Abstract

Introduction

Oophorectomy is the treatment of choice in ovarian torsion if after detorsion the ovary looks bluish black. Ovarian preservation is advocated by many studies in the pediatric age group quoting the ability of the ovary to recover despite the appearance after detorsion.

Aims:

This study aims to review the outcome of salvage surgery (detorsion) in the management of pediatric ovarian torsion.

Materials and Methods:

This is a retrospective study of girls under 18 years with ovarian torsion treated from January 2016 to June 2021. Data were collated from records and analyzed.

Results:

Ten girls with ovarian torsion were included (mean age of 11 years). Ultrasonography and Doppler confirmed ovarian torsion in all. Emergency laparoscopy with detorsion was done in all with the mean time lapse from onset to surgery being 35 h. All the ovaries were black initially and persisted to be bluish black after detorsion. All were conserved and fixed to the lateral abdominal wall. In one child with an associated ovarian cyst, the cyst excision was also done. All girls were asymptomatic on follow-up. Ultrasonography at 3-month follow-up showed a normal-sized ovary with good blood flow in 9 out of 10 girls (90% cases). Follicular changes were seen in five girls who had attained puberty. In one girl, the ovary was very small sized and flows were not well visualized.

Conclusion:

Detorsion and oophoropexy should be the procedure of choice in pediatric patients with ovarian torsion. The gross appearance of the ovary after detorsion should not be the sole determinant for oophorectomy.

KEYWORDS: Detorsion, oophorectomy, oophoropexy, pediatric ovarian torsion

Introduction

Ovarian torsion is an emergency which demands the need for prompt diagnosis and management. Surgical treatment options include detorsion alone, oophorectomy, and detorsion with oophoropexy. Management of a detorted ovary with ischemic and hemorrhagic appearance was traditionally oophorectomy. We would like to share our experience of successful conservative management of all blue black, presumably necrosed ovaries in children and review of the relevant literature.

Aim

This study aims to review the outcome of salvage surgery (detorsion and oophoropexy) in the management of pediatric ovarian torsion.

Materials and Methods

This is a retrospective study of all girls of ovarian torsion treated at our institute from January 2016 to June 2021. Girls below 18 years of age with ovarian torsion were included in the study. The demographics, clinical presentation, operative findings, and follow-up details were analyzed.

Results

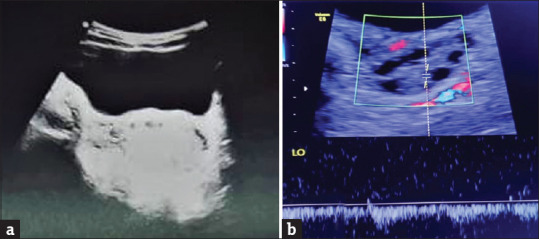

Ten girls with ovarian torsion were included in the study. The mean age of presentation was 11 years (range 6–17 years). Five girls had attained puberty. All presented with acute abdominal pain. Two girls were febrile (temperature more than 100° F) and all were tachycardic. Abdominal ultrasonography (USG) with Doppler showed enlarged and edematous ovaries with no blood flow in all girls [Figure 1a]. The tumor markers (beta-human chorionic gonadotropin and alpha-fetoprotein) were normal in all. The right ovary was affected in seven and left in three girls. One girl had an ovarian cyst along with torsion.

Figure 1.

(a) USG Doppler showing enlarged, edematous ovary with no blood flow within. (b) USG Doppler on 3 months follow up showing good blood flow within the same ovary

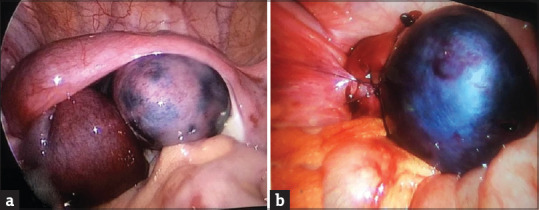

All underwent emergency laparoscopy with the mean time lapse from the onset of symptoms to surgery being 35 h (range 6–96 h). All 10 girls had black ovaries on laparoscopy. After detorsion, none of the ovaries had a change of color to pink showing definitely improved vascularity. All 10 ovaries remained bluish black [Figure 2a]. Despite the intraoperative color of the detorted ovary, all the ovaries were preserved and were fixed to the lateral abdominal wall [Figure 2b]. Oophorectomy was done in none. In one case with an associated ovarian cyst, cystectomy was done in addition (Histopathological report was suggestive of a simple ovarian cyst). The postoperative period was uneventful in all the cases.

Figure 2.

(a) Intraoperative image of the bluish black torted ovary. (b) Pexy of the detorted ovary to the lateral abdominal wall

The follow-up period ranged from 3 to 24 months (mean 8.4 months). On follow-up, all the girls were asymptomatic. The USG at 3-month follow-up showed a normal-sized ovary (the affected ovary) with good blood flow in 9 out of 10 girls (90% cases) on the Doppler study [Figure 1b]. Follicular changes were seen in only five girls who had attained puberty. In one girl, the ovary was very small sized and flows were not well visualized.

Discussion

Ovarian torsion is a surgical emergency with an incidence of 4.9 per 1,00,000 women younger than 18 years.[1,2,3,4] In children up to 52% of the torsion cases occur between the ages of 9 and 14 years (median of 11 years).[5,6] Torsion is more common on the right side due to the increased mobility of the cecum and ileum and slightly longer mesosalpinx and utero-ovarian ligament, allowing more mobility of the adnexa.[7,8]

About 25% of girls with ovarian torsion have normal ovaries. The increased risk for torsion is due to the small-sized uterus and relatively long utero-ovarian ligaments, leading to excess mobility of the adnexa.[9] Ovarian pathologies leading to torsion are mostly benign lesions such as cystic teratomas/dermoids (31%), ovarian cysts (23%–33%), and very rarely paraovarian cysts, cystadenomas, and hydrosalpinx. Malignancies are often fixed to adjacent tissues and thus are less likely to cause torsion.[10,11]

The most common presentation of ovarian torsion is acute-onset pelvic/abdominal pain. USG of the pelvis with color Doppler is the most common tool used to diagnose ovarian torsion. In cases of ovarian torsion, the sensitivity of absent arterial flows in Doppler is as low as 40%–73%, however, venous congestion is evident in up to 93% of torsion cases.[12] Computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging can be used for confirming the diagnosis in doubtful cases. Laparoscopy is considered the best diagnostic and therapeutic approach in pediatric population.

Conventionally, only detorsion or detorsion with oophoropexy is done in cases where the ovary looks pink after detorsion. Oophorectomy was done in all cases where after detorsion the ovary looked necrotic. The primary concerns in such cases were infection, adhesive intestinal obstruction, venous thrombosis, and concern for malignancy.[13,14]

Several case series have suggested that most ovaries can be salvaged and the complications of detorsion are rare.[15,16] Ovaries that appeared necrotic at the time of detorsion have been shown to function on long-term follow-up. In ovarian torsion, venous congestion occurs in most of the cases. Due to the dual blood supply, ovarian necrosis is less likely. The bluish-black appearance is primarily due to venous congestion. Studies have shown that the gross appearance of the ovary and presumed ovarian necrosis at the time of detorsion do not correlate with the current or future capacity of the ovary to develop follicles.[17] Follow-up ultrasounds have demonstrated normal Doppler flow and follicular development after 6–8 weeks.[18] Furthermore, ovarian malignancy in children is very rare and the risk of torsion with malignancy is still rarer. Hence, oophorectomy should not be done in enlarged edematous torted ovaries with the fear of leaving behind a malignancy, especially in the pediatric age group.

Interestingly, studies have shown variations in practices between pediatric surgeons and pediatric gynecologists. In a study by Aziz et al., it was reported that the incidence of detorsions done by pediatric surgeons was only 6% as compared to 94% done by gynecologists.[19] The Pediatric Health Inpatient Services (PHIS) study evaluating 43 children's hospitals also concluded that pediatric surgeons were more likely to perform oophorectomy when compared to gynecologists. Even though evidence reinforces the conservative management, the rates of oophorectomy among pediatric surgeons have not changed.[20]

In our study, despite the long duration of torsion (mean 35 h), all ovaries that were bluish black after detorsion recovered in the follow-up period. None of the girls had any complications. Follicular changes were seen in 5 (50%). In the other cases, no follicular changes were seen as they were prepubertal. They are all on regular follow-ups. They will require another USG at puberty to show functional recovery, i.e., follicular changes in the ovary.

There is no definite evidence to support the role of oophoropexy after detorsion to prevent recurrences.[3,7] Several techniques described are fixation of the ovary to the lateral peritoneum, uterosacral ligaments, or round ligament, and shortening the uterosacral ligaments by plication or suturing the ovary to the back of the uterus. Preliminary studies indicate that oophoropexy is beneficial.[21,22] We have fixed all the ovaries to avoid a recurrence because we felt that after detorsion the edematous bulky ovary tended to go back to its torted position.

Conclusion

Detorsion and oophoropexy (not oophorectomy) should be the procedure of choice in pediatric patients with ovarian torsion. The perceived risks of salvage are rare. The gross appearance of the ovary after detorsion should not be the sole determinant for oophorectomy. Oophoropexy is beneficial in preventing recurrences.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hasdemir PS, Eskicioglu F, Pekindil G, Kandiloglu AR, Guvenal T. Adnexal torsion with dystrophic calcifications in an adolescent: A chronic entity? Case Rep Obstet Gynecol. 2013;2013:235459. doi: 10.1155/2013/235459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Parelkar SV, Mundada D, Sanghvi BV, Joshi PB, Oak SN, Kapadnis SP, et al. Should the ovary always be conserved in torsion? A tertiary care institute experience. J Pediatr Surg. 2014;49:465–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2013.11.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sheizaf B, Ohana E, Weintraub AY. “Habitual adnexal torsions” – Recurrence after two oophoropexies in a prepubertal girl: A case report and review of the literature. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2013;26:81–4. doi: 10.1016/j.jpag.2013.01.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yildiz A, Erginel B, Akin M, Karadağ CA, Sever N, Tanik C, et al. A retrospective review of the adnexal outcome after detorsion in premenarchal girls. Afr J Paediatr Surg. 2014;11:304–7. doi: 10.4103/0189-6725.143134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Servaes S, Zurakowski D, Laufer MR, Feins N, Chow JS. Sonographic findings of ovarian torsion in children. Pediatr Radiol. 2007;37:446–51. doi: 10.1007/s00247-007-0429-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Oltmann SC, Fischer A, Barber R, Huang R, Hicks B, Garcia N. Cannot exclude torsion – A 15-year review. J Pediatr Surg. 2009;44:1212–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2009.02.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mellor A, Grover S. Auto-amputation of the ovary and fallopian tube in a child. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2014;54:189–90. doi: 10.1111/ajo.12172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Blitz MJ, Appelbaum H. Management of isolated tubal torsion in a premenarchal adolescent female with prior oophoropexy: A case report and review of the literature. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2013;26:e95–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jpag.2013.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Focseneanu MA, Omurtag K, Ratts VS, Merritt DF. The auto-amputated adnexa: A review of findings in a pediatric population. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2013;26:305–13. doi: 10.1016/j.jpag.2012.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Geimanaite L, Trainavicius K. Ovarian torsion in children: Management and outcomes. J Pediatr Surg. 2013;48:1946–53. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2013.04.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cass DL. Ovarian torsion. Semin Pediatr Surg. 2005;14:86–92. doi: 10.1053/j.sempedsurg.2005.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Albayram F, Hamper UM. Ovarian and adnexal torsion: Spectrum of sonographic findings with pathologic correlation. J Ultrasound Med. 2001;20:1083–9. doi: 10.7863/jum.2001.20.10.1083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rody A, Jackisch C, Klockenbusch W, Heinig J, Coenen-Worch V, Schneider HP. The conservative management of adnexal torsion – A case-report and review of the literature. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2002;101:83–6. doi: 10.1016/s0301-2115(01)00518-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kokoska ER, Keller MS, Weber TR. Acute ovarian torsion in children. Am J Surg. 2000;180:462–5. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(00)00503-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shalev J, Goldenberg M, Oelsner G, Ben-Rafael Z, Bider D, Blankstein J, et al. Treatment of twisted ischemic adnexa by simple detorsion. N Engl J Med. 1989;321:546. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Oelsner G, Bider D, Goldenberg M, Admon D, Mashiach S. Long-term follow-up of the twisted ischemic adnexa managed by detorsion. Fertil Steril. 1993;60:976–9. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(16)56395-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shalev E, Bustan M, Yarom I, Peleg D. Recovery of ovarian function after laparoscopic detorsion. Hum Reprod. 1995;10:2965–6. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.humrep.a135830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Descargues G, Tinlot-Mauger F, Gravier A, Lemoine JP, Marpeau L. Adnexal torsion: A report on fortyfive cases. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2001;98:91–6. doi: 10.1016/s0301-2115(00)00555-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Aziz D, Davis V, Allen L, Langer JC. Ovarian torsion in children: Is oophorectomy necessary? J Pediatr Surg. 2004;39:750–3. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2004.01.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Campbell BT, Austin DM, Kahn O, McCann MC, Lerer TJ, Lee K, et al. Current trends in the surgical treatment of pediatric ovarian torsion: We can do better. J Pediatr Surg. 2015;50:1374–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2015.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Weitzman VN, DiLuigi AJ, Maier DB, Nulsen JC. Prevention of recurrent adnexal torsion. Fertil Steril. 2008;90:3, e1–3. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2008.02.144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fuchs N, Smorgick N, Tovbin Y, Ben Ami I, Maymon R, Halperin R, et al. Oophoropexy to prevent adnexal torsion: How, when, and for whom? J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2010;17:205–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2009.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]