Abstract

We investigate the value of investor relations (IR) and find firms with strong IR to experience between five and eight percentage points higher stock returns than those with weak IR during the COVID-19 crisis. Firms with better-quality IR are also associated with higher investor loyalty and appear to have attracted significantly more institutional investors over the crisis period. This suggests that a firm’s IR contributes to value generation by enhancing credibility with shareholders and by diversifying its shareholder base. After decomposing IR into public and private transmission channels, we find the private IR function to be the main driver of our results.

Keywords: Investor relations, Financial markets, COVID-19, Institutional investors

1. Introduction

Communication with investors has become increasingly important due to the globalization of capital markets and the large amount of unvetted news and opinions about firms on the internet. The latter shape investors’ perceptions and can significantly influence the firms’ valuation (Bartov, Faurel, Mohanram, 2018, Chapman, Miller, White, 2019, Lee, Hutton, Shu, 2015, Schmidt, 2020). Helping investors and analysts to evaluate information and communicating the firm’s strategy in order to reduce uncertainty and information frictions is a key task, typically carried out by the firms’ investor relations (IR) departments. Accordingly, the US National Investor Relations Institute (NIRI) defines IR as a strategic management responsibility supposed “[... ] to enable the most effective two-way communication between a company, the financial community, and other constituencies, which ultimately contributes to a company’s securities achieving fair valuation” (NIRI, 2020). Although some studies have already highlighted that firms with strong IR have better capital market outcomes (see e.g., Brennan, Tamarowski, 2000, Brochet, Limbach, Bazhutov, Betzer, Doumet, 2021, Bushee, Miller, 2012, Chapman, Miller, White, 2019, Karolyi, Kim, Liao, 2020, Kirk, Vincent, 2014), our understanding of whether this is particularly true or even stronger during times when uncertainty among investors is high, is still limited. In this paper, we therefore use a large sample of European firms to investigate whether firms with strong IR outperformed firms with weak IR when stock markets collapsed as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic.

The COVID-19 pandemic and the subsequent economic lockdown in many European countries can be seen as a perfect example of an exogenous and unexpected shock, which led to enormous uncertainty on capital markets (see e.g., Altig, Baker, Barrero, Bloom, Bunn, Chen, Davis, Leather, Meyer, Mihaylov, et al., 2020, Baker, Bloom, Davis, Terry, 2020, Engelhardt, Krause, Neukirchen, Posch, 2020, Zhang, Hu, Ji, 2020). While European stock markets were thriving until mid-February 2020, the markets dropped by roughly until the end of March 2020 (see Fig. 1 ). Consequently, a lot of rumors appeared in press and online about firms’ ability to manage the crisis. This might have overburdened market participants with limited information processing capabilities and led to information frictions (see e.g., Hirshleifer, Teoh, 2003, Merton, 1987, Peng, Xiong, 2006). We hypothesize that if a firm’s IR helps to alleviate uncertainty and to reduce information frictions, it should particularly pay off during times when market participants are unsettled. The COVID-19 pandemic provides us with such an opportunity and thus allows to examine the relation between the quality of a firm’s IR and its market valuation.

Fig. 1.

Evolution of the STOXX Europe 600 stock market index. This figure shows the STOXX Europe 600 stock market index for the period from January 3, 2020 to September 30, 2020. The collapse period (gray-shaded area) as defined in Fahlenbrach et al. (2021) is from February 3, 2020 to March 23, 2020.

To do so, we use the 2020’s IR rankings for roughly 1,000 European firms from 16 different countries provided by Institutional Investor1 and stock and accounting data from Compustat/Capital IQ and Thomson Reuters Eikon. In univariate tests, we find High IR firms, i.e., those having an IR score above the country median, to experience 7.09 percentage points higher cumulative returns after the crisis unfolded in mid-March 2020. We also find that this difference holds until the end of our observation period in October 2020, which is a first indication of IR being valuable for firms during times of crisis.

To further test whether IR might have paid off during the COVID-19 crisis, we estimate various multivariate specifications. In our baseline specifications, we use either the cumulative raw stock returns or the cumulative abnormal stock returns over the period from February 3 to March 23, 2020, which is the collapse period as defined in Fahlenbrach et al. (2021) 2 , as the dependent variable and both dummy variables and the raw IR scores as the main independent variables. The results from these tests are consistent with our hypothesis and provide evidence of a positive association between a firm’s IR quality and its stock performance during the collapse period. For instance, we find that firms with strong IR experienced at least 4.72 percentage points higher cumulative returns when stock markets collapsed. Our results are robust to controlling for industry and country-fixed effects, a variety of firm and governance characteristics used in related settings (see e.g., Albuquerque, Koskinen, Yang, Zhang, 2020, Fahlenbrach, Rageth, Stulz, 2021, Lemmon, Lins, 2003, Lins, Volpin, Wagner, 2013, Lins, Servaes, Tamayo, 2017, Mitton, 2002), as well as to using an entropy balanced sample.

However, while the inclusion of industry and country-fixed effects and the use of entropy balancing helps us to condition out time-invariant unobservable systematic differences between firms in different industries and countries as well as observable systematic differences between firms with strong IR and those with weak IR, there may also be time-invariant unobservable firm characteristics as well as time-varying economy and industry traits (e.g., policy reactions to the crisis) affecting our results. To account for this, we estimate regressions similar to Ding et al. (2021) where the dependent variable is the firm’s weekly stock return over the entire year 2020 and where we interact each independent variable, including our measures for the firm’s level of IR, with the weekly growth in confirmed COVID-19 cases. This setting has the advantage that it allows us to include firm, industry-time, and economy-time-fixed effects and thus to rule out these potential concerns. But despite employing this different setting, the results from these regressions strengthen our previous findings.

To support our hypothesis and to specifically examine whether having better-quality IR became even more valuable as the crisis unfolded, we also perform two further tests. Following Albuquerque et al. (2020) and Ramelli and Wagner (2020), we first estimate daily cross-sectional regressions of the firms’ cumulative abnormal returns during the first quarter of 2020 on our measures for a firm’s IR quality and find that the loading on the coefficient increases late-February to mid-March. Thereafter, the loading on the coefficient stagnates.

Second, we follow Lins et al. (2017) and Albuquerque et al. (2020) by using a difference-in-differences analysis. Specifically, we construct a panel of daily abnormal returns and estimate a difference-in-differences regression where the dependent variable is the daily abnormal return and the main independent variable of interest is the interaction between our dummy variable High IR and an event date dummy equalling one for all dates in the crisis period, and zero otherwise. We also include an interaction between High IR and an event date dummy equalling one for all dates after the initial shock to capture the impact of IR during the recovery period. But consistent with our previous findings, we also find firms with strong IR to experience higher crisis returns in this test.

We next seek to identify which functions of a firm’s IR caused the outperformance of strong IR firms compared to weak IR firms during the crisis period. To do so, we follow Brochet et al. (2021) and decompose a firm’s IR score into a public and a private component. Rerunning our previous analyses with these scores shows that a firm’s private IR is positively associated with the stock performance during the crisis period, whereas a firm’s public IR does not appear to contribute to the outperformance of firms with better-quality IR. This finding is striking given that Brochet et al. (2021) stress that both functions contribute to better capital market outcomes. However, we interpret our result in the context of the crisis. An article in the IR Magazine (2020), for example, provides some anecdotal evidence that private IR functions, such as organizing meetings with senior management, have been of particular importance to investors during the crisis. Besides, the COVID-19 crisis posed great challenges to a firms public IR activities due to the potential risk of infection, which might also explain this result.

While our main tests focus on providing evidence that firms with better-quality (private) IR outperformed those with lower-quality (private) IR, we also examine how a firm’s IR functions might have boosted its firm value. One explanation for the return premium could be that (private) IR helps to enhance a firm’s credibility with its shareholders. Another explanation could be related to IR helping to diversify a firm’s shareholder base, which could have also led to lower stock volatility during the crisis. To test the first explanation, we regress the fraction of incumbent institutional investors staying loyal to the firm over the crisis period on our measures for IR quality. Our results provide evidence that institutional investor loyalty is higher at firms with better-quality (private) IR. This suggests strong IR to enhance a firm’s credibility. To examine the second explanation, we regress the change in the number of institutional investors over the crisis period as well as the idiosyncratic stock volatility on our measures for IR quality. We find the change in the number of institutional investors to be more positive and volatility during the crisis period to be indeed slightly lower for strong (private) IR firms. Collectively, these findings therefore highlight that a firm’s IR function might have boosted its firm value by both enhancing its credibility with its shareholders and by diversifying its shareholder base.

In some additional tests, we also check whether firms in industries particularly affected by the COVID-19 pandemic benefited even more from having better IR and whether there is a link between the value of IR during the crisis and the countries the firms are headquartered in. While we do not find that IR payed off more in industries particularly affected by the crisis, we find considerable variation in the value of IR depending on certain country characteristics. Following Karolyi et al. (2020), we investigate this by splitting the sample based on the median scores on several country characteristics and rerunning our baseline regression on the respective subsamples. Our results show that, consistent with Karolyi et al. (2020), firms with strong IR domiciled in countries, where lower-quality legal institutions prevail, experienced significantly higher abnormal returns during the collapse period compared to those domiciled in countries with higher-quality legal institutions. Further, we find that better-quality IR was even more valuable in countries where the level of societal trust is weak and where people have difficulties in dealing with uncertainty. We also rerun these analyses using the decomposed scores and find, consistent with our previous findings, a firm’s private IR function to be the main driver of the results.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows: Section 2 provides a literature review. Section 3 describes the data and variables. Section 4 presents our empirical analysis and the results, while Section 5 presents additional tests. In Section 6, we check the robustness of our results. Section 7 concludes.

2. Literature review and contribution

Our contribution to the literature is twofold. First, we contribute to the literature on the impact of IR on corporate outcomes. In this regard, prior studies primarily focusing on the US market have shown a positive association between a firm’s IR and its capital market outcomes. For instance, employing IR magazine ratings of investor relations, Agarwal et al. (2008) show higher-rated firms to experience higher abnormal returns surrounding their rating announcements. Bushee and Miller (2012) use a sample of US small and mid-cap firms, which have initiated an IR program, to show a positive association between a firm’s IR activities and its market value (in terms of reductions in the book-to-price ratio). They also highlight that these firms attract more institutional investors. Similar findings are provided by Kirk and Vincent (2014), who focus on US firms having initiated internal professional IR. Chapman et al. (2019) study whether IR officers are valuable to firms since they might help investors and analysts to evaluate information. Their findings indicate that US firms with IR officers have better capital market outcomes, i.e., lower stock volatility and lower forecast dispersion. Further, Chahine et al. (2020) show that hiring IR consultants prior to going public increases news coverage and is associated with higher first-day returns, while Hope et al. (2021) show that hiring Wall Street analysts as IR officers is beneficial. Besides, there is also evidence by Crifo et al. (2019) and Hockerts and Moir (2004) linking the firm’s corporate social responsibility (CSR) performance to IR. Karolyi et al. (2020) use survey data of IR officers from 59 countries to show a positive relation between a firm’s IR efforts and its market valuation measured by Tobin’s Q. They highlight that a firm’s IR efforts are related to legal protection, disclosure standards, and media visibility. Brochet et al. (2021) use the IR rankings provided by Institutional Investor (formerly called Extel) for the period from 2014 through 2018 and find a positive association between a firm’s IR efforts and its market valuation. Also, they document that firms with strong IR have greater firm visibility and that the overall benefits of IR vary between insider and outsider-oriented markets. Recently, Chapman et al. (2021) also show that IR appears to deter shareholder activism.

Although all of these studies provide evidence indicating a positive association between IR and a firm’s capital market outcomes, our study is the first to test the link during a crisis period. Our results imply that only a firm’s private IR activities are positively associated with a firm’s stock performance during the crisis and that a firm’s IR functions appear to boost its firm value through both enhancing credibility with its shareholders and through diversifying its shareholder base.

Second, we contribute to the ongoing literature on characteristics making firms more immune and resilient during times of crisis, and in particular during the COVID-19 crisis. Most of the recent studies, however, focus on the US stock market. For instance, Fahlenbrach et al. (2021) find US firms with high financial flexibility to experience higher returns during the crisis. Ramelli and Wagner (2020) find that this was particularly true for non-financial firms. A paper by Albuquerque et al. (2020), which we closely relate to in terms of methodology, shows US firms with higher environmental and social ratings to experience higher stock returns and less volatility. Further, Landier and Thesmar (2020) highlight that the decline in stock prices during the COVID-19 crisis can be explained by analysts’ forecast revisions. Acharya and Steffen (2020) document that US firms with a lower credit-rating were particularly affected during the COVID-19 crisis, while Pagano et al. (2020) show that US firms more resilient to social distancing are associated with higher stock returns. Finally, Alfaro et al. (2020) demonstrate that US firms were less affected by the crisis if they were able to shed costs.

One of the few studies focusing on cross-country data is Ding et al. (2021). Similar to Fahlenbrach et al. (2021) and Ramelli and Wagner (2020), they demonstrate that firms with high financial flexibility are associated with a lower decline in stock prices. Besides, they show that the drop in a firm’s stock price was lower if the firm was more active in CSR and had less entrenched executives. Finally, Cheema-Fox et al. (2020) also employ cross-country data to show that stock price reactions are associated with the sentiment around firms’ responses (in terms of layoffs, supply chain, products, and services).

We contribute to this strand of literature by showing that, in a cross-country setting, firms with strong IR experienced higher stock returns and were thus more resilient during the COVID-19 crisis.

3. Data and variables

3.1. Sample construction

We obtain information on IR rankings for over 1,000 publicly-traded companies from 16 European countries for the year 2020. These rankings, provided by Institutional Investor (historically called Extel), are based on a large survey where buy and sell-side institutions were asked to rate on the perceived quality of the firms’ IR programs.3 The respondents, which are almost evenly distributed between the buy and sell-side, were particularly asked to evaluate the firms’ communication with investors (i.e., the productivity of road shows and meetings, the quality of conference calls, the access to senior management, the firms’ responsiveness, the authority and credibility of the IR team and its business and market knowledge, the quality of investor events, and the quality of the firms’ Environmental and Social (ES) reporting) as well as the firms’ financial disclosure practices (i.e., the time to market, the granularity as well as the comparability and consistency of financial disclosures). Unfortunately, there is no data on the different sub-dimensions of the IR activities available, but Institutional Investor provides scores as well as ranks for each firm within a country based on the percentage of respondents voting for a particular firm. We then merge these scores with stock and accounting data from Compustat/Capital IQ and with ownership data, governance data, data on a firm’s informational environment, and ES ratings for the year 2019 from Thomson Reuters Eikon. Additionally, we obtain data on a firm’s news environment from Dow Jones Factiva.

3.2. Key variables

Our main independent variable of interest is High IR, which is a dummy variable equalling one if the firm’s IR score is larger than the median score within the respective country, and zero otherwise. We thereby account for the fact that the scores provided by Institutional Investor are scaled on country-level. In additional regressions, we also employ the natural logarithm of the raw IR score as the main independent variable of interest.

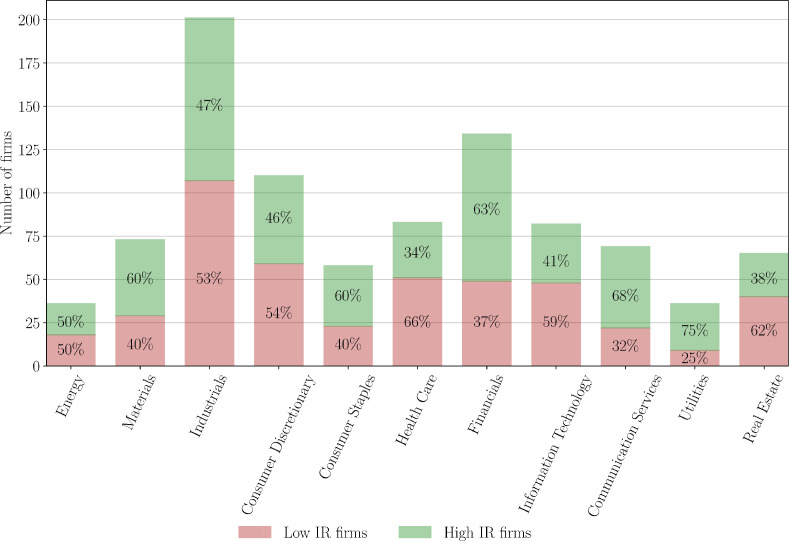

For a more detailed view on our main variable of interest High IR, we report the number and the proportion of High IR and Low IR firms in the respective industry sectors based on the Global Industry Classification Standards (GICS) 11 sectors in Fig. 2 . For instance, we observe 201 firms located in the Industrials sector, where we find that 47% of the firms are classified as High IR firms and 53% of the firms are classified as Low IR firms. Furthermore, it is noteworthy that 75% of the firms in the Utilities sector are High IR firms.

Fig. 2.

Distribution of High IR and Low IR firms by industry. This figure shows the number of High IR and Low IR firms in the respective industry sectors based on the Global Industry Classification Standard’s (GICS) 11 sectors. We report the proportion of High IR firms and the proportion of Low IR firms in percentages.

Since we are interested in studying whether firms with strong IR had better stock performance during the COVID-19 crisis, we mainly employ the cumulative raw stock returns as well as the cumulative abnormal stock returns based on a market model estimation4 as our dependent variables. Following Fahlenbrach et al. (2021), we specifically calculate cumulative returns for the period from February 3 through March 23, 2020, which is the so-called “collapse period” where stock prices declined dramatically. Although Fahlenbrach et al. (2021) focus on the US stock market, we find the same pattern on European stock markets. While mean daily stock returns are negative during the collapse period, we find a positive mean return of on March 24, 2020, which is the day the market was informed that the approval of the two trillion US dollar coronavirus stimulus bill was likely. So, European markets also reacted strongly to the news about the US government’s policy response.

In terms of control variables, we mainly follow the existing literature (see e.g., Albuquerque, Koskinen, Yang, Zhang, 2020, Brochet, Limbach, Bazhutov, Betzer, Doumet, 2021, Fahlenbrach, Rageth, Stulz, 2021, Glossner, Matos, Ramelli, Wagner, 2020, Lins, Servaes, Tamayo, 2017, Karolyi, Kim, Liao, 2020). We describe the construction of these variables in detail in Table A.1 in the appendix.

3.3. Summary statistics

Our final sample consists of 947 firms from 16 European countries for which we have stock data available. Table A.2 in the appendix holds a list of countries covered. However, some of the control variables are missing for certain observations. This is why we estimate different regression models in our analysis. Taking this into account, Table 1 provides basic summary statistics for the variables in our sample and Table A.3 in the appendix reports the respective correlations.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics. This table reports descriptive statistics for our sample consisting of 947 firms from 16 European countries. The survey-based IR rankings come from Institutional Investor. Stock data and accounting data come from Compustat/Capital IQ. Corporate ES ratings, governance data, data on a firm’s informational environment, and ownership data come from Thomson Reuters Eikon. All variables are defined in detail in Table A.1 in the appendix. Table A.2 in the appendix reports the number of firms per country.

| Observations | Minimum | Maximum | Mean | Median | Std. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent Variables: | ||||||

| Abnormal Returns | 947 | −1.9940 | 0.6145 | −0.1444 | −0.1282 | 0.2815 |

| Raw Returns | 947 | −2.1291 | 0.3906 | −0.4558 | −0.4338 | 0.2672 |

| Main Variable of Interest: | ||||||

| (IR Score) | 947 | −4.5816 | −1.4312 | −3.8985 | −4.0763 | 0.5998 |

| Control Variables: | ||||||

| Size | 749 | 2.0947 | 11.9168 | 7.9400 | 7.9933 | 1.8247 |

| ROE | 932 | −0.4715 | 0.2548 | 0.0389 | 0.0434 | 0.0852 |

| Tobin’s Q | 932 | 0.7466 | 14.7823 | 2.1118 | 1.3301 | 2.1365 |

| Market-to-Book | 932 | −2.9155 | 46.7297 | 3.9440 | 2.0376 | 6.4184 |

| Historical Volatility | 947 | 0.1255 | 0.7547 | 0.2869 | 0.2613 | 0.1120 |

| Cash / Assets | 749 | 0.0039 | 0.6416 | 0.1213 | 0.0918 | 0.1135 |

| Short-term Debt / Assets | 921 | 0 | 0.2397 | 0.0520 | 0.0374 | 0.0501 |

| Long-term Debt / Assets | 938 | 0 | 0.6937 | 0.2202 | 0.2009 | 0.1584 |

| Momentum | 947 | −2.3754 | 0.8764 | −0.4487 | −0.3652 | 0.6681 |

| Analyst Following | 941 | 0 | 3.4340 | 2.4430 | 2.5649 | 0.6928 |

| Blockholder | 906 | 0.0515 | 0.8500 | 0.3713 | 0.3479 | 0.2072 |

| Institutional Ownership | 939 | 0.0753 | 0.9694 | 0.5647 | 0.5880 | 0.2215 |

| US Listing | 947 | 0 | 1 | 0.0570 | 0 | 0.2320 |

| High ES | 772 | 0 | 1 | 0.5000 | 0 | 0.5003 |

| Board Size | 771 | 3 | 21 | 10.4786 | 10 | 3.6953 |

| Board Independence | 761 | 0 | 1 | 0.5873 | 0.6000 | 0.2612 |

| Board Governance Score | 761 | 0.0729 | 0.9488 | 0.5594 | 0.5789 | 0.2224 |

The descriptive statistics show that mean and median cumulative raw returns over the collapse period are highly negative amounting to approximately −45.58% and −43.38%, respectively. The standard deviation is 26.72%; thus cumulative returns exhibit large variation. In fact, the numbers are almost identical to those reported in Fahlenbrach et al. (2021). Also, mean and median cumulative abnormal returns are negative. The mean of the natural logarithm of the IR score amounts to −3.90. Regarding control variables, we find that the average firm size in terms of total sales amounts to $11.31 billion. Further, the average firm in our sample has a return on equity of 3.89%, a market-to-book ratio of 3.94, and a cash-to-assets ratio of 12.13%.

4. Empirical analysis and results

4.1. Baseline results

To study whether firms with better IR had higher stock returns during the COVID-19 crisis, we first perform a univariate analysis. Similar to Fahlenbrach et al. (2021), we compare the evolution of cumulative raw stock returns between groups of firms with strong IR and those with weak IR. To classify firms, we use our dummy variable High IR. Figure 3 shows the results.

Fig. 3.

Evolution of stock returns for High IR and Low IR firms. This figure shows the evolution of daily logarithmic stock returns of different samples for the period from January 1, 2020 to September 23, 2020. We consider all firms in our sample and two subsamples consisting of High IR firms and Low IR firms. We classify firms using the median IR Score within the respective country.

Figure 3 indicates that the difference in cumulative returns widens when stock markets collapsed in mid-March 2020 and that this difference holds until the end of our observation period in October 2020. While the difference in mean cumulative returns between firms with strong IR and those with weak IR is almost zero at the beginning of the year, we find firms with strong IR to experience on average 6.42 percentage points higher cumulative returns (as of September 30, 2020) after the COVID-19 crisis unfolded. This suggests that reducing uncertainty and information frictions among investors through effective IR appears to be valuable.

To test whether these first results also hold in multivariate specifications, we perform various ordinary least squares (OLS) regressions as defined below:

| (4.1) |

where denotes the firm. We measure stock performance using either the cumulative raw stock returns or the cumulative abnormal stock returns for the period from February 3 to March 23, 2020, which is the collapse period as defined in Fahlenbrach et al. (2021). The main independent variable of interest in our regressions is the dummy variable High IR. We also control for a variety of firm characteristics denoted by the vector . The terms and , respectively, denote industry-fixed effects (based on the GICS 11 sectors) and country-fixed effects. stands for the error term. Following Lins et al. (2013) and Petersen (2009), we cluster standard errors by country to account for the possibility that firm characteristics are correlated between firms within a country.5 Table 2 presents the results.

Table 2.

IR and crisis-period returns. This table presents the results from OLS regressions. In Panel A, the dependent variable is a firm’s cumulative raw stock return for the period from February 3, 2020 to March 23, 2020, which is the collapse period as defined in Fahlenbrach et al. (2021). The main independent variable of interest is High IR, which equals one if the firm’s IR score is larger than the median IR score within the respective country. Across all columns, we control for industry-fixed effects based on the Global Industry Classification Standard’s (GICS) 11 sectors. In columns (2) to (4), we include country-fixed effects. In columns (3) and (4), we additionally include controls for a variety of firm characteristics. Finally, in column (4) we also include several board characteristics and the dummy variable High ES to control for firms with high ES ratings. All variables are described in detail in Table A.1 in the appendix. In Panel B, the dependent variable is a firm’s cumulative abnormal return (based on market model estimations) for the period from February 3, 2020 to March 23, 2020. The regression specifications are similar to those in Panel A. Across all panels, we report robust standard errors clustered by country in parentheses, with , , denoting statistical significance at the , , and level.

| Panel A: | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent Variable: Raw returns | ||||

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

| High IR | 0.0579 | 0.0626 | 0.0803 | 0.0472 |

| (0.0189) | (0.0205) | (0.0199) | (0.0275) | |

| Size | −0.0080 | −0.0111 | ||

| (0.0107) | (0.0139) | |||

| ROE | 0.2763 | 0.3699 | ||

| (0.2860) | (0.2749) | |||

| Tobin’s Q | 0.0227 | 0.0213 | ||

| (0.0057) | (0.0062) | |||

| Market-to-Book | −0.0016 | −0.0033 | ||

| (0.0020) | (0.0026) | |||

| Historical Volatility | ||||

| (0.1260) | (0.1512) | |||

| Cash / Assets | 0.0488 | 0.0973 | ||

| (0.0830) | (0.0921) | |||

| Short-term Debt / Assets | −0.1830 | −0.2975 | ||

| (0.1965) | (0.2282) | |||

| Long-term Debt / Assets | ||||

| (0.0715) | (0.0681) | |||

| Momentum | 0.0343 | 0.0551 | ||

| (0.0143) | (0.0150) | |||

| Analyst Following | −0.0283 | 0.0135 | ||

| (0.0285) | (0.0257) | |||

| Blockholder | 0.0422 | 0.0675 | ||

| (0.0501) | (0.0525) | |||

| Institutional Ownership | 0.0268 | 0.0327 | ||

| (0.0448) | (0.0456) | |||

| US Listing | 0.0990 | 0.0660 | ||

| (0.0213) | (0.0282) | |||

| High ES | 0.0698 | |||

| (0.0385) | ||||

| Board Size | −0.0040 | |||

| (0.0035) | ||||

| Board Independence | 0.0182 | |||

| (0.0351) | ||||

| Board Governance Score | ||||

| (0.0291) | ||||

| Observations | 947 | 947 | 710 | 558 |

| Industry Fixed Effects | yes | yes | yes | yes |

| Country Fixed Effects | no | yes | yes | yes |

| Adjusted R-Squared | 0.15 | 0.17 | 0.31 | 0.33 |

| Panel B: | ||||

| Dependent Variable: Abnormal returns | ||||

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

| High IR | 0.1186 | 0.1248 | 0.0996 | 0.0689 |

| (0.0200) | (0.0216) | (0.0208) | (0.0261) | |

| Size | 0.0103 | 0.0064 | ||

| (0.0127) | (0.0117) | |||

| ROE | 0.3741 | 0.3490 | ||

| (0.2763) | (0.3214) | |||

| Tobin’s Q | 0.0275 | 0.0235 | ||

| (0.0056) | (0.0067) | |||

| Market-to-Book | −0.0012 | −0.0012 | ||

| (0.0017) | (0.0023) | |||

| Historical Volatility | −0.0925 | −0.0326 | ||

| (0.1399) | (0.1632) | |||

| Cash / Assets | 0.0815 | 0.1032 | ||

| (0.0689) | (0.0812) | |||

| Short-term Debt / Assets | −0.2268 | |||

| (0.1882) | (0.2187) | |||

| Long-term Debt / Assets | ||||

| (0.0640) | (0.0660) | |||

| Momentum | ||||

| (0.0110) | (0.0165) | |||

| Analyst Following | 0.0150 | 0.0501 | ||

| (0.0305) | (0.0238) | |||

| Blockholder | −0.0296 | 0.0198 | ||

| (0.0479) | (0.0544) | |||

| Institutional Ownership | 0.0057 | 0.0119 | ||

| (0.0464) | (0.0390) | |||

| US Listing | 0.0997 | 0.0828 | ||

| (0.0205) | (0.0265) | |||

| High ES | 0.0422 | |||

| (0.0403) | ||||

| Board Size | −0.0021 | |||

| (0.0032) | ||||

| Board Independence | 0.0187 | |||

| (0.0351) | ||||

| Board Governance Score | ||||

| (0.0417) | ||||

| Observations | 947 | 947 | 710 | 558 |

| Industry Fixed Effects | yes | yes | yes | yes |

| Country Fixed Effects | no | yes | yes | yes |

| Adjusted R-Squared | 0.14 | 0.18 | 0.29 | 0.29 |

In Panel A, we use the firms cumulative raw stock return as the dependent variable and High IR as our independent variable of interest. Across all columns, we find positive and highly statistically significant coefficients on High IR. The coefficients are also comparable in size regardless of whether we control for industry-fixed effects only (column (1)), industry and country-fixed effects (column (2)), or industry and country-fixed effects as well as for further firm (column (3)) and governance characteristics (column (4)). The two reasons why we control for governance characteristics are that (I) a firm’s IR activities could complement or substitute some aspects of corporate governance, and that (II) recent research suggests well-governed firms to perform better during times of crisis (Lins, Volpin, Wagner, 2013, Nguyen, Nguyen, Yin, 2015). Considering that we still find a positive and statistically significant association after controlling for all of these factors, we can conclude that firms with strong IR experienced on average at least 4.72 percentage points higher returns when stock markets collapsed. This is an economically sizeable effect. In terms of control variables, we also find positive and statistically significant coefficients on Momentum, Tobin’s Q, US Listing and High ES, and negative and statistically significant coefficients on Historical Volatility, Long-term Debt / Assets and Board Governance Score. These results are mainly in line with the related literature showing firms with stronger ES performance, higher financial flexibility, and better past performance to experience higher returns during the COVID-19 crisis (see e.g., Albuquerque, Koskinen, Yang, Zhang, 2020, Ding, Levine, Lin, Xie, 2021, Fahlenbrach, Rageth, Stulz, 2021). Interestingly, we also find that well-governed firms appear to have performed worse and that there is no significant relationship between a firm’s stock performance during the crisis and its cash holdings, ownership structure, or its informational environment.6

In Panel B, we run the same regressions using a firms cumulative abnormal stock return (based on a market model estimation) as the dependent variable and High IR as our independent variable of interest. Again, we find positive and highly statistically significant coefficients on High IR across all columns; thus strengthening our findings from Panel A. As a matter of fact, adjusting for firm risk leads to larger magnitudes of the coefficients on High IR. Firms with better-quality IR are associated with at least 6.89 percentage points higher abnormal returns compared to those with lower-quality IR. Regarding our control variables, the results show a similar picture to the one found in Panel A, except for the negative coefficient on Momentum and the positive and statistically significant coefficient on Analyst Following in column (4). Also, statistical significance vanishes to some extent regarding the Board Governance Score.

To ensure that our results also hold when we use alternative measures for a firm’s IR quality, we rerun the same regressions as in Panel B of Table 2 but use the natural logarithm of the raw IR scores, dummy variables for each IR quartile, and the residuals from a first stage regression as our main independent variables of interest. Table 3 presents the results where we do not report the coefficients on the control variables for reasons of brevity.

Table 3.

Alternative IR measures and crisis-period returns. This table presents the results from OLS regressions. In Panel A, the dependent variable is a firm’s cumulative abnormal stock return for the period from February 3, 2020 to March 23, 2020, which is the collapse period as defined in Fahlenbrach et al. (2021). The main independent variable of interest is log(IR Score), which is the natural logarithm of the raw IR score. In Panel B, we use the cumulative abnormal return as the dependent variable and dummy variables for the IR quartiles per country. IR Score Q2 takes the value of one if the firm is in the second IR quartile and zero otherwise, IR Score Q3 takes the value of one if the firm is in the third IR quartile and zero otherwise, and IR Score Q4 takes the value of one if the firm is in the fourth IR quartile and zero otherwise. In Panel C, the dependent variable is the cumulative abnormal return and the main independent variable is IR Residuals, which is the residual from a first stage regression where the dependent variable is the log(IR Score) and the main independent variables are measures for firm performance, firm age, and firm visibility. Across all panels, we control for industry-fixed effects based on the Global Industry Classification Standard’s (GICS) 11 sectors in all regressions. We include country-fixed effects in columns (2) to (4). In columns (3) and (4), we additionally include controls for a variety of firm and board characteristics (not reported but similar to those used in Table 2). All variables are described in detail in Table A.1 in the appendix. Across all panels, we report robust standard errors clustered by country in parentheses, with , , denoting statistical significance at the , , and level.

| Panel A: | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent Variable: Abnormal returns | ||||

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

| (IR Score) | 0.0846 | 0.1544 | 0.1488 | 0.1155 |

| (0.0259) | (0.0208) | (0.0222) | (0.0245) | |

| Observations | 947 | 947 | 710 | 558 |

| Firm Characteristics | no | no | yes | yes |

| Board Characteristics | no | no | no | yes |

| Industry Fixed Effects | yes | yes | yes | yes |

| Country Fixed Effects | no | yes | yes | yes |

| Adjusted R-Squared | 0.13 | 0.18 | 0.29 | 0.29 |

| Panel B: | ||||

| Dependent Variable: Abnormal returns | ||||

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

| IR Score 2 | 0.0678 | 0.0616 | 0.0668 | 0.0588 |

| (0.0350) | (0.0327) | (0.0258) | (0.0275) | |

| IR Score 3 | 0.1217 | 0.1254 | 0.1173 | 0.0879 |

| (0.0329) | (0.0338) | (0.0344) | (0.0407) | |

| IR Score 4 | 0.1839 | 0.1860 | 0.1768 | 0.1373 |

| (0.0371) | (0.0366) | (0.0245) | (0.0367) | |

| Observations | 947 | 947 | 710 | 558 |

| Firm Characteristics | no | no | yes | yes |

| Board Characteristics | no | no | no | yes |

| Industry Fixed Effects | yes | yes | yes | yes |

| Country Fixed Effects | no | yes | yes | yes |

| Adjusted R-Squared | 0.15 | 0.19 | 0.29 | 0.28 |

| Panel C: | ||||

| Dependent Variable: Abnormal returns | ||||

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

| IR Residuals | 0.1345 | 0.1345 | 0.1303 | 0.1278 |

| (0.0188) | (0.0188) | (0.0287) | (0.0295) | |

| Observations | 900 | 900 | 684 | 535 |

| Firm Characteristics | no | no | yes | yes |

| Board Characteristics | no | no | no | yes |

| Industry Fixed Effects | yes | yes | yes | yes |

| Country Fixed Effects | no | yes | yes | yes |

| Adjusted R-Squared | 0.13 | 0.16 | 0.29 | 0.29 |

In Panel A, we report the results from regressions where we use the firms' cumulative abnormal stock return as the dependent variable and the natural logarithm of the raw IR scores as the main independent variable. Similar to our previous results, we find firms with higher-quality IR to be associated with higher abnormal stock returns during the crisis. Interestingly, controlling for country-fixed effects (columns (2) to (4)) does not only lead to an improvement in terms of fit but also to a significant increase in magnitude of the coefficient on log(IR Score). However, controlling for further firm and governance characteristics (columns (3) and (4)) does not change the magnitude of the coefficient significantly.

In Panel B, we show the results from regressions where the dependent variable is the firms cumulative abnormal stock return and where we divide firms into IR quartiles. This approach helps us to analyze whether the positive association between a firm’s IR quality and the abnormal stock returns during the crisis is more pronounced at very high or very low levels. In each regression, we therefore include the dummy variables IR Score Q2 (taking the value of one if the firm is in the second IR quartile), IR Score Q3 (taking the value of one if the firm is in the third IR quartile), and IR Score Q4 (taking the value of one if the firm is in the fourth IR quartile). The intercept captures the effect of firms in the first quartile. Consistent with our previous findings, we find firms with better IR to experience higher abnormal returns during the crisis. Particularly, the results show that the difference in abnormal returns between firms in the best quartile and those in the worst quartile is at least 13.73 percentage points. This is an economically sizeable effect considering that mean cumulative abnormal returns amount to −14.44%. Furthermore, it is noteworthy that although the relation between IR and the cumulative abnormal returns during the collapse period is monotonic, it is not completely linear when we control for further governance characteristics. For instance, we find firms in the second quartile to experience almost 6 percentage points higher abnormal returns compared to those in the first quartile. However, the results show only a 2.91 percentage points improvement when firms are in the third quartile (compared to those in the second quartile), and another 4.94 percentage points improvement when firms are in the best quartile. We can therefore conclude that those firms with very weak IR were particularly affected during the COVID-19 crisis.

Finally, in Panel C, we use the residuals from a first stage regression as the main independent variable of interest. In the first stage regression, the dependent variable is the natural logarithm of the raw IR score, and the independent variables are measures for firm performance, firm age, and media coverage. The first stage regression also includes industry and country-fixed effects and exhibits an R-squared of roughly 70%. By employing this approach, we aim to address the issue that the IR score might be primarily driven by past performance and firm visibility and not by the firm’s IR activities. However, the results remain robust even when using the residuals, i.e., the part that is not explained by the above-mentioned characteristics.7

4.2. Addressing endogeneity concerns

Although our baseline regressions provide consistent evidence that firms with better-quality IR had higher crisis-period returns, we cannot completely rule out that a firm’s IR and its performance are endogenously determined. For instance, firms with better-quality IR might be systematically different from firms with lower-quality IR in terms of other observable firm characteristics such that these differences are affecting our results. We alleviate this concern by employing entropy balancing, which is a data preprocessing method where weights are calculated to achieve covariate balance between treatment and control groups (Hainmueller, 2012). As opposed to propensity score matching, which is also commonly used in these contexts, entropy balancing provides the added benefit of not reducing the sample size. We display the results employing this approach in Table 4 .

Table 4.

Entropy balanced sample and weighted regressions. This table presents the covariate balance for an entropy balanced sample where the treatment variable is High IR (Panel A) and the results from weighted linear regressions (Panel B). The dependent variable in the regressions is a firm’s cumulative abnormal stock return for the period from February 3, 2020 to March 23, 2020, which is the collapse period as defined in Fahlenbrach et al. (2021). The main independent variable of interest is High IR and both regressions also include industry and country-fixed effects. All variables are described in detail in Table A.1 in the appendix. We report robust standard errors clustered by country in parentheses, with , , denoting statistical significance at the , , and level.

|

Panel A: | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-Match |

Post-Match |

|||||

| Treatment | Control | Diff. | Treatment | Control | Diff. | |

| Size | 8.5684 | 7.2303 | 1.3381 | 8.5684 | 8.5680 | 0.0004 |

| ROE | 0.0401 | 0.0167 | 0.0234 | 0.0401 | 0.0401 | 0.0000 |

| Tobin’s Q | 2.4331 | 2.2249 | 0.2082 | 2.4331 | 2.4330 | 0.0001 |

| Market-to-Book | 4.6888 | 4.3613 | 0.3275 | 4.6888 | 4.6885 | 0.0003 |

| Historical Volatility | 0.2757 | 0.3231 | 0.2757 | 0.2758 | −0.0001 | |

| Cash / Assets | 0.1120 | 0.1285 | 0.1120 | 0.1120 | 0.0000 | |

| Short-term Debt / Assets | 0.0495 | 0.0532 | −0.0037 | 0.0495 | 0.0495 | 0.0000 |

| Long-term Debt / Assets | 0.2326 | 0.2148 | 0.0178 | 0.2326 | 0.2326 | 0.0000 |

| Momentum | −0.4294 | −0.5360 | 0.1066 | −0.4294 | −0.4294 | 0.0000 |

| Analyst Following | 2.7919 | 2.1323 | 0.6596 | 2.7919 | 2.7918 | 0.0001 |

| Blockholder | 0.3412 | 0.4153 | 0.3412 | 0.3412 | 0.0000 | |

| Institutional Ownership | 0.5785 | 0.5899 | −0.0114 | 0.5785 | 0.5785 | 0.0000 |

| US Listing | 0.0831 | 0.0201 | 0.0630 | 0.0831 | 0.0831 | 0.0000 |

| Panel B: | ||||||

| Dependent Variable: Abnormal returns | (1) | (2) | ||||

| High IR | 0.0590 | 0.0513 | ||||

| (0.0215) | (0.0251) | |||||

| Size | −0.0187 | |||||

| (0.0131) | (0.0109) | |||||

| ROE | 0.5800 | 0.5010 | ||||

| (0.1550) | (0.2590) | |||||

| Tobin’s Q | 0.0197 | 0.0134 | ||||

| (0.0070) | (0.0062) | |||||

| Market-to-Book | −0.0035 | |||||

| (0.0018) | (0.0026) | |||||

| Historical Volatility | ||||||

| (0.1290) | (0.1630) | |||||

| Cash / Assets | −0.0631 | −0.0515 | ||||

| (0.1150) | (0.1310) | |||||

| Short-term Debt / Assets | −0.4940 | −0.4870 | ||||

| (0.3440) | (0.3260) | |||||

| Long-term Debt / Assets | ||||||

| (0.0729) | (0.0786) | |||||

| Momentum | ||||||

| (0.0153) | (0.0218) | |||||

| Analyst Following | 0.0911 | 0.1390 | ||||

| (0.0304) | (0.0325) | |||||

| Blockholder | −0.0128 | −0.0128 | ||||

| (0.0479) | (0.0527) | |||||

| Institutional Ownership | 0.0399 | 0.0104 | ||||

| (0.0485) | (0.0516) | |||||

| US Listing | 0.1070 | 0.0883 | ||||

| (0.0371) | (0.0411) | |||||

| High ES | 0.0004 | |||||

| (0.0387) | ||||||

| Board Size | ||||||

| (0.0038) | ||||||

| Board Independence | 0.0033 | |||||

| (0.0526) | ||||||

| Board Governance Score | −0.0881 | |||||

| (0.0640) | ||||||

| Observations | 710 | 558 | ||||

| Industry Fixed Effects | yes | yes | ||||

| Country Fixed Effects | yes | yes | ||||

| Adjusted R-Squared | 0.18 | 0.18 | ||||

In Panel A, we show the means of the covariates from column (3) of Table 2 of the treatment and control group as well as the respective differences before and after entropy balancing.8 We find that before balancing, firms with higher-quality IR indeed differ substantially from those with lower-quality IR. They are on average significantly larger in terms of firm size, have a higher return on equity, and have significantly lower historical stock volatility and a lower cash-to-assets ratio. Additionally, more analysts are following firms with better-quality IR, the percentage of shares held by blockholders is lower, and they are more likely listed on US exchanges as well. However, all of these differences vanish once the algorithm is implemented.

In Panel B, we report the results from regressions similar to those in columns (3) and (4) of Panel B of Table 2 using our weighted sample. The results are consistent with those found in the previous section and help us rule out that observable systematic differences between firms with higher-quality IR and those with lower-quality IR are driving stock performance during the crisis.

However, while the inclusion of industry and country-fixed effects and the use of entropy balancing helps us to condition out time-invariant unobservable systematic differences between firms in different industries and countries as well as observable systematic differences between firms with strong IR and those with weak IR, there may also be time-invariant unobservable firm characteristics as well as time-varying economy and industry traits affecting our results. To account for this as well, we estimate regressions similar to Ding et al. (2021), where the dependent variable is the firm’s weekly stock return over the entire year 2020 and where we interact each independent variable, including our measures for the firm’s level of IR, with the weekly growth in confirmed COVID-19 cases in the country. This setting has the advantage that it allows us to include firm, industry-time, and economy-time-fixed effects. As Ding et al. (2021) notes, “[w]ith these fixed effects, we condition out all time-varying and time-invariant economy traits, such as differences in legal and political systems, policy reactions to the crisis, institutions and cultural norms, demographic, geographic, and population density characteristics, and other cross-country traits, as well as all time-varying and time-invariant industry differences, such as differences in the intensity of required in-person contact with customers, suppliers, and co-workers, that might influence stock price reactions to the pandemic” (p. 803). We report the results from these regressions in Table 5 .

Table 5.

IR, weekly COVID-19 growth rates, and weekly returns over the crisis-period. This table presents the results from OLS regressions similar to Ding et al. (2021). Across both panels, the dependent variable is a firm’s weekly stock return for the year 2020. In Panel A, the main independent variable of interest is High IR, which equals one if the firm’s IR score is larger than the median IR score within the respective country, and zero otherwise. We interact High IR with the variable Weekly Growth, which is the weekly growth rate of confirmed COVID-19 cases in the respective country, calculated as ((1+confirmed cases in week (t)) / (1 + confirmed cases in week ())). In Panel B, the main indepedent variable of interest is (IR score), which is the natural logarithm of the raw IR score. Similar to Ding et al. (2021) we control for firm characteristics (in columns (2) to (5)) and economy characteristics (in column (3)) in terms of annual GDP growth rate, log(GDP), and %Population (age65), which is the fraction of people aged above 65 years in a country. In column (3), we also include several legal origin dummy variables, which equal one if the country’s legal origin is English, French, or German. Across all columns, except for column (5), we include industry-month and firm-fixed effects. In column (5), we include industry-week fixed effects and firm-fixed effects instead. In columns (4) and (5), we additionally include economy-week fixed effects. We report robust standard errors clustered by firm in parentheses, with , , denoting statistical significance at the , , and level.

| Panel A: | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent Variable: Weekly returns | |||||

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | |

| Weekly Growth | |||||

| (0.0017) | (0.0057) | (0.0673) | |||

| High IR Weekly Growth | 0.0034 | 0.0065 | 0.0054 | 0.0042 | 0.0041 |

| (0.0019) | (0.0020) | (0.0017) | (0.0014) | (0.0015) | |

| Size Weekly Growth | −0.0001 | −0.0001 | |||

| (0.0006) | (0.0006) | (0.0005) | (0.0005) | ||

| ROE Weekly Growth | 0.0073 | 0.0012 | 0.0073 | 0.0100 | |

| (0.0132) | (0.0113) | (0.0108) | (0.0108) | ||

| Tobin’s Q Weekly Growth | 0.0001 | 0.0011 | 0.0010 | 0.0011 | |

| (0.0007) | (0.0006) | (0.0005) | (0.0005) | ||

| Market-to-Book Weekly Growth | 0.0000 | 0.0001 | 0.0001 | 0.0001 | |

| (0.0002) | (0.0002) | (0.0002) | (0.0002) | ||

| Cash / Assets Weekly Growth | 0.0094 | −0.0052 | −0.0034 | −0.0017 | |

| (0.0090) | (0.0081) | (0.0069) | (0.0071) | ||

| Short-term Debt / Assets Weekly Growth | 0.0129 | −0.0174 | −0.0173 | −0.0167 | |

| (0.0228) | (0.0190) | (0.0169) | (0.0171) | ||

| Long-term Debt Weekly Growth | −0.0070 | ||||

| (0.0068) | (0.0060) | (0.0050) | (0.0050) | ||

| GDP Growth Weekly Growth | 0.0833 | ||||

| (0.0952) | |||||

| log(GDP) Weekly Growth | 0.0297 | ||||

| (0.0054) | |||||

| Population (age 65) Weekly Growth | 0.0040 | ||||

| (0.0007) | |||||

| Legor(English) Weekly Growth | 0.0265 | ||||

| (0.0044) | |||||

| Legor(French) Weekly Growth | 0.0371 | ||||

| (0.0041) | |||||

| Legor(German) Weekly Growth | 0.0041 | ||||

| (0.0039) | |||||

| Observations | 36,850 | 36,850 | 36,850 | 36,850 | 36,850 |

| Firm Fixed Effects | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes |

| Industry-Month Fixed Effects | yes | yes | yes | yes | no |

| Industry-Week Fixed Effects | no | no | no | no | yes |

| Economy-Week Fixed Effects | no | no | no | yes | yes |

| Adjusted R-Squared | 0.11 | 0.11 | 0.12 | 0.40 | 0.43 |

| Panel B: | |||||

| Dependent Variable: Weekly returns | |||||

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | |

| Weekly Growth | 0.0165 | ||||

| (0.0066) | (0.0117) | (0.0679) | |||

| (IR Score) Weekly Growth | 0.0041 | 0.0071 | 0.0085 | 0.0073 | 0.0073 |

| (0.0017) | (0.0019) | (0.0018) | (0.0017) | (0.0017) | |

| Size Weekly Growth | −0.0006 | −0.0007 | |||

| (0.0006) | (0.0006) | (0.0005) | (0.0005) | ||

| ROE Weekly Growth | 0.0102 | 0.0007 | 0.0082 | 0.0108 | |

| (0.0135) | (0.0114) | (0.0110) | (0.0110) | ||

| Tobin’s Q Weekly Growth | 0.0000 | 0.0011 | 0.0009 | 0.0010 | |

| (0.0007) | (0.0006) | (0.0005) | (0.0005) | ||

| Market-to-Book Weekly Growth | −0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0001 | 0.0001 | |

| (0.0002) | (0.0002) | (0.0002) | (0.0002) | ||

| Cash-to-Assets Weekly Growth | 0.0089 | −0.0052 | −0.0048 | −0.0032 | |

| (0.0089) | (0.0080) | (0.0069) | (0.0071) | ||

| Short-term Debt Weekly Growth | 0.0122 | −0.0152 | −0.0157 | −0.0152 | |

| (0.0234) | (0.0191) | (0.0170) | (0.0172) | ||

| Long-term Debt Weekly Growth | −0.0071 | ||||

| (0.0066) | (0.0057) | (0.0050) | (0.0050) | ||

| GDP Growth Weekly Growth | 0.0347 | ||||

| (0.0963) | |||||

| (GDP) Weekly Growth | 0.0283 | ||||

| (0.0055) | |||||

| %Population (age 65) Weekly Growth | 0.0046 | ||||

| (0.0007) | |||||

| Legor(English) Weekly Growth | 0.0346 | ||||

| (0.0048) | |||||

| Legor(French) Weekly Growth | 0.0399 | ||||

| (0.0043) | |||||

| Legor(German) Weekly Growth | 0.0100 | ||||

| (0.0042) | |||||

| Observations | 36,850 | 36,850 | 36,850 | 36,850 | 36,850 |

| Firm Fixed Effects | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes |

| Industry-Month Fixed Effects | yes | yes | yes | yes | no |

| Industry-Week Fixed Effects | no | no | no | no | yes |

| Economy-Week Fixed Effects | no | no | no | yes | yes |

| Adjusted R-Squared | 0.11 | 0.11 | 0.12 | 0.40 | 0.43 |

In Panel A, the main independent variable of interest is the interaction term between Weekly Growth and High IR. Column (1) shows the results from a regression where we only include this interaction term,Weekly Growth, as well as firm and industry-month-fixed effects. We find that the coefficient on Weekly Growth is negative and significant, whereas the coefficient on the interaction term is positive and significant. This suggests that while an increase in the growth of COVID-19 cases is associated with lower stock returns of firms, the effect is dampened for firms with better-quality IR. This finding persists when we add additional firm characteristics (column (2)), economy characteristics (column (3)), or when we include economy-week-fixed effects (columns (4) and (5)).

In Panel B, we repeat the analysis from Panel A, but we employ our raw IR scores instead of our dummy variable High IR. Overall, the results are very similar to those discussed earlier since we find that firms with better-quality IR appear to experience higher stock returns in reaction to an increase in an economy’s exposure to the pandemic.

4.3. The importance of IR during and after the crisis

To further test whether investors favored firms with better IR particularly during the crisis period, we also perform daily cross-sectional regressions with the same model specifications as in column (3) of Panel B (Table 2). This test allows us to study whether the importance of IR increased when the COVID-19 crisis unfolded. Similar to Albuquerque et al. (2020), we choose January 2, 2020 as our starting point and calculate abnormal returns for this particular trading day. From this point on, we gradually expand the window by one additional trading day, calculate the respective cumulative abnormal returns for the time window, and run the regression. Figure 4 displays the results. For better orientation, we show the evolution of the coefficients on our variable of interest High IR as well as on Cash / Assets and Long-term Debt / Assets.

Fig. 4.

Evolution of regression coefficients over the crisis-period. This figure shows the evolution of coefficients and the respective confidence intervals from daily cross-sectional regressions with the same model specifications as in column (3) of Panel B (Table 2). We report the daily coefficient loadings on the variables High IR, Cash / Assets, and Long-term Debt / Assets for the period from January 3, 2020 to March 27, 2020.

We find that the loading of the coefficients on High IR increases and that the coefficients become statistically significant when stock markets collapsed beginning in late-February. While the coefficients on High IR are almost zero and mostly statistically insignificant at the beginning of the year, the coefficient is largest () and highly statistically significant ( level) using the time window from January 2 to March 23, 2020. This provides support for our hypothesis stating that firms with better two-way communication performed significantly better during the COVID-19 crisis since they may have reduced uncertainty and information frictions among market participants. It is also noteworthy that we find the coefficient on Cash / Assets to increase as well, while the coefficient on Long-term Debt / Assets decreases. As already mentioned before, this is in line with the findings from Albuquerque et al. (2020), Ding et al. (2021), and Fahlenbrach et al. (2021).

Next, we perform difference-in-differences estimations similar to Lins et al. (2017) and Albuquerque et al. (2020) as an identification strategy to establish an even tighter link between the stock performance of firms with strong IR and the COVID-19 crisis. Specifically, we construct a panel of daily abnormal returns for all firms in our sample for the period from January 1 through October 6, 2020. Using this panel, we estimate the following regression:

| (4.2) |

where is the firm, is the trading day, and denotes the error term. We use High IR as our treatment variable and interact it with the variables and . The variable is a dummy variable equalling one for all dates between February 24 and March 23, 2020, and zero otherwise. As outlined in Ramelli and Wagner (2020), this is the period where stock markets fell dramatically. The variable is also a dummy variable, which equals one for all dates from March 24, 2020 onwards, and zero otherwise. Thus, this variable covers the period where stock markets were recovering. The terms and , respectively, denote firm-fixed effects and day-fixed effects. We report the results from these regressions in Table 6 where standard errors are clustered by firm and day. To ensure that the parallel trends assumption is not violated, we also perform the same formal test as in Albuquerque et al. (2020). Hence, we run a regression of daily abnormal returns on High IR for the period from January 1 to February 23, 2020. Although not reported for reasons of brevity, we can assure that there is no statistically significant relation between High IR and the daily abnormal returns.

Table 6.

IR and abnormal returns surrounding the crisis-period. This table presents the results from difference-in-differences regressions. The dependent variable is a firm’s daily abnormal return for the period from January 1, 2020 to October 6, 2020. High IR is our treatment variable and we interact it with the variables crisis and post crisis. The variable crisis is a dummy variable equalling one for all dates between February 24, 2020 and March 23, 2020, and zero otherwise. The variable post crisis is a dummy variable equalling one for all dates after March 24, 2020, and zero otherwise. In column (1) we do not include any fixed effects, while in column (2) we include firm and day-fixed effects. Thus, we omit the individual terms. All variables are described in detail in Table A.1 in the appendix. We report robust standard errors clustered by firm and day in parentheses, with , , denoting statistical significance at the , , and level.

| Dependent Variable: Abnormal returns | (1) | (2) |

|---|---|---|

| High IR crisis | 0.0040 | 0.0040 |

| (0.0012) | (0.0012) | |

| High IR post crisis | −0.0005 | −0.0005 |

| (0.0003) | (0.0003) | |

| High IR | 0.0004 | |

| (0.0003) | ||

| crisis | ||

| (0.0021) | ||

| post crisis | 0.0008 | |

| (0.0006) | ||

| Observations | 189,400 | 189,400 |

| Firm Fixed Effects | no | yes |

| Day Fixed Effects | no | yes |

| Adjusted R-Squared | 0.01 | 0.03 |

In column (1) of Table 6, we show the results from a regression where we include all interactions and individual effects but omit fixed effects. In column (2), we report the results from a regression where we include the interactions and firm and day-fixed effects; thus we omit the individual effects. Regardless of the specification, we find positive and statistically significant coefficients on the interaction between High IR and crisis, and negative but statistically insignificant coefficients on the interaction between High IR and post crisis. The positive coefficients indicate that firms with strong IR experienced on average 0.40 percentage points higher daily abnormal returns during the period where stock markets collapsed. Cumulating these daily gains over the entire crisis period yields an average abnormal return surplus of approximately 8.80 percentage points, which is comparable to the results from our baseline estimations. It may appear surprising that we do not find a statistically significant reversal in abnormal returns in the post-crisis period. Yet, this may be due to the fact that the level of uncertainty on financial markets was still high after the initial shock since a vaccine was not immediately available and governments were imposing severe restrictions.

4.4. Differentiating between public and private IR

After having shown that IR is generally valuable during the crisis, we next examine which functions of IR particularly drive our results. We follow Brochet et al. (2021) and decompose a firm’s IR score into a public and a private component. While the public component aims at capturing the impact of those IR activities primarily related to public events and disclosure quality on our IR score, the private component aims at capturing the impact of activities primarily related to private interactions between a firm and its investor base (e.g., meetings with senior management). In their analysis, Brochet et al. (2021) highlight that both functions of IR contribute significantly to better capital market outcomes. It is, however, questionable whether this finding persists during the COVID-19 crisis. This is because the COVID-19 crisis did not only cause significant uncertainty about a firm’s future cash flows but also posed additional challenges for public investor events due to the potential risk of infection. Furthermore, survey results published in an article in the IR magazine suggest that “... investors remain[ed] eager for continued access to company management teams, expressing a unanimous view that continuing to hold virtual one-on-one meetings with investors amid the pandemic was either important or very important” (IR Magazine, 2020). Hence, this might imply that investors put more emphasis on private IR activities during the crisis.

To investigate the relationship between the public and private components of IR and firms’ crisis returns, we use a two-stage regression approach. In the first stage, we run a regression of the natural logarithm of the IR score on three variables related to a firm’s public IR functions, namely Guidance, Conferences, and US Listing; and we additionally include industry and country-fixed effects. Similar to Brochet et al. (2021), we find all three variables to be positively and statistically significantly related to the IR score. We then use the fitted values from this first stage regression as the firms’ Public IR Score, while we use the residuals, i.e., the part that is not explained by a firm’s public IR activities, as the firms’ Private IR Score. Additionally, we construct the dummy variables Public IR and Private IR, which equal one if the respective score is larger than the sample median, and zero otherwise. In the second stage, we then run regressions similar to those in the previous sections replacing the variable High IR with the respective scores and dummy variables. The results from these regressions are presented in Tables 7 and 8 .

Table 7.

Public vs. private IR and crisis-period returns. This table presents the results from OLS regressions. The dependent variable is a firm’s cumulative abnormal return (based on market model estimations) for the period from February 3, 2020 to March 23, 2020, which is the collapse period as defined in Fahlenbrach et al. (2021). In column (1), the main independent variables of interest are a firm’s Public IR Score and the respective Private IR Score. To construct the public and private components of IR, we run a regression of the natural logarithm of the IR score on three variables related to a firm’s public IR functions, namely Guidance, Conferences, and US Listing. We employ the fitted values as firms’ Public IR Score and the residuals as firms’ Private IR Score. In column (2) we use the dummy variables Public IR and Private IR, which equal one if the respective score is larger than the sample median, and zero otherwise. Across all columns, we control for country-fixed effects and industry-fixed effects based on the Global Industry Classification Standard’s (GICS) 11 sectors and a variety of firm characteristics. All variables are described in detail in Table A.1 in the appendix. We report robust standard errors clustered by country in parentheses, with , , denoting statistical significance at the , , and level.

| Dependent Variable: Abnormal returns | ||

|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | |

| Public IR Score | 0.0487 | |

| (0.0924) | ||

| Private IR Score | 0.1512 | |

| (0.0217) | ||

| Public IR | −0.0095 | |

| (0.0286) | ||

| Private IR | 0.0905 | |

| (0.0113) | ||

| Size | 0.0080 | 0.0133 |

| (0.0141) | (0.0132) | |

| ROE | 0.3693 | 0.3450 |

| (0.2793) | (0.2934) | |

| Tobin’s Q | 0.0287 | 0.0285 |

| (0.0059) | (0.0060) | |

| Market-to-Book | −0.0020 | −0.0018 |

| (0.0016) | (0.0015) | |

| Historical Volatility | −0.1054 | −0.1008 |

| (0.1484) | (0.1440) | |

| Cash / Assets | 0.0592 | 0.0936 |

| (0.0770) | (0.0694) | |

| Short-term Debt | −0.1900 | −0.1869 |

| (0.1868) | (0.2012) | |

| Long-term Debt | ||

| (0.0641) | (0.0655) | |

| Momentum | ||

| (0.0105) | (0.0111) | |

| Analyst Following | 0.0179 | 0.0302 |

| (0.0281) | (0.0266) | |

| Blockholder | −0.0263 | −0.0326 |

| (0.0532) | (0.0535) | |

| Institutional Ownership | 0.0003 | 0.0075 |

| (0.0480) | (0.0456) | |

| US Listing | 0.1168 | 0.1333 |

| (0.0373) | (0.0267) | |

| Observations | 710 | 710 |

| Industry Fixed Effects | yes | yes |

| Country Fixed Effects | yes | yes |

| Adjusted R-Squared | 0.29 | 0.29 |

Table 8.

Public vs. private IR and abnormal returns surrounding the crisis-period. This table presents the results from difference-in-differences regressions. The dependent variable is a firm’s daily abnormal return for the period from January 1, 2020 to October 6, 2020. The main independent variables of interest are Public IR and Private IR. To construct the public and private components of IR, we run a regression of the natural logarithm of the IR score on three variables related to a firm’s public IR functions, namely Guidance, Conferences, and US Listing. We employ the fitted values as firms’ Public IR Score and the residuals as firms’ Private IR Score and construct the dummy variables Public IR and Private IR, which equal one if the respective score is larger than the sample median, and zero otherwise. We then use Public IR and Private IR as our treatment variables and we interact them with the variables crisis and post crisis. The variable crisis is a dummy variable equalling one for all dates between February 24, 2020 and March 23, 2020, and zero otherwise. The variable post crisis is a dummy variable equalling one for all dates after March 24, 2020, and zero otherwise. In column (1) we do not include any fixed effects, while in column (2) we include firm and day-fixed effects. Thus, we omit the individual terms. All variables are described in detail in Table A.1 in the appendix. We report robust standard errors clustered by firm and day in parentheses, with , , denoting statistical significance at the , , and level.

| Dependent Variable: Abnormal returns | ||

|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | |

| Public IR crisis | 0.0015 | 0.0015 |

| (0.0013) | (0.0013) | |

| Private IR crisis | 0.0032 | 0.0032 |

| (0.0009) | (0.0009) | |

| Public IR post crisis | −0.0005 | −0.0005 |

| (0.0003) | (0.0003) | |

| Private IR post crisis | −0.0005 | −0.0005 |

| (0.0003) | (0.0003) | |

| Public IR | 0.0001 | |

| (0.0003) | ||

| Private IR | 0.0007 | |

| (0.0003) | ||

| crisis | ||

| (0.0023) | ||

| post crisis | 0.0010 | |

| (0.0006) | ||

| Observations | 189,400 | 189,400 |

| Firm Fixed Effects | no | yes |

| Day Fixed Effects | no | yes |

| Adjusted R-Squared | 0.01 | 0.03 |

In Table 7, we show the results from our baseline regression.9 We employ the raw scores in column (1) and the dummy variables in column (2). In both columns, we find the coefficient on our variable proxying for a firm’s private IR functions to be positive and highly statistically significant; and we find the coefficient on the variables proxying for a firm’s public IR functions to be statistically insignificant. In terms of effect size, the coefficient on Private IR in column (2) indicates that those firms with strong private IR experienced 9.05 percentage points higher cumulative abnormal returns during the crisis period than those with weak private IR. This effect is almost similar in size compared to the one we observe using our dummy variable High IR.

In Table 8, we present the results from the difference-in-differences regressions replacing High IR with the respective dummy variables for the IR functions. Same as in the baseline regression, we find firms with better-quality private IR to perform significantly better during the crisis period. In both columns, the coefficients on the interaction between Private IR and crisis are positive and statistically significant, while the coefficients on the interaction between Public IR and crisis are positive but not statistically significant at conventional levels. Also, we cannot observe a sign of reversal in the post-crisis period.

Overall, the results in this section suggest that a firm’s private IR functions are the main driver of the valuation effects during the COVID-19 crisis. A reason for this result may be that firms with better-quality private IR were particularly able to alleviate investors’ uncertainty about a firm’s prospects (e.g., through the use of meetings with senior management). Further, considering that the COVID-19 crisis posed great challenges to a firm’s public IR activities, especially public investor events, it is not surprising that public IR activities are not associated with higher returns during the collapse period.

4.5. Enhancement of credibility or diversification of shareholder base

We next examine how a firm’s IR functions and particularly private IR functions have boosted its firm value during the crisis period. One potential explanation may be that (private) IR helps to enhance credibility with its (incumbent) institutional investors, who are the main targets of a firm’s IR activities. Another explanation may be that IR helps to diversify a firm’s shareholder base, which in fact could also reduce stock volatility.

To test the first explanation, we run several fractional generalized linear models (GLM)10 where we regress our variable % Staying Inst. Investors, i.e., the fraction of those incumbent institutional investors who stayed loyal to the firm during the crisis period, on our measures for a firm’s IR quality and a variety of control variables. If a firm’s IR quality helps to enhance credibility with its incumbent institutional investors, we can expect that a large proportion of them stayed invested in firms with better-quality IR over the crisis period. Table 9 reports our results.

Table 9.

IR and institutional investor loyalty over the crisis-period. This table shows the results from fractional GLM regressions. The dependent variable % Staying Inst. Investors is the fraction of those incumbent institutional investors who stayed loyal to the firm during the crisis period (i.e., the first quarter of 2020). In column (1), the main independent variable of interest is High IR, which equals one if the firm’s IR score is larger than the median IR score within the respective country. In column (2), the main independent variables of interest are a firm’s Public IR Score and the respective Private IR Score. To construct the public and private components of IR, we run a regression of the natural logarithm of the IR score on three variables related to a firm’s public IR functions, namely Guidance, Conferences, and US Listing. We employ the fitted values as firms’ Public IR Score and the residuals as firms’ Private IR Score. In column (3) we use the dummy variables Public IR and Private IR, which equal one if the respective score is larger than the sample median, and zero otherwise. We report the marginal effects (ME) of the respective coefficients next to each regression specification. Across all columns, we control for country-fixed effects and industry-fixed effects based on the Global Industry Classification Standard’s (GICS) 11 sectors and a variety of firm characteristics. All variables are described in detail in Table A.1 in the appendix. We report robust standard errors clustered by country in parentheses, with , , denoting statistical significance at the , , and level.

| Dependent Variable: % Staying Inst. Investors | (1) | ME | (2) | ME | (3) | ME |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| High IR | 0.1050 | 0.0042 | ||||

| (0.0415) | (0.0017) | |||||

| Public IR Score | ||||||

| (0.1820) | (0.0073) | |||||

| Private IR Score | 0.1390 | 0.0056 | ||||

| (0.0762) | (0.0031) | |||||

| Public IR | −0.0727 | −0.0029 | ||||

| (0.0912) | (0.0037) | |||||

| Private IR | 0.1130 | 0.0045 | ||||

| (0.0585) | (0.0023) | |||||

| Size | 0.0168 | 0.0009 | 0.0271 | 0.0011 | 0.0209 | 0.0008 |

| (0.0193) | (0.0008) | (0.0185) | (0.0007) | (0.0181) | (0.0007) | |

| ROE | −0.1650 | −0.0066 | −0.2780 | −0.0112 | −0.2370 | −0.0095 |

| (0.3350) | (0.0134) | (0.350) | (0.0140) | (0.3490) | (0.0140) | |

| Tobin’s Q | 0.0865 | 0.0035 | 0.0861 | 0.0035 | 0.0862 | 0.0035 |

| (0.0420) | (0.0017) | (0.0387) | (0.0016) | (0.0404) | (0.0016) | |

| Market-to-Book | −0.0119 | −0.0005 | −0.0124 | −0.0005 | −0.0123 | −0.0005 |

| (0.0134) | (0.0005) | (0.0127) | (0.0005) | (0.0132) | (0.0005) | |

| Historical Volatility | −0.5380 | −0.0216 | −0.5750 | −0.0231 | −0.5630 | −0.0226 |

| (0.4310) | (0.0173) | (0.4380) | (0.0176) | (0.4300) | (0.0173) | |

| Cash / Assets | 0.2650 | 0.0106 | 0.2190 | 0.0088 | 0.2850 | 0.0114 |

| (0.2510) | (0.0101) | (0.2440) | (0.0098) | (0.2550) | (0.0102) | |

| Short-term Debt / Assets | 0.1810 | 0.0073 | 0.2090 | 0.0084 | 0.1970 | 0.0079 |

| (0.6010) | (0.0241) | (0.5580) | (0.0224) | (0.6040) | (0.0243) | |

| Long-term Debt / Assets | −0.0305 | −0.0012 | −0.0854 | −0.0034 | −0.0460 | −0.0019 |

| (0.1450) | (0.0058) | (0.1510) | (0.0061) | (0.1360) | (0.0055) | |

| Momentum | 0.2040 | 0.0082 | 0.1990 | 0.0080 | 0.2050 | 0.0082 |

| (0.0448) | (0.0018) | (0.0483) | (0.0019) | (0.0460) | (0.0019) | |

| Analyst Following | 0.0466 | 0.0019 | 0.0904 | 0.0036 | 0.0659 | 0.0026 |

| (0.0499) | (0.0020) | (0.0520) | (0.0021) | (0.0489) | (0.0020) | |

| Blockholder | −0.0612 | −0.0025 | −0.0875 | −0.0035 | −0.0696 | −0.0028 |

| (0.1110) | (0.0045) | (0.1060) | (0.0043) | (0.1070) | (0.0043) | |

| Institutional Ownership | 0.2670 | 0.0107 | 0.2660 | 0.0107 | 0.2690 | 0.0108 |

| (0.0871) | (0.0035) | (0.0840) | (0.0034) | (0.0840) | (0.0034) | |

| US Listing | −0.1100 | −0.0044 | 0.0606 | 0.0024 | −0.0486 | −0.0020 |

| (0.1730) | (0.0069) | (0.1950) | (0.0078) | (0.1810) | (0.0073) | |

| Observations | 710 | 710 | 710 | 710 | 710 | 710 |

| Industry Fixed Effects | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes |

| Country Fixed Effects | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes |

| R-Squared | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 |