Abstract

Objectives

The International Valuation Protocol for the valuation of the EQ-5D-Y-3L provides baseline guidance, but country-specific context is also important. This study aimed to obtain US stakeholders’ input on key considerations for youth valuation in the US.

Methods

A total of 14 stakeholders representing various backgrounds were identified via the investigators’ networks. A 2-h online meeting was held to discuss (1) the need for a US value set for the EQ-5D-Y-3L; (2) willingness to pay more for quality-adjusted life-year (QALY) gains for children versus adults; (3) sampling strategies; (4) framing perspectives; and (5) other challenges. The session was recorded, transcribed, and summarized.

Results

Several stakeholders supported paying more for QALY gains for children in recognition of their potential future contributions to society, as well as to avoid potential undervaluation and promote access to innovative treatments. Concerns regarding possible double counting, lack of data to showcase long-term benefits, and dangers of paying more for certain subgroups were also expressed. Most of the stakeholders felt that adolescents could relate to a 10-year-old’s perspective better than adults and were capable of self-completing valuation tasks, and thus should be directly included in the valuation study. There were concerns that adults would be inconsistent in their views about a 10-year-old, partly depending on their status as a parent.

Conclusions

US stakeholders provided insights relevant to youth valuation in a US context and were open to continued dialogue with investigators. This study could be useful to investigators who are conducting youth valuation studies in different countries and seeking stakeholder input.

Key Points for Decision Makers

| US stakeholders provided valuable input on key considerations in valuation of the EQ-5D-Y-3L. |

| Engagement of national stakeholders is an important step for investigators pursuing valuation studies in their countries. |

Introduction

The EQ-5D-Y-3L is a generic, preference-based instrument for measuring health-related quality of life (HRQoL) in children and adolescents, which was developed by the EuroQol Research Foundation in 2009 [1]. Similar to the adult version of the EQ-5D-3L, the EQ-5D-Y-3L describes health in terms of five dimensions, albeit using more child-friendly language: (1) mobility; (2) looking after myself; (3) doing usual activities; (4) having pain or discomfort; and (5) feeling worried, sad, or unhappy. As such, the EQ-5D-Y-3L is intended for self-completion in youth aged 8–15 years and completion by proxy in ages 4–7 years. Each dimension has three levels of severity, ranging from no problems to a lot of problems, describing a total of 243 health states.

Like other EQ-5D instruments, some of the intended uses for the EQ-5D-Y-3L instrument include clinical research and practice, population health surveys, and economic evaluations. However, despite similarities to adult instruments, it is noted that value sets representing preference weights for adult health states may not be appropriate to calculate index values for children [1]. Therefore, separate value sets with country-specific values for each of the 243 health states should be developed for the EQ-5D-Y-3L. To this end, an international protocol for conducting valuation tasks and producing value sets for the EQ-5D-Y-3L was developed and published in 2020, serving as baseline guidance to investigators pursuing valuation studies [2]. This protocol recommends elicitation of health state preferences from adults from the general population (e.g., voters, taxpayers) through discrete choice experiments (DCEs) and composite time trade-off (cTTO) tasks. These tasks are framed using the perspective of a hypothetical 10-year-old child (e.g., “Considering your views about a 10-year-old child, what do you prefer?”). This approach enables the estimation of latent scale values through DCEs and anchoring them onto a 0–1 health utilities scale from cTTO data (with 0 = dead and 1 = full health). To date, adapting guidance from the international protocol, EQ-5D-Y-3L valuation studies have been completed and published by teams from multiple countries, including Japan [3], Slovenia [4], Spain [5], Germany [6], Hungary [7], and The Netherlands [8]. Additional valuation studies are underway in approximately a dozen countries, including the United States (US).

While the published International Valuation Protocol for the EQ-5D-Y-3L provides guidance, youth valuation is associated with unique challenges compared with adult valuation tasks, which may differ across countries and settings [9, 10]. Several of these challenges have been brought to light by early valuation efforts, and additional research to address the remaining methodological questions is ongoing. For example, some adult respondents to cTTO tasks using a 10-year-old framing perspective have been reluctant to trade-off life-years for children, even for poor health states, resulting in value sets with compressed utility scales and QALY gains for health interventions for children compared with adults [9, 11, 12]. Two central questions related to these observations are (1) whose preferences should be used in youth valuation studies; and (2) how should valuation tasks be framed [12, 13]? Recent research has explored these questions in depth using a mixture of quantitative and qualitative methods to assess the impacts of using adult or youth (with varying ages) framing perspectives for valuation tasks [11, 14–17]. Despite this empirical evidence, there is no consensus or clearly emerging, uniform methodological approach that could be recommended for all future EQ-5D-Y-3L valuation studies. These are largely normative considerations requiring judgment from individual investigators while considering the types of decisions that will be informed by the use of value sets in their countries [9, 12].

Considering the challenges in youth valuation, health technology assessment (HTA) bodies may provide insights that can fill the gaps. However, currently no HTA bodies provide standardized guidance on how to value HRQoL in youth [9]. Considering this gap, engagement of local stakeholders, who could include individuals from HTA bodies, decision makers, or other end-users of value sets, may be desirable to inform country-specific youth valuations. Based on a 3-day workshop of EQ-5D-Y-3L valuation investigators, an agreement was reached that such engagement would be desirable [12]. At the same time, it was also reported that most investigators had limited contact with local stakeholders, including their respective HTA bodies. As such, there is currently no established best practice for engaging stakeholders for this purpose, and there are remaining questions about which stakeholders ought to be consulted and their level of awareness of the relevant challenges to valuing youth HRQoL. In the US, HTA plays a distinct function in informing health technology pricing rather than reimbursement decisions, and third-party payers and patients play a more prominent role in guiding health policy. Towards preparation for a US valuation study of the EQ-5D-Y-3L, it was deemed particularly important to elicit opinions from a diverse group of stakeholders to provide guidance on selected challenges to valuing HRQoL in youth. This paper reports the process of stakeholder engagement by US investigators and summarizes the results from a roundtable discussion. Findings herein synthesize key considerations from stakeholders with guidance in the international protocol to make informed decisions in approaching an EQ-5D-Y-3L valuation study in the US.

Methods

Key stakeholders were identified from investigators’ networks and purposively sampled to represent varied viewpoints and expertise. Through discussions among US investigators, stakeholders from the following backgrounds were determined to be relevant and represent broad coverage of expertise and background for the purpose of the discussion: (1) pediatric clinicians and researchers; (2) individuals from HTA bodies; (3) third-party payers; (4) laypersons with lived experiences caring for or working with children; (5) academics with health economics and outcomes research (HEOR) experience; and (6) HEOR professionals from consulting, pharmaceutical, or medical device companies. As a result, 14 stakeholders were invited to participate.

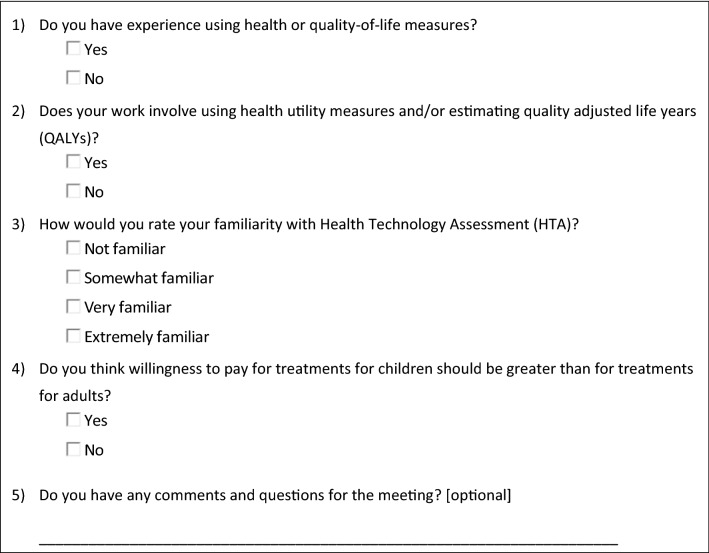

Prior to the meeting, participants were provided with a written overview of the EQ-5D-Y-3L and meeting objectives highlighting the purpose of stakeholder engagement as a key step in the valuation study process. Additionally, participants were provided videos summarizing the EQ-5D descriptive systems and relevant published literature selected by investigators to familiarize them with relevant challenges in youth health valuation [15, 18]. In addition, to gain further insight into the participants’ backgrounds and general knowledge on health valuation, investigators designed and distributed a 5-item survey (Fig. 1). Findings from this survey were analyzed descriptively prior to the meeting.

Fig. 1.

Pre-meeting survey questions

The 2-h online roundtable discussion was conducted on 7 April 2022. The first 30 min were devoted to providing background information, including (1) an overview of HRQoL measurement; (2) the EQ-5D-Y-3L instrument; (3) valuation study methodology; and (4) challenges in youth health valuation, including preference source (who is asked to participate in the valuation exercises), and framing perspective (whose health is being valued in valuation exercises). The remaining 90 min were devoted to semi-structured discussions around prespecified questions. These questions were generated through iterative discussions between the US investigators and members of the EuroQol Group’s Younger Populations Working Group (YPWG). The list of questions was refined to (1) reflect content deemed by investigators to be most relevant to a valuation study in the US; (2) be comprehensible to stakeholders from different backgrounds; and (3) be adequately addressed during a 90 min discussion. Eight discussion questions or prompts were ultimately selected (Table 1).

Table 1.

Roundtable discussion questions

| Discussion question |

|---|

|

1. Need assessment: Based on the pre-survey information, some of you use QALYs in your work. In the US context, is it useful to have a measure that can generate health utilities specifically for children? |

|

2. Willingness to pay: In allocating healthcare resources (e.g., taxpayer dollars) based on HTA evidence, should children's health be assigned a premium (be willing to pay more to extend 1 year of life/QALY) compared with adults? |

|

3. Who should we ask: Typically, we ask the general adult population (taxpayers) when valuing measures of health for adults. In valuing measures of children's health, who should we engage from the general population as respondents? ▪ Children/adolescents ▪ Adults ▪ A combination |

|

4. Which perspective: When valuing health states that vary in severity, general population respondents are typically asked to imagine themselves in those health states. Adults tend to value health states differently when trading off life years and quality-of-life associated with a child’s health (for example, a 10-year-old child). In your view, which perspective is most appropriate in terms of framing a valuation exercise: ▪ Adult (own) perspective? ▪ 10-year-old child perspective? |

|

5. Multiple value sets: There is the potential to produce multiple value sets as opposed to only one value set for all children. This may pose issues: ▪ Transitioning between measures for different age groups ▪ Selection/gaming of value sets How should we navigate these issues? Should we designate a ‘reference case’; which source and which perspective? |

|

6. Sampling approach: In terms of our sampling strategy for this study, we plan to conduct quota-based sampling based on racial/ethnic groups, age, and gender to have a nationally representative sample. Are there other considerations regarding the quota-based sampling strategy? ▪ e.g., Adolescents |

|

7. Whose child: Some respondents indicate they would answer differently if it were their child versus someone else’s child. What is the appropriate perspective to take? |

|

8. Additional challenges: What are the challenges you foresee in utilizing health preference values specifically for children? Are there any other points you wish to bring up for further discussion? |

HTA health technology assessment, QALY quality-adjusted life-year

During the meeting, to maintain meeting flow and give all participants an opportunity to speak, selected stakeholders were designated to respond to each posed discussion question before opening the discussion to the larger group. Participants were encouraged to respond to points made by other stakeholders, including through written comments in the chat box or post-meeting reflections to investigators via email. The investigators served as discussion moderators, asking follow-up, probing questions to stimulate further discussion. Members of the YPWG provided clarifications and answered questions posed by participants as needed. The 90 min discussion was recorded and transcribed.

After the meeting, investigators independently reviewed the meeting transcription and additional written contributions received from participants, including the comments obtained from the chat box from the meeting and follow-up emails. While reviewing these materials, each investigator made notes to categorize participant responses, as participant comments and responses often covered multiple topics beyond the prompt. A week later, the investigators then convened to review and discuss these notes and come to agreement on distillation of content to organize results into key findings relating to major themes.

Each stakeholder was offered an honorarium for their participation. Ethical approval for the study was obtained from the University of San Francisco Institutional Review Board (IRB; #1702).

Results

In total, all 14 approached stakeholders consented to participate in the roundtable discussion (Table 2). Additionally, 2 members of the YPWG and 3 US investigators were present, for a total of 19 participants.

Table 2.

Stakeholder backgrounds

| Stakeholder number | Background |

|---|---|

| 001 | Health services research in children’s health |

| 002 | Health services research in children’s health |

| 003 | Pediatric clinician and health services research |

| 004 | Health services research in children’s health |

| 005 | HTA body |

| 006 | HEOR in academia |

| 007 | HEOR consulting |

| 008 | HEOR in pharmaceutical industry |

| 009 | HEOR in pharmaceutical industry |

| 010 | HEOR in pharmaceutical industry |

| 011 | Medical device industry |

| 012 | Third-party payer |

| 013 | Layperson—caregiver of child with rare disease |

| 014 | Layperson—early childhood educator |

HEOR health economics and outcomes research, HTA health technology assessment

Of the stakeholders, 13/14 (93%) returned completed pre-meeting surveys. Survey results indicated that 10/13 (77%) participants had experiences using HRQoL measures, and 7/13 (54%) of them use health utility measures and/or estimate QALYs for their work. Furthermore, 8/13 (62%) participants were ‘very’ or ‘extremely’ familiar with HTA. 7/12 (58%) participants thought willingness-to-pay for treatments for children should be greater than for treatments for adults.

After the meeting, investigators distilled and summarized the roundtable discussion into three main themes: (1) the first was a discussion of whether, in the context of valuing new health technologies, society should be willing to pay more for QALY improvements in youth than adults; (2) the second theme related to who should be included in the study as sources of preferences, and the framing perspective valuation tasks should take; and (3) stakeholders discussed approaches to quota sampling respondents for the valuation study, and how they would foresee using a resulting EQ-5D-Y-3L value set. Each of these themes are discussed below.

Willingness-to-Pay for Quality-Adjusted Life-Year Gains for Children Compared with Adults

During the roundtable discussion, we invited participants to elaborate on their views as to whether society should be willing to pay more per QALY gained for children compared with adults. Those in favor of paying more per QALY for children described their support based on children’s potential future contribution to society over their prospective lifetime. Most of the respondents qualified their support for paying more per QALY for children by recognizing that there is an innate emotional response to prioritizing health resources benefitting children versus adults. Conversely, stakeholders who held the view that society should not pay more per QALY for children, especially those with HTA and health economics backgrounds, expressed concerns that the use of QALYs in cost effectiveness may already account for the additional years of life children are expected to live, effectively leading to double counting. Other stakeholders mentioned that there is lack of data to suggest long-term benefits by allocating more resources towards QALY gains for children than for adults, as well as the dangers of a precedent of being willing to pay more for health gains for certain subgroups of society over others (for example, prioritizing healthcare resources for children compared with the elderly).

Sources of Preferences and Framing Perspective of Valuation Tasks

A substantial portion of the discussion was devoted to debating the selection of participants for a US valuation study (sources of preferences), and how DCE and cTTO tasks would be described to participants in terms of whose health they would imagine (framing perspective). The international protocol recommends that DCE and cTTO tasks are to be framed in terms of a 10-year-old child. Stakeholders identified several challenges with this approach. First, older adults may lack the capacity to identify with a 10-year-old child in order to provide meaningful responses to valuation exercises. Stakeholders also questioned whether adult preferences for a 10-year-old would be systematically impacted by certain characteristics, such as whether respondents had children, and the number, ages, and health status of those children. As such, a solution supported by many stakeholders was to include children or adolescents directly as participants in the valuation study. Stakeholders in support of this possibility suggested that while 10-year-old children may be too young to participate in valuation tasks to match the framing perspective, adolescents would be closer in age and experience to a 10-year-old and would have more informed preferences. Additionally, they felt that adolescents would be capable of providing valid responses to valuation tasks. Stakeholders also expressed how adolescent preferences would more closely align with the instrument’s intended use to measure HRQoL in youth populations. At the same time, some misconceptions were expressed by several participants in reconciling these viewpoints with the intention of producing a US value set representing a societal viewpoint rather than an individual patient-level viewpoint. Stakeholders more familiar with HTA and the intentions of producing a value set for use in cost effectiveness were more inclined to favor adult respondents. They emphasized that children and adolescents do not vote or pay taxes, and that adults aged 18 years and older make decisions on their behalf in terms of healthcare and resource allocation. Thus, these stakeholders were more inclined to limit respondents to adults, with tasks framed from either their own perspective or from a 10-year-old child’s perspective (with recognition of the potential challenges this framing perspective could pose).

Sampling Approach and Value Set Selection

Building off the discussion about sources of preferences and framing perspectives, stakeholders offered insight into potential methodological guidance for the US valuation study. The majority of stakeholders thought inclusion of adolescent preferences, either alone or in addition to adult preferences, was important. For example, a few stakeholders suggested weighting the proportion of adolescent respondents to their representativeness of the US population. Stakeholders also highlighted the importance of collecting background information from adult respondents on whether they were parents of children, and how that role may have influenced their responses to valuation exercises. For instance, they pointed out that experiences caring for ill children, or their religious background, may also influence valuation of children’s health. However, stakeholders recognized that it may be infeasible to quota sample based on these characteristics. Despite a lack of agreement on who to include and what framing perspective to take for the valuation study, stakeholders generally did not support producing multiple US EQ-5D-Y-3L value sets. This view was out of concern that end-users may be confused on proper selection or may default to using whichever value set would produce most favorable QALY gains for their purpose.

Discussion

US stakeholders provided insights relevant to informing a valuation study of the EQ-5D-Y-3L in the US. Stakeholders offered multiple perspectives surrounding paying more for QALYs for youth compared with adults, whose preferences matter, how valuation tasks should be framed, and the future utilization of the US EQ-5D-Y-3L value set once it is generated .

The discussion around willingness-to-pay for QALY gains in youth compared with adults was of interest to US investigators for several reasons. First, this was constructive in forming the basis for discussion of the relevance of valuing youth’s HRQoL, where one potential real-world application of a value set could be used in QALY estimation and pricing decisions for increasingly costly, novel therapies for rare diseases in children. Second, one methodological nuance of great importance to the investigators is that based on some investigators’ experiences thus far, adults may be unwilling to trade-off years of life for children in cTTO tasks, even in considering poor health. This could result in a value set with fewer values below 0 (health states considered ‘worse than dead’) [3, 11, 12]. This could inadvertently create issues with the comparability of economic evaluations in children compared with adults, or considering children aging to adulthood, due to differences in the comparability of the range of utility values represented by each value set. Effectively, this would lead to inherently valuing child QALYs differently from adults, which many stakeholders were against. This discussion around willingness to pay revealed stakeholders’ expectations regarding the relative importance of comparability of a resulting youth and existing adult value set.

This roundtable discussion also revealed other insights in terms of methodological changes to the US EQ-5D-Y-3L valuation study protocol. Stakeholders with greater familiarity with valuation study conventions and HTA experience favored inclusion of exclusively adult respondents, with tasks framed from their own perspective to closely align with a voter or taxpayer perspective. At the same time, the majority of stakeholders were in favor of including a subset of adolescent respondents directly in the valuation task and felt them capable of providing valid responses. Research has shown that adolescents provide valid responses to DCE tasks from their own perspectives, and that their results differ from adults considering a hypothetical 10-year-old child’s perspective [19]. On the other hand, conventional studies have also avoided inclusion of children or adolescents in cTTO exercises, given both the greater complexity of these tasks and the potential difficulty of receiving ethical approval [10]. Alone, adolescent DCE responses would only allow for latent values without anchoring at 0 (dead) or 1 (full health) as required for QALY estimation [2, 10]. Thus, the implications of how adolescents’ DCE responses would be utilized in combination with adult responses in modeling of a final US EQ-5D-Y-3L value set remains unclear.

The fact that we obtained mixed opinions from stakeholders on the path forward for a US EQ-5D-Y-3L valuation study was not surprising. Inclusion of US stakeholders of diverse backgrounds and experiences may have precluded any possibility of reaching 100% consensus, as each had their own priorities and considerations. It is important to point out that the discussion questions and prompts were not designed with the intent of reaching a consensus but rather to stimulate an exploration of relevant topics by US stakeholders. The diversity of opinions about the ‘correct’ approach to youth health valuation highlights the different expectations that stakeholders hold when ultimately evaluating the results of the valuation study and determining their ‘buy-in’ for the resulting value set. The discussion was productive to stimulate a dialogue around the degree of understanding or misunderstanding regarding methodological considerations in youth health valuation. It was equally beneficial to educate ourselves and each other with respect to the multiple players involved in healthcare decision making in the US context. The US healthcare system contrasts with many other countries where demonstrating cost effectiveness is critical for the approval and reimbursement of health technologies. US stakeholders contextualized their viewpoints as they related to US payers (both private and public), as well as health technology manufacturers, who may consider cost effectiveness of treatments as only one of the parameters in pricing decisions.

There are some limitations associated with this study that future investigators may wish to consider before engaging stakeholders. For example, our approach included a small, purposive sample (n = 14) that potentially failed to capture the full extent of viewpoints from interested parties or the general public. We also did not consider geographical or regional differences when selecting stakeholders to include. Although we conceptualized a relatively balanced sample of stakeholders from several discrete areas of expertise, in reality, our stakeholders had extensive experience beyond their current roles. As a result, certain expertise and perspectives were likely more represented than others. Methods such as the Delphi technique could have been explored to establish relative importance weights relating to the discussion points and reach more actionable, prioritized decisions, although at the cost of more time and resource investment. Discussion questions and prompts were particularly designed to address the EQ-5D-Y-3L in QALY estimation and cost-effectiveness analyses. Other uses of the EQ-5D-Y-3L and resulting value sets, including producing profile scores as a means to summarize health, were not explicitly considered. Investigators pursuing similar studies may wish to modify their discussion questions to allow broader coverage beyond economic evaluations, depending on the intended use of a value set in their countries. Our approach served our aim to stimulate a qualitative exploration of feasibility, validity, and prioritization related to proceeding with a valuation study of the EQ-5D-Y-3L in the US, although more structured qualitative analysis may have enabled a more thorough understanding of the data, potentially uncovering additional themes warranting discussion. Other youth valuation study investigators may consider more robust methods for qualitative analysis of views expressed by stakeholders, such as a formal content analysis.

To reflect further, the process of stakeholder engagement conducted in the US could be beneficial to investigators of future EQ-5D-Y-3L valuation studies conducted in other countries. For example, we found that stakeholders held varying levels of baseline familiarity with the EQ-5D-Y-3L or health state valuation in general. Although efforts were made to equip participants with the basic knowledge to prepare for the roundtable discussion by providing pre-meeting materials and a 30-min introductory presentation, there were still misconceptions expressed by some participants, requiring additional time by moderators to provide clarifications. Providing additional literature prior to the meeting may have helped to familiarize stakeholders with the relevant issues in more depth, although we were also cognizant of the level of participant burden related to pre-meeting preparation. If they have the available resources, investigators in other countries may want to organize longer educational workshops prior to their stakeholder engagement. Furthermore, our discussion exposed stakeholders to potential study options with which they may not have been otherwise familiar, heightening awareness for possibilities that may ultimately meet some of their needs better than others. Future efforts to engage stakeholders for EQ-5D-Y-3L valuation studies should be aware of the need to strike a careful balance of educating and informing participants—who may have more limited understanding of the topic of interest, HTA processes, and other relevant issues—without swaying their views. Ultimately, given stakeholders’ different needs and opinions about youth health valuation, it may be impossible to meet everyone’s expectations with one study in a single setting.

The breadth of input provided by stakeholders in this study highlights the benefit of engaging local stakeholders as an initial step in conducting valuation studies. Notably, this also emphasizes the role of an international protocol in valuation studies as a baseline guidance, rather than a recipe for conducting a successful study. The shortcomings of a one-size-fits-all international protocol are that it does not accommodate country-specific contextual factors, which should be considered by investigators with input from national stakeholders in order to heighten the relevance and applicability of a preference-based measure. This is especially important considering the complexities and remaining uncertainties involved in capturing societal preferences for youth HRQoL for use in cost-effectiveness analysis. Insights from stakeholders have been incorporated into the subsequent US valuation study methodology, with the most notable deviation from the international protocol being the inclusion of adolescent participants to elicit preferences through DCEs. Based on stakeholders’ feedback, additional questions were also implemented to collect background information from adult participants, such as whether they have children and if their children have experience with illness, to examine how these factors influence value outcomes. Importantly, all of the US stakeholders also indicated that they would be open to continued dialogue with investigators, and were interested in a future, follow-up meeting. Investigators are planning to re-engage stakeholders after the valuation study to assess their opinions on the methods that were used.

There is need to advance the field of youth health valuation in various ways, including deciding whose preferences, and which preference elicitation methods, are best fit for purpose [12]. Stakeholder engagement can serve as complementary to ongoing empirical work in these areas where there is no clear right or wrong answer. Stakeholder engagement is an additional source of insight than can assist instrument developers in improving methodology and enhancing the relevance of their work. This is the first publication to summarize some of the important considerations and findings in engaging national stakeholders in the process of conducting an EQ-5D-Y-3L valuation study. Other stakeholder engagement initiatives are currently underway by investigators of the EQ-5D-Y-3L valuation studies in the UK and Canada, where HTA bodies have a substantial role in reimbursement decisions. Furthermore, based on reflections from a recent 3-day workshop of EQ-5D-Y-3L valuation investigators, the EuroQol Research Foundation now recommends investigators to engage or consult country-specific decision makers during the planning stages of youth valuation [12]. Thus, the results of this study may be used as a reference to the types of stakeholders to engage and questions that may be asked to elicit insightful responses in consideration of the valuation of child and adolescent health.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Drs. Oliver Rivero-Arias, Juan Manuel Ramos-Goñi, and Mark Oppe, who are co-investigators of the US EQ-5D-Y-3L valuation study. The authors would also like to thank Drs. Nancy Devlin, Mike Herdman, and Elly Stolk for their valuable input in preparing and executing this stakeholder discussion. This study was funded by the EuroQol Research Foundation (Grant #409-RA).

Declarations

Funding

This study was funded by the EuroQol Research Foundation (Grant #409-RA)

Conflict of interest

Jonathan Nazari is a health economics and outcomes research (HEOR) fellow sponsored by the University of Illinois at Chicago and Pfizer Inc. Simon Pickard is a professor at the University of Illinois at Chicago, a partner at Maths in Health and Second City Outcomes Research consulting, and a member of the EuroQol Research Foundation. Ning Yan Gu is an adjunct professor at the University of San Francisco, a director of HEOR at Exact Sciences, and a member of the EuroQol Research Foundation.

Ethics approval

Ethical approval for this study was obtained from the University of San Francisco IRB (#1702). The procedures used in this study adhere to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Consent to participate and publish

Informed consent to participate and utilize data for research purposes, including publication, was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Data availability statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

Code availability

Not applicable.

Author contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation and data collection and analysis were performed by JLN, ASP and NYG. The first draft of the manuscript was written by JLN, and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Disclosure

This article is published in a special edition journal supplement wholly funded by the EuroQol Research Foundation.

References

- 1.Wille N, Badia X, Bonsel G, et al. Development of the EQ-5D-Y: a child-friendly version of the EQ-5D. Qual Life Res. 2010;19:875–886. doi: 10.1007/s11136-010-9648-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ramos-Goñi JM, Oppe M, Stolk E, et al. International Valuation Protocol for the EQ-5D-Y-3L. Pharmacoeconomics. 2020;38:653–663. doi: 10.1007/s40273-020-00909-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shiroiwa T, Ikeda S, Noto S, et al. Valuation survey of EQ-5D-Y based on the International Common Protocol: development of a value set in Japan. Med Decis Mak. 2021;41:597–606. doi: 10.1177/0272989X211001859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Prevolnik Rupel V, Ogorevc M, Greiner W, et al. EQ-5D-Y value set for Slovenia. Pharmacoeconomics. 2021;39:463–471. doi: 10.1007/s40273-020-00994-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ramos-Goñi JM, Oppe M, Estévez-Carrillo A, et al. Accounting for unobservable preference heterogeneity and evaluating alternative anchoring approaches to estimate country-specific EQ-5D-Y value sets: a case study using spanish preference data. Value Health. 2022;25:835–843. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2021.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kreimeier S, Mott D, Ludwig K, et al. EQ-5D-Y value set for Germany. PharmacoEconomics. 10.1007/s40273-022-01143-9. (Epub 23 May 2022).

- 7.Rencz F, Ruzsa G, Bató A, et al. Value set for the EQ-5D-Y-3L in Hungary. PharmacoEconomics. 10.1007/s40273-022-01190-2. (Epub 20 Sep 2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8..Roudijk B, Sajjad A, Essers B, et al. A value set for the EQ-5D-Y-3L in the Netherlands. PharmacoEconomics. 10.1007/s40273-022-01192-0. (Epub 10 Oct 2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Devlin NJ. Valuing child health isn’t child’s play. Value Health. 2022;25(7):1087–1089. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2022.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kreimeier S, Greiner W. EQ-5D-Y as a health-related quality of life instrument for children and adolescents: the instrument's characteristics, development, current use, and challenges of developing its value set. Value Health. 2019;22:31–37. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2018.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dewilde S, Janssen MF, Lloyd AJ, et al. Exploration of the reasons why health state valuation differs for children compared with adults: a mixed methods approach. Value Health. 2022;25(7):1185–1195. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2021.11.1377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Devlin N, Pan T, Kreimeier S, Verstraete J, Stolk E, Rand K, et al. Valuing EQ-5D-Y: the current state of play. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2022;20(1):105. doi: 10.1186/s12955-022-01998-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kreimeier S, Oppe M, Ramos-Goñi JM, et al. Valuation of EuroQol Five-Dimensional Questionnaire, Youth Version (EQ-5D-Y) and EuroQol Five-Dimensional Questionnaire, Three-Level Version (EQ-5D-3L) health states: the impact of wording and perspective. Value Health. 2018;21:1291–1298. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2018.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lipman S, Reckers-Droog V, Kreimeier S. Think of the children: a discussion of the rationale for and implications of the perspective used for EQ-5D-Y Health State Valuation. Value Health. 2021;24(7):976–982. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2021.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lipman SA, Reckers-Droog VT, Karimi M, et al. Self vs. other, child vs. adult. An experimental comparison of valuation perspectives for valuation of EQ-5D-Y-3L health states. Eur J Health Econ. 2021;22:1507–1518. doi: 10.1007/s10198-021-01377-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ramos-Goñi JM, Estévez-Carrillo A, Rivero-Arias O, et al. Does changing the age of a child to be considered in 3-level version of EQ-5D-Y discrete choice experiment-based valuation studies affect health preferences? Value Health. 2022;25(7):1196–1204. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2022.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Reckers-Droog V, Karimi M, Lipman S, et al. Why do adults value EQ-5D-Y-3L health states differently for themselves than for children and adolescents: a think-aloud study. Value Health. 2022;25(7):1174–1184. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2021.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Helgesson G, Ernstsson O, Åström M, et al. Whom should we ask? A systematic literature review of the arguments regarding the most accurate source of information for valuation of health states. Qual Life Res. 2020;29:1465–1482. doi: 10.1007/s11136-020-02426-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mott DJ, Shah KK, Ramos-Goñi JM, et al. Valuing EQ-5D-Y-3L health states using a discrete choice experiment: do adult and adolescent preferences differ? Med Decis Mak. 2021;41:584–596. doi: 10.1177/0272989X21999607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.