Abstract

Background

Antibiotic resistance is a significant problem in the world, so optimization of antibiotic use is needed. Klebsiella pneumoniae is a Gram-negative bacterium that causes bacteremia, sepsis, UTIs, pneumonia, nosocomial infections and ESBL-producing bacterium. ciprofloxacin, cotrimoxazole, and doxycycline are broad-spectrum antibiotics, including in WHO essential drugs.

Objective

The study tested antibiotics that most effectively inhibited Klebsiella pneumoniae non-ESBL, Klebsiella pneumoniae ESBL invitro with time-kill curve analysis.

Method

This experiment used Klebsiella pneumoniae ATCC isolates, stored clinical isolates of Klebsiella pneumoniae non-ESBL, Klebsiella pneumoniae ESBL, and the control group. Isolates other than control were challenged with ciprofloxacin, cotrimoxazole, and doxycycline oral preparations with concentrations of 1, 2, 4 MIC at 0, 2, 4, 6, 8, 24 h. At each hour, the bacteria were cultured, incubated, calculated the number of colonies. The results were analyzed with time-kill curve and tested statistics. Statistical analysis used included ANOVA, post-Hoc, Mann Whitney, and Kruskal Willis tests with p < 0.05.

Results

Ciprofloxacin, cotrimoxazole, and doxycycline in this study had inhibition effects on Klebsiella pneumoniae non-ESBL and Klebsiella pneumoniae ESBL. Ciprofloxacin had the best inhibitory effect. Statistically, the most meaningful differences of antibiotics in ciprofloxacin and cotrimoxazole at four and 24 h (p < 0.001), in concentrations of 1 MIC and 4 MIC at 2 h (p < 0.001), and in Klebsiella pneumoniae ESBL and Klebsiella pneumoniae ATCC at 8 h (p = 0.024).

Conclusion

Ciprofloxacin is the best antibiotic to inhibit the growth of Klebsiella pneumoniae non-ESBL and Klebsiella pneumoniae ESBL compared to cotrimoxazole and doxycycline. The inhibitory effect increases with an increase in concentration.

Keywords: Ciprofloxacin, Cotrimoxazole, Doxycycline, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Time-kill curve

Highlights

-

•

Ciprofloxacin is effective in inhibiting Klebsiella pneumoniae ESBL and non-ESBL.

-

•

Increasing the dose of antibiotics inhibits the growth of Klebsiella pneumoniae.

-

•

Ciprofloxacin is more effective than cotrimoxazole and doxycycline in Klebsiella pneumoniae.

1. Introduction

Klebsiella pneumoniae (K. pneumoniae) is a Gram-negative bacterium that can cause bacteremia, sepsis, urinary tract infections, pneumonia, and nosocomial infections [1]. A study conducted in hospitals in 10 Asian countries from 2008 to 2009 found K. pneumoniae as the most common cause of nosocomial infections, namely pneumonia associated with ventilator installation [2]. Antibiotics resistance has become a significant problem worldwide. In the era of increasing antibiotic resistance and the lack of discovery of new antibiotics, it is necessary to optimize the use of existing antibiotics to treat infections [3]. Antibiotic resistance of Klebsiella spp. is highest in Asia (≥60%), reflecting an alarming increase in opposition to this bacterium. Increased resistance, especially to various classes of antibiotics classified by WHO as essential drugs, so the used of new and more broad-spectrum antibiotics must be limited if there are still narrower-spectrum and effective antibiotics [4].

The prevalence of K. pneumoniae infection was 13% in America, 5% in Pakistan, 64.2% in Nigeria, 33.9% in India, 17.4% in Denmark, and 14.1% in Singapore. K. pneumoniae Extended-Spectrum Beta-Lactamase (ESBL) infection in Indonesia was 35.35%, a total of 297 isolates from patients hospitalized from January–April 2005 and 38.5% of all isolates from October 2014–May 2015 at Surabaya [5,6]. In a study conducted in Turkey in 2016, there were 190 patients with nosocomial bacteremia caused by K. pneumoniae with a mortality rate of 47.9% [7]. Another study in Taiwan in 2020 involving 150 patients with bacteremia caused by K. pneumoniae had a mortality rate of 20–40% [8].

Ciprofloxacin, cotrimoxazole, and doxycycline are antibiotics used for a long time and are included in WHO essential drugs because of their excellent efficacy, minimal side effects, and relatively inexpensive. There are also injection and oral dosage forms with good bioavailability making them easier to use and relatively easy to obtain. The 2021 hospital antimicrobial stewardship guidelines from the Ministry of Health also classify these antibiotics in the access group [9,10]. These antibiotics are still effective enough to treat various Gram-negative infections based on available data, including K. pneumoniae. The study in France with 40 samples of K. pneumoniae, 75% susceptible to ciprofloxacin, also analyzed the time-kill curve of ciprofloxacin against K. pneumoniae [11]. A study in China demonstrated the use of cotrimoxazole for K. pneumoniae in vitro. Of 812 isolates of K. pneumoniae, 175 (21.6%) isolates were resistant to cotrimoxazole [12]. A study in Mumbai, India, with a retrospective method involving 2951 samples collected from January 2017–December 2018 with 263 of these samples were isolates of K. pneumoniae from sputum, showed doxycycline susceptibility of 68.4% [13]. Clinical infectious disease stated that based on pharmacokinetic and MIC data for UTIs caused by Enterobacter ESBL, doxycycline could potentially be used for therapy [14].

Time kill curve can be used to study antimicrobial activity that depends on concentration and time-dependent, so this method serves as an alternative option that provides more detailed and dynamic information than MIC. Considering the sensitive profile data to ciprofloxacin, cotrimoxazole, and doxycycline antibiotics, this study aimed to compare the effectiveness of these antibiotics in vitro against K. pneumoniae and K. pneumoniae ESBL isolates at a hospital in the form of an analysis of the bacterial time-kill curve.

2. Method

The study used a case-control (experimental) analysis with a posttest control group design. The subjects used were K. pneumoniae ESBL and non-ESBL, replicated 6 times. Antibiotics used included ciprofloxacin, cotrimoxazole, and doxycycline. This study was conducted from June 2021 to May 2022. The antibiotic doses used in K. pneumoniae varied, including ciprofloxacin 0.25, 0.5, 1 p/mL, cotrimoxazole 2, 4, and 8 p/mL, and 4, 8, and 16 p/mL. Furthermore, the time-kill was evaluated for each antibiotic exposure, including 0, 2, 4, 6, 8, and 24 h.

Before the examination, the number of colonies in the CFU/mL log was calculated first. If clinical isolates were found stored with the identification of fungi, sterile culture results, and clinical isolates of K. pneumoniae non-ESBL and K. pneumoniae ESBL were identified and tested for antibiotic susceptibility. Manually, the isolate could not be used. The measurement results were analyzed using statistical product and service solution (SPSS) software version 26.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). The analysis used were ANOVA, post-Hoc, Mann Whitney, and Kruskal Willis with p < 0.05.

3. Results

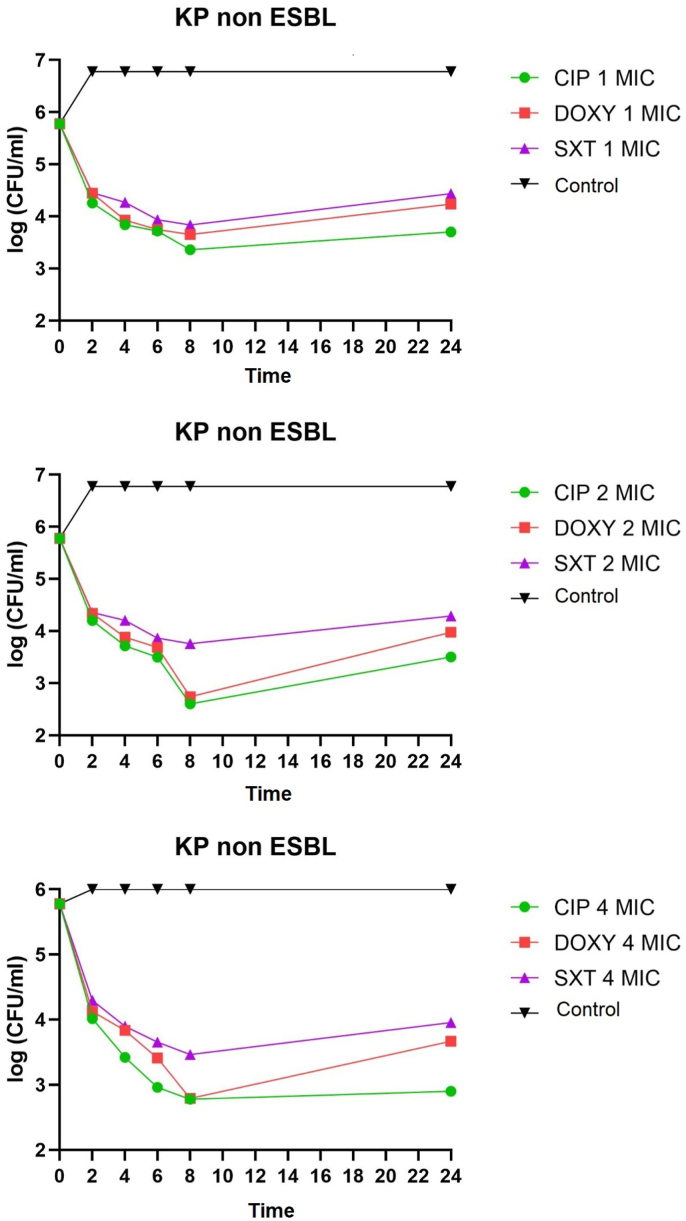

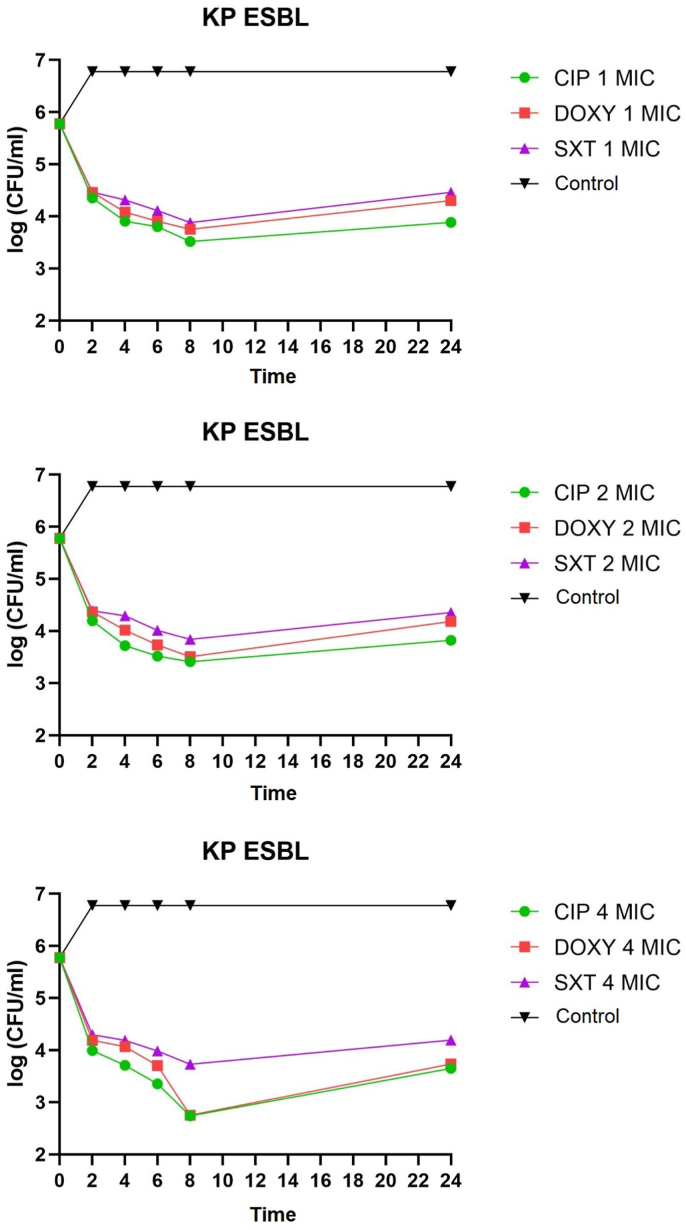

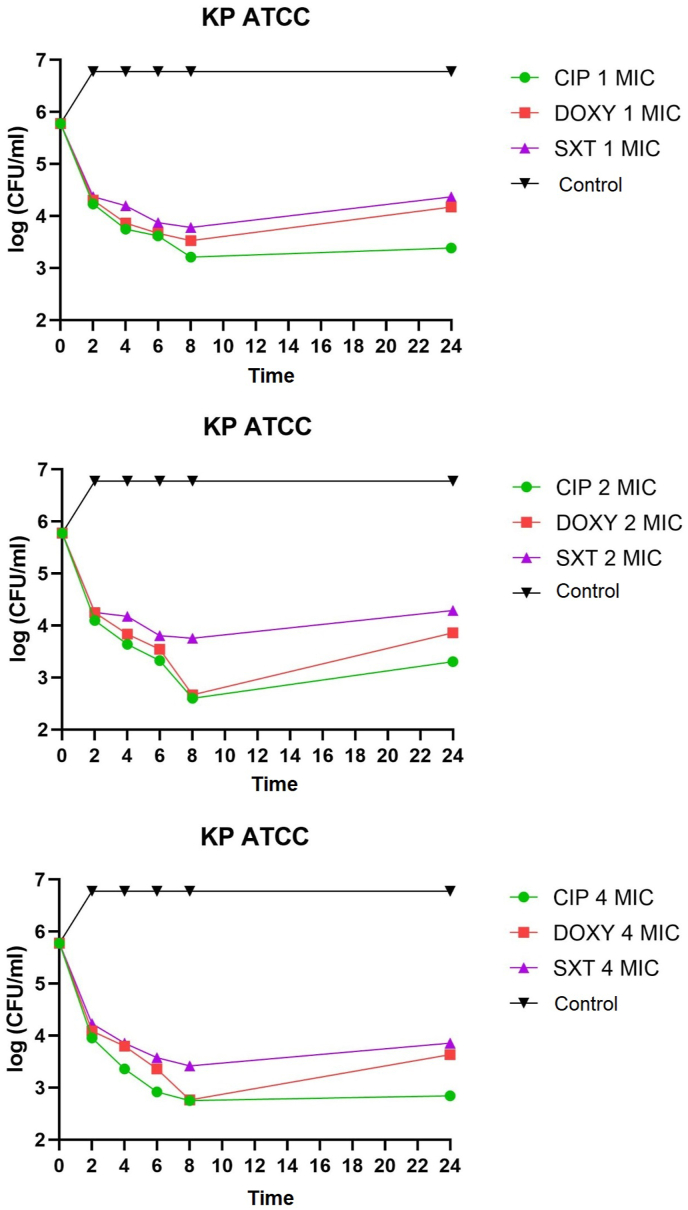

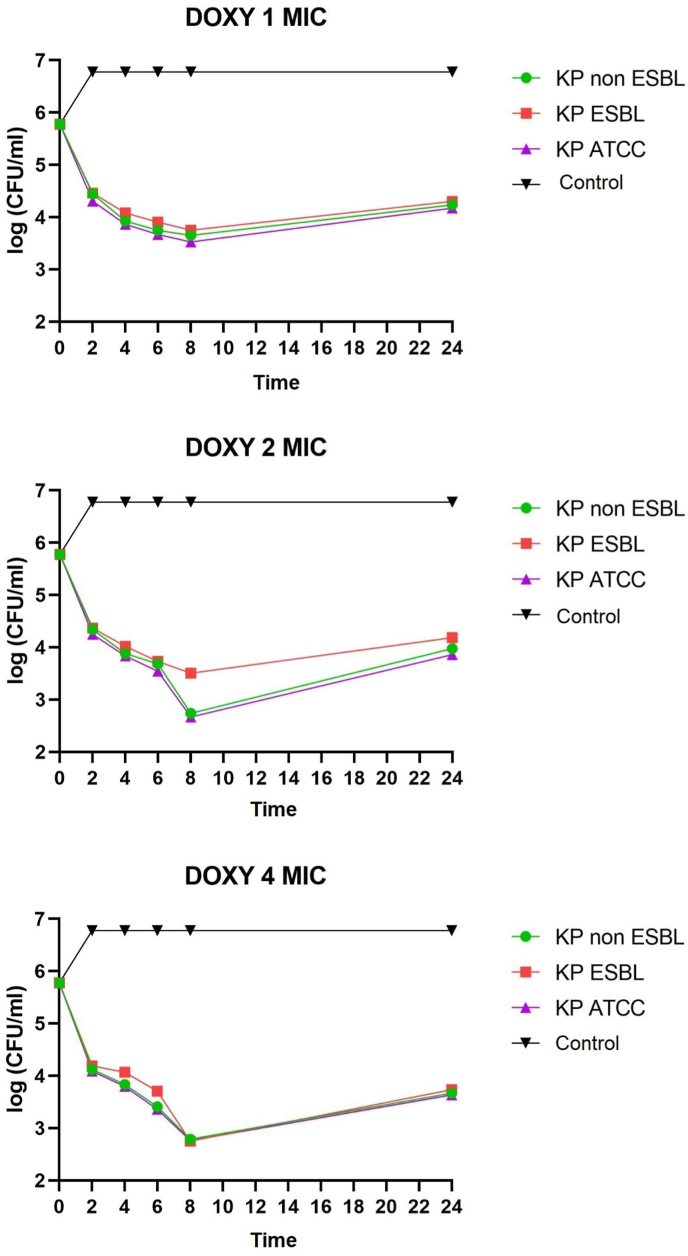

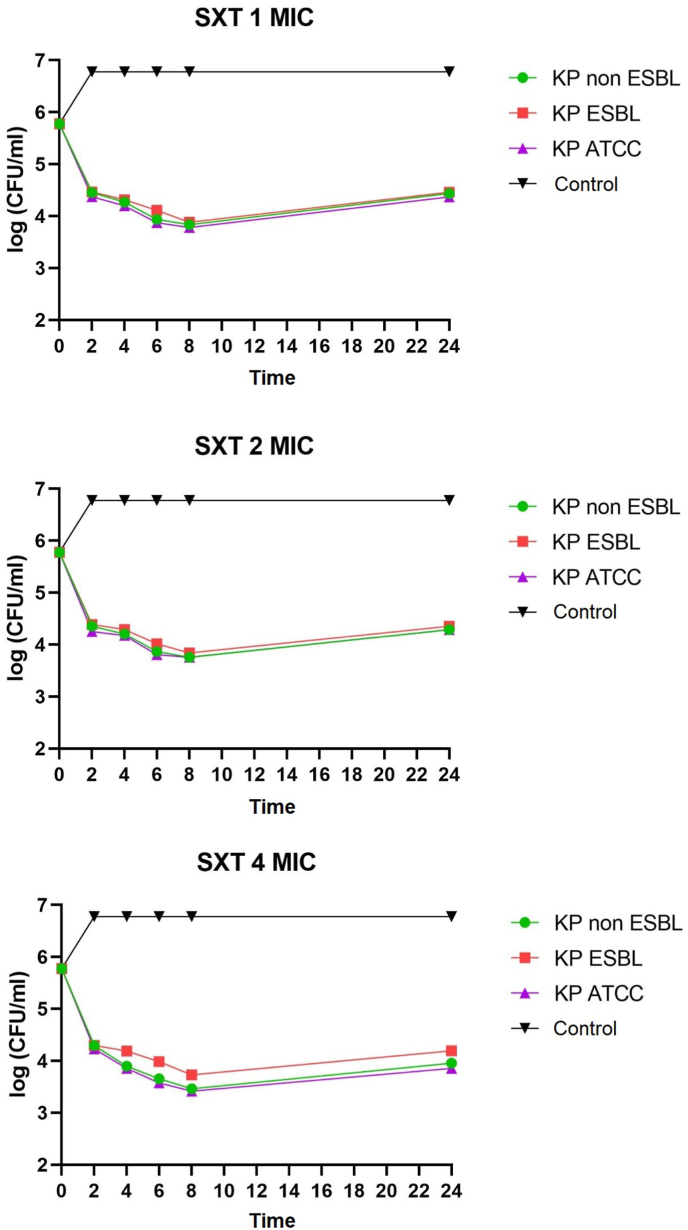

K. pneumoniae non-ESBL, K. pneumoniae ESBL, and K. pneumoniae ATCC on administering of ciprofloxacin, doxycycline, and cotrimoxazole 1 MIC at 2–8 h all showed bacteriostatic activity with a reduction in colony number of 1-2-log CFU/mL. K. pneumoniae non-ESBL, K. pneumoniae ATCC, administration of ciprofloxacin, doxycycline 2 MIC at 2–6 h showed bacteriostatic activity with a reduction in colony number of 1-2-log CFU/mL while at 8 h showed bactericidal activity with a reduction in the number of colonies by 3 log CFU/mL. Administration of cotrimoxazole 2 MIC at 2–8 h showed bacteriostatic activity with a reduction in the number of colonies by 1-2-log CFU/mL. K. pneumoniae ESBL on the administration of ciprofloxacin, doxycycline, and cotrimoxazole 2 MICs at 2–8 h showed bacteriostatic activity with a reduction in colony number of 1-2-log CFU/ml. The distribution of time-kill K. pneumoniae after antibiotic administration could be seen in Fig. 1, Fig. 2, Fig. 3, Fig. 4, Fig. 5, Fig. 6.

Fig. 1.

Time-kill graph of the number of non-ESBL K. pneumoniae colonies at 0, 2, 4, 6, 8, and 24 h against antibiotics ciprofloxacin, doxycycline, and cotrimoxazole at 1 MIC, 2 MIC, 4 MIC.

Fig. 2.

Time-kill graph of the number of K. pneumoniae ESBL colonies at 0, 2, 4, 6, 8, and 24 h against antibiotics ciprofloxacin, doxycycline, and cotrimoxazole at 1 MIC, 2 MIC, 4 MIC.

Fig. 3.

Time-kill graph of the number of K. pneumoniae ATCC colonies at 0, 2, 4, 6, 8, and 24 h against the antibiotic's ciprofloxacin, doxycycline, and cotrimoxazole at 1 MIC, 2 MIC, 4 MIC.

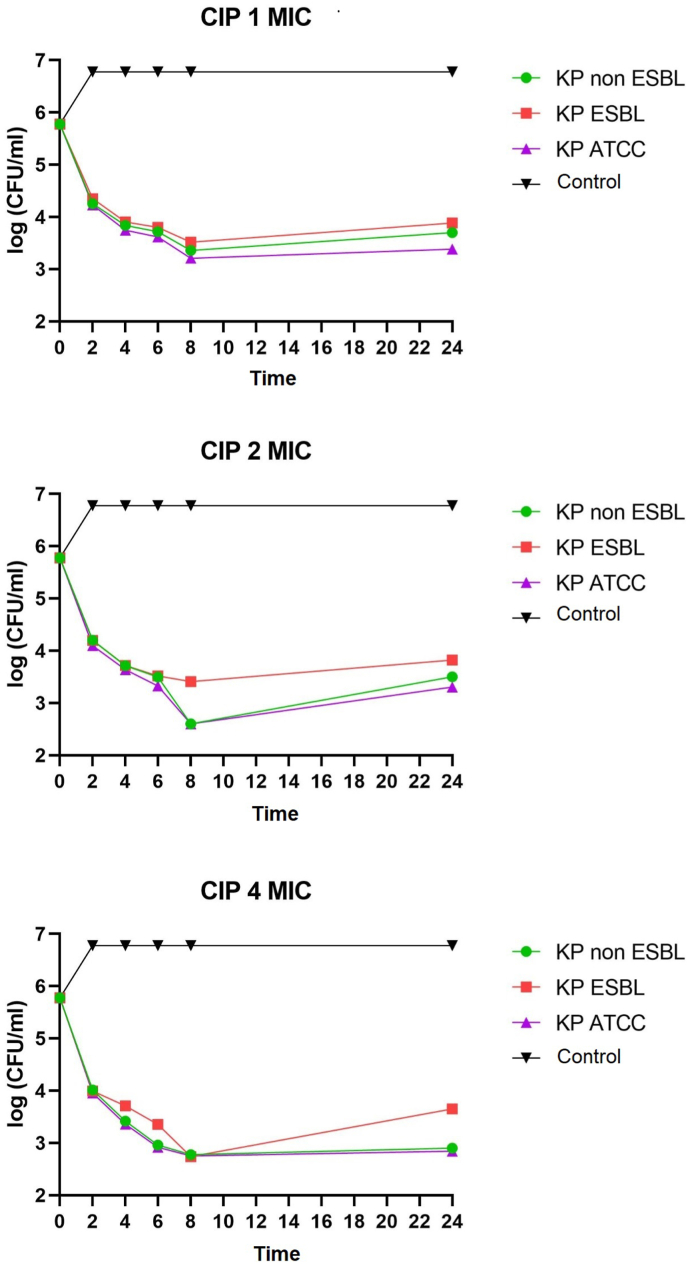

Fig. 4.

Time-kill graph of the number of colonies of K. pneumoniae non-ESBL, K. pneumoniae ESBL, and K. pneumoniae ATCC at 0, 2, 4, 6, 8, and 24 h against the administration of the antibiotic ciprofloxacin at concentrations of 1 MIC, 2 MIC, 4 MIC.

Fig. 5.

Time-kill graph of the number of colonies of K. pneumoniae non-ESBL, K. pneumoniae ESBL, and K. pneumoniae ATCC at 0, 2, 4, 6, 8, and 24 h against doxycycline antibiotics at concentrations of 1 MIC, 2 MIC, 4 MIC.

Fig. 6.

Time-kill graph of the number of colonies of K. pneumoniae non-ESBL, K. pneumoniae ESBL, and K. pneumoniae ATCC at 0, 2, 4, 6, 8, and 24 h against cotrimoxazole antibiotics at concentrations of 1 MIC, 2 MIC, 4 MIC.

K. pneumoniae non-ESBL, K. pneumoniae ATCC on the administration of ciprofloxacin 4 MIC at 2–4 h showed bacteriostatic activity with a reduction in colony number of 1-2-log CFU/mL while at 6–8 h showed activity bactericidal with a reduction in the number of colonies by 3-log CFU/mL. In K. pneumoniae ESBL on the administration of ciprofloxacin 4 MIC at 2–6 h showed bacteriostatic activity with a reduction in the number of colonies by 1-2-log CFU/mL, while at 8 h showed bactericidal activity with a reduction in colony number by 3-log CFU/mL. K. pneumoniae non-ESBL, K. pneumoniae ESBL, and K. pneumoniae ATCC on the administration of doxycycline 4 MIC at 2–6 h showed bacteriostatic activity with a reduction in the number of colonies by 1-2-log CFU/mL while at 8 h showed activity bactericidal with a reduction in the number of colonies by 3 log CFU/mL. Administration of cotrimoxazole 4 MIC at 2–8 h showed bacteriostatic activity with a reduction in the number of colonies by 1-2-log CFU/mL. K. pneumoniae non-ESBL, K. pneumoniae ESBL, K. pneumoniae ATCC, on the administration of ciprofloxacin, doxycycline, cotrimoxazole 1 MIC, 2 MIC, 4 MIC showed that all colonies began to grow back at 24 h. Results of the analysis of the effectiveness of time-kill K. pneumoniae could be seen in Table 1, Table 2.

Table 1.

Analysis of differences in the effectiveness of antibiotics used in K. pneumoniae.

| Time to Kill | Antibiotic | CI 95% | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | Ciprofloxacin | Doxycycline | 0.023–0.258 | 0.020 |

| Doxycycline | Cotrimoxazole | −0.161 – 0.074 | 0.453 | |

| Cotrimoxazole | Ciprofloxacin | 0.067–0.302 | 0.003a | |

| 4 | Ciprofloxacin | Doxycycline | 0.089–0.407 | 0.004a |

| Doxycycline | Cotrimoxazole | 0.038–0.356 | 0.017 | |

| Cotrimoxazole | Ciprofloxacin | 0.286–0.603 | <0.001a | |

| 6 | Ciprofloxacin | Doxycycline | −0.004 – 0.451 | 0.054 |

| Doxycycline | Cotrimoxazole | −0.027 – 0.427 | 0.082 | |

| Cotrimoxazole | Ciprofloxacin | 0.196–0.651 | 0.001a | |

| 8 | Ciprofloxacin | Doxycycline | – | 0.015 |

| Doxycycline | Cotrimoxazole | – | 0.015 | |

| Cotrimoxazole | Ciprofloxacin | – | 0.005a | |

| 24 | Ciprofloxacin | Doxycycline | 0.241–0.818 | 0.001a |

| Doxycycline | Cotrimoxazole | −0.075 – 0.502 | 0.140 | |

| Cotrimoxazole | Ciprofloxacin | 0.454–1.032 | <0.001a | |

Note.

Significant <0.01.

Table 2.

Analysis of differences in 1 MIC, 2 MIC, and 4 MIC in K. pneumoniae.

| Time to Kill | Antibiotic | CI 95% | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | 1 MIC | 2 MIC | −0.027 – 0.187 | 0.136 |

| 1 MIC | 4 MIC | 0.114–0.328 | <0.001a | |

| 2 MIC | 4 MIC | 0.034–0.248 | 0.012 | |

| 4 | 1 MIC | 2 MIC | −0.196 – 0.267 | 0.754 |

| 1 MIC | 4 MIC | −0.046 – 0.417 | 0.111 | |

| 2 MIC | 4 MIC | −0.081 – 0.381 | 0.193 | |

| 6 | 1 MIC | 2 MIC | −0.125 – 0.368 | 0.321 |

| 1 MIC | 4 MIC | −0.106 – 0.599 | 0.007a | |

| 2 MIC | 4 MIC | −0.015 – 0.478 | 0.065 | |

| 8 | 1 MIC | 2 MIC | – | 0.173 |

| 1 MIC | 4 MIC | – | 0.250 | |

| 2 MIC | 4 MIC | – | 0.965 | |

| 24 | 1 MIC | 2 MIC | −0.292 – 0.479 | 0.662 |

| 1 MIC | 4 MIC | −0.075 – 0.502 | 0.026 | |

| 2 MIC | 4 MIC | 0.454–1.032 | 0.073 | |

Note.

Significant <0.01.

4. Discussion

Various studies in antibiotics have been carried out clinically and in vitro to treat infections due to K. pneumoniae. This study tested and compared the oral antibiotics ciprofloxacin, cotrimoxazole, and doxycycline exposed to K. pneumoniae non-ESBL, K. pneumoniae ESBL, and K. pneumoniae ATCC at concentrations of 1 MIC, 2 MIC, and 4 MIC in vitro. Judging from the study's results, ciprofloxacin was faster reaching bacterial concentrations at higher concentrations (2 MICs at 8 and 4 MICs at 6 and 8) as it is concentration-dependent [15] while at 1 MIC concentration ciprofloxacin only comes bacteriostatic. There were time-kill studies exposing ciprofloxacin to several strains of K. pneumoniae with the result that some strains of K. pneumoniae at 1 MIC only reached bacteriostatic [11].

Ciprofloxacin also affected K. pneumoniae ESBL, and the bactericidal concentration was only reached at a concentration of 4 MICs at 8 h, while the 1 MIC and 2 MICs were only bacteriostatic. ESBLs resist beta-lactam antibiotics, including third-generation cephalosporines and below and aztreonam. Genes encoding ESBL production may be chromosomal or plasmid-mediated. Usually, plasmids carrying ESBL production genes also have genes encoding other antibiotic resistance, including gyrA encoding quinolone resistance. There was a study linking ESBL production and ciprofloxacin resistance in K. pneumoniae, showing no association between ESBL production and ciprofloxacin resistance [16].

This study also showed that doxycycline affected K. pneumoniae non-ESBL, K. pneumoniae ESBL, and K. pneumoniae ATCC. Theoretically, doxycycline tends to be time-dependent rather than concentration-dependent and bacteriostatic. At concentrations of 2–4 MIC, there was bacteria inhibition. At higher concentrations of 8–16 MIC, doxycycline is concentration-dependent to kill bacteria [17]. Pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic data on doxycycline are rarely obtained and updated. Doxycycline's advantages include its availability in oral form, broad antimicrobial activity, and mild side effects. Doxycycline has also successfully treated K. pneumoniae MDR infection in UTIs [18]. In this study, doxycycline reached bactericidal concentrations at 2 MICs and 4 MICs at 8 h in K. pneumoniae non-ESBL and K. pneumoniae ATCC.

In contrast, K. pneumoniae ESBL reached bactericidal concentration at 4 MICs at 8 h. A studies showed that the time-kill doxycycline exposed to Acinetobacter baumannii might also be bactericidal [19]. Time-kill study of doxycycline monotherapy against K. pneumoniae carbapenem producer showed potential antibacterial activity [20]. There were time-kill studies of the same drug class, namely tigecycline, which at specific concentrations could also be bactericidal against K. pneumoniae [21].

Cotrimoxazole also affected K. pneumoniae non-ESBL, K. pneumoniae ESBL, and K. pneumoniae ATCC, at concentrations of 1 MIC, 2 MIC, and 4 MIC in the second, fourth, sixth, and eighth hours, all achieved bacteriostatic effect. Cotrimoxazole tends to be bacteriostatic and can also be bactericidal. In gram-negative, it is concentration-dependent, although there are few supporting data. Cotrimoxazole is not affected by beta-lactamase because of its chemical structure. Neverheless, some studies suggest ESBL-producing organisms can also acquire resistance genes to cotrimoxazole which are often sul1 and sul2 [22]. Cotrimoxazole can be used in nosocomial infections caused by Enterobacter, which produces ESBL and is still susceptible. Even for UTIs, the results are as good as carbapenem therapy. Cotrimoxazole has the advantage that it is available in oral and injectable forms so that patients can go on an outpatient basis, and side effects are also relatively mild [23].

All colonies of K. pneumoniae non-ESBL, K. pneumoniae ESBL, and K. pneumoniae ATCC grew back at 24 h. This might be due to the decreased antibiotic concentration and could also be due to tolerance or persistence. Tolerance is one way for bacteria to survive antibiotics. The tolerant bacterial population has the same MIC as the susceptible population, but the passive population can stay at high antibiotic doses and is often much higher than its MIC. Tolerant bacterial population cannot grow or replicate under high antibiotic concentrations. The subpopulation of bacteria that tolerate is called the persisters. Persisters are naturally present in almost every bacterial population, including K. pneumoniae. This is an attempt by the bacterial population to survive and live in unfavorable environmental conditions. Drug concentrations usually exceed 8–10 times the MIC to prevent persistence [24,25].

Determining whether an antibiotic is bacteriostatic or bactericidal provides information about the action potential of the antibiotic in vitro. This information must be combined with pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic data to predict its efficacy in vivo [24].

The limitations of this study include the current time-kill studies, rarely using oral antibiotics, so further studies are needed with more varied types of antibiotics, more significant number of samples and observation times so that they can provide complete information for the treatment of K. pneumoniae infection.

5. Conclusion

Time-kill studies showed that ciprofloxacin and doxycycline achieved bactericidal activity, while ciprofloxacin appears more bactericidal than doxycycline, and cotrimoxazole completes the bacteriostatic activity. Therefore, these results show that ciprofloxacin inhibits the growth of K. pneumoniae non-ESBL and K. pneumoniae ESBL, K. pneumoniae ATCC 13883 better than cotrimoxazole and doxycycline. Ciprofloxacin, cotrimoxazole, and doxycycline inhibit the growth of K. pneumoniae non-ESBL, K. pneumoniae ESBL, and K. pneumoniae ATCC 13883. The most significant difference is between ciprofloxacin and cotrimoxazole, at 1 MIC and 4 MIC concentrations, in K. pneumoniae ESBL and K. pneumoniae ATCC 13883.

Ethical approval

We have conducted an ethical approval base on the Declaration of Helsinki with registration research at the Health Research Ethics Committee in Dr. Soetomo General Academic Hospital, Surabaya, Indonesia.

Sources of funding

None.

Author contribution

All authors contributed toward data analysis, drafting and revising the paper, gave final approval of the version to be published and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Registration of research studies

Name of the registry: Health Research Ethics Committee in Dr. Soetomo General Academic Hospital, Surabaya, Indonesia.

Unique Identifying number or registration ID: 0371/KEPK/II/2022.

Hyperlink to your specific registration (must be publicly accessible and will be checked): -

Guarantor

Agung Dwi Wahyu Widodo is the person in charge of the publication of our manuscript.

Consent

All participants are required to fill out an informed consent.

Declaration of competing interest

Andy Setiawan, Agung Dwi Wahyu Widodo, and Pepy Dwi Endraswarideclare that they have no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgement

We would like to thank our editor, “Fis Citra Ariyanto”.

References

- 1.Ashurst J.V., Dawson A. StatPearls Publishing LLC.; 2022. Klebsiella Pneumonia. StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing. Copyright © 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chung D.R., Song J.H., Kim S.H., Thamlikitkul V., Huang S.G., Wang H., et al. High prevalence of multidrug-resistant nonfermenters in hospital-acquired pneumonia in Asia. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2011;184(12):1409–1417. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201102-0349OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mędrzycka-Dąbrowska W., Lange S., Zorena K., Dąbrowski S., Ozga D., Tomaszek L. Carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae infections in ICU COVID-19 patients-A scoping review. J. Clin. Med. 2021;10(10) doi: 10.3390/jcm10102067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Llor C., Bjerrum L. Antimicrobial resistance: risk associated with antibiotic overuse and initiatives to reduce the problem. Therapeut. Adv. Drug Saf. 2014;5(6):229–241. doi: 10.1177/2042098614554919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Listiyawati I.T., Suyoso S., Rahmadewi R. Profile of fungal and bacterial infections in Inguinal Erythrosquamous Dermatoses. Berkala Ilmu Kesehatan Kulit dan Kelamin. 2017;29(3):204–211. doi: 10.20473/bikk.V29.3.2017.204-211. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Widjaja N.A., Hardiyani K., Hanindita M.H., Irwan R. Microbiological assessment of fresh expressed breast milk on room temperature at Dr. Soetomo hospital neonatal unit. Folia Medica Indonesiana. 2021;55(1):30–36. doi: 10.20473/fmi.v55i1.24346. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Durdu B., Hakyemez I.N., Bolukcu S., Okay G., Gultepe B., Aslan T. Mortality markers in nosocomial Klebsiella pneumoniae bloodstream infection. SpringerPlus. 2016;5(1):1892. doi: 10.1186/s40064-016-3580-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen C.L., Hou P.C., Wang Y.T., Lee H.Y., Zhou Y.L., Wu T.S., et al. The High mortality and antimicrobial resistance of Klebsiella pneumoniae bacteremia in northern Taiwan. J. Infect. Dev. Ctries. 2020;14(4):373–379. doi: 10.3855/jidc.11524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Puspitasari H.P., Faturrohmah A., Hermansyah A. Do Indonesian community pharmacy workers respond to antibiotics requests appropriately? Trop. Med. Int. Health : TM & IH. 2011;16(7):840–846. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2011.02782.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wasito E.B., Shigemura K., Osawa K., Farah A., Kanada A., Raharjo D., et al. Antibiotic susceptibilities and genetic characteristics of extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli isolates from stools of pediatric diarrhea patients in Surabaya, Indonesia. Jpn. J. Infect. Dis. 2017;70(4):378–382. doi: 10.7883/yoken.JJID.2016.234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grillon A., Schramm F., Kleinberg M., Jehl F. Comparative activity of ciprofloxacin, levofloxacin and moxifloxacin against Klebsiella pneumoniae, Pseudomonas aeruginosa and stenotrophomonas maltophilia assessed by minimum inhibitory concentrations and time-kill studies. PLoS One. 2016;11(6) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0156690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li J., Bi W., Dong G., Zhang Y., Wu Q., Dong T., et al. The new perspective of old antibiotic: in vitro antibacterial activity of TMP-SMZ against Klebsiella pneumoniae. J. Microbiol. Immunol. Infect. Wei Mian yu Gan Ran za Zhi. 2020;53(5):757–765. doi: 10.1016/j.jmii.2018.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Swaminathan S., Immanuel G., Arora S., Mehta S., Mittal R., Mane A., et al. Susceptibility pattern of doxycycline in comparison to azithromycin, cefuroxime and amoxicillin against common isolates: a retrospective study based on diagnostic laboratory data. J. Assoc. Phys. India. 2020;68(3):59–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jodlowski T., Ashby C.R., Nath S.G. Doxycycline for ESBL-E cystitis. Clin. Infect. Dis. : Off. Publ. Infect. Dis. Soc. Am. 2021;73(1):e274–e275. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa1898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wright D.H., Brown G.H., Peterson M.L., Rotschafer J.C. Application of fluoroquinolone pharmacodynamics. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2000;46(5):669–683. doi: 10.1093/jac/46.5.669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tolun V., Küçükbasmaci O., Törümküney-Akbulut D., Catal C., Anğ-Küçüker M., Anğ O. Relationship between ciprofloxacin resistance and extended-spectrum beta-lactamase production in Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae strains. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. : Off. Publ. Eur. Soc. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2004;10(1):72–75. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2004.00723.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cunha B.A., Domenico P., Cunha C.B. Pharmacodynamics of doxycycline. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2000;6(5):270–273. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-0691.2000.00058-2.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.White C.R., Jodlowski T.Z., Atkins D.T., Holland N.G. Successful doxycycline therapy in a patient with Escherichia coli and multidrug-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae urinary tract infection. J. Pharm. Pract. 2017;30(4):464–467. doi: 10.1177/0897190016642362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bantar C., Schell C., Posse G., Limansky A., Ballerini V., Mobilia L. Comparative time-kill study of doxycycline, tigecycline, sulbactam, and imipenem against several clones of Acinetobacter baumannii. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2008;61(3):309–314. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2008.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tang H.J., Lai C.C., Chen C.C., Zhang C.C., Weng T.C., Chiu Y.H., et al. Colistin-sparing regimens against Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemase-producing K. pneumoniae isolates: combination of tigecycline or doxycycline and gentamicin or amikacin. J. Microbiol. Immunol. Infect. Wei Mian yu Gan Ran za Zhi. 2019;52(2):273–281. doi: 10.1016/j.jmii.2016.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Petersen P.J., Jones C.H., Bradford P.A. In vitro antibacterial activities of tigecycline and comparative agents by time-kill kinetic studies in fresh Mueller-Hinton broth. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2007;59(3):347–349. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2007.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brown G.R. Cotrimoxazole - optimal dosing in the critically ill. Ann. Intensive Care. 2014;4:13. doi: 10.1186/2110-5820-4-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shi H.J., Wee J.H., Eom J.S. Challenges to early discharge of patients with upper urinary tract infections by ESBL producers: TMP/SMX as a step-down therapy for shorter hospitalization and lower costs. Infect. Drug Resist. 2021;14:3589–3597. doi: 10.2147/IDR.S321888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Levison M.E., Levison J.H. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of antibacterial agents. Infect. Dis. Clin. 2009;23(4):791–815. doi: 10.1016/j.idc.2009.06.008. vii. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sulaiman J.E., Lam H. Evolution of bacterial tolerance under antibiotic treatment and its implications on the development of resistance. Front. Microbiol. 2021;12 doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2021.617412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]