Abstract

The COVID-19 pandemic has caused many businesses and organizations to implement changes to manage operational and economic challenges. Understanding how employees manage such changes during the process is critical to the success of organizations. Integrating the literature from transparent internal communication, the transactional theory of stress and coping, and organizational change research, this study proposes a theoretical model to understand the role of internal communication and its effects on employees’ management of organizational change. An online survey was conducted with 490 full-time employees in the U.S. during the second and third weeks of April 2020. The findings of this study demonstrate that transparent internal communication can help encourage problem-focused control coping, reduce uncertainty, and foster employee-organization relationships during organizational change. Theoretical and practical implications are discussed.

Keywords: Internal communication, Change communication, Uncertainty reduction, Coping, Employee-Organization-Relationship

1. Introduction

The 2019 Novel Coronavirus (COVID-19), an influenza pandemic that is thought to have originated in China as early as December 2019, reached the United States in January 2020, and has been widespread in the nation since then (World Health Organization, 2020). The pandemic has radically disrupted not only individuals’ daily life routine but also the way workplace functions (Centers for Disease & Control Prevention, 2020). The sudden rise of the pandemic resulted in economic ripple effects, causing a significant increase in the unemployment rate, large-scale changes to organizations’ business operation, and substantial modifications to work and management styles (Johns Hopkins University, 2020). As of April 2020, the unemployment rate in the U.S. was 14.7 %, with 23.1 million unemployed and reached the highest unemployment rate in history (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2020). Moreover, the pandemic has accelerated the digital transformation of organizations, increased organizational use of temporary and part-time workers, changed work tasks for new product development, and led to an urgent need for frequent and quality communication between organizational management and employees (Connley, Hess, & Liu, 2020). When facing these unprecedented challenges, organizations have to adapt to improve their external and internal functioning in ways such as adjusting their business continuity plans, altering strategies and policies to manage the workforce, and downsizing (APQC (American Productivity & Quality Center), 2020).

To successfully implement changes and minimize the negative consequences of such changes, a deep understanding of employees’ attitudes and behaviors toward the changes is critical (Shin, Taylor, & Seo, 2012). Organizational change, unplanned change in particular, can cause many issues and lead to questions and uncertainties for employees, which may affect their relationships with the organizations. Negative feedback and reactions to organizational change include resistance, resentment, and disengagement from employees and may inhibit the success of organizational change implementation (Oreg, Bartunek, Lee, & Do, 2018).

Communication with employees during change has long been recognized as a fundamental determinant of how change is understood, interpreted, and managed by employees (Barrett, 2002; Johansson & Heide, 2008). Although the indispensability of communication has been well recognized in organizational change literature, what is less clear is the specific role that strategic internal communication plays in facilitating employees’ ability to manage the change (Yue, Men, & Ferguson, 2019), particularly during unplanned changes characterized by a high degree of anxiety, uncertainty, and urgency (i.e., COVID-19 in this study). The mechanism by which strategic internal communication works to facilitate employees’ coping with unplanned change events warrants attention from public relations scholars and practitioners who are tasked with maintaining positive employee morale and organization-employee relationships during turbulent times. A deep understanding of such a mechanism can help organizations better communicate with employees and promote effective coping among them.

To fill the gap, this study integrates internal communication and relationship management frameworks in public relations research, uncertainty management theory, and the transactional theory of stress and coping from organizational psychology literature. With the interdisciplinary perspective, this study seeks to understand how strategic internal communication efforts, specifically transparent communication, facilitate employees’ coping strategy adoption and uncertainty reduction during unplanned organizational change. More importantly, it aims to uncover the underlying psychological mechanism that drives the effectiveness of transparent communication in fostering favorable organization-employee relationships during unplanned change events. Toward these purposes, the present study conducts an online survey among 490 full-time employees during the COVID-19 outbreak.

Through an interdisciplinary perspective, the results of this study further the much-needed theoretical understanding of how employees cope with unplanned organizational change, especially when their organizations face an unprecedented public health crisis. This study advances our knowledge of how strategic internal communication facilitates the success of crisis-induced change management. Because it is difficult for organizations to successfully implement changes without knowing how internal communication affects employees’ reactions to organizational changes, this study also provides important practical implications.

2. Literature review

2.1. Managing organizational change: transparent internal communication practice

Organizational change refers to the process in which an organization changes its existing structure, work routines, strategies, or culture that may significantly affect the organization (Herold, Fedor, Caldwell, & Liu, 2008). Such change can be either planned or unplanned, depending upon the specific force that triggers the change and the purpose of the change (Malopinsky & Osman, 2006). Planned change occurs when the analysis of business operations reveals problems that require immediate improvement. The systematic and controlled change, such as product innovation and business structure modification, helps organizations proactively improve their performance and effectiveness (Stolovitch & Keeps, 1992). By contrast, unplanned change is oftentimes imposed by unexpected external forces rather than proactively initiated by the organization itself. Such change occurs serendipitously due to a problematic situation in organizational environments that may disrupt the organization’s operations and/or threaten its reputation (Shaw, 2018). Thus, it requires organizations to react quickly and strategically (Shaw, 2018). The main goal of such unplanned change is to minizine negative impacts of the problematic situation, maximize potential benefits, and transform the situation/crisis into an opportunity (Schermerhorn, Osborn, & Hunt, 2003). Organizations adopt changes, such as downsizing or relocating, allowing their operation systems and involved stakeholders to adapt to new situations (Seeger, Ulmer, Novak, & Sellnow, 2005). However, the lack of adequate time, preparation, flexibility, and communication may form barriers to such changes and thus pose threats to the organizations (Meaney & Pung, 2008). These unplanned changes that involve spontaneous adjustments to the central operation system of an organization trigger a series of novel events, possibly exposing stakeholders, particularly employees, to uncertainty, threats, or even harm (Rafferty & Griffin, 2006). Therefore, how employees make sense of and respond to the unexpected changes is essential to the success of unplanned change implementation (Shin et al., 2012).

In the face of change, the surprise, uncertainty, and confusion lead individuals to undergo a sensemaking process. They attempt to gather information to construe meanings of the change, develop a rationale for the change, and decide how they should respond to such change (Weick, 1995; Weick, Sutcliffe, & Obstfeld, 2005). As this sensemaking process involves collecting, interpreting, and evaluating information, quality communication during organizational change has been determined to be crucial in helping employees cope with the change and its uncertainty (Lewis & Sahay, 2018). To overcome resistance, reduce uncertainty, and help employees embrace the change, scholars suggested that organizations must communicate with their employees about the need for change, the process of the change, and the subsequent impacts of the change (Elving, 2005). Such communication should be frequent, authentic, and enthusiastic; it should deliver appropriate information, seek feedback, and create mutual understanding for change while emphasizing the urgency to change (Lewis & Sahay, 2018). Specifically, scholars have emphasized the importance of participative communication approaches throughout a change process (Lewis, Schmisseur, Stephens, & Weir, 2006; Lewis, Richardson, & Hamel, 2003). Instead of one-way top-down dissemination of information, organizations should adopt participatory practices and enable employees to voice their opinions during change-related decision-making processes (Lewis & Russ, 2012). Such practices facilitate employee acceptance of the change, decrease their perceptions of uncertainty, and boost their satisfaction with their organizations (Lewis, 2006).

Among many models of participatory communication practice (Lewis, 2011), this study particularly pays attention to transparent internal communication, one of the widely-recognized internal communication models in public relations research, during the process of organizational change and how it affects employees’ reactions toward such change. Transparent internal communication, a concept that originated from organizational transparency, refers to “an organization’s communication to make available all legally releasable information to employees whether positive or negative in nature—in a manner that is accurate, timely, balanced and unequivocal, for the purpose of enhancing the reasoning ability of employees, and holding organizations accountable for their actions, policies, and practices” (Men, 2014, p. 260). Scholars suggest that transparent internal communication is a multifaceted concept that includes three dimensions: accountable, participative, and informational transparency (Men & Stacks, 2014; Rawlins, 2008).

Accountable transparency indicates that organizations should provide comprehensive and complete information, including both positive and negative news (e.g., threats and opportunities), to their employees. The provision of such information can help reduce the possibility of employees’ anxiety toward, uncertainty about, misinterpretation of, and rumors about the organizational change (Men & Yue, 2019). Participative transparency suggests that organizations should actively participate in information seeking, distribution, and creation with their employees. In doing so, organizations may identify employees’ needs of particular information and thus provide the most useful and relevant information (Men & Yue, 2019). In other words, participative transparency requires organizations to engage employees during the change communication process; employee feedback can help organizations identify the useful and relevant information that employees truly need (Lee & Li, 2019). This participative practice contradicts a top-down communication approach characterized by only “telling” but not “listening to” employees, which may overwhelm and further confuse employees regarding the change (Lewis & Russ, 2012). Finally, informational transparency emphasizes organizations’ efforts to provide truthful, substantial, and valuable information to their employees. Such quality of information can help avoid confusion and improve communication efficiency within organizations (Rawlins, 2008). It is important to note that practicing informational transparency differs from simply disclosing all information to employees (Yue et al., 2019). The former requires organizations to provide employees with substantial but relevant and important information that helps facilitate employees’ understanding of the change’s purpose, process, and content. However, mere information disclosure may bombard employees with excessive, irrelevant, or redundant information that can create further uncertainty and confusion (Rawlins, 2008). As such, instead of sharing all releasable information with employees, organizations should implement informational transparency, providing both positive and negative but relevant and needed information that can help employees make sense of what is going on in the organizations (Yue et al., 2019).

Altogether, transparent internal communication practices highlight the importance of both information quality and quantity (Rawlins, 2008). Only when an adequate amount of high-quality information is provided to employees can they effectively make sense of and cope with negative organizational events such as unplanned changes induced by crises (Kim, 2018). In public relations literature, transparent internal communication practices have been found to be associated with employee trust in the company (Rawlins, 2008), employee engagement (Linhart, 2011), employees’ active communication behaviors in crisis situations, and an organization’s internal reputation (Kim, 2018; Men, 2014). Along with the literature that demonstrates the important role of transparent communication within organizations, this study examines how such communication practices affect employees’ coping style and the uncertainty management process related to unplanned organizational change.

2.1.1. Transparent communication and coping style

Another important factor during an organizational change process is employees’ coping actions. Coping refers to “the thoughts and behaviors use to manage the internal and external demands of situations that are appraised as stressful” (Folkman & Moskowitz, 2004, p. 745). Although coping strategies have been operationalized in various ways, the dichotomous classification is among the most commonly used taxonomies (Bain, McGroarty, & Runcie, 2015). The theoretical model suggests that coping with stress can be problem-solving or emotion-regulating (Folkman & Lazarus, 1984). Latack (1986) labels these two strategies as control and escape oriented coping, respectively. Given that various research in organizational management subscribes to the bi-dimensional approach (Srivastava & Tang, 2015), this study adopts such operationalization to understand employees’ coping during organizational change.

Control coping involves “proactive, take-charge intone,” indicating that individuals seek to fix the situation that creates stress. When adopting such a strategy, a person analyzes the situation, generates solutions, and implements a plan to deal with the situation and its consequent stress (Leiter, 1991). By contrast, escape coping suggests that, rather than proactively tackling the problems, individuals attempt to adopt escapist and avoidance modes, so that they can minimize emotional impacts created by the problem (Folkman & Lazarus, 1984). When coping with the escape approach, a person seeks to control emotional outcomes of the problem by using tactics such as avoiding the situation, remaining silent, or distancing from the threat (Hershcovis, Cameron, Gervais, & Bozeman, 2018). Therefore, escape coping strategy is also known as an avoidance strategy.

An individual’s coping process and choice of coping strategies differ across situational contexts and depend upon whether the individuals believe the situation can be changed by their own efforts (Folkman & Lazarus, 1984; Folkman et al., 1991; Zellars, Liu, Bratton, Brymer, & Perrewé, 2004). Specifically, scholars have identified one’s sense of certainty and situational controllability as two primary determinants of coping strategy adoption (Jin, 2010). The resources that help establish the feeling of certainty and controllability may motivate individuals to choose proactive coping (i.e., control coping) over passive coping (i.e., escape coping) (Jin, 2010). Specifically, in the work domain, the availability of organizational resources tends to shape employees’ perceptions of certainty and controllability regarding a stressful situation at work, thus helping employees determine the use or choice of certain coping strategies (Holton, Barry, & Chaney, 2016). Therefore, coping strategy choices can be viewed largely as an outcome of coping resources (Kraaij, Garnefski, & Maes, 2002). For example, in the contexts of organizational change, scholars suggested that employees tend to choose to cope actively (control strategy) when they experienced positive emotions related to the changes at work (Fugate, Kinicki, & Prussia, 2008). Positive emotions, like hope or joy, toward organizational changes could create a favorable impression of the changes and, as a result, employees may view such changes “as an opportunity to learn and grow” (Fugate et al., 2008). Social support from supervisors and colleagues were also found to encourage control strategy adoption (Lawrence & Callan, 2011). The sense of belonging and inclusion enables employees to see control coping as a non-threatening option to manage change-related stress.

From this perspective, transparent internal communication that provides accountable, truthful, and substantial information related to organizational change can be considered as an important workplace coping resource. Previous studies have identified the provision of information as a significant antecedent of the use of effective coping efforts such as control coping (Callan & Dickson, 1993; Lawrence & Callan, 2011). The availability of information and the communication during organizational change equip employees with better resources and supports (Callan & Dickson, 1993). Thus, they attempt to become more active and analytical in coping with the changes. On the other hand, lacking information may signal the shortage of resources and lead individuals to perceive uncertainty and uncontrollability regarding the stressful situation and thus not invest efforts in adopting control coping (Ito & Brotheridge, 2003). Rather, they would perform escape coping (Ito & Brotheridge, 2003). These studies mainly focus on the role of the availability of communication rather than the quality of communication in shaping employees’ coping strategy adoption while facing organizational change. However, this study expects that the high-quality information and the sense of shared control generated through transparent communication can help employees feel more prepared and able to actively cope with change. Therefore, we propose the following hypotheses to examine employees’ preferred coping strategy in response to organizational change:

H1a-b

Internal transparent communication practices during organizational change will be positively (negatively) related to control coping strategy (escape strategy) adoption.

2.1.2. Transparent communication and uncertainty management

Uncertainty, which refers to “an individual’s inability to predict something accurately” (Milliken, 1987, p. 136), is a frequently experienced condition during organizational change (Bordia, Hobman, Jones, Gallois, & Callan, 2004). When facing organizational change, employees may experience uncertainty regarding the reasons for the change, the process of execution, and the potential outcomes on organizations and employees themselves (Bordia et al., 2004). Such perceived uncertainty may create stress and as a result, negatively affect employees’ attitudes, perceptions, and behaviors toward the organizations (Cullen, Edwards, Casper, & Gue, 2014). Therefore, employees’ understanding and attitudes toward such change play important roles during organizational change (Choi, 2011), because it can directly shape employees’ uncertainty perceptions, and indirectly affect their organizational performance, which may in turn determine the success or failure of such changes (Carter, Armenakis, Feild, & Mossholder, 2013). As such, uncertainty management process during organizational change warrants deeper investigation.

Uncertainty management theory provides possible insights into the best techniques for managing uncertainty during organizational change (Herzig & Jimmieson, 2006). This perspective highlights the importance of communication in managing uncertainty, considering communication as a mean for motivating individuals to manage the sense of ambiguity and insecurity (Brashers, 2001). When facing organizational change, employees intend to make sense of such changes by obtaining hints and information from the work environment (Cullen et al., 2014). The understanding of the change may help reduce confusion and doubt regarding changes, while the ambiguity of the situations may increase uncertainty about such changes (Rafferty & Griffin, 2006). Therefore, scholars suggested that communication and information provisions regarding change can smoothen the difficulties and uncertainty associated with the change (Bordia, Jones, Gallois, Callan, & DiFonzo, 2006; Allen, Jimmieson, Bordia, & Irmer, 2007; Bordia et al., 2004). Effective, transparent communication distributes appropriate information about the process and the impacts of organizational change, allows employees to participate in decision making during changes, and thereby increases their understanding of the events and reducing both uncertainty and doubt toward the organizations (Rogiest, Segers, & van Witteloostuijn, 2015; Welch & Jackson, 2007). Therefore, the following hypothesis was proposed:

H2

Internal transparent communication practices during organizational change will be negatively related to employees’ perceived uncertainty of organizational change.

2.1.3. Coping style and uncertainty management

Organizational change modifies the way work is done in the organizations and leads to employees developing fear about whether they are capable of coping with the changes (Vakola & Nikolaou, 2005). The uncertainty management theory helps explain that information and solutions provided through coping can be another means to manage uncertainty (Thau, Bennett, Mitchell, & Marrs, 2009). The majority of studies in organizational change research demonstrated that employees who proactively cope with change are more likely equipped to understand the rationale behind the changes and contribute to the change process (Cunningham, 2006). Although control-oriented coping does not shield employees from encountering stressors during organizational change, such coping approach provides employees with resources to reaffirm their sense of control when facing stressors (Leiter, 1991; Robinson & Griffiths, 2005). By contrast, escape coping has been viewed as an inadequate approach to coping. Such a strategy may hinder individuals from investing in problem-solving, resulting in adverse work-related outcomes, such as emotional exhaustion and job dissatisfaction (Ito & Brotheridge, 2003). Prior research in psychology suggested that escape coping may merely provide temporary relief from addressing the stressful situation but not completely resolve the problem (Bigatti, Steiner, & Miller, 2012). Thus, control coping is often associated with positive employee outcomes, while escape coping appears to be associated with negative work-related results (Srivastava & Tang, 2015). Accordingly, we expected that control coping with organizational change may be effective in managing change-related uncertainty, whereas escape coping with such change may be ineffective. Thus, the following hypotheses were proposed:

H3a-b

Control coping strategy (Escape coping strategy) adoption will be negatively (positively) related to employees’ perceived uncertainty of organizational change.

2.2. Managing organizational change: Relational quality outcomes

The literature on organizational change clearly stated how the process of change is informed, implemented, and managed directly affects the perceptions and the behaviors of employees (Gomes, 2009). As a result, the impacts of organizational change on the relationship between employees and their organizations have been the central focus in organizational change research (Carter et al., 2013). This study attempts to study the relationship between organizational change and an important public relations construct: employee-organization relationships (EORs).

In the past decades, public relations practice and research have centered on developing and maintaining mutually beneficial relationships between an organization and its strategic publics (Ferguson, 2018). Emphasizing the strategic publics with whom an organization has the closest connection—employees (Lee & Tao, 2020)—public relations scholars have extensively examined employee-organization relationships (EORs), along with its antecedents and outcomes (e.g., Men & Jiang, 2016; Thelen, 2019). EORs refer to “the degree to which an organization and its employees trust one another, agree on who has the rightful power to influence, experience satisfaction with each other, and commit oneself to the other” (Men & Stacks, 2014, p. 307). Its definition reveals four markers of desirable EORs: trust, control mutuality, commitment, and satisfaction (Kang & Sung, 2019). Trust represents relational parties’ confidence in each other and willingness to open up oneself to the other (Men, Yue, & Liu, 2020). Satisfaction defines a favorable state wherein relational parties have fulfilled or exceeded expectations toward each other. Commitment is “the extent to which one party believes and feels that the relationship is worth spending energy to maintain and promote” (Hon & Grunig, 1999, p. 20). Control mutuality concerns power (in)balance: “the degree to which relational parties agree on who has rightful power to influence one another” (Hon & Grunig, 1999, p. 19). Ample evidence has shown that quality EORs motivate employee advocacy for the organization (Thelen, 2019), enhance organizational performance, and facilitate organizational goal achievement (Men & Stacks, 2014). When considering turbulent times such as organizational change and crisis, quality EORs function as a bank of goodwill that can be drained to buffer the severe impact of these negative events on the organization and its employees (Bal, de Lange, Ybema, Jansen, & van der Velde, 2011).

Given the essential role of quality EORs in organizational success, public relations and organizational scholars have been dedicated to unveiling EOR drivers, including but not limited to transformational leadership style, authentic organizational behaviors, and strategic internal communication (Kim & Rhee, 2011; Lee & Kim, 2017; Men & Stacks, 2014). In this study, we view these three aforesaid factors in the organizational change process—transparent communication, coping style, and change-related uncertainty—as potential determinants that affect employees’ perceived quality of relationship with their organization, EORs.

2.2.1. Transparent communication and EORs

Transparent communication’s effectiveness in cultivating quality EORs has been robustly evidenced in public relations and management studies. For example, both Rawlins (2008) and Schnackenberg and Tomlinson (2016) concluded that transparency, throughout every aspect of organizational communication, is essential to the trust that employees place in organizations. In line with their conclusion, Kelleher, Men, and Thelen (2019) empirically substantiated the significant role of transparent communication in boosting EORs during routine organizational operation. Yue et al. (2019) further showed that this role also applied to the context of organizational change.

As mentioned earlier, strategic internal communication manifested by transparent communication is essential to organizational change management (Yue et al., 2019). In times of great uncertainty, accurate, timely, truthful, and balanced information from the management is expected by organizational employees (Kim, 2018). Fulfilling this expectation not only satisfies employees (relational satisfaction) but also increases employees’ confidence in the organization in managing changes (relational trust) (Yue et al., 2019). Additionally, fostering a participatory communication climate by inviting employees to identify useful information and allowing them to voice their concerns during change-related decision-making increases their feelings of shared control (control mutuality) (Tao, Song, Ferguson, & Kochhar, 2018). All these experiences, promoted by transparent communication, constitute quality EORs during organizational change. Therefore, we propose the following hypothesis:

H4

Internal transparent communication practices during organizational change will be positively related to the quality of EORs.

2.2.2. Coping style and EORs

Although little empirical effort has been made to examine the link between coping style with organizational change and employee perceived relational quality, prior research provides an important insight to develop this hypothesis. In organizational research, control-oriented coping has been found to be associated with positive employee outcomes. However, escape coping has been shown to be related to negative employee outcomes, such as job attitudes, psychological well-being, and organizational citizenship behavior (e.g., Fugate et al., 2008). It was therefore expected that using control coping (escape coping) during organizational change positively (negatively) influences employees’ trust in, satisfaction with, commitment to, and ability to influence the decision-making process in their organization, namely, EORs. The following hypothesis is thus proposed:

H5a-b

Control coping strategy (Escape coping strategy) adoption will be positively (negatively) related to the quality of EORs.

2.2.3. Uncertainty and EORs

In the organizational context, employee uncertainty has been found to place several negative outcomes for satisfaction and well-being (Bordia et al., 2004). In particular, during organizational change, the perceived uncertainty created by the lack of information or control may cause job insecurity, which in turn can generate negative effects on job satisfaction, trust, and commitment in the organization (Cullen et al., 2014). In a similar vein, the present study expects that change-related uncertainty negatively affects the overall quality of the relationship between an organization and its employees. The following hypothesis is derived:

H6

Perceived uncertainty of organizational change will be negatively related to the quality of EORs.

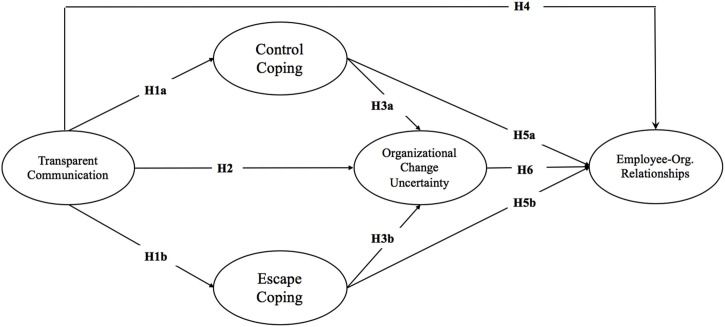

The conceptual model is presented in Fig. 1 .

Fig. 1.

Conceptual model.

3. Methods

3.1. Sampling and participants

To test the proposed hypotheses, a quantitative online survey was conducted during the second and third week of April 2020. At the time of the survey, COVID-19 has drastically interrupted business operations and people’s daily lives in the U.S. President Trump had declared a national emergency and residents in most states had been under orders to stay home. The population of this study consisted of full-time U.S. employees with different levels of job positions at small, medium, and large organizations. To recruit qualified participants, this study used the employee panel pool from Dynata, a premier global provider of survey services that had access to 1.5 millions of panel participants in the U.S. through its patented sampling platform. Stratified random sampling was employed to achieve a representative sample of U.S. employees according to the most recent U.S. census data in terms of gender, age, and ethnicity categories.

A final sample of 490 participants was obtained. Their average age was 45.13 years (SD = 13.8; Median = 43). About 49 % of them were male and 51 % were female. A majority (62 %) were Caucasians, followed by Hispanic/Latino (16.9 %), African Americans (13.1 %), and Asian/Asian Americans (5.1 %). A majority of the participants (67.1 %) held a bachelor’s degree or higher. More than half of them (58.4 %) had an annual income of $60,000 or above. Note that there was substantial overlap between the actual U.S. population and our final sample with respect to age, gender, and ethnicity.1

The participants came from companies across more than 20 industries such as agriculture, construction, manufacturing, wholesale and retail trade, information and telecommunication, finance and insurance, health care and social assistance, education services, among others. The size of these companies ranged from 0 to 49 employees (20 %) to 2000 employees or more (26.5 %). Approximately, 47.3 % of these participants identified themselves as non-management employees; 34.3 % as low-level managers; 8% as middle-level managers; and, 10.4 % as upper-level managers. Regarding company tenure, 30.8 % of them had worked for their companies for more than 11 years; followed by 20.6 % for four to six years; and, 19.2 % for one to three years.

3.2. Measures

All items used in the current study were adopted from previous literature. A 7-point Likert scale was used for all items, ranging from (1) strongly disagree to (7) strongly agree. All measure items were situated in the context of “during the COVID-19 outbreak.” Table 1 presents the measurement items.

Table 1.

Measurement items.

| Measurement Items | Standardized Factor Loadings | |

|---|---|---|

| Transparent Communication | ||

| Accountable transparency | .85* | |

| Particitive transparency | .88* | |

| Substanital transparency | .87* | |

| Accountable transparency | During the COVID-19 outbreak,

|

.82* |

|

.83* | |

|

.87* | |

|

.84* | |

|

.82* | |

|

Participative transparency |

During the COVID-19 outbreak,

|

.87* |

|

.86* | |

|

.84* | |

|

.82* | |

|

.85* | |

| Substantial transparency | During the COVID-19 outbreak,

|

.85* |

|

.81* | |

|

.82* | |

|

.84* | |

|

.82* | |

| Control coping | When facing organizational change/work change in response to COVID-19,

|

.81* |

|

.83* | |

|

.81* | |

|

.89* | |

|

.80* | |

| Escape coping | When facing organizational change/work change in response to COVID-19,

|

.84* |

|

.89* | |

|

.82* | |

|

.83* | |

| Organizational change uncertainty | My work environment is changing in an unpredictable manner due to COVID-19. | .89* |

| I am uncertain about how to handle my work during the COVID-19 outbreak. | .82* | |

| I am unsure about how the COVID-19 outbreak affects my work. | .81* | |

| I am unsure how severely the COVID-19 outbreak will change my work. | .81* | |

| EORs | ||

| Trust | .88* | |

| Control Mutuality | .87* | |

| Commitment | .85* | |

| Satisfaction | .86* | |

| Trust | During the COVID-19 outbreak,

|

.85* |

|

.83* | |

|

.81* | |

|

.85* | |

| Control Mutuality | During the COVID-19 outbreak,

|

.82* |

|

.86* | |

|

.89* | |

| Commitment | During the COVID-19 outbreak,

|

.89* |

|

.89* | |

|

.89* | |

| Satisfaction | During the COVID-19 outbreak,

|

.86* |

|

.85* | |

|

.90* |

p < .001.

3.2.1. Transparent communication

Transparent communication was measured with 15 items (α = .96) adopted from Jiang and Men (2017). It consists of three types of communication practices during COVID-19: participative (5 items, α = .93), such as “my company takes the time with its employees to understand who they are and what they need”; substantial (5 items, α = .96), such as “my company provides information that is complete to employees”; and accountable (5 items, α = .92), such as “my company is open to criticism by employees.” Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) results showed that the two-factor model has a good model fit for all three types of transparent communication, χ2 (74) = 270.25; RMSEA = .05 [.05, .06]; CFI = .97; SRMR= .04.

3.2.2. Coping strategy

Items that measured coping strategy were situated in the context of “when facing organizational change/work change in response to COVID-19.″ Control coping strategy was measured with five items adopted from Latack (1986) and Leiter (1991) (α = .83), such as “I request help from people who have the power to do something for me,” and “I put extra attention to planning and scheduling.” Escape coping strategy was measured with four items adopted from Latack (1986) and Leiter (1991) (α = .74), such as “I accept this situation because there is nothing I can do to change it,” and “I anticipate the negative consequences so that I’m prepared for the worst.”

3.2.3. Organizational change uncertainty

Perceived uncertainty of organizational change was measured with four items adopted from Rafferty and Griffin (2006) (α = .82), such as “I am unsure about how the COVID-19 outbreak affects my work,” and “my work environment is changing in an unpredictable manner due to COVID-19.″

3.2.4. Employee-organization relationships (EORs)

EORs was measured with 13 items (M = 5.16, SD = 1.31, α = .97) adopted from Hon and Grunig (1999). It includes four dimensions: trust (4 items, α = .90), control mutuality (3 items α = .91), commitment (3 items, α = .93), and satisfaction (3 items, α = .91). Examples from each subdimensions are “My company treats employee like me fairly and justly” “My company really listens to what an employee like me have to say,” “I feel that my company is trying to maintain a long-term commitment to employees like me,” and “I am happy with my company,” respectively. CFA results showed that the two-factor model has a good model fit for all four types of EORs, χ2 (59) = 174.37; RMSEA = .06 [.05, .06]; CFI = .98; SRMR= .02.

3.3. Data analysis

The reliability of the measurement items for all constructs used in this study was tested using Cronbach’s alpha. To test the hypotheses suggested in this study, we used a two-stage procedure of structural equation modeling (SEM) approach (Anderson & Gerbing, 1988) using Mplus program. The following criteria was adopted to evaluate the model fit: root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) < .08; comparative fit index (CFI) > .90; Tucker-Lewis index (TLI) > .90 (Hair, Black, Babin, Anderson, & Tatham, 1998), and standardized root mean square residual (SRMR) < .90 (Hu & Bentler, 1998).

4. Results

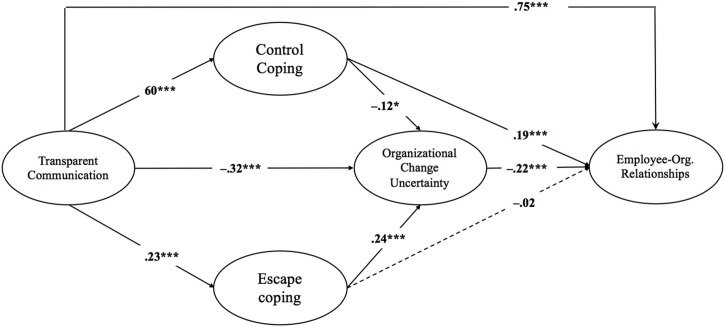

Table 2 summarizes means, standard deviations, reliabilities, and correlations among the variables used in the current study. The results of CFA demonstrated reasonable model fits for the measurement model, χ2 (425) = 1,108.123; RMSEA = .05 [.05, .06]; CFI = .95; TLI = .94; SRMR = .05. It also revealed that all the factor loading values were significant and above the threshold value of 0.5, providing support for the convergent validity of the measurement model (Stevens, 1992). Therefore, the researchers proceeded to test the structural models. The hypothesized models fit the data well based on the cutoff values, χ2 (426) = 1115.61; RMSEA = .05 [.05, .06]; CFI = .95; TLI = .94; SRMR = .05. Fig. 2 depicts the final model.

Table 2.

Means, Standard Deviations, reliabilities and Zero-Order Correlations Among Model Constructs.

| M | SD | α | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

5.02 | 1.27 | .96 | ||||

|

5.14 | 1.11 | .83 | .51** | |||

|

5.04 | 1.01 | .74 | .20** | .19** | ||

|

4.21 | 1.49 | .82 | –.10* | .06 | .17** | |

|

5.16 | 1.31 | .97 | .82** | .47** | .17** | –.13** |

Note: *p < .01, **p < .001.

Fig. 2.

Results of the hypotheses testing.

H1a-b tested the relationship between transparent internal communication and coping strategy. A significant and positive relationship was found between transparent communication and control coping strategy (.60, p < .001). Contrary to our expectation, transparent communication was positively associated with escape coping strategy (.23, p < .001). Therefore, H1a was supported, but H1b was not supported.

H2 predicted a negative relationship between transparent organizational communication and perceived uncertainty of organizational change. A significant and negative relationship was found between transparent communication and organizational change uncertainty (–.32, p < .001), offering support for H2.

H3a-b investigated the relationship between coping strategy and perceived uncertainty of organizational change. The results found a significant and negative relationship between control coping strategy and perceived uncertainty of organizational change (–.12, p < .01), whereas a significant and positive relationship was found between escape coping strategy and organizational change uncertainty (.24, p < .001), offering support for H3a-b.

H4 tested the relationship between transparent internal communication and EORs. A significant and positive relationship was found between transparent communication and EORs (.75, p < .001), offering support for H4.

H5a-b investigated the relationship between coping strategy and EORs. The results found a significant and positive relationship between control coping strategy and EORs (.19, p < .001), thus supporting H5a. However, escape coping strategy did not show a significant relationship with EORs (–.02, p > .05), failing to support H5b.

H6 predicted a negative relationship between organizational change uncertainty and EORs. A significant and negative relationship was found between organizational change uncertainty and EORs (–.22, p < .001), offering support for H6.

Although not hypothesized, additional tests of indirect effects of coping strategy and organizational change uncertainty were conducted. Results showed that the mediating effects of control coping between transparent communication and organizational change uncertainty were significant (–.16, p < .001). The paths from transparent communication to EORs were also found to be significantly mediated by both control coping (.09, p < .01) and organizational change uncertainty (.07, p < .01). Finally, significant indirect effects were found in paths from transparent communication to EORs via control coping and uncertainty (.05, p < .01).

5. Discussion

On the basis of organizational change, communication, and coping literature, this study developed and tested a model in which transparent internal communication affects employees’ management of organizational change, specifically in the case of COVID-19. Results of an online survey showed that, when facing organizational change related to a public health emergency (i.e., COVID-19 in this study), transparent communication by organizations can impact how employees cope with those changes and reduce their change-related uncertainty. Such internal communication practices along with control coping strategy adoption and uncertainty reduction can effectively foster healthy relationships between employees and their organizations. This study provides important theoretical and practical implications for organizational leadership and employee relationship.

5.1. Theoretical implications

The current study contributes to the existing public relations literature on organizational change in understanding employees’ change management mechanisms during a global pandemic. The COVID-19 pandemic outbreak is viewed as a significant crisis event that prompts profound unplanned organizational change (Harter, 2020). In comparison with well-planned and anticipated change initiatives, such crisis-induced change entails high levels of risk and uncertainty that may lead employees to feel confused, anxious, or incompetent, compared to those well-planned and anticipated change initiatives (Shaw, 2018). Despite the well-documented role of uncertainty in both organizational change and crisis communication literature, research has not adequately explicated the mechanism through which strategic public relations efforts can reduce such uncertainty among employees and facilitate their coping with the crisis and unplanned change induced by the crisis (Liu, Bartz, & Duke, 2016). Our study thus addressed this research gap by revealing such a mechanism and providing insights into how strategic internal communication efforts matter in facilitating uncertainty reduction and coping processes. By doing so, we extended the application of a strategic management approach to unplanned organizational change situations.

Furthermore, this study theorizes and empirically supports a theoretical model that links transparent internal communication, employees’ coping strategy, and organizational change uncertainty with EORs. Its findings represent a convincing case for the necessity of integrating multi-disciplinary insights to advance the much-needed theoretical understanding of employee experiences during organizational change and related downstream outcomes. Based on three theoretical frameworks—relationship management, the transactional theory of stress and coping, and uncertainty management—the integrative model we propose maps out employees’ psychological experiences in face of crisis and change.

Change communication has been long acknowledged as an indispensable strategy when organizations face change as it helps determine how such change is interpreted by employees (Allen et al., 2007). However, the extant literature has been less clear about the specific type of communication that can be effective and how such communication should be strategically managed (Lewis & Russ, 2012). The findings of this study provided insight into the strategic management of change communication, adding another piece of empirical evidence supporting the importance of transparent communication during organizational change (e.g., Lewis, 2011). Particularly when facing unplanned change, employees have an intrinsic need to know about what to expect and how to react. This study suggests that by allowing employees to participate in the decision-making process and to receive sufficient high-quality and accountable information during change, transparent communication practices equip employees with the means to deal with such change.

Specifically, according to the findings, transparent communication practices was shown to associate with employees’ coping and uncertainty management process during organizational change. In line with coping theory (Folkman & Lazarus, 1984) and uncertainty management theory (Brashers, 2001), information serves as the fundamental guidance for employees when selecting coping strategies or managing uncertainties related to organizational change. Different from mere information disclosure, organizational provision of information with transparency, consistency, and accountability may provide employees with better resources and supports to proactively cope with the changing work environment (Magala, Frahm, & Brown, 2007). Additionally, such information may also allow employees to better understand the rationale behind the change, the implementation of the change, and the expected outcome of the change, which can help reduce uncertainty perceptions (Allen et al., 2007).

One unexpected finding is that, although transparent communication practices predict greater intention to adopt control coping, such communication system also shows some positive impacts on encouraging escape coping. The results suggested that we should not preclude a positive relationship between transparent communication and escape coping. As transparent communication may be imbued with messages that can convince employees not to be concerned about the changes or that inform employees about the worst consequences of the changes, it may spur action in escape coping. However, in line with the previous studies (e.g., Srivastava & Tang, 2015), our findings demonstrated control coping as a more effective strategy than escape coping in uncertainty management and relationship maintenance.

Moreover, the mediation tests showed that coping strategy serves as a mediator between transparent communication and uncertainty perception and between transparent communication and relational management. The findings suggested that control coping reinforces the effects of transparent communication on uncertainty management and relationship quality. Such an indirect role of control coping may pinpoint the importance of the incorporation of transparent communication and coping education. Namely, the mediating role of control coping implies that it is important to not only communicate with employees with transparency regarding organizational change but also educate employees about the skills and resources that allow them to understand the benefits of control coping and encourage them to adopt such strategy when facing organizational change.

Another important contribution of this study is the inclusion of EORs in the contexts of organizational change. More specifically, this study contributes to a growing body of literature on relationship management in public relations by evaluating EORs as the outcomes of internal communication, coping strategy adoption, and uncertainty management during organizational change. Although the consequences of organizational changes on employees have been well demonstrated in the literature, the majority of studies focused on one specific aspect of employee outcomes, such as job satisfaction (e.g., Amiot, Terry, Jimmieson, & Callan, 2006), commitment (e.g., Freese, Schalk, & Croon, 2011), and trust (e.g., Agote, Aramburu, & Lines, 2016). This study moves beyond one single dimension of employee outcomes and includes EORs as the ultimate long-term relational outcomes.

EORs have been applied to describe the multifaceted relational quality that includes a wide range of aspects between the employee and the organization (Shore et al., 2004, p. 292). Considering EORs as the employee-related outcomes can provide a comprehensive understanding of how employees manage organizational change and the impacts of such processes. This study suggested that transparent internal communication, coping strategy, and uncertainty management can all serve as a factor in facilitating or inhibiting EORs during organizational change. As a result, this study contributes to the research vein that dedicates to unveil the determinants of quality EORs. Specifically, EORs, as a type of organization-public relationships, has been noted as a key indicator of public relations effectiveness as well as a key outcome of public relations efforts (e.g., Men, 2014). The proposed model in this study, which positions EORs as the final outcome, advances public relations literature by verifying the underlying mechanism as to how EORs can be formed and shaped through public relations efforts, particularly during unplanned organizational change events. The findings demonstrated that transparent internal communication and uncertainty reduction may facilitate the relational quality between organizations and their employees in the face of crisis and change.

Overall, these findings provide keen insights in how individuals experience and manage organizational change and further advances the associative relationships among internal communication, coping, uncertainty management, and relationship quality. This study contributes to both expanding organizational change and public relations literature by suggesting that when facing changes in the workplace, the combination of transparent communication and control coping education can reduce uncertainty related to the organizational changes and improve EORs.

5.2. Practical implications

This study also offers practical implications for organizational leaders and internal communication practitioners in addressing employee adaption to organizational changes. First, in line with previous research showing that communication plays an important role in determining employees’ reactions during organizational change, our findings indicated that transparent internal communication practices encourage control coping, reduce uncertainty, and improve EORs. Particularly during a global pandemic characterized by extreme uncertainty, daily communication practices may be enormously helpful in providing employees appropriate means to manage related changes. Hence, organizations should practice internal communication, following the principles of transparent communication in public relations research. Namely, organizations should provide truthful, accountable, and substantial information about organizational change and encourage employees to participate in decision-making or change implementation processes. These communicative efforts would help employees proactively cope with changes, reduce change-related uncertainty, and foster quality EORs.

Moreover, organizations should also include educational information regarding control coping approaches. Transparent communication about organizational change provides employees with necessary information regarding future business operations, policies, and procedures related to the changes. Our findings suggested that such communication may encourage employees to adopt both escape and control coping. As escape coping will increase the uncertainty felt by employees related to organizational change, it is vital to encourage employees to actively adopt control coping. That is to say, transparent communication regarding organizational change as well as control coping training are equally important. These communicative efforts may help employees establish essential resources to effectively cope with organizational change and manage related uncertainty. Such efforts can help organizations maintain a high-quality relationship with employees in the face of the unprecedented challenges and abrupt changes.

5.3. Limitations and future studies

Several limitations should be considered when interpreting the findings. First, although this study tested the conceptual model in the context of COVID-19 outbreak, organizations where the participants currently work may have different policies and change procedures (e.g., layoff) in response to the crisis. Such variances should be addressed in future studies by collecting the data from a single industry or a company. Second, this study is based on a cross-sectional survey data collected at the early stage of COVID-19 outbreak (April 2020). As the crisis rapidly and continuously changed the organizational responses, individual employees’ cognitive and behavioral responses to changes may have changed accordingly. Future studies thus could utilize other methods such as longitudinal design to understand the effectiveness of transparent communication across the phases of organizational change. In addition, while organizations’ situational change-specific communication efforts have been found to be effective in nurturing EORs, employees may evaluate organizations’ change communication differently based on their personal experiences, situations, personalities, and job characteristics. Thus, future research should consider cross-situational variables as critical antecedents of employees’ perceived uncertainty, coping strategies during a change, and EORs. Finally, although this study operationalized coping strategies based on a well-established dichotomous taxonomy, later studies have expanded this classic typology by proposing more specific types of coping strategies under these two categories (e.g. problem-focused: active coping and planning; emotion-focused: venting of emotions and denial) (Carver, Scheier, & Weintraub, 1989). Future studies could contribute to the organizational change literature by adopting and examining coping strategies in a more specific way.

6. Conclusion

The disruptions related to COVID-19, a global pandemic that poses an existential threat and exerts enormous impacts on individuals as a workforce, have forced organizations to make changes in their operations to better adapt the new, changed world. How to help employees manage the sudden changes created by these unprecedented challenges is an important question for organization leaders. The findings of this study contribute to further understanding of internal communication and its effects on employees’ coping, uncertainty, and relationship management during organizational change. Specifically, this study found that transparent internal communication could encourage employees to proactively cope with organizational change, assist them in reducing change-related uncertainty, and ultimately cultivate quality EORs while facing changes.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors report no declarations of interest.

Footnotes

According to the most recent U.S. census data (The United States Census Bureau, 2018), the U.S. population consisted of 49.2% male and 50.8% female. The median age was 38.2. A majority (72.2%) were Caucasians, followed by African Americans (12.7%) and Asian/Asian Americans (5.6%). About 18.3% were Hispanic/Latino while the rest 81.7% were not.

References

- Agote L., Aramburu N., Lines R. Authentic leadership perception, trust in the leader, and followers’ emotions in organizational change processes. The Journal of Applied Behavioral Science. 2016;52(1):35–63. [Google Scholar]

- Allen J., Jimmieson N.L., Bordia P., Irmer B.E. Uncertainty during organizational change: Managing perceptions through communication. Journal of Change Management. 2007;7(2):187–210. [Google Scholar]

- Amiot C.E., Terry D.J., Jimmieson N.L., Callan V.J. A longitudinal investigation of coping processes during a merger: Implications for job satisfaction and organizational identification. Journal of Management. 2006;32(4):552–574. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson J.C., Gerbing D.W. Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychological Bulletin. 1988;103(3):411. [Google Scholar]

- APQC (American Productivity & Quality Center) 2020. Strategic guidance relevant to COVID-19.https://www.apqc.org/COVID19 Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Bain S.A., McGroarty A., Runcie M. Coping strategies, self-esteem and levels of interrogative suggestibility. Personality and Individual Differences. 2015;75:85–89. [Google Scholar]

- Bal P.M., de Lange A.H., Ybema J.F., Jansen P.G., van der Velde M.E. Age and trust as moderators in the relation between procedural justice and turnover: A large‐scale longitudinal study. Applied Psychology. 2011;60(1):66–86. [Google Scholar]

- Barrett D.J. Change communication: Using strategic employee communication to facilitate major change. Corporate Communications an International Journal. 2002;7(4):219–223. [Google Scholar]

- Bigatti S.M., Steiner J.L., Miller K.D. Cognitive appraisals, coping and depressive symptoms in breast cancer patients. Stress and Health : Journal of the International Society for the Investigation of Stress. 2012;28(5):355–361. doi: 10.1002/smi.2444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bordia P., Hobman E., Jones E., Gallois C., Callan V.J. Uncertainty during organizational change: Types, consequences, and management strategies. Journal of Business and Psychology. 2004;18(4):507–532. [Google Scholar]

- Bordia P., Jones E., Gallois C., Callan V.J., DiFonzo N. Management are aliens! Rumors and stress during organizational change. Group & Organization Management. 2006;31(5):601–621. [Google Scholar]

- Brashers D.E. Communication and uncertainty management. The Journal of Communication. 2001;51(3):477–497. [Google Scholar]

- Callan V.J., Dickson C. Managerial coping strategies during organizational change. Asia Pacific Journal of Human Resources. 1993;30(4):47–59. [Google Scholar]

- Carter M.Z., Armenakis A.A., Feild H.S., Mossholder K.W. Transformational leadership, relationship quality, and employee performance during continuous incremental organizational change. Journal of Organizational Behavior. 2013;34(7):942–958. [Google Scholar]

- Carver C.S., Scheier M.F., Weintraub J.K. Assessing coping strategies: A theoretically based approach. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1989;56(2):267. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.56.2.267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease and Control Prevention . 2020. Business and workplace: Plan, prepare, and respond.https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/community/organizations/businesses-employers.html Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Choi M. Employees’ attitudes toward organizational change: A literature review. Human Resource Management. 2011;50(4):479–500. [Google Scholar]

- Connley C., Hess A., Liu J. CNBC.com; 2020. 13 ways the coronavirus pandemic could forever change the way we work.https://www.cnbc.com/2020/04/29/how-the-coronavirus-pandemic-will-impact-the-future-of-work.html Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Cullen K.L., Edwards B.D., Casper W.C., Gue K.R. Employees’ adaptability and perceptions of change-related uncertainty: Implications for perceived organizational support, job satisfaction, and performance. Journal of Business and Psychology. 2014;29(2):269–280. [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham G.B. The relationships among commitment to change, coping with change, and turnover intentions. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology. 2006;15(1):29–45. [Google Scholar]

- Elving W.J. The role of communication in organisational change. Corporate Communications an International Journal. 2005;10(2):129–138. [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson M.A. Building theory in public relations: Interorganizational relationships as a public relations paradigm. Journal of Public Relations Research. 2018;30(4):164–178. [Google Scholar]

- Folkman S., Lazarus R.S. Springer Publishing Company; New York: 1984. Stress, appraisal, and coping; pp. 150–153. [Google Scholar]

- Folkman S., Moskowitz J.T. Coping: Pitfalls and promise. Annual Review of Psychology. 2004;55:745–774. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.55.090902.141456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folkman S., Chesney M., McKusick L., Ironson G., Johnson D.S., Coates T.J. The social context of coping. Springer; Boston, MA: 1991. Translating coping theory into an intervention; pp. 239–260. [Google Scholar]

- Freese C., Schalk R., Croon M. The impact of organizational changes on psychological contracts. A longitudinal study. Personnel Review. 2011;40:404–422. [Google Scholar]

- Fugate M., Kinicki A.J., Prussia G.E. Employee coping with organizational change: An examination of alternative theoretical perspectives and models. Personnel Psychology. 2008;61(1):1–36. [Google Scholar]

- Gomes D.R. Organizational change and job satisfaction: The mediating role of organizational commitment. Exedra: Revista Científica. 2009;(1):177–195. [Google Scholar]

- Hair J.F., Black W.C., Babin B.J., Anderson R.E., Tatham R.L. Vol. 5. Prentice hall; Upper Saddle River, NJ: 1998. pp. 207–219. (Multivariate data analysis). No. 3. [Google Scholar]

- Harter J. Gallup.com; 2020. How coronavirus will change the “next normal” workplace.https://www.gallup.com/workplace/309620/coronavirus-change-next-normal-workplace.aspx Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Herold D.M., Fedor D.B., Caldwell S., Liu Y. The effects of transformational and change leadership on employees’ commitment to a change: A multilevel study. The Journal of Applied Psychology. 2008;93(2):346. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.93.2.346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hershcovis M.S., Cameron A.F., Gervais L., Bozeman J. The effects of confrontation and avoidance coping in response to workplace incivility. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology. 2018;23(2):163. doi: 10.1037/ocp0000078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herzig S.E., Jimmieson N.L. Middle managers’ uncertainty management during organizational change. Leadership & Organization Development Journal. 2006;27(8):628–645. [Google Scholar]

- Holton M.K., Barry A.E., Chaney J.D. Employee stress management: An examination of adaptive and maladaptive coping strategies on employee health. Work. 2016;53(2):299–305. doi: 10.3233/WOR-152145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hon L.C., Grunig J.E. The Institute for Public Relations, Commission on PR Measurement and Evaluation; Gainesville, FL: 1999. Guidelines for measuring relationships in public relations. [Google Scholar]

- Hu L.T., Bentler P.M. Fit indices in covariance structure modeling: Sensitivity to underparameterized model misspecification. Psychological Methods. 1998;3(4):424. [Google Scholar]

- Ito J.K., Brotheridge C.M. Resources, coping strategies, and emotional exhaustion: A conservation of resources perspective. Journal of Vocational Behavior. 2003;63(3):490–509. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang H., Men R.L. Creating an engaged workforce: The impact of authentic leadership, transparent organizational communication, and work-life enrichment. Communication Research. 2017;44(2):225–243. [Google Scholar]

- Jin Y. Making sense sensibly in crisis communication: How publics’ crisis appraisals influence their negative emotions, coping strategy preferences, and crisis response acceptance. Communication Research. 2010;37(4):522–552. [Google Scholar]

- Johansson C., Heide M. Speaking of change: Three communication approaches in studies of organizational change. Corporate Communications an International Journal. 2008;13(3):288–305. [Google Scholar]

- Johns Hopkins University . 2020. COVID-19’s historic economic impact, in the U.S. and abroad.https://hub.jhu.edu/2020/04/16/coronavirus-impact-on-european-american-economies/ Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Kang M., Sung M. To leave or not to leave: The effects of perceptions of organizational justice on employee turnover intention via employee-organization relationship and employee job engagement. Journal of Public Relations Research. 2019:1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Kelleher T., Men L.R., Thelen P. Employee perceptions of CEO ghost posting and voice: Effects on perceived authentic leadership, organizational transparency, and employee-organization relationships. The Public Relations Journal. 2019;12(4) [Google Scholar]

- Kim Y. Enhancing employee communication behaviors for sensemaking and sensegiving in crisis situations. Journal of Communication Management. 2018;22(4):451–475. [Google Scholar]

- Kim J.N., Rhee Y. Strategic thinking about employee communication behavior (ECB) in public relations: Testing the models of megaphoning and scouting effects in Korea. Journal of Public Relations Research. 2011;23(3):243–268. [Google Scholar]

- Kraaij V., Garnefski N., Maes S. The joint effects of stress, coping, and coping resources on depressive symptoms in the elderly. Anxiety, Stress, and Coping. 2002;15(2):163–177. [Google Scholar]

- Latack J.C. Coping with job stress: Measures and future directions for scale development. The Journal of Applied Psychology. 1986;71(3):377. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence S.A., Callan V.J. The role of social support in coping during the anticipatory stage of organizational change: A test of an integrative model. British Journal of Management. 2011;22(4):567–585. [Google Scholar]

- Lee Y., Kim J.N. Authentic enterprise, organization-employee relationship, and employee-generated managerial assets. Journal of Communication Management. 2017;21(3):236–253. [Google Scholar]

- Lee Y., Li J.-Y. The value of internal communication in enhancing employees’ health information disclosure intentions in the workplace. Public Relations Review. 2019 [Google Scholar]

- Lee Y., Tao W. Employees as information influencers of organization’s CSR practices: The impacts of employee words on public perceptions of CSR. Public Relations Review. 2020 [Google Scholar]

- Leiter M.P. Coping patterns as predictors of burnout: The function of control and escapist coping patterns. Journal of Organizational Behavior. 1991;12(2):123–144. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis L.K. Employee perspectives on implementation communication as predictors of perceptions of success and resistance. Western Journal of Communication. 2006;70:23–46. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis L.K. Wiley-Blackwell; Chichester, UK: 2011. Organizational change: Creating change through strategic communication. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis L.K., Russ T.L. Soliciting and using input during organizational change initiatives: What are practitioners doing. Management Communication Quarterly. 2012;26(2):267–294. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis L.K., Sahay S. In: The International encyclopedia of strategic communication. Johansen W., Heath R.L., editors. Wiley; 2018. S change communication. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis L.K., Richardson B.K., Hamel S.A. When the “stakes” are communicative: The lamb’s and the lion’s share during nonprofit planned change. Human Communication Research. 2003;29(3):400–430. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis L.K., Schmisseur A.M., Stephens K.K., Weir K.E. Advice on communicating during organizational change: The content of popular press books. The Journal of Business Communication (1973) 2006;43(2):113–137. [Google Scholar]

- Linhart S. PR week.com; 2011. Job one: Keeping employees happy and engaged.http://www.prweekus.com/job-one-keeping-employees-happy-and-engaged/article/207660/ Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Liu B.F., Bartz L., Duke N. Communicating crisis uncertainty: A review of the knowledge gaps. Public Relations Review. 2016;42(3):479–487. [Google Scholar]

- Magala S., Frahm J., Brown K. First steps: Linking change communication to change receptivity. Journal of Organizational Change Management. 2007;20(3):370–387. [Google Scholar]

- Malopinsky L.V., Osman G. Dimensions of organizational change. Handbook of human performance technology. 2006;3:262–286. [Google Scholar]

- Meaney M., Pung C. McKinsey global results: Creating organizational transformations. The McKinsey Quarterly. 2008;7(3):1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Men L.R. Internal reputation management: The impact of authentic leadership and transparent communication. Corporate Reputation Review. 2014;17(4):254–272. [Google Scholar]

- Men L.R., Jiang H. Cultivating quality employee-organization relationships: The interplay among organizational leadership, culture, and communication. International Journal of Strategic Communication. 2016;10(5):462–479. [Google Scholar]

- Men L.R., Stacks D. The effects of authentic leadership on strategic internal communication and employee-organization relationships. Journal of Public Relations Research. 2014;26(4):301–324. [Google Scholar]

- Men L.R., Yue C.A. Creating a positive emotional culture: Effect of internal communication and impact on employee supportive behaviors. Public Relations Review. 2019;45(3) [Google Scholar]

- Men L.R., Yue C.A., Liu Y. “Vision, passion, and care:” the impact of charismatic executive leadership communication on employee trust and support for organizational change. Public Relations Review. 2020 [Google Scholar]

- Milliken F.J. Three types of perceived uncertainty about the environment: State, effect, and response uncertainty. The Academy of Management Review. 1987;12(1):133–143. [Google Scholar]

- Oreg S., Bartunek J.M., Lee G., Do B. An affect-based model of recipients’ responses to organizational change events. The Academy of Management Review. 2018;43(1):65–86. [Google Scholar]

- Rafferty A.E., Griffin M.A. Perceptions of organizational change: A stress and coping perspective. The Journal of Applied Psychology. 2006;91(5):1154. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.91.5.1154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rawlins B. Give the emperor a mirror: Toward developing a stakeholder measurement of organizational transparency. Journal of Public Relations Research. 2008;21(1):71–99. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson O., Griffiths A. Coping with the stress of transformational change in a government department. The Journal of Applied Behavioral Science. 2005;41(2):204–221. [Google Scholar]

- Rogiest S., Segers J., van Witteloostuijn A. Climate, communication and participation impacting commitment to change. Journal of Organizational Change Management. 2015;28(6):1094–1106. [Google Scholar]

- Schermerhorn J.R., Osborn R., Hunt J.G. Wiley; New York: 2003. Organizational behavior. [Google Scholar]

- Schnackenberg A.K., Tomlinson E.C. Organizational transparency: A new perspective on managing trust in organization-stakeholder relationships. Journal of Management. 2016;42(7):1784–1810. [Google Scholar]

- Seeger M.W., Ulmer R.R., Novak J.M., Sellnow T. Post‐crisis discourse and organizational change, failure and renewal. Journal of Organizational Change Management. 2005;18:78–95. [Google Scholar]

- Shaw M. In: Global encyclopedia of public administration, public policy, and governance. Farazmand A., editor. Springer; 2018. Unplanned change and crisis management. [Google Scholar]

- Shin J., Taylor M.S., Seo M.G. Resources for change: The relationships of organizational inducements and psychological resilience to employees’ attitudes and behaviors toward organizational change. The Academy of Management Journal. 2012;55(3):727–748. [Google Scholar]

- Shore L.M., Tetrick L.E., Taylor M.S., Shapiro J.A.M.C., Liden R.C., Parks J.M., et al. 2004. The employee-organization relationship: A timely concept in a period of transition research in personnel and human resources management. [Google Scholar]

- Srivastava R., Tang T.L.P. Coping intelligence: Coping strategies and organizational commitment among boundary spanning employees. Journal of Business Ethics. 2015;130(3):525–542. [Google Scholar]

- Stevens, J. (1992). Applied multivariate statistics for the social sciences (2nd ed.). Hillsdale, NJ: Earlbaum.

- Stolovitch H.D., Keeps E.J. Pfeiffer; 1992. Handbook of human performance technology: A comprehensive guide for analyzing and solving performance problems in organizations. [Google Scholar]

- Tao W., Song B., Ferguson M.A., Kochhar S. Employees’ prosocial behavioral intentions through empowerment in CSR decision-making. Public Relations Review. 2018;44(5):667–680. [Google Scholar]

- Thau S., Bennett R.J., Mitchell M.S., Marrs M.B. How management style moderates the relationship between abusive supervision and workplace deviance: An uncertainty management theory perspective. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes. 2009;108(1):79–92. [Google Scholar]

- The United States Census Bureau . 2018. People and population.https://data.census.gov/cedsci/profile?q=United%20States&g=0100000US Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Thelen P.D. Supervisor humor styles and employee advocacy: A serial mediation model. Public Relations Review. 2019;45(2):307–318. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics . 2020. Unemployment rate rises to record high 14.7 percent in April 2020.https://www.bls.gov/opub/ted/2020/unemployment-rate-rises-to-record-high-14-point-7-percent-in-april-2020.htm#:-:text=Unemployment%20rate%20rises%20to%20record%20high%2014.7%20percent%20in%20April%202020&text=The%20unemployment%20rate%20in%20April,available%20back%20to%20January%201948 Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Vakola M., Nikolaou I. Attitudes towards organizational change. Employee Relations. 2005;25(2):160–174. [Google Scholar]

- Weick K.E. Sage; Thousand Oaks, CA: 1995. Sensemaking in organizations. [Google Scholar]

- Weick K.E., Sutcliffe K.M., Obstfeld D. Organizing and the process of sensemaking. Organization Science. 2005;16(4):409–421. [Google Scholar]

- Welch M., Jackson P.R. Rethinking internal communication: A stakeholder approach. Corporate Communications an International Journal. 2007;12(2):177–198. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization . 2020. COVID-19 situation reports-102.https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/situation-reports/20200501-covid-19-sitrep.pdf?sfvrsn=742f4a18_2 Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Yue C.A., Men L.R., Ferguson M.A. Bridging transformational leadership, transparent communication, and employee openness to change: The mediating role of trust. Public Relations Review. 2019;45(3) [Google Scholar]

- Zellars K.L., Liu Y., Bratton V., Brymer R., Perrewé P.L. An examination of the dysfunctional consequences of organizational injustice and escapist coping. Journal of Managerial Issues. 2004:528–544. [Google Scholar]