Abstract

The COVID-19 outbreak forced national governments to the adoption of social distancing and movement limitation measures aimed to reduce the diffusion of the virus and to mitigate its highly disruptive impact on the healthcare systems. Reduced income, job insecurity, distribution system interruptions, product shortages, localized price hikes, and time availability resulted in changes in food-related behaviors of households, including food waste generation. Although the significant progress achieved in the understanding of the multidimensional determinants of food losses and waste, no study has been considering the role of uncertainty generated by exogenous generalized shocks on consumer behavior. Building on an original and nationally representative survey, this work aims to investigate the impact of the measures introduced to contain the outbreak of COVID-19 on the main behavioral factors underpinning household food waste generation. The study develops a theoretical model introducing uncertainty validated through a Structural Equations Modelling approach. Results showed that during the quarantine period declared household food waste decreased, with more than half of the respondents reporting to waste less. The model suggested that the amount of material and non-material resources that consumers can dedicate to food-related activities represents the most influential factor for the generation of household food waste and that uncertainty is significantly affecting the drivers and indirectly influencing the self-declared values of food waste. Results suggest several potential policy implications, of which the most relevant being related to the importance of stimulating improvements in food management opportunities at home.

Keywords: COVID-19, Food waste, Exogenous shock, Uncertainty, Structural Equation Model

1. Introduction

The COVID-19 outbreak forced national governments to implement social distancing and other restrictive measures that imposed dramatic changes in the collective management of workplaces, schools and universities, commercial and recreational centers, transportation systems (EU, 2020), and private households’ behaviors. Because of the initial unexpected evolution of the outbreak, national governments were forced to introduce containment policies that have been implemented over time, with increasing levels of severity and some lack in coordination and coherence (Hale et al., 2020; Pott, 2020). For example, in the Italian case, 10 tailored legislative measures were introduced in a period of 4 months, often generating confusion regarding their aims and implementation.

Despite these uncertainties, measures proved to be effective in containing the diffusion of the virus and reducing the burden on national healthcare systems. At the same time, the lockdown had severe consequences for the economic system, both at community and individual levels.

Food supply chains have been affected in many ways and across all stages, from agricultural production to consumption, suffering unprecedented stresses (OECD, 2020; Singh et al., 2020). This is true in particular in terms of food access, food security and food safety, that emerged as a major concern due to the potential transmission of COVID-19 by food and food packaging along the supply chain (Galanakis, 2020; Rizou et al., 2020).

On the supply side social restrictions and quarantine measures generated serious inefficiencies and distortions, potentially leading to limitations in food access and to the generation of food losses. Certain production sectors suffered from labor shortages as a consequence of limited mobility, with potential impacts on sowing and harvesting. Processing experienced distress due to the internal social distancing and safety measures that allowed maintaining facilities active but with a reduced staff and, therefore, a limited production capacity. These constraints affected distribution and logistics, especially concerning perishable high-value products when international transport was engaged due to delays at country borders to perform inspections and controls. The forced interruption of the activities of restaurants, fast foods, and other eating facilities like catering services represented an additional direct effect of restrictions (OECD, 2020).

On the demand side the interruption of eating facilities generated a peak in the consumption of food at home. Food access was affected by distribution system disruptions, product shortages, and localized price hikes, influencing consumer's preferences and purchase decisions. Lifestyle modifications, reduced income, and job insecurity contributed to generate psychological stress and a growing sense of uncertainty, including threats to food security (Galanakis, 2020), that, together with a drastic change in terms of time availability, induced individuals to cope through changes in behaviors and eating habits (Ibn-Mohammed et al., 2021; OECD, 2020). Indeed, consumers adopted adjustments in purchasing, preserving, and disposing food to pursuit food access and food security. These behavioral shifts also affected the generation of household food waste that, since a decade, is recognized as a major challenge for food system sustainability (Stenmarck et al., 2016). This is emphasized by the commitment taken by the European Commission (EC) that, coherently with the United Nations' Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 12.3, is engaged in halving per capita food waste at retail and consumer level by 2030 (UN General Assembly, 2015). Additionally, the EU Farm to Fork strategy for sustainable food includes specific food waste measures as the introduction of EU-level legally binding targets for food waste reduction by 2023 and the revision of the EU rules on date marking ('use by' and 'best before' dates) by the end of 2022 (European Commission, 2020). Under this framework, changes that occurred to consumers’ food management and behaviors at the beginning of the COVID-19 outbreak led many organizations to recognize food waste as a major concern. Initially, part of the specialized press identified the effects of social restrictions and quarantine measures as responsible for a potential rise of food waste levels (World Economic Forum, 2020; FAO, 2020). However, after the initial concerns, literature generally reported decreases in household food waste during the first wave of the pandemic (Principato et al., 2020; Roe et al., 2021).

In this work the hypothesis is that household food waste generation decreased during the lockdown, due to specific situational factors as the increase of purchase of non-perishable items, the availability of time dedicated to cooking and food management, and the concern about food shortage. Food waste drivers are indeed related to individual capabilities, attitudes and access. Capabilities regard the capacity of properly preserving and cooking food, planning and buying the necessary amount. Attitudes refer to time and awareness regarding food waste. Access describes what households would consider quality food, defined as the sum of all properties and assessable attributes of a food item (Canali et al., 2016; Grainger et al., 2018; Hebrok and Boks, 2017). All these behavioural drivers are most likely to be severely affected by the COVID-19 related restrictions and by the quarantine that followed.

Many theoretical frameworks have been developed to analyze which drivers are the most relevant in explaining food waste and how they are influencing each other. Here a specific theoretical framework is selected, explored, and further developed in the context of an extreme and unforeseen event that occurred and generated uncertainty influencing food waste drivers. In addition, data used in this research were collected though a survey submitted to a sample representative of the Italian adult population ensuring a more reliable dataset compared to studies basing on viral surveys and convenience samples.

Indeed, this paper aims to advance the field by assessing the effect of the exogenous shock, as the introduction of social restrictions and quarantine measures, on the determinants of consumers’ food waste behavior and perceptions, providing policy makers information on which interventions might be more promising to improve the sustainability of food systems and, as a consequence, on the capability of risk management.

The paper is organized as it follows: Section 2 outlines the theoretical framework of the research and describes the key components of the conceptual model. Section 3 presents the sampling procedure and the questionnaire, and describes the methodology applied in the study. Results are shown and analyzed in the frame of existing literature in Section 4. Finally, Section 5 discusses conclusions and implications for research and policy.

2. Conceptual development

The discussion around the relation between consumers’ behavior and food waste have been articulated through different models and approaches such as the Theory of Planned Behavior (Ajzen, 2015, 1991), the Values-Beliefs-Norms (Stern, 2000, 1999), and the Motivation-Opportunity-Ability (MOA) framework (MacInnis et al., 1991; Rothschild, 1999). This work builds and further develops the latter.

According to the MOA framework (MacInnis et al., 1991), consumers’ information processing and consequent decisions are mediated by personal motivations, opportunities, and abilities. While being related to the personal sphere, the context in which consumers live deeply influence those drivers. Initially designed for marketing research (MacInnis et al., 1991; Rothschild, 1999), the MOA framework has been recently adapted also to understand and predict household food waste (de Hooge et al., 2018; Mehner et al., 2020; van Geffen et al., 2020a) and in this context, the drivers assume new elements and meanings.

In the application to this domain Motivation can be defined as the intention of an individual to perform certain actions, as avoiding household food waste, and is influenced by the personal awareness of individual and social consequences of food waste (Graham-Rowe et al., 2015; Parizeau et al., 2015; Setti et al., 2018; van Geffen et al., 2020a). It depends on injunctive and descriptive social norms, the former being related to the consumer's perception of food waste as a socially disapproved behavior (Lapinski and Rimal, 2005), and the latter reflecting personal perceptions on other consumers’ efforts in preventing food waste (Cialdini et al., 1991).

Ability is referred to the individual capacity to deal with the creation, management, and reduction of food waste, relying on personal knowledge and skills (MacInnis et al., 1991; Rothschild, 1999). Therefore, it is related to the capability of planning the purchase and preparation of food, the proficiency with food preparation skills, the knowledge of storing techniques, the capacity to assess food safety (e.g., through the understanding of labeling), and, more in general, to the personal level of food literacy (Bravi et al., 2020; de Hooge et al., 2018; Neff et al., 2019; Quested et al., 2013; Secondi, 2019; van Geffen et al., 2020a).

Finally, Opportunity refers to the possibility to access external material and non-material resources such as time, technology, and infrastructures that allow an individual to perform the intended actions (MacInnis et al., 1991; Rothschild, 1999). In food domain it relates to the actual or perceived availability of time for grocery shopping, cooking activities, and learning new food-related skills (non-material resources). It involves the possibility to access the grocery stores, and to purchase affordable and quality food in suitable packs and portions (material resources). Additionally, Opportunity is related also to the availability of stocking capacity and kitchen tools (Katajajuuri et al., 2012; Stancu et al., 2016; Van Garde and Woodburn, 1987; van Geffen et al., 2020a).

Researches exploiting the MOA framework usually take into consideration these three theoretical unobservable constructs to inquiry about their role in influencing household food waste. However, to our knowledge, no study has been considering the role of uncertainty generated by exogenous generalized shocks on consumer behavior in the context of food waste. Moreover, behavioral economics proved that the presence of possible adverse future events that cannot be estimated precisely undermines the rationality of decisions, including those related to purchasing habits. This can lead individuals to assume potential irrational behaviors, with unexpected consequences (Kahneman and Tversky, 1979; Setti et al., 2018; Tversky and Fox, 1995; Tversky and Kahneman, 1992) that should be taken in consideration when analyzing food waste drivers.

An exogenous shock is generally defined as an unexpected or unpredictable event that affects an economy, either positively or negatively (Geithner, 2003). In this context, the exogenous shock for consumers can be represented both by the COVID-19 outbreak and by the introduction of strict social distancing and movement limitation measures. In Italy, the very limited time elapsed between the outbreak of the COVID-19 and the implementation of restrictions of movement did not provide consumers enough time to adapt their behaviors to the evolution of the pandemic, with the exception of an initial short period of panic, when consumers were accumulating basic goods.

This work assumes that behavioral changes are mostly led by restrictive measures, rather than by the pandemic itself. In this context of early months of the pandemic, very little was known in terms of COVID-19 diffusion dynamics, progress of the disease, health consequences, impacts on the food supply chain (as described above) and tools to mitigate those impacts. In addition, the highly restrictions adopted to contain the COVID-19 outbreak meant that the only possible occasions to be in contact with other people were linked to food shopping, with the exception of the few professionals that were allowed to go to work, as doctors, police officers and few others. Therefore, the restrictions generated a consistent level of uncertainty for all consumers, regardless their socio-economic status, exacerbated also by mass media.

In order to assess whether these restrictive measures and their consequences affect the behavioral drivers of food waste, the element of Uncertainty, considered as an independent, unobservable construct, has been implemented in the MOA framework. More specifically, it refers to the food security of the household, in particular to the potential unavailability of food in stores, and to the shopping stress intended as the perceived sense of risk to contract the COVID-19 in a shopping facility. This decision was taken because restrictions were introduced suddenly and forced the entire population to adopt a similar lifestyle since the only source for food were large retailers and local shops. While the concept of risk in economics is associated with a measurable probability of future events, the concept of uncertainty refers to a situation of incomplete information or knowledge about a situation and where the possible alternatives or the probability of their occurrence or their outcomes are not known by the subjects (Scholz, 1983). Indeed, this was the case for the restrictions adopted to contain the COVID-19 outbreak, due to the unknown consequences of the pandemic. Uncertainty, in this context, is related to the fear of being exposed to the COVID-19 virus during grocery shopping, the social pressure inside the shops, the possible lack of food available in shops, the change in the number of meals consumed at home, and the occurrence (or absence) of unforeseen events influencing the management of meals (like a plan for a meal with a fixed number of persons replaced by eating elsewhere, or with fewer/more persons). Indeed, time availability has proven to be a relevant driver of household food waste since it is correlated with the occurrence of inefficient behaviors (Smith and Landry, 2020).

Finally, demographic variables (age, gender, income level, education level, area of residence, and composition of the household) have an indirect effect on household food waste, through the influence on Motivation, Ability, and Opportunity constructs (van Geffen et al., 2020b, 2016).

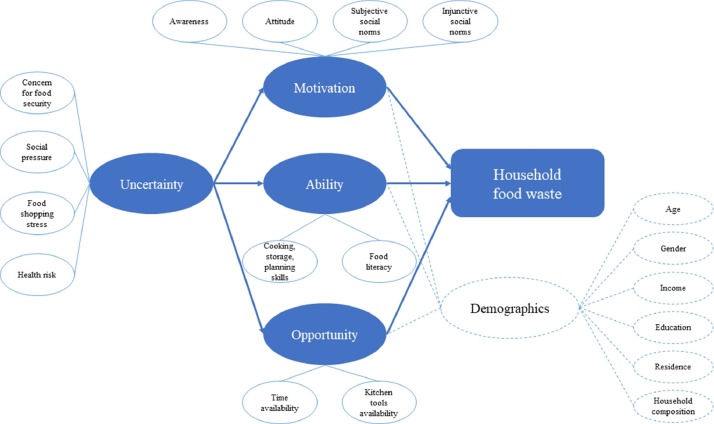

To conclude, the research hypothesis on which this work is rooted assumes this new theoretical construct to have an indirect effect on household food waste, through the influence on the other three constructs of the model. The final theoretical model is then an extended version of the MOA framework, which is integrated with the Uncertainty theoretical construct, and will be referred to as the MOAU (Motivation-Opportunity-Ability-Uncertainty). While these drivers have been extensively analyzed by literature, most of the studies are assessing them in isolation or within specific subsets (George et al., 2010; T. Quested & Parry, 2017; Silvennoinen et al., 2012; Stancu et al., 2016; WRAP & French-Brooks, 2012 among others). The MOAU is focusing on how they interact and influence each other, developing an integrated approach validated through empirical data. Fig. 1 summarizes the theoretical constructs of the MOAU framework and their relationships with each other and which their corresponding food waste drivers.

Fig. 1.

The MOAU framework and the drivers of household food waste.

This work proposes and validates the MOAU model, assessing the role of Uncertainty generated by the restriction measures. The validation of the model has been performed with the analysis of data collected through an original survey tailored on the MOAU approach and submitted to 1,500 Italian households during May 2020 through a confirmatory Structural Equations Model.

3. Methodology

3.1. Context

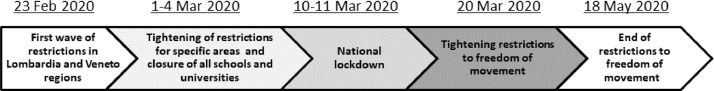

Italy has been the first European country severely hit by the COVID-19 outbreak in late January 2020. From February 23rd, the Italian Government implemented several social restriction measures to contain the diffusion of the pandemic. Fig. 2 shows the time sequence of the introduction of the restrictions. At first restrictions were limited to specific territories, with the establishment of the first “Red Zone” in Lombardia and Veneto Regions, where only retailers selling essential goods, including food, could operate. All the other activities, including restaurants and bars, were forced to close. In addition, access to shops was allowed only with specific protections (masks and gloves) and maintaining a minimum distance of one meter. Two days later, these restrictions were extended to Emilia-Romagna, Friuli-Venezia Giulia, Liguria, and Piemonte. Additional measures were also introduced: sports events were canceled, smart working was established in many public organization and private companies, specific procedures were adopted in any work environment.

Fig. 2.

Timeline of COVID-19 restrictions introduced by the Italian government.

New “Red Zones” and new restrictions were introduced on March 1st. Schools of any grade including universities were then closed on March 4th in the entire national territory.

In the extreme attempt to contain the diffusion of the pandemic to the southern regions of Italy, Lombardia and 14 provinces in Emilia-Romagna, Veneto, and Marche regions were officially locked down on March 8th. More severe social distancing rules were enforced and paired with the introduction of limitations of movements not related to working activities and with more severe restrictions applied to food-related activities (e.g., farmers markets and shops selling non-essential goods were closed, restaurants and cafes were allowed to work only as takeaway and delivery).

Finally, on March 11th, the lock-down was extended to the entire national territory, and the freedom of movement was suspended for all Italian citizens, with the exception of the workers providing essential services, like healthcare professionals or food retail staff. However, certain activities as playing individual sport remained possible until March 20th, when all types of movements were forbidden, including access to parks, villas, playgrounds, and all outdoor activities. From March 20th Italian citizens were allowed to get out of home out only to purchase food and essential goods. In this context going out was perceived as a danger for the risk to contracting COVID-19 as well for the possibility to incur a fine due to the strict controls performed by policy officers.

Limitations to freedom of movement began to be relaxed nearly two months later, on May 4th, when mobility across municipalities was allowed again. From May 18th, 2020, citizens have been allowed to leave their homes for a wider typology of motivations while social distancing and other measures, as wearing masks and avoiding crowded places, were still enforced and encouraged. For a complete timeline of governmental interventions see Appendix A.

3.2. Questionnaire development

Given the problematic context and the objective of the study, a survey was considered as the safest and most efficient option for data collection, as it allowed to gather large quantities of data in a small amount of time with no physical interactions.

The questionnaire was designed following the conceptual framework of the MOA integrated with Uncertainty due to the restrictions related to COVID-19 outbreak, as illustrated in Fig. 1. The aim was to outline the differences in behaviors during quarantine in comparison with the previous period. To do so, all the questions were set as a juxtaposition between the two periods. The 42 questions that composed the questionnaire were organized in 7 sections, related to the screening of participants, to grocery shopping habits, meal preparation, stock management, use of meal leftovers, and demographic characteristics.

More in detail, Section 1 (items S0-S4) was dedicated to the screening of respondents, Section 2 (items Q1-Q11a) concerned grocery shopping habits and planning, Section 3 (items Q12 to Q16) referred to meal preparation, Section 4 (items Q17, Q18) investigated behaviors and habits related to stock management, and Section 5 (items Q19-Q25) investigated the self-declared variations of the quantity of food waste generated by the household. Finally, Section 6 (items Q26-Q29) investigated to the analysis of a set of behaviors and habits adopted by the household during the quarantine and the comparison with the previous period, and Section 7 (items Q32-Q38) concerned the socio-demographic characteristics of the respondent's household.

In each section specific questions aimed to investigate the theoretical constructs of the MOAU framework. Items related to Motivation regarded awareness and attitudes on FW and its consequences, and the influence of social norms. It should be noted that questions related to Motivation were put in a negative sense, depict actually de-motivation as this shall have an impact on the interpretation of the results. Opportunity was quantified through items about the availability of time, products, store accessibility, storage space awareness. Regarding Ability, answers reported information on creative cooking, food safety assessments, and skills in planning.

Moreover, as the element of novelty, specific items were introduced to explore elements of uncertainty brought up by the restriction measures. They regarded questions about the fear of getting sick during grocery shopping, the perceived “environmental pressure” inside the shops (avoiding other people, being asked to shop quickly), the change in the number of meals had at home, and the occurrence of unforeseen events over the meal management.

Regarding the outcome variable of interest, the perceived variation of household food waste amount was inquired via self-reporting questions both on an aggregated and type-specific food level. Two questions were designed to capture the perceived differences in generic food waste during the quarantine with respect to the previous period, while a question made of 31 sub items was exploited to investigate perception over specific food typologies. No direct measurement of food waste was requested to respondents. Literature on food waste highlights the possibility of social desirability and hypothetical biases influencing survey answers potentially leading to an underestimation of the quantities of food waste generated in the household (Giordano et al., 2019; Quested et al., 2020; Vittuari et al., 2020). However, the primary scope of this exercise was to assess the shifts in declared household food waste and related behaviors generated by the introduction of COVID-19 social restrictions. This approach relaxes the need to quantify the amount of household food waste.

Finally, socio-demographic characteristics were assessed through gender, age, education, income, region, urban-rural living area, work status during the quarantine, and household composition. For the complete list of questions, see Supplementary materials.

Items were made using 7-point Likert scales to evaluate the level of agreement with specific statements or the frequency in taking certain actions. When different choice options were used, they were presented in randomized order to avoid item-ordering effects.

3.3. The survey and the sample

The survey was submitted to a representative sample of Italian consumers older than 18 years of age who were responsible for at least half of the food shopping and cooking in the household and were not sick for more than two weeks during the quarantine. The selected sample was nationally representative in terms of key demographics: household size, gender, age, income, education, region, and urban-rural living area1 . Since the survey was carried out in Italy, the ‘quarantine’ period was considered as the one between March 11th and May 17th, 2020. The period before the March 11th was referred to as the period prior to the quarantine. A professional market research organization, MSI-ACI EUROPE BV, was responsible for the coordination, recruitment, and data collection of the survey, which took place during May 2020. The survey was conducted online through computer-assisted web interviewing (CAWI) and was compliant with the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). The final sample was composed of 1,500 respondents.

3.4. Data analysis

Survey outcomes were analyzed in several stages. First, descriptive statistics were computed for all measures and used to explore the dataset. Gender differences were considered as a relevant aspect of describing differences in food management and attitudes.

Then, exploratory factor analysis was conducted to look at the underlying covariance structure of the data and to explore the structure of the latent factors that account for the relationship between the observable response and explanatory variables.

Finally, the relationship between declared household food waste and its determinants as well as with the uncertainty associated with the COVID-19 related restrictions was quantified through a Structural Equation Model (SEM). The model represents one of the most used methodologies to elaborate behavioral data as it allows to simultaneously analyze many relationships and include latent constructs in the analysis as a dependent or explanatory variable (Mazzocchi, 2008). These features allow exploring the relationship between variables that cannot be observed directly like attitudes, concerns, and awareness, and that could be in a non-linear relationship. Indeed, it allows to consider both the measurement error associated with unobservable variables and the mutual relations between them. Its applications were extensively adopted also in the food waste domain (Aktas et al., 2018; Hobbs & Goddard, 2015; Katt & Meixner, 2020; Macready et al., 2020; Savelli et al., 2019; Soorani & Ahmadvand, 2019 among others). In addition, SEM is a confirmatory technique, since the specification of the starting model is driven by a pre-existing theory, and data are used to assess if the chosen specification can be confirmed (Mazzocchi, 2008).

The parameters of the model were estimated through maximum likelihood, and as goodness-of-fit measures RMSEA, CFI, TLI, and SMR were computed using the Satorra–Bentler scaled chi-squared statistic to obtain standard errors that are robust to non-normality. All the analyses were performed using Stata 14 software.

4. Results

4.1. Sample characterization

The sample was composed of 39% of men and 61% of women, in line with previous studies related to Italy underlining the predominance of women in managing household food shopping and cooking (Fondazione Censis and Coldiretti, 2010). In line with national average statistics, the average age of respondents was 45.4 years, and half of the sample lived in northern regions (48%), the most hit by the pandemic in the country. Regarding education, nearly 57% of the sample had a high-school degree, while 32% had at least a university bachelor's degree. The average household size was composed of three members, with 39% of families with at least one underage child. Within the sample, 40% of the respondents declared to have worked from home, and 48.8% stated that the domestic workload has increased during the quarantine.

The Cronbach's Alpha test, which registered a value of 0.92, allowed to assess the validity of the sample and the replicability of the analysis.

According to answers provided by respondents, the declared quantities of food waste generated by the Italian households during the quarantine registered a consistent decrease, if compared to the quantity generated before the quarantine. To be more specific, 51.6% of respondents stated that they wasted less food during the quarantine, with respect to the previous period. Then, the categories of food with the highest decrease of declared food waste are flour and yeast (43.2% of respondents), beef (42.8%), white meat (40.7%), and milk (40.4%). These results are in line with those presented by the Italian Waste Watcher Observatory, which also conducted a study on food habits during the quarantine (WasteWatcher-SWG, 2020)

Descriptive statistics were computed then to explore questions related to the main household food waste drivers identified within the MOAU framework. Answers highlighted the presence of differences in behaviors during the quarantine on all the theoretical constructs. Concerning Motivation, impact of restriction measures concerned attitude toward food waste and injunctive social norms. The impact on Opportunity was related to shopping frequency and quantity, while Ability was affected by the restrictive policies from the point of view of increased shop planning and of precision and time dedicated to cooking. Finally, the Uncertainty generated by the restrictive policies was reflected by an increase in the perceived environmental pressure (e.g., being afraid of crowded shops) and by an increase in the average quantity of purchased groceries during each shopping trip. Table 1 summarizes the main results of the survey.

Table 1.

Principal descriptive statistics of change in behaviors during the quarantine.

| Compared to before the quarantine, during the quarantine… | Disagree/Less | Neutral/Just as much | Agree/More |

|---|---|---|---|

| Food Waste | |||

| The food waste produced in the household was… | 51.6% | 40.1% | 8.3% |

| Motivation | |||

| I felt less/more guilty about throwing away food | 5.3% | 57.7% | 37% |

| I thought people in my surroundings found wasting food to be less/just as much/more important | 5.1% | 56% | 38.9% |

| Opportunity | |||

| The shopping frequency was… | 64.1% | 30.5% | 5.4% |

| The food I bought was… | 8.6% | 33.8% | 57.6% |

| I felt too tired to prepare the meal for which I bought the ingredients | 37.8% | 43.8% | 18.4% |

| Ability | |||

| I made use of a shopping list less/more frequently | 15.5% | 37.3% | 47.2% |

| We measured the ingredients during cooking more often | 28.6% | 54.5% | 16.9% |

| We cook less/just as much/more frequently | 6.8% | 34.6% | 58.6% |

| Uncertainty | |||

| I bought more grocery at once for my household per shopping trip | 12.8% | 17.1% | 70.1% |

| I was worried for scarcity of food in supermarkets | 26.1% | 22.3% | 51.5% |

| I was worried about going to the shop too often and being in contact with others | 14.1% | 17.4% | 68.5% |

| I spent less time in the supermarket | 13.3% | 21.6% | 65.1% |

| When out of the store, I realized I had forgotten to buy what I planned | 43.7% | 32.0% | 24.3% |

| Inside the supermarket I moved around according to others' movements | 16.2% | 21.9% | 61.9% |

| We ate at home more often | 6.1% | 28.7% | 65.2% |

Focusing on gender, it appeared of primary importance to carry out a disaggregated analysis of the dataset. Indeed, gender has been proven to be a relevant aspect for the food management and, consequently, for the generation of household food waste, as it is clearly shown by the composition of the sample (39% of men and 61% of women), underlining the more frequent household role of women.

Answers from the survey highlighted the presence of gender-based differences both in declared perceived quantities of food waste generated within the household and in the elements that are at the base of the Opportunity, Ability, and Uncertainty drivers. On the other side, differences based on gender related to Motivation are not statistically significant. Indeed, differences in Opportunity are related to the concern for food security of the household, with women declaring more frequently than men of having bought more food during the quarantine and to having been worried about having enough food at home. On the other side, the share of women who declared themselves as tired to cook is larger than the share of men. Concerning aspects related to Ability, women declared to have paid more attention to planning, food conservation, and precision cooking. Finally, gender-based differences related to Uncertainty are connected to the declared increase of domestic workload and to the increase of the food shopping stress inside supermarkets.

The main gender-based differences are summarized in Table 2 , where the share of women and men answering “agree” or “more” is presented.

Table 2.

Share of “Agree/More” by item and gender.

| Compared to before the quarantine, during the quarantine… | Women | Men | Difference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Food Waste | |||

| The food waste produced in the household has decreased | 53.80% | 48.2% | 5.6% ** |

| Motivation | |||

| I felt more guilty about throwing away food | 37.1% | 36.7% | 0.4% |

| I thought people in my surroundings found wasting food to be more/less important | 39.9% | 37.3% | 2.6% |

| Opportunity | |||

| The shopping frequency has decreased | 70.9% | 53.3% | 17.6%*** |

| The quantity of food I bought was increased | 61.9% | 50.9% | 11.0%*** |

| I wanted to ensure I have enough food in my home, so I stocked up on supplies more than before | 62.0% | 56.7% | 5.3%** |

| I felt less tired to prepare the meal for which I bought the ingredients | 41.5% | 32.0% | 9.5%*** |

| Ability | |||

| I made use of a shopping list more frequently | 49.6% | 43.4% | 6.2%** |

| I paid more attention to storing my food in the right way | 41.5% | 38.3% | 3.2% |

| We measured the ingredients during cooking more often | 29.9% | 26.6% | 3.3%* |

| Uncertainty | |||

| I bought more grocery at once for my household per shopping trip | 74.3% | 63.5% | 10.8%*** |

| I spent less time in the supermarket | 68.9% | 59.3% | 9.6%*** |

| Inside the supermarket I moved around according to others' movements | 65.4% | 56.4% | 9.0%*** |

| The domestic workload has increased | 52.2% | 43.4% | 8.8%*** |

Note: ***1% significance **5% significance *10% significance.

4.2. Structural Equation Model

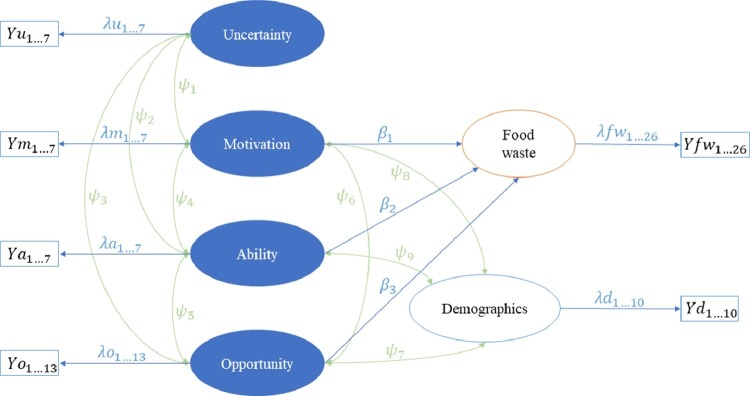

According to the theoretical framework, the confirmatory model considered six latent constructs: Motivation, Ability, Opportunity, Demographics, Uncertainty, and (household) Food Waste. Results are presented in Table 3 and Table 4 and graphically in Fig. 3 .

Table 3.

Latent variables: direct effects and correlations.

| Direct effect | Coefficient | S.E. |

|---|---|---|

| β1 | 0.179 | 0.035 |

| β2 | -0.155 | 0.032 |

| β3 | 0.467 | 0.024 |

| Correlations | Coefficient | S.E. |

| ψ1 | -0.464 | 0.025 |

| ψ2 | 0.526 | 0.025 |

| ψ3 | 0.100 | 0.033 |

| ψ4 | -0.574 | 0.025 |

| ψ5 | 0.247 | 0.026 |

| ψ6 | -0.327 | 0.026 |

| ψ7 | 0.216 | 0.033 |

| ψ8 | -0.119 | 0.028 |

| ψ9 | 0.181 | 0.026 |

Table 4.

SEM coefficients.

| Variable (Y) | Coefficient (λ) | S.E. | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Motivation | |||

| Food waste as potential consequence of stocking supplies | λm1 | 0.124 | 0.024 |

| Aiming to have no unnecessary leftovers | λm2 | -0.249 | 0.026 |

| Feeling guilty about food waste | λm3 | -0.639 | 0.024 |

| Awareness of food waste | λm4 | -0.797 | 0.015 |

| Perceived awareness of food waste of people in my surroundings | λm5 | -0.623 | 0.023 |

| Perceived food waste generated by people in my surroundings | λm6 | -0.319 | 0.027 |

| Opportunity | |||

| Being too tired for cooking | λo1 | 0.717 | 0.143 |

| Unexpected circumstance | λo2 | 0.691 | 0.016 |

| Time pressure | λo3 | 0.663 | 0.174 |

| Actual meals diverging from planning | λo4 | 0.602 | 0.019 |

| Housework stress | λo5 | 0.549 | 0.020 |

| Availability of products in shops | λo6 | 0.511 | 0.017 |

| Accessibility of shops | λo7 | 0.558 | 0.017 |

| Grocery shopping at online supermarkets | λo8 | 0.204 | 0.023 |

| Grocery shopping at online shops | λo9 | 0.230 | 0.022 |

| Grocery shopping at local shops | λo11 | 0.186 | 0.023 |

| Grocery shopping at farms | λo12 | 0.304 | 0.024 |

| Grocery shopping at local marketplaces | λo13 | 0.324 | 0.025 |

| Grocery shopping at supermarket | λo14 | 0.233 | 0.023 |

| Ability | |||

| Planning of menu | λa1 | 0.146 | 0.026 |

| Shopping list | λa2 | 0.268 | 0.025 |

| Precision cooking | λa3 | 0.184 | 0.024 |

| Time on cooking per meal | λa4 | 0.345 | 0.023 |

| Knowledge of the stocks | λa5 | 0.840 | 0.019 |

| Organization of shelves and fridge | λa6 | 0.812 | 0.019 |

| Use of the Mixer | λa7 | 0.092 | 0.024 |

| Uncertainty | |||

| Increased shopping size | λu1 | 0.609 | 0.021 |

| Fear of contact with others inside supermarkets | λu2 | 0.649 | 0.021 |

| Less time spent inside supermarkets | λu3 | 0.499 | 0.023 |

| Avoiding contacts with other inside supermarkets | λu4 | 0.546 | 0.021 |

| Eating home more often | λu5 | -0.297 | 0.025 |

| Forgetting to buy what planned | λu6 | 0.192 | 0.024 |

| Domestic workload | λu7 | 0.205 | 0.024 |

| Demographics | |||

| Region in which the quarantine was spent | λd1 | 0.657 | 0.022 |

| Professional workload during the quarantine | λd2 | 0.728 | 0.021 |

| Education | λd3 | 0.373 | 0.026 |

| Rural/Urban | λd4 | -0.122 | 0.027 |

| Income | λd5 | 0.262 | 0.026 |

| Gender | λd6 | 0.162 | 0.026 |

| Age | λd7 | -0.302 | 0.024 |

| Number of people in the household | λd8 | 0.233 | 0.025 |

| Number of children (0-12 years old) | λd9 | 0.295 | 0.024 |

| Number of children (13-18 years old) | λd10 | 0.148 | 0.025 |

Fig. 3.

the MOAU model.

The direct causal link between two variables is represented by a one-way arrow, oriented from the independent to the dependent one. Motivation, Ability, Opportunity have this type of connection with Food Waste. Association (covariance, correlation) between variables without a causal interpretation is represented by a two-way arrow that links the variables with an arc line. Uncertainty and Demographics have this type of connection with each Motivation, Ability, and Opportunity. The same holds for Motivation, Ability, and Opportunity with each other.

Uncertainty affects Food Waste only indirectly through its effects on Motivation, Opportunity, and Ability constructs. Demographics as well, affect Food Waste through the mediating role of the MOAU's drivers.

Factor analysis was used to exploit the correlations between observed variables to verify the presence of a smaller set of new “artificial” (latent) variables that can be expressed as a combination of the original ones. The higher the correlation across the original variables, the smaller is the number of components needed to describe the phenomenon. In order to identify the most significant variables and to reduce the complexity for the construction of the confirmatory SEM, an exploratory factor analysis was conducted on the dataset. A significant value of the Bartlett's Test ensured the reliability of the factor analysis: describing a degree of uncorrelation sufficient to perform a factor analysis. Also, the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin Measure of Sampling Adequacy was significant (0.95), indicating shared variance between variables. A pattern matrix was conducted to assess the number of factors that better describe data variance and the relevance of each variable. The analysis of the pattern matrix led to the identification of 38 variables and 7 potential factors with an eigenvalue greater than 1, retained on the base of the Kaiser criterion (Kaiser 1960), explaining the 88.6% of the total variance of the sample.

In Fig. 3 coefficients are reported next to the arrows and the observable variables are omitted to reduce complexity.

Table 3 and 4 represent, respectively, estimations of coefficients for latent and observable variables, with the standardized coefficients for the verified model.

To assess the fitness of the model, the corrections to the standard fit measures proposed by Satorra-Bentler (Satorra and Bentler, 1994) has been considered in order to relax the normality assumption for latent and observed variables. The model presents a value of the adjusted Comparative Fit Index (SB-CFI) and for the adjusted Tucker-Lewis Index (SB-TLI), respectively, of 0.841 and 0.835. Moreover, a value of 0.043 is registered for the Satorra-Bentler adjusted Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA), and a value of 0.066 for the Standardized Root Mean Squared Residuals (SRMR). Therefore, the model generally shows a good fit to the data, establishing the validity of the conceptual model and the reliability of the measures. This is confirmed especially by the value of the SRMR index (lower than 0.8), since this index is not affected by χ2 value and, consequently, by the complexity of the model, being biased only for small samples with low degrees of freedom (Hu and Bentler, 1999).

Standardized coefficients for the latent constructs show that results are consistent with the theoretical framework, as shown in Table 3. Motivation is positively related to Food Waste since, as previously discussed, the questions tackling demotivational aspects of social norms suggests that highest is the demotivation, highest is the amount of food waste generated. Ability instead has a negative relationship with Food Waste, meaning that an increase in the individual capacity to cook precisely is consistently associated with a decrease in household food waste. Finally, Opportunity is also positively correlated to the outcome variable, suggesting that increasing shopping frequencies and food purchases can boost household food waste.

As represented in Table 3, the model also supports the hypothesis that Uncertainty is associated with the behavioral drivers as it shows significant coefficients as well. Uncertainty indeed is positively correlated for Ability and Opportunity, and negatively correlated with (de)Motivation. Results suggest that Uncertainty is fostering already existing patterns and dynamics.

5. Discussion and policy implications

5.1. Discussion

Results from the Structural Equation Model confirm the validity of the MOAU framework in explaining the behavioral drivers of household food waste. The framework provides insights on the structure of these drivers and on their impact on the food waste generation at the household level.

Results emphasize Opportunity as a major mitigation factor, as it has the strongest relation with household food waste generation (β3=0.467). In addition, Opportunity is related to behaviours that, apparently, were the most affected by the COVID-19 restrictions and generated a positive spill over on food waste reduction. Namely, behaviours related to the Opportunity construct include the perceived availability of time to be dedicated to cooking (Yo1, Yo3), the accessibility to shops and the availability of food in stores (Yo6, Yo7), the increased frequency of shopping (Yo8-Yo13), the amount of stress and fatigue due to the COVID-19-related restrictions (Yo1, Yo5), and the occurrence of unforeseen events (Yo2, Yo4).

The magnitude of the impact of Motivation and Ability constructs, while being direct, is lower with respect to the Opportunity ones (β1=0.179 and β2=-0.155). Motivation includes household awareness of the consequences of food waste (Ym1, Ym2, Ym3, Ym4) and the impact of social norms (Ym5, Ym6). Ability is related to planning (Ya1, Ya2), precision cooking (Ya3), capability to dedicate time to cooking (Ya4), awareness of food stock (Ya5, Ya6), and ability to use uncommon kitchen tools (Ya7).

Time emerged as an important resource, stimulating households to allocate more attention to food planning, preparation, and conservation and therefore contributing significantly to the reduction of food waste. In particular, time availability has a significant impact for both Opportunity and Ability. More specifically, time influences Opportunity through the actual and perceived availability of time to dedicate to cooking (Yo1, Yo3). Then, the influence of time on the Ability construct is connected to the amount of time dedicated to the preparation of the single meals (Ya4), that is considered as a an indicator of the individual capacity to exploit the opportunity related to the perceived amount of time to dedicate to cooking activities. This is particularly important considering that Opportunity is positively influencing Ability: having more time allows individuals to invest in knowledge, improving their planning, storage, and cooking skills. Basing on a similar mechanism, a positive relation also links Opportunity and Motivation.

Considering the constructs with an indirect impact on generated food waste, Demographics influences food waste generation through professional workload (Yd2), working location (Yd1), age, gender, income, and household composition, in particular by the presence of children. In addition, the typology of city of residence (Yd4) has an impact on the latent construct, being the dimension of the city inversely proportional to the quantity of generated food waste.

Finally, the environmental pressure inside shops and the fear to being in contact with others (Yu2-4), and the increase of domestic workload (Yu7) are the elements defining the Uncertainty latent construct.

5.2. Policy implications

To some extent the mix of measures adopted in Italy between March and May 2020 reproduced the situation of a natural experiment were control conditions (introduced restrictions) forced specific changes in individual behaviors. Restrictions flattened several food habits, for instance forcing households to organize and consume all their meals at home. Such conditions allowed to isolate individual behaviors and to analyze the effects of the measures introduced during this period.

Results confirmed that social distancing and quarantine measures introduced by the Italian Government were associated with a high level of uncertainty among consumers and carried a significant impact on their behavior and livelihood strategies. These changes in food purchasing, management, and disposal, as well as the decrease of self-declared quantities of household food waste, suggest several potential policy implications.

Regarding changes in habits, interviewed consumers declared a decrease in shopping frequency, balanced by an increase in the quantity of food purchased for each shopping trip. These changes are positively related to food waste. On the other hand, restrictions on freedom of movement allowed consumers to spend a greater amount of time on activities related to food, like cooking, planning, and organizing their stocks. These aspects are negatively related to food waste and had a primary role in the declared reduction of the quantity of food thrown away during the quarantine. Since the amount of self-declared food waste has decreased, it can be assumed that the second group of behaviors has overcome the first: the changes driven by the increased sense of uncertainty produced a positive effect on the improvement of specific routines as planning, storing, and preparing. The increased amount of purchased food was compensated by a greater care in its treatment.

For these reasons, policy interventions might pay more attention to stimulating the improvement of food (and leftovers) management at home, also facilitating a shift towards the use of smart kitchen appliances, potentially nudging precision shopping and cooking. The development of smart kitchen solutions, including washable and potentially pick-up and refillable containers from shops, also aimed at the reduction of food waste, should be incentivized. Indeed, households should be encouraged to not abandoning the sustainable and positive behaviors they adopted during the quarantine. Precision shopping and cooking should be stimulated with tailored measures since they could lead to the growth of new commercial activities, halfway between deli and take-away restaurants, in which to buy single or semi-finished ingredients in order to maintain the experience of self-preparation but saving time and buying only what needed.

Interventions addressing consumer awareness have been often general and passive, failing to target specific drivers and engage specific citizen groups (van Geffen et al., 2020a). Also, the present work suggests that Motivation plays a rather limited role in stimulating food waste prevention and reduction if it is not coupled with Ability and Opportunity. Building on these results, awareness campaigns might be designed to contribute directly to capacity development, or opportunity creation, to engage citizens in a more active manner. New practices, solutions and tools might be created for specific citizen groups, considering their different habits and attitudes, thus becoming an integral part of food preparation and consumption, eventually including a gratification as additional stimulus.

Finally, improving household food management and consumers’ engagement in food waste reduction could also have positive effects on the coping with future unforeseen negative events. Public institutions should try to anticipate signals of crisis and do not underestimate early signals, with the aim to prepare the system to cope with the crisis. At a broader level emergency plans should be designed to improve the resilience of the food supply chain, in particular to prevent shortages due to sudden peaks in food demand. Also, institutional communication especially in time of crisis, should avoid exacerbating irrational behaviors driven by fear like panic buying.

6. Conclusions

Building on a nationally representative survey, this work investigated the impact of the exogenous shock generated by the outbreak of COVID-19 on the main behavioral drivers of household food waste. Compared to other works based on viral surveys and convenience samples, the dataset collected for this work has a higher explanatory capacity allowing more solid generalizations. Questions were tailored to the MOA framework and designed to capture the perceived differences in behaviors during the quarantine in comparison with the previous period. Moreover, an extension of the MOA framework was proposed to explore the role of Uncertainty on food waste generation and validated through a confirmatory Structural Equations Model.

From this work, several conclusions can be drawn. First, despite some initial concerns about a potential increase in food waste levels, results emphasized a significant reduction in declared quantities of generated household food waste by Italian households. In fact, the majority of respondents declared they wasted less food during the lockdown of March-May 2020. Apparently, Uncertainty and increased availability of time at home positively contributed to the reduction of household food waste.

Second, the analysis of the distributions of the answers highlighted several shifts in consumers’ behavior related to food waste drivers (Motivation, Opportunity, Ability, and Uncertainty constructs), with differences between genders. Shifts in drivers related to the Motivation constructs are referred to an increased declared concern and awareness for the consequences of food waste. Major changes in drivers belonging to Opportunity construct are related to a decrease in shopping frequencies, balanced by an increase in the quantity of food purchased per each shopping trip, and to the perceived availability of time that can be dedicated to kitchen activities. Changes in Ability related drivers are expressed by an increased attention to the planning of food shopping and to the actual time dedicated to cooking. The most relevant shifts in drivers belonging to Uncertainty construct are directly related to the health risks caused by the COVID-19. Moreover, the severe measures adopted to mitigate the impact of the pandemic and their progressive implementation over time contributed to increasing the insecurity related to the food security of consumers and their households. The combination of all those elements forced consumers to change their behavior and to adopt different livelihood strategies. Gender differences have a significant impact on those shifts: women declared more pronounced changes in behaviors and habits related to the drivers belonging to the Opportunity, Ability, and Uncertainty constructs, while no significant differences were found for the components of the Motivation construct. This could be related to a persistent greater female involvement in the management of food in Italian households.

Third, results from the Structural Equations Model highlight that the latent constructs of the MOAU model can have either a direct or an indirect impact on the generation of household food waste. Concerning constructs with direct relation during the quarantine, Opportunity proved to have the most relevant direct influence on household food waste, while the magnitude of Motivation and Ability constructs being significant is lower. Time also proved to have a consistent impact on the generation of household food waste, both in terms of Opportunity and Ability. Concerning Opportunity, the availability of time to be dedicated to food-related activities proved to be a significant element of the construct. Time was consistent also for the Ability construct, since the increase of the actual amount of time dedicated to cooking activities proved to be significant. Apparently, a higher availability of time resulted in an increase of cure time, which stimulates the adoption of sustainable behaviors and more in particular of practices addressing food waste reduction. Significant correlations have been found among the Motivation, Opportunity, and Ability constructs. Those correlations highlight, among others, the positive relation between Opportunity and Ability, showing that the “cooperation” between those two constructs can have positive effects on the reduction of household food waste. Uncertainty and the socio-demographic characteristics of the respondents were proven to have an indirect effect on the generation of household food waste, affecting Motivation, Opportunity, and Ability constructs. Uncertainty showed to have a “reinforcement” effect on the other constructs, consolidating already existing behavioral patterns. To conclude, the impact of Uncertainty resulted in being significant on MOA constructs suggesting that its integration to the framework could help to take into consideration and explain the role of exogenous factors and unforeseen events. In this sense, the Motivation-Opportunity-Ability framework (MOA) could be extended in the Motivation-Opportunity-Ability -Uncertainty framework (MOAU).

This study has some limitations that should be considered and can inspire future research. In particular, as most of the studies based on self-reported surveys, results could suffer from cognitive bias. Despite the weakness of self-reporting emphasized in Section 2, the use of computer-assisted web interviewing method represented the most efficient and safe option to overcome some of the barriers posed by the COVID-19 situation.

At the same time, while a growing body of scientific literature on COVID-19 impacts is emerging, most of the contributions focus on the quantification of food losses and waste (Amicarelli and Bux, 2021; Principato et al., 2020; Vittuari et al., 2021) or on the systemic consequences on the food systems as a whole (Aldaco et al., 2020), with only limited studies on the impact of Uncertainty and external shocks on food waste generation.

Future research should therefore consider investigating this link, ideally based on repeated measurements over time in order to be able to map the dynamic effects and the changes over time of what is perceived and what is declared. This approach, in addition of providing a better understanding of the effects of external shocks, can lead to the identification of policy objectives that link unexpected positive consequences (e.g. food waste reduction) with the adoption of new behaviours targeting more sustainable consumption patterns. Indeed, this research contributes to the wider debate on the impact of the consequences of COVID-19 pandemic on the resilience of food systems, the management and disposal of waste and, more in general, the long-term sustainability of the food supply chain (Aldaco et al., 2020; Ibn-Mohammed et al., 2021; Mohammad et al., 2021; Vanapalli et al., 2021). Finally, further research might focus on the long-term impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on food related habits and behaviors. In other sanitary crisis as the “mad-cow disease” outbreak of 1996, the constant perception of risks for new negative events generated long-term changes in beef consumption levels that remained under the pre-crisis levels for a long period. (Beardsworth and Keil, 2002; Jin, 2003; Setbon et al., 2005). The asymmetric recovery of food consumption patterns could therefore represent a long-term outcome of COVID-19 crisis that could be worth of further investigations.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Matteo Vittuari: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – original draft. Matteo Masotti: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – original draft. Elisa Iori: Methodology, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft. Luca Falasconi: Writing – review & editing. Tullia Gallina Toschi: Writing – review & editing. Andrea Segrè: Writing – review & editing, Supervision.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgment

The questionnaire developed within this article was inspired by the work conducted within the H2020 project REFRESH and designed jointly with a research unit of the Wageningen Food & Bio-based Research working on the project “Food waste in times of Corona” funded by The Netherlands Nutrition Centre Foundation. Although a common basis the Dutch and the Italian version of the questionnaire were adjusted to respond to the specific characteristics of the Dutch and Italian national contexts.

Footnotes

Tests for equivalency to national average were performed but not presented for clarity purposes.

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.resconrec.2021.105815.

Appendix A

Table A4.

Restrictions introduced by the Italian Government during the COVID-19 health crisis.

| Date | General provision | Implication on Food Chain |

|---|---|---|

| Jan 31 | Declaration of “Emergency state” for 6 months | None |

| Feb 23 | First restrictions to movements in the areas of the outbreak (“red zones” in Lombardia and Veneto regions). Stop public mass gatherings. | In the “Red Zones”:

|

| Feb 25 | Restrictions for Emilia-Romagna, Friuli-Venezia Giulia, Lombardia, Veneto, Liguria, and Piemonte regions:

|

|

| Mar 1 | Tightening of restrictions for specific areas:

|

|

| Mar 4 | Closure of all schools and Universities. |

|

| Mar 8 | Lockdown of Lombardia and other 14 provinces (5 in Emilia-Romagna, 5 in Piemonte, 3 in Veneto e 1 in Marche). |

|

| Mar 10 | General lockdown of Italy:

|

|

| Mar 20 | Tightening restrictions to freedom of movement:

|

|

| May 4 | Release of some restrictions to freedom of movement. |

|

| May 18 | End of restrictions to freedom of movement. |

|

Appendix B. Supplementary materials

References

- Ajzen I. Consumer attitudes and behavior: the theory of planned behavior applied to food consumption decisions. Riv. di Econ. Agrar. 2015;70:121–138. doi: 10.13128/REA-18003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991;50:179–211. doi: 10.1016/0749-5978(91)90020-T. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Aktas E., Sahin H., Topaloglu Z., Oledinma A., Huda A.K.S., Irani Z., Sharif A.M., van't Wout T., Kamrava M. A consumer behavioural approach to food waste. J. Enterp. Inf. Manag. 2018;31:658–673. doi: 10.1108/JEIM-03-2018-0051. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Aldaco R., Hoehn D., Laso J., Margallo M., Ruiz-Salmón J., Cristobal J., Kahhat R., Villanueva-Rey P., Bala A., Batlle-Bayer L., Fullana-i-Palmer P., Irabien A., Vazquez-Rowe I. Food waste management during the COVID-19 outbreak: a holistic climate, economic and nutritional approach. Sci. Total Environ. 2020;742 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.140524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amicarelli V., Bux C. Food waste in Italian households during the Covid-19 pandemic: a self-reporting approach. Food Secur. 2021;13:25–37. doi: 10.1007/s12571-020-01121-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beardsworth A., Keil T. Sociology on the Menu. 2002. Sociology on the Menu. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bravi L., Francioni B., Murmura F., Savelli E. Factors affecting household food waste among young consumers and actions to prevent it. A comparison among UK, Spain and Italy. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2020;153 doi: 10.1016/j.resconrec.2019.104586. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Canali M., Amani P., Aramyan L., Gheoldus M., Moates G., Östergren K., Silvennoinen K., Waldron K., Vittuari M. Food Waste Drivers in Europe, from Identification to Possible Interventions. Sustainability. 2016;9:37. doi: 10.3390/su9010037. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cialdini R.B., Kallgren C.A., Reno R.R. 1991. A Focus Theory of Normative Conduct: A Theoretical Refinement and Reevaluation of the Role of Norms in Human Behavior. [Google Scholar]

- de Hooge I.E., van Dulm E., van Trijp H.C.M. Cosmetic specifications in the food waste issue: supply chain considerations and practices concerning suboptimal food products. J. Clean. Prod. 2018;183:698–709. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.02.132. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- EU . 2020. Coronavirus Pandemic in The EU - Fundamental Rights Implications, FRA - European Union Agency For Fundamental Rights. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- European Commission . DG SANTE/Unit ‘Food Inf. Compos. Food Waste. 2020. Farm to fork strategy. [Google Scholar]

- Fondazione Censis, Coldiretti, 2010. Primo rapporto sulle abitudini alimentari degli italiani 1–27.

- Galanakis C.M. The food systems in the era of the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic crisis. Foods. 2020;9:523. doi: 10.3390/foods9040523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geithner T. 2003. Fund Assistance for Countries Facing Exogenous Shocks. [Google Scholar]

- George R.M., Burgess P.J., Thorn R.D. 2010. Reducing Food Waste Through the Chill Chain 95. [Google Scholar]

- Giordano C., Alboni F., Falasconi L. Quantities, determinants, and awareness of households’ food waste in Italy: a comparison between diary and questionnaires quantities. Sustainability. 2019;11:3381. doi: 10.3390/su11123381. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Graham-Rowe E., Jessop D.C., Sparks P. Predicting household food waste reduction using an extended theory of planned behaviour. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2015;101:194–202. doi: 10.1016/j.resconrec.2015.05.020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Grainger M.J., Aramyan L., Logatcheva K., Piras S., Righi S., Setti M., Vittuari M., Stewart G.B. The use of systems models to identify food waste drivers. Glob. Food Sec. 2018;16:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.gfs.2017.12.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hale, T., Angrist, N., Kira, B., Petherick, A., Phillips, T., Webster, S., 2020. Variation in government responses to COVID-19 | Blavatnik School of Government. Work. Pap.

- Hebrok M., Boks C. Household food waste: drivers and potential intervention points for design – an extensive review. J. Clean. Prod. 2017;151:380–392. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2017.03.069. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hobbs J.E., Goddard E. Consumers and trust. Food Policy. 2015;52:71–74. doi: 10.1016/j.foodpol.2014.10.017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hu L., Bentler P.M. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. A Multidiscip. J. 1999;6:1–55. doi: 10.1080/10705519909540118. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ibn-Mohammed T., Mustapha K.B., Godsell J., Adamu Z., Babatunde K.A., Akintade D.D., Acquaye A., Fujii H., Ndiaye M.M., Yamoah F.A., Koh S.C.L. A critical review of the impacts of COVID-19 on the global economy and ecosystems and opportunities for circular economy strategies. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2021;164 doi: 10.1016/j.resconrec.2020.105169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin H.J. The effect of the BSE outbreak in Japan on consumers’ preferences. Eur. Rev. Agric. Econ. 2003;30:173–192. doi: 10.1093/erae/30.2.173. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kahneman D., Tversky A. Prospect theory: an analysis of decision under risk. Econometrica. 1979;47:263. doi: 10.2307/1914185. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Katajajuuri J.-M., Silvennoinen K., Hartikainen H., Jalkanen L., Koivupuro H.-K., Reinikainen A. 8th International Conference on Life Cycle Analysis, 1-4 October, Saint- Malo, France. 2012. Food waste in the food chain and related climate impacts. [Google Scholar]

- Katt F., Meixner O. Food waste prevention behavior in the context of hedonic and utilitarian shopping value. J. Clean. Prod. 2020;273 doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.122878. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lapinski, M.K., Rimal, R.N., 2005. An Explication of Social Norms 127–147.

- MacInnis D.J., Moorman C., Jaworski B.J. Enhancing and measuring consumers’ motivation, opportunity, and ability to process brand information from Ads. J. Mark. 1991;55:32. doi: 10.2307/1251955. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Macready A.L., Hieke S., Klimczuk-Kochańska M., Szumiał S., Vranken L., Grunert K.G. Consumer trust in the food value chain and its impact on consumer confidence: a model for assessing consumer trust and evidence from a 5-country study in Europe. Food Policy. 2020;92 doi: 10.1016/j.foodpol.2020.101880. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mazzocchi M. SAGE Publications Ltd; United Kingdom: 2008. Statistics for Marketing and Consumer Research, Statistics for Marketing and Consumer Research. 1 Oliver's Yard, 55 City Road, London EC1Y 1SP. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mehner E., Naidoo A., Hellwig C., Bolton K., Rousta K. The influence of user-adapted, instructive information on participation in a recycling scheme: a case study in a medium-sized swedish city. Recycling. 2020;5:7. doi: 10.3390/recycling5020007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mohammad A., Goli V.S.N.S., Singh D.N. Discussion on ‘Challenges, opportunities, and innovations for effective solid waste management during and post COVID-19 pandemic, by Sharma et al. (2020).’. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2021;164 doi: 10.1016/j.resconrec.2020.105175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neff R.A., Spiker M., Rice C., Schklair A., Greenberg S., Leib E.B. Misunderstood food date labels and reported food discards: a survey of U.S. consumer attitudes and behaviors. Waste Manag. 2019;86:123–132. doi: 10.1016/J.WASMAN.2019.01.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- OECD . 2020. Food Supply Chains and COVID-19: Impacts and Policy Lessons; pp. 1–11. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Parizeau K., von Massow M., Martin R. Household-level dynamics of food waste production and related beliefs, attitudes, and behaviours in Guelph, Ontario. Waste Manag. 2015;35:207–217. doi: 10.1016/j.wasman.2014.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pott, A., 2020. Oxford COVID-19 Government Response Tracker Regional report - Europe and Central Asia Oxford COVID-19 Government Response Tracker Regional report - Europe and Central Asia. Work. Pap.

- Principato L., Secondi L., Cicatiello C., Mattia G. Caring more about food: The unexpected positive effect of the Covid-19 lockdown on household food management and waste. Socioecon. Plann. Sci. 2020;100953 doi: 10.1016/j.seps.2020.100953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quested T., Parry A. 2017. Household Food Waste in the UK, 2015, Wrap. [Google Scholar]

- Quested T.E., Marsh E., Stunell D., Parry A.D. Spaghetti soup: The complex world of food waste behaviours. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2013;79:43–51. doi: 10.1016/j.resconrec.2013.04.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Quested T.E., Palmer G., Moreno L.C., McDermott C., Schumacher K. Comparing diaries and waste compositional analysis for measuring food waste in the home. J. Clean. Prod. 2020;262 doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.121263. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rizou M., Galanakis I.M., Aldawoud T.M.S., Galanakis C.M. Safety of foods, food supply chain and environment within the COVID-19 pandemic. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2020;102:293–299. doi: 10.1016/j.tifs.2020.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roe B.E., Bender K., Qi D. The impact of COVID-19 on consumer food waste. Appl. Econ. Perspect. Policy. 2021;43:401–411. doi: 10.1002/aepp.13079. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rothschild M.L. Carrots, sticks, and promises: a conceptual framework for the management of public health and social issue behaviors. J. Mark. 1999;63:24. doi: 10.2307/1251972. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Satorra A., Bentler P.M. Latent Variables Analysis: Applications for Developmental Research. Sage Publications, Inc; Thousand Oaks, CA, US: 1994. Corrections to test statistics and standard errors in covariance structure analysis; pp. 399–419. [Google Scholar]

- Savelli E., Francioni B., Curina I. Healthy lifestyle and food waste behavior. J. Consum. Mark. 2019;37:148–159. doi: 10.1108/JCM-10-2018-2890. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Secondi L. Expiry dates, consumer behavior, and food waste: how would Italian consumers react if there were no longer “best before” labels? Sustainability. 2019;11:6821. doi: 10.3390/su11236821. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Setbon M., Raude J., Fischler C., Flahault A. Risk perception of the “mad cow disease” in France: determinants and consequences. Risk Anal. 2005;25:813–826. doi: 10.1111/j.1539-6924.2005.00634.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Setti M., Banchelli F., Falasconi L., Segrè A., Vittuari M. Consumers’ food cycle and household waste. When behaviors matter. J. Clean. Prod. 2018;185:694–706. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.03.024. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Silvennoinen K., Katajajuuri J.M., Hartikainen H., Jalkanen L., Koivupuro H.K., Reinikainen A. 2012. Food Waste Volume and Composition in the Finnish Supply Chain: Special Focus on Food Service Sector; pp. 12–15. [Google Scholar]

- Singh S., Kumar R., Panchal R., Tiwari M.K. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2020. Impact of COVID-19 on logistics systems and disruptions in food supply chain; pp. 1–16. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Smith T.A., Landry C.E. Household Food Waste and Inefficiencies in Food Production. Am. J. Agric. Econ. ajae. 2020;12145 doi: 10.1111/ajae.12145. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Soorani F., Ahmadvand M. Determinants of consumers’ food management behavior: applying and extending the theory of planned behavior. Waste Manag. 2019;98:151–159. doi: 10.1016/j.wasman.2019.08.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stancu V., Haugaard P., Lähteenmäki L. Determinants of consumer food waste behaviour: two routes to food waste. Appetite. 2016;96:7–17. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2015.08.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stenmarck Å., Jensen C., Quested T., Moates G. 2016. Fusions: Estimates of European food waste levels. [Google Scholar]

- Stern P.C. New environmental theories: toward a coherent theory of environmentally significant behavior. J. Soc. Issues. 2000;56:407–424. doi: 10.1111/0022-4537.00175. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stern P.C. Information, incentives, and proenvironmental consumer behavior. J. Consum. Policy. 1999;22:461–478. doi: 10.1023/A:1006211709570. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tversky A., Fox C.R. Weighing risk and uncertainty. Psychol. Rev. 1995;102:269–283. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.102.2.269. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tversky A., Kahneman D. Advances in prospect theory: cumulative representation of uncertainty. J. Risk Uncertain. 1992;5:297–323. doi: 10.1007/BF00122574. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- UN General Assembly . 2015. Transforming our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, Ransforming our World : the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. [Google Scholar]

- Van Garde S.J., Woodburn M.J. Food discard practices of householders. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 1987;87:322–329. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Geffen L., van Herpen E., Sijtsema S., van Trijp H. Food waste as the consequence of competing motivations, lack of opportunities, and insufficient abilities. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. X. 2020;5 doi: 10.1016/j.rcrx.2019.100026. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- van Geffen L., van Herpen E., van Trijp H. Food Waste Management. Springer International Publishing; Cham: 2020. Household food waste—how to avoid it? An integrative review; pp. 27–55. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- van Geffen L., Van Herpen E., van Trijp H. Causes & determinants of consumers food waste. Eurefresh.Org. 2016;20:26. [Google Scholar]

- Vanapalli K.R., Sharma H.B., Ranjan V.P., Samal B., Bhattacharya J., Dubey B.K., Goel S. Challenges and strategies for effective plastic waste management during and post COVID-19 pandemic. Sci. Total Environ. 2021;750 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.141514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vittuari M., Bazzocchi G., Blasioli S., Cirone F., Maggio A., Orsini F., Penca J., Petruzzelli M., Specht K., Amghar S., Atanasov A.-M., Bastia T., Bertocchi I., Coudard A., Crepaldi A., Curtis A., Fox-Kämper R., Gheorghica A.E., Lelièvre A., Muñoz P., Nolde E., Pascual-Fernández J., Pennisi G., Pölling B., Reynaud-Desmet L., Righini I., Rouphael Y., Saint-Ges V., Samoggia A., Shaystej S., da Silva M., Toboso Chavero S., Tonini P., Trušnovec G., Vidmar B.L., Villalba G., De Menna F. Envisioning the future of European food systems: approaches and research priorities after COVID-19. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2021;5 doi: 10.3389/fsufs.2021.642787. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vittuari M., Falasconi L., Masotti M., Piras S., Segrè A., Setti M. Not in my bin’: consumer's understanding and concern of food waste effects and mitigating factors. Sustainability. 2020;12:5685. doi: 10.3390/su12145685. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- WasteWatcher-SWG, 2020. #IoRestoaCasa, report. 2020 [WWW Document]. URL https://www.sprecozero.it/2020/05/14/italiani-e-cibo-in-tempo-di-lockdown-iorestoacasa-e-spreco-meno-i-dati-del-rapporto-waste-watcher-allalba-della-fase-2/(accessed 5.25.20).

- WRAP, French-Brooks, J. Wrap. 2012. Reducing supply chain and consumer potato waste; pp. 10–47. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.