Abstract

This paper documents some of the first estimates of changes in experienced food insecurity associated with the coronavirus pandemic in a low-income country. It combines nationally representative pre-pandemic household survey data with follow-up phone survey data from Mali and examines sub-national variation in the intensity of pandemic-related disruptions between urban and rural areas. Although rural households are more likely to experience food insecurity prior to the pandemic, we find that food insecurity increased more in urban areas than in rural areas. Just three months after the onset of the pandemic, the rural–urban gap in experienced food insecurity completely vanished. These findings highlight that understanding effect heterogeneity is critically important to effectively designing and targeting post-pandemic humanitarian assistance.

Keywords: COVID-19, Pandemic, Food Security, Mali, Sub-Saharan Africa

1. Introduction

The second United Nations Sustainable Development Goal calls for ending hunger and achieving food security for all people by 2030. Achieving this goal within the next ten years is now challenged by dramatic shocks to earned income, household expenditures, and agricultural value chains due to the coronavirus pandemic. Recent estimates suggest that the economic impact of the pandemic in Sub-Saharan Africa specifically could be between a five and seven percent reduction in GDP (Djiofack et al., 2020). Of course GDP is only instrumentally valuable and how the pandemic influences other micro-level outcomes—such as food security—remains largely unknown. Although predictions based on expected changes to income, prices, and food supply estimate that the coronavirus pandemic will dramatically increase the number of people suffering from food insecurity and undernutrition in low-income countries (Baqueano et al., 2020, FAO, 2020), these predictions have yet to be evaluated with actual data measuring experienced food insecurity.

In this paper we estimate changes in experienced food insecurity associated with the coronavirus pandemic in Mali. We combine nationally representative data collected between October 2018 and July 2019 with follow-up phone survey data collected between May and June 2020. The panel nature of these data allows us to control for important time-invariant household-level heterogeneity by including household fixed effects in our regression specifications. This is important because the effects of the pandemic may depend critically on geographic and household characteristics, such as existing vulnerabilities to income shocks (Amjath-Babu et al., 2020, Bene, 2020, Devereux et al., 2020). These features allow us to both estimate nationally representative changes while also accounting for time-invariant differences between households and explore sub-national changes in food insecurity between rural and urban areas. The results of this study are important for the context of Mali and also may inform policy in other relatively poor countries with relatively high rates of food insecurity.

The coronavirus pandemic threatens food security in a number of ways. On the demand side, the pandemic has reduced earned income, increased poverty, and reduced household expenditures (Chetty et al., 2020, Valensisi, 2020). On the supply side, the pandemic is particularly disruptive to post-farm agricultural value chains—such as wholesale and processing logistics enterprises (Reardon et al., 2020). In the context of Mali, the coronavirus pandemic surged in March, in the midst of the off-season period of the agricultural cycle, thereby provoking minimal disruptions to crop production activities in rural areas.1 Meanwhile, economic activities in urban areas were affected by both government policies aiming to slow the spread of the virus and individual behavior motivated by fear of contracting the virus. These details, coupled with the biological dynamics of COVID-19 that spreads via close human contact, suggest that pandemic-related disruptions are likely more dramatic in Mali’s urban and rural peri-urban areas than in remote rural areas.2

We estimate changes in food insecurity associated with the coronavirus pandemic, not the more specific relationship between contracting the SARS CoV-2 (e.g., “COVID-19”) virus and food security. This is an important point for the interpretation of our estimates. Our empirical strategy investigates sub-national heterogeneity in pandemic-related disruptions between urban and rural areas in Mali. Specifically, we investigate sub-national heterogeneity in changes in food insecurity associated with the coronavirus pandemic in Mali between urban and rural areas using a difference-in-difference regression specification. This strategy is similar to that employed by Ravindran and Shah (2020) who exploit sub-national heterogeneity in pandemic-related disruptions to estimate the effect of the pandemic on domestic violence in India. Our results do not rely on COVID-19 tests accurately identifying the true rate of infection in Mali.

Our paper is related to emerging work on the consequences of the coronavirus pandemic. Much of the existing research focuses on labor market outcomes in high-income countries (Adams-Prassl et al., 2020, Alon et al., 2020, Barrero et al., 2020, Bartik et al., 2020, Bui et al., 2020, Chetty et al., 2020, Coibion et al., 2020, Cowan, 2020). A smaller set of studies focuses on low- and middle-income countries and we aim to add to this literature (Aggarwal et al., 2020, Amare et al., 2020, Arndt et al., 2020, Djiofack et al., 2020, Ceballos et al., 2020, Gerard et al., 2020, Jain et al., 2020, Josephson et al., 2020, Kerr and Thornton, 2020, Mahmud and Riley, 2020, Valensisi, 2020). To the best of our knowledge, Amare et al. (2020) is the only other paper that estimates changes in food insecurity associated with the coronavirus pandemic using actual data measuring food insecurity in a nationally representative sample. Other complementary analyses of sub-national populations by Mahmud and Riley (2020) and Ceballos et al. (2020) document a dramatic decrease in food expenditures in rural Uganda and food security in two Indian states, respectively. Adding important nuance, Aggarwal et al. (2020) find that although the coronavirus pandemic led to severe disruptions in market activity and large declines in income among market vendors in rural areas of both Liberia and Malawi, they find no short-run effect on food security. Other researchers and analysts have raised serious concerns about the disruption of food systems (Reardon et al., 2020) and food security (Arndt et al., 2020, Mishra and Rampal, 2020, Narayanan and Saha, 2020, FAO, 2020) but do not quantify the extent nor the effects of the disruption. Finally, existing predictions using expected changes to income, prices, and food supply support this serious concern for food security in low- and middle-income countries (Baqueano et al., 2020, FAO, 2020). Although these predictions provide valuable insight, they ultimately rely on expected changes rather than micro-level data measuring actual changes in experienced food insecurity.

Our primary contribution is describing changes in food insecurity associated with the coronavirus pandemic in Mali. We do this in two ways. First, we provide self-reported descriptive evidence of how respondents themselves perceive that the coronavirus pandemic has influenced their food security. These results suggest the pandemic is associated with dramatic changes in food insecurity. For example, 50 percent of households report being worried that they will not have enough food to eat. Of those households, 65 percent identify the coronavirus pandemic as the most important cause of their food security worries. Moreover, despite higher incidence of food insecurity experience in rural areas, we find that respondents in urban areas more frequently identify the pandemic as the most important cause of their food security challenges. These self-reported descriptive results motivate a more sophisticated estimation approach to quantify changes in food insecurity associated with the pandemic.

Second, we document some of the first estimates of changes in food insecurity associated with the coronavirus pandemic in a low-income country with a nationally representative sample. We find that the pandemic is associated with a dramatic increase in food insecurity felt almost entirely by urban households. Specifically households in urban areas experience an 8 percentage point increase—a 33 percent increase—in our primary measure of experienced food insecurity, relative to households in rural areas, associated with the pandemic. Moreover, prior to the onset of the pandemic, 24 percent of households in rural compared to 16 percent of urban households experienced food insecurity. Therefore, our results highlight that the rural–urban gap in experienced food insecurity completely vanished from before the pandemic through June 2020.

Given the limitations of our empirical strategy, primarily due to the widespread disruption of the pandemic, we are careful to point out that these results are merely descriptive. The presence of a host of confounding omitted variables limit a rigorous assessment of the sign and magnitude of the potential bias on the specific causal effect. Despite this, we estimate economically meaningful changes in food insecurity that are substantially larger than existing predictions (Baqueano et al., 2020, FAO, 2020). This further highlights the critical importance of understanding effect heterogeneity. Our results are important for understanding both the welfare loss due to the pandemic and, more specifically, the challenges of achieving the Sustainable Development Goals after the global spread of COVID-19 (Hoy and Sumner, 2020, Ravallion, 2020).

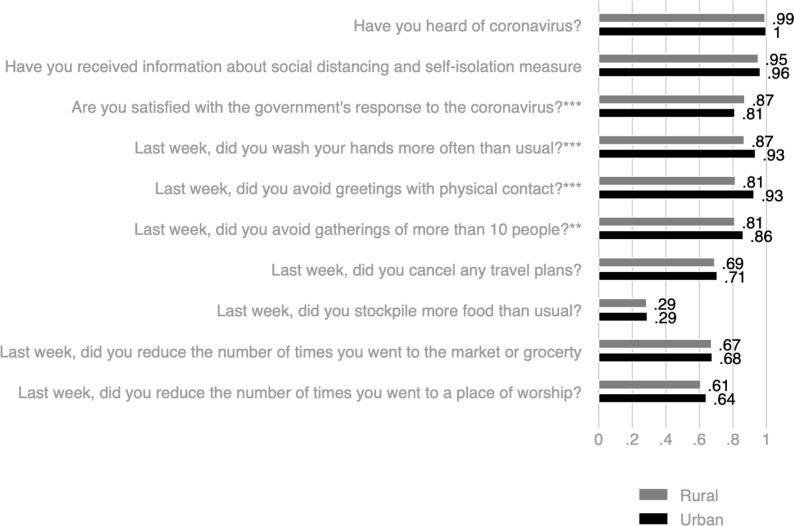

Finally, we discuss and provide some suggestive descriptive insights on the potential mechanisms driving these results. Although we do not have access to data with sub-national variation in food prices for this analysis, we do have some information on recent behaviors and experiences of household members in the context of the coronavirus pandemic. We find that households in urban areas are more likely to take health-related safety precautions (e.g., wash hands more often, avoid greetings with physical contact, and avoid gatherings of more than 10 people), and report struggles to pay rent, access water or electricity, save money, and make investments in durable goods than households in rural areas. Despite this, we find no difference between urban and rural households in food-related behavior (e.g., stockpiling food, frequency of visits to food markets or grocery stores, or self-reported struggle to buy food). This suggests that reductions in food-related shopping behavior at the extensive margin do not fully explain our main effect estimates. However, relative price effects may still influence behavior at the intensive margin.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. The next section summarizes Mali’s experience with the coronavirus pandemic. Section 3 discusses the data we use for our empirical analysis. Section 4 describes the empirical framework and estimation methodology. Section 5 discusses the main results along with a discussion of possible mechanisms and robustness checks. Finally, Section 6 concludes with a discussion of priorities for future work.

2. The coronavirus pandemic in Mali

On March 11, 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) officially categorized the COVID-19 outbreak as a pandemic with consequences potentially reaching every country in the world. On March 18, as preventative measures, Mali suspended all flights traveling from affected countries to Mali, closed all public schools, and banned large public gatherings.3 On March 25 Mali confirmed its first two positive COVID-19 infections. The next day, upon two additional positive COVID-19 infections, Mali’s then President Ibrahim Boubacar Keita declared a state of emergency and implemented a curfew from 9 pm to 5 am in hopes of limiting the spread of the virus. Just two days later, on March 28 and after an additional 14 positive cases, Mali witnessed its first COVID-19 related death (WHO, 2020). The Oxford COVID-19 government’s response tracker (Hale et al., 2020) suggests that Mali’s government, in order to control the spread of the virus, imposed restrictions as stringent as in North American and Western European countries (see Fig. A1 in the Supplemental Appendix).

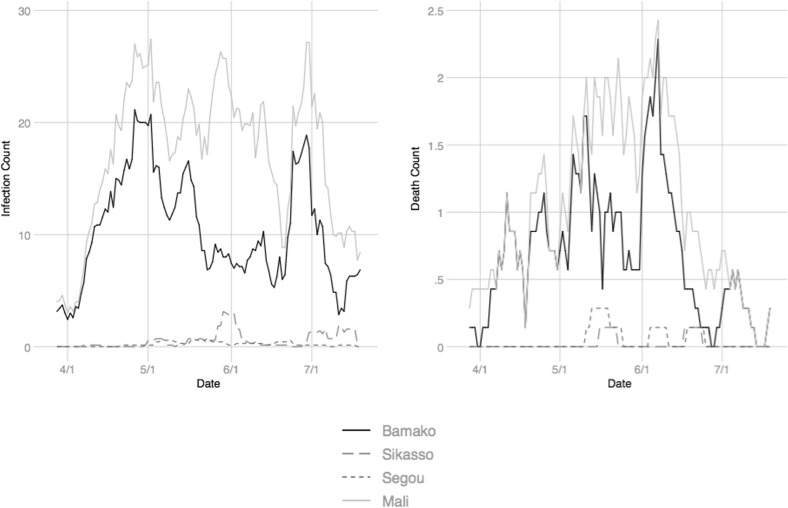

Fig. 1 shows a seven-day moving average of new daily COVID-19 infection and death counts in Mali, as well as in three of the largest urban centers—Bamako, Sikasso, and Segou—from April through July 2020.4 These data are collected by the United Nations’ Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) and made available via the Humanitarian Data Exchange (HDE, 2020). Fig. 1 highlights three important details about the coronavirus pandemic in Mali. First, through about the middle of April 2020, almost all recorded COVID-19 infections and all recorded COVID-19 deaths occurred in Bamako. It was not until the middle of May when the trends in both recorded infections and deaths diverged between Mali and Bamako. Second, other relatively large urban centers—Sikasso and Segou—did not experience anything close to the number of recorded COVID-19 infections or deaths as recorded in Bamako. Aside from a small and short-lived increase in recorded infections in Sikasso at the beginning of June, recorded infections and deaths in Sikasso and Segou remained relatively flat from April through July 2020. Finally, the worst of the pandemic for Mali may be in the past, assuming of course no future wave of COVID-19 infections. By the end of July 2020, daily infection counts were more than half of their peak in previous months and some days have zero recorded COVID-19 deaths.5

Fig. 1.

COVID-19 Infections and Deaths. Notes: These figures come from the Humanitarian Data Exchange (HDX) COVID-19 sub-national case data, supported by the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs. They show the 7-day moving average of new daily COVID-19 infections and deaths for Mali and the three most populous urban areas: Bamako, Sikasso, and Segou.

Using several different data sources, we observe that pandemic-related disruptions were—at least initially—more intense in Bamako and surrounding urban areas than in remote rural areas of Mali. First, as shown in Fig. 1 and discussed above, using data on recorded COVID-19 infection and death counts we observe that both of these indicators are dramatically skewed toward Bamako. Although these recorded infections and deaths likely underestimate the true incidence of infections and deaths, particularly outside Bamako (UNICEF, 2020), they are indicators that influence containment policy efforts and motivate fear among individuals of contracting the virus in Bamako specifically.

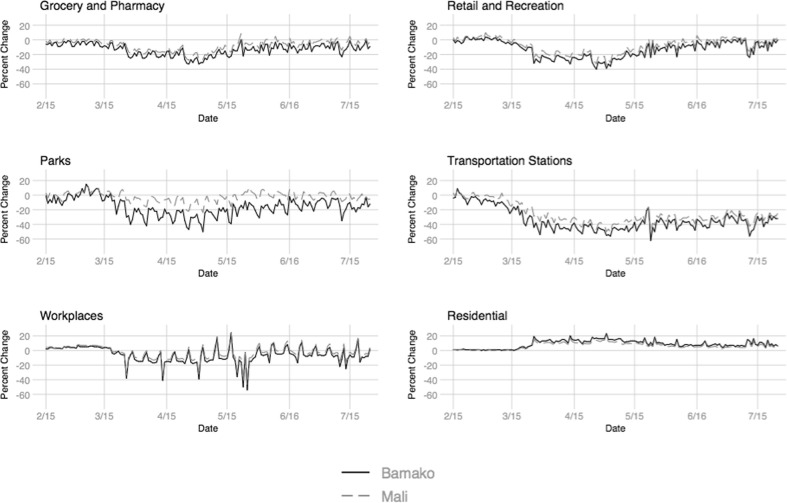

We now turn to Google’s Community Mobility Reports, our second source of information on the intensity of pandemic-related disruptions in Mali. For the purpose of contributing to an understanding of the consequences of the coronavirus pandemic, Google released anonymized and aggregated data from users who have turned on the location history setting of their Google account. These same data are used by Google Maps to predict real-time congestion. The Google Community Mobility Reports show daily changes in the amount of time spent at different places within a given geographic area. These data capture daily percent changes from February 15 through July 15 relative to a baseline representing the median value for the corresponding day of the week during the five-week period from January 3 through February 6, 2020.6 A couple of notes about these data help contextualize their interpretation. First, the Google Community Mobility data are not representative of the whole country. Google only reports on regions if they have a sufficient number of observations over time to make credible estimates of mobility. Thus, these data exist for the entire country of Mali and for Bamako specifically. No other regions within Mali are reported in Google’s Community Mobility Reports. Second, Google data only rely on individuals who use Google applications and have turned on the location history setting in their Google account.

Fig. 2 displays the Google Community Mobility data for both the entire country of Mali and for Bamako specifically. Google aggregates locations into six types of places: Grocery and Pharmacy, Retail and Recreation, Parks, Transportation Stations, Workplaces, and Residential. Overall, in the available Google Community Mobility data for the entire country of Mali, we observe a decrease in time spent at all of these locations, except for places of residence, where we see a relatively small increase. This suggests that either the government containment policies or the risk of contracting the virus disrupted movement and economic activities in Mali.

Fig. 2.

Google Mobility Data. Notes: These figures come from Google’s COVID-19 Community Mobility Data. With the same kind of aggregated and anonymized data used in Google Maps, these data show changes for each day in time spent at specific types of places relative to the baseline period. The Google Mobility Data use a baseline of the median value for the corresponding day of the week during the 5-week period of January 3 through February 6, 2020.

Relative to the entire country, Bamako itself had a larger percent change—in absolute value—in the time spent at each of these places. Specifically, as reported in the Google Community Mobility Reports, for the period between June 13 and July 25, people in Mali spent two percent less time at grocery stores and pharmacies relative to the baseline period whereas people in Bamako specifically spent nine percent less time at grocery stores and pharmacies. A similar finding holds for other types of places. People in Mali spent five percent less time in parks, 25 percent less time at transportation stations, and four percent more time in residential spaces, relative to the baseline period. In comparison, people in Bamako specifically spent 12 percent less time in parks, 32 percent less time at transportation stations, and six percent more time in residential spaces relative to the baseline period. This highlights that the reduced mobility induced by the risk of contracting COVID-19 or the government response to the pandemic was concentrated mostly in Bamako. In areas outside of Bamako, by contrast, such pandemic-related disruptions were not as large.

Finally, we use information from the COVID-19 phone panel survey, our third source of information used to investigate the intensity of pandemic-related disruptions within Mali.7 Fig. 3 summarizes information about coronavirus-related awareness, beliefs, and behavior.8 We see that approximately everyone in the sample, with no discernible difference between urban and rural areas, had previously heard of the coronavirus and received some information about social distancing. Although most respondents are, reportedly, satisfied with the Malian government’s response to the coronavirus, those who live in rural areas are more satisfied on average than those who live in urban areas.9 Moreover, people living in urban areas are more likely to take extra health precautions due to the pandemic (e.g., wash their hands more than usual, avoid greetings with physical contact, and avoid gatherings with more than 10 people). However, and perhaps surprisingly, although most of the sample did reduce the number of times they went to the market or grocery store and were not able to stockpile more food than usual, we do not see a discernible difference in these reported behaviors between urban and rural households. Although these descriptive insights highlight reasons why maintaining food security may be generally challenging in Mali, extensive margin changes in these behaviors do not explain differences in pandemic-related food security challenges between urban and rural areas. As documented in other contexts, and as suggested by the Google Mobility Data, price effects could influence behavior on the intensive margin. More research is needed to fully understand these dynamics.

Fig. 3.

Coronavirus Pandemic Awareness, Beliefs, and Behavior. Notes: These descriptive statistics come from the World Bank’s COVID-19 high-frequency survey from Mali. Missing and refused responses are excluded from these statistics. Standard errors are clustered at the sampling cluster level. ∗∗∗, ∗∗, and ∗, in each graph’s label indicate statistical significance at the 1, 5, and 10 percent critical level, respectively. Table A1 in the Supplemental Appendix provides additional details on these statistics.

In this section we aim to as best as possible characterize the coronavirus pandemic in Mali. Much of the evidence we document is limited and represents only the beginning of our understanding of the effect of the pandemic in Mali many other countries in sub-Saharan Africa.10 Despite the critical limitations in COVID-19 testing in Mali and throughout much of sub-Saharan Africa, some evidence suggests that mortality rates due to COVID-19 seem to be lower in sub-Saharan African than elsewhere in the world (Nordling, 2020). Antibody tests of more than 3,000 blood donors in Kenya find that one in 20 Kenyans aged 15–64, representing roughly 1.6 million people, have antibodies to the COVID-19 virus (Uyoga et al., 2020).11 If this estimate is correct, then the spread of the virus in Kenya is roughly equivalent to Spain in mid-May 2020 which had about 27,000 recorded COVID-19 related deaths. At the time of the antibody study in Kenya, there were 100 COVID-19 related deaths, representing a dramatically lower COVID-19 mortality rate. The underlying cause of this observation remains unclear. The lower COVID-19 mortality rate could be due to the relatively young population in much of sub-Saharan Africa relative to the rest of the world, it could be due to exposure to malaria or other infectious diseases priming immune systems, or it could be due to limitations in collecting and analyzing mortality data (Maeda and Nkengasong, 2021).

3. Data

The primary data source for our analysis is the first round of the COVID-19 Panel Phone Survey of Households, collected by the Mali National Statistical Office, Institut National de la Statistique (INSTAT), in partnership with the World Bank.12 The survey is part of a regional effort to generate high-quality data on the coronavirus pandemic and its impacts in the West African Economic and Monetary Union (WAEMU) member countries. In Mali, the first round of the survey of Households was implemented between the end of May and early June 2020, and included 1,766 households. These households were drawn randomly from the Enquête Harmonisée des Conditions de Vie des Ménages (EHCVM) sample, which was conducted between October 2018 and July 2019 via a collaboration between INSTAT and the World Bank. The COVID-19 Panel Phone Survey of Households sample is nationally representative, representative of Bamako, and representative of both urban and rural areas.13 The survey uses a relatively short instrument focusing on a subset of modules from the EHCVM and new modules on knowledge, perception, and behavior relating to the coronavirus pandemic. We use data from only the 2018–2019 round of the EHCVM sample and the first round of the COVID-19 Panel Phone Survey of Households sample. Data collection of additional rounds of the COVID-19 Panel Phone Survey of Households is ongoing and subsequent analysis can and should investigate the persistence of effects over a longer period of time. Although, any future work using these subsequent rounds of phone survey data must address the August 2020 political coup in Mali.14

The EHCVM sample itself covered 8,390 households across Mali and is nationally representative, representative of Bamako, and representative of both urban and rural areas.15 The survey relies on a multi-module instrument covering topics including a household’s socio-economic characteristics, time-use, production activities, and welfare indicators such as consumption expenditure and food security. We use sampling weights generated by the World Bank’s LSMS-ISA Team to adjust for potential systematic attrition in the phone survey and to facilitate the calculation of nationally representative statistics. These sampling weights are derived from the 2018 EHCVM sampling frame and adjusted for response rates in the COVID-19 Panel Phone Survey of Households. We apply these sampling weights in both our descriptive statistics and regression estimates so to help address issues leading to non-representatives due to sample selection bias.16

3.1. Measuring food security

The United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) defines food security as existing, “when all people, at all times, have physical, social, and economic access to sufficient, safe, and nutritious food that meet their dietary needs and food preferences for an active and healthy life” (FAO, 1996, FAO, 2009). Although this definition is widely accepted, consistently measuring food security based on this definition is a considerable challenge (Carletto et al., 2013).

In this study, we use the FAO’s Food Insecurity Experience Scale (FIES) as primary outcome of interest. The FIES aims to measure food insecurity based on the direct experiences of people relating to food security (Ballard et al., 2013, Smith et al., 2017, Cafiero et al., 2018). This experience-based measure of food security offers more precision than model-based measures relying on national-level food supply (Coates, 2013, Smith et al., 2017). The FIES is constructed based on respondents’ responses to eight questions about their experience in various domains of food insecurity:

-

•

FS1: “Household members have been worried that they will not have enough to eat?”

-

•

FS2: “Household members have been worried that they cannot eat nutritious foods?”

-

•

FS3: “Household members had to eat always the same thing?”

-

•

FS4: “Household members had to skip a meal?”

-

•

FS5: “Household members had to eat less than they should?”

-

•

FS6: “Household members found nothing to eat at home?”

-

•

FS7: “Household members have been hungry but did not eat?”

-

•

FS8: “Household members have not eaten all day?”

Both the EHCVM sample and the COVID-19 phone survey include each of the eight FIES questions, which provides us a measure of food insecurity for both periods. We use the raw FIES score as a primary outcome as well as the food insecurity severity classifications developed by Cafiero et al. (2018) and applied in Smith et al. (2017) as follows: (a) We define “mild food insecurity” with a raw FIES score greater than zero. This definition of “mild food insecurity” aligns closely with the FAO’s definition of food security as having “physical, social, and economic access to sufficient, safe, and nutritious food […] at all times” (FAO, 2009). (b) We define “moderate food insecurity” with a raw FIES score greater than three. Finally, (c) we define “severe food insecurity” with a raw FIES score greater than seven—or answering affirmatively to each of the eight FIES questions.

Our classification of “moderate food insecurity” is roughly equivalent to the primary measure of experienced food insecurity used by Smith et al. (2017) to measure food insecurity globally, with two exceptions. First, in order to ensure measures of food security are comparable across countries, Smith et al. (2017) run the raw FIES score through a Rasch model which aims to correct for heterogeneity between countries that may influence responses to the FIES questions measuring food insecurity (Rasch, 1960). In our present application, since we are only examining food insecurity in one country, we simply define food insecurity classifications based on the global averages noted in Smith et al. (2017) and apply these classifications to the raw FIES score.17 Second, Smith et al. (2017) use an individual-level version of the FIES questions and in the present application we use household-level questions.

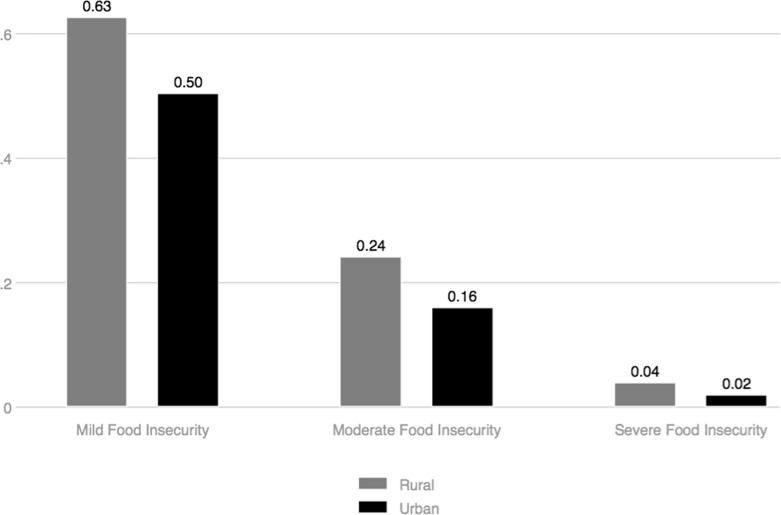

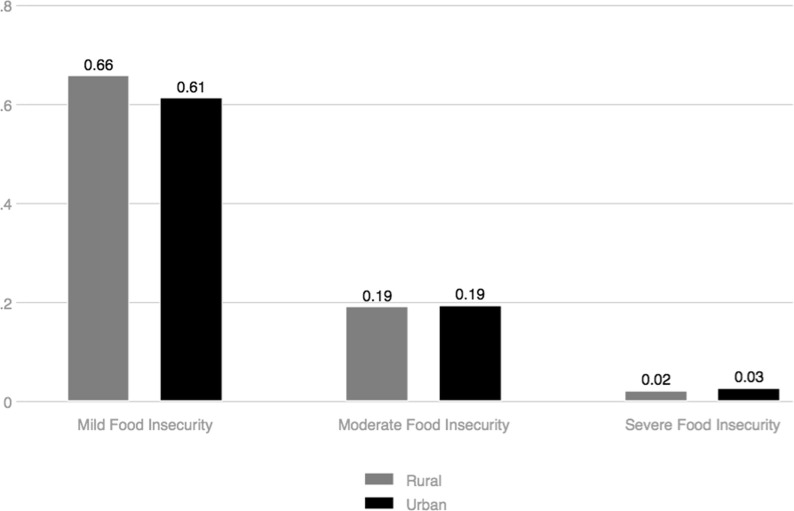

In Fig. 4 we show baseline mean levels, based on the EHCVM sample, of each of these three food insecurity classifications. In the leftmost panel, 63 of households in rural areas, compared to 50 percent in urban areas, experience “mild food insecurity.” Rural areas also experience higher rates of “moderate food insecurity,” with 24 percent of households experiencing this level of food insecurity compared to 16 percent of urban households, as shown in the middle panel. Finally, “severe food insecurity” remains relatively infrequent in both rural and urban areas, with 4 and 2 percent of households respectively experiencing this rather extreme level of food insecurity, as shown in the rightmost panel.

Fig. 4.

Food Insecurity Classifications—Baseline Levels. Notes: These descriptive statistics come from the EHCVM sample and represents the baseline levels of each of the three food insecurity classifications.

4. Estimation Strategy

Our estimation relies on a difference-in-differences empirical framework based on the presence of sub-national variation in the intensity of pandemic-related disruptions. As discussed in Section 2, urban areas in Mali experienced more intense pandemic-related disruptions than rural areas. This observation is consistent with existing predictions highlighting the primarily post-farm disruption of the coronavirus pandemic on food systems (Reardon et al., 2020), the fact that within the time-frame of our study the pandemic peaked prior to the beginning of the agricultural season in Mali, and the biological dynamics in which COVID-19 spreads via close human contact.

In our core regression specification, we compare the difference in food security measures between urban and rural areas before the peak of the coronavirus pandemic to the same difference after the peak. We estimate the following linear regression:

| (1) |

In Eq. (1), is an indicator of food security measured with the FIES within sampling cluster c, in household h, in time t. This outcome variable takes several forms throughout our analysis. First, we report the raw FIES score which is simply the sum of responses to the eight FIES questions each capturing a different component of experienced food insecurity at the household level. We standardize this variable so that this scale has a mean of zero and standard deviation of one in each survey wave. We take this approach for three reasons. (i) Since the data EHCVM sample was collected between October 2018 and July 2019 and the follow-up phone survey data was collected between May and June 2020 this standardization helps us avoid bias driven by seasonality. (ii) Since the baseline EHCVM food security indicator questions use a 12-month reference period and the COVID-19 phone survey use a 30-day reference period this standardization helps us avoid bias driven by these different reference periods. (iii) This standardization process allows for easier interpretation of our estimated coefficients in terms of standard deviations instead of a unitless score. Therefore, by standardizing the outcome within each survey wave the data represent deviations from the within-wave mean.18 Second, we report dichotomous indicators of different levels of food insecurity severity following Smith et al. (2017) and discussed above. These dichotomous variables represent “mild food insecurity,” “moderate food insecurity,” and “severe food insecurity” based on the raw FIES score.

On the right-hand-side of Eq. (1), is survey wave or time fixed effect, and is a household fixed effect. The coefficient represents the difference-in-differences estimate on the interaction between a dichotomous variable indicating the household resides in an urban area (or in Bamako, in alternative specifications) and a dichotomous variable indicating a post-pandemic outbreak survey wave. Finally, is the error term.19 When presenting these results we first show simple before-after comparisons, which do not consider any within-Mali variation. After presenting these simple before-after results, we show results that interact the before-after analysis with within-Mali variables as discussed above.

This empirical strategy relies on the obseration that disruptions due to the coronavirus pandemic have been much more severe in urban areas than in rural areas in Mali. We observe this variation from three different sources of information. First, according to the United Nations’ Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) and shown in Fig. 1, despite the fact that Bamako is home to roughly 12 percent of Mali’s population, over 60 percent of Mali’s COVID-19 infections were located in Bamako, as of the end of July 2020 (HDE, 2020). Although this statistic likely represents easier access to COVID-19 testing in Bamako relative to other parts of Mali and positive cases of COVID-19 likely do exist in rural areas, it does show that the recorded distribution of the prevalence of COVID-19 in Mali is dramatically skewed toward Bamako. Second, insights from Google’s Community Mobility Reports, shown in Fig. 2, suggest that individuals living in Bamako have experienced relatively large changes in the time spent at various types of places relative to a baseline period in early 2020. These changes in Bamako are larger than reported changes for individuals in all of Mali. Third, as documented in Fig. 3, according to our COVID-19 phone panel survey data individuals in urban areas are more likely to report taking health-related precautions and negative economic impacts due to the coronavirus pandemic than individuals in rural areas. As predicted by Reardon et al. (2020), this evidence highlights that although the coronavirus pandemic increased challenges related to food security everywhere, the pandemic is much more disruptive in urban areas than in rural areas in Mali.

The difference-in-differences identification strategy rests on the assumption of parallel counterfactual trends in latent food security between households in urban and rural areas (or, in some specifications, between households in Bamako and all else) in the absence of the coronavirus pandemic. This identifying assumption cannot be tested directly and is difficult to defend in the present context. Therefore, we are careful to point out that our results should be interpreted as merely descriptive. Numerous forms of omitted heterogeneity limit our ability to claim clean causal identification and the widespread disruption of the pandemic limit our ability to credible assess the sign or magnitude of the potential bias.20 Instead the difference-in-difference analysis should be interpreted as a descriptive analysis of effect heterogeneity within Mali associated with the coronavirus pandemic.

We do perform a number of robustness and sensitivity checks on our results. First, in each table reporting regression results we show two variations of our core specification: one that does not include household fixed effects and one that does include household fixed effects. The household fixed effects allow us to account for time-invariant omitted heterogeneity between households which may bias our results. Second, in the Supplemental Appendix, we show results that exclude all households in Bamako from the regression specification and therefore estimate differences between urban and rural areas outside Bamako. Although these estimates suffer from limited statistical power, we find results that are qualitatively similar to our core results.

5. Results

In this section we report three sets of results. First, we report descriptive results which come directly from the COVID-19 phone survey, targeted at understanding the responses to and socio-economic effects of the coronavirus pandemic. While these results do not specifically quantify the effect of the coronavirus pandemic on food security, they do provide insight of how individuals in Mali perceive the effect of the pandemic in their own lives. Second, we report estimation results based on variations of the regression specification in Eq. (1). These results provide some of the first estimates of the effect of the coronavirus pandemic in low- and middle-income countries. Third and finally, we discuss potential mechanisms and implement several robustness tests.

5.1. Descriptive results

These descriptive results provide insight by directly asking respondents if indicators for food insecurity are due “specifically to the COVID-19 crisis.” This allows for a self-reported causal statement, which is not necessarily equivalent to causal identification in the statistical use of the phrase. Nevertheless, these descriptive results highlight how respondents understand changes in their lives in the time of the coronavirus pandemic.

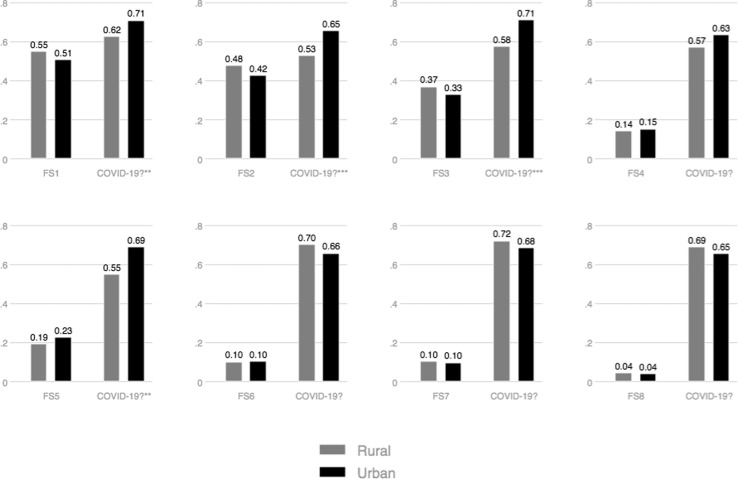

Fig. 5 shows descriptive results using the May-June 2020 phone survey from Mali. The results suggest that food insecurity has increased since prior to the coronavirus pandemic.21 Overall, 50 percent of the full sample is worried that they will not have enough to eat. Of those households, 65 percent report that this worry is specifically due to COVID-19. This finding, that a substantial share of households identify COVID-19 as an important cause of food security challenges, is largely driven by households in urban areas. Specifically, we see an 11 percentage points difference, between urban and rural areas, in those who identify COVID-19 as the source of their worry that they will not have enough to eat. Similar findings persist for most of the remaining FIES questions. Across seven of eight food security indicators, the exception being FS8 which is only experienced by less than 4 percent of households, a larger share of households living in urban areas than in rural areas report food security challenges due to COVID-19. In five out of the eight food security indicators the difference between urban and rural areas in reporting of food security challenges due to COVID-19 is statistically significant at conventional levels.

Fig. 5.

The Coronavirus Pandemic and Food Security Challenges—Descriptive Results. Notes: These descriptive statistics come from the World Bank’s COVID-19 high-frequency survey from Mali. Missing and refused responses are excluded from these statistics. Within each panel, the left-most two columns represent mean responses to each of the eight FIES questions (listed below). The right-most two columns represent mean responses to the question, “Was this due to the COVID-19 crisis?”. FS1 = “Household members have been worried that they will not have enough to eat?”. FS2 = “Household members have been worried that they can not eat nutritious foods?”. FS3 = “Household members had to eat always the same thing?”. FS4 = “Household members had to skip a meal?”. FS5 = “Household members had to eat less then they should?”. FS6 = “Household members found nothing to eat at home?”. FS7 = “Household members have been hungry but did not eat?”. FS8 = “Household members have not eaten all day?”. Standard errors are clustered at the sampling cluster level. ∗∗∗, ∗∗, and ∗ in each graph’s label indicate statistical significance at the 1, 5, and 10 percent critical level, respectively. Table A3 in the Supplemental Appendix provides additional details on these statistics.

These findings are striking for at least two reasons. First, specifically in the context of Mali, food security is on average more challenging in rural areas. Despite this, urban households tend to be more likely than rural households to identify COVID-19 as the most important cause of their food security challenges. In particular, 48 percent of rural households, compared to 42 percent of urban households, indicate being worried that they cannot eat nutritious foods. However, 53 percent of rural households, compared to 65 percent of urban households, indicate that this is primarily due to COVID-19—this difference is statistically significant at conventional levels. Second, this highlights the validity of previous predictions that the coronavirus pandemic would be more disruptive to food systems in dense urban and rural peri-urban areas (Reardon et al., 2020).

5.2. Estimation results

We now turn to discussing results from estimating variations of Eq. (1). In this sub-section we discuss four sets of results: the first considering the full raw FIES score and the remaining three considering increasingly severe levels of food insecurity.

Panel A of Table 1 shows estimates when using the raw FIES score standardized to have a mean of zero and standard deviation of one in each survey wave. The first two columns show simple first-difference estimation results. These results highlight that, relative to a pre-pandemic baseline, households in Mali do not report an increase in the raw FIES score. The last four columns of Panel A in Table 1 report variations on our main difference-in-difference estimation specification. Columns (3) and (4) explore differences in the coronavirus pandemic’s shock to the food system between urban and rural areas. Column (3) reports the results from a simplified difference-in-difference estimation specification which includes a single dichotomous variable indicating a household resides in an urban area, rather than household fixed effects. Column (4) reports the results from our main difference-in-difference estimation with household fixed effects. Both columns show that, relative to the pre-pandemic baseline, the raw FIES score increased more in urban areas than rural areas by about 0.18 of a standard deviation; though estimating this effect with household fixed effects increases the standard error around this estimate. Finally, in columns (5) and (6), when only considering differences between Bamako and elsewhere in Mali, the observed differential change in the raw FIES score falls slightly to about 0.15 of a standard deviation. This slightly smaller effect estimate is consistent with the idea that other urban or peri-urban areas are now included in the comparison and therefore bias the estimate toward zero.

Table 1.

The Coronavirus Pandemic and Food Insecurity.

| First-Difference |

Urban–Rural DID |

Bamako-Else DID |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Panel A: Standardized Raw FIES Score | |||||||

| After COVID started | −0.0166 | −0.0116 | −0.0697 | −0.0644 | −0.0363 | −0.0307 | |

| (0.0527) | (0.0751) | (0.0720) | (0.103) | (0.0600) | (0.0858) | ||

| Urban | −0.218∗∗∗ | ||||||

| (0.0639) | |||||||

| After COVID started Urban | 0.183∗∗ | 0.180 | |||||

| (0.0814) | (0.116) | ||||||

| Bamako | −0.217∗∗∗ | ||||||

| (0.0616) | |||||||

| After COVID started Bamako | 0.146∗ | 0.140 | |||||

| (0.0827) | (0.116) | ||||||

| Baseline Mean | −0.00 | −0.00 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.03 | 0.03 | |

| Panel B: Mild Food Insecurity (Raw Score) | |||||||

| After COVID started | 0.0457∗ | 0.0464 | 0.0238 | 0.0239 | 0.0321 | 0.0328 | |

| (0.0245) | (0.0346) | (0.0337) | (0.0476) | (0.0280) | (0.0396) | ||

| Urban | −0.122∗∗∗ | ||||||

| (0.0320) | |||||||

| After COVID started Urban | 0.0757∗ | 0.0768 | |||||

| (0.0392) | (0.0548) | ||||||

| Bamako | −0.144∗∗∗ | ||||||

| (0.0312) | |||||||

| After COVID started Bamako | 0.101∗∗ | 0.0997∗ | |||||

| (0.0394) | (0.0550) | ||||||

| Baseline Mean | 0.59 | 0.59 | 0.63 | 0.63 | 0.61 | 0.61 | |

| Panel C: Moderate Food Insecurity (Raw Score) | |||||||

| After COVID started | −0.0298 | −0.0288 | −0.0536∗ | −0.0529 | −0.0388 | −0.0377 | |

| (0.0220) | (0.0314) | (0.0298) | (0.0425) | (0.0249) | (0.0356) | ||

| Urban | −0.0792∗∗∗ | ||||||

| (0.0253) | |||||||

| After COVID started Urban | 0.0821∗∗ | 0.0821∗ | |||||

| (0.0339) | (0.0482) | ||||||

| Bamako | −0.0823∗∗∗ | ||||||

| (0.0251) | |||||||

| After COVID started Bamako | 0.0664∗ | 0.0651 | |||||

| (0.0360) | (0.0504) | ||||||

| Baseline Mean | 0.22 | 0.22 | 0.24 | 0.24 | 0.23 | 0.23 | |

| Panel D: Severe Food Insecurity (Raw Score) | |||||||

| After COVID started | −0.0116 | −0.0108 | −0.0187 | −0.0179 | −0.0125 | −0.0117 | |

| (0.0121) | (0.0170) | (0.0166) | (0.0235) | (0.0139) | (0.0196) | ||

| Urban | −0.0192 | ||||||

| (0.0139) | |||||||

| After COVID started Urban | 0.0244 | 0.0242 | |||||

| (0.0181) | (0.0256) | ||||||

| Bamako | −0.00707 | ||||||

| (0.0132) | |||||||

| After COVID started Bamako | 0.00679 | 0.00699 | |||||

| (0.0168) | (0.0238) | ||||||

| Baseline Mean | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.03 | |

| Observations | 3532 | 3532 | 3532 | 3532 | 3532 | 3532 | |

| Household FEs | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | |

| Missing Control | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

Notes: In columns (1) and (2), the “Baseline Mean” represents the pre-pandemic mean of the outcome variable in each panel. In the last four columns, the “Baseline Mean” represents the pre-pandemic mean of the outcome variable in the comparison area—e.g., rural areas in columns (3) and (4) and non-Bamako areas in columns (5) and (6). Standard errors are clustered at the sampling cluster level. ∗∗∗, ∗∗, and ∗, in each graph’s label indicate statistical significance at the 1, 5, and 10 percent critical level, respectively.

Panel B of Table 1 shows estimates using a dichotomous dependent variable indicating at least “mild food insecurity” defined as equal to one if the raw FIES score is greater than zero (Smith et al., 2017). These estimates are helpful for at least two key reasons. First, they provide a more intuitive assessment of effect magnitude than estimates reported in Panel A Table 1. The outcome variable identifies if a household responds affirmatively to any of the eight FEIS questions. Second, the definition of the dichotomous outcome variable used in Panel B of Table 1 aligns more closely with the FAO’s definition of food security (FAO, 1996, FAO, 2009). This is because the FAO’s definition views food security as existing “when all people, at all times, have physical, social, and economic access to sufficient, safe, and nutritious food that meet their dietary needs and food preferences for an active and healthy life,” which we measure if an individual does not answer affirmatively to any of the FIES questions.

The first two columns of Panel B of Table 1 show a simple first-difference estimation. These results highlight roughly a 4 percentage-point increase in the probability of being mildly food insecure, relative to the pre-pandemic period. The last four columns report variations on our main difference-in-difference estimation specification. Columns (3) and (4) show an increase in mild food insecurity of about 8 percentage points in urban areas relative to rural areas associated with the coronavirus pandemic. Again, although the inclusion of household fixed effects increases the standard error around this estimate the estimated average effect remains stable. Finally, columns (5) and (6) focus on differences between Bamako and the rest of Mali, and show qualitatively similar results to those reported in columns (3) and (4). The results indicate an increase in food insecurity of roughly 10 percentage points in Bamako relative to the rest of Mali associated with the pandemic. These effect estimates show meaningful increases in mild food insecurity. Considering a baseline mean of 0.61, in columns (5) and (6), our estimates show that the coronavirus pandemic increased mild food insecurity in Bamako by 16 percent relative to the rest of Mali. Indeed, the leftmost panel in Fig. 6 shows that the rural–urban gap in mild food insecurity has narrowed since before the pandemic.

Fig. 6.

Food Insecurity Classifications—Follow-up Levels. Notes: These descriptive statistics come from the COVID-19 Panel Phone Survey sample and represents the follow-up levels of each of the three food insecurity classifications.

Panel C of Table 1 reports results using a dichotomous dependent variable indicating “moderate food insecurity” defined as equal to one of the raw FIES score is greater than three (Smith et al., 2017) and is our primary measure of food insecurity. Although columns (1) and (2) show no evidence of an increasing time trend of moderate food insecurity in Mali associated with the pandemic, our difference-in-difference estimates in columns (3) and (4) highlight that in urban areas moderate food insecurity increased by 8 percentage points more than in rural areas. This represents a 33 percent increase in moderate food insecurity in urban areas relative to rural areas in Mali and represent the strongest estimates—in terms of magnitude and statistical significance—in this paper. This is important because existing research using the FIES across a variety of contexts consider this measure of “moderate food insecurity” as the primary measure of food insecurity (Smith et al., 2017). This measure, which identifies “moderate food insecurity” if a household responds affirmatively to at least three out of the eight FIES questions, more accurately represents the multidimensional reality of experienced food insecurity for households. Finally, we find qualitatively similar results in columns (5) and (6), when considering differences between Bamako and the rest of Mali, though these effects are less precisely estimated. Fig. 6 shows that the rural–urban gap in moderate food insecurity has completely vanished at the time of our follow-up survey.

Finally, Panel D of Table 1 reports the results using a dichotomous dependent variable indicating “severe food insecurity” defined as equal to one if the raw FIES score is greater than seven (Smith et al., 2017). This definition therefore requires that households have indicated affirmative responses on all eight of the FIES questions and is commonly associated with individuals experiencing physiological hunger (Nord, 2014). Perhaps unsurprisingly, due to the relative infrequency of this extreme level of food insecurity, these estimates suffer from low statistical power. We estimate effects with substantial magnitudes but that remain statistically indistinguishable from a null result. Specifically, severe food insecurity increased by roughly 60 percent in urban areas relative to rural areas, but this estimate is not statistically significant. Therefore, the results reported in Panel D of Table 1 should be interpreted with extreme caution. Severe food insecurity remains relatively uncommon in Mali, experienced by roughly three percent of the population prior to the coronavirus pandemic.

Existing predictions, based on modeling the expected changes to income, prices, and food supply, suggest that the coronavirus pandemic may increase the number of undernourished people in the world by between 10 and 16 percent in 2020 (Baqueano et al., 2020, FAO, 2020). Our estimates suggest that these aggregate global estimates may hide important heterogeneity. Overall, simple pre-post estimates for the entire country of Mali using each of our food insecurity measures show that food insecurity has remained relatively steady. However, in the context of urban Mali the short-term effect of the coronavirus pandemic is relatively large and represents a meaningful effect of the pandemic on food insecurity. In fact, the change in moderate food insecurity in urban areas associated with the coronavirus pandemic is so much larger than in rural areas that the rural–urban gap completely vanishes. This finding suggests that future work should focus on measuring the extent of heterogeneity in changes of food insecurity associated with the coronavirus pandemic. Understanding this heterogeneity is important for understanding how to best design, implement, and target policies and programs aimed at assisting those harmed most by the pandemic.

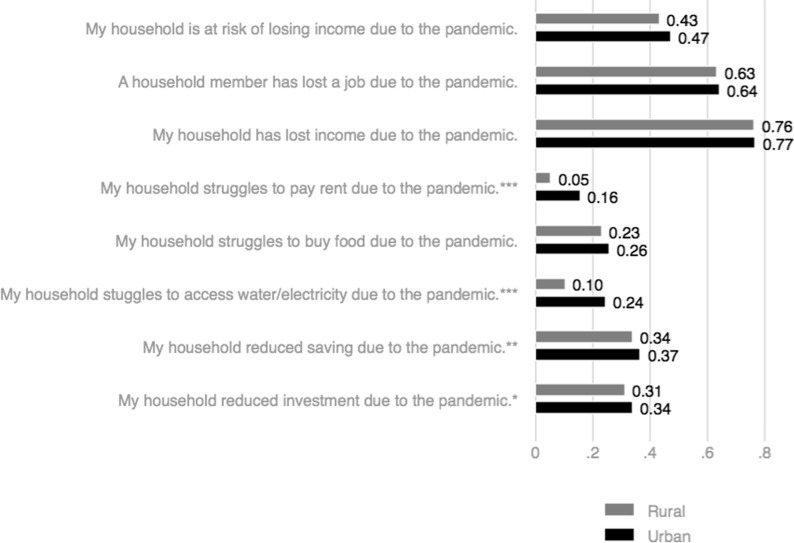

5.3. Mechanisms

Fig. 7 shows self-reported estimates of the impact of the coronavirus pandemic on economic outcomes using information from our COVID-19 phone panel survey.22 Each of the statistics reported in Fig. 7 are calculated from a dummy variable indicating if a household reports an affirmative response to each of the listed statements respectively. Most households, with no statistical difference between urban and rural areas, report that a household member has lost their job and report lost income due to the coronavirus pandemic. Slightly less than half of households, again with no statistical difference between urban and rural areas, feel at risk for losing more income in the future due to the pandemic. This highlights the magnitude and range of the economic shock associated with the pandemic. Roughly 16 percent of urban households, and only 5 percent of rural households experienced struggles to pay rent due to the pandemic. Although a similar pattern holds for accessing water or electricity, with 24 percent of urban households and 10 percent of rural households reporting struggles due to the pandemic, we see no reported difference in struggles to buy food between urban and rural areas. This essentially mirrors the finding documented in Fig. 3. In addition, we see relatively small but statistically significant differences in the ability to save money and invest in durable goods between urban and rural areas, with slightly more reported disruptions in urban areas.

Fig. 7.

Self-Reported Coronavirus Pandemic Impacts. Notes: These descriptive statistics come from the World Bank’s COVID-19 high-frequency survey from Mali and show unconditional differences in each of these variables between urban and rural areas. Missing and refused responses are excluded from these statistics. Standard errors are clustered at the sampling cluster level. ∗∗∗, ∗∗, and ∗, in the each graph’s label indicate statistical significance at the 1, 5, and 10 percent critical level. Table A2 in the Supplemental Appendix provides additional details on these statistics.

Although we cannot be sure of the exact mechanism with our present data, our descriptive results suggest several possibilities. First, and as documented in Fig. 7, although extensive margin changes in access to food do not explain the estimated differences in food security between urban and rural areas, it remains possible that intensive margin changes in food access and consumption explain the differential effects of the pandemic on food security between urban and rural areas. Future research should aim to understand the specific mechanisms driving context-dependent effects of the pandemic. The work of Narayanan and Saha (2020) which focuses primarily on analyzing price changes associated with the pandemic provides an example of this type of work. Second, the coronavirus pandemic seems to have had a much more salient and direct effect on the ability to pay rent, access water or electricity, save money, and invest in durable goods in Mali’s urban areas compared to rural areas. At the same time, we see no difference between urban and rural households in self-reported struggles to by food due to the pandemic. Despite this, our main results highlight that households in urban areas experience more food insecurity due to the pandemic than households in rural areas. Future research, using more detailed information on food prices in Mali, will do well to investigate the specific mechanisms that drive these differential effects.

5.4. Limitations and robustness

We conduct several robustness checks to test the sensitivity of our results. First, in Table A4 in the Supplemental Appendix, we show results where the raw FIES score is not standardized to have a mean of zero and standard deviation of one in each survey wave. Although we prefer the results using the standardized dependent variable, this robustness check shows that our core findings are not driven by our standardization procedure. Specifically, the difference-in-differences estimates shown in the last four columns of Table A4 are qualitatively similar to the core results reported in Panel A of Table 1.

Second, in Table A5 in the Supplemental Appendix, we show results that do not control for missing observations. This tests if our results are driven by the systematic non-response to specific survey questions. Specifically, if we found that estimates differ dramatically when we control for missing observations compared when we simply drop missing observations, we would be concerned about the influence of systematic non-response in our follow-up survey biasing our results. To the contrary, we find results that are qualitatively consistent with those reported in Table 1.

Third, in Table A6 in the Supplemental Appendix, we show results that exclude households in Bamako from the sample. This tests if our results are strictly driven by the effect of the pandemic within Bamako. To the contrary, we find qualitatively similar results outside Bamako, although the difference-in-difference estimates are not robust to the inclusion of household fixed effects, largely due to limited statistical power. We continue to find evidence of increasing food insecurity, at every level of severity, in urban areas relative to rural areas outside Bamako. This demonstrates that our core finding of effect heterogeneity between urban and rural areas is not simply driven by disruptions within Bamako specifically, but by disruptions to food security more dramatically felt by urban households compared to rural households. This finding can provide useful insight for future policy interventions in the immediate aftermath of a pandemic.

The analysis in this paper is not without limitations. First, and most generally, although the coronavirus pandemic has disrupted life in every country around the world, we study only one country. The effects of the pandemic on welfare may vary substantially across countries, largely due to the specific non-pharmaceutical policy response of each country. We argue, however, that the situation in Mali may resemble that in many other parts of Sub-Saharan Africa where public health measures intended to slow the spread of the virus are difficult to implement effectively, but were generally more disruptive in urban areas. The work of Amare et al. (2020) in Nigeria and Mahmud and Riley (2020) in Uganda provide complementary analysis highlighting the substantial effect of the pandemic on food security in Sub-Saharan Africa.

Second, our estimates only represent the short-term effects of the coronavirus pandemic on food security. As the spread of the virus began in Bamako, and therefore initial containment policies were most intense in the capitol city, the short-term effect of the pandemic is more directly felt by urban households. As time progresses, and the agricultural season gets underway, it is plausible, and in fact likely, that rural households will be increasingly affected by the consequences of the pandemic (Amjath-Babu et al., 2020). Indeed in many countries around the world, while the coronavirus pandemic first hit hardest in urban areas, over time the pandemic spread to more rural areas. Research on the effect of the Ebola epidemic in West Africa highlights the potential of the coronavirus pandemic to disrupt agricultural planing and harvesting and, in turn, rural livelihoods (de la Fuente et al., 2020). In addition, in August of 2020 Mali’s government implemented a food assistance program, which does not factor into our short-term results but clearly could influence medium-term or long-term changes in food insecurity.23 Future research specifically examining the medium- and long-term effects of the coronavirus pandemic, in both rural and urban areas, is absolutely essential.

Finally, we are unable to credibly identify mechanisms that explain our main findings. Research in India suggests that food prices in urban areas have increased which could lead to challenges relating to food security, especially for households that have lost a primary source of income due to pandemic-related disruptions (Narayanan and Saha, 2020). It is plausible that this mechanism persists in Mali, however, we do not have the data to examine this empirically. We do show some descriptive evidence suggesting that the pandemic has reduced the frequency of visits to the market or grocery store, but there is very little difference between households in urban and rural areas. Therefore, this type of extensive margin behavior change does not seem to explain our main results in a meaningful fashion. Future research should focus on identifying the mechanisms that explain these results to help inform effective policy responses.

6. Conclusion

We add to the emerging research investigating the consequences of the coronavirus pandemic on food security in low- and middle-income countries (Aggarwal et al., 2020, Amare et al., 2020, Ceballos et al., 2020, Mahmud and Riley, 2020). Using nationally representative pre-pandemic household survey data and a follow-up phone survey from Mali, our analysis highlights a dramatic increase in food insecurity in urban areas relative to rural areas within Mali at least in the relative short-term. These difference-in-difference estimates rely on sub-national variation in the intensity of pandemic-related disruptions between urban and rural areas. Although we aim to validate our understanding of the variation in intensity of these disruptions with data on recorded COVID-19 infections, Google mobility data, and our phone survey data, it remains likely that the pandemic also disrupted food systems in rural areas. Therefore, due to numerous sources of unobserved heterogeneity, our results should be interpreted as merely descriptive. Despite this limitation, we estimate changes in food insecurity associated with the pandemic with meaningful magnitudes.

Existing predictions of the effect of the coronavirus pandemic on food security globally—based on expected changes to income, prices, and food supply—point to an increase in the number of food insecure people in the world of between 10–16 percent in 2020 (Baqueano et al., 2020, FAO, 2020). Although some of the observed differences between existing estimates can be due to differences in empirical measures of food insecurity (Bloem and Farris, 2020), our estimates document important heterogeneity in this global aggregate prediction. Our findings show that moderate food insecurity increased in urban areas by about 8 percentage points, which is equivalent to about a 33 percent increase. This result, coupled with the observation that a larger share of Mali’s rural population experiences food insecurity than Mali’s urban population, highlights the critical importance of understanding the heterogeneity of the effect of the coronavirus pandemic. In the specific context of Mali, at least in the relative short-term, the rural–urban gap in experienced food insecurity completely vanished. These results, documenting the relative effects of the pandemic within a given context, are important for informing short-term policy responses aiming to limit the welfare loss from the coronavirus pandemic.

Our work in this paper only represents the beginning of the necessary research needed to better understand the micro-level welfare implicates of the coronavirus pandemic. Throughout this paper, we highlight many avenues for future research and encourage interdisciplinary approaches to address existing questions. These future research topics include a more detailed investigation of the mechanisms driving these relatively short-term effects and subsequent analysis of the medium-term effects which consider household-level resiliency to the dramatic health and economic shock of the coronavirus pandemic.

Footnotes

We thank Marc Bellemare, Steven Zahniser, and Cheryl Christensen, as well as colleagues from DIME, for helpful feedback on previous drafts of this paper. We also thank Chris Barrett and three anonymous referees for providing constructive comments on our initially submitted manuscript. The findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed in this paper are entirely those of the authors. They do not necessarily represent the views of the World Bank and its affiliated organizations, or those of the Executive Directors of the World Bank or the governments they represent. Also, they should not be construed to represent any official US Department of Agriculture or US Government determination of policy. All remaining errors are our own.

As in other Sahel countries, Mali experiences one rainy season every year. For most farmers this facilitates only one crop production period, which typically spans from mid-June through mid-September.

We will investigate and validate this claim in more detail in Section 2.

These measures could influence food security in a number of ways. First, suspending international travel could disrupt food imports and limit the supply of food. Second, closing public schools could also close school feeding programs which some children and families regularly rely. Finally, although large markets were not officially shutdown, banning large public gatherings could deter regular visits to busy agricultural markets.

The trend in Mali includes all areas within Mali including Bamako, Sikasso, and Segou.

To be clear, these data do not suggest that the coronavirus pandemic is no longer a critical concern for Mali. Indeed, these data only report recorded COVID-19 infections and deaths. Considering the likely limited COVID-19 testing and death monitoring capacity in Mali, especially outside Bamako and other urban areas, these reported figures may dramatically underestimate the true incidence of infections and deaths (UNICEF, 2020). Moreover the long-term consequences of the coronavirus pandemic, not just in Mali but throughout the world, are sill unknown.

Additional details about these data are available at https://www.google.com/covid19/mobility/.

These data are collected by Mali’s National Statistical Office in partnership with the World Bank. We discuss these data in much more detail in Section 3.

Table A1 in the Supplemental Appendix provides additional details on the statistics reported in Fig. 3.

We caution not to make too much of the difference between urban and rural areas in satisfaction with the government’s response to the pandemic. As Lipton (1977) explains governments tend to provide more services to households in urban areas than households in rural areas. Therefore, it may simply be that respondents in rural areas expect very little support from the government whereas respondents in urban areas have higher expectations for support from the government.

See Josephson et al. (2020) for additional preliminary findings on the effect of the coronavirus pandemic in other sub-Saharan African countries.

Similar findings are emerging from Malawi (Chibwana et al., 2020).

Publicly available at https://microdata.worldbank.org/index.php/catalog/3725/study-description.

Since the COVID-19 Panel Phone Survey of Households relies on phone interviews, the sampled households include only those who reported a valid phone number during the 2018 EHCVM survey. In some contexts this could generate selection bias. In Mali however, mobile phone technology use is high. Roughly 90 percent of the households surveyed in 2018 provided at least one phone number.

BBC: “Mali coup: President quits after soldier mutiny,” https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-53830348.

Definitions of urban and rural areas come from the government of Mali’s census data and are used by the LSMS Team at the World Bank when constructing the EHCVM sample. Specifically, urban areas are defined as areas with relatively high population density and where non-agricultural income sources are more prominent than agricultural income sources.

More information about the sampling strategy and construction of the sampling weights can be found here: https://microdata.worldbank.org/index.php/catalog/3725/study-description.

By doing this we assume that the way respondents answer the FIES survey questions is roughly equivalent throughout our sample. Although this assumption is common in any analysis of survey data, the measurement of food insecurity can be importantly influenced by the attitudes and expectations of respondents and applying the Rasch model to the FIES data is one way to adjust responses for potential bias (Wambogo et al., 2018).

We show results without this standardization procedure in the Supplemental Appendix. The estimates are qualitatively consistent.

We report our results using two variations of this regression specification. First, we show a more basic variation which includes a single dummy variable indicating the household resides in an urban area (or in Bamako, in alternative specifications) and no household fixed effect. Second, we show a more generalized variation which includes a household fixed effect. Since, the dummy variable indicating the household resides in an urban area (or in Bamako, in alternative specifications) is collinear with the household fixed effect, this dummy variable is omitted from the second regression specification.

For example, one reviewer pointed out that food insecurity tends to be strongly associated with poor physical and mental health. This could influence our results in at least two ways. First, poor physical or mental health may be a mechanism through which the pandemic influences food security. Second, individuals with already low physical or mental health may be more predisposed to be adversely affected by the pandemic-related disruptions, which could in turn influence their food security. While the former situation would not bias our results the later would bias our results in an unknown direction. Unfortunately, we do not have sufficient information on physical or mental health in our data. In addition, including household fixed effects in the regression would not adequately control for the latter and more serious dynamic.

Table A3 in the Supplemental Appendix provides additional details on the statistics reported in Fig. 5.

Table A2 in the Supplemental Appendix provides additional details on the statistics reported in Fig. 7.

USAID press release: https://www.usaid.gov/mali/press-releases/usaid-awards-4-million-wfp-covid-19-mali.

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodpol.2021.102050.

Supplementary material

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- Adams-Prassl, A., Boneva, T., Golin, M., Rauh, C., 2020. Inequality in the impact of the coronavirus shock: Evidence from real time surveys. Working paper.

- Aggarwal, S., Jeong, D., Kumar, N., Park, D.S., Robinson, J., Spearot, A., 2020. Did COVID-19 Market Disruptions Disrupt Food Security? Evidence from Households in Rural Liberia and Malawi. Tech. rep., National Bureau of Economic Research. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Alon, T., Doepke, M., Olmstead-Rumsey, J., Tertilt, M., 2020. The impact of covid-19 on gender equality. NBER Working Paper, No. 26947.

- Amare, M., Abay, K.A., Tiberti, L., Chamberlin, J., 2020. Impacts of covid-19 on food security: Panel data evidence from nigera. PEP Working Paper No. 21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Amjath-Babu T., Krupnik T., Thilsted S., McDonald A. Key indicators for monitoring food system disruptions caused by the covid-19 pandemic: Insights from bangladesh toward effective response. Food Secur. 2020;12:761–768. doi: 10.1007/s12571-020-01083-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arndt C., Davies R., Gabriel S., Harris L., Makrelov K., Robinson S., Levy S., Simbanegavi W., van Sventer D., Anderson L. Covid-19 lockdowns, income distribution, and food security, an analysis for south africa. Global. Food Secur. 2020;26 doi: 10.1016/j.gfs.2020.100410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballard T.J., Kepple A.W., Cafiero C. FAO; Rome: 2013. The food insecurity experience scale: development of a global standard for monitoring hunger worldwide. [Google Scholar]

- Baqueano, F., Christensen, C., Ajewole, K., Backman, J., 2020. International food security assessment, 2020–30. GFA–31, U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service.

- Barrero, J., Bloom, N., Davis, S., 2020. Covid-19 is also a reallocation shock. NBER Working Paper, No. 27137.

- Bartik, A., Bertrand, M., Cullen, Z., Glaeser, E., Luca, M., Stanton, C., 2020. How are small businesses adjusting to covid-19? early evidence from a survey. NBER Working Paper, No. 26989.

- Bene C. Resilience of local food systems and links to food security: A review of some important concepts in the context of covid-19 and other shocks. Food Secur. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s12571-020-01076-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bloem, J., Farris, J., 2020. The coronavirus pandemic and global food security: A review. Working Paper.

- Bui, T., Button, P., Picciotti, E., 2020. Early evidence on the impact of covid-19 and the recession on older workers. NBER Working Paper, No. 27448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Cafiero C., Viviani S., Nord M. Food security measurement in a global context: The food insecurity experience scale. Measurement. 2018;116:146–152. [Google Scholar]

- Carletto C., Zezza A., Banerjee R. Towards better measurement of household food security: Harmonizing indicators and the role of household surveys. Global Food Secur. 2013;2(1):30–40. [Google Scholar]

- Ceballos F., Kannan S., Kramer B. Impacts of a national lockdown on smallholder farmers’ income and food security: Empirical evidence from two states in india. World Dev. 2020;136 [Google Scholar]

- Chetty, R., Friedman, J., Stepner, M., the Opportunity Insights Team, 2020. How did covid-19 and stabilization policies affect spending and employment? a new real-time economic tracker based on private sector data. Working Paper.

- Chibwana, M., Jere, K., Kamn’gona, R., Mandolo, J., Katunga-Phiri, V., Tembo, D., Mitole, N., Musasa, S., Sichone, S., Lakudzala, A., Sibale, L., Matambo, P., Kadwala, I., Byrne, R., Mbewe, A., Morton, B., Phiri, C., Mallewa, J., Mwandumba, H., Adams, E., Gordon, S., Jambo, K., 2020. High sars-cov-2 seroprevalence in health care workers but relatively low numbers of deaths in urban Malawi. medRxiv, Preprint, Available online: August 1, 2020.

- Coates J. Build it back better: Deconstructing food security for improved measurement and action. Global Food Secur. 2013:188–194. [Google Scholar]

- Coibion, O., Gorodnichenko, Y., Webber, W., 2020. Labor market during the covid-19 crisis: A preliminary view. NBER Working Paper, No. 27017.

- Cowan, B., 2020. Short-run effects of covid-19 on u.s. worker transitions. NBER Working Paper, No. 27315.

- de la Fuente A., Jacoby H., Lawin K. Impact of the west african ebola epidemic on agricultural production and rural welfare: Evidence from liberia. J. Afr. Econ. 2020;29:454–474. [Google Scholar]

- Devereux S., Bene C., Hoddinott J. Conceptualizing covid-19’s impacts on household food security. Food Secur. 2020;12:769–772. doi: 10.1007/s12571-020-01085-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Djiofack, C., Dudu, H., Zeufack, A., 2020. Assessing covid-19’s economic impact in sub-saharan africa: Insights from a cge model. COVID-19 in Developing Countries, (ed. Djankov, S. and Panizza, U.).

- FAO, 1996. Declaration on world food security and world food summit plan of action. world food summit. World Food Summit, Rome: FAO.

- FAO . FAO; Rome: 2009. Declaration of the world summit on food security. World Summit on Food Security. [Google Scholar]

- FAO, IFAD, UNICEF, WFP and WHO, 2020. The state of food security and nutrition in the world: Transforming food systems for affordable healthy diets. Rome, FAO.

- Gerard, F., Imbert, C., Orkin, K., 2020. Social protection response to the covid-19 crisis: Option is for developing countries. Policy Brief: Economics for Inclusive Prosperity.

- Hale, T., Petherick, A., Phillips, T., Webster, S., 2020. Variation in government responses to covid-19. Blavatnik school of government working paper, 31.

- HDE, 2020. Mali: Coronavirus (covid-19) subnational cases. Humanitarian Data Exchange, United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs.

- Hoy, C., Sumner, A., 2020. Growth with adjictives: Global poverty and inequality after the pandemic. Center for Global Development Working Paper.

- Jain, R., Budlender, J., Zizzamia, R., Bassier, I., 2020. The labor market and poverty impacts of covid-19 in south africa. CSAE Working Paper.

- Josephson, A., Michler, J., Killic, T., 2020. Microeconomic impact of covid-19 in africa. Working Paper.

- Kerr, A., Thornton, A., 2020. Essential workers, working from home and job loss vulnerability in south africa. Working Paper.

- Lipton M. Australian National University Press; 1977. Why poor people stay poor: A study of urban bias in world development. [Google Scholar]

- Maeda J., Nkengasong J. The puzzle of the covid-19 pandemic in africa. Science. 2021;371:27–28. doi: 10.1126/science.abf8832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahmud, M., Riley, E., 2020. Household response to an extreme shock: Evidence on the immediate impact of the covid-19 lockdown on economic outcomes and well-being in rural uganda. Working Paper. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Mishra K., Rampal J. World Development; 2020. The covid-19 pandemic and food insecurity: A viewpoint on india. [Google Scholar]

- Narayanan, S., Saha, S., 2020. Urban food markets and the lockdown in india. Working Paper.

- Nord M. FAO; Rome: 2014. Introduction to item response theory applied to food security measurement: Basic concepts, parameters, and statistics. [Google Scholar]

- Nordling, L., 2020. The pandemic appears to have spared africa so far. scientists are struggling to explain why. Science, Available online: August 11, 2020.

- Rasch G. Danish institute for Educational Research; Copenhagen: 1960. Probabilistic models for some intelligence and achievement tests. [Google Scholar]

- Ravallion M. Center for Global Development Working Paper; 2020. Sdg1: The last three percent. [Google Scholar]

- Ravindran, S., Shah, M., 2020. Unintended consequences of lockdowns: Covid-19 and the shadow pandemic. NBER Working Paper, No. 27562. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Reardon T., Bellemare M., Zilberman D. How covid-19 may disrupt food supply chains in developing countries. IFPRI Blog Post. 2020 [Google Scholar]