Abstract

Objectives

The objective of this case report was to describe a rare presentation of corkscrew cerebral angiopathy presenting as subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH).

Methods

We present a young woman who presented with a thunderclap headache, found to have a nonaneurysmal SAH.

Results

Cerebral angiogram revealed corkscrew angiopathy in medium-sized vessels and multiple micro-occlusions with collateralization. No intracranial aneurysm was detected. Extensive workup for vasculitis and genetic causes for vasculopathy was unrevealing. The patient had no neurologic deficits, and her symptoms resolved.

Discussion

This is an extremely rare presentation of subarachnoid hemorrhage due to corkscrew angiopathy.

PRACTICAL IMPLICATIONS

Corkscrew angiopathy is a rare etiology of SAH and should be considered in the differential diagnosis. Conventional angiography can aid in diagnosis, and further workup for vasculitis and genetic etiologies should be pursued.

This report describes a rare presentation of corkscrew cerebral angiopathy presenting as nonaneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH). Corkscrew vasculature is characterized as having a helical course with at least 2 loops of spiraling, giving the appearance of a corkscrew. This is distinct from arterial tortuosity, the latter of which encompasses several characteristics including an S-shaped or C-shaped elongation and kinking.1 There have been few prior reports of corkscrew angiopathy. To our knowledge, our case is the first to present with SAH.

Case

A 45-year-old African American woman with a medical history of IgA nephropathy (normal renal function), hypertension, gastric bypass, and recent COVID infection presented to the hospital with abdominal pain. On day 2 of admission, she was undergoing an evaluation for cholecystitis when she developed a thunderclap headache. The headache was acute in onset and left-sided without photophobia, nausea, or vomiting. She had no visual changes and a normal neurologic examination. Blood pressure at the time was 159/77. At the time of the event, she was on therapeutic enoxaparin and completing a 10-day course of dexamethasone 6 mg daily for recent COVID infection (3 days remaining). She was taking lisinopril as well as metronidazole, ondansetron, and intermittent morphine for cholecystitis.

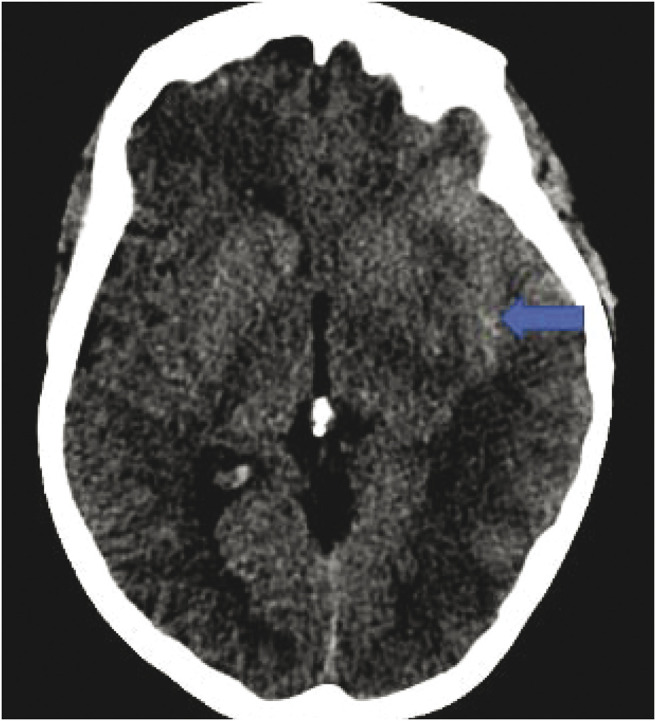

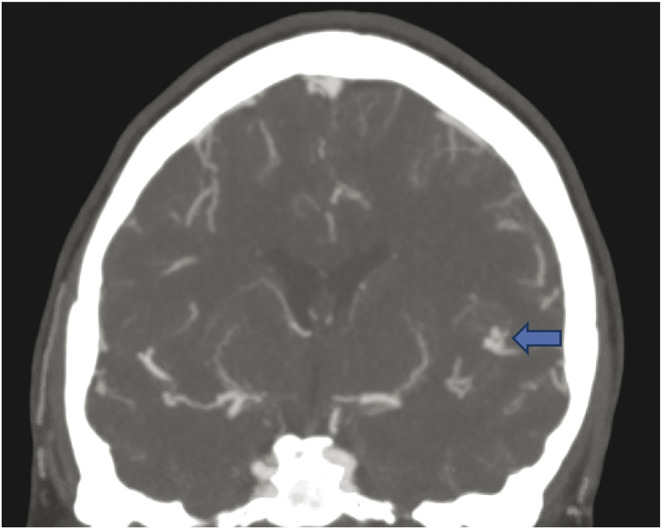

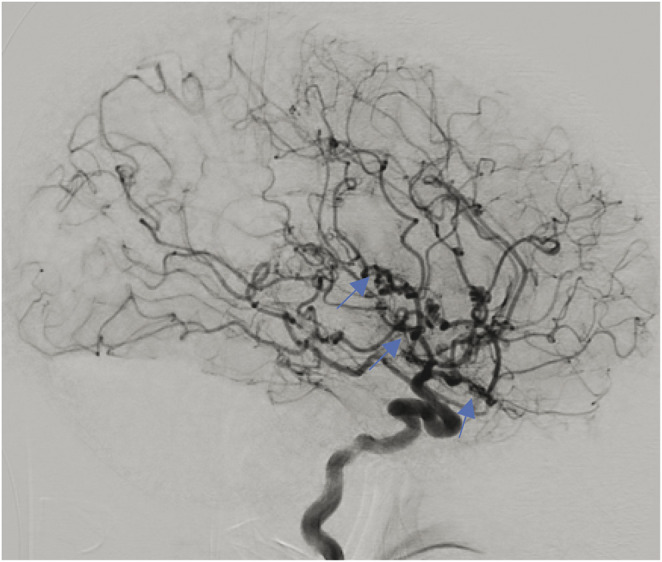

Based on the clinical presentation, initial differential diagnosis included SAH, reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndrome (RCVS), or cerebral venous sinus thrombosis. CT brain revealed SAH in the left sylvian fissure and left suprasellar cistern (Figure 1). CT angiogram showed a possible left M2 aneurysm (Figure 2) with patent venous sinuses. Cerebral angiogram revealed corkscrew tortuosity of her intracranial vasculature, in the medium-sized vessels with relative sparing of the proximal vessels (Figure 3). The aforementioned left M2 aneurysm was in fact a corkscrew turn in her left middle cerebral artery. No aneurysm nor arteriovenous malformation was detected. Anticoagulation and steroids were stopped. She was treated with nimodipine to prevent vasospasm. Transcranial doppler velocities were not consistent with vasospasm. Notably, there was a family history of IgA nephropathy in her 3 siblings, but no known family history of vasculopathy, stroke, or transient ischemic attack. She never had neurologic symptoms in the past. She did not smoke or use illicit drugs.

Figure 1. Noncontrast CT Showing Acute SAH Within the Left Sylvian Fissure.

SAH = subarachnoid hemorrhage.

Figure 2. CT Angiogram Showing Suspected Bilobed Left M2 Aneurysm.

Figure 3. Lateral View of the Left ICA Showing Multifocal Corkscrew Appearance of the Left MCA and ACA Branches.

The left ophthalmic artery is absent. ACA = anterior cerebral artery; ICA = internal cerebral artery; MCA = middle cerebral artery.

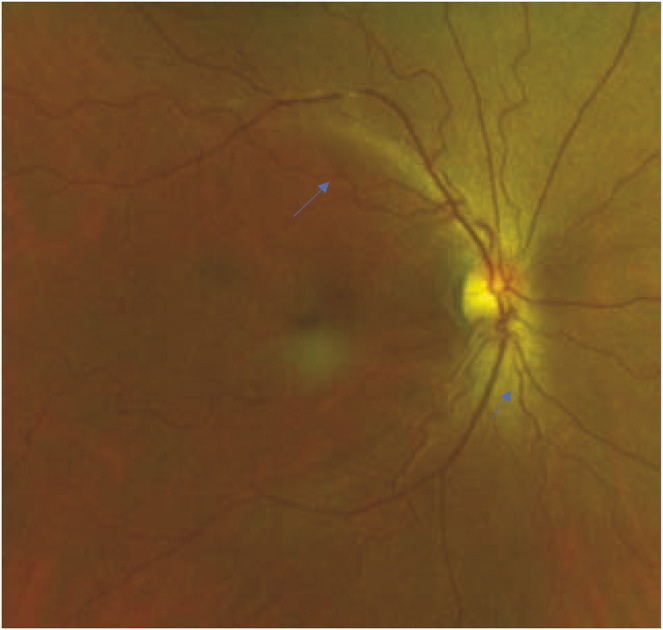

MRI brain did not show ischemic changes. Differential diagnosis at this point included vasculitis, a genetic etiology for vasculopathy, and less likely RCVS or fibromuscular dysplasia based on the angiographic appearance of vessels. A vasculitis workup, including vessel wall imaging, inflammatory markers, and rheumatologic panel (ANA, SS-A, SS-B, ANCA, ACE, cryoglobulin, antiphospholipid antibodies), was unremarkable. CSF analysis showed no pleocytosis and elevated protein (66 mg/dL) that was proportional to red blood cells (604,000). Presence of xanthochromia was not reported. CT angiogram of her chest, abdomen, and pelvis did not show vasculopathy. Ophthalmologic examination obtained to gain insight on the etiology of angiopathy showed a visual acuity of 20/20 in the right eye and 20/25 in the left eye. Dilated fundoscopy revealed tortuous retinal arterioles (Figure 4), raising concern for a genetic etiology for her vasculopathy. Genetic testing including COL4A1, COL4A2 (collagen type IV alpha 1 and 2), TREX1 (retinal vasculopathy with cerebral leukodystrophy), alpha galactosidase A (Fabry disease), FOXC1 (forkhead box C1), CST3 (cystatin C), cystathionine beta synthase, amyloid precursor protein, NOTCH3 (CADASIL), and HTRA1 (CARASIL) was negative. At 6-week follow-up, she had no neurologic deficits or recurrent symptoms, and her headache had resolved. A conventional angiogram was repeated 6 months later, showing no change to the corkscrew angiopathy seen on the initial study. She is planned for an annual ophthalmology follow-up.

Figure 4. Right-Eye Fundus Photograph Demonstrating Retinal Arteriolar Tortuosity With Normal Venuoles.

Discussion

Tortuosity of the cerebral vasculature is related to weakening of the arterial walls, often associated with age, diabetes, and atherosclerosis as well as a variety of genetic conditions.1 Cerebral corkscrew angiopathy specifically is a rare entity with few reported cases. One report found similar angiographic findings in a young woman who presented with a TIA.2 Another case report described primary cerebral Buerger disease as a cause of embolic stroke in a young patient with a history of tobacco use.3 Cerebral angiography in the latter case revealed multiple distal stenoses and occlusions with surrounding corkscrew appearing collaterals, similar to that which is seen peripherally in thromboangiitis obliterans.3 The appearance of the vasculature in this case was similar to ours; however, our patient had no history of tobacco use. A third case demonstrated similar tortuosity of small vessels on angiography in a young patient with a deep intracerebral hemorrhage, later found to have a COL4A1 mutation.4 In all these cases, there was no evidence of fibromuscular dysplasia or vasculitis.

In contrast to the 2 reported cases who presented with ischemic stroke, our patient presented with SAH. The nonaneurysmal SAH presentation in our patient may be due to the inherent structural fragility in the microvasculature comprising the corkscrew angiopathy segments, which predisposes these patients to hemorrhage.

Cerebral angiogram in our patient also showed absence of the left ophthalmic artery with opacification of the choroidal vasculature through external carotid artery collaterals. This is likely a chronic occlusion related to the same disease process, triggering changes in the retinal arterioles seen on the ophthalmologic examination. By contrast, an acute/acquired ophthalmic artery occlusion would result in complete vision loss as well as retinal pallor and optic nerve atrophy, which was not present in our patient. Tortuosity of retinal vasculature is associated with various genetic diseases. One study suggested that corkscrew angiopathy of the retina was present in a subset of patients with neurofibromatosis type 1, although our patient had no clinical manifestations of this disease; hence, genetic testing was not sent.5 Certain hereditary vasculopathies have also been associated with retinal vessel tortuosity, often in conjunction with stroke and leukoencephalopathy. Specifically, patients with the COL4A1 and COL4A2 mutations present with a systemic vasculopathy including retinal vessel tortuosity, nephropathy, and cerebral small vessel disease.6,7 In addition, patients with the TREX1 mutation can present with retinal vasculopathy and cerebral leukodystrophy.8 There was no leukodystrophy in our patient, and genetic testing for these mutations in addition to other causes of hereditary vasculopathy were negative. Finally, there is a reported association between IgA nephropathy and retinal vasculopathy, although an association with cerebral vasculopathy has not been reported.9

Though rare, corkscrew angiopathy can be associated with nonaneurysmal SAH. It is important to rule out an underlying aneurysm as the cause of SAH. The etiology for this vasculopathy remains unknown.

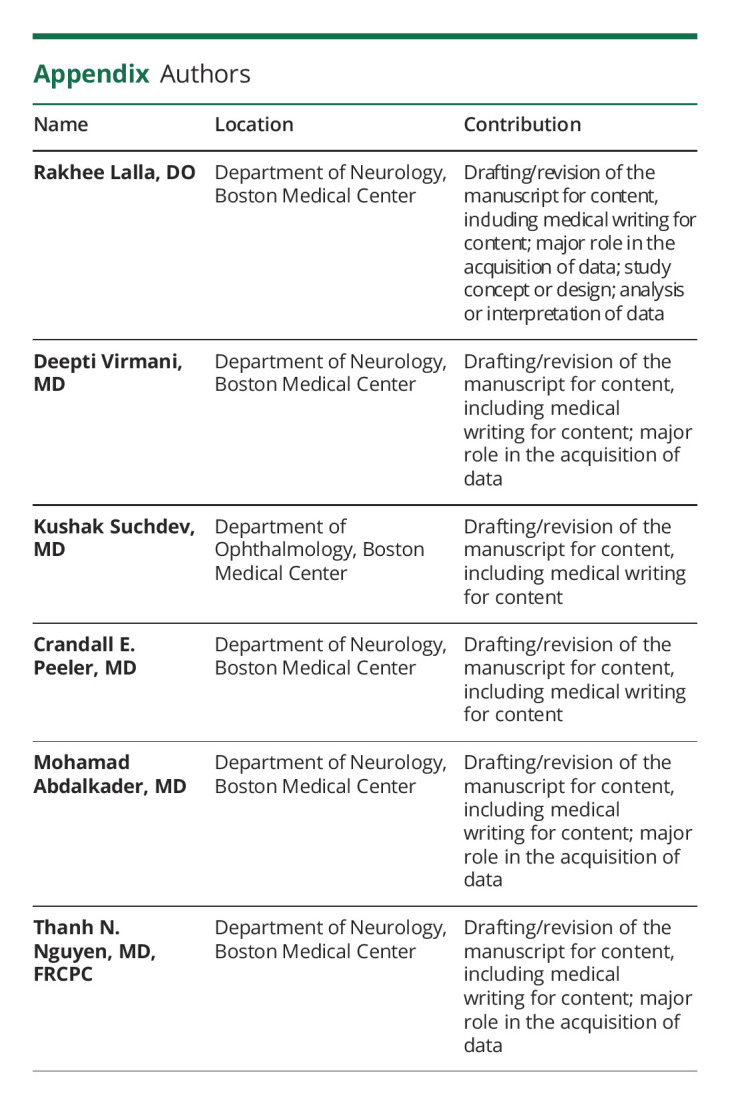

Appendix. Authors

Study Funding

The authors report no targeted funding.

Disclosure

The authors report no relevant disclosures. Full disclosure form information provided by the authors is available with the full text of this article at Neurology.org/cp.

References

- 1.Ciurică S, Lopez-Sublet M, Loeys BL, et al. Arterial tortuosity. Hypertension. 2019;73(5):951-960. doi: 10.1161/hypertensionaha.118.11647 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alurkar A, Karanam LSP, Oak SP. Corkscrew angiopathy of intracranial vessels in a young stroke patient: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2012;6(1):358. doi: 10.1186/1752-1947-6-358 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kaiser D, Leonhardt GK, Weiss N, et al. Pearls & oy-sters: primary cerebral buerger disease: a rare differential diagnosis of stroke in young adults. Neurology. 2021;97(11):551-554. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000012140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Coutts SB, Matysiak-Scholze U, Kohlhase J, Innes AM. Intracerebral hemorrhage in a young man. Can Med Assoc J. 2011;183(1):E61–E64. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.091496 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Muci-Mendoza R, Ramella M, Fuenmayor D. Corkscrew retinal vessels in neurofibromatosis type 1: report of 12 cases, 86; 2002. bjophthalmol.com [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zagaglia S, Selch C, Nisevic JR, et al. Neurologic phenotypes associated with COL4A1/2 mutations: expanding the spectrum of disease. Neurology. 2018;91(22):e2078–e2088. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000006567 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Plaisier E, Ronco P. COL4A1-Related Disorders Summary Clinical Characteristics; 1993. ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/ [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Søndergaard CB, Nielsen JE, Hansen CK, Christensen H. Hereditary cerebral small vessel disease and stroke. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2017;155:45-57. doi: 10.1016/j.clineuro.2017.02.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.el Matri K, Amoroso F, Zambrowski O, Miere A, Souied EH. Multimodal imaging of bilateral ischemic retinal vasculopathy associated with Berger's IgA nephropathy: case report. BMC Ophthalmol. 2021;21(1). doi: 10.1186/s12886-021-01935-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]