Abstract

We investigated the effect of government support of hotels on hotels' employee support (namely, health support, staff retention, and staff training) and consequently on employee job satisfaction and organizational commitment, through the moderating role of perceived overall organizational justice and ethical climate, during the COVID-19 pandemic. Using a quantitative approach and a framework that drew on the stakeholder and organizational support theories, we collected data from 669 employees in Egyptian hotels through a web-based survey. The results support the proposed framework and show a positive effect of government support through the strengthened perception of perceived overall organizational justice. Surprisingly, findings indicated that the association between job satisfaction and organizational commitment is significantly and negatively influenced by hotel ethical climate. Furthermore, job satisfaction partially mediates the association between hotels’ support of employees and organizational commitment. The study holds important implications for both theory and practice.

Keywords: COVID-19 pandemic, Government support, Hotels' employee support, Egypt

Graphical abstract

1. Introduction

There is ample evidence of the importance of the tourism industry for a country's economic development (Chen & Chiou-Wei, 2009; Senbeto & Hon, 2020). In 2018 the tourism sector accounted for 10.4% of global gross domestic product (GDP) and 319 million jobs—10% of total employment (World Travel and Tourism Council [WTTC], 2020). In Egypt, the tourism industry accounts for 37.7% of the country's GDP (Central Agency for Public Mobilization and Statistics [CAPMAS], 2018). Yet, it is widely acknowledged that tourism operations are characteristically susceptible to a range of extrinsic challenges (Aliperti et al., 2019).

More precisely, pandemic diseases are a leading disruptor of tourism (Jin, Qu, & Bao, 2019), since the industry depends on human mobility (Yang, Zhang, & Chen, 2020). The coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic has had a destructive economic impact all over the world (Goodell, 2020). The impact on hospitality and travel in particular has been strongly negative (Nicola et al., 2020). The World Tourism Organization (UNWTO) contends that tourism is the hardest hit sector (UNWTO, 2020), and a WTTC analysis (2020) found 75 million jobs worldwide are at risk, with one million jobs on the line daily, significantly affecting major source destinations.

Globally, hotel occupancy rates have been dramatically affected since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. Evidence from China reveals an 89% decrease in guest arrivals by the end of January (Airbnb, 2020). In Las Vegas, hotels belonging to the world-famous MGM chain were altogether closed down for the lock-down period (Hospitalitynet, 2020a). In much the same way, since March 2020, German hotels experienced a slump in occupancy of 36%, and the industry nearly collapsed in Rome, Italy, following a shocking 94% decrease in hotel occupancy (Hospitalitynet, 2020b).

Interestingly, it seems that the European hotel industry was able to achieve a partial recovery rather quickly. Having witnessed an all-time low occupancy rate of 11.1% in April 2020, European hotels were soon breathing a sigh of relief as occupancy jumped back up to 26.5% in July 2020. However, the damage was still severe (STR, 2020a). Despite the slowly improving situation, performance was still desperately poor, with occupancy being −66.4% of what it was in the previous year. Likewise, the average daily rate and revenue per available room were respectively −20.9% and −73.4% of what they were in July 2019 (STR, 2020a). The North American hotel industry also began to show strong signs of recovery by the end of the summer. In August 2020 occupancy had returned to 42.1%, though this represented a 45.2% decrease from the same period of the preceding year and was matched by a 59.4% reduction in revenue per available room (STR, 2020b). Unfortunately, the economic region of Africa was unable to recover as rapidly. By July 2020, the African hotel industry only experienced an occupancy rate of 16.9%, representing a 72.9% decrease from the same period of the previous year. Similarly, the average daily rate was −10.8% of what it was in July 2019, and the revenue per available room had dropped a disturbing 75.8% (STR, 2020c).

As for the context of the current study, after suffering heavy losses the Middle East's hotel industry began to report improvements by July 2020, with occupancy recovering to 35.3%. The bounce-back was so promising that, when set side by side with the European hotel industry, the economic shocks looked much less potent. When compared with July 2019, occupancy rates, average daily rates, and revenue per available room only decreased by 41.8%, 9.6% and 47.4% respectively (STR, 2020c). However, though the region was quickly making month-by-month improvements in the aftermath of the pandemic, the reality was that the Middle East had experienced its lowest levels of absolute occupancy and revenue per available room ever recorded (STR, 2020c). More focus on the Egyptian context: hotels cancelled bookings (Breisinger, Raouf, Wiebelt, Kamaly, & Karara, 2020), implemented layoffs practices and closures actions, and focused on safety and hygiene practices (Selim, Aidrous, & Semenova, 2020).

Notwithstanding the importance of pandemic management in hospitality and travel (Avraham, 2015; Israeli, Mohsin, & Kumar, 2011), very few studies have investigated government support of hotels (and by extension, hotel employees) during periods of crisis, for an exception, see Blake and Sinclair (2003). Given that, in times of crisis, government support is so critical for both businesses (Hung, Mark, Yeung, Chan, & Graham, 2018; Okumus & Karamustafa, 2005; Tse, So, & Sin, 2006; Wright, 2020, pp. 1–2) and employees (Henderson & Ng, 2004; Leung & Lam, 2004), especially those in the tourism and hospitality sectors, it is essential that investigations are conducted to determine the way in which crises and risks are managed by tourism organizations (Paraskevas & Quek, 2019). The current study seeks to make pioneering headway into this subject, in addition to exploring how hotels establish plans to address infectious diseases, and how they can work with governments to overcome crises (Jiang & Wen, 2020). Moreover, to generate better understanding of the internal effects of such responses, this research endeavors to examine how hotel reactions to crises influences the organizational commitment of hotel employees (Filimonau, Derqui, & Matute, 2020).

To achieve this aim, the authors of the current study developed and adopted a novel model, built on the foundations of popularly accepted theories (organizational support theory and stakeholder's theory), and tested it. With the model, the authors examined the organizational role of governmental support on hotels (health support, staff retention, staff training); the influence of employees' job satisfaction on organizational commitment; the moderating role of both perceived overall organizational justice and ethical climate on the relationship between employees' job satisfaction and organizational commitment; and the mediating role of job satisfaction. The complex model requires SEM analysis to be analyzed and tested, and thus WarpPLS 7.0 was used.

The current study was initiated on the recommendations of Ritchie and Jiang (2019), who affirmed that greater understanding of the effectiveness and efficiency of government policies was needed. To contribute towards correcting this lack of knowledge, the current study has focused on the subject of future tourism preparedness, which has also been specifically identified as a critical topic in need of further research (Aliperti et al., 2019). The importance of such research has been underscored by the devastating economic effects of the COVID-19 pandemic (Ocampo & Yamagishi, 2020) which has left innumerable businesses in the hotel sector on the brink of bankruptcy (Hang, Aroean, & Chen, 2020), and left the future of many in society worryingly bleak. Furthermore, to provide the industry with more practical insights, the current research also focused on the subject of human resource management strategies in times of crises. As employees represent a major cost to hotel organizations (Ritchie & Jiang, 2019), especially during times of reduced business performance, hotel managers are in need of recommendations that can help them maintain their businesses. Therefore, the authors of the current study examined staff retention, as a component of hotels’ support of employees during crises times, to identify the existence of any differences, of this consistent challenge (McGinley, Hanks, & Line, 2017), with the pre-pandemic world.

Recognizing the importance of individuals' job satisfaction (Thakur, Vetal, & Bhatt, 2020), organizations’ ongoing operations (Mehri, Iqbal, Hekmat, & Ishaq, 2011), contractual obligations (Hakimian, Farid, Ismail, & Nair, 2016), justice (Pieters, 2018), and maintenance of an ethical climate (Karatepe & Agbaim, 2012), Vardarlıer (2016) suggested organizations should avoid dismissing employees during a crisis by renegotiating wages, reorganizing work hours, and revoking rewards and bonus payments. The significance of ethical climate and perceived overall organizational justice has been well established by many researchers. The two variables have been well studied in a range of different sectors and industries, such as hotels (Haldorai, Kim, Chang, & Li, 2020; Karatepe & Agbaim, 2012; Vacziova, 2016), telecommunications (e.g., Fein, Tziner, Lusky, & Palachy, 2013), financial organizations (e.g., Elçi, Karabay, & Akyüz, 2015), and in insurance and medical contexts (Boudrias et al., 2010). But never before have they been studied in times of crises. Thus, the current study has contributed immensely to the body of knowledge surrounding the subjects of ethical climate and perceived overall organizational justice by exploring them in an entirely new context.

Similarly, as previous research has shown, in addition to the context it is applied in, the mapping of a variable can have a huge bearing on its impact. For example, although some have indicated that ethical climate has positive outcomes (e.g. Danish, Draz, & Ali, 2015; Filipova, 2011; Jyoti, 2013; Karatepe & Agbaim, 2012; Schwepker, 2001; Zagenczyk, Purvis, Cruz, Thoroughgood, & Sawyer, 2020), others have found it rather more impotent (Tanner, Tanner, & Wakefield, 2015). Therefore, in a novel approach, the authors have examined the moderating role of ethical climate on the relationship between hotels’ employee support and employee job satisfaction, and on the relationship between employee job satisfaction and organizational commitment, within the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. This has been done to determine whether ethical climate always strengthens these relationships.

literature on actual practices and available government support to forestall redundancies is lacking, leaving many important questions open: Should governments support the hotel sector during pandemics? What processes (or channels) of support are accessible to hotel workers during a pandemic? What moderating role do perceive overall organizational justice and an ethical climate play in the relationship between hotels’ support of employees and employee outcomes?

Drawing on the stakeholder theory (Friedman & Miles, 2002) and the organizational support theory (OST) (Eisenberger, Huntington, Hutchison, & Sowa, 1986), we investigate the effect of government support on hotels' employee support (specifically, hotel management's support of health initiatives, staff retention, and staff training) and subsequently on employee job satisfaction and organizational commitment, through the moderating role of perceived overall organizational justice and ethical climate. The study explores this matter in Egyptian hotels, seeking to contribute to the hospitality management literature by (1) highlighting the link between government support, hotels' support for their employees, and employee job satisfaction and organizational commitment during the COVID-19 pandemic and (2) revealing the concepts of hotels' support for employees and governmental support through the stakeholder theory and the OST. To the best of our knowledge, this study is one of the first to integrate these theories to explain employee behavior during a pandemic situation.

2. Conceptual framework and hypotheses

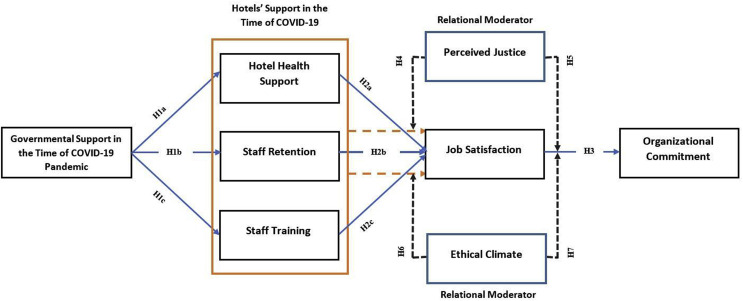

The conceptual framework (see Fig. 1 ) is grounded in two theories: the stakeholder theory and the OST. Based on Friedman and Miles (2002), the stakeholder theory (recognizes that all organizations have stakeholders—groups or people who have a legal interest in the substantive and procedural aspects of the organization's activity—such as managers, the government, shareholders, suppliers, employees, and customers, among others. More significantly, the theory purports that organizational policies, structures, and decisions should be consistent with the interests of all stakeholders (Friedman & Miles, 2002). This theory is based on trust and cooperativeness (Jones, 1995).

Fig. 1.

The Conceptual Framework. H = hypothesis.

According to Eisenberger et al. (1986), the OST suggests that employees will be committed to an organization if they perceive that the organization is committed to them. Perceived organizational support refers to the extent to which staffs recognize that their firm values the achievements of employees and ensures their well-being. According to Rhoades and Eisenberger (2002), organizational rewards, fairness, supervisor support, and suitable job conditions are critical for employees perceived organizational support and determine the quality of job satisfaction, performance, and organizational commitment.

The organizational support theory suggests that organizations (e.g., hotels) can positively influence employee job satisfaction and loyalty by creating an ethical and fair climate. Yet to date, there has been no empirical evidence to validate these claims.

2.1. Government support of hotels, and hotels’ support of employees

2.1.1. The relationship between government support and hotels’ support of employees' health

As asserted by Wright (2020, pp. 1–2), the tourism industry needs government stimulus packages and interventions to reduce the harmful effects of COVID-19 on jobs and the economy. Hung et al. (2018) highlighted that collaboration between governments and the hotel industry is a must in pandemic times to control the spread of infectious diseases through regular checks on health and hygiene at hotels. In the same vein, it is necessary for health and tourism sectors to collaborate before launching anti-pandemic initiatives (Maphanga & Henama, 2019). As shown by Jamal and Budke (2020), effective communication between public health authorities and the tourism and hospitality industry has been essential during the COVID-19 pandemic as the industry has sought to develop a health strategy focused on, among other things, preventing virus transmission. Local health authorities, moreover, should be responsible for surveillance, monitoring, and treatment of those infected with the coronavirus and play a critical role in the hospitality sector's efforts to prevent coronavirus outbreaks in the workplace (World Health Organization[WHO], 2020, p. 31). In this regard, occupational safety and health authorities' help with such tasks as setting guidelines is vital for hotels to safeguard the health and safety of their employees (Rosemberg, 2020). Overall, the stakeholder theory suggests a positive relationship between governments and organizations (Friedman & Miles, 2002). Thus, we hypothesize the following:

H1a

Government support has a significant effect on hotels' health and hygiene support.

2.1.2. The relationship between government support and staff retention

Although experts (e.g., Vaccaro, Getz, Cohen, Cole, & Donnally, 2020) have recommended avoiding employee layoffs during the COVID-19 pandemic, many people have lost their jobs all over the world (WTTC, 2020). Hotels have implemented employee layoffs before because of poor financial situations during crises (Pappas, 2018). For instance, during the severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) pandemic of 2003, hotels terminated employee contracts, implemented unpaid leave, and reduced salaries (Henderson & Ng, 2004; Leung & Lam, 2004). But Israeli and Reichel (2003) concluded that the least desirable crisis management practice for hospitality managers is to replace employees. More importantly, Blake and Sinclair (2003) found that a government policy of subsidies and tax reduction for the tourism and hospitality sector is critical to preserving jobs during a crisis. During the SARS pandemic, for instance, government financial support was key to restaurant managers being able to reduce costs without staff layoffs (Tse et al., 2006).

Thus, government support through wage subsidies is important for organizations to retain their staff during a crisis (Bruhn, 2020). Some governments have taken this route in the current COVID-19 pandemic. In Egypt, for instance, the government has provided the tourism sector with financial incentives to retain employees (El-Khishin, 2020). As mentioned earlier, a positive relationship between governments and organizations is proposed by stakeholder theory (Friedman & Miles, 2002). Hence, we presented:

H1b

Government support has a significant effect on staff retention.

2.1.3. The association between government support and staff training

Even though staff training is important for hotels (Dhar, 2015), Bruhn (2020) confirmed that it is costly. Therefore, hotels often prefer to postpone personnel training during crises (Pappas, 2018) when they do not receive government support (Tse et al., 2006). For example, lacking government support of the tourism industry during and after the economic crisis of 2001, many hotels in Turkey reduced their budgets for staff training (Okumus & Karamustafa, 2005). In the other side, during the SARS pandemic, the government of Singapore provided hotels with training programs for staff (Henderson & Ng, 2004). Guidelines from public health authorities can have a profound impact on hotels’ efforts to train employees and protect them from COVID-19 (WHO, 2020, p. 31). Taking these results into account, stakeholder theory supports the emphatic relationship between government and organizations (Friedman & Miles, 2002). The following hypothesis is proposed:

H1c

Government support has a significant effect on staff training.

2.2. Hotels’ employee support and employee job satisfaction

2.2.1. The relationship between hotel support of employees' health and employee job satisfaction

Given that many injuries and accidents occur in the workplace (Okun, Guerin, & Schulte, 2016), it is essential that organizations support their employees' health and safety (Söderbacka, Nyholm, & Fagerström, 2020). For example, to ensure the safety and well-being of staff during an infectious disease crisis, Henderson and Ng (2004) recommended hotels activate their emergency procedures, perform health screening of staff, and implement cleanliness and disinfection protocols. In addition, in reference to the SARS outbreak, Leung and Lam (2004) concluded that all hotel staff were informed with health instructions for avoiding infection in accordance with health authority recommendations. In this respect, hotels install new hygiene equipment including special air filters, chemical sterilizers, masks, and gloves (Kim, Chun, & Lee, 2005). Yet very few studies have focused on the association between a healthy work environment and job satisfaction and intention to leave. In one recent study in a medical context, Salehi, Barzegar, Yekaninejad, and Ranjbar (2020) pointed out that a healthy work environment can lead to higher employee job satisfaction and reduce employees' intention to leave an organization. More crucially, from a practical perspective, job satisfaction can be achieved by implementing such practices as healthcare services for employees in hotels, for instance, offering health insurance or healthcare coverage (i.e., paying for some or all of employees’ healthcare) (Elkhwesky, Salem, & Barakat, 2019). On the basis of the aforementioned arguments, the organizational support theory implies that organizations can positively influence employee job satisfaction (Rhoades & Eisenberger, 2002). The following hypothesis is proposed:

H2a

Hotel support of employee health has a significant effect on job satisfaction.

2.2.2. The association between staff retention and employee job satisfaction

In tough periods, staff retention is highly important for organizations to avoid the bad effects of losing employees on quality, productivity, and profitability (Noor, Zainuddin, Panigrahi, & Rahim, 2020; Rombaut & Guerry, 2020). Staff retention is a part of organizational support (Israeli & Reichel, 2003) that is positively correlated with job satisfaction (Kim, Leong, & Lee, 2005). In a hotel context, Yang, Wan, and Fu (2012) found that the reasons why employees were dissatisfied and wanted to leave their jobs fell into five categories: benefits and salary, responsibilities and work style, emotional conditions, work content, and organizational factors. Promoting work–life balance is an employee-retention strategy that increases employee job satisfaction and organizational commitment (Deery & Jago, 2015). Hedberg and Helnius (2007) indicated that organizations can improve their employees’ job satisfaction by implementing such retention strategies as fair rewards and benefits, effective communication, and proper work environment. Al Ahad, Khan, and Rahman (2020) found a significant and positive link between employee retention strategies and job satisfaction. Thus, the following hypothesis is formulated:

H2b

Staff retention has a significant effect on job satisfaction.

2.2.3. The association between staff training and job satisfaction

It is crucial for job satisfaction (Owens, 2006). This link is stronger in hospitality organizations than in other domains (Jaworski, Ravichandran, Karpinski, & Singh, 2018). Training is significant not only for managers leading their employees (DiPietro, Moreo, & Cain, 2020) but also for improving employee job satisfaction and morale (Hafeez & Akbar, 2015). Reinforcing this statement, few training opportunities for employees was found to cause lower satisfaction (Hsiao, Ma, & Auld, 2017). In the hospitality industry, poor training can lead to staff turnover, which is significantly and positively influenced by job dissatisfaction (Ann & Blum, 2020; Poulston, 2009). Hospitality managers can improve employees’ job satisfaction by rotating them through similar positions as well as teaching them new skills (Ann & Blum, 2020). Considering this relationship, the following hypothesis is formulated:

H2c

Staff training has a significant effect on job satisfaction.

2.3. The mediating role of job satisfaction and its link with organizational commitment

Basically, job satisfaction has been described as an individual's general attitude towards their job (Knoop, 1995). As noted by Thakur et al. (2020), job satisfaction has a profound importance for individuals because they spend a long period of their life in the workplace. Furthermore, job satisfaction is vital for organizations to achieve a competitive advantage (Mehri et al., 2011).

Organizational commitment refers to individuals’ long-term dedication to and identification with a specific organization (Knoop, 1995). A recent study of Hakimian et al. (2016) affirmed that organizations need committed employees to foster innovative behaviors, improve business performance, and achieve job success. Several studies have investigated the association between job satisfaction and organizational commitment (e.g., Thakur et al., 2020; Thuy & Van, 2020), finding that the former is critical to the latter (Manalo et al., 2020). This relationship was also found specifically in the hotel industry (López-Cabarcos, de Pinho, & Vázquez-Rodríguez, 2015). Thus, we proposed:

H3

Job satisfaction has a significant effect on organizational commitment.

H4

Job satisfaction mediates the association between hotels' support of employees and organizational commitment

2.4. The moderating role of perceived overall organizational justice

Perceived overall organizational justice refers to fairness in the workplace and is vital to work attitude, behavior, performance, and employee motivation in the hospitality industry (Wu & Wang, 2008). Organizational attitudes and behaviours are influenced by employees' perceptions of justice (Roch & Shanock, 2006). Pieters (2018) and Aeknarajindawat and Jermsittiparsert (2020) highlighted that employees' perceptions of organizational justice have a profound impact on their job satisfaction and organizational commitment (Aguiar-Quintana, Araujo-Cabrera, & Park, 2020, p. 100676).

Studies have found significant relationships between organizational justice, organizational commitment, and job satisfaction (e.g., Bilgin & Demirer, 2012; Jehanzeb & Mohanty, 2019; Loi, Hang-Yue, & Foley, 2006). Perceived organizational support and organizational justice are important for employee commitment (Zhao, Xu, Peng, & Matthews, 2020). In the hotel industry, Vacziova (2016) revealed that organizational commitment was significantly influenced by perceived organizational support and perceived overall organizational justice, López-Cabarcos et al. (2015) found that organizational commitment depended mainly on perceived overall organizational justice and job satisfaction, and Cho and Park (2019) argued that organizational support had a positive impact on employee job satisfaction. Wu and Wang (2008) further found that perceived overall organizational justice was critical to hotel employees’ pay satisfaction.

Employees' perception of overall organizational justice in interpersonal treatment from top management, the allocation of rewards, and in the evaluation are important for their trust in superiors (Montañez-Juan, García-Buades, Sora-Miana, Ortiz-Bonnín, & Caballer-Hernández, 2020). In this vein, employees feel satisfied when be treated in a fair manner in the workplace. Hence, employees' perception of overall organizational justice is vital for hotel employees' job satisfaction (satisfaction with pay and supervision), and their turnover intentions (DeConinck, 2010). Overall, when employees feel that they have been treated fairly in rewards allocated and in the method that they were allocated, they are more satisfied with their pay and supervisor. Considering these findings, the following hypotheses are proposed:

H5

Perceived overall organizational justice moderates the association between hotels' employee support and job satisfaction.

H6

Perceived overall organizational justice moderates the association between job satisfaction and organizational commitment.

2.5. The moderating influence of ethical climate

Victor and Cullen (1988; cited in Elçi & Alpkan, 2009, p. 298) defined ethical climate in an organization as “shared perceptions of what ethically correct behavior is and how ethical issues should be handled.”. Ethical climate dimensions, as identified by Victor and Cullen (1988), are "caring", "rules", "law and code", "independence", and "instrumentalism". Ferrell and Skinner (1988) confirmed that implementing a code of ethics in an organization was critical for fostering ethical behaviour. Ethical climate is important an important factor for employees (Haldorai et al., 2020), especially in maintaining their positive attitudes and behaviours (Elçi et al., 2015). In the hospitality industry, an ethical climate can greatly improve employees' job satisfaction and performance (Karatepe & Agbaim, 2012). Moreover, it can affect some of the antecedents of job satisfaction (Tanner et al., 2015). Unethical climate has a negative impact on employee performance (Elçi et al., 2015). As indicated by Riggle (2007), perceived organizational support and ethical climate are important aspects of organizational climate. As exhibited by Elçi and Alpkan (2009), there is a positive link between ethical climate and employees' job satisfaction. In the hotel industry, findings of Karatepe and Agbaim (2012) support the idea that perceived ethical climate strongly affects employee job satisfaction.

More importantly, several studies have found a positive relationship between ethical climate, job satisfaction, and organizational commitment (Danish et al., 2015; Filipova, 2011; Jyoti, 2013; Schwepker, 2001). Some have even demonstrated how ethical climate moderates the relationship between job satisfaction and organizational commitment (Zehir, Müceldili, & Zehir, 2012). Filipova (2011) also highlighted how organizations with greater ethics and support usually benefit from more positive outcomes, such as greater employee retention. Zagenczyk et al. (2020) concluded that ethical climate strengthened the positive relationship between perceived organizational support and organizational commitment. In the hotel industry, ethical climate and perceived organizational support have been linked with job satisfaction (Cheng, Yang, Wan, & Chu, 2013).

Ethical climate in the workplace can reduce employees' role stress that can minimize emotional exhaustion and turnover intention, and increase job satisfaction (Mulki, Jaramillo, & Locander, 2008). Based on Mulki, Jaramillo, and Locander (2006), ethical climate is an important predictor of trust in supervisor, job satisfaction, and organizational commitment. For more explanation, ethical climate is vital for minimizing employees' risk of violating what the organization expects and maximizing employees' sense of comfort and security. This feeling is resulted from providing employees with cues about appropriate ethical behaviours in an organization. Moreover, this feeling causes a great level of job satisfaction and organizational commitment. Given the results of previous researchers, the following hypotheses are proposed:

H7

Ethical climate moderates the association between hotels' employee support and job satisfaction.

H8

Ethical climate moderates the association between job satisfaction and organizational commitment.

3. Method

3.1. Procedure and sample

Adopting a positivist research philosophy, the authors utilised a quantitative approach to validate the suggested framework and quantitative data, which was gathered using a questionnaire administered to hotel employees, from various levels, in Egypt. To empirically test the proposed hypotheses, we collected data through a web-based survey because of the COVID-19 pandemic restrictions (e.g., the need for social distancing). Olson (2010) recommended using a sample size of at least 6 experts in the pre-testing phase of empirical research, to ensure consistency in detecting prevalent problems. Accordingly, after developing the questionnaire, the authors of the current study approached 7 academic experts and asked them to review the survey, paying special attention to the readability and clarity of the questions, as well as the validity of the items, scales and content. Based on their comments, slight changes were made to the format of the questionnaire and the explanations of each section, but no alterations were made to the scales. The changes focused on the insertion of detailed descriptions introducing each section to explain the purpose of the questions. These were especially important for the section related to gender and employee contract. The experts reported no issues with the readability, the logical order, or the length of the questionnaire.

Subsequently, a pilot test was conducted to check for face validity and to reduce measurement error, in addition to identifying ambiguous eligibility criteria and misconceptions of survey items. Based on the recommendations of Nunnally (1994), the pilot survey was issued to 30 hotel employees one week before the main data collection was scheduled to take place. Based on these results, minor editing changes were made to the items of the survey. However, following a Cronbach's alpha test, no items were excluded from the intended scale, as the construct scales all showed acceptable levels of reliability in the pilot test (>.80), exceeding the 0.70 level as recommended by Nunnally (1994).

The final data collection took place between the months of April and May 2020. To collect the data, the authors first obtained the email addresses of all the human resources directors in the hotels listed in the Egyptian Hotel Guide, published the Egyptian Hotel Association (2020). To ensure a representative sample, we then emailed the directors to get permission to send the surveys to their hotels and to explain the purpose of the study, with an attached URL hyperlink. The last step was to follow up on the survey invitation process. The timeline was divided into 6 weeks as follows: Week 1 (primary email invite), Week 2 (first follow-up email), Weeks 3 till 5 (2nd follow-up email), and Week 6 (survey closes).

It would have been challenging to choose our sample from the population directly. Therefore, convenience sampling was employed to collect the data (San Martín & Herrero, 2012). Despite the possibility of representativeness and generalizability issues that can arise with this type of sampling, convenience sampling is considered beneficial when the population is very large (Etikan, Musa, & Alkassim, 2016; Nowiński, Haddoud, Lančarič, Egerová, & Czeglédi, 2019). Furthermore, it is frequently employed in tourism and hospitality studies (Jensen & Luthans, 2006; Elbaz, Haddoud, Onjewu, & Abdelhamied, 2019; Elkhwesky et al., 2019; Elhoushy, Salem, & Agag, 2020) because of the industry's difficult nature, which, in this case, was exacerbated by the difficulties of the Egyptian context (Elbaz, Salem, Elsetouhi, & Abdelhamied, 2020). Non-probability sampling has been found to provide robust data when high engagement levels are accomplished (Coviello & Jones, 2004).

According to CAPMAS (2020), there are 782,900 employees in accommodation and food services in Egypt. If, following Saunders, lewis, and Thornhill (2016), one chooses an error margin of 5% and the population size is between 100,000 and 1,000,000, then the expected sample size is 383. We selected a sample of 700 hotel employees. In aggregate, 687 completed questionnaires were received, of which 669 were valid and only 18 were counted void.

3.2. Measures

Government support of hotels was measured with 12 items derived from questionnaires developed by Blake and Sinclair (2003), Hung et al. (2018), and Israeli et al. (2011). In the present study, government support can be through providing tax allowances and loans (Blake & Sinclair, 2003; Israeli et al., 2011), which is crucial for businesses and their workforces during crises (Israeli et al., 2011; Okumus & Karamustafa, 2005; Tse et al., 2006). Hotels' health and hygiene support was measured with 11 items adapted from Hung et al. (2018), Kim, Leong, and Lee (2005), and Tse et al. (2006). The instruments for the measurement of hotels' staff retention (13 items) and training (four items) were initially adapted from the work of Santana-Hernández (2016). Staff training aims at assisting them to obtain expertise and competency as well as increasing their capability (Santana-Hernández, 2016). In terms of staff retention, Santana-Hernández (2016) defined staff retention as avoiding laying employees off, preventing workforce reduction, and maintaining them in an enterprise by implementing proper practices. Organizational commitment was measured with six items derived from Allen and Meyer (1990). They defined commitment as “employees' emotional attachment to, identification with, and involvement in, the organization”. Job satisfaction was assessed using the six-item scale of Brown and Peterson (1993). For the purpose of the present study, job satisfaction can be defined as employee satisfaction related to various job aspects including work itself, remuneration, compensation, support, supervisor, and operational policies (Brown & Peterson, 1993). Three items were adapted from Ambrose and Schminke (2009) to measure perceived overall organizational justice, and five items were extracted from Schwepker (2001) to measure ethical climate. As a broader measure, perceived overall organizational justice is the comprehensive assessment of the general fairness of an organization (Ambrose & Schminke, 2009). In addition, ethical climate could be created in an organization by carrying out and enforcing codes of ethics and policies concerning ethical behavior, punishing unethical behavior, and rewarding ethical behavior (Schwepker, 2001). Participants responded on 5-point Likert-type scales of 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). Full details are presented in the Appendix. To ensure the reliability of the results, the research controlled for gender, age, type of employment contract, seniority in the hotel, occupation, level of education, type of hotel, and the number of hotel rooms.

4. Data analysis and results

The sample characteristics are shown in Table 1 . Note, the sample being predominantly male (90.1%) is not surprising, given that in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region, men regularly control the work. Most participants were 26–35 years old (42.9%). As for type of employee contract, the majority were temporary (71.3%). The highest proportion of participants were employed as entry-level staff (35.7%). As of education, a greater part of respondents held a bachelor's degree (70.4%). The vast majority of hotels were representatives of chains (65.9%). The majority of hotels had 150-300 rooms (88%).

Table 1.

Sample characteristics.

| Characteristic | N = 669 | % |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 603 | 90.1 |

| Female | 66 | 9.9 |

| Age (years) | ||

| 25 and under | 70 | 10.5 |

| 26–35 | 287 | 42.9 |

| 36–45 | 215 | 32.1 |

| 46 and over | 97 | 14.5 |

| Seniority in the hotel | ||

| less than 1 year | 156 | 23.3 |

| 1–5 years | 303 | 45.3 |

| Greater than 5 years | 210 | 31.4 |

| Type of employee contract | ||

| Permanent | 192 | 28.7 |

| Temporary | 477 | 71.3 |

| Occupation | ||

| Manager | 202 | 30.2 |

| Supervisor | 228 | 34.1 |

| Entry-level staff | 239 | 35.7 |

| Level of education | ||

| Secondary education | 166 | 24.8 |

| University education | 471 | 70.4 |

| Master's or PhD | 32 | 4.8 |

| Type of hotel | ||

| Independent | 228 | 34.1 |

| Chain | 441 | 65.9 |

| Number of hotel rooms | ||

| Under 150 | 80 | 12.0 |

| 150–300 | 233 | 34.8 |

| 301–450 | 141 | 21.1 |

| Over 450 | 215 | 32.1 |

A principal axis factor analysis was applied to look for potential common method bias. The results showed that the prime factor accounted for less than 50% of variance. Thus, a common method bias had no issue in this dataset (Chin, Thatcher, & Wright, 2012). Multicollinearity tests affirmed that all variables had variance inflation factor (VIF) values of less than 3.20.

The advanced multivariate partial-least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) technique was applied to test the research model and hypotheses using WarpPLS (Version 7.0; Kock, 2020). This technique does not assume normality and comprises the estimation of two discrete models: the measurement model (outer model) and the structural model (inner model; Jarvis, Mackenzie, & Podsakoff, 2003). Because SEM entails that data did not violate the presumption of normality, the data set was checked. Skewness ranged from −1.403 to - 0.231 and kurtosis from −0.435 to 1.825.

4.1. The measurement model

To test the measurement model, we first tested the reliability (internal consistency) and convergent validity. Hence, factor loadings, composite reliability (CR), Cronbach's alpha, average variance extracted (AVE), and variance inflation factor (VIF) were measured. Thereafter, the items' loadings were employed to assess construct validity (see Appendix). Table 2 displays the CR values, which represent the degree to which the instrument items explain the instrument. These surpassed the acceptable level of 0.7 (range 0.867–0.944), which indicates adequate internal consistency. AVE, the overall amount of variance in the indicators accounted for by the latent construct, surpassed the acceptable level of 0.5 (range, 0.583–0.772), which means good convergent validity (Hair, Hult, Ringle, & Sarstedt, 2016). Additionally, all variables had VIF values of less than 3.3 (range 1.183–3.266), which is ideal and indicates the absence of both multicollinearity and common method bias (Kock & Lynn, 2012).

Table 2.

Reliability and convergent validity.

| Variable | Composite reliability | Cronbach's alpha | AVE | VIF |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Government support | 0.933 | 0.920 | 0.583 | 1.183 |

| Hotels' health and hygiene support | 0.896 | 0.844 | 0.683 | 2.825 |

| Hotels' staff retention | 0.867 | 0.795 | 0.622 | 3.102 |

| Staff training | 0.933 | 0.893 | 0.823 | 2.704 |

| Job satisfaction | 0.910 | 0.869 | 0.718 | 1.692 |

| Organizational commitment | 0.923 | 0.889 | 0.751 | 1.755 |

| Perceived overall organizational justice | 0.953 | 0.926 | 0.872 | 3.126 |

| Ethical climate | 0.944 | 0.926 | 0.772 | 3.266 |

Next, the square roots of AVE (AVEs) were measured which indicates the level to which the measures are not a representation of some other variables and showing satisfactory discriminant validity (see Table 3 ). A recent critique of the Fornell and Larcker (1981) measures suggested they probably do not identify a lack of discriminant validity in regular study samples (Henseler, Ringle, & Sarstedt, 2015). Therefore, Henseler et al. (2015) proposed an alternative approach that focuses on the multitrait-multimethod matrix to estimate discriminant validity: the heterotrait-monotrait (HTMT) ratio of correlations (Henseler et al., 2015). This novel method was employed to verify discriminant validity, and outcomes are presented in Table 4 . If the HTMT value is larger than 0.85, then discriminant validity is a problem (Kock, 2020). All study constructs have values less than 0.85 (range, 0.189–0.798), indicating satisfactory discriminant validity.

Table 3.

Discriminant validity.

| Construct | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Government support | (0.763) | |||||||

| 2. Hotels' health and hygiene Support | 0.375 | (0.826) | ||||||

| 3. Hotels' staff retention | 0.303 | 0.756 | (0.789) | |||||

| 4. Staff training | 0.290 | 0.703 | 0.757 | (0.907) | ||||

| 5. Job satisfaction | 0.270 | 0.511 | 0.492 | 0.457 | (0.847) | |||

| 6. Organizational commitment | 0.172 | 0.509 | 0.501 | 0.529 | 0.573 | (0.867) | ||

| 7. Perceived overall organizational justice | 0.256 | 0.505 | 0.526 | 0.534 | 0.670 | 0.694 | (0.934) | |

| 8. Ethical climate | 0.217 | 0.490 | 0.538 | 0.559 | 0.595 | 0.725 | 0.731 | (0.879) |

Table 4.

Heterotrait-monotrait (HTMT) ratios of correlation.

| Construct | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Government support | ||||||||

| 2. Hotels' health and hygiene Support | 0.429 | |||||||

| 3. Hotels' staff retention | 0.357 | 0.818 | ||||||

| 4. Staff training | 0.324 | 0.740 | 0.892 | |||||

| 5. Job satisfaction | 0.300 | 0.599 | 0.589 | 0.520 | ||||

| 6. Organizational commitment | 0.189 | 0.583 | 0.588 | 0.592 | 0.649 | |||

| 7. Perceived overall organizational justice | 0.275 | 0.573 | 0.612 | 0.587 | 0.745 | 0.762 | ||

| 8. Ethical climate | 0.234 | 0.554 | 0.629 | 0.615 | 0.663 | 0.798 | 0.788 |

Note. HTMT ratios are good if < 0.90, best if < 0.85.

4.2. The structural model

Hair et al. (2016) proposed evaluating goodness-of-fit indices, beta (β), corresponding t values, effect sizes (f 2), R 2, and predictive relevance (Q 2). More recently, Henseler, Hubona, and Ray (2016) suggested using the standardized root mean square residual (SRMR) as the only estimated model fit criterion. An SRMR value of 0 would indicate a perfect fit, and commonly, an SRMR value of ≤0.1 is considered acceptable for PLS path models (Kock, 2020). Our SRMR of 0.068 implied an acceptable model fit.

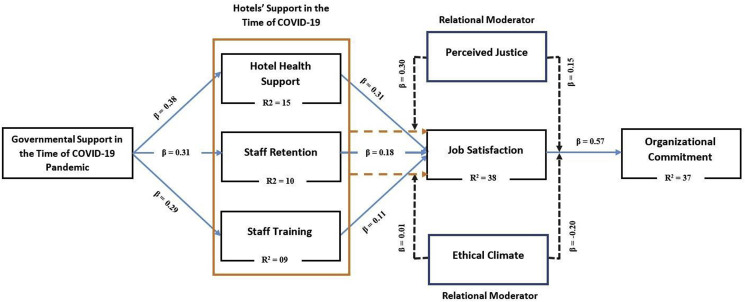

Table 6 depicts the results related to the study's hypotheses. The p values and the path coefficients (betas) of the structural model are shown in Fig. 2 . Government support in the time of COVID-19 positively and significantly affected the hotels' health and hygiene support (β = 0.381; p < 0.01), staff retention support (β = 0.309; p < 0.01), and staff training support (β = 0.294; p < 0.01). Thus H1a, H1b, and H1c are supported. In addition, health and hygiene support, staff retention support, and staff training support positively and significantly affected job satisfaction (β = 0.312; p < 0.01, β = 0.176; p < 0.01, and β = 0.111; p < 0.01, respectively). Thus H2a, H2b, and H2c are supported. Similarly, job satisfaction was found to have a positive and significant effect on organizational commitment (β = 0.574; p < 0.01). Therefore, H3 is supported.

Table 6.

Hypothesis-testing summary.

| No. | Hypothesis | Beta | t | Decision | f2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1a | Government support has a significant effect on hotels' health and hygiene support | 0.381 | 10.262** | Supported | 0.145 |

| 1b | Government support has a significant effect on staff retention | 0.309 | 8.259** | Supported | 0.096 |

| 1c | Governmental support has a significant effect on staff training | 0.294 | 7.856** | Supported | 0.087 |

| 2a | Hotel support of employee health has a significant effect on job satisfaction | 0.312 | 8.336** | Supported | 0.163 |

| 2b | Staff retention has a significant effect on job satisfaction | 0.176 | 4.646** | Supported | 0.087 |

| 2c | Staff training has a significant effect on job satisfaction | 0.111 | 2.903** | Supported | 0.051 |

| 3 | job satisfaction has a significant effect on organizational commitment | 0.574 | 15.784** | Supported | 0.330 |

| 4 | Job satisfaction mediates the association between hotels' support of employees and organizational commitment | 0.231 | 9.274** | Supported | 0.133 |

| 5 | Perceived overall organizational justice moderates the association between hotels' support of employees and job satisfaction | 0.299 | 7.986** | Supported | 0.073 |

| 6 | Perceived overall organizational justice moderates the association between job satisfaction and organizational commitment | 0.150 | 3.950** | Supported | 0.037 |

| 7 | Ethical climate moderates the association between hotel support of employees and job satisfaction | 0.007 | 0.177 | Not supported | 0.002 |

| 8 | Ethical climate moderates the association between job satisfaction and organizational commitment | −0.197 | −5.211** | Supported | 0.028 |

**Critical t value for two-tailed tests: 1.960 (p < 0.01).

Fig. 2.

The structure model.

Furthermore, government support during the COVID-19 pandemic explained 15%, 10%, and 9% of variance in health and hygiene support, staff retention, and training support, respectively (R 2 = 0.15, 0.10, and 0.09), and hotel support explained 38% of the variance in job satisfaction generally (R 2 = 0.38). Additionally, job satisfaction explained 37% of the variance in organizational commitment (R 2 = 0.37). The R 2 values of 0.38 and 0.37 are greater than the 0.26 that Cohen (1988) recommended would signify a considerable model (Table 6 and Fig. 2). In addition, the effect size (f 2) indicates whether the effects specified by path coefficients are small, medium, or large. The values normally suggested are 0.02, 0.15, and 0.35, respectively (Cock, 2020). Table 6 reveals that all associations had a small or medium effect. In addition to measuring R 2 and f 2, it is also essential to measure Q 2 (Chin et al., 2012). If Q 2 is positive (i.e., >0), it indicates the model's predictive relevance for a particular construct, with higher Q 2 values indicating higher predictive relevance. The Q 2 values for hotels' health support and employee job satisfaction and organizational commitment are 0.133, 0.371, and 0.369, respectively. Q 2 values for the inner variables show a satisfactory predictive relevance (see Fig. 2).

4.3. Mediation analysis

As shown in Table 5 , job satisfaction exhibited a partial mediating effect between hotels’ support of employees (second order variable) and organizational commitment. The Variance Accounted For (VAF) verifies the size of the indirect effect linked to the total effect. Ultimately, the VAF estimates the power of the mediation in which VAF ranges between 0 and 100%, with values over 80% showing full mediation, within 20 and 80% partial mediation, and under 20% no mediation force (Hair et al., 2016). Hence, H4 is supported.

Table 5.

Synopsis of mediation results.

| Paths | Significance |

Confidence intervals |

VAF | outcome |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Direct effect | Indirect effect | 95% LL | 95% UL | |||

| Hotels' support of employees and organizational commitment (via job satisfaction) | 0.346** | 0.231** | 0.333 | 0.478 | 0.40 | Partially mediated |

**p < 0.01; LL = Lower level; UL=Upper level, VAF=Variance Accounted For.

4.4. Moderation analysis

The mechanism employed by the authors of the current study to test the moderating effect of perceived overall organizational justice and ethical climate was heavily influenced by the work of Kock (2020). Kock (2020) developed the WarpPLS 7.0 software that has since become universally adopted by other researchers (see, Elbaz, Haddoud, & Shehawy, 2018; Elbaz et al., 2020; Kock, 2020; Kock & Lynn, 2012). The authors followed Kock (2020) to assess the differences in path coefficients between the high-perceived overall organizational justice and ethical climate subgroup model and the low-perceived overall organizational justice and ethical climate subgroup model. The t-statistics have been calculated and are presented in Table 6 .

We assumed perceived overall organizational justice would have a moderating effect on the association between hotels' support of their employees and job satisfaction. To assess the likelihood of the moderating influence, hotels' support as a predictor and perceived overall organizational justice as a moderator were multiplied to generate an interaction construct (hotels' support of employees × perceived overall organizational justice) to predict job satisfaction. The predicted standardized path coefficients for the influence of the moderator on job satisfaction (β = 0.299; p < 0.01, f 2 = 0.073 [small effect]) were significant (see Table 6). Therefore, perceived overall organizational justice strengthened the positive association between hotels’ support of employees and job satisfaction (see Fig. 3 ) and hence, H5 is supported. We also assumed perceived overall organizational justice would have a moderating effect on the associations between job satisfaction and organizational commitment (see Table 6). The interaction between perceived overall organizational justice and job satisfaction was positively associated with organizational commitment (β = 0.150, p < 0.01, f 2 = 0.037 [small effect]). As shown in Fig. 4 , perceived overall organizational justice strengthened the positive link between job satisfaction and organizational commitment. Thus, H6 is supported.

Fig. 3.

The moderating role of perceived overall organizational justice in the association between hotels' employee support and job satisfaction.

Fig. 4.

The moderating role of perceived overall organizational justice in the association between job satisfaction and organizational commitment.

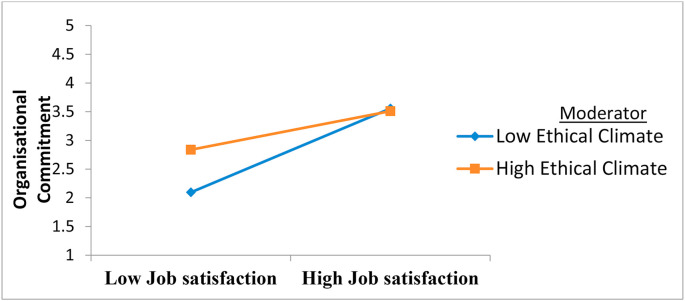

In contrast, we did not find that ethical climate moderated the relationship between hotels’ support of employees and job satisfaction (β = 0.007, p = 0.34, f 2 = 0.002 [no significant effect]). Thus, H7 is not supported. Ethical climate changed the positive association of job satisfaction and organizational commitment to a negative relationship (Table 6). The interaction between ethical climate and job satisfaction was negatively associated with organizational commitment (β = −0.197, p < 0.01, f 2 = 0.028 [small effect]). As presented in Fig. 5 , high ethical climate dampened the positive association between job satisfaction and organizational commitment. Accordingly, H8 is supported.

Fig. 5.

The moderating role of ethical climate in the association between job satisfaction and organizational commitment.

Regarding the control variables, the authors found that organizational commitment was unaffected by differences in gender (p = 0.053), professional categories (p = 0.170), seniority in the hotel (p = 0.122), level of education (p = 0.689), and number of hotel rooms (p = 0.136) organizational. In contrast, a significant relationship was found between the type of contract (permanent and temporary) and organizational commitment (p = 0.004). It was revealed that, employees who had permanent contracts felt greater job security and demonstrated stronger commitments towards their hotels. This finding is in line with Han, Moon, and Yun (2009) who likewise found that permanent employees exhibited higher levels of organizational commitment than temporary ones. Conversely, this finding is inconsistent with the work of De Cuyper and De Witte (2006) who indicated that there was no significant difference between temporary workers and permanent ones regarding organizational commitment.

5. Discussion and conclusion

Basically, the main objectives of this research were to explore (1) the effects of government support on hotels' support of their employees (namely, health support, staff retention, and staff training) as well as employee job satisfaction and organizational commitment during the COVID-19 pandemic, (2) the concepts of hotels' support of employees and governmental support” through the lens of the stakeholder theory and the organizational support theory, and (3) the moderating roles of perceived overall organizational justice and ethical climate. To achieve this aim, we proposed an integrative framework to explore the influence of these three types of employee support on employees' job satisfaction and organizational commitment in Egyptian hotels (N = 669). Overall, the research findings support the proposed framework and show that government support positively affects hotels' support of their employees, which in turn impacts employees’ job satisfaction and organizational commitment through the strengthening role of perceived overall organizational justice.

The findings show that, in the time of COVID-19, government support has positively and significantly impacted hotel employee health and hygiene support. These results are in line with numerous prior studies. For example, Wright (2020, pp. 1–2) asserted that the tourism and hospitality industry needs government stimulus packages and interventions, which play an indispensable role in combatting the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on jobs and the economy in general. Thus, it is absolutely crucial that the government continues to act to mitigate the detrimental influence of COVID-19 by providing support for hotels that are particularly at risk. This could take the form of financial (Blake & Sinclair, 2003) and political support for recovery measures aimed at the hospitality industry and health authority support (surveillance, monitoring, and treatment) to prevent outbreaks especially among employees (WHO, 2020).

Government support in the time of COVID-19 was also observed to have a strong positive and significant effect on staff retention, mitigating the economic threat posed by the COVID-19 outbreak. This is also in line with Bruhn (2020), who stated that government support through wage subsidies is imperative for firms to retain their employees. Hence, the Egyptian government should provide the tourism and hospitality sector with financial and moral incentives to retain employees. In the same direction, the findings also revealed that government support had a positive effect on staff training support, without which hotel management may have been forced to postpone staff training and reduce the budgets allocated to it, as has been documented in previous crises (e.g., in Turkey; Okumus & Karamustafa, 2005). Therefore, it should be appreciated that support from the health and safety authority is necessary to allow the hotel to continue providing training to employees safely, without increasing their risk to COVID-19 infection.

In addition, and in line with previous findings (Al Ahad et al., 2020; Elkhwesky et al., 2019; Rombaut & Guerry, 2020; Salehi et al., 2020), in the current study, hotel support for health and hygiene, employee retention, and employee training had a positive and measurable impact on job satisfaction. Moreover, the present results are in line with previous findings that training is vital for employees' organizational commitment and job satisfaction (Ann & Blum, 2020; López-Cabarcos et al., 2015; Owoyemi, Oyelere, Elegbede, & Gbajumo-Sheriff, 2011). In addition, the current study found that the more the hotels were perceived as supporting and valuing their employees, the higher the participants rated their job satisfaction and organizational commitment. Regarding the direct effect of employee job satisfaction on organizational commitment, the results suggest that job satisfaction has a positive and significant impact on organizational commitment. These results are in keeping with previous findings (Thakur et al., 2020; Thuy & Van, 2020).

As for the moderating role of perceived overall organizational justice in the association between hotels’ support of employees and job satisfaction, we found that perceived overall organizational justice strengthened the positive association. That is, there were positive perceptions among employees that reflected positive feelings toward decisions, decision makers, and managers in the hotel environment, which resulted in employee job satisfaction. These results are consistent with studies that found that employees' perceptions of organizational justice had a prominent role in their achieving job satisfaction (Aeknarajindawat & Jermsittiparsert, 2020; Pieters, 2018) and organizational commitment (Bakhshi, Kumar, & Rani, 2009; López-Cabarcos et al., 2015).

Contrary to our hypothesis, ethical climate was found to have no effect on the association between hotels' employee support and employee job satisfaction. This is not in line with Filipova's (2011), Jyoti's (2013), and Danish et al.’s (2015) findings, which suggested a significant link between ethical climate and job satisfaction and organizational commitment. The contrast in findings may be due to the somewhat unique context of the current study, being the COVID-19 pandemic. Accordingly, in a health crisis it is logical that support related to health and hygiene, staff retention, and training should receive greater priority than ethical climate (Henderson & Ng, 2004; Hu, Yan, Casey, & Wu, 2020; Leung & Lam, 2004; Rosemberg, 2020; Tse et al., 2006; Vaccaro et al., 2020). In normal times, however, it may very well be the case that ethical climate affects job satisfaction (Elçi & Alpkan, 2009; Karatepe & Agbaim, 2012), in addition to playing a role in employees' relationships with guests and their colleagues in the workplace.

Surprisingly, the current research revealed that there was a significant negative influence from hotel ethical climate on the association between job satisfaction and organizational commitment. That is, ethical climate dampened the positive association between job satisfaction and organizational commitment. This finding was not in line with the research of Schwepker (2001), who found that ethical climate was positively correlated with job satisfaction and organizational commitment. Therefore, it is essential to discourage unethical behavior in hotels by setting and implementing codes of ethics and ethics-related policies. Moreover, hotels are recommended to justify, to their employees, the reason for implementing codes of ethics and ethics-related decisions in the times of crisis, such as in the case of COVID-19. In addition, hotels should provide staff with opportunities to express their views about implementing codes of ethics, as well as the way in which they carried out, to avoid any biases between permanent and temporary staff. Reinforcing our result, an organizational climate that focuses on codes, rules, and laws may not motivate employees to speak up about work-related problems (Wang & Hsieh, 2013), and may therefore intensify dissatisfaction. Haldorai et al. (2020) affirmed that explaining and justifying job-related decisions was vital for increasing employee outcomes, and that it was important to apply policies and procedures in an unbiased manner. It could be that the negative impact of ethical climate is due to the tendency of employees to rely on their own personal values rather than adopt the codes of conduct established by their organizations (Blackwood & Chiarella, 2020).

As for the relational mediator of job satisfaction, the findings revealed that the relationship between hotels' employee support (staff retention, medical support, and training) and organizational commitment was partially mediated by employees’ job satisfaction. In the present study, the authors predicted that the positive effect of hotels' employee support would play an important role in achieving organizational commitment, though the effect would be dependent on an intermediate variable, such as job satisfaction. Yet, the results reveal that, while job satisfaction accounts for some of the relationship between hotels' employee support and organizational commitment, the mediation is not comprehensive.

5.1. Theoretical contribution

The theoretical contribution of this study is manifold. The research has been carried out to respond to the recent calls from other researchers to investigate the response of hotels to the COVID-19 pandemic and the resultant effects on organizational commitment (Filimonau et al., 2020), the effectiveness and efficiency of government policies and HRM strategies in times of crisis (Ritchie & Jiang, 2019), governments support for hotels (Hang et al., 2020), and to examine ethical climate, employee outcomes, organizational justice in hotels (Elçi et al., 2015; Haldorai et al., 2020). Even though most previous research was based on the stakeholder theory (Friedman & Miles, 2002) and the OST (Eisenberger et al., 1986), there have been no empirical studies during the COVID-19 pandemic. Consequently, to our knowledge, this study is one of the first to integrate these theories in such a context.

To date, despite the importance of government support, hotels' employee support, job satisfaction, organizational commitment, perceived overall organizational justice, and ethical climate, no other study in the tourism and hospitality field has yet analyzed the relationships between these variables in times of crisis. We addressed this gap in the literature by empirically analyzing these relationships, in addition to the roles hotels’ support of employees and the role of government support, during the COVID-19 pandemic, using an approach that combined the stakeholder and organizational support theories.

The current study adds to the stakeholder theory by confirming the importance of organizational policies, structures, and decisions as consistent with the interests of all stakeholders (Friedman & Miles, 2002). Based on the stakeholder theory, the authors have demonstrated how the Egyptian government has set policies and taken decisions to assist hotels and their employees during COVID-19. In agreement with the OST, the results have shown that greater employee job satisfaction and organizational commitment can be achieved by improving perception of organizational support. Adding to the OST, the current study has asserted that organizational support, in addition to ethical climate and codes of ethics, are critical to strengthening organizational commitment. Lastly, both organizational support and organizational justice have been found to play pivotal roles for organizational commitment, though these might produce other consequences that should be explored in future research.

5.2. Managerial implications

The study has many managerial implications. Even though the Egyptian government has set a great example in supporting hotel survival in the time of COVID-19 by taking a number of initiatives that include providing grants, subsidies, fiscal assistance, interest-free loans, flexibility of loan programs, health information, guidance on protection methods for hotels and their employees, funds for retaining staff, and suspending rental and utility payments for renters, it can support hotels through other practices such as funding for advertising and launching marketing campaigns on social media to promote the hospitality industry's reputation in markets. The implementation could be through publishing virtual tours inside hotels on social media platforms and official websites. Furthermore, this marketing support could be useful to achieve profitability after COVID-19 pandemic subsides and to compensate financial losses. During times of crisis, marketing innovation strategies and expenditures are vital to gain a competitive power (Wang, Hong, Li, & Gao, 2020). The Ministry of Health could provide hotels with highly trained doctors to handle COVID-19 cases among staff. The Ministry of Tourism, moreover, in collaboration with health authorities, needs to apply its managerial experience to train employees regularly about precautionary and preventive practices.

The findings suggest that government support can help hotels take care of their employees' health in the workplace through providing equipment to detect viruses and infectious diseases, personal protective equipment (masks, gloves), sterilizers, antiseptics, alcohol, and effective occupational safety and health measures, as well as information about health and wellness issues that affect hotel staff. Because of the importance of supporting employees’ health during COVID-19 crisis (Hu et al., 2020; Rosemberg, 2020), it is recommended that hotels install new technologies, such as electrostatic sprayers with disinfecting mist and ultraviolet light that allow for touchless disinfecting capabilities and electronic disinfection gates. In the interest of improving health and safety procedures, hotels could collaborate with international experts in food and water safety, hygiene, infection prevention, and hotel management, to protect both customers and employees.

Hotels can also safeguard the health and safety of their staff by following the recommendations and guidelines from the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health and the Centers for Disease Control (https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/topics/hierarchy/) which focuses on personal protective equipment, administrative controls, engineering controls, and elimination. Regarding personal protective equipment, it is recommended that organizations provide the necessary products such as disinfecting products, hand soap, hand sanitizer, facial tissues, and disposable nitrile or latex gloves in common areas (lobby, workers' breakroom, conference rooms, general bathrooms) and on cleaning carts. Regarding administrative controls, it is recommended to give employees the opportunity to stay home if sick, create awareness of the various measures to protect employees' health and safety, select designated locations for meeting (e.g. employee breakroom), develop a zero tolerance policy, provide more time for employees to disinfect cleaning materials, consider a scanning tool to prevent touching guests’ ID, disinfect key cards/keys before handing to guests and after they are returned, disinfect computer equipment between uses, disinfect surfaces and pens and other writing utensils that are frequently touched, use posters to share information on proper hand washing and coughing measures, and train employees about signs and symptoms of COVID-19, proper handling of linens and materials, disinfect hampers and carts, and wash hands are some of recommended measures (Rosemberg, 2020).

Although our results affirmed that government support is critical for hotels to retain staff by implementing such strategies as paid vacations, nonfrozen wages and salaries, and reducing benefits instead of layoffs, hotels need to organize sessions with employees to explain the destructive effect of COVID-19 on their financial budget and to reach solutions about how work can be organized while mitigating the bad impact on the two parties. Through electronic platforms, hotels could meet their employees to avoid restrictions of social distancing and some work can still be done, such as carrying out marketing plans and training schedules. Meanwhile, employees should be flexible in securing their rights related to salaries and benefits, and hotels could compensate them in future, post-pandemic days with additional rewards and promotion chances.

Research findings illustrate the importance of government support for hotels to train their employees during this pandemic via implementing cross-training, retraining them to fill new roles or cover more than one role, as well as providing them with training and education courses on prevention of infection. Even though health and safety training has profound significance in pandemic times for all employees (de Freitas & Stedefeldt, 2020), it is recommended that hotels provide guest-contact employees with advanced hygienic training. First, food handlers and supervisors should receive ongoing advanced training on offering food and beverage services safely. Second, housekeepers have to be trained on advanced cleanliness standards (Rosemberg, 2020) since they are in direct contact with guest rooms and public areas that may cause infection transmission. Training could be implemented via online learning platforms and webinars to avoid virus transmission and ensure the health and safety of hotel employees. After eliminating the pandemic, it is advisable that hotels inform their staff about hygiene safety practices regularly, so that they become embedded in everyday routines, by speaking about these practices during daily meetings, training sessions, and even during staff lunches (Hu et al., 2020).

Human capital is the cornerstone of the hospitality industry (Elkhwesky et al., 2019). The current study has demonstrated the importance of supporting health and hygiene in the workplace, employee retention, and employee training during health-related crises, in a fashion consistent with prior research (e.g., Henderson & Ng, 2004; Hu et al., 2020; Leung & Lam, 2004; Rosemberg, 2020; Tse et al., 2006; Vaccaro et al., 2020), and serves to provide hotels with the information they need to improve employee job satisfaction and organizational commitment. Our findings also affirm that, the more hotels support and value their employees, in terms of fairness, support for supervisors, and appropriate working conditions, the more staff satisfaction and commitment are achieved. Accordingly, the research highlights how hotels should strive for higher levels of organizational justice, which can be achieved with the provision of more training opportunities, the improvement of health care services, salary and wage support, service commissions, and retention strategies. For hotels looking for a more comprehensive approach, support can take other forms, including teamwork and team building initiatives, providing effective solutions to problems, conscious decision-making, leadership, creating new ways to perform tasks, and conflict resolution (Li, Bonn, & Ye, 2019; Salem, El-Said, & Nabil, 2013).

Although ethical climate has proven to be an important factor for hotel employees, as well as for positive organizational outcomes (Haldorai et al., 2020), it may have a harmful impact on employee job satisfaction and organizational commitment. Therefore, hotels should communicate openly and transparently about their intentions and planned actions in response to crises (Hu et al., 2020). Hotels should explain and justify their decisions to implement codes of ethics and ethics-related decisions in times of health crises. In addition, hotels should provide employees with opportunities to express their views (Haldorai et al., 2020) and ask questions (Li et al., 2019) regarding the implementation of codes of ethics, and should develop training related to ethics and employee's moral obligation (Chen, Chau, & Li, 2019) to enhance employee job satisfaction (Valentine & Fleischman, 2008). Hotels could organize sessions to discuss ethical practice with employees to encourage them to adopt the codes of ethics and to enhance satisfaction and commitment. It is also recommended that hotels respect the personal values and principles of their staff when setting codes of ethics. Laws, rules, ethics codes, and ethical norms, in addition to the employees' moral beliefs and personal values, should be a part of the organizational culture (Chen et al., 2019; Valentine & Fleischman, 2008).

5.3. Limitations and future lines of research

Some limitations of the current study must be addressed. Given that this study was conducted in the Egyptian hospitality industry and using a non-probability sampling approach, generalizability cannot be ascertained. Hence, we call further studies to test our model and validate our propositions in different contexts in the MENA region and globally. Another limitation of this study is that we focused on the moderating role of perceived overall organizational justice and ethical climate. With this in mind, we strongly suggest that further research could be extended to use hotels' support as a mediator variable between government support and job satisfaction. The key antecedents of government support need an in-depth investigation. Ethical climate could be studied as a moderator of the association between hotels' support and job satisfaction and job satisfaction and organizational commitment in different contexts; we found no significant influence on the association between hotels’ support and job satisfaction and a significant negative impact on the association between job satisfaction and organizational commitment in the Egyptian hotel context, but such effects might be found elsewhere. The present study sample might be seen as biased because it was limited to hotel staff in Egypt. Future investigations could examine the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the Egyptian tourism sector in general.

Though the current model has proven successful in explaining the situation during the time of COVID-19, future researchers should adopt the current model to be tested in post-pandemic times to improve insights and add to the data. In regard to the subject of employee retention, future research could also concentrate on the influence that the COVID-19 pandemic has on employee intention to remain in the hotel industry and investigate how the crisis may have influenced them to transition to other industries. To enhance the findings of the current study, future studies might focus on additional forms of support, such as moral and psychological support, that hotels could offer their employees. As the authors have argued that such factors may moderate and mediate the association between hotels' employee support and employee job satisfaction, it is important that further studies investigate such influences. Future studies could explore the subject from a different perspective and focus their attention on the extent that governments support hotels (Hang et al., 2020) and the resultant impact on hotels’ support for customers and society.

The authors of the current study call for future studies to use mixed-method designs to perform content analyses of newspapers and hotel websites to explore hotel practices during pandemics, utilizing the huge amount of secondary data (Jiang & Wen, 2020) available for the COVID-19 pandemic. For this study, we took a quantitative approach to evaluate the effect of government support on hotels’ employee support, employee job satisfaction and organizational commitment, through the interaction role of perceived overall organizational justice and ethical climate in the context of Egyptian hotels. Thus, we call further research to test moderated mediation effects. In addition, future qualitative studies could explore the impact of cultural factors specific to Egyptian employees' job satisfaction in the tourism sector. In the current study, we examined the role of governmental support on hotels (health support, staff retention, staff training), thus, we call future research to address the importance of investigating government support at the organizational level, and not just the personnel level. This can be conducted by employing hierarchical linear modeling (HLM). The current study focused on overall organizational justice. Thus, we suggest future research considering the distinction between distributive, procedural and interactional justice. Finally, it is recommended for further research to consider the variance among different hotel departments such as the front and back of the house in terms of the negative effects of such pandemic.

Declaration of competing interest

None.

Acknowledgement

We would like to thank the human resource directors in hotels for circulating our questionnaire. We are also grateful to our respondent hotels' employees' for participating in the study.

Biographies

Islam Elbayoumi Salem is an associate professor at the Faculty of Tourism and Hotels, Alexandria University, Egypt and at the Business Administration Department, Salalah College of Applied Sciences, University of Technology and Applied Sciences, Oman. His research interests are hospitality leadership, hospitality marketing, hospitality technology, hotels' outsourcing, and structural equation modelling (SEM) CB-SEM and PLS-SEM analysis in tourism and fuzzy-set configuration approach.