Abstract

The conceptualization of Identification with All Humankind (IWAH) suggests that human beings care deeply not only for their own ingroups but for all humanity as a whole. The COVID-19 pandemic has witnessed so much international help across national borders. Inspired by research on IWAH, we examined whether IWAH was associated with adolescents' sympathy for people in COVID-19 affected countries, which was further related to their willingness to help. The moderating role of conscientiousness on this indirect association was also examined. Eight hundred and fifty four students were recruited as participants. Data were obtained with adolescents reporting on their IWAH, sympathy for and willingness to help people in COVID-19 affected countries. The results indicated that IWAH was both directly and indirectly associated with their willingness to help people in COVID-19 affected countries via sympathy for them. Adolescents' conscientiousness moderated the indirect relation of adolescents' IWAH with their willingness to help via sympathy for people in COVID-19 affected countries. Specifically, for adolescents high in conscientiousness, IWAH was more strongly associated with willingness to give help. The main conclusion is that adolescents high in IWAH were more likely to experience sympathy for people in COVID-19 affected countries, thus making them more likely to give help, especially for adolescents high in conscientiousness.

Keywords: Identification with all humanity, Willingness to help, Sympathy, Conscientiousness, Adolescent

1. Introduction

Researchers have posited the construct of Identification with All Humanity (IWAH) to express the idea that all humanity is our ingroup and all human beings on earth belong to just one global community (McFarland et al., 2012). Given that a common fate may produce a sense of “we-ness” that further promotes intergroup prosocial tendencies (Flippen et al., 1996; Zhang, 2019), IWAH should decrease the impact of transnational differences on mutual prosociality between different countries, especially during such an upheaval as the COVID-19 pandemic.

Since its outbreak, the COVID epidemic has exerted profound influences on people's daily life in every country. Due to its lethal nature, the number of deaths is still increasing every day. It may be the largest disaster since World War II (Gautam, 2020). The entire humankind faces unprecedented challenges in various domains, necessitating international concerted efforts for coping with this global health crisis. Such an unfortunate common fate may highlight the role of IWAH in facilitating transnational prosociality. This study intended to examine how IWAH is associated with adolescents' sympathy for people in other COVID-19 affected countries and their willingness to help them. We also examined whether conscientiousness, one of the Big Five dimensions, moderates the foregoing associations. Although we could not measure adolescents' actual prosocial behaviors due to the home quarantine practices, we had the alternative to assess how Identification with All Humanity (IWAH) was associated with adolescents' sympathy for and willingness to help people in other COVID-19 affected countries. We expected our findings to shed more light on the important role of IWAH in promoting international prosociality, especially in the context of the COVID-19 epidemic.

1.1. Identification with all humanity and willingness to help people in COVID-19 affected countries

Identification with all humanity (IWAH) indicates a tendency to identify with all human beings as a whole, not just one's own ingroup (McFarland et al., 2012). IWAH means a deep caring for all human beings, more than the absence of ethnocentrism and the presence of moral reasoning and moral identity. Maslow (1954) had characterized his “self-actualized individuals” as having a deep feeling of identification and affection for human beings in general and a genuine desire to help every member of the human species. Research has demonstrated that people high in IWAH display greater concern for human rights and humanitarian needs, value the lives of ingroup and outgroup members equally, and tend to be willing to make a contribution to international humanitarian relief (McFarland et al., 2012). Viewing all humanity as a big family, people high in IWAH harbor a genuine concern for the wellbeing of others and a responsibility for others, regardless of their race or religion. Higher IWAH has been consistently associated with more concerns over global issues such as humanitarian needs and universal human rights (McFarland et al., 2013). In the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, adolescents high in IWAH may be more likely to help people in COVID-19 affected countries.

Ample evidence indicates that group membership (ingroup versus outgroup) plays an important role in helping (Omoto & Snyder, 2002; Weisel & Böhm, 2015). People are motivated to express more positive attitudes and helping behaviors toward ingroup than outgroup members (Cikara et al., 2011; Hein et al., 2010). When people are highly identified with all human beings, they may tend to regard people from different countries as from the same ingroup, thus enhancing their sympathy and help toward them. Members with a common group identity help each other more frequently than those with different memberships. A social identity approach suggests that strangers may come to identify with each other as from a common group under certain conditions and this even may be the case in some emergency situations involving danger for the helper (Levine & Manning, 2013). Therefore, in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, adolescents high in IWAH should be more willing to help people in COVID-19 affected countries.

1.2. Identification with all humanity and sympathy for people in COVID-19 affected countries

As an emotional response, sympathy is triggered by another's emotional state, generally involving feelings of sorrow and concern for others' welfare (Eisenberg et al., 2015). Sympathy tends to occur in familiar relations, which has been termed as “proximity effects” by some researchers (Schwalm, 2020). By its conception, individuals high in IWAH perceive all human beings as from one common group, thus perceiving people all over the world as more similar and relevant to them than those low in IWAH (McFarland et al., 2012). This perceived similarity triggers greater sympathy for members of the same group. Indeed, sympathy is stronger among people who feel similar (Valdesolo & Desteno, 2011), especially among emotionally close ones (Korchmaros & Kenny, 2001). The perceived self-other similarities tend to make us feel others as the same kind of people as ourselves (Rothbart & Taylor, 1992). The more people perceive others as similar to themselves, the more likely they regard other's welfare as self-relevant and altruistically react to their plight (Park & Schaller, 2005; Różycka-Tran, 2017). By contrast, when people feel irrelevant to the sufferers, they are less likely to be moved by their suffering and less likely to concern empathically (Batson et al., 2007). Therefore, adolescents high in IWAH should be more inclined to deem all the human beings as belonging to one integrated group and thus feel more close to people from different countries, consequently more prone to sympathy for people in COVID-19 affected countries.

1.3. Sympathy for people in COVID-19 affected countries and willingness to help

Disasters occur now and then all over the world, with disasters in one country often arousing sympathetic feelings in people from other countries and moving them to provide international aid. As an emotional response, sympathy is demonstrated in one's feelings of sorrow for the misfortunes of the distressed people (Eisenberg, 2010). Sympathetic feelings are consistently related to prosocial behaviors (Carlo et al., 2010; Hoffman, 2000). People in sympathy are more likely to emotionally share others' distresses and thus feel a greater desire to help and a motive to alleviate others' distresses (Carlo et al., 2015). Just like in this global COVID pandemic, we feel sympathetic for the pandemic situations in other countries and provided help toward them. Generally, the greater sympathy people have for the needy people, the stronger their desire is to help them (Chi et al., 2020). Conceivably, people who feel sympathetic for overseas COVID-19 affected people should be more likely to give help. We expected that adolescents high in sympathy with COVID-19 affected people are more willing to help them. Flowing from the above inferences, adolescents high in IWAH are more likely to feel sympathetic for people in COVID-19 affected countries, and thus more willing to help them.

1.4. The moderating role of adolescents' conscientiousness

As one of the Big Five dimensions, conscientiousness circumscribes a human proclivity to be organized and responsible. People high in conscientiousness generally follow socially approved norms and rules (Roberts et al., 2009). Conscientious people are characterized as reliable and consciously complying with moral standards (Egan et al., 2017; McCrae & Costa, 1997). Personality plays an important role in coping with difficult situations. In particular, conscientiousness has been the most effective predictor of problem-solving coping with stressful situations (Bartley & Roesch, 2011; Zhou et al., 2017). Moreover, conscientiousness is closely related to people's prosocial responses to others' distress (Courbalay et al., 2015) and positive changes in conscientiousness can longitudinally predict positive changes in prosociality (Kanacri et al., 2014).

Therefore, high conscientiousness may promote people with high IWAH to help the needy people in COVID-19 affected countries. By contrast, in spite of high identification with all humanity, people low in conscientiousness may still lack the responsibility to help people in distress.

1.5. Hypotheses of the current study

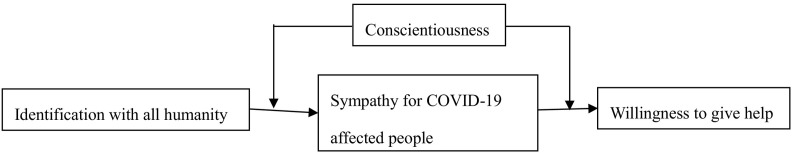

To sum up, we aimed to examine the association between adolescents' IWAH and their willingness to help people in COVID-19 affected countries, focusing on the mediating role of sympathy and the moderating role of conscientiousness in this relationship. The following hypotheses were postulated and addressed by testing a moderated mediation model as shown in Fig. 1 .

Hypothesis 1

Adolescents high in identification with all humanity would be more willing to help people in COVID-19 affected countries.

Hypothesis 2

Sympathy for people in COVID-19 affected countries might mediate the association between adolescents' IWAH and their willingness to help people in COVID-19 affected countries, in that adolescents who were more identified with all humanity were more likely to feel sympathetic for the sufferings of COVID affected people and thus were more willing to help them.

Hypothesis 3

Adolescents' conscientiousness might moderate the indirect association between adolescents' IWAH and their willingness to help, in that this indirect association would be stronger for adolescents with greater conscientiousness.

Fig. 1.

A model on how IWAH is related to willingness to help people in COVID-19 affected countries.

2. Method

2.1. Participants

Nearly nine hundred students were recruited as participants from the first and second grades of two middle schools situated in an Eastern coastal city of China. The third graders were not used because of their forthcoming final examination. Although the teachers greatly support our investigation, two or three students in each class choose not to participate. Finally, complete data were secured for eight hundred and fifty four students (458 boys and 396 girls, M age = 13.45, SD = 1.12). Missing data was handled using full information maximum likelihood estimation (Enders & Bandalos, 2001).

2.2. Measures

Identification with all humanity was assessed using the 9 items on the Identification with All Humanity Scale (McFarland et al., 2012). Sample items were, “How close do you feel to people all over the world?” and “How much would you say you have in common with people all over the world?” Adolescents rated each item on a 5-point Likert scale from 1 (not at all) to 5 (very much). This measure demonstrated satisfactory internal consistency (α = 0.83). Confirmatory factor analyses indicated that one-factor model fit the data satisfactorily: χ 2/df = 5.11, comparative fit index (CFI) = 0.96, root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) = 0.071, with item loading values ranging from 0.59 to 0.77. The average of the values for the 9 items was computed to index adolescents' identification with all humanity.

Sympathy for people in COVID-19 affected countries was assessed with 13 items adapted from the Trait Sympathy Scales (TSS; Lee, 2009). Sample items were, “At the thought of sufferings of people in many COVID-19 affected countries, I would probably become teary eyed or close to crying” and “It would really disturb me to see the shortage of medical supplies and daily necessities (e.g., face masks) in some countries due to the COVID-19 pandemic”. This instrument displayed satisfactory internal consistency (α = 0.89). Adolescents rated each item on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = disagree strongly, 5 = agree strongly). Confirmatory factor analyses demonstrated that one-factor model fit the data satisfactorily: χ 2/df = 6.41, comparative fit index (CFI) = 0.97, root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) = 0.043, with item loading values ranging from 0.65 to 0.81. The average of the values for the 13 items was computed to index adolescents' Sympathy for people in COVID-19 affected countries.

Willingness to help people in COVID-19 affected countries was assessed with 5 items. Sample items were, “I am willing to provide medical supplies and daily necessities to people in COVID-19 affected countries” and “I willingly volunteer to help people in any COVID-19 affected country.” Adolescents rated each item on a 5-point Likert scale from 1 (almost always untrue of me) to 5 (almost always true of me). Confirmatory factor analyses demonstrated that one factor model fit the data satisfactorily: χ 2/df = 3.96, comparative fit index (CFI) = 0.98, root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) = 0.046, with item loading values ranging from 0.63 to 0.76. The average of the 5 items was computed to index the level of adolescents' willingness to help.

Adolescent conscientiousness was assessed with the 12-item conscientiousness subscale of the 60-item NEO Five-Factor Inventory (Costa & McCrae, 1992). Sample items were, “I try to perform all the tasks assigned to me conscientiously,” and “I'm pretty good about pacing myself so as to get things done on time.” Each item was rated on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = completely not true, 5 = completely true). This measure displayed satisfactory internal consistency here (α = 0.89). Confirmatory factor analyses indicated that one-factor model fit the data satisfactorily: χ 2/df = 5.53, comparative fit index (CFI) = 0.97, root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) = 0.07, with item loading values ranging from 0.58 to 0.72.

Controlled variables. Age and gender have been related to sympathy and prosocial behaviors (Carlo et al., 2015; Eisenberg et al., 2006; Vossen et al., 2015) and thus were controlled for in this study.

2.3. Procedures

During early May of the 2020 year, students in many areas of China were still in home quarantine to prevent the risk of the coronavirus infection. Therefore, we conduct our investigation using online questionnaires. First, we contacted junior high school teachers who informed students of this investigation through an online platform. Students and their parents offered consent to participate in this survey through online platforms. Ethical issues such as confidentiality were explained via online standardized instructions. On completion, participants obtained a chance to draw a lottery.

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive analyses

As shown in Table 1 , adolescents' identification with all humanity (IWAH) was positively associated with their sympathy for people in COVID-19 affected countries and their willingness to help them (rs = 0.52 and 0.40, respectively, ps < 0.001), indicating that adolescents high in IWAH were more likely to feel sympathy for people in COVID-19 affected countries and more willing to help them. Adolescents' sympathy for people in COVID-19 affected countries was positively associated with their willingness to help them (r = 0.51, p < 0.001), indicating that adolescents high in sympathy were more willing to help. Adolescents' conscientiousness was positively associated with adolescents' IWAH (r = 0.37, p < 0.001), sympathy (r = 0.40, p < 0.001), and their willingness to help (r = 0.42, p < 0.01).

Table 1.

Descriptive and correlational statistics for the main variables.

| Variables | M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.Child gender | – | – | – | ||||

| 2.Child age | 13.45 | 0.67 | – | – | |||

| 3.IWAH | 3.92 | 0.83 | 0.12⁎⁎ | 0.06 | – | ||

| 4.Sympathy for COVID affected people | 3.47 | 0.78 | 0.20⁎⁎⁎ | −0.08⁎ | 0.52⁎⁎⁎ | – | |

| 5.Willingness to help COVID affected people | 3.28 | 0.94 | 0.07⁎ | −0.15⁎⁎⁎ | 0.40⁎⁎⁎ | 0.51⁎⁎⁎ | – |

| 6.Conscientiousness | 4.16 | 0.82 | 0.10⁎⁎ | −0.11⁎⁎ | 0.37⁎⁎⁎ | 0.40⁎⁎⁎ | 0.42⁎⁎⁎ |

Note. N = 854. Gender was dummy coded such that 0 = boy and 1 = girl. IWAH = Identification with all humanity. M = mean. SD = standard deviation.

p < 0.05.

p < 0.01.

p < 0.001.

3.2. Testing the moderated mediation model

To test the hypothesized model, we took the approach by Muller et al. (2005) to estimate the parameters for three regression models. Model 1 estimated the moderating effect of adolescent conscientiousness on the relationship between adolescents' IWAH and their willingness to help. Model 2 estimated the moderating effect of adolescent conscientiousness on the association between adolescents' IWAH and their sympathy for people in COVID-19 affected countries. Model 3 estimated the moderating effect of adolescent conscientiousness on both the partial effect of adolescents' sympathy for people in COVID-19 affected countries on their willingness to help them and the residual effect of adolescents' IWAH on their willingness to help. The details for specifying the above three models have been displayed in Table 2 . All predictors were first standardized to improve the ease of interpretation and to minimize potential multicollinearity (Dearing & Hamilton, 2006). Edwards and Lambert (2007) have suggested that moderated mediation could be judged to exist if either or both of the following two moderating patterns appear: (i) the path from adolescents' IWAH to their sympathy was moderated by adolescent conscientiousness, and/or (ii) the path from adolescents' sympathy to their willingness to help was moderated by adolescents' conscientiousness.

Table 2.

Testing the moderated mediation model.

| Predictors | Model 1 (Criterion WHCAP) |

Model 2 (Criterion SCAP) |

Model 3 (Criterion WHCAP) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | t | β | t | β | t | |

| CO:gender | 0.01⁎ | 0.26 | 0.13 | 4.60⁎⁎⁎ | 0.04 | 1.27 |

| CO:age | −0.03 | −1.26 | −0.05 | −1.82 | −0.04 | −1.06 |

| X: Identification with all humanity (IWAH) | 0.31 | 9.45⁎⁎⁎ | 0.42 | 13.46⁎⁎⁎ | 0.14 | 4.02⁎⁎⁎ |

| MO: conscientiousness | 0.29 | 8.63⁎⁎⁎ | 0.23 | 7.40⁎⁎⁎ | 0.22 | 7.19⁎⁎⁎ |

| XMO: IWAH × conscientiousness | 0.13 | 4.49⁎⁎⁎ | 0.09 | 3.05⁎⁎ | 0.03 | 1.24 |

| ME: sympathy for COVID affected people (SCAP) | 0.34 | 9.88⁎⁎⁎ | ||||

| MEMO: SCAP × conscientiousness | 0.02 | 0.81 | ||||

| R2 | 0.27 | 0.35 | 0.34 | |||

| F | 61.14⁎⁎⁎ | 89.91⁎⁎⁎ | 62.39⁎⁎⁎ | |||

Note. N = 854. Each column represents a regression model that predicts the criterion at the top of the column. Gender was coded as 0 = boy and 1 = girl. CO, X, MO, and ME successively represent control variable, independent variable, moderator, and mediator. XMO and MEMO represent the interaction between independent variable and moderator and that between mediator and moderator, respectively. WHCAP = Willingness to help COVID-19 affected people.

p < 0.05.

p < 0.01.

p < 0.001.

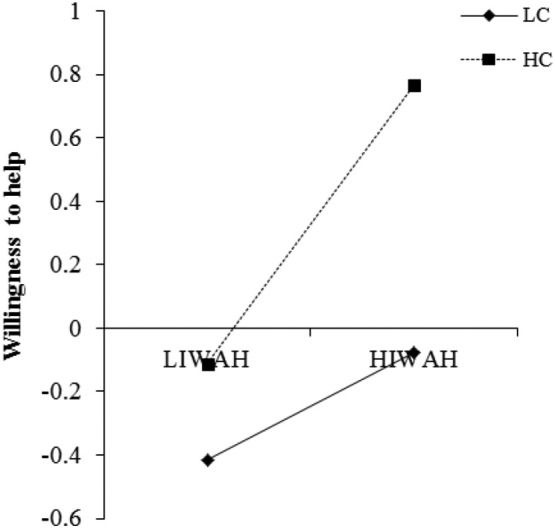

As shown in Table 2, the first model presented both a significant main effect of IWAH (β = 0.31, p < 0.001) and a significant IWAH × conscientiousness interaction effect on adolescents' willingness to help people in COVID-19 affected countries (β = 0.13, p < 0.001). For descriptive convenience, we plotted the predicted adolescents' willingness to help against their IWAH, separately for low and high levels of conscientiousness (1 standard deviation (SD) below the mean and 1 SD above the mean, respectively) (Fig. 2 ). Simple slope test results revealed that IWAH was more strongly associated with willingness to help among adolescents with high conscientiousness (b simple = 0.44, p < 0.001) in contrast to those with low conscientiousness (b simple = 0.17, p < 0.001). In other words, high conscientiousness may strengthen the effect of adolescents' IWAH on their willingness to help COVID-19 affected people.

Fig. 2.

Identification with all humanity × conscientiousness interactive effects in relation to willingness to help people in COVID-19 affected countries. LC (HC) = low (high) conscientiousness. LIWAH (IWAH) = low (high) identification with all humanity.

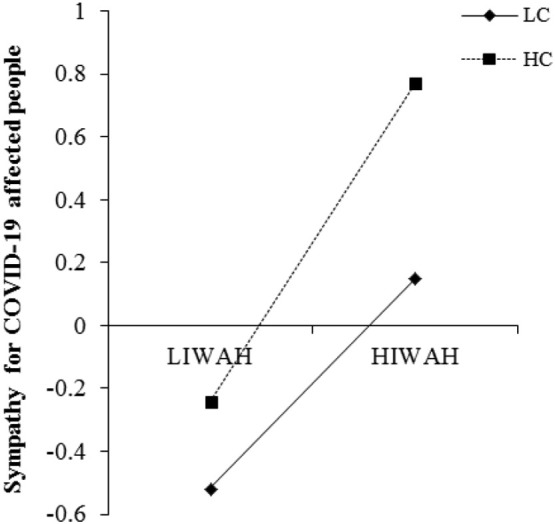

The second model provided both a significant main effect of IWAH (β = 0.42, p < 0.001) and a significant IWAH × conscientiousness interaction effect on adolescents' sympathy for people in COVID-19 affected countries (β = 0.09, p < 0.01). For descriptive convenience, we plotted the predicted adolescents' sympathy for COVID-19 affected people against their IWAH, separately for low and high levels of conscientiousness (1 standard deviation (SD) below the mean and 1 SD above the mean, respectively) (Fig. 3 ). Simple slope test results revealed that IWAH was more strongly associated with sympathy for people in COVID-19 affected countries among adolescents with high conscientiousness (b simple = 0.51, p < 0.001) in contrast to those with low conscientiousness (b simple = 0.33, p < 0.001). In other words, high conscientiousness may strengthen the effect of adolescents' IWAH on their sympathy for COVID-19 affected people. In the third model, there was a positive effect of adolescents' sympathy on their willingness to help (β = 0.34, p < 0.001) after controlling for adolescents' IWAH.

Fig. 3.

Identification with all humanity × conscientiousness interactive effects in relation to sympathy for people in COVID-19 affected countries. LC (HC) = low (high) conscientiousness. LIWAH (IWAH) = low (high) identification with all humanity.

4. Discussion

Although research on IWAH has been associated with people's willingness to contribute to international humanitarian relief (McFarland et al., 2012), the processes underlying this association are still unclear. We conducted this investigation in early May in 2020 in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. By testing a moderated mediation model, we examined the potential mediating role of sympathy and the moderating role of consciousness in this association. Our findings demonstrated that beyond the direct effect, the indirect effect of adolescents' IWAH on their willingness to help people in COVID-19 affected countries was mediated by their sympathy for them and this indirect association was moderated by adolescents' conscientiousness. For adolescents high in conscientiousness, IWAH was more strongly associated with their sympathy for, and their willingness to help, COVID-19 affected countries.

4.1. The mediating role of sympathy for people in COVID-19 affected countries

Our findings demonstrated that adolescents' IWAH was both directly and indirectly related to their willingness to help people in foreign affected areas. The significant direct path was consistent with research indicating that people were more likely to help those with a common category membership (Levine & Thompson, 2004). Dower (2002) has suggested that all human beings are global citizens but some people lack this awareness of their close connection with the whole humanity. Categorizing with a common group membership promotes people to engage in prosocial behaviors (Crisp & Hewstone, 2007). People with global awareness have a greater responsibility to help others, expressing empathic caring toward the needy people (Reysen et al., 2013; Reysen & Katzarska-Miller, 2013). As our findings demonstrated, IWAH might directly make adolescents more aware of their global citizenship and more willing to help people in foreign affected areas.

Additionally, sympathy may also play a mediating role in the above relationship. Adolescents high in IWAH were more likely to feel sympathetic for people in COVID affected countries. This is because people with greater IWAH tend to perceive all the human beings as members of a global community with a common destiny. This perceived similarity in group membership facilitates empathic concern toward the needy person's welfare, further promoting the helper to invest personal resources on behalf of others in need (Stürmer et al., 2006). The reference-dependent sympathy effect suggests that sympathy stems from the discrepancy between the victims' current condition and a reference point (Sudhir et al., 2016). The COVID pandemic has seriously disturbed our normal life and caused numerous deaths and this great decline makes people more prone to sympathy for the pandemic victims. Sympathy is a central moral emotion in motivating help-giving behaviors (Russell & Mentzel, 1990). Following disasters such as earthquakes and hurricanes, people tend to feel compassion toward the victims and treat them more prosocially (Zaki, 2020). As COVID-19 spreads, different regions around the world have actively joined to help vulnerable affected areas (Samuel, 2020). As our findings demonstrated, adolescents who had a greater identification with all humanity might have a greater sympathy for people in COVID-19 affected countries, making them more willing to help those distressed by the pandemic.

4.2. The moderating role of adolescents' conscientiousness

Our findings revealed that conscientiousness played a moderating role in the meditational relations discussed above. People high in conscientiousness tend to regulate their behaviors appropriately (Eisenberg et al., 2014). Being confronted with difficulties, conscientious people can competently control negative thoughts and feelings, engaging in effective coping strategies like problem solving (Zhou et al., 2017). The COVID-19 epidemic threatens everyone's safety. Although the identification with all human beings makes individuals more inclined to regard the entire human race as one family, in the face of the threat of the epidemic, individuals with low responsibility may have difficulty coping with the pressure from the epidemic. They may not sympathize more with others, but focus more attention only on themselves, causing personal pain, and making it difficult to provide assistance for others. In contrast, highly conscientious individuals are better at coping with stressors and thus can competently adjust themselves to cope with the perceived stress in the pandemic. Just as our findings indicated, conscientiousness boosted the impact of adolescents' IWAH on both their sympathy for and their willingness to help people in COVID-19 affected countries.

4.3. Research limitations

The prominent limitation is that we only measured adolescents' willingness to help COVID-19 affected people. A measure that can assess adolescents' actual helping behaviors may provide more insights into how IWAH may affect helping behaviors. However, due to both the home quarantine practice in our country and the time we conducted this investigation, adolescents could perform limited helping behaviors toward needy people in different countries. However, they expressed great concern for people in COVID-19 affected countries according to data we had gathered. Second, due to the limited time, we could only use adapted items from existing questionnaires to measure both sympathy for and willingness to help people in affected areas. Fortunately, these questionnaires displayed satisfactory internal reliability and construct validity in our study. Finally, due to our cross-sectional design, causal relations among the variables remain to be explored with a longitudinal design in the future. Despite the few limitations, our study highlighted the importance of identification with all humanity (IWAH) in promoting international assistance. Our findings of higher willingness to give help among adolescents with higher IWAH also revealed the potential role of IWAH in creating a harmonious global community and promoting mutual help across national borders.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

I am the only author of this work.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgments

This research is supported by Key Project granted by China National Social Science Foundation Titled “Xi Jinping’s New Era Logic System of Ecological Civilization Thoughts and their great research values ” (Grant Number: 18AKS007).

References

- Bartley C.E., Roesch S.C. Coping with daily stress: The role of conscientiousness. Personality and Individual Differences. 2011;50:79–83. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2010.08.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batson C.D., Eklund J.H., Chermok V.L., Hoyt J.L., Ortiz B.G. An additional antecedent of empathic concern: Valuing the welfare of the person in need. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2007;93:65–74. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.93.1.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlo G., Mestre M.V., Samper P., Tur A., Armenta B.E. Feelings or cognitions? Moral cognitions and emotions as longitudinal predictors of prosocial and aggressive behaviors. Personality and Individual Differences. 2010;48:872–877. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2010.02.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carlo G., Padilla-Walker L.M., Nielson M.G. Longitudinal bidirectional relations between adolescents’ sympathy and prosocial behavior. Developmental Psychology. 2015;51:1771–1777. doi: 10.1037/dev0000056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chi S.C.S., Friedman R.A., Chen S.C., Tsai M.J., Yuan M.L. Sympathy toward a company facing disaster: Examining the interaction effect between internal attribution and role similarity. The Journal of Applied Behavioral Science. 2020;56:73–106. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.73.3.481. doi:10.1177/0021886319876699. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cikara M., Bruneau E.G., Saxe R.R. Us and them: Intergroup failures of empathy. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2011;20:149–153. doi: 10.1177/2F0963721411408713. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Costa P.T., McCrae R.R. Psychological Assessment Resources; 1992. Revised NEO personality inventory (NEO-PI-R) and Neo five-factor inventory (NEO-FFI) [Google Scholar]

- Courbalay A., Deroche T., Prigent E., Chalabaev A., Amorim M.A. Big five personality traits contribute to prosocial responses to others’ pain. Personality and Individual Differences. 2015;78:94–99. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2015.01.038. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Crisp R.J., Hewstone M. Multiple social categorization. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology. 2007;39:163–254. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2601(06)39004-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dearing E., Hamilton L.C. Contemporary advances and classic advice for analyzing mediating and moderating variables. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development. 2006;71:88–104. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-5834.2006.00406.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dower N. In: Global citizenship: A critical introduction. Dower N., Williams J., editors. Routledge; New York, NY: 2002. Global citizenship: Yes or no? pp. 30–40. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards J.R., Lambert L.S. Methods for integrating moderation and mediation: A general analytical framework using moderated path analysis. Psychological Methods. 2007;12:1–22. doi: 10.1037/1082-989X.12.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egan M., Daly M., Delaney L., Boyce C.J., Wood A.M. Adolescent conscientiousness predicts lower lifetime unemployment. Journal of Applied Psychology. 2017;102:700–709. doi: 10.1037/apl0000167. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1037/apl0000167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N. In: Prosocial motives, emotions, and behavior: The better angels of our nature. Mikulincer M., Shaver P.R., editors. American Psychological Association; 2010. Empathy-related responding: Links with self-regulation, moral judgment, and moral behavior; pp. 129–148. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N., Duckworth A.L., Spinrad T.L., Valiente C. Conscientiousness: Origins in childhood? Developmental Psychology. 2014;50:1331–1349. doi: 10.1037/a0030977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N., Fabes R.A., Spinrad T.L. In: Handbook of child psychology. Eisenberg N., editor. Wiley; New York, NY: 2006. Prosocial development; pp. 646–718. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N., VanSchyndel S.K., Hofer C. The association of maternal socialization in childhood and adolescence with adult offsprings’ sympathy/caring. Developmental Psychology. 2015;51:7–16. doi: 10.1037/a0038137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enders C.K., Bandalos D.L. The relative performance of full information maximum likelihood estimation for missing data in structural equation models. Structural Equation Modeling. 2001;8:430–457. doi: 10.1207/s15328007sem3_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flippen A.R., Hornstein H.A., Siegal W.E., Weitzman E.A. A comparison of similarity and interdependence as triggers for in-group formation. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 1996;22:882–893. doi: 10.1177/0146167296229003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gautam S. The influence of COVID-19 on air quality in India: A boon or inutile. Bulletin of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology. 2020;104:724–726. doi: 10.1007/s00128-020-02877-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hein G., Silani G., Preuschoff K., Batson C.D., Singer T. Neural responses to ingroup and outgroup members’ suffering predict individual differences in costly helping. Neuron. 2010;68:149–160. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman M.L. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge, UK: 2000. Empathy and moral development: Implications for caring and justice. [Google Scholar]

- Kanacri B.P.L., Pastorelli C., Eisenberg N., Zuffianò A., Castellani V., Caprara G.V. Trajectories of prosocial behavior from adolescence to early adulthood: Associations with personality change. Journal of Adolescence. 2014;37:701–713. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2014.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korchmaros J.D., Kenny D.A. Emotional closeness as a mediator of the effect of genetic relatedness on altruism. Psychological Science. 2001;12:262–265. doi: 10.1111/1467-9280.00348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S.A. Measuring individual differences in trait sympathy: Instrument construction and validation. Journal of Personality Assessment. 2009;91:568–583. doi: 10.1080/00223890903228620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine M., Manning R. Social identity, group processes, and helping in emergencies. European Review of Social Psychology. 2013;24:225–251. doi: 10.1080/10463283.2014.892318. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Levine M., Thompson K. Identity, place, and bystander intervention: Social categories and helping after natural disasters. The Journal of Social Psychology. 2004;144:229–245. doi: 10.3200/socp.144.3.229-245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maslow A. Harper & Row; New York, NY: 1954. Motivation and personality. [Google Scholar]

- McCrae R.R., Costa P.T. Personality trait structure as a human universal. American Psychologist. 1997;52:509–516. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.52.5.509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McFarland S., Brown D., Webb M. Identification with all humanity as a moral concept and psychological construct. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2013;22:194–198. doi: 10.1177/2F0963721412471346. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McFarland S., Webb M., Brown D. All humanity is my ingroup: A measure and studies of identification with all humanity. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2012;103:830–853. doi: 10.1037/a0028724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller D., Judd C.M., Yzerbyt V.Y. When moderation is mediated and mediation is moderated. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2005;89:852–863. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.89.6.852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Omoto A.M., Snyder M. Considerations of community: The context and process of volunteerism. American Behavioral Scientist. 2002;45:846–867. doi: 10.1177/0002764202045005007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Park J.H., Schaller M. Does attitude similarity serve as a heuristic cue for kinship? Evidence of an implicit cognitive association. Evolution and Human Behavior. 2005;26:158–170. doi: 10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2004.08.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Reysen S., Katzarska-Miller I. A model of global citizenship: Antecedents and outcomes. International Journal of Psychology. 2013;48:858–870. doi: 10.1080/00207594.2012.701749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reysen S., Pierce L., Spencer C.J., Katzarska-Miller I. Exploring the content of global citizen identity. The Journal of Multiculturalism in Education. 2013;9:1–31. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts B.W., Jackson J.J., Fayard J.V., Edmonds G., Meints J. In: Handbook of individual differences in social behavior. Leary M., Hoyle R., editors. Guilford Press; New York, NY: 2009. Conscientiousness; pp. 369–381. [Google Scholar]

- Rothbart M., Taylor M. In: Language, interaction, and social cognition. Semin G.R., Fiedler K., editors. Sage; Newbury Park, CA: 1992. Category labels and social reality: Do we view social categories as natural kinds? pp. 11–36. [Google Scholar]

- Różycka-Tran J. Love thy neighbor? The effects of religious in/out-group identity on social behavior. Personality and Individual Differences. 2017;115:7–12. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2016.11.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Russell G.W., Mentzel R.K. Sympathy and altruism in response to disasters. The Journal of Social Psychology. 1990;130:309–317. doi: 10.1080/00224545.1990.9924586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samuel S. How to help people during the pandemic, one Google spreadsheet at a time. Vox. 2020;16 April [Google Scholar]

- Schwalm H. Sympathy across eighteenth-century worlds: Proximity against global vision. Postcolonial Studies. 2020;23:313–329. doi: 10.1080/13688790.2020.1802110. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stürmer S., Snyder M., Kropp A., Siem B. Empathy-motivated helping: The moderating role of group membership. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2006;32:943–956. doi: 10.1177/2F0146167206287363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sudhir K., Roy S., Cherian M. Do sympathy biases induce charitable giving? The effects of advertising content. Marketing Science. 2016;35:849–869. doi: 10.1287/mksc.2016.0989. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Valdesolo P., Desteno D. Synchrony and the social tuning of compassion. Emotion. 2011;11:262–266. doi: 10.1037/a0021302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vossen H.G., Piotrowski J.T., Valkenburg P.M. Development of the adolescent measure of empathy and sympathy (AMES) Personality and Individual Differences. 2015;74:66–71. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2014.09.040. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Weisel O., Böhm R. “Ingroup love” and “outgroup hate” in intergroup conflict between natural groups. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 2015;60:110–120. doi: 10.1016/j.jesp.2015.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaki J. Catastrophe compassion: Understanding and extending prosociality under crisis. Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 2020;24:587–589. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2020.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H. Common fate motivates cooperation: The influence of risks on contributions to public goods. Journal of Economic Psychology. 2019;70:12–21. doi: 10.1016/j.joep.2018.10.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Y., Li D., Li X., Wang Y., Zhao L. Big five personality and adolescent internet addiction: The mediating role of coping style. Addictive Behaviors. 2017;64:42–48. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2016.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]