Abstract

Background

Worldwide, there has been a massive increase in child marriages following the COVID-19 crisis. In Indonesia, too, this figure has risen with Indonesia ranked amongst ten countries with the highest rates of child marriage in the world. One of the Indonesian provinces with a high incidence of child marriage cases is in Nusa Tenggara Barat (NTB).

Objective

This study aims to examine what is causing the rate of child marriages to increase since the outbreak of COVID-19 in NTB.

Participants and setting

Using snowball sampling techniques, the researcher selected 23 study participants, including ten parents (seven mothers and three fathers) with children who were married underage and 13 adolescents aged 14 to 17 years old (ten females and three males) who were married between March and December 2020. They came from two different regencies of NTB: Lombok Barat and Lombok Utara.

Methods

This study employed qualitative phenomenology as the method of inquiry. Data was obtained through semi-structured in-depth interviews and analyzed in a two-stage coding model. The results of the analysis were asserted on phenomenological themes.

Results

The data reveals that teenagers get married because: 1) they believe that marriage is an escape—from schoolwork, house chores, and the stress and boredom of studying and staying at home during the pandemic; 2) the customary law— some local customs encourage or permit child marriage; 3) there is a lack of understanding of the impact and long term implications of underage marriage; 4) economic problems— financial problems trigger parents to marry their children at a young age; and 5) the influence of the surrounding environment and peers, which encourages early marriage.

Conclusions

The findings suggest a number of recommendations for the prevention of child marriage: 1) socializing the prevention of child marriage; 2) offering alternative activities and support systems for adolescents to overcome frustration and pressure due to online learning and staying at home; 3) changing society's view that marrying children solves adolescent promiscuity, prevents pregnancy, and addresses the issue of non-marital pregnancy.

Keywords: Child marriage, Culture, COVID-19, Gender, Family, Indonesia

1. Introduction

Millions of children have been adversely affected by the COVID-19 pandemic, with the most severely affected being those in low socio-economic communities, who are already impoverished and neglected (Gupta & Jawanda, 2020). Children from disadvantaged groups are especially prone to infection and may suffer from the prolonged effects of this pandemic, such as child labor, child trafficking, child marriage, sexual exploitation and death (Fegert et al., 2020; Ghosh et al., 2020). Women and girls are at a greater risk, since they are already marginalized and vulnerable (Roesch et al., 2020; Vora et al., 2020; World Bank Group, 2020).

COVID-19 has also increased the risk of domestic violence (Anurudran et al., 2020; Dahal et al., 2020; Kofman & Garfin, 2020; Roesch et al., 2020; Sifat, 2020). The United Nations Population Fund estimated a 20% spike in domestic and sexual abuse in the world during the pandemic (United Nations Population Fund; Avenir Health, 2020). Data from U.S. police departments has offered some early analysis of the effect of COVID-19 on domestic violence in different American regions, as reported at the end of March 2020: 22% increase in domestic violence-related arrests in Portland, 18% increase in calls relating to family violence in San Antonio, 27% increase in calls for domestic violence in Alabama, and a 10% increase in domestic violence reports in New York City (Boserup et al., 2020). A European member of the World Health Organization notes that there has been a rise of 60% in the number of emergency calls, during the lockdowns imposed in several cities across Europe, from women who were subjected to threats by their abusive partner (Mahase, 2020). A survey of 38,125 women recorded in June 2020 by a human rights organization in 53 of the 64 districts of Bangladesh, reported that 4622 women had been mentally tortured, 1839 women physically abused, and 203 sexually abused (Road & Estate, 2020). Almost half a billion women are at risk in India as a result of the pandemic. The National Women's Commission of India has also recorded an increase of 94% in cases where women were raped in their homes during the lockdown (Nigam, 2020).

The pandemic has had harmful effects on the most susceptible household economies and raises the risk of child marriage (Ramaswamy & Seshadri, 2020). This claim is backed by evidence indicating that in some disaster-affected countries poor families, in times of crisis and disaster, marry their underage children as a way to pursue other sources of income or reduce the current household burden (Kim & Prskawetz, 2010; Kumala Dewi & Dartanto, 2019; Schlecht et al., 2013).

Child marriage occurs when at least one of the partners, as described in the Convention on the Rights of Children, is under 18 years of age. Child marriage or early marriage poses significant challenges to women's health, dignity and autonomy. Around 12 million girls are married every year before their 18th birthday (Paul & Mondal, 2020). Marrying early affects the growth and wellbeing of a child born to a woman who is married before 18 years old (Efevbera et al., 2017). Child marriage is substantially associated with numerous unintended births, pregnancy termination, and female sterilization (Raj et al., 2009). Women who married as children have lower schooling levels and are more likely to accept patriarchal gender roles and have lower household autonomy levels (Tenkorang, 2019).

A Save the Children's study shows that a further 2.5 million girls are at risk of marriage by 2025 due to the pandemic—the largest increase in child marriage rates in 25 years; and as many as one million more girls at risk of becoming pregnant alone this year—with childbirth the leading cause of death amongst mothers who are 15–19 years of age (Save the Children, 2020). UNFPA-UNICEF predict that COVID-19 will hinder attempts to end child marriage, possibly leading to an additional 13 million child marriages between 2020 and 2030 that could otherwise have been prevented (UNFPA-UNICEF, 2020).

Child marriage is also on the rise in Indonesia amid the COVID-19 pandemic (Arshad, 2020). UNICEF estimates that an increase in poverty in the archipelago due to COVID-19 would impair children's physical and mental growth and lead to an increase in child marriage (UNICEF, 2020).

Indonesia is the eighth-highest ranked country in the world for recorded child marriages, with one in nine females marrying before the age of 18; 16% of girls in Indonesia are married before the age of 18, and 2% are married before the age of 15 (UNICEF, 2019). Child marriage in Indonesia also affects boys that are under age. About 1 in 100 men aged between 20 and 24 years old (1.06%) were married before they reached the age of 18 in 2018 (Center Bureau of Statistics of Indonesia, 2020).

In Indonesia, at the age of 21, people are permitted to marry without parental consent. Women are allowed to legally marry with parental consent at the age of 19 (the minimum age for women's marriage increased from 16 years old, following an amendment to the Marriage Law of 1974 in September 2019). While men, as has always been the case, could marry with parental consent at the age of 19. However, parents are also allowed to request the court to issue a “dispensation” that provides legal permission for underage girls and boys to marry. As per the Ministry of Women Empowerment and Child Protection, the Regency and the Directorate-General of Religious Courts, the Ministry of Religious Affairs received 34,413 applications between January and June 2020 from parents and guardians requesting marriage dispensation (Arshad, 2020). The applications for dispensation rose significantly by 45% in the first half of 2020 compared to the total data for 2019, which was 23,700 applications (Wijaya, 2020).

The Nusa Tenggara Barat (NTB) Province ranks 7th in the national rate of child marriage (16.1%), and the province has the highest prevalence of child marriage in the Java-Bali-Nusa Tenggara regions with 15.48% (Center Bureau of Statistics of Indonesia, 2020). NTB is one of 13 provinces (out of 34 provinces) in Indonesia, which, according to data from the Ministry of Women's Empowerment and Child Protection, experienced an increase in the number of child marriages in the period covering 2018–2019, which was above the national limit (Wijaya, 2020). Based on the Office of Women's Empowerment and Child Protection for Population Control and Family Planning (DP3AP2KB) of the NTB Province, 805 requests for the dispensation of underage marriages were received in 2020. This figure is an increase of 59% from the data recorded in 2019 (332 requests). Moreover, many were religiously married and were therefore not registered because they did not apply for a dispensation to marry at a young age according to the Head of the Office for Women's Empowerment, Child Safety, Population Control and Family Planning in the NTB Province (Plan International, 2020).

In view of the fact that NTB has a high number of child marriages, and combined with the alarming spike in the number of cases since the outbreak of COVID-19, the researcher was interested in further investigating the causes of the growing number of child marriages during the COVID-19 pandemic.

This study is useful to examine how child marriage is increasing in a deeply rooted society in traditional and cultural existence. The province of NTB consists of two major islands, Lombok and Sumbawa, which belong to Kepulauan Sunda Kecil (Southeastern Islands), along with islands of the eastern part of the island of Java, Bali and the Timor Islands (Mutawali, 2016).

The original inhabitants of Nusa Tenggara Barat are the Sasak, Samawa and Mbojo. In addition to the three dominant ethnic groups, there are also other ethnic groups, such as Balinese, Javanese, Bugis, Bajo, Banjar and Malay, each of which has a different language. According to data from the NTB Central Bureau of Statistics (2016), the province has a population of 4,896,162 people, with 96.8% of the population recorded as Muslim. Other religions include Christianity, Catholicism, Hinduism, and Buddhism. Therefore, the life of the people of NTB is colored by Islamic values. Local Islam and customary law play a central role in mediating social ties and crucial life events such as birth, marriage, divorce and death (Bennett et al., 2011). Also, Lombok is known as the island of a thousand mosques since, based on statistics, more than 9000 large and small mosques are on this island of 5435 km2.

Thus, by observing the phenomenon in NTB in greater detail, we can better understand the causes behind the increasing rate of child marriages in NTB, which may also be an analogous rationale for comparable societies, particularly other Muslim groups that are religious and maintain their religious principles. According to UNICEF (2019), two Muslim-majority countries are the countries with the highest recorded levels of child marriage, namely Niger (98.3% Muslim) and Bangladesh (90.4% Muslim).

This research provides a useful insight into how to reduce the number of child marriages by identifying the root of the problem. If these causative factors can be identified, efforts can be made to dissuade or alter the views and practices that have initially led to the child marriage. As a result, at the end of this manuscript, the researcher provides recommendations in an attempt to help reduce child marriage incidence in NTB both during the COVID-19 pandemic and in the future.

2. Methodology

The study explored why the number of child marriages in NTB has increased since the COVID-19 outbreak. A qualitative phenomenological approach was used to analyze and interpret the data. Phenomenology is the study of the nature of the phenomenon and aims to understand it from the viewpoint of those who have experienced it (Casmir, 1983; MacDermott, 2002; Teherani et al., 2015). The phenomenological approach considers the ways people experience the world and how experience is perceived (Teherani et al., 2015). Phenomenology explores the individual's understanding of a phenomenon (Wellman & Krueger, 2002). The researcher studied the phenomenology of the surge in child marriages during COVID-19 by looking specifically at the situation in NTB. The researcher looked at the experiences and perspectives of parents whose underage children were married during the pandemic, as well as the perspectives of young brides and grooms. Reality is treated as pure ‘phenomena’ and absolute data in the enquiry (Groenewald, 2004). This phenomenological study was based on findings from the real context of the study. In a phenomenological study, it is important that the researcher finds the condition worth investigating and that the researcher is well informed about the case and the context (Neubauer et al., 2019). The researcher was not detached from the realities of the subjects, while the background and previous experience of the researcher were both important for the study.

The researcher used snowball sampling to select the study participants. This sampling technique is appropriate when the target data are not easily found or not readily available (Johnston & Sabin, 2010; Waters, 2015); or the participants are ‘hard to reach.’ ‘Hard-to-Reach’ is a phrase used to refer to those sub-groups of the population that may be difficult to access or involve in research (Shaghaghi et al., 2011). The researcher could not easily map out who should be interviewed, as unfortunately not all child marriages are recorded at the Office of Religious Affairs (the sub-district authority that records marriages). The researcher had however conducted research on disaster responses after a volcanic eruption in the area in 2019 and was therefore able to gain access to participants through the data collectors from this previous research, who were natives of NTB.

Considering the risk of air travel and health concerns during the pandemic, this prohibited the researcher, who is based in Jakarta, Indonesia, to travel to the island. As a result, the researcher recruited two highly qualified data collectors, who had previously assisted the researcher collect data. Additionally, it was easier for the data collectors as they spoke the same regional language as the participants, which helped the participants to feel more relaxed and open with their experiences and also meant that they had greater ease of access to conduct the interviews. The two interviewers are master students of the local state university in the province. IFW26 is a native of Lombok Barat, a 26-year-old master's student in education. She interviewed 11 participants living in Lombok Barat. IFN28 grew up in rural Lombok Utara and she interviewed 12 participants from this region.

The total number of study participants was 23, which included ten parents (seven mothers and three fathers) whose underage children had married during the COVID-19 outbreak and 13 adolescents (ten females and three males) that had married between March 2020 to January 2021. They lived in Lombok Barat and Lombok Utara (see Table 1 for the identification of the study participants). The sample size is small, but remains acceptable for a phenomenology study that emphasizes the data's depth. This design enables the research results to be useful in providing a comprehensive overview of the phenomena that has occurred. The results of the research cannot, however, be generalized. This design was employed because the data on the issues under discussion were still limited, and therefore this research is expected to form the basis for further research using a larger sample.

Table 1.

Identification of the Study Participants

| No | Initial | Status | Gender | Age | Location |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | FWP38-1 | Parent | Female | 38 | Lombok Barat |

| 2. | FNP36-2 | Parent | Female | 36 | Lombok Utara |

| 3. | FWP35-3 | Parent | Female | 35 | Lombok Barat |

| 4. | FWP42-4 | Parent | Female | 42 | Lombok Barat |

| 5. | FWP30-5 | Parent | Female | 30 | Lombok Barat |

| 6. | FNP30-6 | Parent | Female | 30 | Lombok Utara |

| 7. | FNP44-7 | Parent | Female | 44 | Lombok Utara |

| 8. | MNP35-8 | Parent | Male | 35 | Lombok Utara |

| 9. | MNP37-9 | Parent | Male | 37 | Lombok Utara |

| 10. | MNP46-10 | Parent | Male | 46 | Lombok Barat |

| 11. | FWA16-11 | Adolescent | Female | 16 | Lombok Barat |

| 12. | FWA15-12 | Adolescent | Female | 15 | Lombok Barat |

| 13. | FWA16-13 | Adolescent | Female | 16 | Lombok Barat |

| 14. | FWA17-14 | Adolescent | Female | 17 | Lombok Barat |

| 15. | FNA14-15 | Adolescent | Female | 14 | Lombok Utara |

| 16. | FNA16-16 | Adolescent | Female | 16 | Lombok Utara |

| 17. | FNA16-17 | Adolescent | Female | 16 | Lombok Utara |

| 18. | FNA14-18 | Adolescent | Female | 14 | Lombok Utara |

| 19. | FNA17-19 | Adolescent | Female | 17 | Lombok Utara |

| 20. | FNA16-20 | Adolescent | Female | 16 | Lombok Utara |

| 21. | MNA16-21 | Adolescent | Male | 16 | Lombok Utara |

| 22. | MWA15-22 | Adolescent | Male | 15 | Lombok Barat |

| 23. | MWA16-23 | Adolescent | Male | 16 | Lombok Barat |

The first gatekeepers in Lombok Barat were relatives of IFW26: her cousin (FWA15-12), the cousin's husband (MWA16-23), mother (FWP38-1) and father (MNP46-10). She gained access to interviews with more participants from Lombok Barat through this family. While IFN28's first contact in Lombok Utara was FNP30-6, a 30-year-old mother who provided access to IFN28 to interview more participants. The interviewee guided the interviewer to a sample of several more interviewees. In turn, that interviewee provided the name of at least one more potential interviewee, and so on, with a sample expanding like a rolling snowball (Bhattacherjee, 2012; Cohen & Arieli, 2011; Patton, 1990).

The research participants were not balanced in terms of gender, with seventeen female respondents and only six males. The reasons for the gender imbalance were: most of the children who married young were female; most of the participants identified their female friends or people they knew as the next potential subjects; while also some potential male participants refused to be interviewed. Seventeen participants lived in rural villages. All the mothers interviewed were stay at home mothers, who did additional work in rice fields and farming. Occupations of the fathers included driver, farmer and unemployed. Five adolescents were still in junior high school, and eight were in senior high school.

The researcher stopped recruiting more study participants when there were no further cases either available or accessible and considered the data was sufficient enough to answer the research question comprehensively. Due to the sensitive nature of the interview topic, anonymity was assured to all the participants. The interviewer explained the research's scope and purpose and informed consent was signed by the participants who agreed to be interviewed. The researcher also requested the parents' consent with the underage participants; the parents signed the consent letters for their children, even if, in Indonesia, when an underage child is married, they are considered capable of acting on their own. All the participants knew that they had the right to withdraw from the analysis without being questioned if they felt dissatisfied at any point. The researcher obtained a research approval letter to collect data from the university research center where the researcher was affiliated.

The primary source of data was semi structured in-depth interviews. Interviews were conducted from 4 to 12 January 2021. There were two main exploratory questions for the participating parents: 1) Why do you think your underage child decided to marry young? 2) How do you feel about it? While the interviewers also asked the adolescent participants two main exploratory questions: 1) Why did you marry young? 2) How do your family and school feel about it?

The interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed. The transcription was then analyzed, and some excerpts from the interview that explained the findings of the research were translated by a native speaker using vernacular English. A member check was carried out to ensure accuracy, the researcher forwarded the findings and conclusions to the interviewers, and the interviewers discussed the findings with the participants, the researcher removed any information that the participants had not agreed to share in the final paper, where requested.

The researcher used NVivo to arrange and analyze the data. The researcher also produced a lengthy memo in the NVivo program that could further affirm ideas and examine the perceptions and experiences of the participants. Analytical memos provide a researcher with the means to track their thoughts during research and to code memos as additional evidence of the thesis (Saldaña, 2016). Analytical memos tracked written opinions, which were then expressed and rewritten, forming a sustained, iterative cycle for the development of increasingly rigorous and insightful analyses.

Throughout the analysis, the researcher assured a clear orientation towards the phenomena under study and studied them one by one, and then all together. This last step emphasizes the process of consciously considering how data corresponds to the emerging understanding of the phenomenon and how each enhances the meaning of the other. Hermeneutic phenomenology is deeply embedded in the individual's perception or experiences (Neubauer et al., 2019). Hermeneutic phenomenology encourages researchers to take liability for their preconceptions and reflect on how their subjectivity is an integral component of research (Kerry-Moran & Aerila, 2019). The researcher was fully cognizant of the individual's past and took note (analytical memo) of the influence they had on the experience (Neubauer et al., 2019). Hermeneutic phenomenology is not tied to a single set of analytical techniques; instead, it involves multiple analytical activities (Bynum & Varpio, 2018).

The researcher used the Miles et al. two-stage coding model to interpret the findings (Miles et al., 2014). The data did not flow linearly as the study progressed; the data was indeed continuously analyzed. In the first round of coding, interview transcripts were coded separately. During the second coding, the researcher re-configured and re-analyzed the first coding process results. The main objective of second-cycle coding was to specify the categorical, thematic, logical and theoretical meaning of the data. The researcher incorporated codes, added more codes and then removed some codes to infer the study results. The researcher provided a summative interpretation of the results based on an analysis of the evidence. The phenomenological themes of the study were the results of the research.

3. Results

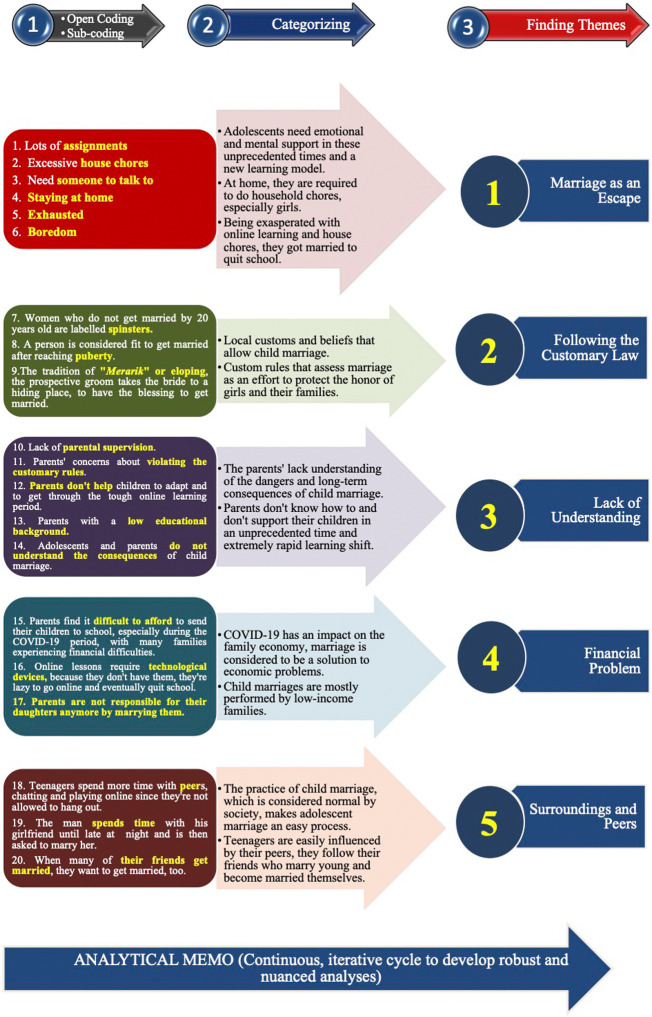

In the first cycle of coding, the researcher identified twenty open-codes of data, which are shown in the figure below on the far left (See Fig. 1 ). In the meantime, the list containing 10 codes in the middle of the image is the category generated in the second coding cycle. The researcher carefully analyzed the codes and categories and identified five phenomenological themes as the results of the study.

Fig. 1.

Data analysis process and research finding.

The data shows that child marriage has been on the increase since the outbreak of COVID-19 because: 1) adolescents believe that marriage is an escape; 2) community trust in customary law; 3) parents' lack of understanding of their children's concerns and the impact and long-term implications of child marriage; 4) family financial problems; 5) peer influence and the social environment.

3.1. The view that marriage is an escape

Marriage has been used as escape by the adolescents' to avoid both homework and housework. The teenagers were tired of studying online, trusting their boyfriends/girlfriends and feeling relaxed and inseparable, and eventually decided to get married. The adolescents in this study have mainly spoken about this set of patterns as reasons why they got married at a young age.

FWA16-11, 16 years old, was in grade 10 when she got married last year. She said she was under pressure from several school assignments. She then confided in her boyfriend, who was 18 years old. They eventually agreed to marry.

Since learning had moved online, I felt under a great deal of pressure. The teachers kept giving assignments. That's exactly what made me sad and frustrated. I had been venting my feelings and trusted my boyfriend. Since he paid more attention to me than my parents at home, I finally decided to get married.

(FWA16-11, Female, 16 years old, Lombok Barat)

FNA14-15, was just 14 years old and only in grade 8 when she got married. She left school once she was married in August 2020. She complained about how tired she was doing the teacher's never-ending assignments. FNA14-15 was relieved every time she vented to her boyfriend, and she felt inseparable from her boyfriend. Her boyfriend (MNA16-21, 16 years old) thought the same way. They finally got married. The two were interviewed at the same time. MNA16-21 chuckled as his wife shared their story.

I kept getting assignments from the teachers during online learning. I didn't know where to start when the tasks were piling up. I was thinking about leaving school because of my teacher's workload, but I felt better after sharing my feelings with my boyfriend. Until one day, my teachers gave me a lot of assignments at the same time. I felt down suddenly. After the incident, I wanted to get married because I was tired of studying.

(FNA14-15, Girl, 14 years old, Lombok Utara)

FWA16-13 felt that her boyfriend had listened to her problems. She felt cared for and protected. Her boyfriend asked her to get married because he was tired of school, too. They specifically claimed that they got married to avoid online learning: “Most of the time, I trusted my boyfriend because he cared so much for me. So, we agreed to get married and to run away from our online learning at school.” (FWA16-13, Female, 16 years old, Lombok Barat).

Another factor that made these teenagers want to marry was the fatigue of doing household chores from parents, particularly girls. FWA17-14 complained that she was exhausted because she had to take care of household duties, which also interfered with her studies. She was married to a much older man. Her husband is around 42 years old, the same age as her father. “I had a lot of household chores to do, even though I'd also been busy studying online because I'm a girl. If I didn't do it, my parents scolded me. My responsibilities at school and my obligations at home were clashing.” (FWA17-14, female, 17 years old, Lombok Barat).

FNA16-16 also protested about domestic work, which had become her responsibility since distance learning had begun. Tired and bored, and in order to be free from these responsibilities, she married. “I had to do a lot of domestic work, such as washing, cleaning, cooking, and a lot more, which are usually non-stop. I found it difficult to meet both my home and school responsibilities. So I wanted to get married in an attempt to escape the demands.” (FNA16-16, Girl, 16 years old, Lombok Utara).

FNA14-18's parents asked her to do domestic work and asked her to help them in the rice fields. Often she was sent to the fields during school hours (online). FNA14-18, who was just 14 years old when she was married, felt that the only way to escape this multitude of duties was to get married.

How could I not be mad, because there were many school assignments, and my parents also added more things for me to do, such as sweeping, washing dishes, washing clothes, cooking, and going to the fields. I was annoyed that sometimes I was told to go to the fields when I was meant to be studying online. That's why I wanted to marry.

(FNA14-18, female, 14 years old, Lombok Utara)

Exasperated by online learning and homework, adolescents in this study said they had married to avoid these responsibilities. This was also shared by male participants such as MWA16-23 and MWA15-22. MWA16-23 married FWA15-12 in June 2020. At the time of the study they were 16 and 15 years old and were living in the house of MWA16-23's parents. “I only wanted to drop out of school and to get married to my girlfriend, to be free from online education.” (MWA16-23, male, 16 years old, Lombok Barat).

MWA15-22 is just 15 years old, and his wife is the same age as him. She declined to be interviewed because she did not feel well. She was in the first trimester of her pregnancy. MWA15-22 also lamented about the pressure of online schools that made him marry at a young age. “Getting married was my wish without any coercion, because I felt bored studying online” (MWA15-22, male, 15 years old, Lombok Barat).

3.2. The customary law

There are some local traditions and beliefs that make it possible for a child to marry and promote the early start of a family. For example, the community's belief that women who have not become married by the age of 20 are considered spinsters. As expressed by FNP36-2, she is a housewife who also helps her husband work in a rice field. She believes a girl should marry young rather than be old and unmarried. So when she was proposed to, she felt that she should accept the proposal.

My daughter had been dating for a year. She was 16 years old. The two of them loved each other, and the man was serious about the relationship. Even though her boyfriend was just 19 years old and worked some odd jobs, when he proposed to her, well, it's better to get married. It's not good for a girl to decline if she's been asked because she can become an old maid.

(FNP36-2, female, 36 years old, Lombok Barat)

The wider society also believes that a person is considered eligible to marry after reaching puberty. Many parents think that if their child is pubescent, they can then get married, “I'm allowing my son to marry even though he's still in school. Moreover, I believe that I've merely accepted it, it's his destiny, his life. My child might want to get married because he likes the girl. If the child is pubescent, he can marry. I was married at the age of 14, too. That's okay!” (FWP30-5, female, 30 years old, Lombok Barat).

There is another unique tradition in NTB, namely eloping, or in the local language “Merarik,” or “Merarik Kodek,” which is the tradition of a groom taking the bride to a hiding place to get the blessing to marry. Some men purposefully drop their girlfriends' home at night to get the blessing of their parents and family to get married. People often believe that if a man takes a girl out at night or returns home late, he should then marry her. “The main reason for child marriage is customary norms. When a man brings my daughter home at midnight, it means they are ready to get married.” (FWP42-4, female, 42 years old, Lombok Barat).

MNA16-21 married his girlfriend FNA14-15 last year. One night, FNA14-15 stayed overnight at a girlfriend's home, with her grandma's permission, but not her mother. Her mother was searching for her and she called a few times, yet the phone was not answered. Her mother sent her a message: “Go home now or I will take your cellphone and you can't go to school anymore.” Too scared to go home, FNA14-15 asked her boyfriend MNA16-21 to get married. According to tradition, if the girl comes home at night, the girl has to be married. “That night, my girlfriend was scared to go home, she begged me to marry her. I love her, so I married her” (MNA16-21, male, 16 years old, North Lombok).

A father from Lombok Utara, MNP35-8, said he was initially angry when he found out that his son had secretly married a young girl. He regretted that his son was just 17 years old and that he had not finished school. He wanted to send his son's wife back to her family, but the woman's family didn't want to take her back. Both of them are still married.

Suddenly, I learned that my son had been married secretly. I was so angry when I heard that. My son hasn't finished school yet, but he dared to marry in secrecy, and it broke my heart to hear that. I wanted to send the girl back, but the girl's family didn't want to take their child back because, according to tradition, she had to be married.

(MNP35-8, male, 35 years old, Lombok Utara)

3.3. The parents lack understanding

Some adolescents in this study even said that their parents did not understand or care for them. FNA17-19, commented her parents did not care about her, until she was too involved with her boyfriend and eventually got pregnant. “There was never any guidance from my parents because they never paid any attention to all this, even though they were at home. I became pregnant. So we got married” (FNA17-19, female, 17 years old, Lombok Utara).

FWP35-3, a mother from West Lombok, also implied that she allowed her 16-year-old daughter to marry for fear of being pregnant first, “When my daughter wanted to get married, I let her get married, rather than have bad things happen.” (FWP35-3, female, 35 years old, Lombok Barat).

The teens also regretted that their parents did not support them to adapt and get through a challenging time of online learning. They added that their parents did not know how to and did not help children in this unprecedented time and incredibly rapid change in learning methods. When these girls became intimate with their boyfriends, their parents did not forbid them to marry.

My girlfriend and I, now my wife, have just graduated from junior high school and just started senior high school. I asked her to get married because she said she was tired of online schooling, a lot of tasks, a lot of demands from her parents. I felt tired at home, too. So that's what prompted my wife and I to get married. Our parents did not forbid, they may even be content.

(MNA16-21, male, 16 years old, Lombok Utara)

The parents who participated in this study did not really understand the effect of child marriage on children. They had given their children permission to marry easily, for reasons that are not compelling, such as when their children come home late, after sunset. The normal tradition of girls being escorted home by a man late at night and then needing to be married off is known as “Mararik Kodek.” This belief is still strongly held by the parents that were interviewed. The parents did not seem to think about the more severe implications of getting married so soon, such as their health, economic situation and the physical or mental abuse that might happen to the girl. So, it appears that they're more worried with their daughters being considered a spinster. They are more afraid that their children do not obey the social or cultural standards and consequently how the family will be viewed themselves.

FNP44-7, a 44-year-old woman, said, “Thank God, I don't need to worry anymore, one by one my daughters are married. Instead of hearing the neighbors' gossip about my girls coming home at night, they'd better get married.” (FNP44-7, female, 44 years old, Lombok Utara).

Some parents have a low level of education background. They are not aware of the consequences of child marriage. MNP37-9, Lombok Utara's father said, “My daughter asked permission to marry her boyfriend. I can see that her boyfriend is decent. Visiting our house frequently. So, rather than my daughter just staying at home, just doing online learning. I allowed her to get married” (MNP37-9, male, 37 years old, Maluku Utara).

3.4. The economic problem

COVID-19 has an impact on the family economy. Marriage is considered to be a solution to economic problems. Parents find it difficult to afford to send their children to school, especially during the COVID-19 period, with many families experiencing financial difficulties.

Schools are using expensive smartphones right now, and I don't have any money. My daughter's boyfriend asked her to marry. Both of them are still in school. But instead of just staying at home and getting bored, it's better to get married.

(FWP30-5, female, 30 years old, Lombok Barat)

Online courses require technological devices. Some adolescents don't have them and then they're becoming lazy to go online and eventually leave school. Low-income families typically perform child marriages. Parents no longer need to be responsible for their daughters by marrying them.

I never attended class during online school. I've never had a cellphone. I was lazy to be in the online class. I never did assignments, either. Gradually, I felt like I didn't have any more activities. I already had a boyfriend, so I just decided to get married.

(FNA16-20, girl, 16 years of age, North Lombok)

3.5. The influences of the surrounding environment and peers

The practice of child marriage, which is considered normal within society, encourages adolescents to marry young. They used to spend a lot of time with friends before the COVID outbreak. They would only chat online, speak and play online throughout the outbreak of the pandemic. They got lonely, and some of them chose to marry during the pandemic. Some others also followed their lead. “Yes, we generally hang out with friends before the pandemic, eat together, having coffee. It's been rare since COVID. OK, I'm bored. My boyfriend and I have been so close. I saw a friend of mine get married, so I also got married, basically so I wouldn't get bored.” (FNA16-16, female, 16 years old, Lombok Utara).

Getting married because they see their friends getting married is also one of the reasons FNA16-20 got married, even though she had not graduated from school. She saw some of her friends get married, so she got married, too. “I saw my friends got married, I decided to get married, my boyfriend agreed. It's fun to always be together.” (FNA16-20, female, 16 years old, Lombok Utara).

4. Discussion

The first explanation why child marriage numbers have risen in NTB since the pandemic is that these adolescents have chosen to marry because they think marriage is a way to escape the pressure of school and home. This notion was by far the most common explanation provided. School closures or a lack of outdoor opportunities have the overall potential to influence children's everyday lifestyle, impacting their mental wellbeing in many ways (Ghosh et al., 2020). The adolescents complained of the heavy workloads at school and their parents' demands during the pandemic. In these tumultuous times, they said they needed more emotional and mental support. Parents were identified as being unhelpful. Most of the time, assistance came from their girlfriends/boyfriends. Since they felt comfortable and listened, they were assured that marriage was really a way to get away from school pressure. As social animals, we humans have a deep desire to belong — to feel in close touch with others (Myers, 1999). They found the feeling of bonding and connectedness in their girlfriends/boyfriends.

Interestingly, it appears that all these teenagers decided themselves to become married, rather than through a forced marriage. Just one woman out of the sixteen teenagers interviewed married a much older person (42 years old). The majority of the female adolescents are married teens or men between 20 and 30 years of age. While the three male adolescents married younger or the same age female.

If a woman gives birth under the age of 18, it carries a significant risk to the mother and child's physical and mental health. It also affects the family economy and the stability of her family. While if her husband is also under the age of 18, the effect is likely to be even greater. Child spouses have induced intimate partner violence (Speizer & Pearson, 2010). The first two years of marriage are a phase of marital adjustment, as verbal violence and physical aggression of husbands and wives frequently occur at this time (O'Leary et al., 1994; Schumacher & Leonard, 2005). Male teenagers appear to have trouble regulating their emotions. Empirical analyzes were performed within the causal—analytical context of a sample of normal adolescent males, indicating that circulating testosterone levels in the blood had a clear causal effect on induced aggressive activity (Olweus et al., 1988). So this period of marital transition would be difficult for couples who are still in their teens.

Marriage is one of the most significant structures affecting people's lives and wellbeing; it regulates sexual relations and facilitates interaction amongst spouses (Stutzer & Frey, 2006). People have different reasons to decide to marry. It is too juvenile, short-minded and should be discouraged to be married in an effort to escape from school and home duties. The adolescents thought that getting married would solve their issues, but if they get married early, there would be a risk of much greater and more complicated problems. Child marriage is highly correlated with physical and emotional violence (Nasrullah et al., 2014). It influences girls' education, health, psychological wellbeing, and their offspring's health (Nour, 2009). It accelerates the risk of sexually transmitted infections, cervical cancer, malaria, obstetric fistulas and maternal mortality (Gage, 2013). Their descendants are at an increased risk of premature birth and, potentially, neonatal or infant mortality (Raj, 2010). Moreover, child marriage has negative economic consequences. Girls who are married young are typically unable to access further education to provide them with the skills, knowledge and job opportunities required to help their families (Bartels et al., 2020; Sarfo et al., 2020).

It has been found that marriage goes hand in hand with higher happiness levels in a large number of studies for different countries and time periods (e.g. Diener et al., 2000). Married people have better physical and psychological health, and they live longer; premature mortality was found to be lowest for married persons, followed by cohabiting persons (Drefahl, 2012). Survey evidence has linked marriage to income, health, mortality, children's achievement and sexual satisfaction (England et al., 2001). However, not every marriage has a happy ending—economic, psychological and mental readiness seem to be essential to a content and healthy marriage (Fincham et al., 2006). The NTB Child Protection Agency recorded data related to early marriages during the pandemic. From January to September 2020, there were 805 applications for marriage dispensation at the Religious Courts, an increase of 59% from the 332 cases recorded in 2019 (Plan International, 2020). The head of the NTB National Population and Family Planning Agency (BKKBN) said that many teenagers who marry at an early age are not mentally ready, so they can easily divorce when problems occur. He added that many early marriages or marriages under the age of 21 are suspected of having a high rate of divorce. He explained that 21.55% of the residents of the NTB were widows and widowers (Nursyamsi, 2016). This trend may impact the way marriage is viewed in society, whereby it is seen as easy to get divorced and socially acceptable if it does not work out as they had originally planned.

The second result of this study is that adolescents in NTB marry because they obey some of society's norms or customs. One of the cultural traditions clarified by the participants was “Mararik Kodek,” so that those girls, for reasons of coming home at night and fear of negative public opinion, asked their boyfriends to marry them. Some parents recommend that their children get married simply because they come home late at night. In Muslim society, girls are socialized and forced to “hold the name of the family” by restricting their sexual activity before marriage (Smith-Hefner, 2005), and parents prefer to marry their daughters at an early age to prevent premarital intercourse. Muslim religion attaches great importance to premarital virginity (Imtoual & Hussein, 2009). Patriarchal cultures tend to monitor the sexuality of women in order to govern the descent and transition of women (Amy, 2008).

Another tradition that the people of NTB believe is that children who have reached puberty are ready to get married. This belief is commonly held by some Muslims, who claim that as long as a young person is seen to be “grown-up” or reaches puberty, he is considered worthy to be married (Jones, 2001). They use the example of Prophet Muhammad's marriage to Aisha at the age of six as a basic justification for child marriage. However, many Muslim scholars clarify that no religious teachings or Islamic law explicitly endorse the prevalence of child marriage because the object of marriage in Islam is to promote a happy and satisfying relationship between couples (Kasjim, 2016).

The above two beliefs are the customary law rooted in Islamic teachings, as its people of NTB are considered very Islamic. In certain cultures, faith has become the key reference point for human beliefs, which have become an integral part of an episode of a person's life. According to Islamic belief, marriage is the most significant period in a Muslim's life (Al-Hibri & el Habti, 2006).

Many Indonesians believe that early marriages can prevent adultery (adultery is a major sin in Islam). Religious leaders and teachers usually promote marriage to prevent any premarital sex that their culture finds extremely unethical (Fachrudin, 2016). This perception suggests that it is easier to be married than to be sinful (Hull, 2016; Petroni et al., 2017). Having a child out of wedlock is viewed negatively and is often regarded as one of the major causes of child marriage in Indonesia.

Several social media movements (as well as offline discussions) have occurred in recent years in Indonesia, inviting young people to marry early. A celebrity on Instagram and Facebook (a public figure in social media), who comes from NTB, launched the Indonesian Movement without Dating and the Youth Marriage Movement. He also wrote the best-selling book Berani Nikah, Takut Pacaran or Brave to Marry, Scared of Dating (Kumparan, 2018). This book sold more than 22,000 copies. In his book, he writes that dating is the same thing as promiscuity and adultery, and therefore seems a sin. Not dating is a remedy, just as getting married early is a solution to prevent adultery. This perception can be deceptive if it is understood to be and may encourage adolescents to marry early, despite the very harmful consequences of child marriage, which often causes new, more complicated issues.

FNA17-19 was the only teenage participant who appears to have become pregnant prior to becoming married. Other participants, however, were hesitant to discuss this issue. Petroni et al. (2017) has shown that sexual intercourse, unintended pregnancy, and school dropout frequently precede child marriage in Africa. In South Asia, it has also been shown that early marriage's primary factor is the urge or need to preserve the family's good reputation and social status (Alemu, 2006). Maintaining the family's good name and social status is also explained by the participants in this research. This issue certainly warrants further investigation in a future study but would need a larger amount of subjects willing to discuss the issue in greater detail.

There is a noticeable disparity between Asian and Western cultures in both marriage and singleness attitudes. While marriage is widely accepted as a personal choice in the West, people in many Asian countries – including Indonesia – still believe that marriage extends beyond their personal choice and considers it a religious demand or a social obligation (Himawan, 2019).

Marriage is considered a collective instead of an individual activity involving the married couple and their entire family, extended family, and community (Bennett, 2013; Delprato et al., 2017). Shared values and beliefs related to early marriage are created through interpersonal relationships and social networks. In this case, members of the group will exert social pressure on each other by punishing their failure to comply and thus influence their expectations of early marriage (Delprato et al., 2017; Gage, 2013).

The third explanation for these teenagers to be married during a pandemic is that they needed help and could not get it from their parents. Parents also showed no understanding of the implications of a young marriage. So when their children came home late, they were told to get married. Parents do not think about any further severe consequences, such as the effects of health, economics and abuse on the child. Many of these parents have a poor degree of the educational experience. They will easily approve their children's request to be married. The data also shows that the parents did not give enough help and support when needed during the pandemic. Some of the teens were marrying to escape their parents. Bhan et al. (2019) assess the parent-child relationship's impact in early teens (aged 12 years) on girls' early marriage. Survey data from India, Ethiopia, Vietnam, and Peru was analyzed. They found that parent-child relationship quality and communication in early teens help protect against girls' very early marriage.

Another explanation is that some married underage because of their family's economic situation. Childhood poverty is closely related to marriage in adolescence (Ramaswamy & Seshadri, 2020). Children act as a saving mechanism to help families resolve their economic crisis (Kim & Prskawetz, 2010). Marrying daughters often enables the family to receive money, or at least relieve parents of the burden of caring for that girl. Nevertheless, the girls are regarded as nothing more than land (Swain, 2020). Child marriage is, first and foremost, the result of an economic need. Girls are expensive to feed, clothe, and teach. Marriage provides a dowry to the family of the bride. The younger the girl, the higher the dowry, the earlier the economic burden of raising the girl is lifted (Nour, 2009).

The last reason these adolescents surveyed explained as the reason they got married young was their peers' influence. Peer pressures lead young people to partake in disruptive, health-compromising activities that they would otherwise not have engaged in on their own (Do et al., 2020; Johansen, 2014). Indeed, decades of studies have shown that peer participation in risk-taking behaviors is a consistent and robust predictor of adolescent risk-taking behaviors (Do et al., 2020).

In some studies, economic reasons and social, cultural background have been addressed as the reasons behind child marriage. Globally, there were three key factors driving child marriages, i.e., poverty, the need to improve social relations and the expectation that security is offered (Mahato, 2016; Nour, 2009). Mahato (2016) found that the key causes of child marriage in Nepalese society were a lack of awareness, limited access to information, low level of government policy knowledge, investment in girls as a waste of money, fear of remaining single, increased dowry, lower wedding ceremony costs, and poor law enforcement. Lack of knowledge has also been observed in NTB. Parents and teenagers were not aware of the implications of child marriage. Fear of becoming unmarried was also addressed by two parents, who chose to marry their young daughters rather than let them become spinsters. The participants in this study did not mention poor law enforcement, but the researchers could see it from their explanations, as they perceived customary and religious law as stronger than the laws of the state. They married even though they knew the government regulated the marriage age, and they were not qualified.

Khanom and Islam Laskar (2015) discussed the cause of child marriage in the district of Assam, India. Research has shown that low-income family economic conditions lead to higher reported cases of child marriage; lower parents' educational level means higher cases of child marriage; social norms and customs are linked to the number of child marriage; large family size leads to the incidence of child marriage, and increased misuse of modern gadgets such as cell phones and TV. Compared to the reasons found in this report, one area that has not been found in other studies involves the desire to avoid online learning as a justification for early marriage. Despite a lack of previous research supporting this, due to the fluid nature of the COVID-19 pandemic, it remains an area of concern that the policymakers, parents, and schools need to take into account, as it appears that many adolescents are having trouble keeping up with the new learning methods and that they have decided to marry as a way to escape the pressure of online learning.

5. Conclusion

With the knowledge that the most mentioned reason explaining why these teens get married because they feel that it is the easiest way to stop having to do homework and household tasks, learning strategies during the pandemic and how parents handle children's homework and housework needs to be examined further. Strategies to avoid early marriage, including parental role models, are very important elements in establishing a healthy and comfortable home environment, offering children proper encouragement and criticism, and not failing to plan activities in line with their wishes. These teenagers complain that their parents did not have adequate emotional and mental help during the pandemic's difficult period. The relationship they had with their boyfriends/girlfriends increased their confidence in getting married. This is also something that needs to be discussed in the family because parents' encouragement is very important for these young people to adapt. Additionally, the availability of people that these adolescents can turn to in times of stress and turmoil to talk through their problems if they feel that they cannot speak openly to their parents might also lead to a reduction in child marriages.

Some recommendations for the prevention of child marriage include socializing the prevention of child marriage; providing alternative activities and support structures to overcome child distress and pressure related to online learning and remaining at home; shifting society's perception that child marriage solves teenage promiscuity, and avoids non-marital pregnancy.

The limitations of this study include the small sample size and the sampling techniques. Researchers are often critical of snowball sampling by arguing that the process cannot ensure sample diversity, which is a required condition for valid research findings (Kirchherr & Charles, 2018). Therefore, results from a snowball study will not be generalizable (Morgan, 2008). The researcher proposes that the research should proceed with larger and more diverse samples in the future when the pandemic has ended, allowing for this process to occur successfully. Although the interviewers were chosen due to their ability to gain access to the research participants, the possibility of increased anonymity through interviewers that are unknown in the community might also help the participants speak more freely in an attempt to learn more about the impact of pre-marriage pregnancies.

Declaration of competing interest

The author has no conflict of interest to declare related to this work. All funding obtained for the research was provided through a 2021 interdisciplinary research grant from UIN Syarif Hidayatullah, Jakarta, Indonesia and did not affect the design, methodology or reporting of the study findings.

References

- Alemu, B. (2006). Early marriage in Ethiopia : Causes and health consequences. Exchange Organizational Behavior Teaching Journal, (July), 4–6.

- Al-Hibri A., el Habti R.M. In: Sex, marriage, and family in world religions. Browning D.S., Green M.C., Witte J. Jr., editors. Columbia University Press; New York, New York, USA: 2006. Islam; pp. 150–225. [Google Scholar]

- Amy J.-J. Certificates of virginity and reconstruction of the hymen. The European Journal of Contraception & Reproductive Health Care. 2008;13(2):111–113. doi: 10.1080/13625180802106045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anurudran A., Yared L., Comrie C., Harrison K., Burke T. Domestic violence amid COVID-19. International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics. 2020;150(2):255–256. doi: 10.1002/ijgo.13247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arshad, A. (2020, October 3). Child marriages on the rise in Indonesia amid Covid-19 outbreak. The Straits Times. Retrieved from https://www.straitstimes.com/asia/se-asia/child-marriages-on-the-rise-in-indonesia-amid-covid-19-outbreak.

- Bartels S.A., Michael S., Bunting A. Child marriage among Syrian refugees in Lebanon: At the gendered intersection of poverty, immigration, and safety. Journal of Immigrant & Refugee Studies. 2020;1–16 doi: 10.1080/15562948.2020.1839619. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett L.R., Andajani-Sutjahjo S., Idrus N.I. Domestic violence in Nusa Tenggara Barat, Indonesia: Married women’s definitions and experiences of violence in the home. The Asia Pacific Journal of Anthropology. 2011;12(2):146–163. doi: 10.1080/14442213.2010.547514. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett L.R. Early marriage, adolescent motherhood, and reproductive rights for young Sasak mothers in Lombok. Wacana, Journal of the Humanities of Indonesia. 2013;15(1):66. doi: 10.17510/wjhi.v15i1.105. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bhan N., Gautsch L., McDougal L., Lapsansky C., Obregon R., Raj A. Effects of parent–child relationships on child marriage of girls in Ethiopia, India, Peru, and Vietnam: Evidence from a prospective cohort. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2019;65(4):498–506. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2019.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacherjee, A. (2012). Social science research: Principles, methods, and practices.

- Boserup B., McKenney M., Elkbuli A. Alarming trends in US domestic violence during the COVID-19 pandemic. The American Journal of Emergency Medicine. 2020;38(12):2753–2755. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2020.04.077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bynum W., Varpio L. When I say … hermeneutic phenomenology. Medical Education. 2018;52(3):252–253. doi: 10.1111/medu.13414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casmir F.L. Phenomenology and hermeneutics: Evolving approaches to the study of intercultural and international communication. International Journal of Intercultural Relations. 1983;7(3):309–324. doi: 10.1016/0147-1767(83)90035-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Center Bureau of Statistics of Indonesia. (2020). Prevention of child marriage acceleration that cannot wait.

- Central Bureau of Statistic NTB . 2016. Percentage of population by regency / municipality and religions in Nusa Tenggara Barat Province 2016. Mataram. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen N., Arieli T. Field research in conflict environments: Methodological challenges and snowball sampling. Journal of Peace Research. 2011;48(4):423–435. [Google Scholar]

- Dahal M., Khanal P., Maharjan S., Panthi B., Nepal S. Mitigating violence against women and young girls during COVID-19 induced lockdown in Nepal: A wake-up call. Globalization and Health. 2020;16(1):84. doi: 10.1186/s12992-020-00616-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delprato M., Akyeampong K., Dunne M. Intergenerational education effects of early marriage in sub-Saharan Africa. World Development. 2017;91:173–192. doi: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2016.11.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Diener E., Gohm C.L., Suh E., Oishi S. Similarity of the relations between marital status and subjective well-being across cultures. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology. 2000;31(4):419–436. doi: 10.1177/0022022100031004001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Do K.T., Prinstein M.J., Telzer E.H., Do K.T., Prinstein M.J., Telzer E.H. The Oxford handbook of developmental cognitive neuroscience. 2020. Neurobiological susceptibility to peer influence in adolescence. (April 2019) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Drefahl S. Do the married really live longer? The role of cohabitation and socioeconomic status. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2012;74(3):462–475. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2012.00968.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Efevbera Y., Bhabha J., Farmer P.E., Fink G. Girl child marriage as a risk factor for early childhood development and stunting. Social Science & Medicine. 2017;185:91–101. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.05.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- England P., Waite L.J., Gallagher M. The case for marriage: Why married people are happier, healthier, and better off financially. Contemporary Sociology. 2001 doi: 10.2307/3088984. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fachrudin F. Kompas; 2016. Ketentuan soal perzinahan dalam KUHP dinilai perlu diperluas. [Google Scholar]

- Fegert J.M., Vitiello B., Plener P.L., Clemens V. Challenges and burden of the coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic for child and adolescent mental health: A narrative review to highlight clinical and research needs in the acute phase and the long return to normality. Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health. 2020;14:1–11. doi: 10.1186/s13034-020-00329-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fincham F.D., Hall J., Beach S.R.H. Forgiveness in marriage: Current status and future directions. Family Relations. 2006;55(4):415–427. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3729.2005.callf.x-i1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gage A.J. Child marriage prevention in Amhara region, Ethiopia: Association of communication exposure and social influence with parents/guardians’ knowledge and attitudes. Social Science & Medicine. 2013;97:124–133. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh R., Dubey M.J., Chatterjee S., Dubey S. Impact of COVID -19 on children: Special focus on the psychosocial aspect. Minerva Pediatrica. 2020;72(3) doi: 10.23736/S0026-4946.20.05887-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groenewald T. A phenomenological research design illustrated. International Journal of Qualitative Methods. 2004;3(1):42–55. doi: 10.1177/160940690400300104. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta S., Jawanda M.K. The impacts of COVID-19 on children. Acta Paediatrica. 2020;109(11):2181–2183. doi: 10.1111/apa.15484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Himawan K.K. Either I do or I must: An exploration of the marriage attitudes of Indonesian singles. The Social Science Journal. 2019;56(2):220–227. doi: 10.1016/j.soscij.2018.07.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hull T.H. Contemporary demographic transformations in China, India and Indonesia. Springer; 2016. Indonesia’s fertility levels, trends and determinants: Dilemmas of analysis; pp. 133–151. [Google Scholar]

- Imtoual A., Hussein S. Challenging the myth of the happy celibate: Muslim women negotiating contemporary relationships. Contemporary Islam. 2009;3(1):25–39. doi: 10.1007/s11562-008-0075-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Johansen S.v.L. Colorado State University; 2014. Sensation seeking and impulsivity in relation to youth decision making about risk behavior: Mindfulness training to improve self-regulatory skills. [Google Scholar]

- Johnston L.G., Sabin K. Sampling hard-to-reach populations with respondent driven sampling. Methodological Innovations Online. 2010;5(2):38–48. doi: 10.4256/mio.2010.0017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jones G.W. Which Indonesian women marry youngest, and why? Journal of Southeast Asian Studies. 2001;32(1):67–78. doi: 10.1017/S0022463401000029. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kasjim K. Abuse of Islamic law and child marriage in South-Sulawesi Indonesia. Al-Jami’ah: Journal of Islamic Studies. 2016;54(1):95. doi: 10.14421/ajis.2016.541.95-121. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kerry-Moran, K. J., & Aerila, J.-A. (2019). Introduction: The stregnth of stories. In K. J. Kerry-Moran & J.-A. Aerila (Eds.), Story in Children's lives: Contributions of the narrative mode to early childhood development, literacy, and learning (1st ed., pp. 1–8). Cham, Switzerland: Springer Nature Switzerland AG.

- Khanom K., Islam Laskar B. Causes and consequences of child marriage – A study of Milannagar Shantipur Village in Goalpara District. International Journal of Interdisciplinary Research in Science Society and Culture(IJIRSSC) 2015;1(2):2395–4335. [Google Scholar]

- Kim J., Prskawetz A. External shocks, household consumption and fertility in Indonesia. Population Research and Policy Review. 2010;29(4):503–526. [Google Scholar]

- Kirchherr J., Charles K. Enhancing the sample diversity of snowball samples: Recommendations from a research project on anti-dam movements in Southeast Asia. PLoS One. 2018;13(8) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0201710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kofman Y.B., Garfin D.R. Home is not always a haven: The domestic violence crisis amid the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychological Trauma Theory Research Practice and Policy. 2020;12(S1:S199–S201. doi: 10.1037/tra0000866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumala Dewi L.P.R., Dartanto T. Natural disasters and girls vulnerability: Is child marriage a coping strategy of economic shocks in Indonesia? Vulnerable Children and Youth Studies. 2019;14(1):24–35. doi: 10.1080/17450128.2018.1546025. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kumparan . Kumparan; 2018. Tren Nikah Muda dan Upaya Menyetop Perkawinan Anak [youth marriage trends and efforts to stop child marriage] [Google Scholar]

- MacDermott A.F.N. Living with angina pectoris - A phenomenological study. European Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing. 2002 doi: 10.1016/S1474-5151(02)00047-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahase E. Covid-19: EU states report 60% rise in emergency calls about domestic violence. BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.) 2020;369(May):m1872. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahato S.K. Causes and consequences of child marriage: A perspective. International Journal of Scientific and Engineering Research. 2016;7(7):698–702. doi: 10.14299/ijser.2016.07.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Miles, M. B., Huberman, M. a, & Saldana, J. (2014). Drawing and Verying conclusions. Qualitative Data Analysis: A Methods Sourcebook. doi:January 11, 2016.

- Morgan D.L. Snowball sampling. The SAGE Encyclopedia of Qualitative Research Methods. 2008;2:815–816. [Google Scholar]

- Mutawali Moderate islam in lombok the dialectic between islam and local culture. Journal of Indonesian Islam. 2016;10(2):309–334. doi: 10.15642/JIIS.2016.10.2.309-334. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Myers D.G. Well-being: The foundations of hedonic psychology. 1999. Close relationships and quality of life. [Google Scholar]

- Nasrullah M., Zakar R., Zakar M.Z. Child marriage and its associations with controlling behaviors and spousal violence against adolescent and young women in Pakistan. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2014;55(6):804–809. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2014.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neubauer B.E., Witkop C.T., Varpio L. How phenomenology can help us learn from the experiences of others. Perspectives on Medical Education. 2019;8(2):90–97. doi: 10.1007/s40037-019-0509-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nigam S. COVID-19: India’s response to domestic violence needs rethinking. SSRN Electronic Journal. 2020 doi: 10.2139/ssrn.3598999. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nour, N. M. (2009). Child marriage: A silent health and human rights issue. Reviews in Obstetrics & Gynecology, 2(1), 51–56. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19399295. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Nursyamsi M. Republika; 2016, October 10. Pernikahan Dini di NTB Tinggi [The High Number of Child Marriage in NTB]https://republika.co.id/berita/nasional/daerah/16/10/10/oetvaw366-pernikahan-dini-di-ntb-tinggi [Google Scholar]

- O’Leary K.D., Malone J., Tyree A. Physical aggression in early marriage: Prerelationship and relationship effects. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1994;62(3):594–602. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.62.3.594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olweus D., Mattsson A., Schalling D., Loew H. Circulating testosterone levels and aggression in adolescent males: A causal analysis. Psychosomatic Medicine. 1988;50(3):261–272. doi: 10.1097/00006842-198805000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patton M.Q. Qualitative evaluation and research methods. Sage; Thousand Oaks, CA: 1990. Designing qualitative studies. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Paul P., Mondal D. Child marriage in India: A human rights violation during the COVID-19 pandemic. Asia-Pacific Journal of Public Health. 2020 doi: 10.1177/1010539520975292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petroni S., Steinhaus M., Fenn N.S., Stoebenau K., Gregowski A. New findings on child marriage in sub-Saharan Africa. Annals of Global Health. 2017;83(5):781–790. doi: 10.1016/j.aogh.2017.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plan International Plan Indonesia Libatkan Remaja Mataram dan Lombok Utara [Plan Indonesia involves adolescents in Mataram and Lombok Utara in ther program] 2020. https://plan-international.or.id/en/plan-indonesia-libatkan-remaja-mataram-dan-lombok-utara/ Retrieved February 17, 2021, from Plan International website:

- Raj A. When the mother is a child: The impact of child marriage on the health and human rights of girls. Archives of Disease in Childhood. 2010;95(11):931–935. doi: 10.1136/adc.2009.178707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raj A., Saggurti N., Balaiah D., Silverman J.G. Prevalence of child marriage and its effect on fertility and fertility-control outcomes of young women in India: A cross-sectional, observational study. The Lancet. 2009;373(9678):1883–1889. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60246-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramaswamy, S., & Seshadri, S. (2020). Children on the brink: Risks for child protection, sexual abuse, and related mental health problems in the COVID-19 pandemic. Indian Journal of Psychiatry, 62(Suppl 3), S404–S413. doi: 10.4103/psychiatry.IndianJPsychiatry_1032_20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Road H., Estate R.H. Violence against women and children: COVID 19 a telephone survey: Initiative of Manusher Jonno foundation survey period. 2020. http://www.manusherjonno.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/FinalReportofTelephoneSurveyonVAWMay2020-9June.pdf May 2020. (May). Retrieved from.

- Roesch E., Amin A., Gupta J., Garcia-Moreno C. Violence against women during covid-19 pandemic restrictions. BMJ. 2020;369 doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saldaña J. Sage; 2016. The coding manual for qualitative researchers (No. 14) [Google Scholar]

- Sarfo E.A., Salifu Yendork J., Naidoo A.V. Child Care in Practice. 2020. Understanding child marriage in Ghana: The constructions of gender and sexuality and implications for married girls; pp. 1–14. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Save the Children. (2020). Covid-19 places half a million more girls at risk of child marriage in 2020. Retrieved from https://www.savethechildren.net/news/covid-19-places-half-million-more-girls-risk-child-marriage-2020.

- Schlecht J., Rowley E., Babirye J. Early relationships and marriage in conflict and post-conflict settings: Vulnerability of youth in Uganda. Reproductive Health Matters. 2013;21(41):234–242. doi: 10.1016/S0968-8080(13)41710-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schumacher J.A., Leonard K.E. Husbands’ and Wives’ marital adjustment, verbal aggression, and physical aggression as longitudinal predictors of physical aggression in early marriage. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2005;73(1):28–37. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.73.1.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaghaghi A., Bhopal R.S., Sheikh A. Approaches to recruiting “hard-to-reach” populations into re-search: A review of the literature. Health Promotion Perspective. 2011;1(2):86–94. doi: 10.5681/hpp.2011.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sifat R.I. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on domestic violence in Bangladesh. Asian Journal of Psychiatry. 2020;53 doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith-Hefner N.J. The new muslim romance: Changing patterns of courtship and marriage among educated javanese youth. Journal of Southeast Asian Studies. 2005;36(3):441–459. doi: 10.1017/S002246340500024X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Speizer I.S., Pearson E. Association between early marriage and intimate partner violence in India: A focus on youth from Bihar and Rajasthan. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2010;26(10):1963–1981. doi: 10.1177/0886260510372947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stutzer A., Frey B.S. Does marriage make people happy, or do happy people get married? The Journal of Socio-Economics. 2006;35(2):326–347. doi: 10.1016/j.socec.2005.11.043. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Swain K. Coping with more than COVID-19. The Lancet Child & Adolescent Health. 2020;4(11):806. doi: 10.1016/S2352-4642(20)30322-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teherani A., Martimianakis T., Stenfors-Hayes T., Wadhwa A., Varpio L. Choosing a qualitative research approach. Journal of Graduate Medical Education. 2015;7(4):669–670. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-15-00414.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tenkorang E.Y. Explaining the links between child marriage and intimate partner violence: Evidence from Ghana. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2019;89:48–57. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2019.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- UNFPA-UNICEF. (2020). Child marriage in COVID-19 contexts: Disruptions, alternative approaches and building Programme resilience. 1–12. Retrieved from https://esaro.unfpa.org/sites/default/files/pub-pdf/child_marriage_in_covid-19_contexts_final.pdf.

- UNICEF Saying no to child marriage in Indonesia. 2019. https://www.unicef.org/indonesia/stories/saying-no-child-marriage-indonesia Retrieved February 5, 2021, from Unicef website:

- UNICEF (2020). COVID-19: Children in Indonesia at risk of lifelong consequences.

- United Nations Population Fund; Avenir Health, J. H. U. V. U. (Australia) UNFPA New York; 2020. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on family planning and ending gender-based violence, female genital mutilation and child marriage. [Google Scholar]

- Vora M., Malathesh B.C., Das S., Chatterjee S.S. COVID-19 and domestic violence against women. Asian Journal of Psychiatry. 2020;53 doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waters J. Snowball sampling: A cautionary tale involving a study of older drug users. International Journal of Social Research Methodology. 2015;18(4):367–380. doi: 10.1080/13645579.2014.953316. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wellman J.C., Krueger S.J. 2nd ed. International Thompson; Johansburg, South Africa: 2002. Research methodology for the business and administrative sciences. [Google Scholar]

- Wijaya C. BBC News Indonesia; 2020, August 25. Covid-19: “Ratusan kasus pernikahan anak terjadi selama pandemi”, orang tua “menyesal sekali” dan berharap “anak kembali sekolah”. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank Group Summary of key messages. Gender Dimensions of the COVID-19 Pandemic. 2020;18(April):964–969. http://pubdocs.worldbank.org/en/232551485539744935/WDR17-BP-Gender-based-violence-and-the-law.pdf%0Awww.adelaide.edu.au/writingcentre/%0Awww.iucn.org Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]