Abstract

Humoral (antibody [Ab]) and cellular Candida-specific immune responses in the vaginas of pseudoestrus rats were investigated during three successive infections by Candida albicans. After the first, protective infection, Abs against mannan and aspartyl proteinase antigens were present in the vaginal fluid, and their titers clearly increased during the two subsequent, rapidly healing infections. In all animals, about 65 and 10% of vaginal lymphocytes (VL) were CD3+ (T cells) and CD3− CD5+ (B cells), respectively. Two-thirds of the CD3+ T cells expressed the α/β and one-third expressed the γ/δ T-cell receptor (TCR). This proportion slightly fluctuated during the three rounds of C. albicans infection, but no significant differences between infected and noninfected rats were found. More relevant were the changes in the CD4+/CD8+ T-cell ratio, particularly for cells bearing the CD25 (interleukin-2 receptor α) marker. In fact, a progressively increased number of both CD4+ α/β TCR and CD4+ CD25+ VL was observed after the second and third Candida challenges, reversing the high initial CD8+ cell number of controls (estrogenized but uninfected rats). The CD3− CD5+ cells also almost doubled from the first to the third infection. Analysis of the cytokines secreted in the vaginal fluid of Candida-infected rats showed high levels of interleukin 12 (IL-12) during the first infection, followed by progressively increasing amounts of IL-2 and gamma interferon during the subsequent infections. No IL-4 or IL-5 was ever detected. During the third infection, VL with in vitro proliferative activity in response to an immunodominant mannoprotein antigen of C. albicans were present in the vaginal tissue. No response to this antigen by mitogen-responsive blood, lymph node, and spleen cells was found. In summary, the presence of protective Ab and T helper type 1 cytokines in the vaginal fluids, the in vitro proliferation of vaginal lymphocytes in response to Candida antigenic stimulation, and the increased number of activated CD4+ cells and some special B lymphocytes after C. albicans challenge constitute good evidence for induction of locally expressed Candida-specific Ab and cellular responses which are potentially involved in anticandidal protection at the vaginal level.

Vaginal candidiasis is a widespread, common disease affecting a substantial proportion of childbearing-age women (27), but the pathogenesis of this frequent clinical problem remains elusive. Clinical studies on recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis as well as several investigations with estrogen-dependent murine models of vaginal candidiasis (9, 10) led to the suggestion that cell-mediated immunity (CMI) plays a critical role in anticandidal protection at the vaginal level. However, the specific nature of the cellular immunoprotective factor(s) has not been identified. Somewhat in contrast with the above suggestion, evidence from experimental settings points to antibodies (Abs) against specific virulence factors of the fungus playing a critical role in protection. In fact, anticandidal protection can be efficiently conferred by actively induced or passively administered antimannan and anti-secretory aspartyl proteinase (Sap) Abs, inclusive of specific monoclonal Abs in both rat and mouse models of vaginal candidiasis (3, 4, 14, 15, 20). Nonetheless, this contrast may be apparent only as CMI exerts a critical regulatory role in anticandidal responses (26), as also witnessed by the lack of protection induced by active Candida antigen immunization in congenitally athymic, nude rats (3). Thus, the study of cellular immunity at the vaginal level remains a key point for an understanding of local host defense, whatever the ultimate effector mechanism. Accordingly, we have attempted to identify the T-cell populations in the vaginal mucosa of naive and Candida-infected rats. Antigen-induced expansion and activation of lymphocyte populations, and cytokines in the vaginal fluid of infected, nonimmune and immune rats were also sought for to obtain possible insights into the immunoregulatory mechanisms operating at the vaginal level during, and possibly acting against, Candida infection.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Microorganisms and growth conditions.

The yeast used throughout this study was Candida albicans SA-40, originally isolated from the vaginal secretion of women with acute vaginitis (4). For the experimental infection (see below), a stock strain from Sabouraud-dextrose agar (Difco, Laboratories, Detroit, Mich.) was grown in YEPD medium (yeast extract, 1%; neopeptone, 2%; dextrose, 2%) for 24 h at 28°C under mild shaking, then harvested by centrifugation (3,500 × g), washed, and suspended to the required number in saline solution.

Animals.

Oophorectomized female Wistar rats (80 to 100 g; Charles River Breeding Laboratories, Calco, Italy) were used throughout the study. Animal maintenance, estrogen treatment, and general design of both the primary infection and rechallenges were as described elsewhere (3, 4).

Experimental rat vaginitis.

The experimental infection was carried out in oophorectomized rats essentially as described elsewhere (4) except that a greater C. albicans inoculum (108 rather than 107 cells) in 0.1 ml of saline solution was used. Briefly, all rats were maintained under pseudoestrus by subcutaneous administration of estradiol benzoate (Benzatrone; Samil, Rome, Italy). Six days after the first estradiol dose, the animals were inoculated intravaginally with the fungal cells, the number of which in the vaginal fluid was monitored by culturing 1-μl samples (taken from each animal by a calibrated plastic loop [Disponoic; PBI, Milan, Italy]) on Sabouraud agar containing chloramphenicol (50 μg/ml), as previously described (3, 4). A rat was considered infected when at least 1 CFU was present in the vaginal sample (i.e., a count of ≥103 CFU/ml). Some other vaginal samples were also stained by a periodic acid-Schiff-van Gieson method for microscopic examination. This infection was repeated a second and a third time, after resolution of each preceding infection by an equal challenge with 108 C. albicans cells and under identical estrogen treatment (see also Results). Samples of vaginal fluids (vaginal washes) were taken at regular intervals from each animal after the intravaginal challenge with yeast cells. The rat vaginal cavity was washed by gentle injection and subsequent aspiration of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; 0.5 ml). The collected fluids were pooled for each experimental group; the resultant 2.5 to 3 ml was centrifuged for 15 min at 3,500 × g in a refrigerated Biofuge, and the supernatant was assayed for vaginal Abs or cytokines as described below.

ELISA to detect Abs against C. albicans constituents in vaginal fluids.

The presence of Abs directed against mannan antigens or Sap was assayed in the vaginal washes by a previously described enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) (4). Briefly, 200 μl of a mannan extract (>95% polysaccharide) solution (5 μg/ml in 0.2 M sodium carbonate) was used as coating antigen for the detection of antimannan Ab and was dispensed into the wells of a polystyrene microtitration plate which was kept overnight at 4°C. After three washes with Tween 20-PBS buffer, 1:2 dilutions of supernatants of the vaginal fluids were distributed in triplicate wells, and the plates were incubated for 1 h at room temperature. Each well was washed again with Tween 20-PBS buffer, and predetermined optimal dilutions of alkaline phosphatase-conjugated sheep anti-rat immunoglobulin G (IgG), IgM, or IgA (obtained from Serotec Ltd., Kidlington, Oxford, United Kingdom) were added. Bound alkaline phosphatase was detected by the addition of a solution of p-nitrophenyl phosphate in diethanolamine buffer and the plates were read at A405 with an automated microreader (Labsystem Multiscan; Multiskan, Helsinki, Finland) blanked against air. For anti-Sap Ab detection, the same ELISA was used, except that a highly purified, non-mannan-containing Sap preparation was used as the coating antigen (4). The enzyme preparation was kindly provided by P. A. Sullivan (Palmerston North, New Zealand). A vaginal fluid was considered positive for a determined Ab when the optical density (OD) was greater than two times the value of the well coated with the same antigen and incubated with the Ab-free vaginal fluid of an uninfected rat.

Detection of cytokines in vaginal fluids.

Vaginal fluids were taken from rats at different times during the infection, pooled and centrifuged as described above, and assayed for the presence of cytokines such as interleukin 2 (IL-2), IL-4, IL-5, and IL-12 by a quantitative sandwich enzyme immunoassay technique (Quantikine; R-D Systems, Minneapolis, Minn.). Gamma interferon (IFN-γ) was detected by ELISA (rat IFN-γ; CYTOSCREEN; Biosource International, Camarillo, Calif.).

Briefly, standards, samples (vaginal fluid supernatants), and controls were added to wells precoated with immobilized specific Ab. Each sample consisted of a volume of 100 to 200 μl, depending on the specific cytokine under assay, as indicated by the manufacturer's instructions. After extensive washes, a specific enzyme-linked polyclonal Ab was added to the wells. Finally, after washes, a substrate solution was added, and the colorimetric reaction was terminated by specific stop solution. ODs were read at 450 nm with an automated microreader (Labsystem Multiscan), and the results, expressed as picograms per milliliter, were compared with the values of specific standard curves for each cytokine as instructed by the manufacturer. The ELISA sensitivities were 25, 3, 4.1, 13, and 5 pg/ml for IL-2, IL-5, IL-4, IFN-γ, and IL-12, respectively. Before testing, each cytokine standard was spiked with normal rat vaginal fluid to assay for possible interferences. No such interferences on the standard curves of each cytokine assay were detected.

Collection of VL.

The vagina was aseptically removed from each sacrificed rat; the vaginal tissue was cut longitudinally and minced with a sterile scalpel in complete medium consisting of RPMI 1640 supplemented with penicillin (100 U/ml), streptomycin (100 mg/ml), l-glutamine (2 mM), sodium pyruvate (2 mM), 2-mercaptoethanol (5 × 10−5 M), and 5% heat-inactivated fetal calf serum, all from Life Technology (Paisley, Scotland, United Kingdom), with 25 mM HEPES buffer. Minced tissues were digested in complete medium with sterile 0.25% collagenase D (Boehringer, Mannheim, Germany), following incubation in a shaker at 37°C for 30 min. Before, during, and immediately after the incubation period, samples were mixed in a stomacher homogenizer (Lab Blender 400 PBI). After digestion, tissues and cells were filtered through a sterile gauze mesh, washed with RPMI 1640 medium, and centrifuged three times (200, 800 and 1,800 × g for 15 min each time). Finally, the cells were collected from the supernatant, resuspended in Hanks buffered salt solution, counted, and assessed for viability by trypan blue dye exclusion. About 80% of these cells were vaginal lymphocytes (VL), as judged by morphology in Giemsa-stained smears. Approximately 2 × 105 viable VL were collected from each vagina.

Other cell preparation.

Spleens were aseptically removed from sacrificed rats. Spleen cells were teased, and cellular debris was removed. The cell suspensions were counted and diluted at an appropriate concentration (106/ml) in RPMI 1640 medium (Flow Laboratories, Irvine, United Kingdom) containing 10% heat-inactivated fetal calf serum (Flow), 2 mM l-glutamine (Gibco Laboratories, Grand Island, N.Y.), penicillin (100 IU/ml; Gibco), streptomycin (100 μg/ml; Gibco), and 20 mM HEPES (Gibco) (complete medium) for proliferation assays.

Heparinated venous peripheral blood was withdrawn by cardiac puncture from CO2-anesthetized rats. Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) were isolated by centrifugation on Ficoll-Hypaque (Lymphoprep; Nicamed, Oslo, Norway) gradients, washed twice, counted, and finally resuspended at the appropriate concentration in complete medium for proliferation assays.

Mesenteric, inguinal lymph nodes were collected, and single-cell suspensions were prepared with sterile mesh screen. Lymph node cells (LNC) were treated with Tris-ammonium chloride to lyse erythrocytes, washed twice with Hanks balanced salt solution (Gibco), counted, and resuspended at the appropriate concentration in complete medium for proliferation assays.

PBMC, LNC, and spleen cell viability was assessed by trypan blue exclusion and was routinely greater than 95%. The proliferation assay with all of these cells was performed as described for VL.

Mitogen and antigen stimulants.

Phytohemagglutinin (PHA) was from Difco Laboratories. Mannoprotein (MP-F2) was extracted from the yeast form of C. albicans BP serotype A and prepared for use as an antigenic stimulant as described elsewhere (13, 28, 29).

Vaginal cell proliferation.

VL were suspended in complete RPMI medium supplemented with the antimycotic meparthricine (amphothericin methylester; 50 μg/ml; kindly provided by V. Strippoli, University of Rome “La Sapienza,” Rome, Italy), dispensed into tissue culture-treated plastic 96-well, round-bottomed microtiter plates (Costar, Cambridge, Mass.) at a final concentration of 105 cells/0.1 ml, and cultured in a total volume of 200 μl of culture medium with PHA (1 μg/μl) for 72 h, or MP-F2 (100, 10, or 1 μg/ml) for 6 days, at 37°C under 5% CO2 humified atmosphere. Cell proliferation was evaluated by thymidine incorporation (0.5 μCi of [3H]thymidine {[3H]TdR}; specific activity, 6.7 Ci/mmol; New England Nuclear, Boston, Mass.) during the last 6 h of the culture. Incorporation of [3H]TdR was measured by standard liquid scintillation counting after harvesting the cells with a Skatron (Oslo, Norway) apparatus. All cultures were run in quadruplicate.

Abs.

Phycoerythrin (PE)- and fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated Ab specific for rat CD3 (pan-T), CD4, CD5 (T and a subset of B cells in Wistar rats) (18, 19), CD8a, CD25 (IL-2 receptor α [IL-2 Rα]), α/β T-cell receptor (TCR), and γ/δ TCR were from Pharmingen Corp. (San Diego, Calif.). Mouse FITC-conjugated Abs (Becton Dickinson, Mountain View, Calif.) were used as negative controls.

Immunofluorescence and flow cytometric analysis.

Standard methodology was used for direct single and double immunofluorescence of VL. Briefly, 2 × 105 VL from C. albicans-infected and control rats were resuspended in complete medium, pelleted, and then incubated with the appropriate Ab or negative control for 30 min at 4°C. After three washes with cold PBS, the VL were analyzed for relative fluorescence intensity. For double immunofluorescence, PE- or FITC-conjugated Ab was incubated for an additional 30 min on ice with the respective FITC- or PE-conjugated Ab and similarly washed with cold PBS. The percentage of positive-stained cells determined over 10,000 events was analyzed on FACScan cytofluorimeter (Becton Dickinson). Fluorescence intensity was expressed in arbitrary units on a logarithmic scale. Cells incubated with mouse FITC-IgG1, rat PE-IgG2a, and FITC-isotype control Ab were used to determine the background fluorescence. Compensation for each fluorochrome was determined by parallel single-color analysis of cells labeled with one of the fluorochrome-conjugated Abs.

Histology.

After rats were sacrificed, the vagina was removed and immediately fixed in 10% (vol/vol) neutral buffered formalin. After dehydration in a graded ethanol series and clearing with xylene, the material was embedded in paraffin, and 8-μm-thick sections were stained with hematoxylin-eosin for observation under the light microscope.

RESULTS

Outcome of, and Ab production during, three successive rounds of vaginal infections by C. albicans.

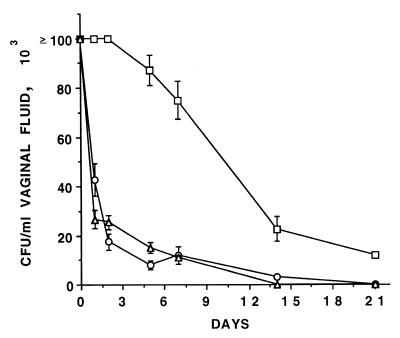

We reassessed the susceptibility of oophorectomized, estradiol-treated rats to vaginal infection and reinfection by C. albicans as well as antimannan and anti-Sap Ab production under the conditions selected for this study, which included an intravaginal inoculum of C. albicans cells higher than that routinely used in this model (3, 4) (see below). Figure 1 shows the kinetics of first, second, and third challenges of C. albicans (each with 188 cells and up to day 21 postinfection). After the first intravaginal challenge on day 0, > 105 Candida CFU/ml of vaginal fluid could be found during the first 3 to 4 days postinfection, and then the Candida vaginal burden slowly declined, approaching the lowest detectable value by our method (103 CFU/ml) on week 4 postinfection. Vaginal smears taken at intervals during infection demonstrated sustained hyphal growth starting 1 day postinfection and extending through day 14. If rechallenged with C. albicans 1 week after resolution of the primary infection (day 35), the reinfected animals cleared the second infection much more rapidly than the first one, as the limit of 103 CFU/ml was approached at the end of the first week of infection and no Candida CFU could be detected by the end of the second week. At this time, a new rechallenge (third infection) again resulted into a very rapid clearance of the infecting fungus, similarly to the kinetics of clearance measured in the second infection (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Outcome of vaginal infection by C. albicans in oophorectomized, estradiol-treated rats after first (□), second (○), and third (▵) infections with 108 C. albicans cells. Each curve represents the mean (± standard error) of the fungal CFU of five rats. All rats of the first challenge were still infected on day 21, when the experiment was stopped, whereas no rats of the second and third challenges were infected at that time. Starting from the first postchallenge CFU measurement (day 1), there was a highly significant difference (P < 0.01, Student's t test) in CFU counts between the first challenge and both of the other two challenges at each specified time.

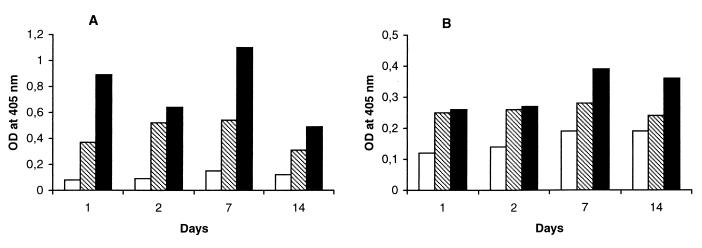

Rat vaginal fluids, harvested at 0, 1, 2, 7, and 14 days postinfection and examined for the presence of antimannan and anti-Sap Abs, showed a clear trend to substantial increase in the titers of both Abs from the first to the second infection. The third infection rapidly boosted both Ab titers, mostly evident on day 7 postinfection. Figure 2 shows antimannan and anti-Sap Abs in the first 2 weeks after each infectious challenge. No such Abs were detected in the vaginal fluids of control, uninfected rats. The results of these experiments extended previous data limited to the second infection and to lower inoculum size (3, 4). They clearly demonstrate (i) the long persistence of anti-Candida resistance at the vaginal level conferred by the resolution of the primary, self-healing infection and (ii) its association with increased vaginal Ab levels against virulence-relevant C. albicans antigens.

FIG. 2.

Antimannan (A) and anti-Sap (B) Abs in rat vaginal fluids during the three infection cycles with C. albicans. A group of five rats was challenged intravaginally, on day 0, with 108 fungal cells for the first infection (empty columns) and then for the second (dashed columns) and third (full columns) infections following resolution of the preceding one (see also Materials and Methods). At the indicated times, vaginal washes were performed, and the Ab against a mannan or a Sap preparation of C. albicans (27) was assessed by ELISA as detailed in Materials and Methods. Values on the ordinate are the OD readings of the ELISA, with mannan or Sap as the coating antigen, and the pool of vaginal washes from each rat, as detailed in Materials and Methods. There was less than 10% variation in the OD readings of the three different wells for each determination.

Cytokines in vaginal fluids.

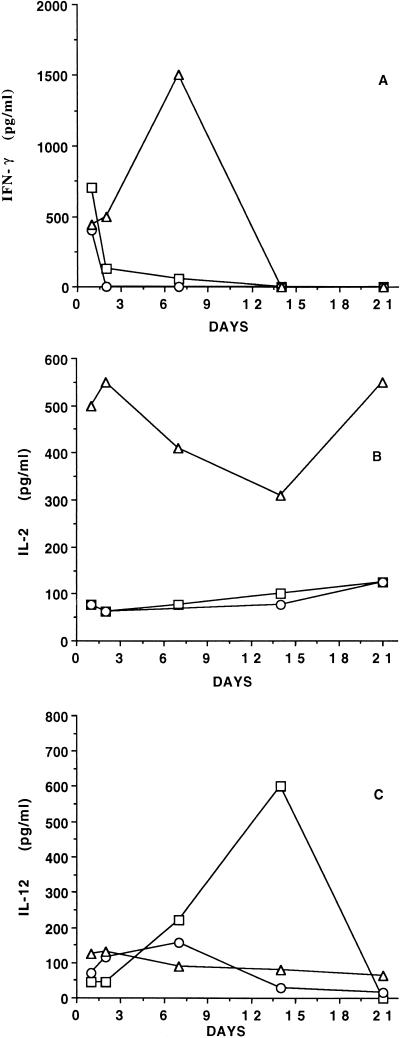

Because of the critical immunoregulatory role of cytokines in the induction and persistence of specific cellular and Ab responses (26), the vaginal fluids from rats taken at intervals during the three infection rounds were evaluated for the presence of cytokines representative of both T helper type 1 (Th1) (IFN-γ and IL-2) and Th2 (IL-4 and IL-5) patterns. IL-12, a Th1-driving cytokine, was also searched for. For both the first and second infections, appreciable amounts of type 1 cytokines were found in the vaginal fluids. This was particularly observed during the first 2 to 3 days (in the case of IFN-γ [Fig. 3A]) and rather constantly during the whole infection round for IL-2 (Fig. 3B). A remarkable increase in their level was detected soon after the third challenge, with peaks of IFN-γ (around 1,500 pg/ml) and IL-2 (around 550 pg/ml) on days 7 and 3, respectively. While the intravaginal level of IFN-γ then declined to undetectable values, IL-2 remained detectable, though with quantitative fluctuations, throughout the infectious period, in both the first and second infectious cycles (Fig. 3A and B). In contrast, much higher levels of IL-12 were measured during the first, immunizing intravaginal infection than in the two subsequent ones, although it remained detectable during each infection round (Fig. 3C).

FIG. 3.

Detection of intravaginal cytokines in vaginal washes during three rounds of C. albicans infection. (A) IFN-γ; (B) IL-2; (C) IL-12. Each cytokine was assayed as detailed in Materials and Methods, using pools of the vaginal washes from each rat (five rats pooled). □, ○, and ▵, first, second, and third infections, respectively.

Type 2 cytokines IL-4 and IL-5 were never detected in the vaginal fluid of Candida-infected rats at any time during the three infection rounds. Similarly, no IL-2, IL-4, or IL-5 was detected in the vaginal fluid of any control rat, but occasional spikes of IFN-γ and IL-12 (never >50 pg/ml) were found in the vaginal fluid of some of these rats.

Vaginal cell populations.

The results above, showing remarkable, infection-associated modulations of cytokines produced by T cells and present in the vaginal fluid, prompted us to evaluate the hypothesis that intravaginal lymphocyte populations could also show modulations during the three subsequent infections. We particularly focused on vaginal T cells because congenital athymia negated induction of protection following the first immunizing Candida infection (4) and also because T cells were previously characterized as dominant lymphocyte populations in a mouse model of vaginal candidiasis (12). To this end, VL isolated from collagenase-digested vaginal tissue on day 7 after each infection round, as well as on the corresponding day of estrogen treatment in uninfected rats, were labeled with FITC-conjugated anti-CD3 antibody and analyzed by flow cytometry. In control rats, CD3+ VL represented about two-thirds of the total viable cells harvested from rat vagina. The CD3− VL were not extensively characterized. However, about 25% of them expressed the CD5 marker, which is present on certain B-lymphocyte subsets in mice and in Wistar rats (18, 19). Background fluorescence, as determined by cellular staining with mouse PE-conjugated IgG1 and FITC-conjugated IgG2B, was negligible and had no effects on VL staining (data not shown). Following dual labeling with FITC- or PE-conjugated anti-CD3 antibodies coupled with PE-conjugated anti-α/β or FITC-conjugated anti-γ/δ TCR Ab, about two-thirds of these CD3+ VL expressed the α/β TCR and the remaining third expressed the γ/δ receptor. Although fluctuating during the three infection rounds, this proportion differed only slightly at the third infection cycle from that measured in the control, estrogenized animals (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Phenotype characterization of VL from three rounds of infection with C. albicansa

| Phenotype | % VL expression in:

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Uninfected rats

|

Estrogenized and infected rats at round:

|

||||

| Control | Estrogenized | 1 | 2 | 3 | |

| CD3+ α/β | 69 | 70 | 48 | 79 | |

| CD3+ γ/δ | 31 | 29 | 52 | 21 | |

| CD4+ | 45 | 33 | 26 | 43 | 46 |

| CD8+ | 55 | 65 | 71 | 57 | 48 |

| CD4+ α/β | 43b | 23 | 17 | 33 | 44 |

| CD8+ α/β | 57b | 74 | 79 | 67 | 48 |

| CD4+ γ/δ | 46b | 55 | 48 | 52 | 53 |

| CD8+ γ/δ | 54b | 45 | 53 | 48 | 47 |

| CD4+ CD25+c | 7 | 11 | 55 | 79 | |

| CD8+ CD25+d | 7 | 13 | 45 | 65 | |

Measured after pooling the VL of 10 rats of each category (control uninfected, nonestrogenized; estrogenized uninfected; estrogenized and infected). The average ratio of CD4+ to CD8+ T cells in the blood of nonestrogenized, uninfected rats was 3 (more or less 10% variation) in three independent determinations. For other details, see Materials and Methods.

Percentage of cells with that marker out of all CD4+ and CD8+ cells.

Percentage of CD25+ cells out of all CD4+ cells.

Percentage of CD25+ cells out of all CD8+ cells.

Much more relevant were the changes in the CD4+/CD8+ ratio associated with estrogen treatment and the three infection rounds, as seen by dual labeling with PE- or FITC-conjugated anti-α/β (or anti-γ/δ) TCR Ab together with either anti-CD4 or anti-CD8 Ab. As shown in Table 1, the CD4/CD8 VL ratio was inverted compared to that of the blood (where the ratio fluctuates around a value of 3:1), as CD8+ cells were more numerous than the CD4+ cells, especially in estrogenized rats after the first infection. However, the proportion of CD4+ T cells showed a clear rising during the other two infection rounds, nearly regaining the ratio (almost 1:1) measured in the control (uninfected and nonestrogenized) rats. Table 1 also shows that the above changes affected almost exclusively the CD4+ and CD8+ cells bearing the α/β TCR, as the number of γ/δ TCR cells remained substantially unchanged. Finally, dual labeling with anti-CD4 (CD8) Abs followed by anti-CD25 Ab showed a very substantial increase of both CD4 and CD8 cells bearing the CD25 activation marker during the three infection rounds. After the third infection, this marker appeared to be expressed by the large majority of the VL (79 and 65% of CD4+ and CD8+ cells, respectively) starting from less than 10% positivity of both cell types in noninfected, estrogenized rats. Of interest is also the increase in the proportion of the CD3− CD5+ cells, which were more than 50% of all CD3− VL on day 7 of the third infection (not shown).

Histology.

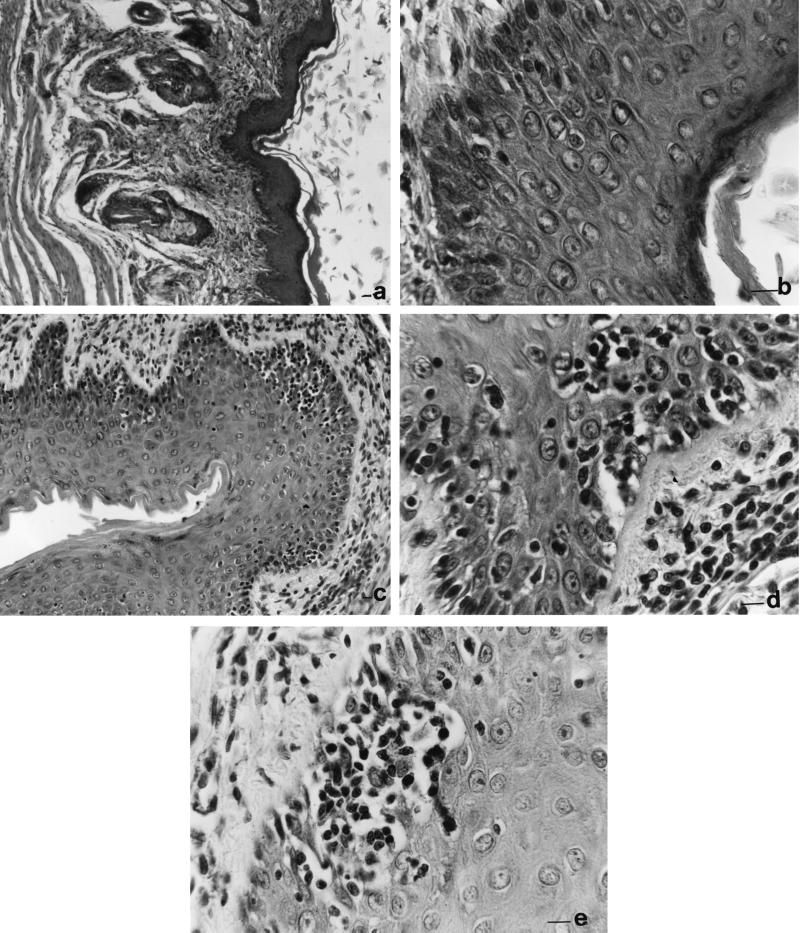

Sections of the vaginal tissue were examined during each infection round for evidence of cell infiltration and other histological changes. No or very few mononuclear cells within the mucosal tissue were detected during the first round of infection either in the vaginal epithelium or in the fiber-rich subepithelial space (Fig. 4a and b). In contrast, starting from the end of the second to the whole third cycle of infection, numerous infiltrating inflammatory (prevalently mononuclear) cells were observed in the subepithelial lamina propria and also infiltrating within the epithelium of the mucosal tissue (Fig. 4c and d). In definite vaginal subepithelial areas, clusters of mononuclear cells were quite prominent (Fig. 4e).

FIG. 4.

Sections of rat vagina taken on day 7 after the first (a and b) and third (c to e) infections by C. albicans. The sections are stained with hematoxylin-eosin. Magnification bars correspond to 2 (a and c) and 10 (b, d, and e) μm.

VL proliferation.

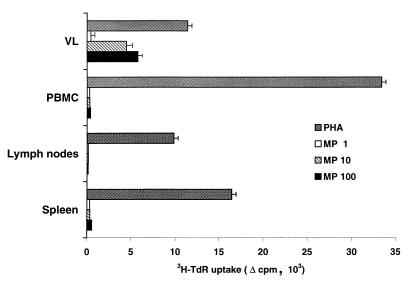

The data reported above, showing remarkable expansion of CD4+ α/β TCR lymphocytes harvested from the vaginas of estrogenized rats during the three infections rounds, also prompted us to examine whether Candida-specific lymphocytes were present among the expanded and activated VL populations. To this end, VL from animals on day 7 of each infection round were cultured and stimulated in vitro with the polyclonal stimulants PHA and concanavalin A, along with a mannoprotein antigen fraction of Candida (MP-F2) which proved to be an immunodominant T-cell antigen in humans and able to promptly detect CMI responses in Candida-immunized mice (21, 29). For comparison, lymphocytes from spleens, lymph nodes, and blood of the same rats were also cultured and stimulated in vitro with mitogen or MP-F2. Mononuclear cell cultures from rats taken during the first and second infection rounds, while promptly responding to PHA or con-A, did not proliferate in response to the Candida antigen. Conversely, vaginal but not blood, lymph node, and spleen lymphocytes from rats taken after the third infection also responded, in a dose-dependent manner, to stimulation with MP-F2 antigen (Fig. 5).

FIG. 5.

Lymphoproliferative responses of VL, PBMC, LNC, and spleen cells to in vitro stimulation with PHA and various concentrations (micrograms per milliliter) of C. albicans mannoprotein antigen (MP), as indicated. A total of 105 cells of each organ were cultured for 6 days in the presence of each stimulant (3 days for PHA stimulation), and their degree of proliferation was assessed by [3H]TdR incorporation as detailed in Materials and Methods. Incorporation is expressed as the difference (▵) between counts per minute of the stimulated culture and those of an unstimulated culture (which were usually less than 300).

DISCUSSION

By extending previous observations by ourselves and others (3, 4, 8), we have demonstrated here that a spontaneously healing, primary Candida infection of rat vagina constitutes a potent inducer of a persistent immunoprotection against repeated challenges with high intravaginal Candida burdens. Protection was associated with the presence of antimannan and anti-Sap Abs, the levels of which were markedly boosted by the repeated challenges, particularly during the first week of the third infection. These Abs were previously shown to confer passive protection in Candida-infected, nonimmunized rats, a protection that could also be conferred by intravaginal administration of monoclonal Abs (IgG and IgM) against mannoside and peptide epitopes of mannan and Sap, respectively (4). Together with other recent data obtained by us (24) and by Han et al. (14, 15), the findings reported here constitute strong evidence that the persistent immunity resulting from the healing of a primary vaginal infection by Candida is eventually mediated by Abs of a definite specificity and probably isotype.

While highlighting the importance of Abs for anticandidal protection, previous studies also suggested a critical role of T cells in the induction of immunity at the vaginal level, as nude (congenitally athymic) rats were unable to mount a protective immunity after healing of the primary infection or active immunization with the protective Candida antigens (3, 4). These latter observations are totally consistent with the impressive, though indirect, clinical evidence regarding the susceptibility of T-cell-deficient subjects to mucosal candidiasis (17, 25) as well as with the findings from studies of normal and genetically modified mice (2, 9, 22, 26).

For these reasons, we addressed here the composition of vaginal T-cell populations, their activation state, and the amount of T-cell-derived cytokines in the vaginal fluid of rats during subsequent challenges following the primary, immunoprotective infection. Also on the basis of previous data by others (10–12), we assumed that if T cells have a role in vaginal immunity and this immunity is so compartmentalized, an obvious (and necessary) consequence is that changes, even only functional, in the regulatory and effector mechanisms of local anticandidal immunity should be manifested on induction of protection. The cellular milieu of the vagina does indeed contain all kinds of effector and accessory cells, such as antigen-presenting cells, and both α/β and γ/δ CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, which are competent for induction and expression of specific adaptive immunity.

Four observations made here give strong support to the above assumption. First, we found that induction of pseudoestrus (a condition for effective vaginal candidiasis in the rat model) substantially influenced the CD4+/CD8+ VL ratio, which fell to 0.25 from about 1 for the control (uninfected and nonestrogenized) rats. Noteworthy, a progressive shift in the ratio of CD4+ to CD8+ α/β vaginal T cells in favor of the CD4+ components occurred with the progressive infection rounds, regaining the value (approximately 1) found in the control rats. Second, most of the CD4+ and CD8+ rat VL increasingly expressed the IL-2 Rα marker on the subsequent infections. Remarkably, no numerical change was induced in the CD4+/CD8+ T cells bearing the γ/δ T-cell receptor. Third, there were progressively increasing amounts of Th1 cytokines in the vaginal fluid of infected rats along with the progression of the infectious cycles. This was particularly evident with IL-2, of which there was a sustained production during the third infection, a finding which is also consistent with CD25 expression and suggests a pronounced T-cell activation in the vagina. Of interest here is that remarkable amounts of the Th1 cytokine pattern-driving IL-12 were also detected during the primary, immunizing infection, while not even traces of the Th2-type cytokines IL-4 and IL-5 were detected. This suggests the induction of a definitely dominant Th1 cytokine pattern in our infection model. Fourth, and probably of greater functional importance, the VL population from the third infection round was shown to contain Candida-specific lymphocytes, capable of intensely proliferating upon recognition of an immunodominant and protective Candida mannoprotein antigen (21, 29). Interestingly, neither lymphocytes from peripheral blood nor those from spleen or lymph nodes responded to this antigen, though they were fully responsive to polyclonal stimulant.

These results provide the first evidence that a Candida-specific cellular response wholly restricted to vaginal level is induced and expressed during a rodent vaginal infection by C. albicans and is associated to a protective anti-Candida state in the vagina. The cytofluorimetric analysis suggests that this immune response may be due to the expansion and activation of vaginal T lymphocytes of CD4+ α/β TCR phenotype. Since neither blood nor lymph node or spleen T cells proliferated upon stimulation by Candida antigen, it would seem unlikely that the vaginal lymphocytes are Candida-sensitized T cells infiltrating the vagina from the periphery. However, it is still possible that the Candida-specific “vaginal” lymphocytes do indeed come from the periphery, being attracted by the potent, local antigenic stimulus constituted by the second and third infectious burdens, and that the number of residual specific T cells in the blood or lymph node is too low for lymphoproliferation in vitro. Our histological pictures suggest a pronounced degree of inflammation occurring at the vaginal level during the second and third Candida infections, with prevalently mononuclear cell components. There are also reports that estrogen treatment favors the transmigration of lymphocytes into the mucosa of the genital tract, although this seems to occur more to the uterus than to the vagina (25). However, the whole picture could be more consistent with in situ activation and multiplication of intra- and subepithelial vaginal lymphocyte populations.

Since the focus of these experiments was on T-cell composition and activation, no detailed analysis of the CD3− cells, which constituted about one-third of the viable vaginal cells in control rats, was performed. Nonetheless, the presence of the CD5 marker in a consistent proportion of these cells suggests that B lymphocytes are also present in the vagina. Besides the T cells, the CD5 determinant does indeed characterize a subpopulation of estrogen-sensitive lymphocytes in Wistar rats (19). Interestingly, CD3− CD5+ cells also significantly increased their relative proportion from the first to the third infection round (9.6 to 20.8% of the vaginal cells). Since other B cells of Wistar rats do not express the CD5 marker (18), the proportion of vaginal B lymphocytes could be still higher. Determination of the true role of CD5+ or CD5− B lymphocytes in the expression of Candida-reactive VL properties such as lymphoproliferation and antibody production awaits more in-depth investigations. These might be particularly revealing inasmuch as the CD5+ murine lymphocytes have been shown to have a restricted VH usage and have been thought to exert a primary role as first-line Ab producers against microbial cell surface antigens (18, 19). These investigations are in progress in our laboratories.

While evidence similar to our own has been obtained in other models of experimental vaginal infection (e.g., with Chlamydia trachomatis [23]), our findings would appear to be somewhat distinct from those obtained by Fidel and collaborators in a murine vaginal infection by Candida. In this model, no numerical changes or activation of specific vaginal T-cell populations during both primary and secondary infections, and no influence of estrogen on these populations, were found (11, 12). In addition, no VL proliferation induced by Candida antigens was shown.

Another important difference is that Candida-specific T cells in the blood were induced by vaginal infections in the murine model, without apparent infiltration of these cells into the vaginal tissue (11).

Nonetheless, the above differences may be related to differential features of the two experimental models. Although both require estrogens for Candida infection, the rat model also requires oophorectomy; more important, the initial composition of vaginal T cells appears to be substantially different, as CD8+ α/β TCR cells are at a level equal to or greater than that of CD4+ cells in the rat vagina, whereas many more cells of the latter phenotype are present in mouse vagina (12). In addition, an influence of estrogen treatment on the CD8+/CD4+ ratio is clear in our model. Interestingly, this ratio seems to be close to that found in the vagina of normal women (5), suggesting that the rat model could, in theory, better reflect the human clinical situation. Finally, VL proliferation in response to Candida antigen stimulation was, in our model, detected only during the third infection round, in animals which were evidently hyperimmunized by the repeated Candida intravaginal challenges. The data reported by Fidel et al. (12) are apparently restricted to the second infection.

The absence of Th2 cytokines coupled with the marked elevation of Th1 cytokine (IFN-γ and IL-2) levels between the second and the third challenges was remarkable. Importantly, it was clearly preceded by the production of high levels of IL-12, a Th1 pattern-driving cytokine, during the primary, immunizing infection. All of these findings demonstrate the induction of a definitely dominant type 1 cytokine pattern in our experimental setting, probably related to the maturation and expansion of a major category of Th1 cytokine-producing cells such as the CD4+ α/β TCR, but also to the marked cellular activation, as demonstrated by the high percentage of CD25 expression noticed in both CD4+ and CD8+ cells. These latter cells are also good producers of IFN-γ and have been reported to express anticandidal activity when activated by IL-2, of which there was high intravaginal production during the third infection (1). Interestingly, the highest intravaginal levels of both IFN-γ and IL-2 persisted after most of the fungal burden was eliminated from the rat vagina. Of interest is also that the highest IFN-γ level in the vaginal fluid was measured on day 7 of the third infection, when the highest Ab levels were also detected (cf. Fig. 2A and B and 3A), suggesting a possible relationship between the two events. Both IFN-γ and IL-2 indeed play a role also in Ab (especially of some isotype) maturation. Besides confirming the importance of a Th1 induction pattern for anticandidal protection (7, 10, 26) as well as suggesting its probable role in protective Ab responses, our findings suggest that the protection at vaginal level is related to the persistence (memory) of a specific, locally restricted immune activated state. Studies of the antigenic specificity and TCR repertoire of vaginal T-cell clones could help us draw a definite conclusion in this matter.

From all of the available evidence, it seems fair to conclude that vaginal T cells undergo remarkable quantitative and qualitative changes during repeated vaginal infections by C. albicans in rats. Candida-specific cellular immunity is achievable and demonstrable on repeated vaginal challenges with the fungus, and this immunity is vaginally restricted and associated with a dominant Th1 cytokine pattern. Although its exact role in anticandidal protection at the vaginal level and its possible relationship with the generation of protective Abs (3, 4) remain to be defined, the presence of Candida-specific VL paves the way for directly addressing the protective potential of these cells by adoptive transfer experiments.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to Angela Santoni for critical reading of the manuscript and providing useful suggestions. The careful assistance of Francesca Girolamo and Anna Botzios in preparation of the manuscript is gratefully acknowledged. Antonietta Girolamo helped in the preparation of vaginal cells.

This work was supported in part by the National AIDS Research Program, under I.S.S. contract 50 C/B.

REFERENCES

- 1.Beno D, Mathews H L. Quantitative measurements of lymphocyte-mediated growth inhibition of Candida albicans. J Immunol Methods. 1993;164:155–164. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(93)90308-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cantorna M T, Balish E. Role of CD4+ lymphocytes in resistance to mucosal candidiasis. Infect Immun. 1991;59:2447–2455. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.7.2447-2455.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cassone A, Boccanera M, Adriani D, Santoni G, De Bernardis F. Rats clearing a vaginal infection by Candida albicans acquire specific, antibody-mediated resistance to vaginal reinfection. Infect Immun. 1995;63:2619–2625. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.7.2619-2624.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.De Bernardis F, Boccanera M, Adriani D, Spreghini E, Santoni G, Cassone A. Protective role of antimannan and anti-aspartyl proteinase antibodies in an experimental model of Candida albicans vaginitis in rats. Infect Immun. 1997;65:3399–3405. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.8.3399-3405.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Elitsur Y, Jackman S, Neace C, Keerthy S, Liu X, Dosescu J, Moshier J A. Human vaginal mucosa immune system: characterization and function. Gen Diagn Pathol. 1998;143:271–277. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fidel P L, Jr, Lynch M E, Sobel J D. Candida-specific cell-mediated immunity is demonstrable in mice with experimental vaginal candidiasis. Infect Immun. 1993;61:1990–1995. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.5.1990-1995.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fidel P L, Jr, Lynch M E, Sobel J D. Candida-specific Th1-type responsiveness in mice with experimental vaginal candidiasis. Infect Immun. 1993;61:4202–4207. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.10.4202-4207.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fidel P L, Jr, Lynch M E, Conaway D H, Tait L, Sobel J D. Mice immunized by primary vaginal Candida albicans infection develop acquired vaginal mucosal immunity. Infect Immun. 1995;63:547–553. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.2.547-553.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fidel P L, Jr, Sobel J D. Immunopathogenesis of recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1996;9:335–348. doi: 10.1128/cmr.9.3.335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fidel P L, Jr, Luo W, Chabain J, Wolf N A, Van Buren E. Use of cellular depletion analysis to examine circulation of immune effector function between the vagina and the periphery. Infect Immun. 1997;65:3939–3943. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.9.3939-3943.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fidel P L, Jr, Ginsburg K A, Cutright J L, Wall N A, Lennan D, Dunlap K, Sobel J D. Vagina-associated immunity in women with recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis: evidence for vaginal Th-1 type responses following intravaginal challenge with Candida antigen. J Infect Dis. 1997;176:728–739. doi: 10.1086/514097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fidel P L, Jr, Luo W, Steele C, Chaban J, Baker M, Wormley F., Jr Analysis of vaginal cell populations during experimental vaginal candidiasis. Infect Immun. 1999;67:3135–3140. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.6.3135-3140.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gomez M J, Torosantucci A, Arancia S, Maras B, Parisi L, Cassone A. Purification and biochemical characterization of a 65-kilodalton mannoprotein (MP65), a main target of anti-Candida cell-mediated immune responses in humans. Infect Immun. 1996;64:2577–2584. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.7.2577-2584.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Han Y, Cutler J E. Antibody response that protects against disseminated candidiasis. Infect Immun. 1995;63:2714–2719. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.7.2714-2719.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Han Y, Morrison R P, Cutler J E. A vaccine and monoclonal antibodies that enhance mouse resistance to Candida albicans vaginal infection. Infect Immun. 1998;66:5771–5776. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.12.5771-5776.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kearsy J A, Stadnyk A W. Isolation and characterization of highly purified rat intestinal intraaepithelial lymphocytes. J Immunol Methods. 1996;194:35–48. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(96)00052-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Klein R S, Harris C A, Butkus Small C, Moll B, Lesser M, Friendland G H. Oral candidiasis in high risk patients as the initial manifestation of the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. N Engl J Med. 1984;311:354–357. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198408093110602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kroese F G M, Butcher E C, Lalor P A, Stall A M, Herzenberg L A. The rat B cell system: the anatomical localization of flow cytometry-defined B cell subpopulations. Eur J Immunol. 1990;20:1527–1534. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830200718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Martin A, Vicente A, Torroba M, Moreno C, Jimènez E, Zapata A G. Increased numbers of CD5+ B cells in the thymus of estradiol benzoate-treated rats. Thymus. 1996;24:111–127. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mathur S, Virella G, Koistinen J, Horger E O, Mahvi A, Fudenberg H H. Humoral immunity in vaginal candidiasis. Infect Immun. 1992;15:287–294. doi: 10.1128/iai.15.1.287-294.1977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mencacci A, Torosantucci A, Spaccapelo R, Romani L, Bistoni F, Cassone A. A mannoprotein constituent of Candida albicans that elicits different level of delayed-type hypersensitivity, cytochine production, and anticandidal protection in mice. Infect Immun. 1994;62:5353–5360. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.12.5353-5360.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mulero-Marchese R, Blank K J, Sieck T G. Genetic basis for protection against experimental vaginal candidiasis by peripheral immunization. J Infect Dis. 1988;178:227–234. doi: 10.1086/515602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Perry L, Feilzer L K, Caldwell H D. Immunity to Chlamidia trachomatis is mediated by T helper 1 cells through IFN-γ-dependent and -independent pathways. J Immunol. 1997;158:3344–3351. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Polonelli L, De Bernardis F, Conti S, Boccanera M, Gerloni M, Morace G, Magliani W, Chezzi C, Cassone A. Idiotypic intravaginal vaccination to protect against Candidal vaginitis by secretory, yeast killer toxin-like anti-idiotypic antibodies. J Immunol. 1994;152:3175–3182. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Prabhala R H, Wira C R. Influence of estrus cycle and estradiol on mitogenic responses of splenic T and B lymphocytes. In: Mestecky J, et al., editors. Advances in mucosal immunology. New York, N.Y: Plenum Press; 1995. pp. 379–381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Romani L. The T cell response against fungal infections. Curr Opin Immunol. 1997;9:484–490. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(97)80099-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sobel J D. Pathogenesis and treatment of recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis. Clin Infect Dis. 1992;14:148–153. doi: 10.1093/clinids/14.supplement_1.s148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Torosantucci A, Bromuro C, Gomez M J, Ausiello C M, Urbani F, Cassone A. Identification of a 65-kDa mannoprotein as a main target of human cell-mediated immune response to Candida albicans. J Infect Dis. 1993;168:427–435. doi: 10.1093/infdis/168.2.427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Torosantucci A, Palma C, Boccanera M, Ausiello C M, Spagnoli G C, Cassone A. Lymphoproliferative and cytotoxic responses of human peripheral blood mononuclear cells to mannoprotein constituents of Candida albicans. J Gen Microbiol. 1990;136:2155–2163. doi: 10.1099/00221287-136-11-2155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]