Abstract

Background

Out of School Hours Care (OSHC) offers structured care to elementary/primary-aged children before and after school, and during school holidays. The promotion of physical activity in OSHC is important for childhood obesity prevention. The aim of this systematic review was to identify correlates of objectively measured physical activity and sedentary behaviour in before and after school care.

Methods

A systematic search was conducted in Scopus, ERIC, MEDLINE (EBSCO), PsycINFO and Web of Science databases up to December 2021. Study inclusion criteria were: written in English; from a peer-reviewed journal; data from a centre-based before and/or after school care service; children with a mean age < 13 years; an objective measure of physical activity or sedentary behaviour; reported correlations and significance levels; and if an intervention study design these correlates were reported at baseline. Study quality was assessed using the Office of Health Assessment and Translation Risk of Bias Rating Tool for Human and Animal Studies. The PRISMA guidelines informed the reporting, and data were synthesised according to shared correlations and a social ecological framework.

Results

Database searches identified 4559 papers, with 18 cross-sectional studies meeting the inclusion criteria.There were a total of 116 physical activity correlates and 64 sedentary behaviour correlates identified. The most frequently reported correlates of physical activity were child sex (males more active), staff engaging in physical activity, an absence of elimination games, and scheduling physical activity in daily programming (all more positively associated). The most frequently reported correlates of sedentary behaviour were child sex (females more sedentary) and age (older children more sedentary).

Conclusions

Encouraging physical activity engagement of female children, promoting positive staff behaviours, removing elimination elements from games, and scheduling more time for physical activity should be priorities for service providers. Additional research is needed in before school care services.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12889-022-14675-8.

Keywords: Out of school hours care, After school program, Before school care, Physical activity, Sedentary behaviour, Review

Background

Childhood overweight and obesity is a critical public health issue [1]. Recent global estimates indicate that over 18% of children and adolescents aged 5–19 years have overweight or obesity, compared with just 4% in 1975 [2]. The World Health Organization [3] attributes the increased prevalence of childhood obesity to a global shift in diets towards energy-dense, nutrient-poor foods; and a trend towards less physical activity (PA) due to increasingly sedentary lifestyles. Managing childhood overweight and obesity will require population-based, multi-sectoral and multi-disciplinary approaches [3].

A setting which provides an opportunity for an environmental level approach to childhood overweight and obesity is Out of School Hours Care (OSHC). OSHC offers care to elementary/primary-aged children before and after school, and during school holidays, with an average of 29% of children aged 6 to 11 years across Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries attending centre-based before and/or after school care services [4].

While OSHC services can have a positive impact on the PA and healthy eating of children through active play and the provision of healthy snacks [5, 6], childhood obesity interventions in OSHC settings have been mixed and generally ineffective in reducing child obesity (e.g. body mass index (BMI), body composition, cardiovascular fitness) [7]. A review of obesity interventions in after school care services found many interventions were focussed on increasing PA but not on reducing sedentary activities [7]. Reducing sedentary behaviour is important given its association with several adverse health outcomes [8]. To the authors’ knowledge, no reviews have systematically looked at factors that are associated with child PA and sedentary behaviour while attending OSHC services. Understanding the influences on and thus, potential, causes of PA behaviours has been widely identified as important for evidence-based planning of public health interventions [9].

The aim of this systematic review was to identify correlates of objectively measured PA and sedentary behaviour in before and after school care. While vacation care, such as summer camps, is considered an OSHC service, this review included only before and after school care, given the differences in programming and delivery compared with vacation care. Consistent with other reviews of PA and sedentary behaviour in children [10–12] a social ecological framework was used in correlate categorisation to provide an organised multilevel approach to help inform future interventions in the OSHC setting [13].

Methods

The reporting of this review followed the 2020 Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analysis (PRISMA) statement [14]. The review was registered with the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO) in April 2020 (CRD42020135814). A systematic review was conducted as a meta-analysis was not feasible due to the considerable heterogeneity among study outcome measures.

Search strategy

A systematic search was conducted with five scientific databases- Scopus, ERIC, MEDLINE (EBSCO), PsycINFO and Web of Science. Databases were searched from their inception to December 2021. Search terms were developed to capture all variations of the terminology related to before and after school programs as countries globally have varying names for the services. The initial search terms used were “out of school hours care” OR “outside school hours care” OR “out of school time program*” OR “after school care” OR “after school program*” OR “before school care” OR “before school program*” OR “breakfast club*” OR “after school club*” OR “wrap around care”; AND “healthy eating” OR food* OR nutrit* OR diet* OR “physical activity” OR movement OR exercise* OR sedentary OR sitting. These terms were tested for feasibility with Scopus before they were used in all databases. Nutrition related search terms were included as initially this review was also looking at healthy eating behaviours in OSHC services, however, only one study met the inclusion criteria. Consequently, we focused solely on PA and sedentary behaviours and excluded the healthy eating study.

Search records were extracted from the databases and imported into Endnote referencing software [15], where duplicate records were removed. Screening was conducted by multiple authors to reduce the risk of rejecting relevant articles [14]. Four independent reviewers screened the titles and abstracts of records against the eligibility criteria (AW, RC, LP, SR). Full text versions of studies meeting the criteria in initial screening were retrieved and assessed for final inclusion by three independent reviewers (AW, SR, LP), and their reference lists were manually searched to identify any additional relevant literature (AW). References found from the manual search also had the inclusion and exclusion criteria applied to determine relevance. Any discrepancies were resolved by discussion between reviewers, with an independent reviewer available for consultation if necessary (AO).

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Articles were included if they were: (1) written in the English language; (2) from a peer-reviewed academic journal; (3) contained data from a centre-based before and/or after school care service; (4) had a sample population of children with a mean age under 13 years (elementary/primary school age); (5) contained an objective measure of physical activity or sedentary behaviour; and (6) reported correlations or associations between the objective measure and other demographic, environmental, contextual or behavioural variables; and reported statistical significance (p value) of these correlations. Intervention studies reporting correlates at baseline would be eligible, however none did so they were excluded. Reviews, conference proceedings, dissertations and non-scholarly sources were also excluded from the review.

Consistent with other reviews of PA and sedentary behaviour correlates in children [8, 11], studies were required to have an objective measure of PA or sedentary behaviour. Physical activity is a complex behaviour, and research has demonstrated objective measures as more precise compared to subjective measures [16], particularly among children where issues with recall accuracy can arise [17]. Commonly used objective measurement tools reviewers were looking for were wearable monitors, indirect calorimetry and direct observation. Variables associated with the objective measure could be reported with both subjective or objective measures; in this way any contextual information captured by the subjective methods was included.

Study risk of bias assessment

Individual study risk of bias was assessed by two independent authors (AW, SR) using the Office of Health Assessment and Translation (OHAT) Risk of Bias Rating Tool for Human and Animal Studies [18]. This tool assesses the risk of bias at the outcome level and rates cross-sectional studies using seven questions covering six types of bias: selection, confounding, attrition/exclusion, detection, selective reporting, and other. The risk of bias for each question was considered as definitely low, probably low, probably high and definitely high risk of bias. Initial review agreement between the two authors was low, at an agreement score of 47%. Most of the differences were between whether a criterion was ‘definitely low’ or ‘probably low’, and following a mutual discussion clarifying the definition of direct versus indirect evidence, these differences were resolved with an agreement score of 100%.

Data extraction and synthesis

Data were extracted from each eligible study by one review author in a tabular format including: the country of study; the sample size; objective physical activity/sedentary behaviour data collection method/s; and any identified correlates (Table 1). A variety of techniques were used in the selected papers to report variables including univariate, bivariate and multilevel analyses. Similar to other reviews [10–12], for analyses focused on correlates where multiple analytic models were reported, findings from the final or fully adjusted models were extracted.

Table 1.

Summary of included articles

| Author/date | Location | Sample | Assessment and Outcome | Correlates of PA observed | Correlates of sedentary behaviour observed | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome | Measurement tool | Variable | SEF Domain | Variable | SEF Domain | |||

| Ajja et al., 2014 [19] | United States | 20 ASPs; 1302 children (5–12 years old); 53.6% boys; 56.1% White | Minutes of MVPA (indoor/outdoor) | Actigraph accelerometer | % local pop. in poverty | Community | % local pop. in poverty | Community |

| Minutes of sedentary behaviour | Actigraph accelerometer | Free play | Institutional | Age of child | Individual | |||

| PA policy characteristics | HAPI-PA Scale | Ethnicity | Individual | BMI | Individual | |||

| BMI | Individual | Ethnicity (non-white) | Individual | |||||

| Age of child | Individual | Size of used PA space | Institutional | |||||

| Size of used PA space | Institutional | Free play | Institutional | |||||

| Supportive PA policy characteristics | Institutional | Supportive PA policy characteristics | Institutional | |||||

| Beets et al., 2012 [20] | United States | 3 ASPs; 245 children (mean age 8.2 years old); 48% boys; 60% White | Minutes of MVPA | Actigraph accelerometer | Minutes in attendance | Individual | ||

| Steps | Walk4Life MVPA pedometer | Meeting 30 min MVPA guideline | Individual | |||||

| Beets et al., 2013 [21] | United States | 18 ASPs; 1241 children (5–12 years old); 50% boys; 59% White | Minutes of MVPA | Actigraph accelerometer | PA evaluation (limited with nonvalid methods) | Institutional | Activities appealing to both genders | Institutional |

| Minutes of sedentary behaviour | Actigraph accelerometer | PA policy (non-specific language) | Institutional | Scheduled PA time (< 25% schedule) | Institutional | |||

| PA policy environment characteristics | Scheduled PA time (50% or more) | Institutional | Child feedback (formal collection) | Institutional | ||||

| Staff PA training (< 1 h) | Institutional | Child feedback (informal collection) | Institutional | |||||

| Staff PA training (1 to 4 h) | Institutional | Scheduled PA time (25–49% schedule) | Institutional | |||||

| Scheduled activities (limited) | Institutional | Scheduled PA time (50% or more) | Institutional | |||||

| Scheduled PA time (< 25% schedule) | Institutional | Staff PA training (< 1 h) | Institutional | |||||

| Child feedback (informal collection) | Institutional | PA curriculum (non-evidence based) | Institutional | |||||

| PA curriculum (non-evidence based) | Institutional | PA evaluation (limited with nonvalid methods) | Institutional | |||||

| Activities appealing to both genders | Institutional | PA policy (non-specific language) | Institutional | |||||

| Child feedback (formal collection) | Institutional | PA training delivered by noncertified personnel | Institutional | |||||

| Scheduled activities (diverse) | Institutional | Scheduled activities (diverse) | Institutional | |||||

| PA training delivered by noncertified personnel | Institutional | Scheduled activities (limited) | Institutional | |||||

| Scheduled PA time (25–49% schedule) | Institutional | Staff PA training (1 to 4 h) | Institutional | |||||

| Beets et al., 2015 [22] | United States | 19 ASPs; 812 children (6–12 years old); 53% boys; 61% White non-Hispanic | Minutes of total PA | Actigraph accelerometer | BMI | Individual | ||

| Minutes of MVPA | Actigraph accelerometer | School-based ASP | Institutional | |||||

| Meeting PA policy benchmarks | Ethnicity (non-white) | Individual | ||||||

| Age of child | Individual | |||||||

| Attended faith-based ASP | Institutional | |||||||

| Sex | Individual | |||||||

| Beets et al., 2016 [23] | United States | 20 ASPs; 1408 children (5–12 years old); 56% boys | Minutes of MVPA | Actigraph accelerometer | % PA opportunities dedicated for free play (45–74%) | Institutional | % PA opportunities dedicated for free play (45–74%) | Institutional |

| Minutes of sedentary behaviour | Actigraph accelerometer | Scheduled PA time (110–160 min) | Institutional | % PA opportunities dedicated for free play (75–100%) | Institutional | |||

| Program characteristics | Review of schedules; direct observation | Scheduled PA time (90–105 min) | Institutional | Annual organisation revenue (approx $2–4 million) | Institutional | |||

| Sedentary option during PA time (60 min) | Institutional | Annual organisation revenue (approx $5–20 million) | Institutional | |||||

| Sedentary option during PA time (75–120 min) | Institutional | Attending YMCA ASP | Institutional | |||||

| Annual organisation revenue (approx $2–4 million) | Institutional | Scheduled PA time (110–160 min) | Institutional | |||||

| Annual organisation revenue (approx $5–20 million) | Institutional | Scheduled PA time (90–105 min) | Institutional | |||||

| Attending YMCA ASP | Institutional | Sedentary option during PA time (60 min) | Institutional | |||||

| Outdoor PA space (approx 231 k-281 k ft2) | Institutional | Sedentary option during PA time (75–120 min) | Institutional | |||||

| Outdoor PA space (approx 85 k-200 k ft2) | Institutional | Indoor PA space (4461–6009 ft2) | Institutional | |||||

| % PA opportunities dedicated for free play (75–100%) | Institutional | Indoor PA space (7344–15,056 ft2) | Institutional | |||||

| Indoor PA space (4461–6009 ft2) | Institutional | Outdoor PA space (approx 231 k-281 k ft2) | Institutional | |||||

| Indoor PA space (7344–15,056 ft2) | Institutional | Outdoor PA space (approx 85 k-200 k ft2) | Institutional | |||||

| Staff PA training (1 or more hours) | Institutional | Staff PA training (1 or more hours) | Institutional | |||||

| Brazendale et al., 2015 [24] | United States | 20 ASPs; 1248 children (5–12 years old); 53% boys | Scheduled PA time | Schedule review | Scheduled PA time (< 60 min) | Institutional | ||

| Minutes of MVPA | Actigraph accelerometer | Scheduled PA time (> 60 min) | Institutional | |||||

| Scheduled PA time (≈ 45 min) | Institutional | |||||||

| Scheduled PA time (≤ 30 min) | Institutional | |||||||

| Scheduled PA time (≥ 105 min) | Institutional | |||||||

| Scheduled PA time (60 min) | Institutional | |||||||

| Scheduled PA time (75 min) | Institutional | |||||||

| Burrows et al., 2014 [25] | Canada | 2 ASPs; 40 children (6–10 years old); 42% boys | FMS proficiency | Test of Gross Motor Development 2 | Attended sport-based ASP | Institutional | ||

| Low-organised game ASP | Institutional | |||||||

| Crowe et al., 2021 [26] | Australia | 89 ASPs; 4408 children (5–12 years old); 42% boys | Child physical activity | Actigraph accelerometer | Sex | Individual | Sex | Individual |

| Physical activity policies | HAAND | Grade | Individual | Grade | Individual | |||

| Physical activity promotion practices | SOSPAN | PA policy | Institutional | |||||

| Type and structure of physical activity | SOSPAN | Staff PA training | Institutional | |||||

| Available PA space | Craftright measuring wheel | PA promotion material | Institutional | |||||

| Screen time availability | Institutional | |||||||

| Handheld device availability | Institutional | |||||||

| Children input in daily programming | Institutional | |||||||

| Scheduled free play | Institutional | |||||||

| Organised PA | Institutional | |||||||

| Children engaged in PA | Individual | |||||||

| Children stand and wait during PA games | Interpersonal | |||||||

| Elimination games | Institutional | |||||||

| Staff engaged in PA | Interpersonal | |||||||

| Domazet et al., 2015 [27] | Denmark | 10 ASPs; 475 children (5–11 years old); 41% boys | MVPA minutes | Actigraph accelerometer | Attended regular ASP | Institutional | Attended non sport-based ASP | Institutional |

| Cardiovascular fitness | Attended sport-based ASP | Institutional | Attended sport-based ASP | Institutional | ||||

| Huberty et al., 2013 [28] | United States | 12 ASPs; 888 children (mean age 8.7 years old); 44% boys; 77% White non-Hispanic | Staff behaviour | SOPLAY | Minutes of scheduled PA | Institutional | ||

| Scans observed sedentary | SOPLAY | Organised PA | Institutional | |||||

| Scans observed walking | SOPLAY | PA equipment available | Institutional | |||||

| Scans observed vigorous | SOPLAY | Staff engaged in PA | Interpersonal | |||||

| Staff off task during PA | Interpersonal | |||||||

| Staff other duties during PA | Interpersonal | |||||||

| Staff promoting PA | Interpersonal | |||||||

| Total number of boys/girls | Institutional | |||||||

| Kuritz et al., 2020 [29] | Germany | ASPs; 198 children | % of time in sedentary, LPA & MVPA | Actigraph accelerometer | Minutes in attendance | Individual | Sex | Individual |

| Socio-demographic data | Motorik-Modul activity questionnaire | Sex | Individual | Grade (year 1 only) | Individual | |||

| Age of child | Individual | Minutes in attendance | Individual | |||||

| Londal et al., 2020 [30] | Norway | 14 ASPs; 42 children (Grade 1); 52% boys | Time in sedentary behaviour, total PA and MVPA | Actigraph accelerometer | Outdoor PA (comparison indoor) | Institutional | Sex | Individual |

| PA periods | Observation form | Sex | Individual | |||||

| Maher et al., 2019 [31] | Australia | 23 ASPs; 1068 children | Service contexual information and policies | HAAND | Number of active play zones available | Institutional | % of session in MVPA | Institutional |

| Sedentary, LPA, MVPA | SOPLAY | Outdoor play duration | Institutional | Availability of screen before 5 pm | Institutional | |||

| Staff PA and nutrition promotion behaviours | SOSPAN | Screen availability | Institutional | Screen availability | Institutional | |||

| Total number of screen devices | Institutional | Service size | Institutional | |||||

| Availability of screens before 5 pm | Institutional | Number of active play zones available | Institutional | |||||

| Service size | Institutional | Outdoor play duration | Institutional | |||||

| Staff promoting PA | Interpersonal | Staff promoting PA | Interpersonal | |||||

| Staff witholding PA | Interpersonal | Staff witholding PA | Interpersonal | |||||

| Total number of screen devices | Institutional | |||||||

| Riiser et al., 2019 [32] | Norway | 14 ASPs; 426 children (Grade 1); 52% boys | Physical activity | Actigraph accelerometer | BMI | Individual | BMI | Individual |

| Child biometrics | Sex | Individual | Sex | Individual | ||||

| Rosenkranz et al., 2011 [33] | United States | 7 ASPs 230 children (grade 3 and 4) | Physical activity | Actigraph accelerometer | Child self-efficacy | Individual | ||

| PA enjoyment | Individual | |||||||

| Sex | Individual | |||||||

| BMI | Individual | |||||||

| Parent PA social support | Interpersonal | |||||||

| Child socioeconomic status | Individual | |||||||

| Ethnicity (non-white) | Individual | |||||||

| Trost et al., 2008 [34] | United States | 7 ASPs; 147 children (mean age 10.1 years old); 54% male | Physical activity | Actigraph accelerometer | BMI | Individual | BMI | Individual |

| Height and weight | Anthropometric measures | Sex | Individual | Sex | Individual | |||

| Indoor free play (comparison academic time) | Institutional | |||||||

| Indoor free play (comparison indoor organised PA) | Institutional | |||||||

| Indoor free play (comparison outdoor free play) | Institutional | |||||||

| Indoor free play (comparison outdoor organised PA) | Institutional | |||||||

| Indoor free play (comparison snack time) | Institutional | |||||||

| Indoor organised PA (comparison academic time) | Institutional | |||||||

| Indoor organised PA (comparison outdoor free play) | Institutional | |||||||

| Indoor organised PA (comparison outdoor organised PA) | Institutional | |||||||

| Indoor organised PA (comparison snack time) | Institutional | |||||||

| Outdoor free play (comparison academic time) | Institutional | |||||||

| Outdoor free play (comparison outdoor organised PA) | Institutional | |||||||

| Outdoor free play (comparison snack time) | Institutional | |||||||

| Outdoor organised PA (comparison academic time) | Institutional | |||||||

| Outdoor organised PA (comparison snack time) | Institutional | |||||||

| Snack time (comparison academic time) | Institutional | |||||||

| Weaver et al., 2014 [35] | United States | 4 ASPs; Undisclosed | Staff PA and nutrition promotion behaviours | SOSPAN | Children stand and wait during PA games | Institutional | Scheduled enrichment | Institutional |

| Scans observed sedentary | SOPLAY | Elimination PA games | Institutional | Children stand and wait during PA games | Institutional | |||

| Scans observed walking | SOPLAY | Idle time | Institutional | Elimination PA games | Institutional | |||

| Scans observed vigorous | SOPLAY | Scheduled academics | Institutional | Scheduled snack | Institutional | |||

| Scheduled activity rotation | Institutional | Idle time | Institutional | |||||

| Scheduled bathroom | Institutional | Scheduled academics | Institutional | |||||

| Scheduled enrichment | Institutional | Scheduled activity rotation | Institutional | |||||

| Scheduled snack | Institutional | Scheduled bathroom | Institutional | |||||

| Staff discipline children | Interpersonal | Staff discipline children | Interpersonal | |||||

| Staff discouraging PA | Interpersonal | Staff discouraging PA | Interpersonal | |||||

| Staff engaged in PA | Interpersonal | Staff engaged in PA | Interpersonal | |||||

| Staff giving instructions during PA | Interpersonal | Staff giving instructions during PA | Interpersonal | |||||

| Staff leading PA | Interpersonal | Staff leading PA | Interpersonal | |||||

| Staff off task during PA | Interpersonal | Staff off task during PA | Interpersonal | |||||

| Staff other duties during PA | Interpersonal | Staff other task during PA | Interpersonal | |||||

| Staff promoting PA | Interpersonal | Staff promoting PA | Interpersonal | |||||

| Staff witholding PA | Interpersonal | Staff witholding PA | Interpersonal | |||||

| Zarrett et al., 2015 [36] | United States | 7 ASPs; Undisclosed (7–12 years old); 56% male | PA levels in METS | SOPLAY | Average temperature | Community | ||

| Social and environment context of PA | SOPLAY | Children appear engaged | Individual | |||||

| Social-motivational climate of ASPs | MCOT-PA | Clear PA rules | Institutional | |||||

| Free play | Institutional | |||||||

| Organised PA | Institutional | |||||||

| PA activity includes most children | Institutional | |||||||

| PA equipment available | Institutional | |||||||

| Staff encouraging out-of-program PA | Interpersonal | |||||||

| Staff engaged in PA | Interpersonal | |||||||

| Staff leading PA | Interpersonal | |||||||

| Staff promoting PA | Interpersonal | |||||||

| Staff supervision | Interpersonal | |||||||

| Staff supervising PA | Interpersonal | |||||||

| Usable environment | Institutional | |||||||

| Youth interacting positively with one another | Interpersonal | |||||||

Abbreviations: ASPs after school programs, BMI body mass index, HAAND Healthy Afterschool Activity and Nutrition Documentation, HAPI-PA Healthy Afterschool Program Index-Physical Activity scale, LPA light physical activity, MCOT-PA Motivational Climate Observation Tool for Physical Activity, MPA moderate physical activity, MVPA moderate to vigorous physical activity, PA physical activity, SEF social ecological framework, SOPLAY System for Observing Play and Leisure in Youth, SOSPAN System for Observing Staff Promotion of Physical Activity and Nutrition

The correlates were categorised by one review author (AW) into their associated social ecological framework domain: individual, interpersonal, institutional, community and public policy [13]. A second review author (JN) reviewed the categorisation and any discrepancies were discussed and consensus reached. Consistent with other reviews of PA and sedentary behaviour in children [10–12] the social ecological framework was used to allow for the investigation of multidimensional factors that influence PA and sedentary behaviour; and provide an organised approach to inform future interventions in the OSHC setting [13]. In the context of this review, the institutional domain refers to correlates at the individual OSHC service provider level, whereas the community domain refers to correlates that are external to the service and from the wider society.

Correlates were summarised to determine shared associations (see Additional files 1 and 2). Correlates which reported a statistically significant (p < 0.05) association with a PA or sedentary behaviour outcome measure were coded as + or – depending on the association (Column 4, Additional files 1 and 2). Those reporting no significant association were recorded in Column 5. The number of times a correlate was associated with an outcome variable was tallied against the total number of times the association was observed (including studies with no significant association). The tally was converted into a percentage (Column 7, Additional files 1 and 2) and analysed using a summary code to represent the association (Table 2). This was similar to a previously published extraction and synthesis process [11] and method of coding [10, 12]. This summary code for the overall association was then recorded (Column 8, Additional files 1 and 2) and used for discussion of the results.

Table 2.

Rules for classifying variables regarding strength of association

| Outcome measures supporting association (%) | Summary code | Explanation of code |

|---|---|---|

| 0–33 | 0 | Non-significant association |

| 34–59 | ? | Inconclusive association |

| 60–100 | + | Positive association |

| 60–100 | - | Negative association |

Note: When a correlation was observed in three or more studies, it was coded as: 00 (non-significant association for three or more studies); ?? (inconclusive for three or more studies); + + (positive association for three or more studies); – (negative association for three or more studies). This assists visually with correlations that were more widely studied

Reporting of outcome findings

The reporting of outcome findings in the results is presented using the summary coding for each correlate (Column 7, Additional files 1 and 2). Accordingly, (n/N) refers to the number of significant associations found with outcome measures / total number of associations studied (for that particular correlate). The literature cited refers to the studies which reported the summary code relationship for that correlate (i.e. no association, indeterminate association, positive association, negative association).

Results

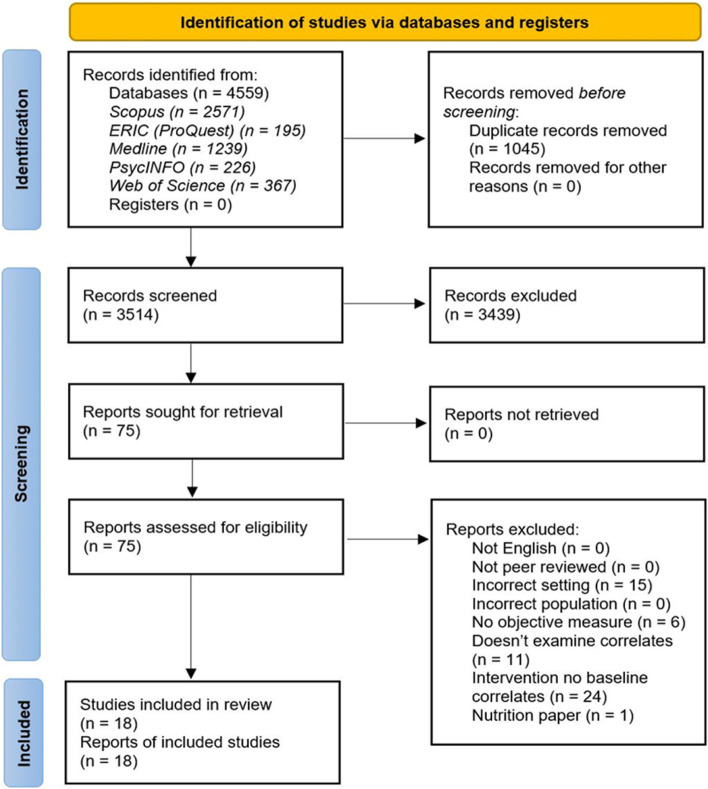

A total of 4559 papers were retrieved with 3514 remaining after duplicates were removed (Fig. 1). Following the title and abstract screening, 75 studies were retrieved for full-text review. Of these, 18 studies met the inclusion criteria and were included in this review (Table 1). Publication years of included studies ranged from 2008 – 2021, with all but two studies [33, 34] published in the last 10 years. Most studies (61%) were conducted in the United States (n = 11) [19–24, 28, 33–36]. The remainder were from Australia (n = 2) [26, 31], Norway (n = 2) [30, 32], Canada (n = 1) [25], Denmark (n = 1) [27] and Germany (n = 1) [29]. All studies were conducted in after school programs (n = 18) with no studies in before school care settings. As the decision to remove healthy eating from this review was made after the screening was completed, the numbers indicated in the PRISMA flow diagram (Fig. 1) include studies which met the healthy eating search terms indicated in the search strategy of the methods section.

Fig. 1.

PRISMA flow diagram for the search results and inclusions process for identification of articles

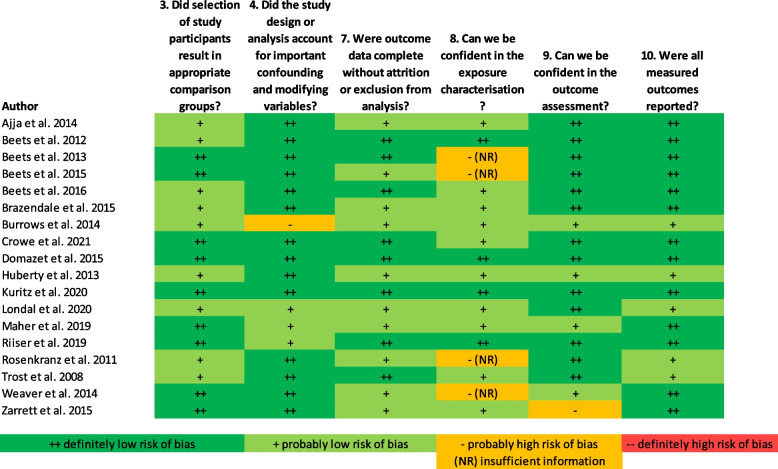

Risk of bias in studies

All included studies had an overall ‘definitely low’ or ‘probably low’ risk of bias (Fig. 2). No studies had any criteria which were ‘definitely high’ risk of bias, and only six studies had one ‘probably high’ risk of bias criterion [21, 22, 25, 33, 35, 36]. The most common ‘probably high’ risk of bias was related to the exposure characterisation, with four studies using invalidated methods to measure the exposure(s) [21, 22, 33, 35]. Due to these exposure measures being indirect, the tool called for ‘(NR)’ to be recorded which indicates there was insufficient information to assess risk.

Fig. 2.

Risk of bias in individual studies, assessed using the OHAT Risk of Bias Rating Tool [18]

Summarising the studies

PA and sedentary behaviour were assessed using a range of measurement methods. Thirteen studies used accelerometers [19–24, 26, 27, 29, 30, 32–34], one study used pedometers [20], and six studies used direct observations via three tools—System for Observing Play and Leisure Activity in Youth (SOPLAY) (n = 4) [28, 31, 35, 36], Test of Gross Motor Development 2 (n = 1) [25], and one other unnamed observation tool (n = 1) [30]. Correlational information on the PA and sedentary behaviour environments was collected from policy reviews using five tools: System for Observing Staff Promotion of Activity and Nutrition (SOSPAN) (n = 3) [26, 31, 35], Healthy Afterschool Program Index-Physical Activity (HAPI-PA) scale (n = 1) [19], Healthy Afterschool Activity and Nutrition Documentation (HAAND) (n = 2) [26, 31], a PA policy environment framework (n = 1) [21] and policy benchmarks (n = 1) [22]. Other correlational information was collected from a review of the service schedule (n = 2) [23, 24], an unnamed psychosocial questionnaire (n = 1) [33], Motivational Climate Observation Tool for Physical Activity (MCOT-PA) (n = 1) [36], and administrative records (n = 1) [33].

A total of 116 correlates of PA were identified (Additional file 1), of which 10 were classified as individual, 14 as interpersonal, 90 as institutional and two as community variables. There were 64 correlates of sedentary behaviour identified (Additional file 2), of which six were classified as individual variables, nine as interpersonal, 48 as institutional and one as a community variable. Identified associations reflected the relationship between the correlate and PA or sedentary behaviour outcome stated in Column 3 (Additional files 1 and 2).

Summarising the outcome findings

Individual variables

Ten individual level correlates relating to PA were identified (Additional file 1). The most frequently observed individual correlates were sex and BMI. Seven studies [22, 26, 29, 30, 32–34] reported 30 associations between sex and varying PA outcomes, six of which found 20 significantly positive associations (n = 20/30) [22, 26, 29, 32–34]. This indicates a positive association between sex and PA, with males more physically active than females. Five studies [19, 22, 32–34] reported 26 associations with BMI, of which only four studies found five which were significantly negative (n = 5/26) [19, 22, 32, 34] indicating an overall null association. An inconclusive association was also found between PA and age, with three studies reporting eight significant negative associations out of 16 total (n = 8/16) [19, 22, 26].

Six individual level correlates relating to sedentary behaviour were also identified (Additional file 2), with the most frequently observed being sex, BMI and age. Five studies reported eight associations between sex and sedentary behaviour, six of which were significantly negative indicating an overall negative association and showing that females were more sedentary than males (n = 6/8) [26, 29, 30, 32]. An overall inconclusive association was found between BMI and sedentary behaviour, with three studies reporting seven non-significant associations (n = 0/7) [19, 32, 34]. Two studies revealed an overall positive association between age and sedentary behaviour (n = 4/6) [19, 26], finding older children more sedentary.

Interpersonal variables

There were 14 interpersonal level correlates relating to PA (Additional file 1). The most commonly reported was staff verbally promoting PA with four studies [28, 31, 35, 36] reporting 13 correlates, of which only two were significant (n = 2/13) [28, 36] revealing an overall non-significant association. Staff being engaged in PA was found to have an overall positive association with PA outcomes, as two studies reported seven significantly positive associations (n = 7/10) [35, 36]. One study also found that staff supervision of PA (n = 3/3) and children interacting positively with each other (n = 2/3) had positive associations on PA [36].

Nine interpersonal correlates relating to sedentary behaviour were reported (Additional file 2). One study found positive associations between staff disciplining children during PA (n = 2/2), staff discouraging PA (n = 2/2) and staff giving instructions during PA (n = 2/2) with sedentary behaviour outcomes [35]. The same study also reported a negative association between staff engaged in PA and sedentary behaviour (n = 2/2) [35].

Institutional variables

Ninety institutional correlates of PA were identified (Additional file 1). The most frequently studied related to the associations between activity structure (organised PA and free play) and PA outcomes. The results were inconclusive. Two studies reported seven associations between free play and PA, with only two being significant (n = 2/7) [19, 36] revealing an overall non-significant association. Two studies [28, 36] also reported eight associations between organised PA and PA outcomes, and only one was reported as significant (n = 1/8) [36] indicating another non-significant association. PA games with an elimination component were found to be associated with reduced PA levels, as two studies reported five negative associations between elimination PA games and PA (n = 5/5) [26, 35]. PA equipment availability is associated with increased PA, with two studies reporting four positive associations (n = 4/5) [28, 36]. Scheduling PA time in OSHC was also found associated with increased PA, with one study finding a positive association between scheduled PA time of 60 and 75 min with PA (n = 2/2) [24], another study finding a positive association with scheduled PA time between 90–105 min and PA (n = 4/4) [23], and one more finding a positive association with scheduling 50% or more of the session for PA and PA outcomes (n = 2/2) [21]. Another study also found that scheduling 30 min or more of free play (n = 1/1) [26] and organised PA (n = 1/1) [26] was found positively associated with PA.

Forty-eight institutional correlates of sedentary behaviour were identified (Additional file 2). One study found two positive associations between elimination-based PA games and sedentary behaviour (n = 2/2) [35], however conversely found two positive associations between children standing and waiting during PA games and sedentary behaviour (n = 2/2) [35]. Scheduling 50% or more of the OSHC session for PA time was found to have an overall negative association on sedentary behaviour, with one study finding two negative associations (n = 2/2) [21]. Screen time was also found to be associated with increased sedentary behaviour, with a study finding that screen availability and the total number of screen devices in a service both increase the percentage of the session children spend in screen time (n = 1/1) [31].

Community variables

There were two community level correlates of PA identified (Additional file 1). One study found a non-significant association between percentages of the local population living in poverty and PA (n = 0/4) [19] and another found a non-significant association between the average temperature and PA (n = 0/3) [36].

One community correlate of sedentary behaviour was identified (Additional file 2). This consisted of one study reporting four associations between percentage of the local population in poverty and sedentary behaviour, of which only one was significantly positive resulting in an overall non-significant association (n = 1/4) [19].

Public policy variables

No extracted correlates were categorised into the public policy domain.

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first systematic review that reports the correlates of objectively measured physical activity and sedentary behaviour in OSHC services. This review demonstrated the varying social ecological domains which were associated with physical activity and sedentary behaviour, similar to other reviews [11, 12]. Physical activity correlates were most frequently reported, however, sedentary behaviour was often addressed in conjunction. The majority of the extracted correlates were categorised into the institutional domain, followed by the interpersonal, individual and community domains respectively. This demonstrates the priority areas interventions within the OSHC setting should target.

The individual domain demonstrated an association that males engage in more PA and are less sedentary than females, which is consistent with reviews of children in other settings [10, 11]. This highlights a need for OSHC services to better engage female children in physical activity, possibly through programming activities which appeal to both sexes. This idea is consistent with a correlate found in the institutional domain, which found programming activities which appeal to both sexes is associated with increased PA among females [20]. This relationship between correlates is an example of the interactions which exist between the social ecological domains, and how looking at PA and sedentary behaviour in the OSHC setting through this framework offers an insightful approach for future interventions.

The interpersonal domain revealed correlates of PA and sedentary behaviour which was anticipated. Staff engaging in and supervising PA was associated with increased physical activity levels [35, 36], and staff discouraging PA and disciplining children was significantly associated with increased sedentary behaviour [35]. The discouragement of PA and discipline of children being associated with more time spent sedentary is an implied relationship, which makes it concerning that staff are actively engaging in this behaviour. Staff training and service policies to promote staff engaging in and supervising PA and educating staff not to discourage children while they are physically active should be an approach for all OSHC services.

In this review, the institutional domain provided most insight into the correlates of PA and sedentary behaviour in OSHC. PA games which involve elimination were associated with reduced PA and increased sedentary behaviour [26, 35], something commonly seen and a game element studies recommend against using [37]. Increased PA equipment availability was also associated with higher PA levels [28, 36]. While availability of equipment is dependent upon finances, services should explore their options around acquiring and providing additional PA equipment through fundraising and other means. OSHC services also need to prioritise scheduling dedicated PA time into their daily programming, as several studies found associations between higher levels of scheduled PA and reduced sedentary behaviour and increased PA levels [21, 23, 24].

Findings around activity structure through the impact of free play and organised PA were mixed, with several studies exploring these factors and finding no significant associations or conflicting results [19, 28, 34, 36]. Further research should be conducted to determine more definitively the association between activity structure and PA and sedentary behaviour in OSHC services. One institutional correlate which was unexpected was children standing and waiting during PA games being associated with higher levels of PA and lower levels of sedentary behaviour [35]. It is, however, important to note that this was only found in one study and was attributed to the complex nature of the OSHC program setting with many events happening simultaneously possibly causing this contradictory relationship [35].

All studies were based in the after school care setting, with no studies included from the before school care setting. This was not unexpected, as preliminary literature searches found most of the research conducted in the OSHC setting was from the United States, and searches for before school care in the United States revealed very little information, suggesting that it is not a prominent setting in that country. Before school care is, however, common in countries such as Australia where there are 4258 registered services who offer this care [38], and New Zealand where 8% of children 6–12 years attend before school care [39]. This reveals another gap in the literature and a need for more studies in OSHC based outside of the United States.

It is important to note that this review initially included correlates of healthy eating in the OSHC setting, though was modified when only one study met the inclusion criteria [40]. While there were a few studies on the food environment of OSHC identified, an inclusion criteria for this review was an objective measure, and most of the studies either did not look at the consumption of food or the measures were subjective in nature. While the screening criteria of this study may have been too stringent to explore the healthy eating environments of the OSHC setting, it does reveal a gap in the literature of a lack of objective healthy eating studies in OSHC services.

Limitations

The results of this review should be considered in light of a number of limitations, including: 1) there were only a small number of studies for most variables; 2) most of the studies were from the United States and may limit the generalisability of the results; 3) none of the included studies observed the before school care setting, meaning the findings may not be representative of that sector; 4) the studies reviewed varied in sample size, outcome measures, and methodologies (although all used an objective measure of PA or sedentary behaviour), which may impact the heterogeneity of the estimates and likelihood of biases in conclusions made; 5) only studies which used an objective measure of PA or sedentary behaviour were included in this review, therefore findings from studies using subjective measures were not accounted for and could vary some of the conclusions made in this study; 6) there was only one author responsible for extracting data from included studies and, though this process was undertaken with extreme diligence, there is potential for error.

Conclusions

This review is important as a large number of children aged 5–13 years attend before and/or after school care services [4], and the sector has been identified as having the potential to positively influence the physical activity, sedentary behaviour and heathy eating of children [5, 6, 41]. This review provides an understanding of the diverse range of influences in participation in physical activity and sedentary behaviour among children while attending OSHC services. It reinforces that females are often less physically active and more sedentary than males in these environments, with service providers and staff needing to explore ways to further engage female children in PA. Service providers also need to monitor staff behaviours around PA through means such as training and policy, as it has the potential to both positively and negatively influence how active children are. They should also look towards removing elimination elements from their PA games, try to schedule more time for PA and also provide more PA equipment for children to use. Health researchers need to look further into how activity structure impacts on child PA, as current studies report mixed findings. This review addresses a knowledge gap and will contribute to future research in both the OSHC setting and childhood overweight and obesity prevention.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1. Summary of reported physical activity correlates.

Additional file 2. Summary of reported sedentary behaviour correlates.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- BMI

Body mass index

- HAAND

Healthy Afterschool Activity and Nutrition Document

- HAPI-PA

Healthy Afterschool Program Index-Physical Activity

- MCOT-PA

Motivational Climate Observation Tool for Physical Activity

- MVPA

Moderate-to-vigorous physical activity

- OECD

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development

- OHAT

Office of Health Assessment and Translation

- OSHC

Out of school hours care

- PA

Physical activity

- PRISMA

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analysis

- PROSPERO

International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews

- SOPLAY

System for Observing Play and Leisure Activity in Youth

- SOSPAN

System for Observing Staff Promotion of Physical Activity and Nutrition

Authors’ contributions

AW is a PhD candidate within this study and has worked with the research team to develop the study design and methodology; screened literature for review inclusion; and led data extraction, analysis, interpretation and write up of this manuscript. YP, KW and JN are PhD supervisors and co-investigators on this project. They have contributed to the funding support, study design and revised the manuscript. SR, LP and RC were involved in screening literature for review inclusion and revised the manuscript. AO is the chief investigator of this study, contributing to the funding support, study design, methodologies and is a PhD supervisor on this project. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript. This manuscript has not been submitted or published in any other journal.

Funding

This research has been conducted with the support of the Australian Government Research Training Program Scholarship. This work was supported by the Prevention Research Support Program, funded by the New South Wales Ministry of Health. We declare the funding body has had no influence on the study design, data collection, analysis, interpretations of the findings or writing of this manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets supporting the conclusions of this article are included within the article (and its additional files).

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors have declared there is no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Andrew J. Woods, Email: ajw989@uowmail.edu.au

Yasmine C. Probst, Email: yasmine@uow.edu.au

Jennifer Norman, Email: jennifer.norman@health.nsw.gov.au.

Karen Wardle, Email: karen.wardle@health.nsw.gov.au.

Sarah T. Ryan, Email: sr139@uowmail.edu.au

Linda Patel, Email: le092@uowmail.edu.au.

Ruth K. Crowe, Email: ruth.crowe@health.nsw.gov.au

Anthony D. Okely, Email: tokely@uow.edu.au

References

- 1.World Health Organization. Childhood overweight and obesity. 2019. Available from: https://www.who.int/dietphysicalactivity/childhood/en/.

- 2.World Health Organization. Obesity and overweight. 2020. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/obesity-and-overweight.

- 3.World Health Organization. Childhood overweight and obesity- what are the causes? 2019. Available from: https://www.who.int/dietphysicalactivity/childhood_why/en/.

- 4.OECD Social Policy Division. OECD family database - out of school hours services. Paris: OECD; 2019. Available from: https://www.oecd.org/els/family/database.htm.

- 5.Mozaffarian RS, Wiecha JL, Roth BA, Nelson TF, Lee RM, Gortmaker SL. Impact of an organizational intervention designed to improve snack and beverage quality in YMCA after-school programs. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(5):925–932. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.158907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Weaver RG, Beets MW, Huberty J, Freedman D, Turner-Mcgrievy G, Ward D. Physical activity opportunities in afterschool programs. Health Promot Pract. 2015;16(3):371–382. doi: 10.1177/1524839914567740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Branscum P, Sharma M. After-school based obesity prevention interventions: a comprehensive review of the literature. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2012;9(4):1438–1457. doi: 10.3390/ijerph9041438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cliff DP, Hesketh KD, Vella SA, Hinkley T, Tsiros MD, Ridgers ND, et al. Objectively measured sedentary behaviour and health and development in children and adolescents: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes Rev. 2016;17(4):330–344. doi: 10.1111/obr.12371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bauman AE, Reis RS, Sallis JF, Wells JC, Loos RJF, Martin BW. Correlates of physical activity: why are some people physically active and others not? The Lancet. 2012;380(9838):258–271. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60735-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ridgers ND, Salmon J, Parrish A-M, Stanley RM, Okely AD. Physical activity during school recess: a systematic review. Am J Prev Med. 2012;43(3):320–328. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2012.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tonge KL, Jones RA, Okely AD. Correlates of children's objectively measured physical activity and sedentary behavior in early childhood education and care services: a systematic review. Prev Med. 2016;89:129–139. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2016.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hinkley T, Salmon J, Okely AD, Trost SG. Correlates of sedentary behaviours in preschool children: a review. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2010;7(1):66. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-7-66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McLeroy KR, Bibeau D, Steckler A, Glanz K. An ecological perspective on health promotion programs. Health Educ Q. 1988;15(4):351–377. doi: 10.1177/109019818801500401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:n71. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.The EndNote Team . EndNote. EndNote. 20. Philadelphia, PA: Clarivate; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Welk GJ. Physical activity assessments for health-related research. Champaign: Human Kinetics; 2002.

- 17.Hands B, Larkin D. Physical Activity Measurement Methods for Young Children: a Comparative Study. Meas Phys Educ Exerc Sci. 2006;10(3):203–214. doi: 10.1207/s15327841mpee1003_5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.US Department of Health and Human Services. OHAT risk of bias rating tool for human and animal studies. North Carolina: National Toxicology Program; 2015. Available from: https://ntp.niehs.nih.gov/whatwestudy/assessments/noncancer/riskbias/index.html.

- 19.Ajja R, Clennin MN, Weaver RG, Moore JB, Huberty JL, Ward DS, et al. Association of environment and policy characteristics on children’s moderate-to-vigorous physical activity and time spent sedentary in afterschool programs. Preventive Med. 2014;69(S):S49–S54. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2014.09.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Beets MW, Beighle A, Bottai M, Rooney L, Tilley F. Pedometer-determined step-count guidelines for afterschool programs. J Phys Act Health. 2012;9(1):71–77. doi: 10.1123/jpah.9.1.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Beets MW, Huberty J, Beighle A, Moore JB, Webster C, Ajja R, et al. Impact of policy environment characteristics on physical activity and sedentary behaviors of children attending afterschool programs. Health Educ Behav. 2013;40(3):296–304. doi: 10.1177/1090198112459051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Beets MW, Shah R, Weaver RG, Huberty JL, Beighle A, Moore JB. Physical activity in after-school programs: Comparison with physical activity policies. J Phys Act Health. 2015;12(1):1–7. doi: 10.1123/jpah.2013-0135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Beets MW, Weaver RG, Turner-Mcgrievy G, Moore JB, Webster C, Brazendale K, et al. Are we there yet? Compliance with physical activity standards in YMCA afterschool programs. Child Obes. 2016;12(4):237–246. doi: 10.1089/chi.2015.0223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brazendale K, Beets MW, Weaver RG, Huberty J, Beighle AE, Pate RR. Wasting our time? Allocated versus accumulated physical activity in afterschool programs. J Phys Act Health. 2015;12(8):1061–1065. doi: 10.1123/jpah.2014-0163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Burrows EJ, Keats MR, Kolen AM. Contributions of after school programs to the development of fundamental movement skills in children. Int J Exerc Sci. 2014;7(3):236–249. doi: 10.70252/AXFM7487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Crowe RK, Probst YC, Stanley RM, Ryan ST, Weaver RG, Beets MW, et al. Physical activity in out of school hours care: an observational study. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2021;18(1):127. doi: 10.1186/s12966-021-01197-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Domazet SL, Moller NC, Stockel JT, Ried-Larsen M. Objectively measured physical activity in Danish after-school cares: Does sport certification matter? Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2015;25(6):E646–54. doi: 10.1111/sms.12361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Huberty JL, Beets MW, Beighle A, McKenzie TL. Association of staff behaviors and afterschool program features to physical activity: Findings from Movin' After School. J Phys Activ Health. 2013;10(3):423–9. doi: 10.1123/jpah.10.3.423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kuritz A, Mall C, Schnitzius M, Mess F. Physical activity and sedentary behavior of children in afterschool programs: An accelerometer-based analysis in full-day and half-day elementary schools in germany. Front Public Health. 2020;8:463. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2020.00463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Løndal K, Hage Haugen AL, Lund S, Riiser K. Physical activity of first graders in Norwegian after-school programs: a relevant contribution to the development of motor competencies and learning of movements? Investigated utilizing a mixed methods approach. PLoS ONE. 2020;15(4):e0232486. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0232486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Maher C, Virgara R, Okely T, Stanley R, Watson M, Lewis L. Physical activity and screen time in out of school hours care: An observational study. BMC Pediatr. 2019;19(1):283. doi: 10.1186/s12887-019-1653-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Riiser K, Haugen ALH, Lund S, Løndal K. Physical activity in young schoolchildren in after school programs. J Sch Health. 2019;89(9):752–758. doi: 10.1111/josh.12815. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rosenkranz RR, Welk GJ, Hastmann TJ, Dzewaltowski DA. Psychosocial and demographic correlates of objectively measured physical activity in structured and unstructured after-school recreation sessions. J Sci Med Sport. 2011;14(4):306–311. doi: 10.1016/j.jsams.2011.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Trost SG, Rosenkranz RR, Dzewaltowski D. Physical activity levels among children attending after-school programs. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2008;40(4):622–629. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e318161eaa5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Weaver RG, Beets MW, Webster C, Huberty J. System for observing staff promotion of activity and nutrition (SOSPAN) J Phys Act Health. 2014;11(1):173–185. doi: 10.1123/jpah.2012-0007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zarrett N, Sorensen C, Cook BS. Physical and social-motivational contextual correlates of youth physical activity in underresourced afterschool programs. Health Educ Behav. 2015;42(4):518–529. doi: 10.1177/1090198114564502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Foster K, Behrens T, Jager A, Dzewaltowski D. Effect of elimination games on physical activity and psychosocial responses in children. J Phys Act Health. 2010;7:475–483. doi: 10.1123/jpah.7.4.475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Australian Children's Education & Care Quality Authority. National registers. 2019. Available from: https://www.acecqa.gov.au/resources/national-registers.

- 39.Morton S, Grant C, Walker C, Berry S, Meissel K, Ly K, et al. Growing up in New Zealand: A longitudinal study of New Zealand children and their families. Auckland: University of Auckland; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kenney EL, Austin SB, Cradock AL, Giles CM, Lee RM, Davison KK, et al. Identifying sources of children's consumption of junk food in boston after-school programs, april-may 2011. Prev Chronic Dis. 2014;11(11):E205. doi: 10.5888/pcd11.140301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ajja R, Beets MW, Huberty J, Kaczynski AT, Ward DS. The Healthy Afterschool Activity and nutrition documentation instrument. Am J Prev Med. 2012;43(3):263–271. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2012.05.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1. Summary of reported physical activity correlates.

Additional file 2. Summary of reported sedentary behaviour correlates.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets supporting the conclusions of this article are included within the article (and its additional files).