Abstract

Objectives

Menstruation tracking digital applications (MTA) are a popular technology, yet there is a lacuna of research on how women use this technology for the management of PMS. Theoretical frameworks for understanding users’ experiences are also underdeveloped in this nascent field. The objectives of the study were therefore twofold, to propose a theoretical framework for understanding women's use of MTA and apply it to the analysis of users’ experiences in the management of PMS.

Method

A novel theoretical framework was proposed, informed by post-phenomenology, postfeminist healthism, feminist new materialism and digital health technologies as public pedagogy. This framework focuses analytic attention on affective relationships between subjectivity, bodily sensations, digital technology, and discourse. It was used to structure the analysis of five in-depth timeline interviews with women in Aotearoa New Zealand who experienced benefits from using MTA to manage PMS symptoms.

Results

Three pedagogical relationships were identified: a pedagogy of empowerment, where users learnt to control, predict and manage their PMS symptoms in line with healthism; a pedagogy of appreciation, where users learnt to understand their menstruating bodies as amazing, a valued part of them, and awe-inspiring that radically overturned past internalised stigma; and an ‘untrustworthy teacher’ who eroded this affirmative learning through inaccuracy, positioning users in dis-preferred categories, or being ‘creepy’.

Conclusions

MTA offers huge possibilities for challenging menstrual stigma that need to be nurtured, developed, and protected; and there are benefits for analysing MTA within wider scholarship on postfeminist healthism.

Keywords: Digital health, menstrual tracking, period tracking apps, personal informatics, premenstrual syndrome, post-phenomenology, postfeminism, healthism, postfeminist healthism, user experience

Introduction

Menstruation tracking digital applications (MTA) are regularly used by an estimated 200 million people worldwide.1 Users interact with MTA by inputting data from which they receive information with the promise of bodily prediction and control, particularly around fertility. Collectively, this technology has pedagogical potential in making the menstruating body knowable, yet research on users’ experiences is limited and barely exists for those using these apps for managing premenstrual syndrome (PMS). This absence is despite many apps offering the ability to track symptoms related to PMS, and PMS being experienced by many women over their lifetime. Theoretical frameworks for understanding users’ experiences are also underdeveloped, being scattered across disciplinary and epistemological orientations.

Seeking to extend the study of MTA both empirically and theoretically, this article presents an analysis of five users’ experiences of MTA for PMS management. The analysis is informed by a novel theoretical framework drawing on postfeminist healthism, critical public pedagogy, feminist new materialism and post-phenomenology which we use to examine user experience produced in relations between bodies, technologies and discourse.

Menstruation tracking apps

Menstruation tracking apps (MTA) are an important part of the women's health app market, with revenue projected to reach US$243.80M in 2022.2 MTA are usually understood as a women's health issue, although not all women menstruate and not all menstruators are women; MTA are also known as ‘period tracking’ apps and ‘fertility tracking’ apps. In this article, we use the terminology of menstruation tracking apps in recognition that they track more than fertility or periods, such as PMS symptoms. MTAs are a relatively new addition to digital app technology. For example, in 2014 Apple now famously launched a health tracker without the function for women to track their periods and it was in 2018 before the U.S. Food and Drug Administration announced the approval of the first mobile app for contraception.3

Given this late start, the development and use of MTA have been exponential. MTA are amongst the most popular mHealth applications,4 with at least 220 available English-language MTA on Google Play Store, and 250 on Apple App Store,1 generating over 2.82M active user downloads a month, with the most popular apps, Flo (2 M) and Clue (400 k), dominating the market.5

MTA are marketed as tools for managing fertility by predicting ovulation; more broadly, they offer the promise of health management, bodily prediction, control, and empowerment through self-management of the body.6 For example, Flo's description states ‘take full control of your health with the app’,7 Clue states ‘Clue is designed to help you stay informed and make empowered health choices’8; while Della Bianca9 showed that MTA promoters connect MTA with multiple constructs of empowerment.

Research on users’ experiences suggests that users’ motivations map onto these hoped-for outcomes. Research on users’ experiences has rapidly expanded, with a developing body of work predominantly using interview methods,10–16 along with surveys 17 or autoethnography,18 a multi-method approach,19 questionnaires1 and systematic or scoping reviews.4,20 These studies all identify user benefits related to understanding and prediction of their bodies, from which they might better manage their lives (relating to a wide range of life management, including trying to conceive, avoiding pregnancy, communication with healthcare professionals, planning work schedules, social events, or holidays). These studies also suggest that MTA are experienced as empowering through enhanced understanding of their body and in providing a safe, shame-free place to learn about menstruation. As such, MTA offer a timely digital intervention against embedded cultural stigma of menstruation that aligns with new visibility of menstruation and period positivity.21

However, scholars question notions of women's empowerment through MTA use. The first set of concerns focus on data management and design development. Users input a range of intimate data, which may include the onset of bleeding, quality of blood flow, details of cervix mucus, sexual activity and frequency of orgasms, emotional states, medications taken, temperature, regularity of dieting or weighing, and other health issues. A range of studies raise data privacy and security concerns on what this information is used for, by whom and with how much consent.22–29 These privacy concerns sit alongside questions around accuracy 1,30,31 the lack of health professional or user involvement in design development5,32 and the user's labour involved in data inputting.16,29

The second set of interrelated concerns focuses on the regulatory power of MTA in producing particular understandings of the menstruating body. Studies raise concerns about how MTA might reduce women's emotional, physical, social, sexual and psychological lives to biological processes and monogamous, heteronormative fertility 3,9,11,33 their potential to disassociate women from their own embodied knowledge through outsourcing to digital health technology9; and the reproduction of stigma through constructing menstruation as a problem to be solved, something shameful that needs ‘discreet’ management, or an aspect of women's ‘unruly’ bodies.3,6,14,16,18,19,34–36 Significantly, multiple analyses have questioned how MTA construct menstrual cycle regularity as a measure of good health and ‘normal’ functioning, which excludes body diversity.3,6,19,32,33

Less work has focused on users’ experiences of regulation, but combined, they show a pattern in which users experience positive feelings such as satisfaction or even joy when the apps categorise their cycle as normal or healthy, or when they successfully use MTA to conceive. While worry, anxiety, distress, pain and frustration characterise the experiences of those who fail to conceive when desired or who have their cycles categorised as irregular (and thus problematic). 10,13,15,17,37 Such research highlights the productive power of MTA; maps onto research showing that digital health technologies stimulate strongly-felt responses38 and raises questions about the nature of the empowerment on offer, since those whose bodies are non-normative within the construct of the app may be excluded or distressed by MTA use.

MTA make visible internal bodily processes, not just revealing what was previously hidden, but rendering bodies knowable in particular ways. Andelsman10 for example, found that MTA taught users to understand their period as part of a cycle or series of phases. This knowledge was also tied to action, since the apps ‘materialise invisible processes of the cycle in ways that can be acted upon’ (Andelsman,10 p. 54). Similarly, Epstein et al.19 and Ford et al.11 found that women adjusted their thoughts and behaviours in response to feedback from MTAs; while Lupton's16 analysis of women's health and fitness apps more generally, described these technologies as taking ‘an overtly pedagogical approach, suggesting that their use will help people learn more about their bodies, which in turn will impel the desired behaviour change or habitual practices’ (Lupton,16 p. 984). App promoters also construct apps in relation to ‘multiple “learning regimes”’ (Della Bianca,9 p. 72). In this study, we extend such inquiry to examine what kind of pedagogy is communicated to those using MTA to manage symptoms related to PMS.

Premenstrual syndrome

PMS refers to distressing psychological and physical symptoms that occur during the luteal phase of the menstrual cycle, experienced just before menses. A meta-analysis gives a worldwide pooled prevalence for women of reproductive age at 47.8%, with a range from 12% (France) to 98% (Iran).39 This variability is attributed to cross-cultural differences in constructions of the menstruating female body, with Ussher and Perz,40 for example, arguing that some of the distress women experience with PMS is because changes in pre-menstrual embodiment map onto devalued cultural constructs of abject femininity related to being unruly and fat. Their work is one of a range of psychosocial interventions showing that targeting interpretations of PMS can reduce the severity of PMS.41 Given the productive power of MTA in structuring interpretations of menstruation, it is therefore likely that MTA can impact women's experiences of PMS.

Research on women's experiences of using MTA for PMS management is scant, despite most MTA including a feature for tracking emotions and physical sensations that explicitly or implicitly relate to PMS.3 A systematic review by Kalampalikis et al.4 of research evaluating MTA for promoting gynaecological health identified only one study that specifically focused on how MTA might affect PMS symptoms, which found that receiving a text message and email support through the Fitbit wristband produced a lower PMS score in comparison to those without intervention.42 The only other study specifically on PMS and MTA looked at the likelihood of usage.43 Other studies on MTA user experiences in general or which focused on the experiences of those using MTA specifically not for fertility management have included descriptions of MTA use for PMS management, 11,18,19 these report a shared pattern of participants describing using MTA to identify, interpret and attribute the intense emotions they felt during PMS to their hormones/menstrual cycle. To date, we can find no research specifically on women's experiences of using MTA for PMS management, we therefore ask, what are the experiences of women who use MTA to manage PMS, and how might we theorise these?

Theoretical framework

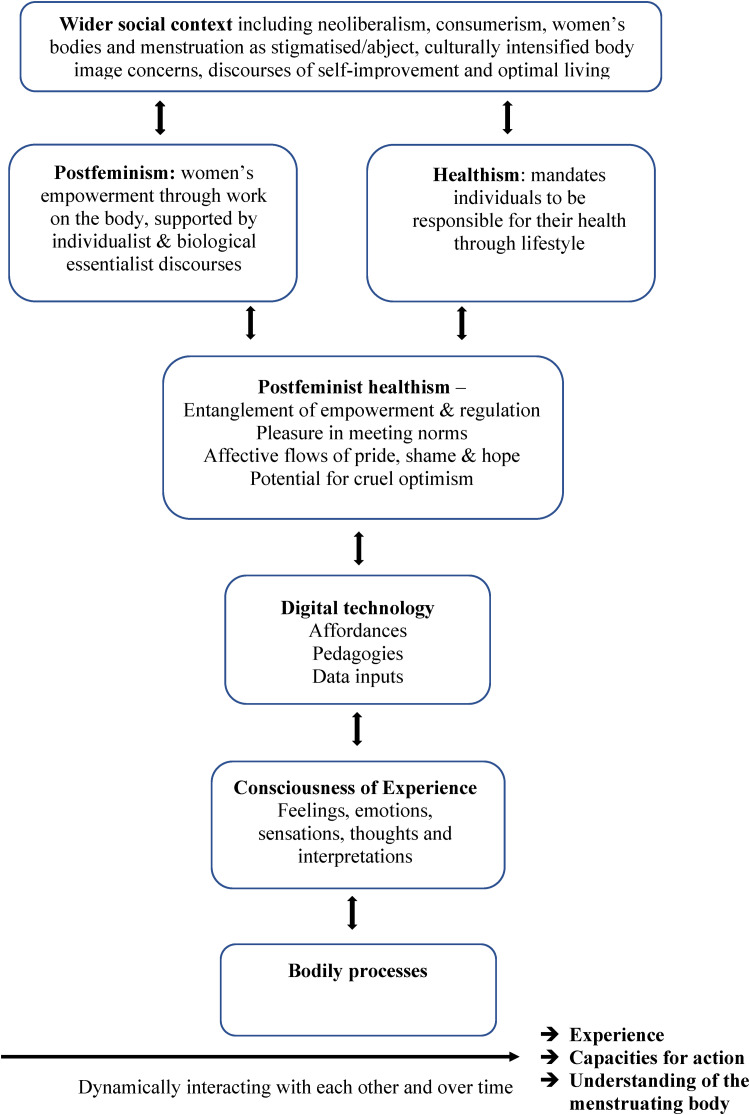

We draw on postfeminist healthism, critical public pedagogy, feminist new materialism, and post-phenomenology to propose a novel theoretical framework to address our research question and develop analysis of MTA, which we outline below, and summarise in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Outline of theoretical framework.

Postfeminist healthism

MTA are part of the quantified self-movement, although MTA differs from most other self-tracking because menstruators do not have control over their cycles.17 The quantified self-movement is premised on the idea of empowerment through the use of digital technologies that show previously hidden workings of the body. Here, empowerment is understood in terms of the ability to predict and control the body in relation to efficient life management and self-improvement.44,45

Self-tracking, as a practice of self-improvement and bodily control, is a tool of healthism, a dominant framing of health in neoliberal, capitalist economies, which mandates individuals to be responsible for their health, often through lifestyle or consumer practices.45–47

Healthism and self-tracking are highly gendered, and MTA are part of this ‘imperative toward self-examination, self-optimization, and personal responsibility’ (Ford et al.,11 p. 49). Healthism intersects with a postfeminist sensibility, a gendered form of neoliberalism that centres the body – and work on the body – as a site of identity and empowerment for women.48 The outcome is a ‘postfeminist healthism’ where the postfeminist imperative to work on the body to meet cultural ideals of femininity intersects with healthism's obligations to work on one's body for health.47

Postfeminist healthism offers a theoretical framework predicated on poststructuralist constructs of power as productive, disciplinary and diffuse, through which flow desire and affect that structure subjectivity and action. Postfeminist healthism offers analysts a framework for thinking about the complexities of how ideas of women's healthy bodies are produced, circulated, and with what effects. Current scholarship highlights (1) how the language of feminism and empowerment elicits women's engagement in regulatory, consumer-oriented, practices of the body; (2) that women's experiences of empowerment may be related to the pleasures of successfully attaining particular outcomes (e.g. a sexy body) but that these desired outcomes are structured by cultural norms that are not of their own making; (3) that desires to meet norms occur through an affective structure of digital health involving a range of feelings and emotions, including pride, shame and hope; (4) that postfeminism promises enhanced living but may direct desires towards that which is toxic or unattainable; and (5) that biological essentialism can be used to account for women's choices, justifying traditional gender norms.47,49–51

Digital technologies often reflect a postfeminist sensibility,47–49,51–53 but we can find no work that explicitly links analysis of MTA with postfeminism, despite postfeminist tropes being evident. For example, in how digital health technologies frame consumption as feminist37 and empowerment within dominant modes of neoliberal capitalism11; the biological essentialism of the ‘hormonal imperative’3,11; and, as discussed above, the entanglement of empowerment and regulation. We argue that postfeminist healthism provides a conceptual framework for connecting these elements of MTA.

Digital health technologies as public pedagogy

Public pedagogies occur in publicly accessible sites at the intersections of health and education outside of institutional systems like schools54 (Rich and Miah, 2014). Digital health apps are important sites for public pedagogies as people learn about their own and others’ bodies. Rich and Miah54 direct analytic attention to the pedagogical processes (rather than analysis of content) that occur in app use, and how these occur in relations between embodiment, technology, and discourse; including postfeminist sensibility.53 Della Bianca9 (p. 75) also highlights research describing fertility tracking apps as a biopedagogy, and calls for scholarship that offers a nuanced analysis of the dynamics between ‘bodies, learning, and technologies’.

Feminist new materialism

Relations with technology are central to feminist new materialism, which conceptualises users’ engagement with technology as mutually co-constitutive processes in which bodies, technologies, discourse, affect, feelings and emotions dynamically intra-act1 over time, enabling particular capacities for action.16,49,55,56 This approach is useful in exploring how menstruating bodies are rendered knowable10 and directs analytic attention to the ‘lively’ nature of technology as it dynamically interacts with users.16,38

Post-phenomenological analysis

Postfeminist healthism, critical public pedagogy and feminist new materialism are critical approaches underpinned by epistemologies that decenter the person. This is in contrast to phenomenology whose primary unit of analysis is the person and their consciousness of experience. However, phenomenological approaches share with the critical approaches outlined above, recognition of embodied knowledge and the role of affect, feelings and emotions in this knowing, ‘our feelings color the world and confer reality’ (Russell,57 p. 68). And both critical approaches and phenomenology connect knowledge to action, ‘feeling serves the function of a potential preparation for an act’ (Russell,57 p. 69). These shared interests, however, were not enough to bridge epistemological divides until the recent development of post-phenomenology, which connects insights from critical approaches to the study of experience.

Post-phenomenology is a diverse literature, and here we draw on Ash and Simpson,58,59 who theorise consciousness of experience2 as an emergent relation with the world rather than the product of a subject directing attention to it. This orientation decentres the subject by paying attention to the dynamic forming of relations enabled by the vibrancy (or liveliness) of the non-human as it intra-acts with human bodies in a dynamically unfolding process: ‘much of the phenomenon known as “human consciousness” does not take place “in” the bodies of the human but “with” the dense scaffolding of things that enables and shapes human thought’. 58 (p.62) From this perspective, MTA are part of this scaffolding.

Drawing our theoretical framework together, postfeminist healthism enables a nuanced analysis of empowerment/regulation, and attention to the dynamics between affect and norms; it also provides the discursive backdrop within which learning processes may occur through interaction with the app as a public pedagogy. Feminist new materialism draws analytic attention to how the menstruating body is produced through human and nonhuman relationships, and post-phenomenology enables analytic attention to be paid to individual experience while recognising that this experience is produced through ongoing human–non-human relations. All four elements of our theoretical approach point to the importance of understanding knowledge as an embodied process within which flows of affect may form feelings and emotions3, and from which particular capacities for action are enabled. We present this as a novel, coherent and fruitful theoretical framework for the analysis of user experiences MTA use for PMS management.

Method

Study design

In-depth interviews using a timeline graph and semi-structured questions with five women living in Aotearoa New Zealand who used MTA for the management of PMS.

Recruitment

Advertisements for the study were posted on the Facebook pages of author two (KP) and a menstruation charity. Inclusion criteria were 18 years of age or over, identify as a woman, and who use MTA for the management of PMS.

Data collection

A timeline graph was used to elicit rich data on experiences that occur over a period of time.60 Participants were asked to complete a simple chart where the x-axis represented time, and the y-axis emotions, they were otherwise free to create a chart that was meaningful for them. Participants were asked about their timelines through a semi-structured online interview.

Ethics

Ethical approval was gained by the Massey University Southern Board Human Ethics Committee. Ethical issues related to the sensitivity of this topic, addressing this, we enhanced participants’ agency by inviting them to review the interview questions and complete the timeline before the interview; detailed information on the study was given, and written consent was gained. The interviewer (KP) used her counsellor training to create a safe space as well as monitor for any signs of distress during the interview. Participants were given a time from which they could withdraw from the study and permission was sought for their anonymised interview transcripts to be uploaded onto a data archive. All interviews were finished with questions about a positive experience to ensure that participants left without discomfort. Information on appropriate helplines was given.

Method of data analysis

The study developed a method of analysis based on the theoretical framework. In line with phenomenological analysis, analysis occurred in several stages, each designed to create a more conceptual analysis, moving from descriptive to interpretive codes, collating interpretive codes into themes, and then bringing together several themes into superordinate themes. Addressing phenomenological principles of idiographic analysis, we analysed each participant's transcript separately before considering crosscutting themes.61

We worked iteratively on the analysis, both separately and collaboratively, seeking to stay close to the data to provide an account of the experiences of women who use MTA to manage PMS. Attention was paid to the relationality of experience in terms of how they were mediated through technology, bodies, subjectivity and associated affective flows between the human and nonhuman. During analysis, we saw how learning was a core element of the participants’ experience, this led us to consider MTA as a public pedagogy. Similarly, participants’ descriptions of MTA as empowering orientated us to how postfeminist healthism might facilitate analysis. This drawing on theory to develop interpretation of participants’ experiences is in line with psychological phenomenological analysis.62

A range of standard quality criteria for qualitative analysis were also employed, including reflexivity. One author had used these apps positively for PMS management, and the other author originally oriented towards a critique of the regulatory power of MTA. During analysis, we reflected on our different positionalities to explore alternative perspectives and ground our analysis in the data.

Participants

Participants were aged between 27 and 35 years, three used the app Clue, and two used Flo. All were identified as having PMS and as having found MTA useful in its management. All resided in Aotearoa New Zealand, a democratic, neoliberal economy, where healthism is a dominant discourse of health.63 Aotearoa New Zealand is also a highly digitalised society (93% of the population of just under 5 million own a smartphone), with high levels of migration (approximately 20% of the total population).64 It has a settler colonial structure, which historically imposed a European-Christian framing of menstruation as shameful onto Māori, the indigenous people whose matauranga Māori (Māori knowledge) framed menstruation as tāpu (sacred).65 In line with our phenomenological approach, below we give short histories of each participant's MTA use, before presenting the crosscutting themes of the analysis.

Sam (Korean, age 30) began using an MTA at age 17, after her regular, distress-free cycle changed and she experienced irregular menses, fluctuating moods, and painful cramping, for which she was prescribed hormonal treatments with limited success. When she got her first iPhone, the app store suggested an MTA, and she downloaded it because she ‘thought it would be fun to track it’. She has ‘loved it ever since’, especially enjoying the ability to assess how ‘normal’ her cycle is, attribute mood changes to hormones, and act on this information, including communication with her healthcare provider.

Kyra (Czech, age 29) used MTA from around age 24, shifting from pen and paper tracking to an app for convenience. She was motivated to track for fertility because her cycle was variable and because she experienced PMS symptoms that were ‘pretty bad’. She found the app convenient and helpful to see patterns in her cycle including PMS experiences and external influences on her cycle, particularly family stresses.

Amanda (Czech, age 35) started using an MTA at age 33 to support conception by tracking her ovulation. In her earlier years, her periods had been ‘easy, not painful’, but when she stopped her contraception, they became irregular which worried her because ‘something changed and I couldn't pinpoint why’. She used the app to log her symptoms, track her cycle, and to understand her body's ‘normal and natural cycle’. This information helped her to plan her life and communicate with her healthcare provider. Despite worries about data privacy, she has increased engagement with the app and pays for a premium subscription.

Anna (New Zealand European/Pākehā, age 27) described a history of painful menstruation. When she got an IUD fitted the symptoms worsened, so she used an MTA to help manage them. She has used the app for over one year to record her psychological and physical symptoms, and prepare for when her bleeding and cramps might start. This involves managing her work calendar, stocking up on tampons and medicine, and avoiding social events.

Lucy (New Zealand European/Pākehā, age 35) started using an MTA approximately eight years ago when she stopped taking oral contraception with a future intention of getting pregnant. She used the app to identify when she was ovulating, and also to gain a better sense of her natural cycle. She found tracking easy, liked the period reminders, and the opportunity to track a range of information to help her ‘figure out why you are feeling more emotional’. Lucy used the app consistently for six years except during pregnancy, when she switched to a pregnancy tracking app which she was offered by her MTA on detecting pregnancy.

Analysis

We present three superordinate themes that conceptualise MTA usage as a pedagogy of empowerment, a pedagogy of appreciation, and as an untrustworthy relationship. The first two themes highlight the way the MTA were experienced as an affirmative pedagogy, where the participants learnt to understand their cycles in ways that created feelings of empowerment and appreciation of their bodies. The third theme shows how this relationship could be undermined by positioning users in dis-preferred categories, inaccuracy, or being ‘creepy’. See table one for a summary of key findings (Table 1).

Table 1.

Overview of findings.

| Pedagogies: The lessons learnt | Feelings generated about the self | Experience of the technology | Wider discourses | Technological affordances | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pedagogy of empowerment | PMS is an understandable bodily process. PMS is part of a dynamic (normal/natural) hormonal cycle. Causes of PMS symptoms Knowledge of body processes. Bodily awareness and observation skills. The body can be predicted and planned around. PMS is transient and manageable. |

Empowerment. Feeling educated. Feeling in control. Self-efficacy. Self-determination. Self-compassion. Self-love. Confidence. Comfort. Peace. |

Informative. Nurturing. |

Healthism. Postfeminist healthism. Productive neoliberal body. Optimised body. Norms (and the desire to be ‘normal’). |

Notifications & pop-ups. Articles. Useful/accurate predictions. Question and answer features (paid). |

| Pedagogy of appreciation | Women’s bodily processes are: Amazing; Awe inspiring; To be admired and appreciated. |

Self-love. Body-appreciation. Body-love. Pride. Gratitude. Feeling special. Enjoyment. Integrated self-body. Excitement. Anticipation. |

Inspiring. Nurturing. |

Normally marginalised (feminist) celebratory/valued discourses of women’s bodies. Contrasted with dominant pedagogies of stigma and shame. |

Notifications & pop-ups. Articles. Anticipatory tone of predictions. |

| Untrustworthy teacher | Predictions are untrustworthy. Their bodies are broken/wrong. The app relationship is a commercial transaction. |

Invaded. Followed. Anxiety. Unsettled. Scared. Vulnerable. |

Untrustworthy. Creepy. Invasive. Unwanted. |

Wider misogyny and heterosexual relations. Menstrual cycle categorised as irregular. Norms (and the desire to be ‘normal’). |

Notifications & pop-ups. Advertising. Inaccurate predictions. Categorisations. |

Pedagogy of empowerment

Participants described the app as creating a pedagogical experience, delivering information on their menstrual cycle through which they learnt to understand their bodies differently. Kyra, for example, explained that ‘the app has got many resources, scientific articles explaining your cycle, explaining what's going on. So, I found that very informative’.

Delivering information that the women used to better understand their bodies created a pedagogy of empowerment, since it increased their sense of confidence, control and self-efficacy. Amanda, for example, described how learning was central to her experience of using MTA, explaining how in offering her ‘really interesting articles just about anything and everything’ she gained new knowledge about her body, ‘it's quite definitely changed the way I view my own cycle’. Sam also talked about learning to understand herself better, directly attributing this learning to using the app. Below she muses at the possibility of how different and ignorant she might have been without it:

I feel like I’ve learned more about my body and how it works and what its natural cycle is. And I think that the app has been very useful in doing that. So if I think about if I never was using the app then would I know some of the things I know?

Central to this learning was an understanding that menses was part of a cycle. The participants used this knowledge to interpret and predict their physiological and psychological experiences that they came to associate with PMS. Lucy, for example, said it was great being able to ‘figure out why you are feeling more emotional’, while Kyra described going on a learning journey through her use of the app, where she came to understand a period as part of a fluctuating hormonal cycle. She described a sense of empowerment from this knowledge, since her body now ‘makes more sense’. Similarly, Anna explained, ‘the positive side has been knowing and understanding more about my cycle’.

This knowledge also enhanced participants’ awareness of their embodied experiences. Sam, for example, explained that ‘the more subtle things became a lot more apparent’. This awareness allowed Sam to be more confident in her attributions for certain experiences, including how particular stresses impacted her cycle. This position of knowledge and enhanced awareness allowed the women to approach their PMS experiences in new ways that felt more affirmative. As Kyra explained:

I could really see the patterns, and the app helped me with that because I could track all my mood and all my energy levels, and clear patterns which I was seeing through and through. And it helped me to kind of understand that this is a normal process that I can work with rather than against it. So it made the whole process, especially before my period when it was painful, more enjoyable.

Kyra's extract described a pedagogy of empowerment in how the app rendered her body knowable in a new, affirmative way. This knowledge enabled a greater sense of connection between herself and her body that facilitated a new relationship of partnership ‘I can work with rather than against it’, so that even a painful experience could become ‘more enjoyable’.

Other affirmative affective experiences included feeling reassured that their experiences, however unpleasant, were normal. The app also enabled a sense of self-determination and self-efficacy when the predictive features allowed participants to organise their life in preferred ways, such as rescheduling activities they would find difficult when pre-menstrual, or planning analgesics, sanitary products, outfits or holidays.

Understanding why they were feeling in a particular way, being able to prepare, and knowing that difficult feelings and sensations would pass as part of a cycle, gave the participants feelings of ‘comfort’, (Anna), ‘peace’ (Kyra) and acceptance that, in turn, enabled self-compassion. Below, Lucy described how using the app helped her to ‘accept’ her experience of PMS, and from this place of both awareness and acceptance, to ‘be kind to yourself’:

Um, I think just a more with the whole, the PMS thing, I feel like using the app, if you are experiencing like grumpiness or sadness, or really irritable, it just, yeah, I can kind of look in the app and be like, okay, that makes sense [later in the interview] And so you can maybe accept that more, and not to try and let it take over, or whatever. I don't know, I don't think PMS is very easy to control. There is things that you can do to help it though. So whether you can maybe look at doing that, or if you can be aware of it, and then just be more understanding and I suppose be kind to yourself with that, you know.

In her talk of turning to the app for guidance ‘I can kind of look in the app and be like, okay, that makes sense’, Lucy also highlighted the dynamic flows between the women and technology, which was characterised by multiple directions of communication produced in intra-action between the women's embodied experiences and the affordances of the app. Participants had to regularly input a range of intimate data, they also initiated engagement when their embodied sensations created an impetus to consult the app to see if it would help interpret those experiences. These consultations could create feedback loops, where increased awareness of their embodied sensations created by the use of the app, in turn, increased the women's likelihood of turning to the app for information. At other times, the app initiated interactions, such as notifications inviting them to open the app for information. Further interaction occurred when participants were already using the app and it directed them to subsequent actions, such as clicking on a recommended article or buying a suggested product. Some (paid) features allowed a question and answer dynamic. As Amanda explained,

if there is a popup saying ‘Oh, would you like to know more about your findings? I would actually click “Yes”. And sometimes I would have that conversation with the machine or whoever you’re having conversation with. Or yeah, read some random article about something intriguing.

Kyra's extract below provides a further sense of this complex dynamic, where sometimes embodied feelings initiated a turn to the app, while at other times the app notified her, both of which created interactions between her and the app. For example, the app provided information she used to ‘educate’ herself, and through this education gain a sense of empowerment ‘this is normal, this is going to pass’. This relational dynamic between Kyra and her app had subsequent flows through her relations with other people, as well as feedback loops between her embodied knowing and the app ‘it makes me observe things more’:

I start to feel emotional or more drained or more negative during my PMS period. And with the app, I can see when I’m starting to feel that way, and I check with my app and I see that this is the time. And it's because of the hormones. Usually, at that time, the app gives me articles that I can read about this time. I can educate myself on what's going on hormonally in my body. And I know, okay, yes, this is this is okay, this is normal, this is going to pass. Or I check the app prior, and I know, okay, well, um, or the app gives me notifications. And it will give me “Oh, it looks like it's your PMS coming up”. And I know, okay, maybe I need to adjust my social week a little bit, or as I said postpone any important decisions or not get into conflicts or not try to resolve something that was bothering me the whole month … [later] Usually the app also tells me what I can expect. See, I have notifications set up where they tell me “Oh expect, I don't know, expect to have low energy levels today or expect this”. And it makes me observe things more.

The outcome of these multiple flows of communication was a dynamic, interactive relationship with the technology, where the app was experienced as forming a nurturing pedagogical relationship. A relationship, that in turn, allowed the user to nurture herself and engage with the world in ways that felt empowered. This form of empowerment was related to a sense of ‘control’, ‘education’ (Kyra), and active engagement with one's health (‘would you like to know more about your findings?’ I would actually click ‘Yes’ – Amanda), creating the added benefit of enabling our participants to position themselves as good health-citizens within postfeminist healthism.

Pedagogy of appreciation

A pedagogy of appreciation also occurred, where participants learnt to value menses and their menstrual cycle. Contrasted against both a cultural stigma of menstruation and participants’ own embodied experiences of menstruation as physically and emotionally difficult, the apps offered a reframing of menstruation as something to be appreciated. As Lucy explained ‘being able to use the app has made me feel more okay with, you know, having a period really’. The radical possibilities of the pedagogy of appreciation are evident in the following extract:

Amanda: I love it! I love it, when it gives you a notification saying, Oh, your cycle is around the corner. I love that.

Interviewer: What do you love about that?

Amanda: I don't know, it's exciting, I get curious. It's like let's get ready for this! [laughing].

Above, Amanda describe the app as creating a sense of excitement, of affirmative anticipation of menses, which elsewhere in the interview she contrasted to her previous feelings of being ‘scared’ and ‘freaking out’. This re-learning of what had been previously understood only negatively was deeply affirmative, and she exclaims, ‘I love it!’. This feeling of positive anticipation is powerful enough to maintain even in the face of knowing that what is ‘round the corner’ is a host of challenging experiences:

I might get cranky, or if I feel emotionally upset. You know, or I yeah, or just, I don't know, swelling boobs … but at the same time, I am kind of glad. I am kind of looking forward to my cycle by the time it's coming.

A pedagogy of appreciation was also described by Kyra, who contrasted her current feelings of empowerment with how she felt previously, where menstruation was so shameful that it was ‘traumatizing’, requiring a lot of work to ‘hide it as much as possible and pretend like nothing was happening’. Now she doesn't feel ashamed, and instead has learnt to appreciate her menstruating body:

I felt a sense of empowerment or control, a sense of understanding, possibly my self-love increased because I realized how amazing the woman's body is that it's able to do all these things and go through all these processes and that there is something special or unique about that … [later in the interview] made me be more proud that I’m a woman and that I want to be a woman and that I’m grateful for everything that's going on in my body. And I started liking this whole cycle process and I was really enjoying even the bleeding process because it made me feel like - yes, this is part of me, this is me and this is a phase that I need and I felt complete maybe.

Kyra's extract above describes pedagogical processes from using the app, including both the pedagogy of empowerment (‘I felt a sense of empowerment’) and the pedagogy of appreciation (‘my self-love increased because I realized how amazing the woman's body is’). The pedagogy of appreciation was associated with self-love, pride, gratefulness for her body, and bodily acceptance, and allowed an understanding of her body as ‘amazing’ and ‘special’. This highly affirmative orientation meant that even what might be regarded as unpleasant experiences such as bleeding, became accepted, valued, and integrated into her sense of self ‘this is part of me’.

Against a backdrop of stigma and shame, MTA use thus produced a powerful, alternative pedagogy of appreciation of the menstruating body and, by association, the person who menstruates. The associated affective flows were feelings of pride, self-love, excitement, awe and completeness; creating a radical shift in how participants previously understood their menstrual cycle, bodies and selves. Information and notifications were written in a way that made the onset of their periods, and even the challenging symptoms of PMS, something that could be anticipated affirmatively. Through dynamic interactions enabled by notifications, pop-ups, data entry, suggested reading, and useful predictions, the participants described an unfolding relationship with their app, a relationship akin to an inspiring, nurturing teacher, opening new possibilities of appreciation.

An untrustworthy teacher – turned out to be wrong and a little bit creepy

However, sometimes the app became a source of anxiety, undermining its pedagogies of empowerment and appreciation. Anxiety occurred when there was a mismatch between their own and their app's interpretation of their bodies. Sam, for example, described having PMS symptoms when the app told her it was not that time. Fearing that an unwanted pregnancy might explain this mismatch between her embodied and technological knowledge, Sam started to check the app, anxiously and repeatedly. She reflected that this anxiety occurred because she used the app ‘I think before, I don't know whether I would have even noticed it’. Kyra also described an unsettling experience which she attributed to a change in the way the algorithm worked to track ovulation, which ‘really threw me off’.

The app was also a source of anxiety when it positioned the women in dis-preferred identities. Anna and Lucy, for example, described losing their sense of ‘comfort’ (Anna) and ‘good feeling’ (Lucy) when their cycles were re-categorised from ‘normal’ to ‘irregular’, leading Anna to ask ‘what's wrong with my body’ and Lucy to wonder if her body was ‘broken’. The relationship participants had with their app was also damaged when communications were experienced as invasive or with too-obvious commercial intent. Below, Amanda gives an example when she described learning to ignore the app requests to log information about sexual experiences:

Amanda: when you start logging all these things, all these ads come up. And if I do get too many ads, I do get a little bit irritated. And I just either shut the notifications or even get rid of the app. Because then I feel like I am followed. It's creepy. And last thing I want [later in the interview] You know I had a conversation about some baby stuff. And then I have an ad for prolapse. I don't know like it's like a massage thing you put in your vagina. You know what I mean? This is like ‘why I’m getting this?’. So I think this is where I’m coming from. I don't like to log everything. I don't need to see every single ad that's available for every symptom I have.

Interviewer: Hmm, yeah, that sounds annoying to have ads like that pop up, especially when it's something so private.

Amanda: Yeah, it's a little bit creepy.

In response to the detailed logging that Anna's app prompted her to do, Anna received multiple advertisements. These advertisements are experienced as invasive: ‘all these ads’ ‘too many ads’ and ‘I don't need to see every single ad that's available for every symptom I have’. These multiple overtures are unwanted and too intimate ‘like a massage thing you put in your vagina’, giving Anna a sensation of being followed. Combined, the relationship was no longer affirmative, but ‘creepy’. The glamour of the protective friend in the palm of your hand – with whom Anna had ‘conversation’ – fell away to reveal itself as only wanting her intimate details for a commercial transaction.

In this third theme, then, a different kind of relationship emerges, one where the warm feelings previously elicited by the app are gone, replaced with feeling unsettled, anxious, and fearful. Afraid of the possibility of bodily failure, and of overexposure, ‘logging so many personal things into it a little bit scary’ as Amanda said. In these experiences, the participants were no longer positioned as the empowered figure of postfeminist healthism, but experienced vulnerability.

Conclusion

MTA offers a public pedagogy for women using these technologies to manage PMS. We identified two affirmative pedagogical relationships, of empowerment and of appreciation, which could be undermined through dis-preferred categorising and commercially-oriented interactions that felt creepy.

Our analysis supports previous findings that MTA teaches women about menstruation as a cycle and gives them a sense of empowerment through learning about, and attunement with, their bodies; the ability to predict and plan; an understanding of menstruation outside of shame-oriented discourses; and the ability to interpret difficult psychological experiences as normal, attributed to hormonal fluctuations, transient, and manageable.6,10,11,17,18 This manageability was also linked to pleasures of participating in neoliberal citizenship.11

We also supported findings showing how users disliked app-initiated interactions when experienced as invasive17 and that having one's cycle categorised as irregular was anxiety-provoking.10,13,15,17,37 Also, that users can find digital surveillance ‘creepy’ when unknown actors have information on them66 and may respond by withholding intimate information.11 We further extend these findings by showing that these outcomes occur within powerful pedagogical relationships. Further implications of these findings are that app developers might create more dialogical relationships with users regarding the information sent to them, for example, first asking, ‘would you like information on products to support your sexual health’.

The pedagogy of empowerment aligns with MTA scholarship showing how the promise of empowerment through knowledge, prediction and control can be realised for users. We show that these findings are also applicable to those using PMS management. But, informed by postfeminist healthism, our analysis suggests a nuanced interpretation of this empowerment – as interconnected with, rather than separate from, regulation; since users experienced empowerment when their app enabled them to understand themselves within normative discourses (e.g. as self-managing health citizens). Our analysis aligns with Ford et al.'s11 finding that MTA sit within, rather than offering lines of flight, from surveillance capitalism. This doubled entanglement of regulation and empowerment is a postfeminist trope, suggesting that future analysis of MTA would benefit from engagement with scholarship on postfeminist healthism.

We also suggest scholarship of postfeminism can be extended through consideration of MTA use and the pedagogy of appreciation. Users’ descriptions of self-love, self-compassion, a sense of completion, and excited anticipation (even for painful and difficult experiences related to PMS), had a distinctly different affective tone to previous research on postfeminist empowerment through work on the body. We consider these differences: In postfeminism, empowerment is often connected to a ‘cruel optimism’ that directs women's desires to work on their existing body and transform it to align with cultural ideals, even when these cultural ideals might be toxic (e.g., the thin ideal) or direct attention away from more affirmative, sustainable outcomes. But in the pedagogy of appreciation, something different happens. Rather than aligning women with cultural norms (that connect menstruation with stigma and shame, or which orient to the productive neoliberal body in healthism), our participants described learning an alternative, affirmative way of knowing the menstruating body that was connected to pride and awe. This form of appreciation-empowerment opened-up capacities to differently know and love the existing body (bleeding, painful, and awe-inspiring), rather than work on it with the hope of fixing it or making it loveable. This finding suggests new directions for research on postfeminism and body positivity.

The dual pedagogies of appreciation and empowerment suggest MTA holds the radical potential to challenge entrenched stigma of the menstruating body. In light of these findings, the undermining of this relationship is particularly problematic. We suggest that when apps shift from being inspiring to creepy teachers, they undermine users’ affirmative feelings towards their bodies in a wider stigmatising context where these feelings are hard to generate. Further, when apps turned out to be just another creep that women have to deal with, ‘creepy’ MTA adds to an already crowded landscape of on and offline misogyny.

Interpretivist qualitative research focuses on delineating the parameters within which the research can be considered and its transferability to other contexts. In relation to transferability, we highlight that menstruation is stigmatised in most cultures, and thus pedagogies of appreciation and empowerment are likely to be experienced as beneficial for many MTA users. We also suggest that combining our own findings with wider research on digital health,16,38 MTAs are likely to be experienced through affective and relational intra-actions between embodied sensations, digital technology and wider discourses. We also recognise the importance of cultural context shaping experience, and in considering the parameters of this research, we note that our study drew from participants in a highly digitalised society, where postfeminism and healthism are dominant discourses, underpinned by neoliberalism. Our findings might therefore be most transferable to MTA users in contexts with these elements.

However, much of the theoretical framework could be transferable to a range of contexts should researchers use figure one to decide which elements might be relevant, adapted or added for their specific research site. In relation to the first element of our framework, the wider social context, we suggest considering the dominant social, political, and economic discourses, as well as those of women's bodies, menstruation, and what constitutes living a good life. In relation to the second and third tiers of the framework, namely postfeminism, healthism and postfeminist healthism, we highlight that these frameworks are transnational and so are likely to be relevant in many countries. One of the reasons why postfeminist healthism has such a global reach is because its core elements can be combined with local values in ways that make it attractive to those specific cultures (for further discussion of transnational postfeminism see Riley, Evans and Robson).49 We therefore advise researchers wanting to use our theoretical framework outside of the socio-political context of the current study, to review any research on postfeminism and/or healthism in their own or similar countries, from which to identify relevant elements. For example, Boshoff67 argues that patriarchy is an important element for South African scholarship of postfeminism.

We have shown that three kinds of pedagogical relationships can occur for women who use MTA to manage PMS, and a theoretical framework for understanding these. Given the similarities of experience across the five participants, and how these connect with dominant social discourses, we might expect findings to be transferable to larger studies with participants like ours, who as cis-gendered, heterosexual, and able-bodied, align with mainstream app constructions of normative users. The pedagogies we identify may also shape the experience of more diverse users of MTA, including sexual and other minorities, and this is an important direction for future research. We should also ask how MTA might be leveraged to offer pedagogies of empowerment and appreciation to diverse users. For example, supporting indigenous women to connect to indigenous perspectives of menstruation as sacred.

Where we suggest limits to the transferability of the present study is in relation to MTA users who do not identify as women. The pedagogy of appreciation was framed around the awesomeness of women's bodies. For those menstruators are not women, it is likely not be relevant, or might even be psychologically harmful since it ties menstruation to womanhood. And while the findings of this study showed that using MTA changed our participants’ interpretation of PMS in ways that led to a greater sense of well-being, the study did not examine if levels of pain changed, nor how cultural differences in relation to pain might mediate this relationship. Future research could address these questions.

Overall we have shown that MTA may be considered a public pedagogy, and the benefit of looking at experience through a post-phenomenological epistemology informed by feminist new materialism that also considers how experience is produced through affective and relational intra-actions between embodied sensations, digital technology and wider discourses, including postfeminism. We offer our theoretical framework for future research on MTA, suggesting it has significant potential to be developed in the fields of critical digital health studies. Finally, we suggest that MTA offers huge possibilities for challenging menstrual stigma, and that future research in feminist technology studies of personal informatics might explore how the pedagogy of appreciation can be nurtured, developed, and protected.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Jessica Tappin for her comments on an earlier draft.

Barad (2007) uses ‘intra-action’ to highlight how any of these elements has agency to affect another element, creating relations of difference.

Which within phenomenology is known as ‘intentionality’.

We have spoken about affect, feelings and emotion without defining these terms because there are significant debates on what these might mean, which we do not have space for here. However, we align with the idea that while sometimes they are useful to distinguish, they inform each other and cannot be ontologically separated.

Footnotes

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iD: Sarah Riley https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6712-6976

Ethical approval: The ethics committee of Massey University approved this study (REC number: NOR21/11)

Contributorship: SR and KP researched literature, conceived the study, were involved in gaining ethical approval and (independently and collaboratively) iteratively conducted data analysis. KP was involved in participant recruitment and data collection. SR wrote substantial elements of the manuscript and developed the theoretical framework. Both authors reviewed and edited the manuscript and approved it for publication.

References

- 1.Karasneh RA, Al-Azzam SI, Alzoubi KH, et al. Smartphone applications for period tracking: rating and behavioural change among women users. Obstet Gynaecol Int 2020; 2020: 1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Statista. Contraception & Fertility Apps – Worldwide. https://www.statista.com/outlook/dmo/digital-health/ehealth/ehealth-apps/contraception-fertility-apps/worldwide (accessed 30 April 2022).

- 3.Kressbach M. Period hacks: menstruating in the big data paradigm. Television & New Media 2021; 22: 241–261. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kalampalikis A, Chatziioannou SS, Protopapas A, et al. Mhealth and its application in menstrual related issues: a systematic review. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care 2022; 27: 53–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Worsfold L, Marriott L, Johnson S, et al. Period tracker applications: what menstrual cycle information are they giving women? Women’s Health 2021; 17: 1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pichon A, Jackman KB, Winkler IT, et al. The messiness of the menstruator: assessing personas and functionalities of menstrual tracking apps. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2022; 29: 385–399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Flo. Period Tracker. FLO App. https://flo.health/menstrual-cycle/health/flo-app (no date, accessed 29 April 2022).

- 8.Clue. About Clue. https://helloclue.com/about-clue (no date, accessed 29 April 2022).

- 9.Della Bianca L. Configuring the body as a pedagogical site: towards a conceptual tool to unpack and situate multiple ontology is of the body in self-tracking apps. Learn Media Technol 2022; 47: 65–78. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Andelsman V. Materializing period-tracking with apps and the (re)constitution of menstrual cycles. Journal of Media and Communication Research 2021; 71: 54–72. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ford A, De Togni G, Miller L. Hormonal health: period tracking apps, wellness, and self-management in the era of surveillance capitalism. Engaging Science, Technology, & Society 2021; 7: 48–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grenfell P, Tilouche N, Shawe J, et al. Fertility and digital technology: narratives of using smartphone app ‘natural cycles’ while trying to conceive. Sociol Health Illn 2021; 43: 116–132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hamper J. Catching ovulation: exploring women’s use of fertility tracking apps as a reproductive technology. Body Soc 2020; 26: 3–30.33424415 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Karlsson A. A room of one’s own? Using period trackers to escape menstrual stigma. Nordicom Review 2019; 40: 111–123. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Levy J, Romo-Aviles N. “A good little tool to get to know yourself a bit better”: a qualitative study on user’s experiences of app-supported menstrual tracking in Europe. BMC Public Health 2019; 19: 1213.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lupton D. Australian Women’s use of health and fitness apps and wearable devices: a feminist new materialism analysis. Feminist Media Studies 2020; 20: 993–998. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gambier-Ross K, McLernon DJ, Morgan HM. A mixed methods exploratory study of women’s relationships with and uses of fertility tracking apps. Digital Health 2018; 4: 1–15. https://doi.org/2055207618785077 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Homewood S, Karlsson A, Vallgårda A. Removal as a method: a fourth wave HCI approach to understanding the experience of self-tracking. In Proceedings of the 2020 ACM designing interactive systems conference 2020, Eindhoven, Netherlands, 6–10 July 2020, paper no. 9781450369749, 1779–1791. New York, NY. 10.1145/3357236.3395425 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Epstein DA, Lee NB, Kang JH, et al. Examining menstrual tracking to inform the design of personal informatics tools. Proc SIGCHI Conf Hum Factor Comput Syst 2017; 2: 6876–6888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Earle S, Marston HR, Hadley R, et al. Use of menstruation and fertility app trackers: a scoping review of the evidence. BMJ Sexual & Reproductive Health 2021; 47: 90–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wood JM. Visible bleeding: the menstrual concealment imperative. In: Bobel C, Winkler IT, Fahs B, et al. (eds). Handbook of critical menstruation studies. Singapore: Palgrave Macmillan, 2020, 319–336. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fox S, Specktor F. Hormonal advantage: retracing exploitative histories of workplace menstrual tracking. Catalyst: Feminism, Theory, Technoscience 2021; 7: 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hohmann-Marriott B. Periods as powerful data: user understandings of menstrual app data and information. New Media & Society, SAGE ahead of print August 2021. 10.1177/14614448211040245 [DOI]

- 24.Lupton D. Quantifying the body: monitoring and measuring health in the age of mHealth technologies. Crit Public Health 2013; 23: 393–403. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lupton D. Health promotion in the digital era: a critical commentary. Health Promot Int 2015; 30: 174–183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Novotny M, Hutchinson L. Data our bodies tell: towards critical feminist action in fertility and period tracking applications. Tech Commun Q 2019; 28: 332–360. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Privacy International. How menstruation apps are sharing your data, https://privacyinternational.org/long-read/3196/no-bodys-business-mine-how-menstruations-apps-are-sharing-your-data (2020, accessed 29 April 2022).

- 28.Rosato D. What your period tracker app knows about you. Consumer Reports, January 28, https://www.consumerreports.org/health-privacy/what-your-period-tracker-app-knows-about-you/ (2020, accessed 29 April 2022).

- 29.Siapka A, Biasin E. Bleeding data: the case of fertility and menstruation tracking apps. Internet Policy Review 2021; 10: 1–34. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hutcherson TC, Cieri-Hutcherson NE, Donnelly PJ, et al. Evaluation of mobile applications intended to aid in conception using a systematic review framework. Ann Pharmacother 2020; 54: 178–186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Moglia ML, Nguyen HV, Chyjek K, et al. Evaluation of smartphone menstrual cycle tracking applications using an adapted applications scoring system. Obstet & Gynaecol 2016; 127: 1153–1160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zwingerman R, Chaikof M, Jones C. A critical appraisal of fertility and menstrual tracking apps for the iPhone. Journal of Obstet Canada 2020; 42: 583–590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fox S, Epstein DA. Monitoring menses: design-based investigations of menstrual tracking applications. In Bobel C, Winkler IT, Fahs B, et al. (eds). The Palgrave handbook of critical menstruation stuies. Singapore: Palgrave Macmillan; 2020, 733–750. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Almeida T, Comber R, Balaam M. HCI and intimate care as an agenda for change in women’s health. In: Proceedings of the 2016 CHI conference on human factors in computing systems, San Jose, California, 7-12 May 2016, 2599–2611. New York, NY: Association for Computing Machinery. 10.1145/2858036.2858187. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Campo Woytuk N, Nilsson L, Liu M. Your period rules: design implications for period-positive technologies. In Extended abstracts of the 2019 CHI conference on human factors in computing systems (CHI EA ‘19), Glasgow, Scotland, 4-9 May 2019, paper no LBW0137, 1–6. New York, NY: Association for Computing Machinery. 10.1145/3290607.3312888 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Søndergaard MLJ, Hansen LK. Intimate futures: staying with the trouble of digital personal assistants through design fiction. In: Proceedings of the 2018 designing interactive systems conference, Hong Kong, China, 9–13 June 2018, 869–880. New York, NY: Association for Computing Machinery. 10.1145/3196709.3196766 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Della Bianca L. The cycle itself: menstrual cycle tracking as body politics. Catalyst: Feminism, Theory, Technoscience 2021; 7: 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lupton D. How does health feel? Towards research on the affective atmospheres of digital health. Digital Health 2017, 3:54–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Direkvand-Moghadam A, Sayehmiri K, Delpisheh A, et al. Epidemiology of premenstrual syndrome (PMS)-a systematic review and meta-analysis study. J Clin Diagn Res 2014; 8: 106–109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ussher JM, Perz J. Resisting the mantle of the monstrous feminine: women’s construction and experience of premenstrual embodiment. In Bobel C, Winkler IT, Fahs B, et al. (eds). The Palgrave handbook of critical menstruation studies. Singapore: Palgrave Macmillan; 2020: 215–231. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Han J, Cha Y, Kim S. Effect of psychosocial interventions on the severity of premenstrual syndrome: a meta-analysis. J Psychosom Obstet & Gynaecol 2014; 40: 176–184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nam SJ, Cha C. Effects of a social-media-based support on premenstrual syndrome and physical activity among female university students in South Korea. J Psychosom Obstet & Gynaecol 2020; 41: 47–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lee J, Kim J. Can menstrual health apps selected based on users’ needs change health-related factors? A double-blind randomized controlled trial. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2019; 26: 655–666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fox S, Howell N, Wong R, et al. Vivewell: speculating near-future menstrual tracking through current data practices. In Proceedings of the 2019 on designing interactive systems conference (DIS’19), San Diego, CA, 23–28 June 2019, 541–552. New York, NY: Association for Computing Machinery. 10.1145/3322276.323695 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lupton D. The digitally engaged patient: self monitoring and self-care in the digital health era. Soc Theory Health 2013; 11: 256–270. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Crawford R. Healthism and the medicalization of everyday life. Int J Health Serv 1980; 10, 365–388. https://doaj.org/article/91e7dc78db574812ab679fe568afc4ee [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Riley S, Evans A, Robson M. Postfeminism and health: critical psychology and media perspectives. 1st ed. London: Routledge; 2019: 1–200. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gill R. The affective, cultural and psychic life of postfeminism: a postfeminist sensibility 10 years on. European Journal of Cultural Studies 2017; 20: 606–626. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Riley S, Evans A, Robson M. Postfeminism and body image. 1st ed. London: Routledge; 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Evans A, Riley S. “He’s a total TubeCrush”: post-feminist sensibility as intimate publics. Feminist Media Studies 2018; 18: 996–1011. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Evans A, Riley S. Digital feeling. London: Palgrave Macmillan. Forthcoming (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 52.Riley S, Evans A. Lean light fit and tight: Fitblr blogs and the postfeminist transformation imperative. In Toffoletti K, Thorpe H, Francombe-Webb J. (eds). New sporting femininities: embodied politics in postfeminist times. 1st ed. London: Palgrave Macmillan; 2018, 207–229. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rich E. Gender, health and physical activity in the digital age: between postfeminism and pedagogical possibilities. Sport Educ Soc 2018; 23: 736–747. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rich E, Miah A. Understanding digital health as public pedagogy: a critical framework. Societies 2014; 4: 296–315. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Barad K. Meeting the universe halfway. Durham, North Carolina: Duke University Press, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lupton D. The thing-power of the human-app health assemblage: thinking with vital materialism. Social Theory and Health 2019; 17: 125–139. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Russell PL. The phenomenology of affect. Smith Coll Stud Soc Work 2006; 76: 67−70. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ash J, Simpson P. Geography and post-phenomenology. Prog Hum Geogr 2016; 40: 48–66. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ash J, Simpson P. Postphenomenology and method: styles for thinking the (non)human. GeoHumanities 2019; 5: 139–156. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sheridan J, Chamberlain K, Dupuis A. Timelining: visualising experience. Qual Res 2011; 11: 552−569. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Smith JA, Flowers P, Larkin M. Interpretative phenomenological analysis theory, method and analysis. 1st ed. London: Sage; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Willig C. Introducing qualitative research in psychology. 3rd ed. London: Sage; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Barnett P, Bagshaw P. Neoliberalism: what it is, how it affects health and what to do about it. N Z Med J 2020; 133: 76–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Macrotrends. New Zealand Immigration Statistics 1960-2022, https://www.macrotrends.net/countries/NZL/new-zealand/immigration-statistics (accessed 20 April 2022).

- 65.Murphy N. Te Awa Atua, Te Awa Tapu, Te Awa Wahine: An examination of stories, ceremonies and practices regarding menstruation in the pre-colonial Māori world. Master’s Thesis, University of Waikato, Hamilton, New Zealand, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lupton D, Michael M. Big data seductions and ambivalences. Discover Society 23. http://discoversociety. org/2015/07/30/big-data-seductions-and-ambivalences/ (2005, accessed 29 April 2022). [Google Scholar]

- 67.Boshoff P. Breaking the rules: zodwa wabantu and postfeminism in South Africa. Media and Communication 2021; 9: 52 − 61. 10.17645/mac.v9i2.3830 [DOI] [Google Scholar]