Abstract

Recent efforts in biomaterial-assisted brain tissue engineering suggest that match of mechanical properties of biomaterials to those of native brain tissue may be crucial for brain regeneration. In particular, the mechanical properties of native brain tissue vary as a function of age. To date, detailed characterization of age-dependent viscoelastic properties of brain tissue throughout the postnatal development to adulthood is only available at sparse age points in animal studies. To fill this gap, we have characterized the linear viscoelastic properties of the cerebral cortex in rats at well-spaced ages from postnatal day 4 to 4 months old, the age range that is widely used in neural regeneration studies. Using an oscillatory rheometer, the viscoelastic properties of rat cortical slices were measured independently by storage moduli (G′) and loss moduli (G″). The data demonstrated increases in both the storage moduli and the loss moduli of cortex tissue over post-natal age in rats. At all ages, the damping factor (G″/G′ ratio) remained constant at low oscillatory strain frequencies (<10 rad/s) before it started to decline at medium frequency range (10–100 rad/s). Such changes were not age-dependent. The stress-relaxation response increased over post-natal age, consistent with the increasing tissue stiffness. Taken together, our study demonstrates that age is a crucial factor determining the mechanical properties of the cerebral cortex in rats during early postnatal development. This data may provide the guidelines for age-specific biomechanics study of brain tissue and help to define the mechanical properties of biomaterials for biomaterial-assisted brain tissue regeneration studies.

Statement of significance:

Studies about age-dependent viscoelastic properties of rat brain tissue throughout the postnatal development to adulthood is sparsely available. To fill up the gap of knowledge, in this study, we have characterized the age-dependent viscoelastic properties and the linear viscoelastic properties of the cerebral cortex throughout the postnatal development stage to adulthood in rats by measuring storage moduli (G′), loss moduli (G″), damping factor (G″/G′ ratio) and stress-relaxation response. We have found that age is a crucial factor determining the mechanical properties of the cerebral cortex in rats during early postnatal development. The findings of this study could provide guidelines for age-specific biomechanical study of brain tissue and help to define the mechanical properties of biomaterials for biomaterial-assisted brain tissue regeneration in experimental models in rats.

Keywords: Viscoelastic properties, Rheometry, Age-dependence, Cerebral cortex

Introduction

Rat is one of the most popular animal species used for neural tissue regeneration studies. The mechanical properties of rat brain tissue vary in an age-dependent manner [1], which have been extensively implicated in brain biomechanics studies and tissue regeneration efforts [1–6]. Numerous studies reporting bioengineering assisted brain repair have suggested the need to customize material properties in order to facilitate tissue regeneration at different age [7, 8]. In addition, the load-bearing mechanisms of brain tissue differ in an age-dependent manner. For example, in the pig where the age-dependent mechanical properties of brain tissue were first studied, at low shear strains, the immature brain was more compliant than the adult brain [9], whereas at larger shear strains that were more relevant to human clinical head injury, the brain of immature porcine was about twice as stiff as the adult porcine brain [10]. Using scaled brain injury parameters in the pig considering the brain size, tissue strain, as well as the changes of material properties in the brain tissue as a function of postnatal development, the immature porcine brain appeared to be more resistant to injury impact relative to the adult porcine brain following a contusive brain injury [11, 12]. In the mouse, brain region and age related difference in viscoelasticity was reported when comparing juvenile and adult mice brain with the adult brain stiffer at varying degree [13]. The mechanical properties of brain tissue dictate how a force (from an impact, rapid deceleration, and other insults) is propagated through the brain and the resultant damages [14]. Characterization of the age-dependent mechanical properties of brain cortex would help us to understand the age-dependent brain tissue response to the mechanical forces involved in different experimental brain injury models, as well as formulation of biomimetic materials matching the native brain tissue for regeneration and repair strategies.

Brain tissue exhibits a complex mechanical behaviors that are featured by nonlinear viscoelastic behavior, poroelastic deformation and failure. In a pioneering publication of Hakim [15], the brain was described as a “porous, sponge-like viscoelastic material”. Subsequent finding, i.e., deformation of porous matrix due to fluid flow from the pores and its drainage from the interstitial space as the leading mechanism in brain tissue deformation under quasi-static small-loading condition [16], mandates the addition of a viscous term into the rheological model of brain. Viscoelastic mechanical properties are characterized by time-dependent strain in response to constant stress [17,18], In the past, a combination of spring and dashpot, which represent the elastic and viscous components in viscoelastic materials, respectively, has been used in models to describe the viscoelastic behaviors [19]. Depending upon the percentages of elastic vs. viscous components and their arrangements in a viscoelastic material, the material may exhibit viscoelastic behaviors ranging from ideally viscous, viscoelastic liquid, sol/gel transition, viscoelastic solid/gel-like, to ideally elastic [20,21]. In the literature, measurement of viscoelastic properties of rat brain tissue has primarily focused on region-specific differences on deformation susceptibility to brain injury in adult rats [4,5]. To date, the age-dependent viscoelastic properties of rat brain tissue have only been examined at sparse age points (e.g., postnatal day 13 (P13), P17, P43, and P90 in rats) [1,4]. Reported elastic and viscoelastic properties of brain tissue vary by orders of magnitude [2,22], possibly due to the susceptibility of such measurements to the experimental loading conditions, testing methods, and the tissue processing protocols before testing. The majority of these studies have used microindentation to measure the viscoelastic properties of the rat brain [2,22]. Microindentation offers controlled impactor size and applied force, which allows probing of the anatomical area of interest at high spatial resolution and provides relatively constant contact area that simplifies mechanical property derivation from the measured resultant loads [4,5]. However, it does not distinguish between the storage vs. loss moduli, and therefore, the contribution of elastic vs. viscous components in the viscoelastic materials to the mechanical properties [4,5]. In addition, microindentation is not suited to measure the dynamic viscoelastic properties in response to cyclic shear stress as a function of oscillatory strain frequency [4]. Alternatively, oscillatory rheometry measures the dynamic viscoelastic properties by separating the elastic moduli and viscous property when subjecting the material to oscillatory shear stresses of controlled rate and amplitude [23,24].

The present study aims at characterizing the age-dependent linear viscoelastic properties of native rat brain during development from neonatal (P4, and P9 rats) stage to adulthood (P47, P60, and 4 months old), at the ages that are most widely used in experimental studies, using oscillatory rheometry. Based on previously established neurological age equivalence of rat to human, P7–10 old rat is equivalent to a human at birth, and P12–15 old rat is equivalent to a 2–3-year-old human [25,26]. The neurological development in the rat is completed by P20 [27], but the musculoskeletal/skull development of the rat continues beyond P43 [28]. While P22–30 old rat is considered to be equivalent to a human teenager, the P47–4 months old rat is equivalent to the human adult age [29].

Materials and methods

Animals

All animal procedures were approved by the Virginia Common-wealth University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC). Pregnant dam of Fisher 344 rats were purchased from the vendor (Envigo, NJ). Animals were housed in the animal facility, with a 12-hour light/dark cycle, water and food provided ad libitum. Pups of mixed sex at the age of P4, P9, P12, P17 and P22 were used, whereas at P29, P47, P60, and 4 months male rats were used. The reason that we only measured male animals at the age above P22 is because in clinic, young males have much higher incidence suffering from brain trauma, and male rats are more widely used in neurological injury research field [30]. Four animals were included for each age group, a total of 36 rats were used.

Cortical tissue dissection

All animals were euthanized with sodium pentobarbital (P4–17: 50 mg/kg, P22–29: 100 mg/kg, P47–4 months old: 150 mg/kg, intraperitoneal). In order to minimize the effect of anesthetic agent on the mechanical properties of tissue, sodium pentobarbital was used with different dosages for animals of different age by following the dose recommendations in the literature for rats [31]. Sodium pentobarbital is the most popular anesthetic agent for euthanasia of rodents by exsanguination and is known for its minimum adverse effects on biochemical, molecular and histological measurements on rodents when dosed properly [32]. Death was verified by cessation of heartbeat. Immediately after euthanization, the scalp was reflected along a midline incision to expose the skull. The whole brain was carefully dissected and meninges and connective tissue were removed under microscope. Using a razor blade, the brain was sliced horizontally into 1 mm thick slices for the test. Tissue slices were maintained moist throughout the course of measurements by intermittently spraying normal saline on the brain surface.

Viscoelastic property measurement

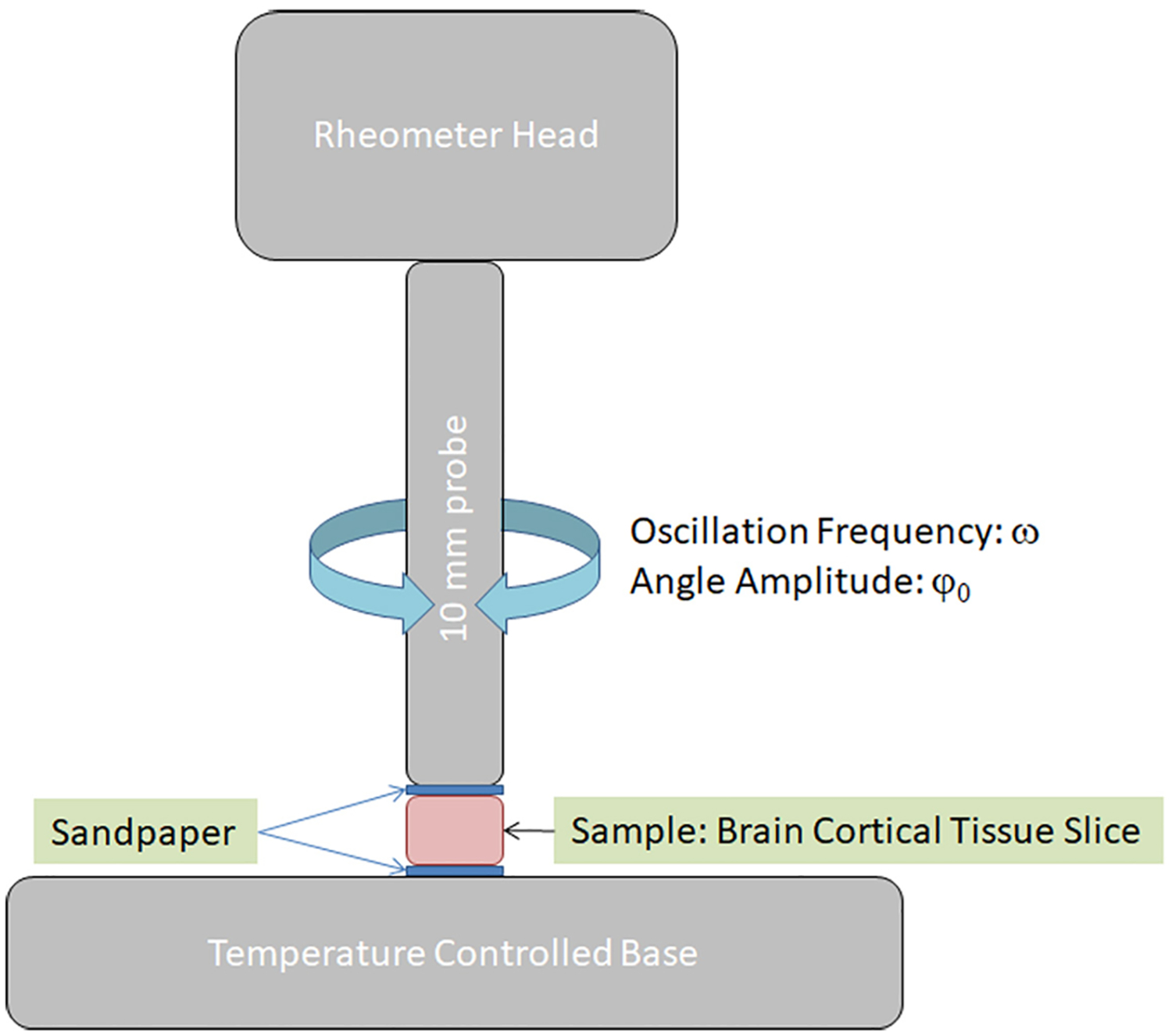

A parallel plate rheometer with a 10 mm diameter probe was used to measure the storage modulus G′ and loss modulus G″ at 25°C. The experimental set up was depicted in Figure 1. As shown in figure 1, a layer of sandpaper was adhered to both plates (320 grit, McMaster Carr) to prevent slip between the tissue and the plates. The sandpaper only touched the side of a tissue slice that was not measured, therefore, damage of the sides of tissue slices by the sandpaper that may affect the measurements was not expected. To provide consistent measurements, the normal force on the tissue was maintained at 0.01 N after the tissue was allowed to relax for approximately 5 minutes. All measurements were conducted within 4 hours after the animal was sacrificed. Only one test was performed on each sample to avoid the effect of multiple tests on altering the material properties.

Fig. 1.

Experimental setup scheme for the measurement of viscoelastic mechanical property of rat brain cortical tissue slices using an oscillatory rheometer.

Amplitude sweep

Using an oscillatory rheometer, we performed amplitude sweep and frequency sweep of the brain cortex from rats at advancing postnatal ages up to 4 months old. The brain cortical slice was placed between two rheometer plates and sandpaper was attached to both plates to prevent slip. The top plate oscillated at a frequency and an angle amplitude, resulting in a shear strain on the sample. Specifically, the sample responded to the applied deflection (characterized by the angle amplitude φ0 at a frequency ω) with a reactional torque (characterized by a torque signal T0 and a phase lag ϕ between the angular displacement and the torque). The storage modulus G′ and loss modulus G″ were measured from the phase lag ϕ, the amplitude of the deflection φ0, and the reactional torque T0. We performed an amplitude sweep from 0.01% to 100% shear strain at 1 rad/s to establish the linear viscoelastic strain range of the brain tissue. i.e., the range of shear strain at which G′ and G″ remain constant at a constant frequency of interest (e.g., 1 rad/sec).

Frequency sweep

Frequency sweep of the tissue was performed from 0.1 to 120 rad/s at 1% shear strain to evaluate the time-dependent viscoelastic properties of the brain cortex within the linear viscoelastic range at 1% shear strain, and at oscillatory strain frequencies ranging from 0.1–160 rad/sec. The oscillation frequency was increased step-wise between adjacent measuring points at a constant oscillation amplitude. High oscillatory frequencies simulate fast motion on short timescales, while low frequencies simulate slow motion on long timescales (i.e., at rest).

Stress relaxation

Stress relaxation measures the required stress to sustain a constant fixed step strain in the brain cortex [33]. Under some conditions of brain trauma, e.g., blast wave, the brain tissue is subjected to repetitive strains [34,35]. Stress relaxation helps to evaluate the ability of the brain tissue to dissipate stress with time scale [36]. Stress relaxation was performed for a duration of 10 seconds of loading and with a constant step strain of 1%.

Statistical analysis

Averaged storage and loss moduli of brain were quantified for each age group as mean ± standard error of mean (SEM) from 4 animals. The SEM values are provided in the supplementary materials. Since rheometry was performed on each slice, each slice was considered an independent measurement for statistical purpose. The sharp razor blade used to slice the brain tissue allowed a quick and clean separation of adjacent slices to minimize the effect of a slice on the adjacent slices. Therefore, slices were independent holds. The storage and loss moduli calculated for brain of different animal ages were evaluated using a 3-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). For all tests, a p-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

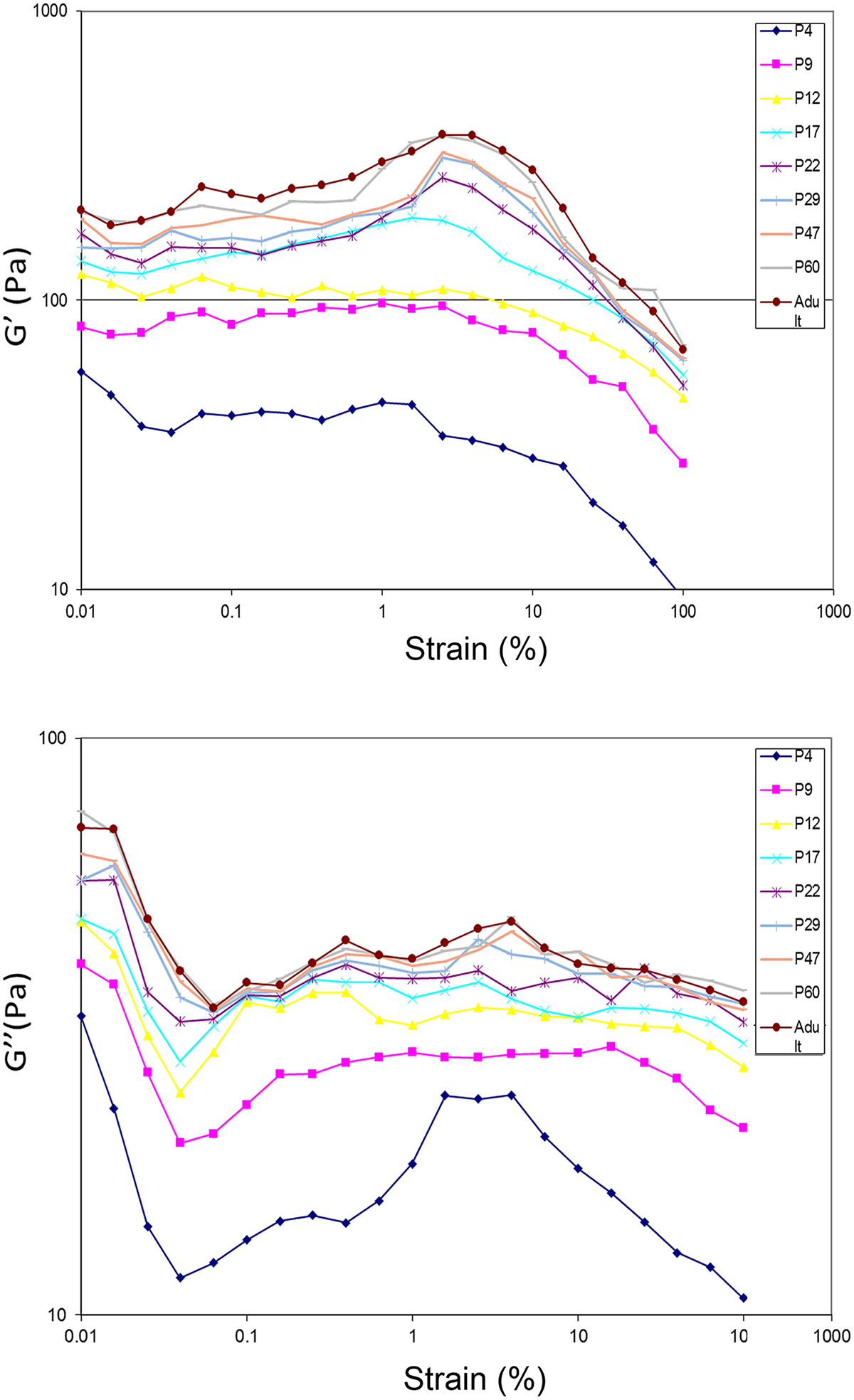

Amplitude sweep

The amplitude sweep revealed the linear viscoelastic strain range of the brain tissue at all postnatal ages of examination was 0.1%−5% (Fig. 2), beyond which the storage modulus G′ declined, indicative of reducing elasticity, disruption of solid structure, and becoming more fluid-like. Within the linear viscoelastic strain range, the brain tissue maintained a gel-like structure (G′ > G″). For the amplitude sweep, the age-dependence of shear moduli reduced beyond the age of P22, suggesting P22 as the starting age for the mechanical maturation of rat brain cortex.

Fig. 2.

Amplitude sweep measurement at a shear strain range of 0.01%−100%. (A) storage modulus; (B) loss modulus.

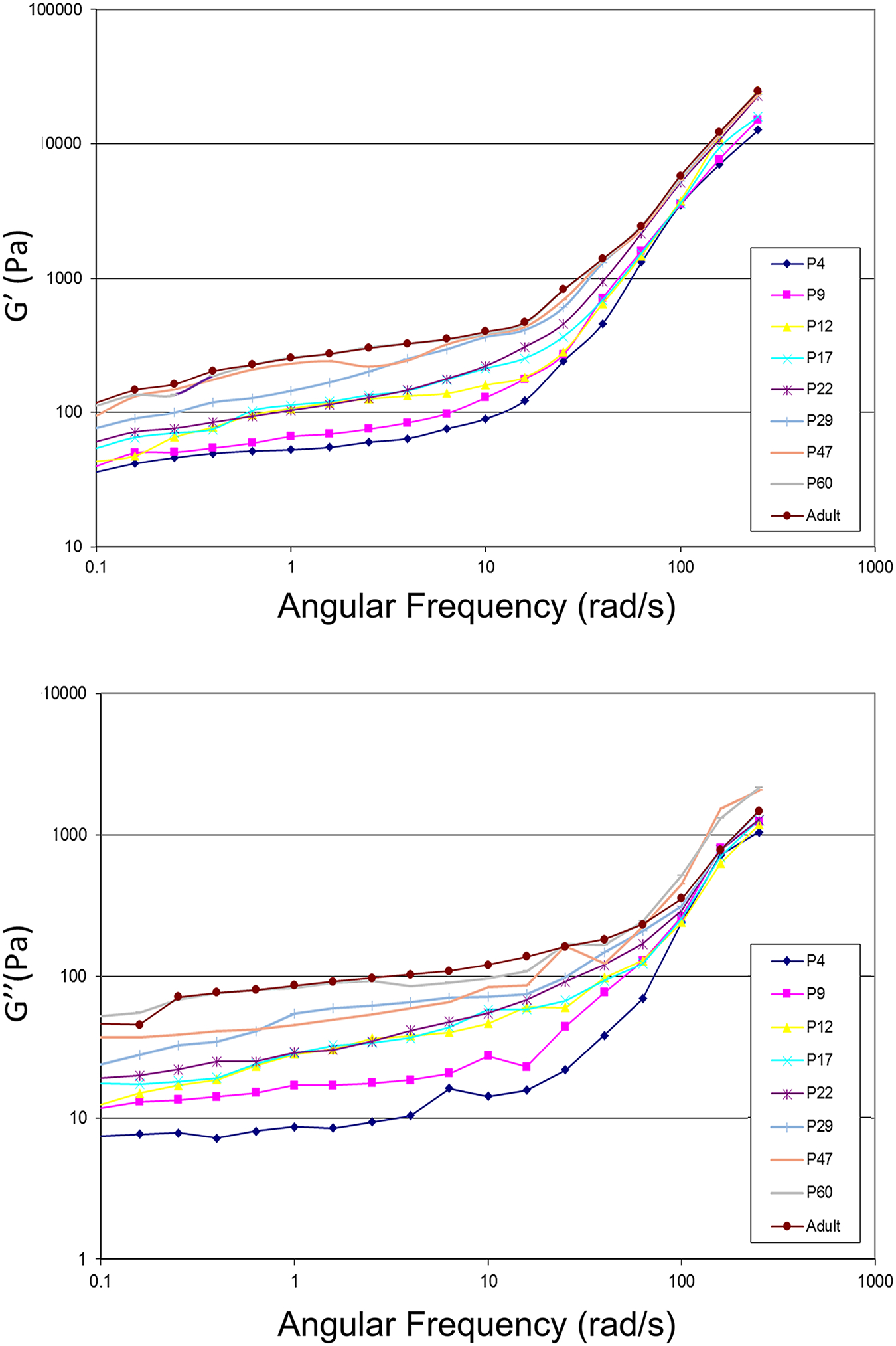

Frequency sweep

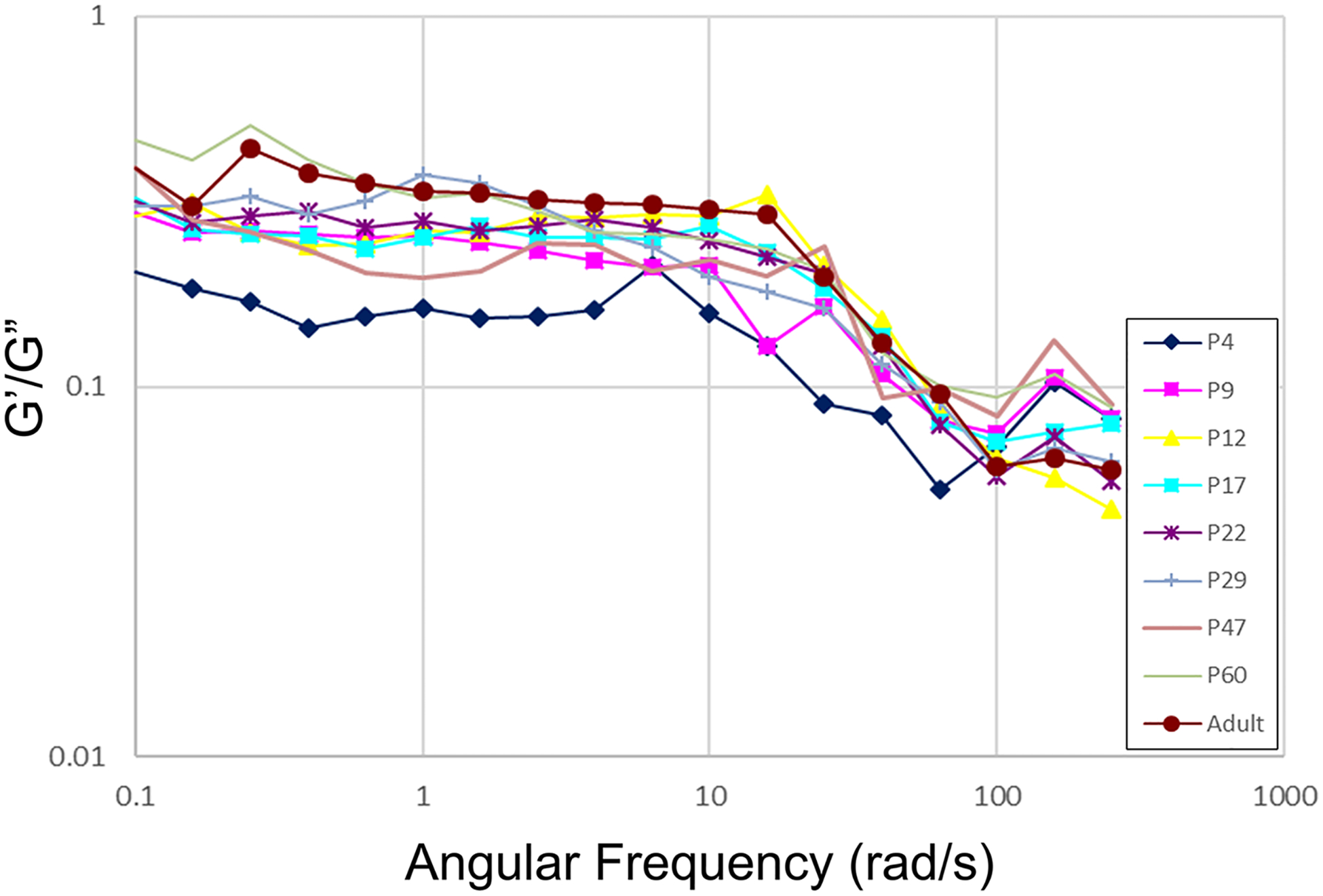

Both G′ and G″ of the brain cortex increased over the age of animal and oscillatory strain frequency (Fig. 3). In particular, G′ was nearly an order of magnitude greater than G″ at low frequencies, i.e., G′ was on the order of hundreds of Pa, while G″ was on the order of tens of Pa. Our data were consistent with previous studies [2] of the shear rheology of native brain tissue across species including rat, rabbit, porcine, bovine, and human on the range of storage modulus (G’ on the order of 102-103 Pa) and loss modulus (G” on the order of 10–102 Pa). Regardless of the age of animal, the G″/G′ ratio (loss factor or damping factor or loss tangent: the ratio between the viscous and the elastic portion of the viscoelastic behavior) remained constant at low oscillatory angular frequencies (<10 rad/s) before it declined at medium frequency range (10–100 rad/s) (Fig. 4), suggesting that G′ and G″ increased synchronically at low frequencies but G′ increased more rapidly than G″ at medium frequencies. No age-dependence was found for the damping factor of the brain cortex over frequency. In these measurements, the physical limitations of the rheometer did not allow us to measure material properties at higher frequencies. For viewing convenience, only the average of each measurement of modulus was plotted in the Figs. 2 and 3 without adding the SEM for each data point. For each measurement, the SEM was small (please refer to the supplement data files for the original datasets with calculated SEM for each measurement and for each age group), indicating the consistency among the samples due to the standard tissue preparation of brain slices.

Fig. 3.

Frequency sweep measurement at oscillatory strain frequencies ranging from 0.1–160 rad/sec with a shear strain at 1%. (A) storage modulus; (B) loss modulus.

Fig. 4.

The loss/damping factor (G″/G′ ratio) at oscillatory strain frequencies ranging from 0.1–160 rad/sec with a shear strain of 1%.

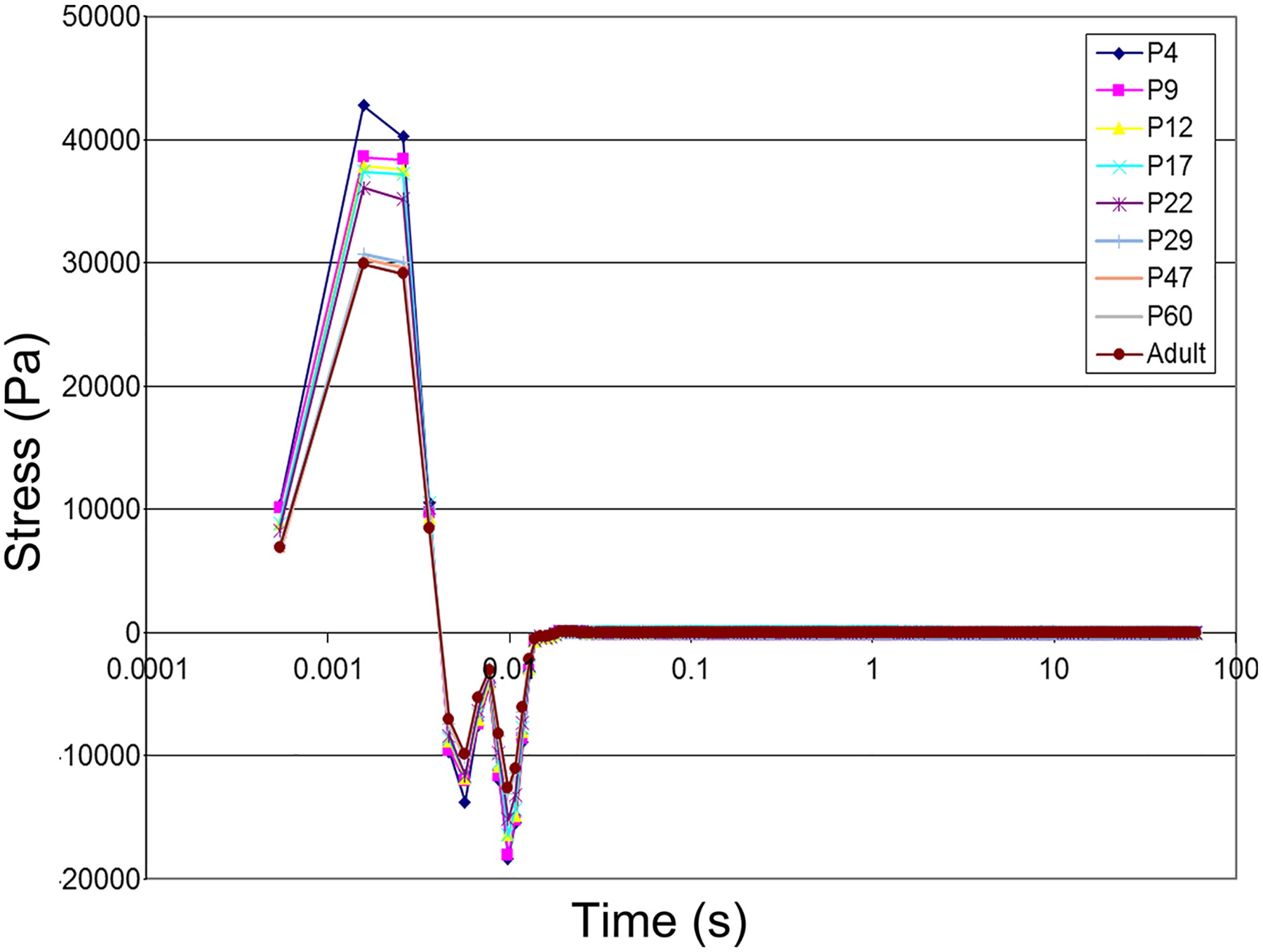

Stress relaxation

For a duration of 10s and when loaded at a constant step strain of 1% which fell within the linear viscoelastic strain range identified in the amplitude sweep, the stress relaxation of brain cortex tissue increased over animal’s age (Fig. 5), suggesting the increase in the ability of brain cortex tissue over age to dissipate energy associated with the applied stress. The younger the animals were, the more compliant the brain cortex tissue was. In addition, significant increase in stress relaxation was found between the age of P22 and P29, beyond which stress relaxation became stabilized over age. This was consistent with the findings from the amplitude sweep possibly due to the onset of tissue maturation within that age range (P22-P29). The small magnitude of step strain (1%) that was applied in the study to ensure validity of the linear viscoelastic strain range might have skewed the age-dependence of stress-relaxation behavior of the brain cortex tissue beyond P29. It is noteworthy that there were negative values on the stress-relaxation graph across the tested age range perhaps due to the mechanical oscillations that might be reduced through analog and digital filtering during test setup [4].

Fig. 5.

Stress relaxation of freshly dissected brain cortex tissue from rats of different ages for a duration of 10s of loading with a constant step strain of 1%.

Discussion

In the present study, we have characterized the linear viscoelastic properties of rat brain cortex at well-spaced postnatal ages using oscillatory rheometry. The elastic and viscous properties of rat cortical brain slices were measured independently by storage moduli and loss moduli. The amplitude sweep and frequency sweep demonstrated an increase in both the storage moduli and the loss moduli of rat cortex tissue over post-natal age of the animal. Regardless of the age, increasing oscillatory strain beyond 5% led to declination of the storage moduli, suggesting the onset of viscous flow-based deformation at this strain. At all ages, the damping factor (G″/G′ ratio) remained constant at low oscillatory strain frequencies (<10 rad/s) before it started to decline at medium frequency range (10–100 rad/s). Such changes were not age-dependent. The stress-relaxation was increased over post-natal age, which was consistent with the increasing storage modulus of the tissue over age on the frequency sweep. Taken together, these data have demonstrated that the age is a factor determining the mechanical properties of cerebral cortex in rats.

For a viscoelastic material such as the brain tissue, a couple of loading parameters determine the dominant mechanical properties [37, 38]. For example, at low strain rate/frequency (the speed of deformation), viscous properties dominate, while at high strain frequency, there is not enough time for the material to deform and dissipate energy, therefore elastic properties dominate [37,38]. Since G′ describes resistance to elastic deformation, and G″ describes resistance to viscous flow-based deformation enabled by internal viscous friction in the material [37,38]. Our data in Fig. 3 indicated that elastic deformation and viscous flow contributed equally to the deformation behavior of brain cortex at low oscillatory strain frequencies (constant damping factor), while elastic deformation overtook viscous flow deformation and dominated at sufficiently high oscillatory frequencies (declining damping factor) when rat cortex tissue became more structured or solid-like. Such changes of the damping factor over strain frequency were not age-dependent, possibly due to the increase in both elasticity and viscous friction of brain cortex over age, and/or the measurements fell within the linear viscoelastic range [4].

The structural origin of age-dependent mechanical properties of brain tissue may be attributed to the postnatal development of brain parenchyma with changes in tissue composition such as the increase in white matter vs. gray matter content since the white matter is generally stiffer than the gray matter [1,36,39], and region-specific tissue development due to local variations of white matter stiffness [10,13,39]. At the tissue level, the gray matter is mostly composed of cell bodies, dendrites, and unmyelinated axons, thus tends to be isotropic and soft relative to the white matter which is composed of myelinated axonal bundles/myelin and cell processes that are anisotropic due to the directionality of the axonal connections [22,40]. In general, the white matter is stiffer, more viscous, and responds less rapidly to mechanical loading than the gray matter [10,36,39]. There are region-specific variations in the brain in terms of the contents of white and gray matters and fluid-filled ventricles, and the geometry of brain cortex is further complicated by cortical folding [6]. At the molecular level, the ECM produced by the cells is the major structural and mechanical component of the brain tissue [22]. ECM is a crosslinked polymeric network composed of proteins, sugars, and other polymers. The brain tissue contains about 20% extracellular space and exhibits poroelasticity [16]. Both cells and the ECM are viscoelastic, and the viscoelasticity of both contribute to brain mechanics [22,41–44]. Studies have demonstrated that cells in the brain such as neurons [41,42,44], glia cells [42], and microglia [43] are all viscoelastic. Due to the variations in the cyto-skeleton composition, different types of cells have different viscoelasticity [42], and different parts of the same cell differ in viscoelasticity (e. g., soma vs. cell processes) possibly due to the uneven local distribution of cell organelles [22,42]. In particular, both glial cells and neurons are very soft (“rubber elastic”), but their elastic behavior dominates over the viscous behavior [22,42].

Brain ECM is composed of glysaminoglycans (GAGs), i.e., large complexes of negatively charged hetero-polysaccharide chains in the form of a hydrated gel through the binding of negatively charged groups on the GAGs to positively charged hydrogen ions of water [45]. A volume of studies have indicated that GAGs and proteoglycans are viscoelastic [46–48] and play roles on stress relaxation of the brain tissue [47]. Due to the negative charges in GAGs, chains tend to be extended in solution, repel one another, and slip past one another when brought together, which confers high viscosity and low compressibility [45]. Such “slippery” consistency of GAGs makes brain ECM deform through a viscous flow mechanism [45]. When the brain is compressed, water is squeezed out of GAGs to reduce the volume of GAGs [45]. When the compression is removed, GAGs recover to their original, hydrated volume due to the repulsion of their negative charges [45]. As demonstrated in the frequency sweep and stress relaxation, rat brain cortex exhibits a viscoelastic behavior typical of partially crosslinked 3D-network structure, i.e., soft gel or dispersion with weak structure, strength of structure at rest (onset of frequency sweep), and without long-term relaxation. Our observed increase in both the storage moduli and the loss moduli of rat cortex tissue over postnatal age suggest the development and maturation of both cells and their produced ECM over age. The age-dependence of mechanical properties declined beyond P22, suggesting mechanical maturation of rat brain cortex at this age. Regarding the neurological age-correlation between human and rats, P7–10 in the rat is equivalent to human at birth, P12–15 is equivalent to human 2–3 years of age, and P20 in the rat marks the completion of neurological development, i.e, equivalent to human young adults [26].

Our work provides the full spectrum of G′ and G″ read-outs within a wide oscillatory strain frequency range across the full range of postnatal age up to 4-month old in rats. The age-dependent changes of brain mechanical properties affect the response of a developing brain to rapid rotational accelerations encountered during neurological injury [49, 50]. Measurements of age-dependent viscoelastic mechanical properties of rat brain may provide the guideline for the development of age-specific experimental models and computational head injury simulations. For example, at a particular postnatal age, forces may be determined to induce comparable mechanical stresses, strains, and injury parameters in pediatric and adult brains [50]. Depending upon the magnitude of the load, critical stress, strain, or strain rate thresholds may be used as failure parameters. To date, two mechanical models commonly applied to brain viscoelasticity are: Maxwell model, and Kelvin-Voight model [19]. In the Maxwell model, springs and dashpots, which are used to simulate the elastic component and viscous component in a viscoelastic material, respectively, are arranged in linear series, while in the Kelvin-Voight model, they are arranged in parallel. The general Maxwell model is often the best to describe biological systems [51].

In our study design, a few limitations are present. One limitation is the applied small shear strain which does not elicit a robust response of tissue especially at younger animals. The low shear strain of 1% was chosen to ensure that the data could be fit into linear viscoelastic range. The brain cortex tissue at young ages is too compliant to display notable stress relaxation at low magnitude of strain (1%). As indicated in the amplitude sweep, non-linear viscoelastic behavior was only evident for strains greater than 5%, consistent with the reports in the literature [3, 52]. Although beyond the scope of this study, analysis of the stress relaxation behavior relative to time-dependent change in shear modulus would help when modeling the viscoelastic behavior of brain cortex tissue at different ages. Measurement of the time-dependent shear modulus was only performed at low shear strain of 1% and for times greater than 100 miliseconds (ms), which is considered a short-term rather than an instantaneous modulus. These parameters may not be relevant to high-rate mechanical response of brain cortex during a sudden impact in neurotrauma in which the primary strain may go up to 100% and falls into the nonlinear range [53]. In addition, the measurement results may not be applied to model the mechanical response of rat brain cortex to neurological insults in longer time frames (> 10s) such as neurosurgery or tumor growth. Another imitation of this study is that sex related difference is not compared. In this study we examined pups younger than 22 days in mixed sex, whereas at the age above 22 days only male rats were examined as young males are the dominant population suffering from TBI [54,55]. As reported there is a gender related difference in brain viscoelasticity [56], future study should consider including both males and females to fully address biomechanical changes in the brain.

Ongoing work in the lab is focused on assessing the effect of impact indentation on brain tissue in rats. Impact indentation is a technique that may be used to evaluate the impact response of viscoelastic materials such as compliant tissues [26], therefore, may be relevant to brain tissue response to focal brain injury (e.g., controlled cortical impact injury). Characterization of brain tissue response to impact indentation with different parameters provides a guideline for studies that are aiming at developing brain tissue simulant biomaterials for tissue regeneration, or for biomechanical modeling to predict impact response based upon the material’s rheological properties, and vice versa. In conjunction with shear rheology, impact indentation may reveal the fingerprint mechanical properties of brain tissue, to which brain tissue simulant biomaterials seek to match. Using impact indentation, we are also measuring the non-linear behavior for brain tissue up to 100% strain in some regions to match the maximum strain during brain injury.

Conclusion

In this study, we have characterized the linear viscoelastic properties of rat cerebral cortex at well-spaced ages from the postnatal stage to adulthood, i.e., from postnatal day 4 to 4 months old. An oscillatory rheometer has allowed us to measure storage moduli (G′) vs. loss moduli (G″) separately to distinguish the contribution of elastic vs. viscous components in the brain cortex tissue to its viscoelastic mechanical properties. The data demonstrated an increase in both the storage moduli and the loss moduli of cortex tissue over postnatal age up to P22, beyond which both moduli plateaued perhaps due to the onset of mechanical maturation of rat brain cortex at P22. At all ages and a shear strain of 1%, the damping factor (G″/G′ ratio) remained constant at low oscillatory strain frequencies (<10 rad/s) before starting to decline at medium frequency range (10–100 rad/s). Such changes were not age-dependent. The stress-relaxation response increased over postnatal age, consistent with the increasing stiffness of the tissue. Taken together, age is a significant factor to determine the viscoelastic properties of rat brain cortex during early postnatal development prior to mechanical maturation of the tissue (i.e. up to P22). Future work will focus on assessing the response of rat brain cortex at different postnatal age to the mechanical impact during TBI using an impact indentation technique.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This study is supported by NIH grant NS093985 (Sun, Zhang, Wen), NS101955 (Sun).

Footnotes

Ethical Statement

No human subject is involved in this study. All animal procedures were approved by the Virginia Commonwealth University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC).

Declaration of Competing Interest

Author Disclosure Statement: No competing financial interests exist.

Supplementary materials

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.brain.2022.100056.

Data Availability

Data will be made available on request.

References

- [1].Gefen A, Gefen N, Zhu Q, Raghupathi R, Margulies SS, Age-dependent changes in material properties of the brain and braincase of the rat, J Neurotrauma 20 (11) (2003) 1163–1177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Chatelin S, Constantinesco A, Willinger R, Fifty years of brain tissue mechanical testing: from in vitro to in vivo investigations, Biorheology 47 (5–6) (2010) 255–276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Elkin BS, Ilankovan A, Morrison B 3rd, Age-dependent regional mechanical properties of the rat hippocampus and cortex, J Biomech Eng 132 (1) (2010), 011010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Elkin BS, Ilankovan AI, Morrison B 3rd, A detailed viscoelastic characterization of the P17 and adult rat brain, J Neurotrauma 28 (11) (2011) 2235–2244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Lee SJ, King MA, Sun J, Xie HK, Subhash G, Sarntinoranont M, Measurement of viscoelastic properties in multiple anatomical regions of acute rat brain tissue slices, J Mech Behav Biomed Mater 29 (2014) 213–224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Prevost TP, Balakrishnan A, Suresh S, Socrate S, Biomechanics of brain tissue, Acta Biomater 7 (1) (2011) 83–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Chan BP, Leong KW, Scaffolding in tissue engineering: general approaches and tissue-specific considerations, Eur Spine J 17 (Suppl 4) (2008) 467–479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Kular JK, Basu S, Sharma RI, The extracellular matrix: Structure, composition, age-related differences, tools for analysis and applications for tissue engineering, J Tissue Eng 5 (2014), 2041731414557112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Thibault KL, Margulies SS, Age-dependent material properties of the porcine cerebrum: effect on pediatric inertial head injury criteria, J Biomech 31 (12) (1998) 1119–1126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Prange MT, Margulies SS, Regional, directional, and age-dependent properties of the brain undergoing large deformation, J Biomech Eng 124 (2) (2002) 244–252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Duhaime AC, Margulies SS, Durham SR, O’Rourke MM, Golden JA, Marwaha S, Raghupathi R, Maturation-dependent response of the piglet brain to scaled cortical impact, J Neurosurg 93 (3) (2000) 455–462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Durham SR, Raghupathi R, Helfaer MA, Marwaha S, Duhaime AC, Age-related differences in acute physiologic response to focal traumatic brain injury in piglets, Pediatr Neurosurg 33 (2) (2000) 76–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Antonovaite N, Hulshof LA, Hol EM, Wadman WJ, Iannuzzi D, Viscoelastic mapping of mouse brain tissue: Relation to structure and age, J Mech Behav Biomed Mater 113 (2021), 104159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Meaney DF, Morrison B, Dale Bass C, The mechanics of traumatic brain injury: a review of what we know and what we need to know for reducing its societal burden, J Biomech Eng 136 (2) (2014), 021008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Hakim S, Venegas JG, Burton JD, The physics of the cranial cavity, hydrocephalus and normal pressure hydrocephalus: mechanical interpretation and mathematical model, Surg Neurol 5 (3) (1976) 187–210. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Franceschini G, Bigoni D, Regitnig P, Holzapfel GA, Brain tissue deforms similarly to filled elastomers and follows consolidation theory, J Mech Phys Solids 54 (12) (2006) 2592–2620. [Google Scholar]

- [17].Hirakawa K, Hashizume K, Hayashi T, [Viscoelastic property of human brain -for the analysis of impact injury (author’s transl)], No To Shinkei 33 (10) (1981) 1057–1065. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Hiscox LV, McGarry MDJ, Johnson CL, Evaluation of cerebral cortex viscoelastic property estimation with nonlinear inversion magnetic resonance elastography, Phys Med Biol 67 (9) (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Haslach HW Jr., Nonlinear viscoelastic, thermodynamically consistent, models for biological soft tissue, Biomech Model Mechanobiol 3 (3) (2005) 172–189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Dunn MG, Silver FH, Viscoelastic behavior of human connective tissues: relative contribution of viscous and elastic components, Connect Tissue Res 12 (1) (1983) 59–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Mutungi G, Ranatunga KW, The viscous, viscoelastic and elastic characteristics of resting fast and slow mammalian (rat) muscle fibres, J Physiol 496 (Pt 3) (1996) 827–836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Franze K, Janmey PA, Guck J, Mechanics in neuronal development and repair, Annu Rev Biomed Eng 15 (2013) 227–251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Nicolle S, Lounis M, Willinger R, Palierne JF, Shear linear behavior of brain tissue over a large frequency range, Biorheology 42 (3) (2005) 209–223. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Sato M, Schwartz WH, Selden SC, Pollard TD, Mechanical properties of brain tubulin and microtubules, J Cell Biol 106 (4) (1988) 1205–1211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Dobbing J, The Influence of Early Nutrition on the Development and Myelination of the Brain, Proc R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 159 (1964) 503–509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Porterfield SP, Hendrich CE, The role of thyroid hormones in prenatal and neonatal neurological development–current perspectives, Endocr Rev 14 (1) (1993) 94–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Bockhorst KH, Narayana PA, Liu R, Ahobila-Vijjula P, Ramu J, Kamel M, Wosik J, Bockhorst T, Hahn K, Hasan KM, Perez-Polo JR, Early postnatal development of rat brain: in vivo diffusion tensor imaging, J Neurosci Res 86 (7) (2008) 1520–1528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Watanabe T, Tamamura Y, Hoshino A, Makino Y, Kamioka H, Amagasa T, Yamaguchi A, Iimura T, Increasing participation of sclerostin in postnatal bone development, revealed by three-dimensional immunofluorescence morphometry, Bone 51 (3) (2012) 447–458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Vidair CA, Age dependence of organophosphate and carbamate neurotoxicity in the postnatal rat: extrapolation to the human, Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 196 (2) (2004) 287–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Gupte R, Brooks W, Vukas R, Pierce J, Harris J, Sex Differences in Traumatic Brain Injury: What We Know and What We Should Know, J Neurotrauma 36 (22) (2019) 3063–3091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Mohamed AS, Hosney M, Bassiony H, Hassanein SS, Soliman AM, Fahmy SR, Gaafar K, Sodium pentobarbital dosages for exsanguination affect biochemical, molecular and histological measurements in rats, Sci Rep 10 (1) (2020) 378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Tsubokura Y, Kobayashi T, Oshima Y, Hashizume N, Nakai M, Ajimi S, Imatanaka N, Effects of pentobarbital, isoflurane, or medetomidine-midazolam-butorphanol anesthesia on bronchoalveolar lavage fluid and blood chemistry in rats, J Toxicol Sci 41 (5) (2016) 595–604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Wang M, Wang C, Bulk Properties of Biomaterials and Testing Techniques, Encyclopedia of Biomedical Engineering (2019) 53–64. [Google Scholar]

- [34].Cernak I, Understanding blast-induced neurotrauma: how far have we come? Concussion 2 (3) (2017) CNC42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].McKee AC, Daneshvar DH, The neuropathology of traumatic brain injury, Handb Clin Neurol 127 (2015) 45–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Budday S, Ovaert TC, Holzapfel GA, Steinmann P, Kuhl E, Fifty Shades of Brain: A Review on the Mechanical Testing and Modeling of Brain Tissue, Archives of Computational Methods in Engineering 27 (2019) 1187–1230. [Google Scholar]

- [37].Lakes RS, Viscoelastic materials, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge; New York, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- [38].Perkins JN, Lach TM, Viscoelasticity: theories, types, and models, Materials science and technologies, Nova Science Publishers, Inc., New York, 2011, p. 1 online resource. [Google Scholar]

- [39].Johnson CL, McGarry MD, Gharibans AA, Weaver JB, Paulsen KD, Wang H, Olivero WC, Sutton BP, Georgiadis JG, Local mechanical properties of white matter structures in the human brain, Neuroimage 79 (2013) 145–152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Arbogast KB, Margulies SS, Material characterization of the brainstem from oscillatory shear tests, J Biomech 31 (9) (1998) 801–807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Efremov YM, Grebenik EA, Sharipov RR, Krasilnikova IA, Kotova SL, Akovantseva AA, Bakaeva ZV, Pinelis VG, Surin AM, Timashev PS, Viscoelasticity and Volume of Cortical Neurons under Glutamate Excitotoxicity and Osmotic Challenges, Biophys J 119 (9) (2020) 1712–1723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Lu YB, Franze K, Seifert G, Steinhauser C, Kirchhoff F, Wolburg H, Guck J, Janmey P, Wei EQ, Kas J, Reichenbach A, Viscoelastic properties of individual glial cells and neurons in the CNS, Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 103 (47) (2006) 17759–17764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].van Wageningen TA, Antonovaite N, Paardekam E, Breve JJP, Iannuzzi D, van Dam AM, Viscoelastic properties of white and gray matter-derived microglia differentiate upon treatment with lipopolysaccharide but not upon treatment with myelin, J Neuroinflammation 18 (1) (2021) 83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Wang L, Kuhl E, Viscoelasticity of the axon limits stretch-mediated growth, Computational Mechanics 65 (2020) 587–595. [Google Scholar]

- [45].Rowlands D, Sugahara K, Kwok JC, Glycosaminoglycans and glycomimetics in the central nervous system, Molecules 20 (3) (2015) 3527–3548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Horkay F, Douglas JF, Raghavan SR, Rheological Properties of Cartilage Glycosaminoglycans and Proteoglycans, Macromolecules 54 (5) (2021) 2316–2324. [Google Scholar]

- [47].Legerlotz K, Riley GP, Screen HR, GAG depletion increases the stress-relaxation response of tendon fascicles, but does not influence recovery, Acta Biomater 9 (6) (2013) 6860–6866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Simsa R, Rothenbucher T, Gurbuz H, Ghosheh N, Emneus J, Jenndahl L, Kaplan DL, Bergh N, Serrano AM, Fogelstrand P, Brain organoid formation on decellularized porcine brain ECM hydrogels, PLoS One 16 (1) (2021), e0245685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Margulies SS, Thibault KL, Infant skull and suture properties: measurements and implications for mechanisms of pediatric brain injury, J Biomech Eng 122 (4) (2000) 364–371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Ommaya AK, Goldsmith W, Thibault L, Biomechanics and neuropathology of adult and paediatric head injury, Br J Neurosurg 16 (3) (2002) 220–242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Singh G, Chanda A, Mechanical properties of whole-body soft human tissues: a review, Biomed Mater 16 (6) (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Takhounts EG, Crandall JR, Darvish K, On the importance of nonlinearity of brain tissue under large deformations, Stapp Car Crash J 47 (2003) 79–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Kleiven S, Predictors for traumatic brain injuries evaluated through accident reconstructions, Stapp Car Crash J 51 (2007) 81–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Coronado VG, McGuire LC, Sarmiento K, Bell J, Lionbarger MR, Jones CD, Geller AI, Khoury N, Xu L, Trends in Traumatic Brain Injury in the U.S. and the public health response: 1995–2009, J Safety Res 43 (4) (2012) 299–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Faul M, Coronado V, Epidemiology of traumatic brain injury, Handb Clin Neurol 127 (2015) 3–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Sack I, Beierbach B, Wuerfel J, Klatt D, Hamhaber U, Papazoglou S, Martus P, Braun J, The impact of aging and gender on brain viscoelasticity, Neuroimage 46 (3) (2009) 652–657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.