Abstract

The COVID-19 pandemic has delivered one of the worst economic shocks in modern history and the hospitality sector has been severely affected. Since small businesses from the hospitality sector are known to be relatively more susceptible to the economic complications arising from a crisis, we explore the underlying factors and management practices that influence their continuity of operations as they continue to struggle with the on-going COVID-19 crisis in Pakistan. Using a phenomenological approach, in-depth interviews were conducted to comprehend the experiences of owners-managers. The findings show that government support, cordial relationships with stakeholders, self-determination of entrepreneurs and formal planning are the most crucial factors that shaped the immediate adjustments of operational activities in response to COVID-19. These resilient practices are hygiene concerns, increased promotion through social media, innovative marketing practices (e.g., revised offerings), operational cost-cutting and employee training to comply with changing standard operating procedures from the government and industry. The practical and theoretical implications are also discussed.

Keywords: Crisis management, Resilience, Business continuity, Hospitality, Restaurants, Pakistan

1. Introduction

The global economy is experiencing severe cutbacks arising from Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) (Kuckertz et al., 2020). Worldwide, over three million people have died with COVID-19 as of December 2020 (Worldometers, 2020) and measures taken by hard-hit countries to contain the virus (e.g., lockdown and social distancing) resulted in major economic impact (GDA, 2020). According to OECD (2020), the global economy shrank somewhere from 2.4% to 2.9% and unemployment is expected to surge to levels surpassing the 2008 financial crisis.

Compared to other sectors, hospitality sector remained worst affected as global and local travel declined amid mandated lockdowns. In particular, the small to medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) were worst-hit given their size, scarce resources and limited cash flows. Sectors such as hotels and food services, retail, entertainment and manufacturing are characterized by SMEs that are susceptible to such social and economic restrictions (McKinsey and Company, 2020).

The economic impact of COVID-19 has been felt more profoundly in the developing economies. For instance, the government of Pakistan suspended most economic activities amid a strict lockdown for two months starting in the last week of March 2020. Only some businesses dealing in essential products and services like grocery retailers, online food services and pharma companies were allowed to function with stringent SOPs (Sustainable Development Policy Institute, 2020). In the capital cities of Punjab (the largest province of Pakistan), the law enforcement agencies have been enforcing SOPs related to the business continuity during lockdown while several businesses were fined or suspended for violations (The News, 2020). While these efforts were targeted at saving lives, very little regard has been given to saving livelihoods for SMEs which have been regarded as growth engine of developing countries like Pakistan (Burhan et al., 2020, Naz et al., 2016). Initial estimates suggested that in the aftermath of COVID-19 pandemic, around 1.42 million SMEs were faced with a 50% decline in revenues (Sustainable Development Policy Institute, 2020).

Amid playing a pivotal role in the economic prosperity, SMEs are usually most susceptible in times of crisis (Lu et al., 2020) because of lack of preparedness, short-term and limited cash flows, and inability to mobilize resources strategically (Runyan, 2006). The existing literature provides some explanations concerning barriers to SME development and growth, antecedents of their failures, and the impact of disasters including recovery mechanisms (Doern and Goss, 2013, Lee and Cowling, 2013). Although there is little research related to crisis management in SMEs (Doern, 2016), studies tend to focus on the recovery mechanisms following the natural disasters like floods and earthquakes (Hystad and Keller, 2006, Lu et al., 2020). The omission of contexts related to epidemics (for exceptions see Chien and Law, 2003; Tse et al., 2006) is precarious since they are relatively distinct from environmental hazards in terms of impact on business continuity. Furthermore, where environmental hazards are likely to ravage infrastructures and are usually confined to specific areas, epidemics and pandemics can have greater and enduring impacts on both population and economy (Santos et al., 2013).

Baker et al. (2020) noted that as a result of COVID-19, household spending increased sharply particularly in retail, credit card spending, and on food items. Consumers in the United States are more inclined towards preparing food at home or ordering online, consequently marginalizing spending on restaurants. Although similar research in the context of developing countries is scarce, the case appears to be very similar in Pakistan from an anecdotal point of view. Due to social distancing and partial lockdowns during COVID-19, restaurants were forced to close down for dine-in but open for takeout and home delivery. In a developing country like Pakistan with consumer base of roughly 200 million, the food industry is the second largest that also accommodates around 16% of the total employment among SMEs. Pakistan is also the eighth largest market in the world for fast-food and food-related entities (Memon, 2016). Recognizing the acute importance of restaurants and food-related outlets in Pakistan, the sector has attracted little attention regarding crisis management. Moreover, in response to the ease in lockdowns and enforcement of SOPs from the government of Pakistan, it is vital to learn and disseminate the factors and practices that are shaping business continuity in restaurants and food-related outlets amid high economic uncertainty and fears of a second wave of COVID-19.

Considering the importance of restaurants both within the SMEs as well as in the hospitality industry, this study aims to explore crisis management practices during COVID-19 pandemic in restaurants. The focus is on the developing countries, also considered as emerging economies. Pakistan, one of the largest consumer markets in terms of population, is studied as a case-in-point. The paper explores the challenges caused by COVID-19 and unravels the strategic and operational responses of restaurants and food-related outlets to the uncertain economic environment following COVID-19.

This study followed an inductive, phenomenological approach to record the descriptive accounts of owners-managers concerning their experiences and practices used in dealing with the crisis. This study in crisis management in hospitality is, to our knowledge, a rather unprecedented one as it particularly focuses on SMEs in hospitality sector and that too in often less-researched developing markets. The research was conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic. This makes it a potentially useful contribution to the literature of crisis management especially in the context of COVID-19. It can be safely assumed that given the pervasiveness of the crisis, COVID-19 will attract significant research in the coming years in hospitality industry where its impact has been felt most profoundly. In this regard, this study offers pioneering insights of practical and theoretical value.

Lastly, we aim to learn rich explanations from the owners-managers of restaurants in terms of their anticipation of the crisis, the effects on their business and responsive measures and practices that reflected resilience to the ongoing crisis. We also explore the socio-economic factors (e.g., role of government support, individual determination) that shape those measures/practices. The findings of this study offer important implications for small business owners and managers considering the growing fears of further waves of COVID-19 worldwide including Pakistan.

2. Crisis management and resilience: review and agenda

Rooted in the historical proposition of crisis (Hermann, 1963), the organization-centered definitions proposed in the contemporary work remain largely consistent (Frandsen and Johansen, 2010). A crisis refers to an unforeseen and unanticipated incident that can jeopardize the attainment of strategic goals in the context of short decision response times available to management (Hermann, 1963, Rosenthal, 2003). Similarly, Pauchant and Mitroff (1990) conceived a crisis as an unexpected disruption that can threaten the system of an organization and consequently its existence. Noticing their frequent occurrences and impact, crises are now central to the discourse of organizational studies (Orchiston et al., 2016). From the global financial crisis of 2008 to natural disasters like Hurricane Katrina in 2005, devastating floods in Pakistan in 2010, acts of vandalism such as London riots of 2011 and the ongoing conflicts in the Middle East, crises can be perplexing in nature with protracted repercussions.

Scholarly work concerning responses of organizations (including pre and post planning) to a crisis, both at the strategic and operational level, revolves around two key concepts of ‘crisis management’ and ‘resilience’ (Doern et al., 2019). Although differences have emerged in the literature on both (e.g., actors involved in the response, active, or reactive approach, focus on pre/post planning), they largely represent the same underlying philosophy of recovery management (Williams et al., 2017). At organizational level, crisis management refers to the strategic planning (including operational coordination) to prepare for, and respond to, the perils that may cause a halt or disruption of operational activities (Herbane, 2013).

The nature and extent of planning, preventive strategic measures and practices, the role of stakeholders including communities, and post-crisis organizational learning have been the foci of crisis management literature (Williams et al., 2017). A limited and context-specific but preeminent emphasis in the literature, however, is evident concerning the role of actors (individuals, organizations and communities) in downplaying the disruptions caused by a crisis (Herbane, 2013, Spillan and Hough, 2003).

Recognizing the crucial role of managers during a crisis, Pauchant and Mitroff (1990) suggested that scholarly work reflects more apparent issues of strategic planning and structural implementations but overlooks the role of beliefs, values and determination of senior managers directly exposed to the crisis. Subsequently, Pauchant and Mitroff (1992) proposed a crisis preparation framework that included five stages: (i) signal detection (anticipation), (ii) preparation (capacity building e.g., training), (iii) containment (restricting further repercussions), (iv) recovery (operational activities to regain control/alignment) and (v) learning (indicators of firm-performance during the crisis). Although different frameworks have surfaced in the last three decades manifesting the stages of crisis management, the inclusion of three phases is common, i.e., (i) pre-crisis (focusses on planning in terms of anticipation and identifying the impact of crisis), (ii) during-crisis (implementation of preventive measures), (iii) post-crisis (consolidating on the key choices for organizational learning) (see Bundy et al., 2017; Pergel and Psychogios, 2013; Hošková-Mayerová, 2016). Given that the COVID-19 pandemic was not anticipated by businesses worldwide and that they are now directly exposed to its effects, the foci of researchers is likely to be on during and post-crisis behavior (Kuckertz et al., 2020).

Likewise, critical to our comprehension of dealing with crises is the notion of ‘resilience’. The concept of resilience has emerged in different disciplines varying from social sciences to ecology. Across these disciplines, there is a somewhat similar underlying philosophy to crisis management planning and practices, whereby slight distinctions are noted with regards to its application in varying contexts (Brown et al., 2017, Folke et al., 2010, Richard Eiser et al., 2012). Hence, it is pertinent to highlight that a universal understanding of resilience is not possible since the frameworks that have appeared in literature so far are highly tailored to unique contexts (e.g. populations, level of analysis) (Brown et al., 2017, Nowell and Interdisciplinary, T.S.-D. resiliency, 2013).

Moreover, for tourism and hospitality sectors, frameworks tend to be recovery-centric for known natural short-lived disasters (Becken, 2013, Orchiston et al., 2016). Given the prolonged and complicated nature of COVID-19, limited and sectional literature concerning crisis management in small/family restaurants and characterization of small entities by a lack of formal planning (planned resilience) due to resource constraints, an improved understanding of contextual reactive approaches to crisis management (adaptive resilience) in small firms is crucial (for a detailed account on adaptive and planned resilience, see Orchiston et al., 2016).

With regard to planning, containment, and recovery, a salient shift can be observed in the literature emphasizing the capacity of firms to develop resilience in order to absorb pressures that are posed by external and internal threats (Herbane, 2013, Somers, 2009). Resilience focuses on developing processes by which the actors are able to identify, adapt and utilize resources to counter disruptions before, during, and after the crisis for reliable functioning (Williams et al., 2017). Moreover, it urges organizations and their employees to develop a rather ‘unusual’ approach to regain control swiftly (Linnenluecke, 2017, Vogus and Sutcliffe, 2012). This approach signifies the notion of ‘bricolage’ that argues for on-the-spot solutions to disruptions caused by a crisis to restore order (see Weick, 1993).

Within the realm of crisis management, the concept of Business Continuity Management (BCM) has emerged during the last two decades. BCM highlights the importance of mobilizing organizational resources by urging businesses to formalize, structure, and allocate resources in the event of a crisis such that the adversity is mitigated efficiently (Herbane, 2013). The notion is primarily based upon disaster recovery and contingency management through a ‘reactive’ strategy (Brown et al., 2017, Faisal et al., 2020). Furthermore, the focus of BCM tends to be on the individuality of a firm (a resource-based view) in terms of creating resilience by active mobilization of resources. Kato and Charoenrat (2018) suggest that BCM may significantly help to mitigate the risks in SMEs since the planning and execution of disaster recovery practices are well-thought-out and context-specific. A combined notion including both BCM and resilience is crucial to the study of crisis management in small businesses since resourcefulness has been identified as an imperative antecedent of their resilience (Dahlberg and Guay, 2015).

There is a dearth of literature concerning crisis management in small businesses since more attention has been given to larger organizations (Herbane, 2013, Doern et al., 2019). Since small firms are more vulnerable to an unanticipated crisis given their limited cash flows, unavailability of crisis management teams and a lack of formal planning (Asgary et al., 2012), the paucity of research in this area is surprising (for exceptions see Davidsson and Gordon, 2016; Doern, 2016; Galbraith and Stiles, 2006; Williams et al., 2017; Israeli and Reichel, 2003). Doern (2016) highlighted the significance of recovery management in small businesses since they play a paramount role in driving and accelerating a country’s economy after a crisis. Although a growing interest in the last decade can be seen in terms of exploring issues related to crisis management in SMEs (Doern et al., 2019, Kuckertz et al., 2020), the role and importance of innovative and iterative approaches to micro-level practices (e.g., marketing, employment) in a crisis caused by a pandemic remains untouched.

Looking at the limited literature regarding crisis management and resilience in small businesses, most studies concentrate on the pre-crisis improvement and alignment of resources to withstand in the events of a crisis (Korber and McNaughton, 2018). However, a handful have examined the responses of actors in terms of contextual alignment of resources to ensure the continuity of operations during disruptions (Doern et al., 2019). For instance, Bullough et al. (2014) explained how individuals can capitalize on their entrepreneurial intentions out of a calamity during wartime. Similarly, Martinelli et al. (2018) found that small firms with the ability to create opportunities out of the resources at hand were more resilient to the disruptions during an earthquake crisis. Ingirige et al. (2008) noted that SMEs’ individual and collective attitudes considerably influence their recovery activities. Moreover, the determination of owners-managers to survive during times of crisis reflects positively on stakeholders (including communities) that enhance a firm’s ability to absorb and mitigate pressures. A positive and informed culture that fosters clarity, fairness, inclusion and information sharing can also create resilience in small firms in the events of crisis (Weick and Sutcliffe, 2007).

Expanding further on the antecedents of crisis management and business continuity in small firms, Stecke and Kumar (2009) highlighted that a cordial relationship with trading partners in a supply chain is crucial to the success of a small firm in terms of rising above the challenges posed by a crisis. Similarly, innovative marketing practices are also critical to a firm’s success in times of crisis (Kuckertz et al., 2020). Cutting expenses by reducing the working hours of employees is also considered effective to scale-down the adversity during a natural crisis (Irvine and Anderson, 2004). Runyan's (2006) investigation of the recovery management processes in small businesses in response to Hurricane Katrina found that limited cash flows, inadequate and ineffective communications, and a lack of ability to deal with utility services shutdown were the prominent contributors to their vulnerability. However, the owners who were able to think and act innovatively soon after the crisis, experienced a consistency in sales.

Although, most of the disaster and crisis management studies have theorized engineer-oriented all-hazards theories, the hospitality sector literature concerning crisis management is predominantly guided by management-oriented perspectives (Lettieri et al., 2009). Jia et al. (2012), for instance, adopted crisis management theory to assert the importance of information and communication flow among different stakeholders. Similarly, Wang and Wu (2018) proposed a model guided by theory of planned behavior that underpins the beliefs and psychological factors of stakeholders while experiencing a crisis. Similarly, Ritchie (2008) adopted chaos theory to comprehend the challenging and complex facets of crisis management in hospitality and tourism.

The literature concerning crisis management in the hotel industry confirms an absence of contingency plans whereby the recovery/responsive practices are primarily reactive in their nature. The most common reactive resilience is shown by practices such as innovation through newer technologies for communication, strong cordial relationships with external stakeholders, enhanced marketing efforts, dedicated employee trainings and specialist hygiene protocols (Garrido-Moreno et al., 2021, Sigala, 2020). For instance, flexible and innovative practices of restaurants in Singapore in response to the SARS (Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome) epidemic helped them to resume operations promptly. These practices were largely focused on the domestic market, employee training and infrastructural changes including support from the local government (Henderson, 2007, Tse et al., 2006).

With regards to the extant crisis literature in the hospitality sector, less attention has been paid to the mid-crisis recovery stage. The prominent resilient practices discussed in this stage relate to human resources, service provision, marketing and customer relations. It is pertinent to note that the identification and role of factors that shape a unique set of resilient practices in a crisis are underexplored (Leta and Chan, 2021). For instance, an effective leadership style (internal factor) in hotels during a crisis can facilitate a fluid communication (resilient practices) among employees and customers. Similarly, the entrepreneurial orientation of the owners/managers can facilitate innovation/improvisation in the operational processes and employee relations during the times of a crisis (Hao et al., 2020b). The seminal work concerning crisis management in the hospitality sector amid COVID-19 crisis is predominantly inclined towards the hotel and tourism sectors and the empirical evidence relating to the recovery management practices within small restaurants is almost non-existent. The available literature, however, acknowledges that COVID-19 has overall affected the DNA of hospitality sector since it is not comparable to the previous short-lived events (Pillai et al., 2021, Rivera, 2020).

Since COVID-19 triggered an unprecedented chain of adversity, the economic impact has been felt across developed and developing countries. Without doubt, small businesses are likely to play a central role in the economic recovery of every affected country. Therefore, pressing and progressive research concerning crisis management practices in firms associated with the hospitality sector is crucial for the industry revival.

3. Methodology

3.1. Research design

Considering the scope of research problem at hand, the focus was to unravel the multidimensional experiences of hospitality entrepreneurs during the COVID-19 crisis. The investigation was thus designed as an exploratory study using qualitative research that would enable seeing the experience through the subjects’ eyes (Bryman, 2012). The multidimensional experiences that were explored covered the anticipation of the crisis, the actions taken, and apprehensions of the future outlook for the business environment.

Among different qualitative research techniques available for exploring these experiences, a phenomenological approach is best suited as it explicates the lived experiences of a certain phenomenon (Laverty, 2008, Starks and Trinidad, 2007). This is established in comparative reviews of qualitative approaches where a phenomenological approach is deemed suitable for understanding the lived experiences more than influence of social processes (Goulding, 2005, Starks and Trinidad, 2007).

In qualitative research across disciplines like hospitality and marketing, studies employing phenomenological interviews have increased steadily over the years (Goulding, 2005, Kirillova, 2018, Robinson et al., 2014). Likewise, the phenomenological approaches are commonly employed in entrepreneurial studies where unraveling and comprehending the experiences of entrepreneurs are important (Doern, 2016). An interesting case-in-point for using phenomenological methods is in scenarios where the crisis gets unfolded like a ‘natural experiment’ (see Martinelli et al., 2018). In the case of the crisis studied in this paper, the pandemic and mandatory lockdown unfolded for hospitality entrepreneurs similar to a ‘natural experiment’ that can be explored as a lived experience. The sudden and unexpected shock of a pandemic was unprecedented at least in the last several decades. Businesses closing, one way or the other, and uncertainty looming over economic prospects aggravated the ‘experiential’ part of pandemic as a phenomenon (Eggers, 2020).

3.2. Sample

Participants in the study were SME business owners or managers in the Pakistani hospitality and non-probability sampling was used such that participants were included to match the research objectives (Bryman, 2012). Participants were based in Lahore, Pakistan’s second largest city, which is a hub for the hospitality sector. Since lockdown was enforced throughout the city, like the rest of the country, it was safe to presume that all respondents had experienced the crisis in one way or another. Restaurants were only invited to participate if they offered at least two out of the three typical modes of dine-in, takeaway, and home delivery. This was to learn any differences that might have been experienced in operations or services from a managerial standpoint.

The participants who were interviewed were either the owners or managers of restaurants. In either case, the interviewee would be equivalent of either a Chief Executive Officer or Chief Operating Officer of a large-sized business who was responsible for the business operations and planning. The term “owner-manager” thus reflects all the interviewed participants. Of the 16 owners-mangers that took part in the study, all were male and most were aged 40 and under. Four businesses had fewer than 10 employees and seven had 10–19 employees. Table 1 presents the profile demographics of participants.

Table 1.

Demographics of respondents.

| ID Code | Restaurant profile (Food type / Age) | No. of employees | Operations during lockdown | Owner-manager profile (Status/Gender/Age) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OM-1 | Sandwiches & Desserts / 5 Years | < 10 | Delivery & Takeaway | Co-Owner / Male / 31–40 |

| OM-2 | Pizzas / 5 Years | < 10 | Delivery & Takeaway | Owner / Male / 31–40 |

| OM-3 | Arabian food / 15 Years | 15 | Delivery & Takeaway | Owner / Male / 31–40 |

| OM-4 | Local cuisines / 25 Years | 20 | Selected customers only | Manager / Male / 21–30 |

| OM-5 | Burgers & Pizzas / 10 Years | 16 | Delivery & Takeaway | Co-Owner / Male / 21–30 |

| OM-6 | Chinese food / 27 Years | 20 | Very limited | Owner / Male / 31–40 |

| OM-7 | Deli / 2 Years | 12 | Delivery & Takeaway | Co-owner / Male / 21–30 |

| OM-8 | Local cuisines / 22 Years | 30 | Delivery | Manager / Male / 51–60 |

| OM-9 | Chinese food/30 Years | 16 | Delivery & Takeaway | Owner / Male / 51–60 |

| OM-10 | Local cuisines / 10 Years | 25 | Delivery & Takeaway | Owner / Male / 31–40 |

| OM-11 | Local cuisines / 12 Years | 20 | Delivery & Takeaway | Co-Owner / Male / 41–50 |

| OM-12 | Arabian food / 6 Years | < 10 | Delivery & Takeaway | Owner / Male / 31–40 |

| OM-13 | Local cuisines / < 1 Year | 15 | Delivery | Owner / Male / 21–30 |

| OM-14 | Chinese food / 5 Years | 12 | Very limited | Manager / Male / 21–30 |

| OM-15 | Arabian food / < 1 Year | < 10 | Delivery & Takeaway | Manager / Male / 31–40 |

| OM-16 | Burgers & Pizzas / < 1 Year | 12 | Delivery & Takeaway | Owner / Male / 21–30 |

Notes:

- Responses of OM-1, OM-4, OM-7, OM-8, OM-13, and OM-16 are selected and presented in Appendix 1.

- All restaurants had dine-in facility that was discontinued during the mandatory lockdown (mid-March to early-June 2020).

3.3. Data collection

The semi-structured interview questions for data collection focused on different aspects of the crisis. They were developed in a way that allowed participants to share their experience in their own business setting. The questions were reviewed by a colleague outside the research team to help ensure that local context and the communication style of local business community were reflected in the interview protocol.

As part of the engagement strategy, the interviews were conducted during June 2020 when the effect of COVID-19 crisis and lockdown were clearly being felt. Conducting interviews during the event meant that the experiences could be shared more profoundly. The approach used is similar to phenomenological studies on crises (e.g. Doern, 2016; Runyan, 2006). In particular, the restaurants had gone through both the unprecedented stringent lockdown as well as Ramadan (Muslim month of fasting). In the latter, restaurant activities are generally different due to the religious ritual of fasting during the day. Despite businesses experiencing cyclical easing and enforcement of lockdown, overall business activity was limited across the country and restaurants were no exception.

Interviews were conducted after reviewing the profile of restaurant in terms of its offering and the specific nature of business. The context of study was explained to the participant owners-managers at the onset emphasizing that discussion would focus on the COVID-19 crisis. They were asked to freely share their experience of the crisis and how it had affected their business especially since the mandatory lockdown was enforced in March 2020. All the owners-managers invited to participant consented to the interview with the understanding of anonymity of their business’ names and having the interview being transcribed by the interviewee. Each interview took about 15–25 min. Interviewees shared details rather candidly about their experiences. Appropriate safety measures were employed during the face-to-face interviews.

3.4. Analysis

From the different options available for analysis in phenomenological studies, this study followed Interpretive Phenomenological Analysis or IPA (Kirillova, 2018). The analysis involved reviewing the transcribed notes and developing superordinate themes that were aggregated to find commonalities across different respondents. The analysis helped recreate the experiences and more importantly aggregated the interpretations from different participants into themes that seemed pertinent to the COVID-19 crisis in particular and may be generalized to any other crisis.

During the interviews, it was noted that after about ten interviews, the responses were largely similar. Observing the repetition, it was deemed appropriate to conclude after completing 16 interviews (Creswell, 2014, Francis et al., 2009). Different questions in the semi-structured interviews related to three themes that can be considered as superordinate themes in the process of IPA. The key findings categorized in these three superordinate themes are discussed in the next section and an overview of the discussions is presented in Appendix 1.

4. Findings

The first of three superordinate themes was anticipation and preparation of the crisis. The second main theme was about the effects on the business whereas the third theme related to managing the operations in view of future options. These three themes comprehensively covered firm responses to the crisis and captured the responses of owners-managers without exception. Within each theme, a number of key findings were made using thematic analysis whereby statements from different interviewees were classified in different sets.

4.1. Anticipation of the crisis

An overall lack of anticipation of the crisis by the restaurant owners-managers was observed. It was only until the government enforced a mandatory lockdown in mid-March 2020 that the crisis was taken seriously albeit still in varying degrees. News and updates on the crisis in the mainstream as well as social media had been increasing consistently. A precedent for mandatory lockdown in Hubei province (China), the epicenter of COVID-19, was already there (Reuters, 2020). Yet there was a glaring lack of anticipation among the restaurant owner-managers for a lockdown that could be severely detrimental for the hospitality sector. Almost all owner-managers expressed no anticipation of the event. A minor exception is associated with the owner of restaurant OM-14 who mentioned:

“Initially our main concern was that since there are hygiene-related concerns in this crisis, customers might hesitate in eating out. I could see that in the media reporting restaurants being affected in the developed countries. I feared the same could happen to us here as well”

Another restaurant owner (OM-1) mentioned that he got clues from the international brands that his restaurant worked with. Managers of these brands expressed some concerns about the possibility of COVID-19 turning into a large-scale event that could escape China to reach Pakistan and disrupt everyday life.

Two key aspects emerge concerning the anticipation of the crisis. First, the owner-managers generally did not feel compelled by the ubiquity of the crisis that was brewing in neighboring China. Like many other countries, Pakistan has strong relations with China in terms of trade, tourism, and student exchange. Still, the fear of COVID-19 spilling into Pakistan was deemed to be small, if not completely absent, among the restaurant owners-managers. Second, owner-managers varied in terms of their exposure to the environment. Some of them showed a knack for observing the environment carefully and exploring the possible effects of different events. Others would keep the news and information from the external environment away from their business operations. Such disregard for events in the external environment is somewhat typical of the prevailing culture in South Asian societies. A general disengagement with the external environment especially the international arena is presumably because of preoccupation with local affairs. Such societal traits manifested into the restaurant owners-managers as well.

4.2. Effects on the business

Before the pandemic, almost half of the owners-managers had plans to expand their businesses in terms of opening new branches and expanding the scope of services. When the lockdown was enforced, an almost instant reaction was to scale back the expansion and conserve cash to ensure continuity of the business. As expressed by a Chinese restaurant owner (OM-9):

“Our business was doing well and we had plans finalized to open up a new branch in DHA [an upscale locality in Lahore]. However, when we were forced into a mandatory lockdown, we thought that this can be problematic and we need to conserve resources to continue paying salaries to our staff. Expansion can wait till it is over”

This ‘knee-jerk’ reaction is seemingly contrary to the lack of anticipation arising from not considering the possibility of a crisis affecting own business. On one hand, almost all hospitality SMEs seemed to care little about the crisis but on the other hand, they almost instantly rolled back their expansion plans.

Caught rather unaware by a mandatory lockdown, almost all participants made demanding efforts to conserve resources to ensure continuity of their business. A major driver of this panicked scrambling was the uncertainty surrounding the lockdown duration. The last time such an action was taken was in 2011 when in a few major cities of Pakistan, local authorities restricted some commercial and public activity as a safeguard against the dengue outbreak (Ahsan, 2019). Most of the owner-managers had little memory of the 2011 lockdown that was lifted after ten days or so and was much relaxed in terms of enforcement. In comparison, the COVID-19 lockdown was much more prolonged and pronounced. Organizational reminiscence of a crisis as a way of helping to anticipate or plan for a foreseeable crisis has been observed in large, more formalized organizations (Hätty and Hollmeier, 2003) but less often in SMEs and hospitality.

Remembering the 2011 event, owner-managers anticipated that the lockdown would be lifted in two or three weeks since authorities were enforcing the lockdown in two or three week periods and extending it as time went by. This is expressed by one restaurant owner (OM-3):

“Few years ago, when dengue outbreak was there [in 2011], it was lifted only after ten days. Everyone feared that it will continue for months but it ended in a matter of days. People were thinking the same this time but it proved to be very different.”

The uncertainty in severity and longevity of lockdown generally resulted in taking short-run measures and ignoring the long-term possibilities. However, over a period of three months, the owners-managers realized the severity of the situation and began thinking of longer planning horizons. Such a reactionary approach to an uncertain problem might be deemed natural but is also due to a lack of planning capacity on part of SME owners-managers. At the same time, their approach is consistent with findings from macroeconomic crisis that entrepreneurs remain persistent and adaptive (Davidsson and Gordon, 2016).

4.3. Managing operations and business activities

The response from restaurant owner-managers during the COVID-19 crisis mainly emerged in the aftermath of a government-initiated mandatory lockdown in mid-March 2020. The multifaceted response as described by all participants was multifaceted spanning all the key business functions. The respondents were asked particularly about the changes in the operations, Human Resource strategy and promotional strategy of their businesses. Each respondent showed varying ways to deal with these aspects with a common underlying theme of being focused on the continuity of the business. One owner (OM-13) expressed his worries that spanned across all functions:

“We [restaurant] are all about experiencing food rather than just eating or consuming it. I’d say for us its 60% experience and 40% about food. How can I deliver ‘experience’ or offer it as a takeaway? So we have decided to wait it [lockdown] out. We don’t want to compromise on the experience, so we have kind of halted the operations and this has affected all functions.”

It is pertinent to note that the responses observed in this process are similar in character to the coded behaviors and strategies of organizations growing amid hard economic times (Eggers and Kraus, 2011). These responses quintessentially cover all the operational aspects of a [restaurant] business.

4.3.1. Supply chain

The supply chain was managed almost without problems by all owners-managers. This streamlined handling of the supply chain was possible largely because each owner-manager had a deep relationship with their vendors. These relationships transcended formal business-to-business relationships to create more personal ties that had friendly undertones. Owners-managers would understand the challenges their vendors were facing and in turn, the vendors understood the limitations of their customers.

In addition to a cordial understanding of their vendors, the owner-managers were concerned about ensuring the availability of quality ingredients as well as hygienic practices adopted by their vendors. For example, OM-4 and OM-10 emphasized their actions on scrutinizing their vendors as vigilantly as possible. One restaurant owner (OM-11) particularly emphasized the quality of ingredients and ensured that he had vendors lined-up in case if any of the trusted vendors were not able to provide ingredients on time:

“For us, ingredients like meat are crucial. We cannot compromise on its quality even if we have shifted to home deliveries and takeaways. We are now actively looking for alternative suppliers in case if our existing vendors fail to supply amid transportation issues”

Continuation of the supply chain was particularly deemed important in wake of restaurants scrambling for alternative means of business like home delivery and takeaways.

4.3.2. Human Resources (HR)

Owner-managers were concerned about retaining employees amid all the financial hardships and two principal reasons emerged for retention of employees. First, there was an underlying sense of empathy among the owners-managers for their workers who were vulnerable to redundancy. Second, the restaurant owners-managers explained to the staff that they will all work together through these testing times and that resulted in high morale in the business. A somewhat unique aspect concerning restaurants and hospitality sector businesses in retaining their employees was that the inescapable need for skilled staff who would be required on opening the business after shutdown has ended. This approach contrasted to the rather generic approach of balancing the skilled and young employees (Eggers and Kraus, 2011).

It is pertinent to observe that both reasons for not laying-off employees had a deeper association with another underlying consideration of the crisis being short-lived. For instance, two owner-managers (OM-2 and OM-16) stated that they were concerned about the safety of their employees in this episode and ensured that they were adequately briefed about personal hygiene, wearing masks and social distancing. This was to ensure that no employee would face the adverse consequences of contracting the disease and further compromise business operations.

One important aspect that was shared by all the owner-managers was that they observed that junior staff had a general disregard for safety guidelines. Serving staff, helpers, and even chefs would, at times, not take SOPs seriously at work. The frustration was expressed by a restaurant manager (OM-15):

“At times it is disappointing that our lower staff don’t take mandatory SOPs like wearing a mask seriously. We are considering imposing a fine on violation it but it will also hurt morale of the staff. But the problem remains that in our society, the low-income working class is taking neither the crisis nor the SOPs seriously”

In this regard, owners-managers initiated a comprehensive training activity within their own context to bring awareness about the SOPs related to hygiene. Most of these SOPs were communicated widely by government authorities and the World Health Organization (WHO). Using different content and training activities, the protocols on social distancing, handwashing, and wearing masks were communicated to staff. One owner-manager (OM-16) mentioned:

“We realized that our staff is at the heart of our compliance with government SOPs. We have trained them extensively and now are investing in creating video content for their proper training”

They had to be monitored for complying with the SOPs to avoid adverse consequences (penalties) from local authorities.

4.3.3. Marketing and promotion

In promoting the business, owner-managers resorted to alternative means of communicating with customers. Some resorted to using digital technologies like social media marketing, SMS advertising and email marketing to promote their businesses (for example, OM-1, OM-4, and OM-14 focused particularly on moving towards digital activities). Furthermore, almost all owners-managers were exploring interactive options to get their message across as expressed by a pizza restaurant (OM-2):

“Mandatory lockdown has forced us to look for creative options of developing interactive content like short videos and using social media to make it viral. It is a bit challenging but inevitable.”

Almost all restaurants were without a proper database of customers. The only exception having a database relied heavily on it to engage customers almost effortlessly. In contrast to others, this restaurant was able to effectively communicate delivery options to customers, hygiene measures as well as promotional activities to its loyal customer base.

An important aspect of promoting the products and services was to effectively communicate to customers that the restaurant was following all government-mandated SOPs. All owners-managers realized the continuity of their business relied on customers who would be confident of hygienic practices in preparing and serving foods. For some owner-managers, taking care of these SOPs was the cornerstone of their marketing and promotional activities amid the COVID-19 crisis. A stronger emphasis on observing hygienic practices in a developing country has its roots presumably in relatively less regard for hygienic practices in society. This implied that the businesses had to exercise extra caution in both implementing SOPs (as discussed earlier) and communicating the same to bolster customer confidence.

5. Discussion and conclusions

Hospitality SMEs in Pakistan have experienced the COVID-19 crisis in ways that explicate their outlook toward business, management style, and society in general. The findings from the interviews were discussed in terms of anticipation of the crisis, its effects on individual businesses and their responses in terms of managing the operations and business activities. In line with a phenomenological approach, the key phenomena that emerge as findings from this study are summarized in Table 2. These phenomena are then translated into a framework explaining the relationship between underlying constructs (Creswell, 2014).

Table 2.

Observed phenomena and relationships between different factors.

|

Observed phenomenon |

Exemplar statement |

Explanation |

|---|---|---|

| Factors shaping the response to the crisis [Input] | ||

|

|

Owner-managers showed seriously limited anticipation of the crisis and its potential effects on business. |

| Even when the crisis started affecting their businesses directly by mandated lockdown, owner-managers remained largely uncertain about its long-run effects. | ||

|

|

Almost derived from the Shakespearean undertone of ‘this too, shall pass’, owner-managers expressed a determination to continue their business. They showed determination albeit of varying intensity to manage resources in ways that they would manage the business. Using cash savings and resources allocated for expansion to manage fixed costs were commonly observed steps. |

|

|

Limited anticipation of crisis and a relatively casual disposition is also a manifestation of informal planning and an overall constricted planning horizon among hospitality SMEs. |

| Their approach seemed more of managing business on a short-run basis especially during crisis rather than planning in a long-run. | ||

|

|

For both employees as well as vendors, the restaurant owner-managers showed an emphatic attitude that transcended dealings from a business perspective |

|

|

Owner-managers faced the conundrum of not being able to offer ‘experience’ and either had to wait (do nothing) or let go of the experience element |

|

|

Amid the crisis, owner-managers did not seem to receive much support from the government. More interestingly, they did not anticipate such support either. |

| Actions to manage the crisis (responsive measures) [Output] | ||

|

|

Owners-managers scrambled to explore new possibilities of dealing with the crisis by focusing more (or even entirely) on home delivery and takeaways. |

|

|

A number of steps were taken to reduce fixed costs and overheads |

|

|

There is an ostensible difference between the owner-managers and staff on hygiene-related measures. Owner-managers enforced the measures as a means of gaining customer confidence that the business and its products are safe for consumption. |

|

|

In wake of the crisis, owner-managers ensured that business continuity is ensured in terms of staff availability. Since the crisis affected almost all businesses, management and staff had a consensual arrangement of reduced salary instead of layoffs. |

|

|

Special price and volume discounts were offered by almost all restaurants to attract customers. |

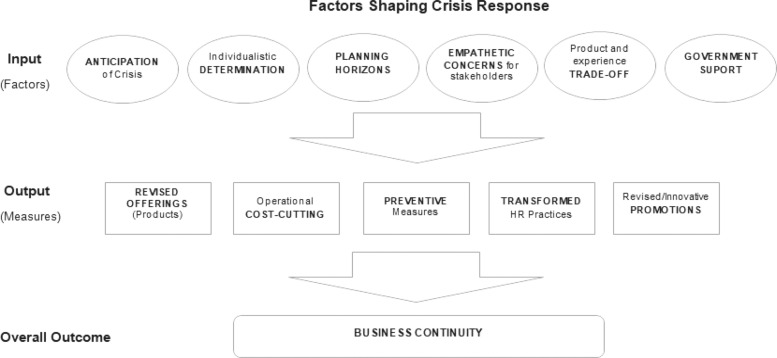

The observed phenomena summarized in Table 2 can be also expressed as inter-related constructs. In doing so, the identified factors are dubbed as input and output factors. The input factors represent those elements that create a certain perception of the crisis and personal traits of owners-managers that would impact their particular actions in response to the crisis. The output factors represent those elements that are part of the crisis management strategy of a business. As illustrated in the framework shown in Fig. 1, responsive measures/practices in the aftermath of the crisis (like COVID-19) are expressed in terms of transformed business operations such as promotional activities, HR strategy and hygienic measures. Different variables in this generic framework are thought to take different values in diverse cultures as they did in the Pakistani cultural context.

Fig. 1.

Framework for Crisis Management in hospitality SMEs.

The proposed framework for crisis management in small businesses from the hospitality sector suggests influential antecedents that shape the immediate responsive operational measures from owners-managers in response to the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic. Government support has been highlighted as an influential factor that shapes decision making regarding operational responses. The need to comply with changing SOPs from the government calls for regular employee training. Moreover, some owners thought that insufficient tax relief and subsidies in the form of relaxation of utility bills were not enough to ensure business continuity, forcing them to invest through their savings or borrowings. These results are in line with earlier studies that argue for the paramount role of governments in supporting small businesses through crises (Henderson, 2007, Tse et al., 2006). Similarly, increased cooperation and humanistic concerns for stakeholders are also found to be crucial in devising appropriate responsive measures. Owner-managers were able to treat internal and external stakeholders as one unit for the greater good of the continuity of business and to avoid redundancies. Weick and Sutcliffe (2007) also noted that positive attitudes of owners toward stakeholders foster clarity, fairness, inclusion and information sharing that creates resilience in small firms during a crisis.

A lack of planning to mitigate a crisis situation was evident in respondents since small businesses tend to focus relatively more on short term goals. This influences the nature of immediate responses because small businesses are known for their flexibility regarding the adoption of short-lived or contingency practices (Martinelli et al., 2018). Similarly, owners-managers were reluctant to adapt to the new situations during the early days of lockdown since they anticipated these disruptions as short-lived. It was after the first two weeks into the lockdown when contingency planning was brought in. This lack of anticipation resulted in poor or late responsive measures (Doern et al., 2016) for some. Lastly, Pauchant and Mitroff (1990) view the positive attitudes and determination of the entrepreneur as the most critical antecedent of resilience during a crisis. Most of the owners-managers were positive about bouncing back that reflected well in their resilient practices.

As a result of these influential factors, the proposed framework suggests the output in the form of resilient practices (based on the notions of ‘reactive strategy’ and ‘bricolage’) that ensures business continuity (Linnenluecke, 2017, Vogus and Sutcliffe, 2012). Firstly, the revised offerings were crucial to a sustainable business during the COVID-19 crisis. Some restaurants suspended their dining-in services and focused on home delivery while others (mostly theme-based restaurants) chose to suspend activities all together and focused on planning related to resuming services after the lockdown (Doern, 2016, Ergun et al., 2010). Second, the preventive measures in the form of upholding the SOPs related to hygiene in the kitchen and during delivery were crucial for business survival. Restaurants with an increased focus on such preventive measures were able to win the confidence of customers and avoid penalization from local authorities (Henderson, 2007). Third, the effective management of people also played a vital role in securing continuity of business. The positive attitude of owners-managers toward their employees established a mutual understanding of increased cooperation to navigate through these testing times. Most of the owners were rather reluctant to let go of their employees considering that it is difficult to recruit trustworthy and hardworking people. Few owner-managers reported a lack of interest in employees to comply with SOPs but others were able to enforce through interventions. Similarly, regular employee trainings played a crucial role in ensuring compliance with SOPs for most owners-managers (Ingirige et al., 2008, Tse et al., 2006). Fourth, Kuckertz et al. (2020) highlight the importance of innovating marketing strategies during crises. A majority of restaurants extensively used social media to regularly communicate their promotions and offers to the customers. A few experienced highly favorable outcomes by sharing videos with their customers that reflected compliance with SOPs by their kitchen staff. Delivery drivers were also shown to be wearing protective gear while frequently sanitizing their hands. This was particularly appreciated by their customers and proved to be a crucial confidence-building strategy. Lastly and most importantly, a majority of the restaurant owners immediately returned to operational cost cutting strategies. The most common were daily inventory on key items only and reduced usage of energy.

It is argued that small businesses are more susceptible to the economic complications arising from a crisis (Lu et al., 2020) and there is a paucity of empirical research with regards to crisis management in small firms (Doern et al., 2019, Herbane, 2013). This empirical study contributes to the literature in three unique ways. First, this study qualifies as the first investigative research (to the best of our knowledge) that adds value to the discourse of crisis management in hospitality sector SMEs by exploring the direct experiences of owners-managers in response to the COVID-19 crisis in terms of learning about their anticipation of the crisis, the impact on their businesses and their operational responses. Second, acknowledging the economic value of the hospitality sector to both developing and developed economies (Memon, 2016), this study presents first-hand insights into the crisis management practices of small businesses in a highly context specific setting, Pakistan. The proposed framework (Fig. 1) highlights the influence of pre-eminent factors on the continuity of restaurants in Pakistan and the responsive operational activities that drew a line in terms of making them either resilient or vulnerable to the crisis. Lastly, our study explores crisis management practices and their antecedents in small firms beyond a static focus in literature on barriers to business development and failure and the nature and impact of natural short-lived disasters (e.g. Cardon et al., 2011; Doern and Goss, 2013; Lee et al., 2015).

Practically, the findings of this study have several implications. For instance, government input in terms of clarity and relaxation on dining-in within restaurants is much needed. Moreover, considering the limited finances available to small businesses, a fair and transparent financial relief package from the government of Pakistan is likely to play a key role in ensuring the survival and continuity of these small restaurants. Similarly, SME owner-managers in the hospitality and other related sectors should strive for increased cooperation and communication with their stakeholders (most importantly suppliers and customers). This has emerged as a crucial factor for ensuring business continuity that fosters a cooperative and empathetic culture in which the stakeholders work as a unit in times of a prolonged crisis. Also, the literature concedes a lack of formal planning in small firms. Considering the prolonged nature of the COVID-19 pandemic and looming fears of second and third waves in many countries, owner-managers should consider the importance of basic formal planning and try to incorporate measures relevant to their exclusive context.

In terms of responsive measures, owner-managers of small restaurants can leverage and promote their conformance to hygienic practices as a way of securing the trust of both customers and the government. Moreover, exclusive discounts on home delivery and excessive communication through social media are likely to bolster sales. Lastly, regular employee training in line with the changing SOPs from the government of Pakistan is essential. These shall focus on standard preventive measures including epidemic communication guidelines and infection control at workplace through befitting hygiene techniques. For example, mandatory temperature checks of employees (at regular intervals) and customers should be carried out including record keeping of their contact details.

It is pertinent to note that as a result of certain progressive measures from the government of Pakistan (e.g., revised SOPs regarding dine-in operations and regular safety inspections from the Punjab Food Authority (PFA)), the dine-in restaurants are now opening back with full operations resumed. Under the new SOPs, customers will have to wear a mask during in-door dining whereas physical greetings are strictly prohibited. Also, alternative chair seating is made compulsory for dine-in customers. In follow-up discussions with some of the respondents (owners), two months into the initial data collection, promising signs of revival were sensed that reflects some optimism for the restaurants in Pakistan during these challenging times.

Regarding the limitations of this study, the sample may not be representative of small restaurants from remote and semi-urban areas. Moreover, our focus is more inclined toward the factors that have shaped the immediate operational adjustments of restaurants (signifying the notion of ‘bricolage’). A holistic perspective concerning mobilization of other internal resources along with engagement with other stakeholders (such as the community) was not investigated given the limited but a focused scope of this study. However, exploring such interventions is open to further research.

Appendix 1.

See Appendix Table A1, Table A2, Table A3.

Table A1.

Selected responses on anticipation and preparedness for COVID-19 and other crisis.

| ID Code | When COVID-19 seemed to be a threat to your business | Level of preparedness for COVID-19? | Level of preparedness for other crises (e.g. natural hazards)? | Explanation of the level of preparedness |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OM-1 | Around the mandatory lockdown; took it more seriously during Ramadan | Not prepared | Generally not prepared | Rely on cash savings as the only form of preparation for any kind of crisis |

| OM-4 | Slightly before the lockdown due to reduced sales | Not prepared | Generally prepared for hazards and crisis | Follow professional health and safety procedures |

| Not initially prepared for COVID-19 although prepared for other crisis | ||||

| OM-7 | Around the mandatory lockdown | Not prepared | Generally prepared for hazards and crisis | Mainly because of own experience of a branch fire a few years ago; secured business by means of insurance after the fire incident |

| OM-8 | Slightly before the lockdown due to reduced sales | Not prepared | Generally prepared for hazards and crisis | Specially prepared for seasonal outbreaks (like dengue) |

| OM-13 | Slightly before the lockdown | Not prepared | Generally prepared for hazards and crisis | Our line of business is more of a luxury than a necessity and any crisis affects us severely. This prompts us to be more cautious. |

| OM-16 | Only after the lockdown was strictly enforced | Not prepared | Generally prepared for hazards and crisis | Take necessary safeguards against fires and natural hazards |

Table A2.

Selected responses on the effects of crisis (COVID-19) on business amid the lockdown.

| ID Code | Initial perceptions of the effect of the lockdown and COVID-19 | Threat perception of COVID-19 crisis in the long run after experiencing the lockdown |

|---|---|---|

| OM-1 | We took it less seriously, especially in the first few weeks even though the brands working with us expressed caution throughout | With the ease of lockdown, things started getting back to normal but it doesn’t seem certain amid possible re-enacting of lockdown |

| OM-4 | When lockdown started, we were mainly concerned with paying the costs, especially the fixed costs, amid big drops in sales. For us, continuity was possible only due to cash reserves. | Even with the lockdown, we are exercising great caution and equipping ourselves to safeguard against this disease. We want to remain cautious until a sustainable solution to the disease (like a vaccine) is found. |

| OM-7 | Soon after the lockdown, we were forced to roll back our expansion plans like opening a new branch in an upscale locality. Such effects were profound and made us think that it might be a long-term threat. | Although things have eased up but we are being cautious and now planning from week to week basis only and feel a great deal of uncertainty. |

| OM-8 | It was a first-time experience that such lockdown was being enforced. So we didn’t think of it as a long-term thing. We continued to move from one extension [in lockdown] to another every two to three weeks | Apart from COVID-19 being a personal hazard as well, we feel that the dine-in and catering business took a strong blow. Although takeaway and home delivery fared well, they cannot compensate for the adverse effects on the other two business segments i.e. dine-in and catering |

| OM-13 | Particularly for a developing market like Pakistan, we anticipated this to be a long-term thing because of our economic situation. | Honestly speaking, we don’t see the lockdown to be easing up. It is a crisis that very much seems as there to stay |

| OM-16 | At the start of the crisis, it was a bit hard to believe, but as time passed, the effects became more pronounced and we realized the seriousness | Due to people working from home who would order food via delivery service, we sales going up a bit and this, more than the lifting of the lockdown, made things easier for us. |

Table A3.

Selected responses on responsive measures to manage COVID-19 crisis amid the lockdown.

| ID Code | Steps taken to manage the OPERATIONS during COVID-19 to ensure continuity of business |

Steps taken to PROMOTE during COVID-19 to ensure continuity of business |

Government support | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Operations | Supply chain | HR | Promotion | Managing sales | Making business accessible to customers | Communicate hygienic measures to customers | ||

| OM-1 | Rolled back on all expansion activities | We generally don’t keep large stock – reduced it further to mitigate against uncertainties | Owners also took cuts in personal remuneration and tapped into savings to conserve cash to ensure payroll continuity because of caring for employees and in anticipation of restarting the business | To promote business, we relied heavily on deals and discounts |

Sales were hard to maintain With all measures taken, we could only reach a quarter of our normal sales |

Going digital to ensure customers can be engaged more effectively | Very difficult to ensure all measures, as diligently as advertised. Mainly because employees don’t comply. First, had to keep a strong vigil on employees; secondly tried to reassure customers that we are complying | No support although claims were there |

| We considered that events (like small parties and birthdays) would still be held within families so we offered deals themed around such to engage customers effectively | ||||||||

| OM-4 | Our operations altered during this period and we focused a lot on social distancing, wearing masks, and hand sanitization | We observed and evaluated our vendors in terms of being compliant with SOPs. We continued working only with those who were following them | For our HR, we created awareness against being careless in this situation Some compromises were made in terms of HR in terms of working hours to reduce the payroll – went for reduced hours and compensation in lieu of complete layoff |

We have an already established digital presence and some corporate customers. Still, we had to go for price discounts | Price discounts were the go-to-strategy to keep sales on track | Same as previous | In our digital communication on different platforms, we tried to be reassuring of the measures taken | No support as such for the hospitality sector was there |

| OM-7 | Our core focus was on ensuring the quality of ingredients so we focused greatly on our vendors in the supply chain. We looked for alternatives to ensure continuity of business | Supply chain was at the heart of our business continuity | We retained all employees and asked them to take paid leaves and go to their hometowns. It became a challenge in restarting the business as transportation back to the city was a bit of a challenge |

We believed that satisfying customers with hygienic measures were our biggest concern. We were cautious on that front but became more careful with that. | While we went for delivery mode, it couldn’t be relied on completely – consequently, sales went down significantly | We have been trying to develop takeaway and delivery operations as much as possible | Required strong compliance with rules of wearing masks and kept a strong check like CCTV monitoring in work areas as mystery visits Compliance by employees is the center of our communication to customers in these times |

Didn’t get much support but didn’t need much. Only support was localized support in electricity bill |

| OM-8 | Moved from one lockdown extension to extension in anticipation of being allowed to open up. Ended up waiting for more than two months straight |

Well, this didn't prove to be a bigger challenge since vendors were also affected and they were also prepared for it. Orders are significantly reduced across the supply chain, so it was less of an issue. |

We ensured that we don’t do any layoffs | Changed business model to takeaway/delivery Focused on communicating compliance with hygiene standards |

Value-based benefits like quality delivery | Creating awareness among regular customers using our database | This was the mainstay of our "promotional" activity so we paid a lot of attention to it | Low-income staff got support from the government As a business, we had some support in subsidy on utility bills and exemption on sales tax |

| OM-13 | We were based on experience so we couldn't do much and closed operations | Not applicable – business remain closed because we didn’t opt for delivery or takeaway | We waited but had to let go most of them Only essential staff is there with 50% pay to restart |

Not applicable | Not applicable | Doesn't apply because our work was experience-based and with lockdown we cannot operate even on delivery | N/A - the dine-in (main activity) had to shutdown | No support - in fact, it was kind of adverse as the government’s lack of clear policy hampered our planning scenarios severely |

| OM-16 | We focused on cost-cutting by closing down unnecessary areas | We have long-term relations with vendors We focused on their hygienic practices |

Took care of their health Reduced headcount Wearing mask/gloves/wash hands is very strictly enforced |

Shifted focus to online/digital OOH gave discounts and deals (complimentary) free sanitizers |

Shifted to delivery and takeaways | Delivery takeaways getting good orders so we are accessible |

We are making awareness videos for awareness about hygienic and SOPs | No support We didn't anticipate or expect from the govt. |

References

- Ahsan, A., 2019. Dengue and how it was controlled in 2011. Dly. Times.

- Asgary A., Anjum M.I., Azimi N. Disaster recovery and business continuity after the 2010 flood in Pakistan: case of small businesses. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2012;2:46–56. doi: 10.1016/j.ijdrr.2012.08.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Baker, S.R., Bloom, N., Davis, S.J., Terry, S.J., 2020. COVID-Induced Economic Uncertainty. NBER Work. Pap.

- Becken S. Developing a framework for assessing resilience of tourism sub-systems to climatic factors. Ann. Tour. Res. 2013;43:506–528. doi: 10.1016/j.annals.2013.06.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brown N.A., Rovins J.E., Feldmann-Jensen S., Orchiston C., Johnston D. Exploring disaster resilience within the hotel sector: a systematic review of literature. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2017;22:362–370. doi: 10.1016/j.ijdrr.2017.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryman A. Social Research Methods. 4th ed. Oxford University Press; 2012. https://doi.org/0199588058. [Google Scholar]

- Bullough A., Renko M., Myatt T. Danger zone entrepreneurs: the importance of resilience and self-efficacy for entrepreneurial intentions. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2014;38:473–499. doi: 10.1111/etap.12006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bundy J., Pfarrer M.D., Short C.E., Coombs W.T. Crises and crisis management: integration, interpretation, and research development. J. Manag. 2017;43:1661–1692. doi: 10.1177/0149206316680030. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Burhan, M., Swailes, S., Hameed, Z., Ali, I., 2020, 42, 1513–1529. HRM formality differences in Pakistani SMEs: a three-sector comparative study. ER ahead-of-p. https://doi.org/10.1108/ER-11–2019-0440.

- Cardon M.S., Stevens C.E., Potter D.R. Misfortunes or mistakes?. Cultural sensemaking of entrepreneurial failure. J. Bus. Ventur. 2011;26:79–92. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusvent.2009.06.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chien G.C.L., Law R. The impact of the severe acute respiratory syndrome on hotels: a case study of Hong Kong. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2003;22:327–332. doi: 10.1016/S0278-4319(03)00041-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creswell J.W. Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches. 4th ed. SAGE Publications,; Thousand Oaks, California: 2014. Research design: qualitative. [Google Scholar]

- Dahlberg R., Guay F. WIT Transactions on The Built Environment. WIT Press; 2015. Creating resilient SMEs: is business continuity management the answer? pp. 975–984. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Davidsson P., Gordon S.R. Much Ado About Nothing? The surprising persistence of nascent entrepreneurs through macroeconomic crisis. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2016;40:915–941. doi: 10.1111/etap.12152. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Doern R. Entrepreneurship and crisis management: the experiences of small businesses during the London 2011 riots. Int. Small Bus. J. Res. Entrep. 2016;34:276–302. doi: 10.1177/0266242614553863. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Doern R., Goss D. From barriers to barring: why emotion matters for entrepreneurial development. Int. Small Bus. J. 2013;31:496–519. doi: 10.1177/0266242611425555. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Doern R., Williams N., Vorley T. Entrepreneurship and crises: business as usual? Entrep. Reg. Dev. 2016;28:471–475. doi: 10.1080/08985626.2016.1198091. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Doern R., Williams N., Vorley T. Special issue on entrepreneurship and crises: business as usual? An introduction and review of the literature. Entrep. Reg. Dev. 2019;31:400–412. doi: 10.1080/08985626.2018.1541590. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Eggers F. Masters of disasters? Challenges and opportunities for SMEs in times of crisis. J. Bus. Res. 2020;116:199–208. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.05.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eggers F., Kraus S. Growing young SMEs in hard economic times: the impact of entrepreneurial and customer orientations — a qualitative study from silicon valley. J. Small Bus. Entrep. 2011;24:99–111. doi: 10.1080/08276331.2011.10593528. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ergun Ö., Heier Stamm J.L., Keskinocak P., Swann J.L. Waffle House Restaurants hurricane response: a case study. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2010;126:111–120. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpe.2009.08.018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Faisal A., Albrecht J.N., Coetzee W.J.L. Renegotiating organisational crisis management in urban tourism: strategic imperatives of niche construction. Int. J. Tour. 2020 doi: 10.1108/IJTC-11-2019-0196. (Cities ahead-of-print) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Folke, C., Carpenter, S.R., Walker, B., Scheffer, M., Chapin, T., Rockström, J., 2010. Resilience Thinking: Integrating Resilience, Adaptability and Transformability, JSTOR.

- Francis J.J., Johnston M., Robertson C., Glidewell L., Entwistle V., Eccles M.P., Grimshaw J.M. What is an adequate sample size? Oper. Data Satur. Theory Based Interview Stud. 2009;25:1229–1245. doi: 10.1080/08870440903194015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frandsen F., Johansen W. Pragmatics across Languages and Cultures. De Gruyter; 2010. Corporate crisis communication across cultures; pp. 543–570. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Galbraith C.S., Stiles C.H. Disasters and entrepreneurship: a short review. Int. Res. Bus. Discip. 2006:147–166. doi: 10.1016/S1074-7877(06)05008-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Garrido-Moreno A., García-Morales V.J., Martín-Rojas R. Going beyond the curve: strategic measures to recover hotel activity in times of COVID-19. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2021;96 doi: 10.1016/j.ijhm.2021.102928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GDA (Global Data Analysis), 2020. Coronavirus (COVID-19) Executive Briefing [WWW Document]. URL 〈https://www.business.att.com/content/dam/attbusiness/briefs/att-globaldata-coronavirus-executive-briefing.pdf〉 (accessed 6.8.20).

- Goulding C. Grounded theory, ethnography and phenomenology: a comparative analysis of three qualitative strategies for marketing research. Eur. J. Mark. 2005;39:294–308. doi: 10.1108/03090560510581782. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hao F., Xiao Q., Chon K. COVID-19 and China’s hotel industry: impacts, a disaster management framework, and post-pandemic agenda. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2020;90 doi: 10.1016/j.ijhm.2020.102636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hätty H., Hollmeier S. Airline strategy in the 2001/2002 crisis — The Lufthansa example. J. Air Transp. Manag. 2003;9:51–55. doi: 10.1016/S0969-6997(02)00064-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Henderson J.C. Corporate social responsibility and tourism: hotel companies in Phuket, Thailand, after the Indian Ocean tsunami. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2007;26:228–239. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhm.2006.02.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Herbane B. Exploring crisis management in UK small- and medium-sized enterprises. J. Contingencies Cris. Manag. 2013;21:82–95. doi: 10.1111/1468-5973.12006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hermann C.F. Some consequences of crisis which limit the viability of organizations. Adm. Sci. Q. 1963;8:61–82. [Google Scholar]

- Hošková-Mayerová, Š., 2016. Education and Training in Crisis Management. Cognitive-crcs, pp. 849–856. 10.15405/epsbs.2016.11.87. [DOI]

- Hystad P., Keller P. Disaster management: Kelowna tourism industry’s preparedness, impact and response to a 2003 major forest fire. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2006;13:44–58. doi: 10.1375/jhtm.13.1.44. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ingirige, M., Jones, K., Proverbs, D., 2008. Investigating SME resilience and their adaptive capacities to extreme weather events: A literature review and synthesis.

- Irvine W., Anderson A.R. Small tourist firms in rural areas: Agility, vulnerability and survival in the face of crisis. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2004;10:229–246. doi: 10.1108/13552550410544204. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Israeli A.A., Reichel A. Hospitality crisis management practices: the Israeli case. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2003;22:353–372. doi: 10.1016/S0278-4319(03)00070-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jia, Z., Shi, Y., Jia, Y., Li, D., 2012. A framework of knowledge management systems for tourism crisis management, in: Procedia Engineering. pp. 138–143. 10.1016/j.proeng.2011.12.683. [DOI]

- Kato M., Charoenrat T. Business continuity management of small and medium sized enterprises: evidence from Thailand. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2018;27:577–587. doi: 10.1016/j.ijdrr.2017.10.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kirillova K. Phenomenology for hospitality: theoretical premises and practical applications. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2018;30:3326–3345. doi: 10.1108/IJCHM-11-2017-0712. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Korber S., McNaughton R.B. Resilience and entrepreneurship: a systematic literature review. Int. J. Econ. Business Res. 2018;24:1129–1154. doi: 10.1108/IJEBR-10-2016-0356. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kuckertz A., Brändle L., Gaudig A., Hinderer S., Morales Reyes C.A., Prochotta A., Steinbrink K.M., Berger E.S.C. Startups in times of crisis – A rapid response to the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Bus. Ventur. Insights. 2020;13 doi: 10.1016/j.jbvi.2020.e00169. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Laverty S.M. Hermeneutic phenomenology and phenomenology: a comparison of historical and methodological considerations. Int. J. Qual. Methods. 2008;2:21–35. doi: 10.1016/S0742-051X(00)00023-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lee N., Cowling M. Place, sorting effects and barriers to enterprise in deprived areas: different problems or different firms? Int. Small Bus. J. Res. Entrep. 2013;31:914–937. doi: 10.1177/0266242612445402. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lee N., Sameen H., Cowling M. Access to finance for innovative SMEs since the financial crisis. Res. Policy. 2015;44:370–380. doi: 10.1016/j.respol.2014.09.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Leta S.D., Chan I.C.C. Learn from the past and prepare for the future: a critical assessment of crisis management research in hospitality. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2021;95 doi: 10.1016/j.ijhm.2021.102915. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lettieri E., Masella C., Radaelli G. Disaster management: findings from a systematic review. Disaster Prev. Manag. Int. J. 2009;18:117–136. doi: 10.1108/09653560910953207. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Linnenluecke M.K. Resilience in business and management research: a review of influential publications and a research agenda. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2017;19:4–30. doi: 10.1111/ijmr.12076. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lu Y., Wu J., Peng J., Lu L. The perceived impact of the Covid-19 epidemic: evidence from a sample of 4807 SMEs in Sichuan Province, China. Environ. Hazards. 2020:1–18. doi: 10.1080/17477891.2020.1763902. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Martinelli E., Tagliazucchi G., Marchi G. The resilient retail entrepreneur: dynamic capabilities for facing natural disasters. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2018;24:1222–1243. doi: 10.1108/IJEBR-11-2016-0386. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McKinsey & Company, 2020. Coronavirus’ business impact: Evolving perspective | McKinsey [WWW Document]. URL 〈https://www.mckinsey.com/business-functions/risk/our-insights/covid-19-implications-for-business〉 (accessed 6.7.20).

- Memon, N.A., 2016. Fast Food: Second largest industry in Pakistan [WWW Document]. Food J.