Abstract

COVID-19 pandemic negatively affected the restaurant industry and reopening provides restaurants an opportunity to survive this crisis. This study examined the interplay of perceived importance of preventive measures, dining involvement, brand trust, and customers’ intention to dine out at American Chinese restaurants during the reopening period. Additionally, the study investigated the moderating role of country-of-origin (COO) effect on these relationships. 296 U.S. restaurant customers recruited via a market research company completed the online survey. Structural equation modeling was used for data analyses. The results indicated that dining involvement had a direct positive effect on customers’ intention to dine out. Moreover, both perceived importance of preventive measures and dining involvement could enhance customers’ intention to dine out indirectly via brand trust. Positive COO effect moderated the relationship between perceived importance of preventive measures and brand trust. The study provided significant implications for restaurant operators in the U.S during the reopening period.

Keywords: COVID-19, Preventive measures, Dining involvement, Brand trust, Country-of-origin, Intention

1. Introduction

COVID-19, a disease caused by a novel coronavirus, has recently spread throughout the world. The United States (U.S.) currently tops the world with the highest number of confirmed cases (World Health Organization [WHO], 2010). In response to this pandemic, the U.S. government has promulgated various regulations and guidelines (e.g., social distancing, face covering requirement), to slow down the spread of the virus. Multiple states also shut down nonessential businesses, such as dine-in restaurants and other leisure services, as another preventive measure at the beginning of the pandemic (Schumaker, 2020). As a result, the unemployment rate in the food and beverage (F&B) industry, as one of the more labor-intensive sectors, reached 39.3 % in April, which is an increment of more than 31 % from March 2020 (Bureau of Labor Statistics [BLS], 2020).

Compared to food delivery, carry-out, and drive-through services, dine-in service provides more work and employment opportunities, particularly for those in waitstaff positions. Therefore, the government’s plans for reopening dine-in services for restaurants are essential for economic recovery (Lantry et al., 2020). To reopen safely, restaurants are required to follow the preventive measures published by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and/or the National Restaurant Association (NRA), such as wearing masks, maintaining social distancing, reducing occupancy to 50 %, providing hand sanitizer that contains at least 60 % alcohol in public, or cleaning and disinfecting frequently touched objects and surfaces. However, restaurants in several states have been reported to violate the COVID-19 guidelines. For example, Lin et al. (2020) reported in Los Angeles Times that in June, 44 % employees in restaurants located in did not wear masks properly to cover face and mouth. More than 500 restaurants and bars in the New York states were facing COIVD-19 related charges due to failure to be compliance with the requirements (NYdatabase, 2020). In contrary, some restaurants have strictly followed the guidelines and implement additional rules for employees and customers (Lucas, 2020). At the present time, few studies have examined how customers perceived the importance of preventive measures adopted by restaurants and their impact on customers’ intentions to dine out during the reopening period. Understanding how customers view these preventive measures could help restauranteurs better strategize its implementation.

In addition, customers’ involvement is a key factor that impacts their behavior (Muncy and Hunt, 1984). In this study, dining involvement was defined as the perceived importance of dining out at the restaurants and the general pursuit of food options based on customers’ values and interests. Zaveri (2020) has suggested that “quarantine fatigue” has motivated individuals to go beyond their household boundaries. Though it can be assumed that individuals with high involvement in dining and food served at a restaurant would have higher intentions to dine out after “quarantine,” more empirical data is needed to demonstrate the established evidence to support this assumption.

Another factor that is relevant to dining intentions is brand trust, which refers to customers’ perceived values and reliance on a particular brand (Godfrey, 2005; Herbst et al., 2012; Riorini and Widayati, 2016; Sahin et al., 2011; Srivastava et al., 2016). Customers have more trust in restaurants that are reliable and exhibit some concerns for their health and safety (Cha and Borchgrevink, 2019). Thus, restaurants that have implemented efficient preventive measures during the pandemic may receive a higher level of customer trust. Starr (2020) indicated that some customers were appreciative of restaurants that had strict preventive measures and were willing to pay more, which resulted in a long-term benefit to the brand trust. On the other hand, some customers were not receptive to the preventive measures, believing that they would survive the COVID-19 pandemic and following these preventive measures would negatively impact their current lifestyles (Haischer et al., 2020). Therefore, the perceived importance of preventive measures may indirectly impact customers’ intentions to dine out via brand trust. At the same time, establishing a safe dining environment could result in brand trust during the pandemic (Kim et al., 2020a, b). Because highly involved customers may develop a higher level of trust towards the restaurants that signal their ability to establish a safe dining environment than the low involved customers, it was believed that dining involvement may also indirectly impact customers’ intention to dine out via brand trust during the reopening period.

The image of the country-of-origin (COO) also plays an important role in customers’ product choices and purchasing behaviors. Previous studies have indicated that customers’ perceptions of a country’s image may contribute to their decision-making processes, and this is known as the COO effect (e.g., Bilkey and Nes, 1982; Johansson et al., 1985; Maheswaran, 1994). A positive COO effect would therefore enhance customers’ trust and intentions to purchase. China reported the first coronavirus case but was managed to contain it in a short time period (Burki, 2020). Evidence showed that stigma exists during COVID-19, and some people are associated the pandemic with China (Budhwani and Sun, 2020). Budhwani and Sun (2020) found that tweets about “Chinese virus” or “China virus” have increased ten-fold post-period (2020) compared to pre-pandemic. There were 4.08 stigmatizing tweets per 10, 000 population (post-period) compared to 0.38 (pre-period). It is possible that different customers may have associated China with the COVID-19 pandemic to a various level, thus affecting their decisions to select any China-related products to a certain extent.

The present study focuses on American Chinese restaurants, since most of these restaurants have embraced American tastes, employed American employees, and targeted American customers while being managed by Americans (Liu and Jang, 2009), but they may still signify China, and customers may associate these restaurants with China’s country image. Understanding how the COO effect caused by China’s country image impacts restaurant customers’ perceived importance of preventive measures, brand trust, and intentions to dine out during the reopening period will allow American Chinese restaurant operators to better prepare themselves for the reopening and to attract more business and survive the crisis.

The objective of this study was to examine factors affecting customer’s intention to dine at the restaurant during the reopening period. More specifically, the study aims to examine the interplay between customers’ perceptions of the enacted preventive measures, dining involvement, brand trust, and intentions to dine at American Chinese restaurants during the reopening period. Additionally, this study also investigates the moderating role of the COO effect on the relationships between the perceived importance of preventive measures and brand trust, and between brand trust and intentions to dine out.

2. Literature review

2.1. COVID-19 and preventive measures at restaurants

COVID-19 is the abbreviation of the disease caused by the novel coronavirus, which was first identified in Wuhan, China in 2019 and continued to spread all over the world. According to the COVID-19 Map from Johns Hopkins Coronavirus Resource Center (2020), up to December 2, 2020, there have been more than 64 million confirmed COVID-19 cases worldwide, resulting in more than 1.5 million deaths. Scientists have confirmed that, similar to other respiratory viruses, the primary spread of COVID-19 occurs through human interaction, especially close contact, such as face-to-face conversation (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention CDC, 2020a). Therefore, to slow down the spread of COVID-19, many countries throughout the world, including several states in the U.S., have issued stay-at-home orders and advised residents to avoid nonessential contact since March 2020 (Nussbaumer-Streit et al., 2020). COVID-19 has already deeply affected the global economy, especially the F&B industry, which has suffered significant losses in revenue and jobs caused by the shutdown (Dube et al., 2020). Statistics from the National Restaurant Association (2020a) have indicated that up until April, revenue for restaurants in the U.S. had decreased by as much as 57 %, whereas the revenue for dine-in restaurants decreased by more than 80 %, and that of bars decreased by 86 % compared to the same period last year. It has been reported that infection risk is the main concern that prevents customers from dining at restaurants (Toy and Hernandez, 2020). The U.S. restaurant industry is projected to lose more than $240 billion by the end of 2020 (National Restaurant Association, 2020a).

Whitehouse suggested States reopening their economies by at least a three-phased approach until activities resume unrestricted, such as staffing and gathering (Whitehouse, 2020). Therefore, the period before unrestricted activities resumed was regarded as reopening, which was defined as the reopening period in the present study. Up until early August 2020, most states in the U.S. had begun to relax their stay-at-home-orders after a slow downward trend of COVID-19 cases was observed (Lee et al., 2020). In many regions, restaurants have been allowed to reopen with preventive measures in place (The New York Times, 2020). The CDC and the NRA have issued COVID-19 prevention guidelines to assist restaurants in reopening safely. These guidelines include preventive measures in four areas: food safety, cleaning and sanitizing, employee health and hygiene, and social distancing. Additionally, the CDC has divided restaurants into four risk levels based on the level of interaction with the customers. For instance, drive-through and delivery services are regarded as the lowest risk, and restaurants without a six-foot social distancing layout will be considered as the highest risk (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention CDC, 2020b).

2.2. Perceived importance of preventive measures and intentions to dine out

Compared to carry-out and delivery services, dining in at a restaurant seems to bring a higher risk of COVID-19 infection given that the coronavirus can spread through respiratory droplets when individuals communicate face-to-face (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention CDC, 2020a). However, the reopening of dine-in services was inevitable since restaurants employ more than 13.49 million workers, and dine-in tips are one of the most important sources of income for many of these employees (Statista, 2020). Furthermore, restaurant customers have also indicated that they prefer to dine out among other option (i.e., deliver or carry out) because they can socialize with friends while also being able to watch sporting events on the big screens in bars (Pawan et al., 2014).

As restaurants are preparing to reopen their businesses, the empirical data has shown that Americans have different perceptions of the importance of preventive measures against COVID-19 (Sargent, 2020). A similar phenomenon was previously investigated by Godycki-Cwirko et al. (2017). The results from Godycki-Cwirko et al.’s study (2017) indicated that different individuals would have different perceptions of the importance of preventive measures during a pandemic, as these practices could lead to changes in their lifestyles. For example, although wearing masks helps to prevent the spread of COVID-19, the debate on mask requirements in public remains controversial (Greenhalgh et al., 2020). Studies specifically investigating customers' perceptions of preventive measures in the restaurant industry and their impact on their behaviors, especially during the reopening period, are lacking. To examine whether customers who strongly believe preventive measures in a restaurant are important have higher levels of intention to dine out, the following hypothesis was proposed:

H1

The perceived importance of preventive measures is positively associated with customers’ intentions to dine at American Chinese restaurants during the reopening period.

2.3. Dining involvement and intentions to dine out

Brennan and Macondo (2000, p.132) have described involvement as “a motivational and goal directed emotional state that determines the personal relevance of a purchase decision to a buyer.” Mitchell (1979, p. 194) defined involvement as an indication of one’s arousal or interest in a stimulus or object resulting from cognitive efforts to make the right choice within a category. Zaichkowsky (1985) recommended three main types of involvement, including product, advertisement, and purchase decision. Product involvement refers to an individual’s personal interest in a product because of self-preference or perceived relevance. Involvement with advertisement pertains to customers making a purchase decision if the advertisement conveys a message that the particular product is relevant or important to them. Involvement with purchase decision is related to the decision-making process, through which customers’ selection decisions occur when the purchases are perceived as relevant and important. However, the selection decision may change based on one’s level of involvement (Zaichkowsky, 1986).

Involvement has been widely studied in hospitality and tourism research, particularly in those areas concerned with customer behaviors (Ha, 2018; Josiam et al., 2015; Kim et al., 2012; Levitt et al., 2019; Robinson and Getz, 2016). Dining involvement studies conducted in restaurant settings have revealed that high involvement customers have placed more emphasis on the dining out experience and were more motivated to put in the cognitive effort to evaluate the various aspects of a restaurant (i.e., sense of wellbeing, menu offerings, food quality, and dining atmosphere) (Kim et al., 2012). In Josiam et al.'s (2015) study, which sought to determine the motivators for dining at casual dining restaurants, it was revealed that level of involvement determined “what aspects of a restaurant the customers were looking for.” For example, high involvement customers were attracted to the hedonic aspects of the restaurants, such as ambience and ease of socialization. Another study conducted by Ha (2018) examined the role of involvement in the intentions to choose familiar or new restaurants among 617 customers. The results of this particular study showed that dining involvement affected customers’ variety-seeking behaviors in restaurant selection.

For this study, dining involvement was defined in the context of the values and interests that a customer feels about food and dining out at the restaurant. Customers who are highly involved are more likely to invest time searching for details and develop more interests in dining in services during the reopening. In the previous literature, it has been assumed that restaurant customers who are more involved would be more likely to consider dining out as important and relevant to them. Because this group of high-involved customers may not have dined out for a period of time due to COVID-19 pandemic, they may be more likely to want to dine out (i.e., purchase intention) when business reopens.

H2

Dining involvement is positively associated with customers’ intentions to dine at American Chinese restaurants during the reopening period.

2.4. Mediating role of brand trust

Brand trust is defined in terms of a customer’s confidence and reliance on a business because of its two intangible attributes: reliability and integrity (Delgado-Ballester and Munuera-Aleman, 2002; Xie et al., 2014). Additionally, Sahin et al. (2011) have stated that brand trust is synonymous with the customers’ perceived values and feelings toward a brand and is a key element in a business relationship. Scholars have agreed that positive brand trust can enhance customers’ purchase intentions (Godfrey, 2005; Herbst et al., 2012). This is because a customer is likely to continue to support a brand for an extended duration if a trusting relationship is established (Riorini and Widayati, 2016). Particularly, Srivastava et al. (2016) has indicated that brand trust entails a strong bond and more robust behavioral intentions in a crisis era if a brand is recognized as reliable. In the hospitality industry, reliability is considered to be an essential factor related to safety, health, and satisfaction (Afzal et al., 2010; Song et al., 2012). The COVID-19 pandemic is a crisis for the hospitality industry. Safety and health have become primary considerations that impact customers’ behavioral decisions due to the risk of being infected in public places. In such circumstances, customers make decisions based on the principle of risk reduction (Lacey et al., 2009). Therefore, it is postulated that customers are more likely to rely on the brand they trust to take appropriate measures that ensure their safety during the reopening period.

Trust refers to customers’ beliefs that the chosen restaurants will act in their interests and will perform with responsibility. Sanchez-Franco (2009) has posited that trust is especially critical when customers face a higher level of uncertainty/perception of risk. Implementing preventive measures (e.g., mask orders and social distancing) during the reopening period can help build a safe dining environment to protect customers’ health. It is reasonable to assume that the positive perception of the importance of preventive measures will enhance customers’ feelings of safety and reduce their perception of risk, thereby leading customers to perceive that a restaurant is reliable and cultivating higher levels of brand trust. The enhanced brand trust will likely further strengthen customers’ intentions to dine out at restaurants that implement preventive measures during the pandemic. Thus, brand trust could mediate the relationship between the perception of the importance of preventive measures and the intention to dine out during the reopening period.

Even though restaurants may not fully perform the preventive measures in their day-to-day operation, the reopening of dine-in service signifies that restaurants are certified and supervised by local health authorities to provide a safe dine-in environment (Andrews, 2021). Therefore, reopening can deliver a positive signal of restaurant performance, such as safety and reliability, to the customers. The current study measured customers’ involvement with dining out at a restaurant. This dining involvement is not limited to the desire for dining out at a restaurant to satisfy the basic needs for food, but to fulfill the need for an exceptional dine-in experience. In this case, Kim et al. (2012) suggested that low-involved customers may be motivated simply by hunger or a convenient location, but highly involved customers may strongly emphasize the dining experiences, such as the sense of health and well-being, as well as exotic atmosphere. Therefore, reopening as a signal of certified safety performance in dining service, may engage high-involved customers more than low-involved customers. In addition, previous studies indicated that the signal of safe dining environment during COVID-19 could transfer to the trust towards the restaurant (Kim et al., 2020a, b). Hence, highly involved customers may develop more trust towards the restaurant compared to low-involved customers based on the signal. This enhanced level of trust will positively affect customers’ purchase intention (Godfrey, 2005; Herbst et al., 2012). Based on the above articulation, the following hypotheses were proposed:

H3

The perceived importance of preventive measures is positively associated with restaurant customers' perceived brand trust.

H4

Dining involvement is positively associated with restaurant customers’ perceived brand trust.

H5a

Brand trust mediates the relationship between the perceived importance of preventive measures and customers’ intention to dine at American Chinese restaurants during the reopening period.

H5b

Brand trust mediates the relationship between dining involvement and customers’ intentions to dine at American Chinese restaurants during the reopening period.

2.5. Moderating role of COO effect

The COO, which is country-of-origin, is the country a product or service originated. (Bruwer and Buller, 2012; Roth and Romeo, 1992). For example, Japanese sake will remind customers of the image of Japan, and French wine will bring to mind the impression of France. Evidence shows that the perceived image of the country-of-origin has a significant influence on purchase decisions, and this impact is known as the COO effect (Johansson et al., 1985; Thakor, 1996; White and Cundiff, 1978). A study conducted by Piron (2000) has indicated that the positive country image of Japan enhanced the purchase intentions of luxury products from Japan. Another study by Amine et al. (2005) suggested that for the same computer brand “Acer,” Taiwan’s positive image made participants believe that those computers made in Taiwan were of a higher quality than those made in China. In addition, Jiménez and San Martín (2010) have reported that COO effect is positively associated with customers’ trust in foreign companies, such that customers may develop trust and perceive the reliability of a company if it has a positive country image, and they may display a lower level of trust in the company if the product is associated with a low country image (Hamzaoui and Merunka, 2006; O’Cass and Grace, 2003). Hence, a positive COO effect could enhance customers’ brand trust and purchase intentions (Alden, 1993; Foroudi et al., 2019; Jiménez and San Martín, 2010; Lin and Chen, 2006; Michaelis et al., 2008)

The present study focuses on the image of China and its COO effect on American Chinese restaurants, as Chinese food has become one of the most popular ethnic cuisines in the U.S. (Chen, 2014) and deliver a strong signal of China to most Americans (Liu, 2009). Because the first coronavirus case was reported in China, in the early stage of the pandemic, customers may have associated China with the COVID-19 pandemic, which caused discrimination towards American Chinese Restaurants. Some customers were reluctant to visit American Chinese restaurants (Pershan, 2020). Statistics showed that interest in Chinese food has declined 20 % amid COVID-19, as compared to Italian and traditional American restaurants (Dixon, 2020). Surveys among Chinese restaurant operators have revealed that, for example, the revenue of Chinese restaurants in New York had decreased by 20 % since the pandemic and as much as 40 %–90 % in Seattle’s Chinatown (Lalley, 2020) due to virus-related fears.

However, as time passes, the confirmed cases are rapidly increasing in Europe and the U.S., while the pandemic in China is under controlled. Consequently, some customers tended to believe China has the ability to better manage COVID-19 than other countries (Bremmer, 2020; Silver, 2020; Strauss, 2020). Since American Chinese restaurants deliver a strong signal of China (Liu, 2009), customers who associate China with a more positive image would be expected to have a more positive perception of American Chinese restaurants’ preventive measures, consider them as more reliable and trustworthy, and would have increased levels of intention to dine out at these restaurants. Therefore, the positive COO effect could moderate the positive relationship between customers’ perceptions of the importance of preventive measures and brand trust in American Chinese restaurants during the reopening period. Similarly, the positive COO effect may play a moderating role on the association between the perceived importance of preventive measures and intentions to dine out at American Chinese restaurants during the crisis. Thus, the following hypotheses were proposed:

H6

Positive COO effect moderates the positive relationship between the perceived importance of preventive measures and brand trust such that the relationship is stronger when positive COO effect is high than when it is low.

H7

Positive COO effect moderates the positive relationship between the perceived importance of preventive measures and the intention to dine at an American Chinese restaurant such that the relationship is stronger when positive COO effect is high than when it is low.

3. Research methods

3.1. Sample and data collection

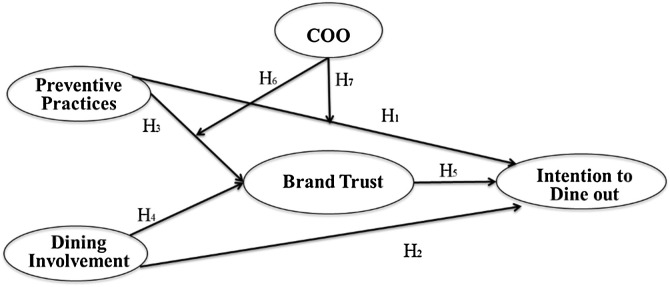

The Institutional Review Board of a university located in the southeastern region of the U.S. approved this study protocol prior to data collection. Since the research model (Fig. 1 ) was proposed based on the circumstances surrounding the COVID-19 pandemic in the U.S. and involved the COO effect of China, the target population of this study was customers from the U.S. who were 18 years of age or older and had dined in at an American Chinese restaurant in the past 12 months. Amazon Mechanical Turk (Mturk), a crowd-sourcing platform where tasks are allocated to a population of unidentified workers in exchange for compensation, was used for data collection in this study. Aside from its efficiency, MTurk is believed to facilitate more diversity and reliability than traditional methods, such as in-person convenience sampling (Berinsky et al., 2017; Shank, 2015).

Fig. 1.

Proposed Research Model and Hypotheses.

The pilot survey was performed among 50 MTurk panelists to verify the clarity of the survey instructions and questions. Some phrasing on the questionnaire was revised based on the comments of the participants in the pilot study. Final data were collected in June 2020 using Qualtrics survey software and distributed by Mturk, with a target sample size of 300. The sample size was estimated using the ratio of sample size to free parameters, which should be between 5:1 and 10:1 (Bentler and Chou, 1987). With 36 free parameters to be estimated, a sample between 180 and 360 was considered adequate.

A self-reported online survey was prepared using Qualtrics. A filter function was applied in the survey to make sure the participants were eligible to participate in this study. The participants were then asked to name an American Chinese restaurant they liked to visit when dining out prior to COVID-19. Bearing this restaurant in mind, participants were then asked to answer a series of questions by order of brand trust, dining involvement, the perceived importance of preventive measures during the reopening period, intention to dine out, and COO effect. Three attention check questions were used to ensure the quality of the data. An example question was, “Please select ‘Strongly Disagree.’” Participants who failed to answer these attention check questions correctly were directed to the end of the survey, and their responses were excluded from the data analysis.

3.2. Measurement scales

Survey items were developed based on previous literature on brand trust, dining involvement, COO effect, and purchase intention. Brand trust was measured with Kabadayi and Lerman's (2011) ten-item scales. Dining involvement was measured by five items adapted from Cho's (2009) study. Preventive measures were developed after reviewing the COVID-19 reopening guidelines published by the NRA and CDC (ServSafe, 2020). Intention to dine out was measured with three items obtained from Kim et al. (2012) study. The COO effect measures were modified from the work of Wang et al. (2012). Demographic information, such as gender, age, education, and household income, was also collected. All study variables were measured using a five-point Likert-type scale, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) Results (N = 296).

| Factor Loadings | Composite Reliability | |

|---|---|---|

| Preventive Measures | .90 | |

| Implement strict handwashing practices that include how and when to wash hands. | .80 | |

| Implement procedures and practices to clean and sanitize surfaces | .76 | |

| Prohibit sick employees in the workplace. | .76 | |

| Take employees’ temperatures at the operators’ discretion. | .54 | |

| Require employees to wear face covering. | .64 | |

| Train all employees on the importance of frequent hand washing, the use of hand sanitizers. | .81 | |

| Thoroughly detail-clean and sanitize entire facility. | .82 | |

| Make hand sanitizer readily available to guests. | .65 | |

| Update floor plans for common dining areas, redesigning seating arrangements to ensure at least six feet of separation between table setups. | .62 | |

| Limit party size at tables.* | – | |

| Use a reservations-only business model or call-ahead seating.* | – | |

| Use technology solutions where possible to reduce person-to-person interaction: mobile ordering and menu tablets; text on arrival for seating; contactless payment options.* | – | |

| Dining Involvement | .75 | |

| I am interested in foods. | .74 | |

| I think that where to eat is very important. | .52 | |

| I am very interested in restaurants. | .70 | |

| I enjoyed eating out. | .66 | |

| Restaurants must show my personality.* | – | |

| Brand Trust | .88 | |

| This restaurant seems to… | ||

| have sound principles that guide its behavior. | .60 | |

| keep its commitments. | .65 | |

| very capable of serving its customers. | .72 | |

| have necessary knowledge and recourses to fulfill its customers’ needs. | .63 | |

| confident about this restaurant skill to serve its customers. | .79 | |

| competent in preparing food. | .72 | |

| performs its role of cooking food very well. | .70 | |

| concerned about its customers’ health and safety. | .56 | |

| would not do anything to hurt customers. | .54 | |

| interested in its customers’ wellbeing, not just its own profit. | .54 | |

| COO Effect | ||

| In your opinion, China is/has… | .90 | |

| Affluent | .55 | |

| Economic well developed* | – | |

| High living standards | .62 | |

| Good standard of life | .70 | |

| Peace loving | .81 | |

| Friendly toward us | .86 | |

| Cooperative with us | .85 | |

| Likable | .82 | |

| Intention to Dine out | .85 | |

| I would dine out at this restaurant in the future. | .69 | |

| I would recommend this restaurant to my friends and others. | .84 | |

| I would spread positive word-of-mouth about this restaurant. | .88 |

χ2(478) = 936.48, p<.01; CFI: .91; RMSEA: .06; SRMR: .06.

Dropped items.

3.3. Data analysis

SPSS 24.0 was used for data cleaning and data analysis. Descriptive analysis (e.g., frequency, percentages, mean, and standard deviation) was performed first. Measurement reliability and validity were examined using confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) with maximum likelihood estimation. Podsakoff and Organ's (1986) procedure was followed to examine common method bias with CFA. Structural model was estimated using maximum likelihood through SPSS Amos 23.0 to examine Hypotheses 1–4. PROCESS v3.3 macro model 4 was used to test the mediating hypothesis. Hierarchical multiple regression was employed to examine the moderating hypotheses.

4. Results

Of the 355 responses collected, 59 were excluded from the data analysis due to incomplete data. The remaining 296 complete responses were further analyzed. Around 75 % of the participants were between 26–55 years of age, representing the part of the general U.S. population who spends more on food away from home (Oches, 2012). Participants were located in 44 states within the U.S. with California (n = 39, 13.2 %), Texas (n = 32, 10.8 %), and New York (n = 22, 7.4 %) being the top three states. Most participants indicated that they liked to visit casual dining American Chinese restaurants (n = 146, 49.3 %) before the COVID-19 pandemic. Close to 65 % (n = 192) of the American Chinese restaurants they named were chain restaurants. The most frequently mentioned restaurant brands were Panda Express (n = 128), PF Chang’s (n = 44), and Pei Wei (n = 19). Approximately 68 % (n = 199) of the participants had visited the named American Chinese restaurants frequently before the pandemic, ranging from sometimes (n = 162, 54.7 %) to often (n = 37, 12.5 %). About 65 % (n = 188) of the participants indicated that they would visit the restaurant once it reopened, with 48.6 % (n = 144) of them indicated “sometimes” and another 14.9 % (n = 44) selected “often”. A paired sample t-test indicated a significantly lower level of visit frequency after the restaurant reopened (2.69 ± .91) compared to before the COVID-19 pandemic (2.79 ± .82, p < .05). Table 1 displays the detailed demographic information of the respondents.

Table 1.

Demographics of the Research Participants (N = 296).

| Frequency | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 152 | 51.4 |

| Female | 143 | 48.3 |

| Prefer not to respond | 1 | .3 |

| Age | ||

| 18–25 | 36 | 12.2 |

| 26–35 | 116 | 39.2 |

| 36–45 | 71 | 23.9 |

| 46–55 | 37 | 12.5 |

| ≥56 | 36 | 12.2 |

| Ethnicity | ||

| White | 213 | 72.0 |

| Black or African American | 20 | 6.8 |

| Hispanic | 16 | 5.4 |

| Asian | 35 | 11.8 |

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 6 | 2.0 |

| Other | 6 | 2.0 |

| Education | ||

| High school or less | 21 | 7.1 |

| Some college | 34 | 11.5 |

| Associate’s degree | 22 | 7.4 |

| Bachelor’s degree | 143 | 48.3 |

| Graduate degree | 61 | 20.6 |

| Professional degree | 13 | 4.4 |

| Prefer not to respond | 2 | .7 |

| Household income | ||

| Less than $20,000 | 28 | 9.5 |

| $20,000–$39,999 | 53 | 17.9 |

| $40,000–$59,999 | 61 | 20.6 |

| $60,000–$79,999 | 37 | 12.5 |

| $80,000–$99,999 | 52 | 17.6 |

| $100,000 and above | 56 | 18.9 |

| Prefer not to respond | 9 | 3.0 |

4.1. Measurement model

Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was conducted using the maximum likelihood estimation to examine the measurement model fit. Based on the CFA, one item of the dining involvement section (“Restaurants must show my personality” (0.27)), three items of the preventive measures section (“Limit party size at tables” (0.39), “Use a reservations-only business model or call-ahead seating” (.25), and “Use technology solutions where possible to reduce person-to-person interaction, including mobile ordering and menu tablets; text on arrival for seating; and contactless payment options” (.48)), and one item of the COO effect section (“China is economically well developed” (.47)) were removed from the final analysis due to the low standardized item loading values.

CFA was again conducted after removing items with low loading values. Table 2, Table 3 show the standardized factor loadings and fit statistics, which demonstrate a good fit between the data and the theoretical model (χ2 (478) = 936.48, p < 0.01; comparative fit index (CFI) = .91; root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) = .06; standardized root mean square residual (SRMR) = .06).

Table 3.

Means, standard deviations, and correlation coefficients among performance appraisal aspects and psychological contract (N = 296).

| Measures | Mean | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | AVE | The square root of AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Dining involvement | 4.11 | .60 | 1 | .44 | .66 | ||||

| 2. Brand trust | 3.99 | .51 | .46** | 1 | .42 | .65 | |||

| 3. Preventive measures | 4.36 | .62 | .36** | .37** | 1 | .52 | .72 | ||

| 4. Country-of-origin | 3.23 | .82 | .14* | .22* | −.02 | .57 | .75 | ||

| 5. Intention to dine out | 4.03 | .70 | .41** | .58** | .22** | .12* | 1 | .65 | .81 |

| Cronbach’s Alpha | – | – | .75 | .88 | .90 | .91 | .84 |

Note.

Correlation is significant at the 0.05 level (2-tailed).

Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed).

Composite reliability (CR) and Cronbach’s alpha of the constructs were used to measure the internal consistency of the latent variables. Cronbach’s alpha values ranged from 0.75 to 0.91, and CR ranged from 0.75 to 0.90, showing good internal consistency. Convergent validity was examined using factor loadings and each construct’s t-value to check whether factor loadings was statistically significant (Bagozzi and Yi, 1988). As indicated in Table 2, all factor loadings were significant at 0.05. A comparison of the squared pair-wise correlations between constructs and the average variance extracted (AVE) value for each construct was performed to assess the discriminant validity (Fornell and Larcker, 1981), and the results indicated that each construct’s correlations with the other constructs were lower than its square root of the AVE value (between 0.42 and 0.65) (Table 3). Though 0.50 is the cutoff for AVE, a value of 0.40 is considered acceptable if the CR value is higher than 0.60 (Fornell and Larcker, 1981; Hair et al., 2010). Hence, both convergent validity and discriminant validity were achieved.

Podsakoff et al.'s (2012) single-method-factor test was conducted to test the common method variance. The results indicated that the five-factor model was significantly better (χ2 = 936.48; CFI = .91; RMSEA = .06) than the one-factor model (χ2 = 3072.47; CFI = .49; RMSEA = .13; Δχ2 = 2135.99, p < .01). Hence, common method bias was not a concern in this study.

4.2. Test of hypotheses

A structural model was estimated using maximum likelihood through SPSS Amos 23.0. Table 4 shows the theoretical paths linking dining involvement, the perceived importance of preventive measures, brand trust, and intention to dine out. The results demonstrated that the overall fit of the structural model was adequate (χ2 = 803.739, df = 287, p < .05; CFI = .93; RMSEA = .06; χ2/df = 2.80).

Table 4.

Structural Model Results (N = 296).

| Path | Coefficients | P | 95 % C.I. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | Preventive practice→ Intention to dine out | .04 | .94 | [−.11, .12] |

| H2 | Dining involvement → Intention to dine out | .14 | * | [.06,.23] |

| H3 | Preventive practice → Brand trust | .20 | ** | [.22,.40] |

| H4 | Dining involvement → Brand trust | .46 | ** | [.35,.48] |

| H5a | Preventive practice → Brand trust→ Intention to dine out | .24 | [.16, .33] | |

| H5b | Dining involvement → Brand trust→ Intention to dine out | .26 | [.18,.36] |

χ2 = 803.73, df = 287, p < .05; CFI = .93; RMSEA = .06; χ2/df = 2.80.

p < .01.

p < .05.

The results further indicated that the perceived importance of preventive measures had a significantly positive association with brand trust (.20, p < .01), lending support to Hypothesis 3. However, the perceived importance of preventive measures was not significantly associated with customers’ intentions to dine out at American Chinese restaurants (.04, p = .94). Hence, Hypotheses 1 and 7 were not supported. The results also revealed that dining involvement had a significantly positive relationship with the intention to dine out (.14, p < .05) and brand trust (.46, p < .01). Therefore, Hypotheses 2 and 4 were supported.

PROCESS macro-Model 4 (Hayes, 2013) was used to test the mediation hypothesis. Bootstrapping was performed with a sample size of 2,000 and a 95 % confidence interval (CI) for the mediation effect (Hayes, 2009). Brand trust had a significantly positive relationship with the intention to dine out (.69, p < .01). The significance of the indirect effect is assessed by whether the CIs include zero (Preacher and Hayes, 2008). The results of the analysis showed that the indirect effect of the perceived importance of preventive measures on the intention to dine out via brand trust was significant (.24, CI [.16, .33]). Hence, the effect of the perceived importance of preventive measures on customers’ intentions to dine out was fully mediated by brand trust, supporting Hypothesis 5a. Similarly, the results showed that the indirect effect of dining involvement on the intention to dine out via brand trust was significant (.26, CI [.18, .36]). Brand trust partially mediated the relationship between dining involvement and the intention to dine out, supporting Hypothesis 5b.

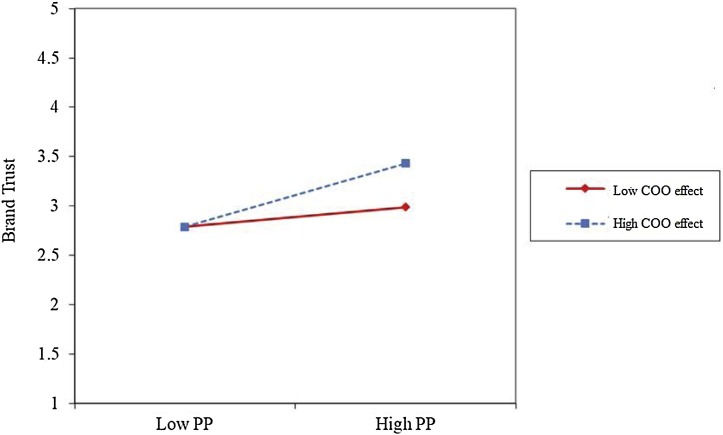

Hierarchical multiple regression analyses were used to examine Hypothesis 6. Preventive measures (PM) and COO effect were standardized before multiplication to create the interaction term. PM and COO effect were entered in Step 1 and the interaction term (PM X COO effect) in Step 2 to predict brand trust. According to Table 5 , the interaction of PM and COO effect was significant for brand trust (β = .11, p<.01). Further, the interaction accounted for the significant incremental variance of perceived brand trust (ΔR2 = .04, p<.01).

Table 5.

Moderation test results (N = 296).

| Independent Variables | Brand Trust |

|---|---|

| Step 1 | |

| Preventive practice (PP) | .19** |

| Country-of-origin (COO effect) | .12** |

| R2 | .19** |

| Step 2 | |

| Preventive practice | .21** |

| Country-of-origin | .11** |

| PP × COO effect | .11** |

| ΔR2 | .04** |

| F | 49.79 |

| Total R2 | .23** |

Notes: **. p<.01. *. p<.05.

The brand trust score was plotted at a combination of the mean ± 1 standard deviation (high and low levels) for both the perceived importance of preventive measures and COO effect to understand the nature of the interaction effects. Fig. 2 shows that the effect of the perceived importance of preventive measures on customers’ perceived brand trust was positive for customers with both a high level of positive COO effect (simple slope = .32, p<.01) and a low level of positive COO effect (simple slope = .21, p<.01). The positive relationship between the perceived importance of preventive measures and brand trust was enhanced for customers with a high level of positive COO effect when compared to those with a low level of positive COO effect, supporting Hypothesis 6.

Fig. 2.

Moderating effect of COO effect.

5. Discussion

This study examined the relationship between customers’ perceived importance of preventive measures, dining involvement, brand trust, and intentions to dine at American Chinese restaurants during the reopening period, as well as the moderating role of COO effect on the relationships between the perceived importance of preventive measures and brand trust, and between brand trust and intentions to dine out. The results showed that participants’ dining frequency at American Chinese restaurants has significantly decreased during the reopening period compared to before the pandemic. This was supported by the fact that, with 50 states reopened in early June, restaurant sales were reported to be only 70 % of those in February (National Restaurant Association, 2020b). The results suggested that brand trust fully mediated the relationship between the perceived importance of preventive measures and customers’ intentions to dine out, where the perceived importance of preventive measures indirectly impacted customers’ intentions to dine out at American Chinese restaurants during the reopening period via brand trust. This echoed findings from studies before pandemic that dining environment could affect customers' decision-making (Horng et al., 2013; Ryu and Jang, 2008), as well as the brand trust (Hwang and Ok, 2013). During the pandemic, customers’ positive perception of the importance of preventive measures implemented by American Chinese restaurants may have reduced the perceived risk of dining out, resulting in an increased level of brand trust. The improved brand trust may have further enhanced the customers’ intentions to dine out at restaurants during the reopening period. This finding is consistent with a recent study by Taylor (2020) that the dining environmental setup would affect customers’ perception of the restaurant's safety, which determines the customer's decision-making during the reopening period. Thus, the findings of this study that highlight the critical role of brand trust were consistent with previous research indicating that brand trust can positively influence customers’ purchase intentions (Godfrey, 2005; Herbst et al., 2012; Srivastava et al., 2016).

Moreover, customers’ dining involvement was found to have both a direct effect on the intentions to dine out at American Chinese restaurants during the reopening period and an indirect effect via brand trust. The direct relationship between dining involvement and intentions to dine out was supported by previous research showing that customers’ levels of dining involvement played an important role in their purchase behaviors, such as purchase frequency and willingness to purchase (Campbell et al., 2014; Prebensen et al., 2013). Hence, a higher level of dining involvement was associated with a higher level of intentions to dine at American Chinese restaurants even during the reopening period. Additionally, dining involvement positively enhanced the perceived brand trust, which was aligned with the findings from previous research (Martín et al., 2011; Rifon et al., 2005; Sanchez-Franco, 2009). High involvement in certain types of products or service could lead to a high level of customer trust as the service/product delivers a particular signal the customers are interested in (Martín et al., 2011; Rifon et al., 2005; Sanchez-Franco, 2009). Highly involved customers who value dining out at restaurants may be more confident in restaurants’ reliability and safety during the reopening period, which may lead to a higher level of brand trust, which can transform into the intentions to dine out during the pandemic. These findings are consistent with previous risk management studies (Godfrey, 2005; Herbst et al., 2012; Srivastava et al., 2016).

COO effect moderated the relationship between the perceived importance of preventive measures and brand trust, such that the positive relationship was strengthened for customers with a more positive perception of China than for those who had a more negative perception. This might have been because customers who held a positive perception of China as a country tended to perceive American Chinese restaurants as strictly following the recommended preventive measures during the COVID-19 outbreak, and their positive perception of the country would have enhanced their brand trust. This is consistent with the previous findings indicating that a positive perception of COO effect has a positive impact on customers’ trust in foreign companies, while the less positive perception of COO effect may lead to a lower level of trust in a company (Hamzaoui and Merunka, 2006; Jiménez and San Martín, 2010).

6. Conclusion and implications

6.1. Conclusion

Increasing customers’ intentions to dine out during the reopening period will be a challenge for the F&B industry. This current study contributes to the body of literature on this subject by introducing a novel model that examines how brand trust, the perceived importance of preventive measures, and dining involvement affect customers’ dining out intention. In addition, this study sought to confirm the role of COO effect in enhancing customers’ intentions to dine out during the pandemic. Overall, the results of this study showed that chain restaurants, such as Panda Express and PF Chang’s, remained the most frequently visited American Chinese restaurants, and the COVID-19 pandemic negative affected the frequency of visits to American Chinese restaurants. Customer dining involvement was found to have a direct positive effect on intentions to dine out during the reopening period. In addition, both dining involvement and the perceived importance of preventive measures may have indirectly increased customers’ intentions to dine out at American Chinese restaurants via brand trust. The positive relationship between the perceived importance of preventive measures and brand trust, and between brand trust and intentions to dine out, both were strengthened for customers with a higher level of positive COO effect than a lower level of positive COO effect.

6.2. Theoretical and practical implications

Theoretically, this research has three main contributions. First, no other study has examined how the perceived importance of preventive measures has affected customers’ behavior in the restaurant industry during the pandemic. This study examined the customers’ perceptions of the new restaurant reopening guidelines published by the NRA and CDC. Therefore, this study addresses this emerging issue in the literature by confirming that the perceived importance of preventive measures could serve as an antecedent for customers’ intentions to dine out. Second, the study confirmed the indirect effect of both the perceived importance of preventive measures and dining involvement on the intention to dine out via brand trust during the reopening period. Previous studies have indicated that brand trust serves as a mediator of purchase intentions in many settings. For example, Martín-Consuegra et al. (2018) indicated that the trustworthiness of a brand could act as a mediator between brand credibility and purchase intentions in the fashion industry. In the hospitality setting, Chen and Chang (2013) suggested that green trust in a brand mediates the relationship between perceived risk and customers’ green purchase intention. This study further supported that brand trust mediates the relationship between dining involvement, the perceived importance of preventive measures, and intentions to dine out. Third, though many studies have suggested that country images may either moderate or directly enhance brand trust and purchase intentions (Alden, 1993; Foroudi et al., 2019; Lin and Chen, 2006; Michaelis et al., 2008; Wang et al., 2012), limited studies have investigated the COO effect on customers’ selection of restaurants or cuisines that deliver a signal of a specific country, such as Chinese food and Chinese restaurants. This study confirmed that the positive COO effect could strengthen the positive relationship between the perceived importance of preventive measures and brand trust.

This study also has several practical implications for the F&B industry, particularly for American Chinese restaurants. Some restaurants and bars have implemented preventive measures as recommended by the CDC and NRA, but many have not fully complied with the guidelines and have not required their customers to do so at the restaurants (Lin et al., 2020). Though some of these preventive measures have appeared to cause economic hardship for the restaurants as fewer customers can be served at one time, following preventive measures during the reopening period should not be debatable (Los Angeles Times, 2020). In fact, these preventive measures may drive incremental revenue by making a restaurant a safe spot for customers (DeFranco, 2020). The results of this study support the argument that restaurants should follow preventive measures in order to build brand trust, which will drive customers’ intentions to dine out. From a marketing perspective, restaurants may elect to advertise the preventive measures that are being implemented on their premises and how they are committed to protecting the safety and health of the employees and customers during the pandemic via various channels, such as on their websites and social media outlets, to encourage customers to dine out at their restaurants. Furthermore, certain preventive measures, such as strict handwashing practices, cleaning and sanitizing facilities, and training employees about handwashing and appropriate sanitation, may be more valued by the customers than the other preventive measures.

The findings of this study also revealed that building strong brand trust is important to increase customers’ dining out intentions. To build brand trust, a restaurant could demonstrate its ability to serve its customers by providing quality food and good customer service. Furthermore, restaurants could also build the confidence of their customers in dining out with them during this pandemic by emphasizing their commitment to customers’ health and safety. Their commitment could be advertised, for example, through the restaurant’s mission statement on the landing page of its website.

Regarding dining involvement as another factor associated with the intention to dine out, the findings of this study revealed that individuals who showed interest and valued food and dining out demonstrated higher intentions to dine out. It is recommended that restauranteurs understand their customers, identify those that may be highly involved, and investigate what specific attributes of food or dining experiences they may find attractive and attempt to “sell” to these customers (Bruwer et al., 2019). In addition, restaurant selection is important for customers who are involved, and they may carefully review and look for information related to restaurants (Ha, 2018). Therefore, restaurants should include well-selected information that highlight their niche to attract these customers. Moreover, for American Chinese restaurant operators, it may be worthwhile to showcase how they are related to China and their origins so that customers who have a favorable image of this country may choose to dine out at their restaurants.

6.3. Limitations and future research recommendations

This study has several limitations and opens avenues for future studies. First, the participants of this study were recruited through a market research company, MTurk, and thus the sample only included the survey panelists that existed in its database. Therefore, the results may not be representative of all the customers who patronize American Chinese restaurants and should be interpreted with caution. Besides, Memory and recall are believed to cause certain bias in self-report marketing studies (Sedgwick, 2012). Future studies may recruit participants via collaboration with restaurants to gather data on customers’ perceptions and opinions in a real-time setting. Second, this study specifically targeted customers of casual, American Chinese restaurants, and the results may not be generalizable to other kinds of restaurants (e.g., non-American Chinese, fast, or fine dining restaurants). Future studies may expand the scope by incorporating various restaurant types, which would allow for multi-group comparison analysis to further examine how the constructs, differ based on the types of restaurants. In addition, this study investigated the future intentions to dine out at American Chinese restaurants, which may not translate into actual behaviors. Even though previous studies have argued that behavioral intention is a proxy for actual behavior (Sheeran et al., 2002; Webb and Sheeran, 2006), it is not guaranteed that such a relationship applies in the case of the present study. In addition, Finally, this study investigated four factors that could affect customers’ dining intentions. Because variables such as previous experiences, perceived food and service quality, perceived risks, as well as positive dining experience during reopening period could also affect customers’ purchase behaviors (Namkung and Jang, 2007; Han and Ryu, 2009; Tsiros and Heilman, 2005), future studies may expand the scope of the present study by incorporating these variables.

References

- Afzal H., Khan M.A., ur Rehman K., Ali I., Wajahat S. Customer’s trust in the brand: can it be built through brand reputation, brand competence and brand predictability. Int. Bus. Res. 2010;3(1):43–51. [Google Scholar]

- Alden D.L. Product trial and country-of-origin: an analysis of perceived risk effects. J. Int. Consum. Mark. 1993;6(1):7–26. [Google Scholar]

- Amine L.S., Chao M.C., Arnold M.J. Executive insights: exploring the practical effects of country of origin, animosity, and price–quality issues: two case studies of Taiwan and Acer in China. J. Int. Mark. 2005;13(2):114–150. [Google Scholar]

- Andrews C. USA Today; 2021. Mask Mandates, Limited Capacity: These Are Each State’s Reopening Restaurant Restrictions.https://www.usatoday.com/story/money/2021/01/02/restaurant-reopening-restrictions-in-every-state/43303369/ Jan 1. [Google Scholar]

- Bagozzi R.P., Yi Y. On the evaluation of structural equation models. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 1988;16(1):74–94. [Google Scholar]

- Bentler P.M., Chou C.P. Practical issues in structural modeling. Sociol. Methods Res. 1987;16(1):78–117. [Google Scholar]

- Berinsky A.J., Huber G.A., Lenz G.S. Evaluating online labor markets for experimental research: Amazon.com’s Mechanical Turk. Political Anal. 2017;20(3):351–368. [Google Scholar]

- Bilkey W.J., Nes E. Country-of-origin effects on product evaluations. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 1982;13(1):89–100. [Google Scholar]

- Bremmer I. Time; 2020. Despite a Strong COVID-19 Rebound, China Isn’t Going Back to Normal Anytime Soon.https://time.com/5897883/china-coronavirus-recovery October 8. [Google Scholar]

- Brennan L., Mavondo F. November). Involvement: an unfinished story?. Paper Presented at the Australian and New Zealand Marketing Academy Conference; Gold Coast Old, Australia; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Bruwer J., Buller C. Country‐of‐origin (COO) brand preferences and associated knowledge levels of Japanese wine customers. J. Prod. Brand. Manag. 2012;21(5):307–316. [Google Scholar]

- Bruwer J., Cohen J., Kelley K. Wine involvement interaction with dining group dynamics, group composition and consumption behavioral aspects in USA restaurants. Int. J. Wine Bus. Res. 2019;31(1):12–28. [Google Scholar]

- Budhwani H., Sun R. Creating COVID-19 stigma by referencing the novel coronavirus as the “Chinese virus” on twitter: quantitative analysis of social media data. J. Med. Internet Res. 2020;22(5) doi: 10.2196/19301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bureau of Labor Statistics [BLS] 2020. Frequently Asked Questions: the Impact of the Coronavirus (COVID-19) Pandemic on the Employment Situation for April 2020.https://www.bls.gov/cps/employment-situation-covid19-faq-april-2020.pdf May 8. [Google Scholar]

- Burki T. China’s successful control of COVID-19. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2020;20(11):1240–1241. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30800-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell J., DiPietro R.B., Remar D. Local foods in a university setting: price consciousness, product involvement, price/quality inference and customer’s willingness-to-pay. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2014;42:39–49. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC] 2020. Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19)–Prevention & Treatment.https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/prevent-getting-sick/prevention.html Oct 28. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC] 2020. Considerations for Restaurants and Bars.https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/community/organizations/business-employers/bars-restaurants.html Oct 29. [Google Scholar]

- Cha J., Borchgrevink C.P. Customers’ perceptions in value and food safety on customer satisfaction and loyalty in restaurant environments: moderating roles of gender and restaurant types. J. Qual. Assur. Hosp. Tour. 2019;20(2):143–161. [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y. Columbia University Press; 2014. Chop Suey, USA: The Story of Chinese Food in America. [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y.S., Chang C.H. Greenwash and green trust: the mediation effects of green customer confusion and green perceived risk. J. Bus. Ethics. 2013;114(3):489–500. [Google Scholar]

- Cho W.J. A study on interaction of cause and effect among personal involvement, satisfaction, trust, switching cost and loyalty regarding casual dining restaurant. J. Korean Soc. Food Cult. 2009;24(5):496–505. [Google Scholar]

- DeFranco L. 2020. How Restaurants Can Minimize the Impact of COVID-19.https://sevenrooms.com/en/blog/restaurants-minimize-covid-19/ March 13. [Google Scholar]

- Delgado-Ballester E., Munuera-Aleman J.L. Development and validation of a brand trust scale across product categories: a confirmatory and multigroup invariance analysis. American Marketing Association Conference Proceedings. 2002;13 519. [Google Scholar]

- Dixon V. 2020. By the Numbers: COVID-19’s Devastating Effect on the Restaurant Industry.https://www.eater.com/2020/3/24/21184301/restaurant-industry-data-impact-covid-19-coronavirus March 24. [Google Scholar]

- Dube K., Nhamo G., Chikodzi D. COVID-19 cripples global restaurant and hospitality industry. Curr. Issues Tour. 2020:1–4. doi: 10.1080/13683500.2020.1773416. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fornell C., Larcker D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981;18(1):39–50. [Google Scholar]

- Foroudi P., Cuomo M.T., Rossi M., Festa G. Country-of-origin effect and millennials’ wine preferences–a comparative experiment. Br. Food J. 2019;122(8):2425–2441. [Google Scholar]

- Godfrey P.C. The relationship between corporate philanthropy and shareholder wealth: a risk management perspective. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2005;30(4):777–798. [Google Scholar]

- Godycki-Cwirko M., Panasiuk L., Brotons C., Bulc M., Zakowska I. Perception of preventive care and readiness for lifestyle change in rural and urban patients in Poland: a questionnaire study. Ann. Agric. Environ. Med. 2017;24(4):732–738. doi: 10.26444/aaem/81393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenhalgh T., Schmid M.B., Czypionka T., Bassler D., Gruer L. Face masks for the public during the covid-19 crisis. BMJ. 2020;369:m1435. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ha J. Why do people try different restaurants? The investigation of personality, involvement, and customer satisfaction. Int. J. Hosp. Tour. Adm. 2018:1–15. doi: 10.1080/15256480.2018.1511498. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hair J.F., Anderson R.E., Babin B.J., Black W.C. Vol. 7. 2010. (Multivariate Data Analysis: A Global Perspective). Pearson Upper Saddle River. [Google Scholar]

- Haischer M.H., Beilfuss R., Hart M.R., Opielinski L., Wrucke D., Zirgaitis G., et al. Who is wearing a mask? Gender-, age-, and location-related differences during the COVID-19 pandemic. PLoS One. 2020;15(10) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0240785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamzaoui L., Merunka D. The impact of country of design and country of manufacture on customer perceptions of bi‐national products’ quality: an empirical model based on the concept of fit. J. Consum. Mark. 2006;23(3):145–155. [Google Scholar]

- Han H., Ryu K. The roles of the physical environment, price perception, and customer satisfaction in determining customer loyalty in the restaurant industry. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2009;33(4):487–510. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes A.F. Beyond Baron and Kenny: statistical mediation analysis in the new millennium. Commun. Monogr. 2009;76(4):408–420. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes A.F. Google Scholar; 2013. PROCESS SPSS Macro [Computer Software and Manual] pp. 59–71. [Google Scholar]

- Herbst K.C., Finkel E.J., Allan D., Fitzsimons G.M. On the dangers of pulling a fast one: advertisement disclaimer speed, brand trust, and purchase intention. J. Consum Res. 2012;38(5):909–919. [Google Scholar]

- Horng J.S., Chou S.F., Liu C.H., Tsai C.Y. Creativity, aesthetics and eco-friendliness: a physical dining environment design synthetic assessment model of innovative restaurants. Tour. Manag. 2013;36:15–25. [Google Scholar]

- Hwang J., Ok C. The antecedents and consequence of consumer attitudes toward restaurant brands: a comparative study between casual and fine dining restaurants. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2013;32:121–131. [Google Scholar]

- Jiménez N.H., San Martín S. The role of country-of-origin, ethnocentrism and animosity in promoting customer trust. The moderating role of familiarity. Int. Bus. Rev. 2010;19(1):34–45. [Google Scholar]

- Johansson J.K., Douglas S.P., Nonaka I. Assessing the impact of country of origin on product evaluations: a new methodological perspective. J. Mark. Res. 1985;22(4):388–396. [Google Scholar]

- Johns Hopkins Coronavirus Resource Center . 2020. COVID-19 Map - Johns Hopkins Coronavirus Resource Center.https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/map.html November 20. [Google Scholar]

- Josiam B.M., Kalldin A.C., Duncan J.L. Using the involvement construct to understand the motivations of customers of casual dining restaurants in the USA. Hospitality Review. 2015;31(4):9. [Google Scholar]

- Kabadayi S., Lerman D. Made in China but sold at FAO Schwarz: country‐of‐origin effect and trusting beliefs. Int. Mark. Rev. 2011;23(3):102–126. [Google Scholar]

- Kim I., Jeon S.M., Hyun S.S. Chain restaurant patrons’ well‐being perception and dining intentions. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manage. 2012;24(3):402–429. [Google Scholar]

- Kim J., Kim J., Lee S.K., Tang L.R. Effects of epidemic disease outbreaks on financial performance of restaurants: event study method approach. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2020;43:32–41. [Google Scholar]

- Kim J., Kim J., Wang Y. Uncertainty risks and strategic reaction of restaurant firms amid COVID-19: evidence from China. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2020;92 doi: 10.1016/j.ijhm.2020.102752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lacey S., Bruwer J., Li E. The role of perceived risk in wine purchase decisions in restaurants. Int. J. Wine Bus. Res. 2009;21(2) 1751-1062. [Google Scholar]

- Lalley H. Restaurant Business; 2020. Data: Chinese Restaurants Hit Hard by Coronavirus Fears.https://www.restaurantbusinessonline.com/operations/data-chinese-restaurants-hit-hard-coronavirus-fears March 12. [Google Scholar]

- Lantry L., Pereira I., Torres E. ABC News; 2020. What’s Your State’s Coronavirus Reopening Plan?https://abcnews.go.com/Business/states-coronavirus-reopening-plan/story?id=70565409 May 27. [Google Scholar]

- Lee J., Mervosh S., Avila Y., Harvey B., Matthews A. The New York Times; 2020. See How All 50 States Are Reopening (and Closing Again)https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2020/us/states-reopen-map-coronavirus.html August 19. [Google Scholar]

- Levitt J.A., Zhang P., DiPietro R.B., Meng F. Food tourist segmentation: attitude, behavioral intentions and travel planning behavior based on food involvement and motivation. Int. J. Hosp. Tour. Adm. 2019;20(2):129–155. [Google Scholar]

- Lin L.Y., Chen C.S. The influence of the country‐of‐origin image, product knowledge and product involvement on customer purchase decisions: an empirical study of insurance and catering services in Taiwan. J. Consum. Mark. 2006;23(5):248–265. [Google Scholar]

- Lin R.G., Lee I., Green S. Los Angeles Times; 2020. Bars, Indoor Dining Could Remain Closed for the Foreseeable Future Amid Coronavirus Surge.https://www.latimes.com/california/story/2020-07-09/coronavirus-bars-indoor-dining-closed-future July 9. [Google Scholar]

- Liu H. Chop Suey as imagined authentic Chinese food: the culinary identity of Chinese restaurants in the United States. J. Transnatl. Am. Stud. 2009;1(1) [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y., Jang S.S. Perceptions of Chinese restaurants in the US: what affects customer satisfaction and behavioral intentions? Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2009;28(3):338–348. [Google Scholar]

- Los Angeles Times . Los Angeles Times; 2020. Letters to the Editor: There Is No Gray Area on Masks. If You Don’t Wear One, You Deserve to Be Fined.https://www.latimes.com/opinion/story/2020-05-24/no-gray-area-on-masks-if-you-dont-wear-one-you-deserve-to-be-fined May 21. [Google Scholar]

- Lucas A. CNBC; 2020. No Swiping Fries, Ditch the Reusable Cup. Restaurants’ Coronavirus Measures Go Beyond Extra Elbow Grease.https://www.cnbc.com/2020/03/06/us-restaurants-respond-to-coronavirus-with-more-cleaning-and-creativity.html March 6. [Google Scholar]

- Maheswaran D. Country of origin as a stereotype: effects of customer expertise and attribute strength on product evaluations. J. Consum. Res. 1994;21(2):354–365. [Google Scholar]

- Martín S.S., Camarero C., José R.S. Does involvement matter in online shopping satisfaction and trust? Psychol. Mark. 2011;28(2):145–167. [Google Scholar]

- Martín-Consuegra D., Faraoni M., Díaz E., Ranfagni S. Exploring relationships among brand credibility, purchase intention and social media for fashion brands: a conditional mediation model. J. Glob. Fash. Mark. 2018;9(3):237–251. [Google Scholar]

- Michaelis M., Woisetschläger D.M., Backhaus C., Ahlert D. The effects of country of origin and corporate reputation on initial trust. Int. Mark. Rev. 2008;25(4):404. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell A.A. In: Wilkie W.L., editor. Volume 6. Association for Customer Research.; Ann Arbor, MI: 1979. Involvement: a potentially important mediator of customer behavior; pp. 191–196. (Advances in Customer Research). [Google Scholar]

- Muncy J.A., Hunt S.D. In: Kinnear T.C., editor. Volume 11. Association for Customer Research.; Provo, UT: 1984. Customer involvement: definitional issues and research directions; pp. 193–196. (Advances in Customer Research). [Google Scholar]

- Namkung Y., Jang S. Does food quality really matter in restaurants? Its impact on customer satisfaction and behavioral intentions. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2007;31(3):387–409. [Google Scholar]

- National Restaurant Association . 2020. Restaurants on Track to Lose $80 Billion in Sales by End of April; 8 Million Employees Out of Work.https://restaurant.org/articles/news/restaurants-on-track-to-lose-$80-billion-in-sales [Google Scholar]

- National Restaurant Association . 2020. 2020 State of the Restaurant-industry.https://restaurant.org/research/reports/state-of-restaurant-industry [Google Scholar]

- Nussbaumer-Streit B., Mayr V., Dobrescu A.I., Chapman A., Persad E., Klerings I., et al. Quarantine alone or in combination with other public health measures to control COVID‐19: a rapid review. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2020;4 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD013574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NYdatabase.com . 2020. COVID-19 NY Bar and Restaurant Violations.http://rochester.nydatabases.com/database/covid-19-ny-bar-and-restaurant-violations October 20. [Google Scholar]

- O’Cass A., Grace D. An exploratory perspective of service brand associations. J. Serv. Mark. 2003;17(5):452–475. [Google Scholar]

- Oches S. QSR; 2012. Meet Your Customer.https://www.qsrmagazine.com/customer-trends/meet-your-custome November. [Google Scholar]

- Pawan M.T., Langgat J., Marzuki K.M. Study on generation Y dining out behavior in Sabah, Malaysia. Int. J. Res. Bus. Soc. Sci. 2014;5(11):92–101. [Google Scholar]

- Pershan C. 2020. The Effect of Coronavirus on American Chinese Restaurants, Explained.https://www.eater.com/2020/2/10/21131642/novel-coronavirus-american-chinese-restaurants-explained Feb 10. [Google Scholar]

- Piron F. Customers’ perceptions of the country‐of‐origin effect on purchasing intentions of (in) conspicuous products. J. Consum. Mark. 2000;17(4):308–321. [Google Scholar]

- Podsakoff P.M., Organ D.W. Self-reports in organizational research: problems and prospects. J. Manage. 1986;12(4):531–544. [Google Scholar]

- Podsakoff P.M., MacKenzie S.B., Podsakoff N.P. Sources of method bias in social science research and recommendations on how to control it. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2012;63:539–569. doi: 10.1146/annurev-psych-120710-100452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preacher K.J., Hayes A.F. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behav. Res. Methods. 2008;40(3):879–891. doi: 10.3758/brm.40.3.879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prebensen N.K., Woo E., Chen J.S., Uysal M. Motivation and involvement as antecedents of the perceived value of the destination experience. J. Travel. Res. 2013;52(2):253–264. [Google Scholar]

- Rifon N.J., LaRose R., Choi S.M. Your privacy is sealed: effects of web privacy seals on trust and personal disclosures. J. Consum. Aff. 2005;39(2):339–362. [Google Scholar]

- Riorini S.V., Widayati C.C. Brand relationship and its effect towards brand evangelism to banking service. Int. Res. J. Bus. Stud. 2016;8(1):33–45. doi: 10.21632/irjbs.8.1.78.33-45. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson R.N., Getz D. Food enthusiasts and tourism: exploring food involvement dimensions. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2016;40(4):432–455. [Google Scholar]

- Roth M.S., Romeo J.B. Matching product catgeory and country image perceptions: a framework for managing country-of-origin effects. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 1992;23(3):477–497. [Google Scholar]

- Ryu K., Jang S. RETRACTED ARTICLE: influence of restaurants’ physical environments on emotion and behavioral intention. Serv. Ind. J. 2008;28(8):1151–1165. [Google Scholar]

- Sahin A., Zehir C., Kitapçı H. The effects of brand experiences, trust and satisfaction on building brand loyalty; an empirical research on global brands. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2011;24:1288–1301. [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez-Franco M.J. The moderating effects of involvement on the relationships between satisfaction, trust and commitment in e-banking. J. Interact. Mark. 2009;23(3):247–258. [Google Scholar]

- Sargent J. SFGATE; 2020. We Asked the CDC What to Do About Wearing Masks.https://www.sfgate.com/shopping/article/should-i-wear-a-mask-coronavirus-CDC-15192780.php April 10. [Google Scholar]

- Schumaker E. 2020. Here Are the States That Have Shut Down Nonessential Businesses.https://abcnews.go.com/Health/states-shut-essential-businesses-map/story?id=69770806 April 3. [Google Scholar]

- Sedgwick P. What is recall bias? BMJ. 2012;344 [Google Scholar]

- ServSafe . National Restaurant Association; 2020. Reopening Guidance for the Restaurant Industry.https://restaurant.org/downloads/pdfs/business/covid19-reopen-guidance.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Shank D.B. Using crowdsourcing websites for sociological research: the case of Amazon Mechanical Turk. Am. Sociol. 2015;47:47–55. [Google Scholar]

- Sheeran P., Trafimow D., Finlay K.A., Norman P. Evidence that the type of person affects the strength of the perceived behavioural control‐intention relationship. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 2002;41(2):253–270. doi: 10.1348/014466602760060129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silver L. ABC news; 2020. Americans Are Critical of China’s Handling of COVID-19, Distrust Information about it from Beijing.https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2020/05/26/americans-are-critical-of-chinas-handling-of-covid-19-distrust-information-about-it-from-beijing/ May 26. [Google Scholar]

- Song H., Van der Veen R., Li G., Chen J.L. The Hong Kong tourist satisfaction index. Ann. Tour. Res. 2012;39(1):459–479. [Google Scholar]

- Srivastava N., Dash S.B., Mookerjee A. Determinants of brand trust in high inherent risk products. Mark. Intell. Plan. 2016;34(3):394–420. [Google Scholar]

- Starr S. QSR Magazine; 2020. COVID-19, and the 4 New Paradigms of Guest Perception.https://www.qsrmagazine.com/outside-insights/covid-19-and-4-new-paradigms-guest-perception May. [Google Scholar]

- Statista . Statista; 2020. Restaurant Industry: Employees US 2019.https://www.statista.com/statistics/203365/projected-restaurant-industry-employment-in-the-us/ August 19. [Google Scholar]

- Strauss M. 2020. China’s Response to COVID-19 Better than U.S.’s, Global Poll Finds.https://www.reuters.com/article/us-health-coronavirus-democracy/chinas-response-to-covid-19-better-than-u-s-s-global-poll-finds-idUSKBN23M1LE June, 15. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor S., Jr. The socially distant servicescape: an investigation of consumer preference’s during the re-opening phase. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2020;91 doi: 10.1016/j.ijhm.2020.102692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thakor M.V. Brand origin: conceptualization and review. J. Consum. Mark. 1996;13(3):27–42. [Google Scholar]

- The New York Times . 2020. See How All 50 States Are Reopening (and Closing Again)https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2020/us/states-reopen-map-coronavirus.html October 20. [Google Scholar]

- Toy S., Hernandez D. What makes bars and restaurants potential Covid-19 hot spots. Wall St. J. 2020 https://www.wsj.com/articles/what-makes-bars-and-restaurants-potential-covid-19-hot-spots-11593768600 July 3. [Google Scholar]

- Tsiros M., Heilman C.M. The effect of expiration dates and perceived risk on purchasing behavior in grocery store perishable categories. J. Mark. 2005;69(2):114–129. [Google Scholar]

- Wang C.L., Li D., Barnes B.R., Ahn J. Country image, product image and customer purchase intention: evidence from an emerging economy. Int. Bus. Rev. 2012;21(6):1041–1051. [Google Scholar]

- Webb T.L., Sheeran P. Does changing behavioral intentions engender behavior change? A meta-analysis of the experimental evidence. Psychol. Bull. 2006;132(2):249–268. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.132.2.249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White P.D., Cundiff E.W. Assessing the quality of industrial products: what is the psychological impact of price and country of manufacture on professional purchasing managers? J. Mark. 1978;42(1):80–86. [Google Scholar]

- Whitehouse . 2020. Guidelines Opening Up American Again.https://www.whitehouse.gov/openingamerica/ [Google Scholar]