Abstract

In vitro meat production via stem cell technology and tissue engineering provides hypothetically elevated resource efficiency which involves the differentiation of muscle cells from pluripotent stem cells. By applying the tissue engineering technique, muscle cells are cultivated and grown onto a scaffold, resulting in the development of muscle tissue. The studies related to in vitro meat production are advancing with a seamless pace, and scientists are trying to develop various approaches to mimic the natural meat. The formulation and fabrication of biodegradable and cost-effective edible scaffold is the key to the successful development of downstream culture and meat production. Non-mammalian biopolymers such as gelatin and alginate or plant-derived proteins namely soy protein and decellularized leaves have been suggested as potential scaffold materials for in vitro meat production. Thus, this article is aimed to furnish recent updates on bioengineered scaffolds, covering their formulation, fabrication, features, and the mode of utilization.

Keywords: Tissue engineering, Scaffold, Biopolymers, Plant proteins, In vitro meat

Introduction

In vitro meat, also known as “cultured meat” or “lab-grown meat,” is a pressing need in the current scenario because conventional meat production and consumption are associated with spread of antibiotic resistance, greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, and health complications such as increasing prevalence of zoonotic and chronic diseases such as COVID-19, diabetes, cancer, stroke, Alzheimer’s disease, and cardiovascular diseases (Etemadi et al. 2017; Qian et al. 2020; Singh et al. 2020). As a result, it is clear that conventional meat consumption plays a significant role in the increasing frequency of human health diseases, necessitating the development of a technology for the production of clean and disease-free meat.

Thus, in vitro meat has been suggested as a potential alternative to conventional meat because lab grown muscle cells are used for in vitro production without compromising the nutritional profile, avoiding animal slaughtering, and posing a low risk of infection spread (Van Der Weele and Driessen 2019; Hong et al. 2021). Furthermore, life cycle assessment (LCA) revealed that lab grown meat could outperform conventional meat in terms of resource utilization, reducing GHG emissions and land use by 63–95% (Odegard and Sinke 2021; Bomkamp et al. 2022). Thus, lab-grown meat protects against infectious and chronic diseases while also helping to mitigate the negative environmental impact of conventional meat production and consumption.

In general, in vitro meat production entails the generation and cultivation of stem cell-derived muscle cells on a 3D edible scaffold in order to grow muscle tissue that is similar to conventional meat in terms of texture and sensory properties (Ben-Arye et al. 2020). An efficient in vitro meat production system appears to be made up of two basic components: (1) a prominent cell source that provides a steady supply of muscle cells and (2) an edible scaffold onto which the muscle cells grow to form 3D muscle tissue. Stem cells are one of the potential cell sources for muscle cell differentiation and in vitro meat production, particularly induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs), embryonic stem cells (ESCs), and muscle satellite cells (Verma et al. 2013; Singh et al. 2019; Tiburcy et al. 2019). Stem cells are used to differentiate into myotubes, which serve as a continuous cell source for muscle tissue generation (del Carmen et al. 2019).

On the other hand, scaffolds are 3D biomaterials that provide the niche and mechanical support to the growing myotubes and thus define the dimensions of the muscle tissue (Enrione et al. 2017). Furthermore, scaffold plays an important role in ensuring the efficient transport of oxygen, nutrients, and waste products to and from the cells, as well as controlling the geometry and cell type distribution of the growing tissue, and constitutes a significant portion of the final product. However, because scaffold is a major component of in vitro meat, it should have the same composition and properties as natural meat. Moreover, the composition and fabrication techniques used to form the scaffolds affect its architecture, including porosity, pore size distribution, and interconnectivity, all of which play important roles in muscle cell adhesion, proliferation, and growth (Orellana et al. 2020). Scaffolds made of Matrigel and mammalian biopolymers such as bovine gelatin, collagen, fibrin, and hyaluronic acid (HA), on the other hand, have been widely used in a variety of tissue engineering applications (Enrione et al. 2017). Recognizing the significance of edible scaffolds, the current article delves into the formulations, fabrication, key characteristics, and application of edible scaffolds for in vitro meat production.

Bioengineered edible scaffold: an integrated part of the expedition of in vitro meat production

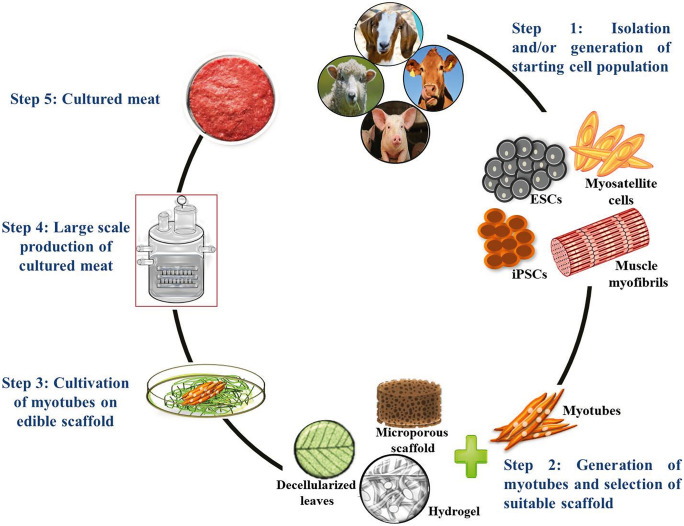

Scaffold is a crucial component in in vitro meat production (Fig. 1) because it is responsible for many of the in vitro meat’s sensory properties such as texture, tenderness, and wetness. Large-scale and cost-effective production of nutritious in vitro meat could be achieved by co-culture of muscle cells, endothelial cells, and supporting cells inside 3D scaffolds (Ben-Arye et al. 2020).

Fig. 1.

Overview of in vitro meat production

However, it is inevitable to design and generate an appropriate scaffold that provides a microenvironment, mechanical support, texture, and nutrient transport to growing muscle cells, which could be accomplished by mimicking the muscle extracellular matrix (ECM) as depicted in Fig. 2 (Bomkamp et al. 2022). Collagen is the main structural protein of muscle ECM, contributing to the mechanical properties of muscle tissue, whereas proteoglycan and glycoprotein, respectively, sequester growth factors and connect the muscle fiber cell membrane to the basement membrane (Gillies and Lieber 2011). It is undeniable that ECM has a significant impact on meat quality and texture due to its biological effects on muscle fibers (Bomkamp et al. 2022).

Fig. 2.

Major components of muscle extracellular matrix

Notably, the edible scaffold formation entails two steps: the first is the selection of an appropriate biomaterial, and the second is the formation of scaffold with desired features such as porosity, mechanical strength, and biocompatibility using different fabrication techniques. Because the goal of in vitro meat production is to avoid animal slaughter, mammalian-derived biomaterials should be avoided for scaffold formation (Enrione et al. 2017). Edible scaffolds made of non-mammalian biopolymers, such as agarose and alginate, or plant-derived components, such as textured soy protein (TSP) and decellularized leaves, are thought to be an ideal substitute for in vitro meat production (Ben-Arye et al. 2020; Orellana et al. 2020; Jones et al. 2021). Moreover, high nutritional value, low cost, and cytocompatibility of plant protein-based scaffolds, such as TSP scaffolds, makes them an appealing candidate for in vitro meat production (Huang et al. 2018). In addition, fabrication techniques including solvent casting, freeze-drying, and decellularization of plant leaves have been reported for the edible scaffold formation for in vitro meat production.

Types of scaffolds for in vitro meat production

Depending on the structure, different types of scaffolds are utilized for cell culture and tissue engineering. Microcarriers are the most popular scaffold for large-scale cell expansion, while porous scaffolds, hydrogels, and fiber scaffolds are typically employed for tissue maturation (Bomkamp et al. 2022). Microcarriers are generally made of polystyrene, cross-linked dextran, cellulose, gelatin, or polygalacturonic acid (PGA) and are coated with collagen, adhesion peptides, or positive charges to increase cell attachment. Microcarriers are yet to be researched and developed as a scaffold for in vitro meat production. However, extensive research is being carried out for developing an edible microcarrier as Modern Meadow Company (NJ, USA) filed a patent for edible microcarrier made up of pectin and cardosin A in 2017 (Marga et al. 2017).

Porous scaffolds are sponge-like structures with pores ranging in size from tens to hundreds of microns that provide mechanical stability to cultured cells (Zeltinger et al. 2001). The size and distribution of scaffold pores is critical for cell culture because larger pores suitable for media perfusion allow efficient transport of nutrients and oxygen, acting as pseudo-vascularization in lab grown meat. Furthermore, a high surface-area-to-volume ratio and pore size allow for high cell density and aid in modulating cellular behavior (Carletti et al. 2011). The hydrogel scaffold is primarily composed of hydrophilic polymers that have a high-water uptake capacity and are cross-linked either physically or chemically (Bomkamp et al. 2022). Diffusion kinetics and hydrogel stiffness have a significant impact on cell proliferation, motility, and differentiation because an optimal rate of diffusion of micronutrients and signaling molecules is required to penetrate the thickness of hydrogel and reach the growing cells, which supports cell proliferation and growth, whereas high stiffness of hydrogel inhibits cell proliferation and migration (Drury and Mooney 2003; Freeman and Kelly 2017). The extensive use of hydrogel in tissue engineering as a 3D ECM-like environment, 3D matrix, bioink, and thin membrane has demonstrated its potential to be used as an edible scaffold for in vitro meat production. Furthermore, food-grade hydrogels derived from several edible species of seaweed, such as carrageenan, which is widely used in meat processing, were shown to be suitable for in vitro meat production (Yegappan et al. 2018).

Materials for bioengineered edible scaffold formation

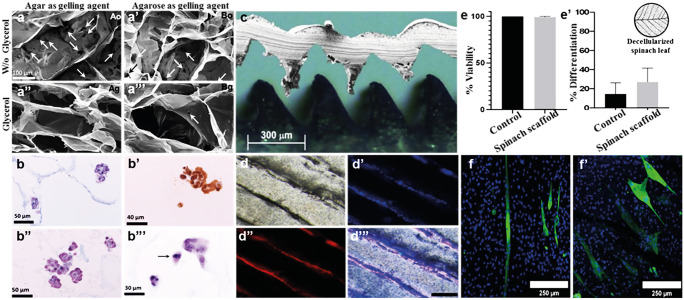

A variety of biomaterials ranging from biopolymers such as gelatin, agarose, and alginate to plant-derived material such as decellularized spinach leaves and soy proteins have been reported as suitable scaffold material for in vitro meat production as shown in Fig. 3. Furthermore, it has been demonstrated that material chemistry and formulation play an important role in muscle cell growth velocity (Jaques et al. 2021). 3D scaffolds made up of non-mammalian biopolymers including salmon gelatin, in combination with alginate (cross-linked by calcium alginate), and gelling agents (agar and agarose) were generated for the cultivation of myoblasts (Fig. 3a–b’”). Moreover, microstructured scaffold film was fabricated using the salmon gelatin, sodium alginate, glycerol, and agarose that stimulated the parallel alignment of myoblasts seeded onto it, which is essentially required for muscle fiber formation (Fig. 3c–d”’). In another study, decellularized spinach leaves were used for the cultivation of bovine satellite cells. After 14 days of seeding, immunofluorescence of myosin heavy chain (MyHC) showed almost twofold change in differentiation efficiency of satellite cells on decellularized spinach in comparison to control (Fig. 3e–f’).

Fig. 3.

Recent studies on generation of edible scaffold for in vitro meat production using different biomaterials. (a–b’”) and (c–d”’) Scaffold made up of biopolymers including gelatin, alginate, agarose, and plasticizer. Adapted under the terms of creative common (CC) BY license (Enrione et al. 2017, Orellana et al. 2020). (e–f’) Decellularized spinach leaf. Adapted with permission (Jones et al. 2021) Copyright Elsevier 2022

Moreover, mammalian biomaterials are associated with the potential of zoonotic disease transmission which should be taken into consideration while choosing the biomaterial for edible scaffold fabrication. For instance, collagen has been suggested as a potential scaffold material, mostly extracted from bovine and porcine tissues, and thus, there is always risk of zoonotic transmission. Unlike mammalian collagen, marine collagen (fish collagen) exhibits excellent biocompatibility and lower zoonotic risks and thus could be used for fabrication of edible scaffold (Lim et al. 2019; Liu et al. 2022).

Biopolymer-based bioengineered edible scaffold structure

Biopolymers used for the formation of scaffold are natural, synthetic, or composite and dictate many of the downstream properties of the in vitro meat (Table 1). Natural biopolymer includes gelatin, hyaluronic acid (HA), fibrin, alginate, agarose, chitosan, and cellulose, which are potential edible scaffold material due to their high biocompatibility, high degradability, and low immunogenicity as depicted in Table 1 (Asti and Gioglio 2014; Campuzano and Pelling 2019). Alternatively, synthetic biopolymer including pluronic acid, poly (ethylene glycol), polyglycolic acid, poly(2-hydroxy ethyl methacrylate), and poly(acrylamide) (Rosales and Anseth 2016) are being used in various tissue engineering applications because they exhibit desired biophysical properties which includes high tunability, suitable topography, interconnected porous structure, mechanical properties, controllable batch-to-batch consistency, and well-defined surface chemistry (Tibbitt and Anseth 2009; Zhu and Marchant 2011; Bolivar-Monsalve et al. 2021). Synthetic biopolymers, on the other hand, might be produced quickly due to their intrinsic polymerization, interlinkage, advantageous molecular structure, and other physical and chemical properties (Reddy et al. 2021). However, synthetic biopolymers are limited by their hydrophobic nature and absence of cell recognition sites, such as the arginylglycylaspartic acid (RGD) peptide motif (Tallawi et al. 2015). Furthermore, bio-functionalization of synthetic biopolymers by immobilization with RGD peptide motif improves cell adherence (Gandaglia et al. 2012); however, RGD peptide motifs are not yet approved for human consumption, limiting its use for in vitro meat production. Thus, it has been suggested that natural biopolymers would be a suitable source for edible scaffold formation. Moreover, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved various natural biopolymers for human consumption including gelatin, chitosan, pectin, cellulose, starch, gluten, alginate, and glucomannan amongst others and thus can be used for the edible scaffold formation.

Table 1.

Potential biopolymers and their key attributes for edible scaffold formation

| Natural biopolymers | Ref. |

|---|---|

| • Protein origin biopolymers | |

|

1. Collagen Source: ECM protein isolated from animals Chemical structure: triple helical structure held together by hydrogen bonds Properties: promotes cell adhesion, proliferation, ECM secretion, biocompatible, low toxicity, rough surface morphology |

Rahman (2019), Seah et al. (2022) |

|

2. Gelatin Source: extracted from alkaline or acidic hydrolysis of type I collagen Chemical structure: comprises 19 amino acid primarily, glycine, proline and 4-hydroxyproline residues in the chemical backbone Properties: high thermal stability, promotes cell adhesion, spreading, and proliferation, ease of gelation, biodegradable |

Wu et al. (2011), Reddy et al. (2021), Seah et al. (2022) |

|

3. Keratin Source: structural protein isolated from horn or wool of animals Chemical structure: cysteine-rich fibrous protein that associate with intermediate filament Properties: promotes cell adhesion and proliferation, bioactivity, biocompatible, self-assembly property |

Rouse and Van Dyke (2010), Feroz et al. (2020) |

| • Polysaccharide origin biopolymers | |

|

1. Alginate Source: polysaccharide extracted from seaweeds Chemical structure: β-(1,4)-linked D-mannuronic acid and α L-guluronic acid monomers along the polymer backbone which can be cross-linked with divalent cations Properties: forms a gel structure due to cross-linking properties, mimics ECM milieu, biocompatible, biodegradable, bioabsorable, hydrophobic |

Acevedo et al. (2012), Asti and Gioglio (2014), Farokhi et al. (2020) |

|

2. Chitosan Source: linear polysaccharide derived from chitin that is found in some mushroom envelopes, green algae cell wall, yeasts, and crustacean shells Chemical structure: linear polysaccharide of (1,4)-linked D-glucosamine and N-acetyl-d-glucosamine residues Properties: promotes cell adhesion, bioactivity, hemostatic potential, longer shelf-life |

Elieh-Ali-Komi and Hamblin (2016), Felfel et al. (2019), Reddy et al. (2021) |

|

3. Starch Source: storage polysaccharide isolated from plants chiefly wheat and potato Chemical structure: polysaccharide chain consisting of two types of α-glucans, i.e., amylose and amylopectin Properties: promotes cell adhesion, biocompatible, hydrophilic, but low mechanical strength |

Reddy et al. (2021) |

|

4. Cellulose Source: polysaccharide isolated from plants Chemical structure: polysaccharide chain made up of D-glucose units Properties: High stability, good mechanical strength, biocompatible, bioactivity, hydrophilic, low degradability, good shelf life |

Salmoria et al. (2009), Lovegrove et al. (2017) |

|

5. Hyaluronic acid (HA) Source: ECM glycosaminoglycan isolated from rooster combs or recombinant production Chemical structure: β-1,4-D glucuronic acid and β-1,3 N-acetyl-D-glucosamine Properties: biocompatible and bioactive |

Reddy et al. (2021) |

|

6. Pectin Source: structural polysaccharide isolated from primary cell wall and middle lamella of plants chiefly citrus and apple Chemical structure: acidic heteropolysaccharide consisting mainly of methoxy esterified α, d-1, 4-galacturonic acid units Properties: gel-forming property |

Zdunek et al. (2021) |

| Synthetic biopolymers | |

|

1. Polylactic acid (PLA) Source: synthesized by the direct polycondensation of lactic acid or by the ring-opening polymerization of lactide (LA), a cyclic dimer of lactic acid Chemical structure: crystalline Properties: biocompatible, thermally stable, good mechanical strength but high degradation rate, and hydrophobicity are the limiting factors |

Balla et al. (2021) |

|

2. Polyglycolic acid (PGA) Source: synthesized by the direct polycondensation of glycolic acid Chemical structure: crystalline aliphatic polyester Properties: biocompatible, hydrophilic but porosity is an issue with the PGA scaffold |

Zhang et al. (2018a, b) |

|

3. Poly-co-glycolic acid (PLGA) Source: PLA and PGA Chemical structure: co-polymer of PLA and PGA Properties: promotes cell adhesion and proliferation, good mechanical strength but biocompatibility restricts the usage of the PLGA scaffold as an edible scaffold |

Reddy et al. (2021) |

Hydrogels made of biopolymers like fibrin, collagen, or polysaccharides like HA, alginate, agarose, and chitosan, which are used for muscle cell tissue engineering, have also sparked the idea of developing hydrogels made of pre-synthesized ECM, polysaccharides, or fibrous proteins for in vitro meat production (Wolf et al. 2015; Ben-Arye and Levenberg 2019). In a pioneer study, Enrione and colleagues generated an edible scaffold employing non-mammalian biopolymers such as gelatin, alginate, agarose, and glycerol. They proposed that salmon gelatin acts as a functional macromolecule with RGD motifs that stimulates cell adhesion and proliferation; alginate acts as a cross-linker in contact with calcium; and agarose acts as a gelling agent (Enrione et al. 2017). Later, Orellana et al. used micromolding technology to generate a new microstructured scaffold film for growing myoblasts for in vitro meat production. They generated a microstructured template with an appropriate geometry (using the formulation of 1.2% salmon gelatin, 1.2% sodium alginate, 1% glycerol, and 0.2% agarose) that stimulated the parallel alignment of myoblasts seeded onto it, which is essentially required for muscle fiber formation (Orellana et al. 2020). In addition, mathematical simulation modeling (Diffusion and Moser) of microstructured film made up of gelatin, alginate, agarose, and plasticizers (Glycerol and Sorbitol) revealed that at high cell density, cell growth is slower due to low oxygen availability, but final biomass is higher, whereas sorbitol allows slightly faster growth than glycerol when compared to the same cell seeding number (Jaques et al. 2021).

Plant-based bioengineered edible scaffold structure

Besides the biopolymers, affordable and plant-based components such as plant leaves and recombinant proteins, as well as animal-free source of growth factors and enzymes, have been proposed as an excellent source for fabrication of edible scaffold (Ben-Arye and Levenberg 2019; Young and Skrivergaard 2020). Furthermore, only a few studies have reported the generation of edible scaffolds for in vitro meat production employing plant-derived soy protein and decellularized spinach leaves. Furthermore, recombinant protein biopolymers obtained from transgenic plants, such as collagen and elastin, have been used in numerous tissue engineering applications and have thus been proposed as a possible material for edible scaffold formation (Werkmeister et al. 2012). A number of reported biomaterials including biopolymers and plant contents used for the generation of bioengineered edible scaffold along their associated advantages are represented in Fig. 4.

Fig. 4.

Biomaterials used for scaffold formation and their associated advantages

Ben-Arye et al. developed a bovine muscle tissue on an edible scaffold comprised of TSP, a porous byproduct of soybean oil production. TSP is considered as a potential scaffold for the generation of in vitro meat due to its texture and high protein content. TSP provides anchoring locations and a network of interconnected pores for cell adhesion, growth, spread, and maturation of grown myoblasts, while the larger pores provide nutritional value and oxygen delivery to developing muscle tissue (Ben-Arye et al. 2020). Additionally, efforts have been undertaken to construct edible scaffolds that are low-cost, accessible, and easily scaled-up. Moreover, Jones and colleagues reported the fabrication of decellularized spinach leaves-based scaffold by immersion method (Fontana et al. 2017) which was used for the cultivation of bovine muscle tissue. Thus, decellularized leaves-based scaffold offers a cost-effective and eco-friendly approach for generation of vascularized scaffold for in vitro meat production (Jones et al. 2021).

Designing and formulation of bioengineered scaffold for in vitro meat production

A scaffold designing strategy is used in the pre-fabrication stage, which includes the selection of scaffold material and the optimization of appropriate formulation. However, an ideal design strategy takes into account a number of parameters, including the physical properties of the scaffold, such as porosity, water absorption, cell adhesion capabilities, and biocompatibility, as well as cost and degradation profile.

Key physical properties of the bioengineered scaffold

The edible scaffold utilized in in vitro meat production must be durable, biocompatible, have an appropriate microstructure, and physical properties necessary for cell attachment and proliferation (Acevedo et al. 2015). Furthermore, for muscle cell culture and in vitro meat production, selection of soft porous scaffold materials with an appropriate microstructure and stiffness is critical (Vijayavenkataraman et al. 2017). Key physical properties of scaffolds and their role in in vitro meat synthesis are presented in Table 2. The zeta potential measurement of a dilute aqueous solution was used to assess the stability of the ionic component of scaffold precursors, namely gelatin and alginate in gelatin: alginate scaffold.

Table 2.

Key physical properties of scaffolds and their role for in vitro meat production

| Physical properties | Role for in vitro meat production |

|---|---|

| Stability of biopolymer solution | Structural integrity |

| Biocompatibility | Muscle cell adhesion and growth |

| Scaffold–water interaction | Structural stability and cytocompatibility |

| Porosity | Muscle cell growth and nutrient and oxygen supply |

| Stiffness | Muscle cell adherence and proliferation |

| Mechanical strength | Muscle cell content and texture |

| Biodegradation | Scaffold integrity and shelf life |

It is claimed that a gelatin and alginate ratio of 7:3 and, ideally, 6:4 gives the scaffold with great colloidal stability (Enrione et al. 2017). The biocompatibility of the scaffold is also determined by measuring the viable myoblast’s cell adhesion and growth. Plasticizers such as glycerol and sorbitol are included in the scaffold formulation to promote cell adhesion and offer structural stability. The water-scaffold interaction, which is determined by measuring the moisture content and water uptake ratios of the scaffold, is particularly important for the scaffold’s biocompatibility. In comparison to a scaffold made up of agar as a gelling agent, a scaffold constructed of agarose as a gelling agent has a superior water interaction capacity (Enrione et al. 2017).

Furthermore, the scaffold microstructure influences various physical properties such as stiffness, pore size, and scaffold–water interaction, all of which influence myoblast growth. The gelling agents and plasticizers play a major role in the scaffold’s microstructure. It has been demonstrated that adding the gelling agent agarose and the food-grade plasticizer glycerol to the scaffold formulation results in a more stable scaffold with fewer micro-holes (Enrione et al. 2017). Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) of edible scaffolds offers detailed information about the surface microstructure, such as pore size distribution and directionality (Ben-Arye et al. 2020).

Cost and degradation profile of bioengineered scaffold

In vitro meat must be competitive with commodity meat prices in order to gain significant market share. However, the cost of lab-grown meat is a significant obstacle that must be overcome. In fact, given the difficulties connected with the bioprocess, it is reasonable to predict that scaffolding will contribute only a small portion of the overall manufacturing cost, possibly 5% (Bomkamp et al. 2022). Recent advances in plant-based scaffold materials, such as decellularized leaves and apple peel, have shown promise as a cost-effective scaffold material for in vitro meat production.

Furthermore, the degradation profile of the scaffold is critical for in vitro meat synthesis. Scaffolds comprised of natural biopolymers and plant components typically decay more quickly than synthetic and composite scaffolds. In vitro meat scaffolds, on the other hand, must either be biodegradable or edible during the differentiation and maturation process (Seah et al. 2022). Furthermore, the scaffold and its breakdown products must be harmless even when taken on a daily basis, and they must not alter the flavor or texture of in vitro meat (Ramachandraiah et al. 2021). If the scaffold is left in the end product, its textural qualities should likewise imitate the ECM following the cooking process (Bomkamp et al. 2022).

Fabrication of bioengineered scaffold for in vitro meat production

In order to generate in vitro meat, a bioengineered edible scaffold with precise mechanical strength, physicochemical characteristics, biology, and surface properties are required (Seah et al. 2022). Various interdisciplinary research groups have developed and reported a number of fabrication techniques, primarily solvent casting and decellularization of plant leaves for the formation of edible scaffolds, while freeze-drying, electrospinning, and 3D printing have also been suggested as potential fabrication techniques (Deb et al. 2018; Seah et al. 2022).

Solvent casting

The simplest and most common method for scaffold synthesis is solvent casting, in which biopolymers are dissolved in an organic solvent, poured into a mold, and allowed to evaporate to form a thin sheet-like scaffold (Deb et al. 2018). The most commonly used organic solvent for food industry involves food-grade alcohol (Mancuso 2021). Acevedo and colleagues used a solvent casting method followed by freeze-drying to develop an edible scaffold using biopolymers like gelatin and alginate (Enrione et al. 2017; Orellana et al. 2020). Certain chemicals, such as glycerol, agarose, and others, are added to the polymeric solution to fabricate a scaffold with the desired microstructure (Murphy et al. 2010).

Decellularization of plant leaves

The lack of a functional vascular network in biopolymer-based edible scaffolds impacts the generation of 3D muscle tissues for in vitro meat production (Adamski et al. 2018). As a result, decellularized matrices are thought to form a morphological and biochemical milieu for growing cells, promoting cell adhesion, proliferation, and differentiation (Wu et al. 2015). The tissues are decellularized to provide an extracellular matrix with a maintained vascular network for nutrient and oxygen transport (Contessi et al. 2020). In addition, decellularized plant-based tissues display a naturally occurring fluidic transport system (which possesses plant vessels that diverge from large major veins into fine capillaries) similar to the branching vascular network in mammalian tissue (Harris et al. 2021). As a result, researchers have proposed and constructed edible scaffolds made from decellularized apple hypanthium and spinach leaves to avoid the issues associated with biopolymer-based edible scaffolds (Modulevsky et al. 2016; Jones et al. 2021). Decellularized plant tissue scaffolds are suitable for in vitro production because they not only provide a functional vascular network and the required morphological and biochemical microenvironment to growing muscle cells, but they are also cost-effective, environmentally friendly, easily scalable, and completely free of animal components (Jones et al. 2021).

Freeze drying

Furthermore, freeze-drying is a dehydration method in which a substance is frozen to an extremely low temperature, and then the surrounding pressure is reduced, causing the frozen water to sublime (Deb et al. 2018). The freeze-drying technique is being used extensively to produce porous scaffold, and the pore size and distribution of the structure is monitored by temperature, pressure, pH, freezing rate, and concentration of polymers (Lv et al. 2006; Deb et al. 2018; Seah et al. 2022). So far, the freeze-drying technique has been used for preparing the scaffold using synthetic non-edible and edible polymers which should be further investigated and replaced with plant and biopolymer-derived edible scaffold (Shit et al. 2014; Bomkamp et al. 2022).

Electrospinning

Electrospinning is an appealing technology since it forms a fibrous structure with fiber diameters ranging from 10 nm to microns, which could be used to make edible scaffolds for in vitro meat production (Seah et al. 2022). These nano-fibers have the ability to facilitate cell adhesion (to the fibers) and oxygen and nutrient diffusion (via the spaces between fibers), as well as form aligned fibers that may aid in muscle fiber development. For high-throughput screening, spinning techniques can be applied to a range of materials, including polylactic acid (PLA), poly (lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA), polycaprolactone (PCL), gelatin methacryloyl (GelMA), fibronectin, albumin, and gelatin (Bomkamp et al. 2022). Electrospinning of a combination of PCL and temperature-sensitive PNIPAAm hydrogel has been used to produce aligned cell sheets that can be detached from the scaffold by a change in temperature (Allen et al. 2017).

3D bioprinting

3D bioprinting is a new approach for tissue engineering that includes spraying hydrogels containing cellular and acellular components onto a printed scaffold, allowing for accurate cell placement and biomaterial placement to build complex 3D structures and shapes (Singh et al. 2020, Handral et al. 2022). Inkjet printing, extrusion printing, and light-assisted printing are also common bioprinting processes (Kacarevic et al. 2018). Extrusion printing, the most common bioprinting method, uses pneumatic pressure or a mechanical screw plunger to dispense bioink in the form of continuous filaments (fibers) rather than droplets. The extrusion bioprinters can also print with a variety of viscosities and have been suggested to be used with a variety of materials (Zhang et al. 2017).

Extrusion printers include numerous printer heads that allow multiple bioinks to be imprinted at the same time. Furthermore, customizable forms, pores, porosity, and cell distribution can all be controlled precisely. All of these benefits have contributed to extrusion bioprinting becoming the most extensively utilized technology in recent years (Placone and Engler 2018). 3D bioprinting technology could be useful for both small-scale and large-scale production of customized cultured meat (Stephens et al. 2019). Bioink, which is made up of biomaterials, is a crucial part of the printing process because it fabricates scaffold structures for the formation of muscle fibers that will eventually become meat (Bishop et al. 2017; Sun et al. 2018). In addition, the printed scaffold provides a niche and micro-milieu for the grown muscle cells, which are typically matured in bioreactors that allow large-scale nutrition transport (Zhang et al. 2018a, b; Bishop et al. 2017).

In vitro meat production: cultivation of myoblast cells onto bioengineered scaffold

In vitro meat production necessitates optimizing culture conditions for myoblast growth on bioengineered scaffolds, as well as scaling up in vitro meat production using bioengineered scaffolds.

Culture condition for myoblast cultivation on scaffold

Various research groups optimized the culture conditions for growing the myoblast onto the scaffold to examine the scaffold’s potential to produce the in vitro meat. Enrione et al. seeded 1 × 105 cells/cm2 myoblast cells onto the gelatin: alginate scaffold and cultivated them for 2 days in DMEM growth media supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), L-glutamine, and antibiotics. Scaffolds were then fixed in Bouin’s solution for 24 h at 5 °C to examine cell morphology and distribution utilizing histochemical trichrome stains (Enrione et al. 2017). Ben-Arye et al. also seeded bovine muscle stem cells, i.e., satellite cells and smooth muscle cells suspended in thrombin and fibrinogen, onto a TSP scaffold and incubated them for 30 min in a CO2 atmosphere to allow the fibrin to gel. After that, the TSP scaffold was filled with bovine satellite cell proliferation and differentiation media, which was replenished on alternate days (Ben-Arye et al. 2020). Jones et al. also seeded 2 × 105 bovine satellite cells onto decellularized spinach leaves and cultured them for 14 days in DMEM/F12 media supplemented with 10% FBS, fibroblast growth factor-2, hepatocyte growth factor, epidermal growth factor, and insulin growth factor, with cell viability determined after 14 days (Jones et al. 2021). All of the above-mentioned fabricated scaffolds used in various studies have shown compatibility with seeded myoblasts, implying their potential for in vitro meat up-scaling by using bioreactors.

Up-scaling of in vitro meat production using bioengineered scaffold

Bioreactor-based up-scaling of antibody, vaccines, recombinant proteins, and biologics has demonstrated that bioreactors are effective in maintaining cell viability and functionality under controlled physiological conditions, and thus, similar concepts could be applied to up-scaling of cultured meat products using bioengineered scaffolds (Specht et al. 2018). Bioreactors are necessary for 3D dynamic culturing, which allows cells to expand, differentiate, and self-assemble (Seah et al. 2022). It has been suggested that scaffold design, form and their sources are the key factors of the bioprocess design as it exert direct impact on bioreactor seeding efficiency, passaging requirements of the system, downstream processing, bioreactor fluid dynamics and mass transfer, and cost (Allan et al. 2019).

Bioreactors for in vitro production should be designed with a significantly larger throughput capability than those now employed for biomedical purposes, which are low volume and high value (Zhang et al. 2020). Various bioreactors including tissue perfusion, continuous stirred tank, rocking platform, and vertical wheel bioreactors are commonly used for growing and providing the nutrient support to the cells in order to from the 3D tissue. Rocking platform bioreactors and vertical wheel bioreactors produce comparable cell growth but at a smaller scale, while continuous stirred tanks provide long-term sterility by mechanical stirring, maintain a high level of oxygen transmission, and prevent bubbling over air-lift reactors, making them ideal for up-scaling animal cell culture (Allan et al. 2019). Van Eelen’s team previously filed a patent for industrial-scale meat production using in vitro cell cultures, claiming that adult satellite cells may be cultured on collagen meshwork or microcarrier beads in a stationary or rotating bioreactor (Van Eelen et al. 1999). Furthermore, recent advancements in tissue perfusion bioreactors for bone tissue engineering have sparked the concept of adapting them for large-scale in vitro meat production (Seah et al. 2022).

Future perspective of bioengineered scaffolds

Since 2013, when Dr. Mark Post reported the first cultured meat hamburger, in vitro meat technology has rapidly evolved and gone through various stages (Post 2014). However, the majority of the challenges associated with in vitro meat are the production costs and the impartation of sensory properties such as texture, taste, and nutritional value similar to conventional meat. Further investigation and research in the field of edible scaffolds could help to alleviate some of these issues. Other natural biopolymers and proteins, such as chitosan, HA, and fibrin, could be useful in promoting myotube proliferation and improving the sensory properties of in vitro meat.

Chemically modified chitosan, on the other hand, could be used for edible scaffold formation because its functional group promotes cell adhesion and biodegradability (Huang et al. 2017). Furthermore, because HA hydrogels are synthesized in animal-free platforms and have favorable viscoelastic properties, cell compatibility, and high water-retention capability, ECM polysaccharide HA is a potential scaffold material (Sze et al. 2016). Aside from the edible scaffold, a plant-derived biomaterial-based microcarrier cell scaffold could be used for large-scale in vitro meat production. Microcarrier scaffolds are small bead-like structures (100–400 m in diameter) which mimic the properties of the ECM and thus, promote cell attachment (McKee and Chaudhry 2017). However, advancement in intramuscular fat tissue engineering or the generation of novel flavor-enhancing scaffolds applying the tools of food engineering and meat science will offer enormous research opportunities towards the development of efficient edible scaffold for in vitro meat production.

Conclusion

In vitro meat appears to be a present-day and future-demand necessity, as conventional meat production and consumption are associated with a variety of human and environmental health issues. An important amount of research has been done in the last decade to generate the cost-effective, eco-friendly, disease-free, and nutritive in vitro meat. However, tissue engineering was used to fabricate an edible scaffold, which remained an important part of in vitro meat production. Edible scaffolds made from biomaterials are designed to mimic the texture and connective tissues of muscle. Previous research activities laid the groundwork for further investigation of biopolymers such as gelatin, alginate, agarose, and others, as well as plant-derived components such as soy-textured protein and decellularized leaves, for the fabrication of edible scaffolds for in vitro meat production. These edible scaffolds were discovered to increase myotube proliferation and adherence, and thus, they have been proposed as potential scaffolds for in vitro meat production. Further research and exploration of new biopolymers and proteins would result in the development of cost-effective, easily scalable, and environmentally friendly edible scaffolds.

Funding

This work is supported by the DST-SERB under grant EEQ/2018/000114.

Data availability

The authors confirm that the data mentioned in this study are available within the cited article.

Declarations

Ethical approval

Not applicable.

Informed consent

Not applicable.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Acevedo CA, Díaz-Calderón P, Enrione J, Caneo MJ, Palacios CF, Weinstein-Oppenheimer C, Brown DI. Improvement of biomaterials used in tissue engineering by an ageing treatment. Bioprocess Biosyst Eng. 2015;38:777–785. doi: 10.1007/s00449-014-1319-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Acevedo CA, López DA, Tapia MJ, Enrione J, Skurtys O, Pedreschi F, Brown DI, Creixell W, Osorio F. Using RGB image processing for designing an alginate edible film. Food Bioproc Tech. 2012;5:1511–1520. doi: 10.1007/s11947-010-0453-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Adamski M, Fontana G, Gershlak JR, Gaudette GR, Le HD, Murphy WL. Two methods for decellularization of plant tissues for tissue engineering applications. J vis Exp. 2018;135:e57586. doi: 10.3791/57586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allan SJ, De Bank PA, Ellis MJ. Bioprocess design considerations for cultured meat production with a focus on the expansion bioreactor. Front Sustain Food Syst. 2019;3:44. doi: 10.3389/fsufs.2019.00044. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Allen AC, Barone E, Cody O, Crosby K, Suggs LJ, Zoldan J. Electrospun poly (N-isopropyl acrylamide)/poly (caprolactone) fibers for the generation of anisotropic cell sheets. Biomater Sci. 2017;5:1661–1669. doi: 10.1039/C7BM00324B. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asti A, Gioglio L (2014) Natural and synthetic biodegradable polymers: different scaffolds for cell expansion and tissue formation. Int J Artif Organs 37:187-205 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Balla E, Daniilidis V, Karlioti G, Kalamas T, Stefanidou M, Bikiaris ND, Vlachopoulos A, Koumentako I, Bikiaris DN. Poly (lactic Acid): a versatile biobased polymer for the future with multifunctional properties—from monomer synthesis, polymerization techniques and molecular weight increase to PLA applications. Polymers. 2021;13:1822. doi: 10.3390/polym13111822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Arye T, Levenberg S. Tissue engineering for clean meat production. Front Sustain Food Syst. 2019;3:46. doi: 10.3389/fsufs.2019.00046. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Arye T, Shandalov Y, Ben-Shaul S, Landau S, Zagury Y, Ianovici I, Lavon N, Levenberg S. Textured soy protein scaffolds enable the generation of three-dimensional bovine skeletal muscle tissue for cell-based meat. Nat Food. 2020;1:210–220. doi: 10.1038/s43016-020-0046-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bishop ES, Mostafa S, Pakvasa M, Luu HH, Lee MJ, Wolf JM, Ameer GA, He TC, Reid RR. 3-D bioprinting technologies in tissue engineering and regenerative medicine: current and future trends. Genes Dis. 2017;4:185–195. doi: 10.1016/j.gendis.2017.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolívar-Monsalve EJ, Alvarez MM, Hosseini S, Espinosa-Hernandez MA, Ceballos-González CF, Sanchez-Dominguez M, Shin SR, Cecen B, Hassan S, Di Maio E, Trujillo-de Santiago G. Engineering bioactive synthetic polymers for biomedical applications: a review with emphasis on tissue engineering and controlled release. Mater Adv. 2021;2:4447. doi: 10.1039/D1MA00092F. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bomkamp C, Skaalure SC, Fernando GF, Ben-Arye T, Swartz EW, Specht EA. Scaffolding biomaterials for 3D cultivated meat: prospects and challenges. Adv Sci. 2022;9:2102908. doi: 10.1002/advs.202102908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campuzano S, Pelling AE. Scaffolds for 3D cell culture and cellular agriculture applications derived from non-animal sources. Front Sustain Food Syst. 2019;3:38. doi: 10.3389/fsufs.2019.00038. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carletti E, Motta A, Migliaresi C. Scaffolds for tissue engineering and 3D cell culture. Methods Mol Bio. 2011 doi: 10.1007/978-1-60761-984-0_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Contessi Negrini N, Toffoletto N, Farè S, Altomare L. Plant tissues as 3D natural scaffolds for adipose, bone and tendon tissue regeneration. Front Bioeng Biotechnol. 2020;2020:723. doi: 10.3389/fbioe.2020.00723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deb P, Deoghare AB, Borah A, Barua E, Lala SD. Scaffold development using biomaterials: a review. Mater Today Proc. 2018;5:12909–12919. doi: 10.1016/j.matpr.2018.02.276. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- del Carmen O-C, García-López M, Cerrada V, Gallardo ME. iPSCs: A powerful tool for skeletal muscle tissue engineering. J Cell Mol Med. 2019;23:3784–3794. doi: 10.1111/jcmm.14292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drury JL, Mooney DJ. Hydrogels for tissue engineering: scaffold design variables and applications. Biomaterials. 2003;24:4337–4351. doi: 10.1016/S0142-9612(03)00340-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elieh-Ali-Komi D, Hamblin MR. Chitin and chitosan: production and application of versatile biomedical nanomaterials. Int J Adv Res. 2016;4:411. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enrione J, Blaker JJ, Brown DI, Weinstein-Oppenheimer CR, Pepczynska M, Olguín Y, Sánchez E, Acevedo CA. Edible scaffolds based on non-mammalian biopolymers for myoblast growth. Materials. 2017;10:1404. doi: 10.3390/ma10121404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Etemadi A, Sinha R, Ward MH, Graubard BI, Inoue-Choi M, Dawsey SM, Abnet CC. Mortality from different causes associated with meat, heme iron, nitrates, and nitrites in the NIH-AARP Diet and Health Study: population-based cohort study. BMJ. 2017;357:j1957. doi: 10.1136/bmj.j1957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farokhi M, Jonidi Shariatzadeh F, Solouk A, Mirzadeh H. Alginate based scaffolds for cartilage tissue engineering: a review. Int J Polym Mater Polym Biomater. 2020;69:230–247. doi: 10.1080/00914037.2018.1562924. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Felfel RM, Gideon-Adeniyi MJ, Zakir Hossain KM, Roberts GAF, Grant DM. Structural, mechanical and swelling characteristics of 3D scaffolds from chitosan-agarose blends. Carbohydr Polym. 2019;204:59–67. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2018.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feroz S, Muhammad N, Ratnayake J, Dias G. Keratin-based materials for biomedical applications. Bioact Mater. 2020;5:496–509. doi: 10.1016/j.bioactmat.2020.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris AF, Lacombe J, Zenhausern F (2021) The emerging role of decellularized plant-based scaffolds as a new biomaterial. Int J Mol Sci 22:12347 10.3390/ijms222212347 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Jaques A, Sánchez E, Orellana N, Enrione J, Acevedo CA. Modelling the growth of in-vitro meat on microstructured edible films. J Food Eng. 2021;307:110662. doi: 10.1016/j.jfoodeng.2021.110662. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fontana G, Gershlak J, Adamski M, Lee JS, Matsumoto S, Le HD, Binder B, Wirth J, Gaudette G, Murphy WL. Biofunctionalized plants as diverse biomaterials for human cell culture. Adv Healthc Mater. 2017;6:1601225. doi: 10.1002/adhm.201601225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman FE, Kelly DJ. Tuning alginate bioink stiffness and composition for controlled growth factor delivery and to spatially direct MSC fate within bioprinted tissues. Sci Rep. 2017;7:1–2. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-17286-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gandaglia A, Huerta-Cantillo R, Comisso M, Danesin R, Ghezzo F, Naso F, Gastaldello A, Schittullo E, Buratto E, Spina M, Gerosa G. Cardiomyocytes in vitro adhesion is actively influenced by biomimetic synthetic peptides for cardiac tissue engineering. Tissue Eng Part A. 2012;18:725–736. doi: 10.1089/ten.TEA.2011.0254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillies AR, Lieber RL. Structure and function of the skeletal muscle extracellular matrix. Muscle Nerve. 2011;44:318–331. doi: 10.1002/mus.22094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Handral HK, Hua Tay S, Wan Chan W, Choudhury D. 3D printing of cultured meat products. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2022;62:272–281. doi: 10.1080/10408398.2020.1815172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong TK, Shin DM, Choi J, Do JT, Han SG. Current issues and technical advances in cultured meat production: a review. Food Sci Anim Resour. 2021;41:355. doi: 10.5851/kosfa.2021.e14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang G, Li F, Zhao X, Ma Y, Li Y, Lin M, Jin G, Lu TJ, Genin GM, Xu F. Functional and biomimetic materials for engineering of the three-dimensional cell microenvironment. Chem Rev. 2017;117:12764–12850. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.7b00094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang J, Huang K, You X, Liu G, Hollett G, Kang Y, Gu Z, Wu J. Evaluation of tofu as a potential tissue engineering scaffold. J Mater Chem B. 2018;6:1328–1334. doi: 10.1039/c7tb02852k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones JD, Rebello AS, Gaudette GR. Decellularized spinach: an edible scaffold for laboratory-grown meat. Food Biosci. 2021;41:100986. doi: 10.1016/j.fbio.2021.100986. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kačarević ŽP, Rider PM, Alkildani S, Retnasingh S, Smeets R, Jung O, Ivanišević Z, Barbeck M. An introduction to 3D bioprinting: possibilities, challenges and future aspects. Materials. 2018;11:2199. doi: 10.3390/ma11112199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim YS, Ok YJ, Hwang SY, Kwak JY, Yoon S (2019) Marine collagen as a promising biomaterial for biomedical applications. Mar Drugs 17:467 10.3390/md17080467 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Liu S, Lau CS, Liang K, Wen F, Teoh SH (2022) Marine collagen scaffolds in tissue engineering. Curr Opin Biotechnol 74:92–103 10.1016/j.copbio.2021.10.011 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Lovegrove A, Edwards CH, De Noni I, Patel H, El SN, Grassby T, Zielke C, Ulmius M, Nilsson L, Butterworth PJ, Ellis PR, Role of polysaccharides in food, digestion, and health. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2017;57:237–253. doi: 10.1080/10408398.2014.939263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lv Q, Feng Q. Preparation of 3-D regenerated fibroin scaffolds with freeze drying method and freeze drying/foaming technique. J Mater Sci Mater Med. 2006;17:1349–1356. doi: 10.1007/s10856-006-0610-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marga FS, Purcell BP, Forgacs G, Forgacs A (2017) Inventors; Modern Meadow Inc, assignee. Edible and animal-product-free microcarriers for engineered meat. United States patent US 9,752,122

- McKee C, Chaudhry GR. Advances and challenges in stem cell culture. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces. 2017;159:62–77. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2017.07.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Modulevsky DJ, Cuerrier CM, Pelling AE. Biocompatibility of subcutaneously implanted plant-derived cellulose biomaterials. PLoS ONE. 2016;11:e0157894. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0157894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy CM, Haugh MG, O'brien FJ, The effect of mean pore size on cell attachment, proliferation and migration in collagen–glycosaminoglycan scaffolds for bone tissue engineering. Biomaterials. 2010;31:461–466. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.09.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mancuso J (2021) What are food grade solvents. Accessed: https://ecolink.com/info/what-are-food-grade-solvents/. Accessed on 24th August 2022

- Orellana N, Sánchez E, Benavente D, Prieto P, Enrione J, Acevedo CA. A new edible film to produce in vitro meat. Foods. 2020;9:185. doi: 10.3390/foods9020185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Odegard I, Sinke P (2021) LCA of cultivated meat. Future projections for different scenarios. CE Delft 2021 Feb:22–55

- Placone JK, Engler AJ. Recent advances in extrusion-based 3D printing for biomedical applications. Adv Healthc Mater. 2018;7:1701161. doi: 10.1002/adhm.201701161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Post MJ. An alternative animal protein source: cultured beef. Ann. N.Y. Acad Sci. 2014;1328:29–33. doi: 10.1111/nyas.12569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qian F, Riddle MC, Wylie-Rosett J, Hu FB. Red and processed meats and health risks: how strong is the evidence? Diabetes Care. 2020;43:265–271. doi: 10.2337/dci19-0063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahman MA. Collagen of extracellular matrix from marine invertebrates and its medical applications. Mar Drugs. 2019;17:118. doi: 10.3390/md17020118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramachandraiah K. Potential development of sustainable 3d-printed meat anlogues: a review. Sustainability. 2021;13:938. doi: 10.3390/su13020938. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Reddy M, Ponnamma D, Choudhary R, Sadasivuni KK. A comparative review of natural and synthetic biopolymer composite scaffolds. Polymers. 2021;13:1105. doi: 10.3390/polym13071105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosales AM, Anseth KS. The design of reversible hydrogels to capture extracellular matrix dynamics. Nat Rev Mater. 2016;1:1–5. doi: 10.1038/natrevmats.2015.12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rouse JG, Van Dyke ME. A review of keratin-based biomaterials for biomedical applications. Materials. 2010;3:999–1014. doi: 10.3390/ma3020999. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Salmoria GV, Klauss P, Paggi RA, Kanis LA, Lago A. Structure and mechanical properties of cellulose based scaffolds fabricated by selective laser sintering. Polym Test. 2009;28:648–652. doi: 10.1016/j.polymertesting.2009.05.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Seah JS, Singh S, Tan LP, Choudhury D. Scaffolds for the manufacture of cultured meat. Crit Rev Biotechnol. 2022;42:311–323. doi: 10.1080/07388551.2021.1931803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shit SC, Shah PM. Edible polymers: challenges and opportunities. Journal of Polymers. 2014;2014:1–13. doi: 10.1155/2014/427259. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Singh A, Verma V, Kumar M, Kumar A, Sarma DK, Singh B, Jha R. Stem cells-derived in vitro meat: from petri dish to dinner plate. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2020;30:1–4. doi: 10.1080/10408398.2020.1856036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh A, Yadav CB, Tabassum N, Bajpeyee AK, Verma V. Stem cell niche: dynamic neighbor of stem cells. Eur J Cell Biol. 2019;98:65–73. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcb.2018.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Specht EA, Welch DR, Clayton EM, Lagally CD. Opportunities for applying biomedical production and manufacturing methods to the development of the clean meat industry. Biochem Eng J. 2018;132:161–168. doi: 10.1016/j.bej.2018.01.015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stephens N, Sexton AE, Driessen C. Making sense of making meat: key moments in the first 20 years of tissue engineering muscle to make food. Front Sustain Food System. 2019;2019:45. doi: 10.3389/fsufs.2019.00045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun J, Zhou W, Yan L, Huang D, Lin LY. Extrusion-based food printing for digitalized food design and nutrition control. J Food Eng. 2018;220:1–1. doi: 10.1016/j.jfoodeng.2017.02.028. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sze JH, Brownlie JC, Love CA (2016) Biotechnological production of hyaluronic acid: a mini review. 3 Biotech 6:1–9 10.1007/s13205-016-0379-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Tallawi M, Rosellini E, Barbani N, Cascone MG, Rai R, Saint-Pierre G, Boccaccini AR. Strategies for the chemical and biological functionalization of scaffolds for cardiac tissue engineering: a review. J R Soc Inter. 2015;12:20150254. doi: 10.1098/rsif.2015.0254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tibbitt MW, Anseth KS. Hydrogels as extracellular matrix mimics for 3D cell culture. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2009;103:655–663. doi: 10.1002/bit.22361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tiburcy M, Markov A, Kraemer LK, Christalla P, Rave-Fraenk M, Fischer HJ, Reichardt HM, Zimmermann WH. Regeneration competent satellite cell niches in rat engineered skeletal muscle. FASEB BioAdvances. 2019;1:731–746. doi: 10.1096/fba.2019-00013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Der Weele C, Driessen C. How normal meat becomes stranger as cultured meat becomes more normal; ambivalence and ambiguity below the surface of behavior. Front Sustain Food Syst. 2019;3:69. doi: 10.3389/fsufs.2019.00069. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Van Eelen WF, Willem JVK, Wiete W (1999) Industrial scale production of meat from in vitro cell cultures. WO/1999/031222. World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO) - Patent Cooperation Treaty (PCT). https://patentscope.wipo.int/search/en/detail.jsf?docId=WO1999031222

- Verma V, Huang B, Kallingappa PK, Oback B. Dual kinase inhibition promotes pluripotency in finite bovine embryonic cell lines. Stem Cells Dev. 2013;22:1728–1742. doi: 10.1089/scd.2012.0481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vijayavenkataraman S, Shuo Z, Fuh JY, Lu WF. Design of three-dimensional scaffolds with tunable matrix stiffness for directing stem cell lineage specification: an in silico study. Bioengineering. 2017;4:66. doi: 10.3390/bioengineering4030066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werkmeister JA, Ramshaw JA. Recombinant protein scaffolds for tissue engineering. Biomed Mater. 2012;7:012002. doi: 10.1088/1748-6041/7/1/012002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolf MT, Dearth CL, Sonnenberg SB, Loboa EG, Badylak SF. Naturally derived and synthetic scaffolds for skeletal muscle reconstruction. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2015;84:208–221. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2014.08.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu SC, Chang WH, Dong GC, Chen KY, Chen YS, Yao CH (2011) Cell adhesion and proliferation enhancement by gelatin nanofiber scaffolds. J Bioact Compat Polym 26:565–577 10.1177/0883911511423563

- Wu X, Wang Y, Wu Q, Li Y, Li L, Tang J, Shi Y, Bu H, Bao J, Xie M. Genipin-crosslinked, immunogen-reduced decellularized porcine liver scaffold for bioengineered hepatic tissue. Tissue Eng Regen Med. 2015;12:417–426. doi: 10.1007/s13770-015-0006-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yegappan R, Selvaprithiviraj V, Amirthalingam S, Jayakumar R. Carrageenan based hydrogels for drug delivery, tissue engineering and wound healing. Carbohydr Polym. 2018;198:385–400. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2018.06.086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young JF, Skrivergaard S. Cultured meat on a plant-based frame. Nat Food. 2020;1:195. doi: 10.1038/S43016-020-0053-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zdunek A, Pieczywek PM, Cybulska J (2021) The primary, secondary, and structures of higher levels of pectin polysaccharides. Compr Rev Food Sci Food Saf 20:1101–1117 10.1111/1541-4337.12689 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Zeltinger J, Sherwood JK, Graham DA, Müeller R, Griffith LG. Effect of pore size and void fraction on cellular adhesion, proliferation, and matrix deposition. Tissue Eng. 2001;7:557–572. doi: 10.1089/107632701753213183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang G, Zhao X, Li X, Du G, Zhou J, Chen J. Challenges and possibilities for bio-manufacturing cultured meat. Trends Food Sci Technol. 2020;97:443–450. doi: 10.1016/j.tifs.2020.01.026. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J, Yang S, Yang X, Xi Z, Zhao L, Cen L, Lu E, Yang Y. Novel fabricating process for porous polyglycolic acid scaffolds by melt-foaming using supercritical carbon dioxide. ACS Biomater Sci Eng. 2018;4:694–706. doi: 10.1021/acsbiomaterials.7b00692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang YS, Oklu R, Dokmeci MR, Khademhosseini A. Three-dimensional bioprinting strategies for tissue engineering. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2018;8:a025718. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a025718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang YS, Yue K, Aleman J, Mollazadeh-Moghaddam K, Bakht SM, Yang J, Jia W, Dell’Erba V, Assawes P, Shin SR, Dokmeci MR. 3D bioprinting for tissue and organ fabrication. Ann Biomed Eng. 2017;45:148–163. doi: 10.1007/s10439-016-1612-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu J, Marchant RE. Design properties of hydrogel tissue-engineering scaffolds. Expert Rev Med Devices. 2011;8:607–626. doi: 10.1002/bit.22361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The authors confirm that the data mentioned in this study are available within the cited article.