Inamine J M, Loechel S, Hu P C. Analysis of the nucleotide sequence of the P1 operon of Mycoplasma pneumoniae. Gene. 1988;73:175–183. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(88)90323-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Iritani Y, Aoyama S, Takigami S, Hayashi Y, Ogawa R, Yanagida N, Saeki S, Kamogawa K. Antibody response to Newcastle disease virus (NDV) of recombinant fowlpox virus (FPV) expressing a hemagglutinin-neuraminidase of NDV into chickens in the presence of antibody to NDV or FPV. Avian Dis. 1991;35:659–661. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.International Committee on Systematic Bacteriology and Subcommittee on the Taxonomy of Mollicutes. Proposal for minimal standards for description of new species of the class Mollicutes. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1979;29:172–180. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Keeler C L, Jr, Hnatow L L, Whetzel P L, Dohms J E. Cloning and characterization of a putative cytadhesin gene (mgc1) from Mycoplasma gallisepticum. Infect Immun. 1996;64:1541–1547. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.5.1541-1547.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Khan M I, Lam K M, Yamamoto R. Mycoplasma gallisepticum strain variations detected by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. Avian Dis. 1987;31:315–320. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Layh-Schmitt G, Harkenthal M. The 40- and 90-kDa membrane proteins (ORF6 gene product) of Mycoplasma pneumoniae are responsible for the tip structure formation and P1 (adhesin) association with the Triton shell. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1999;174:143–149. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1999.tb13561.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Layh-Schmitt G, Herrmann R. Localization and biochemical characterization of the ORF6 gene product of the Mycoplasma pneumoniae P1 operon. Infect Immun. 1992;60:2906–2913. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.7.2906-2913.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Levisohn S. Early stages in the interaction between Mycoplasma gallisepticum and the chick trachea, as related to pathogenicity and immunogenicity. Isr J Med Sci. 1984;20:982–984. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lin M Y, Kleven S H. Pathogenicity of two strains of Mycoplasma gallisepticum in turkeys. Avian Dis. 1982;26:360–364. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Minion F C, Van Dyk C, Smiley B K. Use of an enhanced Escherichia coli opal suppressor strain to screen a Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae library. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1995;131:81–85. doi: 10.1016/0378-1097(95)00239-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nazerian K, Dhawale S, Payne W S. Structural proteins of two different plaque-size phenotypes of fowlpox virus. Avian Dis. 1989;33:458–465. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nazerian K, Lee L F, Yanagida N, Ogawa R. Protection against Marek's disease by a fowlpox virus recombinant expressing the glycoprotein B of Marek's disease virus. J Virol. 1992;66:1409–1413. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.3.1409-1413.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ogawa R, Yanagida N, Saeki S, Saito S, Ohkawa S, Gotoh H, Kodama K, Kamogawa K, Sawaguchi K, Iritani Y. Recombinant fowlpox viruses inducing protective immunity against Newcastle disease and fowlpox viruses. Vaccine. 1990;8:486–490. doi: 10.1016/0264-410x(90)90251-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rodriguez R, Kleven S H. Pathogenicity of two strains of Mycoplasma gallisepticum in broilers. Avian Dis. 1980;24:800–807. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ruland K, Himmelreich R, Herrmann R. Sequence divergence in the ORF6 gene of Mycoplasma pneumonia. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:5202–5209. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.17.5202-5209.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Saito S, Fujisawa A, Ohkawa S, Nishimura N, Abe T, Kodama K, Kamogawa K, Aoyama S, Iritani Y, Hayashi Y. Cloning and DNA sequence of a 29 kilodalton polypeptide gene of Mycoplasma gallisepticum as a possible protective antigen. Vaccine. 1993;11:1061–1066. doi: 10.1016/0264-410x(93)90134-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Silva R F, Lee L F. Monoclonal antibody-mediated immunoprecipitation of proteins from cells infected with Marek's disease virus or turkey herpesvirus. Virology. 1984;136:307–320. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(84)90167-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sperker B, Hu P, Herrmann R. Identification of gene products of the P1 operon of Mycoplasma pneumoniae. Mol Microbiol. 1991;5:299–306. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1991.tb02110.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sundquist B G, Czifra G, Stipkovits L. Protective immunity induced in chicken by a single immunization with Mycoplasma gallisepticum immunostimulating complexes (ISCOMS) Vaccine. 1996;14:892–897. doi: 10.1016/0264-410x(95)00262-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Taylor-Robinson D, Berry D M. The measurement of antibody to Mycoplasma gallisepticum by the metabolic-inhibition technique. J Gen Microbiol. 1969;56:3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tully J G. Cloning and filtration techniques for mycoplasmas. In: Razin S, Tully J G, editors. Methods in mycoplasmology. I. New York, N.Y: Academic Press; 1983. pp. 173–177. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yamao F, Muto A, Kawauchi Y, Iwami M, Iwagami S, Azumi Y, Osawa S. UGA is read as tryptophan in Mycoplasma capricolum. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1985;82:2306–2309. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.8.2306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yanagida N, Ogawa R, Li Y, Lee L F, Nazerian K. Recombinant fowlpox viruses expressing the glycoprotein B homolog and the pp38 gene of Marek's disease virus. J Virol. 1992;66:1402–1408. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.3.1402-1408.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yoder H W., Jr . Mycoplasma gallisepticum infection. In: Calnek B W, Barnes H J, Beard C W, Reid W M, Yoder H W Jr, editors. Diseases of poultry. 9th ed. Ames, Iowa: Iowa State University Press; 1991. pp. 198–212. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yoder H W, Jr, Hopkins S R, Mitchell B W. Evaluation of inactivated Mycoplasma gallisepticum oil-emulsion bacterins for protection against airsacculitis in broilers. Avian Dis. 1984;28:224–234. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yoshida S, Lee L R, Yanagida N, Nazerian K. The glycoprotein B genes of Marek's disease virus serotypes 2 and 3: identification and expression by recombinant fowlpox viruses. Virology. 1994;200:484–493. doi: 10.1006/viro.1994.1211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yoshida S, Lee L F, Yanagida N, Nazerian K. Mutational analysis of the proteolytic cleavage site of glycoprotein B (gB) of Marek's disease virus. Gene. 1994;150:303–306. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(94)90442-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Whithear K, Soeripto G, Harrigan K E, Ghiocas E. Immunogenicity of a temperature-sensitive mutant Mycoplasma gallisepticum vaccine. Aust Vet J. 1990;67:159–165. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-0813.1990.tb07748.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]