Abstract

During pandemics such as COVID-19, voluntary self-isolation is important for limiting the spread of infection. Little is known about the traits that predict distress or coping with pandemic-related self-isolation. Some studies suggest that personality variables (e.g., introversion, conscientiousness, resilience, optimism) are important in predicting distress and coping during self-isolation, but such studies have not controlled for important variables such as stressors associated with self-isolation, demographic variables, and individual differences in beliefs (worries) about the dangerousness of COVID-19. The present study is, to our knowledge, the first to investigate the role of personality traits, demographic characteristics, and COVID-related beliefs about contracting the coronavirus. Data from a population representative sample of 938 adults from the United States and Canada, in voluntary self-isolation, revealed that COVID-related threat beliefs were more important than various personality variables in predicting (a) self-isolation distress, (b) general distress, (c) stockpiling behaviors, and (c) use of personal protective equipment such as masks, gloves, and visors. There was little evidence that personality traits influenced threat beliefs. The findings are relevant for understanding distress and protective behaviors during the current pandemic, in subsequent waves of this pandemic, and in later pandemics, and for informing the development of targeted mental health interventions.

Keywords: COVID-19, Pandemic, Coping, Personality traits, COVID stress syndrome, Personal protective equipment, Panic buying

1. Introduction

Voluntary self-isolation, which is a pandemic-containment social-distancing intervention, poses its own special challenges. Negative reactions such as boredom, irritability, and anxiety are not uncommon, often arising in the context of self-isolation stressors, such as cramped living conditions and difficulties working from home while simultaneously caring for children (Taylor, 2019; Taylor et al., 2020b). Little is known about the predictors of pandemic-related distress and coping during voluntary self-isolation. Accordingly, this was the focus of the present study, which was conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic. This research builds on our previous research on the COVID Stress Syndrome (CSS; Taylor, 2021; Taylor et al., 2020a, Taylor et al., 2020b), which provides evidence of a CSS, at the core of which are threat-related beliefs about COVID-19. Three sets of intercorrelated CSS threat beliefs were identified: (a) Beliefs about the dangerousness of becoming infected with SARSCoV2, combined with concerns about coming into contact with objects or surfaces that might be infected with the virus; (b) concerns about the socio-economic consequences of COVID-19 (e.g., job loss, financial difficulties); and (c) xenophobic concerns that foreigners are spreading COVID-19. These beliefs, taken together, are correlated with pandemic-related distress, pre-existing psychopathology, avoidance behaviors, panic buying, and difficulty coping with voluntary self-isolation (Taylor et al., 2020b).

The present study extends the research on pandemic-related self-isolation by investigating how the CSS threat beliefs compare with personality variables in predicting distress and coping during voluntary self-isolation. Self-isolation was not total; that is, participants were permitted by their governments or communities to go outside, but they were encouraged to stay home as much as possible. Four dependent variables measuring distress and coping were examined: (a) Distress specific to voluntary self-isolation, (b) general (past week) distress, (c) the use of personal protective equipment when venturing outside of self-isolation quarters, and (d) pre-isolation stockpiling (panic buying) of food, medicines, and sanitary supplies.

Personality traits examined in this study were based on a review of the literature on pandemic coping and on coping with isolated, confined environments. Previous relevant studies have focused mostly on the Big 5 personality traits (Costa & McCrae, 1992; Digman, 1990), which consist of the following: Extraversion (the tendency to be sociable and outgoing), agreeableness (the tendency to be warm, friendly, and trusting), conscientiousness (the tendency to be organized and reliable), negative emotionality (the tendency to readily experience negative emotions), and openness (the tendency to be curious, creative, and open to new experiences). In addition, trait optimism and trait resilience were investigated in the present study, due to their previously established links to good coping during previous pandemics and outbreaks (Taylor, 2019).

Several studies have investigated the predictors of who copes well in isolated, confined environments (e.g., studies of submariners, studies of spaceflight simulation training programs). A review of this literature (Bartone et al., 2018) indicates that people tend to cope better with isolation and confinement if they possess the following personality traits: Low levels of negative emotionality, low levels of extraversion, and high levels of openness, optimism, and resilience. It is unclear whether these findings generalize to pandemic-related self-isolation because confinement is not total and people can still maintain high levels of social contact via social media, text messaging, and other electronic means.

Published studies during COVID-19 provide mixed and somewhat inconsistent results about the relationship between personality traits and COVID-related distress and coping. Some studies suggest that negative emotionality is correlated with pandemic-related general distress (Somma et al., 2020); that is, distress that is not limited to the distress experienced during self-isolation. Conscientiousness has been correlated with panic buying of toilet paper (Garbe et al., 2020). Adherence to social distancing has been predicted by low extraversion and high conscientiousness in some research (Carvalho et al., 2020), but this was not replicated in other research (Zajenkowski et al., 2020). Agreeableness predicted adherence to social distancing in some research (Zajenkowski et al., 2020), but was not replicated in other research (Abdelrahman, 2020). For those predictors that were statistically significant, effect sizes were generally not reported, and so it is difficult to gauge the magnitude of effects.

The reliability (replicability) of the above-mentioned findings during COVID-related self-isolation remain in question, and it is unclear how personality traits compare to CSS threat beliefs in their predictive power specifically with regard to coping with self-isolation. Research into personality traits and threat beliefs as predictors of distress and coping can provide leads about interventions (e.g., resiliency-boosting programs or particular types of cognitive-behavioral interventions). In the present study, CSS threat beliefs and personality traits were treated as distinct predictors of distress and coping. Although some personality traits (e.g., negative emotionality) could conceivably play a causal role in shaping CSS threat beliefs, there is very little relationship between these beliefs and personality variables, as shown later in this article. Instead of simply identifying statistically significant predictors, the focus of the investigation was on the effect sizes of significant effects, in order to determine their relative importance.

2. Method

2.1. Sample and data collection procedures

Data were collected during May 6–19, 2020, from a population-representative sample of 938 adults who were in pandemic-related voluntary self-isolation in the United States (n = 498) and Canada (n = 440). Voluntary self-isolation involved staying at home as much as feasibly possible, with outings limited to essential activities such as grocery shopping or going to work if the person was employed in a job deemed to be an essential service (e.g., grocery store worker). Data were collected using an internet-based self-report survey delivered in English by Qualtrics, a commercial survey sampling and administration company. All respondents provided written informed consent. Sample mean age was 52 years (SD = 16 years). Approximately half (51%) were female, most (92%) were employed full- or part-time, and most (85%) had completed full or partial college education. Most (69%) were Caucasian, with the remainder being Asian (11%), African American/Black (8%), Latino/Hispanic (8%), or other (4%). Half (50%) reported having a pre-existing (i.e., pre-COVID-19) medical condition, and 22% reported having a current (past year) mental health condition. At the time of assessment, participants had been in voluntary self-isolation for a mean of 49 days (SD = 19 days). Only 3% of the sample reported that they had been diagnosed with COVID-19, and only 3% were healthcare workers who might come into contact with patients infected with SARS-CoV2. Given the low percentage of healthcare workers and COVID-19 diagnosed cases, these variables were not examined in the regression analyses of the present study. Almost all (93%) respondents reported being at least moderately or more compliant with self-isolation, so predictors of compliance were not assessed in this study. Similarly, handwashing was not examined because virtually all respondents reported that they were engaging in regular handwashing.

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Assessment battery

Participants completed a battery of measures, including a measure of demographic variables, background variables (e.g., number of days in self-isolation), and various other measures described below. Candidate predictor variables included (a) the Big 5 personality dimensions (extraversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness, negative emotionality, and openness), (b) optimism, (c) resilience, (d) the measures of COVID-related threat beliefs from the COVID Stress Scales (Taylor et al., 2020a), and (e) demographic and other background variables. Dependent variables were (a) distress specific to voluntary self-isolation, (b) general (past week) distress, (c) use of personal protective equipment (PPE), and (d) pre-isolation stockpiling behaviors. Details appear below.

For each multi-item scale, McDonald's (1999) ω total, which is a commonly used alternative to Cronbach's α, was used as the measure of reliability as internal consistency. McDonald's ω was used instead of Cronbach's α because the latter tends to underestimate reliability (McNeish, 2018). Values of ω are interpreted in the same way as α; that is, values in the range of 0.70–0.80 indicate acceptable reliability, 0.80–0.90 are good, and values greater than 0.90 are excellent.

2.2.2. Candidate predictor variables

The Big 5 personality dimensions were assessed by the Ten Item Personality Inventory (TIPI; Gosling et al., 2003). Despite being a very brief measure, it has performed well on various indices of reliability and validity (e.g., Ehrhart et al., 2009; Gosling et al., 2003; Nunes et al., 2018). In the present study, the TIPI scales had acceptable-to-good levels of reliability, as indicated by the ω values for each scale: Extraversion 0.86, agreeableness 0.78, conscientiousness 0.83, negative emotionality 0.88, and openness 0.77.

Trait optimism was measured by the Optimism Scale (Coelho et al., 2018), which has been previously shown to have good reliability and validity (Coelho et al., 2018), and in the present study had excellent reliability (ω = 0.94). Trait resilience was assessed by the Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (Connor & Davidson, 2003), which has good psychometric properties (Connor and Davidson, 2003, Connor and Davidson, 2020), and excellent reliability in the present study (ω = 0.94).

COVID-related threat beliefs included worries (past week) about the dangerousness of COVID-19, worries about coming into contact with fomites (i.e., objects or surfaces potentially contaminated with the SARS-CoV2 virus), worries about the personal socio-economic consequences of COVID-19 (e.g., job loss), and xenophobic worries (i.e., worries that the virus is being spread by foreigners). These beliefs were assessed by the COVID Stress Scales (Taylor et al., 2020a), which is a psychometrically sound inventory of COVID-19-related distress. Evidence indicates that COVID Stress Scales assess the CSS, at the core of which are the COVID-related beliefs assessed in this study (see Taylor et al., 2020a, Taylor et al., 2020b, for details). In the present study, the reliability of the measure of CSS beliefs was excellent (ω = 0.97).

The above-mentioned threat beliefs and personality traits were the main predictors examined in this study. To evaluate their comparative predictive value, we also included a number of demographic and other background variables as candidate predictors. In part, this was done to address potential contributing variables to self-isolation distress (e.g., stressors encountered during self-isolation) and to control for potentially confounding variables (e.g., number of days in self-isolation). These candidate predictors were female gender (1 = yes, 0 = no), age, ethnic minority status (1 = yes, 0 = no), unemployed (1 = yes, 0 = no), college education (1 = yes, 0 = no), current (past year) mental health condition (1 = yes, 0 = no), pre-existing medical condition (1 = yes, 0 = no), number of days in self-isolation, and self-isolation stressors. The latter was assessed by a 15-item face-valid scale developed in our previous research (Taylor et al., 2020b), that assessed whether the person had experienced any of a range of stressors during self-isolation (e.g., running low on food or prescription medicines, financial problems, cramped living conditions, difficulty taking care of children or other loved ones). The reliability of this scale was good (ω = 0.85). Country (United States vs. Canada) was not included as a predictor variable because it was confounded with minority status.

2.2.3. Dependent variables

Pre-isolation stockpiling behavior was assessed by a 7-item face-valid scale (Taylor et al., 2020b), which assessed whether respondents had stockpiled a large amount (i.e., more than a two-week supply) of various things such as food, toiletries, prescription medicines, cleaning supplies and so-forth. In the present study, the reliability of this scale was good (ω = 0.87). The use of PPE was assessed by a 6-item face-valid scale designed for the present study (ω = 0.87) in which respondents assessed the frequency with which they wore gloves, facemasks, or protective visors either as part of their job or in their non-working lives.

Distress specific to voluntary self-isolation was assessed by a 7-item face-valid scale developed in our previous research (Taylor et al., 2020b) assessing various aspects of distress (e.g., loneliness, boredom, anxiety, irritability) associated with self-isolation. In the present study, this scale had excellent reliability (ω = 0.92). General distress (depression and anxiety) during the past week was assessed by the Patient Health Questionnaire-4, which has been shown to have good psychometric properties (Kroenke et al., 2009) and had excellent reliability in the present study (ω = 0.93).

2.3. Statistical procedures

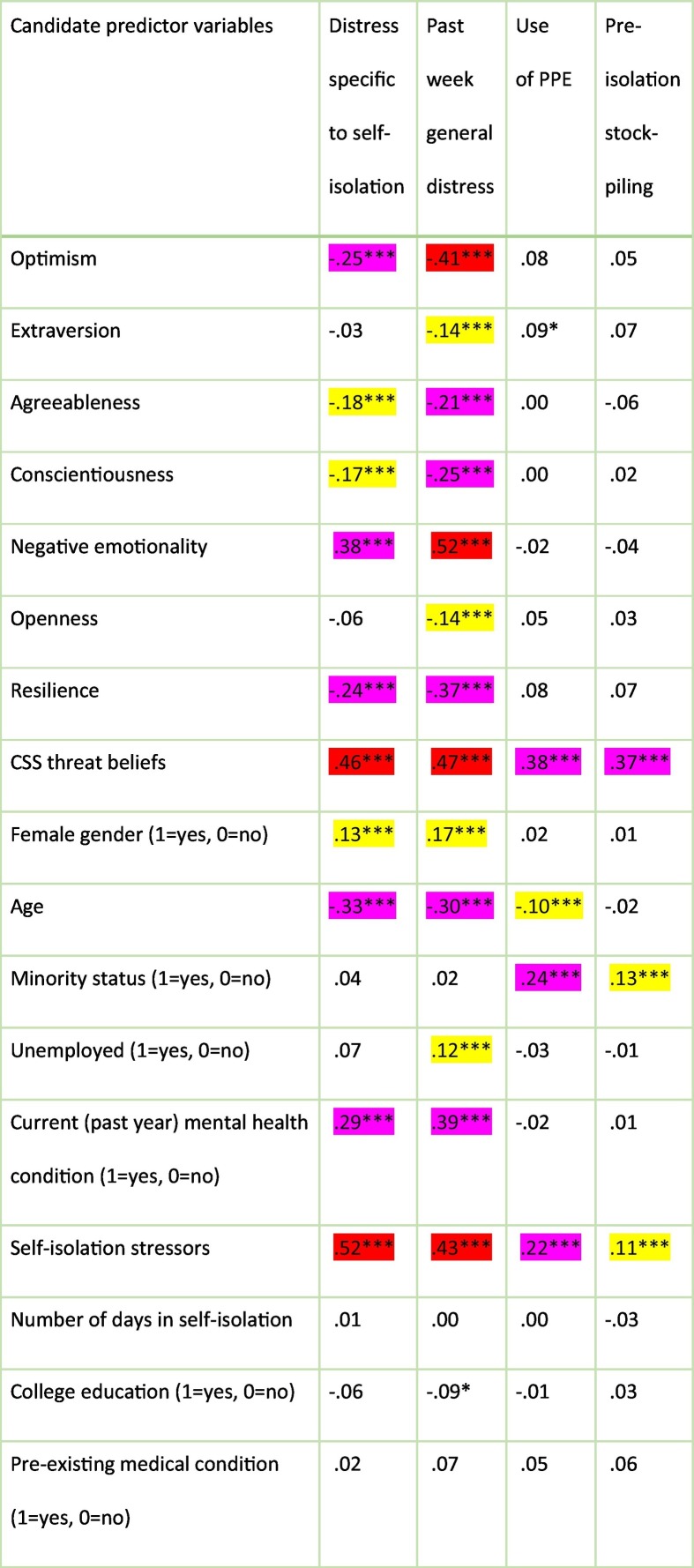

Correlation analyses were conducted for descriptive purposes and to identify candidate predictor variables that could be excluded from the main (regression) analyses. Candidate predictors were excluded if their correlations with the dependent variables were below Cohen's (1988) criterion for a “small” correlation (see below). The main analyses were four regression analyses, one for each of the following dependent variables: Distress specific to self-isolation, past week general distress, use of PPE, and pre-isolation stock-piling. The candidate predictor variables are listed in Table 1 .

Table 1.

Predictors of distress and coping behaviors: Correlations between candidate predictor variables (first column) and dependent variables (remaining columns).

CSS beliefs = Threat-related beliefs associated with the COVID Stress Syndrome.

PPE = Personal protective equipment. Classification of effect sizes: Yellow = small, pink = medium, red = large. *p < .01, **p < .005, ***p < .001.

Tolerance values were calculated to test for multicollinearity among predictors in regression analyses. Tolerance values <0.10 are considered to be problematic, indicating multicollinearity among predictors (Tabachnick & Fidell, 2019). Given the number of analyses reported in this article, the α level for Type I error was set at 0.01 instead of the conventional 0.05. This adjustment corrects for inflated Type I error without unduly inflating Type II error with a more stringent correction, such as a Bonferroni correction.

Given the large sample size, substantively trivial effect sizes would be statistically significant (e.g., for r = 0.10, p < .001). Accordingly, to facilitate the interpretation of correlations, we used Cohen's (1988) criteria to classify effect sizes as small (r = 0.10), medium (r = 0.30), or large (r = 0.50). To give precision to these classifications for rs falling between the numbers, we classified r in terms of ranges, using the midpoint between 0.10 and 0.30, and midpoint between 0.30 and 0.50, so as to distinguish among small, medium, and large rs; that is, small 0.10–0.19, medium 0.20–0.39, and large >0.39.

For each regression equation, the overall effect size (magnitude of R2) was interpreted by converting it to f2, defined as R2/(1-R2) (Cohen, 1988). For each predictor variable in a given regression analysis, the effect size was fB/A 2. This was defined as (RAB 2 - RA 2)/(1 - RAB 2), which assesses the incremental effect in the regression equation when a given predictor (variable B) is added to a group of predictors (a group of A variables; Cohen, 1988). The magnitude of f2 and fB/A 2 values has been classified as follows: Small 0.02, medium 0.15, large 0.35 (Cohen, 1988). To give precision to these classifications for values falling between the numbers, we classified f2 and fB/A 2 in terms of ranges, using the midpoint between 0.02 and 0.15, and midpoint between 0.15 and 0.35, so as to distinguish among small, medium, and large effects; that is, small 0.020–0.085, medium 0.086–0.250, and large >0.250. Values below 0.02 were considered to be substantively trivial.

3. Results

Table 1 shows the correlations between candidate predictor variables and dependent variables. Most predictor variables had at least small correlations with the dependent variables (according to Cohen's criterion), although three variables had correlations below the cut-off for “small” and so were not included in the subsequent regression analyses: College education, pre-existing medical condition, and number of days in self-isolation.

With regard to the bigger effect sizes (medium and large correlations), Table 1 shows that CSS beliefs had consistently strong correlations with distress (past week and specific to self-isolation), use of PPE, and pre-isolation stockpiling. Greater distress had medium or large correlations with lower optimism, lower resilience, younger age, higher levels of negative emotionality, higher levels of self-isolation stressors, and the presence of a current (past year) mental health condition.

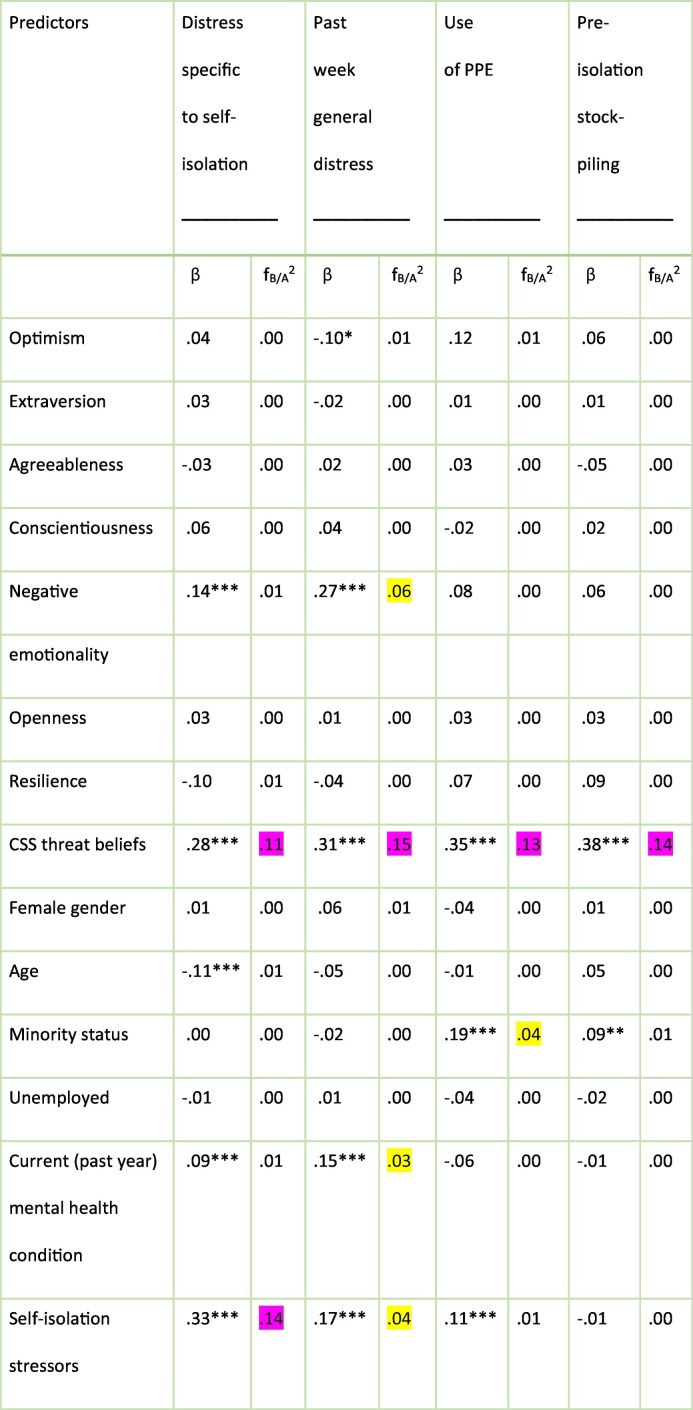

Table 2 summarizes the results of the four regression analyses. For each analysis the tolerance values were >0.33, indicating that multicollinearity was not a concern. The overall results for each of the regression analyses were as follows: Distress specific to self-isolation, F(14, 917) = 48.08, p < .001, R2 = 0.42, f2 = 0.72 (large effect); past-week general distress, F(14, 917) = 61.51, p < .001, R2 = 0.48, f2 = 0.92 (large effect); use of PPE, F(14, 913) = 19.05, p < .001, R2 = 0.23, f2 = 0.30 (large effect); and pre-isolation stockpiling, F(14, 917) = 13.14, p < .001, R2 = 0.17, f2 = 0.20 (medium effect).

Table 2.

Regression analyses: Beta weights (β) and effect sizes (fB/A2) for predictors (first column) and dependent variables (remaining columns).

CSS = COVID Stress Syndrome. PPE = Personal protective equipment. Classification of.

effect sizes (f2): Yellow = small, pink = medium, red = large. *p < .01, **p < .005, ***p < .001.

Table 2 shows a consistent pattern of results. For all dependent variables, CSS beliefs were a consistently significant predictor, with medium effects sizes. Not surprisingly, the number of self-isolation stressors encountered by a person was predictive of the degree of self-isolation distress (medium effect size). All of the other variables had either inconsistent or trivially small effects. In other words, the most important predictor of distress and coping was CSS threat beliefs, and these beliefs in combination with self-isolation stressors were the strongest predictors of self-isolation distress. Personality traits had small or trivial effects as predictors of distress and coping, once CSS beliefs were taken into consideration.

When interpreting the results in Table 2, the question arises as to whether some personality traits were causes of CSS beliefs. That is, it is possible that personality traits might have influenced distress and coping via their effects on CSS beliefs. To explore this possibility, a regression analysis was conducted in which the personality traits were entered as predictors of CSS beliefs. Tolerance values were >0.34. For the overall regression, F(7, 925) = 9.05, p < .001, R2 = 0.06, f2 = 0.06 (small effect). For each predictor, β and fB/A 2 were as follows: Optimism −0.11, 0.00; extraversion 0.09, 0.01; agreeableness −0.03, 0.01; conscientiousness 0.01, 0.00; negative emotionality 0.19 (p < .001), 0.02; openness −0.02, 0.00; and resilience 0.04, 0.02. Thus, only one predictor—negative emotionality—was statistically significant, but its effect size was at the lower limit of the classification of a small effect. The correlation between CSS beliefs and negative emotionality was 0.23, indicating that there was only 5% shared variance between the two variables. If negative emotionality had any causal influence on CSS beliefs, such an effect was very small.

4. Discussion

The present study focused on a period during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic in which people in America and Canada were asked to voluntarily self-isolate. By the time the present research is published, the self-isolation mandate may be over, but the results will be relevant for second and possibly even further waves of COVID-19 and subsequent other pandemic infections. Consistent with previous research, we found that various personality traits were correlated with measures of pandemic-related distress and coping. Garbe et al. (2020) found that conscientiousness was correlated with panic buying. This finding was not reliable (replicable) in the present study. Moreover, the results indicated that CSS threat beliefs were the strongest, most consistent predictors of pandemic-related distress and coping. Those beliefs include concerns about the personal health threat of COVID-19, concerns about the socio-economic impacts of COVID-19, and xenophobic concerns that foreigners are spreading COVID-19. These threat beliefs form the core of the COVID Stress Syndrome, as described in previous research (Taylor et al., 2020a, Taylor et al., 2020b). The findings of the present study are also consistent with well-established findings from the general literature on stress and coping, in which threat appraisals are particularly important drivers of distress and coping (e.g., Lazarus, 1991).

The present findings are consistent with some of the findings concerning the predictors of successful coping with isolated, confined environments (Bartone et al., 2018). Consistent with this research, we found that distress associated with self-isolation was positively correlated with negative emotionality, and negatively associated with optimism and resilience. However, those variables were weak or nonsignificant predictors of isolation-related distress once CSS beliefs were taken into consideration. We also did not replicate the findings (Bartone et al., 2018) that openness and introversion are associated with low distress. This may reflect the fact that the isolated, confined environments in previous studies (e.g., submariners) are different in important ways from pandemic-related voluntary self-isolation. For the latter, the majority of people have ready access to various forms of social communication and social support, including text messaging and social media. Accordingly, extroverted people are readily able to maintain their social contacts during the pandemic and, therefore, introversion provides no special protection against isolation-related distress.

Since completing this investigation, another study has emerged yielding consistent findings. Abdelrahman (2020) conducted a regression analysis predicting adherence to social distancing from the Big 5 traits and a single-item measure of disease severity (“How do you rate the danger of COVID-19 disease?”). Personality traits were nonsignificant predictors (p > .01), whereas disease severity was significant (p < .001). Again, this highlights the importance of threat beliefs over personality in understanding pandemic-related coping behaviors.

The findings of the present study must be interpreted in light of three important limitations that need to be addressed in future research. First, it was necessary to develop new scales to measure the variables of interest (e.g., use of PPE), because previously validated measures were not available. Our measures were face valid and had acceptable reliability (as measured by ω), but nevertheless future studies using alternative measures are needed to determine the replicability of the findings. The second limitation was the non-exhaustive assessment of dependent variables. That is, we focused on two, readily measurable, protective or coping behaviors—stockpiling and the use of PPE. Although we collected data on hand hygiene and compliance with self-isolation, these were not included in the regression analyses because the majority of participants reported engaging in regular hand hygiene and were reportedly compliant with voluntary self-isolation. At the time of conducting the study, the mean duration of self-isolation was 49 days (SD = 19 days). Compliance might become a problem with increasingly longer periods of self-isolation, although this remains to be demonstrated. Nevertheless, in future studies where there are long periods of self-isolation (e.g., several months), it may be important to investigate predictors of noncompliance. The third limitation of the present study concerns its cross-sectional design. We investigated statistical predictors (via regression analyses), which does not establish causality.

Despite these limitations, the findings have a number of public health implications. Subsequent studies, including those using cognitive-behavioral therapy for health anxiety (Taylor & Asmundson, 2004) to treat extreme (maladaptive) beliefs about the dangerousness of COVID-19, can be conducted to determine whether belief modification therapies reduce pandemic-related stress and socially disruptive behaviors. In conducting such studies, it would be important to investigate whether the therapies have adverse effects, such as reducing the use of PPE, especially given that CSS beliefs were statistical predictors of the use of PPE in the current study. Subsequent studies are also required to better understand noncompliance with public health orders, such as practicing social isolation, and the factors predicting such behaviors. Recognition and better understanding of how pandemic-related distress shapes desirable and disruptive behavior will aid policy makers in tailoring evidence-based communication strategies that facilitate mitigation of infection and direct mental health practitioners to the most appropriate targets for tailored mental health interventions.

Funding

Canadian Institutes of Health Research (#439751) and the University of Regina (Gordon J. G. Asmundson PI; Steven Taylor Co-PI).

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Steven Taylor: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. Michelle M. Paluszek: Methodology, Data curation, Project administration, Writing – review & editing. Caeleigh A. Landry: Methodology, Data curation, Project administration, Writing – review & editing. Geoffrey S. Rachor: Methodology, Data curation, Project administration, Writing – review & editing. Gordon J.G. Asmundson: Funding acquisition, Methodology, Writing – review & editing.

References

- Abdelrahman M. Personality traits, risk perception, and protective behaviors of Arab residents of Qatar during the covid-19 pandemic. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction. 2020:1–12. doi: 10.1007/s11469-020-00352-7. Advance online publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartone P.T., Krueger G.P., Bartone J.V. Individual differences in adaptability to isolated, confined, and extreme environments. Aerospace Medicine and Human Performance. 2018;89:536–546. doi: 10.3357/AMHP.4951.2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carvalho L.F., Pianowski G., Gonçalves A.P. Personality differences and COVID-19: Are extroversion [sic] and conscientiousness personality traits associated with engagement with containment measures? Trends in Psychiatry and Psychotherapy. Advance online publication. 2020 doi: 10.1590/2237-6089-2020-0029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coelho G.L., Vilar R., Hanel P.H., Monteiro R.P., Ribeiro M.G., Gouveia V.V. Optimism scale: Evidence of psychometric validity in two countries and correlations with personality. Personality and Individual Differences. 2018;134:245–251. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2018.06.030. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. 2nd ed. Erlbaum; Hillsdale, NJ: 1988. Statistical power analyses for the behavioral sciences. [Google Scholar]

- Connor K.M., Davidson J.R.T. Development of a new resilience scale: The Connor-Davidson resilience scale (CD-RISC) Depression and Anxiety. 2003;18:76–82. doi: 10.1002/da.10113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connor K.M., Davidson J.R.T. Connor-Davidson resilience scale (CDRISC) manual. 2020. www.cdrisc.com Retrieved June 5, 2020, from.

- Costa P.T., McCrae R.R. Psychological Assessment Resources; Odessa, FL: 1992. Revised NEO personality inventory (NEO-PI-R) and NEO five-factor inventory (NEO-FFI) manual. [Google Scholar]

- Digman J.M. Personality structure: Emergence of the five-factor model. Annual Review of Psychology. 1990;41:417–440. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ps.41.020190.002221. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ehrhart M.G., Ehrhart K.H., Roesch S.C., Chung-Herrera B.G., Nadler K., Bradshaw K. Testing the latent factor structure and construct validity of the ten-item personality inventory. Personality and Individual Differences. 2009;47:900–905. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2009.07.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Garbe L., Rau R., Toppe T. Influence of perceived threat of Covid-19 and HEXACO personality traits on toilet paper stockpiling. PLoS One. 2020;15 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0234232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gosling S.D., Rentfrow P.J., Swann W.B. A very brief measure of the big-five personality domains. Journal of Research in Personality. 2003;37:504–528. doi: 10.1016/S0092-6566(03)00046-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kroenke K., Spitzer R.L., Williams J.B., Lowe B. An ultra-brief screening scale for anxiety and depression: The PHQ-4. Psychosomatics. 2009;50:613–621. doi: 10.1176/appi.psy.50.6.613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus R.S. Oxford University Press; New York: 1991. Emotion and adaptation. [Google Scholar]

- McDonald R.P. Erlbaum; Mahwah, NJ: 1999. Test theory: A unified approach. [Google Scholar]

- McNeish D. Thanks coefficient alpha: We’ll take it from here. Psychological Methods. 2018;23:412–433. doi: 10.1037/met0000144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nunes A., Limpo T., Lima C.F., Castro S.L. Short scales for the assessment of personality traits: Development and validation of the Portuguese ten-item personality inventory (TIPI) Frontiers in Psychology. 2018;9:461. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Somma A., Gialdi G., Krueger R.F., Markon K.E., Frau C., Lovallo S.…Fossati A. Dysfunctional personality features, non-scientifically supported causal beliefs, and emotional problems during the first month of the COVID-19 pandemic in Italy. Personality and Individual Differences. 2020;165:110139. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2020.110139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabachnick B.G., Fidell L.S. 7th ed. Pearson; New York: 2019. Using multivariate statistics. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor S. Cambridge Scholars Publishing; Newcastle upon Tyne: 2019. The psychology of pandemics: Preparing for the next global outbreak of infectious disease. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor S. COVID stress syndrome: Clinical and nosological considerations. Current Psychiatry Reports. 2021 doi: 10.1007/s11920-021-01226-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor S., Asmundson G.J.G. Guilford; New York: 2004. Treating health anxiety. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor S., Landry C., Paluszek M., Fergus T.A., McKay D., Asmundson G.J.G. Development and initial validation of the COVID stress scales. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2020;72:102232. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2020.102232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor S., Landry C., Paluszek M., Fergus T.A., McKay D., Asmundson G.J.G. Concept, structure, and correlates. Depression and Anxiety; Syndrome: 2020. COVID stress. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zajenkowski M., Jonason P.K., Leniarska M., Kozakiewicz Z. Who complies with the restrictions to reduce the spread of COVID-19? Personality and Individual Differences. 2020;166:110199. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2020.110199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]