Abstract

We analyse the early effects of the COVID-19 crisis and lockdown in South Africa on women’s and men’s work in the paid and unpaid (care) economies. Because women and men typically have different roles in both spheres, it is likely that they would experience the negative effects of the crisis unevenly, potentially exacerbating existing inequalities. Based on a large national survey conducted during South Africa’s lockdown period, we find that women have been affected disproportionately by the crisis. While women comprised less than half of the employed in February, they experienced two-thirds of the net job losses between February and April, with the most vulnerable groups affected more. Among those who remained in employment, there was a larger fall in working hours among women than men. Compounding these disproportionate effects in the labour market, women also took on more of the additional childcare that resulted following school closures. The crisis has therefore increased gender inequality in South Africa, reversing some of the hard-won gains of the previous 25 years.

Keywords: COVID-19, Gender inequality, Employment, Care work, South Africa

1. Introduction

Men and women experience the negative effects of health and economic crises unevenly because they typically have different roles in the labour market and the home. In previous recessions, men have tended to suffer greater job losses than women, while women have borne the brunt of increased austerity and cutbacks in public services as a result of their role in unpaid (care) work1 (Wenham, Smith, & Morgan, 2020). However, the early predictions on the COVID-19 crisis have been that women will be disproportionately affected in both the workplace and the home (Alon, Doepke, Olmstead-Rumsey, & Tertilt, 2020). This is because women predominate in many of the ‘non-essential’ retail and service occupations that have been severely affected by the crisis and that cannot be performed remotely, such as those in the personal care, restaurant, hospitality and domestic work sectors (Alon et al., 2020; Hupkau and Petrongolo, 2020).

Further, people’s ability to undertake paid work or work the same hours as before, will be influenced by what is happening in the home. The unprecedented closure of schools and childcare facilities and the scaling back of many non-COVID-19 healthcare services, resulted in a dramatic increase in care work within households. Given entrenched social norms about who should be responsible for care, it has been predicted that women would bear much of this additional burden (Alon et al., 2020; Cattan, Farquharson, Krutikova, Phimister, & Sevilla, 2020).

The early evidence from rapid assessments in countries such as the US, the UK and Israel suggests that women were more likely than men to lose their jobs, quit, or work fewer hours during lockdown (Adams-Prassl, Boneva, Golin, & Rauh, 2020; Kristal & Yaish, 2020). In contrast, women in Turkey were less likely to experience job losses than men, while there was no gender difference in the probability of job loss in Germany (Adams-Prassl et al., 2020; Ilkkaracan & Memis, 2020). This suggests that in terms of labour market outcomes, local context matters. However, in all studies that collected data on time spent on childcare, women shouldered a greater share of the additional care work (Andrew et al., 2020; Ilkkaracan & Memis, 2020; Sevilla & Smith, 2020).

In this paper, we contribute to the emerging literature on COVID-19 and gender inequality by exploring unique data from a country in the global south. The National Income Dynamics Study - Coronavirus Rapid Mobile Survey (NIDS-CRAM) is the largest non-medical research project on COVID-19 currently underway in South Africa (and more broadly on the continent). The aim of the project is to collect reliable data to track the socio-economic effects of the crisis at the various stages of the country’s ongoing lockdown.

Understanding the gendered effects of COVID-19 is critical as women in South Africa, as in other parts of the world, were already under-represented in the labour market and over-represented in unpaid care work (Posel & Casale, 2019). The study of gender inequality in South Africa has added significance because of the importance of women’s income in many South African households. Years of racial segregation during Apartheid disrupted family life, and rates of marriage are low (and declining still). Approximately four of every ten households are headed by women. Further, children are far more likely to live with their mother than their father, resulting in the majority receiving both physical and financial care from women (Hatch & Posel, 2018). The implications of this double burden are severe, with poverty rates substantially higher among women and children than men (Posel & Rogan, 2012).

2. Data and methods

The NIDS-CRAM project emerged from the joint efforts of a consortium of over 30 academics from universities across the country (of which the authors form part). This paper uses data from the first wave of NIDS-CRAM, released on 15 July 2020. The survey took the form of a computer-assisted telephonic interview among a sample of 7074 South African adults aged 18 and older. Interviews were conducted between 7 May and 27 June 2020 and respondents were asked a range of questions on employment, household welfare and health behaviour. While a number of smaller rapid online or telephone surveys have been conducted since the crisis began, the advantage of NIDS-CRAM is that it collects information on a nationally representative sample of adults, to the extent possible under the circumstances.2

Where relevant, information was collected on two key periods – February or ‘pre-crisis’ (i.e. before the first case of COVID-19 was recorded in South Africa on 5 March 2020), and April or the first full month of the country’s 'hard' lockdown period (which lasted from 27 March to 30 April 2020). During this hard lockdown phase (officially Level 5), only essential workers were allowed to work (predominantly those in healthcare and food provision), although non-essential workers who could work from home were encouraged to do so. All schools, childcare facilities and paid domestic work were also suspended. The hard lockdown period in South Africa was noted for being one of the strictest in the world, with the police and army deployed countrywide to ensure compliance.

Descriptive statistics are used to analyse gender differences in outcomes, and t-tests are estimated to gauge statistical significance. All data presented are weighted, and standard errors are corrected for survey design features (namely clustering and stratification).

3. Gendered employment effects of the crisis and early lockdown

In this section, we compare employment outcomes for men and women in February (pre-crisis) and April (the first full month of the lockdown). In keeping with standard ILO definitions, a person is defined as employed if they had worked in “any kind of job”, had done “work for any profit or pay, even if just for an hour or a small amount”, had been engaged in “any kind of business such as selling things - big or small – even if only for one hour”, or if they had a job/activity they would return to in the next 4 weeks.

Table 1 shows that pre-crisis, women were less likely to be employed than men (46% vs 59% of all adults aged 18 and over3 ), and if employed, they worked fewer hours on average per week (35 vs 39 h). By April, both employment and mean hours worked had fallen substantially for women and men: only 36% of women were employed compared to 54% of men, and employed women worked an average of 23 h a week compared to 29 h for employed men. However, the changes were relatively larger for women. Between February and April, employment fell by approximately 1.9 million jobs or 22% for women, and by just under a million jobs or 10% for men.4 Put differently, even though women comprised under half of the employed in February, they accounted for a staggering two-thirds of job losses.5 Among those employed, mean hours worked fell by 35% for women and 26% for men. Gender gaps in the labour market therefore increased substantially in the early lockdown phase.

Table 1.

Employment and hours worked in February and April 2020, adults 18 and older.

| Women | Men | |

|---|---|---|

| February | ||

| Number employed | 8 520 000 (504 000) |

9 706 000 (583 000) |

| % employed | 46.0% (1.21) |

59.4%* (1.6) |

| If employed: | ||

| Mean hours worked per week | 35.3 (0.6) |

38.7* (0.8) |

| % reporting zero hours | 4.5% (0.9) |

5.9% (1.0) |

| % reporting zero earnings | 7.1% (1.1) |

4.2% (0.9) |

| April | ||

| Number employed | 6 639 000 (400 000) |

8 716 000* (544 000) |

| % employed | 35.8% (1.2) |

53.6%* (1.6) |

| If employed: | ||

| Mean hours worked per week | 23.1 (1.1) |

28.7* (1.1) |

| % reporting zero hours | 35.3% (2.2) |

26.3%* (2.0) |

| % reporting zero earnings | 13.3% (1.4) |

12.1% (1.4) |

Notes: Standard errors in parentheses.

Gender differences significant at 10 percent level at least.

Source: NIDS-CRAM (2020).

Included in the employment figures are workers who reported having a job (or a job to return to), but who did not work any hours. In February, this group of workers most likely comprised those who were on leave, representing just under 5% of women and 6% of men. However, by April, these percentages had increased almost eightfold for women to 35%, and a little over fourfold for men to 26% (Table 1). The increase likely captures non-essential workers unable to work (or work from home) (a group we could refer to loosely as ‘furloughed’ workers); and again, women were much more likely than men to find themselves in this situation.

Unfortunately, we cannot measure by how much earnings declined between February and April, but we do know whether respondents received any remuneration. The percentage of the employed who reported zero earnings increased from 7% to 13% for women and from 4% to 12% for men between February and April (Table 1). Despite these large increases, this still represents a relatively small share of the employed in April. This suggests that, in the first month of lockdown at least, workers either lost their jobs entirely, or if they retained them, continued to earn some positive amount.

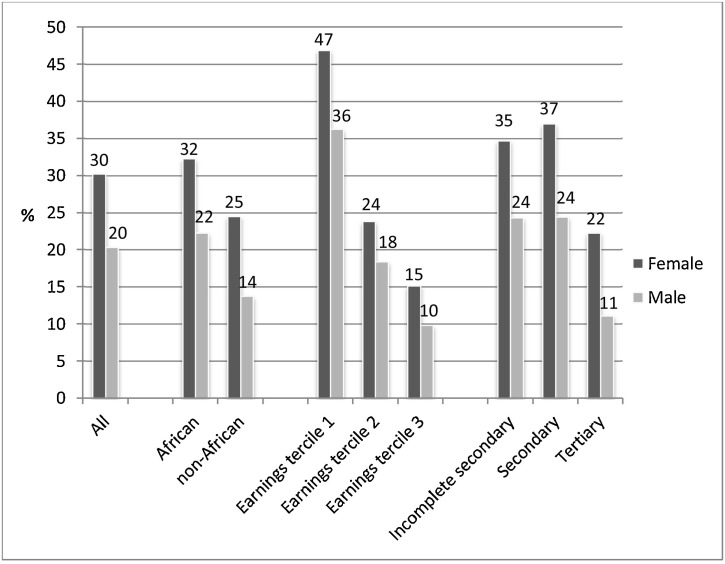

Finally, we look at which groups suffered most from the job losses. Fig. 1 shows the percentage of the employed in February without a job in April (or even a job to return to). As expected, the most vulnerable groups are affected more, namely African6 workers, those in the lower earnings terciles in February, and those without a tertiary education. An alarming statistic is that almost half of all employed women (47%) in the lowest tercile reported losing their job, compared to just over a third (36%) of employed men in the poorest tercile. In the highest tercile, in contrast, ‘only’ 15% of employed women and 10% of employed men had lost their job by April. Although we do not have information on sector or type of employment in February, we know from previous surveys that women in the lowest earnings tercile comprise those in small-scale activities in the informal sector, in non-standard, casual or piecemeal work, and in low-skilled service jobs such as domestic work (Posel & Casale, 2019).

Fig. 1.

Job losses by sub-group (%).

Notes: The bars show the percentage of workers in February who were no longer employed in April. Earnings terciles are based on February earnings.

Source: NIDS-CRAM (2020).

4. Care work and the effects of COVID-19

In addition to severe disruptions in the labour market, the unprecedented closure of schools and childcare facilities destabilised work in the home. Pre-crisis, some 16 million children were enrolled in a school or early childhood development centre.7 Most families therefore would have had their children at home for an extra 5–9 h a day. In addition, during the hard lockdown, domestic workers and childminders, of whom there were approximately a million in South Africa pre-crisis, were unable to work in private households.

Pre-lockdown, women assumed greater responsibility for childcare than men. The reason for this is twofold. First, children are more likely to be living with their mother than their father in South Africa, and where they do not live with either parent, they are often in the care of a grandmother (Hatch & Posel, 2018). Second, even among those living with children, women spend more time (over 3 h more a day) on unpaid work than men (Rubiano-Matulevich & Viollaz, 2019). It is therefore not surprising that they would carry more of the additional childcare work during lockdown.

Data in NIDS-CRAM confirm that women were significantly more likely than men to be living with children at the time of the interview (Table 2 ). Approximately 74% of women reported living with at least one child aged 0–17 compared to 61% of men, and among those living with children, women reported living with a higher number of children on average. The vast majority of these women and men (88%) reported that at least one co-resident child had attended formal schooling pre-lockdown.

Table 2.

Living arrangements at time of interview, 2020.

| Women | Men | |

|---|---|---|

| % living with at least one child 0–17 | 74.4% (1.4) |

60.9%* (1.6) |

| Mean no. of children (conditional on living with a child) | 2.6 (0.07) |

2.4* (0.06) |

| % living with at least one child 0–17 attending school pre-lockdowna | 88.3% (1.0) |

88.4% (1.3) |

| Mean no. of children attending school pre-lockdown (conditional on living with an attending child)a | 2.4 (0.06) |

2.3 (0.06) |

Notes: a Conditional on living with children at time of interview (i.e. 5140 individuals out of the total sample of respondents).

Standard errors in parentheses.

Gender differences significant at 10 percent level at least.

Source: NIDS-CRAM (2020).

However, even among those living with at least one child at the time of the interview, our data indicate that women provided more of the additional childcare during lockdown. Table 3 shows that 73% of women and 66% of men living with children reported spending more time than usual on childcare during April.8 Most people who reported additional childcare spent over four hours more a day on this work, with 79% of women versus 65% of men in this category.9 The additional time spent on childcare is relatively insensitive to employment status, with women continuing to perform more childcare than men even if employed. For instance, among the employed who provided more childcare than usual in April, 80% of women compared to 64% of men reported over four hours extra a day. The corresponding figures for those not employed are 79% and 67%.10

Table 3.

Percentage of adults reporting additional childcare in April 2020 (conditional on living with children).

| Women | Men | |

|---|---|---|

| All adults | ||

| % reporting additional childcare | 73.2% (1.2) |

66.4%* (1.8) |

| % spending over 4 more hours a daya | 79.3% (1.3) |

65.1%* (2.2) |

| Employed in April | ||

| % reporting additional childcare | 71.5% (2.2) |

67.5% (2.4) |

| % spending over 4 more hours a daya | 79.6% (2.2) |

64.2%* (3.0) |

| NOT employed in April | ||

| % reporting additional childcare | 74.1% (1.5) |

65.0%* (2.5) |

| % spending over 4 more hours a daya | 78.9% (1.7) |

67.3%* (3.4) |

Notes: Standard errors in parentheses.

Gender differences significant at 10 percent level at least.

Conditional on spending more time on childcare in April.

Source: NIDS-CRAM (2020).

Overall, the results suggest that while most adults living with children spent more time on childcare, and at least four extra hours a day, women did this more often than men. This gender gap in childcare would have been over and above the childcare work done pre-crisis, the burden of which already fell more heavily on women. Further, our analysis likely underestimates the amount of additional unpaid work performed in the home, as the survey did not collect information on activities such as cooking, cleaning and care of the elderly. This kind of work, ordinarily done by women in South Africa, would also have increased during the lockdown given the inability to outsource any domestic work and the limits on non-COVID related health services.11

5. Concluding discussion

The strict lockdown and school closures in South Africa severely destabilised work in both the paid and unpaid (care) economies. Understanding who is affected more by these shocks is key to designing appropriate responses (United Nations, 2020). The findings from a large national survey reported here suggest that while both women and men have been affected by the crisis, women have been far more severely affected. As a result, gender inequalities in the labour market and the home have risen.

The implications of these effects for women and the children they support are likely to be dire. Women were already in a more precarious socio-economic position than men before the COVID-19 crisis; the loss of work and increased burden of care will place additional pressure on women’s economic wellbeing, and perhaps also their physical and mental health, with knock-on effects for children. Some of the data collected in the NIDS-CRAM survey already point to this: a higher percentage of women than men reported that their household had run out of money for food in April (49% vs 45%), and that a child had gone hungry in the previous seven days (17% vs 15%).

While we are only measuring some of the short-term impacts of the crisis, future work should explore whether the gendered effects reported here intensify or subside as it unfolds. However, we would predict that any disproportionate effect felt by women in the short-term will likely result in longer-term inequalities. People who have lost their jobs, or who cannot work due to childcare responsibilities, may struggle to get them back. Fewer hours worked now can affect future pay and promotion opportunities. And short-term household income cuts can have long-term and maybe irreversible effects, for example, through the sale of assets, increased indebtedness, or malnutrition among children. Sadly, we run the risk of seeing reversals to some of the hard-earned improvements in gender equality documented over the last 25 years in South Africa (Posel & Casale, 2019).

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors report no declarations of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the others members of the NIDS-CRAM data collection and research team for their input on the work at various stages of the project. Special thanks go to Dr Nic Spaull who provided comments on the longer working paper version of this article (available at https://cramsurvey.org/reports/#wave-1). Funding for the broader NIDS-CRAM project was provided by the Allan & Gill Gray Philanthropy Fund, the Federated Employers Mutual Education Fund, and the Michael & Susan Dell Foundation.

Footnotes

The term ‘unpaid work’ is used widely in the feminist economics literature to draw attention to the unremunerated work that occurs outside of the labour market, but that is nonetheless highly productive and valuable to society, namely cooking, cleaning, caring for children, the sick and the elderly, etc.

This was achieved by interviewing a sub-sample of adults from a pre-existing longitudinal household survey, the National Income Dynamics Study (NIDS), which had been running since 2008. The NIDS-CRAM data and associated technical reports (providing more detail on sampling, survey design and representivity) can be accessed at https://cramsurvey.org/.

The figures presented here are for all adults aged 18 years and older rather than for the working-age population (18 to 59 years). The full sample of respondents was included for two main reasons: to maximise the sample size in both sets of analyses on paid and unpaid work; and because about 21% (weighted) of those over the age of 59 reported being employed in February (and we want to also record their welfare losses). However, the gender gaps reported are largely unchanged when we restrict the analysis to the working-age sample.

The gender gap in the probability of losing a job among those who were employed pre-crisis remains largely unchanged (i.e. in the region of 10 percentage points) when controlling for age and education. If anything, the gap increases marginally when controlling for education, because employed women are on average slightly more educated than employed men in South Africa. Probit regression results can be made available by the authors on request.

The effect reported here is far more pronounced than that found elsewhere. For example in the US, women also made up just under half the employed pre-crisis, but were responsible for 55% of job losses reported in April, with commentators referring to the crisis as a ‘shecession’ (see NYT, 13 May, ‘Why Some Women Call This Recession a “Shecession”’, https://www.nytimes.com/2020/05/09/us/unemployment-coronavirus-women.html).

The commonly used ‘racial’ categories in South Africa are African/black (accounting for over 80% of the population), Coloured, Indian and white. Due to small sample sizes, we combine the three smaller groups into a category labelled ‘non-Africans’. During the apartheid system of institutionalised racism, Africans were most affected, the consequences of which are still felt today.

To provide perspective, South Africa has a population of roughly 59 million individuals, 37 million of whom are over 17 years.

This gender gap of roughly 6 percentage points in the probability of spending additional time on childcare in April does not change much even after controlling in a probit regression for age, education, and employment status in February and April (for the sample of respondents who were living with children).

Long hours spent on additional childcare were also reported during the UK lockdown (Sevilla & Smith, 2020): in households with children, parents were spending the equivalent of almost a full working week (40 hours) on extra childcare that previously would have been performed by external providers.

This gender gap holds when restricting to the employed working non-zero hours in April.

On a more positive note, the crisis has highlighted how much unpaid care work occurs in the home, and how important it is to sustain paid employment. While women provided more of the additional childcare during April, many men also reported doing more childcare, a result found elsewhere (Andrew et al., 2020; Sevilla & Smith, 2020). This ‘forced experiment on social norms’ may lead to changes in behaviour over the longer-term through men ‘learning by doing’ or forming new attachments with their children (Alon et al., 2020; Hupkau & Petrongolo, 2020). But even if the distribution of childcare reverts to pre-crisis levels, at the very least it may change the way families value unpaid care relative to paid work.

References

- Adams-Prassl A., Boneva T., Golin M., Rauh C. University of Cambridge Institute for New Economic Thinking; 2020. Inequality in the impact of the coronavirus shock: Evidence from Real time surveys. Working Paper 2020/18. [Google Scholar]

- Alon T., Doepke M., Olmstead-Rumsey J., Tertilt M. 2020. The impact of COVID-19 on gender equality. NBER Working Paper 26947. [Google Scholar]

- Andrew A., Cattan S., Costa Dias M., Farquharson C., Kraftman L., Krutikova S., Phimister A., Sevilla A. 2020. How are mothers and fathers balancing work and family under lockdown? Institute for Fiscal Studies (IFS) Briefing Note BN290, UK. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cattan S., Farquharson C., Krutikova S., Phimister A., Sevilla A. 2020. Trying times: How might the lockdown change time use in families? I FS Briefing Note BN284, UK. [Google Scholar]

- Hatch M., Posel D. Who cares for children? A quantitative study of childcare in South Africa. Development Southern Africa. 2018;35(2):267–282. [Google Scholar]

- Hupkau C., Petrongolo B. 2020. Work, care and gender during the COVID-19 crisis. CEP Center for Economic Performance COVID-19 Analysis, No. 002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ilkkaracan I., Memis E. Istanbul Technical and Ankara University; Mimeo: 2020. Transformation in the gender imbalances in paid and unpaid work under the pandemic: Findings from a pandemic time-use survey in Turkey. [Google Scholar]

- Kristal T., Yaish M. Does the coronavirus pandemic level the gender inequality curve? (It doesn’t) Research in Social Stratification and Mobility. 2020;68 [Google Scholar]

- Posel D., Casale D. Gender and the economy in post-apartheid South Africa: Changes and challenges. Agenda. 2019;33(4):3–10. [Google Scholar]

- Posel D., Rogan M. Gendered trends in poverty in the post-apartheid period, 1995–2006. Development Southern Africa. 2012;29(1):97–113. [Google Scholar]

- Rubiano-Matulevich E., Viollaz M. 2019. Gender differences in time use: Allocating time between the market and the household. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper 8981. [Google Scholar]

- Sevilla A., Smith S. 2020. Baby steps: The gender division of childcare during The COVID19 pandemic. IZA Discussion Paper 13302. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations . 2020. Policy brief: The impact of Covid-19 on women. 9 April 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Wenham C., Smith J., Morgan R. Covid-19: The gendered impacts of the outbreak. Lancet. 2020;395(1022):846–848. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30526-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]