Abstract

Watson-Crick base pairing rules provide a powerful approach for engineering DNA-based nanodevices with programmable and predictable behaviors. In particular, DNA strand displacement reactions have enabled the development of an impressive repertoire of molecular devices with complex functionalities. By relying on DNA to function, dynamic strand displacement devices represent powerful tools for the interrogation and manipulation of biological systems. Yet, implementation in living systems has been a slow process due to several persistent challenges, including nuclease degradation. To circumvent these issues, researchers are increasingly turning to chemically modified nucleotides as a means to increase device performance and reliability within harsh biological environments. In this review, we summarize recent progress towards the integration of chemically modified nucleotides with DNA strand displacement reactions, highlighting key successes in the development of robust systems and devices that operate in living cells and in vivo. We discuss the advantages and disadvantages of commonly employed modifications as they pertain to DNA strand displacement, as well as considerations that must be taken into account when applying modified oligonucleotide to living cells. Finally, we explore how chemically modified nucleotides fit into the broader goal of bringing dynamic DNA nanotechnology into the cell, and the challenges that remain.

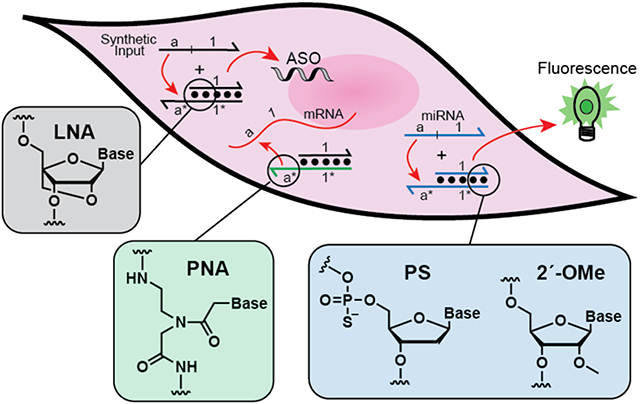

Graphical/Visual Abstract

Many of the most exciting applications of dynamic DNA nanotechnology lie at the interface with biology. This review discusses the integration of chemically modified nucleotides with DNA strand displacement reactions in order to construct more robust dynamic DNA nanodevices that operate efficiently in living systems.

1. INTRODUCTION

The well-characterized behavior and programmability of Watson–Crick base pairing have inspired the field of DNA nanotechnology. While the initial focus was on the construction and self-assembly of static nanostructures via hybridization of complementary strands, the field has rapidly expanded to encompass a myriad of dynamic systems with reconfigurable parts (Chen & Seeman, 1991; Kallenbach et al., 1983; Rothemund, 2006; Seeman, 1982; Winfree et al., 1998; Yurke et al., 2000). Molecular motors (Bath & Turberfield, 2007; Kay et al., 2007; Sherman & Seeman, 2004; Shin & Pierce, 2004), switchable nanostructures (Goodman et al., 2008; Rothemund, 2006; Sadowski et al., 2014; Yin et al., 2008), Boolean logic computation (Qian & Winfree, 2011; Seelig, Soloveichik, et al., 2006), and molecular sensors and amplifiers (Dirks & Pierce, 2004; Scheible et al., 2014; Zhang et al., 2007) have all been realized using dynamic DNA interactions.

Biomedical applications, such as molecular diagnostic and therapeutics (Bujold et al., 2018; Chakraborty et al., 2016; Chen et al., 2015; Li et al., 2017; Samanta et al., 2020; Tang et al., 2020), represent the primary motivation behind the development of many dynamic DNA nanodevices. By being constructed of DNA (and RNA) these devices are inherently compatible with genetic material, thereby facilitating the interception and/or manipulation of molecular information in living systems. Indeed, DNA circuits and other nanodevices functioning as molecular sensors and/or effectors of endogenous nucleic acids have recently been reported (Chatterjee et al., 2018; Douglas et al., 2012; Groves et al., 2016; Hemphill & Deiters, 2013; Rudchenko et al., 2013). Despite this progress, however, implementing DNA nanodevices within biological environments, and in particular living cells, remains extremely challenging. A key limitation is stability. While large DNA nanostructures have enhanced nuclease resistance (Chandrasekaran, 2021), the cellular half-life of short single-strand DNA is on the order of minutes (Fisher et al., 1993), leading to the rapid deterioration of device performance and potential misinterpretation of experimental results (Lacroix et al., 2019). Moreover, exogenously delivered DNA is susceptible to unintended interactions with cellular macromolecules and can trigger an immune response (Bartok & Hartmann, 2020; Fisher et al., 1993; Judge et al., 2005; Surana et al., 2015; Vollmer et al., 2004), resulting in toxic effects that can undermine the purpose of the device.

To combat these challenges, researchers have recently begun incorporating chemically modified nucleotides into their designs as a means to increase device performance and reliability within harsh biological environments. Chemical modifications to the phosphate backbone, sugar, and bases of DNA and RNA have been shown to dramatically enhance their stability towards nuclease-mediated degradation (Dar et al., 2016), and in some cases, reduce toxic off-target effects (Robbins et al., 2007). Table 1 lists chemical modifications that have been successfully employed in the construction of dynamic, intracellular DNA nanotechnology to date. Nanodevices capable of molecular computation, nucleic acid detection, and gene regulation in living cells have been realized using modified oligonucleotides (ONs) (Bratu et al., 2003; Kahan-Hanum et al., 2013; Kumar et al., 2011; Prigodich et al., 2009), which in most cases outperform their native DNA counterparts. Development of these devices borrowed heavily from design principles originally identified in the development of antisense ONs (ASOs), short interfering RNAs (siRNAs), and molecular beacons (MBs) (Aartsma-Rus et al., 2009; Bramsen et al., 2009; ElHefnawi et al., 2011; Fakhr et al., 2016; Naito & Ui-Tei, 2012; Rinaldi & Wood, 2018; Tyagi & Kramer, 1996; Valdés & Miller, 2019; Wang et al., 2009). Yet, strictly speaking, none of these nucleic acid technologies utilize toehold-mediated strand displacement, which underlies the design and operation of the vast majority of dynamic DNA devices (Figure 1) (DeLuca et al., 2020; Seelig, Yurke, et al., 2006; Simmel et al., 2019; Zhang & Seelig, 2011). Incorporation of chemically modified nucleotides into dynamic, strand displacement systems comes with its own unique set of design considerations that are actively being discovered and refined. Given the advantages offered by chemically modified nucleotides, and the progress already made, chemically modified nucleotides are expected to play a major role in the transition of dynamic DNA nanotechnology from the test tube into cells and higher organisms.

Table 1.

Modified nucleotides that have been employed in dynamic DNA nanotechnology.

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Nuclease resistance | Partial, isomer dependent | Partial | High | High | High |

| Duplex Thermostabilitya (ΔTm/bp) | Decreased (~0.5 °C) | Increased (~1 °C) | Increased (2–8 °C) | Increased (~1 °C) | Identical |

| Rate of Hybridizationa,b | Decreased (mixed isomers) | Decreased | Similar | Increased | Identical |

| Toxicity | High | Moderate | Moderate | Low | Low |

| Commercial Costc ($USD/bp) | 3.5e | 17e | 20e | 58f | 185g |

| In-House Costc,d ($USD/bp) | 0.5h | 1h | 1.5h | 2.5i | 2.7h |

Relative to unmodified DNA

The effect of a modification on hybridization kinetics is context-dependent

Commercial cost of native DNA ($USD/bp): 0.7; In-house cost of native DNA ($USD/bp): 0.25

Prepared using an Expedite 8909 DNA/RNA Synthesizer using manufacurer recommended prrotocols

Estimated cost if purchased from Integrated DNA Technologies, USA

Estimated cost if purchased from Panagene, South Korea

Estimated cost if purchased from Bio-Synthesis, USA

Estimated cost using monomers and reagents purchased from Glenn Research, USA

Estimated cost using monomers and reagents purchased from PolyOrg, USA

Figure 1.

Toehold-mediated strand displacement reactions. (a) DNA strand displacement via 3-way branch migration. DNA is depicted as lines with the half arrow indicating the 3′ end. A substrate strand having a single-stranded toehold domain (t*) and a branch migration domain (a*) is hybridized to an incumbent strand (OUT) to form duplex A. Strand displacement is initiated through binding of the invader strand (IN) to the toehold domain of A (via t/t*) followed by a 3-way branch migration process in which domain a on the invading strand displaces domain a on the incumbent strand through a series of reversible dissociation/hybridization events. The reaction is complete once the invader strand (IN) fully displaces the incumbent strand (OUT) from duplex A. Toeholds accelerate the rate of strand displacement by increasing the probability that the incumbent strand is successfully replaced by the invader once bound. (b) DNA strand displacement via 4-way branch migration. Two DNA duplexes (IN1 and IN2) bind to each other through a pair of complementary toehold domains (t1/t1* and t2/t2*) to form a Holliday junction. A 4-way branch migration process ensues, resulting in the formation of two new DNA duplexes (OUT1 and OUT2) having more base pairs than the initial DNA duplexes.

Herein, we review the use of chemically modified nucleotides in the design and construction of dynamic DNA devices whose operation is based on toehold-mediated DNA strand displacement. We focus on recent examples that show how these devices have been implemented in living cells, highlighting potential advantages of the modifications employed. Finally, we discuss design challenges and practical considerations associated with the use of chemically modified nucleotides and explore potential solutions that pave the way towards the broader adoption of modified nucleotides in the field of intracellular DNA nanotechnology.

2. COMMON CHEMISTRIES

In the first section, we discuss chemical modifications commonly employed in the development of ASOs, siRNAs, and related technologies. These modifications – phosphorothioate (PS), locked nucleic acids (LNA), and 2′-O-methyl (2′-OMe) – have been reviewed extensively in the context of therapeutic ONs (Eckstein, 2014; Hagedorn et al., 2018; Khvorova & Watts, 2017; Quemener et al., 2020; Roberts et al., 2020; Shen & Corey, 2018) (Table 1). Herein, we focus our attention on the application of these modifications to strand displacement, and more specifically, their use in the construction of robust, intracellular reaction systems.

2.1. Phosphorothioate linkages

The phosphorothioate modification – replacement of a non-bridging oxygen in the phosphodiester bond with sulphur (Table 1) – is perhaps the most widely used chemical modification in ON drug development (Crooke et al., 2017; Iwamoto et al., 2017; Monteith et al., 1999; Ramazeilles et al., 1994). The PS modification provides two benefits in this regard: (1) it dramatically increases the stability of ONs towards nuclease digestion and (2) facilitates cellular uptake of ONs through increased protein binding interactions (Crooke et al., 2020). Given these properties, it is not surprising that PS has found practical utility in the field of intracellular DNA nanotechnology, including the development of dynamic devices and sensors based on strand displacement (Gong et al., 2019; Groves et al., 2016; Iwamoto et al., 2017).

PS linkages have two stereoisomers, and thus, PS-modified ONs synthesized by standard methods will be a collection of diastereomers (Eckstein, 2014). Although strategies exist for controlling the stereochemical configuration at each PS linkage, these methods are non-trivial and effectively inaccessible to laboratories which do not specialize in ON synthesis (Roberts et al., 2020). As a result of being a diastereomeric mixture, PS modified ONs form less stable duplexes (lower melting temperature) with DNA and RNA relative to the native polymer (Wan et al., 2014) (Table 1). In the context of strand displacement, weakened binding interaction between ON components, especially at the toehold domain, are expected to alter reaction kinetics (Young & Wagner, 1991; Zhang & Winfree, 2009). For example, the Seelig group showed that placement of PS modifications on either terminus of DNA reaction components dramatically reduced the rate of strand displacement via 4-way branch migration relative to an identical unmodified system (Figure 2a) (Groves et al., 2016). Moreover, this effect was dependent on the length of the double-stranded region (Zhang & Winfree, 2009). Similarly, the Schulman group found that PS modifications dramatically reduced the rate of DNA strand displacement via 3-way branch migration (Fern & Schulman, 2017). These studies highlight a potential drawback of directly substituting PS linkages into previously optimized designs, and the importance of re-optimization following PS incorporation.

Figure 2.

Strand displacement systems involving PS modifications. (a) The strand displacement reaction with 4-way branch migration employed by the Seelig group. (b) Boolean AND and OR gates based on strand displacement via 4-way branch migration. The OR gate requires either Input A or Input B to activate fluorescence, whereas the AND gate requires both. Panels (a) and (b) are reproduced with permission from Groves et al., 2016. Copyright Springer Nature. (c) Schematic illustration of a cascaded HCR device. A YES logic gate is shown. Hairpin HA is activated (exposure of domain 1*) upon binding to the microRNA target. The activated hairpin initiates a HCR cascade leading to fluorescence signal generation and amplification. Reproduced with permission from Gong et al., 2019. Published by The Royal Society of Chemistry.

Nevertheless, PS-modified strand displacement systems have been employed in living cells with some success. In the same study discussed above (Groves et al., 2016), Seelig et al. showed that their PS-modified four-way branch migration design, which had slow reaction kinetics in vitro, actually outperformed its unmodified DNA counterpart in living cells. This was attributed to the increased stability of the PS modification against nuclease degradation. The authors further demonstrated AND and OR logic operations using variations of their four-way branch migration design (Figure 2b). In this case, PS linkages were introduced into reaction components already constructed from 2′-OMe RNA (discussed in detail below). While the combined effects of the PS and 2′-OMe modifications were essential for proper intracellular operation of the OR gate, the PS modification was dispensable for the AND gate. This observation highlights the unpredictable relationship between the structure of reaction components and their chemical modification, and further underscores the importance of design optimization, potentially on a case-by-case basis, when incorporating PS.

In a more recent example, the Wang group utilized PS-modified DNA to construct a multi-step strand displacement logic cascade capable of simultaneously analyzing multiple endogenous microRNAs in living cells (Figure 2c) (Gong et al., 2019). The device consists of a set of caged initiator hairpins, that upon binding to a microRNA input, self-assemble into an active form. This activated initiator then serves as the trigger for a hybridization chain reaction (HCR) cascades leading to signal generation and amplification. Using this approach, the authors realized several binary logic operations, including OR, AND, INHIBIT, and XOR, in response to various endogenous miRNA initiators, providing a valuable proof-of-concept for future diagnostic applications. Importantly, this work demonstrates the compatibility of PS modifications with several common strand displacement operations, including associative toehold activation (Chen, 2012) and signal amplification (Dirks & Pierce, 2004). Together, these promising examples provide motivation to further investigate the use of PS modifications in the design and construction of intracellular strand displacement devices.

2.2. Locked Nucleic Acids

LNAs contain a bicyclic sugar ring that has the 2’-oxygen and the 4’-carbon atoms of ribose linked via a methylene bridge. In addition to imparting strong nuclease resistance, the added steric strain of the methylene bridge “locks” the ribose sugar in the C3′-endo conformation (Obika et al., 1997), thereby reducing the entropic price paid during Watson–Crick base-pairing. As a result, LNA modifications greatly increase the strength of ON hybridization. For example, the melting temperature of a DNA duplex can increase by as much as 10°C for every LNA nucleotide added (McTigue et al., 2004). The added thermostability of LNA has a number of advantages in the context of strand displacement. Incorporation of LNA modifications, for example near the terminal ends of a duplex, can significantly suppress “leak” (i.e. the spurious activation of the strand displacement cascade in the absence of the initiator strand) by reducing fraying frequency and thus the probability of invasion (Olson et al., 2017). Moreover, the greater thermodynamic penalty for mismatches with LNA nucleotides can increase the specificity of the reaction, which has proven useful in the development of strand displacement probes for detection of single nucleotides polymorphisms (SNPs) (Gao et al., 2014; Zhang et al., 2014). However, the position and number of LNA modifications can impact strand displacement kinetics in unforeseen ways, often reducing the rate of the intended reaction (Olson et al., 2017). Single-stranded reaction components containing LNA are also more susceptible to self-complementary interactions than DNA due to their increased binding affinity. This may result in the formation of unintended secondary structures that can impede performance. Thus, when employing LNA modifications within strand displacement systems, researchers must determine an optimal balance between these various factors, which may be specific for the application in mind.

Despite the advantageous properties of LNA discussed above, especially as they pertain to intracellular applications, we are aware of only a single study employing LNA in a strand displacement system in living cells. In this work, Tan and colleagues developed a hairpin DNA cascade amplifier (HDCA) for the imaging of mRNA expression levels in living cells (Figure 3) (Wu et al., 2015). Their design is based on a catalytic hairpin assembly (CHA) cascade (Yin et al., 2008), which can be catalytically triggered by the mRNA target. In turn, the activated CHA complex displaces the reporter duplex and activates fluorescence. In this way, a single mRNA is able to yield multiple signal outputs. Importantly, to improve the nuclease resistance and thermostability of the system, thereby reducing leak, several LNA nucleotides were incorporated into the reporter duplex. Bolstered by the LNA, the HDCA was capable of monitoring low expression levels of oncogenic mRNA in living cancer cells. On the basis of this result, and the lack of additional examples, it is clear that LNA remains a major untapped resource for the development of robust intracellular strand displacement devices.

Figure 3.

Schematic illustration of the hairpin DNA cascade amplifier (HDCA). The reporter complex was stabilized by incorporation of LNAs. Reproduced with permission from Wu et al., 2015. Copyright 2015 American Chemical Society.

2.3. 2′-O-Methyl Modifications

The 2′-OH position on ribose is a common site for chemical modifications, which include 2′-OMe, 2′-O-methoxyethyl and 2′-fluoro (Roberts et al., 2020). In the context of strand displacement, 2′-OMe has been the most widely used of these modifications. Despite its natural occurrence in tRNAs (Torres et al., 2014), 2′-OMe affords high nuclease resistance, especially towards single-stranded RNases and to a lesser extent to DNases (Lennox & Behlke, 2010; Schneider et al., 2011). Like LNA above, the 2'-OMe modification increases the thermostability of hybridization, which in turn leads to enhanced discrimination between matched and mismatched targets (Majlessi et al., 1998). These effects are most pronounced for RNA duplexes due to the preference of 2′-OMe-modified ribose sugars to adopt a C3′-endo conformation. Hydrophobic interactions of the methyl group have also been shown to contribute to the enhanced thermostability of fully 2′-OMe RNA (Lubini et al., 1994). 2′-OMe-modified ONs also exhibit faster hybridization kinetics than their unmodified counterparts, allowing for more efficient binding to double-stranded regions of structured RNA molecules (Majlessi et al., 1998). Overall, the increased nuclease resistance, enhanced specificity, faster kinetics of hybridization, and ability to bind structured RNAs make 2′-OMe an ideal choice for the development of intracellular strand displacement systems, and in particular, those targeting RNA. Furthermore, 2′-OMe ribonucleotides are more efficiently incorporated into synthetic ONs than LNA, which likely contributes to its preferred use (Threlfall et al., 2012; You et al., 2006).

As discussed above, the Seelig group previously used 2′-OMe RNA to construct a strand displacement system based on 4-way branch migration (Figure 2a,b) (Groves et al., 2016). To date, this remains the most comprehensive study on the utility of 2'-OMe modifications for intracellular applications of strand displacement. By carefully characterizing the delivery and subcellular localization of reaction components, they showed that 2'-OMe RNA duplexes are readily internalized by lipid-based transfection agents, with distribution across the nucleus, cytoplasm and endosome. One important result to emerge from this study is that the efficient operation of DNA strand displacement devices is highly dependent on the transfection method, and specifically, the ability to co-localize reaction components in cells. Using optimized delivery conditions, Seelig and colleagues carried out a series of interesting tasks in living cells using reaction systems constructed from 2′-OMe RNA. Importantly, they showed that strand displacement reactions could be successfully interfaced with different biological pathways. For example, the 4-way branch migration design was exploited to yield an active siRNA following the reaction, leading to efficient gene knockdown in living cells (Figure 4a). We note that optimal performance required both 2′-OMe and PS modifications, again demonstrating the collective advantages of multiple modifications. Overall, as a result of this study, 2′-OMe modifications emerged as a reliable material for construction of strand displacement devices that can operate within and be interfaced with living systems.

Figure 4.

Intracellular strand displacement systems involving 2′-OMe modifications. (a) A four way strand exchange reaction designed to generate an active siRNA duplex in living cells, leading to gene silencing. Reproduced with permission from Groves et al., 2016. Copyright Springer Nature. (b) Strand displacement probe for imaging mRNA in living cells. Upon electroporation into cells, the probe binds the target mRNA resulting in displacement of the quencher strand. Co-localization of multiple probes on the same mRNA allows single molecule-level imaging. Reproduced with permission from Chatterjee et al., 2018. Copyright 2018 American Chemical Society.

Building on this work, the Seelig Group designed a strand displacement probe for imaging and tracking endogenously expressed mRNA at a single molecule level in cells (Chatterjee et al., 2018). The probe was constructed entirely from 2′-OMe RNA and contained two functional domains responsible for RNA sensing and control of localization (Figure 4b). The interaction domain binds to the mRNA target and releases the quencher strand through strand displacement. The extension domain permits Exportin-5-mediated nuclear export, and was essential for localization of the probe to the cytoplasm. This observation highlights the ability of strand displacement probes to interact with cellular proteins (discussed in detail below), and the potential for such interactions to be exploited. Using this probe, the authors visualized individual mRNA molecules carrying 96 repeats of the target sequence, and most excitingly, tracked the movement of several different mRNAs simultaneously in living cells. This work further expands the functional repertoire of strand displacement probes constructed from 2′-OMe RNA, and lays the foundation for implementing more sophisticated strand displacement devices in living cells.

3. PEPTIDE NUCLEIC ACIDS

Rationally designed as a DNA mimic, PNA comprises a peptide-like backbone composed of N-(2-aminoethyl)-glycine units, with the canonical bases coupled to the glycine nitrogen via a methylene carbonyl linkage (Table 1) (Nielsen et al., 1991). PNA binds efficiently with DNA, RNA, and PNA following standard WC base pairing rules (Egholm et al., 1993; Wittung et al., 1994). Furthermore, the pseudo-peptide backbone is highly resistant to nucleases, proteases and peptidases (Demidov et al., 1994). The uncharged backbone also reduces electrostatic repulsion between PNA and complementary DNA/RNA strands. As a result, the thermostability of PNA-DNA and PNA-RNA duplex is greater compared to DNA-DNA and DNA-RNA duplexes (Brown et al., 1994; Egholm et al., 1992; Schwarz et al., 1999). Along with tighter binding comes increased specificity, as a single mismatch in PNA-DNA duplexes is generally more destabilizing than the same mismatch in an all-DNA duplex (i.e. greater ΔTm). On the basis of these properties, PNA has enabled important applications such as antisense agents, biosensing, and gene editing (Brandén, 2000; Ray & Nordén, 2000; Saarbach et al., 2019; Shakeel et al., 2006; Singh et al., 2020; Wang & Xu, 2004).

By extension, these same properties are highly favourable in the context of intracellular strand displacement, with several additional benefits. For example, the increased thermostability of PNA duplexes is expected to suppress leak reactions. Moreover, a neutral backbone means that ionic strength has little effect on the stability of PNA hybrids (Tomac et al., 1996). Thus, PNA-based strand displacement systems may be inherently compatible with diverse biological environments with less optimization. PNA also has the unique ability to invade DNA duplexes and structured DNA and RNAs (Datta & Armitage, 2001; Dias et al., 2002; Marin & Armitage, 2005), potentially allowing PNA-based strand displacement devices, and in particular short PNA toeholds, to access structured sequence spaces inaccessible to analogous systems constructed of traditional modifications.

Nevertheless, use of PNA in the construction of strand displacement systems does involve several design challenges. For example, the increased thermodynamic stability of PNA hybrids has been shown to reduce the rate of strand displacement reactions relative to corresponding all-DNA systems (Hsieh et al., 2018). Caution also needs to be taken to avoid self-complementary sequences that can form restrictive secondary structures, potentially limiting sequence space. Purine rich sequences also need to be avoided as they have a tendency to drive aggregation, thus leading to solubility issues (Braasch & Corey, 2001). We note, however, that functionalization of PNA by non-glycine lipophilic amino acids can improve solubility and certain cationic amino acid modifications enhance cellular internalization (Shiraishi & Nielsen, 2014). Given the tremendous success of PNA as antisense agents and hybridization probes (Egholm et. al., 1992; Nielsen 2000; Pellestor et.al., 2004), and its emerging applications in DNA nanotechnology, it is clear that the favourable features of PNA outweigh potential design challenges.

One property not yet considered is stereochemistry. While PNA itself is achiral, chirality can be induced in PNA by means of functionalization at either the α-position or the γ-position (Table 1). In particular, modifications at the γ-position strongly induce either right-handed or left-handed helicity in single-stranded PNA in a manner that is dependent on the configuration of the stereogenic center and the nature of the side chain (Dragulescu-Andrasi et al., 2006; Sforza et al., 2007). This preorganization induced by γ-modifications can have dramatic effects on the stability and sequence specificity of PNA hybridization. Notably, γ-PNAs synthesized from l-amino acids (l-γ-PNAS) strongly induce right-handedness in single-stranded PNAs (Dragulescu-Andrasi et al., 2006). As a result, l-γ-PNA has higher affinity and selectivity towards native nucleic acid targets compared to unmodified, achiral PNA, and favours double-strand invasion (De et al., 2013; Dragulescu-Andrasi et al., 2006; He et al., 2009; Rapireddy et al., 2007). Again, these are highly desirable properties for strand displacement systems designed to detect and analyze intracellular nucleic acids. Interestingly, the Ly group recently showed that right-handed l-γ-PNAS, as well as native DNA and RNA, are unable to hybridize with left-handed d-γ-PNAs due to conformational mismatch (Sacui et al., 2015; Yeh et al., 2010). However, each of the polymers hybridize to unmodified PNA, allowing the sequence information in each polymer to be interconverted through strand displacement (Hsieh et al., 2018; Sacui et al., 2015). This recognition orthogonality has already led to expanded functionality in strand displacement systems (Chang et al., 2017), and from an intracellular perspective, should enable construction of dynamic PNA-based devices with minimal off-target binding.

Several studies have begun to show the promise of PNA-based strand displacement systems for applications in living cells and organisms. The Taylor group showed that a simple chimeric PNA-DNA strand displacement probe (Figure 5a), wherein the PNA strand contained a fluorophore and the DNA strand a quencher, could be used to detect mRNA expression with high sensitivity and specificity in living cells (Wang et al., 2012). The DNA strand (and its negatively charged backbone) was used to facilitate binding and delivery of the probe into cells via cationic nanoparticles. By replacing the fluorophore/quencher pair with 123I-radiolabelled PNA strand, the same probe design was used to detect mRNA overexpression in mice (Shen et al., 2013). A similar strategy was used to develop a binary FRET probe, again for imaging mRNA (Figure 5a, bottom) (Wang et al., 2013). In this case, the probe consisted of a pair of PNA-DNA duplexes that targeted two sites in close proximity on the same mRNA molecule. One PNA strand was labelled with a donor and the other with an acceptor dye such that binding of the probes to their corresponding sites on the target RNA, and subsequent displacement of the DNA strand, resulted in a detectable FRET signal.

Figure 5.

Intracellular strand displacement systems involving PNA. (a) Schematic representation of the nanoparticle-mediated delivery of PNA strand displacement probes for imaging mRNA. Top: A quenched PNA-DNA duplex is electrostatically bound to the cationic nanoparticle and delivered into the cell. Upon entry and endosomal escape, binding of the PNA toehold to the target mRNA facilitates strand displacement of the quencher strand. Bottom: A pair of PNA-DNA FRET probes are delivered as above. Binding of each PNA toehold to the target mRNA facilitates strand displacement of the DNA strand. A FRET signal is observed only if both the donor and acceptor probes bind the mRNA. (b) Photocleavable PNA probe for gene knockdown in zebrafish. Photolysis-induced cleavage of the photocleavable linker (PL) enables the probe to efficiently bind its target mRNA, resulting in displacement of the blocking strand and arrest of protein synthesis by the PNA strand. Reproduced with permission from Tang et al., 2007. Copyright 2007 American Chemical Society. (c) PNA tagging of proteins (cell surface receptors in this case) provides a platform for recruitment of DNA strands for reversible fluorescent labelling by toehold-mediated strand displacement. Reproduced with permission from Gavins et al., 2021. Copyright Springer Nature.

In addition to imaging applications, the Dmochowski group showed that PNA-based strand displacement probes could be used to downregulate gene expression in live zebrafish embryos (Tang et al., 2007). They developed a “caged” probe consisting of a negatively charged PNA (ncPNA) antisense strand covalently bound to complementary strand of 2’-OMe RNA via a flexible photocleavable linker (Figure 5b). Only after cleavage of the linker by UV irradiation could efficient binding of the ncPNA strand to the mRNA target and subsequent displacement of 2’-OMe RNA blocking strand occur. As expected, microinjection of the caged PNA antisense probe in zebrafish embryos resulted in knockdown of the target mRNAs only after UV irradiation. This work demonstrates how optical activation of strand displacement devices, when coupled with prolonged in vivo stability of a modified oligonucleotide, provides a powerful approach for spatiotemporal control over biological systems.

In a more recent example (Gavins et al., 2021), the Seitz group reported a strategy for reversibly labelling protein in living cells using PNA tags (Figure 5c). Both the PNA tag and the protein of interest are labelled with a short peptide tag that facilitates their binding through a coiled coil interaction. The close proximity of the two tags results in the covalent attachment of the PNA to the protein via a native chemical ligation-type reaction. Once installed, the biostable PNA tag was interfaced with components of several dynamic DNA assemblies through programmable hybridization. Most notably, reversible labelling of PNA conjugated proteins with fluorescent DNA strands was achieved by way of toehold-mediated strand displacement (Figure 5c). Using this approach, high resolution imaging of protein internalization and trafficking was accomplished. By providing a straightforward route to interface proteins with dynamic DNA devices on and within living cells, this work offers intriguing applications ranging from advanced bioimaging to programmable protein assembly, which is made possible by the unique properties of PNA.

4. MIRROR IMAGE OLIGONUCLEOTIDES: l-DNA AND l-RNA

L-DNA and L-RNA, which consist of l-(deoxy)ribose sugar units, represent a unique class of modified ONs, as they are enantiomers of the native polymers. Due to the stereospecific nature of biology, whereby proteins evolved to recognize d-nucleic acids, l-ONs are highly resistant to nuclease degradation, nontoxic, and have very low immunological potential (Ashley, 1992; Hauser et al., 2006; Urata et al., 1992; Vater & Klussmann, 2015; Wlotzka et al., 2002). Due to these bio-orthogonal properties, l-ONs have been used in a number of promising biomedical applications, including the development of l-aptamers (Kabza & Sczepanski, 2017; Klußmann et al., 1996; Nolte et al., 1996; Sczepanski & Joyce, 2013, 2015), microarrays (Hauser et al., 2006) and live cell imaging (Zhong & Sczepanski, 2019). The broader applications of l-ONs have been reviewed previously (Eulberg & Klussmann, 2003; Vater & Klussmann, 2003, 2015; Young et al., 2019).

In addition to their bio-orthogonal properties, use of l-DNA/RNA in the construction of strand displacement systems has two distinct advantages compared to the other modifications discussed above. First, l-ONs have identical properties in terms of duplex thermostability and hybridization kinetics compared to their native counterparts (Ashley, 1992; Urata et al., 1992). Consequently, well-established principles for designing strand displacement reaction cascades can be directly applied to l-DNA without further optimization. This includes the use of powerful design algorithms, like NuPACK and MS-DSD, which are currently incompatible with the other chemical modifications discussed above (Lakin et al., 2011; Zadeh et al., 2011). Second, l-ONs are incapable of forming contiguous WC base-pairs with D-ONs (Garbesi et al., 1993; Hoehlig et al., 2015; Szabat et al., 2016). Thus, strand displacement devices which employ l-ONs are expected to operate more effectively in cellular environments without collateral off-target hybridization with endogenous nucleic acids.

While the inability of l-ONs to bind their native counterparts can reduce off-target effects, it also precludes intentional, sequence-specific binding to a nucleic acid target of interest. One of the most powerful applications of intracellular strand displacement technologies is the sequence-specific detection and analysis of endogenous nucleic acids, such as mRNAs and miRNAs (Chandrasekaran et al., 2019; Chatterjee et al., 2018; Chen et al., 2015; Groves et al., 2016; Tang et al., 2007; S. Wang et al., 2019). Thus, for such applications, it is critical that l-ONs be capable of interacting with endogenous nucleic acids in a sequence-specific manner when intended. In line with this goal, two novel strategies have been recently developed which enable the transfer of sequence information between ONs of opposite stereochemistry. The first strategy takes advantage of PNA (Figure 6a), which as discussed above, has no inherent chirality. As a result, PNA hybridizes equally well to both enantiomers of DNA and RNA (Hoehlig et al., 2015; Kabza et al., 2017). On this basis, PNA can be used to sequence-specifically interface ON enantiomers through toehold-mediated strand displacement (Figure 6a). A typical “heterochiral” reaction involves a PNA-DNA or PNA-RNA heteroduplex containing a toehold on the achiral PNA strand (domain t*). This allows an invading strand (input) of one chirality (via domain t) to bind the toehold and displace the incumbent strand of the opposite chirality (output). In this way, d-nucleic acid biomarkers can be sequence-specifically interfaced with a robust nanodevice composed of bio-orthogonal l-DNA/RNA. For example, this approach has already been used to interface microRNAs with l-DNA-based logic circuits and catalytic amplifiers in vitro (Kabza & Sczepanski, 2020; Kabza et al., 2017).

Figure 6.

Strategies to sequence-specifically interface d- and l-oligonucleotides. (a) Heterochiral strand displacement using PNA-DNA heteroduplexes. (b) Heterochiral strand displacement using a single chimeric d/l-DNA duplex. (c) Heterochiral strand displacement cascade using multiple chimeric d/l-DNA duplexes. In this scheme, nuclease degradation of the d-DNA portions of duplexes T1 and T2 will not result in the spurious release of the l-DNA output, thereby avoiding reaction leak. Reproduced with permission from Mallette et al. 2020. Copyright 2020 American Chemical Society.

The second strategy for sequence-specifically interfacing d- and l-ONS relies on a chimeric duplex (d/l-A) composed of a D-DNA domain (domain 1/1*) directly linked to a l-DNA domain (domain a/a*) (Figure 6b) (Young & Sczepanski, 2019). The d-DNA domain contains a toehold (domain t*) that can be bound by a d-DNA/RNA invader (input), resulting in displacement of the incumbent strand up to the d-DNA/l-DNA junction. At this point, the relatively short l-DNA portion (domain a/a*) is destabilized due to reduced base pairing and spontaneously dissociates from the complex. The released incumbent strand, and specifically the l-DNA domain a, can now proceed to interact with downstream reaction components composed of l-DNA. The d-DNA portion of duplex d/l-A was found to be susceptible to degradation by nucleases, which resulted in unintentional release of the incumbent l-DNA strand (i.e. leak). However, replacement of the d-DNA portion of the chimeric duplex with 2′-OMe ribonucleotides greatly increased the stability of the complex, and when coupled to a downstream l-DNA fluorescent reporter module, enabled detection of microRNAs in serum (Young & Sczepanski, 2019). We note that the increased thermodynamic stability of 2′-OMe ribonucleotides required that the D-portion of the chimeric duplex be redesigned in order to obtain efficient reaction kinetics. This result further emphasizes challenges associated with incorporation of modified nucleotides in previously established designs. More recently, the Lakin group reported a strategy to overcome leak due to degradation of the d-DNA portion of chimera without the need for additional modifications (Figure 6c) (Mallette et al., 2020). Their design involves a strand displacement cascade between two chimeric duplexes (T1 and T2), such that the d-DNA invader strand (Input) triggers the release of the l-DNA output only if the d-DNA portions of T1 and T2 remain intact. This work also demonstrates that strand displacement reactions will occur across d-DNA/l-DNA junctions.

Heterochiral strand displacement reactions provide a direct route to interface living systems with bio-orthogonal l-DNA/RNA-based circuits and other nanodevices. Based on the properties discussed above, use of l-DNA/RNA is expected to improve the intracellular performance, reliability, and utility of such devices compared to traditional approaches. To test this directly, we recently compared d-DNA and l-DNA strand displacement reactions in living cells (Zhong & Sczepanski, 2021). Both d-DNA and l-DNA versions of a reporter duplex (d-R and l-R) modified with a fluorophore and quencher on complementary strands were transfected into living cells (Figure 7a). Whereas the d-reporter was rapidly degraded upon transfection, resulting in strong fluorescence signal (i.e. leak), the l-reporter remained intact within cells for up to 10 hours. Consequently, upon initiation of strand displacement using the corresponding invading strand (Input), the l-DNA reaction had dramatically improved signal-to-noise ratios compared to d-DNA reaction (Figure 7a). Most importantly, we showed that a heterochiral strand displacement cascade, which interfaced a d-DNA input strand (d-IN) with the l-reporter, outperformed a similar cascade composed solely of DNA, both in terms of leak and signal gain (Figure 7b). We note that this experiment employed a photocaged input strand (d-IN), which ensured that the reaction occurred in cells and allowed for precise monitoring of intracellular kinetics upon UV activation. This photocaging approach is discussed in detail below, and represents a convenient strategy for testing (and comparing) the intracellular performance of strand displacement systems composed of other chemical modifications in the future. Taken together, this work clearly demonstrates that strand displacement reaction systems constructed from l-DNA have superior intracellular stability and functionality compared to their native counterparts, and confirms the practicality of heterochiral strand displacement for interfacing endogenous D-nucleic acids with l-DNA/RNA-based circuits and other devices.

Figure 7.

Intracellular strand displacement systems involving l-DNA/RNA. (a) Schematic illustration of d-DNA and l-DNA reporter complexes (d/l-R) (left) and their activation by specific and non-specific pathways in cells (right). (b) Schematic illustration of the strand displacement cascade (left). Components for both the l-DNA (heterochiral) and d-DNA reaction cascades were transfected into cells and the reaction initiated by UV treatment. Fluorescence was monitored by flow cytometry in the absence and presence of UV (right). Panels (a) and (b) were reproduced with permission from Zhong & Sczepanski, 2021. Copyright 2021 American Chemical Society. (c) A fluorescent l-RNA biosensor for imaging microRNA in living cells. Reproduced with permission from Zhong & Sczepanski, 2019. Copyright 2019 American Chemical Society.

Indeed, we have used the heterochiral approach to develop a fluorescent l-RNA biosensor for imaging microRNAs in living cells (Figure 7c) (Zhong & Sczepanski, 2019). The sensor is based on the l-RNA version of the fluorogenic aptamer Mango III (Autour et al., 2018). The folded aptamer binds a derivative of thiazole orange (TO) resulting in strong fluorescence activation. Because the dye is achiral, both d- and l-versions of Mango III behave identically, facilitating this work. Fluorescence of the sensor is initially quenched due to hybridization of a PNA blocking strand to l-Mango III, which prevents proper folding of the aptamer and dye binding. Activation of the sensor is achieved through heterochiral strand displacement of the PNA blocking strand from the L-aptamer by a d-microRNA target of interest. As expected, the sensor was found to be resistant to nuclease degradation, allowing for detection of microRNAs in serum. Importantly, using a self-delivering version of the l-Mango sensor, we were able to image overexpression of microRNA-155 in living human cells (Figure 7c). This study not only demonstrates that l-ONS can be effectively interfaced with endogenous nucleic acids, it also provides a starting point for interfacing more complex l-DNA/RNA-based strand displacement nanodevices with living cells and organisms for exciting biomedical application in the future.

5. NUCLEOBASE MODIFICATIONS

Compared to sugar and backbone ON modifications, nucleobase modifications are far less common in the context of strand displacement, especially in living cells. Nevertheless, nucleobase modifications, and in particular photocaging groups, warrant a brief discussion due to their unique capabilities. The Deiters group showed that installation of a 6-nitropiperonyloxymethylene (NPOM) group on thymidine nucleotides allows for photochemical activation of DNA strand displacement cascades (Figure 8) (Prokup et al., 2012; Young & Deiters, 2006). The sterically demanding NPOM caging group in conjunction with the disruption of Watson–Crick base pairing prevents hybridization of the input strand (INhv) with the cognate toehold domain (t*) on complex A (Figure 8). The NPOM caging group(s) can be rapidly removed from INhv upon irradiation with UV light, effectively activating DNA strand displacement. Importantly, the Deiters group demonstrated that this approach allows for light to be used as an input for DNA-based computations in living cells, which they argue lays the foundation for development of DNA-based computation devices with unprecedented spatial and temporal resolution (Hemphill & Deiters, 2013). Indeed, as discussed above (Figure 7b), we exploited the temporal control offered by this caging strategy to measure the intracellular kinetics of d-DNA and l-DNA strand displacement reactions (Zhong & Sczepanski, 2021). Finally, while not a nucleobase modification, it is worth mentioning here that 2′-O-nitrobenzyl adenosine has also been used to achieve controlled activation of a DNAzyme-based strand displacement cascade in living cells (Wu et al., 2017).

Figure 8.

Overview of the photocaging strategy for light-mediated activation of DNA strand displacement reactions.

6. FUTURE OUTLOOK AND PERSPECTIVES

It is clear from the scarcity of examples that in vivo applications of strand displacements is still a field in its infancy. As this technology continues to advance, and implementation of DNA strand displacement devices in cells become more routine, we have no doubt that chemically modified nucleotides will play a major role. Nevertheless, even with the potential advantages offered by chemical modifications, major challenges remain. We discuss these challenges below and explore potential solutions that pave the way towards the broader adoption of modified nucleotides in the field of intracellular DNA nanotechnology.

6.1. Cellular delivery and intracellular localization

Owing to their negatively charged backbones, ONs are incapable of penetrating the phospholipid bilayer (Roberts et al., 2020). Consequently, efficient cellular internalization of ONs typically requires carriers such as lipid-based transfection reagents or conjugation with cell penetrating peptides (CPPs) or other internalizing ligands (Chen et al., 2015; Roberts et al., 2020). These delivery methods, however, can result in uneven cellular uptake and distribution. Moreover, once delivered into cells, achieving a homogeneous subcellular distribution is difficult. This is perhaps best exemplified by lipid-based transfection reagents, which despite efficient cellular uptake, result in the majority of internalized ON being trapped within endosomes. Together, these issues represent a major challenge in the context of DNA strand displacement systems, including those constructed from modified ONs, where optimal performance requires the intracellular co-localization of multiple reaction components at specific concentration ratios. Indeed, Seelig et al. showed that efficient operation of chemically modified strand displacement cascades is highly dependent on subcellular co-localization of the corresponding reaction components (Groves et al., 2016).

There are several potential avenues that can be explored in order to overcome the challenges discussed above. To begin, it will be important to characterize how different chemical modifications, in conjunction with common design parameters such as ON length, sequence and structure, influence cellular uptake and distribution. By focusing on a specific delivery method, such as lipid-based transfection reagents, these studies could produce optimized protocols for delivering the most common strand displacement components into workhorse laboratory cell lines. Success in this regard will facilitate some of the most promising biomedical applications of strand displacement devices, for example, the detection and analysis of endogenous nucleic acids. In addition to optimized delivery strategies, physically tethering or encapsulating stoichiometric amounts of reaction components to or inside a molecular scaffold, such as DNA nanostructures, could be used to ensure intracellular co-localization (Roberts et al., 2020). Indeed, therapeutic ONs, strand displacement reaction components, and multi-enzyme cascades have all been successfully tethered to DNA nanostructures to improve functionality (Bujold et al., 2016; Fu et al., 2014; Lee et al., 2012; Wu et al., 2020). Another advantage of using DNA nanostructures is their inherent ability to be internalized by cells (Walsh et al., 2011), potentially circumventing the need for other delivery reagents. Interestingly, tethering chemically modified reaction components to a less stable scaffold (i.e. one comprised of canonical DNA or RNA) could allow for their release into solution following degradation of the scaffold, thereby overcoming potential complications associated with the reactivity of spatially immobilized components (Jin et al., 2018; Young & Sczepanski, 2019) Unique delivery strategies such as this, which exploit differences in cellular half-lives, further highlight the potential advantages of using chemically modified ONs in the construction of strand displacement systems and devices.

6.2. Kinetic and thermodynamics characterization

As discussed above, the thermodynamic and kinetic properties of chemically modified ONs can differ dramatically from their native counterparts. To date, however, these differences remain poorly characterized, making it challenging to predict how strand displacement systems constructed using modified nucleotides will behave (Groves et al., 2016). This knowledge gap potentially undermines other advantages of using modifications. Thus, moving forward, it will be imperative that researchers more thoroughly characterize how specific chemical modifications, including the extent of modification and their position(s), influence duplex thermostability and hybridization kinetics, especially in the context of strand displacement reactions. In particular, these studies must address how modified nucleotides impact common design parameters for kinetic control, such as toehold length and mismatches(Olson et al., 2017). These data could be used to develop new predictive models and/or be integrated into current algorithms, such as NuPack (Zadeh et al., 2011), oxDNA (Šulc et al., 2012) and Multistrand (Schaeffer et al., 2015), allowing for more accurate computation of free energy changes and other crucial parameters needed to reliably design and analyse multicomponent strand displacement systems containing modified nucleotides. More accurate models will in turn reduce the need for iterative optimization experiments, which are both time-consuming and costly, thereby greatly accelerating the development of complex intracellular reaction systems.

In addition to in vitro parameterization, it is also essential that we understand how intracellular environments impact DNA strand displacement reactions. Indeed, reaction conditions unique to the cell, including temperature, salts, and molecular crowding, have each been shown to influence the thermodynamics and kinetics of nucleic acid hybridization. While salt and temperature effects on strand displacement have been thoroughly characterized in vitro, and can be predictably incorporated into kinetic models (Srinivas et al., 2013; Zhang & Winfree, 2009), crowding effects remain poorly understood, due in part to the challenge of replicating the crowded cellular environment in a test tube. Nevertheless, recent experimental and theoretical studies have revealed the potential impact of molecular crowding on strand displacement reactions, showing that crowded environments can increase duplex thermostability and accelerate hybridization kinetics (Chen et al., 2019; Hong et al., 2020; Schoen et al., 2009). Given the complex nature of the macromolecular interactions inside the cell, however, in vitro observations are likely insufficient to fully describe intracellular strand displacement behaviors. Instead, we stress that future characterization studies must be carried out directly in cells. To this end, a number of elegant methods for measuring strand displacement kinetics within living cells and animals have been reported (Wu et al., 2020; Zhong & Sczepanski, 2021). We expect that the improved intracellular stability of chemically modified ONs will greatly facilitate such studies in the future, leading to a more robust set of design parameters for engineering intracellular DNA-based devices.

6.3. Off-target effects

Due to their reliance on WC base pairing, every nucleic acid analogue (L-ONs being a potential exception) is susceptible to off-target hybridization with the abundance of endogenous nucleic acids. The sequence space represented in the human genome (and transcriptome) contains hundreds of near-perfect complementary sequences capable of strong WC base-pairing with the individual components of strand displacement systems. For example, a 14-mer oligonucleotide is expected to have nearly 1000 complementary sequences with maximum 3 base-pair differences present within the human genome. Consequently, even with the added biostability afforded by chemically modified nucleotides, strand displacement components having common domain lengths of 10-20 bp are susceptible to off-target hybridization that may result in system leak. While strategies have been developed in vitro for preventing such leak (Genot et al., 2011; Thachuk et al., 2015; B. Wang et al., 2018), they typically require numerous additional reaction components, exponentially increasing the difficulty of utilizing such strategies in living systems. As discussed above, a potential solution to off-target hybridization is the use of l-ONs in the construction of intracellular reaction components, which has been shown to reduce leak both in vitro and in living cells (Kabza et al., 2017; Mallette et al., 2020; Zhong & Sczepanski, 2021).

In addition to off-target hybridization, nucleic acid strand displacement components are also susceptible to unintended interactions with intracellular proteins, which can not only impede device performance but also cause cytotoxicity. Perhaps the most notable example is immunostimulatory effects through the activation of Toll-like receptors (TLR). It is well documented that exogenous nucleic acids, including chemically modified ONs, tend to generate a host immune response upon internalization (Judge et al., 2005; Qiuyan et al., 1999). This can lead to proinflammatory effects that induce apoptosis and cell death. Use of certain modifications, such as LNA, in conjunction with PS can reduce immunostimulatory effects when compared to PS alone for certain applications (Judge et al., 2005). Immunostimulatory effects are also dependent on sequence and position of a modification (Judge et al., 2005; Qiuyan et al., 1999), further highlighting the complexity of off-target effects and the need for further characterization. In addition to immunostimulatory effects, the accumulation of chemically modified ONs can drive interactions with extracellular, cell-surface, and/or intracellular proteins, referred to as “aptameric binding”, resulting in different toxicity manifestations (Frazier, 2015; Quemener et al., 2020). For example, hepatocellular proteins have been shown to bind LNA modified ONs with high affinity, causing liver toxicity in mice (Burdick et al., 2014). Moreover, these effects appear sequence specific. Even l-ONs may not be immune to the effects of non-specific protein binding. A recent study showed that the polycomb repressive complex 2, a promiscuous RNA-binding protein and important epigenetic regulator, can bind l-ONs with high affinity, leading to altered function (Deckard & Sczepanski, 2018).

Fortunately, the field of therapeutic ONs is constantly evolving to address off-target effects by conducting extensive characterization studies on modified ONs (McKenzie et al., 2021; Roberts et al., 2020). We anticipate that these efforts will continue to inform the field of intracellular strand displacement. Nevertheless, moving forward, it will be critical that researchers begin to characterize off-target effects of modified ONs directly in the context of strand displacement, using nucleic acid architectures that are common to this field. Establishment of structure-toxicity relationships could be used to predict toxicity from sequence, structure and/or modification patterns, allowing for potentially toxic motifs to be eliminated at the design stage, thereby reducing development costs and time-consuming design iterations.

6.4. Cost and availability

One aspect that we have not fully addressed is the cost associated with using chemically modified ONs, which is summarized in Table 1. In general, modified ONs are significantly more expensive than their native counterparts, which represents a key practical barrier to their broader adoption in the field. The higher costs associated with modified ONs are most prohibitive for laboratories lacking synthetic expertise and/or the capability to synthesize ONs, as commercial synthesis and purification of modified ONs can cost at least an order of magnitude more than in-house preparation (Table 1). While the current cost may be prohibitive for some, the future outlook is very positive. Increased usage of modified ONs, especially in the ASO field, has continued to drive down prices over the last decade, and we anticipate this trend will continue. As an example, the average cost of a single gram of L-DNA phosphoramidite has fallen approximately 75% in the last 5 years based on our own quoted prices.

In addition to lower prices, we expect that future advances in protein engineering will broaden accessibility of chemically modified strand displacement components by allowing them to be prepared enzymatically in the laboratory. Enzymatic synthesis will reduce the reliance on costly commercial production and/or the need for specialized skills and equipment. Towards this goal, polymerase-mediated synthesis of several modified ON has already been demonstrated, including several of the modifications discussed herein (Mei et al., 2021; Pinheiro et al., 2012; Taylor et al., 2015). Remarkably, several groups have reported the complete chemical synthesis of d-amino acid polymerases and successfully demonstrated PCR amplification and transcription of l-DNA and l-RNA, respectively (Jiang et al., 2017; Wang et al., 2019). It is also worth noting that enzymatic polymerization is orders of magnitude faster and more accurate than chemical synthesis and, importantly, does not impose length restrictions on the reaction components. Therefore, as the ability to prepare modified ONs enzymatically becomes more routine, we not only expect broader adoption of modified nucleotides in strand displacement reaction systems, but also an expansion of the types of strand displacement architectures and behaviors that can be achieved.

7. Conclusions

It is clear that many of the most exciting applications of nucleic acid strand displacement lie at the interface with biology. From differentiating cell types to manipulating genetic information, there are endless opportunities in research and medicine. However, if the true potential of strand displacement devices is to be realized, researchers must continue to prioritize the development and characterization of more robust, biocompatible nucleic acid components, while simultaneously building a better understanding of how these systems behave in and interact with living systems. Given the advantages offered by chemically modified nucleotides, they will undoubtedly continue to be at the forefront of this effort. Indeed, the past ten years have seen promising strides to integrate modified nucleotides with strand displacement technologies that operate in living cells and organisms, as well as other harsh biological environments not discussed here (Hochrein et. al.,2018; Larkey et. al.,2014;Fern & Schulman, 2017) As the field continues to grow, it is unlikely that a single chemical modification will dominate. Rather, we expect multiple modifications to be advanced in parallel, such as l-DNA and PNA, and as we have seen, used combinatorially to achieve novel functionality and performance tailored for specific intracellular applications.

Finally, while this review focuses on more common chemical modifications, this discussion remains incomplete without the mention of “xeno” nucleic acids (or XNAS). XNAS are an emerging class of modified ONs based on five or six-membered congeners of the canonical (deoxy)ribose sugar in DNA and RNA. The utility of these modifications lies in the progress made in engineered enzyme polymerases that enable the exchange of genetic information between the canonical DNA and XNA, which has facilitated a number of exciting applications (Mei et al., 2021; Pinheiro et al., 2012). For example, several groups have reported the in vitro selection of XNA-based aptamers and catalysts (Dunn et al., 2020; Taylor et al., 2015; Y. Wang et al., 2018). Importantly, many XNAs share similar advantages with the chemical modifications discussed above, including resistance to nuclease degradation. Therefore, the compatibility of XNAs with enzymatic, DNA templated synthesis may open the door to genetically encodable strand displacement systems and devices that are both highly robust and bioorthogonal. Moreover, novel chemical modifications offer the promise of expanded functionality that could lead to new types of programmable, dynamic behaviors. While only time will tell if XNAs represent the next generation material for constructing intracellular DNA nanotechnology, we believe the integration of XNAs (and other emerging polymers) with dynamic DNA nanotechnology represents an area ripe for future exploration.

Funding Information

This work was supported by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (R35GM124974) and the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering (R21EB027855) at the National Institutes of Health. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. This work was also supported by the National Science Foundation (2003534). J.T.S is a CPRIT Scholar of Cancer Research supported by the Cancer Prevention and Research Institute of Texas (RR150038).

Footnotes

No conflict of interest to declare

References

- Aartsma-Rus A, van Vliet L, Hirschi M, Janson AAM, Heemskerk H, de Winter CL, de Kimpe S, van Deutekom JCT, t Hoen PAC, & van Ommen G-JB (2009). Guidelines for antisense oligonucleotide design and insight into splice-modulating mechanisms. Molecular therapy : the Journal of the American Society of Gene Therapy, 17(3), 548–553. 10.1038/mt.2008.205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashley GW (1992). Modeling, synthesis, and hybridization properties of (L)-ribonucleic acid. Journal of the American Chemical Society, 114(25), 9731–9736. 10.1021/ja00051a001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Autour A, C. Y. Jeng S, D. Cawte A, Abdolahzadeh A, Galli A, Panchapakesan SSS, Rueda D, Ryckelynck M, & Unrau PJ (2018). Fluorogenic RNA Mango aptamers for imaging small non-coding RNAs in mammalian cells. Nature Communications, 9(1), 656. 10.1038/s41467-018-02993-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartok E, & Hartmann G (2020). Immune Sensing Mechanisms that Discriminate Self from Altered Self and Foreign Nucleic Acids. Immunity, 53(1), 54–77. 10.1016/j.immuni.2020.06.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bath J, & Turberfield AJ (2007). DNA nanomachines. Nature Nanotechnology, 2(5), 275–284. 10.1038/nnano.2007.104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braasch DA, & Corey DR (2001). Synthesis, analysis, purification, and intracellular delivery of peptide nucleic acids. Methods, 23(2), 97–107. 10.1006/meth.2000.1111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bramsen JB, Laursen MB, Nielsen AF, Hansen TB, Bus C, Langkjær N, Babu BR, Højland T, Abramov M, Van Aerschot A, Odadzic D, Smicius R, Haas J, Andree C, Barman J, Wenska M, Srivastava P, Zhou C, Honcharenko D, Hess S, Müller E, Bobkov GV, Mikhailov SN, Fava E, Meyer TF, Chattopadhyaya J, Zerial M, Engels JW, Herdewijn P, Wengel J, & Kjems J (2009). A large-scale chemical modification screen identifies design rules to generate siRNAs with high activity, high stability and low toxicity. Nucleic Acids Research, 37(9), 2867–2881. 10.1093/nar/gkp106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandén L (2000). PNA: a universal tool in molecular biology: Peptide Nucleic Acids: Protocols and Applications edited by P.E. Nielsen and M. Egholm. Trends in Biotechnology, 18(8), 361. 10.1016/S0167-7799(00)01460-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bratu DP, Cha B-J, Mhlanga MM, Kramer FR, & Tyagi S (2003). Visualizing the distribution and transport of mRNAs in living cells. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 100(23), 13308–13313 10.1073/pnas.2233244100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown SC, Thomson SA, Veal JM, & Davis DG (1994). NMR solution structure of a peptide nucleic acid complexed with RNA. Science, 265(5173), 777–780. 10.1126/science.7519361 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bujold KE, Hsu JCC, & Sleiman HF (2016). Optimized DNA “Nanosuitcases” for Encapsulation and Conditional Release of siRNA. Journal of the American Chemical Society, 138(42), 14030–14038. 10.1021/jacs.6b08369 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bujold KE, Lacroix A, & Sleiman HF (2018). DNA Nanostructures at the Interface with Biology. Chem, 4(3), 495–521. 10.1016/j.chempr.2018.02.005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Burdick AD, Sciabola S, Mantena SR, Hollingshead BD, Stanton R, Warneke JA, Zeng M, Martsen E, Medvedev A, Makarov SS, Reed LA, Davis JW II, & Whiteley LO (2014). Sequence motifs associated with hepatotoxicity of locked nucleic acid—modified antisense oligonucleotides. Nucleic Acids Research, 42(8), 4882–4891. 10.1093/nar/gku142 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chakraborty K, Veetil AT, Jaffrey SR, & Krishnan Y (2016). Nucleic Acid–Based Nanodevices in Biological Imaging. Annual Review of Biochemistry, 85(1), 349–373. 10.1146/annurev-biochem-060815-014244 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandrasekaran AR (2021). Nuclease resistance of DNA nanostructures. Nature Reviews Chemistry, 5(4), 225–239. 10.1038/s41570-021-00251-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandrasekaran AR, Punnoose JA, Zhou L, Dey P, Dey BK, & Halvorsen K (2019). DNA nanotechnology approaches for microRNA detection and diagnosis. Nucleic Acids Research, 47(20), 10489–10505. 10.1093/nar/gkz580 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang D, Lindberg E, & Winssinger N (2017). Critical Analysis of Rate Constants and Turnover Frequency in Nucleic Acid-Templated Reactions: Reaching Terminal Velocity. Journal of the American Chemical Society, 139(4), 1444–1447. 10.1021/jacs.6b12764 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chatterjee G, Chen Y-J, & Seelig G (2018). Nucleic Acid Strand Displacement with Synthetic mRNA Inputs in Living Mammalian Cells. ACS Synthetic Biology, 7(12), 2737–2741. 10.1021/acssynbio.8b00288 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J, & Seeman NC (1991). Synthesis from DNA of a molecule with the connectivity of a cube. Nature, 350(6319), 631–633. 10.1038/350631a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X (2012). Expanding the Rule Set of DNA Circuitry with Associative Toehold Activation. Journal of the American Chemical Society, 134(1), 263–271. 10.1021/ja206690a [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y-I, Chang Y-J, Nguyen TD, Liu C, Phillion S, Kuo Y-A, Vu HT, Liu A, Liu Y-L, Hong S, Ren P, Yankeelov TE, & Yeh H-C (2019). Measuring DNA Hybridization Kinetics in Live Cells Using a Time-Resolved 3D Single-Molecule Tracking Method. Journal of the American Chemical Society, 141(40), 15747–15750. 10.1021/jacs.9b08036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y-J, Groves B, Muscat RA, & Seelig G (2015). DNA nanotechnology from the test tube to the cell. Nature Nanotechnology, 10(9), 748–760. 10.1038/nnano.2015.195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crooke ST, Vickers TA, & Liang X.-h. (2020). Phosphorothioate modified oligonucleotide–protein interactions. Nucleic acids research, 48(10), 5235–5253. 10.1093/nar/gkaa299 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crooke ST, Wang S, Vickers TA, Shen W, & Liang X.-h. (2017). Cellular uptake and trafficking of antisense oligonucleotides. Nature Biotechnology, 35(3), 230–237. 10.1038/nbt.3779 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dar SA, Thakur A, Qureshi A, & Kumar M (2016). siRNAmod: A database of experimentally validated chemically modified siRNAs. Scientific Reports, 6(1), 20031. 10.1038/srep20031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Datta B, & Armitage BA (2001). Hybridization of PNA to Structured DNA Targets: Quadruplex Invasion and the Overhang Effect. Journal of the American Chemical Society, 123(39), 9612–9619. 10.1021/ja016204c [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De A, Souchelnytskyi S, van den Berg A, & Carlen ET (2013). Peptide Nucleic Acid (PNA)–DNA Duplexes: Comparison of Hybridization Affinity between Vertically and Horizontally Tethered PNA Probes. ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces, 5(11), 4607–4612. 10.1021/am4011429 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deckard CE, & Sczepanski JT (2018). Polycomb repressive complex 2 binds RNA irrespective of stereochemistry. Chemical Communications, 54(85), 12061–12064. 10.1039/C8CC07433J [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeLuca M, Shi Z, Castro CE, & Arya G (2020). Dynamic DNA nanotechnology: toward functional nanoscale devices. Nanoscale Horizons, 5(2), 182–201. 10.1039/C9NH00529C [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Demidov VV, Potaman VN, Frank-Kamenetskil MD, Egholm M, Buchard O, Sönnichsen SH, & Nielsen PE (1994). Stability of peptide nucleic acids in human serum and cellular extracts. Biochemical Pharmacology, 48(6), 1310–1313. 10.1016/0006-2952(94)90171-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dias N, Sénamaud-Beaufort C, Forestier El E, Auvin C, Hélène C, & Ester Saison-Behmoaras T (2002). RNA hairpin invasion and ribosome elongation arrest by mixed base PNA oligomer. Journal of Molecular Biology, 320(3), 489–501. 10.1016/s0022-2836(02)00474-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dirks RM, & Pierce NA (2004). Triggered amplification by hybridization chain reaction. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 101(43), 15275–15278. 10.1073/pnas.0407024101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Douglas SM, Bachelet I, & Church GM (2012). A Logic-Gated Nanorobot for Targeted Transport of Molecular Payloads. Science, 335(6070), 831–834. 10.1126/science.1214081 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dragulescu-Andrasi A, Rapireddy S, Frezza BM, Gayathri C, Gil RR, & Ly DH (2006). A Simple γ-Backbone Modification Preorganizes Peptide Nucleic Acid into a Helical Structure. Journal of the American Chemical Society, 128(31), 10258–10267. 10.1021/ja0625576 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn MR, McCloskey CM, Buckley P, Rhea K, & Chaput JC (2020). Generating Biologically Stable TNA Aptamers that Function with High Affinity and Thermal Stability. Journal of the American Chemical Society, 142(17), 7721–7724. 10.1021/jacs.0c00641 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eckstein F (2014). Phosphorothioates, Essential Components of Therapeutic Oligonucleotides. Nucleic Acid Therapeutics, 24(6), 374–387. 10.1089/nat.2014.0506 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egholm M, Buchardt O, Christensen L, Behrens C, Freier SM, Driver DA, Berg RH, Kim SK, Norden B, & Nielsen PE (1993). PNA hybridizes to complementary oligonucleotides obeying the Watson–Crick hydrogen-bonding rules. Nature, 365(6446), 566–568. 10.1038/365566a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egholm M, Buchardt O, Nielsen PE, & Berg RH (1992). Peptide nucleic acids (PNA). Oligonucleotide analogs with an achiral peptide backbone. Journal of the American Chemical Society, 114(5), 1895–1897. 10.1021/ja00031a062 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- ElHefnawi M, Hassan N, Kamar M, Siam R, Remoli AL, El-Azab I, AlAidy O, Marsili G, & Sgarbanti M (2011). The design of optimal therapeutic small interfering RNA molecules targeting diverse strains of influenza A virus. Bioinformatics, 27(24), 3364–3370. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr555 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eulberg D, & Klussmann S (2003). Spiegelmers: Biostable Aptamers. ChemBioChem, 4(10), 979–983. 10.1002/cbic.200300663 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fakhr E, Zare F, & Teimoori-Toolabi L (2016). Precise and efficient siRNA design: a key point in competent gene silencing. Cancer Gene Therapy, 23(4), 73–82. 10.1038/cgt.2016.4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fern J,& Schulman R (2017) Design and Characterization of DNA Strand-Displacement Circuits in Serum-Supplemented Cell Medium. ACS Synthetic Biology, 6(9), 1774–1783. 10.1021/acssynbio.7b00105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher TL, Terhorst T, Cao X, & Wagner RW (1993). Intracellular disposition and metabolism of fluorescently-labeled unmodified and modified oligonucleotides microinjected into mammalian cells. Nucleic Acids Research, 21(16), 3857–3865. 10.1093/nar/21.16.3857 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frazier KS (2015). Antisense oligonucleotide therapies: the promise and the challenges from a toxicologic pathologist's perspective. Toxicologic Pathology, 43(1), 78–89. 10.1177/0192623314551840 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu J, Yang YR, Johnson-Buck A, Liu M, Liu Y, Walter NG, Woodbury NW, & Yan H (2014). Multi-enzyme complexes on DNA scaffolds capable of substrate channelling with an artificial swinging arm. Nature Nanotechnology, 9(7), 531–536. 10.1038/nnano.2014.100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao ZF, Ling Y, Lu L, Chen NY, Luo HQ, & Li NB (2014). Detection of single-nucleotide polymorphisms using an ON-OFF switching of regenerated biosensor based on a locked nucleic acid-integrated and toehold-mediated strand displacement reaction. Analytical Chemistry, 86(5), 2543–2548. 10.1021/ac500362z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garbesi A, Capobianco ML, Colonna FP, Tondelli L, Arcamone F, Manzini G, Hilbers CW, Aelen JME, & Blommers MJJ (1993). L-DNAs as potential antimessenger oligonucleotides: a reassessment. Nucleic Acids Research, 21, 4159–4165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gavins GC, Gröger K, Bartoschek MD, Wolf P, Beck-Sickinger AG, Bultmann S, & Seitz O (2021). Live cell PNA labelling enables erasable fluorescence imaging of membrane proteins. Nature Chemistry, 13(1), 15–23. 10.1038/s41557-020-00584-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Genot AJ, Zhang DY, Bath J, & Turberfield AJ (2011). Remote Toehold: A Mechanism for Flexible Control of DNA Hybridization Kinetics. Journal of the American Chemical Society, 133(7), 2177–2182. 10.1021/ja1073239 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong X, Wei J, Liu J, Li R, Liu X, & Wang F (2019). Programmable intracellular DNA biocomputing circuits for reliable cell recognitions. Chemical Science, 10(10), 2989–2997. 10.1039/C8SC05217D [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman RP, Heilemann M, Doose S, Erben CM, Kapanidis AN, & Turberfield AJ (2008). Reconfigurable, braced, three-dimensional DNA nanostructures. Nature Nanotechnology, 3(2), 93–96. 10.1038/nnano.2008.3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groves B, Chen Y-J, Zurla C, Pochekailov S, Kirschman JL, Santangelo PJ, & Seelig G (2016). Computing in mammalian cells with nucleic acid strand exchange. Nature Nanotechnology, 11(3), 287–294. 10.1038/nnano.2015.278 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagedorn PH, Persson R, Funder ED, Albæk N, Diemer SL, Hansen DJ, Møller MR, Papargyri N, Christiansen H, Hansen BR, Hansen HF, Jensen MA, & Koch T (2018). Locked nucleic acid: modality, diversity, and drug discovery. Drug Discovery Today, 23(1), 101–114. 10.1016/j.drudis.2017.09.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hauser NC, Martinez R, Jacob A, Rupp S, Hoheisel JD, & Matysiak S (2006). Utilising the left-helical conformation of L-DNA for analysing different marker types on a single universal microarray platform. Nucleic Acids Research, 34(18), 5101–5111. 10.1093/nar/gkl671 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He G, Rapireddy S, Bahal R, Sahu B, & Ly DH (2009). Strand Invasion of Extended, Mixed-Sequence B-DNA by γPNAS. Journal of the American Chemical Society, 131(34), 12088–12090. 10.1021/ja900228j [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hemphill J, & Deiters A (2013). DNA Computation in Mammalian Cells: MicroRNA Logic Operations. Journal of the American Chemical Society, 135(28), 10512–10518. 10.1021/ja404350s [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hochrein LM, Tianjia GJ, Schwarzkopf M, & Pierce NA (2018). Signal Transduction in Human Cell Lysate via Dynamic RNA Nanotechnology. ACS Synthetic Biology, 7(12), 2796–2802. 10.1021/acssynbio.8b00424 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoehlig K, Bethge L, & Klussmann S (2015). Stereospecificity of Oligonucleotide Interactions Revisited: No Evidence for Heterochiral Hybridization and Ribozyme/DNAzyme Activity. PLoS One, 10(2), e0115328. 10.1371/journal.pone.0115328 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]