Abstract

Across clinical and subclinical samples, anxiety has been associated with increased attentional capture by cues signaling danger. Various cognitive models attribute the onset and maintenance of anxiety symptoms to maladaptive selective information processing. In this brief review, we 1) describe the evidence for the relations between anxiety and attention bias toward threat, 2) discuss the neurobiology of anxiety-related differences in threat bias, 3) summarize work investigating the developmental origins of attention bias toward threat, and 4) examine efforts to translate threat bias research into clinical intervention. Future directions in each area are discussed, including the use of novel analytic approaches improving characterization of threat-processing-related brain networks, clarifying the role of cognitive control in the development of attention bias toward threat, and the need for larger, well-controlled randomized clinical trials examining moderators and mediators of treatment response. Ultimately, this work has important implications for understanding the etiology of and for intervening on anxiety difficulties among children and adults.

Keywords: anxiety, attention bias, threat, amygdala, prefrontal cortex, development, temperament, intervention

Across clinical and subclinical samples, anxiety relates to increased attentional allocation to threat-related cues (Abend et al., 2018, 2021; Bar-Haim et al., 2007; Bishop, 2007; Cisler & Koster, 2010; Dudeney et al., 2015; MacLeod & Mathews, 2012). As such, theories implicate threat-related attentional biases in the etiology and maintenance of anxiety (Bishop, 2007; Lau & Waters, 2017; MacLeod et al., 2002; Mathews & MacLeod, 2002). In this brief review, we: 1) describe the relation between anxiety and threat-related attention, 2) discuss the neurobiology involved in this relation, 3) summarize relevant developmental work, and 4) examine interventions aiming to reduce anxiety by directly manipulating threat-biased attention.

Theory and evidence for attention bias toward threat and its relation to anxiety

Many cognitive models attribute anxiety symptoms to maladaptive information processing (Eysenck et al., 2007; MacLeod & Mathews, 2012; Mogg & Bradley, 2016). These models recognize the relations between clinical measures of anxiety and attention bias toward negative information (Abend et al., 2021; Bar-Haim et al., 2007; Cisler & Koster, 2010; Dudeney et al., 2015; Van Bockstaele et al., 2014). When considering these theories, a critical point involves differentiating between attention versus motoric responses to threats. Anxiety involves hypervigilance of attention toward potentially threatening stimuli (as will be discussed in more detail below). However, studies also routinely show that individuals with anxiety tend to avoid situations where they might encounter a threat. The role of avoidant behavior, as opposed to hypervigilant attention, in anxiety disorders has been reviewed elsewhere (e.g., Pittig et al., 2018). The present review focuses on how anxiety relates to information processing, particularly attentional processing, of threat.

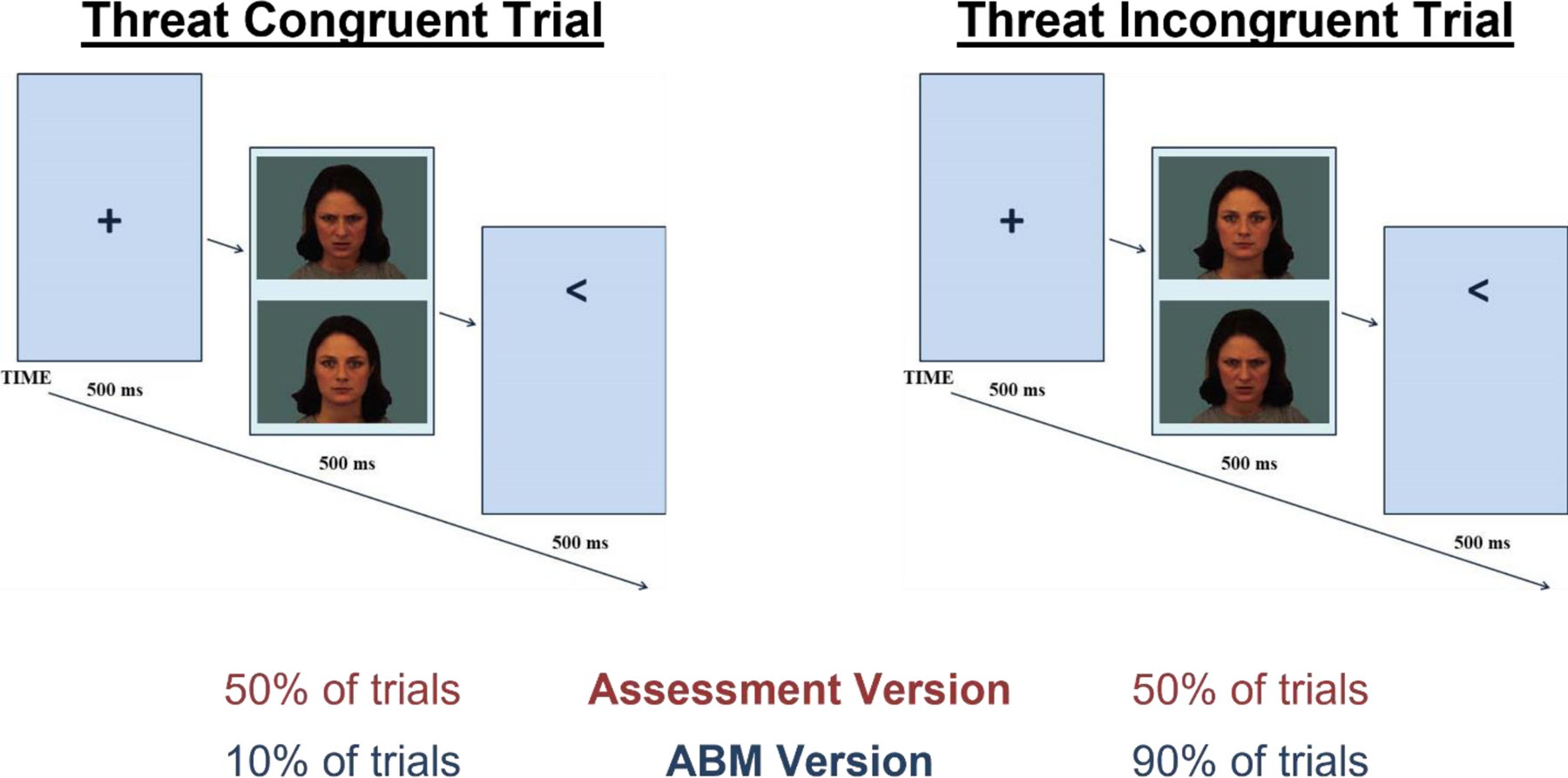

Attentional bias to threat has been assessed using various experimental paradigms such as the emotional Stroop, visual search, emotional spatial cuing task, and dot-probe task. The most commonly used of these is the dot-probe task. In the dot-probe, two stimuli that differ in emotional content (usually one threat-related and one neutral, such as an angry face paired with a neutral face) are briefly shown on a computer screen, followed by a visual probe that appears at the former location of one of the stimuli (Figure 1; MacLeod et al., 1986). Participants are asked to discriminate between two variants of the probe (e.g., the letters ‘F’ and ‘E’, the shapes ‘..’ and ‘:’, or the direction of the arrows ‘<‘ and ‘>‘). In the assessment version of the task, the probes appear with equal probability at the location of the threat-related (threat congruent trials) and neutral stimuli (threat incongruent trials; MacLeod et al., 1986). Because participants are faster to discriminate the probe identity at the attended location, faster reaction times (RTs) on congruent trials relative to incongruent trials (quantified as the difference in mean RTs) indicate attention bias toward threat, whereas the opposite pattern indicates avoidance of threat (Bar-Haim, 2010).

Figure 1.

Schematic of dot-probe task. Adapted from Gober et al., 2021. In this example, participants are asked to indicate the direction of the arrow via a button press. Faster reaction times on threat congruent trials (when the arrow appears in the previous location of the angry face) than on threat incongruent trials (when the arrow appears in the previous location of the neutral face) may indicate the presence of an attention bias toward threat. In the assessment version of the task, the probes appear with equal probability at the location of the threat-related (threat congruent trials) and neutral stimuli (threat incongruent trials; MacLeod et al., 1986). However, when adapted for attention bias modification (ABM) training, the probes nearly always (e.g., on approximately 90% of trials) appear in the previous location of the neutral stimulus. By reducing the likelihood that the probe will appear at the position of the threatening stimulus, ABM aims to shift attention away from threat gradually and implicitly over repeated trials (MacLeod & Mathews, 2012; Shechner & Bar-Haim, 2016).

Compared to non-anxious control participants, anxious participants tend to show more biased attention toward threatening stimuli (Abend et al., 2021; Cisler & Koster, 2010; Salum et al., 2018; Van Bockstaele et al., 2014), although the magnitude of meta- and mega-analytic effects is generally modest (Abend et al., 2018; Bar-Haim et al., 2007; Dudeney et al., 2015). Large heterogeneity of effect sizes across studies may be partly explained by the fact that greater bias toward threat is observed when participants find stimuli more subjectively threatening. For example, attention bias scores are typically greater for fear-relevant images (e.g., snakes, spiders) than non-fear-relevant stimuli (e.g., flowers, mushrooms), and attention bias toward spiders is even greater among participants reporting particularly high levels of spider fear, as compared to those reporting lower levels of spider fear (Lipp & Derakshan, 2005). Similarly, greater attention bias toward faces expressing disgust has been associated with higher subjective ratings of emotional reactivity during a subsequent social stressor (Çek et al., 2016).

Recent work suggests that traditional RT-based measures of threat-biased attention may be unreliable (McNally, 2019; Rodebaugh et al., 2016). This may be, in part, because taking the difference of two highly correlated scores (as dot-probe RTs tend to be) results in a difference score with very little unique variability and, thus, poor internal consistency (Infantolino et al., 2018; McNally, 2019). On the other hand, neuroimaging- and eye-tracking-based measures of attention bias have been shown to have acceptable reliability and demonstrate associations with anxiety (K. Clauss et al., 2022; Haller et al., 2018; Lazarov et al., 2016; White et al., 2016; but see also Lisk et al., 2020 which did not find evidence of threat-biased attention in anxious youth as measured via ocular dwell time). Recent advances in attention bias measurement also suggest that alternative bias calculations, relying on proportion scores or accuracy derived indices of attention rather than on response-time-based indices, can produce measurements with high internal consistency and reliability (e.g., Grafton et al., 2021).

Cognitive models considering attention bias commonly distinguish between automatic and strategic processes, including forms of emotional regulation (Mogg & Bradley, 2016). Automatic processes include rapid, unintentional, uncontrolled cognitive processes outside awareness (i.e., bottom-up or stimulus-driven processes which may be supported by the amygdala and other subcortical limbic regions), whereas strategic processes include more controllable, intentional, and conscious processes (e.g., executive functions, cognitive control supported by regions of the prefrontal cortex; PFC) (Browning et al., 2010; Corbetta & Shulman, 2002; Shechner & Bar-Haim, 2016; Shiffrin & Schneider, 1977). Mogg and Bradley’s integrated framework holds that bottom-up and top-down systems interact to influence whether thoughts and behavior are oriented toward adaptive goals versus on processing goal-irrelevant threat information which could pose danger for the individual (Mogg & Bradley, 2016). Anxiety may increase the salience via a pre-attentive threat evaluation mechanism, biasing attention toward the potential threat even in the absence of conscious awareness. Chronic or severe anxiety, then, may stem from an imbalance between bottom-up and top-down systems, favoring bottom-up processes (Bar-Haim et al., 2007; Mathews & MacLeod, 2002; Mogg & Bradley, 2016). As will be described in the next section, this cognitive account is supported by neuroimaging research.

Neurobiology of threat-related attention and anxiety

Hemodynamic neuroimaging studies have characterized the cortical and subcortical neural circuitry involved in allocating attention toward and away from potential threat (Bishop, 2007; Heeren et al., 2013; Hur et al., 2019; Shechner & Bar-Haim, 2016). From these studies, amygdala-prefrontal circuitry, in particular, appears sensitive to emotional salience and influences top-down control (Bishop, 2007; Sequeira et al., 2021). As will be discussed in this section, most evidence examining the neural correlates of anxiety links anxious symptoms to amygdala hyper-reactivity to threat paired with insufficient control due to prefrontal hypo-reactivity (Bishop, 2007; Shechner & Bar-Haim, 2016).

Specific circuitry components include the amygdala and anterior cingulate cortex (Etkin et al., 2004). Prefrontal cortex (PFC) regions influence attentional control (Browning et al., 2010; Corbetta & Shulman, 2002): the ventrolateral PFC (vlPFC) supports the shifting of attention in response to environmental factors (Corbetta & Shulman, 2002); the dorsolateral PFC (dlPFC) supports maintenance of task-relevant goals (Bishop, 2009); dorsomedial PFC (dmPFC) regulates the interface between affective and motor responses, whereas ventromedial PFC (vmPFC) regulates subcortical, limbic processing in support of context-relevant emotion regulation (Etkin et al., 2011). These regions function in tandem as an integrated neural network (Shechner & Bar-Haim, 2016).

In neuroimaging studies of threat-related attention, participants with clinical anxiety show differences in the function of these brain regions relative to non-anxious peers. These differences have been most evident in the vlPFC and dlPFC, with anxious participants showing lower levels of activation while viewing threatening stimuli compared to non-anxious participants (Britton et al., 2012; Fani et al., 2012; Monk et al., 2008; Telzer et al., 2008). Neuroimaging studies also find anxiety-related differences in fronto-amygdala connectivity in angry versus neutral face contrasts (Hardee et al., 2013; Monk et al., 2008). Similar patterns emerge in treatment studies of anxiety, such that increases in vlPFC responses to angry faces during the dot-probe task have been observed following cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) and pharmacological intervention (i.e., selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors; Maslowsky et al., 2010). Moreover, vlPFC increases, along with amygdala decreases, have also been observed following direct training of threat-related attention (Britton et al., 2015; Eldar & Bar-Haim, 2010; Taylor et al., 2014; White, Sequeira, et al., 2017). Taken together, neuroimaging work highlights brain activation and connectivity among fronto-amygdala regions as key to understanding altered threat-related attention in anxiety.

Advancements in data analytic techniques have yielded new insights into this brain circuitry. For example, a recent study of adolescents compared patterns of functional connectivity at rest to those during the dot-probe task across 17 empirically-defined brain components including the dorsal visual stream, sensory-motor system, visual cortical areas, executive control network, and others (Harrewijn et al., 2020). Connectivity matrices from each paradigm were positively correlated with each other, suggesting that functional hierarchies in the brain may remain stable across states. Although the degree of similarity between the resting and dot-probe connectivity matrices did not directly relate to anxiety, greater similarity between the two matrices was associated with greater threat bias as measured via RT on the dot-probe task (Harrewijn et al., 2020). This suggests that adolescents with a higher degree of overlap between their “default” and threat-related attention brain states may allocate more attention toward threat, and therefore may be at increased risk for anxiety difficulties. Future work will likely benefit from the continued advancement of neuroimaging analytic techniques.

Developmental course of the relations among threat bias, temperament, and anxiety

Understanding the origins of threat bias could improve assessment sensitivity. Behavioral inhibition (BI), an early-childhood temperament style involving negative reactivity to or avoidance of unfamiliar people or contexts, is a strong risk factor for an anxiety diagnosis later in life (J. A. Clauss & Blackford, 2012; N. A. Fox et al., 2020; Kagan et al., 1984; Sandstrom et al., 2020). Nevertheless, up to 60% of children with a history of BI do not develop anxiety disorders (Biederman et al., 1993; Gladstone et al., 2005). Thus, there is a need to identify moderators of the BI-anxiety relation. Using the dot-probe task, Pérez-Edgar et al. showed that adolescents with a history of BI showed greater threat-biased attention than those with low BI, and found that the relation between early BI and anxiety was significantly stronger among those with high levels of threat bias (Pérez-Edgar et al., 2010). Another, more recent study of younger children with a history of BI showed no direct association between BI and threat-biased attention, and found BI predicted anxiety among children displaying attention bias toward threat, away from positive, or with no bias but not among those with a bias away from threat or toward positive (White et al., 2016).

BI has also been associated with altered processing of events that are not explicitly threatening, but that may nevertheless signal potential threat. Specifically, adolescents with a history of BI showed greater electrophysiological responses to novel auditory tones (Marshall et al., 2009; Reeb-Sutherland et al., 2009) and to errors (McDermott et al., 2009) than those without such history(Marshall et al., 2009; Reeb-Sutherland et al., 2009). Among those with a history of high BI, those with larger electrophysiological responses indicating greater attention to these events were at greater risk of an anxiety diagnosis compared to high BI adolescents with smaller responses (McDermott et al., 2009; Reeb-Sutherland et al., 2009). This work highlights attention to potential threat, broadly defined, as a key component in the relation between BI and anxiety (Cole et al., 2016; N. A. Fox et al., 2020; Morales et al., 2015; Morales, Taber-Thomas, et al., 2017; Nozadi et al., 2016; Pérez-Edgar et al., 2011; White, Degnan, et al., 2017).

The association between BI and heightened vigilance to novelty is apparent early in life, though the mechanisms underlying this association remain unclear. There is some evidence that young children and adults with a history of BI display a lower threshold for heightened amygdala activity to novelty (A. S. Fox & Kalin, 2014) and show less amygdala-PFC connectivity (Filippi et al., 2022). Some evidence suggests that parental anxiety, which is associated with BI (Muris et al., 2011), may influence children’s attention bias to threat (N. A. Fox et al., in press). Parental anxiety is concurrently associated with infants’ threat bias (Morales, Brown, et al., 2017), and parental anxiety during early childhood predicts children’s faster detection of angry faces 3 years later (Aktar et al., 2019). Similarly, daughters of mothers with a mood or panic disorder have also been shown to have greater attention bias to threat relative to daughters of mothers with no psychiatric history (Mogg et al., 2012; Montagner et al., 2016).

Consistent with other models of anxiety, work on the BI-anxiety link has also focused on the role of cognitive control in modulating heightened vigilance to novelty. Although few studies examine relations between threat bias and effortful control, Lonigan and Vasey found that children with elevated attention bias toward threat did not develop elevated anxiety if they also exhibited high levels of self-reported effortful control (Lonigan & Vasey, 2009). With regard to BI, there is evidence that children with a history of high BI whose parents rate them as having lower levels of set shifting skills (an example of control) during middle childhood display heightened anxiety as adolescents than those with greater set shifting skills (Buzzell et al., 2021). Similar findings emerge from laboratory assessments of cognitive control. For example, behaviorally inhibited children who displayed heightened task switching skills (as assessed on the Dimensional Change Card Sort task) were less anxious than those with lower task switching skills (White et al., 2011). Recent work guided by Dual Mechanisms of Control Theory (Braver, 2012) distinguished between proactive (i.e., early, preparatory) and reactive (i.e., late, as-needed) modes of control and found that children with a history of BI tend to use less proactive control strategies than their low-BI peers (Buzzell et al., 2021; Troller-Renfree et al., 2019). This is especially important because children with BI who use less proactive or more reactive strategies experience greater anxiety (Buzzell et al., 2021; Troller-Renfree et al., 2019; Troller‐Renfree et al., 2019; Valadez et al., 2021, 2022). Such control-style-specific patterns of moderation have been observed using parent-reported (Buzzell et al., 2021), behavioral (Troller-Renfree et al., 2019; Troller‐Renfree et al., 2019; Valadez et al., 2022), and neural measures of proactive and reactive control (Buzzell et al., 2017; Valadez et al., 2021). Together, this work suggests that a more flexible cognitive control style (indicated by greater use of proactive than reactive control) may decrease anxiety risk among children with a history of high BI. Figure 2 presents an integrative model relating these variables and building on other risk conceptualizations (Bar-Haim et al., 2007; N. A. Fox et al., 2020, in press; Mogg & Bradley, 2016; Pérez-Edgar et al., 2011).

Figure 2.

Model of relations among behavioral inhibition, attention toward potential threat, cognitive control style, and anxiety.

Clinical implications of the role of threat bias in anxiety

The discovery of anxiety-related attention bias motivated the design of procedures to reduce anxiety via the manipulation of this attention bias (Macleod, 1995). One such intervention protocol, attention bias modification (ABM), uses an adapted version of the dot-probe task. As noted previously, the assessment version of the task involves probes presented equally often in the screen locations where the threatening or neutral stimuli formerly appeared. In the modified, training version of the task, however, the probes nearly always (e.g., on 90% of trials) appear in the previous location of the neutral stimulus (MacLeod & Mathews, 2012; Shechner & Bar-Haim, 2016). Because the probe location is manipulated to increase the likelihood of targets appearing at the location of one type of stimulus or the other, the desired attention bias is implicitly and gradually induced over repeated training trials (Abend et al., 2013, 2014; Shechner & Bar-Haim, 2016).

Support for ABM’s efficacy is reviewed elsewhere (Fodor et al., 2020; Gober et al., 2021; Lazarov & Bar-Haim, 2021). Briefly, numerous randomized clinical trials (RCTs) have demonstrated successful modification of attention bias, with greater reductions of threat bias from pre-treatment to post-treatment in an ABM condition compared to a waitlist control condition (Gober et al., 2021; Price, Wallace, et al., 2016). Anxious symptom reduction following ABM has been observed in 8 out of 10 reported meta-analyses addressing this question, with small-to-medium effect sizes (Gober et al., 2021; Jones & Sharpe, 2017). Yet, a number of studies have failed to find significant effects of ABM on anxiety. A recent meta-analysis including a total of 65 ABM anxiety studies found that ABM did not significantly improve anxiety compared to waitlist and sham treatment conditions (typically a version of the task not designed to shift attention toward a specific valenced direction; Fodor et al., 2020). Importantly, however, this meta-analysis pooled a heterogeneous mix of ABM-related protocols; it combined laboratory experiments and clinical trials with wide-ranging sham control conditions, clinical and subclinical populations, outcomes, and with varying levels of blinding, making results somewhat difficult to interpret (see Blackwell, 2020 for a commentary). Perhaps most notably, this meta-analysis combined studies examining effects of ABM on anxiety symptoms with studies testing its effects on symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Although PTSD and anxiety disorders have some overlapping symptoms, many of PTSD’s hallmark symptoms are unique (e.g., recurrent intrusive memories following exposure to one or more traumatic events). As such, PTSD is recognized as separate from anxiety disorders in both the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (5th edition) (American Psychiatric Association, 2013) and the International Classification of Diseases (11th edition) (World Health Organization, 2019). Perhaps more important to the current discussion, however, accumulating evidence suggests different patterns of attention allocation in PTSD relative to anxiety disorders, with PTSD samples demonstrating biased attention specifically toward trauma-relevant stimuli (Pergamin-Hight et al., 2015). When Fodor et al. excluded the seven trials involving participants with PTSD symptoms, ABM’s superiority over both sham and waitlist control conditions reached significance (Fodor et al., 2020). Nevertheless, in addition to substantial effect size heterogeneity across studies, the authors noted either uncertain or high risk of researcher bias (e.g., outcome reporting bias) in the majority of studies they examined, raising the need for more pre-registered, well-controlled trials with larger sample sizes to mitigate researcher bias and enable testing of potential treatment moderators.

Thus far, several potential moderators of ABM efficacy have emerged. These include patient factors such as pre-treatment threat bias and patient age, with larger treatment effects observed among those with greater pre-treatment threat bias (Price, Wallace, et al., 2016) and among adolescents and young adults compared to younger children or older adults (Price, Wallace, et al., 2016). The ABM delivery setting may also moderate treatment outcome, as multiple studies find larger treatment effects among those receiving ABM in a laboratory setting than online (Cristea et al., 2015; Fodor et al., 2020; Heeren et al., 2015; Linetzky et al., 2015; Price, Wallace, et al., 2016; Teng et al., 2019). Additional work in this vein will help optimize treatment protocols and help identify target patient candidates for ABM treatment to maximize clinical benefit.

Given work discussed in the previous section finding that a temperament of BI is associated with heightened attention bias to threat and that those with BI who show this bias are at especially elevated risk for anxiety difficulties, individuals with a history of BI may be particularly promising candidates for ABM treatment. One RCT tested the efficacy of ABM in a sample of 9- to 12-year-old children who were all identified as high in BI. Although active ABM did not modify RT bias scores, it significantly reduced separation anxiety symptoms compared to a sham ABM condition (Liu et al., 2018). This study also included fMRI assessments at baseline and post-treatment and found that, compared to sham ABM, active ABM significantly decreased amygdala and insula activation and increased vlPFC activation during incongruent (vs. congruent) dot-probe trials. Furthermore, mediation analysis revealed that increases in vlPFC activation mediated the relation between intervention group assignment and changes in separation anxiety symptoms (Liu et al., 2018). In other words, even in the absence of behavioral changes, ABM may increase top-down regulatory brain activity in children with BI, which, in turn, may lead to anxiety reduction.

In addition to serving as a stand-alone treatment, ABM has also been tested as an adjuvant to CBT in three RCTs involving anxious youth, with encouraging but mixed results (Salum et al., 2018; Shechner et al., 2014; White, Sequeira, et al., 2017). Shechner et al. found that both CBT + active ABM and CBT + sham ABM showed greater improvements in clinician-rated anxiety than a group receiving CBT alone, but that the CBT + active ABM group showed greater improvements in self- and parent-rated anxiety than the CBT + sham ABM group. White et al. found that CBT + active ABM resulted in greater clinician-rated anxious symptom improvement than CBT + sham ABM. Salum et al. found significant improvement in clinician-rated anxiety in both a CBT + active ABM group and a CBT + sham ABM group but found no significant differences between them. Taken together, this work suggests ABM holds preliminary promise as an adjuvant treatment to CBT. However, it also aligns with studies assessing ABM as a standalone treatment which find that even sham ABM may be effective at alleviating anxiety (Pettit et al., 2020).

That anxiety reduction has been observed even in sham ABM conditions relative to waitlist controls raises key questions about the mechanism(s) underlying ABM treatment response. Specifically, it suggests that treatment expectancies or mere exposure to threat-relevant stimuli may be sufficient to achieve anxiety reduction, even in the absence of any attention manipulation. To address these questions, a recent RCT compared four treatments that dissociated spatial attention and threat exposure while equating treatment expectancies (Linetzky et al., 2020). Linetzky et al. found that although changes in self-rated attentional control correlated with changes in anxiety symptoms, all four groups demonstrated large reductions in anxiety with no significant differences between groups. The authors concluded that results did not support either spatial attention or threat exposure as underlying mechanisms and instead may point to possible expectancy effects, nonspecific treatment effects on general attention control ability, or behavioral activation due to attending twice-weekly sessions (Linetzky et al., 2020).

Overall, although important questions remain about moderators and mechanisms of ABM’s impact on anxiety, the bulk of RCT evidence suggests ABM continues to show promise for youth and adults with anxiety disorders when used as a stand-alone treatment or as an adjuvant treatment to CBT (Lazarov & Bar-Haim, 2021). More well-controlled, large-N RCTs will likely be needed before ABM is accepted as a frontline evidence-supported therapy for anxiety. Additionally, novel and possibly more robust ABM interventions are emerging that directly manipulate participants’ eye gaze (Lazarov et al., 2017; Price, Greven, et al., 2016). Lastly, more efforts to identify the precise causal mechanism(s) behind ABM’s clinical benefits are needed to inform optimization of ABM-related protocols and thus further improve treatment outcomes.

Summary and Conclusions

Maladaptive selective information processing likely plays a role in the onset and maintenance of anxiety disorders. A large body of work has begun to elucidate the neurobiology involved in, the developmental origins of, and the clinical benefits of manipulating threat-biased attention. These ongoing efforts may benefit from the use of novel analytic approaches improving characterization of threat-processing-related brain networks and behavior, from clarifying the role of cognitive control in the development of attention bias toward threat, and from larger ABM studies examining moderators and mediators of treatment response. Ultimately, this work has important implications for understanding the etiology and ability to intervene on anxiety difficulties among children and adults.

Funding Sources:

This work was supported by National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) intramural research program project number ZIA-MH002782 (to DSP), NIMH extramural grant number U01MH093349 (to NAF), and Israel Science Foundation grant number 1811/17 (to YB).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Abend R, Bajaj MA, Matsumoto C, Yetter M, Harrewijn A, Cardinale EM, Kircanski K, Lebowitz ER, Silverman WK, Bar-Haim Y, Lazarov A, Leibenluft E, Brotman M, & Pine DS (2021). Converging Multi-modal Evidence for Implicit Threat-Related Bias in Pediatric Anxiety Disorders. Research on Child and Adolescent Psychopathology, 49(2), 227–240. 10.1007/s10802-020-00712-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abend R, de Voogd L, Salemink E, Wiers RW, Pérez-Edgar K, Fitzgerald A, White LK, Salum GA, He J, Silverman WK, Pettit JW, Pine DS, & Bar-Haim Y (2018). Association between attention bias to threat and anxiety symptoms in children and adolescents. Depression and Anxiety, 35(3), 229–238. 10.1002/da.22706 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abend R, Karni A, Sadeh A, Fox NA, Pine DS, & Bar-Haim Y (2013). Learning to Attend to Threat Accelerates and Enhances Memory Consolidation. PLOS ONE, 8(4), e62501. 10.1371/journal.pone.0062501 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abend R, Pine DS, Fox NA, & Bar-Haim Y (2014). Learning and Memory Consolidation Processes of Attention-Bias Modification in Anxious and Nonanxious Individuals. Clinical Psychological Science, 2(5), 620–627. 10.1177/2167702614526571 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Aktar E, Van Bockstaele B, Pérez-Edgar K, Wiers RW, & Bögels SM (2019). Intergenerational transmission of attentional bias and anxiety. Developmental Science, 22(3), e12772. 10.1111/desc.12772 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th edition). [Google Scholar]

- Bar-Haim Y (2010). Research Review: Attention bias modification (ABM): a novel treatment for anxiety disorders. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 51(8), 859–870. 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2010.02251.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bar-Haim Y, Lamy D, Pergamin L, Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ, & van IJzendoorn MH (2007). Threat-related attentional bias in anxious and nonanxious individuals: A meta-analytic study. Psychological Bulletin, 133(1), 1–24. 10.1037/0033-2909.133.1.1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biederman J, Rosenbaum JF, Bolduc-Murphy EA, Faraone SV, Chaloff J, Hirshfeld DR, & Kagan J (1993). A 3-year follow-up of children with and without behavioral inhibition. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 32(4), 814–821. 10.1097/00004583-199307000-00016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bishop SJ (2007). Neurocognitive mechanisms of anxiety: An integrative account. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 11(7), 307–316. 10.1016/j.tics.2007.05.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bishop SJ (2009). Trait anxiety and impoverished prefrontal control of attention. Nature Neuroscience, 12(1), Article 1. 10.1038/nn.2242 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blackwell SE (2020). Clinical efficacy of cognitive bias modification interventions. The Lancet Psychiatry, 7(6), 465–467. 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30170-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braver TS (2012). The variable nature of cognitive control: A dual mechanisms framework. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 16(2), 106–113. 10.1016/j.tics.2011.12.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Britton JC, Bar-Haim Y, Carver FW, Holroyd T, Norcross MA, Detloff A, Leibenluft E, Ernst M, & Pine DS (2012). Isolating neural components of threat bias in pediatric anxiety. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 53(6), 678–686. 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2011.02503.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Britton JC, Suway JG, Clementi MA, Fox NA, Pine DS, & Bar-Haim Y (2015). Neural changes with attention bias modification for anxiety: A randomized trial. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, 10(7), 913–920. 10.1093/scan/nsu141 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Browning M, Holmes EA, Murphy SE, Goodwin GM, & Harmer CJ (2010). Lateral Prefrontal Cortex Mediates the Cognitive Modification of Attentional Bias. Biological Psychiatry, 67(10), 919–925. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.10.031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buzzell GA, Morales S, Bowers ME, Troller-Renfree SV, Chronis-Tuscano A, Pine DS, Henderson HA, & Fox NA (2021). Inhibitory control and set shifting describe different pathways from behavioral inhibition to socially anxious behavior. Developmental Science, 24(1), e13040. 10.1111/desc.13040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buzzell GA, Troller-Renfree SV, Barker TV, Bowman LC, Chronis-Tuscano A, Henderson HA, Kagan J, Pine DS, & Fox NA (2017). A neurobehavioral mechanism linking behaviorally inhibited temperament and later adolescent social anxiety. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 56(12), 1097–1105. 10.1016/j.jaac.2017.10.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Çek D, Sánchez A, & Timpano KR (2016). Social Anxiety–Linked Attention Bias to Threat Is Indirectly Related to Post-Event Processing Via Subjective Emotional Reactivity to Social Stress. Behavior Therapy, 47(3), 377–387. 10.1016/j.beth.2016.02.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cisler JM, & Koster EHW (2010). Mechanisms of attentional biases towards threat in anxiety disorders: An integrative review. Clinical Psychology Review, 30(2), 203–216. 10.1016/j.cpr.2009.11.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clauss JA, & Blackford JU (2012). Behavioral Inhibition and Risk for Developing Social Anxiety Disorder: A Meta-Analytic Study. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 51(10), 1066–1075.e1. 10.1016/j.jaac.2012.08.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clauss K, Gorday JY, & Bardeen JR (2022). Eye tracking evidence of threat-related attentional bias in anxiety- and fear-related disorders: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review, 93, 102142. 10.1016/j.cpr.2022.102142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole CE, Zapp DJ, Fettig NB, & Pérez-Edgar K (2016). Impact of attention biases to threat and effortful control on individual variations in negative affect and social withdrawal in very young children. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 141, 210–221. 10.1016/j.jecp.2015.09.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corbetta M, & Shulman GL (2002). Control of goal-directed and stimulus-driven attention in the brain. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 3(3), Article 3. 10.1038/nrn755 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cristea IA, Kok RN, & Cuijpers P (2015). Efficacy of cognitive bias modification interventions in anxiety and depression: Meta-analysis. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 206(1), 7–16. 10.1192/bjp.bp.114.146761 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dudeney J, Sharpe L, & Hunt C (2015). Attentional bias towards threatening stimuli in children with anxiety: A meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review, 40, 66–75. 10.1016/j.cpr.2015.05.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eldar S, & Bar-Haim Y (2010). Neural plasticity in response to attention training in anxiety. Psychological Medicine, 40(4), 667–677. 10.1017/S0033291709990766 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Etkin A, Egner T, & Kalisch R (2011). Emotional processing in anterior cingulate and medial prefrontal cortex. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 15(2), 85–93. 10.1016/j.tics.2010.11.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Etkin A, Klemenhagen KC, Dudman JT, Rogan MT, Hen R, Kandel ER, & Hirsch J (2004). Individual Differences in Trait Anxiety Predict the Response of the Basolateral Amygdala to Unconsciously Processed Fearful Faces. Neuron, 44(6), 1043–1055. 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.12.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eysenck MW, Derakshan N, Santos R, & Calvo MG (2007). Anxiety and cognitive performance: Attentional control theory. Emotion, 7(2), 336–353. 10.1037/1528-3542.7.2.336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fani N, Tone EB, Phifer J, Norrholm SD, Bradley B, Ressler KJ, Kamkwalala A, & Jovanovic T (2012). Attention bias toward threat is associated with exaggerated fear expression and impaired extinction in PTSD. Psychological Medicine, 42(3), 533–543. 10.1017/S0033291711001565 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filippi CA, Valadez EA, Fox NA, & Pine DS (2022). Temperamental risk for anxiety: Emerging work on the infant brain and later neurocognitive development. Current Opinion in Behavioral Sciences, 44, 101105. 10.1016/j.cobeha.2022.101105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fodor LA, Georgescu R, Cuijpers P, Szamoskozi Ş, David D, Furukawa TA, & Cristea IA (2020). Efficacy of cognitive bias modification interventions in anxiety and depressive disorders: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. The Lancet Psychiatry, 7(6), 506–514. 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30130-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox AS, & Kalin NH (2014). A Translational Neuroscience Approach to Understanding the Development of Social Anxiety Disorder and Its Pathophysiology. American Journal of Psychiatry, 171(11), 1162–1173. 10.1176/appi.ajp.2014.14040449 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox NA, Buzzell GA, Morales S, Valadez EA, Wilson M, & Henderson HA (2020). Understanding the Emergence of Social Anxiety in Children With Behavioral Inhibition. Biological Psychiatry 10.1016/j.biopsych.2020.10.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Fox NA, Zeytinoglu S, Valadez EA, Buzzell GA, Morales S, & Henderson HA (in press). Developmental pathways linking early behavioral inhibition to later anxiety [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Gladstone GL, Parker GB, Mitchell PB, Wilhelm KA, & Malhi GS (2005). Relationship between self-reported childhood behavioral inhibition and lifetime anxiety disorders in a clinical sample. Depression and Anxiety, 22(3), 103–113. 10.1002/da.20082 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gober CD, Lazarov A, & Bar-Haim Y (2021). From cognitive targets to symptom reduction: Overview of attention and interpretation bias modification research. Evidence-Based Mental Health, 24(1), 42–46. 10.1136/ebmental-2020-300216 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grafton B, Teng S, & MacLeod C (2021). Two probes and better than one: Development of a psychometrically reliable variant of the attentional probe task. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 138, 103805. 10.1016/j.brat.2021.103805 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haller SP, Kircanski K, Stoddard J, White LK, Chen G, Sharif-Askary B, Zhang S, Towbin KE, Pine DS, Leibenluft E, & Brotman MA (2018). Reliability of neural activation and connectivity during implicit face emotion processing in youth. Developmental Cognitive Neuroscience, 31, 67–73. 10.1016/j.dcn.2018.03.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardee JE, Benson BE, Bar-Haim Y, Mogg K, Bradley BP, Chen G, Britton JC, Ernst M, Fox NA, Pine DS, & Pérez-Edgar K (2013). Patterns of Neural Connectivity During an Attention Bias Task Moderate Associations Between Early Childhood Temperament and Internalizing Symptoms in Young Adulthood. Biological Psychiatry, 74(4), 273–279. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2013.01.036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrewijn A, Abend R, Linke J, Brotman MA, Fox NA, Leibenluft E, Winkler AM, & Pine DS (2020). Combining fMRI during resting state and an attention bias task in children. NeuroImage, 205, 116301. 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2019.116301 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heeren A, De Raedt R, Koster E, & Philippot P (2013). The (neuro)cognitive mechanisms behind attention bias modification in anxiety: Proposals based on theoretical accounts of attentional bias. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 7. 10.3389/fnhum.2013.00119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heeren A, Mogoașe C, Philippot P, & McNally RJ (2015). Attention bias modification for social anxiety: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review, 40, 76–90. 10.1016/j.cpr.2015.06.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hur J, Stockbridge MD, Fox AS, & Shackman AJ (2019). Chapter 16 - Dispositional negativity, cognition, and anxiety disorders: An integrative translational neuroscience framework. In Srinivasan N (Ed.), Progress in Brain Research (Vol. 247, pp. 375–436). Elsevier. 10.1016/bs.pbr.2019.03.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Infantolino ZP, Luking KR, Sauder CL, Curtin JJ, & Hajcak G (2018). Robust is not necessarily reliable: From within-subjects fMRI contrasts to between-subjects comparisons. NeuroImage, 173, 146–152. 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2018.02.024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones EB, & Sharpe L (2017). Cognitive bias modification: A review of meta-analyses. Journal of Affective Disorders, 223, 175–183. 10.1016/j.jad.2017.07.034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kagan J, Reznick JS, Clarke C, Snidman N, & Garcia-Coll C (1984). Behavioral inhibition to the unfamiliar. Child Development, 55(6), 2212–2225. JSTOR. 10.2307/1129793 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lau JYF, & Waters AM (2017). Annual Research Review: An expanded account of information-processing mechanisms in risk for child and adolescent anxiety and depression. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 58(4), 387–407. 10.1111/jcpp.12653 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazarov A, Abend R, & Bar-Haim Y (2016). Social anxiety is related to increased dwell time on socially threatening faces. Journal of Affective Disorders, 193, 282–288. 10.1016/j.jad.2016.01.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazarov A, & Bar-Haim Y (2021). Emerging Domain-Based Treatments for Pediatric Anxiety Disorders. Biological Psychiatry, 89(7), 716–725. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2020.08.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazarov A, Pine DS, & Bar-Haim Y (2017). Gaze-Contingent Music Reward Therapy for Social Anxiety Disorder: A Randomized Controlled Trial. American Journal of Psychiatry, 174(7), 649–656. 10.1176/appi.ajp.2016.16080894 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linetzky M, Pergamin-Hight L, Pine DS, & Bar-Haim Y (2015). Quantitative Evaluation of the Clinical Efficacy of Attention Bias Modification Treatment for Anxiety Disorders. Depression and Anxiety, 32(6), 383–391. 10.1002/da.22344 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linetzky M, Pettit JW, Silverman WK, Pine DS, & Bar-Haim Y (2020). What Drives Symptom Reduction in Attention Bias Modification Treatment? A Randomized Controlled Experiment in Clinically Anxious Youths. Clinical Psychological Science, 8(3), 506–518. 10.1177/2167702620902130 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lipp OV, & Derakshan N (2005). Attentional bias to pictures of fear-relevant animals in a dot probe task. Emotion, 5(3), 365–369. 10.1037/1528-3542.5.3.365 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lisk S, Vaswani A, Linetzky M, Bar-Haim Y, & Lau JYF (2020). Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis: Eye-Tracking of Attention to Threat in Child and Adolescent Anxiety. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 59(1), 88–99.e1. 10.1016/j.jaac.2019.06.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu P, Taber-Thomas BC, Fu X, & Pérez-Edgar KE (2018). Biobehavioral Markers of Attention Bias Modification in Temperamental Risk for Anxiety: A Randomized Control Trial. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 57(2), 103–110. 10.1016/j.jaac.2017.11.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lonigan CJ, & Vasey MW (2009). Negative Affectivity, Effortful Control, and Attention to Threat-Relevant Stimuli. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 37(3), 387–399. 10.1007/s10802-008-9284-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macleod C (1995). Training selective attention: A cognitive-experimental technique for reducing anziety vulnerability: Training selective attention: A cognitive-experimental technique for reducing anziety vulnerability. 1st World Congress of Behavioural & Cognitive Therapies, 118. [Google Scholar]

- MacLeod C, & Mathews A (2012). Cognitive bias modification approaches to anxiety. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 8(1), 189–217. 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032511-143052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacLeod C, Mathews A, & Tata P (1986). Attentional bias in emotional disorders. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 95(1), 15–20. 10.1037/0021-843X.95.1.15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacLeod C, Rutherford E, Campbell L, Ebsworthy G, & Holker L (2002). Selective attention and emotional vulnerability: Assessing the causal basis of their association through the experimental manipulation of attentional bi as. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 111(1), 107–123. 10.1037/0021-843X.111.1.107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall PJ, Reeb BC, & Fox NA (2009). Electrophysiological responses to auditory novelty in temperamentally different 9-month-old infants. Developmental Science, 12(4), 568–582. 10.1111/j.1467-7687.2008.00808.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maslowsky J, Mogg K, Bradley BP, McClure-Tone E, Ernst M, Pine DS, & Monk CS (2010). A Preliminary Investigation of Neural Correlates of Treatment in Adolescents with Generalized Anxiety Disorder. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology, 20(2), 105–111. 10.1089/cap.2009.0049 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathews A, & MacLeod C (2002). Induced processing biases have causal effects on anxiety. Cognition and Emotion, 16(3), 331–354. 10.1080/02699930143000518 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McDermott JM, Perez-Edgar K, Henderson HA, Chronis-Tuscano A, Pine DS, & Fox NA (2009). A history of childhood behavioral inhibition and enhanced response monitoring in adolescence are linked to clinical anxiety. Biological Psychiatry, 65(5), 445–448. PubMed. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.10.043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNally RJ (2019). Attentional bias for threat: Crisis or opportunity? Clinical Psychology Review, 69, 4–13. 10.1016/j.cpr.2018.05.005 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Mogg K, & Bradley BP (2016). Anxiety and attention to threat: Cognitive mechanisms and treatment with attention bias modification. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 87, 76–108. 10.1016/j.brat.2016.08.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mogg K, Wilson KA, Hayward C, Cunning D, & Bradley BP (2012). Attentional biases for threat in at-risk daughters and mothers with lifetime panic disorder. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 121(4), 852–862. 10.1037/a0028052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monk CS, Telzer EH, Mogg K, Bradley BP, Mai X, Louro HMC, Chen G, McClure-Tone EB, Ernst M, & Pine DS (2008). Amygdala and Ventrolateral Prefrontal Cortex Activation to Masked Angry Faces in Children and Adolescents With Generalized Anxiety Disorder. Archives of General Psychiatry, 65(5), 568–576. 10.1001/archpsyc.65.5.568 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montagner R, Mogg K, Bradley BP, Pine DS, Czykiel MS, Miguel EC, Rohde LA, Manfro GG, & Salum GA (2016). Attentional bias to threat in children at-risk for emotional disorders: Role of gender and type of maternal emotional disorder. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 25(7), 735–742. 10.1007/s00787-015-0792-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morales S, Brown KM, Taber-Thomas BC, LoBue V, Buss KA, & Pérez-Edgar KE (2017). Maternal anxiety predicts attentional bias towards threat in infancy. Emotion, 17(5), 874–883. 10.1037/emo0000275 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morales S, Pérez-Edgar KE, & Buss KA (2015). Attention Biases Towards and Away from Threat Mark the Relation between Early Dysregulated Fear and the Later Emergence of Social Withdrawal. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 43(6), 1067–1078. 10.1007/s10802-014-9963-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morales S, Taber-Thomas BC, & Pérez-Edgar KE (2017). Patterns of attention to threat across tasks in behaviorally inhibited children at risk for anxiety. Developmental Science, 20(2), e12391. 10.1111/desc.12391 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muris P, van Brakel AML, Arntz A, & Schouten E (2011). Behavioral Inhibition as a Risk Factor for the Development of Childhood Anxiety Disorders: A Longitudinal Study. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 20(2), 157–170. 10.1007/s10826-010-9365-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nozadi SS, Troller-Renfree S, White LK, Frenkel T, Degnan KA, Bar-Haim Y, Pine D, & Fox NA (2016). The Moderating Role of Attention Biases in understanding the link between Behavioral Inhibition and Anxiety. Journal of Experimental Psychopathology, 7(3), 451–465. 10.5127/jep.052515 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Edgar K, Bar-Haim Y, McDermott JM, Chronis-Tuscano A, Pine DS, & Fox NA (2010). Attention biases to threat and behavioral inhibition in early childhood shape adolescent social withdrawal. Emotion (Washington, D.C.), 10(3), 349–357. 10.1037/a0018486 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Edgar K, Reeb-Sutherland BC, McDermott JM, White LK, Henderson HA, Degnan KA, Hane AA, Pine DS, & Fox NA (2011). Attention Biases to Threat Link Behavioral Inhibition to Social Withdrawal over Time in Very Young Children. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 39(6), 885–895. 10.1007/s10802-011-9495-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pergamin-Hight L, Naim R, Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ, van IJzendoorn MH, & Bar-Haim Y (2015). Content specificity of attention bias to threat in anxiety disorders: A meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review, 35, 10–18. 10.1016/j.cpr.2014.10.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pettit JW, Bechor M, Rey Y, Vasey MW, Abend R, Pine DS, Bar-Haim Y, Jaccard J, & Silverman WK (2020). A Randomized Controlled Trial of Attention Bias Modification Treatment in Youth With Treatment-Resistant Anxiety Disorders. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 59(1), 157–165. 10.1016/j.jaac.2019.02.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pittig A, Treanor M, LeBeau RT, & Craske MG (2018). The role of associative fear and avoidance learning in anxiety disorders: Gaps and directions for future research. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 88, 117–140. 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2018.03.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price RB, Greven IM, Siegle GJ, Koster EHW, & De Raedt R (2016). A novel attention training paradigm based on operant conditioning of eye gaze: Preliminary findings. Emotion, 16(1), 110–116. 10.1037/emo0000093 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price RB, Wallace M, Kuckertz JM, Amir N, Graur S, Cummings L, Popa P, Carlbring P, & Bar-Haim Y (2016). Pooled patient-level meta-analysis of children and adults completing a computer-based anxiety intervention targeting attentional bias. Clinical Psychology Review, 50, 37–49. 10.1016/j.cpr.2016.09.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reeb-Sutherland BC, Vanderwert RE, Degnan KA, Marshall PJ, Pérez-Edgar K, Chronis-Tuscano A, Pine DS, & Fox NA (2009). Attention to novelty in behaviorally inhibited adolescents moderates risk for anxiety. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 50(11), 1365–1372. 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2009.02170.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodebaugh TL, Scullin RB, Langer JK, Dixon DJ, Huppert JD, Bernstein A, Zvielli A, & Lenze EJ (2016). Unreliability as a threat to understanding psychopathology: The cautionary tale of attentional bias. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 125, 840–851. 10.1037/abn0000184 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salum GA, Petersen CS, Jarros RB, Toazza R, DeSousa D, Borba LN, Castro S, Gallegos J, Barrett P, Abend R, Bar-Haim Y, Pine DS, Koller SH, & Manfro GG (2018). Group Cognitive Behavioral Therapy and Attention Bias Modification for Childhood Anxiety Disorders: A Factorial Randomized Trial of Efficacy. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology, 28(9), 620–630. 10.1089/cap.2018.0022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandstrom A, Uher R, & Pavlova B (2020). Prospective Association between Childhood Behavioral Inhibition and Anxiety: A Meta-Analysis. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 48(1), 57–66. 10.1007/s10802-019-00588-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sequeira SL, Rosen DK, Silk JS, Hutchinson E, Allen KB, Jones NP, Price RB, & Ladouceur CD (2021). “Don’t judge me!”: Links between in vivo attention bias toward a potentially critical judge and fronto-amygdala functional connectivity during rejection in adolescent girls. Developmental Cognitive Neuroscience, 49, 100960. 10.1016/j.dcn.2021.100960 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shechner T, & Bar-Haim Y (2016). Threat Monitoring and Attention-Bias Modification in Anxiety and Stress-Related Disorders. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 25(6), 431–437. 10.1177/0963721416664341 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shechner T, Rimon-Chakir A, Britton JC, Lotan D, Apter A, Bliese PD, Pine DS, & Bar-Haim Y (2014). Attention Bias Modification Treatment Augmenting Effects on Cognitive Behavioral Therapy in Children With Anxiety: Randomized Controlled Trial. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 53(1), 61–71. 10.1016/j.jaac.2013.09.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiffrin RM, & Schneider W (1977). Controlled and automatic human information processing: II. Perceptual learning, automatic attending and a general theory. Psychological Review, 84(2), 127–190. 10.1037/0033-295X.84.2.127 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor CT, Aupperle RL, Flagan T, Simmons AN, Amir N, Stein MB, & Paulus MP (2014). Neural correlates of a computerized attention modification program in anxious subjects. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, 9(9), 1379–1387. 10.1093/scan/nst128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Telzer EH, Mogg K, Bradley BP, Mai X, Ernst M, Pine DS, & Monk CS (2008). Relationship between trait anxiety, prefrontal cortex, and attention bias to angry faces in children and adolescents. Biological Psychology, 79(2), 216–222. 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2008.05.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teng M-H, Hou Y-M, Chang S-H, & Cheng H-J (2019). Home-delivered attention bias modification training via smartphone to improve attention control in sub-clinical generalized anxiety disorder: A randomized, controlled multi-session experiment. Journal of Affective Disorders, 246, 444–451. 10.1016/j.jad.2018.12.118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Troller‐Renfree SV, Buzzell GA, Bowers ME, Salo VC, Forman‐Alberti A, Smith E, Papp LJ, McDermott JM, Pine DS, Henderson HA, & Fox NA (2019). Development of inhibitory control during childhood and its relations to early temperament and later social anxiety: Unique insights provided by latent growth modeling and signal detection theory. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 60(6), 622–629. 10.1111/jcpp.13025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Troller-Renfree SV, Buzzell GA, Pine DS, Henderson HA, & Fox NA (2019). Consequences of not planning ahead: Reduced proactive control moderates longitudinal relations between behavioral inhibition and anxiety. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 58(8), 768–775.e1. 10.1016/j.jaac.2018.06.040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valadez EA, Morales S, Buzzell GA, Troller-Renfree SV, Henderson HA, Chronis-Tuscano A, Pine DS, & Fox NA (2022). Development of Proactive Control and Anxiety Among Behaviorally Inhibited Adolescents. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry 10.1016/j.jaac.2022.04.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Valadez EA, Troller-Renfree SV, Buzzell GA, Henderson HA, Chronis-Tuscano A, Pine DS, & Fox NA (2021). Behavioral Inhibition and Dual Mechanisms of Anxiety Risk: Disentangling Neural Correlates of Proactive and Reactive Control. JCPP Advances, 1(2), e12022. 10.1002/jcv2.12022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Bockstaele B, Verschuere B, Tibboel H, De Houwer J, Crombez G, & Koster EHW (2014). A review of current evidence for the causal impact of attentional bias on fear and anxiety. Psychological Bulletin, 140(3), 682–721. 10.1037/a0034834 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White LK, Britton JC, Sequeira S, Ronkin EG, Chen G, Bar-Haim Y, Shechner T, Ernst M, Fox NA, Leibenluft E, & Pine DS (2016). Behavioral and neural stability of attention bias to threat in healthy adolescents. NeuroImage, 136, 84–93. 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2016.04.058 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White LK, Degnan KA, Henderson HA, Pérez-Edgar K, Walker OL, Shechner T, Leibenluft E, Bar-Haim Y, Pine DS, & Fox NA (2017). Developmental Relations Among Behavioral Inhibition, Anxiety, and Attention Biases to Threat and Positive Information. Child Development, 88(1), 141–155. 10.1111/cdev.12696 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White LK, McDermott JM, Degnan KA, Henderson HA, & Fox NA (2011). Behavioral inhibition and anxiety: The moderating roles of inhibitory control and attention shifting. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 39(5), 735–747. 10.1007/s10802-011-9490-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White LK, Sequeira S, Britton JC, Brotman MA, Gold AL, Berman E, Towbin K, Abend R, Fox NA, Bar-Haim Y, Leibenluft E, & Pine DS (2017). Complementary Features of Attention Bias Modification Therapy and Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy in Pediatric Anxiety Disorders. American Journal of Psychiatry, 174(8), 775–784. 10.1176/appi.ajp.2017.16070847 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. (2019). ICD-11: International classification of diseases (11th revision).