Abstract

Objectives

The COVID-19 pandemic and associated ‘lockdown’ confinement restrictions have resulted in multiple challenges for those living with eating disorders. This qualitative study aimed to examine the lived, psychosocial experiences of individuals with anorexia nervosa from within COVID-19 ‘lockdown’ confinement.

Methods

Audio-recorded semi -structured interviews were conducted online during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic during confinement with a purposive sample of 12 participants who identified as having Anorexia Nervosa. Interviews were transcribed and anonymous data analysed using Thematic Analysis (Braun & Clarke, 2006).

Results

Three key themes with six contributory subthemes were identified. Key themes were: loss of control,supportduring confinement, and time of reflection on recovery. Theme content varied according to stage of recovery and current clinical management. Availability of ‘safe’ foods, increases in compensatory exercise and symptomology, and enhanced opportunities for “secrecy” were described.

Conclusions

These findings provide a unique insight for a vulnerable group from within COVID-19 confinement. The data demonstrated that the impact for individuals with anorexia nervosa has been broadly negative, and participants voiced concerns over the long-term effects of the pandemic on their recovery. The findings highlight the risks of tele-health support and an important role for health professionals in enhancing targeted support during, and after confinement.

Keywords: Anorexia nervosa, Eating disorders, Qualitative research, COVID-19

1. Introduction

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) was a global pandemic and as of June 2021, the global number of COVID-19 cases stands at over 178 million (World Health Organisation, 2021). Due to the significant medical complications, death rates and rapid international spread, restrictive measures were adopted in affected countries to help reduce transmission. These measures have included strict travel restrictions, confinement, closures of health services and non-essential shops and health care, hereby forcing a significant change in people's lives. Early studies have reported lower levels of reported wellbeing and increased rates of anxiety and depression globally (Fernando-Fernandez et al., 2020; Marshall, Bibby, & Abbs, 2020), with the negative psychological effects of social isolation associated with risk of significant psychological distress including post-traumatic stress symptomology reported among young people (Brooks et al., 2020). As the COVID-19 pandemic continues to unfold the overall consequences of the pandemic on mental and physical health remains unknown.

Anorexia Nervosa (AN) is a debilitating psychiatric illness which impacts an individual's physical and psychological health (Bulik, Reba, Siega-Riz, & Reichborn-Kjennerud, 2005). It is characterised by food restriction, intense fear of weight gain, physical emaciation, and disturbances in how body shape and weight is experienced (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). It is presumable that groups categorised as at high risk of mental health concerns such as those diagnosed with AN, may be at increased during COVID19 for a number of reasons. From a theoretical perspective experiences of loss/lack of control such as those experienced during the pandemic are likely to increase eating concerns and related compensatory behaviour (Fairburn, Shafran, & Cooper, 1999). Moreover, these are likely to be further impacted by unique risks which are secondary to that of the pandemic itself (Bulik et al., 2020). Indeed, initial data has shown that more than one in three individuals with an eating disorder (ED) report an increase in ED symptomology with those with AN most affected (Baenas et al., 2020; Fernando-Fernandez et al., 2020). Eating disorder charities have also reported an unprecedented demand for support. Individuals with an ED may be at increased risks, physically; from lowered immune systems in AN, and electrolyte disturbances in bulimia nervosa (Dall-Grave, 2020), and psychologically; with a high vulnerability to, and prevalence of, psychiatric comorbidity - most commonly anxiety and depression (Udo & Grilo, 2019).

The potential impact of the pandemic for people with AN is likely to be multi-factorial. Firstly, emotional stress and anxiety can in itself trigger or worsen ED symptomology (Rodgers et al., 2020) and the uncertainty surrounding the pandemic is likely to increase distress for people with ED (Gordon & Katzman, 2020). Furthermore, specific concerns about transmission may exacerbate health related anxieties and/or COVID-19 contamination related obsessive-compulsive disorder (“coronophobia”; Davis et al., 2020). Potentially exacerbating anxieties further for people with ED is the closure of gyms and leisure facilities which provide an important source of anxiety and psychological symptom management for many (Fietz, Touyz, & Hay, 2014). Increased time spent on social media may also be triggering or reinforce appearance related concerns (Holland & Tiggemann, 2016). Even the increase in use of video calls during the pandemic has been associated with increased anxieties in ED populations (Fernandez-Aranda et al., 2020).

The pandemic restrictions have also disrupted the way in which ED services have been delivered and as a result specialist support has been harder to access (Bulik et al., 2020; Weissman, Bauer, & Thomas 2020) hereby increasing risks, reducing clinical monitoring and patient engagement (Holmes et al., 2020; Weissman, Bauer, & Thomas, 2020), and increasing patient concerns regarding their treatment (Fernandez-Aranda et al., 2020). Similarly, restrictions of face-to face contact has impacted the availability of social support from family and friends which is often central to emotional wellbeing (Saltzman, Hansel, & Bordnick, 2020) and recovery (Lock et al., 2010a, 2010b). For some, the restrictions will have resulted in enforced and prolonged ‘confinement’ with family members with whom relationships may already be strained or problematic, which in turn could exacerbate existing tensions or conflict (Davis, Shuster, Blackmore, & Fox, 2004). Finally, the complex relationship which exists between people with ED and food is likely to have been exacerbated by the availability of specific or preferred (so called “safe” foods; defined as foods that an individual feels safe eating and/or are less likely to trigger guilt or ED symptomology) which may in turn contribute to stockpiling, binging and/or be used to legitimise food restriction (Touyz, Lacey, & Hay, 2020; Weissman, Bauer, & Thomas, 2020).

The precarious nature of recovery from AN, and the high mortality rates (Eddy et al., 2017) are a pressing area of concern. Managing the associated high rates of medical and psychiatric complications, including self-harm and suicide, associated with AN typically requires regular face-to-face clinical review; something which has been compromised during the COVID-19 pandemic (Walsh & Nicholas, 2020). As such, the challenges of accessing/providing support, coupled with the multifactorial vulnerabilities and risks for people with AN are significant. Given the rapid and recent onset of the COVID-19 pandemic there are currently very few empirical studies and those which have been done have tended to focus on surveys of symptomology to evaluate changes in symptoms (Fernandez-Aranda et al., 2020; Phillipou et al., 2020). There is a need to understand the experiences of people with ED's not least to examine the barriers to treatment and support in order that they be promptly addressed (Schlegel et al., 2020). Touyz et al. (2020) point to an urgent need to gather clinical case histories, patient testimonies and empirical data to expedite our understanding of the implications of COVID-19 for this population. This study aims to go some way to addressing this need.

The present study involved a thematic analysis (see Braun & Clarke, 2006) of the psychosocial experience of people living with AN during ‘confinement’ in the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic. The aim was to gather detailed understandings of their experience of ‘confinement’, and the interrelations between their experience, the emotional consequences, impacts upon symptomology and coping responses. It provides a unique insight from a representative sample from within the context being studied (i.e. ‘confinement’ restrictions). Building on early research (Brown et al., 2020; Brown et al., 2020; Fernando-Fernandez et al., 2020; Termorshuizen et al., 2020) this qualitative study aims to provide a rich and insightful account of the experiences and concerns of people living with AN during confinement in the COVID-19 pandemic. The inductive qualitative approach adopted enables the exploration of this novel and evolving life experience independent of theoretical positioning.

2. Method

2.1. Participants

To meet the study criteria, participants had to be over 18 years of age, speak English fluently, and identified as having AN. A purposive sample of twelve participants (11 female, 1 male) took part in the study. Ages ranged from 21 to 63 years (mean 31.8), and duration of ED ranged from approximately 2-44 years (mean 15.5). Participants for the study were located in the UK, Greece and United States of America and at the time of interview were all in ‘lockdown’ confinement (see Table 1 ). (NB. Eighteen individuals made contact willing to participate and were provided with information sheets, with six dropping out before completing the consent form). Confinement guidelines between countries were largely the same at the time of interview; people were required to work from home, remain at home and leave the home only for exercise/essential shopping and only for a short/defined period of time. Greece was the only minor exception in which approval from the police was required to leave the home. The decision to stop recruitment was informed by contemplating data saturation (Mason, 2010) and the indication that this can typically be achieved in a homogenous sample size of twelve in thematic analysis (Ando, Cousins, & Young, 2014; Braun & Clarke, 2019).

Table 1.

Participant information.

| Participant | Age | Gender | Country | Approximate Duration of ED | Presentation AN:Anorexia Nervosa BN: Bulimia Nervosa | Isolation Details |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 21 | Female | Greece | 8 years | AN & BN | With family |

| 2 | 63 | Female | UK | 29 years | AN | On their own |

| 3 | 26 | Female | UK | 3 years | AN | With their partner |

| 4 | 58 | Female | UK | 44 years | AN | With their partner |

| 5 | 29 | Female | UK | 18 years | AN | On their own |

| 6 | 23 | Female | USA | 11 years | BN | With their partner |

| 7 | 27 | Female | UK | 12 years | AN | With family |

| 8 | 27 | Female | UK | 2 years | AN | With their partner |

| 9 | 30 | Female | UK | 17 years | AN | On their own |

| 10 | 29 | Female | UK | 17 years | AN | With their partner |

| 11 | 23 | Male | UK | 12 years | AN | On their own |

| 12 | 26 | Female | Guernsey | 13 years | AN | On their own |

2.2. Procedure

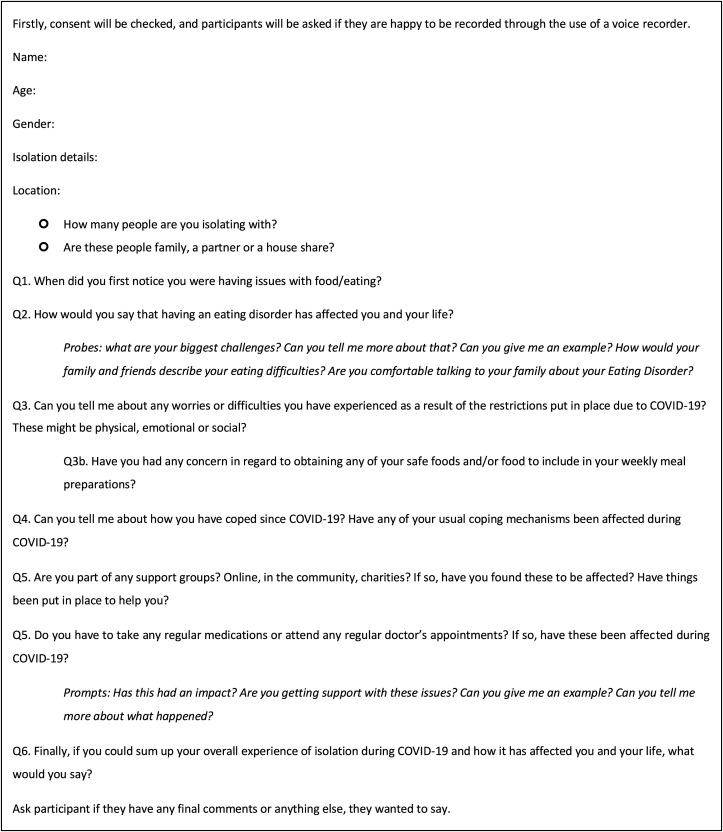

Approval was granted by the academic University Psychology Department (ref: 4876). Recruitment of participants occurred through advertising on social media and a national ED support charity (BEAT Eating Disorders Charity, UK) between April 17, 2020 and May 21, 2020. Interested individuals were sent a participation information sheet before giving written consent to participation and the interview being audio-recorded. This study employed semi-structured interviews in a qualitative design. The semi-structured interview schedule comprised six open-ended questions exploring participants experiences (see Fig. 1 ). Interviews were conducted over the internet using video call software (e.g. Skype, Face Time etc) and took place at a time convenient to the participant, and in a private location which ensured privacy and confidentiality. Interviews lasted between 15 and 32 min. Following the interview all participants were offered a debrief session should they feel it was required (though none took up this offer) and information for specialist support services.

Fig. 1.

Interview schedule.

2.3. Context of current study

Participants were recruited between April 17, 2020 and May 21, 2020 during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic. At the time of interview all participants were in ‘confinement’ and under restrictions including restrictions on leaving the house, non-essential shops and health care services being closed etc.). All participants were either studying or working from home.

2.4. Data analysis

Data was analysed using the six-step thematic analysis process described by Braun and Clarke (2006) which is a flexible qualitative method that enables a rich and detailed account of experience to be accessed. Thematic analysis is a useful research tool in exploring the quality of life in health conditions (e.g. Nicolson & Anderson, 2003). Initial thoughts and ideas were noted down and transcribed data were repeatedly read, and recordings were listened to several times to ensure accuracy and ‘data immersion’ (Braun & Clarke, 2006). The next stage of analysis involved manual coding: identifying and generating initial codes and textual units for interesting features/patterns in the data relating to the topic being studied. In terms of refining and developing the initial set of themes, a saliency analysis approach (Buetow, 2010) was adopted; this approach assesses the degree to which codes repeat, is identified as highly important or both. Analysis then refocussed at the broader level of themes, and different codes were used to label the potential themes, with relevant data extracts (‘quotes’) identified. The same unit of text could be included in more than one category. Coding and theme extraction were completed by the first author, with themes checked back to raw data by second author. To ensure rigour the data were validated and systematically reviewed by the second author to ensure that a name, definition, and an exhaustive set of data supported each category. Gradually overarching themes and subthemes were identified which were corroborated through discussion and final systematic checks back to the verbatim data. To encourage reflexivity and reduce bias during the process the lead researcher kept a reflective journal throughout the research process (Snowden, 2015).

3. Results

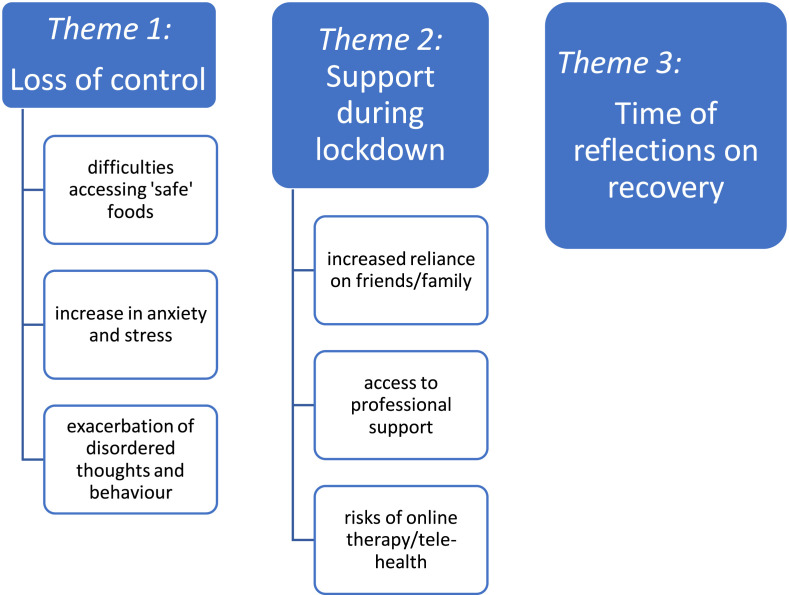

Thematic analysis of interview transcripts identified three major themes and six contributory subthemes (see Fig. 2 ). Supporting verbatim quotes are presented for the theme with the participant number and the page/line number where the quote may be found in the raw data presented after each quote.

Fig. 2.

Themes and subthemes.

3.1. Theme 1: Loss of control

Participants described a sense of being out of control triggered by the pandemic and the associated restrictions. Participants felt a loss of control relating to areas through which they managed their anxieties, but also their eating behaviour/s. Most commonly mentioned were anxieties about gaining what participants described as ‘safe foods’, exercising, impact of loss of routine, and exacerbation of disordered thoughts and behaviours.

3.1.1. Difficulties accessing ‘safe’ foods

Most participants described distressing difficulties in buying their ‘safe’ foods with one describing obtaining this as “impossible, absolutely impossible” P5, (P5, 843). These difficulties were a source of considerable anxiety for many and one described how “the idea of not getting those foods is hugely distressing” (P3, 536) and could trigger a “meltdown” (P2, 94). The challenges of obtaining their preferred or ‘safe’ food/s made the experience of shopping stressful and aversive, and many would simply go without food:

“it's crazy as I can't go to every shop to find what I need to find so forget it, I will go without”. (P5, 848–849)

“if I'm not able to get what is on my meal plan from the supermarket then I wouldn't get anything at all”. (P12, 2269–2270)

Before the pandemic, if unable to obtain safe foods they would have searched elsewhere but ‘confinement’ restrictions prohibited this safety behaviour and as a result, participants felt distressed and out of control. One participant described how letting other people do shopping for them as “the biggest thing I had to adjust to” (p12, 2277). Indeed, support from family and friends was not always able to moderate these anxieties:

“my boyfriend had offered to go for us and do the shoppping for us but then you're battling the idea of someone else choosing your food for you so that's quite difficult”. (P3, 358–9)

For some these changes to their normal routine, such as shopping alone or buying in bulk was challenging and exacerbated certain AN behaviours and anxieties:

“it's really hard, because finding some of my safe foods is difficult and also substituting my safe foods is difficult too as I label check constantly. And when my husband is with me, he will intervene and just put it in the trolley for me whereas on my own I will stand and read labels for half an hour”. (P4, 712–715).

“problem I faced was when I got home and lay out all the content out, it was just too much to see it all there …. err to actually then process everything we had bought. I had to remove myself from the room and actually do something else whilst my boyfriend packed the food into the cupboards. Whereas out of confinement that would never be an issue for me”. (P3, 539–546)

3.1.2. Increase in anxiety and stress

Confinement restrictions were described as causing increased levels of anxiety and stress. These anxieties were complex however, with many describing the concerns that the pandemic raised for them in terms of recovery, but also the anxieties it raised in regards to ED behaviours:

“It's sort of paradoxical because on one hand I was really anxious realising it was going to stall my progress but then on the other, I was really anxious that it would stall my disordered behaviours, so it's been quite complex”. (P8, 1392–1394)

Managing anxiety was described as “the most difficult [part]” (P4, 763) which for some was overwhelming:

“I just feel as though I'm trapped in a never-ending spinning cycle of anxiety. It's like trying to keep your head above water whilst reeds are wrapping themselves around you and dragging you under, every time you manage to free yourself from one, another wraps around you”. (P9, 1710–1716)

“It's made life extremely difficult and at some points I feel like it's not worth living to be honest, that is what it got to just last week - so it's just made it extremely difficult, extremely challenging and extremely anxiety provoking”. (P5, 978–981)

Most participants described high anxieties relating to loss of routine/s which, for many, was central to maintaining wellbeing and/or recovery:

“a lot of what we have to try and recover from is being … having unhealthy rituals and routines, but a big part of recovery is also having a routine” (P8, 1483–1484)

“my routine has gotten lost, which tampers with my sleep, which in turn tampers with my ability to follow my meal plan” (P 9, 1672–1673)

Notably, many of the participants commented on the reciprocity of the relationship between loss of routine/control and ED pathology, reflecting a deep understanding of the function of the disorder:

“when you feel that out of control, you try and control that, eating”. (P1, 129)

The wider stress of the situation also contributed, and people made clear links between increases in anxiety and exacerbation of ED:

“a trigger for things getting bad with my eating disorder is stress” (P2, 271)

“I was saying to my eating disorder consultant just yesterday, that it’s just ten times worse than it was before I went into hospital because of all this corona virus stuff”. (P5, 957–958)

3.1.3. Exacerbations of negative disordered thoughts and behaviours

Most participants described an exacerbation of negative disordered thoughts. These thoughts were commonly associated with reductions in being monitored by any of their usual support networks or medical team, which reinforced the ‘anorexic voice’ or what were described as ‘disordered thoughts’:

“now I can't get hold of any [safe food] and that's starting to get a little bit nervous -but there is that disordered thought in my heads saying, oh well this is a good thing”. (P8, 1529–1530)

“my anorexia turned that into ‘won't be getting weighed, no-one will know if I lose weight!’ (P9, 1675–1676)

“the eating disorder part of me is whooping with delight if you like, and saying you can do what you like now, nobody is watching you”. (P2,306–315)

An increase in these negative thoughts triggered related disordered behaviours including compensating for the decrease in physical activity, limiting food intake/number of meals, or taking laxative pills. For example, some described having “more of an obsession with exercise” (P 1, 78) during confinement:

“I would say most days I get out to do some form of exercise whether it be a walk or a run or a bike ride or something but yeah I have started to feel quite guilty if I haven't been out and done something whereas I don't think I would have been like that as much before these restrictions”. (P7, 1248–51)

In many ways the changes and restrictions imposed by the pandemic enabled the justification of disordered eating and increases in exercise:

“ever since this COVID, I have every now and then when I eat greasy foods, I start taking some laxative pills”. (P6, 1037–1038)

“not being able to see my family, being limited in exercise […] and being alone with anorexia - finding reasons as to why I don't need to eat”. (P9, 1683,1684)

“I have felt very guilty … [] around not being active enough and the conflicting thoughts around whether food is actually necessary if I'm not burning it off. I guess this has increased my fear around gaining weight, eating too much for what is actually required for life and that I'm not burning calories in the same way, so whether the food is just going to mean I gain fat rather than muscle. This has led to some ‘anorexic’ type choices”. (P9, 1724–1729).

The closure of gyms was particularly challenging for some as exercise served the dual purpose of helping to manage anxiety, as well as being related to weight management:

“realising like oh my god, how am I going to exercise? how am I going to get all my exercise in? that was sort of stressful because not only was that exercise part of … I'm always willing to say it was a big part of my disorder, and it's an ongoing balance - but it was already a big part of managing my anxiety” (P8, 1398–1401).

Interestingly, for some this was exacerbated by friends/family health regimes, or media messaging about keeping fit and exercising: during ‘confinement’

“During the restrictions [].. even in the safe recovery communities [people] are getting sucked into this COVID exercise ‘mania’ and the problem is the government, the NHS [National Health Service], everyone is kind of encouraging all this exercise ‘mania’!” (P8, 1441–1444)

3.2. Theme 2: Support during confinement

The pandemic forced changes in how people accessed support, from both informal (e.g. family and friends) and formal/professional support services. The impact of these changes featured prominently in participant narratives with ‘pitfalls’ and risks for their recovery highlighted:

3.2.1. Increased reliance on family and friends as support networks

There was a widely reported increase in reliance of family and friends for practical support with food shopping and collecting medication/prescriptions. While participants felt gratitude and supported, for many this dependence also triggered complex feelings of guilt; guilt at needing the support, about putting others at risk (of exposure to the virus), and guilt relating to the ‘need’ for food:

“I haven't actually been shopping […] so it's been done by my dad […] which worries me and makes me feel even more guilty about my need for food”. (P8, 1687–1690)

Relatedly, participants did not “want to feel like a burden to people” (P12, 2305–6) and were reluctant to access their usual support networks. As a result their own needs were sometimes minimised or the needs of others prioritised:

“you feel bad because you're just like, everyone is going through this and it's just not you”. (P5, 981,982)

“I'm sort of less willing to do that [seek support] because I don't want to take it away from someone having a crisis”. (P11, 2109–2110)

3.2.2. Accessing services and professional support during COVID-19

The inability to fully access professional services was highlighted as a major concern for those participants receiving professional support prior to the pandemic/confinement. Restrictions and suspension of some services did however lead to the cessation of support groups and personal therapy, and there was widespread uncertainty about therapy/support which was destabilising:

“I'm just never sure when she [therapist] is going to tell me about the session”. (P1, 94)

“but the [care] plan kept changing without communication of the changes”. (P9, 1752)

Participants described an uptake of charity and volunteer services such as BEAT (UK ED charity) during the pandemic, with some “using their [BEAT] online chat more; a lot more” (P5, 896). This increase was described as a reflection of the participants increases in anxiety and ED symptoms, social isolation and the reduction in access to therapy. Furthermore, this was described as observed throughout the wider ED community:

“people are struggling more, binging more than usual and finding support online”. (P1, 185–186)

“there is also more people struggling now and more people that need extra support”. (P10, 1961–1974)

3.2.3. Risks of tele-health

Participants who were receiving ongoing support/therapy had transitioned to tele-health support. A range of experiences were reported with some reporting this to be a lifeline, but many finding it “really difficult” (P7, 1204):

“And there is also my therapist who is amazing. She has been a great help when it comes to everything”. (P1, 84–85)

“There is only so much they can do over the phone”. (P5, 885–886)

The challenges of assessment, clinical monitoring and rapport during quarantine were notable, and arguably could undermine the therapeutic relationship and efficacy:

“I do feel differently when I come out of therapy – at the moment I don't feel anything at the end of a phone call and also like my therapist is very good at reading [me]. I'm quite good at saying what I think she wants to hear but she's really good at reading my facial expressions and over the phone she can't do that so I can say whatever I like really”. (P7, 1220–1223)

Participants found it easier to avoid scrutiny and honesty during these consultations which exacerbated the strength of this ‘secretive’ disorder:

“it's a very secretive disorder and if I'm face to face with someone I can't lie, I can't hide the fact that I've lost weight or hide the fact that I'm drained energy wise, whereas on the phone I can cover up” (P5, 705–707).

3.3. Theme 3: Time of reflection on recovery

The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on participants wellness and recovery was undoubtedly significant. The changes in their support systems and in their routine created anxiety although paradoxically, time spent away from work and daily routines allowed time to reflect on their recovery and put into practice therapeutic learnings. The experience was however, a “mixed bag” (P3, 610) with both positive and negative effects:

“Of course it's very scary and very uncertain and its definitely set me back when it comes to my eating disorder and has disappointed me in a sense that its put me in a place that I had hoped I'd had come away from - but it's also been positive to see a lot of love and care from people around me and support services and just generally really I mean, you can turn on the tv and see a lot of heart-warming stories from this time and there are so many people out there trying to do so many good things”. (P3, 604–610)

There was frustration and concern over the impact this experience would have on their recovery, with notable frustration over how far it had set them back:

“it's put me in a place that I'd hoped I'd come away from”. (P3, 605–606)

“it's definitely brought cracks into my recovery.” (P10, 1889)

However, for some participants the time in confinement provided opportunity, with valuable time and space to positively reflect on their recovery and priorities:

“what we talk about in therapy is about reflection and time to think about where you are at the moment and I never ever have time to do that normally”. (P6, 1308–1309)

“having the space to do that is really good but I definitely did think that I was further along in my recovery than I am, but I guess that is a good thing because it means yeah I guess it is a good thing because it means I am aware of it as well which is helpful” (P10, 1892–1894).

4. Discussion

This study examined the experiences of people with AN during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020. The data reflects individuals' experiences and perceptions, with data gathered from within, and during ‘confinement’, providing a unique insight into their concerns at the time. The findings support those of earlier studies which found increased dependence on families/carers, elevated concerns and compensatory behaviour in relation to exercise and food (Clark Brown et al., 2020), reduced access to services (Termorshuizen et al., 2020; Weissman, Bauer, & Thomas, 2020) and anxieties about loss of routine (Brown et al., 2020). Key themes identified here suggested that the experience of confinement contributed to a sense of loss of control which exacerbated symptomology, the effects of which were further aggravated by reductions in support.

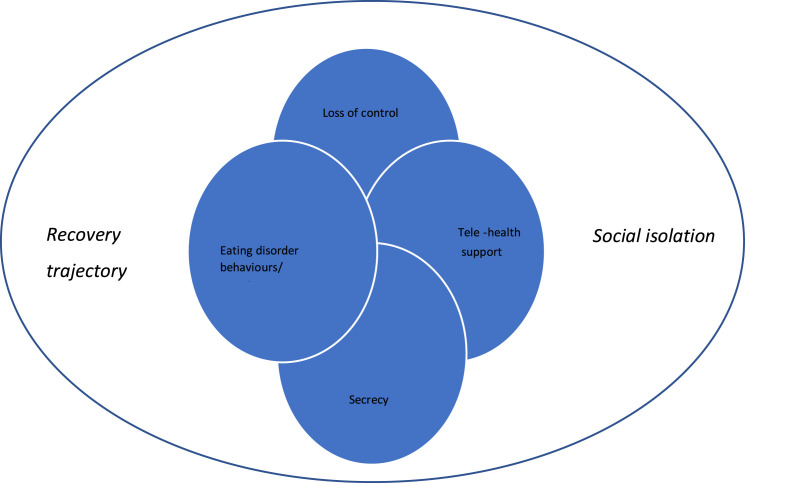

The findings presented here shed light on the challenges faced by people with AN including; disruption of routine, access to preferred/‘safe’ foods, dependence on others for food shopping and limitations around exercise. All of these challenges triggered concerns about a loss of control which exacerbated anxiety, disordered thoughts and eating behaviours. From a theoretical perspective these findings are consistent with cognitive-behavioural explanations, which point to experiences of loss/lack of control as likely to increase eating concerns and related compensatory behaviour (Fairburn et al., 1999). While these elevated levels of symptomology may be expected, given the increased levels of anxiety and depression being reported more generally (Fernando-Fernandez et al., 2020; Marshall et al., 2020) participants here described how this was exacerbated by the barriers to receiving effective support/therapy. Transitions to tele-health support may provide opportunities and exacerbations for what was described by participants as a “secretive” disorder. One health care systems-related factor was the impact of transition to tele-health – in particular, this was not considered effective for clinical management, and/or therapeutic rapport, supporting earlier findings (Fernandez-Aranda et al., 2020; Holmes et al., 2020; Termorshuizen et al., 2020; Weissman, Bauer, & Thomas, 2020). As such, confinement created for some the ‘perfect storm’ in which loss of control triggered exacerbations in ED symptomology which in turn, was worsened by barriers to effective monitoring and support (see Fig. 3 ).

Fig. 3.

A model of individual and social factors influencing participants experiences of AN during COVID19 quarantine.

Fig. 3: A representation of participants experiences during confinement.

Arguably the anxiety and social isolation triggered by the pandemic and subsequent confinement could be said to have focussed individuals more on their vulnerabilities and ‘illness’ identity. The concept of ‘engulfment’ as described by Oris et al. (2018) in relation to an individual's sense of illness identity (Charmaz, 1983) may provide a useful framework from which to examine how a person understands and experiences their illness (Zangi, Hauge, Steen, Finset, & Hagen, 2011). Associated with maladaptive psychological and physical functioning including anxiety and depression (Oris et al., 2018) ‘engulfment’ may focus individuals more on symptoms, hereby generating greater introspection (Lewis, Woods, Hough, & Bensley, 1989), maladaptive coping responses (Oris et al., 2018), and potentially exacerbating feelings of loss of control. Future longitudinal research could examine the evolving impact of illness identity with attention to the role of engulfment. This may point to periods of vulnerability for people with AN and highlight particular timepoints/circumstances where intervention is most essential. In addition, it seems important to consider wider socio-cultural factors which may further exacerbate experiences of engulfment –media focus on keeping fit and exercising during confinement, was one example described by participants here and which warrants further exploration.

A notable theme highlighted in this study was experience of the confinement as a period of reflection. Participants described having the opportunity to reflect on their experience and recovery from AN and for some this provided opportunity to reflect on their progress, challenges that remained, and for others confirmed their resilience. It is however important to note that participants also described how confinement enabled opportunities for increases in compensatory exercise and ‘secrecy’ which reinforced the ED. This may reflect participant's ambivalence (a common feature in AN; Williams & Reid, 2010) which, when coupled with reductions in face-to-face support, may have contributed to deterioration of ED. Indeed, in a divergence from previous literature (Brown et al., 2020) most participants in this study described the disruption as a frustrating setback which highlighted their ongoing struggle with AN, and which they feared might have a long-term negative impact on their recovery.

This study was unique in its findings on the effectiveness of telehealth support services. In comparison to other ealier studies (e.g. Robert, collie, & Danile, 2002) which report on the effectiveness of telehealth, the findings reported here suggest it was largely ineffective in helping relieve participants of worries or concerns they were experiencing as many found that it was much easier for them to withhold information over the phone. Participants rationalised (consciously and/or unconsciously) their secrecy as concern over what professional help would be available to them, and this enabled them to minimise their needs/prioritise the needs of others. Remarkably, many participants showed insightful metacognition, and commented on how the tele-health support facilitated the ‘secrecy’ of the AN – hereby pointing to a significant risk if barriers to face-to-face services remain in the longer term/return. Notably, the majority of participants in this study had tele-health support and were not offered video-call or online support - however it seems highly likely that many of the issues described in this study could occur within an online context also. It is possible that experiencing different types of remote support could result in different experiences and outcomes for individuals, and this requires further study. It is also important to highlight that some participants did report good support from therapists, family and friends and in particular, charitable support services, and were largely sympathetic to the challenge's services faced in providing support. However, the significance of the response of support charities may point to the potential for an effective, collaborative approach (between health care services and support charities) for targeted support to enhance provision during any future confinements.

The findings reported here highlight important health service-related factors worthy of consideration, and which may point to potential opportunities to intervene. Firstly, exacerbation of ED symptomology created by opportunities for secrecy as a result of tele-health support (and/or cessation of support) may need to be discussed specifically when normal care is resumed. Arguably, this may provide useful insights and opportunities to enable planning for future relapses and/or challenges. Relatedly, health professionals may need to re-establish therapeutic rapport in situations where trust has been ruptured or the individual with AN experience's secrecy related guilt and/or ambivalence as described here. Similarly, discussions around ‘setbacks’ and helping patients to verbalise their concerns about the impact of confinement upon their recovery seem essential. As such, within the negative effects of confinement for people with AN may lie therapeutic opportunities to examine fundamental aspects of the ED, and/or re-establish/negotiate therapeutic and service -related factors.

It is important to acknowledge the resilience of the participants who were able to describe and objectively comment on their experiences, with some able to clearly articulate the conflict created by the ‘anorexic voice’. This perhaps sheds some light on the central role their understanding of the ED played in mitigating the negative effects of confinement. Arguably people more engaged with services, or further into their recovery trajectory will have more experience of managing triggers for their ED, and this may help identify those most at risk. Comparisons may usefully be made between patient groups, or with children and young people with ED to consider the moderating and mitigating roles of illness severity, illness trajectory and level of support.

This study is not without its limitations. It has provided a unique snapshot of the experiences of one group of individuals living with AN while in confinement during COVID-19, however studies of this kind are at risk of participation bias. Firstly, we cannot be certain that the participants in this study did not reflect a higher level of distress, or even engagement with the COVID-19 pandemic. This in itself may point to elevated levels of generalized, or health-related anxiety which could have played a contributory role in their experiences. Indeed, studies examining the role of health-related anxiety in AN may be worthwhile. Secondly, participants reported having a diagnosis of AN but this could not be corroborated with medical records. Finally, eleven of the twelve participants in this study were female and studying male experiences of confinement specifically may yield different findings, especially given the reported differences in clinical presentation (Crisp et al., 2006). Future studies could usefully explore the similarities and differences of males and females to help inform service provision. Despite these limitations the findings reported here are consistent with those reported elsewhere (Brown et al., 2020; Termorshuizen et al., 2020; Weissman, Bauer, & Thomas, 2020).

In summary, this study demonstrates that the psychosocial impact of COVID-19 confinement may be significant, and participants are concerned about the long-term repercussions. The isolation, restrictions, and loss of control experienced is creating barriers for effective monitoring and treatment and this may be focussing the individual more closely on their AN. Future research could usefully consider the role of collaborative support with charitable support agencies to enhance/extend the availability of support for individuals with AN during similar periods of isolation and/or confinement. Finding innovative ways vulnerable people can be more effectively risk managed also seems of pressing importance in a post-COVID-19 era. Finally, understanding the potential role of engulfment and identity could provide a useful therapeutic approach to understanding and evaluating patient risk.

Ethical statement

Ethical approval for this study was granted by Swansea University Psychology Department Ethics Committee (reference number: 4876). This committee is part of the College of Health and Human Science.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors state no conflict of interest for this paper.

References

- American Psychiatric Association . American Psychiatric Association; Washington, DC: 2013. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-5. [Google Scholar]

- Ando H., Cousins R., Young C. Achieving saturation in thematic analysis: Development and refinement of a codebook. Comprehensive Psychology. 2014;3 doi: 10.2466/03.CP.3.4. 03-CP. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Baenas I., Caravaca-Sanz E., Granero R., Sánchez I., Riesco N., Testa G., et al. COVID-19 and eating disorders during confinement: Analysis of factors associated with resilience and aggravation of symptoms. European Eating Disorders Review. 2020;23(6):855–863. doi: 10.1002/erv.2771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun V., Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology. 2006;3(2):77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Braun V., Clarke V. Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis. Qualitative research in Sport, Exercise and Health. 2019;11(4):589–597. doi: 10.1080/2159676X.2019.1628806. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks S.K., Webster R.K., Smith L.E., Woodland L., Wessely S., Greenberg N., et al. The psychological impact of confinementconfinement and how to reduce it: Rapid review of the evidence. Lancet. 2020;395(10227):912–920. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30460-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown S., Opitz M.C., Peebles A.I., Sharpe H., Duffy F., Newman E. A qualitative exploration of the impact of COVID-19 on individuals with eating disorders in the UK. Appetite. 2020;156 doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2020.104977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buetow S. Thematic Analysis and It's reconceptualisation as 'saliency analysis'. Journal of Health Services Research and Policy. 2010;15(2):123–125. doi: 10.1258/jhsrp.2009.009081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bulik C., Peat C., Van Further E., Harper L., Macdermod C., Flatt R., Termorshuizen J. MEDrxIV; 2020. Early impact of COVID-19 on individuals with eating disorders: A survey of ~ 1000 individuals in the United States and The Netherlands; pp. 1–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bulik C.M., Reba L., Siega‐Riz A.M., Reichborn‐Kjennerud T. Anorexia nervosa: Definition, epidemiology, and cycle of risk. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2005;37(S1):S2–S9. doi: 10.1002/eat.20107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charmaz K. Loss of self: a fundamental form of suffering in the chronically ill. 5(2), 168-195. Sociology of health & illness, 1983;5(2):168–195. doi: 10.1111/1467-9566.ep10491512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark Bryan D., Macdonald P., Ambwani S., Cardi V., Rowlands K., Willmott D., et al. Exploring the ways in which COVID‐19 and lockdown has affected the lives of adult patients with anorexia nervosa and their carers. European Eating Disorders Review. 2020;28(6):826–835. doi: 10.1002/erv.2762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crisp A., Gowers S., Joughin N., McClelland L., Rooney B., Nielsen S., Hartman D. Anorexia nervosa in males: Similarities and differences to anorexia nervosa in females. European Eating Disorders Review. 2006;14:163–167. doi: 10.1002/erv.703. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dall-Grave R. Coronavirus disease 2019 and eating disorders. 2020. https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/eating-disorders-the-facts/202003/coronavirus-disease-2019-and-eating-disorders March 21, Retrieved from Psychology Today:

- Davis C., Ng K.C., Oh J.Y., Baeg A., Rajasegaran K., Chew C.S.E. Caring for children and adolescents with eating disorders in the current coronavirus 19 pandemic: A Singapore perspective. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2020;67(1):131–134. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2020.03.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis C., Shuster B., Blackmore E., Fox J. Looking good—family focus on appearance and the risk for eating disorders. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2004;35(2):136–144. doi: 10.1002/eat.10250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eddy K.T., Tabri N., Thomas J.J., Murray H.B., Keshaviah A., Hastings E., Keel P.K. Recovery from anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa at 22-year follow-up. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2017;78(2):184–189. doi: 10.4088/JCP.15m10393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fairburn C.G., Shafran R., Cooper Z. A cognitive behavioural theory of anorexia nervosa. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 1999;37:1–13. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(98)00102-8. 1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernández‐Aranda F., Casas M., Claes L., Bryan D.C., Favaro A., Granero R., Treasure J. COVID‐19 and implications for eating disorders. European Eating Disorders Review. 2020;28(3):239. doi: 10.1002/erv.2738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernando-Fernandez A., Casas M., Claes L., Bryan D., Favaro A., Granero R., et al. COVID-19 and implications for eating disorders. European Eating Disorders Review. 2020;28(3):239–245. doi: 10.1002/erv.2738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fietz M., Touyz S., Hay P. A risk profile of compulsive exercise in adolescents with an eating disorder: A systematic review. Advances in Eating Disorders: Theory, Research and Practice. 2014;2(3):241–263. [Google Scholar]

- Gordon C.M., Katzman D.K. Lessons learned in caring for adolescents with eating disorders: The Singapore experience. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2020;67:5–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2020.03.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holland G., Tiggemann M. A systematic review of the impact of the use of social networking sites on body image and disordered eating outcomes. Body Image. 2016;17:100–110. doi: 10.1016/j.bodyim.2016.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes E.A., O'Connor R.C., Perry V.H., Tracey I., Wessely S., Arseneault L., et al. Multidisciplinary research priorities for the COVID‐19 pandemic: A call for action for mental health science. The Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7:547–560. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30168-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis F.M., Woods N.F., Hough E.E., Bensley L.S. The family's functioning with chronic illness in the mother: The spouse's perspective. Social Science & Medicine. 1989;29(11):1261–1269. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(89)90066-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lock J., Le Grange D., Agras W.S., Moye A., Bryson S.W., Jo B. Randomized clinical trial comparing family-based treatment with adolescent-focused individual therapy for adolescents with anorexia nervosa. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2010;67(10):1025–1032. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lock J., Le Grange D., Agras W.S., Moye A., Bryson S.W., Jo B. Randomized clinical trial comparing family-based treatment with adolescent-focused individual therapy foradolescents with anorexia nervosa. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2010;67(10):1025–1032. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall L., Bibby J., Abbs I. The Health Foundation; 2020. Emerging evidence on COVID-19's impact on mental health and health inequalities. [Google Scholar]

- Mason M. Sample size and saturation in PhD studies using qualitative interviews. Forum qualitative Sozialforschung/Forum: Qualitative Social Research. 2010;11(No. 3) August. [Google Scholar]

- Nicolson P., Anderson P. Quality of life, distress and self‐esteem: A focus group study of people with chronic bronchitis. British Journal of Health Psychology. 2003;8(3):251–270. doi: 10.1348/135910703322370842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oris L., Luyckx K., Rassart J., Goubert L., Goossens E., Apers S., Moons P. Illness identity in adults with a chronic illness. Journal of Clinical Psychology in Medical Settings. 2018;25(4):429–440. doi: 10.1007/s10880-018-9552-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillipou A., Meyer D., Neill E., Tan E.J., Toh W.L., Van Rheenen T.E., et al. Eating and exercise behaviors in eating disorders and the general population during the COVID 19 pandemic in Australia: Initial results from the COLLATE project. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2020;53(7):1158–1165. doi: 10.1002/eat.23317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robert R., Collie C., Daniel B. Effectiveness of telephone counseling: A field-based investigation. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2002;49(2):233–242. doi: 10.1037//0022-0167.49.2.233. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rodgers R.F., Lombardo C., Cerolini S., Franko D.L., Omori M., Fuller-Tyszkiewicz M., et al. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on eating disorder risk and symptoms. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2020;53(7):1166–1170. doi: 10.1002/eat.23318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saltzman L.Y., Hansel T.C., Bordnick P.S. Loneliness, isolation, and social support factors in post-COVID-19 mental health. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy. 2020;12(S1):55–57. doi: 10.1037/tra0000703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlegl S., Maier J., Meule A., Voderholzer U. Eating disorders in times of the COVID‐19 pandemic—results from an online survey of patients with anorexia nervosa. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2020;53(11):1791–1800. doi: 10.1002/eat.23374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snowden M. Use of diaries in research. Nursing Standard. 2015;29(44):36–41. doi: 10.7748/ns.29.44.36.e9251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Termorshuizen J.D., Watson H.J., Thornton L.M., Borg S., Flatt R.E., MacDermod C.M., Bulik C.M. Early impact of COVID‐19 on individuals with self‐reported eating disorders: A survey of~ 1,000 individuals in the United States and The Netherlands. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2020;53(11):1780–1790. doi: 10.1002/eat.23353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Touyz S., Lacey H., Hay P. Eating disorders in the time of COVID-19. Journal of eating disorders. 2020;35(2):136–144. doi: 10.1002/eat.10250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Udo T., Grilo C. Psychiatric and medical correlates of DSM-5 eatinf disorders in a nationally representative sample of adults in the United States. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2019;52(1):42–50. doi: 10.1002/eat.23004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh O., McNicholas F. Assessment and management of anorexia nervosa during COVID-19. Irish Journal of Psychological Medicine. 2020;37(3):187–191. doi: 10.1017/ipm.2020.60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weissman R.S., Bauer S., Thomas J.J. Access to evidence-based care for eating disorders during the COVID-19 crisis. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2020;53(5):369–376. doi: 10.1002/eat.23279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weissman R.S., Bauer S., Thomas J.J. 2020. Access to evidence‐based care for eating disorders during the COVID‐19 crisis. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams S., Reid M. Understanding the experience of ambivalence in anorexia nervosa: The maintainer's perspective. Psychology and Health. 2010;25(5):551–567. doi: 10.1080/08870440802617629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organisation Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic. 2021. https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel- coronavirus-2019 August 22, Retrieved from World Health Organisation:

- Zangi H.A., Hauge M.I., Steen E., Finset A., Hagen K.B. “I am not only a disease, I am so much more”. Patients with rheumatic diseases' experiences of an emotion-focused group intervention. Patient Education and Counseling. 2011;85(3):419–424. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2010.12.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]