Abstract

By bridging theoretical perspectives from diverse disciplines including public relations, organizational communication, psychology, and management, this study advances a sequential mediation process model that links leaders’ motivational communication—specifically, direction-giving, empathetic, and meaning-making language—to employees’ organizational engagement during times of crisis. The model incorporates employees’ psychological needs satisfaction and their subsequent crisis coping strategies so as to explain the process that underlies the effects of leader communication on employee engagement. We tested the model in a unique yet underexplored crisis context: organizational crises triggered by the global pandemic of COVID-19. The results of an online survey of 490 full-time U.S. employees provide strong support to the model’s predictions. Our research extends internal crisis communication scholarship in public relations by addressing what types of leader communication strategies as well as how these strategies contribute to employee engagement in a holistic fashion. It also advances theoretical development of the motivational language theory, self-determination theory, transactional model of stress and coping, and organizational engagement—the four theoretical bases of our study—in the context of organizational crises. Lastly, the study results provide timely practical insights on effective internal crisis communication.

Keywords: Leader communication, Motivational language, Psychological needs satisfaction, Crisis coping, Organizational engagement

1. Introduction

Organizational crises are adverse events that occur suddenly and unexpectedly to an organization (Coombs, 2019). Viewed by managers and stakeholders as highly relevant and potentially disruptive, organization crises can threaten an organization’s goals, impose physical, emotional, and financial sufferings on its stakeholders, and bring profound implications for the organization’s reputation and relationships with its stakeholders (Coombs, 2019). Given these implications, public relations researchers have made considerable efforts to identify the antecedents, processes, and outcomes of effective crisis communication (e.g., Jin, Pang, & Cameron, 2012; Liu & Fraustino, 2014; Ulmer, Sellnow, & Seeger, 2017). Among this burgeoning body of literature, two key perspectives have emerged in guiding researchers’ contributions: the internal perspective that focuses on crisis dynamics within an organization and the external perspective that centers on managing the responses of stakeholders outside the organization (Bundy, Pfarrer, Short, & Coombs, 2017).

While both perspectives are essential, more attention has been disproportionately given to protecting and restoring organizational reputation, relationships, and performance with external stakeholders through crisis response strategies (e.g., Grappi & Romani, 2015; Tao, 2018; Tao & Song, 2020). The internal perspective of crisis communication, specifically communication with employees, has been inadequately examined (Kim, 2020). This imbalanced distribution of research attention is problematic. Employees are of paramount importance to the success of an organization’s crisis communication and management because they play a strategic role in helping the organization build resilience and mitigate negativity by implementing positive adaptive behaviors, engaging in creative and positive crisis communication (Lee, 2019), and sustaining work-role performance (Kim, 2020). Given the strategic role of employees, a critical objective of organizations’ crisis communication is to cultivate a motivated and engaged workforce despite adversities (Kim, 2018). This objective, however, is challenging to reach as employee engagement becomes particularly fragile during times of crisis, when their work environment is laden with uncertainty and their psychological contract with the organization is threatened or broken owing to crisis-induced organizational changes, such as downsizing, layoffs, or benefit reduction (Lee, Tao, Li, & Sun, 2021).

To address the research gap and to enhance organizations’ internal crisis communication practice, we examine how leaders’ motivational communication can facilitate employees’ crisis coping and promote their organizational engagement. We focus on leader communication because of its “extensive and pervasive role in organizations” (Mayfield, Mayfield, & Neck, 2021, p. 3). Leader communication has been repeatedly evidenced to impact employees’ perceptions, emotions, and behaviors (e.g., Men, Qin, and Jin, 2021). Particularly in crisis settings, crisis leadership and its communication have been considered as the core of effective internal crisis management (Bundy et al., 2017). Nevertheless, relatively limited insights have been provided by public relations scholars on how different forms of leader-employee discourse influence employees’ organizational engagement during crises and what the underlying mechanism driving such influence is.

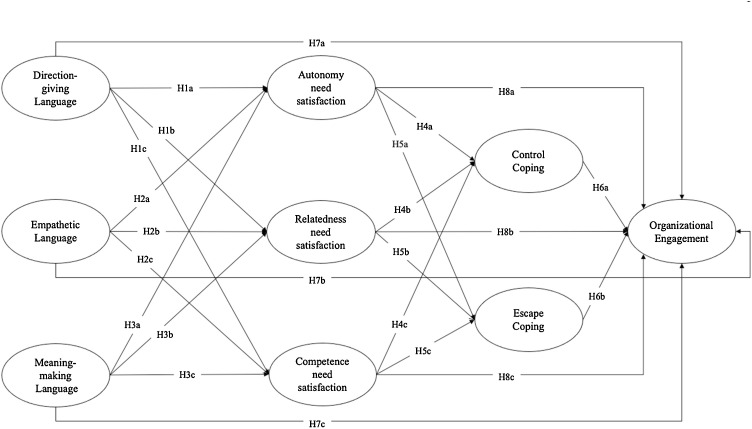

Integrating insights from motivational language theory (MLT) in organization communication, self-determination theory (SDT) and transactional model of stress and coping in psychology, and organizational engagement literature in public relations and management, we theorize a sequential mediation process model to shed light on how three primary forms of leader communication—direction-giving, empathetic, and meaning-making—drive employee engagement by satisfying their basic psychological needs and encouraging their proactive crisis coping (see Fig. 1 ). These four theoretical frameworks—MLT, SDT, the transactional model, and organization engagement—have been applied to the work context to increase our understanding of employees and workplace (e.g., Deci, Olafsen, & Ryan, 2017; Mayfield et al., 2021; Van den Brande, Baillien, Elst, De Witte, & Godderis, 2020). Yet, they are often used in different work domains that are not crisis oriented. This occurs despite the four theoretical frameworks’ shared underpinnings on employee motivation. Thus, we integrate these previously less connected perspectives and develop a relatively holistic model that delineates different stages (i.e., psychological needs satisfaction and effective crisis coping) in the motivational effects of leader communication on employee engagement.

Fig. 1.

The proposal conceptual framework.

Our conceptual model was tested and largely supported by an online survey of 490 full-time U.S. employees in April 2020 with the COVID-19 outbreak as its context. The selection of this context is purposeful. Organizational crises are related to different contexts, such as natural disasters, workplace discrimination, product defects, malicious rumors, management misdeed, and environmental damage (Coombs, 2019). However, differing from these traditionally studied crisis contexts, organizational crises triggered by a global pandemic tend to be more complicated, less controllable, and difficult to manage (Cortez & Johnston, 2020). This can be primarily attributed to the rare occurrence, high unpredictability, and wide-spread severe impact of the pandemic (Cortez & Johnston, 2020). By focusing on this unique yet underexplored crisis context, our study provides much needed theoretical and practical insights into effective internal communication that helps combat such crises.

2. Literature review

2.1. Leaders’ internal communication during crises: motivating language theory

Originally conceptualized by Sullivan (1988), motivational language theory (MLT) presents a linguistic framework to enhance employee motivation by leaders’ strategic use of speech. It describes three basic forms of motivational language that comprise most leader-employee discourse: direction-giving, empathetic, and meaning-making (Mayfield, Mayfield, & Sharbrough, 2015). When leaders coordinate their use of this full spectrum of motivational language and align their behavioral consistency with these speech acts, motivational language is expected to yield its optimal effectiveness in creating desirable psychological and behavioral outcomes among employees (Mayfield et al., 2015). For example, through conducting an online survey among 668 U.S. employees, Mayfield et al. (2021) show that a leader’s motivating language positively contributes to employees’ self-leadership, job performance, job satisfaction, and intent-to-stay (i.e., the path weights from motivating language to these four outcomes are all larger than .10 and significant at the p < .05 level).

Specifically, direction-giving language has been documented as the most frequently used form of leader language (Mayfield & Mayfield, 2018). It dispels ambiguity by transparently informing employees of work requirements, procedures, and resources. It clearly explains role expectations and reward allocation to employees and constructively provides them with performance feedback. Similar to other MLT dimensions, direction-giving language should not be interpreted as voicing commands or delivering monologues (Mayfield & Mayfield, 2018). Instead, it is a linguistic strategy for leaders to initiate respectful inquiry, engage in dialogue, and respond to concerns (Van Quaquebeke & Felps, 2018). This is particularly the case during the process when leaders set task goals, delegate authority, and share work feedback with employees (Guo & Ling, 2019).

Different from direction-giving language, empathic language has been reported as least frequently used in leader-employee discourse (Yue, Men, & Ferguson, 2021). It is, however, considered crucial to enhancing employee job satisfaction and engagement (Dutton & Spreitzer, 2014). Empathy represents civility, compassion, perspective taking, and emotional bonding (Schoofs, Claeys, De Waele, & Cauberghe, 2019). Thus, leaders’ use of emphatic language expresses their humanity, sensitivity, and care toward followers (Mayfield & Mayfield, 2018). Empathic language takes place when leaders praise employees for their efforts and initiatives, encourage workers who encounter setbacks and challenges, acknowledge employees’ thoughts and feelings in a non-judgmental way, and express respect for employees’ personal choices and goals (Sun, Pan, & Ho, 2016).

As the third dimension of MLT, meaning making language assists employees in finding meanings at work (Holmes & Parker, 2019). It transmits cultural norms and unwritten behavioral expectations at the workplace; it communicates organizational identity, purposes, and values (Mayfield & Mayfield, 2016). Meaning making language is responsible for cultivating organizational culture (Holmes & Parker, 2019). It occurs when leaders use stories, examples, and metaphors to construct cognitive schema in the mind of employees as to how “people do things here” and how/why “I fit in here” (Guo & Ling, 2019). Meaning making language inspires employees as it paints the big picture of how each employee’s unique talents and values advance the goals of the organization and/or the larger society (Yue et al., 2021).

The MLT is appropriate to our research goals. This is not only because of its well-established generalizability across multiple organizational, industrial, and cultural settings (Mayfield & Mayfield, 2018), but more importantly due to its pivotal role in internal crisis communication. To elaborate, leaders’ direction-giving language that emphasizes transparency, vision articulation, task explanation, and employees’ directed concerns must occur to reduce uncertainty and anxiety among employees (Mazzei & Ravazzani, 2015). Attentive listening and constructive feedback should also take place to facilitate employees’ crisis coping (Ulmer et al., 2017). Meanwhile, leaders’ use of empathic language is not only desired but also required to ease crisis-inflicted stress at the workplace (Coombs, 2019). When leaders display their care, compassion, and respect to employees, employee morale can be restored (Ulmer et al., 2017). Furthermore, crises impose adaptive challenges on an organization and its employees, especially in terms of organizational transition and job-related changes (Kim, 2020). Such changes accelerate employees’ need for sense making (Weick, 1995). To meet employees’ need for meaning, leader communication should assume a greater role in sense making (Mayfield & Mayfield, 2018).

Despite the MLT’s importance in enlightening the practice of effective leader communication during crises, limited empirical efforts have been undertaken to understand its impact on employee reactions. In particular, little is known regarding how the three distinct yet related forms of motivational language separately influence employees’ psychological needs satisfaction and subsequent crisis coping. To fill the gap, we draw insights from self-determination theory to conceptualize the dimensional effect of leaders’ motivational language on enhancing employees’ psychological responses to crises.

2.2. Employees’ psychological needs satisfaction: self-determination theory

An examination of MLT’s potential relationships with self-determination theory (SDT) is a logical step since leader communication represents an understudied external influence of employees’ needs satisfaction during times of crisis. The two theories complement each other because both are linked with intersecting outcomes such as job satisfaction, organizational commitment, and work performance (e.g., Deci et al., 2017; Mayfield & Mayfield, 2018). More importantly, both theories emphasize employees’ motivational states and suggest sources for improving intrinsic employee motivation, which will be further explained in this section.

As a meta-theory of motivation, SDT (Ryan & Deci, 2000) posits that human beings' optimal functioning depends on the satisfaction of three basic universal psychological needs: needs for autonomy, competence, and relatedness. These three needs are as essential to our psychological well-being as food and water to our physical health (Ryan & Deci, 2000). Autonomy requires the experience of “choice and volition in one’s behaviour and to the personal authentic endorsement of one’s activities and actions” (Milyavskaya & Koestner, 2011, p. 387). Relatedness involves a sense of connection, caring, and mutual reliance with others (Tao, Song, Ferguson, & Kochhar, 2018). Competence refers to the feeling of being effective in one’s efforts and being capable of achieving desired outcomes (Tao & Ji, 2020). Decades of SDT research have consistently shown that satisfying the three needs is fundamental to enhancing intrinsic motivation, driving positive behaviors, and achieving well-being (Deci et al., 2017).

Furthermore, SDT points out that the degree of one’s needs satisfaction mainly depends on the social or structural aspects of one’s surroundings (De Cooman, Stynen, Van den Broeck, Sels, & De Witte, 2013). Hence, SDT researchers in the work domain have focused on how various workplace factors (e.g., work climate, job characteristics, and reward contingencies) contribute to employees’ needs satisfaction, which in turn further generates desirable outcomes including employees’ proactivity and vitality, innovative work behavior, and positive relationships with the organization (see Deci et al., 2017 for a review). Adding to this stream of research, we propose that leaders’ motivational language is also one of those contextual factors that enhance employees’ needs satisfaction, particularly during times of crisis.

2.2.1. Leaders’ motivational language and employees’ needs satisfaction during crises

Despite SDT’s successful application in a wide range of domains, it has rarely been examined in the context of organizational crisis. Extending the theory’s insights to the crisis context is much needed since organizational crises tend to frustrate employees’ needs satisfaction by inflicting physical, psychological, and financial harms on organizational employees. Therefore, it is of great practical importance to examine how the organization can restore employees’ needs satisfaction through ways such as effective leader communication.

We propose that each dimension of MLT enhances employees’ satisfaction for the autonomy, relatedness, and competence needs. First, direction-giving language clearly outlines delegated authority for employees to make work decisions independently (Mayfield & Mayfield, 2018). It transparently shares organizational goals and processes, which encourages employees’ personal goal setting and decision making (Mayfield et al., 2021). As such, direction-giving language gives employees clarity to make conscious choices and thereby increases their perceived autonomy. Second, like other MLT dimensions, direction-giving language draws from interpersonal connections and managerial responsibility for attentive listening and respectful inquiry (Mayfield & Mayfield, 2018). As Van Quaquebeke and Felps (2018) explained, attentive listening implies “I care about you personally” while respectful inquiry “opens the communication to dyadic contributions, thereby communicating ‘We are in this together.’” (p. 12). Thus, direction-giving language contributes to the fulfillment of employees’ need for relatedness. Third, role ambiguity and misinterpretation about expectations prevent employees from being effective in their work (Holmes & Parker, 2019). Such a situation occurs frequently during times of crisis when the work environment is full of uncertainty and unpleasant changes. Leaders’ direction-giving language enables employees to clearly understand their role, priorities, and work expectations (Sun et al., 2016). As a result, employees are better equipped to overcome challenges and accomplish their goals, which helps to satisfy their need for competence. Thus, we propose:

H1

Leaders’ direction-giving language is positively associated with employees’ satisfaction of (a) autonomy, (b) relatedness, and (c) competence needs during a crisis.

Regarding empathetic language, this speech act—via perspective taking and expressions of care—reflects leaders’ understanding of and respect for employees’ personal perspectives, choices, and goals, which affirms employees’ role as autonomous agents at the workplace (J. Mayfield et al., 2021). Furthermore, this form of talk enables leaders to bond with employees through emotional and verbal cues, which is particularly evident during turbulent times (Kock, Mayfield, Mayfield, Sexton, & De La Garza, 2019). It helps to cultivate upbeat interpersonal connections within an organization, therefore working as a positive reinforcement for employees’ sense of belonging and relatedness when facing crises (Mayfield & Mayfield, 2018). Finally, empathetic language contains genuine praise and encouragement of employees for their work efforts, thus increasing their perceived competence (Yue et al., 2021). Synthesizing these insights, we posit:

H2

Leaders’ empathetic language is positively associated with employees’ satisfaction of (a) autonomy, (b) relatedness, and (c) competence needs during a crisis.

Meaning-making language is a form of leader communication, which fosters employee cultural sense-making by articulating how employees’ personal desires and decisions are connected with larger organizational goals, thus encouraging them to be agentic when exploring their potential to contribute to the organization (Mayfield et al., 2021). As such, meaning-making language can fulfill employees’ need for autonomy. Second, meaning-making language satisfies employees’ need for relatedness. To elaborate, work meaning is constructed, transmitted, decoded, and evaluated through social cues that are imbued in interpersonal interactions with peer colleagues, subordinates, and superordinates (Dutton, Roberts, & Bednar, 2010). Leaders’ meaning-making language facilitates employees’ request for and processing of work meaning via attentive communication (Mayfield & Mayfield, 2018). Such language helps employees to place themselves in the broader network of the organization and to understand their relational role with respect to other employees in the organization, which enhances their perceived relatedness (Mayfield & Mayfield, 2018). Third, meaning-making language entails leaders’ expressions of how individual employees’ roles and performance contribute to higher organizational purposes and/or societal well-being (Yue et al., 2021). Such affirmative and inspirational words help satisfy employees’ need for competence, as they validate employees’ sense of efficacy in making a difference (Walumbwa & Hartnell, 2011). In brief, we predict:

H3

Leaders’ meaning-making language is positively associated with employees’ satisfaction of (a) autonomy, (b) relatedness, and (c) competence needs during a crisis.

2.3. Employees’ crisis coping strategies: the transaction model of stress and coping

This study not only advances internal crisis communication literature by unpacking the nuanced, dimensional effect of MLT on employees’ needs satisfaction. It also enriches the body of literature through bridging the theories of MLT and SDT with employee coping research—particularly, the transaction model of stress and coping (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984). By examining how employees’ needs satisfaction, fostered via leaders’ motivational language, further determines employees’ coping strategies, we provide crisis and organizational researchers with a new pathway to understand employees’ psychological experiences during turbulent times.

A broad, integrative, and well-acknowledged definition of coping comes from Lazarus and Folkman’s (1984) transaction model of stress and coping. As the leading theory for understanding coping with stressful events like organizational crises, the transaction model defines coping as “the person’s cognitive and behavioral efforts to manage (reduce, minimize, or tolerate) the internal and external demands of the person-environment transaction that is appraised as taxing or exceeding the person’s resources” (Folkman, Lazarus, Dunkel-Schetter, DeLongis, & Gruen, 1986, p. 572). Furthermore, the transaction model parsimoniously classifies coping strategies into two major types: problem-solving focused and emotion-regulating focused (Lazarus, 1990). Applying this typology to the work domain, Latack (1986) proposes control coping and escape coping. Control coping consists of cognitive and behavioral strategies that are “proactive, take-charge in tone” (Latack, 1986, p. 378). Examples include employees’ motivated efforts to approach the problem, generating plans and solutions, and acting to reduce or eliminate the source of stress (Fugate, Kinicki, & Prussia, 2008). In contrast, escape coping consists of cognitive and behavioral strategies that “suggest an escapist, avoidance mode” (Latack, 1986, p. 378). Examples include employees trying not to think about the problem or trying to admit that there is nothing they can do to solve the problem (Li, Sun, Tao, & Lee, 2021). Although people can use both coping strategies to deal with a stressful encounter, the predominant view in coping literature is that control coping generally works better than escape coping (Jin, 2010).

2.3.1. Employees’ needs satisfaction and crisis coping

According to the transactional model, it is the dynamic interplay between a person and his/her environment that creates perceived stress for the person (Lazarus & Folkman, 1987). In other words, personal characteristics (e.g., goals, mastery, and internal locus of control) and environmental factors (e.g., constraints, demands, resources such as social support networks) collectively affect the person’s cognitive appraisals on stressful encounters (Lazarus & Folkman, 1987). Two types of cognitive appraisal are central to the transactional model: primary and secondary appraisal (Bliese, Edwards, & Sonnentag, 2017). An individual’s primary appraisal is concerned with whether the encounter is personally relevant and is considered harmful, threatening, or challenging. One’s secondary appraisal deals with the question of personal control over the encounter—whether anything can be done to change situations perceived to be undesirable. This secondary appraisal of personal control, coupled with the primary appraisal, requires the individual to evaluate personal and environmental factors as well as the person-environmental relationship so as to select appropriate coping strategies to alter the stressful situations (Lazarus & Folkman, 1987).

Applying these insights to the present context, we propose that employees’ needs satisfaction serves as a type of intrapersonal coping resources (i.e., a personal factor), which impacts their secondary appraisal of organizational crises and informs their subsequent adoption of coping strategies (Yeung, Lu, Wong, & Huynh, 2016). When employees feel autonomous, competent, and connected with their social environment during a crisis, they are more likely to appraise the crisis as challenges that can be controlled and overcome (Yeung et al., 2016). They are less likely to evaluate the crisis as threats or damages that may inevitably undermine their well-being (Yeung et al., 2016). Such crisis appraisal, highlighting the confidence in personal control over the stressful situation, tends to motivate employees to adopt control coping instead of escape coping (Ben-Zur, 2019). In contrast, if the three fundamental psychological needs are thwarted, employees may perceive a lack of control, helplessness, and alienation (Ntoumanis, Edmunds, & Duda, 2009). As a result, they may choose escape coping to withdraw from the problem and regulate emotional distress (Ben-Zur, 2019).

To date, very limited empirical studies have examined the relationship between needs satisfaction and coping strategies. Among the handful of studies that tap into this topic, empirical evidence has been largely generated in the context of public health focusing on patient experiences rather than in the setting of internal organizational crises highlighting employees’ experiences. For example, Yeung et al. (2016) analyze survey responses from 454 college students who have experienced traumatic events and find that satisfaction of the three basic needs—autonomy, relatedness, and competence—is positively and significantly related to active, control coping at the p < .05 level. Similarly, Ataşalar and Michou (2019) survey 165 adolescent students to examine their pathological Internet use for coping. They note that the three needs satisfaction is positively associated with these students’ control coping while negatively associated with their escape coping (i.e., these relationships are all significant at the p < .05 level). Extending the prior studies’ insights to the internal organizational crisis context, we propose:

H4

Employees’ satisfaction of (a) autonomy, (b) relatedness, and (c) competence needs is positively associated with control coping during a crisis.

H5

Employees’ satisfaction of (a) autonomy, (b) relatedness, and (c) competence needs is negatively associated with escape coping during a crisis.

2.4. Organizational engagement: the key outcome of employees’ crisis coping

We select organizational engagement as the outcome variable of our framework for its importance in public relations research and practice (Lemon & Palenchar, 2018; Shen & Jiang, 2019). Organizational engagement has been of perennial interest to organizations because of its direct link to employees’ organizational commitment (Verčič & Vokić, 2017), organizational citizenship behavior (Matta, Scott, Koopman, & Conlon, 2015), job satisfaction (Meng & Berger, 2019), task performance (Shen & Jiang, 2019), and lowered intention to quit (Akingbola & van den Berg, 2019), to name a few. Its critical role to organizations’ survival becomes particularly evident in times of crisis as organizations are clamoring to figure out how to strengthen their connection with employees and secure employees’ role performance (Mahon, Taylor, & Boyatzis, 2014).

To date, scholarly debate on what constitutes engagement still continues, but a majority of researchers subscribe to Kahn’s (1990) definition, which denotes personal engagement as “the harnessing of organizational members’ selves to their work roles; in engagement, people employ and express themselves physically, cognitively, and emotionally during role performance” (p. 694). Building upon Kahn’s (1990) definition, Saks (2006) extends the concept of engagement to organizations and proposes organizational engagement as “a distinct and unique construct consisting of cognitive, emotional, and behavioral components that are associated with individual role performance” as a member of the organization (p. 602). Following Kahn’s (1990) and Saks (2006)’s conceptualizations, Welch (2011) introduces organizational engagement to public relations literature and defines it as “a dynamic, changeable psychological state which links employees to their organizations, manifest in employee role performances expressed physically, cognitively and emotionally, and influenced by organization level internal communication” (p. 341).

2.4.1. Employees’ crisis coping and organizational engagement

Given the apparent desirability of having an engaged workforce, organizational and communication researchers have made considerable efforts to identify various antecedents that enhance or diminish employees’ engagement levels with their organizations. These antecedents ranged from individual-related factors (e.g., value congruence) to job (e.g., job demands), team (e.g., colleague-level support), and organization-related (e.g., organizational communication) factors (see Bailey, Madden, Alfes, & Fletcher, 2017 for a review). Adding to this stream of research, we suggest another individual-level antecedent to organizational engagement during times of crisis—employees’ coping strategies. Specifically, control coping implies a level of confidence, energy, and optimism on the part of the employee to identify the sources of stress, initiate planned efforts to eliminate these sources, and seek positive changes (Srivastava & Tang, 2015). As such, control coping has been repeatedly found to bring an array of beneficial outcomes. For instance, through a survey among 2764 Finnish employees, Cheng, Mauno, and Lee (2014) show that control coping contributes to employees’ work engagement as well as their emotional energy at work and at home (i.e., the regression coefficients from control coping to the three outcomes are all larger than .05 and significant at the p < .05 level). Additionally, through a survey among 314 hospital employees in Taiwan, Chang and Edwards (2015) observe that control coping helps to promote job satisfaction (i.e., the relationship is significant at the p < .01 level). Furthermore, Srivastava and Tang’s (2015) survey among 452 U.S. salespeople reveals that control coping tends to increase organizational commitment (i.e., the relationship is significant at the p < .01 level). Particularly relevant to the current study, control coping has been evidenced to lower employee burnout—the antithesis of employee engagement (Crawford, LePine, & Rich, 2010). Accordingly, we expect control coping to be positively associated with organizational engagement during times of crisis.

On the other hand, escape coping entails employees’ passive attempts to avoid, minimize, or disengage from the stressful situation and its sources (Solove, Fisher, & Kraiger, 2015). This strategy may help to temporarily ease the emotional distress caused by the stressor but may prevent employees from performing a suitable action to remove or alter the stressor. Hence, escape coping has been shown to result in negative outcomes. For example, after conducting a survey among 177 workers in a mental hospital, Leiter (1991) concludes that escape coping results in higher burnout characterized by emotional exhaustion and weakens employees’ feeling of personal accomplishment (i.e., path weights: .13 and -.12 respectively; significant at the p < .05 level). Similarly, through a two-wave survey among 482 employees, Van den Brande et al. (2017) find that escape coping amplifies the relationship between employees’ role conflict and workplace bullying (significant at the p < .05 level). Additionally, Cheng et al.’s (2014) survey among 2764 Finnish employees shows that escape coping lowers work engagement, and reduces employees’ emotional energy as well as their marital satisfaction (i.e., the regression coefficients from escape coping to these outcomes are all significant at the p < .001 level, ranging from -.13 to -.17). In view of such evidence, we propose a negative association between escape coping and organizational engagement.

H6

(a) Employees’ control coping is positively associated with organizational engagement, while (b) employees’ escape coping is negatively associated with organizational engagement during a crisis.

Lastly, we suggest that leaders’ motivational language and employees’ needs satisfaction are also directly associated with organizational engagement. MLT literature has shown that direction-giving, empathetic, and meaning-making leader communication promotes desirable outcomes that are conceptually close to organizational engagement (e.g., organizational identification and citizenship behavior; Mayfield & Mayfield, 2019). For example, Yue et al., 2021 survey 482 U.S. employees and find that the three forms of motivational language together promote positive emotional culture at workplace and subsequently enhance employees’ organizational identification (i.e., the path weights from motivational language to the aforesaid two outcomes are at or above .60 and significant at the p < .001 level). Additionally, Sun et al. (2016) survey 277 employees at airline and army organizations in Taiwan and show that motivational language leads to increased organizational citizenship behavior (i.e., the relationship is significant at p < .001 level). Furthermore, SDT research has demonstrated the critical role of needs satisfaction as a motivational fuel that propels employee engagement (Gagné, 2014). For instance, through an online experiment among 190 German-speaking employees, Kovjanic, Schuh, and Jonas (2013) find that psychological needs satisfaction, particular competence and relatedness needs satisfaction, enhances employee engagement (significant at the p < .05 level). Nonetheless, these aforementioned positive paths from motivational language and needs satisfaction to organizational engagement have been mainly suggested or documented in non-crisis settings. We therefore extend such relationships to organizational crisis contexts:

H7

Leaders’ (a) direction giving, (b) empathetic, and (c) meaning-making language is positively associated with organizational engagement during a crisis.

H8

Employees’ satisfaction of (a) autonomy, (b) relatedness, and (c) competence is positively associated with organizational engagement during a crisis.

2.5. Employees’ psychological needs satisfaction and crisis coping as sequential mediators

Synthesizing the above-mentioned theoretical perspectives and empirical evidence from research on MLT, SDT, the transactional model of stress and coping, and organizational engagement, we further propose a sequential mediation process in which the three forms of leaders’ motivational language—direction-giving, empathetic, and meaning-making—enhance employee engagement through first satisfying employees’ psychological needs and then impacting their crisis coping (see Fig. 1). In other words, we theorize that employees’ needs satisfaction and coping will sequentially mediate the path from direct-giving/empathetic/meaning-making language to organizational engagement.

As elaborated previously, the theoretical insights from MLT and SDT (Deci et al., 2017; Mayfield & Mayfield, 2018) suggest the possibility that leaders’ motivational language functions as a motivational force that promotes employees’ intrinsic motivation and basic psychological needs satisfaction (autonomy, relatedness, and competence). Extending this possibility, theoretical reasoning and empirical evidence from SDT and the transactional model of stress and coping (Deci et al., 2017; Yeung et al., 2016) further indicate that employees’ psychological needs satisfaction is a type of coping resources, which affects employees’ subsequent coping behaviors. Building upon the above linkage from motivational language to needs satisfaction to coping, extant literature on the transactional model of stress and coping and organizational engagement introduced earlier (Cheng et al., 2014; Leiter, 1991) adds a potential path from employees’ crisis coping (control and escape coping) to their engagement with the organization. Taken together, these different research streams jointly allude to the possible presence of a motivational language-needs satisfaction-coping-engagement effect chain. This effect chain highlights needs satisfaction and coping as two serial mediators that explains leader communication’s impact on organizational engagement during crisis situations.

To the best of our knowledge, the sequential mediation role of employees’ needs satisfaction and coping has not been examined empirically, especially in the context of organizational crises. Few existing studies that are relevant to our topic have only provided empirical evidence supporting the mediating role of employees’ needs satisfaction while overlooking the mediating role of crisis coping—a vital construct that constitutes a significant part of employees’ psychological experiences during organizational crises (Li et al., 2021). For example, Men, Qin, and Jin (2021) survey 393 U.S. employees and find that leaders’ use of meaning-making, empathetic, and direction-giving language helps increase employee trust toward leadership and the organization during organizational crises, directly and indirectly through fulfilling employees’ need for competence and relatedness. In Men et al.’s (2021) study, the indirect effects of competence and relatedness needs satisfaction are overall significant at the p < .01 level with the effect coefficients ranging from .04 to .07. However, both the direct and indirect effects of autonomy need satisfaction are not examined. In the present study, we advance such prior insights by adding crisis coping as a sequential mediator following the initial mediator of the three needs satisfaction:

H9

The effect of leaders’ direction-giving language on organizational engagement is mediated first by employees’ satisfaction of (a) autonomy, (b) relatedness, and (c) competence needs and then by employees’ (d) control and (e) escape coping.

H10

The effect of leaders’ empathetic language on organizational engagement is mediated first by employees’ satisfaction of (a) autonomy, (b) relatedness, and (c) competence needs and then by employees’ (d) control and (e) escape coping.

H11

The effect of leaders’ meaning-making language on organizational engagement is mediated first by employees’ satisfaction of (a) autonomy, (b) relatedness, and (c) competence needs and then by employees’ (d) control and (e) escape coping.

3. Method

3.1. Sampling and participants

To test the proposed model, an online survey was conducted among 490 full-time employees working in more than 20 diverse industries in the United States during the second and third weeks of April 2020. These participants were recruited with the assistance of Qualtrics, a premier global provider of survey services that had access to 1.5 millions of panel participants in the U.S. through its patented sampling platform. To achieve a representative sample of U.S. employees according to the most recent U.S. census data in terms of gender, age, and ethnicity categories, this study used stratified random sampling. Table 1 summarized participants’ demographic information and work backgrounds.

Table 1.

Participants Profile (N = 490).

| Variable | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Age | ||

| 18–24 | 17 | 3.5 % |

| 25–34 | 135 | 27.6 % |

| 35–44 | 98 | 20.0 % |

| 45–54 | 76 | 15.5 % |

| 55–64 | 133 | 27.1 % |

| 65 or above | 31 | 6.3 % |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 240 | 49.0 % |

| Female | 250 | 51.0 % |

| Ethnicity | ||

| White/Caucasian | 304 | 62.0 % |

| Black/African American | 64 | 13.1 % |

| Hispanic/Latino | 83 | 16.9 % |

| Asian/Asian American | 25 | 5.1 % |

| American Indian/Alaska Native | 4 | .8 % |

| Other | 10 | 2.0 % |

| Education | ||

| High school diploma or equivalent | 49 | 10.0 % |

| Some college, no degree | 112 | 22.9 % |

| Bachelor’s degree or equivalent | 193 | 39.4 % |

| Master's degree or equivalent | 108 | 22.0 % |

| Doctoral or professional degree or equivalent | 28 | 5.7 % |

| Income | ||

| Less than $20,000 | 22 | 4.5 % |

| $20,000 to $39,999 | 67 | 13.7 % |

| $40,000 to $59,999 | 115 | 23.5 % |

| $60,000 to $79,999 | 101 | 20.6 % |

| $80,000 to $99,999 | 61 | 12.4 % |

| $100,000 or more | 124 | 25.3 % |

| Company Tenure | ||

| < 1 year | 32 | 6.5 % |

| 1–3 years | 94 | 19.2 % |

| 4–6 years | 101 | 20.6 % |

| 7–9 years | 60 | 12.3 % |

| 10 years or above | 203 | 41.4 % |

| Job Position | ||

| Non-management | 232 | 47.3 % |

| Lower-level management | 168 | 34.3 % |

| Middle-level management | 39 | 8.0 % |

| Upper-Level management | 51 | 10.4 % |

| Company Size | ||

| 0–99 | 146 | 29.8 % |

| 100–249 | 47 | 9.6 % |

| 250–499 | 46 | 9.4 % |

| 500–749 | 37 | 7.6 % |

| 750–999 | 29 | 5.9 % |

| 1000–1499 | 36 | 7.3 % |

| 1500 or above | 149 | 30.4 % |

Note. As to COVID-19 related work information, a majority of the participants reported that their companies provided work-from-home options (73.3 %) and adjusted the sick and leave policy (61 %). Around 25.9 % of these participants acknowledged that there were confirmed COVID-19 cases among employees in their companies.

3.2. Measures

The key variables were all measured using the 7-point Likert scale anchored by 1 = strongly disagree to 7 = strongly agree. All the variable measures were adopted from previous literature and adapted to fit this study’s context of the COVID-19 outbreak (see Table 2 for specific measurement items per variable, and measurement reliability and sources). Before the main survey administration, one pretest was conducted among 60 full-time employees working in the U.S. via Amazon Mechanical Turk to ensure the reliability and validity of the variable measures. These pretest participants completed the survey and provided feedback on the thematic clarity, wording, and format of the survey. A few measurement items were reworded to avoid ambiguity according to their feedback.

Table 2.

Measurement Items.

| Factor | Scale items | Standardized Factor loadings | CR | AVE | The square root of AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Direction-Giving Language (ɑ = .94; adapted from Mayfield & Mayfield, 2018) | My manager … | .94 | .81 | .90 | |

| Provides me with helpful information about forthcoming work-related changes during COVID-19 outbreak. | .90*** | ||||

| Gives me useful explanations of what needs to be done in my work during COVID-19 outbreak. | .90*** | ||||

| Provides me with helpful information about past changes affecting my work due to COVID-19 outbreak. | .88*** | ||||

| Gives me a clear instruction about solving job-related problems during COVID-19 outbreak. | .91*** | ||||

| Empathetic Language (ɑ = .94; adapted from Mayfield & Mayfield, 2018) | My manager … | .94 | .77 | .88 | |

| Shows me encouragement for my work efforts during COVID-19 outbreak. | .91*** | ||||

| Shows concerns about my job satisfaction during COVID-19 outbreak. | .80*** | ||||

| Gives me praise for my good work during COVID-19 outbreak. | .88*** | ||||

| Expresses his/her support for my work during COVID-19 outbreak. | .92*** | ||||

| Asks me about my professional well-being during COVID-19 outbreak. | .87*** | ||||

| Meaning-Making Language (ɑ = .85; adapted from Mayfield & Mayfield, 2018) | My manager … | .88 | .64 | .80 | |

| Tells me stories about people who handle their work well during COVID-19 outbreak. | .79*** | ||||

| Tells me stories about people who cope well with COVID-19 outbreak in this organization. | .79*** | ||||

| Tells me stories about people’s experiences making adjustment at work during COVID-19 outbreak. | .80*** | ||||

| Tells me stories about how people in this organization have successfully managed their work during COVID-19 outbreak. | .82*** | ||||

| Autonomy Need Satisfaction (ɑ = .93; adapted from Deci et al., 2001; Van den Broeck, Vansteenkiste, De Witte, Soenens, & Lens, 2010) | During the COVID-19 outbreak … | .93 | .73 | .85 | |

| I am allowed to make my own decisions when dealing with the tasks at work. | .87*** | ||||

| I can decide how to do my job according to my own will. | .81*** | ||||

| I feel like I can make a lot of inputs to deciding how my job gets done. | .88*** | ||||

| I am free to express my ideas and opinions regarding my work at work. | .84*** | ||||

| There are a lot of opportunities for me to decide for myself how to go about my work. | .86*** | ||||

| Relatedness Need Satisfaction (ɑ = .88; adapted from Deci et al., 2001; Van den Broeck et al., 2010) | During the COVID-19 outbreak … | .89 | .61 | .78 | |

| I feel connected with other people at work. | .83*** | ||||

| I feel part of a group at work. | .80*** | ||||

| I get along well with other people at work. | .72*** | ||||

| I can talk with people about things that really matter to me at work. | .79*** | ||||

| I don’t feel alone when I’m with my colleagues. | .76*** | ||||

| Competence Need Satisfaction (ɑ = .93; adapted from Deci et al., 2001; Van den Broeck et al., 2010) | During the COVID-19 outbreak … | .93 | .74 | .86 | |

| I master my tasks at work. | .87*** | ||||

| I am competent at accomplishing my tasks at work. | .85*** | ||||

| I am good at completing my tasks at work. | .89*** | ||||

| I have the feeling that I can even accomplish the most difficult tasks at work. | .83*** | ||||

| I feel confident that I can successfully complete my tasks at work. | .86*** | ||||

| Control Coping (ɑ = .83; adapted from Fugate et al., 2008; Latack, 1986) | In light of the way my company handles COVID-19 related issues … | .87 | .63 | .79 | |

| I try to see the situation as an opportunity to learn and develop new skills. | .80*** | ||||

| I put extra attention to planning and scheduling. | .73*** | ||||

| I try to think of myself as a winner – as someone who always comes through. | .73*** | ||||

| I tell myself that I can probably work things out to my advantage. | .69*** | ||||

| I request help from people who have the power to do something for me. | .59*** | ||||

| Escape Coping (ɑ = .74; adapted from Fugate et al., 2008; Latack, 1986) | In light of the way my company handles COVID-19 related issues … | .76 | .52 | .72 | |

| I tell myself that time takes care of situations like this. | .55*** | ||||

| I accept this situation because there is nothing I can do to change it. | .81*** | ||||

| I accept this situation because it is unchangeable. | .77*** | ||||

| Organizational Engagement (ɑ = .95; adapted from Saks, 2006) | During the COVID-19 outbreak… | .95 | .75 | .87 | |

| I feel being a member of this company is very captivating. | .88*** | ||||

| I feel one of the most exciting things for me is getting involved with things happening in this company. | .88*** | ||||

| I feel I am really into the “goings-on” in this company. | .83*** | ||||

| I feel being a member of this company make me come “alive.” | .88*** | ||||

| I feel being a member of this company is exhilarating for me. | .88*** | ||||

| I feel I am highly engaged in this company. | .83*** |

Note. ***p < .001; CR = composite reliabilities; AVE = average variance extracted.

3.3. Data analysis

For hypothesis testing, we conducted the structural equation modeling (SEM) with the Mplus program, following a two-step process from Anderson and Gerbing (1988). First, the measurement model was assessed, followed by evaluating the structural model. The model fit was evaluated according to Hu and Bentler’s (1999) joint criteria, which was one of the most conservative methods: Either “CFI > .95 and SRMR < .10” or “RMSEA < .05 and SRMR < .10” suggested a good model fit.

4. Results

4.1. Preliminary analysis

Demographic variables (i.e., age, gender, ethnicity, education, income, location), work-related variables (i.e., tenure year, job position), organizational variables (i.e., organization size, industry type, whether any person in the company had been diagnosed with COVID-19), and perceived issue importance may affect employee needs satisfaction, coping strategies, or organizational engagement (e.g., Shen & Jiang, 2019). Therefore, a series of hierarchical regression analyses were performed to check which of these variables significantly impacted the key variables in this study. Results suggested that age, gender, income, job position, organizational size, industry type, whether any person in the company had been diagnosed with COVID-19, and perceived issue importance were significant predictors. Specifically, results from regression analyses1 indicated that perceived issue importance (β = .14, p = .002), income (β = .11, p = .028), and job position (β = .20, p < .001) significantly and positively predicted autonomy. Perceived issue importance (β = .20, p < .001) and income (β = .11, p = .045) both significantly and positively predicted relatedness need satisfaction. Perceived issue importance (β = .21, p < .001) also significantly and positively predicted competence need satisfaction. Regarding control coping, perceived issue importance (β = .25, p < .001), income (β = .13, p = .012), and job position (β = .165, p = .001) were significant positive predictors, whereas age (β = −.15, p = .002) was a significant negative predictor. Perceived issue importance (β = .10, p = .033), gender (β = .11, p = .017), and organizational size (β = .17, p = .001) significantly and positively predicted escape coping, while whether any person in the company had been diagnosed with COVID-19 (β = −.13, p = .008) and industry type (β = −.09, p = .041) significantly and negatively predicted escape coping. Last, perceived issue importance (β = .13, p = .003), income (β = .13, p = .012), and job position (β = .22, p < .001) significantly and positively predicted organizational engagement, while whether any person in the company had been diagnosed with COVID-19 (β = −.127, p = .006) significantly and negatively predicted organizational engagement. Accordingly, these variables were controlled on every path in the subsequent SEM analysis. Please see Table 3 for descriptive statistics of the main latent variables in this study.

Table 3.

Descriptive Statistics and Correlations among Key Variables.

| M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Direction-giving language | 5.32 | 1.41 | ||||||||

| Empathetic language | 5.06 | 1.47 | .721** | |||||||

| Meaning-making language | 4.15 | 1.48 | .364** | .365** | ||||||

| Autonomy | 5.23 | 1.37 | .448** | .461** | .212** | |||||

| Relatedness | 5.24 | 1.23 | .464** | .501** | .200** | .579** | ||||

| Competence | 5.68 | 1.20 | .332** | .328** | .067 | .610** | .571** | |||

| Control coping | 5.14 | 1.11 | .446** | .429** | .280** | .581** | .586** | .554** | ||

| Escape coping | 5.04 | 1.01 | .146** | .123** | .040 | .179** | .148** | .119** | .192** | |

| Organizational engagement | 4.56 | 1.49 | .547** | .512** | .365** | .537** | .550** | .398** | .576** | .103* |

Note. *p < .05, **p < .01.

Given the relatively high correlations among the main variables, we acknowledge potential multicollinearity and common method bias in the data. To address these issues, we used Harman’s single-factor score and confirmatory factor analysis (CFA), following the guideline suggested by Podsakoff, MacKenzie, Lee, and Podsakoff (2003). First, the result of Harman’s score revealed that 41.78 % of the total variance was explained by the single factor score, which was lower than the 50 % threshold. Second, CFA result showed that the one-factor model did not fit the data well: χ2(989) = 9578.088, RMSEA = .133 [.131, .136], CFI = .489, TLI = .466, SRMR = .114. Taken together, these results confirmed that common method bias did not pose a threat to our data.

4.2. SEM analysis

4.2.1. Measurement model

A CFA was performed to test the measurement model. The original values of fit indexes indicated that all factor loading values were significant. Previous research stated that standardized factor loadings should be greater than .5 to improve the fit of the measurement model (Hair, Babin, Anderson, & Black, 2018). Thus, measurement items with standardized factor loading below .5 were dropped. Three items (“I anticipate the negative consequences so that I’m prepared for the worst,” “I try not to be concerned about it,” “I remind myself that work isn’t everything”) were removed from the escape coping measure. One item (“offers me advice about how to work with other members of this organization during COVID-19 outbreak”) was removed from the meaning-making language measure. The final model-data fit results were satisfactory: χ2(783) = 1470.578, RMSEA = .042 [.039, .046], TLI = .954, CFI = .958, SRMR = .053. Furthermore, as shown in Table 2, the composite reliabilities (CR) for all variables were higher than .6 and the values of the average of variance extracted (AVE) were higher than .5. The square root values of AVE were greater than the construct correlations. These results demonstrated internal consistency, convergent and discriminant validity of our measures.

4.2.2. Structural model

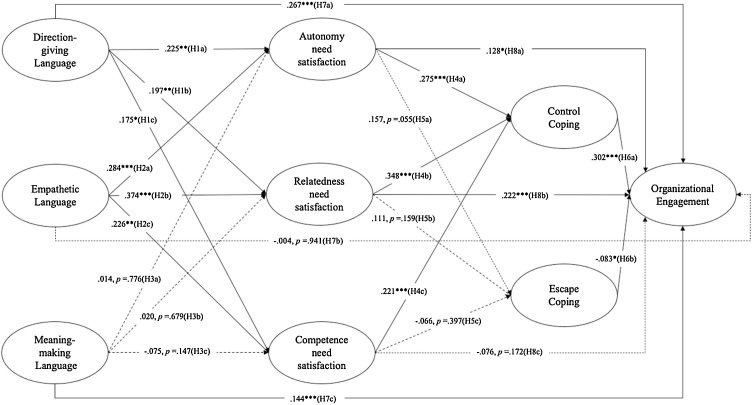

The test of the SEM model indicated a good fit to the data based on Hu and Bentler’s (1999) joint criteria: χ2(1282) = 2264.835, RMSEA = 040 [.037, .042], TLI = .942, CFI = .948, SRMR = .056.2 To identify the model with the best fit, a theoretically-plausible competing model was compared with the hypothesized model. The competing model did not contain the direct paths from motivating language and needs satisfaction to engagement. This competing model was found significantly worse than the original hypothesized model (Δχ2(6) = 109.275, p < .001). Therefore, we retained the hypothesized model as the final model (see Fig. 2 ).

Fig. 2.

The model testing results.

4.3. Hypotheses testing

H1a–c through H3a–c examined the associations between leaders’ motivating language and employees’ needs satisfaction. Results indicated that direction-giving language was positively associated with autonomy (β = .225, SE = .07, p = .002, BC 95 % CI: [.106–.344]), relatedness (β = .197, SE = .07, p = .006, BC 95 % CI: [.079–.316]), and competence (β = .175, SE = .08, p = .024, BC 95 % CI: [.047–.302]) needs satisfaction. Likewise, empathetic language was positively related with autonomy (β = .284, SE = .07, p < .001, BC 95 % CI: [.169–.399]), relatedness (β = .374, SE = .07, p < .001, BC 95 % CI: [.260–.488]), and competence (β = .226, SE = .08, p = .003, BC 95 % CI: [.103–.349]) needs satisfaction. However, contrary to our expectation, meaning-making language was not significantly related to autonomy (β = .014, SE = .05, p = .776, BC 95 % CI: [−.066 to .094]), relatedness (β = .020, SE = .05, p = .679, BC 95 % CI: [−.060 to .100]), and competence (β = −.075, SE = .05, p = .147, BC 95 % CI: [−.160 to .010]) needs satisfaction. Therefore, H1a–c and H2a–c were supported, whereas H3a–c were not supported.

H4a–c and H5a–c predicted the links between employees’ needs satisfaction and coping strategies. Results revealed that the satisfaction of autonomy (β = .257, SE = .06, p < .001, BC 95 % CI: [.163–.351]), relatedness (β = .348, SE = .06, p < .001, BC 95 % CI: [.258–.438]) and competence (β = .221, SE = .06, p < .001, BC 95 % CI: [.131–.312]) needs was positively associated with control coping. However, autonomy (β = .157, SE = .08, p = .055, BC 95 % CI: [−.003 to .291]), relatedness (β = .111, SE = .08, p = .159, BC 95 % CI: [−.019 to .241]) and competence (β = −.066, SE = .08, p = .397, BC 95 % CI: [−.195 to .062]) needs satisfaction was not associated with escape coping. Thus, H4a–c were supported but H5a–c were not.

H6a-b proposed the relationships between coping strategies and organizational engagement. Specifically, control coping (β = .302, SE = .07, p < .001; BC 95 % CI: [.192–.412]) was positively related with engagement whereas escape coping (β = −.083, SE = .04, p = .037, BC 95 % CI: [−.149 to −.018]) was negatively associated with engagement. Hence, H6a-b was supported.

H7a–c predicted the direct effects of leaders’ motivating language on organizational engagement. Results revealed that direction-giving (β = .267, SE = .06, p < .001, BC 95 % CI: [.169–.365]) language and meaning making language (β = .144, SE = .04, p < .001, BC 95 % CI: [.079–.210]) were positively related to engagement. However, empathetic language (β = -.004, SE = .06, p = .941, BC 95 % CI: [−.104 to .095]) was not related to it. Therefore, H7a and H7c were supported but H7b was not.

Finally, H8a–c discussed the linkages between employees’ needs satisfaction and organizational engagement. Results showed that both autonomy (β = .128, SE = .06, p = .027, BC 95 % CI: [.053–.237]) and relatedness (β = .222, SE = .06, p <.001, BC 95 % CI: [.12–.301]) needs satisfaction was positively associated with engagement. However, competence (β = -.076, SE = .06, p = .172, BC 95 % CI: [−.104 to .071]) was not. Thus, H8a and H8b were supported but H8c was not.

To test H9 to H11 on indirect (mediation) effects, bootstrapping with 5000 samples was employed. An indirect effect is significant if the bootstrapping confidence interval (BC) does not include zero (Preacher & Hayes, 2008). As shown in Table 4 , the path from direction-giving language to engagement was first mediated by autonomy (β = .03, SE = .01, BC 95 % CI: [.01–.05]), relatedness (β = .02, SE = .01, BC 95 % CI: [.005–.04]), competence (β = .02, SE = .01, BC 95 % CI: [.003–.05]), and then by control coping. All the sequential mediation paths from direction-giving language to engagement via the three needs satisfaction and then escape coping, however, were not significant (i.e., BC 95 % CIs included 0). Furthermore, as reported in Table 5 , the relationship between empathetic language and engagement was first mediated by autonomy (β = .03, SE = .01, BC 95 % CI: [.01–.06]), relatedness (β = .04, SE = .01, BC 95 % CI: [.02, .06]), and competence (β = .03, SE = .01, BC 95 % CI: [.01–.05]) and then by control coping. All the sequential mediation paths from empathetic language to engagement through the three needs satisfaction and then escape coping, however, were not significant (i.e., BC 95 % CIs included 0). Last, as indicated in Table 6 , none of the sequential mediation paths from meaning-making language to engagement were significant (i.e., BC 95 % CIs included 0). Therefore, H9a–d and H10a–d were supported. However, H9e, H10e, and H11a–e were not supported.

Table 4.

Indirect Effects of Direction-Giving Language on Organizational Engagement: Partial Mediation.

| β | SE | BC 95 % CI | |

|---|---|---|---|

| DG → Autonomy → CC → OE | .03 | .01 | [.01, .05] |

| DG → Relatedness → CC → OE | .02 | .01 | [.005, .04] |

| DG → Competence → CC → OE | .02 | .01 | [.003, .05] |

| DG → Autonomy → EC → OE | −.001 | .002 | [−.01, .001] |

| DG → Relatedness → EC → OE | −.001 | .001 | [−.003, .001] |

| DG → Competence → EC → OE | −.0001 | .001 | [−.002, .001] |

Note. DG = Direction-Giving Language; CC = Control Coping; EC = Escape Coping; OE = Organizational Engagement.

Table 5.

Indirect Effects of Empathetic Language on Organizational Engagement: Full Mediation.

| β | SE | BC 95 % CI | |

|---|---|---|---|

| EL → Autonomy → CC → OE | .03 | .01 | [.01, .06] |

| EL → Relatedness → CC → OE | .04 | .01 | [.02, .06] |

| EL → Competence → CC → OE | .03 | .01 | [.01, .05] |

| EL → Autonomy → EC → OE | −.002 | .002 | [−.01, .002] |

| EL → Relatedness → EC → OE | −.001 | .002 | [−.01, .002] |

| EL → Competence → EC → OE | −.0002 | .001 | [−.002, .001] |

Note. EL = Empathetic Language; CC = Control Coping; EC = Escape Coping; OE = Organizational Engagement.

Table 6.

Indirect Effects of Meaning-Making Language on Organizational Engagement.

| β | SE | BC 95 % CI | |

|---|---|---|---|

| MM → Autonomy → CC → OE | .002 | .01 | [−.01, .01] |

| MM → Relatedness → CC → OE | .002 | .01 | [−.01, .01] |

| MM → Competence → CC → OE | −.01 | .01 | [−.02, .01] |

| MM → Autonomy → EC → OE | −.0001 | .0004 | [−.001, .001] |

| MM → Relatedness → EC → OE | .0000 | .0003 | [−.001, .0004] |

| MM → Competence → EC → OE | .0001 | .0003 | [−.0004, .001] |

Note. MM = Meaning-Making Language; CC = Control Coping; EC = Escape Coping; OE = Organizational Engagement.

5. Discussion

By bridging perspectives from MLT, SDT, the transactional model of stress and coping, and organizational engagement research, this study provides fresh, interdisciplinary insights on employee responses to leader communication during organizational crises. It theorized and empirically tested a conceptual framework that advances our understanding of how leaders can better motivate employees to stay engaged with their organizations in times of adversity. Its results confirmed the motivational value of leaders’ empathetic, direction-giving, and mean-making messages in sustaining employees’ dedicated role performance during one of the most critical and vulnerable stages of organizational life (i.e., crises). Its results also revealed the underlying psychological mechanism that explained the effectiveness of leaders’ motivational communication, highlighting the roles of employees’ needs satisfaction and subsequent coping strategies as serial mediators in the process. These insights, particularly the aforementioned psychological mechanism, have not been adequately identified by previous public relations research but are much needed in today’s environment where businesses are struggling to survive amidst the unprecedented global pandemic.

5.1. Discussion of major findings

Overall, the empirical evidence of this study largely supported the proposed conceptual framework. Consistent with the predictions derived from MLT, SDT, the transactional model, and organizational engagement literature, our results showed that leaders’ direction-giving and empathetic speech promoted employees’ satisfaction of the three fundamental psychological needs: autonomy, relatedness, and competence. The three needs satisfaction further drove employees’ adoption of control coping strategies to directly tackle crisis-induced stressors, which in turn sustained their engagement with the organization. Additionally, our results evidenced the sequential mediation effect of needs satisfaction (autonomy, relatedness, and competence) and control coping on the relationship between direction-giving language and employee engagement. Meanwhile, the sequential mediation effect of needs satisfaction (autonomy, relatedness, and competence) and control coping on the relationship between empathetic language and employee engagement was also supported. Together, these mediation results delineated a motivational language-needs satisfaction-coping-engagement effect chain, revealing needs satisfaction and control coping as the core psychological mechanism driving the influences of leaders’ direction-giving and empathic words on employee engagement during turbulent times.

Among the aforementioned expected findings, two merit special attention from organizational researchers and practitioners. First, leaders’ empathetic language emerged to be the strongest predictor of employees’ needs satisfaction (see its path coefficients in Fig. 2). It explained a larger portion of variance in the three needs satisfaction than other forms of motivational language. This effect pattern was novel and critical as previous research on MLT concluded that empathic language had been the least used form of speech in leader-follower discourse (J. Mayfield & Mayfield, 2018). In times of crisis, it is imperative for leaders to take perspectives, show care and sensitivity, and provide social support to employees (Bundy et al., 2017). These empathic messages and acts have also been emphasized by crisis communication theories such as the situational crisis communication theory (Coombs, 2019) and discourse of renewal (Ulmer et al., 2017). Extending this line of research, our study demonstrates the importance of leaders’ use of empathetic language in communicating with employees during a crisis.

Relating to the above point, employees’ need for relatedness, as a significant mediator, formed the strongest relationship with control coping (see its path coefficient in Fig. 2). This means, while employees’ autonomy and competence were necessary psychological resources for effective crisis coping, employees’ sense of relatedness to their organization may function as the leading force that promoted problem-solving oriented coping behaviors. Such a result matters to SDT research because it implies that the salience and significance of one specific type of needs satisfaction may slightly vary according to contextual cues. Compared to routine work contexts, employees tend to develop an acute need for relatedness in crisis situations (perhaps more so than their need for autonomy and competence) owing to the fear of being alienated, helpless, and left at a loss (Kahn, Barton, & Fellows, 2013). Therefore, the presence of a strong social support network, exemplified by leaders’ motivational messages, is critical to cultivate employees’ felt belonging and provide them with instrumental resources to proactively address crisis-related problems (Charoensukmongkol & Phungsoonthorn, 2020).

While most findings are in line with extant literature, the following results were unexpected. To start, leaders’ meaning-making language was shown as a non-significant predictor of employees’ needs satisfaction (H3a–c), which further led to a non-significant mediation path from meaning-making language to organizational engagement via employees’ needs satisfaction and coping (H11a–e). The finding on the non-significant relationship between meaning-making language and employees’ needs satisfaction deviated from our proposition deduced from MLT and SDT. Nonetheless, it should not be used as evidence to depreciate the value of meaning-making communication during turbulent times. Instead, such communication remained indispensable (Ulmer et al., 2017) as it was found to directly contribute to organizational engagement (H7c). A possible explanation for the insignificant relationship may lie in the shared variance that meaning-making language had with the other two forms of language. Conceptually speaking, meaning-making language can be intertwined with direction-giving language when leaders are, for example, articulating work expectations and explaining how employees’ individual performance relates to organizational goals in countering crisis impact (Mayfield & Mayfield, 2018). It can also be intersected with empathic language when leaders are, for instance, applauding employees for their efforts to champion the organizational mission despite the crisis challenge (Mayfield & Mayfield, 2018). Hence, its unique effect in enhancing employees’ need satisfaction might have been overshadowed by that of direction-giving and empathic messages. Indeed, when we statistically regressed needs satisfaction on meaning-making language via a simple linear regression, the significant effect of meaning-making language emerged (ps < .001).

Another unexpected finding was the non-significant relationship between employees’ needs satisfaction and escape coping (H5a–c), which further made the mediation paths from the three forms of motivational language to organizational engagement through employees’ needs satisfaction and escape coping non-significant (H9e, H10e, and H11e). These findings contradicted our predictions derived from SDT and the transactional model of stress and coping. They may be attributed to the characteristics of the crisis examined in this study (i.e., organizational crises that emerged from the COVID-19 outbreak). According to coping literature, escape coping may become inevitable when stressors relate to one’s health and are of high severity (Ben-Zur, 2019). The global pandemic and organizational crises induced by it seem to fall into that category. People’s use of escape coping strategies to regulate emotional distress has been evident during the COVID-19 outbreak (e.g., Király et al., 2020). Our survey data also reflected such a tendency: As shown in Table 3, the mean score of escape coping was high and had limited variance. This data distribution pattern might have made the relationship between employees’ needs satisfaction and escape coping difficult to observe, resulting in non-significant findings.

Lastly, we found that neither empathic language (H7b) nor competence need satisfaction (H8c) was not directly associated with organizational engagement. These two non-significant direct effects were inconsistent with our postulations based on MLT or SDT. Nonetheless, they did not mean that empathic language or competence need satisfaction was not related to organizational engagement. Instead, these two antecedents were linked to engagement indirectly through two distinct mediation mechanisms. As reported in our mediation results (also see Table 5), the path from leaders’ empathetic language to employees’ organizational engagement was fully and sequentially mediated by employees’ needs satisfaction and then control coping. Similarly, our mediation results showed that the path from competence need satisfaction to organizational engagement was fully mediated by control coping.3 The identification of these two mediating routes is novel. It builds an in-depth understanding of employees’ psychological experiences during crises—specifically, how engagement is fostered by motivational speech.

5.2. Theoretical contributions

This study represents a theory building effort that advances our understanding of effective internal crisis communication—a critical yet understudied area in public relations literature (Johansen, Aggerholm, & Frandsen, 2012). Public relations scholars have called for “more scholarly attention to internal publics for theoretical development in crisis communication, because employees’ importance is not sufficiently explored in the extant theories” (Kim, 2020, p. 66). This study answers the call by applying an interdisciplinary perspective that shows how leaders’ motivational communication can enhance employees’ needs satisfaction, promote their proactive crisis coping, and ultimately secure the essential public relations outcome: employee engagement.

Furthermore, this study expands the nomological networks of the three theories—MLT, SDT, and the transactional model of coping and stress—as well as that of the organizational engagement construct. These four schools of thought have been separately examined in the work domain. Each has a unique theoretical emphasis and tackles a different piece of the puzzle concerning workplace phenomena. For theory to advance, however, it is critical to examine how these pieces fit together and integratively advance internal public relations research. Thus, we locate the theoretical common ground that ties the four schools of thought together: employee motivation. Upon this common ground, we build a holistic model that maps how leader communication (MLT), as a motivational source, drives employees’ needs satisfaction (SDT) and how such needs satisfaction further serves as psychological resources that motivate employees’ crisis coping (the transactional model), which ultimately influences employees’ motivated role performance as a member of the organization (organizational engagement). In this model, MLT, SDT, the transactional model, and organizational engagement are seamlessly connected with each other in a way that the key components of one theory serve as another theory’s antecedents or outcomes in its nomological network. Together, they enrich our understanding of the effects of leader communication during organizational crises.

Not only does our model offer a holistic view on employee responses to leader communication during organizational crises, it also provides novel and nuanced insights into the dimensional relationships among the three theories: MLT, SDT, and the transactional model. Instead of treating motivational language or needs satisfaction or coping as one general construct, this study differentiates between specific dimensions of motivational language, needs satisfaction, and coping. It further explicates how each dimension of one construct relates to that of another construct. Such a fine-grained approach not only makes our understanding of the three theories’ nomological networks more in-depth, it also enables us to unpack the mechanism underlying leaders’ crisis communication effects in detail, which therefore contributes to internal crisis communication scholarship in public relations.

5.3. Practical implications

This study provides strategic insights on how leaders can engage in effective internal communication to counter crisis negativity. First, we recommend organizational leaders at all levels to participate in communication training. The goals of such training are to improve leaders’ understanding of the benefits of motivating language and to increase their competence in orchestrating the application of the three forms of motivating language during organizational crises. For example, leaders should communicate work expectations, address task specificity, and explain reward contingencies in a transparent way. During this direction-giving process, they should make special efforts to clarify how those work elements are changing throughout the course of the crisis and after the crisis is contained. As new adaptive challenges continue to emerge during turbulent times, leaders should be constantly aware of their employees’ evolving concerns through active listening and should provide constructive feedback to dispel any ambiguity. Multiple communication channels such as written emails, virtual meetings, in-person or phone conservations, and internal social media sites can assist leaders to ensure direct, open, and timely communication with their employees.

Second, leaders are recommended to display their humanity, sensitivity, and care to employees through both verbal support (e.g., encouraging words) and non-verbal gestures (e.g., smile and thumbs-up). Emotional bonding with leaders is desired by employees during uncertain times (Ulmer et al., 2017). It is a wise investment for leaders to take time to understand employees’ struggles, acknowledge their perspectives, and applaud their efforts to overcome challenges. It is also necessary for leaders to reassure employees that showing anxiety is normal during organizational crises and that “we are in this together” to win the battle. These empathetic acts should be applied not only in work situations but also to employees’ personal life events.

Third, leaders at different levels in the organization should avidly communicate organizational value and mission and help employees make sense of “what we stand for,” “where we are now,” and “where are we heading to” when facing adversities. Leaders should be mindful of employees’ personal values and goals. Based on such knowledge, leaders can tailor stories, anecdotes, and metaphors to guide employees’ interpretations of their personal roles in helping organizations survive and thrive in crisis situations, which will likely contribute to their engagement with the organization.

Apart from the necessity of using motivational language, the importance of understanding and satisfying employees’ psychological needs, particularly their need for relatedness, should not be trivialized. Leaders should assess and track employees’ sense of needs satisfaction during and after organizational crises. This can be done informally by soliciting employees’ feedback via personal conversations or town hall meetings. This can also be achieved formally by administering anonymous surveys to employees at different time points throughout the crisis. Since needs satisfaction may influence coping strategy selection, as shown by our results, leaders’ knowledge of employees’ needs will help them to anticipate which coping strategy is likely to be prioritized by employees and what implications it may have on employee engagement. Finally, although emotion-oriented, escape coping might inevitably occur in an unpredictable and health-related organizational crisis, leaders should still strive to motivate employees’ adoption of control coping and encourage them to directly address crisis-induced stressors. In this regard, leaders’ motivational communication and their provision of instrumental resources and social support networks become essential.

5.4. Limitations and future research

Despite its contributions, this study has several caveats to be addressed by future research. First, it used a cross-sectional design. Although SEM was conducted to simultaneously evaluate the entire system of variables in the study’s conceptual model, causal relationships between these variables cannot be fully established until experimental or longitudinal designs are used. Second, although our conceptual model was tested in an underexplored crisis context (i.e., organizational crises that emerged from a global pandemic), we recommend future studies to replicate the model in other crisis scenarios so as to test and expand its applicability. Relatedly, our model can be further enhanced by incorporating crisis-specific variables as well as other organization, leadership, and work team-related factors to inform its predictions, which will contribute to a more comprehensive understanding of employees’ psychological and behavioral responses during organizational crises.

Funding

The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Declaration of Competing Interest