Abstract

For most mobile technology users, social media platforms are their main source of information about the COVID-19 pandemic. Using the stimulus-organism-response model, this study proposes that information quality and media richness are related to social media fatigue, which induces negative coping with the COVID-19 pandemic. The moderating roles of health consciousness and COVID-19-induced strain are also examined. The data were collected from 108 users of WeChat using a daily experience sampling method and analyzed using multilevel structural equation modeling with Mplus. The results show that information quality significantly decreases social media fatigue, whereas media richness significantly increases social media fatigue, which is an outcome of negative coping. Health consciousness buffers the indirect effect of information quality on negative coping through social media fatigue, whereas COVID-19-induced strain strengthens the indirect effect of media richness on negative coping through social media fatigue. These findings enrich the literature on social media fatigue and negative coping by revealing the informational and technical causes of these issues at the episode level in the period of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Keywords: Information quality, Media richness, Social media fatigue, Negative coping, Health consciousness, COVID-19-induced strain

1. Introduction

Advances in mobile internet technology have made mobile social platforms one of the most important sources of information for mobile users (Miah, Hasan, Hasan, & Gammack, 2017). During the on-going COVID-19 pandemic, social media platforms are an effective channel for users to acquire instant health support and COVID-19 related information (Abeler, Bäcker, Buermeyer, & Zillessen, 2020). As of 24:00 on March 26 2020, there were 3460 active cases (including 1034 severe cases), 3292 dead cases, and a total of 81,340 confirmed cases in China. Currently, only a few studies have explored the influence of mobile social platform on users' coping strategies during the COVID-19 pandemic. How information on mobile social platforms shapes users' attitudes and behavior depends on the information and technical characteristics of the platform (Xiao & Mou, 2019).

Regarding the information characteristics, information quality (IQ) plays a central role in shaping recipients' responses (Grohol, Slimowicz, & Granda, 2014). IQ refers to the accuracy, completeness, clarity, usefulness, and reliability of an information system's data outputs (C.-C. Chen & Chang, 2018). Regarding the technical characteristics, media richness (MR) reveals a social medium's ability to convey certain types of information and is determined by its capacity to give immediate feedback, the multiple cues and senses involved, language variety, and personalization (Brunelle, 2009). Recently, a negative effect of MR has been recognized to associate with information overload and result in unpleasant emotional experiences (Badger, Kaminsky, & Behrend, 2014).

IQ and MR are two distinct concepts that reveal information and technical characteristics, respectively (C.-C. Chen & Chang, 2018). Whether individuals decide to positively or negatively solve problems depends on the information they have (Dennis & Kinney, 1998; Wu, 2018). For instance, IQ enhances individuals' intention to engage in psychological-based treatment to decrease depression (Wu, 2018), and MR facilitates doctor–patient communication to enable patients to positively cope with problems (Dennis & Kinney, 1998). However, little research focuses on how the characteristics of mobile social platforms may shape users' coping strategies in response to negative events, such as the COVID-19 pandemic. To address these gaps, this study uses a stimulus-organism-response (SOR) model to explore the proximal influences of IQ and MR on the coping strategies of mobile social media users.

1.1. Information quality, media richness, and social media fatigue

The SOR model posits that various features of the external environment work as stimuli (S) that affects the emotions, perceptions, strain, and thinking of individuals, as organisms (O) (Zhu, Li, Wang, He, & Tian, 2020). Such internal states consequently shape their responses (R) through their behavioral choices (Cao, Masood, Luqman, & Ali, 2018). Using the SOR model, we propose that IQ and MR first affect the internal mechanism of social platforms, which influences users' choice of coping strategies. Regarding the internal mechanism, we hypothesize that social media fatigue (SMF) mediates the relationship between the characteristics of a mobile social platform (i.e., IQ and MR) and its users' coping strategies. SMF is a subjective, multidimensional user experience comprising of feelings such as tiredness, anger, disappointment, loss of interest, or reduced need/motivation for social media use (Lo, 2019; Xiao & Mou, 2019).

IQ measures whether the information is accurate and presented in a clear format; both contribute to the usability of the information (Laumer, Maier, & Weitzel, 2017). The existing studies have found that IQ decreases information overload and anxiety, and both are vital in shaping SMF (Kugbey, Meyer-Weitz, & Oppong Asante, 2019). Therefore, it can be inferred that IQ is negatively related to SMF.

MR measures the extent to which the media portray more than just the words/text of the message (Trevino, Lengel, & Daft, 1987). Although MR facilitates communication efficiency to a certain degree, it also represents mass information that needs to be processed by recipients in a short time (Tseng, Cheng, Li, & Teng, 2017). Information about the COVID-19 pandemic, such as the work functioning, infectious mechanism, and the prevention strategies, is novel to most recipients (Chan, Nickson, Rudolph, Lee, & Joynt, 2020). Therefore, the negative effect of MR emerges, so the richer the information from social media is, the higher the information load experienced by the recipients will be (Schneider, 1987), thereby increasing SMF due to the increase in information overload (Whelan, Najmul Islam, & Brooks, 2020). Therefore, we propose that MR is positively related to SMF.

1.2. Social media fatigue and negative coping

When experiencing SMF, individuals usually have negative emotions, such as anxiety and depression (Dhir, Yossatorn, Kaur, & Chen, 2018). Thus, they are more likely to adopt negative coping strategies to escape from unpleasant experiences (Dempsey, 2002). Coping strategies are cognitive or behavioral efforts to manage stress (Gaudioso, Turel, & Galimberti, 2017). Negative coping (NC) or avoidance coping comprises of asocial avoidant behaviors that are not focused on the stressor, including distraction, and withdrawal thinking (Gaudioso et al., 2017). During the COVID-19 pandemic, NC strategies usually require keeping one's feelings to one's self, staying away from relevant information, and avoiding connecting with other people (C. Zhang et al., 2020). NC does not alter the damaging or threatening condition but only make the individual feel better temporarily (Kritsotakis et al., 2018). NC is usually associated with worse mental health and increased deviant behavior, such as drug abuse and aggression (Hendy, Can, & Black, 2019). Using NC strategies impedes adapting to the COVID-19 pandemic (Cherry et al., 2017). The existing studies indicate that NC is a risky factor for depression, and anxiety (C. Zhang et al., 2020). Therefore, this study assumes that NC is an outcome of SMF and explores the indirect temporal effects of IQ and MR on NC through SMF during the COVID-19 pandemic. Insights into these indirect effects will enable individuals to better manage SMF and avoid NC. Therefore, we propose the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1

SMF mediates the negative indirect relationship between IQ and NC.

Hypothesis 2

SMF mediates the positive indirect relationship between MR and NC.

1.3. Moderating effects of COVID-19-induced strain and health consciousness

Prior SOR studies have indicated the importance of personal characteristics in shaping the effects of stimuli on an organism (Cao et al., 2018). Therefore, this study adopts chronic COVID-19 induced strain (CIS) and health consciousness (HC) as personal characteristics to explain why and how individuals evaluate IQ and MR and how they increase/decrease the likelihood that IQ and MR will be perceived as stressors.

CIS is an unpleasant subjective experience of the COVID-19 pandemic (Schmitt, Den Hartog, & Belschak, 2016). The pandemic is causing individuals to experience psychological strain (Tan et al., 2020). When experiencing CIS, individuals are motivated to direct their cognitive resources to ensure basic functioning (Schmitt et al., 2016). Therefore, fewer resources are left to deal with mass information, leading to a higher likelihood of experiencing SMF even when exposed to high-quality information. Therefore, we propose that CIS buffers the indirect relationship between IQ and NC through SMF.

HC reflects an individuals' readiness to do something about their health; it assesses the degree of the availability of different options to pursue healthy activities (M.-F. Chen, 2009). Individuals with high HC tend to find health information online (Ahadzadeh, Pahlevan Sharif, & Sim Ong, 2018). However, when the information is novel and complex, these individuals are more likely to experience information overload, enhancing their likelihood of experiencing SMF (Schneider, 1987). Therefore, we argue that HC strengthens the indirect relationship between MR and NC through the mediating effect of SMF and propose the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 3

CIS buffers the negative indirect effect of IQ on NC through SMF.

Hypothesis 4

HC strengthens amplifies the positive indirect effect of MR on NC through SMF.

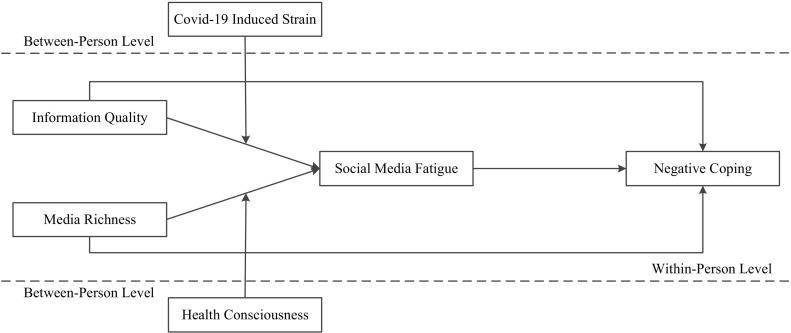

To address the research question of how and when IQ and MR impact NC at the episode level, we adopted the experience sampling method (ESM) to collect daily data based on the SOR model to test our conceptual model (see Fig. 1 ).

Fig. 1.

Conceptual model.

2. Method

2.1. Sample and procedures

Since this study was performed during the COVID-19 pandemic, the convenience sampling method was employed to recruit participants based on the method proposed by Du, Derks, and Bakker (2018). The following are the selection criteria: (1) at least one year experience using WeChat, (2) living in mainland China, and (3) having at least one mobile device that is connected to the Internet. WeChat was chosen as a representative of mobile social platforms because it is one of the most popular social media platforms in China, with more than one billion active users across the world as at 2017 (Shao & Pan, 2019). WeChat is one of the most influential sources of information on COVID-19. Several services for COVID-19, such as timely news and real-time dynamic map of the pandemic situation, free psychological consultation to decrease anxiety, and free medical consultation to avoid COVID-19 infection, have been offered on WeChat. Moreover, users can communicate with their families and friends about how to prevent COVID-19 infection and remain healthy.

Questionnaires were sent through the researchers' WeChat account. The purpose of the research and a detailed five-day research process were explained to the participants. A research group was formed in WeChat and initially, 150 participants were invited to join the research group. The data were collected in two stages. The first stage was conducted on February 23, 2020. The participants were asked to answer a questionnaire, which required demographic information (gender, age, and education) and information on the moderating variables (HC and CIS.) The second stage was from February 24 to 28. The participants were asked to answer a questionnaire about IQ and MR from 11:00 a.m. to 1:00 p.m. and about SMF and NC from 5:00 p.m. to 7:00 p.m.. Ultimately, 540 matched cases nested into 108 participants were used for the analysis, yielding an effective response rate of 72%. The detailed demographic information is presented in Table 1 . Following the research of Huang and Ryan (2011), the power analysis in two-level (PINT) program was used for the research design (Snijders & Bosker, 1993). The result shows that 108 participants had to engage in 5 daily surveys in order to achieve the power of 0.80.

Table 1.

Demographic information.

| Demographic variables | Groups | N | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 59 | 54.60% |

| Female | 49 | 45.40% | |

| Education | Primary School | 1 | 0.90% |

| Senior School | 2 | 1.90% | |

| High School | 29 | 26.90% | |

| College | 26 | 24.10% | |

| Bachelor and above | 50 | 46.30% | |

| Age | Under 26 | 2 | 1.90% |

| 26–35 | 49 | 45.40% | |

| 36–45 | 35 | 32.40% | |

| Above 46 | 22 | 20.40% |

2.2. Measurements

Due to the nature of the ESM, the items were adapted to fit the daily usage of WeChat. The scales were originally developed in English, and a back-translation was used to translate the scales into Chinese, which ensured the accuracy of the translation (Brislin, 1970). Furthermore, short scales were adopted to ensure a high response rate (Donald, Atkins, Parker, Christie, & Ryan, 2016). The scales were presented on a seven-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). The scales are presented in the Appendix.

2.2.1. Daily measurement

2.2.1.1. IQ

IQ was measured using four items developed by Bhattacherjee and Sanford (2006). A representative item is “Today, the information provided about the COVID-19 was informative on WeChat.” The Cronbach's α is 0.79.

2.2.1.2. MR

Four items developed by Brunelle (2009) were used to measure the MR of WeChat. A representative item is “Today, WeChat gave and received timely feedback about COVID-19.” The Cronbach's α is 0.83.

2.2.1.3. SMF

Four items with the highest loadings were adapted from the scale developed by S. Zhang, Zhao, Lu, and Yang (2016). A representative item is “Today, I felt drained from using WeChat sometimes.” The Cronbach's α is 0.93.

2.2.1.4. NC

Three items with the highest loadings were adapted from the scale developed by Long (1990). A representative item is “Today, I avoided being with people in general.” The Cronbach's α is 0.95.

2.2.2. Baseline measurement

2.2.2.1. HC

HC was measured using three items developed by Mai and Hoffmann (2012). A representative item is “I reflect about my health a lot.” The internal consistency of this scale is 0.83.

2.2.2.2. CIS

Three items developed by House and Rizzo (1972) were used to represent CIS. A representative item is “Due to COVID-19, I live and work under a great deal of tension.” The Cronbach's α is 0.76.

2.2.2.3. Control variables

To control the influences of demographic information on NC, we controlled for age, gender, and education in the multilevel structural equation model (Y. Chen, Peng, Xu, & O'Brien, 2018; Mark & Smith, 2018).

3. Results

3.1. Multilevel confirmatory factor analysis (MCFA)

MCFA was performed to examine the construct validity. The results are shown in Table 2 . The six-factor conceptual model (χ 2 = 227.80, df = 91, RMSEA = 0.05, CFI = 0.96, TLI = 0.95, and S RMR = 0.06) has a better fit than any other model, indicating that common method variance (CMV) is not a problem in this study (Podsakoff, MacKenzie, Lee, & Podsakoff, 2003).

Table 2.

Results of confirmatory factor analysis.

| Model | Variables | X2 | df | △X2 | RMSEA | CFI | TLI | SRMRwithin | SRMRbetween |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Six-Factor Model | IQ, MR, SMF, NC, CIS, HC | 227.80 | 91 | 0.05 | 0.96 | 0.95 | 0.06 | 0.06 | |

| Five-Factor Model 1 | IQ + MR, SMF, NC, CIS, HC | 534.32 | 94 | 306.52⁎⁎ | 0.09 | 0.87 | 0.84 | 0.13 | 0.06 |

| Five-Factor Model 2 | IQ + SMF, MR, NC, CIS, HC | 923.10 | 94 | 695.30⁎⁎ | 0.13 | 0.76 | 0.70 | 0.16 | 0.06 |

| Five-Factor Model 3 | IQ + NC, MR, SMF, CIS, HC | 889.36 | 94 | 661.56⁎⁎ | 0.13 | 0.77 | 0.71 | 0.15 | 0.06 |

| Five-Factor Model 4 | IQ, MR + SMF, NC, CIS, HC | 620.14 | 94 | 392.34⁎⁎ | 0.10 | 0.85 | 0.81 | 0.14 | 0.06 |

| Five-Factor Model 5 | IQ, MR + NC, SMF, CIS, HC | 662.84 | 94 | 435.04⁎⁎ | 0.11 | 0.84 | 0.79 | 0.15 | 0.06 |

| Five-Factor Model 6 | IQ, MR, SMF + NC, CIS, HC | 1117.02 | 94 | 889.22⁎⁎ | 0.14 | 0.71 | 0.63 | 0.11 | 0.06 |

| Five-Factor Model 7 | IQ, MR, SMF, NC, CIS + HC | 283.81 | 92 | 56.01⁎⁎ | 0.06 | 0.95 | 0.93 | 0.06 | 0.13 |

| Two-Factor Model | IQ + MR + SMF + NC, CIS + HC | 2013.02 | 98 | 1785.22⁎⁎ | 0.19 | 0.45 | 0.33 | 0.21 | 0.13 |

Note:IQ = Information Quality; MR = Media Richness; SMF = Social Media Fatigue; NC = Negative Coping; CIS = COVID-19 Induced Strain; HC = Health Consciousness; **p < 0.01; *p < 0. 5.

3.2. Descriptive statistics and correlation analysis

Table 3 shows the means, standard deviations, reliabilities, and correlations of the variables at both the with- and between-person levels. The proportion of the within-person variance ranges from 72% to 90%, justifying the use of multilevel analysis.

Table 3.

Means, standard deviations, and correlation analysis.

| Variables | Mean | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Within-person (N = 540) | |||||||

| 1.Negative coping | 3.77 | 0.73 | (0.95) | ||||

| 2.Information quality | 3.1 | 1.35 | 0.13⁎⁎ | (0.79) | |||

| 3.Media richness | 4.6 | 0.98 | 0.17⁎⁎ | 0.31⁎⁎ | (0.83) | ||

| 4.Social media fatigue | 4.1 | 0.67 | 0.54⁎⁎ | −0.05 | 0.29⁎⁎ | (0.93) | |

| Between-person (N = 108) | Mean | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 1.Gender | 1.45 | 0.5 | |||||

| 2.Age | 2.71 | 0.81 | −0.48⁎⁎ | ||||

| 3.Education | 4.13 | 0.94 | 0.67⁎⁎ | −0.23⁎⁎ | |||

| 4.Covid-19 induced strain | 3.92 | 0.35 | −0.06 | 0.06 | 0.04 | (0.76) | |

| 5.Health consciousness | 4.39 | 0.58 | −0.04 | 0.11 | 0.01 | 0.44⁎⁎ | (0.83) |

Values in the parenthesis are Cronbach's alpha coefficients.

p < 0.01.

3.3. Multilevel structural equation model analysis

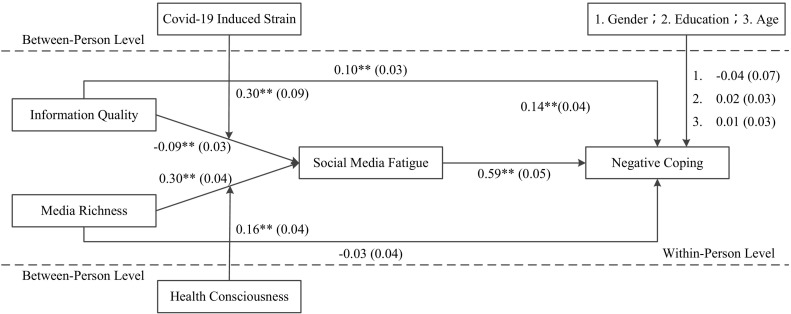

The results are shown in Fig. 2 . The results indicate that the daily IQ is negatively related to SMF (γ = −0.09, p < 0.01), whereas daily MR is positively related to SMF (γ = 0.30, p < 0.01). Furthermore, SMF is positively correlated with NC (γ = 0.59, p < 0.01).

Fig. 2.

Results of multilevel structural equation model.

A Monte Carlo bootstrapping test was used to explore the mediating role of SMF. The results presented in Table 4 show that the indirect effect of IQ on NC through SMF is significant (Effect = −0.05, 95%CI = [−0.09, −0.02]). The mediating effect of SMF on the relationship between MR and NC is also significant (Effect = 0.18, 95%CI = [0.12, 0.23]).

Table 4.

Results of Monte Carlo bootstrapping test.

| Effect | Estimator | SE | 95% confidence intervaL |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower level | Upper level | |||

| Moderating effect of Covid-19 induced strain | ||||

| Low (M-SD) | −0.20 | 0.04 | −0.28 | −0.11 |

| High (M + SD) | 0.01 | 0.04 | −0.07 | 0.10 |

| Difference | 0.21 | 0.06 | 0.09 | 0.33 |

| Moderating effect of health consciousness | ||||

| Low (M-SD) | 0.21 | 0.05 | 0.12 | 0.30 |

| High (M + SD) | 0.39 | 0.05 | 0.30 | 0.48 |

| Difference | 0.18 | 0.05 | 0.09 | 0.28 |

| Mediating model of social media fatigue | ||||

| Information quality path | ||||

| Direct effect | 0.10 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.16 |

| Indirect effect | −0.05 | 0.02 | −0.09 | −0.02 |

| Media richness path | ||||

| Direct effect | −0.03 | 0.04 | −0.11 | 0.05 |

| Indirect effect | 0.18 | 0.03 | 0.12 | 0.23 |

| Moderated mediation model | ||||

| Information quality path | ||||

| Low (M-SD) | −0.11 | 0.03 | −0.17 | −0.06 |

| High (M + SD) | 0.01 | 0.03 | −0.04 | 0.06 |

| Difference | 0.12 | 0.04 | 0.05 | 0.20 |

| Media richness path | ||||

| Low (M-SD) | 0.12 | 0.03 | 0.07 | 0.18 |

| High (M + SD) | 0.23 | 0.03 | 0.17 | 0.30 |

| Difference | 0.11 | 0.03 | 0.06 | 0.17 |

Note: Bootstrapping = 20,000.

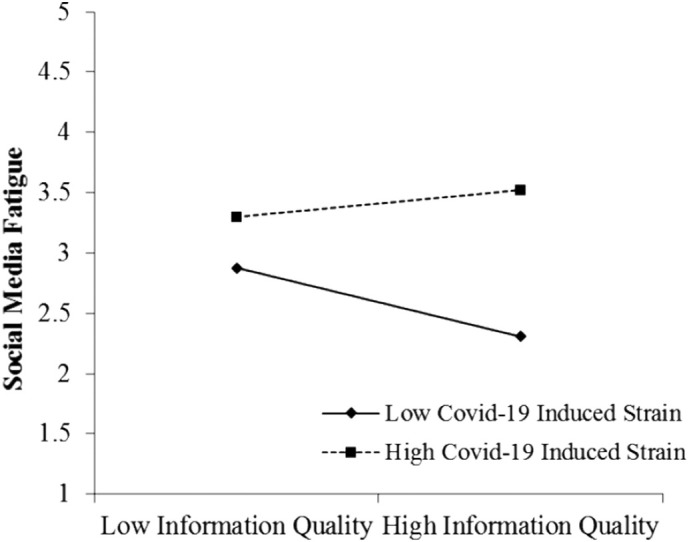

The moderating role of CIS on the relationship between IQ and SMF is significant (γ = 0.30, p < 0.01), especially the impact of IQ on SMF is only significant under conditions of low CIS (Effect = −0.20, 95%CI = [−0.28, −0.11]) but not under conditions of high CIS (Effect = −0.01, 95%CI = [−0.07, 0.10]). The significant difference between the two slopes (Effect = 0.21, 95%CI = [0.09, 0.33]) indicates the moderating role of CIS (see Fig. 3 ). We also explored the moderating role of CIS in the indirect relationship between IQ and NC through SMF. The indirect relationship is significant under conditions of low CIS (Effect = −0.11, 95%CI = [−0.17, −0.06]) buy not under conditions of high CIS (Effect = 0.01, 95%CI = [−0.04, 0.06]). The significant difference between these two indirect effects justifies the use of the moderated mediation model (Effect = 0.12, 95%CI = [0.05, 0.20]).

Fig. 3.

The moderating effect of COVID-19 induced strain in the relationship between information quality and social media fatigue.

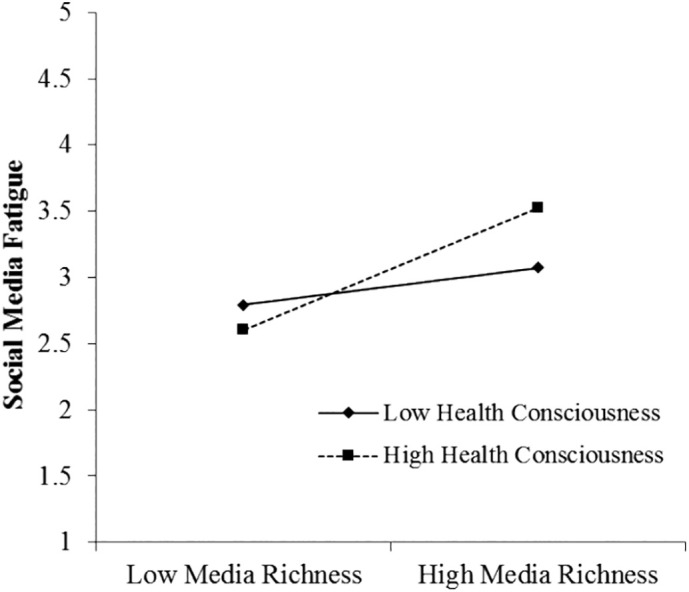

The moderating role of HC on the relationship between MR and SMF is significant (γ = 0.16, p < 0.01), especially the impact of MR on SMF is stronger under conditions of high HC (Effect = 0.39, 95%CI = [0.30, 0.48]) than under conditions of low HC (Effect = 0.21, 95%CI = [0.12, 0.30]). The significant difference between the two slopes (Effect = 0.18, 95%CI = [0.09, 0.28]) indicates the moderating role of HC (see Fig. 4 ). We explored the moderating role of HC in the indirect relationship between MR and NC through SMF. The indirect relationship is stronger under conditions of high HC (Effect = 0.23, 95%CI = [0.17, 0.30]) than under conditions of low HC (Effect = 0.12, 95%CI = [0.07, 0.18]). The significant difference between these two indirect effects also justifies the use of the moderated mediation model (Effect = 0.11, 95%CI = [0.06, 0.17]).

Fig. 4.

The moderating effect of health consciousness in the relationship between media richness and social media fatigue.

4. Discussion

4.1. Theoretical and practical implications

This study has three theoretical implications for future research. First, this study differentiates between the influences of IQ and MR on SMF. Prior studies mainly explored the benefits of IQ and MR on the information recipients' psychological outcomes. For instance, C.-C. Chen and Chang (2018) confirmed that IQ and MR enhanced buyers' satisfaction. This study first establishes the role of IQ in decreasing SMF, which is consistent with the prior studies. It is easy for recipients to understand and use high-quality information, thereby inhibiting SMF (Bright, Kleiser, & Grau, 2015). Regarding MR, this study reveals its negative effect. A novel, negative, and copious information was provided by rich media during the COVID-19 pandemic. This information needs more cognitive resources to process, resulting in information overload, which is the critical antecedent to SMF (Cao et al., 2018; Kugbey et al., 2019). This study contributes to the IQ and MR literature by exploring their contradictory relationship with SMF.

Second, this study uncovers the mediating role of SMF in the effects of IQ and MR on NC. Although prior studies have explored how online information and social media impact SMF, studies that have explored how SMF influences personal choices of coping strategies are rare (Bright et al., 2015). This study extends the literature about the relationship between SMF and negative coping by using the SOR model to analyze these variables during the COVID-19 pandemic. SMF is a subjective state in which individuals experience cognitive and emotional strain during or after social media use (Xiao & Mou, 2019). Maladaptive coping strategies may be used to avoid such uncomfortable experiences (Dempsey, 2002). This study contributes to the SMF literature by revealing its mediating role in the relationship between online stimuli and coping responses during a public health crisis.

Third, this study contributes to the SOR model by exploring the moderating role of CIS and HC. This research introduces CIS and HC as two moderators in the SOR process regarding IQ and MR. We find that CIS plays a buffering role in the negative relationship between IQ and SMF due to its occupation of attention resources to ensure basic functioning rather than to process novel information about the COVID-19 pandemic, which is consistent with prior studies (Schmitt et al., 2016). However, this study reveals the negative effect of HC, which is regarded as an antecedent to healthy behavior (M.-F. Chen, 2009). HC drives people to search for information to ensure that they are healthy during the COVID-19 pandemic. Although the novel information needs more cognitive resources to process, high HC individuals are more likely to engage in SMF when confronted with rich media because their cognitive resources are already occupied by mass health information (Ahadzadeh et al., 2018; Schneider, 1987). This study identifies two important personal characteristics (i.e., HC and CIS) in the SOR process in the field of cyberpsychology, enlarging the scope of the SOR model.

Our research also has several practical implications. The information provided on WeChat is mostly posted by public official accounts. Public officials should pay attention to the quality of the information they post on WeChat. HC is important in driving individuals to maintain healthy behaviors. However, HC is not always beneficial. Individuals should not pay too much attention to novel and unfamiliar health information about the COVID-19 pandemic, which could induce unnecessary cognitive overload. Moreover, the negative side of MR should be addressed. Thus, when mobile social platforms post information about the COVID-19 pandemic, the information should be presented simply and concisely. Psychological strain strengthens the negative influence of MR on SMF. Therefore, necessary interventions, such as e-mental health mindfulness-based and skill-based “CoPE It” intervention, should be adopted to reduce psychological strain (Bäuerle et al., 2020). It is an intervention performed through mobile phones to reduce psychological strain, which satisfies the quarantine requirements during the COVID-19 pandemic.

4.2. Limitations and future research

This study has several limitations. First, it was unable to establish a causal relationship. Future research may use a cross-lagged panel design or a simulation experiment design to explore the impacts of IQ and MR on SMF and NC. Second, more information and technical characteristics should be considered in the future. Prior studies have confirmed the longitudinal influences of information overload and privacy invasion on SMF (Xiao & Mou, 2019). Future research may explore their temporal influences on SMF to extend this line of research.

4.3. Conclusions

This study examines significant issues related to IQ, MR, SMF, NC, HC, and CIS. It identified the different influences of IQ and MR on SMF, which are IQ decreases SMF and MR increases it. This study also explores the temporal mediating role of SMF in the effects of IQ and MR on NC. Moreover, this study explores the moderating role of HC and CIS in the indirect effects of IQ and MR on NC through SMF. CIS buffers the indirect relationship between IQ and NC through SMF, whereas HC strengthens the indirect relationship between MR and NC through SMF. Thus, this study advances our understanding of the relationship between the characteristics of mobile social platforms and negative coping during the COVID-19 pandemic.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Zhenduo Zhang: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – Original Draft preparation; Li Zhang: Supervision; Huan Xiao: Data Curation; Junwei Zheng: Writing- Reviewing and Editing.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors have declared that no conflict of interest exists.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grants No. 71772052, and 71701083).

Ethics approval statement

I would like to declare on behalf of my co-authors that the work described was original research that has not been published previously, and not under consideration for publication elsewhere, in whole or in part. All the authors listed have approved the manuscript that is enclosed.

Appendix A. Measurements

Information Quality (Bhattacherjee & Sanford, 2006):

IQ1: Today, the information provided about the COVID-19 was informative on WeChat.

IQ2: Today, the information provided about the COVID-19 was helpful on WeChat.

IQ3: Today, the information provided about the COVID-19 was valuable on WeChat.

IQ4: Today, the information provided about the COVID-19 was persuasive on WeChat.

Media Richness (Brunelle, 2009):

MR1: Today, WeChat gave and received timely feedback about COVID-19.

MR2: Today, WeChat tailored the messages exchanged about COVID-19.

MR3: Today, WeChat communicated a variety of different cues (such as emotional tone or attitude) about COVID-19.

MR4: Today, WeChat used rich and varied language about COVID-19.

Social Media Fatigue (S. Zhang et al., 2016):

SMF1: Today, I felt tired when using WeChat.

SMF2: Today, I felt bored when using WeChat.

SMF3: Today, I felt drained from using WeChat.

SMF4: Today, I felt worn out from using WeChat.

Negative Coping (Long, 1990):

NC1: Today, I Wished that I could change what happened or how I felt.

NC2: Today, I daydreamed or imagined a better time or place than the one I was in.

NC3: Today, I had fantasies or wishes about how things might.

Health Consciousness (Mai & Hoffmann, 2012)

HC1: I reflect about my health a lot.

HC2: I'm generally attentive to my inner feelings about my health.

HC3: I am constantly examining my health.

Covid-19 Induced Strain (House & Rizzo, 1972)

CIS1: Due to Covid-19, I live and work under a great deal of tension.

CIS2: I often feel fidgety or nervous as a result of Covid-19.

CIS3: Problems associated with life and work caused by Covid-19 have kept me awake at night.

References

- Bhattacherjee, Sanford Influence processes for information technology acceptance: An elaboration likelihood model. MIS Quarterly. 2006;30(4):805–825. doi: 10.2307/25148755. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Abeler J., Bäcker M., Buermeyer U., Zillessen H. COVID-19 contact tracing and data protection can go together. JMIR mHealth and uHealth. 2020;8(4) doi: 10.2196/19359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahadzadeh A.S., Pahlevan Sharif S., Sim Ong F. Online health information seeking among women: The moderating role of health consciousness. Online Information Review. 2018;42(1):58–72. doi: 10.1108/OIR-02-2016-0066. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Badger J.M., Kaminsky S.E., Behrend T.S. Media richness and information acquisition in internet recruitment. Journal of Managerial Psychology. 2014;29(7):866–883. doi: 10.1108/JMP-05-2012-0155. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bäuerle A., Graf J., Jansen C., Musche V., Schweda A., Hetkamp M.…Skoda E.-M. E-mental health mindfulness-based and skills-based “CoPE It” intervention to reduce psychological distress in times of COVID-19: Study protocol for a bicentre longitudinal study. BMJ Open. 2020;10(8) doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-039646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bright L.F., Kleiser S.B., Grau S.L. Too much Facebook? An exploratory examination of social media fatigue. Computers in Human Behavior. 2015;44:148–155. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2014.11.048. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brislin R.W. Back-translation for cross-cultural research. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology. 1970;1(3):185–216. doi: 10.1177/135910457000100301. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brunelle E. Introducing media richness into an integrated model of consumers’ intentions to use online stores in their purchase process. Journal of Internet Commerce. 2009;8(3–4):222–245. doi: 10.1080/15332860903467649. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cao X., Masood A., Luqman A., Ali A. Excessive use of mobile social networking sites and poor academic performance: Antecedents and consequences from stressor-strain-outcome perspective. Computers in Human Behavior. 2018;85:163–174. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2018.03.023. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chan A.K.M., Nickson C.P., Rudolph J.W., Lee A., Joynt G.M. Social media for rapid knowledge dissemination: Early experience from the COVID-19 pandemic. Anaesthesia. 2020;75(12):1579–1582. doi: 10.1111/anae.15057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen M.-F. Attitude toward organic foods among Taiwanese as related to health consciousness, environmental attitudes, and the mediating effects of a healthy lifestyle. British Food Journal. 2009;111(2):165–178. doi: 10.1108/00070700910931986. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C.-C., Chang Y.-C. What drives purchase intention on Airbnb? Perspectives of consumer reviews, information quality, and media richness. Telematics and Informatics. 2018;35(5):1512–1523. doi: 10.1016/j.tele.2018.03.019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y., Peng Y., Xu H., O’Brien W.H. Age differences in stress and coping: Problem-focused strategies mediate the relationship between age and positive affect. The International Journal of Aging and Human Development. 2018;86(4):347–363. doi: 10.1177/0091415017720890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cherry K.E., Lyon B.A., Sampson L., Galea S., Nezat P.F., Marks L.D. Prior hurricane and other lifetime trauma predict coping style in older commercial fishers after the BP deepwater horizon oil spill. Journal of Applied Biobehavioral Research. 2017;22(2) doi: 10.1111/jabr.12058. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dempsey M. Negative coping as mediator in the relation between violence and outcomes: Inner-city African American youth. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2002;72(1):102–109. doi: 10.1037/0002-9432.72.1.102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dennis A.R., Kinney S.T. Testing media richness theory in the new media: The effects of cues, feedback, and task equivocality. Information Systems Research. 1998;9(3):256–274. doi: 10.1287/isre.9.3.256. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dhir A., Yossatorn Y., Kaur P., Chen S. Online social media fatigue and psychological wellbeing—A study of compulsive use, fear of missing out, fatigue, anxiety and depression. International Journal of Information Management. 2018;40:141–152. doi: 10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2018.01.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Donald J.N., Atkins P.W.B., Parker P.D., Christie A.M., Ryan R.M. Daily stress and the benefits of mindfulness: Examining the daily and longitudinal relations between present-moment awareness and stress responses. Journal of Research in Personality. 2016;65:30–37. doi: 10.1016/j.jrp.2016.09.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Du D., Derks D., Bakker A.B. Daily spillover from family to work: A test of the work-home resources model. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology. 2018;23(2):237–247. doi: 10.1037/ocp0000073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaudioso F., Turel O., Galimberti C. The mediating roles of strain facets and coping strategies in translating techno-stressors into adverse job outcomes. Computers in Human Behavior. 2017;69:189–196. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2016.12.041. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Grohol J.M., Slimowicz J., Granda R. The quality of mental health information commonly searched for on the internet. Cyberpsychology, Behavior and Social Networking. 2014;17(4):216–221. doi: 10.1089/cyber.2013.0258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendy H.M., Can S.H., Black P. Workplace deviance as a possible “maladaptive coping” behavior displayed in association with workplace stressors. Deviant Behavior. 2019;40(7):791–798. doi: 10.1080/01639625.2018.1441684. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- House R.J., Rizzo J.R. Role conflict and ambiguity as critical variables in a model of organizational behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Performance. 1972;7(3):467–505. doi: 10.1016/0030-5073(72)90030-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Huang J.L., Ryan A.M. Beyond personality traits: A study of personality states and situational contingencies in customer service jobs. Personnel Psychology. 2011;64(2):451–488. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-6570.2011.01216.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kritsotakis G., Konstantinidis T., Androulaki Z., Rizou E., Asprogeraka E.M., Pitsouni V. The relationship between smoking and convivial, intimate and negative coping alcohol consumption in young adults. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 2018;27(13–14):2710–2718. doi: 10.1111/jocn.13889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kugbey N., Meyer-Weitz A., Oppong Asante K. Access to health information, health literacy and health-related quality of life among women living with breast cancer: Depression and anxiety as mediators. Patient Education and Counseling. 2019;102(7):1357–1363. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2019.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laumer S., Maier C., Weitzel T. Information quality, user satisfaction, and the manifestation of workarounds: A qualitative and quantitative study of enterprise content management system users. European Journal of Information Systems. 2017;26(4):333–360. doi: 10.1057/s41303-016-0029-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lo J. Exploring the buffer effect of receiving social support on lonely and emotionally unstable social networking users. Computers in Human Behavior. 2019;90:103–116. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2018.08.052. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Long B.C. Relation between coping strategies, sex-typed traits, and environmental characteristics: A comparison of male and female managers. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 1990;37(2):185–194. doi: 10.1037/0022-0167.37.2.185. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mai R., Hoffmann S. Taste lovers versus nutrition fact seekers: How health consciousness and self-efficacy determine the way consumers choose food products. Journal of Consumer Behaviour. 2012;11(4):316–328. doi: 10.1002/cb.1390. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mark G., Smith A.P. Coping and its relation to gender, anxiety, depression, fatigue, cognitive difficulties and somatic symptoms. Journal of Education, Society and Behavioural Science. 2018;25(4):1–22. doi: 10.9734/JESBS/2018/41894. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Miah S.J., Hasan N., Hasan R., Gammack J. Healthcare support for underserved communities using a mobile social media platform. Information Systems. 2017;66:1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.is.2017.01.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Podsakoff P.M., MacKenzie S.B., Lee J.-Y., Podsakoff N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology. 2003;88(5):879–903. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitt A., Den Hartog D.N., Belschak F.D. Transformational leadership and proactive work behaviour: A moderated mediation model including work engagement and job strain. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology. 2016;89(3):588–610. doi: 10.1111/joop.12143. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider S.C. Information overload: Causes and consequences. Human Systems Management. 1987;7(2):143–153. doi: 10.3233/HSM-1987-7207. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shao Z., Pan Z. Building Guanxi network in the mobile social platform: A social capital perspective. International Journal of Information Management. 2019;44:109–120. doi: 10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2018.10.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Snijders T.A.B., Bosker R.J. Standard errors and sample sizes for two-level research. Journal of Educational Statistics. 1993;18(3):237–259. doi: 10.3102/10769986018003237. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tan W., Hao F., McIntyre R.S., Jiang L., Jiang X., Zhang L.…Tam W. Is returning to work during the COVID-19 pandemic stressful? A study on immediate mental health status and psychoneuroimmunity prevention measures of Chinese workforce. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity. 2020;87:84–92. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.04.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trevino L.K., Lengel R.H., Daft R.L. Media symbolism, media richness, and media choice in organizations: A symbolic interactionist perspective. Communication Research. 1987;14(5):553–574. doi: 10.1177/009365087014005006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tseng F.-C., Cheng T.C.E., Li K., Teng C.-I. How does media richness contribute to customer loyalty to mobile instant messaging? Internet Research. 2017;27(3):520–537. doi: 10.1108/IntR-06-2016-0181. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Whelan E., Najmul Islam A.K.M., Brooks S. Is boredom proneness related to social media overload and fatigue? A stress–strain–outcome approach. Internet Research. 2020;30(3):869–887. doi: 10.1108/INTR-03-2019-0112. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wu B. Patient continued use of online health care communities: Web mining of patient-doctor communication. Journal of Medical Internet Research. 2018;20(4) doi: 10.2196/jmir.9127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao L., Mou J. Social media fatigue -technological antecedents and the moderating roles of personality traits: The case of WeChat. Computers in Human Behavior. 2019;101:297–310. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2019.08.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang C., Ye M., Fu Y., Yang M., Luo F., Yuan J., Tao Q. The psychological impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on teenagers in China. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2020;67(6):747–755. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2020.08.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang S., Zhao L., Lu Y., Yang J. Do you get tired of socializing? An empirical explanation of discontinuous usage behaviour in social network services. Information & Management. 2016;53(7):904–914. doi: 10.1016/j.im.2016.03.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu L., Li H., Wang F.-K., He W., Tian Z. How online reviews affect purchase intention: A new model based on the stimulus-organism-response (S-O-R) framework. Aslib Journal of Information Management. 2020;72(4):463–488. doi: 10.1108/AJIM-11-2019-0308. [DOI] [Google Scholar]