Graphical abstract

Keywords: Novel Coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19), Sentiment, Chinese stock market, Official News Media, Sina Weibo

Abstract

This study quantitatively measures the Chinese stock market’s reaction to sentiments regarding the Novel Coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19). Using 6.3 million items of textual data extracted from the official news media and Sina Weibo blogsite, we develop two COVID-19 sentiment indices that capture the moods related to COVID-19. Our sentiment indices are real-time and forward-looking indices in the stock market. We discover that stock returns and turnover rates were positively predicted by the COVID-19 sentiments during the period from December 17, 2019 to March 13, 2020. Consistent with this prediction, margin trading and short selling activities intensified proactively with growth sentiment. Overall, these results illustrate how the effects of the pandemic crisis were amplified by the sentiments.

1. Introduction

The Novel Coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19) represents an unprecedented threat to human health and the prosperity of the world. This outbreak is a shock to both financial markets and investors. In the World Economic Forum’s Global Risk Report (2020), the topic of “infectious diseases” was ranked number 10 in terms of impact. On March 11, the World Health Organization (WHO) officially characterized COVID-19 as a pandemic. As of March 16, there were 80,881 confirmed cases in China, with 68,679 patients having been cured. Similar to the COVID-19, researchers find that the SARS in 2002 produces tremendous effects on the economy (e.g., Siu and Wong, 2004; Chen et al., 2007). Therefore, it is important to analyze the impact of this pandemic from the economic perspective.

Literature documents that information may affect corporate behaviors (e.g., Grullon et al., 2002; Hirshleifer and Teoh, 2003; Hirshleifer and Shumway, 2003; Bushee et al., 2010). Chan (2003) finds that investors react to news in the stock market, especially for the bad news. Kaplanski and Levy (2010) analyzes whether sentiments may affect stock returns. Fang and Peress (2009) examines the relationship between media coverage and stock returns, supporting the hypothesis that information dissemination may affect stock returns. This strand of literature indicates that media reports may affect investors’ behavior, and by observing market sentiments, it is possible to predict stock market volatility to some extent. But it should be noted that the information dissemination methods is changing with the development of information technology. Therefore, how the media reports will affect the financial market in this new era is still a question.

Recently, many pioneering studies regarding stock price reactions to the COVID-19 have emerged in the literature (Ashraf, 2020, Baker et al., 2020, Ramelli and Wagner, 2020). In terms of the relatively complete containment of COVID-19 in China, this study examines stock price reactions to sentiments about COVID-19 as reflected in both the official news media and Sina Weibo. The first issue we address is the following: Does the level of news media or blogging activities about COVID-19 successfully predict subsequent stock returns and turnover rates? COVID-19 is raging globally, causing loss of lives. To combat this, over 100 countries implemented several types of lockdown by the end of March 2020, while governments ramped up testing and treatment to contain the spread of the virus. Social distancing and lockdown measures forced many people to stay home, allowing them to devote considerable time and effort to creating and reading messages posted on Internet media and Sina Weibo.

All of this attention to the Internet caused us to wonder whether these texts actually affect stock prices. There are three specific issues that we consider. Is there disagreement among the official news media or Sina Weibo messages associated with COVID-19? Does the number of optimistic or pessimistic texts posted help predict future returns or turnover rates? Does a rapid change in sentiment affect future returns? There are many previous empirical studies analyzing the relationship between sentiment and stock market activity (Dellavigna and Pollet, 2009, Fang et al., 2009), but this is the first study examining how sentiments over COVID-19 affect stock markets.

We discover that there is evidence of positive predictability, even after controlling for gold prices and time effects. When optimistic news media or blog coverage is posted on a given day, there are statistically significant positive returns in the next day. These returns are often very large. Moreover, the trading behavior of investors is also critical. Barber and Odean (2000) find that individuals investors who are high trading levels have the poor performance. Barder and Odean (2009) analyze the relationship between the trading of individual investors and the market. Margin trading and short selling become increasingly important determinants to stock prices in the Chinese A-share market, which is worth exploring in terms of market reaction. We find that positive sentiment is followed by intensified margin trading and short selling volume.

There are several discussions on the epidemic and related topics on official online media platforms and Sina microblogs, featuring headlines such as “the ‘angels in white’ fighting an uphill battle, come on” and “Despair! Coronavirus outbreak hits Diamond Princess cruise ship.” Concerns regarding the COVID-19 sentiment may help us understand the rapid movements in firms’ stock prices, which do not seem to correspond to changes in quantitative measures of firm fundamentals (e.g., Shiller, 1981; Tetlock et al., 2008). Does the COVID-19 sentiment have a relationship with traditional sentiment (Baker et al., 2012, Baker and Wurgler, 2006, 2007)? This study also develops a Baker and Wurgler (BW) sentiment index using Chinese financial data and tests correlations and predictions.

The public and official news media convey optimistic or pessimistic sentiment about COVID-19 vis-a-vis the Internet. The pandemic affects activities in the real economy. Moreover, its effects are amplified by official media sentiment. Based on our long-term accumulation of a multi-source textual big data set, comprising approximately 1.8 million pieces of official news and 4.5 million Sina Weibo microblogs, we construct two COVID-19 sentiment indices that capture related emotions. Edmans et al. (2007) investigated stock market reactions to sudden changes in investor mood and argued that a mood variable must satisfy three key characteristics to rationalize studying its association with stock returns. First, the constructed variable must drive mood in a substantial and unambiguous way, so that its effect is sufficiently powerful to appear in asset prices. Second, the variable must impact the mood of a large proportion of the population, so that it is likely to affect enough investors. Third, the effect must be correlated across the majority of individuals within a country. These COVID-19 sentiment indices were developed using content from official Chinese news media and Sina Weibo. As of 2019, the number of Internet users have approached 1 billion in scale. Meanwhile, Sina Weibo features 465 million active users. Therefore, the epidemic-related sentiment variables based on the innovative construction of multi-source media satisfy the three characteristics required to conduct an examination of China’s stock market.

The second issue pertains to assessing the COVID-19 news and messages. Our method differs from the growing body of financial research that uses textual analysis to examine the tone and sentiment of newspaper articles by referring to a “dictionary” (e.g., Antweiler and Frank, 2004; Tetlock, 2007, 2010; Tetlock et al., 2008). A commonly used source for word classifications is the Harvard Psycho-Sociological Dictionary and the LM Dictionary (Loughran and McDonald, 2011). However, Chinese characters can have many meanings and hence, a translated English word categorization scheme derived for one discipline might not effectively translate into another discipline with its own dialect. We, therefore, read 10,000 news and 10,000 blogs carefully. The attitude reflected in the news or blogsite is determined by manual reading. All texts are then divided into three sets using specific tags (optimistic (+1), neutral (0), and pessimistic (−1)). The oldest algorithm used to classify textual data is called Naive Bayes. Another two algorithms, known as Support Vector Machine (SVM) and XGboost, have become very popular for assessing classification problems, including text classification. To ensure robustness, all tests are performed using the three above mentioned algorithms for the 20,000 training dataset. Finally, SVM was selected to process the entire dataset because of its superior performance.

The third issue is how to develop sentiment indices using the classified text. Like Antweiler and Frank (2004), we count the amount of news or blogs in different emotion sets after classifying the texts using SVM algorithms.

Finally, both our official news media and Sina Weibo COVID-19 sentiment indices may predict stock market activities. First, epidemic sentiment has a significant predictive effect on stock returns and stock trading activities. Second, when the mood about the pandemic changed from panic and fear to optimism, the changes are positively associated with Chinese stock returns. Both intensified margin trading and increased short-selling volume follow the positive sentiment. In addition, the turnover rates increase as the sentiment increase, but short selling stock is more constrained.

This study contributes to the existing literature in three ways. One is in terms of the data and methodology used. We collect 6.3 million texts from the official news media and Sina blogs and trained the attitude of full articles and blog content with manual interpretation and SVM algorithms. Further, our sentiment indices are constructed to reflect the public’s mood in response to the COVID-19 pandemic based on two large-scale public platforms in China. The period from December 17, 2019 to March 13, 2020 covers incubation, outbreak, fever, and well-controlled. Our analysis of Chinese stock prices considers reactions to official news and private discussions. In addition, our sentiments positively predict returns for margin trading and short selling activities. Moreover, we measure traditional investors’ sentiment using the Chinese daily market-based series constructed by Baker and Wurgler (2006, 2007) and Baker et al., (2012). Their composite sentiment index captures six factors, including the value-weighted average closing price on closed-end mutual funds, turnover, annual number and first-day returns of initial public offerings (IPOs), gross annual equity share divided by total issuance, and year-end market-to-book ratios. We discover that the traditional sentiment measure is not as stable or statistically significant or as predictive as our COVID-19 sentiment indices.

The remainder of the paper proceeds as follows. Section 2 describes the dataset and COVID-19 sentiment indices. Section 3 outlines the empirical methodology. Section 4 investigates how the stock market responds to the COVID-19 and BW sentiments and examines margin trading and short selling activities in response to sentiment. Section 5 concludes the paper and offers thoughts on the pandemic sentiment.

2. Data and sample

2.1. COVID-19 sentiment

This section describes how sentiments change with the keywords discussed on COVID-19. Table 1 , Panel A presents the top 60 official news media websites. Fig. 1 presents screenshots of the official news media and Sina Weibo content in our MySQL database. Based on the long-term accumulation of multi-sourced textual big data, 20 million text items are collected and stored from between December 17, 2019 to March 13, 2020. We delete duplicate universal resource locators and remove the stop Chinese words to clean up the dataset. Finally, 1,815,179 pieces of news and 4,519,293 microblogs from Sina Weibo are obtained to sum up 6,334,472 texts related to COVID-19. Clustering methods show that topics regarding public discussion of the pandemic continued changing over time. Applying dynamic word frequency analysis, the first 56 high-frequency vocabulary words are finally selected as text screening standards to clean the news media and Sina blog content (Table 1, Panel B).

Table 1.

Top 60 official news media websites, COVID-19 sentiment keywords, and algorithms.

|

Panel A: Top 60 media websites | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rank | Media website | N | Rank | Media website | N |

| 1 | Sohu.com | 126821 | 31 | mirachaber | 8405 |

| 2 | Sina.com.cn | 115927 | 32 | CnWest | 8320 |

| 3 | NetEase | 59942 | 33 | Rednet.cn | 8143 |

| 4 | People.cn | 57210 | 34 | Leju.com | 7843 |

| 5 | ZAKER | 48434 | 35 | China.com | 7267 |

| 6 | Workercn.cn | 30493 | 36 | Scol.com.cn | 7178 |

| 7 | QQ.com | 30253 | 37 | Gog.cn | 7089 |

| 8 | Ifeng.com | 29848 | 38 | Anhuinews.com | 6565 |

| 9 | Chinanews.com | 28702 | 39 | Hnr.cn | 6537 |

| 10 | Nxzwnews.net | 28591 | 40 | Cnr.cn | 6411 |

| 11 | Offcn | 26528 | 41 | Gxnews.com.cn | 6329 |

| 12 | 360doc.com | 21383 | 42 | Cri.cn | 6314 |

| 13 | Wenming.cn | 21328 | 43 | Iweihai.cn | 6310 |

| 14 | 10jqka.com.cn | 20492 | 44 | Ce.cn | 6236 |

| 15 | Xinhuanet.com | 19412 | 45 | Newssc.org | 6204 |

| 16 | ThePaper.cn | 19212 | 46 | Sdnews.com.cn | 6147 |

| 17 | Dzwww.com | 18348 | 47 | Weixu.net | 5985 |

| 18 | China.com.cn | 15846 | 48 | Jiemian.com | 5896 |

| 19 | Jxnews.com.cn | 15354 | 49 | Haiwainet.cn | 5728 |

| 20 | Mnw.cn | 15291 | 50 | Iqilu.com | 5642 |

| 21 | JRJ.com | 12621 | 51 | Cngold.org | 5204 |

| 22 | Hexun.com | 12562 | 52 | Huatu.com | 5181 |

| 23 | EastMoney.com | 12120 | 53 | Lhsjhy | 5106 |

| 24 | Qianlong.com | 10711 | 54 | Huanqiu.com | 5048 |

| 25 | SinaMobile | 10483 | 55 | Zjol.com.cn | 5039 |

| 26 | Enorth.com | 9932 | 56 | Southcn.com | 4984 |

| 27 | Beijing news | 9394 | 57 | Voc.com.cn | 4969 |

| 28 | Fjsen.com | 9008 | 58 | Cspa | 4943 |

| 29 | Southmoney.com | 8910 | 59 | Shukong.net | 4928 |

| 30 | Twoeggz.com | 8737 | 60 | Yingshan.cooo.cn | 4925 |

|

Panel B: COVID-19 sentiment keywords | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rank | Keyword | Frequency | Rank | Keyword | Frequency |

| 1 | Infection | 417587 | 29 | human-to-human | 92914 |

| 2 | Bushmeat | 354027 | 30 | Huang gang | 92886 |

| 3 | Prevention and control | 345617 | 31 | Goggles | 67961 |

| 4 | Facemask | 334603 | 32 | Vulcan mountain | 58492 |

| 5 | Pandemic | 296164 | 33 | Hospital | 57965 |

| 6 | Confirmed case | 286308 | 34 | Clove doctor | 54059 |

| 7 | A new type of pneumonia | 285677 | 35 | Kam Tin Hospital | 46686 |

| 8 | Suspected | 283937 | 36 | Li Lanjuan | 41172 |

| 9 | 3M | 277426 | 37 | The thor mountain | 38595 |

| 10 | Fight disease | 251470 | 38 | Travel control | 35675 |

| 11 | Wuhan | 247817 | 39 | Extension of school | 34813 |

| 12 | novel coronavirus | 245263 | 40 | Public health emergency | 27430 |

| 13 | Wei Jian Wei | 215366 | 41 | The virus nucleic acid | 21241 |

| 14 | COVID-19 | 192912 | 42 | Gao Fu | 21058 |

| 15 | SARS | 154644 | 43 | Xiao tang shan | 20916 |

| 16 | Disease control | 149938 | 44 | Seafood Market | 19816 |

| 17 | affected area | 145563 | 45 | Shuang Huang Lian | 17967 |

| 18 | Lockdown | 140640 | 46 | Stay at home | 17614 |

| 19 | heroes in harm’s way | 136255 | 47 | KN95 | 17421 |

| 20 | Zhong Nanshan | 134559 | 48 | Red Cross Society | 16750 |

| 21 | Health Crisis | 127271 | 49 | Union Hospital | 14381 |

| 22 | The WHO | 125181 | 50 | Shanghai Institute of Medicine | 12616 |

| 23 | Protective suit | 121870 | 51 | Emergency supplies | 12389 |

| 24 | Donations | 119888 | 52 | Viral RNA | 12145 |

| 25 | N95 | 116529 | 53 | Hardcore | 5213 |

| 26 | SARS | 105127 | 54 | Tang Zhihong | 3999 |

| 27 | Support of Wuhan | 99004 | 55 | Hubei Red Cross Society | 1199 |

| 28 | Isolation | 98366 | 56 | Pharmaceutical Research Institute | 1019 |

|

Panel C: The performance of text classification | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| The algorithms used to classify the text are naive Bayes, Support Vector Machine (SVM), and XGboost. The SVM learning algorithm is better in the “R2,” “Precision,” “Recall,” and “F1-score,” where “Precision” means how many of the samples predicted to be positive are truly positive samples, “Recall” indicates the total number of samples that were predicted correctly, and “F1-score” indicates the harmonic mean of “Precision” and “Recall.” | ||||

| Algorithm | R2 | Precision | Recall | F1-score |

| SVM | 0.963 | 0.73 | 0.71 | 0.70 |

| Naive Bayes | 0.815 | 0.72 | 0.65 | 0.61 |

| XGboost | 0.984 | 0.62 | 0.62 | 0.62 |

Fig. 1.

Screenshots of our textual database. The top screenshot (a) is from the official news media with Chinese keywords such as “lockdown”, “COVID-19″, “Zhong Nanshan”, “SARS”, “WHO”, “Isolation” etc. The bottom screenshot (b) is from Sina Weibo’s microblogs.

We randomly select 10,000 news items and 10,000 blogs as the training sets and manually read the 20,000 items. The attitude reflected in the news or on blogs was judged by manual reading. All the texts were divided into the following tags: optimistic (+1), neutral (0), and pessimistic (−1). To ensure robustness, we perform the tests using Naive Bayes, SVM, and XGboost for the 20,000 training dataset and compare their performance on the test sets (Table 1, Panel C).

The training results of the three algorithms are relatively reliable, as the R-squared values of the SVM and XGboost algorithms are both over 0.95. Table 1, Panel C shows that SVM is better in its classification performance of “Precision,” “Recall,” and “F1-score,” where the results are all over 70 %. Therefore, the SVM algorithm is selected to classify all the textual data.

Similar to Antweiler and Frank (2004), we develop our COVID-19 sentiment index using the following model.

| (1) |

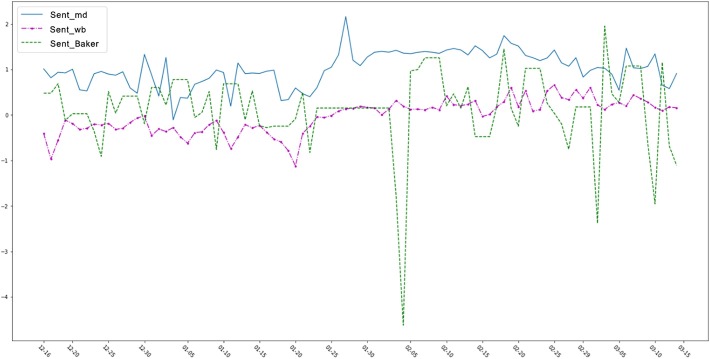

where “plat” is md (the official news media) or wb (the Sina Weibo), representing the amount of news or blogs reflecting an optimistic mood from the md or wb source, and Nplat represents the number of news or blog sources reflecting emotions. The constructed sentiment indices are shown in Fig. 2 . Our COVID-19 sentiment indices are continuous variables. The higher the index, the more optimistic the mood.

Fig. 2.

COVID-19 sentiment indices. The solid line depicts the COVID-19 sentiment index “Sent_md,” which measures the aggregate textual tone in 1,815,179 pieces of news. The dotted line depicts the COVID-19 sentiment index “Sent_wb,” which measures the aggregate textual tone of 4,519,293 microblogs from Sina Weibo. The sample period extends from December 17, 2019 through March 13, 2020. The dashed line depicts the BW sentiment index “Sent_Baker,” which was developed by Baker and Wurgler (2006, 2007).

Compared to Sina Weibo, the official news media is more optimistic. The Topics discussed on Sina Weibo are diverse and pessimistic, and negative emotions spread quickly. Moreover, the number of microblogs grew larger than previous times as people had to stay home for social distancing measures. This phenomenon is observable in Fig. 1. The COVID-19 sentiment variable of the Sina Weibo platform is significantly lower than that of the official news media. Furthermore, we find that most blogs were posted on the Internet after 3:00 pm when the Chinese stock market closes. The sentiment regarding COVID-19 can be observed on the second trading day.

To examine the differences between traditional BW sentiment and our COVID-19 sentiments, we measure the daily BW sentiment using six factors—the value-weighted average closing price on closed-end mutual funds, turnover, the annual number and first-day returns of IPOs, gross annual equity share divided by total issuance, and year-end market-to-book ratios. The BW index is a measure of sentiment based on Chinese stock market indicators, but our sentiments are based on COVID-19 discussions.

2.2. Stock returns, turnover rates, and control variables

Daily stock returns and turnover rates were retrieved for the period from December 17, 2019 to March 13, 2020 from the Wind database. We exclude financial companies from all A-share listed companies, as non-financial and financial firms are hardly comparable (Fama and French, 1992). Our main sample consists of 3,699 listed companies. Daily returns and turnover rates of listed companies are selected as the key dependent variables of the Chinese stock market, and value-weighted returns are selected to assess market returns. Table 2 presents the definitions and sources of the variables.

Table 2.

Variable definitions and summary statistics.

|

Panel A: Variable Definitions | ||

|---|---|---|

| Variable | Source | Definition |

| Key dependent variables | ||

| Ri | Wind Database | Daily returns of Chinese stock market listed firms |

| Turnover | Wind Database | Daily turnover rates of Chinese listed firms |

| Net_margin | Wind Database | Daily net value amount of margin trading activity |

| Net_short | Wind Database | Daily net volume of short-selling activity |

| Turnover_margin | Wind Database | Daily net turnover of margin trading activity |

| Turnover_short | Wind Database | Daily net turnover of short-selling activity |

| Key independent variables | ||

| Sent_md | Official media | Daily COVID-19 sentiment developed from news media |

| Sent_wb | Sina Weibo | Daily COVID-19 sentiment developed from Sina Weibo |

| Sent_Baker | Wind Database | Baker and Wurgler (2006, 2007) |

| mdPos | Official media | Daily proportion of optimistic news on the official media |

| mdNeu | Official media | Daily proportion of neutral news on the official media |

| mdNeg | Official media | Daily proportion of pessimistic news on the official media |

| wbPos | Sina Weibo | Daily proportion of optimistic news on Sina Weibo |

| wbNeu | Sina Weibo | Daily proportion of neutral news on Sina Weibo |

| wbNeg | Sina Weibo | Daily proportion of pessimistic news on Sina Weibo |

| Main control variables | ||

| Rm | Wind Database | Daily value-weighted returns of the Chinese stock market |

| Gold | Wind Database | Daily returns of AU.SHF |

| Cash | Wind Database | Cash holdings and equivalents divided by total assets (2019Q4) |

| Leverage | Wind Database | Interest-bearing bonds divided by total assets (2019Q4) |

| Roa | Wind Database | Return on total assets (2019Q4) |

| Mkt_cap | Wind Database | Logarithm of the market value of firms (2019Q4) |

| BM | Wind Database | The book-to-market ratio of listed firms (2019Q4) |

|

Panel B: Summary Statistics | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| This table reports the summary statistics for the variables in our analysis. It contains the P25, P50, P75 percentiles means, standard deviations (Sd) and the number of observations. | ||||||

| Variables | P25 | P50 | P75 | Mean | Sd | N |

| Ri | −1.503 | 0.142 | 1.672 | 0.132 | 3.408 | 208481 |

| Turnover | 0.919 | 1.948 | 4.243 | 3.425 | 4.067 | 208481 |

| Sent_md | −0.440 | 0.986 | 0.853 | 1.047 | 0.346 | 210843 |

| Sent_wb | −0.719 | 0.112 | 0.671 | −0.013 | 0.367 | 210843 |

| Sent_Baker | −0.249 | 0.148 | 0.516 | 0.000 | 1.000 | 210843 |

| mdpos | 0.383 | 0.541 | 0.630 | 0.519 | 0.130 | 210843 |

| mdneu | 0.168 | 0.240 | 0.431 | 0.300 | 0.133 | 210843 |

| mdneg | 0.154 | 0.163 | 0.199 | 0.181 | 0.044 | 210843 |

| wbpos | 0.308 | 0.398 | 0.459 | 0.385 | 0.097 | 210843 |

| wbneu | 0.165 | 0.200 | 0.255 | 0.226 | 0.085 | 210843 |

| wbneg | 0.346 | 0.377 | 0.431 | 0.389 | 0.065 | 210843 |

| Rm(value-weighted) | −0.355 | 0.354 | 0.989 | 0.0754 | 1.711 | 210843 |

| Rm(Equal-Weighted) | −0.548 | 0.304 | 1.290 | 0.159 | 2.015 | 210843 |

| Gold | −0.338 | 0.210 | 0.506 | 0.093 | 1.092 | 210843 |

| Cash | 0.109 | 0.183 | 0.297 | 0.224 | 0.159 | 210558 |

| Leverage | 0.022 | 0.129 | 0.263 | 0.168 | 0.292 | 210558 |

| Roa | 1.220 | 3.830 | 7.442 | 2.733 | 14.427 | 210615 |

| Mkt_Cap | 21.786 | 22.352 | 23.155 | 22.557 | 1.069 | 210444 |

| BM | 0.246 | 0.397 | 0.630 | 0.462 | 0.356 | 207993 |

We control for the price of gold, which is a safe haven asset sought under conditions of increased risk, to capture the impact of COVID-19 on market fundamentals. We also extract data on cash reserves and leverage from 2019Q4 reports. We determine that the average of cash reserves and leverage was down in the latest 2020Q1 reports. Cash is calculated by dividing cash reserves by total assets. Firms hoard cash for precautionary motives (Almeida et al., 2004; Hadlock and Pierce, 2010). Leverage is equal to long-run debt divided by total assets. These two firm-level control variables represent various financial strengths when COVID-19 spreads. We also control for Roa, return on assets, which is computed as quarterly income before extraordinary items over total assets. Mktcap is calculated as the logarithm of market equity. BM is calculated as the book value of firm equity divided by the market valuation.

The daily COVID-19 sentiment is merged to firms’ daily stock returns. Stock market data are not available for the Chinese New Year or weekends, so the sentiments’ missing stock values were dropped. The final dataset consists of 208,481 daily observations from December 17, 2019 to March 13, 2020 using individual fixed effects; 207,010 daily observations using firm-level characteristic control variables.

The summary statistics of the above variables are reported in Panel B of Table 2, which demonstrates that the two sentiments constructed by the official news media andSina microblogs differ significantly. Compared with the news media, discussion about COVID-19 on Sina Weibo (Sent_wb) is more negative. The mean of Sent_wb also had a negative value (−0.013), whereas that of Sent_md was 1.047. The standard deviations of Sent_md and Sent_wb were 0.346 and 0.367, respectively.

3. Methodology

We next apply our empirical model to test the association between individual stock returns and turnover rates and the COVID-19 sentiments. The COVID-19 health crisis evolves over time and according to the status of our control over it. To examine the predictive impact of the COVID-19 sentiment on the Chinese stock market returns and activities, the following main regression models are used.

| (2) |

where R i,t measures the listed firm on trading day t. sent plat represents the COVID-19 sentiments, where Sent_md and Sent _wb at day t-1 and Sent_Baker is calculated using the Baker and Wurgler’s construction. Rm,t−1 measures the value-weighted return among all listed firms as market returns at time t-1. Gold describes the return of the safe haven asset, gold. X i is a set of firm controls, and TIMEt represents weekday and month fixed effects.

For trading activity, we test the association between the listed firms’ turnover rates and COVID-19 sentiments using a similar regression model.

| (3) |

Furthermore, to study the impact of sentiment changes on stock returns, the following model is designed.

| (4) |

As opposed to Model (2), this model replaces the sentiment variables with the first-order difference of the sentiment indices. Therefore, when the variable Dsentplat is greater than 0, it means that public sentiment about COVID-19 is causing a positive shift. This could have a significant impact on stock returns.

Similarly, we performed a robustness check using variables mdPos, mdNeu, mdNeg, wbPos, wbNeu, and wbNeg, which are the proportions of messages to the three different sentiment tags over the total official news media (md) and Sina Weibo (wb) blogs to the sentiment indices instead. We also use equal-weighted returns among all listed firms as an alternative proxy to the market.

4. Empirical results

4.1. Main results and robustness tests

Table 3 shows the correlations between the key variables. Both the COVID-19 sentiment indices have strong positive correlations with stock market returns and turnover rates, as expected.

Table 3.

Correlation matrix.

| Variables | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | Ri | 1 | |||||

| (2) | Rm | 0.452*** | 1 | ||||

| (3) | Turnover | 0.186*** | 0.028*** | 1 | |||

| (4) | Gold | −0.095*** | −0.280*** | −0.022*** | 1 | ||

| (5) | Sent_md | 0.126*** | 0.297*** | 0.064*** | −0.044*** | 1 | |

| (6) | Sent_wb | 0.036*** | 0.102*** | 0.102*** | −0.126*** | 0.581*** | 1 |

This table exhibits the correlations between the main variables, where Sent_md and Sent_wb represent the COVID-19 sentiments of media news and Sina Weibo, respectively. ***indicates a 1% significance level.

When COVID-19 is discussed positively and optimistically on one day, the listed firms have higher average returns the next trading day over the entire sample period (Table 4 ). As seen in Panel A of Table 4, Columns (1) and (4) present the fact that more optimistic discussions about COVID-19 in the official news media result in higher returns the next day. The results exhibited in the first four columns include firm fixed effects instead of the firm-level control variables. Compared to the sentiment from Sina Weibo in Columns (2) and (5), the official media’s effects were stronger than those of private microblogs. For example, the results in Column (4) imply that a one standard deviation higher exposure to media-generated COVID-19 sentiment was associated with 34.25 % (i.e., 0.99*0.346) higher returns for the sentiment Sent_md and 24.88 % (= 0.678*0.367) higher returns for the variable Sent_wb. Regarding concerns about COVID-19, exogenous and non-financial sentiment is verified to positively predict stock returns. However, for the daily BW index, the result is not significant during this extreme period.

Table 4.

Effects of COVID-19 and BW sentiments on the Chinese stock market.

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Panel A:Dependent Variable: Returns | ||||||

| Sent_md t-1 | 1.035*** | 0.990*** | ||||

| (68.74) | (72.22) | |||||

| Sent_wb t-1 | 0.539*** | 0.678*** | ||||

| (29.62) | (42.95) | |||||

| Sent_Baker t-1 | −0.014 | −0.020** | ||||

| (−0.85) | (−2.23) | |||||

| Ri,t-1 | 0.059*** | 0.059*** | 0.060*** | |||

| (13.74) | (13.60) | (14.32) | ||||

| Rm,t-1 | 0.127*** | 0.207*** | 0.167*** | |||

| (16.23) | (25.14) | (21.07) | ||||

| Gold t-1 | −0.024** | −0.042*** | −0.060*** | |||

| (−2.54) | (−4.60) | (−6.15) | ||||

| Cash | −0.014 | −0.014 | −0.000 | |||

| (−0.27) | (−0.27) | (−0.00) | ||||

| Leverage | −0.010 | −0.010 | −0.012 | |||

| (−0.38) | (−0.38) | (−0.43) | ||||

| Roa | 0.003*** | 0.003*** | 0.003*** | |||

| (3.90) | (3.93) | (4.18) | ||||

| Mkt_cap | 0.040*** | 0.040*** | 0.040*** | |||

| (5.98) | (5.89) | (5.79) | ||||

| BM | −0.094*** | −0.094*** | −0.100*** | |||

| (−4.65) | (−4.59) | (−4.77) | ||||

| constant | 0.805*** | 0.394*** | −0.091*** | −0.020 | −0.214 | −0.849*** |

| (30.96) | (14.61) | (−3.43) | (−0.13) | (−1.38) | (−5.36) | |

| Time FE | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Firm FE | YES | YES | YES | NO | NO | NO |

| N | 208481 | 208481 | 204851 | 207010 | 207010 | 203389 |

| adj. R2 | 0.039 | 0.013 | 0.008 | 0.074 | 0.042 | 0.030 |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Panel B: Dependent Variable: Turnover | ||||||

| Sent_md t-1 | 0.096*** | 0.112*** | ||||

| (10.76) | (14.93) | |||||

| Sent_wbt-1 | 0.207*** | 0.046*** | ||||

| (12.41) | (4.93) | |||||

| Sent_Bakert-1 | 0.025** | −0.124*** | ||||

| (2.14) | (−22.18) | |||||

| Turnoveri,t-1 | 0.845*** | 0.845*** | 0.844*** | |||

| (221.61) | (221.59) | (218.82) | ||||

| Goldt-1 | 0.178*** | 0.170*** | 0.209*** | |||

| (30.57) | (29.45) | (34.13) | ||||

| Cash | 0.426*** | 0.399*** | 0.422*** | |||

| (10.71) | (9.98) | (10.48) | ||||

| Leverage | −0.073*** | −0.078*** | −0.070*** | |||

| (−4.51) | (−4.85) | (−4.33) | ||||

| Roa | 0.001*** | 0.001*** | 0.001*** | |||

| (3.31) | (3.54) | (3.48) | ||||

| Mkt_cap | −0.048*** | −0.050*** | −0.048*** | |||

| (−12.75) | (−13.16) | (−12.46) | ||||

| BM | −0.395*** | −0.401*** | −0.394*** | |||

| (−29.43) | (−29.65) | (−29.08) | ||||

| constant | 3.082*** | 3.191*** | 2.943*** | 1.606*** | 1.602*** | 1.555*** |

| (109.63) | (105.98) | (105.95) | (17.80) | (17.63) | (17.07) | |

| Time FE | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Firm FE | YES | YES | YES | NO | NO | NO |

| N | 208481 | 208481 | 204851 | 207010 | 207010 | 203389 |

| adj. R2 | 0.023 | 0.024 | 0.013 | 0.741 | 0.741 | 0.739 |

This table shows the results of OLS regressions regarding the impact of COVID-19 sentiments on Chinese stock market returns and turnover rates. The dependent variables are returns in Panel A and turnover rates in Panel B. Sent_mdt-1 is the COVID-19 sentiment constructed on the official news media. Sent_wbt-1 is the COVID-19 sentiment constructed on the Sina Weibo microblogs. Sent_Bakert is the BW sentiment. Ri,t-1 represents the returns of a firm listed on the Chinese stock market and Rm,t-1 is daily value-weighted returns among all Chinese listed firms’ returns. Gold t-1 is the returns on AU.SHF. Firm control variables include Cash, Leverage, Roa, Mkt_cap, and BM. This table shows the predictive effect of COVID-19 sentiments on the trading activity of the Chinese stock market the next day. t-statistics based on robust standard errors appear in parentheses. *p < 0.1, ** p < 0.05, *** p < 0.01.

Panel B of Table 4 analyzes stock turnover rates in response to the COVID-19 and BW sentiments. Columns (1) and (4) show that more optimistic discussion of COVID-19 in the official news media results in higher turnover rates the next day. When we add the control variables and time fixed effects, the results remain significant for both sentiments. The higher the sentiments on COVID-19, for example, “No more deaths reported,” the higher the stock turnover rates. Next, Columns (2) and (5) indicate that similar results are obtained using the Sina Weibo sentiment. For Columns (3) and (6), the BW sentiment is not stable for one day predictions of stock turnover rates.

Table 5 presents the fact that changes in COVID-19 and BW sentiments are positively associated with stock markets. Interestingly, changes in Sina Weibo’s sentiment has a somewhat greater effect on the stock market than those of the official news media and BW sentiments. The official news media is relatively traditional, objective, and credible in terms of public psychological cognition, while Sina Weibo is a popular self-media platform that has become popular in recent years. The shift in Sina Weibo’s sentiment is rapid and intense. As expected, compared with Columns (2) and (5), the impact of differences in Sent_wb is greater on firm returns, as shown in Columns (1), (3), (5), and (6).

Table 5.

Effects of changes in COVID-19 and BW sentiments.

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent Variable: Returns | ||||||

| Dsent_mdt | 0.045*** | 0.036*** | ||||

| (6.36) | (5.77) | |||||

| Dsent_wbt | 0.111*** | 0.097*** | ||||

| (12.49) | (14.42) | |||||

| Dsent_Bakert | 0.064*** | 0.040*** | ||||

| (8.52) | (8.03) | |||||

| Rm,t | 1.147*** | 1.165*** | 1.143*** | 1.172*** | 1.187*** | 1.168*** |

| (199.04) | (194.48) | (202.78) | (247.83) | (240.11) | (248.15) | |

| Goldt | 0.156*** | 0.149*** | 0.149*** | |||

| (23.99) | (22.81) | (22.19) | ||||

| Cash | 0.046 | 0.046 | 0.028 | |||

| (0.88) | (0.88) | (0.52) | ||||

| Leverage | −0.008 | −0.008 | −0.007 | |||

| (−0.30) | (−0.30) | (−0.25) | ||||

| Roa | 0.003*** | 0.003*** | 0.003*** | |||

| (4.31) | (4.32) | (4.77) | ||||

| Mkt_cap | 0.042*** | 0.042*** | 0.046*** | |||

| (7.18) | (7.18) | (7.59) | ||||

| BM | −0.104*** | −0.104*** | −0.103*** | |||

| (−5.80) | (−5.80) | (−5.59) | ||||

| constant | 0.190*** | 0.199*** | 0.171*** | −0.816*** | −0.806*** | −0.901*** |

| (9.17) | (9.59) | (8.18) | (−6.15) | (−6.07) | (−6.61) | |

| Time FE | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Firm FE | YES | YES | YES | NO | NO | NO |

| N | 208481 | 208481 | 201221 | 207022 | 207022 | 199776 |

| adj. R2 | 0.205 | 0.206 | 0.207 | 0.316 | 0.317 | 0.319 |

This table shows the results of OLS regressions regarding the impact of changes in COVID-19 sentiments on Chinese stock market returns. The dependent variables are returns, Dsent_mdt is the first-order difference of the official media’s COVID-19 sentiment. Dsent_wbt is the changes in the Sina Weibo’s COVID-19 sentiment. Dsent_Bakert is changes in the BW sentiment. Rm,t-1 is the daily value-weighted return among all Chinese listed firms’ returns. Gold t represents returns on AU.SHF. Firm control variables include Cash, Leverage, Roa, Mkt_cap, and BM. This table shows the effect of changes in the COVID-19 sentiments on Chinese stock market returns. T-statistics based on robust standard errors appear in parentheses. *p < 0.1, ** p < 0.05, *** p < 0.01.

Finally, instead of sentiment indices, we consider the proportion of news in various emotions as a robustness test. Panel A of Table 6 shows that the three different sentiments all have significant predictive power. Columns (1) and (4) present that the higher proportion of optimistic news in total, the higher the returns the next trading day. However, stock market returns respond negatively to the proportions of both neutral and pessimistic news. This suggests that “No good news is bad” during the fearsome period while the pandemic was spreading, as indicated in Columns (2) and (5).

Table 6.

Alternative sentiment measures.

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent Variable: Returns | ||||||

| mdPost-1 | 14.495*** | 14.566*** | ||||

| (91.17) | (94.57) | |||||

| mdNeut-1 | −10.142*** | −10.225*** | ||||

| (−63.35) | (−65.20) | |||||

| mdNegt-1 | −16.216*** | −16.191*** | ||||

| (−64.12) | (−64.52) | |||||

| Ri,t-1 | 0.040*** | 0.038*** | 0.039*** | 0.063*** | 0.060*** | 0.062*** |

| (4.71) | (4.56) | (4.66) | (14.36) | (13.75) | (14.30) | |

| Rm,t-1 | −0.064*** | 0.046*** | 0.137*** | −0.090*** | 0.022*** | 0.113*** |

| (−5.43) | (3.96) | (11.64) | (−11.23) | (2.72) | (14.20) | |

| Gold t-1 | −0.061*** | −0.211*** | 0.170*** | −0.064*** | −0.215*** | 0.168*** |

| (−6.79) | (−22.39) | (17.15) | (−7.25) | (−23.19) | (17.23) | |

| Cash | −0.015 | −0.015 | −0.014 | |||

| (−0.29) | (−0.28) | (−0.26) | ||||

| Leverage | −0.010 | −0.010 | −0.010 | |||

| (−0.38) | (−0.38) | (−0.37) | ||||

| Roa | 0.003*** | 0.003*** | 0.003*** | |||

| (3.88) | (3.93) | (3.90) | ||||

| Mkt_cap | 0.040*** | 0.040*** | 0.040*** | |||

| (6.02) | (5.93) | (5.92) | ||||

| BM | −0.094*** | −0.094*** | −0.094*** | |||

| (−4.69) | (−4.63) | (−4.58) | ||||

| constant | −5.541*** | 4.448*** | 2.924*** | −6.439*** | 3.612*** | 2.051*** |

| (−80.13) | (66.89) | (65.37) | (−39.28) | (21.74) | (12.88) | |

| Time FE | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Firm FE | YES | YES | YES | NO | NO | NO |

| N | 208426 | 208426 | 208426 | 207010 | 207010 | 207010 |

| adj. R2 | 0.091 | 0.056 | 0.056 | 0.095 | 0.059 | 0.058 |

This table exhibits the results of the robustness tests of predictive effect of COVID-19 sentiments on Chinese stock market returns. The dependent variable is the daily returns of listed firms. In table, mdPos, mdNeu, and mdNeg represent the proportion of optimistic, neutral, and pessimistic news, respectively, which are obtained by dividing the total number of news items reported by the official media. Rm,t-1 represents daily value-weighted returns of the Chinese stock market. Gold t-1 is the returns on AU.SHF. Firm-level characteristics control variables include Cash, Leverage, Roa, Mkt_cap, and BM. T-statistics based on robust standard errors appear in parentheses. *p < 0.1, ** p < 0.05, *** p < 0.01.

Panel B of Table 6 shows the robustness for the Sina Weibo’s sentiment. The effect is less than the sentiment of the official media news. Moreover, Columns (2) and (5) confirm that neutral blogs drove up the negativity.

Furthermore, we test robustness with the equally weighted returns among the listed banks (Table 7 ), where sentiment is still significant at the 1% level for prediction.

Table 7.

Alternative market returns.

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent Variable: Returns | ||||||

| Sent_md t-1 | 1.035*** | 1.004*** | 1.006*** | |||

| (68.74) | (71.68) | (72.89) | ||||

| Sent_wb t-1 | 0.539*** | 0.629*** | 0.634*** | |||

| (29.62) | (39.02) | (39.96) | ||||

| Ri,t-1 | 0.053*** | 0.053*** | 0.087*** | 0.087*** | ||

| (5.12) | (5.12) | (18.52) | (18.37) | |||

| Rm,t-1(equal-weighted) | 0.039*** | 0.100*** | 0.007 | 0.068*** | ||

| (3.42) | (8.59) | (1.08) | (9.70) | |||

| Gold t-1 | −0.084*** | −0.119*** | −0.082*** | −0.118*** | ||

| (−8.94) | (−13.37) | (−8.81) | (−13.34) | |||

| Cash | −0.016 | −0.016 | ||||

| (−0.30) | (−0.29) | |||||

| Leverage | −0.010 | −0.010 | ||||

| (−0.37) | (−0.37) | |||||

| Roa | 0.002*** | 0.002*** | ||||

| (3.78) | (3.80) | |||||

| Mkt_cap | 0.039*** | 0.039*** | ||||

| (5.83) | (5.73) | |||||

| BM | −0.091*** | −0.091*** | ||||

| (−4.50) | (−4.42) | |||||

| constant | 0.805*** | 0.394*** | 0.829*** | 0.574*** | −0.013 | −0.267* |

| (30.96) | (14.61) | (37.17) | (24.65) | (−0.09) | (−1.72) | |

| Time FE | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Firm FE | YES | YES | YES | YES | NO | NO |

| N | 208481 | 208481 | 208426 | 208426 | 207010 | 207010 |

| adj. R2 | 0.039 | 0.013 | 0.068 | 0.033 | 0.072 | 0.037 |

This table lists the results of OLS regression analysis regarding the impact of COVID-19 sentiments on Chinese stock market returns with Rm,t-1, the equal-weighted return. Sent_mdt-1 is the COVID-19 sentiment constructed on the official news media. Sent_wbt-1 is the COVID-19 sentiment constructed on Sina Weibo microblogs. Ri,t-1 represents returns of a firm listed on the Chinese stock market. Goldt-1 represents the returns on AU.SHF. Firm-level characteristics control variables include Cash, Leverage, Roa, Mkt_cap, and BM. This table shows the predictive effect of COVID-19 sentiments on the trading activity of the Chinese stock market the next day. T-statistics are based on the robust standard errors in parentheses. *p < 0.1, ** p < 0.05, *** p < 0.01.

4.2. Margin trading and short selling activities

All columns in Table 8 show the regression of the value of margin trades and volume of short selling. Both the COVID-19 sentiments could predict the Yuan volume of margin trading and number volume of short selling activities. These are impacted by heterogeneous beliefs. Optimistic investors expect that the price will rise continuously, while investors with pessimistic valuation may think that the “infectious diseases” would continue to bring negative effects to firms. Since the current pandemic is a serious health crisis, which is different from the past financial crises. The spread of the virus forced governments to implement significant containment measures such as social distancing, lockdowns, and business shutdowns, which in turn resulted in adverse economic effects on firms and industries. Government implemented strict containment measures to halt the spread of the virus, resulting an increase in sentiment, decline in economic activities and severe loss of revenue and income for businesses. Pessimistic investors expect that firms would face significant revenue drops during the pandemics, so that they may establish short positions in the stocks of firms. Furthermore, the results show that the net value of margin trading increases as the historical individual returns (Columns (3) and (4)), while the number volume of short selling decreases as the past individual returns, as presented in Columns (7) and (8).

Table 8.

Margin trading and short-selling activities.

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Net_margin | Net_short | |||||||

| Sent_md t-1 | 0.053*** | 0.049*** | 0.223*** | 0.215*** | ||||

| (9.97) | (8.78) | (4.48) | (4.26) | |||||

| Sent_wb t-1 | 0.015** | 0.028*** | 0.156** | 0.191*** | ||||

| (2.00) | (3.85) | (2.18) | (2.61) | |||||

| Ri,t-1 | 0.030*** | 0.030*** | −0.032* | −0.032* | ||||

| (12.85) | (12.84) | (−1.93) | (−1.93) | |||||

| Rm,t-1 | −0.012*** | −0.008** | 0.082*** | 0.103*** | ||||

| (−3.09) | (−2.13) | (3.28) | (4.03) | |||||

| Cash | −0.063** | −0.063** | −0.143 | −0.143 | ||||

| (−2.45) | (−2.45) | (−1.17) | (−1.17) | |||||

| Leverage | −0.001 | −0.001 | 0.037 | 0.037 | ||||

| (−0.14) | (−0.14) | (0.48) | (0.48) | |||||

| Roa | −0.000 | −0.000 | −0.001 | −0.001 | ||||

| (−1.43) | (−1.43) | (−0.47) | (−0.47) | |||||

| Mkt_cap | 0.061*** | 0.061*** | 0.017 | 0.017 | ||||

| (6.33) | (6.33) | (0.26) | (0.26) | |||||

| BM | −0.049*** | −0.049*** | 0.145 | 0.145 | ||||

| (−4.83) | (−4.83) | (1.12) | (1.12) | |||||

| constant | 0.141*** | 0.108*** | −1.181*** | −1.195*** | 0.001 | −0.050 | −0.401 | −0.403 |

| (12.32) | (8.66) | (−5.65) | (−5.72) | (0.01) | (−0.42) | (−0.29) | (−0.29) | |

| Time FE | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Firm FE | YES | YES | NO | NO | YES | YES | NO | NO |

| N | 210843 | 210843 | 207010 | 207010 | 210843 | 210843 | 207010 | 207010 |

| adj. R2 | 0.002 | 0.001 | 0.006 | 0.005 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 |

This table shows the regression results for the value of margin trades and the volume of short-selling. Both COVID-19 sentiments were able to predict the Yuan volume of margin trading and volume of short-selling activities. The results indicate that the net value of margin trading increased as historical individual returns, while the volume of short-selling decreased as past individual returns. Firm-level characteristics control variables include Cash, Leverage, Roa, Mkt_cap, and BM. T-statistics based on robust standard errors appear in parentheses. * p < 0.1, ** p < 0.05, *** p < 0.01.

Table 9 shows the regression of the turnover of margin trades and short selling. Both the COVID-19 sentiments could predict the turnover rates. Official orders and containment measures are efficient to reduce the confirmed cases. The mood of investors change from panic to optimism so that both buying and selling become active. The results show that both the turnover rates are increasing as the sentiment increases, but selling the stock short is more constrained, as shown in Columns (5)–(8).

Table 9.

Margin trading and short selling turnover.

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Turnover_margin | Turnover_short | |||||||

| Sent_md t-1 | 6.071*** | 5.797*** | 0.098*** | 0.089*** | ||||

| (22.10) | (21.55) | (6.99) | (6.65) | |||||

| Sent_wb t-1 | 4.650*** | 5.728*** | 0.030* | 0.050*** | ||||

| (17.60) | (19.44) | (1.82) | (2.93) | |||||

| Ri,t-1 | 0.689*** | 0.688*** | −0.016*** | −0.016*** | ||||

| (17.10) | (17.04) | (−4.30) | (−4.31) | |||||

| Rm,t-1 | 0.698*** | 1.278*** | 0.055*** | 0.062*** | ||||

| (9.89) | (15.59) | (10.14) | (10.94) | |||||

| Cash | −0.125 | −0.127 | −0.526*** | −0.526*** | ||||

| (−0.21) | (−0.21) | (−5.31) | (−5.31) | |||||

| Leverage | 0.127 | 0.126 | −0.037* | −0.037* | ||||

| (0.50) | (0.50) | (−1.83) | (−1.83) | |||||

| Roa | 0.051*** | 0.051*** | 0.001*** | 0.001*** | ||||

| (6.24) | (6.22) | (3.10) | (3.10) | |||||

| Mkt_cap | −0.627*** | −0.627*** | −0.056*** | −0.056*** | ||||

| (−6.47) | (−6.46) | (−5.38) | (−5.38) | |||||

| BM | −2.616*** | −2.616*** | 0.013 | 0.013 | ||||

| (−7.62) | (−7.62) | (0.50) | (0.50) | |||||

| constant | 1.611*** | 0.574** | 17.308*** | 17.831*** | −0.224*** | −0.283*** | 1.160*** | 1.132*** |

| (6.18) | (2.03) | (8.07) | (8.28) | (−8.44) | (−10.17) | (4.99) | (4.88) | |

| Time FE | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Firm FE | YES | YES | NO | NO | YES | YES | NO | NO |

| N | 210751 | 210751 | 206921 | 206921 | 210824 | 210824 | 206992 | 206992 |

| adj. R2 | 0.012 | 0.006 | 0.017 | 0.013 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.002 | 0.002 |

This table shows the regression results for margin trade and short-selling turnover. Both COVID-19 sentiments were able to predict the turnover. These results indicate that both turnover rates are increasing as the sentiment increases, but short-selling the stock is more constrained, as shown in Columns (5)–(8). Firm-level characteristics control variables include Cash, Leverage, Roa, Mkt_cap, and BM. T-statistics based on robust standard errors appear in parentheses. *p < 0.1, ** p < 0.05, *** p < 0.01.

5. Conclusion

In this paper, we construct COVID-19 sentiment indices using 6.3 million textual data from the official news media and Sina Weibo (microblog). Over the period from December 17, 2019 to March 13, 2020, COVID-19 is widely reported and discussed. Our aim is to diagnose the impact of media sentiment regarding COVID-19 on the Chinese stock market.

Assistants are employed to carefully read 10,000 news and 10,000 blogs. The attitude reflected in the news or on blogs is judged vis-a-vis manual reading. To ensure robustness, we apply Naive Bayes, SVM, and XGboost processing algorithms for training. Finally, SVM is selected to process the entire dataset because of its superior performance and then measure the panic sentiment in response to COVID-19 as two continuous variables.

Considering the differences of opinion between the official media sources and Sina Weibo, we discover that the Chinese stock market returns and turnover rates were positively predicted by our sentiments with both platforms. We further find that stock markets reacted proactively to growth sentiments. However, the traditional BW sentiment could not predict Chinese stock market activity during the pandemic period. Moreover, margin trading and short-selling activities increased with the increase of sentiments. Specifically, the optimistic guidance of Sina Weibo further increased returns. Overall, these results illustrate how the effects of the health crisis were amplified through the official media sentiments.

Acknowledgement

This document is the results of the research project funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China under Grant No. 71873070 and by the Nankai University, Grant No. ZB21BZ0308.

Footnotes

The views expressed are those of the authors and do not represent the views of the Nankai University.

References

- Almeida H., Campello M., Weisbach M.S. The cash flow sensitivity of cash. J. Finance. 2004;59(4):1777–1804. [Google Scholar]

- Antweiler W., Frank M.Z. Is all that talk just noise? The information content of internet stock message boards. J. Finance. 2004;59(3):1259–1294. [Google Scholar]

- Ashraf B.N. Stock Markets’ Reaction to COVID-19: Cases or Fatalities? Res. Int. Bus. Financ. 2020;54:54. doi: 10.1016/j.ribaf.2020.101249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker M., Wurgler J. Investor sentiment and the cross section of stock returns. J. Finance. 2006;61(4):1645–1680. [Google Scholar]

- Baker M., Wurgler J. Investor sentiment in the stock market. J. Econ. Perspect. 2007;21(2):129–151. [Google Scholar]

- Baker M., Wurgler J., Yuan Y. Global, local, and contagious investor sentiment. J. financ. econ. 2012;104(2):272–287. [Google Scholar]

- Baker S.R., Bloom N., Davis S.J., Kost K., Sammon M., Viratyosin T. NBER; 2020. The Unprecedented Stock Market Impact of COVID-19. Working Paper No. w26945. [Google Scholar]

- Barber B.M., Odean T. Trading is hazardous to your wealth: the common stock investment performance of individual investors. J. Finance. 2000;55(2):773–806. [Google Scholar]

- Barber B.M., Odean T., Zhu N. Do Retail Trades Move Markets? Rev. Financ. Stud. 2009;22(1):151–186. [Google Scholar]

- Bushee B.J., Core J.E., Guay W., Hamm S.J.W. The Role of the Business Press as an Information Intermediary. J. Account. Res. 2010;48(1):1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Chan W.S. Stock price reaction to news and No-News: drift and reversal after headlines. J. financ. econ. 2003;70(2):223–260. [Google Scholar]

- Chen M.H., Jang S.C., Kim W.G. The impact of the SARS outbreak on taiwanese hotel stock performance: an event-study approach. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2007;26(1):0–212. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhm.2005.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dellavigna S., Pollet J.M. Investor inattention and Friday earnings announcements. J. Finance. 2009;64(2):709–749. [Google Scholar]

- Edmans A., Garcia D., Norli O. Sports sentiment and stock returns. J. Finance. 2007;62(4):1967–1998. [Google Scholar]

- Fama E.F., French K.R. The cross-section of expected stock returns. J. Finance. 1992;47(2):427–465. [Google Scholar]

- Fang L., Peress J. Media coverage and the cross-section of stock returns. J. Finance. 2009;64(5):2023–2052. [Google Scholar]

- Fang L.H., Peress J., Zheng L. Social science Electronic Publishing; 2009. Does Your Fund Manager Trade on the News? Media Coverage, Mutual Fund Trading and Performance; pp. 3441–3466. [Google Scholar]

- Grullon G., Kanatas G., Weston J. Advertising, breadth of ownership, and liquidity. Electron. J. Publishing. 2002;17(2):439–461. Social Science. [Google Scholar]

- Hadlock C.J., Pierce J.R. New evidence on measuring financial constraints: moving beyond the kz index. Rev. Financ. Stud. 2010;23(5):1909–1940. [Google Scholar]

- Hirshleifer D., Shumway T. Good day sunshine: stock returns and the weather. J. Finance. 2003;58(3):1009–1032. [Google Scholar]

- Hirshleifer D., Teoh S.H. Limited attention, information disclosure, and financial reporting. J. Account. Econ. 2003;36(1–3):337–386. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplanski G., Levy H. Sentiment and stock prices: the case of aviation disasters. J. Financ. Econ. 2010;95(2):174–201. [Google Scholar]

- Loughran T., McDonald B. When is a liability not a liability? Textual analysis, dictionaries, and 10-ks. J. Finance. 2011;66(1):35–65. [Google Scholar]

- Ramelli S., Wagner A.F. Review of Corporate Finance Studies. Swiss Finance Institute Research Paper No. 20-12; 2020. Feverish stock price reactions to COVID-19. [Google Scholar]

- Shiller R.J. NBER; 1981. Do Stock Prices Move Too Much to Be Justified by Subsequent Changes in Dividends? Working Paper No. w0456. [Google Scholar]

- Siu A., Wong Y.C.R. Economic impact of SARS: the case of Hong Kong. Asian Econ. Pap. 2004;3(1):62–83. [Google Scholar]

- Tetlock P.C. Giving content to investor sentiment: the role of media in the stock market. J. Finance. 2007;62(3):1139–1168. [Google Scholar]

- Tetlock P.C. Does Public Financial News Resolve Asymmetric Information? Rev. Financ. Stud. 2010;23(9):3520–3557. [Google Scholar]

- Tetlock P.C., Saar-Tsechansky M., Macskassy S. More than words: quantifying language to measure firms’ fundamentals. J. Finance. 2008;63:1437–1467. [Google Scholar]