Abstract

Background

The coronavirus-19 pandemic continues to influence on the hand therapy community. It is important to understand how therapists are currently affected and how things have changed since the onset of the pandemic.

Purpose

Follow-up on a previous survey and investigate the current status of hand therapy practice 10 months into the pandemic.

Study Design

Web-based survey.

Methods

A 38-item survey was electronically delivered to American Society of Hand Therapists members between December 9, 2020 and January 6, 2021. Stress, safety measures, changes in practice patterns and telehealth were focus areas in the survey. Spearman's Rank Correlation Coefficient was used to analyze nonparametric correlations, Chi-Square analysis examined relationships between categorical values and unpaired t-tests were utilized for the comparison of means.

Results

Of the 378 respondents, 85% reported higher stress levels compared to pre-pandemic times. Younger therapists expressed more stress over childcare concerns (rs = 0.38;P = .000) and job security (rs = 0.21; P = .000), while older therapists expressed more stress over eldercare concerns (rs= -.13;P = .018). Descriptively, hours spent on direct clinical care were near prepandemic levels. Telehealth is currently used by 29% of respondents and did not correlate to age or years of practice. Postoperative cases (t(423) = 4.18;P = .0001) and people age 50-64-years (t(423) = 3.01;P = .002) were most frequently seen for in person visits. Nontraumatic, nonoperative cases (t(423) = 4.52;P = .0001) as well as those 65 years and older (t(423) = 3.71; P = .0002) were more likely to be seen via telehealth.

Conclusions

Hand therapists are adapting as reflected by the return to near normal work hours and less utilization of telehealth. Respondents still report higher levels of stress compared to prior to the pandemic, and this stress appears to be multifactorial in nature. Weariness with the precautionary measures such as mask wearing, social distancing and sanitizing was expressed through open-ended responses.

Keywords: Stress, COVID-19, Personal protective equipment, Telehealth, Hand therapy

Introduction

It has been a grueling and, in some cases, devastating ten months since the World Health Organization (WHO) officially characterized the spread of novel coronavirus 19 (COVID-19) as a global pandemic in March of 2020.1 The ruthless nature of this novel virus has been unleashed across the globe and at the writing of this survey the world surpassed 100 million known virus cases.2

It is well identified that healthcare workers suffer both physical and psychological effects from the impact of the COVID-19 virus.3, 4, 5, 6 One systematic review and meta-analysis identified high rates of depression, anxiety, and insomnia among healthcare providers.7 Similarly, another systematic review reported that the fear of working with infected people in the absence of proper personal protective equipment (PPE) and subsequent spread to families were strongly associated with anxiety in health care workers.8 While front line workers and emergency personnel have been most notably impacted, the profound effects COVID-19 has had on the healthcare community reaches far beyond these limits to other allied health professions 9 , 10, including the profession of hand therapy. 11 , 12 It was for this reason our first survey, “The impact of COVID-19 on hand therapy practice” 11 was developed and administered in April, 2020. In this initial survey, participants reported the abandonment of paraffin units and other modalities and the embracing of PPE; digital thermometers became commonplace, and human touch was eclipsed by telehealth. Hand therapists struggled to understand their role as they juggled unknown variables both at work and home. Lives were upended with new norms of mask wearing, social distancing and staggering amounts of sanitizing. Children were home and learning virtually; therapists were scrambling to understand and deliver services via virtual platforms for the first time while others were furloughed and the fear of contracting COVID-19 was looming in everyone's lives. 11

However, since waging the war against this novel and gradually mutating virus and since our initial survey11 some variables have changed. Therefore, the purpose of this follow-up survey was to capture the essence of hand therapy practice approximately ten months into the pandemic. We sought to gain a greater insight into what effects COVID-19 continues to have on the personal and professional lives of our members and secondarily to understand how perspectives and circumstances may or may not have changed compared to our initial survey.

Methods

Survey development & design

The current survey is a follow-up survey to the initial survey which is referred to throughout this manuscript as the April 2020 initial COVID-19 survey.11 The current survey is referred to as the December 2020 follow-up COVID-19 survey. The December 2020 follow-up COVID-19 survey utilized most of the questions from the April 2020 initial COVID-19 survey.11 However, a few of the questions were reviewed and removed by the authors as they were either no longer needed or were found confusing in nature based on responses from the initial survey. The December 2020 follow-up COVID-19 survey was peer reviewed by members of the research division for the American Society of Hand Therapists (ASHT).

The current 38-item survey explored the personal and professional impact COVID-19 has had on hand therapists as well as provided insight into what factors may be influencing the responses. The “Checklist for Reporting Results of Internet E-Surveys” (CHERRIES) was consulted and followed for appropriate structure.13 The survey design included demographic and multiple-choice questions and some allowed for free text responses through open-ended questions. The questions were based on four constructs to explore the impact of COVID-19 (stress, safety measures, practice patterns, telehealth).

Following peer review the survey and consent forms were submitted and received Institutional Review Board approval. The copy of the survey can be found in Appendix A.

Survey administration

Similar to the April 2020 initial COVID-19 survey,11 the follow-up survey was a web-based survey distributed through Qualtrics (Qualtrics, Salt Lake City, Utah) to active members of ASHT with an email address on file. To maximize the response rate an invitation to participate was sent on two separate occasions. The initial electronic distribution occurred on December 9, 2020 and a reminder email was sent on December 21, 2020. The survey closed on January 6, 2021 and was open for 28 days. The survey was voluntary, no direct benefit was offered for survey completion, and it could only be completed one time per respondent. The survey was configured to maintain anonymity with identifying information (email address, IP address and names) collected and stored by the survey website in a password protected database. The survey was distributed before the mass rollout of vaccinations in the United States (US) began.

Data analysis

Raw data were extracted from Qualtrics and downloaded into Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS version 26) and Microsoft Excel. Descriptive statistics, frequencies, and percentages were calculated using Microsoft Excel. Quantitative data were analyzed using SPSS. Unpaired t-tests were utilized to compare means. Relationships between categorical values were analyzed using Chi-Square, and nonparametric correlations were analyzed using Spearman's Rank Correlation Coefficient. Inferential statistics were considered significant at .05 level.

Descriptive data between the April 2020 initial COVID-19 survey raw data and the December 2020 follow-up COVID-19 raw data were compared to provide a visual depiction of changes between the two surveys.

The open-ended responses were read, and based on similar thoughts and reflections, were placed into groups. From these groups, three definitive categories arose. Quotes from respondents were incorporated to highlight the thoughts that captured the essence of each category. This survey research did not utilize qualitative methodology. There were no interviews, focus groups or observations, and specific themes or codes were not identified.

Results

Demographic data

Two separate emails were sent to members of ASHT. On December 9, 2020, the survey was sent to 3,564 members and opened by 1,413 recipients. On December 21, 2020, the reminder email was sent to 3,572 members and opened by 1,328 recipients. A total 378 members responded to the survey. Not all 378 respondents completed 100% of the survey. The number of respondents factored into each analysis is listed in the text, graphs, and charts. The average age of participants was 48.61 (range 25-71) and the average years licensed as either an occupational or physical therapist was 22.93 (range 0-49). A total of 314 respondents (83%) were certified hand therapists through the Hand Therapy Certification Commission. Table 1 represents demographic data and Table 2 represents the state distribution of respondents.

Table 1.

Demographics

| N | Responses | Frequency (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Profession | 395 | Occupational Therapist | 355(90) |

| Occupational Therapy Assistant | 1(.25) | ||

| Physical Therapist | 22(6) | ||

| Other* | 17(4) | ||

| Do you practice in the US | 377 | Yes | 370(98) |

| No | 7(2) | ||

| Practice setting | 366 | Outpatient-Hospital Based | 142(39) |

| Outpatient-Therapist Owned | 85(23) | ||

| Outpatient-Physician Owned | 70(19) | ||

| Outpatient- Corporate Owned | 44(12) | ||

| Outpatient - Academic Medical Center | 12(3) | ||

| Other | 13(4) | ||

| Practice setting location | 350 | Urban | 107(31) |

| Suburban | 187(53) | ||

| Rural | 53(15) | ||

| Other | 3(1) | ||

| Position | 367 | Staff Therapist | 164(45) |

| Senior Therapist | 62(17) | ||

| Clinical Specialist | 55(15) | ||

| Clinical Supervisor or Specialist | 32(9) | ||

| Practice Owner | 34(9) | ||

| Other | 20(6) |

Most of other included CHTs 16/17

Table 2.

Represents distribution of respondent by state (some respondents reported working in more than one state)

| State | Respondents |

Respondents |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Percentage | Number | Percentage | Number | ||

| Alabama | 0.00% | 0 | Montana | 0.53% | 2 |

| Alaska | 0.53% | 2 | Nebraska | 0.53% | 2 |

| Arizona | 4.49% | 17 | Nevada | 0.53% | 2 |

| Arkansas | 0.00% | 0 | New Hampshire | 0.00% | 0 |

| California | 12.14% | 46 | New Jersey | 3.96% | 15 |

| Colorado | 3.96% | 15 | New Mexico | 1.06% | 4 |

| Connecticut | 1.58% | 6 | New York | 5.80% | 22 |

| Delaware | 0.53% | 2 | North Carolina | 1.32% | 5 |

| District of Columbia | 0.53% | 2 | North Dakota | 0.00% | 0 |

| Florida | 3.43% | 13 | Ohio | 1.85% | 7 |

| Georgia | 2.37% | 9 | Oklahoma | 0.26% | 1 |

| Hawaii | 0.26% | 1 | Oregon | 4.49% | 17 |

| Idaho | 0.53% | 2 | Pennsylvania | 4.22% | 16 |

| Illinois | 3.43% | 13 | Puerto Rico | 0.00% | 0 |

| Indiana | 0.79% | 3 | Rhode Island | 0.26% | 1 |

| Iowa | 0.79% | 3 | South Carolina | 0.79% | 3 |

| Kansas | 0.79% | 3 | South Dakota | 0.53% | 2 |

| Kentucky | 0.53% | 2 | Tennessee | 1.32% | 5 |

| Louisiana | 0.79% | 3 | Texas | 3.17% | 12 |

| Maine | 1.58% | 6 | Utah | 1.06% | 4 |

| Maryland | 3.17% | 12 | Vermont | 1.32% | 5 |

| Massachusetts | 2.64% | 10 | Virginia | 4.49% | 17 |

| Michigan | 3.17% | 12 | Washington | 3.60% | 14 |

| Minnesota | 3.43% | 13 | West Virginia | 0.53% | 2 |

| Mississippi | 1.58% | 6 | Wisconsin | 2.37% | 9 |

| Missouri | 2.64% | 10 | Wyoming | .26% | 1 |

Quantitative analysis

Stress

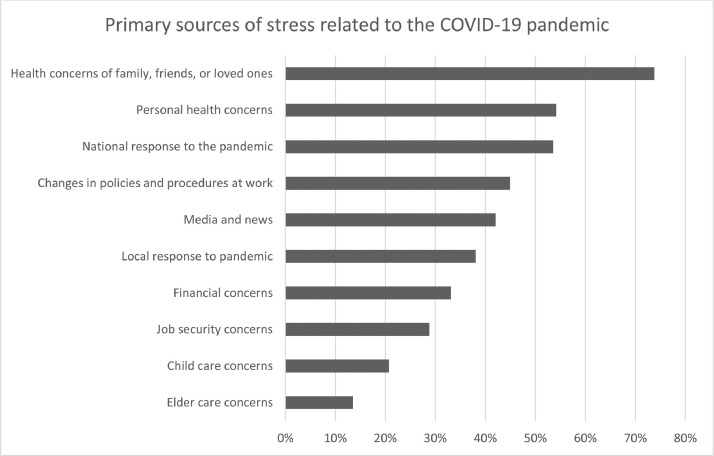

Most respondents reported feeling more stress than they did prior to the COVID-19 pandemic (85%; 296/347). Overall stress data were analyzed against age and were found to be nonsignificant. However, when sources of stress were compared to age, weak to moderate statistically significant correlations were found with three variables. Younger therapists were more likely to have childcare concerns (rs = 0.38; P = .000), older therapists were more likely to have elder care concerns (rs = -.13; P = .018), and younger therapists were more likely to have job security concerns (rs= .21; P = .000). Refer to Table 3 for all significant correlation coefficients. Refer to Figure 1 for reported sources of stress as it relates to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Table 3.

Correlation coefficients

| Correlation coefficient | Significance* | |

|---|---|---|

| Age and stress related to childcare concerns | 0.38 | <0.001 |

| Age and stress related to elder care concerns | -0.13 | 0.018 |

| Age and stress related to job security | 0.21 | .000 |

significant at .05 level.

Fig. 1.

Respondents reported source of stress related to COVID-19 pandemic.

N = 347; multiple answers allowed.

Stress data were also analyzed against practice owner vs nonpractice owner, practice setting (urban/rural/suburban), and financial impact and no statistical significance was found with any of these variables and stress.

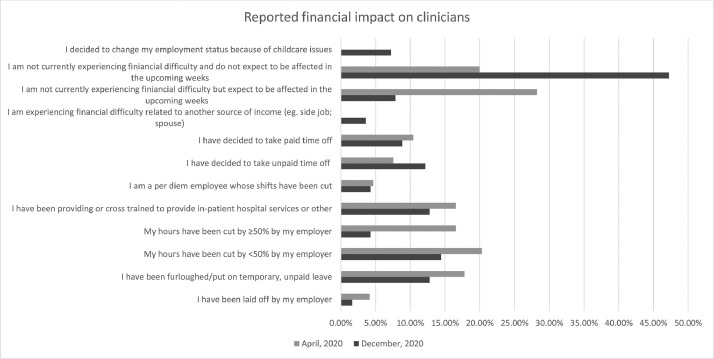

Financial impact data were descriptively compared between the April 2020 initial COVID-19 survey and December 2020 follow-up COVID-19 survey. In December 2020, almost 50% of respondents reported they were not experiencing financial difficulty and did not expect to be in the upcoming weeks compared to 20% of respondents in April, 2020. See Figure 2 .

Fig. 2.

Reported financial impact on clinicians comparing April, 2020 initial COVID-19 survey and December, 2020 follow-up COVID-19 survey data.

n = 556 (April, 2020 survey); n = 305 (December, 2020 survey); multiple answers allowed.

*Childcare question was not asked in the April 2020 survey.

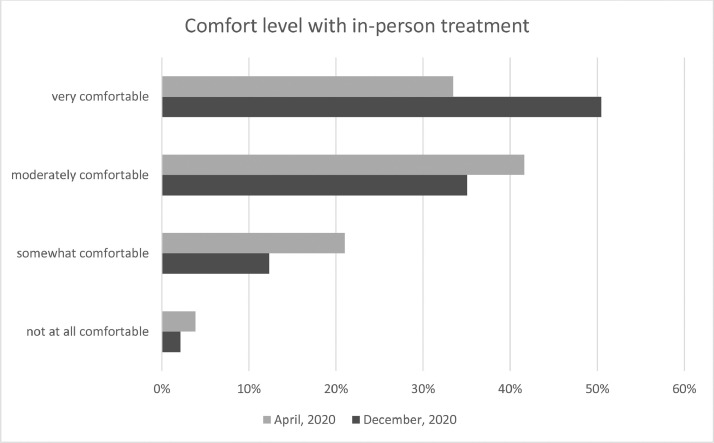

Safety measures

Most respondents reported utilizing some form of PPE when treating patients in-person. A total of 90% of respondents wear surgical masks, 47% wear gloves, and 35% use goggles and/or face shields. Descriptively, overall comfort level with in-person treatment increased in the December 2020 follow-up COVID-19 survey data compared to the April 2020 initial COVID-19 survey data. Refer to Figure 3 for these comparisons. There were no statistical differences between comfort with in-person treatment and age or years in practice.

Fig. 3.

Comfort level with in-person treatment between April, 2020 initial COVID-19 survey and December, 2020 follow-up COVID-19 survey data.

April 2020 (n = 490); December 2020 (n = 325).

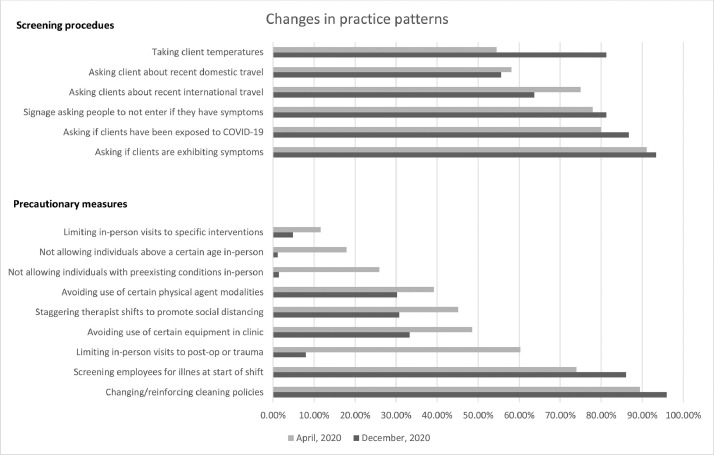

Safety measures in terms of screening procedures and precautionary measures were also descriptively compared between the April 2020 initial COVID-19 survey and the December 2020 follow-up COVID-19 survey. Refer to Figure 4 for these comparisons.

Fig. 4.

Percentage of respondent answers regarding safety changes in practice patterns between April, 2020 initial COVID-19 survey and December, 2020 follow-up COVID-19 survey data.

Screening n = 580 (April, 2020 survey); n = 347 (December, 2020 survey); multiple answers allowed.

Precautionary n = 587 (April, 2020 survey); n = 351 (December, 2020 survey); multiple answers allowed.

Practice patterns

Hours in direct clinical care were descriptively compared between the April 2020 initial COVID-19 survey and the December 2020 follow-up COVID-19 survey and demonstrate an almost return to pre-COVID-19 numbers. Refer to Figure 5 for these comparisons.

Fig. 5.

Percentage of respondent reporting hours per week engaged in direct clinical care; comparison between April, 2020 initial COVID-19 survey and December, 2020 follow-up COVID-19 survey data.

Post-operative cases were more likely to receive in-person treatment (t(423) = 4.18, P = .0001) and nontraumatic, nonoperative cases were more likely to receive telehealth services (t(423) = 4.52, P = .0001). Patients ages 50-64 were more likely to receive in-person treatment (t(423) = 3.01, P = .002) whereas patients 65 or over were more likely to receive telehealth services (t(423) = 3.71, P = .0002). Refer to Figure 6

Fig. 6.

Percentage of telehealth versus in-person caseload broken out by age and type of caseload

Type of case: Nontraumatic, nonoperative cases t(423) = 4.52, P= .0001; Trauma, nonoperative cases t(423) = 0.17, P = .86;. Postoperative cases t(423) = 4.18, P = .0001

Age: 65 and older t(423) = 3.71, P= .0002; 50-64 t(423) = 3.01, P= .002; 19-49 t(423) = 1.60, P = .11; 0-18 t(423) = 0.41, P = .65

Telehealth

A total of 29% (100/347) of respondents reported still utilizing telehealth services compared to 46% (305/659) in April, 2020. Descriptively, the differences in reported telehealth use from the April 2020 COVID-19 initial survey and the December 2020 follow-up COVID-19 survey can be viewed in Figure 7 .

Fig. 7.

Comparing percentage of therapists reported utilizing telehealth before pandemic and recent use; April, 2020 initial COVID-19 survey and December, 2020 follow-up COVID-19 survey data.

Utilization of telehealth before COVID-19 (yes n = 28; no n = 266) (April, 2020 survey); Utilization of telehealth in past 2-weeks (yes n = 305; no n = 354) (April, 2020 survey).

Utilization of telehealth before COVID-19 (yes n = 16; no n = 83) (December, 2020 survey); Utilization of telehealth in past month (yes n = 100; no n = 247) (December, 2020 survey).

Telehealth services were more likely to still be utilized in urban settings compared to suburban or rural settings ((X2 (2, N = 326) = 11.8524, =p.003). Refer to Figure 8 . There were no differences between the utilization of telehealth services and outpatient academic medical, outpatient corporate owned, outpatient hospital, outpatient physician owned, or outpatient therapist owned. There were no relationships between age or years of practice and the utilization of telehealth.

Fig. 8.

Percentage of therapists utilizing telehealth based on urban, suburban, or rural location.

*Significant (X2 (2, N = 326) =11.8524, =p.003).

Findings from open ended questions

The survey had six questions that allowed members to offer reflections and free text responses. After disseminating and reading through all responses three main categories were identified which included, Precautionary Measures, Telehealth, and the Future of Hand Therapy. Refer to Appendix B for a summary of responses for each question.

Precautionary measures

This category was by far the most prevalent and emerged as a response in all six of the open-ended questions. The responses made clear that mask wearing, social distancing and cleaning are in the forefront of therapists’ minds. Although respondents continue to find safety measures important, there was a sense of fatigue with ongoing precautionary measures not only from the physical aspect of wearing PPE but also from a perspective of time and cost. The following capture the tone of many of the responses, “it is hard to communicate with patients through the mask,” “cleaning supplies are not cheap,” “it is more costly and time-intensive,” as well as “it is stressful, due to all of the precautions.” Many respondents recognize that the current precautionary measures may be a long-term commitment. Some of the comments included, “I am tired of masks and cleaning,” “social distancing is hard in hand therapy practice” and “will most likely need to use precautions forever.”

Two open ended questions asked specifically about the use of equipment in the clinic and physical agent modalities. Respondents reported that they have not used desensitization bins, shared therapeutic putty, fluidotherapy or paraffin wax since the onset of COVID 19. Others have resumed use of these interventions, but with modified methods such as having the patient wear long gloves in fluidotherapy and under hot packs and/or cold packs or not directly dipping into the paraffin wax.

Telehealth

The word telehealth was mentioned in several of the open-ended responses. Interestingly, some members reported that telehealth was incorporated at the outset of pandemic; however, is not currently utilized in their practice setting. Statements included “no need we have returned to in person tx” and “we did telehealth in early covid months of shutdown,” “no need,” or “found not as effective,” and “I did provide telehealth early in the pandemic and found it less satisfying.” There were also statements indicating that it was difficult to be efficient in the clinic while providing both telehealth and clinical care such as “I have so many patients in the clinic there is not time for telehealth.” Ironically, when asked about the future of hand therapy, telehealth was also a consistent response. Some respondents had favorable impressions of telehealth and the future, making comments such as “I hope that the pandemic will enable more telehealth services and reimbursement long term!” and another “on a positive note, we are all definitely considering telehealth as an option now.” However, not all responses were favorable with their thoughts as it relates to telehealth and the future, making comments such as “unsure, but am not wanting to participate in telehealth and fear that will be wave of future,” “telehealth is NOT good for treating post op fractures, Burns, etc,” and “ I can't make an orthosis using Telehealth,” and “I don't think any therapy can be effective if provided via telehealth.”

Future of hand therapy

The summation of this category revolved around the tangible, more physical aspects of COVID-19, with keywords including PPE, cleaning/sanitizing, social distancing, and telehealth. Many of the reflections focused on the concepts of COVID-19 guidelines recommended by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) for safety and stopping the spread. While some members embraced the change, others simply accepted, and still others had a less optimistic lens looking toward the future. Thoughts from this question were expressed as, “hopefully increase awareness of cleaning procedures,” “we are all more careful, sanitation has improved, with social distancing,” “this will be temporary and will change with the vaccine,” “the days of multiple clients at a semi-circle table are over”, “I see social distancing and gloves continuing even after pandemic is over,” “possibly more telehealth in the future if covered by insurance” and “hopefully this will signal a permanent change in reimbursement of and improved technology for telehealth, which has been immensely beneficial for many of our patients.”

Some comments reflected on the unknown and a sense of hope as articulated by these statements, “I have no idea what the future holds. I deal with the new normal and keep moving,” “I / we are “holding on” and HOPING all things will greatly improve by March 2021,” and summed up optimistically with “hand therapy will survive.”

Discussion

The hand therapy community has battled through the COVID 19 pandemic along with other healthcare professionals, upending practice patterns and creating external stressors, the likes of which we have not seen before. At the time of this survey distribution in December 2020, the US was on pace to experience the deadliest month from COVID-19 since its onset,14 , 15 and the world had surpassed 100 million known virus cases.2 Despite the heightened concern, greater morbidity and mortality rates, and a mutating virus,16 our survey responses revealed an overall sense of things slowly returning to normal from a practice perspective. Most therapists have increased their number of work hours and do not expect to be facing financial difficulty in the upcoming weeks, there are more in-person visits and people are not restricted from these visits due to age or pre-existing conditions, people feel more comfortable with in-person visits, and telehealth use has decreased compared to the original survey in April 2020.

This apparent return to pre-COVID times may indicate people are adapting with increased comfort levels for screening procedures, use of PPE and social distancing. Another factor may be that more is understood about the virus and effective treatments that are now available.17 At the time of the survey, the vaccine rollout had not really started and therapists had not been vaccinated, so that does not explain this slow return to normal. It is interesting to note that when the initial survey was distributed in April, 2020, the COVID-19 cases and deaths were not nearly at the levels as they are today, and many states were experiencing little to no cases. However, during that time frame in-person treatment was largely suspended, and work hours were drastically reduced.11 This follow-up survey depicts how in-person practice is slowly returning to normal levels despite the fact that COVID-19 is very much present and still impacting daily life.

Another practice trend that appears to be returning to pre-pandemic levels is telehealth. The use of telehealth among respondents jumped to 46% in April, 2020,11 but has decreased in December, 2020 to 29% as more clients are being treated in-person. Prior to COVID-19 the reported utilization of telehealth was quite low, between 5% and10%.11 The overwhelming majority of free text responses regarding telehealth was that it was no longer necessary with return to in person treatment, and that its efficiency, effectiveness, and reimbursement were questionable. With the rapid rise to telehealth visits at the beginning of the pandemic and systems not yet in place to appropriately triage patients, it is understandable that some therapists would feel more efficient and productive with in person visits. This notion of efficiency is also expressed qualitatively by physicians.18 , 19 Telehealth is often most successful when there is a genuine need within the community for telehealth services, it is in the best interest of the client and their care,20 and there is an infrastructure that includes, funding, technology, technical support, consultation, and training.21 Health care practitioners may improve the effectiveness and acceptance of telehealth as they develop clearer guidelines for determining suitable cases for telehealth visits by taking into account visit types, patient characteristics and diagnoses. 18 , 22 There are multiple studies that provide guidance on how to maintain quality of care18 , 19 and/or connectedness20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25 over the telehealth platform.

In addition to the infrastructure, for telehealth to be considered a sustainable health delivery system there must be acceptance of telehealth by both patients and providers. A study recently found that for patients in Brazil, their attitude toward telemedicine was the most explanatory variable in predicting their intention to use telemedicine.26 In the current study, the two most chosen responses as to why hand therapists were not providing telehealth services were (1) that clients no longer wanted to receive telehealth services; and (2) that clients had not requested telehealth services. Therefore, it is plausible that a lack of acceptance of telehealth by the patient may be one of the many driving forces as to why telehealth services have decreased.

Although client factors play a large part in the delivery of telehealth, the hand therapists’ attitude towards telehealth is also a factor. In our survey, the third most chosen response as to why hand therapists were not providing telehealth was that they felt they could not provide quality care using this platform. Evidence supports that perceived usefulness is a predictor to positive intentions to use telerehabilitation.27 Dahl-Popolizio et al. examined the effectiveness of OT services during the COVID-19 pandemic, and reported that OTs felt that conditions of the hand and upper extremity could effectively be treated via telehealth and that therapeutic exercise and home programs could be delivered with telehealth.28 Currently, the evidence related to efficacy of telehealth in hand rehabilitation as it relates to certain conditions or treatment approaches is lacking. In both the April 2020 survey 11and in this survey, post-operative patients were significantly seen more in person than via telehealth. This signals that both the hand therapists and patients felt in person treatment was important after surgery despite the risk of COVID-19.

According to the survey, those more likely to still be receiving telehealth services are people 65 years and older and people with nontraumatic, nonoperative cases. Although there is a general assumption that people over age 65 may not be as comfortable with technology, perhaps they were most likely to use telehealth because during the pandemic they were included in the higher risk group for contracting COVID-19. We also found that therapists more likely to still be using telehealth were those in urban areas compared to suburban or rural areas. This was an unexpected finding given that the CDC saw similar or more cases and deaths in nonmetropolitan areas compared to metropolitan areas during the timeframe this survey was open.29 No other literature has described differences in usage of hand therapy telehealth in urban, suburban, and rural areas. There is literature indicating that rural Americans see COVID-19 as less of a threat to personal and public health when compared to urban and suburban Americans with urban Americans feeling the most threat of COVID-19 to personal and public health.30 Therefore it is plausible that individuals in rural areas may not feel that attending hand therapy in person is a threat to their personal health and therefore are not requesting telehealth services.

There were some interesting differences between the April 2020 initial survey and the December 2020 follow-up survey as it relates to practice patterns. Respondents in this recent survey reported an increased use in taking client temperatures as part of screening procedures, although there is little evidence to support the use of digital noncontact thermometers. The majority of infra-red thermometers have been found with low sensitivity and perform outside the accuracy range for body temperature as established by the International Temperature Scale of 1990 (ITS-90).31 Similarly, temperature taking is found questionable due to the incubations period, undetectable symptoms as well as training of the individuals operating the thermometer as to where the device is placed on the forehead or temple and distance of the thermometer to the skin.31 , 32 Also, many respondents in this survey have not returned to using shared equipment or modalities; treatment tools that people perceive cannot be easily cleaned or sanitized between patients. The authors did not find published evidence that supports or refutes the use of physical agent modalities during the pandemic.

Most participants reported increased levels of stress compared to before the COVID-19 pandemic. This is similar to other authors who report an overall increase in psychological distress among the general population,33, 34, 35, 36 regardless of whether or not people worked in healthcare or in an occupation that placed people at greater risk for contracting COVID-19.37 , 38 Despite what appears to be a plethora of evidence indicating an overall increase in stress levels as a result of the pandemic, the literature appears mixed related to variables that contribute to this overall increased stress. Higher levels of psychological distress during the COVID-19 pandemic have been reported among women,33 , 34 , 38, 39, 40, 41 migrant workers,33 college age students,34 , 39, 40, 41 people with less education,38 healthcare workers with less medical training,41 people who are lonely,39 , 40 and people who were unemployed .38 Some report higher stress levels in people that have poor health, 34 or pre-existing mental health conditions,38 while others state pre-existing general medical conditions do not correlate with increased stress.38 In our study, we found that older therapists experienced more stress related to eldercare concerns. We also found that younger therapists experienced more stress related to childcare concerns and job security concerns. Similarly, Taylor & Landry38 also found small, negative correlations related to age and income levels and COVID-19 stress indicating that younger individuals do feel stress associated with the pandemic.

Since our original survey much has been written about women and mothers and stress and the unique effect it has had on them. 33 , 42 , 43 Women make up approximately 80% of the healthcare workforce according to the Bureau of Labor and Statistics,44 and this percentage is even greater in the membership of the ASHT (85% female; 15% male). (Luci Patalano MBA, email communication, February 2021). In a European survey it was found that 66.5% of women had to stop working during the pandemic to assist with changes in childcare due to shutdown45 and when having to choose which parent stays home, the burden of care taking and childcare tends to fall on the woman.46 These changes were found to impact the women's sleep quality and emotional symptoms including sadness and frustration.46 There is speculation that these additional changes in the home life may contribute to the higher stress levels in women during the pandemic.40 , 41 Although we did not ask about sleep quality or emotional symptoms, we had similar findings from a statistical perspective, as childcare and eldercare were two variables that contributed to increased stress among our respondents, most of whom were women.

Although not statistically significant, free text from open-ended questions revealed that private practice owners expressed additional and unique stressors. For private practice owners the obvious reasons had to do with sustainability due to decreased volume and reimbursement. However, some less obvious stressors included navigating and securing the Paycheck Protection Program (PPP loan) application and the unexpected cost of cleaning supplies and PPE. The stress found in our survey is brought to light in a recent Gallup poll which reported that female business owners have a daily worry and stress level of 62% compared 38% prior to the onset of COVID 19.47 Likewise when comparing women to their male counterparts, 31% of women report their mental health has worsened during the pandemic versus only 20% for men.48

The increased stress reported by many during these times appears to be a multi-factorial issue. Some of the top stressors reported in the literature include fear of getting COVID-19 or bringing it home to family,38 , 49 , 50 overall fatigue from long hours and shifts among healthcare workers,49 changes in family responsibilities, 49 , 51 lack of job security and economic consequences,38 , 49 , 51 and the US election.49 In this current survey, the open-ended statements illuminate the vast breadth of stress experienced. Answers varied from obvious and somewhat expected answers such as fear of sickness and exhaustion from juggling children suddenly home and learning on-line, to less obvious stressors such as the political environment in the US, the lack of vacation time, an inability to travel, and the fatigue of constantly wearing a mask and cleaning. Some of these free texts statements provide valuable insight into some of the more obscure stressors that may impact people during a pandemic, highlighting the fact that stress experienced during these times may have many facets, people may not be seeking necessary help to deal with the stress,38 , 50 and the lasting impacts of this multifactorial stress are unknown at this time 36 , 38

An interesting and unexpected finding was the mention of the political climate and increased stress associated with it. At no point in the survey were politics mentioned, although question 43 did offer “national response to the pandemic” as a choice when asking about other sources of stress related to COVID-19. Stress over the national response to the pandemic was the third highest response rate. In the open responses, people reported that increased stress came from the current political landscape in the US. Statements such as “the political landscape has been rough!,” and “this needs to stop being wielded for political gain.” Frustration with political ignorance and a feeling of misinformation were mentioned in the open-ended question related to stress. This indicates that regardless of political views, the political tension in the US52 contributed to overall increased stress reported by therapists during this timeframe.

Limitations

There were several limitations to the study. We had a lower response rate with our follow-up survey compared to our initial survey. Our first email did not indicate that the survey was a follow up survey causing confusion that it was the same as the initial survey. Although the survey was distributed to all ASHT members, only a small percentage of therapists answered the survey, so the results may not be a true representation of the greater hand therapy community. Additionally, often times people who complete a survey are the ones who continue to be concerned about a topic, thus it is possible that people who were naturally more stressed about the pandemic completed the survey, which could have entered bias into our data.

Conclusion

Despite the fact that the US and the world are experiencing a rise in COVID-19 cases, hospitalizations, and virus mutations, our December, 2020 follow-up survey demonstrates a slow return to normal in the field of hand therapy. Therapists are feeling more comfortable with in-person treatment, there is a decrease in telehealth, in-person caseloads are near pre-COVID-19 levels, and fewer therapists are reporting “fear” or “worry” in free text responses. However, it is important to note that despite what appears to be a slow return to normal, therapists that responded to our survey are still experiencing overall stress and the variables associated with this stress appear to be multifactorial in nature.

Future research

Future research to better understand variables associated with this increased stress is of value so that appropriate resources can be directed to assist therapists in decreasing stress levels. Future research examining the long-term impact of this stress is also of value so people understand if unique but stressful situations have a lasting impact on people's health and well-being. Additionally, future research examining the effectiveness of telehealth in hand rehabilitation is warranted. It is of interest to understand the effectiveness of telehealth from a hand therapy patient perspective, especially from those patients who received both telehealth and in person treatment. Finally, future research should examine differences in outcomes between patients with similar diagnosis who receive telehealth and those who receive in person treatment. Although it is clear that some interventions such as manual therapy are not able to be delivered over telehealth it would be important to understand what interventions can be effectively delivered via telehealth.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: The authors have no competing interests or conflict of interests.

Study Design: Web based survey.

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.jht.2021.07.001.

JHT Read for Credit

Quiz: # 934

Record your answers on the Return Answer Form found on the tear-out coupon at the back of this issue or to complete online and use a credit card, go to JHTReadforCredit.com. There is only one best answer for each question.

-

# 1.The following received the survey

-

a.CHTs

-

b.AOTA members

-

c.ASHT members

-

d.IFSHT members

-

a.

-

# 2.Correlations were determined by use of

-

a.Spearman's coefficient

-

b.Pearson's coefficient

-

c.an ICC

-

d.a KAPPA

-

a.

-

# 3.The use of telehealth was found to be

-

a.frustrating to a majority of therapists

-

b.less than before the pandemic

-

c.more than before the pandemic

-

d.similar to before the pandemic

-

a.

-

# 4.Therapists appear to

-

a.have contracted COVID at a greater incidence than the population at large

-

b.have a preference to the telehealth model of practice over face-to-face therapy

-

c.be weary of precautions such as masking and social distancing

-

d.have accepted the continued use of masking and social distancing

-

a.

-

# 5.Hours spent on direct clinical care were similar to pre-pandemic levels

-

a.no

-

b.yes

-

a.

When submitting to the HTCC for re-certification, please batch your JHT RFC certificates in groups of 3 or more to get full credit.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

References

- 1.World Health Organization . World Health Organization; 2021. Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Situation Report- 51. Weekly Epidemiological Update and Weekly Operational Update.https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/situation-reports Accessed January 26. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fausset R. Idaho Statesman; 2021. The World Reaches a Staggering Milestone of More Than 100 Million Known Virus Cases.https://www.idahostatesman.com/news/nation-world/article248781630.html Published January 26, 2021. Accessed January 26. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sim MR. The COVID-19 pandemic: major risks to healthcare and other workers on the front line. Occup Environ Med. 2020;77(5):281–282. doi: 10.1136/oemed-2020-106567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bohlken J, Schömig F, Lemke R, Pumberger M, Riedel-Heller S. [COVID-19 pandemic: stress experience of healthcare workers - a short current review] Psychiatr Prax. 2020;47(4):190–197. doi: 10.1055/a-1159-5551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rangachari P, L.Woods J. Preserving organizational resilience, patient safety, and staff retention during COVID-19 requires a holistic consideration of the psychological safety of healthcare workers. IJERPH. 2020;17(12):4267. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17124267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Santarone K, McKenney M, Elkbuli A. Preserving mental health and resilience in frontline healthcare workers during COVID-19. The Am J Emerg Med. 2020;38(7):1530–1531. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2020.04.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pappa S, Ntella V, Giannakas T, Giannakoulis VG, Papoutsi E, Katsaounou P. Prevalence of depression, anxiety, and insomnia among healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Brain, Behav, and Immunity. 2020;88:901–907. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.05.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sheraton M, Deo N, Dutt T, Surani S, Hall-Flavin D, Kashyap R. Psychological effects of the COVID 19 pandemic on healthcare workers globally: a systematic review. Psychiatry Res. 2020;292 doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.American Occupational Therapy Association. COVID 19 and Occupational Therapy: How Does Your Experience Compare to National Trends?; 2020. Accessed January 26, 2021. https://www.aota.org/Practice/Health-Wellness/COVID19/Coronavirus-Survey-Results.aspx

- 10.Tenforde AS, Borgstrom H, Polich G, et al. Outpatient physical, occupational, and speech therapy synchronous telemedicine: a survey study of patient satisfaction with virtual visits during the COVID-19 pandemic. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2020;99(11):977–981. doi: 10.1097/PHM.0000000000001571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ivy CC, Doerrer S, Naughton N, Priganc V. The impact of COVID-19 on hand therapy practice. J Hand Therapy. 2021 doi: 10.1016/j.jht.2021.01.007. Published online FebruaryS0894113021000260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.MacDermid JC. Hand therapy and responding to change in a pandemic. J Hand Therapy. 2020;33(3):271. doi: 10.1016/j.jht.2020.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Eysenbach G. Improving the quality of web surveys: the Checklist for Reporting Results of Internet E-Surveys (CHERRIES) J Med Internet Res. 2004;6(3):e34. doi: 10.2196/jmir.6.3.e34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Feur W. Covid pandemic's deadliest month yet in U.S. Dec. 18, 2020. Published December 18, 2020. Accessed January 31, 2021. https://www.cnbc.com/2020/12/18/december-is-shaping-up-to-be-the-covid-pandemics-deadliest-month-yet-in-the-us.html

- 15.Hall D. U.S. Covid-19 hospitalizations top 125,000 for the first time. Published online December 31, 2020. Accessed January 24, 2021. http://www.wsj.com

- 16.Centers for Diesease Control and Prevention. About variants of the virus that causes COVID-19. Published February 12, 2021. Accessed February 16, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/transmission/variant.html

- 17.Livingston EH. Necessity of 2 doses of the Pfizer and moderna COVID-19 vaccines. JAMA. 2021 doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.1375. Published online February 3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Reeves JJ, Ayers JW, Longhurst CA. Telehealth in the COVID-19 era: a balancing act to avoid harm. J Med Internet Res. 2021;23(2):e24785. doi: 10.2196/24785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Saliba-Gustafsson EA, Miller-Kuhlmann R, Kling SMR, et al. Rapid implementation of video visits in neurology during COVID-19: mixed methods evaluation. J Med Internet Res. 2020;22(12):e24328. doi: 10.2196/24328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.WCPT/INPTRA. Report of the WCPT/INPTRA Digital Physical Therapy Practice Task Force.; 2019. Accessed February 13, 2021. http://www.inptra.org/portals/0/pdfs/ReportOfTheWCPTINPTRA_DigitalPhysicalTherapyPractice_TaskForce.pdf

- 21.Gifford V, Niles B, Rivkin I, Koverola C, Polaha J. Continuing education training focused on the development of behavioral telehealth competencies in behavioral healthcare providers. Rural Remote Health. 2012;12:2108. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zulman DM, Verghese A. Virtual care, telemedicine visits, and real connection in the era of COVID-19: unforeseen opportunity in the face of adversity. JAMA. 2021;325(5):437. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.27304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bergman D, Bethell C, Gombojav N, Hassink S, Stange KC. Physical distancing with social connectedness. Ann Fam Med. 2020;18(3):272–277. doi: 10.1370/afm.2538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kaplan B. Access, equity, and neutral space: telehealth beyond the pandemic. Ann Fam Med. 2021;19(1):75–78. doi: 10.1370/afm.2633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wade VA, Eliott JA, Hiller JE. Clinician acceptance is the key factor for sustainable telehealth services. Qual Health Res. 2014;24(5):682–694. doi: 10.1177/1049732314528809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ramírez-Rivas C, Alfaro-Pérez J, Ramírez-Correa P, Mariano-Melo A. Predicting telemedicine adoption: an empirical study on the moderating effect of plasticity in brazilian patients. J INFORM SYSTEMS ENG. 2021;6(1):em0135. doi: 10.29333/jisem/9618. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Almojaibel AA, Munk N, Goodfellow LT, et al. Health care practitioners’ determinants of telerehabilitation acceptance. Int J Telerehab. 2020;12(1):43–50. doi: 10.5195/ijt.2020.6308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dahl-Popolizio S, Carpenter H, Coronado M, Popolizio NJ, Swanson C. Telehealth for the provision of occupational therapy: reflections on experiences during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Int J Telerehabilitation. 2020;12(2):77–92. doi: 10.5195/ijt.2020.6328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Trends in COVID-19 Cases and Deaths in the United States, by County-Level Population Factors.; 2020. Accessed February 15, 2021. https://covid.cdc.gov/covid-data-tracker/#pop-factors_7daynewcases

- 30.ICF. Rural Americans Feel Less Threatened by Covid-19 than Urban and Suburban Americans Do, but Still View Mitigation as Important; 2020. Accessed February 14, 2021. https://www.icf.com/insights/health/covid-19-survey-rural-vs-urban-threat

- 31.Aw J. The non-contact handheld cutaneous infra-red thermometer for fever screening during the COVID-19 global emergency. J Hospital Infection. 2020;104(4):451. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2020.02.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gostic K, Gomez AC, Mummah RO, Kucharski AJ, Lloyd-Smith JO. Estimated effectiveness of symptom and risk screening to prevent the spread of COVID-19. eLife. 2020;9:e55570. doi: 10.7554/eLife.55570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Qiu J, Shen B, Zhao M, Wang Z, Xie B, Xu Y. A nationwide survey of psychological distress among Chinese people in the COVID-19 epidemic: implications and policy recommendations. Gen Psych. 2020;33(2) doi: 10.1136/gpsych-2020-100213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang C, Pan R, Wan X, et al. Immediate psychological responses and associated factors during the initial stage of the 2019 Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) epidemic among the general population in China. IJERPH. 2020;17(5):1729. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17051729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhang J, Lu H, Zeng H, et al. The differential psychological distress of populations affected by the COVID-19 pandemic. Brain, Behav, and Immunity. 2020;87:49–50. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.04.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cooke JE, Eirich R, Racine N, Madigan S. Prevalence of posttraumatic and general psychological stress during COVID-19: a rapid review and meta-analysis. Psychiatry Res. 2020;292 doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Taylor S, Landry CA, Paluszek MM, Fergus TA, McKay D, Asmundson GJG. Development and initial validation of the COVID Stress Scales. J Anxiety Disorders. 2020;72 doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2020.102232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Taylor S, Landry CA, Paluszek MM, Fergus TA, McKay D, Asmundson GJG. COVID stress syndrome: concept, structure, and correlates. Depression and Anxiety. 2020;37(8):706–714. doi: 10.1002/da.23071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.González-Sanguino C, Ausín B, Castellanos MA, Saiz J, Muñoz M. Mental health consequences of the Covid-19 outbreak in Spain. A longitudinal study of the alarm situation and return to the new normality. Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacol and Biol Psych. 2021;107 doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2020.110219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.González-Sanguino C, Ausín B, Castellanos MÁ, et al. Mental Health Consequences of the Coronavirus 2020 Pandemic (COVID-19) in Spain. A Longitudinal Study. Front Psychiatry. 2020;11 doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.565474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.d'Ettorre G, Ceccarelli G, Santinelli L, et al. Post-traumatic stress symptoms in healthcare workers dealing with the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review. IJERPH. 2021;18(2):601. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18020601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mattioli AV, Sciomer S, Maffei S, Gallina S. Lifestyle and stress management in women during COVID-19 pandemic: impact on cardiovascular risk burden. Am J Lifestyle Med. 2020 doi: 10.1177/1559827620981014. Published online December 10155982762098101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Women, Caregiving, and COVID-19.; 2020. Accessed February 12, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/women/caregivers-covid-19/index.html

- 44.Cheeseman Day (last), J, Christnacht C. Women Hold 76% of All Health Care Jobs, Gaining in Higher-Paying Occupations. Bureau of Labor Statistics; 2019. Accessed February 14, 2021. https://www.census.gov/library/stories/2019/08/your-health-care-in-womens-hands.html

- 45.Di Giorgio E, Di Riso D, Mioni G, Cellini N. The interplay between mothers’ and children behavioral and psychological factors during COVID-19: an Italian study. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s00787-020-01631-3. Published online August 31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Miyamoto I. Daniel K. Inouye Asia-Pacific Center for Security Studies; 2020. COVID-19 Healthcare Workers: 70% Are Women.https://www.jstor.org/stable/resrep24863?seq=1#metadata_info_tab_contents 2020. Accessed February 7, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Badal SB, Robison J. Gallup; 2020. Stress and Worry Rise for Small-Business Owners, Particularly Women.https://www.gallup.com/workplace/311333/stress-worry-rise-small-business-owners-particularly-women.aspx Accessed December 7, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gowdy SC. COVID-19 stress has greater impact on women than men, UH study finds. Published online October 6, 2020. Accessed February 12, 2021. https://www.chron.com/coronavirus/article/COVID-19-stress-has-greater-impact-on-women-than-15624811.php

- 49.Brusie C.Survey of Healthcare Workers Reveals High Levels of Burnout, Stress, & Thoughts of Leaving Their Jobs. berxi; 2020. Accessed January 31, 2021. https://www.berxi.com/resources/articles/state-of-healthcare-workers-survey/

- 50.Coto J, Restrepo A, Cejas I, Prentiss S. The impact of COVID-19 on allied health professions. Frey R, ed. PLoS ONE. 2020;15(10) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0241328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Park CL, Russell BS, Fendrich M, Finkelstein-Fox L, Hutchison M, Becker J. Americans’ COVID-19 stress, coping, and adherence to CDC guidelines. J GEN INTERN MED. 2020;35(8):2296–2303. doi: 10.1007/s11606-020-05898-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Dimock M, Wike R.America Is Exceptional in the Nature of Its Political Divide.; 2020. Accessed February 16, 2021. https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2020/11/13/america-is-exceptional-in-the-nature-of-its-political-divide/

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.