Abstract

The restaurant industry is one of the most affected businesses during the outbreak of COVID-19. The customer choice regarding whether or not to dine in a restaurant have changed due to this unprecedented global pandemic. Integrated with the affective decision-making framework, meta-theoretic model of motivation (3M), and optimistic bias theory, this conceptual paper proposes a theoretical scheme for understanding constructs that affect consumer motivation while considering the significance of consumers’ risk perceptions of the novel coronavirus disease. This research aims to delineate the role of loyalty, trust, and transparency on resuming in-restaurant dining during and after the pandemic. By identifying the link between each construct and addressing the unparalleled food-/health related risks, this study suggests that restaurants who accumulated more customer trust by fostering transparency are likely to have more business and quickly recover from the shock.

Keyword: Restaurant industry, Trust, Transparency, Risk, Health, COVID-19

1. Introduction

COVID-19, a disease caused by a novel strain of coronavirus from SARS species, changed the world unexpectedly because of its contagious nature, difficulty to control, and limited treatment options (Gibbs and Mirsky, 2020). The United States restaurant industry, as one of the most affected businesses during this pandemic, has incurred severe shocks to its system due mass quarantine in order to attempt to slow the spread of the disease (Ozili and Arun, 2020). Noticing COVID-19’s devastating effect on the restaurant business, both industry practitioners and researchers are now eager to find ways to help restaurants overcome the hardship and recover in and after the COVID-19 era, specifically related to managing the “post COVID-19” customer.

The massive disruption wrought by COVID-19 has left an ineffaceable mark on customers (Coibion et al., 2020). Indeed, the customers that the restaurant industry knew just three months ago are not the same people today. Normal preferences have shifted as customers’ exercise caution – about where, what and how they make their purchases. The impact on retailers and customer goods companies is, and will continue to be, tremendous (Jain, 2020). Although we still know comparatively little about the COVID-19 virus and its long-term implications, one thing that is clear is that it has already fundamentally changed the way people around the world think and act.

When the virus first started to circulate, the shift in customer preference was substantial (Zwanka and Buff, 2020). Almost overnight, physical stores were shunned. Customer demand shifted from discretionary items to those perceived as essentials. Individuals started to prioritize health and supply chain safety over cost and convenience.

In response to this clear customer shift to a “new” type of customer, the present study aims to provide new insight on the importance of understanding the roles that loyalty, trust and transparency play on customers’ motivation to resume in-restaurant dining during the pandemic, through the lens of affective decision making and optimistic bias (Bracha and Brown, 2012; 2007). Specifically, this conceptual paper forwards a theoretical framework for understanding the constructs affect customer motivation while considering risk perceptions of dining out during COVID-19. Risk perception is the subjective judgement that people evaluate the severity of a risk (Bond and Nolan, 2011). In this study, risk perception stands for the extent that individual subjectively assessed the risks of dining in restaurant during a pandemic. By understanding the customer first, this study may then help guide the restaurant industry in order to address demand issues and help the industry more quickly recover from the shocks.

Past researchers have conducted studies that explored what influences people’s risk perceptions of food safety and how such psychological interpretations will affect customers’ attitudes and purchasing behaviors (Bai et al., 2019; Knight et al., 2007; Yeung et al., 2010). However, limited research has been done on motivation and risk during a pandemic. This is an important issue because the very core of why people are or are not dining at restaurants has changed due to the effect of COVID-19.

When dining at a restaurant, customers often have their own assessments of sanitation and the perceived risks of safety (Lee et al., 2012). Prior studies showed that although safety should be a critical factor when people dine out, most customers do not even think of it when they choose a restaurant (Aksoydan, 2007; Ungku Fatimah et al., 2011). Instead of considering safety, customers are often more concerned about some visible elements such as the dining environment’s food options, atmosphere and cleanliness (Barber and Scarcelli, 2009). As a result of COVID-19, safety is becoming a top concern and therefore customer motivations for dining out must be compelling for an individual to take on the risk.

According to Pressman et al. (2020), COVID-19 is a respiratory illness that invades the respiratory tract and is spread through human contact and surfaces, which can cause customers to worry about contracting the virus in places like restaurants. Due to the continuous chaos and panic caused by COVID-19, individuals may develop a dramatically heightened sense of safety precautions when they go to a restaurant. Additionally, this novel coronavirus may possibly be transmitted via food surfaces, food processing and food handling stages (Pressman et al., 2020), and so customers may have an increasing desire to know where the food came from, how it was raised, grown, processed, and how the restaurant handled the food in addition to procedures in place at the restaurant to prevent human spread.

The attention on customers’ perceptions and understandings of safety risk related to restaurant dining and general consumption of food can date back to a half-century ago. Some of the most notable cases were the bacterial outbreaks of bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE) in the UK (Smith and Bradley, 2003), and the Jack in the Box restaurant company E. coli outbreak in the US (Golan et al., 2004). Food safety has always been a major issue of public concern when similar health-related cases happened because that was the time when people lost their faith in food and food providers (Yeung and Morris, 2001). For example, the UK BSE crisis caused some people to believe that the British government were somewhat responsible for the outbreak because they hid information from the public, while others believed that the “Mad cow” disease was purely a media creation (Keane and Willets, 1996). The two groups hold different viewpoints on how severe the disease was. Therefore, it can be stated that risk perceptions in this area may be polarizing.

Although time has passed by nearly half a century, the spread of COVID-19 still shares some similarities with the BSE incident. Some people think that the current epidemic is overestimated by mass panic and exaggeration of media (e.g., Fichera, 2020). This group of people should have lower perceptions of risk towards safety compared to those who believe the disease is fatal. By acknowledging customer risk perceptions during this extraordinary time, the present study aims to apply affective decision making, individual differences theory, Meta-theoretic model of motivation (3 M theory) and optimism bias theory to understand the customer and their motivations of dining in restaurants during and post pandemic in order to enrich existing customer behavior literature.

1.1. Conceptual methodology

This study is conceptual in nature, therefore its purpose focuses on proposing new relationships among the presented constructs and viewing the relationship through a different lens. Thus, the paper focuses on the development of logical and complete arguments (Gilson and Goldberg, 2015) regarding the associations between the constructs of risk and optimal bias on customer motivation for dining out during a pandemic, coupled with loyalty, trust and transparency rather than testing the constructs empirically.

This paper uses existing literature to explain how and why the theories and concepts on which it is grounded were selected and how they were applied. Specifically, we used method theories and deductive reasoning to explain relationships between the key constructs, facilitated by theories in use (MacInnis, 2011). Further, this research describes a focal phenomenon that is observable but not adequately addressed in the existing research: that the current pandemic requires risk-based evaluation of dining out, and that the decision process is based in part on motivational factors, personality, trust, loyalty and transparency. The choice to “dine out” and the research in this area has usually been rooted in understanding restaurant attributes, pricing, and experience as a motivator (Kim et al., 2018). Now, the choice involves a first and primary layer of risk perception regarding health and safety. Therefore, this study looks at constructs that shape the individual motivation to dine out given the current environment of a pandemic and suggest that intrinsic motivational factors in addition to trust, loyalty and transparency play an important role in managing the risk based decision. Theses constructs are presented in the form of a model, which intends to summarize the arguments in the form of a figure that depicts the salient constructs and their relationships, and provides a set of formal propositions that are logical statements derived from the conceptual framework (Meredith, 1993).

The choice of model concepts was based on their fit to the focal phenomenon and the complementary value in conceptualizing it. In selecting these particular concepts and theories, we de facto make an argument about the conceptual components of the empirical phenomenon in question (Payne et al., 2017; Cornelissen, 2017). This argument is derived from the assimilation and combination of evidence in the form of previously developed concepts and theories (Hirschheim, 2008) rather than empirical data in the traditional sense. Thus, we build on previously developed concepts that may then be tested through empirical research.

2. Literature review

2.1. Affective decision making

Prior researchers have found that people’s risk perceptions towards safety issues required an integrated understanding of subjective perceptions as well as more extensive cultural and social backgrounds (Frewer et al., 1996; Knox, 2000). Individuals’ recognitions of safety risks may sometimes be “optimistically biased” and easily affected by media (Frewer et al., 1996). Given the current spread of the global pandemic, a large population have stayed in an environment that is full of risks and unpredictability. Thus, investigating the underlying mechanism of customer behaviors under risks and uncertainty becomes a valuable and timely topic.

Previous research indicated that people tend to be optimistically biased when assessing probabilities (Slovic et al., 2004; Weinstein, 1989). Particularly, they are more likely to overestimate the favorable future and underestimate the unfavorable future. Based on this theory, Bracha and Brown (2007) proposed an innovative decision-making model that called affective decision-making model (ADM). ADM is a behavioral theory of choice that explains how individuals select activities under risks. It demonstrates two distinct psychological processes that mutually determine people’s choice: the rational process and the emotional process, in which the rational process determines what action will be performed, and emotional process shapes people’s beliefs (Bracha and Brown, 2012). Put differently, the formulation of a decision need two different simultaneously interactive processes: one choses action (rational) and the other forms perceptions (emotional).

ADM can provide great insights to understand customer behavior under the current global pandemic. Individuals use the rational process to perform actions that can maximize their expected utility of dining in a restaurant. Expected utility is an economic term which explains people’s tolerance of risks (Schoemaker, 2013). In the context of this study, it means the accumulation of all the positive emotions people perceived dining in the restaurant (e.g., satisfaction and excitement) and all the negative emotions they perceive that result from the likelihood of being infected (e.g., anxiety and uncertainty). When the accumulation becomes the largest, the expected utility of dining in restaurant is the maximum, and the goal of rational process is achieved.

In addition to rational process, based on ADM, emotional process also plays an important role in decision-making. Emotional process influence individual’s behaviors under risk condition by selecting an optimal risk perception that balances two contradictory impulses— affective motivation and taste for accuracy (Bracha and Brown, 2012). During the outbreak of COVID-19, the risks of dining in restaurants are perceived very high due to the fact that the novel coronavirus may possibly be transmitted via other customers, food surfaces, food processing, and during various food handling stages (Pressman et al., 2020). In the emotional process, although the affective motivation (people’s desire to hold a favorable risk perception) may still drive customers to dine out, the taste for accuracy may be considered as a “mental cost” that leads individuals to re-consider their decision. Specifically, compared to any other time, customers now may have a higher desire for accuracy (i.e., accurate restaurant sanitation information and accurate COVID-19 control and prevention information) to minimize their mental cost and enhance the sentimental confidence of their favorable risk beliefs.

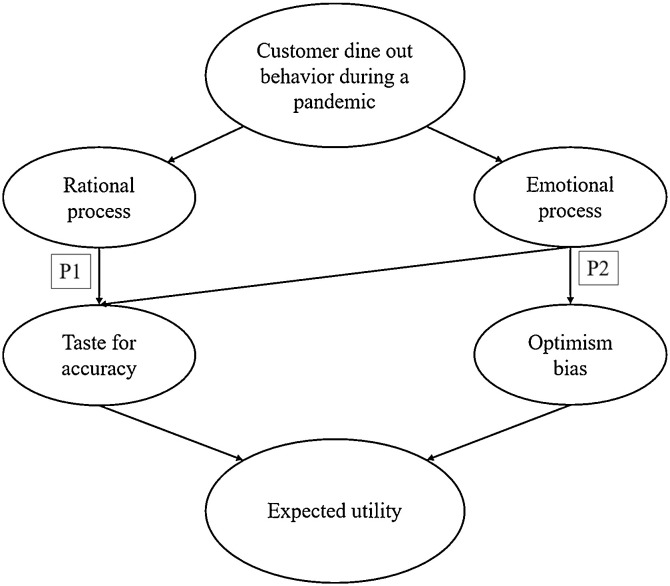

Taken together, affective decision-making model that compromising rational and emotional processes mutually act on customers’ choice to dine out during a pandemic. The conceptual framework is presented in Fig. 1 , and the following propositions are summarized based on the model:

Fig. 1.

Affective decision model applied to customer dine out behavior during a pandemic.

P1: The choice to dine out during a pandemic may be a rational process mediated by a desire for accurate information in order to achieve the expected utility.

P2: The choice to dine out during a pandemic may be an emotional process that is mediated by an optimistic belief (bias) that the risk is mitigated by various measures in order to achieve the expected utility.

2.2. Individual differences approach and the meta-theoretic model of motivation

Complementing the affective decision-making framework, the individual differences approach and the meta-theoretic model of motivation must also be considered in order to understand the customer and their behavior/motivations. The individual differences approach contends that individuals differ in their behavior and personal qualities (e.g., personality, gender, etc.) so that not everyone can be considered “the average person” (McAdams, 1995; McAdams and Pals, 2006; Neel et al., 2016). This specifically relates to “disposition” where behavior is caused an individual, rather than the situation. Every individual is genetically unique, and this uniqueness is displayed through their behavior, so everyone behaves differently. More specifically, the individual differences approach suggests that all psychological characteristics are inherited, and since everyone inherits different characteristics, everyone is different and unique (Emmons, 1989).

Researchers of individual differences found that personality accounts for more variance in customers' behavior than customer researchers initially have recognized. Thus, a new model of motivation, called the 3 M (which stands for “Meta-theoretic Model of Motivation”) was developed by Mowen (2000). This theory seeks to account for how personality traits interact with the situation to influence customer attitudes and actions. The 3 M model is regarded as a coherent general theory of motivation and personality that is able to parsimoniously illustrate a broad set of phenomena related to risks (Mowen, 2000; Schneider and Vogt, 2012). Previous research proposes that multiple personality traits combine to form a motivational network that acts to influence behavior so that in order to understand the causes of enduring behavioral tendencies, one must identify the more abstract traits underlying surface behaviors (Mowen, 2000).

The 3 M model is hierarchical, and identifies four types of personality traits: elemental, compound, situational, and surface traits. Eight elemental traits are proposed to form the underlying dimensions of personality, and are comprised of the following: openness to experience, conscientiousness, extraversion, agreeability, neuroticism/stability, material needs, arousal needs, and physical needs (Mowen, 2000, p. 47). Elemental traits can be considered as either control variables or as antecedents of people’s surface traits (Schneider and Vogt, 2012). In the COVID-19 pandemic, people’s elemental traits have been examined to be associated with their coping strategies with the unexpected risks and their compliance with restrictions. For example, Zajenkowski et al. (2020) revealed that people who have a higher degree of agreeableness were more likely to comply with the enforced restrictions geared to reducing the spread of the novel virus. Additionally, both conscientiousness and neuroticism are positively associated with people’s behavior in adopting social distancing to reduce the risk of COVID-19 infection (Abdelrahman, 2020).

Research reveals that the elemental traits are fundamental and set the stage for compound traits and situational influences to cause enduring behavioral tendencies within general situational contexts (Mowen, 2000). Examples of situational traits previously investigated include impulsive buying, value consciousness, sports interest, and health motivation. This study suggests a model of certain elemental traits that impact the situational trait of dining out during a pandemic. By presenting a new meta-theory of motivation and personality that is testable, Mowen's (2000) 3 M model may account for high levels of variance in customer behavior when considering dining out during a pandemic. By integrating the work of selected past and current theorists into a comprehensible whole, the 3 M model additionally provides coherence in a field currently dominated by conflicting ideas, theories, and approaches. These studies on 3 M provide evidence that by understanding the individual dispositions (elemental traits) that underlie customer behavior, restaurant operators and marketing specialists can develop better communication and transparency programs to influence and persuade their target audiences during the global pandemic.

Literature supports the development of several key ideas in this area. First, agreeable individuals often care about each other and are generally prosocial in nature (Wilkowski et al., 2006). Therefore, those who are agreeable may comply with suggested rules of social distancing and may avoid spaces with many people because doing so protects others. Hence, the personality trait agreeability may be negatively associated with customer motivation to dine out during a pandemic.

Second, conscientious people try to avoid germs and live an organized life (McCrae and Costa, 2008). The COVID-19 pandemic may elicit more compliance in those with this personality trait with the purpose of reducing the opportunity for infection. Additionally, the study of personality behavior demonstrates that conscientious people typically visit a relatively small number of places during a day, and thus a restriction such as isolation might be not so disturbing for them (Ai et al., 2019). Therefore, it can be stated that these individuals may stay away from dining establishments during this time. Hence, it can be stated that the personality trait of conscientiousness may be negatively associated with customer motivation to dine out during a pandemic.

Third, neuroticism is a trait that may capture people's tendency to avoid risk (Jonason and Sherman, 2020) which may lead neurotic people to comply with policies that might increase their (sense of) safety, such as choosing to stay home and not dine at a restaurant. Therefore, it can be stated that the personality trait of neuroticism/stability might be negatively associated with customer motivation to dine out during a pandemic.

Finally, on the contrary, extraverted individuals tend to visit more places during a day, and so isolation might be especially difficult for them. These individuals may more likely choose to dine out at a restaurant during a pandemic. Conversely, an introverted individual may be happy to skip dining at a restaurant during the current environment. Based on this review, the personality trait extraversion (introversion) may be positively (negatively) associated with customer motivation to dine out during a pandemic.

2.3. 3M motivation model and constructs of loyalty and trust

As mentioned above, researchers have concluded that the enduring disposition of customer personality/elemental traits are important in predicting customer behavior within many types of service industries (Fang and Mowen, 2009; Kim et al., 2010; Lin, 2010). For example, Fang and Mowen (2009) contextualized the 3 M model in a gambling setting and used the four different trait levels to identify a set of functional motive antecedents in predicting gambling activities. In a restaurant context, the 3 M model suggests other factors that impact customer behavior should be considered in addition to personality traits. For example, customers’ willingness to patronize and pay are mostly impacted by customer loyalty and trust related to the restaurant (Kim et al., 2006).

Researchers indicate that this area should receive more attention regarding its significance in both industry practices and theoretical studies (Lin, 2010). Therefore, in this study, we explore the importance of loyalty to explain restaurant customer decisions to dine at a restaurant during the COVID-19 pandemic.

2.3.1. Loyalty

Based on Oliver’s (1999) definition, loyalty is a deep commitment that customers are willing to repurchase and recommend preferred product/service in the future, consisting with cognitive, affective, conative, and action loyalty phases. Consistent of Oliver’s (1999) explanation, researchers also found that loyalty is an influential factor in firms’ continued success (Kim et al., 2008). Loyal customers are always the most valuable treasure of a company, particularly during the current ongoing pandemic.

Building upon Fang and Mowen (2009) explanations, Smith (2012) further synthesized the 3 M model and listed some examples for each trait level related to loyalty. Smith’s (2012) work is relevant to the context of this study, as it contends that the prominence of loyalty is a crucial personality construct relevant to motivation. Smith details the elemental traits such as agreeableness, conscientiousness, neuroticism/stability, extraversion/introversion; compound traits such as competitiveness and impulsiveness; situational traits that contain the desire to be healthy or desire for friendship; and the surface traits such as the desire to have a healthy diet.

Findings of the mentioned personality traits that link loyalty to customer behaviors, have been generally supported by other literature (Alwi, 2009; Ferguson et al., 2010; Kandampully et al., 2015). By integrating motivation and personality perceptions during the COVID-19 pandemic, this study suggests that customer behavior regarding dining out during a pandemic is first driven by certain existing motivations and personalities and then further mediated by loyalty, which may have an impact on the motivation to dine out during a pandemic.

Specifically, Lin (2010) and Smith (2012) found that agreeableness and openness have a significantly positive relationship with loyalty. People who are agreeable tend to be more empathetic, considerate, and generous. Thus, they would be more likely to build up an affective connection to a firm and be more loyal (Alwi, 2009; Smith, 2012), choosing to support a restaurant by dining out. Therefore, proposition 3 suggests:

P3: Agreeability is positively related to the moderating constructs loyalty and trust, and may increase customer motivation to dine out during a pandemic.

Additionally, prior studies recognized that introversion or less openness is negatively related to loyalty (Lin, 2010). One primary reason is that introverted people tend to pragmatically evaluate options and therefore reduce their likelihood of blind loyalty (Smith, 2012). Because introverted customers have more of an ability to make objective decisions towards perceived risks, they are less likely to be influenced by mass media or collective consciousness (Vollrath and Torgersen, 2002; Wang et al., 2016). Thus, considering the effects of COVID-19, they might be less loyal than extroverted customers, and in turn, choose to refrain from dining out at restaurants during the pandemic. This is summarized by proposition 4:

P4: Introversion is negatively related to the moderating constructs loyalty and trust, and may decrease customer motivation to dine out during a pandemic.

Conversely, as mentioned earlier, extroverted customers are used to interacting with many individuals and may be more inclined to be motivated to dine out at a restaurant during the pandemic. Further, extroverted customers may utilize loyalty and trust as a primary reason for continuing to dine out during a pandemic. Hence, proposition 5 suggests:

P5: Extraversion is positively related to the moderating constructs loyalty and trust, and may increase customer motivation to dine out during a pandemic.

Further, as mentioned previously, the conscientious personality trait has been shown to be one of the healthiest personality traits because these individuals are “rule followers”, dependable and driven, and tend to engage in fewer high risk behaviors (Al-Hawari, 2015). When the construct of loyalty is considered, it is proposed that loyalty doesn’t influence motivation to dine out; rather the “rule follower” would prevail and not assume additional risk and dine out during a pandemic. Therefore, proposition 6 suggests:

P6: Conscientiousness is not influenced by the moderating constructs loyalty and trust, and is negatively related to customer motivation to dine out during a pandemic.

The personality trait neuroticism/stability has been shown to be associated with a desire to minimize risk, as previously noted. Additionally, previous research has found that risk perception can influence the effect of brand loyalty on customers’ willingness to pay (Turhan, 2014). Oliver (1999) has also demonstrated that loyal customers have a higher degree of commitment towards company and brand. However, it is not believed that loyalty could influence the neurotic personality to assume additional risk (Li et al., 2020). Therefore, it is proposed in proposition 7 that:

P7: Neuroticism/stability is not influenced by the moderating constructs loyalty and trust, and is negatively related to customer motivation to dine out during a pandemic.

Further, in the context of this study, risk perception is defined as a factor that influences how people make decisions and behave (Li et al., 2020). According to previous research, risk perception indirectly influences customer behavior through factors such as attitude, beliefs, and trust (Heikkilä et al., 2013; Zepeda et al., 2003). Therefore, risk perception of the coronavirus should also be considered as an additional construct affecting loyalty and trust. P8 summarizes this formally:

P8: Different personality traits may provide different degrees of risk perception, which in turn may affect loyalty, trust and the customer motivation to dine out during a pandemic.

2.3.2. Trust

Trust requires a more comprehensive and long-term appraisal of the relationship between customers and service providers (Selnes, 1998). Similar to loyalty, trust has a predominately significant relationship with the personality traits (Anderson, 2010; Hiraishi et al., 2008; Tehrani and Yamini, 2020). For example, according to a recent study conducted by Freitag and Bauer (2016), the impact of personality traits, specifically agreeableness, on trust in strangers is stronger than that of trust in friends. Stated another way, the more agreeable an individual, the more trust may be built with strangers compared to friends. When applied to the state of the restaurant industry, agreeableness and extroversion may have important implications in helping restaurants building trust with customers during and post pandemic. To put it plainly, we know that customers will put their dollars and personal safety into the hands of restaurants they trust as shown in proposition 3 and 5.

Given the outbreak of COVID-19, people’s willingness to dine out has been lower than ever before (Gursoy and Chi, 2020). Since trust is such a critical and high-level construct in building customer relationships (Macintosh, 2007; Parasuraman et al., 1985; Rauyruen and Miller, 2007) and predicting loyalty (Arnott et al., 2007; Bowen and Shoemaker, 2003; Rashid et al., 2011), it may still well function in estimating motivation, even under the current circumstances as customers’ needs are changing. Also, because customers perceive more food- or health-related risks during the pandemic than any other time (Dryhurst et al., 2020), they may naturally reduce their trust of other people and places that may expose them to other people in order to protect themselves. Coleman (1990) and Hardin (2002) demonstrated that a person’s trust is grounded in experiences of trustworthiness in social interaction. Since the COVID-19 disrupted the social environment, the foundation of people’s trust was collapsed, and this directly applies to the restaurant industry.

Two major dimensions of trust are “competence” and “honesty”, in which “competence” refers to the communicators’ expertise, and “honesty” refers to the degree of truthful information that is conveyed to the public (Jungermann et al., 1996). When people have very extreme attitudes towards an event such as a pandemic crisis, trust is not as influential as distrust. In fact, studies found that people tend to distrust information sources that do not carry the same opinions and therefore distrust all further information disseminated by the source (Frewer et al., 1998). When people do not have strong feelings towards an issue, persuasive language, personal relevant information, and trust of the information source will strengthen their attitude and opinion (Frewer and Miles, 2003). Still, both trust or distrust and the source of communicated information was found to be very important for customer risk perception (Frewer et al., 1998).

2.4. Optimism bias theory

Risk perception is further influenced by optimism bias – which also effects information source perception since some individuals may perceive that they are at lower risk than others from a particular hazard.

Therefore, given the fact that faithful customers and restaurant have a “special tie”, based on the ADM, it is reasonable to argue that some customers are more likely to overestimate the favorable outcomes of dining out. In other words, they may have higher optimistic bias towards dine in behavior compared to regular customers. Finally, higher optimistic bias can increase their expected utility in the restaurant, as shown in Fig. 1.

While decision making is both emotional and rational, researchers have also found that the human brain may be too optimistic for its own good (Bortolotti, 2018). Weinstein (1989) proposed that the optimistic forecasts of risks are “actively constructed, rather than arising from simple mental errors” (p. 1232), which indicated that such overestimated optimism could be intervened by outside forces. For example, when asked the likelihood of experiencing a negative or traumatic event, most individuals would underestimate the probability of the event on their life (Bortolotti, 2018). This phenomenon is referred to as the “illusion of invulnerability” or “unrealistic optimism”. The bias can lead to poor decision making, which can have devastating results.

The phenomenon can be extended to the COVID-19 crisis, because infrequent events are more likely to be influenced by optimism bias then frequent events (Shepperd et al., 2013). People tend to think that they are less likely to be affected by things like extreme illness, hurricanes and tornados simply because these are generally not everyday events. In the case of COVID-19, customers may inherently believe that they are immune to the virus or very low risk of contracting the virus. Various causes may lead to this optimism bias, including cognitive and motivational factors; and optimism bias may then influence customer motivation. When customers are evaluating their own risks (e.g., food safety risks), they often compare their own situation to that of other people, but they are also egocentric (Rossi et al., 2017). The tendency to be over-optimistic when facing risks, in which the optimistic biases may severely hinder people from properly reducing dangerous behaviors (Johnson and Covello, 1987), may certainly impact customer’s decision to dine at restaurants.

Previous research has explored this over-positive bias from the food providers’ perspective (Da Cunha et al., 2014; Heger and Papageorge, 2018). For example, Da Cunha et al. (2014) conducted a study and examined 176 food handlers’ optimistic bias regarding foodborne disease in Brazil. The results suggested that most food providers believe that they are better than other competitors in handling foodborne disease and protecting customers. Recently, similar studies from the food customers’ perspective have also been addressed (de Andrade et al., 2019d; Kim et al., 2018). For instance, de Andrade et al. (2019) performed a quantitative study by evaluating 265 restaurant customers’ risk perception degrees. They found that optimism bias may lead people to choose places with a higher foodborne disease risk since it is hard for them to make judgement of restaurants’ food safety based on prior feelings, familiarity, and social identity. This suggests the impact that optimism bias may have on risk assessment and hence the effect should be considered when evaluating the “new” type of customer in a pandemic setting. Further, this all suggests that optimism bias may promote or increase loyalty and trust that customers already feel towards a particular place, echoing beliefs such as “my favorite restaurant won’t have a problem”.

Although it has almost devastated the restaurant industry, COVID-19 still provides potential opportunities for the restaurant industry to tackle the “post-COVID-19” customers, in which restaurants who seize the focal guests are likely to stand out and occupy certain market share. Based on optimism bias research, restaurants are encouraged to attract customers by facilitating this mental preference and providing more transparency in order to gain customers. However, such a favorable tendency to lower the risks of dining out may be a double-edged sword. Once customers perceive any infection risk during the service, they may over-react due to a self-protective behavior triggered under an epidemic outbreak and generate “unrealistic pessimism” of vulnerability (Chuo, 2014). Such negative emotions might reversely affect restaurant businesses and interrupt shock recovery.

2.5. Transparency impact on customer motivation

Due to the sudden outbreak of COVID-19 and the contagious nature of this virus, restaurant customers may abruptly change from multiple demands (e.g., tasty food, beautiful atmosphere, and good service, etc.) to a single primary demand — safety. Customers are in dire need of perceiving a sense of certainty over potential health risks (i.e., that risk of disease contraction is mitigated) when they decide to dine out at this moment. Therefore, restaurant management should respond to customers’ emerging need for trust and loyalty while managing risk in order to maximize and capture the appropriately motivated customer. The best way to respond to the call for trust and loyalty is to be transparent.

Transparency, defined initially as “visibility of and accessibility of information, especially concerning business practices” (Merriam-Webster, 2010), might help restaurants go through this crisis. According to its definition, transparency indicates the purpose of making the whole system visible based on customer demands (Karsenty and Botherel, 2005). Therefore, combining Ryu et al.’s (2012) research on restaurant service quality, this study suggests that restaurant transparency may be achieved by focusing on the physical environment, service process, and quality of food, theorizing that the more easily customers see the food-preparing and -delivering process, the higher transparency they would perceive.

Previous studies revealed that transparency could reduce customers’ information asymmetry and perceived risks by providing details of products and service processes (Hustvedt and Bernard, 2010). Restaurant news and reports have also mentioned that transparency is a valuable, trending, and less costly way to enhance customer loyalty (Label Insight, 2016; Tuttle, 2012; UCL, 2015). Although the restaurant industry has acknowledged the value of transparency, limited systematic academic articles have focused on this topic, with only a few exceptions (Agrawal and Mittal, 2019). Based on Parasuraman, Zeithaml, and Berry’s (1988) SERVQUAL model, transparency factors in restaurant business were found as a significant predictor of service assurance and reliability (Agrawal and Mittal, 2019). Such a sense of assurance and reliability further influenced customer loyalty, and thus, transparency was viewed as a weapon to foster restaurant competitiveness in the dynamic situation. Additionally, zero academic articles have reviewed transparency’s role in customer motivation to dine out during a crisis/pandemic. Therefore, this study conceptualizes transparency as an important construct that may increase customer motivation to dine out during a pandemic, as proposed in proposition 9:

P9: Transparency may reduce customer risk perception and increase trust, loyalty and motivation to dine out during a pandemic.

2.6. Forwarding a theoretical model of customer motivation in a pandemic

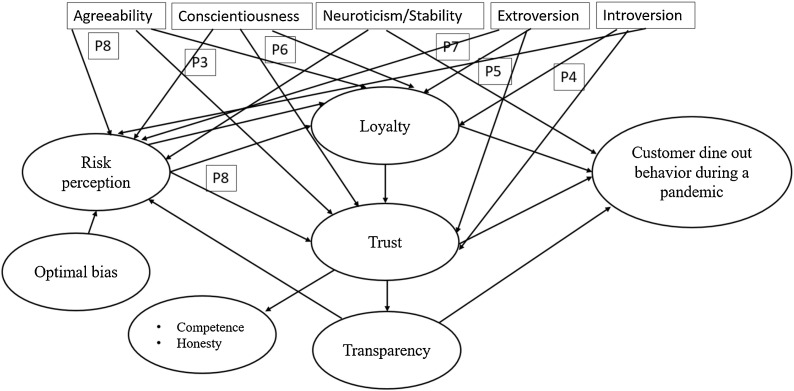

The purpose of this conceptual paper is to suggest a new theoretical model to explain customer motivation when considering dining out in a restaurant during the COVID-19 pandemic. A review of literature suggests that decision making is based on both emotional and rational process driven by desired accuracy and optimism (Fedoroff et al., 1997; Li et al., 2014; Oatley and Johnson-Laird, 1987; Slovic et al., 2004). A deeper dive into the process then suggests that motivation is affected by certain elemental personality traits that help an individual to more easily trust and express loyalty towards a decision to dine at a restaurant during a pandemic. This new model also credits transparency as a key construct affecting motivation to dine out. The model of these relationships is presented in Fig. 2 below:

Fig. 2.

New proposed conceptual model of constructs affecting the decision to dine out during a pandemic.

This new conceptual model suggests first that optimal bias and risk perception are central tenets of customer motivation during a pandemic because it initially shapes the decision process. Through this lens, individuals are then influenced through different psychological traits such as extraversion, introversion, neuroticism/stability, agreeableness and conscientiousness, which moderate the dine out decision through constructs loyalty and trust. This suggests that bias, risk and personality contribute to trust and loyalty towards a restaurant brand (Frewer, 2000) which influence the decision.

3. Discussion

The current study proposes a new conceptual model for evaluating customer motivation for dining out during a pandemic. When a catastrophic event like a global pandemic occurs, people are very possibly affected first by risk perception in addition to optimism bias, meaning that they may unlikely tolerate any risk if they do not perceive the benefits of hazard exposure (Frewer et al., 1998), but they may also consider their own risk to be low. Given this paradox of emotional and rational reasoning (as mentioned in propositions 1 and 2), this study suggests that factors of transparency, trust and loyalty should be considered as primary moderating constructs when evaluating customer’s motivation to dine out in restaurants during the time of a pandemic.

It is anticipated that restaurants who accumulate more customer trust are likely to have more business during and after the COVID-19 pandemic, thereby overcoming and recovering more quickly from the pandemic. Thus, many restaurants should prioritize how to establish trust relationships with customers during the current hardship. The importance of trust and loyalty may take precedence over any type of personality or elemental trait. For example, the propositions presented in Fig. 2 suggest that elemental traits by themselves have negative effects on the customer motivation to dine out during a pandemic. However, if a restaurant is able to strengthen the bonds of loyalty, trust and transparency, they may overcome the elemental personality conditions and capitalize on trust to gain the customer base. Therefore, the main contribution of this study is the recognition of the power of the constructs of loyalty and trust on customer motivation to dine out during a pandemic.

As mentioned earlier, the needs of restaurant customers in the pre-COVID-19 world are diverse. Today, the impact of COVID-19 puts safety as the primary demand and motivator for dining out in restaurants, which is influenced by risk perception/optimistic bias, trust, transparency and loyalty. Given this model, the authors posit that transparency is the key strategy for success during this time because it helps restaurants provide useful food and health-related information, eliminate skepticism of being infected, enhance customers’ assurance and reliability of dining out, and finally, establish the high-level intrapersonal assessment— trust of the restaurant. Once the sense of trust has been built, the likelihood of restaurants surviving and resuming from the pandemic would increase because they have higher chances to appeal to loyal customers.

Specifically, in order to build trust and retain customer loyalty, restaurant practitioners are encouraged to be transparent about three of the most critical food handling processes. First, to ensure the transparency in the food supply, they are recommended to disclose all the changes in food ingredients. For example, the spread of COVID-19 may disrupt supply chains and restrict fresh food supply for some restaurants (Littman, 2020). If the restaurant management team decides to switch from fresh ingredients to frozen foods to enable a steady supply, they need to make sure their customers are aware of the changes instead of giving them misleading expectations. Second, to guarantee the transparency of the food cooking process, restaurants are recommended to have glass windows that can give customers a view into the kitchen. During the global crisis, this type of “open kitchen” is not to entertain customers, but to practically showcase the cooking process and to gain trust from customers. A very recent article has made some suggestions for what measurements restaurants should take to bring back customers (Jain, 2020), in which the live cooking counters are strongly recommended to inspire customer confidence because it allows customers to witness the kitchen sanitation, the hygienic food service process, and the way food being cooked from scratch. Third, to make customers more comfortable and safer while enjoying their food, restaurants are suggested to closely guide them to follow the policies such as social distancing and half- or lower- percentage occupancy. Restaurants are recommended to clearly display these policies in their front windows and doors, train staff to properly explain the policies, and keep customers updated via social media platforms, including but not limited to Facebook, Instagram, and TikTok.

4. Limitations and future research

Although this study has both conceptual and practical implications, it still has some limitations. First, as a conceptual paper based on the literature and existing theories, this research lacks available data to test the model, and the assumptions may be confirmed or disproved (e.g., customer motivation to dine out is not affected by loyalty, trust and transparency). Following the fundamental ideas and directions provided by this research, future studies are encouraged to empirically examine the validity of the propositions in this paper.

Also, this study merely includes seven constructs that might influence customers’ motivation to dine out at restaurants during and/or after COVID-19. It is possible that some other variables could impact customers’ desires, such as their financial condition, health status, and the local policy of the restaurant dining-in service.

Additionally, the present study focuses on customers’ dine-in demand and doesn’t address take away or to go dining. The behavior model may look different for customer motivation for this area. A follow up study may address the customer behavior motivating factors for ordering take out or other to go options (e.g., preorder and drive thru) from restaurants. Perhaps the same conceptual model may be applied to the “to go” customer or a different conceptual model may be applied to determine appropriate motivational behaviors for customers.

Finally, this study conceptualized the model under a global pandemic background, with different areas experiencing different conditions. The motives might be different if customers were from distinct areas and had diverse experiences with the pandemic. Customer behavior during COVID-19 and the societal changes the pandemic brings will surely provide information for many lifetimes of research, and the most obvious future research extension is to test the proposed conceptual model. Exploring the type of customer by socio-demographic characteristics mapped to personality characteristics may aid in testing the reliability and validity of the proposed conceptual model. Additional future research beyond empirical model testing may suggest ways to encourage customer dine-in behaviors and help the business soon recover from the shock. Therefore, a study that tests the relationships between personality traits and trust may help restaurant management capture target customers more precisely.

References

- Abdelrahman M. Personality traits, risk perception, and protective behaviors of Arab residents of Qatar during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. 2020:1–12. doi: 10.1007/s11469-020-00352-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agrawal S.R., Mittal D. How does transparency complement customer satisfaction and loyalty in the restaurant business? Glob. Bus. Rev. 2019;20(6):1423–1444. [Google Scholar]

- Aksoydan E. Hygiene factors influencing customers’ choice of dining-out units: findings from a study of university academic staff. J. Food Saf. 2007;27(3):300–316. [Google Scholar]

- Ai P., Liu Y., Zhao X. Big Five personality traits predict daily spatial behavior: evidence from smartphone data. Pers. Individ. Dif. 2019;147:285–291. [Google Scholar]

- Alwi S.F.S. Online corporate brand images and consumer loyalty. Int. J. Bus. Soc. 2009;10(2):1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson M.R. Community psychology, political efficacy, and trust. Polit. Psychol. 2010;31(1):59–84. [Google Scholar]

- Arnott D.C., Wilson D., Doney P.M., Barry J.M., Abratt R. Trust determinants and outcomes in global B2B services. Eur. J. Mark. 2007;41(9/10):1096–1116. [Google Scholar]

- Bai L., Wang M., Yang Y., Gong S. Food safety in restaurants: the consumer perspective. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2019;77:139–146. [Google Scholar]

- Barber N., Scarcelli J.M. Clean restrooms: how important are they to restaurant consumers? J. Foodserv. 2009;20(6):309–320. [Google Scholar]

- Bond L., Nolan T. Making sense of perceptions of risk of diseases and vaccinations: a qualitative study combining models of health beliefs, decision-making and risk perception. BMC Public Health. 2011;11(1):1–14. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bortolotti L. Optimism, agency and success. Ethical Theory Moral Pract. 2018;21:521–535. [Google Scholar]

- Bowen J.T., Shoemaker S. Loyalty: a strategic commitment. Cornell Hotel Restaur. Adm. Q. 2003;44(5-6):31–46. [Google Scholar]

- Bracha A., Brown D. Cowles Foundation Discussion Paper Number 1633. 2007. Affective decision making: a behavioral theory of choice.https://ssrn.com/abstract=1029617 [Google Scholar]

- Bracha A., Brown D.J. Affective decision making: a theory of optimism bias. Games Econ. Behav. 2012;75(1):67–80. [Google Scholar]

- Chuo H.Y. Restaurant diners’ self-protective behavior in response to an epidemic crisis. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2014;38:74–83. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhm.2014.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coibion O., Gorodnichenko Y., Weber M. National Bureau of Economic Research Number 27017; 2020. Labor Markets During the Covid-19 Crisis: A Preliminary View.https://www.nber.org/papers/w27017 [Google Scholar]

- Coleman J.S. Harvard University Press; Cambridge, MA: 1990. Foundations of Social Theory. [Google Scholar]

- Cornelissen J. Editors comments: Developing propositions, a process model, or a typology? Addressing the challenges of writing theory without a boilerplate. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2017;42:1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Da Cunha D.T., Stedefeldt E., de Rosso V.V. He is worse than I am: the positive outlook of food handlers about foodborne disease. Food Qual. Prefer. 2014;35:95–97. [Google Scholar]

- de Andrade M.L., Rodrigues R.R., Antongiovanni N., da Cunha D.T. Knowledge and risk perceptions of foodborne disease by consumers and food handlers at restaurants with different food safety profiles. Food Res. Int. 2019;121:845–853. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2019.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dryhurst S., Schneider C.R., Kerr J., Freeman A.L., Recchia G., Van Der Bles A.M., van der Linden S. Risk perceptions of COVID-19 around the world. J. Risk Res. 2020:1–13. doi: 10.1098/rsos.201199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emmons R.A. In: Goal Concepts in Personality and Social Psychology. Pervin L.A., editor. Psychology Press; 1989. The personal striving approach to personality; pp. 87–126. [Google Scholar]

- Fang X., Mowen J.C. Examining the trait and functional motive antecedents of four gambling activities: slot machines, skilled card games, sports betting, and promotional games. J. Consum. Mark. 2009;26(2):121–131. [Google Scholar]

- Fedoroff I.D., Polivy J., Herman C.P. The effect of pre-exposure to food cues on the eating behavior of restrained and unrestrained eaters. Appetite. 1997;28(1):33–47. doi: 10.1006/appe.1996.0057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson R.J., Paulin M., Bergeron J. Customer sociability and the total service experience. J. Serv. Manag. 2010;21(1):25–44. [Google Scholar]

- Fichera A. FactCheck. 2020. Social media posts make baseless claim on COVID-19 death toll.https://www.factcheck.org/2020/04/social-media-posts-make-baseless-claim-on-covid-19-death-toll/ [Google Scholar]

- Freitag M., Bauer P.C. Personality traits and the propensity to trust friends and strangers. Soc. Sci. J. 2016;53(4):467–476. [Google Scholar]

- Frewer L. Risk perception and risk communication about food safety issues. Nutr. Bull. 2000;25(1):31–33. [Google Scholar]

- Frewer L., Miles S. Temporal stability of the psychological determinants of trust: implications for communication about food risks. Health Risk Soc. 2003;5(3):259–271. [Google Scholar]

- Frewer L., Howard C., Hedderley D., Shepherd R. What determines trust in information about food related risks? Underlying psychological constructs. Risk Anal. 1996;16(4):473–486. doi: 10.1111/j.1539-6924.1996.tb01094.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frewer L., Howard C., Shepherd R. The influence of initial attitudes on responses to communication about genetic engineering in food production. Agric. Human Values. 1998;15(1):15–30. [Google Scholar]

- Gibbs W., Mirsky S. Scientific American. 2020. COVID-19: how and why the virus spreads quickly.https://www.scientificamerican.com/podcast/episode/covid-19-how-and-why-the-virus-spreads-quickly/ [Google Scholar]

- Gilson L.L., Goldberg C.B. Editors’ comment: So, what is a conceptual paper? Group Organ. Manag. 2015;40(2):127–130. [Google Scholar]

- Golan E., Roberts T., Salay E., Caswell J., Ollinger M., Moore D. Agricultural Economic Report Number 831. 2004. Food safety innovation in the United States: evidence from the meat industry.https://www.ers.usda.gov/webdocs/publications/41634/18032_aer831.pdf?v=0 [Google Scholar]

- Gursoy D., Chi C.G. Effects of COVID-19 pandemic on hospitality industry: review of the current situations and a research agenda. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2020;29(5):527–529. [Google Scholar]

- Hardin R. Russell Sage; New York, NY: 2002. Trust and Trustworthiness. [Google Scholar]

- Heger S.A., Papageorge N.W. We should totally open a restaurant: how optimism and overconfidence affect beliefs. J. Econ. Psychol. 2018;67:177–190. [Google Scholar]

- Heikkilä J., Pouta E., Forsman-Hugg S., Mäkelä J. Heterogeneous risk perceptions: the case of poultry meat purchase intentions in Finland. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2013;10(10):4925–4943. doi: 10.3390/ijerph10104925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiraishi K., Yamagata S., Shikishima C., Ando J. Maintenance of genetic variation in personality through control of mental mechanisms: a test of trust, extraversion, and agreeableness. Evol. Hum. Behav. 2008;29(2):79–85. [Google Scholar]

- Hirschheim R. Some guidelines for the critical reviewing of conceptual papers. J. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 2008;9(8):432–441. [Google Scholar]

- Hustvedt G., Bernard J.C. Effects of social responsibility labelling and brand on willingness to pay for apparel. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2010;34(6):619–626. [Google Scholar]

- Jain D. 2020. Effect of COVID-19 on Restaurant Industry–How to Cope With Changing Demand. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson B.B., Covello V.T., editors. The Social and Cultural Construction of Risk. Reidel Publishing Company; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Jonason P.K., Sherman R.A. Personality and the perception of situations: The Big Five and Dark Triad traits. Pers. Individ. Dif. 2020;163:110081. [Google Scholar]

- Jungermann H., Pfister H.R., Fischer K. Credibility, information preferences, and information interests. Risk Anal. 1996;16(2):251–261. [Google Scholar]

- Kandampully J., Zhang T.C., Bilgihan A. Customer loyalty: a review and future directions with a special focus on the hospitality industry. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2015;27(3):379–414. [Google Scholar]

- Karsenty L., Botherel V. Transparency strategies to help users handle system errors. Speech Commun. 2005;45(3):305–324. [Google Scholar]

- Keane A., Willetts A. Goldsmiths College, University of London; London: 1996. Concepts of Healthy Eating: An Anthropological Investigation in South East London. [Google Scholar]

- Kim W.G., Lee Y.K., Yoo Y.J. Predictors of relationship quality and relationship outcomes in luxury restaurants. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2006;30(2):143–169. [Google Scholar]

- Kim J., Morris J.D., Swait J. Antecedents of true brand loyalty. J. Advert. 2008;37(2):99–117. [Google Scholar]

- Kim Y.G., Suh B.W., Eves A. The relationships between food-related personality traits, satisfaction, and loyalty among visitors attending food events and festivals. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2010;29(2):216–226. [Google Scholar]

- Kim J., Almanza B., Ghiselli R., Neal J., Sydnor S. What role does sense of power play in consumers’ decision making of risky food consumption while dining out? J. Foodserv. Bus. Res. 2018;21(1):106–119. [Google Scholar]

- Knight A.J., Worosz M.R., Todd E.C.D. Serving food safety: consumer perceptions of food safety at restaurants. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manage. 2007;19(6):476–484. [Google Scholar]

- Knox B. Consumer perception and understanding of risk from food. Br. Med. Bull. 2000;56(1):97–109. doi: 10.1258/0007142001903003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Label Insight . 2016. How Consumer Demand for Transparency Is Shaping the Food Industry.https://www.labelinsight.com/hubfs/Label_Insight-Food-Revolution-Study.pdf?hsCtaTracking=fc71fa82-7e0b-4b05-b2b4-de1ade992d33%7C95a8befc-d0cc-4b8b-8102-529d937eb427 [Google Scholar]

- Lee L.E., Niode O., Simonne A.H., Bruhn C.M. Consumer perceptions on food safety in Asian and Mexican restaurants. Food Control. 2012;26(2):531–538. [Google Scholar]

- Li Y., Ashkanasy N.M., Ahlstrom D. The rationality of emotions: a hybrid process model of decision-making under uncertainty. Asia Pacific J. Manag. 2014;31(1):293–308. [Google Scholar]

- Li Z., Sha Y., Song X., Yang K., ZHao K., Jiang Z., Zhang Q. Impact of risk perception on customer purchase behavior: a meta-analysis. J. Bus. Ind. Mark. 2020;35(1):76–96. [Google Scholar]

- Lin L.Y. The relationship of consumer personality trait, brand personality and brand loyalty: an empirical study of toys and video games buyers. J. Prod. Brand. Manag. 2010;19(1):4–17. [Google Scholar]

- Littman J. Restaurant Dive. 2020. Recipe for a successful restaurant reopening: transparent marketing.https://www.restaurantdive.com/news/recipe-for-a-successful-restaurant-reopening-transparent-marketing/578889/ [Google Scholar]

- MacInnis D.J. A framework for conceptual contributions in marketing. J. Mark. 2011;75(4):136–154. [Google Scholar]

- Macintosh G. Customer orientation, relationship quality, and relational benefits to the firm. J. Serv. Mark. 2007;21(3):150–159. [Google Scholar]

- McAdams D.P. What do we know when we know a person? J. Pers. 1995;63(3):365–396. [Google Scholar]

- McAdams D.P., Pals J.L. A new Big five: fundamental principles for an integrative science of personality. Am. Psychol. 2006;61(3):204–217. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.61.3.204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCrae R.R., Costa P.T., Jr. In: Handbook of Personality: Theory and Research. John O.P., Robins R.W., Pervin L.A., editors. The Guilford Press; 2008. The five-factor theory of personality; pp. 159–181. [Google Scholar]

- Meredith J. Theory building through conceptual methods. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manage. 1993;13(5):3–11. [Google Scholar]

- 2010. Merriam‐Webster Online Dictionary.http://www.merriamwebster.com/dictionary/transparent Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Mowen J.C., editor. The 3M Model of Motivation and Personality: Theory and Empirical Applications to Consumer Behavior. Kluwer Academic Publishers; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Neel R., Kenrick D.T., White A.E., Neuberg S.L. Individual differences in fundamental social motives. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2016;110(6):887–907. doi: 10.1037/pspp0000068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oatley K., Johnson-Laird P.N. Towards a cognitive theory of emotions. Cogn. Emot. 1987;1(1):29–50. [Google Scholar]

- Oliver R.L. Whence consumer loyalty? J. Mark. 1999;63(4_suppl1):33–44. [Google Scholar]

- Ozili P.K., Arun T. Spillover of COVID-19: impact on the global economy. SSRN. 2020 doi: 10.2139/ssrn.3562570. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Parasuraman A., Zeithaml V., Berry L. A conceptual model of service quality and its implications for future research. J. Mark. 1985;49(4):41–50. [Google Scholar]

- Parasuraman A., Zeithaml V., Berry L. SERVQUAL: a multiple-item scale for measuring consumer perceptions of service quality. J. Retail. 1988;64(1):12–40. [Google Scholar]

- Payne A., Frow P., Eggert A. The customer value proposition: evolution, development, and application in marketing. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2017;45(4):467–489. [Google Scholar]

- Pressman P., Naidu A.S., Clemens R. COVID-19 and food safety: risk management and future considerations. Nutr. Today. 2020;55(3):125–128. [Google Scholar]

- Rashid S., Abu N.K., Ahmad R.H.R. Influence of relationship quality on hotel guests’ loyalty: a case study of Malaysian budget hotel. J. Sci. Ind. Res. 2011;2(6):220–229. [Google Scholar]

- Rauyruen P., Miller K.E. Relationship quality as a predictor of B2B customer loyalty. J. Bus. Res. 2007;60(1):21–31. [Google Scholar]

- Rossi M.D.S.C., Stedefeldt E., da Cunha D.T., de Rosso V.V. Food safety knowledge, optimistic bias and risk perception among food handlers in institutional food services. Food Control. 2017;73:681–688. [Google Scholar]

- Ryu K., Lee H., Kim W.G. The influence of the quality of the physical environment, food, and service on restaurant image, customer perceived value, customer satisfaction, and behavioral intentions. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manage. 2012;24(2):200–223. [Google Scholar]

- Schneider P.P., Vogt C.A. Applying the 3M model of personality and motivation to adventure travelers. J. Travel. Res. 2012;51(6):704–716. [Google Scholar]

- Schoemaker P.J. Springer Science & Business Media; 2013. Experiments on Decisions Under Risk: The Expected Utility Hypothesis. [Google Scholar]

- Selnes F. Antecedents and consequences of trust and satisfaction in buyer‐seller relationships. Eur. J. Mark. 1998;32(3/4):305–322. [Google Scholar]

- Slovic P., Finucane M.L., Peters E., MacGregor D.G. Risk as analysis and risk as feelings: some thoughts about affect, reason, risk, and rationality. Risk Anal. 2004;24(2):311–322. doi: 10.1111/j.0272-4332.2004.00433.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith T. The personality trait predictors of brand loyalty. Acad. Bus. Res. 2012;3:6–21. [Google Scholar]

- Smith P.G., Bradley R. Bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE) and its epidemiology. Br. Med. Bull. 2003;66(1):185–198. doi: 10.1093/bmb/66.1.185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tehrani H.D., Yamini S. Personality traits and conflict resolution styles: a meta-analysis. Pers. Individ. Dif. 2020;157 [Google Scholar]

- Turhan G. Risk perceptions and brand extension success: just another antecedent or one that shapes the effects of others?-Study of examples in textiles and clothing. Fibres Text. East. Eur. 2014;3(105):23–30. [Google Scholar]

- Tuttle B. Food and Beverage Industry; 2012. Nothing to Hide: Why Restaurants Embrace the Open Kitchen.http://www.business.time.com/2012/08/20/nothing-to-hide-why-restaurants-embrace-the-open-kitchen/ [Google Scholar]

- UCL . UCL School of Management; 2015. The Power of Transparency in Dining Experiences.http://www.mgmt.ucl.ac.uk/news/power-transparency-dining-experiences [Google Scholar]

- Ungku Fatimah U.Z.A., Boo H.C., Sambasivan M., Salleh R. Foodservice hygiene factors of the consumer perspective. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2011;30(1):38–45. [Google Scholar]

- Vollrath M., Torgersen S. Who takes health risks? A probe into eight personality types. Pers. Individ. Dif. 2002;32(7):1185–1197. [Google Scholar]

- Wang C.M., Xu B.B., Zhang S.J., Chen Y.Q. Influence of personality and risk propensity on risk perception of Chinese construction project managers. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2016;34(7):1294–1304. [Google Scholar]

- Weinstein N.D. Optimistic biases about personal risks. Science. 1989;246(4935):1232–1233. doi: 10.1126/science.2686031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeung R.M., Morris J. Food safety risk. Br. Food J. 2001;103(3):170–186. [Google Scholar]

- Yeung R., Yee W., Morris J. The effects of risk-reducing strategies on consumer perceived risk and on purchase likelihood. Br. Food J. 2010;112(3):306–322. [Google Scholar]

- Zajenkowski M., Jonason P.K., Leniarska M., Kozakiewicz Z. Who complies with the restrictions to reduce the spread of COVID-19? Personality and perceptions of the COVID-19 situation. Pers. Individ. Dif. 2020;166 doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2020.110199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zepeda L., Douthitt R., You S.Y. Consumer risk perceptions toward agricultural biotechnology, self‐protection, and food demand: the case of milk in the United States. Risk Anal. 2003;23(5):973–984. doi: 10.1111/1539-6924.00374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zwanka R.J., Buff C. COVID-19 generation: a conceptual framework of the consumer behavioral shifts to be caused by the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Int. Consum. Mark. 2020:1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Wilkowski B.M., Robinson M.D., Meier B.P. Agreeableness and the prolonged spatial processing of antisocial and prosocial information. J. Res. Pers. 2006;40(6):1152–1168. [Google Scholar]