Abstract

This study makes a causal inference on the effects of anti-contagion and economic policies on small business by conducting a survey on Japanese small business managers’ expectations about the pandemic, policies, and firm performance. We first find the business suspension request decreased targeted firms’ sales by 10 percentage points on top of the baseline 9 percentage points decline due to COVID-19, even though the Japanese anti-contagion policy was in a form of the government’s request that is not legally enforceable. Second, using a discontinuity in the eligibility criteria, we find lump-sum and prompt subsidies improved firms’ prospects of survival by 19 percentage points. Third, the medium-run recovery of firms’ performance is expected to depend crucially on when infections would end, indicating that the anti-contagion policies could complement longer-run economic goals.

Keywords: COVID-19, Causal inference, Manager’s expectation, Business performance, Subsidy, Small business, Regression discontinuity design, Randomized controlled trial, Difference-in-difference, Pandemic, Infection, Anti-contagion policies, Lockdown, Survey

1. Introduction

The coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic, which started in early 2020, had already resulted in more than 100 million confirmed cases and two million deaths worldwide by the end of 2020. Large-scale social anti-contagion policies, such as the lockdown of cities, temporary closure of businesses, and prohibition of group gatherings, have been employed throughout the world to contain the spread of infection (Hsiang, Allen, Annan-Phan, Bell, Bolliger, Chong, Druckenmiller, Huang, Hultgren, Krasovich, Lau, Lee, Rolf, Tseng, Wu, 2020, Flaxman, Mishra, Gandy, Unwin, Mellan, Coupland, Whittaker, Zhu, Berah, Eaton, Monod, Ghani, Donnelly, Riley, Vollmer, Ferguson, Okell, Bhatt, 2020), through the reduction of people’s movements and contact (Zhang et al., 2020). These anti-contagion policies inevitably have been accompanied by a deep recession in the world economy (OECD, 2020). This short-run trade-off between health and wealth (Glover et al., 2020) polarized society into two: those who wish to control the spread of the virus and those who emphasize the economic down-side (Allcott et al., 2020). In the longer run, however, anti-contagion policies could benefit both health and the economy (Jordà et al., 2020). At the same time, governments have introduced several economic policies to soften the economic damage of anti-contagion policies, such as massive injections of money into lending markets and the provision of direct subsidies to households and firms. To make the correct decisions under crisis, governments need to understand the short-run economic and epidemiological trade-off as well as the potential long-run benefits of anti-contagion and economic policies.

In this study, we perform a causal inference on the short-run effects of anti-contagion policies on the economy, the impacts of subsidies to firms to ease the economic damage, as well as the potential medium-run economic benefits of the anti-contagion policies. This study focuses on small businesses, which are most vulnerable to the economic crisis. We study this issue in the context of Japan, where the number of new infections surged from March to April 2020, followed by the declaration of emergency state, which led to the local governments’ request for firms to suspend business temporarily and for individuals to stay at home. At the same time, the Japanese government introduced a series of new subsidy schemes to rescue small businesses. The Japanese case is unique in that the attempt to contain infections is closely tied to a longer-term economic goal, namely, the possibility of hosting the Tokyo Olympic Games. Thus, Japan’s short-run stringent anti-contagion policies could lead to a longer-run economic goal, thereby providing an ideal case for evaluating the short-run tension between epidemiological and economic goals as well as the longer-run complementarity between these two goals.

First, we investigate how the emergency declaration and the business suspension request hurt the performance of small businesses. For identification of the causal effects, we use two alternative strategies: (1) using the variation in local governments’ suspension requests across areas and industries over time and (2) randomizing the survey dates to be either just before or after the partial lifting of the emergency declaration to examine the impacts of this information on expected performance. Second, we study whether the subsidy schemes are expected to help small businesses to survive and whether they changed their on-going decisions, such as those on investment and employment. We exploit a discontinuity in eligibility cutoff of each subsidy scheme to estimate the impacts using the regression discontinuity design. Finally, we quantify the medium-run economic impacts of successfully controlling SARS-Cov-2 infection, particularly, how much business performance would improve if the infections were contained quickly and if the situation could stabilize enough for Japan to host the Tokyo Olympics in 2021. In doing so, we use the variation in managers’ beliefs about the timing of infection containment and quarterly sales in a difference-in-difference framework. As such, we contribute to the policy debate by uncovering part of the short-run and the medium-run effects of the Japanese version of anti-contagion and economic policies to tackle the COVID-19 crisis.

2. Data

We address these questions by conducting a survey amid the COVID-19 crisis, after the nationwide emergency had been declared, on the economic performance of small businesses and managers’ expectations about the pandemic, policies, and their firms’ future performance. We conducted the online survey in May 2020. The sampling frame consists of 28,169 individuals who were registered as top managers, the self-employed, or freelancers at one of the largest market research agencies in Japan. Among them, we target to managers of small business with less than 20 employees at the end of 2019.

The survey asked questions about the firm’s business, including the realized and expected sales growth compared to the previous year, realized and expected employment and investment, and types of measures adopted to deal with the COVID-19 crisis. It also asked about the firm’s expectations of COVID-19-related events: when the Japanese government’s emergency declaration, which had started on April 7, would be lifted in the whole country (asking for the most likely date, the earliest date, and the latest date); when the COVID-19 outbreak in Japan would be contained, that is, when the number of daily new infections would drop to zero for the first time in Japan; when mass vaccination against the virus would become available in Japan, and how likely it would be that the Tokyo Olympics would be held in 2021. The survey also asked firms whether they expected to receive the subsides offered by the central and local governments. In the end, we collected answers from 12,364 respondents. Through data validation checks, we dropped respondents who gave inconsistent or unrealistic answers or were not top-managers of small businesses, the target group for our analysis, at the time of the survey. We focused on the remaining 6,135 small business managers. See Appendix A.1 for more detail about data cleaning and sample selection

As our sample is not necessarily a representative of small business in Japan, the observations are weighted to match the number of small businesses in the Economic Census, which is conducted by the National Statistics Bureau, by 12 categories of employment size and sectors (see the Appendix A.2 for details about the weights). In the following, we report the results using the sample weighted by the Economic Census.

As shown in Table 1 , the average number of employees excluding top managers him/herself was 3.2. Firms that have no employee (excluding the managers themselves) at the end of 2019 comprised 24%, and those with 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5–19 employees constituted 22%, 13%, 9%, 7%, and 26%, respectively. B-to-C service, B-to-B service, and non-service industries consisted of 52%, 21%, and 27%, respectively. Average age of managers was 55.7, and male managers made up 89% of our sample. Year-on-year sales growth in January, 2020 was +0.55%, while in February, March, and April, they were -2.37%, -9.79%, and -17.57%, respectively. The expected year-on-year sales growth in Q1 (January-March) 2020 was -3.87%, followed by -19.01%, -11.99%, -7.99% in the Q2 (April–June), Q3 (July–September), and Q4 (October–December). 30% and 5% of managers said they would invest and disinvest in 1Q, 2020, respectively. The average probability of business continuity by the end of 2020 was 82%. 37%, 18%, and 18% of managers expected to receive the business continuation subsidy, the short-time work compensation, and the business suspension subsidy, respectively. The average probability that the Tokyo Olympics will be held during 2021 was 41%.

Table 1.

Summary statistics.

| mean | sd | min | max | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of employees | 3.23 | 3.79 | 0 | 28 |

| Number of employees: 0 | 0.24 | 0.43 | 0 | 1 |

| Number of employees: 1 | 0.22 | 0.41 | 0 | 1 |

| Number of employees: 2 | 0.13 | 0.33 | 0 | 1 |

| Number of employees: 3 | 0.09 | 0.29 | 0 | 1 |

| Number of employees: 4 | 0.07 | 0.25 | 0 | 1 |

| Number of employees: 5-19 | 0.26 | 0.44 | 0 | 1 |

| Industry: Business to Consumer service | 0.52 | 0.50 | 0 | 1 |

| Industry: Business to Business service | 0.21 | 0.41 | 0 | 1 |

| Industry: Non-service | 0.27 | 0.44 | 0 | 1 |

| Average age | 55.68 | 9.64 | 21 | 89 |

| Manager age: 20s | 0.00 | 0.07 | 0 | 1 |

| Manager age: 30s | 0.04 | 0.21 | 0 | 1 |

| Manager age: 40s | 0.21 | 0.41 | 0 | 1 |

| Manager age: 50s | 0.40 | 0.49 | 0 | 1 |

| Manager age: 60s | 0.26 | 0.44 | 0 | 1 |

| Manager age: 70s | 0.08 | 0.27 | 0 | 1 |

| male | 0.89 | 0.31 | 0 | 1 |

| realized sales growth in Jan 2020 compared to the last year | 0.55 | 22.95 | -100 | 200 |

| realized sales growth in Feb 2020 compared to the last year | -2.37 | 26.80 | -100 | 180 |

| realized sales growth in March 2020 compared to the last year | -9.79 | 37.08 | -100 | 160 |

| realized sales growth in April 2020 compared to the last year | -17.57 | 46.64 | -100 | 160 |

| realized sales growth in 1Q 2020 compared to the last year | -3.87 | 24.19 | -100 | 127 |

| expected sales growth in 2Q 2020 compared to the last year | -19.01 | 46.58 | -100 | 120 |

| expected sales growth in 3Q 2020 compared to the last year | -11.99 | 42.10 | -100 | 180 |

| expected sales growth in 4Q 2020 compared to the last year | -7.99 | 41.37 | -100 | 180 |

| realized investment in Q1 is positive | 0.30 | 0.46 | 0 | 1 |

| realized disinvestment in Q1 is positive | 0.05 | 0.23 | 0 | 1 |

| expected investment in Q2 is positive | 0.27 | 0.45 | 0 | 1 |

| expected disinvestment in Q2 is positive | 0.07 | 0.25 | 0 | 1 |

| probability of business survival | 82.41 | 24.50 | 1 | 100 |

| probability of receiving the continuation subsidy | 37.07 | 41.66 | 0 | 100 |

| probability of receiving the short-time work compensation | 17.99 | 32.53 | 0 | 100 |

| probability of receiving the business suspention subsidy | 18.12 | 32.91 | 0 | 100 |

| probability of hosting olympic in 2020-2021 | 41.26 | 29.80 | 0 | 100 |

| Observations | 6108 |

Note: The observations are weighted to match the number of firms in the Economic Census.

To capture the effects of the announcement on the partial lifting of the emergency declaration, which was expected when we designed the survey questionnaire, we randomly divided the sampling frame into two groups and sent the questionnaire on different dates. We sent out the questionnaires just before the partial lifting of the emergency declaration (May 8) and just after the partial lifting (May 15). They were sent at almost the same time of the two date, and closed the collection when the sample size reached 6,000 in each survey. The survey period was similar across groups: the survey was closed at midnight on May 9 and the early morning on May 17, respectively. We also demonstrate in the Appendix A.3 that basic characteristics of the firms are balanced across the groups.

In addition, we gathered information on local governments’ websites and the media to identify the industries that for which local governments requested business suspensions. The date, duration, and target facilities of the business suspension requests as well as the amount of suspension subsidy provided by local governments differ by prefectures. When an industry in a prefecture had at least one facility that was requested to be suspended, we regard the industry as being requested for suspension in the prefecture.

3. Causal impacts of anti-contagion and economic policies

3.1. How did the emergency declaration and business suspension requests affect businesses?

Our evidence based on the Difference-in-Difference estimation shows that the emergency declaration and the requests to suspend business lowered realized and expected firm sales in the short run while it reduced the number of new infections.

In Japan, on April 7, the government declared the state of emergency until May 6 in 7 prefectures (Tokyo, Kanagawa, Saitama, Chiba, Osaka, Hyogo, and Fukuoka). Under the emergency state, local municipalities requested business suspension at targeted industries and called for staying at home to citizens. It is noteworthy that these policies only took the form of “requests” that were not legally enforced, implying that the Japanese policies were milder than countries which implemented lock-down of cities. On April 16, the government expanded coverage of the emergency declaration to all prefectures in Japan. On May 4, the government extended the emergency declaration to May 31, indicating that it could be lifted earlier depending on the situations. On May 13, the government indicated that the emergency declaration in 39 among 47 prefectures was expected to be lifted, and this decision was formalized on May 14. At the same time, the government announced guidelines for lifting the emergency declaration for the remaining areas, specified based on the number of new infections, tightness of medical capacity, improvement of preparedness of testing conditions. The declaration was lifted on May 25 in all remaining areas. See the Appendix A.4 for more details.

Using the variation in business suspension requests across industries and prefectures, we examine how much of the sales decline from March to April is the direct effect of the business suspension request and the indirect effect through the spontaneous change in people’s behaviors. We restrict the samples to the business-to-consumer (B-to-C) service industries in this chapter, because the business suspension requests were limited to these industries.

Consider the following model:

| (1) |

where “(Sales)” is the percentage-point change in year-to-year sales from March to April of firm in industry located in prefecture ; and “(Suspension request)” is an indicator that takes a value of 1 if industry was subject to a business suspension request in April in prefecture , and 0 otherwise; it captures the direct policy effect. “(Infection risk)” captures the nature of infection risk of industry , defined by the decline of people visits from February to March in the corresponding industry in the U.S (Benzell et al., 2020). The higher the decline of visits, the higher the increases in the infection risk measure. Because this measure reflects the changes in the corresponding industry in the U.S., it captures the universal riskiness feature of the industry. “” is the change in the total number of new infections in prefecture from March to April, by which we control for the perceived infection risks in the prefecture.

Table 2 shows the regression results. We find that firm sales growth, defined as sales relative to the same month in the previous year, dropped by 9 percentage points from March to April regardless of business suspension status. Baseline result in the first column shows that the sales of firms that were subject to the business suspension requests additionally declined by 9.8 percentage points. This result is robust to controlling for prefecture fixed effects and the firm’s sales growth change from February to March 2020 (as shown in the second and third columns).

Table 2.

Effects of the suspension requests on sales change from March to April.

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| VARIABLES | Sales change | Sales change | Sales change | Sales change |

| Suspension request | 9.84*** | 10.06*** | 9.99*** | 9.70*** |

| (1.87) | (1.94) | (1.93) | (2.04) | |

| Infection risk | 0.59 | 0.58 | 0.63 | 1.22 |

| (1.00) | (1.02) | (1.01) | (1.01) | |

| Sales change Feb-to-Mar | 0.04* | 0.04 | ||

| (0.02) | (0.02) | |||

| Education Suspension request | 9.36 | |||

| (5.83) | ||||

| Travel & Hotel Suspension request | 4.24 | |||

| (24.24) | ||||

| Education | 0.99 | |||

| (4.82) | ||||

| Travel & Hotel | 15.45 | |||

| (22.93) | ||||

| New infection change Mar-to-Apr | 2.91 | |||

| (2.33) | ||||

| Observations | 3,230 | 3,230 | 3,230 | 3,230 |

| Pref FE | NO | YES | YES | YES |

| Mean (Suspension request) | 17.79 | 17.79 | 17.79 | 17.79 |

| Mean (No suspension request) | 9.082 | 9.082 | 9.082 | 9.082 |

Notes: This table uses the sample of firms in B-to-C service industries. ”Sales growth change in March to April” is the change in monthly sales growth (relative to the same month in the last year) from March to April, measured in percentage points. “Suspension request” takes 1 if business suspension was requested of the firm’s industry in April. The infection risk measure is from Benzell et al. (2020). “New infection change Mar-to-Apr” is the change in the number of infection cases per 10,000 population in the prefecture from March to April. The second column controls for the prefecture fixed effects. The third column additionally controls for the sales change from February to March, when the infection cases were increasing but business suspension was not requested, to take into account the firm’s sensitivity to the pandemic. “Education” is a dummy for education-support industry, which reportedly used online teaching to avoid business suspension. “Travel & Hotel” is a dummy variable for travel and hotel industries. Aside from education, travel, and hotel industries, business suspension was requested to restaurants (including bars) and entertainment industries in some prefectures. Standard errors clustered at the prefecture level are in parentheses. The observations are weighted to match the number of firms in the Economic Census. for , for , and for .

We next examine the effects of business suspension requests by industries in the fourth column. The result indicates that the effect of business suspension request for restaurants and bars is not statistically significantly different from those for education service and travel and hotel industries, although the size of the coefficients for the latter are smaller.1 It is noteworthy that the coefficient on travel and hotel industries (the term not interacted with the suspension request dummy) is negative and large (-15.7), implying that the sales have substantially declined in these industries even without the business suspension requests.

In Table 3 , we explore heterogeneity of the effects of business suspension requests across firm types. First, while the effects of business suspension requests are not significantly different between firms with and without an employee, it is small for freelancers, as shown in the first and second columns. Second, the effects of business suspension requests are similar between firms in prefectures where the emergency declaration started earlier in April 6 and those in prefectures where the declaration started later in April 16. Lastly, firms may conform more to the business suspension request if offered a suspension subsidy. Then, the sales should drop more with a suspension subsidy. However, the result in the fourth column does not confirm such an effect.

Table 3.

Effects of the suspension requests on sales change from March to April: Heterogeneity by firm type.

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| VARIABLES | Sales change | Sales change | Sales change | Sales change |

| Suspension request | 10.21*** | 13.78** | 10.20*** | 10.20*** |

| (2.01) | (5.86) | (3.16) | (3.16) | |

| Infection risk | 0.62 | 0.35 | 0.63 | 0.63 |

| (1.02) | (1.01) | (1.00) | (1.00) | |

| Sales change Feb-to-Mar | 0.04* | 0.04* | 0.04* | 0.04* |

| (0.02) | (0.02) | (0.02) | (0.02) | |

| No employee Suspension request | 1.01 | |||

| (2.92) | ||||

| No employee | 0.78 | |||

| (0.94) | ||||

| Self-employed Suspension request | 3.79 | |||

| (7.25) | ||||

| Freelance Suspension request | 13.51* | |||

| (7.06) | ||||

| Self-employed | 2.10 | |||

| (1.38) | ||||

| Freelance | 3.44 | |||

| (2.10) | ||||

| Early emergency state Suspension request | 0.45 | |||

| (3.43) | ||||

| Suspension subsidy Suspension request | 0.45 | |||

| (3.43) | ||||

| Observations | 3230 | 3230 | 3230 | 3230 |

| Pref FE | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Mean (Suspension request) | 17.79 | 17.79 | 17.79 | 17.79 |

| Mean (No suspension request) | 9.082 | 9.082 | 9.082 | 9.082 |

Notes: This table uses the sample of firms in B-to-C service industries. ”Sales growth change in March to April” is the change in monthly sales growth (relative to the same month in the last year) from March to April, measured in percentage points. “Suspension request” takes 1 if business suspension was requested of the firm’s industry in April. The infection risk measure is from Benzell et al. (2020). All equations control for the prefecture fixed effects and the sales change from February to March, when the infection cases were increasing but business suspension was not requested, to take into account the firm’s sensitivity to the pandemic. Standard errors clustered at the prefecture level are in parentheses. The observations are weighted to match the number of firms in the Economic Census. for , for , and for .

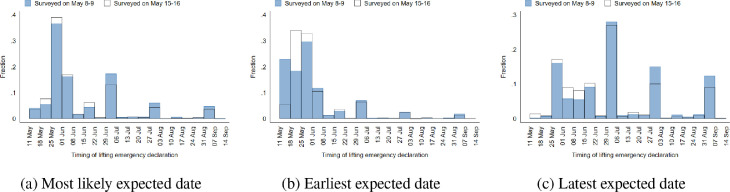

Next, to identify more strict causal effects of the state of emergency, we randomly assign the timing of the survey to the firms, and find that firms’ expectations significantly changed over just 1 week, from May 8 to 15, during which the emergency declaration was partially lifted in 39 prefectures and the government indicated clear guidelines for lifting the emergency in the remaining areas. Specifically, firms in the survey sent on May 15 expected the nationwide emergency declaration to end on average 4–5 days sooner than did firms in the survey sent on May 8. In addition, subjective uncertainty about the timing of the nationwide ending of the emergency declaration, measured by the difference between the earliest and the latest expected dates of ending, was significantly reduced for firms surveyed on the later date. These results are provided in Fig. 2 and Table 4 .

Fig. 2.

Expectations about when the emergency declaration would be lifted in all prefectures by survey week

Table 4.

Expected duration of the emergency declaration and COVID-19 by survey week.

| (a) B-to-C service industries | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | |

| Most-likely | Shortest | Longest | Most-likely | |||||

| expected duration of | expected duration of | expected duration of | expected duration of | |||||

| emergency declaration | emergency declaration | emergency declaration | COVID-19 in Japan | |||||

| Later group | 5.34*** | 0.34 | 11.29*** | 0.12 | ||||

| (1.80) | (1.17) | (2.74) | (0.38) | |||||

| Later group Suspension request | 4.98 | 0.44 | 9.32 | 0.03 | ||||

| (3.45) | (2.18) | (5.97) | (0.83) | |||||

| Later group No suspension request | 5.40*** | 0.54 | 11.78*** | 0.14 | ||||

| (2.08) | (1.36) | (3.08) | (0.43) | |||||

| Suspension request | 4.55 | 2.21 | 6.39 | 0.27 | ||||

| (2.77) | (1.86) | (4.63) | (0.65) | |||||

| Constant | 47.43*** | 48.34*** | 26.83*** | 27.27*** | 87.34*** | 88.62*** | 10.03*** | 10.08*** |

| (1.28) | (1.49) | (0.88) | (1.03) | (1.87) | (2.09) | (0.26) | (0.30) | |

| Observations | 3209 | 3209 | 3098 | 3098 | 3110 | 3110 | 3223 | 3223 |

| (b) Other industries (B-to-B service and non-service industries) | ||||||||

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |||||

| Most-likely | Shortest | Longest | Most-likely | |||||

| expected | expected | expected | expected | |||||

| duration | duration | duration | duration | |||||

| of emergency | of emergency | of emergency | of COVID-19 | |||||

| declaration | declaration | declaration | in Japan | |||||

| Later group | 4.42** | 0.17 | 9.052*** | 0.033 | ||||

| (1.89) | (1.32) | (3.037) | (0.387) | |||||

| Constant | 47.82*** | 27.73*** | 90.659*** | 9.752*** | ||||

| (1.34) | (0.90) | (2.116) | (0.264) | |||||

| Observations | 2857 | 2755 | 2759 | 2872 | ||||

Notes: This table displays the estimation results about the effects of new information on the expected duration of the emergency declaration. Panel (a) shows the results for firms in B-to-C service industries, and panel (b) for the rest of the firms. “Most-likely expected duration of emergency declaration” is the expected duration of the emergency declaration, defined by the number of days from May 8 until the most likely expected date when the emergency declaration is lifted in all prefectures. “Shortest expected duration of emergency declaration” (or “Longest expected duration of emergency declaration”) is defined in the same way as before based on the earliest (or latest) expected dates when the emergency declaration was lifted in all prefectures. “Most-likely duration of COVID-19 in Japan” is defined by the number of months from May 2020 until daily new infections become zero for the first time in Japan. “Later group” takes 1 if the firm was surveyed during May 15–17, and 0 if during May 8–9. “Suspension request” takes 1 if the suspension was requested of the firm’s industry in April or May, and 0 otherwise. “No suspension request” is defined by 1- “Suspension request.” The observations are weighted to match the number of firms in the Economic Census. Robust standard errors are in parentheses. for , for , and for .

Table 5 shows the estimation results based on the randomization of survey timing just before and after the government announcement. Among B-to-C service industries, our evidence using RCT shows that the expected year-to-year sales change in the Q2 (April–June) of 2020 improved by 4.8 percentage points on average over the week among firms in industry-prefectures that were subject to business suspension requests, although the estimate is statistically insignificant. The weak result here could be explained by the fact that the managers updated their expectations about the length of the emergency declaration only by 4 and 5 days over the week. On the other hand, firms in business to business service or non-service industries significantly improved their investment forecasts over the week. This result is consistent with a reduction of uncertainty about the length of the emergency declaration over the week.

Table 5.

Expected firm performance by survey week.

| (a) B-to-C service industries | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

| Expected | Expected | Expected | ||||

| sales | employment | investment | ||||

| growth Q2 | growth Q2 | Q2 | ||||

| Later group | 2.97 | -0.25 | 0.003 | |||

| (1.97) | (1.33) | (0.019) | ||||

| Later group Suspension request | 4.78 | 0.78 | 0.060 | |||

| (5.27) | (3.89) | (0.044) | ||||

| Later group No suspension request | 2.57 | 0.04 | 0.019 | |||

| (2.07) | (1.31) | (0.021) | ||||

| Suspension request | 9.00** | 9.16*** | 0.098*** | |||

| (3.93) | (2.93) | (0.035) | ||||

| Constant | 23.91*** | 22.10*** | 7.61*** | 5.77*** | 0.257*** | 0.237*** |

| (1.37) | (1.45) | (0.92) | (0.90) | (0.013) | (0.014) | |

| Observations | 3156 | 3156 | 3230 | 3230 | 3217 | 3217 |

| (b) Other industries (B-to-B service and non-service industries) | ||||||

| (1) | (2) | (3) | ||||

| Expected | Expected | Expected | ||||

| sales | employment | investment | ||||

| growth | growth | Q2 | ||||

| Q2 | Q2 | |||||

| Later group | 0.001 | 0.04 | 0.044** | |||

| (1.98) | (1.35) | (0.020) | ||||

| Constant | 15.27*** | 6.29*** | 0.269*** | |||

| (1.38) | (0.95) | (0.014) | ||||

| Observations | 2815 | 2878 | 2869 | |||

Notes: Panel (a) shows the results from the sample of firms in B-to-C service industries, and panel (b) shows the results from the other industries (business to business service and non-service industries). “Later group” takes 1 if the firm was surveyed during May 15–17, and 0 if during May 8–9. “Suspension request” takes 1 if the firm is in industry-prefectures that were subject to business suspension requests in April or May, and 0 otherwise. “No suspension request” is defined by 1- “Suspension request.” “Expected sales growth Q2” is the most likely expected sales growth in the Q2 (April–June) of 2020 relative to the same quarter in 2019, measured in percentage term. “Expected employment growth Q2” is measured by the log difference in the expected employment at the end of June 2020 and employment at the end of December 2019. “Expected investment Q2” is an indicator variable that takes a value of 1 if the firm plans to invest more than JPY 10,000, including investment already made, during Q2 2020, and 0 otherwise. The observations are weighted to match the number of firms in the Economic Census. Robust standard errors are in parentheses. for , for , and for .

Overall, the results reveal the magnitudes of a short-run trade-off between containing infection and sustaining economic performance for an anti-contagion policy. The facts that (1) the sales already declined in March before the emergency state, (2) it declined even among industries without business suspension request, and (3) the expected sales for the Q2 did not pick up among firms without business suspension requests after the partial lift of the emergency state, indicate that people change behaviors independently of the government declaration and that it affects business performance.

3.2. Can subsidies soften the economic damage of anti-contagion policies?

We next identify the effects of two subsidy schemes: the business continuation subsidy and short-time work compensation, exploiting Regression Discontinuity Design.

The business continuation subsidy grants up to JPY 1 million ( USD 10,000) to the self-employed and JPY 2 million ( USD 20,000) to small corporations, with limitations for the amount of the sales decline from the last year. The eligibility criteria are as follows: (1) at least one month of year-to-year sales in 2020 declined more than 50%; (2) the firm has continued business operations since before 2019; and (3) its capital is below JPY 1 billion or it employs fewer than 2000 employees in the case of corporations. The sales decline must be proven based on the sales ledger, which is the basis for the tax on profits. Therefore, it is highly costly for a firm to misreport numbers. The application process is simple: the eligible firm only needs to access the specific website and submit the form, the copy of its sales ledger, and its identity certificate. The transfer is usually made within 2 weeks of the application directly to the firm’s bank account. The subsidy scheme was announced on April 8 and applications opened on May 1. By the end of June, more than 2 million applicants had applied for and received subsidies totaling JPY 3 trillion, which is equivalent to about 3% of the total national budget in Japan in 2019. According to our survey data, the subjective probability of receiving this subsidy by the end of June 2020 was 37% on average.

The short-time work compensation reimbursed part of the payment of the leave allowance up to JPY 8330 per day per employee.2 This compensation was established in 1975 in response to exogenous and temporary recessions, such as oil shocks, under the premise that retaining the workforce was more efficient than reducing and reemploying workers for a temporary shock. Under normal economic conditions, to receive the subsidy, the firm has to show that it has maintained employment either by giving leave, training, or reallocating the workplace during a recession. To be eligible for short-time work compensation, firms had to show that their year-on-year monthly sales had dropped below -10% for 3 consecutive months, in principle. In March 2020, the sales decline criterion was relaxed to a 10% decline in a single month, as for the COVID-19-induced sales decline. On April 1, in response to the growing COVID-19 shocks, the sales decline criterion was further relaxed to a 5% decline in a single month in 2020. The application process was slightly complicated. The manager first has to agree to the leave plan with the relevant labor union. The firm then has to grant leave to employees, and only after paying the leave allowance, it can apply to the local labor office for the subsidy. The average subjective probability of receiving the subsidy by the end of June 2020 was 18% in our data.

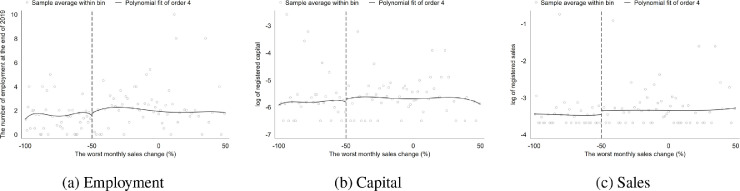

To estimate the impact of these subsidies, we adopt a regression discontinuity design using the cutoff in the eligibility criteria. To be eligible for the business continuation subsidy, sales in at least one month should declined more than 50% relative to the same month of the previous year. Therefore, we can consider a fuzzy regression discontinuity design for identifying the local average treatment effect of the perceived probability of receiving the business continuation subsidy. We use the minimum of year-on-year monthly sales during January–April 2020 as the running variable with the cutoff point at the value of -50%. The treatment variable is the subjective probability of receiving the business continuation subsidy from the central government by the end of June 2020. In Fig. 1 , we checked that the baseline employment, capital, and sales as of 2019 were all continuous at the threshold.

Fig. 1.

Covariate smoothness at the worst monthly sales change of 50%. Note: The employment is the number of employees at the end of 2019. The capital and sales are based on the registered information as of 2019.

Table 6 panel (a) shows the estimation results. The bias is corrected and the standard errors are robust to heteroskedasticity according to Calonico et al. (2014). The results suggest that a manager’s prospect for survival until the end of 2020 improves by 19.8 percentage points if the manager’s prospect of receiving the subsidy increases from 0 to 100%. This is a large effect given that the average subjective probability of continuing business until the end of 2020 is 82%, while the subsidy did not affect the firm’s quarterly investment and employment plans. As shown in Table 7 , we also find that the exogenously increased perceived probability of receiving the business continuation subsidy decreases temporary business suspension, establishment or section closure, and the adoption of working from home. This may be because the business continuation subsidy enabled firms with liquidity to keep operating business amid the COVID-19 crisis. On the contrary, the effects on the adoption of new information technology, expansion of online sales, selection of suppliers, and introduction of new product and service are insignificant. The message from these results is that the subsidy enabled small business managers to maintain the current business, but it was not large enough to change employment or to initiate new business.

Table 6.

Effect of the probability of receiving the business continuation subsidy and short-time work compensation.

| (a) Business continuation subsidy | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

| Survival probability | Employment growth | Investment | Disinvestment | |

| Subsidy probability | 0.198* | 0.000848 | 0.141 | 0.0532 |

| (0.116) | (0.00105) | (0.223) | (0.138) | |

| Observations | 5691 | 6108 | 6086 | 6081 |

| (a) Short-time work compensation | ||||

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

| Survival probability | Employment growth | Investment | Disinvestment | |

| Subsidy probability | 3.071 | 0.00286 | 3.151 | 1.151 |

| (5.928) | (0.0121) | (5.558) | (1.553) | |

| Observations | 3148 | 3385 | 3374 | 3371 |

Notes: This table shows the estimation results based on the regression discontinuity design using the cutoff points of eligibility criteria for the subsidies. Survival probability is the probability of continuing business until the end of 2020 (measured in %). Employment growth is log(expected employment at end-June 2020 + 1) subtracted by log(employment at end-2019). Positive investment is a binary indicator of more than JPY 10,000 planned investment from April to June 2020. Positive disinvestment is a binary indicator of planned disinvestment. In panel (a), subsidy probability is the probability of receiving the business continuation subsidy (measured in %). In panel (b), subsidy probability is the probability of receiving the short-time work compensation (measured in %). Standard errors are in parentheses. for , for , and for . The bias is corrected and the standard errors are robust to heteroskedasticity.

Table 7.

Effect of the probability of receiving the business continuation subsidy on firm behaviors.

| (a) Passive measures | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | |

| Business suspension | Employee suspension | Establishment closure | Underperforming Section closure | Cutting suppliers and buyers | |

| Subsidy probability | 0.334* | 0.0562 | 0.0708** | 0.118** | 0.270 |

| (0.190) | (0.180) | (0.0292) | (0.0559) | (0.186) | |

| Observations | 6108 | 6108 | 6108 | 6108 | 6108 |

| (b) Active measures | |||||

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | ||

| Facilitate IT | Work from home | Online sales | Develop new product and service | ||

| Subsidy probability | 0.0155 | 0.231* | 0.0549 | 0.0324 | |

| (0.124) | (0.137) | (0.148) | (0.144) | ||

| Observations | 6108 | 6108 | 6108 | 6108 | |

Notes: Standard errors are in parentheses. for , for , and for . Subsidy probability is the probability of receiving the business continuation subsidy (measured in %). The bias is corrected and the standard errors are robust to heteroskedasticity.

One possible concern for this analysis is the manipulation of the reported sales or the actual sales by the managers. In the current context, the manipulation of the reported sales would be limited. First, it is hard for the managers to misreport the sales to the government because they have to show their sales lodger, which is the basis for the tax calculation. Second, the managers have no incentive to misreport to us. Thus, the only way for them to manipulate the number is to actually delay the receipt of payment. However, the manipulation of the actual sales would be also limited. First, there was little time to plan this, because the announcement of the policy was at the end of March and we use data up to April. Second, delaying the receipt of cash should have been costly especially during the emergency state. As a robustness check, we also focused on the sample of business-to-consumer service sector, where the receipt of the money is likely to be when the transaction took place. Even though the statistical significance was lost, the sign and the magnitude of the effect of continuation subsidy was the same.

We similarly employ a regression discontinuity design to identify the effects of short-time work compensation. In this analysis, we focus on samples with at least one employee at the end of 2019, because only firms with employees can benefit from the subsidy. We use the April sales decline as the running variable with the cutoff point at the value of -5%. The treatment variable is the subjective probability of receiving the short-time work compensation from the central government by the end of June 2020. As shown in panel (b) of Table 6, we find no statistically significant effects on the firm’s business performance. As shown in Table 8 , we did not find any statistically significant effects on their behaviors. Even though the policy goal of this subsidy was to maintain employment, the effect on employment growth was not statistically significant, either.

Table 8.

Effect of the probability of receiving short-time work compensation on firm behaviors at the cutoff of April sales change being below -5%.

| (a) Passive measures | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | |

| Business suspension | Employee suspension | Establishment closure | Underperforming Section closure | Cutting suppliers and buyers | |

| Subsidy probability | 0.772 | 0.145 | 0.278 | 0.958 | 0.0157 |

| (1.684) | (1.732) | (0.641) | (1.081) | (0.943) | |

| Observations | 3385 | 3385 | 3385 | 3385 | 3385 |

| (b) Reactive measures | |||||

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | ||

| Facilitate IT | Work from home | Online sales | Develop new product and service | ||

| Subsidy probability | 0.0488 | 1.454 | 0.133 | 0.346 | |

| (1.319) | (2.647) | (1.014) | (0.946) | ||

| Observations | 3385 | 3385 | 3385 | 3385 | |

Notes: Standard errors are in parentheses. for , for , and for . Employment growth is log(expected employment at end-June 2020 + 1) subtracted by log(employment at end-2019). Positive investment is a binary indicator of more than JPY 10,000 planned investment from April to June 2020. Positive disinvestment is a binary indicator of planned disinvestment. Survival probability is the probability of continuing business until the end of 2020 (measured in %). Subsidy probability is the probability of receiving the short-time work compensation (measured in %). The bias is corrected and the standard errors are robust to heteroskedasticity.

The difference between the effect of the business continuation subsidy and short-time work compensation may be partly due to the lack of power. If we focus on the same sample, firms with positive employment at the end of 2019, the effect of business continuation subsidy becomes statistically insignificant, though the estimate is almost unchanged. Another reason may be that this subsidy was not attractive enough for small business managers targeted in this survey compared to the business continuation subsidy, for several reasons: there is additional paper work for the application and it is necessary to give leave to employees to receive the subsidy and to reimburse the leave allowance.

3.3. How would the infection containment affect the business in the medium run?

Finally, we find that the medium-term firm performance prediction in 2020 is affected to a large extent by infection containment and the possibility of hosting the Olympics by applying Difference-in-Difference strategy. This point is important to assess the potential dynamic complementarity between the anti-contagion policies and future economic performance.

For the identification, we use the panel structure of quarterly sales and the variation in expected quarterly timing of infection containment across firms. More specifically, we treat the realized and expected firm sales growth across quarters in 2020 as quarter-firm level panel data and estimate the following equation:

| (2) |

where represents quarters in the calendar year of 2020, and is sales growth in quarter relative to the same quarter in the previous year, which is the realized value for Q1 and the expected values for Q2–Q4. We control for the firm-specific constant unobserved growth rates by the firm-specific fixed effects , and the unobserved expected macro-level shocks by the quarter-specific fixed effects . “(After zero infection)” takes a value of 1 from the quarter when firm expects zero infections to be achieved for the first time, and 0 otherwise. Similarly, “(After mass use of vaccine)” takes a value of 1 from the quarter when firm expects mass vaccination to become available, and 0 otherwise. The key idea behind this equation is how managers expect their sales to recover in response to the infection ending or vaccine use. The variation across managers in expectations about the timing of the events enables us to identify the expected effect of such events on performance. The sales recovery may not exactly start from the quarter of the event but somewhat earlier than that. For instance, a small-scale start of use of vaccine (not necessarily mass use) could be considered to be sufficient for improving firms’ business condition. To allow such possibilities, we add “(After mass use of vaccine),” which takes 1 from the quarter prior to the quarter when mass vaccination to become available. “(After zero new infection)” is defined in a similar manner. We also examine the effect of the expectation about whether Japan will host the Olympics. In Eq. 2, “” is manager ’s subjective probability that Japan would host the Olympics in 2021. We interact this subjective probability with quarter dummies for Q3 and Q4.

The result shown in the first column of Table 9 indicates that firms’ sales growth is expected to improve by 2.2 percentage points on average in the quarter when the number of new infections becomes zero in Japan, and further improve by around 2.4 percentage points on average in the quarter prior to the time when a vaccine to curb the spread of the virus starts to be used on a mass scale in Japan. In addition, firms that expect a 100% chance of hosting the Tokyo Olympic Games in 2021 forecast on average a 5.4 percentage point larger improvement in sales growth in the Q4 than do firms expecting no chance. This is surprising because few firms in our survey had or will have contract directly related to Olympic business. In summary, this result indicates large magnitudes of gain from infection containment in the medium run.

Table 9.

Difference-in-difference for quarterly sales growth: COVID-19, vaccine, and Olympics.

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sales | Sales | Sales | Sales | |

| growth | growth | growth | growth | |

| VARIABLES | Q1–Q4 | Q1–Q4 | Q2–Q4 | Q2–Q4 |

| After zero new infection | 2.18*** | 2.47*** | 2.48** | 2.29** |

| (0.82) | (0.90) | (1.01) | (1.00) | |

| After zero new infection (t+1) | 0.80 | 0.53 | 0.61 | 0.46 |

| (0.76) | (0.82) | (0.87) | (0.87) | |

| After mass use of vaccine | 0.37 | 0.31 | 0.54 | 0.49 |

| (0.85) | (0.87) | (0.93) | (0.92) | |

| After mass use of vaccine (t+1) | 2.41*** | 2.33*** | 2.33** | 2.32** |

| (0.81) | (0.88) | (0.99) | (0.97) | |

| P(Olympic) Q3 | 3.15* | 3.15* | 2.58 | 3.42* |

| (1.61) | (1.61) | (1.88) | (1.90) | |

| P(Olympic) Q4 | 5.37*** | 5.46*** | 4.92** | 5.71** |

| (1.81) | (1.83) | (2.23) | (2.25) | |

| Observations | 24,125 | 24,125 | 18,017 | 18,017 |

| Firm FE | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Quarter FE | YES | YES | YES | NO |

| Optimism proxiy | NO | YES | NO | NO |

| Industry-Quarter FE | NO | NO | NO | YES |

Notes: This table uses the panel data of quarterly firm sales growth in Q1–Q4 or Q2–Q4 in 2020. Sales growth in Q1 is the realized value, while sales growth in Q2–Q4 is expectation by the business owner. The observations are weighted to match the number of firms in the Economic Census. Standard errors are clustered at the level of firms. “Mean Qk” (for k = 2, 3, 4) shows the mean of the expected sales growth in Q3 and Q4 in the sample (respectively).

This result is robust to additionally controlling for general optimism/pessimism of the respondents about COVID-19-related outcomes that may also be correlated with sales growth expectations. To clarify this point, decompose the error term into an optimism/pessimism bias term () and the remaining term (), i.e., . The bias term appears only in the equations for future sales in , and it is zero for . If “After zero infection” or “After mass use of vaccine” is correlated with (e.g., optimistic managers are more likely to expect higher growth and higher chance of having “After zero infection”), then not controlling for will bias the estimate of , even if we control for firm fixed effects. We cope with this possibility in three alternative ways.

We first consider the case in which is constant across future quarters for each firm, that is, . Then, one solution is to control for proxy variables of only after Q2. As proxy variables of , we use two variables: (1) the number of months until daily new infections become zero and (2) the number of months until a vaccine is used at mass scale. Note that, while these variables are used in the equation already, we now use these variables to control for the overall level of expectations in all future quarters, rather than to capture the timing. These variables are interacted with a dummy variable that takes 1 during Q2–Q4 (future quarters) in the second column. The results change little. An alternative way to deal with the optimism/pessimism issue is to drop Q1 and to keep controlling for firm fixed effects, which would control for altogether. In this specification, we set the baseline quarter as Q2, and estimate the effect of COVID-19-related expectations on the sales growth in Q3 and Q4 relative to Q2. The results are shown in the third column. Again, the results are robust to this specification. Next, we consider the case in which the optimism-pessimism bias might not stay constant over quarters within firms but might vary across seasons. For example, since Christmas season is important for retail firms, these firms may hope, or expect optimistically, that infections will end by that time. To check such possibilities, we additionally control for industry-quarter fixed effects in the fourth column using the data for Q2–Q4. This does not alter the qualitative results, either.

4. Conclusion

We derive several important policy implications from these observations. First, the anti-contagion policies should be timely and contained to the short run. Based on a back-of-the-envelope calculation, a business suspension request for a month reduces B-to-C service firms’ monthly sales by around JPY 0.13 million (around USD 1,200) on average, relative to their average monthly sales of JPY 1.3 million (around USD 12,000). Second, their performance is strongly influenced by people’s voluntary behaviors to avoid infections: even without a suspension request, their sales would have dropped by JPY 0.1 million (around USD 1,000). Third, to effectively save small businesses suffering from the crisis by subsidies, the business continuation subsidy was more effective. Based on a back-of-the-envelope calculation, without the business continuation subsidy, the nationwide number of surviving small business would have dropped from 3.63 million to 3.29 million and the number of employed in small businesses from 12.07 million to 11.01 million. Lastly, stringent anti-contagion policies do not necessarily contradict the longer-run economic goal. At the margin, the containment of infections is expected to increase quarterly sales by JPY 0.34 million: the longer the pandemic continues, the larger the loss of sales would accumulate. Finally, at least in the Japanese context, if infection could be controlled sufficiently to host the Tokyo Olympics, sales are expected to recover further by JPY 0.83 million on average in the Q4 (October–December) of 2020.

This study contributes to the literature in three ways. First, we identify the effects of anti-contagion policies on firm performance, separately from other effects, such as consumers’ behaviors to avoid infections, using a similar approach to that of Chernozhukov et al. (2020). There are increasing empirical studies about the effects of COVID-19 anti-contagion policies on people’s movements and infection cases (Hsiang, Allen, Annan-Phan, Bell, Bolliger, Chong, Druckenmiller, Huang, Hultgren, Krasovich, Lau, Lee, Rolf, Tseng, Wu, 2020, Imperial College COVID-19 Response Team, Flaxman, Mishra, Gandy, Unwin, Mellan, Coupland, Whittaker, Zhu, Berah, Eaton, Monod, Ghani, Donnelly, Riley, Vollmer, Ferguson, Okell, Bhatt, 2020, Zhang, Litvinova, Liang, Wang, Wang, Zhao, Wu, Merler, Viboud, Vespignani, Ajelli, Yu, 2020, Fang, Wang, Yang, 2020, Chernozhukov, Kasahara, Schrimpf, Goolsbee, Syverson, 2020). Among them, a study closely related to ours is that of Goolsbee and Syverson (2020) using cellular phone records in the U.S. and showing that legal shutdown orders explain only a small share of the overall reduction of consumer visits to businesses. Fairlie (2020) describes the performance of small business in the early stage of the pandemic. However, causal evidence of anti-contagion policies on business performance is still scarce. We contribute to this literature by examining the effects of anti-contagion policies on (realized and expected) employment, and investment, as well as sales.

Second, we identify the causal effects of subsidies related to the COVID-19 pandemic. Although governments worldwide have set up stimulus packages, such as direct payments to firms and households, compensation for laid-off workers, and the opening of credit lines, few studies have yet measured the effects of subsidies related to COVID-19 and identified the causal effects.3 We estimate the effects of two types of subsidy schemes, which differ by nature and target, exploiting the cutoff policies in the eligibility criteria.

Third, our study contributes to literature on the effects of expectations and uncertainty exploiting the exogenous shock triggered by the COVID-19 pandemic. There is growing empirical literature on the expectations of firms’ managers using survey data (e.g., Coibion and Gorodnichenko, 2012 and Bloom et al., 2020). Baker et al. (2020a) show for the U.S. and U.K. that the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic has led to sharp increases in policy and economic uncertainty. Bartik et al. (2020) document the impacts of the COVID-19 crisis on small U.S. business, showing a positive association between expected duration of the crisis and business closure. To this body of literature, we newly provide causal evidence on how managers’ sales and business continuation forecasts are affected by their expectations on government anti-contagion and subsidy policies and the infection containment.

There are several limitations to this study. First, the data are mostly about expectations rather than actual economic outcomes. By focusing on managers’ expectations in this study, we answered important policy-relevant questions in the midst of ongoing crisis. However, the analysis should be followed up by further analysis using data on the realized economic outcomes. We aim to continue this survey on a quarterly basis throughout 2020. Second, the sample of this study was restricted to small businesses in Japan. Although we focused on small businesses because they seem to be the most vulnerable to the COVID-19-induced economic crisis and many economic support policies in Japan targeted them, an analysis covering larger firms as well as households is necessary to fully understand the economic impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic and the subsequent anti-contagion policies.

Footnotes

This study is supported by Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (grant numbers 18H00846, 19H00589, 18K18567, and 16H06322), the Joint Usage and Research Center, Institute of Economic Research, Hitotsubashi University, Japan Securities Scholarship Foundation, and the crowdfunding at academist, Inc. We thank participants of seminars at Hitotsubashi University, The University of Tokyo, Keio University, RIETI, Kansai Labor Seminar, Tokyo Keizai University, Contract Theory Workshop, Hong Kong Japan Entrepreneur Association, METI, SMBC Nikko, Mitsubishi UFJ Research & Consulting, and Academist, for helpful comments. Hiroshi Kumanomido, Kensei Nakamura, Yusuke Obata, and Rintaro Ono provided excellent research assistance.

Among B-to-C service industries, business suspension was requested to travel, hotel, restaurant (including bars), entertainment, school, and other education service industries in some prefectures. Retail industry, which is also included in B-to-C service industries, was not requested for suspension in any prefecture.

The maximum amount to be paid was later increased to 15,000 yen.

Bartik et al. (2020) and Baker et al. (2020b) describe how firms and households responded to the 2020 Coronavirus Aid, Relief and Economy Security Act, which directed cash payments. Granja et al. (2020) studies how the Paycheck Protection Program, which offered guaranteed loans to small businesses that maintained employment, was distributed. De Marco (2020) studies a similar public credit guarantee scheme for small businesses to tackle the COVID-19 crisis in Italy.

Appendix A

A1. Data cleaning

In the process of data validation checks, first, we restricted the sample for our analysis to respondents who answered that their current job was still the top manager. Some respondents who had registered as managers at the time of annual registration renewal changed occupations from managers to non-managers or became unemployed by the time of our survey. Among 12,364 total responses, 1,401 respondents were not top managers, self-employed, or freelancers at the time of the survey. After dropping these respondents, we are left with 10,963 samples.

Next, we detected and dropped inconsistent or unrealistic answers in the following four steps. We first dropped 1089 samples whose response time was unreasonably short, that is, less than 10 percentile of all response time, which was approximately 4 min. Second, we dropped samples whose answers on the number of employees in the survey was substantially inconsistent with the information that they provided to the survey company when they registered as respondents. Specifically, we did not use samples whose answers on employment size differed by at least 3 ranks among 13 ranks (less than 5, 5–9, 10–19, 20–29, 30–49, 50–99, 100–199, 200–299, 300–499, 500–999, 1000–2999, 3000–4999, and 5000 or more) between the registered number and the number at the end of 2019, or between the end of 2019 and the end of March 2020. Through this process, 650 samples out of 9874 remaining samples were dropped. Third, among the remaining 9224 samples, 409 respondents are considered to have miss-reported at least one sales growth in January–April (realizations) or Q2–Q4 (expectations), specifically, reporting a value less than -100 or more than 200. After dropping these respondents, we were left with 8815 sample. Fourth, among the rest, 2323 respondents filled exactly the same value for all of the sales growth in January–April (realizations) or Q2–Q4 (expectations), therefore, we consider that they might not have answered the survey seriously and dropped them from our analysis sample.

Lastly, we restricted the sample to respondents whose number of employees, including the manager, was no greater than 20. This is the definition of a small business by the Japanese government. Among the remaining 6492 samples, 384 respondents have 20 or more employees.

Furthermore, we modified the answers to correct the potential response errors. In particular, if the answered latest date of the lifting of the emergency declaration was earlier than the answered earliest date, it was likely that the individual meant the opposite. In this case, we exchanged these answers. We applied the same modifications to the timing of infection containment and the start of the mass vaccination against SARS-Cov-2. Some respondents seemed to have answered the sales growth (relative to the same month in the last year) by normalizing the sales in the same month in the last year at 100 rather than at 0. We detected such cases by the following criteria: the answered sales growth in January was above 70 and none of the values for sales growth in February, March, or April were non-negative. When we detected such respondents, we replaced the sales growth in January–April by subtracting 100. Regarding the expected quarterly sales growth in Q2–Q4, we used the following criteria: the answered sales growth in January was above 70, none of the values for sales growth in the Q2, Q3, and Q4 was non-negative, and the sales growth in April minus 100 was between the minimum and maximum predicted Q2 sales. Again, for such respondents, we replaced the expected sales growth in Q2–Q4 by subtracting 100.

Our sampling frame consists of 28,169 individuals who were registered as top managers, the self-employed, and freelancers at Macromill, Inc., which is one of the largest market research companies in Japan. We have basic information about all individuals in the sampling frame provided by the firm. This information was provided by the individuals to the research agency when they registered at the company, agreeing that they would receive invitations for surveys like ours in the future. To check selection bias, we first document the characteristics of respondents compared to the individuals in the sampling frame in panel (a) of Table A1 . The respondents are more likely to operate smaller business, and they tend to be older and male, compared to the individuals in the sampling frame. We next examine the characteristics of respondents in our analysis sample (after dropping sample through data cleaning) compared to all respondents in panel (b) of Table A1. Here, the analysis sample keeps respondents having more than 20 employees, to observe the results of dropping through other features. The sample used in this analysis tends to have fewer employees, less capital, and fewer sales, and tends to be older and male.

Table A1.

Response selection check of survey date.

| (a) Characteristics of respondents compared to individuals in sampling frame | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

| VARIABLES | ln(firm emp) | ln(estab emp) | ln(caiptal) | ln(sales) | age | male |

| respondent | 0.10*** | 0.09*** | 0.09*** | 0.10*** | 3.06*** | 0.11*** |

| (0.02) | (0.01) | (0.02) | (0.02) | (0.14) | (0.00) | |

| Observations | 26,561 | 26,556 | 20,067 | 20,877 | 28,169 | 28,169 |

| R-squared | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.017 | 0.016 |

| Mean dep var | 1.501 | 1.415 | 1.524 | 3.924 | 52.04 | 0.775 |

| (b) Characteristics of individuals in the analysis sample compared to respondents | ||||||

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

| VARIABLES | ln(firm emp) | ln(estab emp) | ln(caiptal) | ln(sales) | age | male |

| satisfying criteria | 0.09*** | 0.07*** | 0.16*** | 0.17*** | 0.54** | 0.03*** |

| (0.02) | (0.02) | (0.04) | (0.03) | (0.22) | (0.01) | |

| Observations | 9219 | 9176 | 7173 | 7710 | 9224 | 9224 |

| R-squared | 0.002 | 0.002 | 0.003 | 0.004 | 0.001 | 0.001 |

| Mean dep var | 1.236 | 1.196 | 1.306 | 3.684 | 55.30 | 0.872 |

Notes: “Satisfying criteria” in Panel (b) means the sample satisfying criteria except for employment size, because only firms with 20 or fewer employees are used in this analysis. “Later group” in Panels (c) and (d) indicates samples from the later survey sent on May 15 compared with the samples from the earlier survey sent on May 8.

A2. Sampling weight

As our sample is not necessarily a representative of small business in Japan, the observations are weighted to match the number of small business in the Economic Census, which is conducted by the National Statistic Bureau, by 12 categories of employment size and sectors. Table A2 shows the summary statistics of our sample without weighting. The average number of employees excluding top managers him/herself is 1.73. Firms that do not have any employees (excluding the managers themselves) comprise 46%, and those with 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5–19 employees comprise 23%, 10%, 6%, 3%, and 12%, respectively. By contrast, the firms having 1, 2, 3, 4, 5–9, and 10–19 workers including managers in the Economic Census are 22%, 21%, 12%, 9%, 22%, and 14%, respectively. Therefore, our sample tends to over-represent smaller firms. As for industry composition, small businesses in service industry comprise 83% of our sample, while the correspondent figure is 82% in the Economic Census. Throughout our analysis, we report weighted estimations, except for the analysis using regression discontinuity design (for which can obtain only local estimates). The weights are defined by the ratio of the number of small business in the Economic Census 2016 to the number in our sample by 12 categories: 6 employment size categories (as described above) and 2 sectors (service and non-service).

Table A2.

Summary statistics (without weight).

| mean | sd | min | max | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of employees | 1.73 | 2.90 | 0 | 28 |

| Number of employees: 0 | 0.46 | 0.50 | 0 | 1 |

| Number of employees: 1 | 0.23 | 0.42 | 0 | 1 |

| Number of employees: 2 | 0.10 | 0.30 | 0 | 1 |

| Number of employees: 3 | 0.06 | 0.24 | 0 | 1 |

| Number of employees: 4 | 0.03 | 0.18 | 0 | 1 |

| Number of employees: 5-19 | 0.12 | 0.32 | 0 | 1 |

| Industry: Business to Consumer service | 0.53 | 0.50 | 0 | 1 |

| Industry: Business to Business service | 0.20 | 0.40 | 0 | 1 |

| Industry: Non-service | 0.27 | 0.45 | 0 | 1 |

| Average age | 55.45 | 9.68 | 21 | 89 |

| Manager age: 20s | 0.00 | 0.07 | 0 | 1 |

| Manager age: 30s | 0.05 | 0.21 | 0 | 1 |

| Manager age: 40s | 0.21 | 0.41 | 0 | 1 |

| Manager age: 50s | 0.40 | 0.49 | 0 | 1 |

| Manager age: 60s | 0.26 | 0.44 | 0 | 1 |

| Manager age: 70s | 0.08 | 0.27 | 0 | 1 |

| male | 0.88 | 0.33 | 0 | 1 |

| realized sales growth in Jan 2020 compared to the last year | 0.04 | 24.20 | -100 | 200 |

| realized sales growth in Feb 2020 compared to the last year | 3.04 | 27.95 | -100 | 180 |

| realized sales growth in March 2020 compared to the last year | 10.42 | 38.17 | -100 | 160 |

| realized sales growth in April 2020 compared to the last year | 18.63 | 47.53 | -100 | 160 |

| realized sales growth in 1Q 2020 compared to the last year | 4.50 | 24.97 | -100 | 127 |

| expected sales growth in 2Q 2020 compared to the last year | 19.94 | 46.96 | -100 | 120 |

| expected sales growth in 3Q 2020 compared to the last year | 12.21 | 42.40 | -100 | 180 |

| expected sales growth in 4Q 2020 compared to the last year | 8.36 | 41.49 | -100 | 180 |

| realized investment in Q1 is positive | 0.27 | 0.44 | 0 | 1 |

| realized disinvestment in Q1 is positive | 0.05 | 0.21 | 0 | 1 |

| expected investment in Q2 is positive | 0.24 | 0.43 | 0 | 1 |

| expected disinvestment in Q2 is positive | 0.06 | 0.24 | 0 | 1 |

| probability of business survival | 81.59 | 24.81 | 1 | 100 |

| probability of receiving the continuation subsidy | 36.78 | 41.82 | 0 | 100 |

| probability of receiving the short-time work compensation | 14.79 | 30.10 | 0 | 100 |

| probability of receiving the business suspention subsidy | 16.27 | 31.62 | 0 | 100 |

| probability of hosting olympic in 2020-2021 | 41.16 | 29.74 | 0 | 100 |

| Observations | 6108 |

A3. Balancing test of survey week randomization

We check the characteristics of respondents in our sample across survey weeks, earlier week (May 8–9) and later week (May 15–17). The panels (a) and (b) of Table A3 show that there is no statistically significant difference in employment, capital, sales, investment, manager’s status (top manager or self-employed), age, and sex by survey week.

Table A3.

Balancing test of survey date randomization.

| (a) Characteristics of respondents in later week compared to individuals in the analysis sample | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | ||

| VARIABLES | ln(firm emp) | ln(estab emp) | ln(caiptal) | ln(sales) | age | male | |

| later group | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.05 | 0.02 | 0.10 | 0.00 | |

| (0.01) | (0.01) | (0.03) | (0.02) | (0.25) | (0.01) | ||

| Observations | 6108 | 6086 | 4886 | 5256 | 6108 | 6108 | |

| R-squared | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |

| Mean dep var | 1.079 | 1.067 | 1.191 | 3.528 | 55.45 | 0.879 | |

| (b) Characteristics of respondents in later week compared to individuals in the analysis sample (continued) | |||||||

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | |

| expected | expected | expected | expected | ||||

| sales growth | sales growth | sales growth | sales growth | ||||

| in Jan 2020 | in Feb 2020 | in March 2020 | in April 2020 | ||||

| lifted | compared to | compared to | compared to | compared to | investment | ||

| VARIABLES | self-employed | on May 14 | the last year | the last year | the last year | the last year | in Q1>0 |

| later group | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.67 | 0.11 | 0.05 | 1.68 | 0.00 |

| (0.01) | (0.01) | (0.62) | (0.72) | (0.98) | (1.22) | (0.01) | |

| Observations | 6,108 | 6,108 | 6,108 | 6,108 | 6,108 | 6,108 | 6,076 |

| R-squared | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| Mean dep var | 0.802 | 0.476 | 0.0359 | 3.040 | 10.42 | 18.63 | 0.269 |

Notes: “Satisfying criteria” in Panel (b) means the sample satisfying criteria except for employment size, because only firms with 20 or fewer employees are used in this analysis. “Later group” in Panels (c) and (d) indicates samples from the later survey sent on May 15 compared with the samples from the earlier survey sent on May 8.

A4. The emergency declaration and business suspension requests

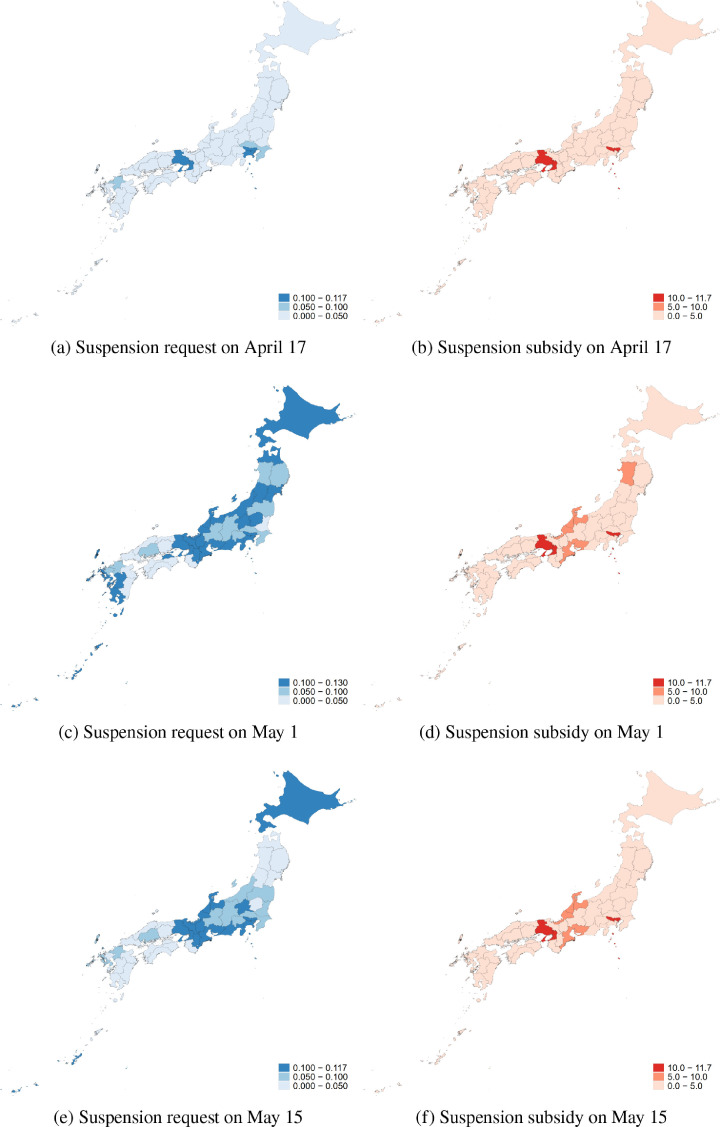

The emergency declaration Responding to an increasing number of infections, on April 7, then prime minister Shinzo Abe declared a state of emergency until May 6 for seven prefectures (Tokyo, Kanagawa, Saitama, Chiba, Osaka, Hyogo, and Fukuoka), which had relatively larger numbers of infections, as shown in Map (a) in Fig. A1 . Based on the Act of Special Measures, the emergency declaration gave local governments the legal basis to issue business suspension requests, and to request voluntary bans on going out. Following this, prefectures under the emergency declaration started to request the suspension of business at several facilities, such as dance halls, movie theaters, and sports clubs. These requests have no legal force and penalties cannot be imposed for ignoring them. These initial suspension requests were accompanied by subsidies in most cases. Some prefectures also publicized the names of companies that did not follow the requests on their websites. On April 16, the central government extended coverage of the emergency declaration to all prefectures in Japan and other local governments also started to request the suspension of businesses, as shown by Map (b) in Fig. A1.

Fig. A1.

Prefectures under emergency declaration by dates.

On April 30, Abe informally announced that the period of the emergency declaration would be extended, and on May 4, the government formally extended the emergency declaration for all prefectures to May 31, indicating that it could be lifted earlier depending on the situations, with a review due around May 14. On May 10, the Minister of Economic and Fiscal Policy mentioned that 34 prefectures that were not under special precautions would have their emergency declaration lifted on May 14 for restarting of business in these areas, while the remaining 13 prefectures with relatively more infections would continue to be under the emergency declaration. On May 13, the government indicated that the emergency declaration in 39 prefectures (including the previously mentioned 34 prefectures) was expected to be lifted, and this decision was formalized on May 14 at a meeting with experts, as shown by Map (c) in Fig. A1. The government kept the remaining prefectures (Hokkaido, Tokyo, Kanagawa, Chiba, Saitama, Osaka, Hyogo, and Kyoto) under an emergency declaration, indicating that the possibility of lifting it would be re-examined on May 21. At the same time, the government announced the following guidelines for lifting the emergency declaration for the remaining prefectures: (1) the number of new infections should be less than 0.5 per 100,000 people in a week; (2) tightness of medical capacity; and (3) improvement of preparedness of PCR testing conditions. On May 15, reflecting the reported number of daily new infections as 9 in Tokyo prefecture (which has a population of around 9.2 million), the Minister of Economic and Fiscal Policy commented that “if Tokyo continues to have less than 10 infections every day for a week, this will help satisfying the conditions in the guideline.” The emergency declaration was lifted in Osaka, Hyogo, and Kyoto on May 21. On May 25, the government declared the end of the emergency declaration for all of remaining prefectures.

The local governments’ business suspension requests Following the emergency declaration, prefectures started to request business suspension for several types of facilities. The left three panels of Fig. A2 in the Appendix show how the fraction of industries in a prefecture that are subject to the business suspension request evolved over time. On April 17, the requests were restricted to metropolitan areas, such as Tokyo, Osaka, and Hyogo. Thereafter, the request was expanded to a wider area: on May 1, in almost all prefectures, some businesses were requested to suspend operations. Because the emergency declaration was lifted in 39 prefectures on May 14, these prefectures followed up by lifting the business suspension requests on May 15. The requests tended to be targeted at a few industries in which many visitors could gather in close proximity, such as travel businesses, schools, restaurants, hotels, entertainment businesses, and educational businesses, although the targets varied across prefectures.

Fig. A2.

Suspension request and subsidy at prefecture level. Notes: The suspension status is in percentages. The suspension subsidy is in JPY 10,000.

References

- Allcott H., Boxell L., Conway J.C., Gentzkow M., Thaler M., Yang D.Y. Working Paper, 26946. National Bureau of Economic Research; 2020. Polarization and Public Health: Partisan Differences in Social Distancing during the Coronavirus Pandemic. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker S.R., Bloom N., Davis S.J., Terry S.J. Working Paper, 26983. National Bureau of Economic Research; 2020. COVID-Induced Economic Uncertainty. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Baker S.R., Farrokhnia R.A., Meyer S., Pagel M., Yannelis C. Working Paper, 27097. National Bureau of Economic Research; 2020. Income, Liquidity, and the Consumption Response to the 2020 Economic Stimulus Payments. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bartik A.W., Bertrand M., Cullen Z., Glaeser E.L., Luca M., Stanton C. The impact of COVID-19 on small business outcomes and expectations. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2020;117(30):17656–17666. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2006991117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benzell S.G., Collis A., Nicolaides C. Rationing social contact during the COVID-19 pandemic: transmission risk and social benefits of US locations. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2020;117(26):14642–14644. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2008025117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bloom N., Davis S.J., Foster L., Lucking B., Ohlmacher S., Saporta Eksten I. 2020. Business-Level Expectations and Uncertainty. (Becker Friedman Institute for Economics Working Paper No. 2020-181.). [Google Scholar]

- Calonico S., Cattaneo M.D., Titiunik R. Robust nonparametric confidence intervals for regression-discontinuity designs: robust nonparametric confidence intervals. Econometrica. 2014;82(6):2295–2326. doi: 10.3982/ECTA11757. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chernozhukov, V., Kasahara, H., Schrimpf, P., 2020. Causal impact of masks, policies, behavior on early Covid-19 pandemic in the U.S.medRxiv 2020.05.27.20115139. 10.1101/2020.05.27.20115139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Coibion O., Gorodnichenko Y. What can survey forecasts tell us about information rigidities? J. Polit. Econ. 2012;120(1):116–159. doi: 10.1086/665662. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- De Marco F. Public guarantees for small businesses in Italy during COVID-19. SSRN Electron. J. 2020 doi: 10.2139/ssrn.3604114. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fairlie R. The impact of COVID-19 on small business owners: evidence from the first three months after widespread social-distancing restrictions. J. Econ. Manag. Strategy. 2020;29(4):727–740. doi: 10.1111/jems.12400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang H., Wang L., Yang Y. Working Paper, 26906. National Bureau of Economic Research; 2020. Human mobility restrictions and the spread of the novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) in China. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flaxman S., Mishra S., Gandy A., Unwin H.J.T., Mellan T.A., Coupland H., Whittaker C., Zhu H., Berah T., Eaton J.W., Monod M., Ghani A.C., Donnelly C.A., Riley S.M., Vollmer M.A.C., Ferguson N.M., Okell L.C., Bhatt S. Estimating the effects of non-pharmaceutical interventions on COVID-19 in Europe. Nature. 2020:1–8. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2405-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glover A., Heathcote J., Krueger D., Ríos-Rull J.-V. Working Paper, 27046. National Bureau of Economic Research; 2020. Health versus Wealth: On the Distributional Effects of Controlling a Pandemic. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Goolsbee A., Syverson C. Technical Report, 2020-80. 2020. Fear, lockdown, and diversion: comparing drivers of pandemic economic decline 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]