Abstract

INTRODUCTION:

Surgical skills training varies greatly between institutions and is often left to students to approach independently. Although many studies have examined single interventions of skills training, no data currently exists about the implementation of surgical skills assessment as a component of the medical student surgical curriculum. We created a technical skills competition and evaluated its effect on student surgical skill development.

METHODS:

Second-year medical students enrolled in the surgery clerkship voluntarily participated in a surgical skills competition consisting of knot tying, laparoscopic peg transfer, and laparoscopic pattern cut. Winning students were awarded dinner with the chair of surgery and a resident of their choice. Individual event times and combined times were recorded and compared for students who completed without disqualification. Disqualification included compromising cutting pattern, dropping a peg out of the field of vision, and incorrect knot tying technique. Timed performance was compared for 2 subsequent academic years using Mann-Whitney U test.

RESULTS:

Overall, 175 students competed and 71 students met qualification criteria. When compared by academic year, 2015 to 2016 students (n = 34) performed better than 2014 to 2015 students (n = 37) in pattern cut (133 s vs 167 s, p = 0.040), peg transfer (66 s vs 101 s, p < 0.001), knot tying (28 s vs 30 s, p = 0.361), and combined time (232 s vs 283 s, p = 0.009). The best time for each academic year also improved (105 s vs 110 s). Fundamentals of Laparoscopic Surgery proficiency standards for examined tasks were achieved by 70% of winning students.

CONCLUSIONS:

Implementation of an incentivized surgical skills competition improves student technical performance. Further research is needed regarding long-term benefits of surgical competitions for medical students.

Keywords: surgical education, technical skills, medical student education, surgical curriculum

INTRODUCTION

Surgical skills training for medical students is highly variable between institutions. Expectations for students varies from simple knot tying and suturing to more complex techniques and driving the laparoscopic camera to basic laparoscopic skills. Many of these skills are initially difficult for students to acquire, and no specific metrics have been developed to determine technical aptitude of medical students.1 Students have reported a gap in proficiency and desired ability upon completion of undergraduate medical training.2 Students enrolled in subinternships have reported technical skill development as one of the greatest benefits of the subinternship experience, demonstrating a desire of students to learn these skills early in their career.3 Additionally, some residency programs are now incorporating technical skill evaluations into their selection criteria for applicants, making the development of these skills even more important to students interested in pursuing surgical careers.4

Given the high expectations during the surgery clerkship including patient care, obtaining operating room experience, and mastering material for the surgical shelf examination, students are often left to learn technical skills at their own discretion without direction or specific expectations.5 As a result, learning is often conducted through means of quickly acquiring knowledge or skills through, “high yield,” resources and exercises.6 Technical skills preparation is often based on level of student interest owing to lack of specific expectations set forth formally within the clerkship. Although many institutions offer introductory knot tying courses at the beginning of their clerkship, studies have shown that single interventions to teach surgical skills do not provide long-term retention of these tasks.7

Other specialties within medical education have instituted direct learning objectives for lectures and courses to clarify student and instructor expectations.8,9 However, this practice has not been applied to skills training for students. As a portion of our clerkship, we sought to institute an optional surgical skills championship consisting of tasks deemed to be appropriate for medical students with the goal of establishing expectations for surgical skill development and ample practice time. We hypothesized that the implementation of this program would improve student performance on technical skills over time for students enrolled in the surgery clerkship.

METHODS

We introduced a surgical skills championship for medical students rotating on the general surgery clerkship at our institution. Students enrolled during the 2014 to 2015 and 2015 to 2016 academic years were evaluated while enrolled in the surgery clerkship. All students participated on a voluntary basis. The surgical skills championship consisted of 3 tasks: simple knot tying on a penrose drain, laparoscopic peg transfer, and laparoscopic pattern cut. Champions for each clerkship group were selected based on best overall time on these events. Students were considered eligible for winning the championship if they completed each task without disqualification criteria including improper knot tying technique, dropping a peg out of view during peg transfer, or compromising the pattern during laparoscopic pattern cut.

Students received demonstration and instruction from faculty and residents on how to properly perform tasks and effective ways to increase performance. This occurred in a standardized fashion for each cohort of clerkship students over 2 45-minute sessions wherein students had access to all materials used during the skills competition. Events were demonstrated for students and students were allowed to practice in the presence of residents and faculty members to receive feedback for improvements. Students were then granted 24-hour access to our Surgical Education and Activities Laboratory for the remainder of their 8-week rotation. Students were encouraged to practice independently in the Surgical Education and Activities Laboratory. Students were also told to seek out additional training from residents and faculty based on their level of interest in the competition.

Students who won the championship were incentivized with an opportunity to have dinner with the chairman of surgery, the vice chairman of surgical education, and a resident of their choice. Champions from each clerkship period were recorded and their times were posted outside of our surgical skills laboratory. Annually, all champions have been invited to an additional group dinner to track their progress since the surgical skills championship.

For the purpose of this study, times for overall completion and individual events were compared for students who completed this competition without disqualification. Students who disqualified were excluded from the study owing to the observation that these students did not attempt to complete tasks expediently after meeting disqualification status. Times were compared by academic year and plotted over time for subsequent clerkships. Time data was not available for the first two 8-week academic terms of the 2014 to 2015 academic year, but were available for the following 4 terms.

Statistical analysis was conducted using nonparametric tests to reduce the effect of outliers. Analysis was conducted in R version 3.3.0. All tests were 2-tailed. Time was treated as a continuous variable and was analyzed using the Mann-Whitney U test to compare academic years.

RESULTS

Overall, 175 students participated in the surgical skills championship over 10 sequential clerkship periods. In total, 71 students completed the surgical skills championship without disqualification; 37 students were from the 2014 to 2015 academic year, and 34 students from the 2015 to 2016 academic year. In total, 104 students disqualified on the peg transfer or laparoscopic pattern cut events.

When comparing the 2 academic years, the 2015 to 2016 academic year demonstrated statistically significant improvement in performance for laparoscopic peg transfer (101 s [2014–2015] vs 66 s [2015–2016]; p < 0.001), laparoscopic pattern cut (167 s [2014–2015] vs 133 s [2015–2016]; p = 0.040), and combined time (283 s [2014–2015] vs 232 s [2015–2016]; p = 0.009) (Table 1). Although there was improved time for knot tying, statistical significance was not reached (30 s [2014–2015] vs 28 s [2015–2016], p = 0.361). Notably, 7 of the 10 champions identified during the study period met criteria for passage of the Fundamentals of Laparoscopic Surgery testing for both time and quality metrics on the examined tasks. Best performance for each individual event and best overall time improved during the second year of the skills championship (Table 2).

TABLE 1.

Mean Student Performance by Academic Year

| 2014–2015* | 2015–2016 | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number qualifying: overall | 283 (280) | 232 (225) | 0.009 |

| Number qualifying: pattern cut | 167 (152) | 133 (127) | 0.040 |

| Number qualifying: peg transfer | 101 (97) | 66 (61) | <0.001 |

| Number qualifying: knot tying | 30 (28) | 28 (27) | 0.361 |

All times listed in seconds. Median time in parenthesis.

Times for Terms 1 and 2 in 2015 were not available.

TABLE 2.

Best Student Performance by Academic Year

| 2014–2015* | 2015–2016 | |

|---|---|---|

| Best total time | 110 | 105 |

| Best pattern cut time | 58 | 43 |

| Best peg transfer time | 45 | 27 |

| Best knot tying time | 14 | 12 |

All times listed in seconds.

Times for Terms 1 and 2 in 2015 were not available.

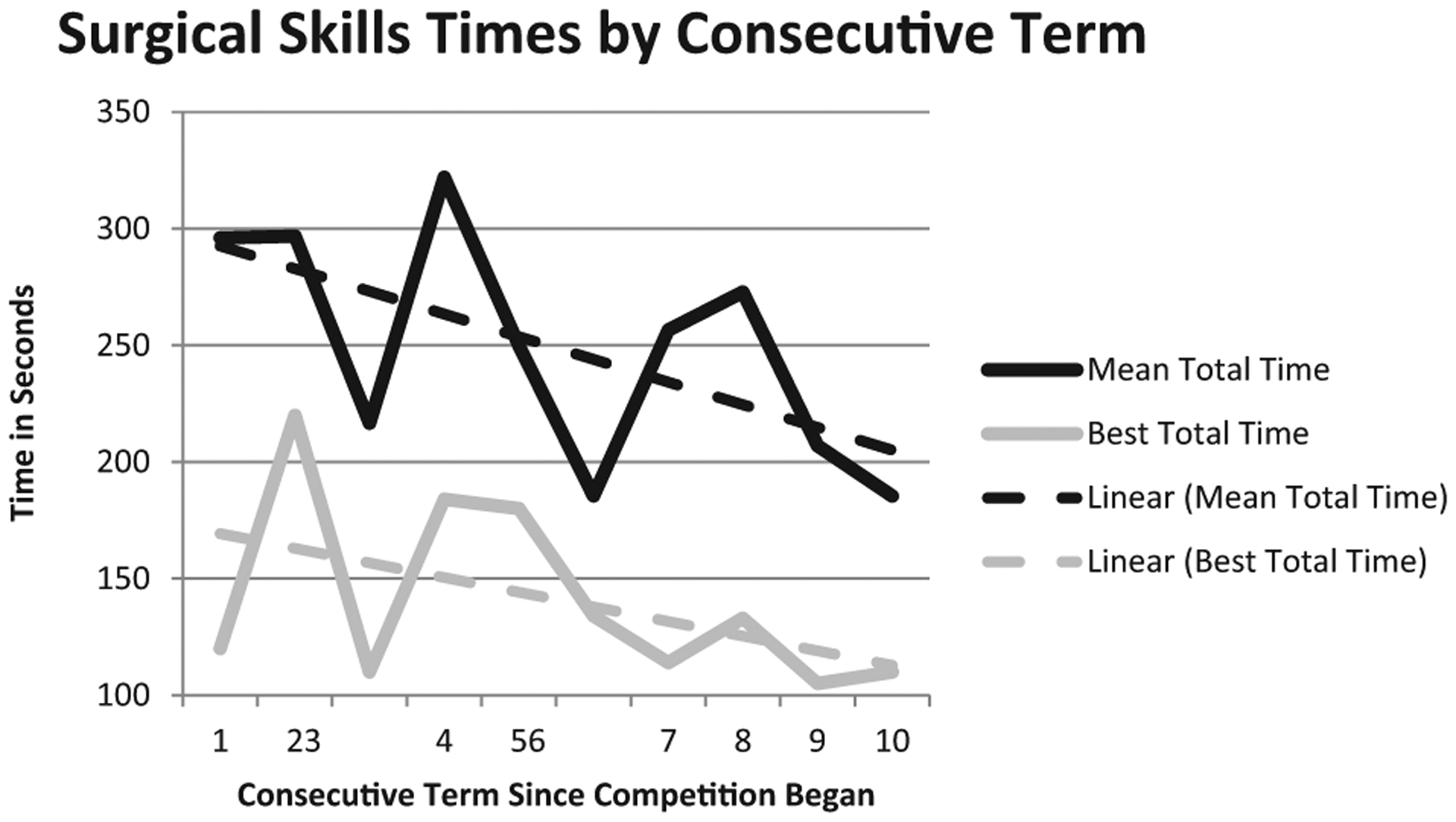

When comparing the academic years by term, statistical differences were not apparent, likely owing to the small sample sizes for each individual term (Table 3). However, it is important to note that champions for each term in the 2015 to 2016 academic year outperformed their contemporaries in the 2014 to 2015 academic year. When observed over time, there is an appreciable downward trend in completion times for individual events and overall time for students in this study (Fig.).

TABLE 3.

Best Student Performance by Term and Academic Year

| 2014–2015* | 2015–2016 | |

|---|---|---|

| Term 1 | NA | 180 |

| Term 2 | NA | 134 |

| Term 3 | 120 | 114 |

| Term 4 | 220 | 133 |

| Term 5 | 110 | 105 |

| Term 6 | 184 | 110 |

All times listed in seconds.

Times for Terms 1 and 2 in 2015 were not available.

FIGURE.

Student performance by consecutive term.

We have followed students after the competition and have acquired a limited amount of long-term data. Of the 10 students who won the competition during the study period, 7 currently plan to pursue surgical careers. A total 9 of the 10 students planned to pursue surgical careers at the time that the competition took place. Of the 2 years that are included in this study 7 of 12 students have completed surgical subinternships; 1 student completed a psychiatry subinternship, 1 internal medicine, and 2 are pursuing additional research before returning to the wards. Of all 2 of the 6 champions from the 2014 to 2015 academic year have matriculated to general surgery residency programs, 1 pursued residency in psychiatry, the remaining 3 took additional research time and are returning to the wards this year before applying to residency programs.

DISCUSSION

This study demonstrates that establishing a surgical skills championship with clear expectations for medical students improves student performance in technical skills tasks over time. We demonstrated improved performance in the second year of the skill championship for 2 of 3 individual events and overall time. Specifically, laparoscopic peg transfer and laparoscopic pattern cut showed significant improvement, whereas simple knot tying did not. We believe that this difference is observable in the 2 laparoscopic events because the tasks consume a greater amount of time and there is much greater room for improvement in these events, whereas the observable difference in student knot tying time is likely very small, given that this is a faster task, and one that is much easier to master. It is also possible that students found the laparoscopic tasks more engaging during their independent practice time, and sought to spend more time on these tasks. Additionally, this study showed performance improved in the second year of competition in every academic term relative to the previous year, suggesting that students continually sought to beat established time records.

Technical skill development in medical students remains an active area of investigation. Siska et al.12 have recently described factors associated with improved laparoscopic training in medical students enrolled in a technical skills curriculum. They identified that voluntary practice time and an interest in a surgical career were likely to increase technical skills performance. This is consistent with our study in which the high proportion of the champions intended to pursue careers in surgery. Martin et al.13 enrolled medical students in a technical skills curriculum over a 10 to 15-hour course to examine factors associated with technical skill development. They successfully identified that female students had high-baseline technical proficiency; however, at the end of the study period, higher confidence and male sex were associated with significant improvement. Other studies have refuted the role of sex in skills acquisition.14,15 Although our study did not aim to examine the influence of sex on surgical technical skills, 83% of champions in the first 2 academic years of this program have been male suggesting an interesting subject for future work.

Stone et al.10 reported survey responses from 72 graduating medical students showing that of the situations wherein students felt mistreated, content mastery and technical performance in the operating room were often focal points of criticism. Although these situations likely involved multiple reasons for escalation, thorough skills training potentially help mitigate these focal points and help students feel more competent in tasks such as suturing or camera manipulation. We hypothesize that providing clear expectation of student practice will improve student comfort with expected tasks and surgical equipment, thereby improving their perception by both residents and faculty. This will also provide appropriate benchmarks for critique in the operating room by providing faculty with an understanding of tasks that students are expected to be able to perform and instruments that they should be able to identify. Additionally, this program provides students with realistic expectations of the demands that they may encounter later in their careers as they attempt to master operative skills and demonstrate proficiency with new equipment, while showcasing their dedication and abilities to departmental leadership.

Gawad et al. have reported that students with directed instruction for laparoscopic tasks perform better than students who simply study and work independently to improve task performance.11 We believe that faculty and residents providing guided demonstration and feedback provides this benefit to students enrolled in our clerkship. We have noted in our review of this study that many residents have embraced this competition as a means of training students on their services. Student selection of residents to accompany them for dinner with our chairman and vice chair of education showed that a small cadre of residents placed high emphasis on training students. One resident in particular was invited on 3 separate occasions. Previous studies have demonstrated medical students are often motivated to pursue careers in surgery based on availability of strong mentors and engagement of residents in active teaching.16–19 This competition may allow for the formation of these relationships by demonstration of a shared interest. Additionally, this competition allows residents to showcase their involvement in student education to department leadership.

Several students who won the skills championship have taken on leadership roles in our surgical interest groups. Their efforts as a group have focused on improving anatomical teaching and skills training for preclinical year students. Previous studies have listed the merits of an active surgery interest group and department led skills training including increased matriculation of students into surgical programs.20–22 Since instituting the competition, we have seen the number of applicants in general surgery rise dramatically during the study period. The year before study implementation, 1e student applied into residency programs in general surgery. The first year of students to participate in the skills championship saw 6 students apply to general surgery residency programs. In the upcoming academic year we will have 15 students enrolled in general surgery subinternships, but at this time we are unable to predict how many will pursue residencies in general surgery. The increase in student interest is certainly multifactorial, however, we believe that the skills championship has helped to create a culture within the medical school that is more embracing of surgical careers.

This study is limited by its retrospective review of student data. Although our initial goal was to evaluate student performance, we were unable to evaluate student motivation, training patterns including amount of time spent in the skill lab and frequency of training, level of coaching, and academic performance. The strong improvement in student performance naturally raises the question of whether or not students were spending more time practicing for this competition. Further examination is required to reliably correlate this trend in our subjects. Although instruction provided through the clerkship remained consistent, subjects in the later cohorts likely experienced more excitement for the possible prize of winning and further advice based on the experience of previous students. It is likely that students began to dedicate more time to practicing as the tinning times continued to improve, and students sought to beat established records. In addition, more effective coaching and guidance from previous students was likely a contributing factor to improvement in student times in later cohorts. We believe that student performance changes may also be influenced by the Hawthorne effect as students knew they would be evaluated, and were able to view the times of other students who had previously won the competition. However, this was likely beneficial in providing a relative benchmark of success for students aspiring to win the competition. Finally, some argue that Fundamentals of Laparoscopic Surgery tasks including pattern cut and peg transfer are not tools ideal for trainees given their focus on time over precision and safety.23 However, in the initial stages of training, these tasks can increase comfort with instruments and spatial awareness allowing for later development of refined technique.

Despite these limitations, this study provides strong evidence for the benefits of an incentivized surgical skills competition for medical students enrolled in the surgery clerkship. Our demonstration of consistent improvement over the course of 10 consecutive academic terms demonstrates the benefit of instituting a formal evaluation of student technical skills. This intervention allows motivated students the ability to showcase their work on technical training and build a relationship with the department leadership. It also allows the department of surgery an opportunity to identify eager students early in their training process. As we continue to study this intervention, we will examine the amount of time spent practicing by students, demographic factors, and other clerkship performance factors associated with high performers on these surgical tasks.

In conclusion, implementation of a surgical skills championship for clerkship medical students improves student technical performance and interest in surgery over time. We would recommend that other institutions consider adopting this program in order to provide students an opportunity to self-identify their interest and capability for a careers in surgery, find resident mentors, and experience individual mentorship from departmental leadership. Future examination is necessary to determine the motivation of students who win the skills championship and to evaluate the long-term trajectory of their careers.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We would like to extend our gratitude to our Chairman, Dr. Allan Kirk, for his continued support of the surgical skills championship for Duke medical students. We would also like to thank our clerkship director, Dr. John Haney, for the inclusion of this program in our clerkship curriculum. Additionally, we are greatly indebted to the dutiful work of Jennie Phillips and Layla Triplett who organize this competition and record student data to better track student development and improve simulation based education through our Surgical Education and Activities Laboratory.

Footnotes

Additional Disclosures: These data were presented as a poster presentation at the 10th Annual American College of Surgeons Accredited Education Institutes Conference in Chicago, IL on March 16th, 2017.

REFERENCES

- 1.Louridas M, Szasz P, de Montbrun S, Harris KA, Grantcharov TP. Can we predict technical aptitude?: A systematic review. Ann Surg. 2016;263(4):673–691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dehmer JJ, Amos KD, Farrell TM, Meyer AA, Newton WP, Meyers MO. Competence and confidence with basic procedural skills: the experience and opinions of fourth-year medical students at a single institution. Acad Med. 2013;88(5):682–687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lindeman BM, Lipsett PA, Alseidi A, Lidor AO. Medical student subinternships in surgery: characterization and needs assessment. Am J Surg. 2013;205 (2):175–181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gardner AK, Steffes CP, Nepomnayshy D, et al. Selection bias: Examining the feasibility, utility, and participant receptivity to incorporating simulation into the general surgery residency selection process. Am J Surg. 2017;213(6):1171–1177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lyons-Warren AM, Kirby JP, Larsen DP. Student views on the role of self-regulated learning in a surgery clerkship. J Surg Res. 2016;206(2):273–279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lin JA, Farrow N, Lindeman BM, Lidor AO. Impact of near-peer teaching rounds on student satisfaction in the basic surgical clerkship. Am J Surg. 2016;213(6): 1163–1165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Routt E, Mansouri Y, de Moll EH, Bernstein DM, Bernardo SG, Levitt J. Teaching the simple suture to medical students for long-term retention of skill. J Am Med Assoc Dermatol. 2015;151(7):761–765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brodkey AC, Sierles FS, Woodard JL. Use of clerkship learning objectives by members of the Association of Directors of Medical Student Education in Psychiatry. Acad Psychiatry. 2006;30(2):150–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Erickson SS, Metheny WP, Cox SM, et al. A comprehensive review to establish priority learning objectives for medical students in the obstetrics and gynecology clerkship. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;199(5) 563.e1–563.e9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stone JP, Charette JH, McPhalen DF, Temple-Oberle C. Under the knife: medical student perceptions of intimidation and mistreatment. J Surg Educ. 2015;72(4):749–753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gawad N, Zevin B, Bonrath EM, Dedy NJ, Louridas M, Grantcharov TP. Introduction of a comprehensive training curriculum in laparoscopic surgery for medical students: a randomized trial. Surgery. 2014;156(3):698–706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Siska VB, Ann L, Gunter de W, et al. Surgical Skill: trick or trait? J Surg Educ. 2015;72(6):1247–1253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Martin AN, Hu Y, Le IA, et al. Predicting surgical skill acquisition in preclinical medical students. Am J Surg. 2016;212(4):596–601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.White MT, Welch K. Does gender predict performance of novices undergoing Fundamentals of Laparoscopic Surgery (FLS) training? Am J Surg. 2012;203(3): 397–400 [discussion 400]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kolozsvari NO, Andalib A, Kaneva P, et al. Sex is not everything: the role of gender in early performance of a fundamental laparoscopic skill. Surg Endosc. 2011;25 (4):1037–1042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Barshes NR, Vavra AK, Miller A, Brunicardi FC, Goss JA, Sweeney JF. General surgery as a career: a contemporary review of factors central to medical student specialty choice. J Am Coll Surg. 2004;199(5):792–799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Taylor JA, Shaw CM, Tan SA, Falcone JL. Are the kids alright? Review books and the internet as the most common study resources for the general surgery clerkship. Am J Surg. 2017; Published Online. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Marshall DC, Salciccioli JD, Walton SJ, Pitkin J, Shalhoub J, Malietzis G. Medical student experience in surgery influences their career choices: a systematic review of the literature. J Surg Educ. 2015;72(3): 438–445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kirkham JC, Widmann WD, Leddy D, et al. Medical student entry into general surgery increases with early exposure to surgery and to surgeons. Curr Surg. 2006;63(6):397–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Salna M, Sia T, Curtis G, Leddy D, Widmann WD. Sustained increased entry of medical students into surgical careers: a student-led approach. J Surg Educ. 2016;73(1):151–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li R, Buxey K, Ashrafi A, Drummond KJ. Assessment of the role of a student-led surgical interest group in surgical education. J Surg Educ. 2013;70(1):55–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Patel MS, Mowlds DS, Khalsa B, et al. Early intervention to promote medical student interest in surgery and the surgical subspecialties. J Surg Educ. 2013;70(1):81–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kowalewski TM, White LW, Lendvay TS, et al. Beyond task time: automated measurement augments fundamentals of laparoscopic skills methodology. J Surg Res. 2014;192(2):329–338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]