Abstract

The COVID-19 pandemic forced the worldwide introduction of containment measures. This emergency scenario produced a conflict between personal freedom and public health, highlighting differences in individual behaviours influenced by psychological traits and moral considerations. In this context, a detailed characterisation of the psychological variables predicting adherence to containment measures is crucial to enhance public awareness and compliance.

During the first virus outbreak in Italy, we assessed whether adherence to government measures was explained by the interacting effects of personality traits and moral dispositions. Through an online questionnaire, we collected data on individual endogenous variables related to personality traits, locus of control, and moral dispositions, alongside the tendency to breach the lockdown for outdoor physical activity. The results showed that individual measures of novelty-seeking, harm-avoidance and authority concerns interacted in driving the adherence to the national lockdown: MFQ-Authority moderated the facilitatory effect of novelty-seeking on lockdown violation, but this moderation was itself moderated by higher TCI-harm-avoidance. By assessing a model forecasting the likelihood of violating restrictive norms, these findings show the potential of personality and moral foundation assessments in informing prevention policies and emergency interventions by political and scientific institutions.

Keywords: COVID-19, Lockdown, Personality, Moral cognition, Novelty-seeking, Harm-avoidance, Respect for authority, Moderated-moderation

1. Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic forced the sudden introduction of measures limiting freedom of movement and social interactions (Chaudhry, Dranitsaris, Mubashir, Bartoszko, & Riazi, 2020), raising a heated debate concerning the conflict between individual rights and collective well-being. This emergency therefore represented a “natural experiment” for behavioural scientists, allowing both to investigate the attitudes and choices of single individuals facing their possible consequences, and to assess the effectiveness of strategies aimed to favour socially-oriented adaptive behaviours (Bavel et al., 2020).

A pandemic scenario, with its global health implications, is indeed expected to enhance the role of different variables in shaping people's willingness to make collective well-being prevail over personal interests (Shi, Qi, Ding, Liu, & Shen, 2020; Zaki, 2020). The individual endogenous variables shaping behavioural intentions, and thus possibly modulating behavioural responses to emergency situations (e.g. compliance with containment measures; Miguel, Machado, Pianowski, & Carvalho, 2021), include relatively stable dimensions such as personality traits (Cloninger, Przybeck, Svrakic, & Wetzel, 1994; Zajenkowski, Jonason, Leniarska, & Kozakiewicz, 2020), the perceived degree of control over events (Locus of control; Craig, Franklin, & Andrews, 1984) and moral dispositions (Theory of Moral Foundations; Haidt, 2008; Qian & Yahara, 2020). Identifying the psychological precursors of choices involving conflicts between utilitarian vs. prosocial consideration is not only relevant for behavioural research (to unveil the drivers of individual differences in decision-making attitudes), but it might also inform targeted public health interventions and communication strategies aiming at increasing awareness and compliance in the population (Bavel et al., 2020).

To this purpose, we used conditional process analysis on the outcome of well-established psychometric scales to explore the variables modulating behavioural intentions during the lockdown in Italy. We decided to focus on the intended behaviour of leaving home to perform outdoor individual physical activity; this behaviour was, in fact, exemplary of a situation in which participants had a certain degree of control, as it was neither strictly necessary (e.g. purchasing essential goods) nor externally mandated (e.g. going to work). Data were collected through an online questionnaire detecting demographic information and individual endogenous variables related to personality traits, locus of control, and moral dispositions, alongside the tendency to respect vs. violate the lockdown. We focused on the psychological dimensions that, based on the available literature, seemed more likely to influence people's behavioural intentions during the lockdown. One such dimension is novelty-seeking, which is known to reflect a marked tendency to cheerful and euphoric states, promoting exploration, avoidance of routine and monotony, and low resistance in case of persistent frustrations (Mardaga & Hansenne, 2007). It was indeed shown that novelty-seeking contributed to shaping attitudes in multiple ways during COVID-19 home quarantine (Liang et al., 2020), i.e. by promoting the need for high levels of stimulation to avoid boredom, impulsive decision-making, and dysfunctional coping strategies (Estedlal et al., 2021), while concurrently helping to manage difficulties and preserve mental health (Li, Yu, Miller, Yang, & Rouen, 2020). Based on this evidence, we expected novelty-seeking to be a predictor of a higher disposition to leave home for outdoor physical activity despite possible negative consequences. Furthermore, we anticipated that this effect might be mediated by the perceived degree of control over events (i.e. locus of control). We additionally hypothesized that the effect of novelty-seeking on intended lockdown violation might be moderated by fearful attitudes towards contagion and disease consequences (i.e. harm-avoidance personality trait; Cloninger, 1993; Mardaga & Hansenne, 2007) as well as by moral dispositions towards compliance with rules (i.e. respect for authority; O'Grady, Vandegrift, Wolek, & Burr, 2019; Qian & Yahara, 2020). Importantly, the limitation to individual outdoor physical activity was strongly debated in Italy (Camporesi, 2020) because of its unclear link with other restrictions (e.g. social distancing and use of face masks, predicted by caring and fairness in Chan, 2021), but still largely met by the population and strictly enforced by competent authorities. Among the moral foundations (Haidt, 2008), we thus predicted a role for authority, which encompassed adherence to rules and the refusal to break them to avoid being sanctioned. Based on the nature of both harm-avoidance and respect for authority, we anticipated interactive effects of these moderating variables, which were assessed through a moderated-moderation model (Hayes, 2017) after checking for their contribution to the dependent variable.

2. Materials and methods

Further details are reported in Supplementary materials.

2.1. Participants

465 participants completed the survey during the first full national lockdown in Italy. Eleven subjects were excluded either because they reported a previous COVID-19 contagion (n = 10) or because they were identified as outliers based on Malhanobis distance (n = 1). The final sample included 318 females and 136 males, aged 18–82 years old (Supplementary Table 1).

2.2. Study design

Data were collected online with LimeSurvey (https://www.limesurvey.org/en/). Participants were recruited through online advertisements on social networks (Twitter, Facebook, LinkedIn), and word of mouth. Participants were required to be aged >18, and native or proficient Italian speakers. The experimental protocol was approved by the local Ethics Committee of the University of Pavia (Italy) prior to the beginning of data collection. When entering the survey, participants were provided the general aims of the survey and related procedures (data anonymisation, analyses, future use and sharing), and asked to give their informed consent to the procedure.

2.3. Baseline predictors of compliance with the lockdown

2.3.1. Socio-demographic data and COVID-19-related attitudes and behaviours

The first part of the survey collected data regarding age, gender, education level and contact with COVID-19 cases. Then, via a slider with hidden numerical values, participants reported the likelihood of leaving home, in the following week, for the purpose of outdoor physical activity.

2.3.2. Locus of control

Participants were administered the Italian translation (Farma & Cortinovis, 2001) of Craig et al.'s (1984) scale, consisting of two subscales for internal vs. external Locus of control. The difference between the two subscales was used as a synthetic measure of internal (vs. external) Locus of control.

2.3.3. Moral cognition

We assessed the personal sensitivity to different facets of moral cognition with the Italian translation (Bobbio, Nencini, & Sarrica, 2011) of the Moral Foundation Questionnaire (MFQ; Graham, Haidt, & Nosek, 2008), a self-report measure assessing individual priorities among five domains: harm/care (protecting vulnerable individuals from harm), fairness/reciprocity (concern about fairness and social justice), ingroup/loyalty (concern for self-sacrifice for the group), authority/respect (concern for obedience, leadership, and protection), and purity/sanctity (concern for purity and protection from contamination).

2.3.4. Personality

We assessed different facets of personality using the Italian translation (Fossati et al., 2007) of the reduced Temperament and Character Inventory (TCI-56; Adan, Serra-Grabulosa, Caci, & Natale, 2009). In particular, we focused on TCI's four temperament dimensions: harm-avoidance, novelty-seeking, reward-dependence, and persistence, reflecting behavioural inhibition/punishment, behavioural activation/reward, social reinforcement/sensitivity to social stimuli, and the tendency to maintain behaviour in extinction conditions, respectively (Adan et al., 2009).

2.4. Statistical analyses

Preliminary simple regression analyses confirmed that the tendency to leave home for physical activity was positively predicted by novelty-seeking, and negatively predicted by harm-avoidance and MFQ-Authority (p < 0.05, one-tailed). No significant relationship was observed with any of the locus of control measures. A multiple regression model showed that the dependent variable was not predicted by novelty-seeking and locus of control, which led to reject a model in which the latter variable mediates the effect of novelty-seeking. We thus included the remaining variables in simple moderation models to assess whether the effect of novelty-seeking on lockdown violation is moderated by MFQ-authority and/or TCI-harm-avoidance. Since only the former variable was a significant moderator (3.2), we assessed a moderated-moderation model in which the moderation, by MFQ-authority, of the effect of novelty-seeking on lockdown violation is itself moderated by TCI-harm-avoidance. Age, educational level and COVID-19 cases among acquaintances were modelled as nuisance variables. We used the PROCESS macro (v.3.5) for SPSS (IBM, v.23), after checking assumptions concerning multicollinearity, linearity of the relationship between dependent and independent variables, independence of residuals, and homoscedasticity. Conditional process analysis was run based on Ordinary Least Squares regression, using bootstrapping resampling (50,000 samples) to estimate 95% confidence intervals. The statistical threshold was set at p < 0.05 (two-tailed).

The internal consistency and structure of the TCI-temperament subscale and MFQ were assessed with Cronbach's alpha and an exploratory factorial analysis with oblique rotation, respectively. Factor extraction was guided by a minimum eigenvalue of 0.7 (Jolliffe, 1972) and scree plot examination. In addition to theoretical considerations concerning the items' conceptual meaning, we assessed the latent structure by setting a threshold of factor loading ≥0.40.

3. Results

3.1. Socio-demographic and personality variables

The socio-demographic and psychological characteristics of the sample are reported in Supplementary Table 1.

3.2. Moderated-moderation

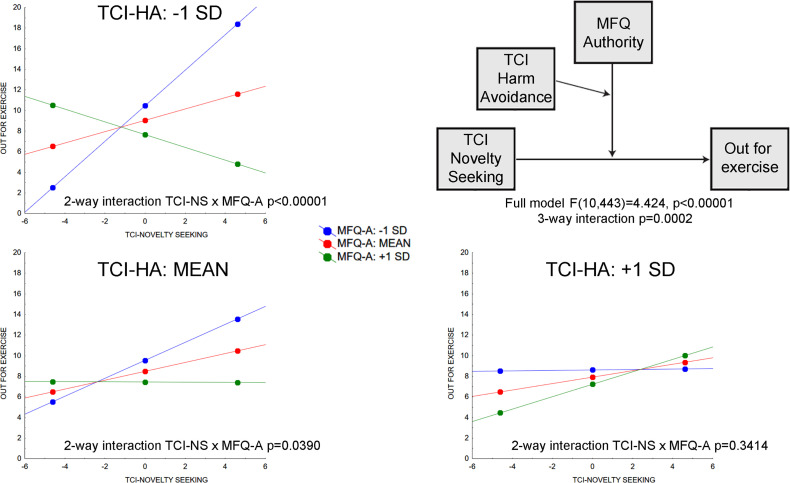

The facilitatory effect of TCI-novelty-seeking on leaving home for physical activity was significantly moderated by MFQ-Authority (F(1,447) = 7.405, p = 0.007), but not by TCI-harm-avoidance (F(1,447) = 1.838, p = 0.175). We thus assessed a moderated-moderation model in which the moderation, by MFQ-authority, of the effect of novelty-seeking on lockdown violation is itself moderated by TCI-harm-avoidance. A significant model (F(10,443) = 4.424, p < 0.00001), explaining about 9% of the variance of the dependent variable, showed that higher novelty-seeking predicted a larger tendency to violate the lockdown for physical activity (p = 0.042, Fig. 1 ). Even though MFQ-Authority and harm-avoidance were not significantly related to the dependent variable, the three-way interaction among these three variables was significant (F(1,443) = 13.746, p = 0.0002) (Fig. 1, Table 1 ). Namely, we observed a significant two-way interaction between novelty-seeking and MFQ-Authority (p = 0.039), which, however, depends on harm-avoidance. This interaction was indeed significant at low (−1 SD; p < 0.00001) and medium (p = 0.039) harm-avoidance, when higher MFQ-Authority moderates, by inhibiting it, the positive relationship between novelty-seeking and the tendency to violate the lockdown. Instead, no significant interaction between novelty-seeking and MFQ-Authority was found at higher harm-avoidance levels (+1 SD; p = 0.341).

Fig. 1.

The conceptual model shown in the top-right figure sector depicts the moderated-moderation (three-way interaction) pattern displayed in the other panels, with respect for authority inhibiting the facilitatory effect of novelty-seeking on leaving home for exercise, but only at low and medium levels of harm-avoidance.

Table 1.

Coefficients and 95% confidence intervals of moderated-moderation for predicting the adherence to lockdown.

| Model summary | R | R2 | MSE | F | df | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.3013 | 0.0908 | 440.0524 | 4.4244 | 10, 443 | <0.00001 | |

| Model | coeff | se | t | p | LLCI | ULCI |

| TCI-novelty-seeking | 0.4623 | 0.2267 | 2.0392 | 0.042 | 0.0167 | 0.9078 |

| TCI-novelty-seeking × MFQ-Authority | −0.5017 | 0.2424 | −2.0699 | 0.039 | −0.978 | −0.0253 |

| TCI-novelty-seeking × MFQ-Authority × TCI-harm-avoidance | 0.1508 | 0.0407 | 3.7075 | 0.0002 | 0.0709 | 0.2307 |

| Gender | −5.2252 | 2.2612 | −2.3108 | 0.0213 | −9.6692 | −0.7812 |

| Test of conditional “TCI-Novelty seeking × MFQ-Authority” interaction at values of TCI-Harm avoidance | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TCI-harm-avoidance | Effect | F | df1 | df2 | p |

| −5.5984 | −1.3459 | 19.7354 | 1 | 443 | <0.00001 |

| 0 | −0.5017 | 4.2845 | 1 | 443 | 0.039 |

| 5.5984 | 0.3426 | 0.907 | 1 | 443 | 0.3414 |

Notes. MMSE: Mean Squared Error; df: degrees of freedom; LLCI: lower level of confidence interval; ULCI: upper level of confidence interval; coeff: coefficient; se: standard error. See Supplementary Table 3 for the complete set of results. Bold font denotes p < 0.05.

3.3. Internal consistency

We observed adequate reliability and internal structure for both the temperament subscale of TCI-56 and MFQ (Supplementary results). An exploratory factorial analysis confirmed that the structure of TCI-temperament and MFQ was explained by 4 and 5 factors, respectively, with minimum eigenvalue = 0.86. For all the variables modelled in statistical analyses, the resulting factors generally confirmed the item-dimension association as in the original scales.

4. Discussion

The COVID-19 pandemic has dramatically revealed the effects of individual actions on virus spread, and therefore their impact on collective well-being (Brooks et al., 2020). In this context, public awareness and compliance with containment measures might be greatly enhanced by a detailed characterisation of the psychological variables predicting the adherence to lockdown. We pursued this goal by assessing the extent to which participants' adherence to restrictive norms was explained by the interacting effects of moral dispositions and personality traits such as novelty-seeking and harm-avoidance. We selected these variables in light of their mutual relationship and previous findings that behavioural adaptations to emergency situations reflect cautious attitude, but also other-regarding moral dispositions (O'Grady et al., 2019). Supporting this view, the interaction among these variables predicted individual differences in the tendency to violate lockdown measures.

A few recent studies assessed the impact of psychometric demographic measures on the compliance with the rules in different countries during the pandemic, particularly during the first lockdown (Clark, Davila, Regis, & Kraus, 2020; Kooistra & Rooij, 2020). According to research using personality scales, particularly the Big Five Inventory (BFI, McCrae & Costa, 1987; McCrae & John, 1992), compliance with the restrictions was directly related to neuroticism and inversely related to extraversion. This result appeared to be cross-cultural and irrespective of specific governmental restrictions (Götz et al., 2021). Other studies showed that extraverted individuals might be more reluctant to comply with social distancing (Han, 2021), and high extraversion negatively predicted both social distancing and reduced mobility (Chan et al., 2020; Krupić, Žuro, & Krupić, 2021). High levels of neuroticism, instead, were associated with fear of developing diseases and avoidance of germs (Duncan, Schaller, & Park, 2009), and with the avoidance of settings that may lead to infection (Oosterhoff, Shook, & Iyer, 2018), thus resulting in increased compliance with COVID-19 restrictions (Kohút, Kohútová, & Halama, 2021). In the present study we additionally considered the moral foundation of authority, based on the notion that neuroticism leads to a more sensitive reaction to punishment and threat cues (Blüml et al., 2013). Notably, both extraversion and neuroticism are positively correlated with the TCI traits included in our model, i.e. novelty-seeking and harm-avoidance respectively (De Fruyt, Van De Wiele, & Van Heeringen, 2000), strengthening the hypothesis that some BFI factors and TCI traits overlap.

As to the trade-off between individual and collective well-being, we expected that oppositely directed personality traits as novelty-seeking and harm-avoidance might predict individual differences in this direction (Mardaga & Hansenne, 2007). In line with this hypothesis, novelty-seeking was a significant predictor of the intention to leave home for physical activity. When strict lockdown measures are in place, and thus sources of external stimulation and social contacts are limited, outdoor sport activities might emerge as the main outlet to seek novel sensations and overcome impending boredom (Liang et al., 2020; McCourt, Gurrera, & Cutter, 1993). The effect of novelty-seeking was moderated by the individual sensitivity to authority, which overall decreased its facilitating effect on breaking the confinement for outdoor sports. Even though it does not predict spontaneous prosocial behaviour (O'Grady & Vandegrift, 2019), the legitimation of authority is an inherent precursor of compliance with rules, particularly with weak motives for acting differently. Importantly, however, such a moderating effect was itself moderated by harm-avoidance, likely reflecting the fear of contagion and its consequences regardless of one's own sensitivity to authority. This temperament trait, characterised by excessive caution, apprehension, and pessimism (De Fruyt et al., 2000), is indeed typically associated with higher unconscious emotional responses (Yoshino, Kimura, Yoshida, Takahashi, & Nomura, 2005), pain perception (Pud, Eisenberg, Sprecher, Rogowski, & Yarnitsky, 2004) and subsequent anticipatory avoidance behaviour. By showing that higher levels of respect for authority are required, for lockdown adherence, at lower levels of harm-avoidance, the present findings highlight two interacting drivers of behavioural attitudes concerning health-related choices during the pandemic. These results might thus inform public health policies (Soofi, Najafi, & Karami-Matin, 2020), and contribute to develop public interventions tailored to different target groups promoting appropriate behaviours (Bavel et al., 2020). In particular, our results highlight the importance of adapting strategies to different personalities: for instance, by developing initiatives promoting respect for authority in groups characterised by low harm-avoidance, of which extreme sports practitioners represent an exemplary case (Monasterio et al., 2016), while taking into consideration that threats and sanctions may lead to opposite effects (Houdek, Koblovský, & Vranka, 2021). Instead, for those lacking trust in authorities, such as individuals with higher psychological entitlement (Harvey & Martinko, 2009) who tend to prioritise their own health when taking decisions (Daddis & Brunell, 2015), compliance might be enhanced by clearer and non-contradictory information on the risks for their own health in case of infection (Zitek & Schlund, 2021). Considering the age of our sample, however, it should be examined whether these recommendations would also apply to more vulnerable age groups.

Despite promising results, we also acknowledge that online studies have some inherent limitations compared to laboratory settings. First, this approach required simplified procedures for assessing participants' attitudes and intentions, possibly resulting in decreased data quality and smaller effect sizes. We addressed this issue by performing a formal inspection of consistency/reliability of the data resulting from psychometric scales. From an applied standpoint, however, it is worth noting that even relatively small effects can have major implications in the occurrence of global scale events (Götz et al., 2021). Second, online surveys typically involve inhomogeneous samples that, by favouring young adults over elderly, cannot be considered representative of the whole population. However, while elderly participants are those at the highest risk for severe health consequences, young adults constitute a highly informative sample: while being a likely vehicle of under-traced virus spread due to their higher work and social commitments (Dowd et al., 2020), they might also represent the ideal target for disseminating and incentivising correct health behaviours, such as the use of masks, specifically because of their central social role (Bavel et al., 2020) and proximity to parents and older relatives.

5. Conclusions

We highlighted a multifaceted set of psychological variables predicting compliance with the lockdown during the first virus outbreak in Italy. Personality traits, such as novelty-seeking and harm-avoidance, and the authority moral foundation, were shown to play interacting roles in the adherence to containment measures. By assessing a model whose aim was to forecast the likelihood of violating restrictive norms, the present findings provide novel insights that might extend beyond the current pandemic context. From a broader perspective, these results show how personality and moral foundation assessments can inform prevention policies and emergency interventions by political and scientific institutions.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Sara Lo Presti: Conceptualization, Data curation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Giulia Mattavelli: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Nicola Canessa: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Claudia Gianelli: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Acknowledgements

This research was partially supported by the “Ricerca Corrente” funding scheme of the Italian Ministry of Health. We wish to thank Maria Vittoria Fronda for language editing. The authors have no financial interests relating to the work described and declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2021.111090.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary material

References

- Adan A., Serra-Grabulosa J.M., Caci H., Natale V. A reduced Temperament and Character Inventory (TCI-56). Psychometric properties in a non-clinical sample. Personality and Individual Differences. 2009;46(7):687–692. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2009.01.023. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bavel J.J.V., Baicker K., Boggio P.S., Capraro V., Cichocka A., Cikara M.…Willer R. Using social and behavioural science to support COVID-19 pandemic response. Nature Human Behaviour. 2020;4(5):460–471. doi: 10.1038/s41562-020-0884-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blüml V., Kapusta N.D., Doering S., Brähler E., Wagner B., Kersting A. Personality factors and suicide risk in a representative sample of the German general population. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(10) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0076646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bobbio A., Nencini A., Sarrica M. Il Moral Foundation Questionnaire: Analisi della struttura fattoriale della versione italiana. Giornale di Psicologia. 2011;5:7–18. [Google Scholar]

- Brooks S.K., Webster R.K., Smith L.E., Woodland L., Wessely S., Greenberg N., Rubin G.J. The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: Rapid review of the evidence. The Lancet. 2020;395(10227):912–920. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30460-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camporesi S. It Didn’t have to be this way reflections on the ethical justification of the running ban in northern Italy in response to the 2020 COVID-19 outbreak. Journal of Bioethical Inquiry. 2020;17(4):643–648. doi: 10.1007/s11673-020-10056-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan E.Y. Moral foundations underlying behavioral compliance during the COVID-19 pandemic. Personality and Individual Differences. 2021;171 doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2020.110463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan H.F., Moon J.W., Savage D.A., Skali A., Torgler B., Whyte S. Can psychological traits explain mobility behavior during the COVID-19 pandemic? Social Psychological and Personality Science. 2020 doi: 10.1177/1948550620952572. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chaudhry R., Dranitsaris G., Mubashir T., Bartoszko J., Riazi S. A country level analysis measuring the impact of government actions, country preparedness and socioeconomic factors on COVID-19 mortality and related health outcomes. EClinicalMedicine. 2020;25 doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2020.100464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark C., Davila A., Regis M., Kraus S. Predictors of COVID-19 voluntary compliance behaviors: An international investigation. Global Transitions. 2020;2:76–82. doi: 10.1016/j.glt.2020.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cloninger C.R. A psychobiological model of temperament and character. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1993;50(12):975. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1993.01820240059008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cloninger C.R., Przybeck T.R., Svrakic D.M., Wetzel R.D. Washington University, Center for Psychobiology of Personality; Louis: 1994. The temperament and character inventory (TCI): A guide to its development and use. S. [Google Scholar]

- Craig A.R., Franklin J.A., Andrews G. A scale to measure locus of control of behaviour. British Journal of Medical Psychology. 1984;57(2):173–180. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8341.1984.tb01597.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daddis C., Brunell A.B. Entitlement, exploitativeness, and reasoning about everyday transgressions: A social domain analysis. Journal of Research in Personality. 2015;58:115–126. doi: 10.1016/j.jrp.2015.07.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- De Fruyt F., Van De Wiele L., Van Heeringen C. Cloninger’s psychobiological model of temperament and character and the five-factor model of personality. Personality and Individual Differences. 2000;29(3):441–452. doi: 10.1016/S0191-8869(99)00204-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dowd J.B., Andriano L., Brazel D.M., Rotondi V., Block P., Ding X.…Mills M.C. Demographic science aids in understanding the spread and fatality rates of COVID-19. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2020;117(18):9696–9698. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2004911117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan L.A., Schaller M., Park J.H. Perceived vulnerability to disease: Development and validation of a 15-item self-report instrument. Personality and Individual Differences. 2009;47(6):541–546. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2009.05.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Estedlal A.R., Mani A., Vardanjani H.M., Kamali M., Zarei L., Heydari S.T., Lankarani K.B. Temperament and character of patients with alcohol toxicity during COVID − 19 pandemic. BMC Psychiatry. 2021;21(1):49. doi: 10.1186/s12888-021-03052-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farma T., Cortinovis I. Un questionario sul “Locus of Control”: Suo utilizzo nel contesto italiano. Ricerca in Psicoterapia. 2001;1 [Google Scholar]

- Fossati A., Cloninger C.R., Villa D., Borroni S., Grazioli F., Giarolli L.…Maffei C. Reliability and validity of the Italian version of the temperament and character inventory-revised in an outpatient sample. Comprehensive Psychiatry. 2007;48(4):380–387. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2007.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Götz F.M., Gvirtz A., Galinsky A.D., Jachimowicz J.M. How personality and policy predict pandemic behavior: Understanding sheltering-in-place in 55 countries at the onset of COVID-19. American Psychologist. 2021;76(1):39–49. doi: 10.1037/amp0000740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham, J., Haidt, J., & Nosek, B. (2008). The Moral Foundations Questionnaire. www.moralfoundations.org.

- Haidt J. Perspectives on Psychologica006C Science; 2008. Morality. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han H. Exploring the association between compliance with measures to prevent the spread of COVID-19 and big five traits with Bayesian generalized linear model. Personality and Individual Differences. 2021;176 doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2021.110787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey P., Martinko M.J. An empirical examination of the role of attributions in psychological entitlement and its outcomes. Journal of Organizational Behavior. 2009;30(4):459–476. doi: 10.1002/job.549. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes A.F. 2nd ed. Guilford Press; New York, NY: 2017. Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. [Google Scholar]

- Houdek, P., Koblovský, P., & Vranka, M. (2021). The challenge of human psychology to effective management of the COVID-19 pandemic. Society. doi: 10.1007/s12115-021-00575-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Jolliffe I.T. Discarding variables in a principal component analysis. I: Artificial data. Applied Statistics. 1972;21(2):160. doi: 10.2307/2346488. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kohút M., Kohútová V., Halama P. Big Five predictors of pandemic-related behavior and emotions in the first and second COVID-19 pandemic wave in Slovakia. Personality and Individual Differences. 2021;180 doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2021.110934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kooistra, E. B., & Rooij, B. van. (2020). Pandemic compliance: A systematic review of influences on social distancing behaviour during the first wave of the COVID-19 outbreak. PsyArXiv. doi:10.31234/osf.io/c5x2k.

- Krupić D., Žuro B., Krupić D. Big Five traits, approach-avoidance motivation, concerns and adherence with COVID-19 prevention guidelines during the peak of pandemic in Croatia. Personality and Individual Differences. 2021;179 doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2021.110913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li W.W., Yu H., Miller D.J., Yang F., Rouen C. Novelty seeking and mental health in Chinese university students before, during, and after the COVID-19 pandemic lockdown: A longitudinal study. Frontiers in Psychology. 2020;11 doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.600739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang, Z., Zhao, Q., Zhou, Z., Yu, Q., Li, S., & Chen, S. (2020). The effect of “novelty input” and “novelty output” on boredom during home quarantine in the COVID-19 pandemic: The moderating effects of trait creativity. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 601548. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.601548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Mardaga S., Hansenne M. Relationships between Cloninger’s biosocial model of personality and the behavioral inhibition/approach systems (BIS/BAS) Personality and Individual Differences. 2007;42(4):715–722. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2006.08.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McCourt W.F., Gurrera R.J., Cutter H.S.G. Sensation seeking and novelty seeking: Are they the same? The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 1993;181(5):309–312. doi: 10.1097/00005053-199305000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCrae R.R., Costa P.T. Validation of the five-factor model of personality across instruments and observers. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1987;52(1):81–90. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.52.1.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCrae R.R., John O.P. An introduction to the five-factor model and its applications. Journal of Personality. 1992;60(2):175–215. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.1992.tb00970.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miguel F.K., Machado G.M., Pianowski G., Carvalho L.d.F. Compliance with containment measures to the COVID-19 pandemic over time: Do antisocial traits matter? Personality and Individual Differences. 2021;168 doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2020.110346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monasterio E., Mei-Dan O., Hackney A.C., Lane A.R., Zwir I., Rozsa S., Cloninger C.R. Stress reactivity and personality in extreme sport athletes: The psychobiology of BASE jumpers. Physiology & Behavior. 2016;167:289–297. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2016.09.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Grady T., Vandegrift D. Moral foundations and decisions to donate bonus to charity: Data from paid online participants in the United States. Data in Brief. 2019;25 doi: 10.1016/j.dib.2019.104331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Grady T., Vandegrift D., Wolek M., Burr G. On the determinants of other-regarding behavior: Field tests of the moral foundations questionnaire. Journal of Research in Personality. 2019;81:224–237. doi: 10.1016/j.jrp.2019.06.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Oosterhoff B., Shook N.J., Iyer R. Disease avoidance and personality: A meta-analysis. Journal of Research in Personality. 2018;77:47–56. doi: 10.1016/j.jrp.2018.09.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pud D., Eisenberg E., Sprecher E., Rogowski Z., Yarnitsky D. The tridimensional personality theory and pain: Harm avoidance and reward dependence traits correlate with pain perception in healthy volunteers. European Journal of Pain. 2004;8(1):31–38. doi: 10.1016/S1090-3801(03)00065-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qian K., Yahara T. Mentality and behaviour in COVID-19 emergency status in Japan: Influence of personality, morality and ideology. PLoS ONE. 2020;15(7) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0235883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi R., Qi W., Ding Y., Liu C., Shen W. Under what circumstances is helping an impulse? Emergency and prosocial traits affect intuitive prosocial behavior. Personality and Individual Differences. 2020;159 doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2020.109828. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Soofi M., Najafi F., Karami-Matin B. Using insights from behavioral economics to mitigate the spread of COVID-19. Applied Health Economics and Health Policy. 2020;18(3):345–350. doi: 10.1007/s40258-020-00595-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshino A., Kimura Y., Yoshida T., Takahashi Y., Nomura S. Relationships between temperament dimensions in personality and unconscious emotional responses. Biological Psychiatry. 2005;57(1):1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2004.09.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zajenkowski M., Jonason P.K., Leniarska M., Kozakiewicz Z. Who complies with the restrictions to reduce the spread of COVID-19?: Personality and perceptions of the COVID-19 situation. Personality and Individual Differences. 2020;166 doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2020.110199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaki J. Catastrophe compassion: Understanding and extending Prosociality under crisis. Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 2020;24(8):587–589. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2020.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zitek E.M., Schlund R.J. Psychological entitlement predicts noncompliance with the health guidelines of the COVID-19 pandemic. Personality and Individual Differences. 2021;171 doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2020.110491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material