Abstract

The hospitality industry has been hard hit by the ongoing pandemic caused by the COVID-19 virus. As restaurants develop comprehensive reopening plans, consumers may still have mixed feelings about simple things such as going out for a meal. This paper explores wellbeing perceptions of restaurant diners. Based on the analysis of semi-structured interviews, this paper reveals that wellbeing in hospitality is a collective concept comprised of multiple domains of a service system, including macro, meso, and micro levels. Furthermore, this paper provides strong support to show that wellbeing is not only sought collectively, but also is determined by consumers’ wellbeing perceptions of both themselves and others around them, and thus contributes to the wellbeing literature in the hospitality domain. Finally, this paper identifies potential concerns regarding crowding and behaviors of other guests, which extends the hospitality literature on perceived territoriality. The theoretical and practical implications are discussed in detail.

Keywords: COVID-19, Coronavirus, Pandemic, Wellbeing, Hospitality, Social distancing, Service ecosystems

1. Introduction

The ongoing COVID-19 pandemic has led to a major global crisis affecting billions of people, creating ‘service mega-disruptions’ and imposing a destructive impact on global economies (Kabadayi et al., 2020a,b). One of the business sectors most severely impacted is the food and beverage industry (Dixon, 2020). According to a McKinsey report, casual-dining and fine-dining restaurants have seen their revenues decline by as much as 85 percent (Haas et al., 2020). In the U.S., the industry is estimated to have lost more than $50 billion in sales in April 2020 as a result of the closure. The German hospitality association Dehoga forecasted a loss of 18 billion Euro in sales by May 2020, and that one-third of businesses would not survive without financial aid from the government (Zeit Online, 2020).

As stay-at-home restrictions are being lifted around the world, restaurant owners in areas where strict public health regulations have been imposed are attempting to devise and implement comprehensive reopening plans, particularly with regard to social distancing (CBRE, 2020). Restaurants have been applying an array of policies and procedures in the scramble to reduce risks and reassure customers (Severson, 2020). Social distancing signs are now a common feature, and face masks have become a standard equipment for both staff and diners.

However, news reports and industry studies indicate that consumers have mixed feelings about simple things such as going out to a restaurant for a meal. According to a recent survey in Australia, where COVID-19 infection cases have been comparatively low compared to other nations, only 40 percent would go to a bar or restaurant (Daniel, 2020). Despite all the efforts to ensure safety in areas that are reopening, many customers still do not feel safe about dining out at restaurants (Rao, 2020). Prior hospitality research has explored the role of territoriality and personal space associated with table distance as an important determinant of diners’ experiences (Hwang et al., 2018; Moon et al., 2020). However, these pre-COVID-19 research projects in hospitality literature have focused on the experience of solo diners. To our knowledge, research is lacking to understand perceived crowding of restaurant diners’ group type (i.e., groups of one’s own, termed ‘in-group’, versus groups of other individuals, referred to as ‘out-group’; Her and Seo, 2018) in a post-COVID-19 environment of social distancing.

Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, social distancing has been studied in the public health context primarily as a disease control strategy undertaken by healthy individuals (Ahmed et al., 2018; Maharaj and Kleczkowski, 2012; Matrajt and Leung, 2020). However, the topic of social distancing and wellbeing is a novel territory, and a “body of work that fuses social distancing with wellbeing and service research is missing” (Finsterwalder, 2020, p. 5). Tuzovic and Kabadayi (2020) propose a framework to understand the impact of social distancing measures on employee wellbeing. Finsterwalder (2020) conceptualizes social distancing as ‘actor distance’ defined as “perceived proximity (remoteness) of the self to objects, subjects or events, and its influence on an actor’s thoughts, feelings and behavior” (Finsterwalder, 2020, p. 6). Given the importance and necessity of social distancing as a measure to fight the pandemic, understanding of how it relates to consumer perceptions of wellbeing is of great interest both for services research and the hospitality literature.

Wellbeing is recognized as a priority of Transformative Service Research (TSR), which advocates that the wellbeing of individuals (consumers and employees) and the overall society are affected by services (Anderson et al., 2013; Anderson and Ostrom, 2015). While wellbeing has received increased attention in hospitality research, a detailed understanding of consumer perceptions of wellbeing is still lacking. Most studies have focused on employee wellbeing, for example, in the contexts of work-related burnout among frontline hospitality personnel in hotels (Walters and Raybould, 2007), of drivers of employee wellbeing from the perspective of hotel property leaders (Ponting, 2020), and of human resource management (HRM) practices of employees in small restaurants (Cajander and Reiman, 2019). In their investigation of the relationships between brand attitude, utilitarian versus hedonic value, wellbeing perception, and behavioral intentions among patrons of chain restaurants, Kim et al. (2012) found that wellbeing perception was the most important determinant of patrons’ positive behavioral intentions. This was supported by recent research by Lin and Chang (2020), who found that in a hotel restaurant context a high level of wellbeing created a strong repurchase intention and increased willingness to recommend afternoon tea to relatives or friends. Similarly, Attri and Kushwaha (2018) suggested that overall wellbeing was considered as an important dimension of customer value perceptions in restaurants. Given the recovery efforts of the hospitality industry in general, and of restaurants in particular, an understanding of consumer wellbeing could be an important step in achieving recovery goals during and after the pandemic.

This paper explores consumers’ process of deciding whether to dine out during the reopening phase of restaurants, as well as their dining experiences and wellbeing perceptions while practicing social distancing at restaurants. More specifically, it investigates the specific factors and dimensions that determine collective wellbeing in the restaurant industry in the COVID-19 era.

This paper makes multiple contributions. A primary contribution is that this is one of the first papers to empirically examine consumers’ dining out decision as government lockdown measures are being eased. The findings will not only help practitioners in the hospitality industry with their reopening and recovery efforts but will also provide them with guidance for similar situations in the future. Second, this paper contributes to the wellbeing literature in the hospitality domain. While previous hospitality research has mostly focused on employee wellbeing, this paper extends that literature by providing a detailed understanding of consumers’ wellbeing perceptions. Finally, while different types of wellbeing have been studied in the literature, this paper contributes to the existing service ecosystem literature by examining collective wellbeing and the ways in which different components contribute to collective wellbeing on a macro-, meso-, and micro-level contribute. Inclusion of all three service system levels provides a better understanding of collective wellbeing, as exchange and interrelationships among actors within and across each system level determine outcomes such as value co-creation and wellbeing (Beirão et al., 2017).

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. The first section reviews subjective and collective perspectives on wellbeing in the literature, which is followed by a discussion of social distancing and the concept of perceived territoriality, as well as the influence of others. Second, we present our exploratory research study of restaurant diners in Germany. Third, the paper summarizes key findings and presents a framework of collective wellbeing that distinguishes multiple domains on the micro-, meso-, and macro-levels of a service system. The paper concludes with implications for hospitality research and practice, as well as presenting future research directions.

2. Theoretical background

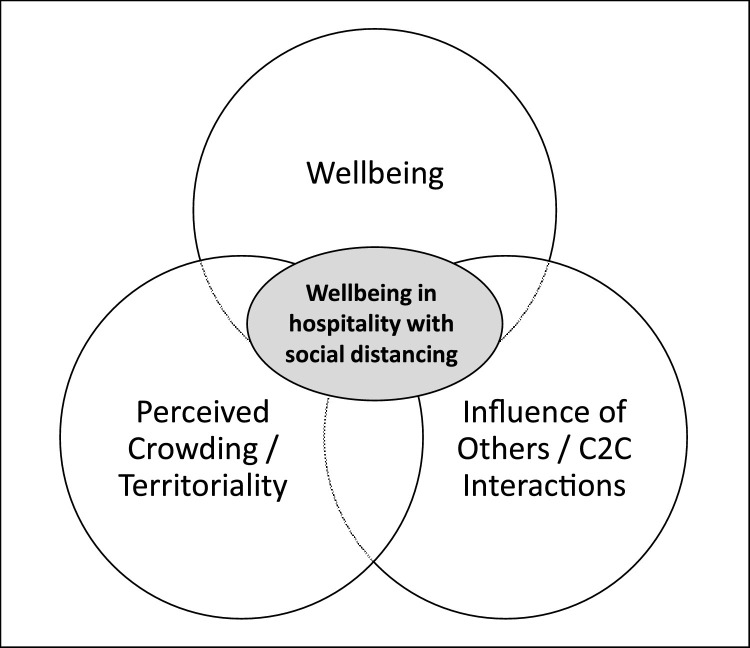

A number of research streams provide important insights for our study. Fig. 1 provides an overview of various domains that include (i) wellbeing literature, (ii) the concepts of perceived crowding and territoriality, and (iii) customer-to-customer (C2C) interactions and the influence of others.

Fig. 1.

Overview of relevant literature streams.

2.1. Subjective wellbeing

Subjective wellbeing is a broad category of phenomena and describes the global judgments of life satisfaction and emotions that range from depression to happiness (Diener and Ryan, 2009). It denotes a self-reported measure of wellbeing, including cognitive and affective perception as well as evaluation of life (Diener et al., 2018a). The cognitive aspect of subjective wellbeing refers to individuals’ assessment of both their overall life satisfaction and satisfaction with particular areas of their lives, such as jobs or relationships. Such cognitive evaluations contribute to individuals’ wellbeing, as they reflect reactions to positive and negative life experiences. Alternatively, the affective aspect of subjective wellbeing refers to individuals’ mood, emotions, and feelings. It reflects the presence of either a positive affect such as happiness, satisfaction, or joy, or of a negative affect such as tension, fear, or stress (Ryff, 1989). Such subjective assessments of wellbeing usually emerge from actions and experiences, and result from such factors as good health, prosperity, and a sense of meaning or purpose in life (Diener et al., 2018b).

Similarly, the concept of wellbeing is viewed as having two interconnected types— hedonic and eudemonic (Ryan and Deci, 2001; Verduyn et al., 2017). Hedonic wellbeing refers to individuals’ attainment of happiness through achieving desired life conditions and gaining material pleasures, whereas eudemonic wellbeing denotes achievement of meaning in life through personal growth, belonging, and autonomy, as well as becoming the best possible in one or in all of the life domains (Kjell et al., 2016; Ryan and Deci, 2001).

Although there is no universally agreed-upon definition or conceptualization of wellbeing, it is viewed as a multidimensional phenomenon. While different dimensions have been offered in the extant literature, five dimensions have become prevalent and been frequently used in studies across different fields. These five dimensions are:

-

•

Physical wellbeing, referring to individuals’ overall physical health, strength, and function of their bodies and bodily functions.

-

•

Emotional wellbeing, denoting individuals’ ability to practice stress-management techniques, to be resilient, and to generate emotions that lead to good feelings (Strout and Howard, 2012). Skills such as self-confidence and positive thinking help to develop emotional wellbeing.

-

•

Social wellbeing, reflecting an individual’s ability to communicate, develop meaningful relationships with others, and maintain a support network that helps to overcome feelings such as loneliness or depression.

-

•

Spiritual wellbeing, about acquiring purpose in life and denoting the ability to have a set of guiding beliefs, principles, or values that give direction to their lives (Strout and Howard, 2012).

-

•

Financial wellbeing, addressing individuals’ ability to sustain their desired living standards and financial freedom (both current and anticipated) (Brüggen et al., 2017), and denoting feeling safe about their future financial state (Netemeyer et al., 2018).

The five dimensions collectively define individuals’ levels of overall wellbeing in different settings (e.g., Kabadayi et al., 2020a,b).

2.2. Collective wellbeing

While the original conceptualization of wellbeing has been done at the individual level, reflecting an individual’s assessment of living a good life, later revised conceptualizations included those individuals’ desire to live a good life. This is an important distinction, as it adds the importance of the collective dimension to subjective wellbeing (White, 2010). Furthermore, conceptualization of wellbeing at the individual level lacks an acknowledgement of the individual’s experience of the broader contextual and social interrelations that influence his or her wellbeing (Leo et al., 2019). Therefore, contrary to the common usage, it is very likely that wellbeing is sought collectively, and it may be more properly identified at the collective level than at the individual level (Nelson and Prilleltensky, 2005).

Collective wellbeing refers to the sense of satisfaction or happiness that is derived from or is related to the collective dimension of the self, of social relationships, and of context (Sung and Phillips, 2018). Such collective wellbeing reflects the sum of the wellbeing levels of individuals who belong to a certain community, or it considers wellbeing as something that resides in the community as a collectivity (White, 2010). In other words, the wellbeing of an individual is highly dependent on the wellbeing of his or her relationships and on the community in which he/she resides. The promotion of collective wellbeing also enhances individual wellbeing (Evans and Prilleltensky, 2007). Similarly, individuals’ participation in a service ecosystem can impact their wellbeing, and those individuals’ accumulated wellbeing experiences contribute to that system’s collective wellbeing (Baccarani and Cassia, 2017). In short, the link between individual wellbeing and community is central to contemporary conceptualizations of wellbeing, and there is a recognition that individual and collective levels are inherently interconnected (Gallan et al., 2019).

2.3. Social distancing, crowding, and perceived territoriality

Since the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic, medical and public health experts have recommended various measures to slow down the transmission of the virus. The most commonly recommended measure has been social distancing, which refers to “efforts that aim […] to decrease or interrupt transmission of COVID-19 in a population (sub-)group by minimizing physical contact between […] individuals, or between population groups with high rates of transmission and population groups with no or a low level of transmission” (ECDC, 2020, p. 2). In public, the common recommendation of reducing physical interaction with other people is to maintain at least 6 feet (or 2 m) of distance between people (CDC, 2020).

While social distancing as a disease control strategy helped to slow the spread of COVID-19, experts contemplated its impact on public mental health and wellbeing. For instance, some governments provided advice for citizens to learn how to stay connected while being physically apart (e.g., Queensland Health, 2020). And recent research in psychology has begun to examine effects of social disconnection due to social distancing measures on psychological wellbeing (e.g., Ford, 2020).

Paradoxically, the advice to maintain distance in public can lead to perceived crowding, which is a psychological state based on the number of individuals inside a store or restaurant, the extent of social interactions, and the configuration of the interior layout (Vredenburg and Phillips, 2020). Recent hospitality literature makes a similar argument—that the level of crowding in a restaurant is a result of “the number of other consumers and the spatial closeness, as the number of other consumers and the seating proximity increase in a crowded setting” (Her and Seo, 2018, p. 17).

Retail and hospitality research has investigated the effect of crowding on consumer outcomes (e.g., Eroglu et al., 2005; Grewal et al., 2003; Hwang et al., 2012). Studies in retailing have shown that perceived crowding can lead to less positive emotions and decreased satisfaction (e.g., Byun and Mann, 2011; Eroglu et al., 2005; Machleit et al., 2000). Similar research in consumer psychology also showed that physical proximity with other consumers can lead to violations of personal space, thus making consumers feel uncomfortable (Xu et al., 2012).

In hospitality literature, research has focused on solo diners, studying the influence of physical environment on consumer emotions, and the role of spatial layouts and crowding on consumers’ solo dining experiences (e.g., Her and Seo, 2018; Hwang et al., 2018; Moon et al., 2020). According to the solo dining literature, ‘spatial closeness’ with others leads to high levels of perceived crowding which, in turn, negatively influences the overall restaurant experience of solo diners (Her and Seo, 2018). Moon et al. (2020) adopted human territoriality theory (Sack, 1983) for the solo dining context in order to study physical and psychological boundaries and their impact on overall satisfaction and revisit intentions. Their results showed that inter-table distance was found to be the most important boundary factor for improving solo diners’ perceived territoriality. However, Robson et al. (2011) argued that the context of the dining experience (e.g., a business lunch, a family occasion) was likely to be a key factor in consumers’ preferences for table spacing, and for their subsequent revisit intentions.

While previous research on personal space and territoriality are primarily related to the issue of privacy (e.g., Abu-Obeid and Al-Homoud, 2000; Moon et al., 2020), the topic of providing and/or maintaining physical distance has now become a key element for devising reopening strategies in a COVID-19 environment. Research has yet to investigate how readily consumers will adapt to the etiquette of post-pandemic socially distanced dining, and how it will affect their perceptions of wellbeing. Furthermore, research is lacking to understand social distance between ‘in-group’ and ‘out-group’ restaurant diners.

2.4. Customer-to-customer (C2C) interactions and influence of others

Extant research has investigated the relationship between interactions with service providers during service delivery and customer perceptions of service quality or satisfaction (e.g., Bitner et al., 1994; Srivastava and Kaul, 2014). In addition to interactions with employees, customers interact with other customers during service delivery or co-creation in many service settings. The topic of customer-to-customer interactions (CCI) has gained considerable attention in academia, as in the examples of branding (Bruhn et al., 2014), services marketing (Nicholls and Mohsen, 2019), and hospitality and tourism (Lin et al., 2019, 2020). Studies in different contexts have found that CCI can have a significant influence on customer experience, emotions, and satisfaction (Choi and Kim, 2013; Huang and Hsu, 2010; Tomazelli et al., 2017; Yoo et al., 2012).

In hospitality literature, Hwang et al. (2018) adopted social impact theory (Latane, 1981) to investigate the moderating effect of power on the impact that spatial distance imposed on enjoyment of the solo dining experience. The authors posited that in a solo consumption context, when the spatial distance is small (vs. large), the social presence of others became salient. Their study also found that powerful individuals were less attentive to the judgment of others, and thus their dining experience was less affected by spatial distance. Additionally, the authors documented a boundary condition where proximity with other consumers improved solo consumption experiences (Hwang et al., 2018). The results are in line with Lin et al. (2020), who examined the relationship between nonverbal CCIs and positive (versus negative) emotions, customer satisfaction and loyalty intentions. Their findings suggested that other customers invading the personal space of focal customers could generate negative emotions, while keeping a proper distance from focal customers was not likely to have an impact on their emotional state.

A limited number of studies in hospitality literature have investigated the relationship between CCI and wellbeing. For example, Altinay et al. (2019) explored how CCIs affected the wellbeing of customers, particularly that of elderly customers in hospitality settings (including cafés and restaurants). Their results showed that, in a hospitality setting, positive social interactions with other customers could strengthen feelings of inclusiveness and positive emotions among elderly customers (Altinay et al., 2019).

While these studies all provide insights for a better understanding of CCIs, the influence of others has gained specific relevance in the context of COVID-19. Various news reports demonstrate the negative and ugly side of CCI, such as ‘social distance shaming’ (Noor, 2020) and/or ‘social distancing renegades’ (Ryan, 2020), that can lead to confrontations between customers, and thus affect both those customers’ wellbeing and that of their surrounding community. Given such increased tensions in the COVID-19 environment, it is essential to conduct new research in the area of CCIs and social distancing, which is particularly salient in the hospitality industry.

3. Methodology

3.1. Research design

The purpose of this study was to investigate the nature of wellbeing perceptions among restaurant diners after government lockdown measures have been eased. While the food service industry consists of a broad spectrum of establishments (Lippert et al., 2020), the focus of our study was on casual and/or fine dining restaurants rather than fast-service restaurants, due to their wide consumer populations and their combination of utilitarian and hedonic functions, involving the quality of both food and service (Her and Seo, 2018).

Within the food service industry, the topicality of the pandemic, in combination with resulting social distancing policies, will influence consumer perceptions of wellbeing for dining in full-service restaurants in ways that have not yet been widely explored. Hence, for our study it was appropriate to adopt an exploratory qualitative research design (Denzin and Lincoln, 2008; Mays and Pope, 1995).

The present study is based on qualitative data obtained from in-depth interviews with consumers in Germany who had a dining experience soon after the easing of lockdown in mid-May. Across Europe, the severity and timing of both lockdown measures and lifting of restrictions has differed from country to country (see Hirsch, 2020a,b). In Germany, a partial lockdown was implemented in mid-March, with rules differing across states, compared to a strict lockdown in Italy and Spain. Across Europe, the timeline for the reopening of businesses (primarily from April to May) varied as well. The German government announced on May 6 that all stores could reopen under strict hygiene measures, with individual states having the option to announce further steps (Hirsch, 2020b). For the hospitality industry specifically, German authorities stipulated a variety of regulations, including capacity limits, mandatory sign-in lists, and the wearing of face masks (rbb24, 2020).

3.2. Data collection and sampling

In accordance with the outlined research objectives, a purposive sample population was considered for this study (Patton, 2015; Suri, 2011). Participants were recruited on the basis of two criteria: (a) they must be at least 18 years of age, and (b) they must have recently visited a full-service restaurant after the reopening of restaurants. The selection of interview participants was based on previous studies in the hospitality sector (e.g., Putra and Cho, 2019) that used a variety of sampling techniques—predominantly a combination of snowball and convenience sampling. Initial participants recommended additional contacts from their social networks who also had a recent dining experience in a sit-down restaurant. In order to avoid a homogeneous composition of respondents that might result from snowballing, we pursued a goal of attracting people from different social backgrounds to the study. In this way we were able to recruit a heterogeneous group of interview participants from diverse social strata, with different professions, income levels, educational qualifications, religions, marital status, and age groups. As well, we were able to include a range of attitudes toward the topic of restaurant visits.

We collected data over a four-week period, from May to the beginning of June 2020, conducting semi-structured individual interviews with 15 participants through the videoconferencing software Zoom. We deemed the sample size of 15 to be appropriate for two reasons. First, the outbreak of COVID-19 has adversely impacted qualitative research. Research that traditionally took place in person, mainly interviews or focus groups, was forced to transition to using new virtual tools and platforms. Industry reports (e.g., Remesh, 2020) suggest that the uncertainties of the pandemic have influenced recruiting, sampling, and participant behavior. This has made the work for market researchers more “cumbersome” (Remesh, 2020). In addition to the special conditions that COVID-19 imposes on qualitative research, another reason for the sampling size presented here was the saturation of the qualitative data, which was reflected in the increasing redundancy of the response patterns (Boddy, 2016). Half of the participants in our sample were female. Participants varied in age from 18 to 65 years, skewing toward younger consumers.

A German-language interview guide presented questions stemming from key themes identified from our literature review. Using such a scientifically developed guideline for the interviews ensured that the interviews would be conducted in a systematic, consistent, and comprehensive manner (Patton, 2015). The interview guide consisted of three sections: (1) pre-visit considerations and/or health concerns about restaurants since reopening, (2) perceived servicescape, territoriality, and social distancing policies, and (3) wellbeing of self and others during dining. The in-depth personal interviews lasted between 45 and 60 min.

3.3. Data analysis

All interviews were audio and video recorded and transcribed verbatim. Transcripts were read to ensure their correctness and then imported into NVivo, a qualitative data analysis software platform. Similar to prior qualitative research in hospitality (e.g., Putra and Cho, 2019; Zhang et al., 2019), the interview data was subjected to thematic analysis (Braun and Clarke, 2006), which began with one of the authors independently coding the raw data. Thematic analysis is suitable for discovering emerging themes within the raw data, and it is useful to describe the data in detail (Braun and Clarke, 2006). While single coder research can produce biased results that affect measurement reliability (Roh et al., 2013), scholars have argued that the reality of many qualitative research projects is that a single coder codes the majority of the data (Campbell et al., 2013; O’Connor and Joffe, 2020).

Adopting an integrative inductive/deductive research approach, the thematic analysis involved three phases. In the first phase we applied open coding, i.e. the textual data was analyzed line-by-line to identify relevant concepts based on the actual language that the participants used. Phase 2 followed with axial coding that involved using supplementary literature to contextualize the open codes into pre-defined codes. Lastly, in Phase 3, we used selective coding to group axial codes into broader themes. We developed the coding structure in the context of critical discussion and reflection among the co-authors. This involved regular Zoom/Skype meetings to check reliability and consistency and to resolve discrepancies. Similar to other studies, external validity was enhanced by drawing analytical conclusions based on the literature review.

4. Results

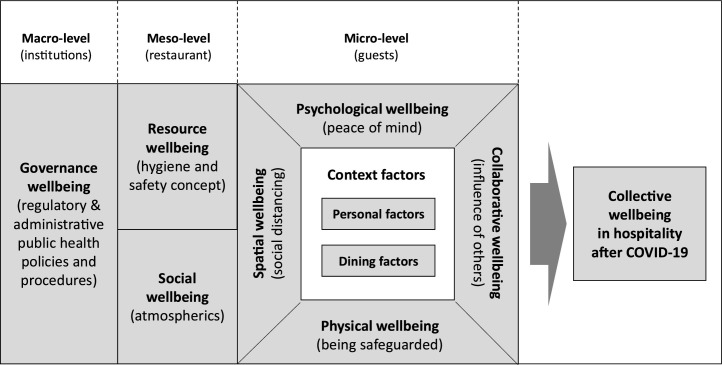

The results are presented as follows.1 First, we discuss different domains of wellbeing in hospitality services in a ‘new-normal’ COVID-19 environment. Second, we highlight several context factors that emerged from the interviews. Fig. 2 summarizes the proposed framework of collective wellbeing domains.

Fig. 2.

Framework of collective wellbeing domains.

4.1. Macro-level wellbeing domain

Macro-level in a service system refers to the broader societal structures embedded within socio-cultural systems that include institutionalized norms and values (e.g., laws, political debates, media) (Beirão et al., 2017). On a macro-level, we identified governance wellbeing as an essential domain that influences consumers’ dining decisions. According to Leo et al. (2019, p. 776), “governance wellbeing exists when a system provides well-functioning central regulatory and administrative policies and procedures that enable smooth operations for its actors.” In the ‘new-normal’ environment of COVID-19, restaurant operators and consumers must adhere to public health regulations such as social distancing. Our data suggest that participants were very satisfied with the actions and rules that the German government issued in connection with COVID-19, and that they felt safe and comfortable with these regulations. This generally speaks to a very high level of trust in the federal government. One interview participant said:

So I think, compared to other countries, you can see that the response in Germany was very good. (IP4)

The interview partners showed understanding for the restrictions:

I think the higher-level rules are good because they ensure our safety. (IP1)

Respondents assessed the federal government’s measures on the basis of the levels of hospitalization and the number of deaths. Such feedback suggests that the measures were successful and protected the population. In addition, the measures were repeatedly adapted in response to current conditions, which also signaled to the public that the government has COVID-19 under control.

Yes, I think the measures were right because of the number of infections, which then also went down. And that, because of the decreasing numbers, they can now ease more of the restrictions. (IP2)

A unique aspect in Germany is federalism, wherein each state (e.g., Bavaria, North Rhine-Westphalia) can issue its own rules and measures in a self-determined and independent manner. Many interviewees criticized the independent action of several states, as there were too many different rules per state, leading to uncertainty and confusion among the residents. In Bavaria and North Rhine-Westphalia, for example, ten people from different households are allowed to sit at one table, whereas in Berlin only six people are allowed. Furthermore, specific social distancing rules vary across states. For instance, in Hesse a minimum distance of 1.5 m between guests at a table is still mandatory; yet other states do not mandate social distancing rules. One participant complained:

This federalism in Germany is fundamentally problematic. We do not have consistent rules. That even if, for example, you have a family in another federal state and then want to travel there, you suddenly have to consider completely different rules. That you can suddenly be fined €500 when you cross the border. So, no consistent measures were taken due to federalism. (IP4)

As the number of infected people continues to decline, Germans’ desire to regain their freedom grows. People are beginning to put pressure on the authorities and demand immediate easing of the restrictions:

Recently, in the last few days and weeks you can feel that a certain impatience has opened up in Germany, people are getting restless and many people really have a stronger urge for freedom. (IP3)

The actions of local authorities are also related to governance wellbeing. Our data shows that respondents are less satisfied with local authorities than with the federal government. For example, respondents pointed out that local police have shown little public presence to enforce regulations. In addition, no controls are established to ensure that people are aware of and are maintaining hygiene and protective measures. Many respondents observed obvious violations such as crowding, but the authorities did not intervene and did not ensure that the protective measures were followed. One participant explains a personal experience:

Yes, it’s the city’s responsibility, I mean, to control the measures. I saw people gathering in large groups. At that time, it was really forbidden … [gathering in groups] was really penalized [with fines]. And there was no public order officer anywhere to be seen. Not even in the park. And I found that frightening, because I believe that not everyone is so responsible and will follow the regulation. Some people need a little extra help in the sense that the local police is also present and then also passes out penalties when it becomes necessary. Yes, that is the point where I was dissatisfied. (IP10)

To summarize, governance wellbeing is an important domain that influences consumers’ decision to dine out. When the national government began to allow restaurants to re-open, many people had trust in this decision, and were happy to regain a bit of normality.

4.2. Meso-level wellbeing domains

Meso-level in a service system denotes the mid-range layer of the service exchange, describing organizational or community levels of relationships and interactions (Beirão et al., 2017). On a meso level, our findings point to two key domains: resource wellbeing and social wellbeing.

(1) Resource wellbeing

Resource wellbeing refers to a service system that “provides actors with access to resources to fulfil their roles and to perform their day-to-day activities” (Leo et al., 2019, p. 777). In the post COVID-19 environment, restaurants are implementing a variety of sanitation, hygiene, and social distancing measures that affect all actors in the service system.

-

•

The role of restaurant owners and operators

Restaurant owners or operators play a central role for ensuring the wellbeing of both their guests and their employees. The interview participants clearly view restaurant owners as being responsible for implementing the safety measures and regulations that the state or local authorities mandate. Furthermore, restaurant owners or operators are seen as a superior authority, responsible not only for the implementation of all the requirements, but also for ensuring that employees and guests follow these rules (e.g., sanitation, hygiene, and social distancing measures).

The restaurant is of course responsible for implementing the hygiene measures set by the state. They are liable for the proper execution. And also make sure that this is kept during operation. (IP6)

This gives the restaurant operators a special position during the COVID-19 crisis that entails a lot of responsibility. However, interview participants also pointed out that the wellbeing of the guests must always come first.

This should be in the interest of the restaurant owner, because only guests who feel comfortable come back. (IP15)

The results suggest that restaurant owners can take on the important function of role model for employees and guests by following all rules, wearing masks, regularly disinfecting hands, and keeping their distance, thus setting a good example. In addition to these higher-level responsibilities, restaurants should provide guidance and information for their guests to help them overcome uncertainty and perceived risks.

-

•

Providing a COVID-safe plan for the protection of guests and employees

The interview data suggest that restaurants are expected to provide assistance (e.g., instructions) to their guests in order to minimize their initial insecurity and uncertainty. All such measures taken by the restaurant demonstrate their preparedness for dealing with the new COVID-19 situation. While mandated by public health regulations, implementation of a hygiene and safety concept is essential for restaurants in order to provide guests with a feeling of security. In contrast to their own homes, individuals cannot themselves influence and control the measures; therefore, they are dependent on the restaurant operator and must rely on the latter. Respondents consider a number of measures to be particularly useful. First, participants emphasize that making information about a restaurant and its new safety and hygiene measures available on the website or by telephone is particularly helpful, so that patrons can know in advance the changes and new procedures implemented by the restaurant. As one participant describes the restaurant selection process:

Then it was also important during the selection that the restaurant already had some information on the internet page how to proceed. (IP1)

Second, the provision of hand sanitizers and disinfectants at the entrance to the restaurant and on the sanitary facilities is described as an absolute must, so that both guests and staff can disinfect their hands easily and often. Masks should be provided for the employees and should be distributed to guests who do not bring their own masks. In times of general insecurity, it is helpful for guests to be given sufficient assistance in understanding proper behavior—for example, for being inside the restaurant and for interacting with others. If guests are aware of these expectations, they can adjust their behavior accordingly and enjoy their time in the restaurant. For example, signs and displays provide important information for the guests about where they should wait until they are directed to the table. Participants also found visual floor markings that indicate walking paths within the restaurant to be extremely helpful to avoid being too close to other guests. The provision of masks and disinfection in sufficient quantity, and a well-considered plan for the protection of guests and employees are important indicators that contribute to the wellbeing of the guests. Such measures signal to guest that the restaurant operators care and are doing everything possible to make guests feel comfortable and safe, just as they would in their own homes. If such basic measures are not followed, patrons perceive that the restaurant operator lacks concern for the wellbeing of guests and employees, which may prevent guests from visiting the restaurant again.

-

•

Demonstrating a safe work environment

Finally, it must be ensured that guests not only observe the hygiene and safety plan imposed by the restaurant, but employees must adhere to the new measures in order to increase the wellbeing of the guests. This includes several work procedures, such as employees being required to wear masks, regularly disinfecting their hands, and keeping sufficient distance from the guests. These work procedures are particularly important when handling food and beverages. The health and hygiene practices of employees have a significant influence on the dining experience of the guests. Some participants report having had negative experiences with employees who did not follow the rules, such as not wearing the mask properly. It is clearly the responsibility of the owner of the restaurant to ensure that employees follow the rules.

The waitress, who sometimes just put her mask down, had the mask hanging over her lips and did not cover her nose at all. That sometimes made me nervous. (IP3)

(2) Social wellbeing

In addition to resource wellbeing, we identified social wellbeing as the second key domain on a meso-level. Social wellbeing means that “a service system provides actors with social connections and a sense of connectedness within the system” (Leo et al., 2019, p. 778). For the purposes of our paper, we propose that social wellbeing is developed from the restaurant’s level of atmospherics and sociability, which we evaluate through the factors of physical environment, service employees’ social behavior, and the presence of other guests in the restaurant.

-

•

Providing comforting atmospherics

One part of the atmosphere that forms social wellbeing is guests’ recognition of the restaurant and its familiar structures. Many patrons expect a complete change of the interior, especially in the effort to position tables differently to accommodate social distancing. Some guests fear that having fewer people and fewer tables inside the familiar restaurant could create an uncomfortable atmosphere. However, participants seemed surprised, but positively so, about the new layout of the restaurants, and were very pleased that the coziness and pleasant atmosphere they knew previously had been maintained despite the new rules.

I was really surprised that it was so pleasant. The atmosphere hasn’t changed, despite fewer tables. On the contrary, there were more plants between the tables and new decorations. That really made a difference and was totally cozy as always. (IP12)

-

•

The role of employees

Employees are responsible for ensuring that guests feel comfortable, which contributes to the social wellbeing of guests. Feeling good means that guests are able to forget COVID-19 for a short time and enjoy their meal without discomfort. Guests are happy when they recognize a familiar face, signaling that some things have not changed because of COVID-19. Through small talk, food recommendations, and individual attention, employees can help guests have a carefree and enjoyable dining experience.

The employee played a very important role here, because, as I said, he took away a lot of the uncertainty. And also, as always, he was very friendly and accurate. (IP10)

Some guests feel a bit lost when first entering a restaurant. Participants acknowledged that receiving a quick response from the staff, being escorting safely to their table, and having changes explained are extremely helpful in reducing negative feelings.

When I think about it now, these little things, for example, not standing right next to you, having a mask on all the time, has already made you feel safe. (IP6)

-

•

The role of other guests

The majority of participants also emphasized that the presence of other guests in the restaurant contributes strongly to the mood and atmosphere.

I think a restaurant has a lot more joy of life and energy when there are a lot of people in it. Because the conversation of the other people, now of course not listened to, but in the background and also has these other people simply present there. So that simply creates a completely different atmosphere for me. (IP3)

It simply creates a different atmosphere when people talk. When that vibrancy is there. For example, when you hear the laughter of other people who are having fun, that brings up emotions in me that I have more joy in this evening. But it relaxes the whole atmosphere. (IP5)

In general, the interview participants observed that indoor facilities of restaurants were less frequented. This is partly due to the new rules that allow fewer people to eat inside but is also a result of the warm and sunny weather during the time of our study that prompted many guests to sit outside on the terrace. As well, there are still many people who are not yet comfortable with dining inside a restaurant. Those who have eaten inside said that they felt a little isolated when so few tables were occupied. The mere presence of other guests can contribute to the wellbeing inside the restaurant because the feeling of normality is here again conveyed, especially after a long time of social isolation (“And that is something that you were not so aware of before. How much you, yes, how much you need social contact”, IP1). But if guests sit inside a restaurant where there are few other guests, they get the impression that something is not right. As well, having tables set far apart may remind guests of the pandemic.

The conversation of other guests can also have an effect on the social wellbeing of everyone present. If there is a lot of talk about COVID-19, guests are reminded of the pandemic situation and cannot enjoy their evening to the utmost.

The atmosphere was different. It was like that, you do like to listen to others, just a little bit. Snippets of words that you pick up. And it was like that at every table there was talking about Corona. (IP1)

4.3. Micro-level wellbeing domains

Finally, micro-level refers to service experiences and activities at the individual level, including customer-employee interactions or interactions among individual customers (Beirão et al., 2017). We identified four domains of wellbeing on a micro-level: psychological, physical, spatial, and collaborative.

(1) Physical wellbeing

Physical wellbeing, in general, refers to individuals’ overall physical health, strength, and body functions (Strout and Howard, 2012). In the current context, we propose that physical wellbeing describes the extent to which actors in a service system perceive being safeguarded from physical harm. It was interesting to learn that at no time during the restaurant visit did participants truly worry about potential COVID-19 transmission. Trusting the actions taken by the restaurant, guests felt safe, as if they were in another world, as soon as they entered the restaurant and took off their masks.

I never had any safety concerns in the form of fear that I would be infected now, no never. (IP 3)

One explanation is that guests trust the measures that restaurants implement to protect their guests, such as increased distancing.

So when I was sitting, that was no longer an issue. As I said, it was somehow a bit of a separate thing, because the tables next to it were not so close. (IP7)

Another explanation could be that the participants in our sample do not belong to the risk groups, and therefore have not perceived any direct threat to themselves. However, participants did indicate that they are more concerned about family members who belong to risk groups due to age (e.g., grandparents) or previous illnesses.

As far as the family is concerned, I’m mostly concerned about the grandparents. They are over 80, or rather are becoming 80 now, which is already where you keep thinking, oh please don’t, even if now with the easing. (IP7)

(2) Psychological wellbeing

Psychological wellbeing, in general, denotes an individual’s ability to practice stress-management techniques, to be resilient, and to generate emotions that lead to good feelings (Strout and Howard, 2012). In the current context, we use the term of psychological wellbeing to describe the extent to which actors in a service system perceive being relieved from worries and stress. Participants indicated that they are looking forward to finally going to a restaurant again. Such a visit is a way to escape from everyday life, and is also a signal that things are slowly starting to improve. People want to forget their daily routine and finally treat themselves to something nice after a long time of social isolation.

So you often go out to a restaurant or a bar to forget the everyday life, or the problems and to focus on something else. (IP 12)

Most interviewees are aware of the dangers caused by COVID-19. They follow the infection numbers on a daily basis, and stress that the pandemic is not over yet. However, it is also clear to them that each individual is primarily responsible for protecting himself or herself from the virus. People cannot hand over the responsibility to the state or to restaurants or to fellow human beings, but they have to look after and protect themselves.

Well, I would say that the responsibility, even if you look at it in general terms, lies with everyone, of course, that you take care to protect yourself and others. (IP10)

Apart from the responsibility and the joy of normality, many participants still have a feeling of uncertainty in these times of COVID-19, which impacts their psychological wellbeing. Among the study respondents, uncertainty is caused by the fact that there are many different rules and that each individual can interpret and implement those rules differently. As well, respondents often fear that they may not know the current rules, and will do something wrong as a result. For example, they may not know whether they should wear a mask while on the restaurant terrace. Many people are not quite clear what is expected of them as guests. For this reason, many of our interview participants had the attitude of waiting to see how the situation develops in order to know which rules and behavior patterns will prevail.

Wait and see, so that you do everything right. (IP9)

(3) Spatial wellbeing

We propose the term spatial wellbeing to describe a service system that builds and maintains a well-designed space that reduces any sense of perceived crowding and that provides actors (i.e. restaurant staff and guests) with increased physical distancing within the service environment. Our findings indicate that the layout and space that is available in a restaurant is an important consideration for all of the participants. Interviewees agreed that social distancing is the most effective measure to reduce the spread of COVID-19. For restaurants, this means that tables must be set apart so that there is sufficient space between them. Participants mentioned that they pay extra attention to maintaining social distance, so providing enough space between the tables gives guests a more secure feeling.

That was important, we also paid attention to how we or where we sit. (IP6)

Furthermore, potential crowding inside the restaurant (for example, near toilets or corridors) is perceived unfavorably. Participants pointed to the creativity of the restaurant operators in creating an effective mix of closeness and distance—for example, by implementing signs or walking path markings that support consumers’ orientation within the space. Also, clearly marking entrances and exits is essential, so that guests do not have to pass each other unnecessarily.

I had to find my way around to go to the toilet, in order not to disturb anyone there and not to put myself in an uncomfortable situation. (IP12)

However, spatial wellbeing is a rather complex issue. On the one hand, guests do not want to sit too close to each other, to avoid possible COVID-19 transmission, but they also do not want to be isolated from other visitors. For instance, having just two persons sitting at a big table creates an awkward atmosphere, which in turn affects the perception of social wellbeing. When tables were set farther apart, respondents had the feeling of being isolated from the other guests (out-group).

Well, […] the sense of community wasn’t really there, I’d say. IP13

However, this table configuration allowed them to better concentrate on their dining partners or their own company (in-group).

Because for me, socializing comes from the people I’m with. And since it is now also allowed to come with the family to the restaurant, or with several friends, these are the people who make up the sociability for me. (IP4)

(4) Collaborative wellbeing

As mentioned above, the presence of others is an essential component of social wellbeing. Our findings further indicate that CCIs play a role in guests’ subjective wellbeing. To indicate the influence of others and the role of CCIs, we adopt the term collaborative wellbeing, which refers to well-functioning relationships among actors in a service system (Leo et al., 2019). In the current context, this includes the ways in which patrons adhere to norms and rules of social distancing and to other public health regulations. The interviews show that people are more concerned about the behavior of other customers during their restaurant visit. In some cases, people also closely observe others, to check whether everyone is adhering to the hygiene and protection measures. For instance, many of our interview respondents indicated that, in the current conditions, if the policy on wearing masks in restaurants was eliminated, they would feel that indoor restaurants are too risky.

I think I would rather not go out to eat, I would say, then the risk would be too high. (IP6)

People are careful themselves, and look around to observe what others do. They are paying greater attention to other people around them, while they do not want to endanger others with their own behavior. There are exceptions, of course. Our participants noted that when larger groups came into a restaurant, they often behaved rather inconsiderately and ignored the rules—for instance, they did not wait until they were accompanied to a table. According to social impact theory (Latane, 1981), people are influenced by the imagined, implied, or real presence/actions of others (Hwang et al., 2018). In the present case social behavior of a larger out-group may become more salient and observable among in-group members.

Furthermore, participants observed that some servers do not take their hygiene seriously enough and complain to the guests that they cannot breathe under the mask. When the rules are not followed by the large group, the result is a negative impact on the restaurant visit for individuals and small groups. One participant described a situation in a restaurant, in which one guest was not wearing a mask:

I thought it was irresponsible. As I said, I even followed the recommendation. Not only what was really required by law, but also recommendations […] but in the restaurant nobody said anything. So no other guests or waiters. I could not understand that. Such persons should be banned from the restaurant. (IP3)

In addition to not wearing masks, the violation of social distancing rules by other guests also caused discomfort for many of the interviewees, which relates to the previous domain of spatial wellbeing.

4.4. Personal and dining-related context factors

The interview data further suggest several personal and dining-related factors that may have an influence on participants’ dining experiences and their perceptions of overall collective wellbeing.

-

•

Dining motivations

Participants report that their initial visit to the restaurant after the easing of the restrictions was something special for them. Since many of them had planned the visit in advance, the respondents developed a kind of joyful anticipation of the restaurant visit. It seems that people appreciate the moment of going out and enjoy the food more because they are so happy about their newly gained freedom.

Yes, so we sat there, and I was still happy that we finally had dinner. But also maybe because I was in such a good mood. I don’t know. Because we couldn’t have dinner for so long. Because it was special. And it had become a bit of a habit before that. (IP8)

With regard to the selection of a restaurant, it is clear that people are more likely to go to those restaurants that are most familiar to them because they know the environment and/or the staff and can thus minimize their uncertainty about the restaurant visit. Additionally, it seems that participants intentionally choose their favorite restaurant so that they regain a feeling of normality in their lives. However, some participants seemed very tense or nervous because they did not know exactly what to expect and were uncertain about how a restaurant visit has changed in the times of COVID-19.

I thought it was nice, and that was a feeling of normality for me again, because the visit was actually relatively normal. (IP11)

Some guests even went so far as to describe the situation and experience as being even better than before the pandemic.

I would actually describe the whole experience as even more enjoyable than before Corona. (IP2)

An interesting result was that some participants enjoyed the food much more and ordered dishes that they would never have chosen otherwise.

I ordered the fish. I never do that. Usually I always take the noodles. But I wanted to treat myself to something special, which I hadn't had for a long time. (IP5)

In addition, some participants reported that the taste of their food was much more intense, and they appreciated this new taste experience.

It tasted incredibly good. Such intense aromas. A real explosion of taste. (IP9)

-

•

Personal factors

While interviewees tended to provide consistent responses, we noticed some differences among the participants, due to personal factors. Specifically, we identify gender, risk perception, and personality as individual factors. Women seem to have missed going out and eating out more than men. They repeatedly report that they are looking forward to going back to the restaurant because it is a special moment for them. They are also looking forward to dressing up for the event.

Finally another environment and I have also dressed me up for this occasion, hair, make-up, that’s part of it for me. (IP9)

Participants are also characterized by their different levels of risk perception. Some of them say that they do not belong to a risk group and therefore do not worry so much about infection. Others are more concerned but are more tempted to risk going to a restaurant again due to the falling infection rates. Still others see little risk of getting sick but want to protect their parents and grandparents and therefore pay more careful attention to the health measures.

You know people who were in the risk group. You don’t want to be the one to blame if they get sick. I would say, then I wouldn’t do it either, because then I would say, there is no protection. Then I really wouldn’t go out to eat, I would just do without it. (IP15)

5. Discussion and implications

The aim of this paper was to investigate consumers’ dining experiences and wellbeing perceptions while practicing social distancing at restaurants. We applied an exploratory qualitative research design to identify factors and dimensions that determine collective wellbeing in the restaurant industry in a COVID-19 era. Based on personal in-depths interviews, we developed a conceptual framework of collective wellbeing domains on macro-, meso-, and micro-levels that provides a holistic understanding of consumers’ wellbeing during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Undoubtedly, the COVID-19 pandemic has led to a major global humanitarian and economic crisis, creating a destructive impact on service industries. The hospitality industry, particularly, has been hit extremely hard by lockdown measures set in place to contain the virus. As restaurant owners now prepare for an uncertain and complicated reopening, they face new challenges—dealing with changing state and federal regulations, differences in guidance from one market to the next, varied cleaning and sanitizing requirements, and labor issues (Maze, 2020). Making things even more complicated, in some cases restaurant owners even decide to shut down again, as too many of their customers do not follow measures such as wearing masks that are required by government reopening plans (Flores, 2020). Furthermore, during the lockdown customers have become more accustomed to cooking at home and ordering online for delivery or pick-up. These behaviors will likely have some ‘stickiness’ in the post-pandemic world (Haas et al., 2020).

To entice customers back to on-premise dining, we propose a framework of collective wellbeing that consists of multiple domains of macro-, meso-, and micro- wellbeing. Prior research suggests that collective wellbeing reflects the sum of the wellbeing levels of individuals who belong to a certain community, or it considers wellbeing as something that resides in the community as a collectivity (White, 2010). This paper proposes that public health regulations and social distancing measures impact consumers’ dining experiences and their comfort/discomfort when among other diners. When people visit a restaurant during the COVID-19 era, these domains of wellbeing seem to be very important for the individual, and they influence not only the restaurant choice, but also the overall dining experience and the intention to revisit.

5.1. Theoretical implications

This study provides timely and valuable contributions to multiple literature streams, including wellbeing, service ecosystems, social distancing, hospitality environments and atmospheres, and the customer experience. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study that fuses social distancing with wellbeing and service ecosystems research.

First, we extend the growing body of COVID-19 related contributions to services research in general (see Special Issue of the Journal of Service Management in 2020 and 2021) and in connection with service ecosystems and wellbeing (Finsterwalder and Kuppelwieser, 2020; Tuzovic and Kabadayi, 2020). Second, we develop a framework of collective wellbeing domains and provide empirical evidence that overall wellbeing perceptions of individuals are shaped by different wellbeing domains at the macro (i.e. state/federal regulations), meso (service network, i.e. restaurant) and micro (individual actor) levels. We thus contribute to service-related wellbeing literature and, more specifically, to publications on collective wellbeing (e.g., Leo et al., 2019). Our results are aligned with the multidimensional conceptualization of individuals’ subjective wellbeing (Diener et al., 2018a). Furthermore, the findings provide strong support to show that wellbeing is not only sought collectively, but is also determined by consumers’ wellbeing perceptions of both themselves and others around them (Nelson and Prilleltensky, 2005). Furthermore, this study offers an important contribution to the TSR literature, as it confirms the importance of having a holistic view of wellbeing across different levels when such wellbeing is created by services.

Third, this research adds to hospitality-related publications on wellbeing. Previous studies in hospitality have focused primarily on employee wellbeing (e.g., Ponting, 2020; Walters and Raybould, 2007) or the influence of social interactions with other customers on the social wellbeing of elderly customers (Altinay et al., 2019). This paper extends that literature by providing a comprehensive framework that integrates social distancing measures with diner’s perceived space and perceptions of wellbeing. While the concept of social distancing has become a part of daily life all around the world, an understanding of how it affects consumers’ wellbeing perceptions of their dining experiences has been limited. However, such understanding is critical, as individuals’ wellbeing perceptions play a critical role in their restaurant patronage behavior. While recent conceptual research has theorized the impact of social distancing on employee wellbeing (Tuzovic and Kabadayi, 2020) and conceptualized actor distance in a pandemic (Finsterwalder, 2020), this study introduces the term of spatial wellbeing as a central aspect of diners’ wellbeing in a restaurant. We contribute to prior research in hospitality on physical distance between individuals in a dining setting (Hwang et al., 2018; Moon et al., 2020). Our results confirm the importance of physical environment and spatial arrangements for consumer emotions. However, we extend the current literature as most studies focused on solo dining. Our research offers insights not just for solo diners but more broadly in the context of group categorizations (in-group versus out-group) (Her and Seo, 2018). What was newly revealed by this research, however, was the influence of perceived isolation—in this case, resulting from there being fewer tables and thus fewer guests in the restaurant. Such conditions signal that things are not as before, thus potentially decreasing wellbeing perceptions.

Finally, our study provides empirical support about the important role of context factors. One the one hand, the results add to prior hospitality literature. For example, Moon et al. (2020) found that dining motivations (e.g., preference for convenience versus gastronomy) moderate the relationship between diners’ place attachment and perceived territoriality. Based on our qualitative data, we propose that dining motivations may be an important context factor for hospitality during the COVID-19 pandemic. On the other hand, the findings contribute to novel research on COVID-19 in psychology and medicine that has examined the role of sociodemographic and psychosocial variables. For example, older people adopted mitigating personal behavioral changes more than younger people as the pandemic progressed (Kim and Crimmins, 2020). And anxiety and fear of death lead to an increase of protective behaviors via higher perceived risk (Pasion et al., 2020). Our study expands this research and suggests that personal factors (e.g., age and risk perceptions) may be important context factors to understand wellbeing dimensions in hospitality.

5.2. Managerial implications

This research presents several important implications for the hospitality industry. Even as the rollout of vaccines has begun, restaurants around the world face an unpredictable environment with new sudden lockdown measures. Social distancing is expected to remain a key public health measure even beyond 2021 (Christ, 2020). This study provides a comprehensive framework to guide restaurant owners understand how different domains of wellbeing at the macro-, meso-, and micro-level influence customers’ perceptions of indoor dining in a COVID-19 era. Our findings confirm recent media coverage that reviews health practices in the restaurant industry (e.g., Taylor et al., 2020). We encourage restaurant owners to provide information in advance about how the restaurant is implementing the hygiene measures and what exactly is being done to ensure the wellbeing of the guests. It is also helpful to explain what behavior is expected from the guest and how the processes have been redesigned so that the guest can prepare for the changes in advance. This information can be posted on the homepage and in front of the restaurant. Measures such as hand disinfection, masks, distancing, and regular table cleaning should be done consciously in front of the guests. Guests want to see this, as it gives them a reassuring feeling.

Our study also emphasizes the role of employees in hospitality during the pandemic. Employees can exude positivity through their behavior and enhance the experience for guests. In times of COVID-19, employees can have a calming effect, and can diminish the uncertainty of the guests. We recommend that managers regularly train their service staff and remind them of their role model function. Employee behavior has an enormous impact on the wellbeing of guests, so employees should distract guests from the pandemic situation with their attentive behavior and show them a good time. Through their exemplary behavior (e.g., following the regulations), they give guests a sense of safety so that they enjoy a carefree time in the restaurant. Employees are also responsible for ensuring that all rules and policies are followed in the restaurant. They should also be empowered to enforce these rules with guests. This is for the protection of other guests and employees. We advise restaurant owners to retain responsible and assertive employees for the long-term.

Finally, the newly introduced term of spatial wellbeing can be perceived as a double-edged sword for restaurateurs. While social distancing is urgently needed in order to contain the pandemic, this requires increasing the space between the tables to give the guests a sense of security. But to avoid the negative impact on perceived atmosphere, the room layout and design should minimize the sense of isolation. Restauranteurs are urged to consider innovative decoration and an effective arrangement of the tables to provide “actor safe zones” (Finsterwalder, 2020). In doing so, guests have a feeling of comfort and intimacy, yet at the same time perceive sufficient distance from other people that they feel safe. In this way, guests can feel part of the community and be close to others, but also protect their own privacy and health.

In summary, our study offers restaurant owners a framework for adopting a holistic approach to their operations, as consumers consider various cues simultaneously in forming multiple domains of their wellbeing perceptions. Restaurant owners need to signal that they are not only aware of and are following the government’s public health regulations, but that they also have the resources needed to provide a physical environment that implements those mandates.

6. Limitations and future research

Despite the meaningful implications, this study has several limitations. First, due to the nature and design of this study, its findings cannot be generalized to other hospitality categories (e.g., bars, hotels) or other service industries. Second, the current study focused on restaurant diners in one single country. Given the continuously evolving environment of COVID-19 around the world with varied lockdown restrictions throughout the pandemic (e.g., in the UK or in California), consumers in other countries and regions may have different wellbeing perceptions. Third, the pandemic has created new challenges for conducting face-to-face interviews. Research that traditionally took place in person, mainly focus groups or interviews, are moved to a virtual setting which may affect the quality of the output (Remesh, 2020).

Yet the study provides an important body of information for the global restaurant industry, as many countries face similar business reopening conditions. Given the exploratory nature of this study, future quantitative research is needed to empirically investigate the relationship of social distancing measures to wellbeing and intentions to revisit. Furthermore, future research is needed in order to study different segments of diners (e.g., solo diners versus groups). For instance, the situational context may profoundly affect privacy needs (Robson et al., 2011). In addition, Her and Seo (2018) argue that crowding could be partly dependent on whether the tables are occupied by solo or group diners and that a comparison of solo and group dining occasions would contribute to a broadened understanding.

Footnotes

Please note: While one co-author conducted the coding process in German, different members of the author team translated the exemplary quotes back-to-back between German and English to ensure equivalency.

References

- Abu-Obeid N., Al-Homoud M. Sense of privacy and territoriality as a function of spatial layout in university public spaces. Arch. Sci. Rev. 2000;43(4):211–220. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed F., Zviedrite N., Uzicanin A. Effectiveness of workplace social distancing measures in reducing influenza transmission: a systematic review. BMC Public Health. 2018;18:518–531. doi: 10.1186/s12889-018-5446-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altinay L., Song H., Madanoglu M., Wang X.L. The influence of customer-to-customer interactions on elderly consumers’ satisfaction and social well-being. Int. J. Hosp. Manage. 2019;78:223–233. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson L., Ostrom L. Transformative service research: advancing our knowledge about service and wellbeing. J. Serv. Res. 2015;18(3):243–249. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson L., Ostrom A.L., Corus C., Fisk R.P., Gallan A.S., Giraldo M., Mende M., Mulder M., Rayburn S.W., Rosenbaum M.S., Shirahada K., Williams J.D. Transformative service research: an agenda for the future. J. Bus. Res. 2013;66(8):1203–1210. [Google Scholar]

- Attri R., Kushwaha P. Dimensions of customer perceived value in restaurants: an exploratory study. IUP J. Brand Manage. 2018;XV(2):61–79. [Google Scholar]

- Baccarani C., Cassia F. Evaluating the outcomes of service ecosystems: the interplay between ecosystem well-being and customer well-being. TQM J. 2017;29(6):834–846. [Google Scholar]

- Beirão G., Patrício L., Fisk R.P. Value cocreation in service ecosystems: investigating health care at the Micro, meso, and macro levels. J. Serv. Manage. 2017;28(2):227–429. [Google Scholar]

- Bitner M.J., Booms B.H., Mohr L.A. Critical service encounters: the employee’s view. J. Mark. 1994;58:95–106. [Google Scholar]

- Boddy C.R. Sample size for qualitative research. Qual. Mark. Res. Int. J. 2016;19(4):426–432. [Google Scholar]

- Braun V., Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006;3(2):77–101. [Google Scholar]

- Brüggen E.C., Hogreve J., Holmlund M., Kabadayi S., Löfgren M. Financial well-being: a conceptualization and research agenda. J. Bus. Res. 2017;79:276–294. [Google Scholar]

- Bruhn M., Schnebelen S., Schäfer D. Antecedents and consequences of the quality of e-customer-to-customer interactions in B2B brand communities. Ind. Mark. Manage. 2014;43(1):164–176. [Google Scholar]

- Byun S.-E., Mann M. The influence of others: the impact of perceived human crowding on perceived competition, emotions, and hedonic shopping value. Cloth. Text. Res. J. 2011;29(4):284–297. [Google Scholar]

- Cajander N., Reiman A. High performance work practices and well-being at restaurant work. Eur. J. Tour. Hosp. Recreat. 2019;9(1):38–48. [Google Scholar]

- CBRE . 2020. Viewpoint U.S. Retail. COVID-19 Implications for Reopening Restaurants.https://www.cbre.us/research-and-reports/US-Retail-ViewPoint----COVID-19-Implications-for-Reopening-Restaurants-May-2020 May. Available at: [Google Scholar]

- CDC . 2020. Social Distancing, Quarantine, and Isolation.https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/prevent-getting-sick/social-distancing.html Available at: [Google Scholar]

- Choi B.J., Kim H.S. The impact of outcome quality, interaction quality, and peer-to-peer quality on customer satisfaction with a hospital service. Manage. Serv. Qual. 2013;23(3):188–204. [Google Scholar]

- Christ C. 2020. Fauci: Masks, Social Distancing Likely Until 2022.https://www.webmd.com/lung/news/20201022/fauci-masks-social-distancing-likely-until-2022 WebMC, October 22. Available at: [Google Scholar]

- Daniel Z. ABC News. 2020. Australians may not be ready to go back to normal even if coronavirus restrictions are lifted, survey finds.https://www.abc.net.au/news/2020-05-06/australians-hesitant-to-head-out-coronavirus-restrictions-lifted/12217102 May 6. Available at: [Google Scholar]

- Denzin N.K., Lincoln Y.S. In: Strategies of Qualitative Inquiry. Denzin N.K., Lincoln Y.S., editors. Sage Publications; 2008. Introduction: the discipline and practice of qualitative research; pp. 1–43. [Google Scholar]

- Diener E., Ryan K. Subjective well-being: a general overview. S. Afr. J. Psychol. 2009;39(4):391–406. [Google Scholar]

- Diener E., Lucas R.E., Oishi S. Advances and open questions in the science of subjective well-being. Collabra Psychol. 2018;4(1):15–64. doi: 10.1525/collabra.115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diener E., Oishi S., Tay L. Advances in subjective well-being research. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2018;2(1):253–260. doi: 10.1038/s41562-018-0307-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixon V. 2020. By the Numbers: COVID-19’s Devastating Effect on the Restaurant Industry.https://www.eater.com/2020/3/24/21184301/restaurant-industry-data-impact-covid-19-coronavirus Eater.com, March 24. Available at: [Google Scholar]

- ECDC (European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control) 2020. Considerations Relating to Social Distancing Measures in Response to COVID-19 – Second Update. Technical Report. 23 March, Stockholm. [Google Scholar]

- Eroglu S.A., Machleit K., Barr T.F. Perceived retail crowding and shopping satisfaction: the role of shopping values. J. Bus. Res. 2005;58(8):1146–1153. [Google Scholar]

- Evans S.D., Prilleltensky I. Youth and democracy: participation for personal, relational, and collective well-being. J. Commun. Psychol. 2007;35(6):681–692. [Google Scholar]

- Finsterwalder J. Social distancing and wellbeing: conceptualizing actor distance and actor safe zone for pandemics. Serv. Ind. J. 2020;(November):1–23. doi: 10.1080/02642069.2020.1841753. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Finsterwalder J., Kuppelwieser V.G. Equilibrating resources and challenges during crises: a framework for service ecosystem wellbeing. J. Serv. Manage. 2020 doi: 10.1108/JOSM-06-2020-0201. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Flores J. USA Today. 2020. ‘A mask is not a symbol’: restaurants take a stand amid coronavirus pandemic.https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/nation/2020/06/30/face-masks-required-restaurants-coronavirus/3283156001/ June 30. Available at: [Google Scholar]

- Ford M.B. Social distancing during the COVID-19 pandemic as a predictor of daily psychological, social, and health-related outcomes. J. Gen. Psychol. 2020 doi: 10.1080/00221309.2020.1860890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallan A.S., McColl-Kennedy J.R., Barakshina T., Figueiredo B., Jefferies J.G., Gollnhofer J., Hibbert S., Luca N., Roy S., Spanjol J. Transforming community well-being through patients’ lived experiences. J. Bus. Res. 2019;100(July):376–391. [Google Scholar]

- Grewal D., Baker J., Levy M., Voss G.B. The effects of wait expectations and store atmosphere evaluations on patronage intentions in service-intensive retail stores. J. Retail. 2003;79(4):259–268. [Google Scholar]

- Haas S., Kuehl E., Moran J.R., Venkataraman K. McKinsey & Company; 2020. How Restaurants Can Thrive in the Next Normal.https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/retail/our-insights/how-restaurants-can-thrive-in-the-next-normal May. Available at: [Google Scholar]

- Her E., Seo S. Why not eat alone? The effect of other consumers on solo dining intentions and the mechanism. Int. J. Hosp. Manage. 2018;70:16–24. [Google Scholar]

- Hirsch C. Politico; 2020. Europe’s Coronavirus Lockdown Measures Compared.https://www.politico.eu/article/europes-coronavirus-lockdown-measures-compared/ March 31. Available at: [Google Scholar]

- Hirsch C. Politico; 2020. Europe’s Post-Lockdown Rules Compared.https://www.politico.eu/article/europe-coronavirus-post-lockdown-rules-compared-face-mask-travel/ June 21. Available at: [Google Scholar]