Abstract

The early secreted antigenic target 6-kDa protein (ESAT-6) and culture filtrate protein 10 (CFP-10) are promising antigens for reliable immunodiagnosis of tuberculosis. Both antigens are encoded by RD1, a genomic region present in all strains of Mycobacterium tuberculosis and M. bovis but lacking in all M. bovis bacillus Calmette-Guérin vaccine strains. Production and purification of recombinant antigens are laborious and costly, precluding rapid and large-scale testing. Aiming to develop alternative diagnostic reagents, we have investigated whether recombinant ESAT-6 (rESAT-6) and recombinant CFP-10 (rCFP-10) can be replaced with corresponding mixtures of overlapping peptides spanning the complete amino acid sequence of each antigen. Proliferation of M. tuberculosis-specific human T-cell lines in response to rESAT-6 and rCFP-10 and that in response to the corresponding peptide mixtures were almost completely correlated (r = 0.96, P < 0.0001 for ESAT-6; r = 0.98, P < 0.0001 for CFP-10). More importantly, the same was found when gamma interferon production by peripheral blood mononuclear cells in response to these stimuli was analyzed (r = 0.89, P < 0.0001 for ESAT-6; r = 0.89, P < 0.0001 for CFP-10). Whole protein antigens and the peptide mixtures resulted in identical sensitivity and specificity for detection of infection with M. tuberculosis. The peptides in each mixture contributing to the overall response varied between individuals with different HLA-DR types. Interestingly, responses to CFP-10 were significantly higher in the presence of HLA-DR15, which is the major subtype of DR2. These results show that mixtures of synthetic overlapping peptides have potency equivalent to that of whole ESAT-6 and CFP-10 for sensitive and specific detection of infection with M. tuberculosis, and peptides have the advantage of faster production at lower cost.

Tuberculosis (TB) accounts for several million deaths per year worldwide. The synergism between infection with the human immunodeficiency virus and Mycobacterium tuberculosis (4, 12), combined with the emergence of multidrug-resistant strains of M. tuberculosis in several parts of the world (11) have fueled fears of the spread of TB in the near future (5). Next to an improved vaccine, the development of a rapid and reliable diagnostic assay for early detection of TB is a high priority. The available tuberculin (purified protein derivative [PPD]) skin test has a high frequency of false-positive results after previous vaccination with M. bovis bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG) (15), and nowadays more than half of all newly detected cases of TB in The Netherlands and other industrialized countries occur among immigrants from regions where TB is highly endemic and BCG vaccination is routinely used. In addition, false-negative PPD skin test results occur in patients with advanced TB (15). Comparative genomics is a relatively recent field of research that has contributed importantly to the identification of M. tuberculosis-specific antigens. Subtractive DNA hybridization of pathogenic M. bovis and bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG) (18) and DNA microarray analysis of M. tuberculosis H37Rv and BCG (6) have led to the identification of several regions of difference, one of which was designated RD1 and was found to be present in all M. tuberculosis and pathogenic M. bovis strains but lacking in all BCG strains and most environmental mycobacteria. RD1 encodes the immunogenic proteins early secreted antigenic target 6-kDa protein (ESAT-6) and culture filtrate protein 10 (CFP-10) (14, 24). In recent studies, human T-cell responses to ESAT-6 (17, 19, 21, 25) or CFP-10 combined with ESAT-6 (3, 23, 26) were found to be sensitive and specific for detection of infection with M. tuberculosis. ESAT-6 and CFP-10 are therefore promising candidate antigens for inclusion in a novel immunodiagnostic assay. However, production of recombinant antigens and the purification that is required for use in T-cell assays are laborious and costly, precluding conduction of the large-scale clinical studies which are now required to assess the precise diagnostic potential of these antigens in clinical practice. Since T cells can recognize individual synthetic peptides, we hypothesized that a mixture of synthetic overlapping peptides might induce T-cell responses with potency comparable to that of the whole protein. In the present study, we compared T-cell responses to recombinant ESAT-6 (rESAT-6) and recombinant CFP-10 (rCFP-10) with those to mixtures of overlapping peptides spanning the complete amino acid sequence of each antigen, and we compared the sensitivity and specificity of those assays for detection of infection with M. tuberculosis. This study shows that T-cell responses to rESAT-6 and rCFP-10 and those to mixtures of synthetic overlapping peptides are highly correlated and result in identical sensitivity and specificity, indicating that peptides can be used for detection of TB.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study subjects.

This study included 77 individuals, including 43 TB patients, 10 of whom were sampled two or three times in the course of their treatment; 12 individuals with documented PPD skin test conversion after exposure to M. tuberculosis between 1 month and 30 years previously; 14 BCG-vaccinated persons with high occupational exposure to M. tuberculosis; and 8 PPD-negative, non-BCG-vaccinated control subjects. The clinical and demographic characteristics of some of these subjects are described elsewhere (3). All subjects gave permission for blood sampling after written information was provided, and the study protocol (P136/97) was approved by the Leiden University Medical Center Ethics Committee.

Mycobacterial antigens.

rESAT-6 (batch p432) was expressed in Escherichia coli as previously described (14, 24). rESAT-6 was purified by preparative sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, and residual endotoxin was depleted by passage through a lipopolysaccharide affinity column (Detoxi-Gel; Pierce). All antigen preparations were kept frozen in phosphate-buffered saline at −20°C until use. rCFP-10 (batches 98-2 and 99-1) was produced from E. coli as described in detail recently (7). The final concentrations of the antigens used in proliferation assays using T-cell lines were as follows: rESAT-6, 0.01, 0.1, and 1 μg/ml; rCFP-10, 0.01, 0.1, and 1 μg/ml. The antigen concentrations used for stimulation of peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) were as follows: rESAT-6, 1 and 10 μg/ml; rCFP-10, 0.5 and 5 μg/ml. The individual highest response per antigen was used for the analysis. M. tuberculosis H37Rv sonicate was generously provided by D. van Soolingen (National Institute of Public Health and Environment, Bilthoven, The Netherlands) and P. R. Klatser (Royal Tropical Institute, Amsterdam, The Netherlands). PPD RT23 was obtained from the Statens Serum Institute (Copenhagen, Denmark). The production of short-term culture filtrate (ST-CF) has been described elsewhere in detail (1). In brief, M. tuberculosis H37Rv (8 × 106 CFU/ml) was grown in modified Sauton's medium without Tween 80 on an orbital shaker for 7 days. The culture supernatants were filter sterilized and concentrated on an Amicon YM 3 membrane (Amicon, Danvers, Mass.).

Synthetic peptides.

Peptides 20 amino acids (aa) long, with a 10-aa overlap, were manufactured by standard solid-phase methods on an ABIMED peptide synthesizer (ABIMED, Langenfeld, Germany) as previously described (H. Gausepohl, M. Kraft, C. Boulin, and R. W. Frank, Proc. 11th Am. Peptide Symp., abstr. 105, p. 1003, 1990). Amino acid composition was verified by chromatography, and the purity of the peptides was checked by reversed-phase high-pressure liquid chromatography. The amino acid sequences of the peptides that were used in the present study are listed in Table 1. Peptides were dissolved at 2.5 mg/ml in phosphate-buffered saline–1% dimethyl sulfoxide. For stimulation of cell cultures, peptides were used as a mixture of nine overlapping peptides spanning the complete sequence of ESAT-6 or CFP-10 at final concentrations of 0.1 and 1 μg/ml per peptide (0.9 and 9 μg/ml in total). Individual peptides were used at 1 and 10 μg/ml. A peptide from the sequence of heat shock protein 60 of M. leprae (aa 418 to 427; sequence, LQAAPALDKL) was used as a control stimulus.

TABLE 1.

Amino acid sequences of synthetic overlapping peptides of ESAT-6 and CFP-10 used in this study

| Peptide (position) | Amino acid sequencea |

|---|---|

| ESAT-6 | |

| p1 (1–20) | MTEQQWNFAGIEAAASAIQG |

| p2 (11–30) | IEAAASAIQGNVTSIHSLLD |

| p3 (21–40) | NVTSIHSLLDEGKQSLTKLA |

| p4 (31–50) | EGKQSLTKLAAAWGGSGSEA |

| p5 (41–60) | AAWGGSGSEAYQGVQQKWDA |

| p6 (51–70) | YQGVQQKWDATATELNNALQ |

| p7 (61–80) | TATELNNALQNLARTISEAG |

| p8 (71–90) | NLARTISEAGQAMASTEGNV |

| p9 (76–95)b | ISEAGQAMASTEGNVTGMFA |

| CFP-10 | |

| p1 (1–20) | MAEMKTDAATLAQEAGNFER |

| p2 (11–30) | LAQEAGNFERISGDLKTQID |

| p3 (21–40) | ISGDLKTQIDQVESTAGSLQ |

| p4 (31–50) | QVESTAGSLQGQWRGAAGTA |

| p5 (41–60) | GQWRGAAGTAAQAAVVRFQE |

| p6 (51–70) | AQAAVVRFQEAANKQKQELD |

| p7 (61–80) | AANKQKQELDEISTNIRQAG |

| p8 (71–90) | EISTNIRQAGVQYSRADEEQ |

| p9 (81–100) | VQYSRADEEQQQALSSQMGF |

From the N terminus to the C terminus.

Peptide 9 of ESAT-6 overlaps peptide 8 by 15 aa.

T-cell lines.

T-cell lines were generated as previously described (20). Briefly, PBMC obtained from TB patients or control subjects were incubated at 1 to 2 million cells per well in 24-well plates (Nunc, Roskilde, Denmark) in the presence of M. tuberculosis H37Rv sonicate or ST-CF at 5 μg/ml for 6 days and then expanded with recombinant interleukin-2; this was followed by freezing of the T-cell lines and storage in liquid nitrogen. Only T-cell lines that were M. tuberculosis specific, i.e., responding to M. tuberculosis sonicate or PPD but not to tetanus toxoid or the control peptide, were used in the present study.

T-cell proliferation assay.

T cells (15 × 103/well) were incubated with irradiated autologous or HLA-matched PBMC (50 × 103/well) with or without antigen in a total volume of 200 μl/well in triplicate in 96-well flat-bottom microtiter plates in Iscove's modified Dulbecco's medium (Gibco) supplemented with 10% pooled human AB serum, penicillin at 40 U/ml, and streptomycin at 40 μg/ml at 37°C in humidified air containing 5% CO2. At day 3 of the assay 0.5 μCi of [3H]thymidine (NEN Life Science Products, Hoofddorp, The Netherlands) was added to each well for the final 16 h of incubation. Cells were harvested on glass fiber filters with a Skatron harvester (Pharmacia, Uppsala, Sweden), and incorporation of radiolabeled thymidine was measured with a betaplate counter (Wallac, Turku, Finland). Proliferation was expressed as a stimulation index (SI) calculated as the mean counts per minute of triplicates cultured in the presence of antigen divided by the mean counts per minute of triplicates cultured without antigen. Per T-cell line, the responses to recombinant antigens and the corresponding peptide mixtures were obtained simultaneously.

Lymphocyte stimulation assay.

PBMC were isolated from heparinized venous blood by Ficoll-Hypaque density gradient centrifugation. Cells were frozen in RPMI 1640 medium (Gibco, Life Technology, Paisley, Scotland) supplemented with glutamine at 0.04 mmol/ml, 20% fetal calf serum, and 10% dimethyl sulfoxide. At day 0 of the lymphocyte stimulation assay, PBMC (1.5 × 105/well) were incubated in 96-well round-bottom microtiter plates with or without antigen with culture medium and under growth conditions identical to those described for the T-cell lines. Each antigenic stimulus was performed in triplicate. Supernatants for the detection of gamma interferon (IFN-γ) were aspirated at day 6 (50 μl/well), and each triplicate set was pooled. Per individual, the responses to protein antigen and peptide mixtures were obtained in one or two experiments using PBMC obtained on the same date.

IFN-γ production.

IFN-γ concentrations in supernatants were measured with a standard enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) technique (Peter H. van der Meide, U-CyTech, Utrecht, The Netherlands). Optical densities at 450 nm were determined and converted to IFN-γ concentrations from standard curves using the software program Kineticalc (Bio-Tek Instruments, Winooski, Vt.). The detection limit of the assay was 20 pg of IFN-γ/ml.

HLA-DR typing.

Antigens suitable for inclusion in a diagnostic assay are permissively recognized in the context of most HLA types. To investigate whether T-cell responses to ESAT-6 and CFP-10 segregated with the HLA type, the patients were HLA-DRB1 typed by PCR amplification of DNA obtained from peripheral blood cells or phytohemagglutinin-stimulated blast cells with sequence-specific primers, identifying polymorphisms corresponding to the serologically defined series DR1 to DR18.

Statistical analysis.

The correlation of individual responses to different antigens was analyzed by Spearman's correlation. Receiver operator characteristic (ROC) curves were constructed to describe the relationship between sensitivity and specificity at various cutoff levels (2). The effect of HLA-DR type on antigen-specific responses was analyzed using the Mann-Whitney test. Statistical analyses were two sided, and P values of < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

T-cell responses to individual peptides of ESAT-6 and CFP-10 versus those to peptide mixtures.

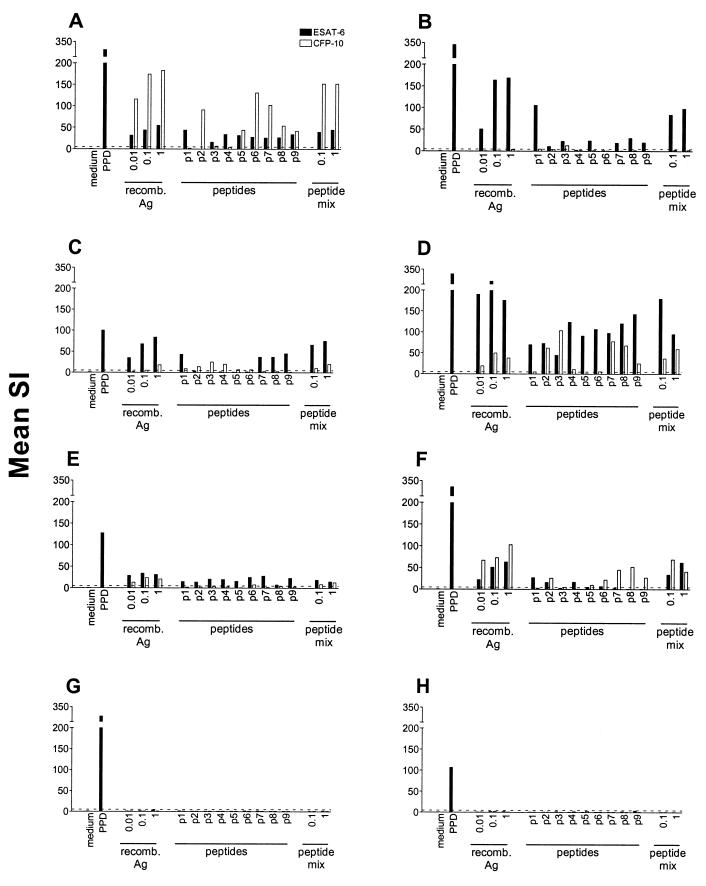

T-cell lines and PBMC of TB patients with various HLA-DR types were stimulated with rESAT6, rCFP-10, the individual peptides of ESAT-6 or CFP-10, and a mixture of all nine peptides of each antigen. As expected, T-cell lines that were unresponsive to recombinant antigen or the peptide mixture failed to respond to all of the individual peptides (Fig. 1G and 1H). T-cell lines that responded to rESAT-6 or rCFP-10 with an SI of >5, however, recognized various numbers of individual peptides, ranging from one to all nine of the peptides in a mixture (Fig. 1A through F). Peptides from both the N-terminal and C-terminal parts of the antigens could be efficiently recognized. Each peptide was recognized by at least one T-cell line. T-cell lines that were raised from the PBMC of TB patients with similar HLA-DR phenotypes tended to recognize the same sets of peptides (data not shown). Importantly, IFN-γ production by PBMC in response to individual peptides and peptide mixtures gave results similar to those obtained with T-cell lines, with various numbers of peptides being recognized by TB patients with different HLA-DR types (Table 2). For both T-cell lines and PBMC, the magnitude of the response to a peptide mixture correlated with the number of individual peptides of the corresponding antigen that was recognized but generally exceeded the response to each individual peptide. Based on the differential recognition of peptides and the finding that responses to peptide mixtures exceeded those to individual peptides, all further experiments were performed with mixtures including all nine peptides of ESAT-6 and CFP-10, respectively.

FIG. 1.

Proliferation of M. tuberculosis-specific T-cell lines with different HLA-DR phenotypes in response to PPD, rESAT-6, rCFP-10, individual peptides, and mixtures of overlapping peptides of these antigens. Antigen concentrations are in micrograms per milliliter. The HLA-DR types of the T-cell lines (A through H) were as follows: A, DR15,17; B, DR13,17; C, DR11; D, DR4,16; E, DR4,17; F, DR15; G, DR11,13; H, DR7,17. For test conditions, see Materials and Methods. Data are expressed as SIs calculated as mean counts per minute in the presence of antigen divided by the mean counts per minute without antigen. A dotted line indicates an SI of 5. p1 to p9, peptides 1 to 9; recomb. Ag, recombinant antigen.

TABLE 2.

Interindividual variation in IFN-γ production by PBMC in response to peptides of ESAT-6 and CFP-10

| Peptide(s)a | NCb | TB1 | TB2 | TB3 | TB4 | TB5 | TB6 | TB7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rESAT-6 | −c | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ |

| ESAT-6 pmix9 | − | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | +++ | +++ |

| p1 | − | ++ | + | ++ | ++ | +++ | ++ | |

| p2 | − | − | − | ++ | ++ | +++ | ++ | |

| p3 | − | + | − | ++ | ++ | ++ | + | |

| p4 | − | ++ | − | ++ | ++ | ++ | + | |

| p5 | − | NDd | + | − | ++ | + | ++ | ++ |

| p6 | − | − | − | ++ | + | +++ | +++ | |

| p7 | − | ++ | − | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | |

| p8 | − | − | − | + | + | +++ | +++ | |

| p9 | − | + | − | ++ | + | +++ | ++ | |

| rCFP-10 | − | +++ | +++ | +++ | ++ | ++ | +++ | +++ |

| CFP-10 pmix9 | − | ++ | ++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ |

| p1 | − | − | − | − | − | ++ | + | + |

| p2 | − | − | − | − | + | + | + | + |

| p3 | − | − | − | − | + | ++ | + | +++ |

| p4 | − | − | − | − | + | ++ | ++ | ++ |

| p5 | − | − | + | + | +++ | ++ | +++ | ++ |

| p6 | − | ++ | ++ | − | +++ | +++ | + | + |

| p7 | − | − | − | − | ++ | ++ | − | + |

| p8 | − | + | + | +++ | ++ | +++ | ++ | +++ |

| p9 | − | − | − | ++ | +++ | ++ | + | ++ |

pmix9 denotes the mixture of nine overlapping peptides. p1 to p9 denote peptides 1 to 9.

NC denotes a PPD skin test-negative, non-BCG-vaccinated control subject. TB1 through TB7 indicate TB patients with different HLA-DR phenotypes (TB1, DR4,17; TB2, DR1,15; TB3, DR4,7; TB4, DR13,15; TB5, DR15; TB6, DR11,13; TB7, DR4,13).

IFN-γ production is expressed semiquantitatively as follows: −, IFN-γ level of <100 pg/ml; +, level between 100 and 300 pg/ml; ++, level between 300 and 1,000 pg/ml; +++, level of >1,000 pg/ml.

ND, not determined.

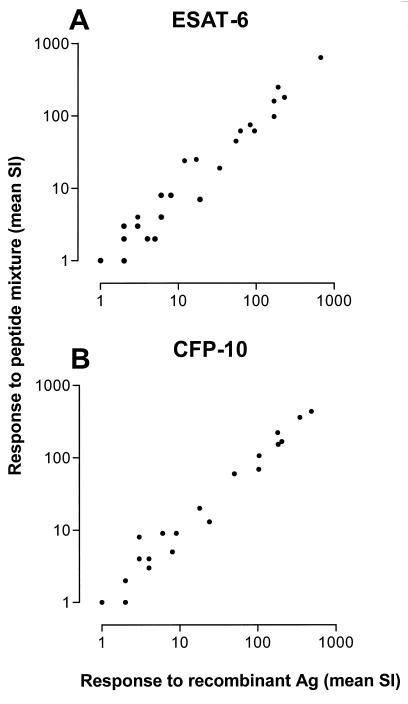

Proliferation of T-cell lines in response to rESAT-6, rCFP-10, or corresponding mixtures of synthetic overlapping peptides.

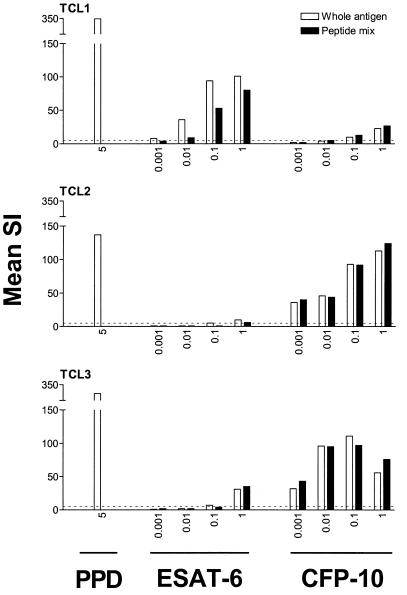

Next, we evaluated the proliferative responses of a larger number of M. tuberculosis-specific T-cell lines to whole recombinant antigens and corresponding peptide mixtures. This model system was chosen because it represents T-cell repertoires recognizing antigens of M. tuberculosis without the presence of T cells cross-reactive to nonmycobacterial antigens (20). Dose-response curves for rESAT-6, rCFP-10, and the corresponding peptide mixtures indicated that the optimal concentrations were similar for the recombinant antigens and the peptides in the mixture. A representative experiment is shown in Fig. 2. Proliferation of T-cell lines in response to rESAT-6 or rCFP-10 and the corresponding mixture of synthetic overlapping peptides correlated almost completely (Fig. 3). Highly significant correlations were found between the responses of T-cell lines to rESAT-6 and the peptide mixture (n = 25 T-cell lines; Spearman's r = 0.96; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.92 to 0.98; P < 0.0001) and between rCFP-10 and the corresponding peptide mixture (n = 21; r = 0.98; 95% CI, 0.94 to 0.99; P < 0.0001). Individual T-cell lines responded variably to rESAT-6 and rCFP-10, with high and low responses to one or both antigens being observed. Proliferation of T-cell lines in response to rCFP-10 correlated significantly with IFN-γ production in response to this antigen by PBMC from the same individual from which the T-cell line had been raised (data not shown; r = 0.79; 95% CI, 0.38 to 0.94; P = 0.002), indicating that the proportion and responsiveness of T cells recognizing rCFP-10 among PBMC was reflected in the responsiveness to this antigen of the descendant T-cell lines. Although a trend was observed, the correlation was not statistically significant for responses to rESAT-6 of T-cell lines and PBMC of the same donor (r = 0.49; P = 0.14).

FIG. 2.

Proliferation of M. tuberculosis-specific T-cell lines in response to rESAT-6, rCFP-10, and corresponding peptide mixtures was dose dependent and occurred at similar antigen concentrations of recombinant proteins or peptide mixtures. TCL1 through TCL3 indicate T-cell lines raised from PBMC obtained from different TB patients. A dotted line indicates an SI of 5. For test conditions, see Materials and Methods. Antigen concentrations are in micrograms per milliliter.

FIG. 3.

Proliferation of M. tuberculosis-specific T-cell lines in response to rESAT-6 (A) and rCFP-10 (B) compared to a mixture of synthetic overlapping (20-mer) peptides spanning the complete sequences of the antigens (Ag) correlated almost completely. Highly significant correlations were found between the responses of T-cell lines to rESAT-6 and the peptide mixture (n = 25 T-cell lines; Spearman's r = 0.96; 95% CI, 0.92 to 0.98; P < 0.0001) and between the responses to rCFP-10 and the corresponding peptide mixture (n = 21; r = 0.98; 95% CI, 0.94 to 0.99; P < 0.0001). For test conditions, see Materials and Methods.

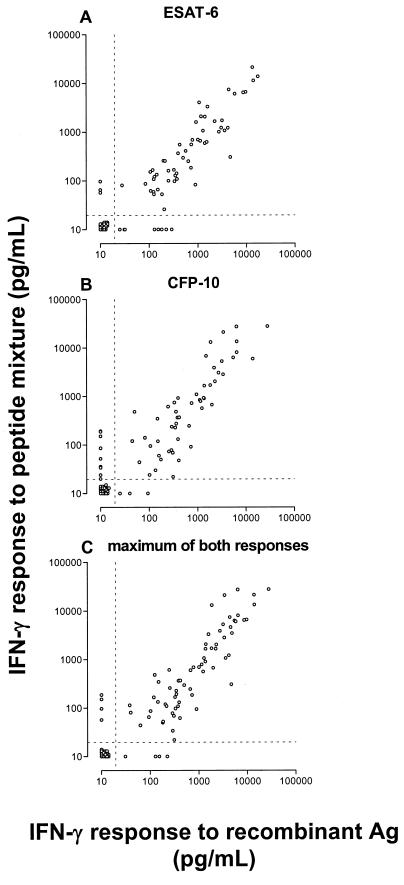

IFN-γ production by PMBC in response to rESAT-6, rCFP-10, or corresponding mixtures of synthetic overlapping peptides.

Finally, PBMC that were isolated from the peripheral blood of TB patients and nontuberculous control subjects were cocultured for 6 days with and without antigen and then the IFN-γ in supernatant culture fluid was measured. IFN-γ production was used as the readout of T-cell activation because proliferation in nonstimulated wells was variable and exceeded 1,500 cpm in a number of individuals, while IFN-γ production in nonstimulated wells was generally below the detection limit of the IFN-γ ELISA (20 pg/ml). Detectable IFN-γ levels that were found in unstimulated cultures in a minority of individuals were subtracted from the values of the corresponding stimulated cultures. All possible levels of response to rESAT-6 and rCFP-10, ranging from undetectable to extremely high responses, were represented in this study population, allowing evaluation of the correlation between responses to whole antigen and peptide mixtures over the complete range. As expected, PBMC responded optimally at antigen concentrations 5- to 10-fold higher than those that were optimal for T-cell lines (data not shown). As can be seen in Fig. 4A, IFN-γ levels in cultures stimulated with rESAT-6 and in those stimulated with the corresponding mixture of nine synthetic overlapping peptides were correlated highly significantly (n = 95; Spearman's r = 0.89; 95% CI, 0.84 to 0.93; P < 0.0001). Within the various groups of study subjects, the correlation was also significant (P < 0.0001 for TB patients, P = 0.0006 for PPD-converted subjects, P = 0.03 for BCG-vaccinated persons, and P < 0.0001 for PPD-negative, non-BCG-vaccinated individuals). A similarly high correlation existed between responses of PBMC to rCFP-10 and the CFP-10 peptide mixture (Fig. 4B; n = 96; Spearman's r = 0.89; 95% CI, 0.84 to 0.93; P < 0.0001). Here, on subgroup analysis, the correlation was significant for three groups (P < 0.0001 for TB patients, P = 0.0007 for PPD-converted subjects, and P < 0.0001 for PPD-negative, non-BCG-vaccinated individuals) but not for BCG-vaccinated individuals (r = 0.31; P = 0.3). The individual maxima of responses to both recombinant antigens and the maxima of responses to both peptide mixtures were correlated to the same extent as the results per antigen (Fig. 4C; n = 95; r = 0.88; 95% CI, 0.82 to 0.92; P < 0.0001).

FIG. 4.

Levels of IFN-γ production by PBMC in response to rESAT-6 (A) and rCFP-10 (B) and to mixtures of synthetic overlapping peptides (20-mers) spanning the complete amino acid sequences of the antigens were highly correlated (A: Spearman's r = 0.89; 95% CI, 0.84 to 0.93; P < 0.0001) (B: r = 0.89; 95% CI, 0.84 to 0.93; P < 0.0001). The individual maxima of both responses to recombinant antigens (Ag) and those of the responses to the peptide mixtures were correlated to the same great extent (C: r = 0.90; 95% CI, 0.86 to 0.94; P < 0.0001). For test conditions, see Materials and Methods. Dotted lines represent the detection limit of the IFN-γ ELISA (20 pg/ml).

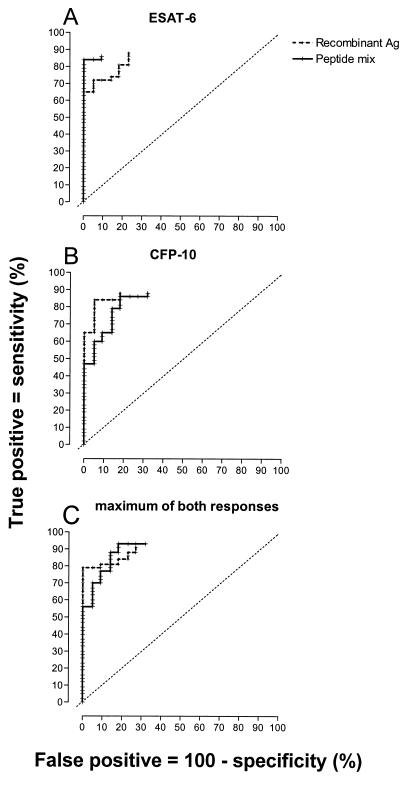

ROC curves were constructed, graphing the sensitivity and specificity of the T-cell response to RD1 proteins and peptide mixtures for detection of infection with M. tuberculosis for all possible cutoff levels (Fig. 5A and B). The sensitivity was based on the responses in TB patients, specificity was calculated from responses in healthy BCG-vaccinated and PPD-negative, non-BCG-vaccinated individuals taken together as a group without TB. The ROC curve constructed from the individual maximum responses to rESAT-6 and rCFP-10, and the maximum responses to both peptide mixtures resulted in the highest sensitivity, with some loss of specificity (Fig. 5C). From these data, it can be concluded that the sensitivity and specificity of the assay appear to be similar when recombinant proteins or peptide mixtures are used and that overall test performance is improved by combining the responses to both antigens compared with a test based on a single antigen.

FIG. 5.

ROC curves were constructed from the IFN-γ responses of PBMC to recombinant proteins and the peptide mixtures of ESAT-6 (A), CFP-10 (B), and the individual maxima of both responses (C). This was done by calculating the percentages of true positives (TB patients responding) and false positives (individuals without TB responding) at every possible cutoff value. The ROC curves end blind at a cutoff value equal to the detection limit of the ELISA (20 pg/ml) because in a number of subjects, IFN-γ production was below the detection limit. The slanted dotted lines represent ROC curves of a hypothetical test completely lacking diagnostic value. A perfect diagnostic test would run vertically along the y axis to the upper left corner and then horizontally to the right. The area under the ROC curve, extrapolated to the upper right corner, is directly related to the overall diagnostic value of the assay. Ag, antigen.

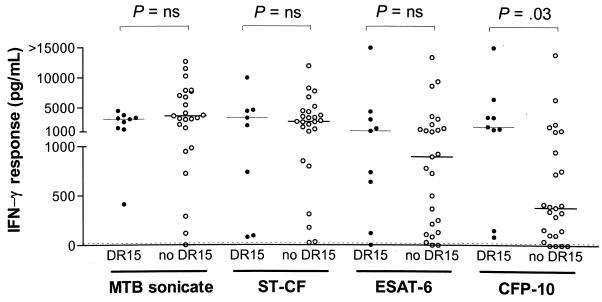

T-cell responses to rESAT-6, rCFP-10, and peptide mixtures in relation to HLA-DR type.

The known association of HLA-DR2 with TB (8, 22) prompted us to examine whether T-cell responses to rESAT-6 and rCFP-10 segregate according to HLA-DR type, which is quantitatively the most important class II antigen-presenting molecule (20), with a focus on HLA-DR2. All HLA-DR types were represented in the population of TB patients in this study, half of whom were immigrants from various regions of origin. T-cell responses to rESAT-6 and the complex antigens M. tuberculosis sonicate and ST-CF did not differ between patients with different HLA-DR types. The presence of HLA-DR15, which is the major subtype of DR2, was significantly associated with higher IFN-γ responses by PMBC to rCFP-10 (Fig. 6; P = 0.03). This association remained significant after adjustment for clinical and demographic variables, including the origin of the patient, in a multivariable logistic regression analysis. We did not exclude a role of linked HLA polymorphisms, however, as only HLA-DR alleles were typed in this study.

FIG. 6.

IFN-γ production by PBMC of TB patients in response to rCFP-10, but not in response to M. tuberculosis (MTB) sonicate, ST-CF, or rESAT-6, was significantly higher in the presence than in the absence of the HLA-DR15 phenotype. ns, not statistically significantly different.

DISCUSSION

This is the first study in which human T-cell responses to whole mycobacterial antigens were systematically and directly compared with those to mixtures of synthetic overlapping peptides of the same antigen. We observed that T-cell responses to rESAT-6 and rCFP-10 were highly correlated with those to mixtures of synthetic overlapping 20-mer peptides spanning the complete sequences of the corresponding antigens. The correlation was significant over the whole range of responses, at the levels of both IFN-γ production by PBMC and proliferation of T-cell lines. The inclusion of all overlapping peptides in the mixtures was based on our observation that different individuals recognized different sets of peptides and because the magnitude of responses to the peptide mixtures exceeded that of those to individual peptides. As peptides can be synthesized and purified in large quantities at considerably lower cost and with less effort than recombinant proteins, the practical implications of this study are significant.

Results of previous studies addressing T-cell responses to rESAT-6 (17, 19, 21, 25) and, more recently, rESAT-6 combined with rCFP-10 (3, 23, 26) indicated that these are promising antigens for specific immunodiagnosis of TB. Differences in sensitivity and specificity between these studies most likely resulted from nonuniformity of the antigen preparations and concentrations that were used, nonidentical in- and exclusion criteria, and different cutoff levels that were used to separate negative from positive test results. Moreover, a variable proportion of the TB patients had been treated for 6 months or longer and it has been shown that cellular immune responses to mycobacterial antigens can increase during treatment (25, 28–30). This is also exemplified by a negative PPD skin test result at the time of diagnosis converting to positive after a period of effective antituberculosis treatment. Therefore, well-designed prospective clinical studies including patients suspected of having, but not yet treated for, TB are now indicated for the assessment of the precise predictive value of T-cell responses to ESAT-6 and CFP-10 in daily clinical practice.

The above-mentioned practical advantages of peptides could significantly enlarge the scale at which future diagnostic studies can be performed. Corroboration of our data by others is needed before it can be concluded definitively that peptide mixtures can substitute for intact rESAT-6 and rCFP-10 in T-cell assays. Equivalent antigenic potency should be validated in every study by simultaneous testing of recombinant antigens and peptide mixtures in at least a portion of the experiments done.

Our data suggest that peptides generated from the intact protein by the intracellular antigen-processing machinery and those artificially designed as 20-mers may result in equivalent sensitivity and specificity for detection of infection with M. tuberculosis. For both ESAT-6 and CFP-10, we found a broad recognition pattern of individual peptides in the mixtures, indicating the presence of multiple epitopes within the protein. Previously, a similar broad recognition pattern was shown for responses of PBMC to overlapping peptides of ESAT-6 in Danish and Ethiopian TB patients (21). In contrast, Ulrichs et al. found low responses to only a limited number of, predominantly N-terminal, peptides of ESAT-6 in their population of TB patients, whose origins were not specified (25). In the latter study, PBMC of untreated patients with active TB were used and therefore immune responses may have been too depressed for recognition of single peptides. Together, these results suggest that rESAT-6 and rCFP-10 or corresponding peptide mixtures are useful diagnostic reagents, irrespective of a patient's origin. The interindividual variation in peptide recognition suggests that the use of a subset of peptides for immunodiagnosis might lead to failure to detect responses in some patients.

IFN-γ production by PBMC of TB patients in response to rCFP-10 was significantly higher in the presence of HLA-DR15, which is the major subtype of DR2. These DR15-positive patients differed from each other with regard to demographic characteristics and clinical manifestations of TB. It remains to be investigated whether high CFP-10-specific T-cell responses are clinically significant. Previously, DR2 has been associated with a more severe clinical course and a higher risk of recurrence of TB (22). Further studies are needed to assess whether antigen-specific responses relate to the response to treatment and the risk of recurrence of TB.

ESAT-6 and CFP-10 are relatively small proteins of 95 and 100 amino acids, respectively. For larger antigens, the increased number of synthetic peptides spanning the complete sequence may be impractical for the evaluation of peptide mixtures. Selection of potentially immunodominant peptides from the complete amino acid sequence based on HLA-binding motifs would be useful to identify potential epitopes, and restriction determination of different peptides could aid in selection of promiscuous HLA-presented immunodominant peptides. Such an approach has been used in two earlier studies. Jurcevic et al. reported that T-cell responses to a mixture of eight promiscuously recognized peptides of the M. tuberculosis 16-, 19-, and 38-kDa antigens could discriminate between patients with TB and PPD-negative control subjects (16). Recently, Vordermeier et al. demonstrated that T-cell responses in cattle to a mixture of permissively recognized peptides of ESAT-6, MPB64, and MPB83 discriminated between infection with M. bovis and sensitization by nonpathogenic mycobacteria or vaccination with BCG at a frequency similar to that of responses to a mixture of the whole proteins (27). Together with the data from our study, it can be concluded on the basis of these findings that synthetic peptides can carry the specificity required for reliable diagnosis of TB.

Peptide mixtures may have another purpose besides representing an alternative for recombinant or native purified whole proteins in diagnostic assays. The determination of the genomic nucleotide sequence of M. tuberculosis H37Rv (10) has given impetus to comparative genomics (6, 9, 13, 18) and cloning of interesting genes. In that respect, peptides could also be used to screen for the potential antigenicity of proteins encoded by as yet unexplored mycobacterial genes that are interesting on theoretical grounds but the gene product of which is not available yet or the purification of which poses a limiting step. We propose that T-cell responses to peptide libraries taken from the mycobacterial genome could help to select immunogenic proteins to be used for diagnostic or vaccine-related purposes.

In conclusion, T-cell responses to the M. tuberculosis-specific antigens ESAT-6 and CFP-10 appear to be highly correlated with those to the respective mixture of synthetic overlapping peptides at the level of both PBMC and M. tuberculosis-specific T-cell lines. In combination with the wide availability and relatively low cost of synthetic peptides, our results support the inclusion of peptide mixtures in future studies aimed at specific immunodiagnosis of TB.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by a grant from the Praeventiefonds (project 28-3021), by the Commission of the European Communities, by the Netherlands Leprosy Relief Foundation, and by the Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Science.

We are indebted to all of the patients and control subjects who participated for their cooperation, to Willemien E. Benckhuijsen and Jan-Wouter Drijfhout for synthesis of the peptides, and to Geziena M. T. Schreuder and her colleagues for HLA typing of the patients. Finally, we thank René R. P. de Vries for his continuous support and critical reading of the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Andersen P, Askgaard D, Ljungqvist L, Bennedsen J, Heron I. Proteins released from Mycobacterium tuberculosis during growth. Infect Immun. 1991;59:1905–1910. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.6.1905-1910.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anonymous. Statistical methods in epidemiology. In: Armitage P, Berry G, editors. Statistical methods in medical research. Oxford, England: Blackwell Scientific Publications; 1994. pp. 507–534. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arend, S. M., P. Andersen, K. E. Van Meijgaarden, R. L. V. Skjøt, Y. W. Subronto, J. T. van Dissel, and T. H. M. Ottenhoff. Sensitive and specific detection of active infection with Mycobacterium tuberculosis by human T cell responses to ESAT-6 and CFP-10. J. Infect. Dis., in press.

- 4.Barnes P F, Bloch A B, Davidson P T, Snider D E., Jr Tuberculosis in patients with human immunodeficiency virus infection. N Engl J Med. 1991;324:1644–1650. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199106063242307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beardsley T. Paradise lost? Microbes mount a comeback as drug resistance spreads. Sci Am. 1992;267:18–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Behr M A, Wilson M A, Gill W P, Salamon H, Schoolnik G K, Rane S, Small P M. Comparative genomics of BCG vaccines by whole-genome DNA microarray. Science. 1999;284:1520–1523. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5419.1520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Berthet F X, Rasmussen P B, Rosenkrands I, Andersen P, Gicquel B. A Mycobacterium tuberculosis operon encoding ESAT-6 and a novel low-molecular-mass culture filtrate protein (CPF-10) Microbiology. 1998;144:3195–3203. doi: 10.1099/00221287-144-11-3195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bothamley G H, Swanson Beck J, Schreuder G M T, D'Amaro J, De Vries R R P, Kardjito T, Ivanyi J. Association of tuberculosis and M. tuberculosis-specific antibody levels with HLA. J Infect Dis. 1989;159:549–555. doi: 10.1093/infdis/159.3.549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brosch R, Gordon S V, Billault A, Garnier T, Eiglmeier K, Soravito C, Barrell B G, Cole S T. Use of a Mycobacterium tuberculosis H37Rv bacterial artificial chromosome library for genome mapping, sequencing, and comparative genomics. Infect Immun. 1998;66:2221–2229. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.5.2221-2229.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cole S T, Brosch R, Parkhill J, Garnier T, Churcher C, Harris D, Gordon S V, Eiglmeier K, Gas S, Barry III C E, Tekaia F, Badcock K, Basham D, Brown D, Chillingworth T, Connor R, Davies R, Devlin K, Feltwell T, Gentles S, Hamlin N, Holroyd S, Hornsby T, Jagels K, Krogh A, McLean J, Moule S, Murphy L, Oliver K, Osborne J, Quail M A, Rajandream M-A, Rogers J, Rutter S, Seeger K, Skelton J, Squares R, Squares S, Sulston J E, Tayler K, Whitehead S, Barrell B G. Deciphering the biology of Mycobacterium tuberculosis from the complete genome sequence. Nature. 1998;393:537–544. doi: 10.1038/31159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dooley S W, Jarvis W R, Martone W J, Snider D E., Jr Multidrug-resistant tuberculosis. Ann Intern Med. 1992;117:257–258. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-117-3-257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Edlin B R, Tokars J I G M H, Crawford J T, Williams J, Sordillo E M, Ong K R, Kilburn J O, Dooley S W, Castro K G, Jarvis W R, Holmberg S D. An outbreak of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis among hospitalized patients with the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. N Engl J Med. 1992;326:1514–1521. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199206043262302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gordon S V, Brosch R, Billault A, Garnier T, Eiglmeier K, Cole S T. Identification of variable regions in the genomes of tubercle bacilli using bacterial artificial chromosome arrays. Mol Microbiol. 1999;32:643–655. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01383.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Harboe M, Oettinger T, Wiker H G, Rosenkrands I, Andersen P. Evidence for occurrence of the ESAT-6 protein in Mycobacterium tuberculosis and virulent Mycobacterium bovis and for its absence in Mycobacterium bovis BCG. Infect Immun. 1996;64:16–22. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.1.16-22.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Huebner R E, Schein M F, Bass J B., Jr The tuberculin skin test. Clin Infect Dis. 1993;17:968–975. doi: 10.1093/clinids/17.6.968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jurcevic S, Hills A, Pasvol G, Davidson R N, Ivanyi J, Wilkinson R J. T cell responses to a mixture of Mycobacterium tuberculosis peptides with complementary HLA-DR binding profiles. Clin Exp Immunol. 1996;105:416–421. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.1996.d01-791.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lein A D, von Reyn C F, Ravn P, Horsburgh C R, Jr, Alexander L N, Andersen P. Cellular immune responses to ESAT-6 discriminate between patients with pulmonary disease due to Mycobacterium avium complex and those with pulmonary disease due to Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 1999;6:606–609. doi: 10.1128/cdli.6.4.606-609.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mahairas G G, Sabo P J, Hickey M J, Singh D C, Stover C K. Molecular analysis of genetic differences between Mycobacterium bovis BCG and virulent M. bovis. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:1274–1282. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.5.1274-1282.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mustafa A S, Amoudy H A, Wiker H G, Abal A T, Ravn P, Oftung F, Andersen P. Comparison of antigen-specific T-cell responses of tuberculosis patients using complex or single antigens of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Scand J Immunol. 1998;48:535–543. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3083.1998.00419.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ottenhoff T H M, Elferink D G, Hermans J, De Vries R R P. HLA class II restriction repertoire of antigen-specific T cells. I. The main restriction determinants for antigen presentation are associated with HLA-D/DR and not with DP and DQ. Hum Immunol. 1985;13:105–116. doi: 10.1016/0198-8859(85)90017-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ravn P, Demissie A, Eguale T, Woodwosson H, Lein D, Amoudy H A, Mustafa A S, Jensen A K, Holm A, Rosenkrands I, Oftung F, Olobo J, von Reyn F, Andersen P. Human T cell responses to the ESAT-6 antigen from Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Infect Dis. 1999;179:637–645. doi: 10.1086/314640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Selvaraj P, Uma H, Reetha A M, Xavier T, Prabhakar R, Narayanan P R. Influence of HLA-DR2 phenotype on humoral & lymphocyte response to Mycobacterium tuberculosis culture filtrate antigens in pulmonary tuberculosis. Indian J Med Res. 1998;107:208–217. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Skjøt R L V, Oettinger T, Rosenkrands I, Ravn P, Brock I, Jacobsen S, Andersen P. Comparative evaluation of low-molecular-mass proteins from Mycobacterium tuberculosis identifies members of the ESAT-6 family as immunodominant T-cell antigens. Infect Immun. 2000;68:214–220. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.1.214-220.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sørensen A L, Nagai S, Houen G, Andersen P, Andersen Å B. Purification and characterization of a low-molecular-mass T-cell antigen secreted by Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Infect Immun. 1995;63:1710–1717. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.5.1710-1717.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ulrichs T, Munk M E, Mollenkopf H, Behr-Perst S, Colangeli R, Gennaro M L, Kaufmann S H E. Differential T cell responses to Mycobacterium tuberculosis ESAT6 in tuberculosis patients and healthy donors. Eur J Immunol. 1998;28:3949–3958. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4141(199812)28:12<3949::AID-IMMU3949>3.0.CO;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.van Pinxteren L A H, Ravn P, Agger E M, Pollock J M, Andersen P. Diagnosis of tuberculosis based on the two specific antigens ESAT-6 and CFP10. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 2000;7:155–160. doi: 10.1128/cdli.7.2.155-160.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vordermeier H M, Cockle P C, Whelan A, Rhodes S, Palmer N, Bakker D, Hewinson R G. Development of diagnostic reagents to differentiate between Mycobacterium bovis BCG vaccination and M. bovis infection in cattle. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 1999;6:675–682. doi: 10.1128/cdli.6.5.675-682.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wilkinson R J, Hasløv K, Rappuoli R, Giovannoni F, Narayanan P R, Desai C R, Vordermeier H M, Paulsen J, Pasvol G, Ivanyi J, Singh M. Evaluation of the recombinant 38-kilodalton antigen of Mycobacterium tuberculosis as a potential immunodiagnostic reagent. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:553–557. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.3.553-557.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wilkinson R J, Vordermeier H M, Wilkinson K A, Sjölund A, Moreno C, Pasvol G, Ivanyi J. Peptide-specific T cell responses to Mycobacterium tuberculosis: clinical spectrum, compartmentalization, and effect of chemotherapy. J Infect Dis. 1998;178:760–768. doi: 10.1086/515336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Young D B, Garbe T R. Heat shock proteins and antigens of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Infect Immun. 1998;59:3086–3093. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.9.3086-3093.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]