Abstract

Amidst COVID-19, teacher education has shifted to online learning. Although much is known about digital inequity in routine times, little is known about it under constrained conditions, particularly among women of minority groups. The study's goal was to explore the online-learning challenges encountered by (minority) Bedouin female preservice teachers (n = 41) compared to those encountered by (majority) Jewish counterparts (n = 60). Data from reflections (N = 101), focus groups (2), and (68) interviews underwent qualitative-constructivist content analysis. Group comparisons revealed socioculturally-based differential learning pathways, leading to educational inequities. We discuss possible ways to ensure equitable online teacher education using the “digital divide” perspective.

Abbreviations: B-PST, Bedouin preservice teachers; J-PST, Jewish preservice teachers

Keywords: Online learning, COVID-19, Educational equity, Digital divide, Bedouins in higher education.

1. Introduction

In March 2020, The World Health Organization declared a global pandemic following the rapid spread of the coronavirus, which had led to thousands of deaths. Consequently, many countries worldwide declared a quarantine policy. This policy required implementing innovative approaches to adapt to its various implications (Frei-Landau, 2020), which included the closing of universities. An unprecedented situation emerged: suddenly the entire education system, including the higher-education system, was forced to shift to distance learning (OECD, 2020), using various online-learning platforms (Moorhouse, 2020). This meant that learners had to adapt to the changes, which raised an array of new challenges. Scholars began wondering how this unplanned shift to online learning might affect the learning practices and students' engagement in teacher education (Allen et al., 2020; Carrillo & Flores, 2020). One noticeable concern was that students from disadvantaged backgrounds might not have access to technology – an issue previously coined as the “digital divide” (van Deursen & van Dijk, 2019), which might result in educational inequities (UNESCO, 2020). In fact, given that learning was conducted within the domestic environment, one's experience of the COVID-19 shift to exclusive online learning was greatly affected by one's cultural background and origins. The lockdown conditions also prohibited learners from using external support (e.g., gaining access to technology from a university library). Thus, these changes underscored the need for culturally responsive and inclusive pedagogies in the service of social justice and inclusion (Guðjónsdóttir et al., 2008; Heemskerk et al., 2011; Hendin et al., 2016). However, little is known about the challenges and adjustments required for promoting educational equity in teacher education under these unique circumstances, particularly among minority groups, such as the female Bedouin preservice teachers in Israel. To fill this gap in the literature, the study's goal was to gain insight into the online-learning challenges, particularly as manifested among socioeconomically diverse learners; thus, we examined this issue among both Bedouin and Jewish female preservice teachers (B-PST, J-PST, respectively1 ). The findings of such a study would provide valuable input for teacher-education policy makers, as well as for teacher educators. To our knowledge, and according to recent literature reviews of online learning during the pandemic (Carrillo & Flores, 2020; Mseleku, 2020), the issue of digital inequity has received insufficient attention in the context of COVID-19 online learning, and particularly in the realm of teacher education. This study serves as a case study to understand the structural and cultural barriers to learning equity in the teacher-education arena in times of crisis, using the digital divide perspective.

2. Theoretical background

2.1. Online learning in teacher education

There is a wide array of concepts in teacher-education literature on online learning that encompass different meanings, but they are often used interchangeably (e.g., e-learning, Information and Communication Technology (ICT), distance education, online teaching, remote teaching, etc.). Online-learning environments enable teachers to teach and interact with their students using various learning possibilities in a remote scenario (Carrillo & Flores, 2020). Online-learning platforms and ICT have become critical components in teacher education, as they allow for innovation and contribute to the learning process (Avidov-Ungar et al., 2020; Tezci, 2011). Specifically, the flexibility of online tools helps teachers keep content up-to-date and address students' individual learning needs (Heemskerk et al., 2011) – two aspects that became imperative in teacher education during the pandemic. In fact, long before the COVID-19 pandemic, online-learning environments were increasingly used in preservice teacher education (Martinovic & Zhang, 2012), and scholars had explored its processes and challenges (Kleinsasser & Hong, 2016) as well as the effective ways to integrate technology in teacher education (Dorner & Kumar, 2016) and in classrooms (Admiraal et al., 2017; Alt, 2018). However, the COVID-19 pandemic highlighted the particular need to employ online learning, in general, and in teacher education, in particular, in times of crisis. It was argued (Dhawan, 2020) that, generally, in the aftermath of various natural disasters, such as floods, earthquakes, hurricanes, or during armed conflicts (war, terrorism), knowledge delivery often becomes challenging as schools and higher-education systems are closed and educational processes are disrupted. In Israel, for instance, apart from the pandemic lockdown, also the ongoing missiles attacks have led to the closing of schools and higher-education systems. Hence, studies regarding the affordances and barriers of online learning during crises have flourished, as it is relevant not only to the COVID-19 era but also to future crisis situations. Thus, a literature review of 134 empirical studies conducted in 31 countries, on the use of online learning in teacher education during the pandemic revealed that the most researched topics were the effectiveness of the teaching-learning process, the role of online communities, teacher engagement, teacher knowledge, and the use of video and peer assessment activities (Carrillo & Flores, 2020). Another review (Mseleku, 2020) showed that the major challenges associated with the sudden shift to online learning were faculty members' and students’ adjustment difficulties; mental health-related issues; connectivity; an unconducive environment; and the lack of teaching and learning resources.

Despite the abundance of studies on online learning during the pandemic, it appears that the issue of learning equity among gender-based minority groups received little attention. In fact, only a handful of studies examined female students' experiences of online distance learning (Dewi & Muhid, 2021; Shahzad et al., 2021); moreover, their focus was on the participants’ attitudes, rather than on challenges. A study published in The Lancet indicated that female academics were disproportionately affected by the COVID-19, which in turn lessened their scientific productivity. This was explained in terms of the increased burden of familial responsibility that women had to contend with during the pandemic (Gabster et al., 2020). In addition, a few studies explored minority group students' perceptions of online learning, focusing on groups such as African American minority students (Beschorner, 2021), or students of linguistic minority (Choi & Chiu, 2021). Investigating minority groups' coping with online learning during a crisis is of great importance given the digital divide discourse. A recent descriptive literature review (Dhawan, 2020) that analyzed the potential strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and challenges of online learning during the COVID-19 pandemic as well as during natural disasters, underscored the need to address the challenge of unequal distribution of ICT infrastructure, also initially referred to as “the digital divide.”

2.2. The digital divide, minority groups, and online distance education

It has been argued that online-learning technology promotes social justice and cultural inclusion, as it extends access to education by addressing barriers of time and place, thus enabling students of varied and distant populations to attend education (Austin, 2006; Sims et al., 2008). For instance, Carr (2000) demonstrated that distance learning helps minority Native American students acquire education while remaining within their tribal communities and adhering to their cultural values. However, others have contended that the premise, according to which technology promotes social inclusion, is misleading, given the digital divide, which is especially conspicuous in the case of the Muslim minority in India (Carr, 2000; Khan & Ghadially, 2010).

The concept of the digital divide initially referred to the gap between those who have access to the Internet, and those who do not (titled as the first-level digital divide), a gap which subsequently prevents minority groups from reaping the benefits of online education (Norris, 2001). However, with increased distribution of Internet infrastructure, the differences in physical access to technology have dimin-ished, thus allegedly “solving” the digital divide problem. Yet it was argued that inequalities in material access are still evident (van Deursen & van Dijk, 2019); furthermore, the remain significant gaps between populations in terms of Internet skills and usage was highlighted and is referred to as the second-level digital divide (DiMaggio et al., 2004; Van Deursen & van Dijk, 2014). In the last decade, the attention has shifted to the gap created by the outcomes of Internet use and its tangible benefits, which is referred to as the third-level digital divide (Van Deursen & Helsper, 2015; Van Deursen & van Dijk, 2019).

The research literature indicates that gender, sociocultural status, and region are crucial elements when it comes to the various levels of the digital divide. For instance, it was found that learners in rural areas have less Internet access (Graham et al., 2012); socioeconomic status significantly impacts the nature of Internet use (van Dijk, 2005; Zillien & Hargittai, 2009); gender is a salient predictor of differences in Internet usage, with female students demonstrating less efficient use than do their male counterparts (Saha & Zaman, 2017); and, finally, it was found that generally, males and majorities are most likely to benefit from material access (Van Deursen & van Dijk 2019). Ultimately, it appears that students of minority groups are more likely to be deprived of the benefits of effective online education. This is particularly relevant in times of crisis, when learning is conducted exclusively online, such as during the COVID-19 pandemic, as it effectively magnifies the digital divide (Saha et al., 2021). That is, as the lockdown has forced learners back into their homes, there is an increasing interest in the potentially negative impact that factors such as learners' origins, cultural background, domestic roles, values, and limited resources have on effective learning.

Research about the digital divide affecting Muslim preservice students' teacher education worldwide, and especially female Muslim preservice students, is limited (Saha et al., 2021). Specifically, the digital divide challenges encountered by minority groups using online learning during a crisis and other natural disasters have received little-to-no academic attention. To address this paucity, this study explores this issue among the unique population of Israeli female Bedouin preservice teachers.

2.3. Bedouin women in Israel

The Bedouin community of the Negev is one of the ethnic groups that constitute Israel's multicultural society. This group has some unique characteristics, alongside similarities, with other Bedouin-Arab communities in the Middle East (Manor-Binyamini, 2011). The nomenclature Bedouin-Arab refers to all the nomadic tribes of North Africa and the Middle East. Israel's Bedouin Arabs are Arab by nationality and Muslim by religion; yet their tribes differ from other Arab Muslims, in that they lead a nomadic lifestyle in the desert (Abu-Rabia-Queder, 2007). Estimations are that approximately 270,000 Bedouins reside in the Negev region of Israel (Central Bureau of Statistics, 2018), which makes them a minority group in Israeli society.

Whereas about half of the Negev Bedouins live in recognized townships (referred to as “permanent settlements”), the other 50% live in scattered villages (in which the tribe members live in tents and periodically migrate to different parts of the desert). These remote villages that are dispersed throughout the desert are not officially recognized by the government as settlements (hence they are referred to as the “the unrecognized–dispersed villages”). As such, they have no access to basic municipal services, which means no electricity, telephone lines, paved roads, adequate public transportation, or sufficient educational services (Manor-Binyamini & Abu-Ajaj, 2017). Moreover, among the minorities in Israel, the Bedouins have the lowest education level, below-average income per family, and the highest unemployment rates (Abu-Saad et al., 2017). The Bedouin community's culture and family structure are remarkably different from those of Western society. The Bedouin community is a tribal, traditional, and patriarchal society, which is characterized by a high prevalence of marriage between relatives, high fertility rates, and polygamy estimated at the rate of 20% of all marriages (Alhazail & Atawna, 2005). The “hamula,” (i.e., the extended family), consists of several related nuclear families, a structure that ensures that all family members obey the collective norms and demonstrate unconditional loyalty to the tribe. These collective codes play an essential role in female marginalization. For instance, Bedouin women are driven to marriage for the sake of the collective rather than to fulfill a personal desire. Through marriage, specifically, by having many children, and especially boys, women are expected to increase the power and size of the extended family and thus of the tribe as a whole (Abu-Rabia-Queder, 2007).

Generally, Bedouin women's status depends significantly on religious traditions and social customs (Alhazail & Atawna, 2005), according to which the man is considered the family's dominant figure, whereas the woman's responsibilities are focused first and foremost on caring for the family (Manor-Binyamini & Abu-Ajaj, 2017). Hence, Bedouin women do not play a role in the public sphere. Furthermore, their social relationships are confined to the family sphere, mainly to protect the family's honor and reputation. Consequently, women's mobility outside of the tribe is generally restricted; thus, hindering their involvement in activities outside the domestic arena (Manor-Binyamini & Shoshana, 2018).

As regards women's education, Al-Krenawi (2004), a southern Bedouin researcher, states that “Social and cultural factors have delayed the development of an appropriate educational system in the Bedouin communities in the Negev …“, and that “Bedouins view the educational system as a threat to their traditions, and an attempt to sabotage their tribal ideology through modern concepts. Schools are acceptable only as long as they do not affect the social order and social values” (p. 10 in Kass & Miller, 2011). Hence, it was not until the late 1970s that high schools were built in the recognized townships, whereas education in the unrecognized villages suffered from unequal budgets and impoverished facilities (Abu-Saad, 2016). In addition, the Bedouin education system suffers from the highest dropout rates, mainly among young women in transition to high school, as attending school would require these young women to travel beyond their living area. The distances involved, as well as the issue of unchaperoned traveling, are prohibitive (Vaissblay & Vininger, 2020).

3. Bedouin women in higher education

In the last two decades, Bedouin women have begun pursuing a higher education, motivated by their aspiration to become agents of social change (Kass & Miller, 2011). This entailed attending colleges and universities situated outside the Bedouin towns, an activity that challenged the community's social norms (Abu-Rabia-Queder & Karplus, 2013). This development gave rise to fruitful academic research regarding the role of higher education in women's empowerment (Pessate-Schubert, 2003), its impact on Bedouin women's identity (Abu-Rabia-Queder, 2011; Abu-Rabia-Queder & Weiner-Levy, 2008), the religious worldviews and gender roles of Bedouin women (Abu-Rabia-Queder, 2007), and their social mobility (Pessate-Schubert, 2004; Schatz-Oppenheimer, 2016).

Along with the interest in the opportunities that higher education affords Bedouin women, scholars have also explored the obstacles faced by female Bedouin students. These include financial constraints, lack of public transportation and infrastructure, and difficulties adjusting both academically and socially (Abu-Saad, Horowitz & Abu-Saad, 2017). These findings called for policy changes, to improve Bedouin women's access to and perseverance in higher-education programs (Abu-Saad, 2016).

Despite the attention to Bedouin women's academic opportunities and the potential obstacles on their path to higher learning, almost no attention has been devoted to their needs in the context of adapting to online learning in times of crisis, such as the COVID-19 pandemic. In light of the special characteristics of the Bedouin community, in general, and the unique status of Bedouin women, in particular, it is imperative to explore their online-learning challenges in light of the digital divide perspective, by means of an intercultural qualitative comparison.

4. Research questions

-

1.

How do Bedouin and Jewish female preservice teachers describe the learning challenges related to the exclusive use of online learning?

-

2.

Focusing on the digital divide, in what ways do the challenges experienced by Bedouin female preservice teachers differ from those experienced by their Jewish counterparts?

5. Methods

5.1. The research context and design

Our research approach relied on the phenomenological perspective, which is based on the grounded theory principles (Corbin & Strauss, 2008). That is, as we aimed to gain insight into and conceptualize the online-learning challenges experienced by both Bedouin and Jewish female preservice teachers during the COVID-19 sudden shift to exclusive online education. This approach is best suited for developing a theory based on the participants’ reported experiences of a selected phenomenon (Holstein, 1994; Schwandt, 1994), as opposed to relying on a predefined theory. The underlying assumption is that the knowledge we seek can be found in the meanings that people attribute to their experiences (van Manen, 2016). Accordingly, the goal of the current study was to “capture” participants' perceived personal experiences of their online-learning challenges. Given the emergent quality of the study topic, this type of research approach allows for a profound understanding of the ways in which online-learning challenges are experienced, thus allowing for a comparative analysis to determine whether these are perceived differently by Bedouin and Jewish preservice teachers.

5.2. Participants

After obtaining permission from the Ethics Committee of the Achva academic college for teacher education, an appeal for volunteer participants was issued through the online-learning platform (MOODLE) and 101 (41 Bedouin and 60 Jewish) female preservice teachers responded and gave their informed consent. Specifically, we approached only first-year students, to ensure that the participants had no prior online-learning experience in a higher-education context (yet, it should be noted that they had experienced one semester of traditional learning, before the outbreak of the coronavirus pandemic). Furthermore, we approached only preservice teachers specializing in a single track, to minimize any potential bias related to the specific courses in each track. Hence, all participants were first-year students specializing in the same area, yet their different cultural backgrounds enabled an examination and comparison of the online-learning challenges experienced by Bedouin and Jewish students. (When discussing these cultural groups, the Bedouin preservice teachers are referred to from hereon as B-PSTs, and their Jewish counterparts are referred to as J-PSTs). Participants’ characteristics are displayed in Table 1 . As shown in Table 1, B-PSTs were generally younger than J-PSTs, yet the percentage of married students in this group was double that of the J-PST group (37% vs. 15%, respectively). B-PSTs also had a greater number of children; specifically, triple that of their counterparts (37% vs. 12%, respectively).

Table 1.

Participants' characteristics.

| Background Variables | Bedouin Preservice Teachers | Jewish Preservice Teachers | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | N = 41 | N = 60 | |

| Age (%) | 19–21 | 53 | 14 |

| Gender | 22–25 | 37 | 64 |

| 26–30 | 5 | 14 | |

| 31–35 | 5 | 5 | |

| 36 and up | 0 | 2 | |

| Female | 100 | 100 | |

| Male | 0 | 0 | |

| Family Status (%) | Single | 63 | 83 |

| Married | 37 | 15 | |

| Divorced/widow | 0 | 2 | |

| Number of Children | 0 | 63 | 88 |

| Learning Status | 1 | 21 | 2 |

| 2 | 0 | 5 | |

| 3 | 0 | 5 | |

| Above 3 | 16 | 0 | |

| First-year student | 100 | 100 |

5.3. Data collection

Data collection was conducted intensively over a six-week period in April and May of 2020, using multiple data sources. This was intended to allow for the triangulation of findings and to provide a comprehensive understanding of the issue (Bogdan & Biklen, 2007). As elaborated in Table 2 , data collection included written reflections (N = 101), focus groups (2), and semistructured interviews (68). The latter were conducted after analyzing the data collected via reflections and focus groups, to further hone our understanding of the issues. Interviews were relatively short (20–30 min); thus, we estimated that to achieve saturation, i.e., the point when new data obtained no longer provides additional insights (Strauss & Corbin, 2008), we would need to conduct interviews with a minimum of 30 students from each group. Eventually, 32 interviews were held with B-PSTs and 36 with J-PSTs. Selection criteria throughout the data collection were being a first-year student enrolled in the selected specialization track (to minimize bias).

Table 2.

The data collection and analysis.

| Data Type | Number & Classification | Description | A Sample Question | Recruitment & Analytical Process | Coding System of Materials |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Participants' written reflections | N = 101: 41 B-PSTs and 60 J-PSTs | Participants were asked to report, freely, in writing, the challenges they experienced as a result of the shift to exclusive online learning. They were encouraged to describe meaningful challenges, as well as lessons learned, and to express their feelings and thoughts. | “Please share your experience regarding the shift to online learning, including your challenges (if any). You may share whatever is relevant in your opinion. Please elaborate about your feelings, thoughts, conclusions, etc." | Invitations to participate were sent via the MOODLE platform (alongside the invitation to participate in a focus group), participation was voluntary. Written data were analyzed via content analysis. | Participants' written reflections were coded sequentially and separately for B-PST and J-PST (REF1—REF41; REF42-REF101, respectively) |

| Focus groups | Two focus groups: one with only B-PSTs (n = 8) and one with only J-PSTs (n = 12) | Participants were requested to discuss their challenges and needs when engaging in online learning. | “Please discuss your needs as learners when engaging in online learning” (A joint discussion was held with each group; students responded to each other's comments) | Invitations to participate were sent via the MOODLE platform. The focus groups were conducted online via ZOOM and lasted approximately 50 min. They were audiotaped, transcribed and analyzed via content analysis. | Data from the B-PST focus group were coded as “FG-B"; information obtained from the J-PST focus group was coded “FG-J". |

| Semi-structured interviews | N = 68: 32 with B-PSTs and 36 with J-PSTs. | The focus of the interviews was on the participants' experiences while engaging in online learning, with an emphasis on the challenges they encountered and on their perceptions of what would help make the learning experience more effective. | “In your opinion, what would make online learning more effective?" | After analyzing the data collected via reflections and focus groups, participants who noted in previous stages that they would be willing to partake in an interview were approached. Interviews were conducted via ZOOM and lasted approximately 20–30 min. With the interviewees' permission, the interviews were recorded, then transcribed and analyzed via content analysis. | Interviews were coded sequentially and separately for B-PST and J-PST (INW1-INW32; INW33-INW68, respectively). |

∗ B-PSTs = Bedouin preservice teachers; J-PSTs = Jewish preservice teachers.

5.4. Data analysis

Prior to data analysis, all data were coded, as elaborated in Table 2. Then, the data obtained from the reflections, focus groups, and interviews were analyzed using the thematic qualitative-constructivist content analysis method, which is based on grounded theory (Shkedi 2011). This approach enables the understanding of a phenomenon (i.e., the online-learning challenges) grounded in the data collected from those experiencing it. The analysis stages were as follows: first, we conducted a primary analysis (categorization), in which all data (transcripts and reflections) were scanned for recurring themes. These were identified as the topical units of meaning. In the second stage, a mapping analysis was conducted, in which we associated units of meaning with the various topical categories, and described the connections between these categories. Then, simultaneously with a general literature review, in the third stage, a more focused analysis was conducted, during which we selected the categories that were more pertinent to this study's goals and presented their findings. Eventually, in the final stage, a narrative was produced, presenting the results in a coherent form and in line with the existing literature.

Ultimately, to enable a comparative overview of B-PST versus J-PST perceived challenges, we calculated the frequency with which each theme and subtheme was mentioned by each group. To avoid duplications, if a theme was mentioned by the same participant in more than one of the data collection methods, the frequency was marked as greater than 1 only if additional information was provided in one of these instances. Table 3 demonstrates the qualitative content analysis coding process, conducted to understand the online-learning challenges, through the example of the theme –"culturally-based constraints."

Table 3.

An example of the qualitative content analysis coding process: Exemplifying the second theme –"culturally-based constraints".

| Category | Theme | Coding Method | Codes | Unit of analysis |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Preliminary phase – learning conditions | Culturally- based constraints | Expressions that reveal a conflict between online learning demands and the culturally expected social roles, that ultimately hinder participant's availability to begin engaging in learning | Counteraction with culturally accepted social role as mothers | - “As a homemaker, I want to successfully manage all of my responsibilities toward the children and my husband …, while continuing to perform well in my studies. It's very difficult … For example, if a child starts crying during an online class, I don't know what to do first: Should I focus on the lesson or attend to the crying child. ….… I feel like Wonder Woman: I get up in the morning clean the house, do the chores, prepare breakfast for the children, and then sit down to study; then dinner … The children don't understand that I have to focus, and study and they complain: “Why are you on the phone all the time?” (She sighs) (INTW-15) |

| - “I'll be ready to attend an online class but [just then] a child needs help with homework. I'm his mother. Who will help him if not me? So, eventually I don't enter the lesson.” (FG-B) | ||||

| -" There are so many assignments to hand-in and lessons to enter, in addition to everything I have to do in the house with my little baby, that I can't even begin with it” (REF-88) | ||||

| Counteraction with culturally accepted social role as wives | -"We are newly married. There are so many lessons and chores. When am I meant to spend some time with my husband? He deserves a wife.” (FG-B) | |||

| -"I have to be honest; I am not really in full swing with this learning method. I am rarely able to attend an entire lesson. I have to prioritize my family. I have a husband and children.” (REF-17) | ||||

| Counteraction with culturally accepted social role as daughters or sisters in the extended family | - “As the eldest sister, with five younger brothers, I feel an immense pressure to first help my mother first, before I can attend the online class. This is difficult.” (REF-23) | |||

| - “I am at home and I have a younger brother who has Williams syndrome. He is at home because the schools are closed. My mother works, so I'm the one who takes care of my brother during the day. That's why I am less available for online studies because, as the older sister, I have an enormous responsibility. I must care for him, make sure he eats, and keep him occupied with various activities.” (INTW-55) |

Trustworthiness was achieved first and foremost by triangulating the study's instruments. That is, we utilized three data-gathering instruments (interviews, reflections, and focus groups) while examining a single phenomenon (Lincoln & Guba, 1985; Nowell et al., 2017). Secondly, while conducting the analysis, we paid careful attention to ensure that no important ideas, themes, or constructs were overlooked, in addition to employing an investigator triangulation, by using two researchers while coding, analyzing, and interpreting the data (Korstjens & Moser, 2018). Specifically, data analysis was initially conducted by each of the researchers separately, followed by a joint brainstorming, in which the findings were discussed, and cases of disagreement were settled by further discussion until reaching an agreement. This method is frequently used in qualitative inquiry, particularly among diverse groups, to enhance trustworthiness (Frei-Landau et al., 2020c).

5.5. Findings

The findings are described in two subsections, wherein the first relates to the first research question and presents the online-learning challenges in accordance with the themes that emerged from the data analysis in general (without distinguishing between the B-PSTs and the J-PSTs). In the second subsection, findings related to the second research question are presented, focusing on the comparison between the two participant groups. This section concludes with an integrated summary of the findings, in the form of a diagram outlining the distinctions between the two culturally-based, online-learning pathways.

5.6. Participants’ experiences of online-learning Challenges–Research question 1

The first subsection engages with the question: How did female (both Bedouin and Jewish) preservice teachers describe the learning challenges they experienced as a result of the sudden shift to exclusive online learning?

In discussing their online-learning challenges, both B-PSTs and J-PSTs referred to two distinct phases: a preliminary phase, in which they were concerned with the effort to attain the conditions to enable online learning, and the ensuing phase, in which they referred to the process of adaptation and the resulting adjustments they made as learners, to make the online learning an effective learning experience (henceforth, we refer to these as preliminary and ensuing phases). Within these phases, findings revealed four main themes representing the online-learning challenges experienced by PSTs. The themes of (a) the apparatus for online learning and (b) culturally-based constraints were described as experienced in the preliminary phase, whereas the themes of (c) adjusting to online-learning features and (d) developing online-learning skills were described as corresponding to the ensuing phase. It should be noted that both B-PST and J-PST participants mentioned difficulties corresponding to both phases, yet the frequency of their mentions differed between the groups (as will be elaborated in the next section). The findings are presented in reference to this bipartite learning process: the preliminary phase, the ensuing phase, and the four themes emerging from them. Only pseudonyms are used in the excerpted quotes that follow.

5.7. Preliminary phase: the conditions for engaging in online learning

The preliminary phase that enables the pursuit of learning comprises two themes: having the necessary technical apparatus for online learning and the culturally-based constraints that may affect learners’ availability for learning.

-

(a)

Technical Apparatus for Online Learning

The first and most basic challenge that students described was related to the technical conditions without which learning cannot begin. Students mentioned the difficulty of attending lessons given the lack or the limited number of computers available in their homes. Some of them noted that they managed online learning using their cell phones, which made things difficult. Occasionally, having a single computer per family also created difficulties.

This type of study makes it very difficult for me. I don't have a PC of my own. I share one with my spouse who works from home. That's why I cannot always attend class. How can I even begin learning like this?! There are some courses I have never attended at all and I am trying to catch up, but certainly, that is not the same as being in class. (Dana, J-PST, INW-39)

As reported, a lack of technical conditions may impend learning as it cannot begin without these conditions. As Dana notes, there are some courses she has never attended. When a computer was not available at all, students reported conducting learning through their mobile devices. Yet, learning through the cell phone was described as extremely inconvenient:

The fact that I don't have a computer makes it much harder for me; sometimes it's even impossible to learn. I'm doing everything through my cell phone and it's very problematic. The screen is small, WhatsApp messages keep popping up, and it is difficult to hand in assignments using it. I can't really call it “learning.” (Rim, B-PST, REF-12).

Even among those who reported having access to a computer (or smartphone), there were other problems, prominent among them the lack of sufficient infrastructure for uninterrupted Internet communication. With the existing conditions, the transfer of information was very slow and Internet access was disrupted or cut off several times during the lesson, which made it difficult to maintain continuity and caused the participants a great deal of frustration.

Studying online using the Internet is very frustrating. I'm constantly trying to join the lesson and to follow it, but in the middle of a lesson, my computer suddenly gets stuck. Where I live, we do not have access to good-quality infrastructure. So, when the computer suddenly disconnects from the network, I can no longer follow the lesson. Thus, I catch about half of what is going on. (Fatima, B-PST, FG-B)

As it appears, the absence of essential technical apparatus, such as computers, as well as sufficient Internet infrastructure could prevent students from engaging in the learning process. At the very least, this situation leads to feelings of frustration and creates conditions of educational inequity.

-

(b)

Culturally-based Constraints

One of the difficulties described as preventing learners from engaging in the online-learning process was culturally-based constraints involving women's social roles in a traditional society. Such traditional societies may include Bedouin students, as well as ultra-Orthodox and Ethiopian students. Each of these groups operates as a traditional society, which demands that the woman's role in the domestic arena should be her top priority. For example, Asma, a Bedouin student who is married and has children, described the conflict she experienced between fulfilling her maternal and marital roles and meeting the demands of online studies while being confined to her home due to the pandemic.

It's difficult because I am a student mother. As a homemaker, I want to successfully manage all of my responsibilities toward the children and my husband …, while continuing to perform well in my studies. It's very difficult … For example, if a child starts crying during an online class, I don't know what to do first: Should I focus on the lesson or attend to the crying child.… I feel like Wonder Woman: I get up in the morning clean the house, do the chores, prepare breakfast for the children, and then sit down to study; then dinner … The children don't understand that I have to focus and study and they complain: “Why are you on the phone all the time?” (She sighs.) (Asma, B-PST, INW-15)

Thus, it appears that the difficulty of combining the role of mother and spouse with the demands of online learning stems from the convergence of the two activities in terms of both time and place. Furthermore, some participants mentioned that the children, as well, need to use the smartphone to attend their online classes and, as mothers, they are expected to prioritize the children's needs.

Another manifestation of this culturally-based home-career contradiction was reported regarding the participants’ role as daughters or sisters who are expected to assume responsibilities in the home: “As the eldest sister, with five younger brothers, I feel immense pressure to help my mother before I can attend the online class. This is difficult” (Suhir, REF-23). These expectations are manifested particularly when there are family members with special needs. Thus, for example, Adis, who is an immigrant from Ethiopia and thus is part of an ethnic minority, has a younger sibling with special needs.

I am at home and I have a younger brother who has Williams syndrome. He is at home because the schools are closed. My mother works, so I'm the one who takes care of my brother during the day. That's why I am less available for online studies because, as the older sister, I have an enormous responsibility. I must care for him, make sure he eats, and keep him occupied with various activities. (Adis, J-PST, INW-55)

Adis demonstrates that domestic needs hinder the process of engaging in learning not only in cases of married students but also in cases of unmarried students, who belong to a traditional society and are requested to assist in the domestic chores. In conclusion, it appears that culturally-based constraints deprive some students of the ability to thoroughly engage in online learning. It is worth noting that, as will be shown, these conditions were characteristic of primarily minority group participants, in the case of this study – mainly among Bedouin students.

5.8. The ensuing phase: adjustments to the environment and the process of online learning

The ensuing phase involves maintaining, enhancing, and maximizing the effectiveness of the online-learning experience, by adjusting to the unique features of online learning and applying specific study skills.

-

(a)

Features of Online Learning

This theme corresponds to the challenges encountered in the ensuing phase, when online learning is in process, and it relates to the practical features of the online experience. Three major challenges were mentioned. The first challenge involved remaining seated passively for a long period of time in front of the monitor during the online learning:

I find it difficult to get used to remaining seated in front of the computer monitor for hours upon hours – I don't like it. This type of studying is much more exhausting than normal classroom studies. Even after long days on campus, I had never been so tired at the end of the day. I think that the duration of the lessons should be shortened, as it is difficult to concentrate after a certain amount of time. (Sara, J-PST, REF-79)

As appears, remaining seated in front of the computer screen for a continuous time was described as an exhausting experience that takes a toll on one's ability to concentrate. A second challenge mentioned by students was the difficulty to get used to learning via the asynchronous learning method. In contrast to the synchronous online teaching method, which features real-time live lessons delivered through a video conferencing platform (such as ZOOM), the asynchronous teaching method involves the dissemination and storage of readings, assignments, or prerecorded oral lectures accompanied by PowerPoint presentations and/or interactive assignments (Peachey, 2017). Interestingly, although it may be more convenient to learn asynchronically (as one may choose when to learn), students found it difficult to learn this way.

Having asynchronous lessons makes it much harder for me to study. I feel that it is a very superficial learning experience. Sometimes lecturers send summaries, long reading assignments, and a presentation which they expect us to learn all on our own. (Debora, J-PST, FG-J)

In part, this difficulty might be the result of lecturers' lack of knowledge of how to implement effectively the asynchronous learning method, given that the shift to exclusive online learning occurred unexpectedly. However, it should be noted that participants from the B-PST group preferred the asynchronous method, as it enabled them to study at times that were convenient for them.

I like it better when the lesson is not live online and instead the teacher gives us a recorded lesson or presentation. It raises fewer difficulties for me, as I can study in my own time. It's a much more logical arrangement, given the need to juggle all my chores. In some cases, I can also download it when the Internet connection is strong enough and watch it later. But still, only if there is not an overload of assignments. (Hanam, B-PST, FG-B)

As described, the asynchronous teaching method enables some learners to keep up with their learning as it enables them to juggle their chores by choosing the time which is most suitable for them to learn. A third feature characterizing online learning that was experienced as a challenge for students was the absence of collaborative, face-to-face learning. Participants missed the social face-to-face interaction and perceived this learning method as involving less-than-optimal conditions for asking questions, especially when the course was attended by a large number of students.

I miss the traditional way of learning, before we entered the era of the COVID-19 pandemic … The ability to conduct class discussions during online learning is very limited, which makes it difficult to gain an in-depth understanding … Also, I feel that when we learn online, many times our questions are disregarded. I don't feel that I am getting a good grasp of the material, the way it was when we had the advantage of face-to-face class discussions. (Yael, J-PST, INW-61)

It appears that the learners perceived the face-to-face discussions as providing the best learning opportunity, a framework that allows the learners to ask questions directly and benefit from examples described by the teacher. Hence, the current online-learning format is experienced as lacking as it detracts from the quality of the learning.

In conclusion, the three online-learning features that were experienced as challenging according to the participants' opinions were as follows: remaining passively seated in front of a computer screen, the quality of lessons through the asynchronous teaching method, and the lack of face-to-face collaborative learning. It appears that these external, objective factors hindered participants’ learning effectiveness as well as their subjective perceptions regarding their ability to manage their learning sufficiency.

-

(b)

Study Skills Needed for Online Learning

This theme, too, corresponds to the ensuing phase, when online learning is in progress; however, it concerns the academic challenges, which are related to the skills required for effective learning online. Accordingly, many participants described the challenge of making personal adjustments vis-à-vis the new study format and their feelings of uncertainty given the novelty of the experience. Primarily, the adjustment seemed to involve the acquisition of a particular set of study skills, and participants noted the absence of guidance and preparation for managing the new challenges, especially considering the fluid situation, in which the instructional format was constantly changing (resulting from the lack of certainty involving the COVID-19 situation).

The distance-learning method is completely different from the learning method that I am used to, and so, I'm having a hard time adjusting to the change …. Many of my friends seem to get lost, as the system is unclear and constantly changing. And no one prepared us for this type of learning! I am not sure what is the best way to study in this framework. Should I summarize lessons as usual?. I'm wondering if my notetaking is good enough, and if I'll really be able to prepare for exams effectively (Avital, J-PST, INW-44)

As this learning method is novel as requires unique skills, students found it difficult to learn as they were not trained by anyone how to learn effectively this way. Furthermore, participants described the need to organize their study schedule and their learning methodology independently. Some described the difficulty, yet were able to contend with it, whereas others felt completely lost.

Online learning is difficult and different from on-campus learning. Now I need to keep track of all the lessons and assignments myself.… I need to know how to plan my schedule so that I do not miss any lesson or an assignment. On campus, I used to go with my friends to every lesson, there is no confusion, it's really very difficult to keep track of everything that one needs to do on my own. (Lea, J-PST, INW-37)

As appears, Lea compared this experience with studying on the campus according to a schedule that was preorganized and inherent to the framework. This used to make her learning more arranged, whereas now she is requested to manage her schedule and acquire new skills. Moreover, this new skill of self-organizing requires exercising self-discipline, avoiding distractions, remaining motivated to succeed, and adhering to deadlines. Participants found it difficult to make these adjustments, given the numerous stimuli they encountered at home.

Online studies require a great deal of self-discipline; however, to tell the truth, I have become increasingly idle from moment to moment. Sometimes I have no motivation or drive to get out of this funk.… The study load is heavy and every day I have to force myself to sit and study while ignoring all the other stimuli around me.… I find it very difficult to study on my own, which I have to do now that the classes are all online.… I'm very worried that I won't keep up with the study schedule or that I'll miss some material or assignment over time. (Tal, J-PST, REF-87)

It appears that the essential study skills required for online learning were different from the participants’ customary approach to studying, which raised various concerns, especially given that this transformation was unexpected and, hence, afforded them no prior preparation.

Overall, it appears that there were a variety of difficulties that accompanied both phases of the online-learning experience. Fig. 1 summarizes the four themes identified in the current study regarding the phase (Preliminary phase vs. ensuing phase) and their essence (technical vs. essential).

Fig. 1.

The study model: the four themes identified regarding the phase (Preliminary phase vs. ensuing phase) and their essence (technical vs. essential).

Although all of the students mentioned encountering these difficulties to some extent, we sought to examine whether there were differences between the sociocultural groups in terms of the rate at which they experienced these difficulties.

6. Comparing Bedouin and Jewish preservice teachers online learning challenges –research question 2

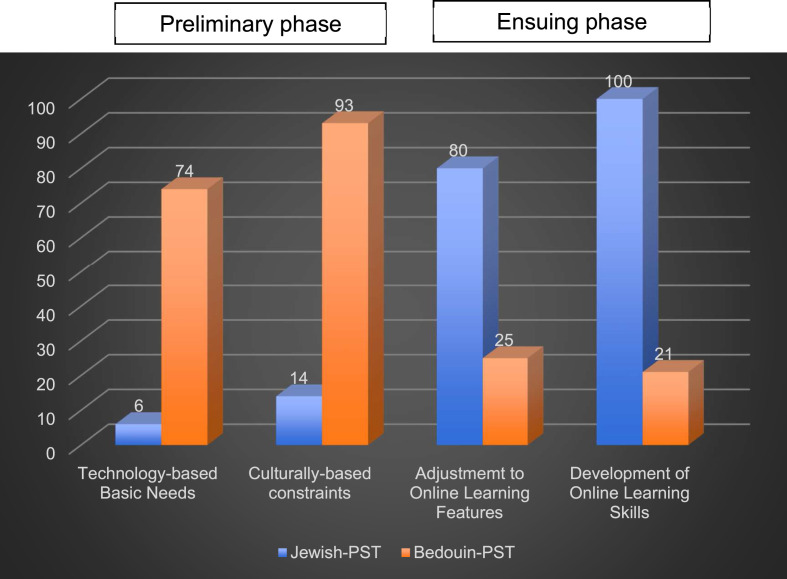

This subsection presents the findings of the comparison between the online-learning challenges of B-PSTs and J-PSTs; specifically, the frequency with which the themes were mentioned by each group. Fig. 2 presents a summary of these findings.

Fig. 2.

The Frequency of Reported online Learning Challenges (%): A Comparison between Bedouin and Jewish Female Preservice Teachers.

As shown in Fig. 2, the challenges reported in the context of the preliminary phase, i.e., the conditions that enable engagement in online learning, were the challenges most frequently mentioned by the B-PSTs, whereas most of the J-PSTs' challenges were mentioned in the context of the ensuing phase. These different patterns are likely to affect the quality and quantity of learning. For instance, 74% of the B-PSTs mentioned the lack of computers or problems related to Internet infrastructure and a slow Internet connection, as compared to 6% among the J-PSTs. It is worth noting that the individuals in the J-PST group who reported no—or only one—computer in the home belonged to the minority group of Jewish students of Ethiopian descent, which constitutes a socioeconomically marginalized group.

Another distinction between the groups was the challenge of avoiding a potential conflict between the demands of their familial roles and the demands of online learning, a conflict that was more prevalent among the B-PSTs than among the J-PSTs (93% vs. 14%, respectively). As shown in Table 1, most B-PST students were married (37%) and had children (37%), in contrast to the family status of those in the J-PST group (15% married, 12% have children). Not only does the traditional Bedouin culture encourage early marriage and the proliferation of offspring but it also assigns all the daily chores of caring for the family exclusively to women-whether married or single. Hence, the task of combining familial and academic roles was more challenging for the B-PSTs than for their counterparts.

The reported challenges that corresponded to the ensuing phase were mentioned more frequently by the J-PSTs than by the B-PSTs. This indicates that whereas most B-PSTs’ focused their efforts on the basic conditions without which they would not be able to participate in online learning, most of the J-PSTs focused their efforts on making online learning an effective experience. Typically, such differences eventually lead to different learning pathways, as demonstrated in Fig. 3 .

Fig. 3.

The Culturally-based Dual Pathway Model of Online Learning challenges.

Fig. 3 is a diagram of the differential learning pathways available to distinct sociocultural groups. It demonstrates that ultimately, the learning pathway that is open to B-PSTs, who belong to a marginalized minority, is different from the pathway open to J-PSTs, who represent the mainstream population. At their starting point, the J-PSTs were free to attend to challenges related to the effective management of their learning process, compared to their Bedouin counterparts, who from the outset had to struggle to obtain the necessary resources that would provide them with the preliminary learning conditions that learners from the mainstream population already enjoy. This initial gap ultimately leads to a path on which the stronger mainstream learners thrive while the members of the deprived minority are perpetually struggling to close the gap.

7. Discussion

This study examined the online-learning challenges among Bedouin and Jewish preservice female teachers during the COVID-19 shift to exclusive online education, in light of the digital divide discourse. It provides theoretical insights alongside practical implications for both routine and emergent online education, which are required to ensure educational equity. Specifically, the study has several contributions to the existing literature. First, it shows that the divide is still present on all three levels (access, usage and skills, and outcomes), and second, by detecting the differential pathways through which PSTs of different sociocultural groups experience online-learning challenges, it sheds light on the significance of an understudied aspect of the digital divide – the sociocultural values and their role during a crisis. Specifically, it shows that whereas J-PSTs were mainly concerned with how to effectively manage their learning process, their Bedouin counterparts were struggling to equate their learning conditions with those available to their Jewish counterparts, due to cultural circumstances. The study contributes to the digital divide discourse by demonstrating that sociocultural factors – specifically values, must be addressed to ensure digital equity. One of the most significant barriers to learning among female Bedouin preservice teachers is related to the Bedouin prioritization of the tribe's social order, values, and roles over education (Al-Krenawi, 2004; Kass & Miller, 2011). This is particularly relevant when the domestic background is intensified due to a crisis that affects the teacher education system. Previous studies have shown that attitudes can be a detrimental factor that manifests on the first-level of the digital divide (Helsper & Reisdorf, 2017; van Dijk, 2005); however, the impact of sociocultural factors (e.g., collective values) on attitudes that further the digital divide has hardly been addressed. Moreover, the study reinforces prior claims (Van Deursen and Van Dijk, 2014, Van Deursen and Van Dijk, 2019) that the digital divide did not vanish following recent technological developments but rather received other manifestations, which need to be examined and attended. As the current findings indicate, cultural aspects and values should be addressed, to mitigate gender and minority group learners' digital disadvantage and ensure social inclusion in teacher education (Carter Andrews et al., 2017; Guðjónsdóttir et al., 2008; Heemskerk et al., 2011; Hendin et al., 2016).

Furthermore, the study provides a comprehensive description of the challenges arising from the sudden transition to the exclusive use of online learning, indicating the major aspects that should be addressed to support such change. Nonetheless, the study's ramifications are pertinent not only to the COVID-19 crisis but also to future implementations of online learning in routine circumstances. It should be emphasized that while the educational situation resulting from the pandemic provides an opportunity to develop long-term, innovative online educational models (OECD, 2020), this process should be well-planned and carefully managed. As all of the abovementioned findings have practical implications for designing future online learning, we propose the following recommendations, according to the four main online-learning challenges detected in the study.

8. Attending the challenge of culturally-based constraints: considering learners’ familial and sociocultural values and roles

The first and foremost implication of this study involves the need to consider learners' familial and sociocultural backgrounds and values, as findings indicated that this aspect had a major impact on participants' learning pathways. These findings correspond to previously documented findings regarding the roles of gender (Hilbert, 2011) and region (Graham et al., 2012) vis-à-vis the digital divide, yet the current study underscores the combined role of gender-based cultural values, which may impair learning in times of crisis. Specifically, the Bedouin tribal ideology enables education as long as it does not disrupt women's social roles. Hence, interventions to mitigate the digital divide should also address this aspect, by appealing to key figures in the community, when an unexpected crisis disrupts the normal balance of roles.

Counter to the expectation that access to technology would enhance minority groups' and women's participation in the digital world, the current study demonstrates that in times of crisis, when the cultural context is emphasized, the opposite is true. Specifically, learning from home using technology does not entail social inclusion. Thus, policy makers should rethink this issue. In fact, it appears that establishing neighborhood sites equipped with the technology necessary for online learning (e.g., in community centers or libraries) would be a more beneficial way to support female minority students' distance learning in times of crisis.

Scholars worldwide have expressed concern about the problematic link between the COVID-19 pandemic and the intercultural context of education (Dervin et al., 2020). Indeed, our study shows that distance learning has underscored not only the lack of resources in Bedouin society but also its gender-based traditional values and roles, which tend to disrupt women's online learning. This sociocultural aspect should become part of the ongoing discourse on the digital divide and should be addressed in line with the recommendations for culturally responsive teaching (Vass, 2017) and inclusive pedagogies (Guðjónsdóttir et al., 2007), as ways to foster social justice and digital equity. Teacher educators and policy makers in teacher education should implement pedagogical adaptations to avoid educational inequity on the basis of race or gender (Mutahi & Gazda, 2019). These include considering the familial obligations and roles of female students belonging to traditional sociocultural or religious backgrounds.

Many of the Bedouin female students were also young parents, a characteristic that stems from the woman's role in this traditional tribal culture (Abu-Rabia-Queder, 2007). Distance learning places a heavy burden on parents, who find themselves struggling to support their children's learning process while simultaneously juggling the demands of their job with those of the household chores. A recent UNESCO report has recommended lessening the burden that parents experience during the pandemic (UNESCO, 2020). In the case of B-PSTs, not only did they face the increased burden of supervising their children's distance learning while engaging in domestic chores, but they also needed to attend to their own studies while at home, where their primary role is as homemakers. This juggling of tasks becomes exceedingly difficult when there is only one computer in the home. Hence, in terms of the digital divide, the sociocultural background entailed difficulties on all three levels: access difficulties, cultural-based usage constraints, and eventual outcomes. In conclusion, when designing future online learning, students' familial and sociocultural backgrounds, as well as their values and roles, need to be considered, to ensure educational equality.

8.1. Attending to the learning apparatus challenge: providing online-learning facilities

The first-level digital divide refers to Internet access and material access. The latter includes computer devices, software, and equipment (van Deursen & van Dijk, 2019). The current study empirically indicates that, despite worldwide technological developments, the first-level digital divide has not vanished and remains a serious problem for learners of minority groups.

As such, it is essential to provide online-learning facilities to mitigate learning gaps among learners. This may be achieved by expediting computer donations to Bedouin students (a step that was eventually taken during the pandemic by the institution where this study was conducted) or by opening adequately equipped public learning centers. In fact, providing access to the Internet and technology to minimize the digital divide and ensure effective online learning was suggested prior to the COVID-pandemic (McLoughlin, 2001; Van Deursen and Van Dijk, 2019), but was significantly emphasized following it (Dhawan, 2020; Mseleku, 2020). Creativity and flexibility can help ensure that learners receive equitable learning opportunities.

8.2. Attending to the challenge of online-learning features: enabling different online-learning methods

Findings indicated that different learners needed different online-learning methods to enable learning. For example, B-PSTs found that the synchronous online-learning method, which involves real-time live lessons delivered through video conferencing platform posed difficulties (resulting from their multiple tasks and the limited number of computers available at a given time); thus, they preferred the asynchronous learning method, which involves the storage of prerecorded lectures accompanied by assignments, available for use in one's own time (Peachey, 2017). In contrast, J-PSTs preferred synchronous online-learning, as most of them were single or without children. This can be viewed as part of the second-level digital divide, i.e., the usage aspect. Echoing previous findings (van Deursen & van Dijk, 2014), our study indicates the need to address the usage aspect, emphasizing that it may involve teaching methods that ultimately relate to the learner's technology usage. As such, adaptations in teaching methods may help mitigate the digital divide. In fact, it was argued before the pandemic that a successful distance-learning program must encourage the development of innovative teaching methods, to address the needs of special populations and meet the requirements of culturally diverse learners (Lagier, 2003).

To this end, McLoughlin (2001) discussed a framework for culturally inclusive pedagogy that should be applied to online environments. Accordingly, teaching effectively in a cross-cultural online context involves making adaptations to curriculum, assessment, and teaching approaches, so that these align with crosscultural learning needs. Scholars noted the need to build appropriate online-learning pedagogies, by creating an effective social context for learning. (Sims et al., 2008). Thus, it is recommended that the learning method be adjusted according to the particular track, such that tracks comprised mostly of either Bedouin women or young mothers would mainly learn asynchronously. Alternatively, it is possible to conduct online lessons in which attendance is not mandatory, by recording the lessons and making them available for viewing at a later and more convenient time.

In line with previous suggestions (Moorhouse, 2020), it is recommended that synchronous online learning be conducted in small groups These are more likely to enable personal interaction, collaborative learning via group discussions, and the opportunity to achieve some of the benefits of face-to-face interactions in learning. Furthermore, in the small-group format, it is easier to offer assistance tailored to the needs of each student. This may be achieved using the “Break-out Room” option, which enables the teacher to actively engage with individual learners and give them personal attention (Moorhouse, 2020). In conclusion, attending to the challenging features of online learning as part of the second-level digital divide involves the development of instructional strategies and learning activities tailored for the effective delivery of online distance education for diverse learners' needs.

8.3. Attending to the online-learning skills challenge: providing instruction about online-learning skills

The second level digital divide also involves learners' skills, that eventually result with learning outcomes (third level digital divide). Despite students' familiarity with technology, when they faced the need to learn exclusively online, some were lost. This corresponds to prior findings that argued that the divides in skills and type of use will continue to exist even after physical access is universal (Van Deursen & van Dijk, 2019). Interestingly, prior literature in teacher education has emphasized the need to provide ICT training for teacher educators (Lavonen et al., 2006). If professional educators need guidance, there is all the more reason to assume that this would constitute an essential need also for first-year learners in a teacher-education program. Such skill training may involve aspects of self-regulation in online learning (Cho & Shen, 2013), for instance, acquiring skills to enhance students' resilience to digital distractions (Hatlevik & Bjarnø, 2021). Providing skill training would enable PSTs to optimize the online-learning experience. This is essential, particularly among Bedouin students, who are likely to teach in their communities. Thus, if they are well-trained, they are likely to use these skills effectively in their teaching (Admiraal et al., 2017); in the long-term, this may facilitate social change regarding the use of online learning in classrooms. Additionally, given the gender digital divide, according to which male preservice teachers use ICT more effectively than do their female counterparts (Tezci, 2011), it is imperative to offer this instruction primarily—but not exclusively-to female students.

9. Implications and limitations

In conclusion, this study provides a theoretical insight into the online-learning challenges that arose during the COVID-19 pandemic, by identifying their manifestations in relation to the digital divide perspective, among learners of different sociocultural backgrounds, in this case, Bedouin and Jewish female preservice teachers. Based on these findings, recommendations were formulated to address practical implications for policy makers and pedagogical adaptations for teachers, to better support online learning and mitigate the digital divide and inequities between learner groups.

The study has several limitations. First, it features a cross-sectional design; therefore, it does not document changes in the process over time. Indeed, longitudinal studies are needed to further deepen our understanding of the online-learning challenges, and whether these change over time and with gained experience. Second, as the data were collected in the middle of the semester during the first “wave” of the COVID-19 pandemic, it would have been interesting to check whether, by the end of the following semester, students exhibited the same difficulties or had managed to adapt effectively. Third, as this study was conducted during a crisis, it may not reflect the challenges that are encountered in ordinary times. Future research may be conducted among other ethnic minority groups, such as students of Ethiopian descent, as well as students of different faiths and cultures, as one's socio-cultural and religious background was found an essential factor affecting one's adjustment to sudden or traumatic changes (Frei-Landau et al., 2020a,b). Despite these limitations, we believe that the insights into the online-learning challenges that were gained in this study, particularly as regards a marginalized minority group, have the potential to increase our understanding of what is needed to facilitate culturally responsive teaching and educational equity for all learners.

10. Conclusions

This study explored the online distance-learning challenges encountered by (minority) Bedouin female preservice teachers compared to those encountered by their (majority) Jewish counterparts, during the COVID-19 shift to online education. It provides theoretical insights alongside practical implications for both routine and emergent online teacher education, policy changes, and pedagogical adaptations, which are required to ensure educational equity. It highlights the gender-related socioculturally-based aspects that need to be addressed to mitigate the digital divide. Gaining insight into ways to ensure equitable online teacher education is imperative as part of inclusion policy and social justice.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Biographies

Bio: Rivi Frei-Landau (PhD) is a psychologist and a lecturer at the School of Education & The Culturally-Sensitive Clinical Psychology Program, Achva Academic College. Frei-Landau is currently a Post-doctoral fellow in The MOFET institute for Teacher Education. Her research interests include innovative technology in teaching and learning in a social-emotional perspective (SEL) as well as multicultural aspects of coping with loss and crisis in the educational arena.

Prof. Orit Avidov-Ungar is a Professor and the dean of the School of Education, Achva Academic College. She also works at the Israeli Open University. She was member of the Education Ministry's team that developed the new educational reforms aimed at adapting the teaching profession to the realities and needs of the 21st century. Her major research interest is educational policy, processes of educational change and in empowerment of teachers using new methods and technologies.

Footnotes

B-PSTs = Bedouin preservice teachers; J-PSTs = Jewish preservice teachers.

References

- Abu-Rabia-Queder S. Coping with “forbidden love” and loveless marriage: Educated Bedouin women from the Negev. Ethnography. 2007;8(3):297–323. [Google Scholar]

- Abu-Rabia-Queder S., Karplus Y. Regendering space and reconstructing identity: Bedouin women's translocal mobility into Israeli-Jewish institutions of higher education. Gender, Place & Culture. 2013;20(4):470–486. [Google Scholar]

- Abu-Rabia-Queder S., Weiner-Levy N. Identity and gender in cultural transitions: Returning home from higher education as “internal immigration” among Bedouin and Druze women in Israel. Social Identities. 2008;14(6):665–682. [Google Scholar]

- Abu-Rabia-Queder S. Higher education as a platform for cross-cultural transition: The case of the first educated Bedouin women in Israel. Higher Education Quarterly. 2011;65(2):186–205. [Google Scholar]

- Abu-Saad I. Access to higher education and its socio-economic impact among Bedouin Arabs in Southern Israel. International Journal of Educational Research. 2016;76:96–103. [Google Scholar]

- Abu-Saad I., Horowitz T., Abu-Saad K. Confronting barriers to the participation of Bedouin-Arab women in Israeli higher education. Literacy Information and Computer Education Journal. 2017;8(4):2766–2774. [Google Scholar]

- Admiraal W., van Vugt F., Kranenburg F., Koster B., Smit B., Weijers S., Lockhorst D. Preparing pre-service teachers to integrate technology into K–12 instruction: Evaluation of a technology-infused approach. Technology, Pedagogy and Education. 2017;26(1):105–120. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Krenawi A. Beer Sheva Center for Bedouin Studies and Development; 2004. Awareness and utilization of social, health/mental health services among Bedouin–Arab women, differentiated by type of residence and type of marriage. [Google Scholar]

- Alhazail A., Atawna R. The Arab woman in the Negev: Reality and challenges. A report of Ma’an, the Forum of Arab Women’s Associations in the Negev; 2005. Social rights; pp. 53–61. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Allen J., Rowan L., Singh P. Teaching and teacher education in the time of COVID-19. Asia-Pacific Journal of Teacher Education. 2020;48(3):233–236. doi: 10.1080/1359866X.2020.1752051. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Alt D. Science teachers' conceptions of teaching and learning, ICT efficacy, ICT professional development and ICT practices enacted in their classrooms. Teaching and Teacher Education. 2018;73:141–150. [Google Scholar]

- Austin R. The role of ICT in bridge-building and social inclusion: Theory, policy and practice issues. European Journal of Teacher Education. 2006;29(2):145–161. [Google Scholar]

- Avidov-Ungar O., Shamir-Inbal T., Blau I. Typology of digital leadership roles tasked with integrating new technologies into teaching: Insights from metaphor analysis. Journal of Research on Technology in Education. 2020:1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Beschorner B. Revisiting Kuo and Belland's exploratory study of undergraduate students' perceptions of online learning: Minority students in continuing education. Educational Technology Research & Development. 2021;69(1):47–50. doi: 10.1007/s11423-020-09900-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogdan R.C., Biklen S.K. Pearson; 2007. Qualitative research in education: An introduction to theory and methods. [Google Scholar]

- Carr S. A tribal college sticks to its values as it embraces distance education. The Chronicle of Higher Education. 2000;47(5) [Google Scholar]

- Carrillo C., Flores M.A. COVID-19 and teacher education: A literature review of online teaching and learning practices. European Journal of Teacher Education. 2020;43(4):466–487. [Google Scholar]

- Carter Andrews D.J., Richmond G., Stroupe D. Teacher education and teaching in the present political landscape: Promoting educational equity through critical inquiry and research. Journal of Teacher Education. 2017;68(2):121–124. [Google Scholar]

- Central Bureau of Statistics 2018. https://www.cbs.gov.il/he/publications/doclib/2019/2.shnatonpopulation/st02_15x.pdf

- Choi T.H., Chiu M.M. Toward equitable education in the context of a pandemic: Supporting linguistic minority students during remote learning. International Journal of Comparative Education and Development. International Journal of Comparative Education and Development. 2021;23(1):14–22. [Google Scholar]

- Cho M.H., Shen D. Self-regulation in online learning. Distance Education. 2013;34(3):290–301. [Google Scholar]

- Corbin J., Strauss A. Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory. 3rd ed. Basics of qualitative research; 2008. Strategies for qualitative data analysis; pp. 65–86. SAGE. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dervin F., Chen N., Yuan M., Jacobsson A. COVID-19 and interculturality: First lessons for teacher educators. Education and Society. 2020;38(1):89–106. [Google Scholar]

- Dewi P., Muhid A. Students' attitudes towards collaborative learning through E-learning during COVID-19: Male and female students. English Teaching Journal: A Journal of English Literature, Language and Education. 2021;9(1):26–33. [Google Scholar]

- Dhawan S. Online learning: A panacea in the time of COVID-19 crisis. Journal of Educational Technology Systems. 2020;49(1):5–22. (. [Google Scholar]

- DiMaggio P., Hargittai E., Celeste C., et al. In: Social inequality. Neckerman K., editor. Russell Sage Foundation; 2004. From unequal access to differentiated use: A literature review and agenda for research on digital inequality; pp. 355–400. [Google Scholar]

- Dorner H., Kumar S. Online collaborative mentoring for technology integration in pre-service teacher education. TechTrends. 2016;60(1):48–55. [Google Scholar]

- Frei-Landau R. “When the going gets tough, the tough get—creative”: Israeli jewish religious leaders find religiously innovative ways to preserve community members' sense of belonging and resilience during the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy. 2020;12(S1):S258. doi: 10.1037/tra0000822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frei-Landau R., Hasson-Ohayon I., Tuval-Mashiach R. The experience of divine struggle following child loss: The Case of Israeli bereaved Modern-Orthodox parents. Death Studies. 2020:1–15. doi: 10.1080/07481187.2020.1850547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frei-Landau R., Tuval-Mashiach R., Silberg T., Hasson-Ohayon I. Attachment to God as a mediator of the relationship between religious affiliation and adjustment to child loss. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy. 2020;12(2):165. doi: 10.1037/tra0000499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frei-Landau R., Tuval-Mashiach R., Silberg T., Hasson-Ohayon I. Attachment to god among bereaved jewish parents: Exploring differences by denominational affiliation. Review of Religious Research. 2020;62(3):485–496. [Google Scholar]

- Gabster B.P., van Daalen K., Dhatt R., Barry M. Challenges for the female academic during the COVID-19 pandemic. The Lancet. 2020;395(10242):1968–1970. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31412-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham M., Hale S., Stephens M. Featured graphic: Digital divide: The geography of Internet access. Environment & Planning A. 2012;44(5):1009–1010. [Google Scholar]

- Guðjónsdóttir H., Cacciattolo M., Dakich E., Davies A., Kelly C., Dalmau M.C. Transformative pathways: Inclusive pedagogies in teacher education. Journal of Research on Technology in Education. 2007/8;40(2):165–182. [Google Scholar]

- Hatlevik O.E., Bjarnø V. Examining the relationship between resilience to digital distractions, ICT self-efficacy, motivation, approaches to studying, and time spent on individual studies. Teaching and Teacher Education. 2021;102:103326. [Google Scholar]

- Heemskerk I., Volman M., Ten Dam G., Admiraal W. Social scripts in educational technology and inclusiveness in classroom practice. Teachers and Teaching: Theory and Practice. 2011;17(1):35–50. [Google Scholar]

- Helsper E.J., Reisdorf B.C. The emergence of a “digital underclass” in Great Britain and Sweden: Changing reasons for digital exclusion. New Media & Society. 2017;19(8):1253–1270. [Google Scholar]

- Hendin A., Ben-Rabi D.A.L.I.A., Azaiza F. Access to higher education. Routledge; 2016. Framing and making of access policies: The case of Palestinian Arabs in higher education in Israel; pp. 159–171. [Google Scholar]

- Hilbert M. Digital gender divide or technologically empowered women in developing countries? A typical case of lies, damned lies and statistics. Women's Studies International Forum. 2011;34(6):479–489. [Google Scholar]

- Holstein J. In: Handbook of qualitative research. Denzin N.K., Lincoln Y.S., editors. Sage; 1994. Phenomenology, ethnomethodology, and interpretive practice; pp. 105–117. [Google Scholar]