Abstract

The COVID-19 pandemic has implications for coastal planning and management. Rules for isolation and physical distancing, among other measures for human life protection, have led to the closure of most beaches around the world. The present critical situation has raised the following question: How can some recommendations be designed in sun, sea, and sand tourism-dependent-insular countries to face “the COVID-19 new normality?” We used the content analysis technique to analyze representative publications on a global level to ascertain information on best management practices. A survey of 58 experts provided additional information. We used inferential statistics for sample selection and produced a list of 43 practices and beach planning and management actions to face the COVID-19 pandemic. This led to 27 new recommendations designed for beach planning and management within insular contexts, some of which were tested in the Republic of Cuba. Recommendations aim to guarantee a culture of safety and improvement within the field of beach or coastal planning and management. These recommendations should prove useful for other insular countries, during the COVID-19 period, in the new normality that follows, and in other post-pandemic scenarios.

Keywords: Coastal planning, Beach management, Knowledge networks, Small island developing states, Cuba.

Graphical abstract

1. Introduction

The global pandemic caused by COVID-19, a disease associated with the most recent SARS-coV-2 coronavirus (Galib B, 2020), threatens the sustainable development of coastal territories (Pirouz, Bet al, 2020). Its effects impacted society and the environment on a global scale (Chakrabortya et al., 2020), as well as the world economy in a manifold way (Liu et al., 2020). Extensive coastlines and beaches help define insular island nations and thus render them vulnerable to the risks associated with the pandemic.

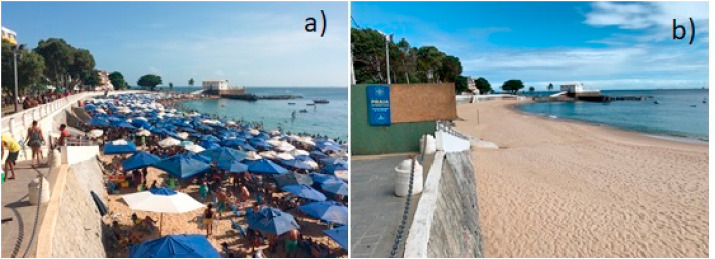

Native islanders and tourist keep beaches crowded during normal times (Botero et al., 2018). This historical form of use means close socialization and heightened risk for transmitting and contracting COVID-19. To reduce rates of disease transmission most countries applied new regulations to beaches (Fig. 1 ). Unfortunately, many beach-gowers ignored the emergency regulations. Consequently, places known for attractive beaches suffered outbreaks of the disease. This includes places such as Cancun and Playa del Carmen, in Mexico; Miami, in the United States; Buyé Beach in Cabo Rojo, the insular state of Puerto Rico, and Playa del Pero, Brazil (Daza 2020).

Fig. 1.

Urban beach Porto da Barra, Brazil (a) Before COVID-19 (b) In COVID-19 lockdown. Date: august 12th (Sourse: Souza Filho).1

Articles in the popular press and scientific journals question whether the beaches should be open or not during the pandemic (Daza, 2020; Gobierno Vasco 2020; Departamento de Salud, 2020). This includes analysis of post-COVID-19 scenarios (Botero et al., 2020a) and, identifying gaps in knowledge about the perception of risk for COVID-19, as well as protection strategies used by bathers (Zielinski and Botero, 2020). Other articles evaluate Covid-19's impact on the tourism industry (Shih-Shuo, 2020), with special attention on the airline and hotel business (Lee-Peng et al., 2020). A few pieces evaluate the impact of the Coronavirus pandemic on the psyche of tourists, (Kock et al., 2020; (Hsiang et al., 2020). The practices and actions of governments regarding zoning, planning, and management of the beaches during the pandemic receive less attention (Milanes et al., 2020; Bianchi et al., 2020).

The relationship between beach planning and coastal management in the face of COVID-19 is only now emerging in the scientific literature (Botero et al., 2020b, Botero et al., 2020a). Most of the available reports come from the popular press and the internet (Reportur, 2020; Daza, 2020; Niusdiario.es., 2020; www.elpais.com.co; www.elheraldo.co ; El Heraldo 2020a,b), showing the design of some standards (IMPLAN, 2020; Departamento de Salud, 2020), manuals (APA, 2020) guidelines (Gobierno de México, 2020a,b; Ministerio de Salud, 2020), protocols (Gobierno de México 2020c.), sanitary criteria (Gobierno Vasco, 2020) and resolutions (Resolución 1538 del 2020). These mostly use the main measures of isolation and physical distancing proposed by the World Health Organization (www.who.int/es) or, by the Pan American Health Organization (www.paho.org/es).

On the internet, it is also possible to find data on the behavior of beach users (Daza, 2020). There are reports of crowded beaches during the COVID-19 lockdown (Reportur, 2020; Niusdiario.es., 2020). We found European cases of inadequate infrastructures on beaches for avoiding contagion (El Correo, 2020). Presently missing is information on measures taken by island nations in response to the pandemic and specifications for beach planning.

Beaches constitute an important natural resource, not only for the continental States of the Greater Caribbean but also for the Small Island Developing States (Juanes et al., 2003 and Cepal, 2020). In these islands, the lack of resources such as fuel and minerals, and the scarce availability of freshwater resources, make tourist exploitation of the coasts a fundamental economic activity (Pérez and Milanés 2020). It is precisely due to this archipelago and islet setting that beaches are directly influenced by all the social and economic activity of different nations, which constitutes an additional environmental risk factor that requires special attention where “the planning and management of coastal resources essentially is synonymous with the planning and management of national resources” (Juanes et al., 2003 p.3). These beaches host tourists from around world as well as the pollution from remote places that washes ashore.

There is an almost generalized opinion that closing beaches, as one of the immediate pandemic measures to control COVID-19, has had positive results for beaches, because natural vegetation has been restored, and birds, fishes, as well as other species, have returned to their environment (Soto et al., 2021; Bates et al., 2020). However, it is also true that COVID-19 lockdowns mean a near absence of tourist activity, creating negative economic impacts around the world (Ehrenberg et al., 2021). This is particularly serious for small island states since most of them depend on “sun, sea and sand tourism” (Eyawo et al., 2021).

Cuba is an island nation that suffers from the impact of COVID-19. It benefits from an integrated government strategy based on a solid health system and public policies, and free and universal access to health and social protection (Díaz, 2020, CUBADEBATE, 2020; ACN, 2020, Prensa Latina, 2020a,b; Granma, 2020). Despite a difficult economic context aggravated by a decades-long financial blockade imposed by the United States government (Gerhartzet al. 2016; ONU, 2019a, ONU, 2019b; MINREX, 2019), the territory has used a very effective plan for combating COVID-19, recognized internationally (Oxford Stringency Index for Cuba, 2020 OPS, 2020, Prensa Latina, 2020a,b). This is evident in the low COVID-19 death rate in Cuba of 20 per million compared to that for the US of 1383 per million as of 5 February 2021(Statisa, 2021).

The strategic plan for Cuba, from the first cases of COVID 19 in the island, established three phases: Phase 1: Pre-epidemic, Phase 2: limited native transmission and, Phase 3 epidemic stage. Among the measures of this plan is beach closure to guarantee isolation and physical distancing and avoid contagion in the population. However, little has been discussed in the scientific and management field in Cuba regarding how to organize the beaches after Covid-19. To wit, a group of Cuban experts belonging to IANP (Ibero American Network Proplayas, www.proplayas.org), discussed and evaluated the challenges of COVID 19 for the archipelago, posing the research question: How can some recommendations be designed in sun, sea, and sand tourism-dependent- insular countries to face “the COVID 19 new normality?” In this paper, we develop a 4-stage response to the charge issued by IANP. The purpose of the study is to execute a formal analysis of appropriate information that will allow us to articulate a comprehensive list of recommendations for effective beach management in the post-COVID era for Cuba and other island nations.

2. Material and methods

To obtain the best scientific information for structuring recommendations for effective coastal and beach management we undertook a two-prong approach. This combined a quantitative structured survey of the literature with qualitative data from photographs, social networks, and the views of experts in the field. The study took place between March and October of 2020. The methodological framework of the research was developed in stages and structured by different variables and categories of analysis, (See Fig. 2 ). These are: Stage 1. Systematization of the information published on the coastal planning and management of beaches in the Covid-19 lockdown (scientific articles, news on social networks, and digital and written press). Stage 2: Identification of good and bad practices and actions of beach management and coastal planning associated with protection measures against COVID in different countries. Stage 3: Determination, according to the criteria of experts, of the actions and recommendations for beach management and planning based on lessons learned from other contexts with better possibilities for success in island countries. Stage 4: Validation of the recommendations for the regulating and management of beaches in the post-Covid-19 stage in an island nation (Cuba). The specific details of each stage are described in the following sections.

Fig. 2.

Methodological framework of the present study.

2.1. Review of periodical publications

News published in newspapers and social networks such as Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, Youtube, LinkedIn, platforms such as @Bandera.Azul ADEAC, @EnDefensaDeLasPlayasPublicas; @PlayaLimpiaPeru; as well as non-governmental organization (NGO), @RProplayas, among others, were reviewed in the development of the research.

We searched information pertaining to three variables: 1) actions related to beach management within the measures of COVID-19 lockdown in insular states dependent on tourism; 2) behaviors of populations affected by management measures; 3) examples of good practices such as hygiene and physical distancing measures for beach management.

We investigated practices and actions at the international level to identify important variables in beach planning in relation to COVID-19. Identifying articles and publications that addressed these aspects informed the design of the methodological framework of the inquiry. Six variables warranted analysis: 1) Equipment and facilities, 2) Biosafety and hygiene measures, 3) Reorganization of spaces, 4) Beach access, 5) Level of occupancy and beach monitoring, 6) Signage (see Fig. 2). These variables are directly related to protection measures against COVID-19, regardless of the location and conditions of the management practice. The variables expressed in management behaviours vary according to the socioeconomic, environmental, cultural characteristics of the local area in which they are implemented.

The content analysis technique was applied to the official reports and press publications consulted, notably (Hsieh and Shannon, 2005): The Herald (www.elheraldo.co/atlantico), and Time Magazine (www.elespanol.com/organismos/revista_time), El País (www.elpais.com.co/), Colombia, Telemundo (https://www.telemundo51.com/) Mexico, Granma, (www.granma.cu), and Cubadebate,(www.cubadebate.cu), Cuba, El Economista (www.eleconomista.es/), Spain, The Sidney morning Herald ( www.smh.com.au/ ), Australia, La Capital (www.lacapitalmdp.com/), Argentina, among others. At the same time, metric information was obtained from the Cuban observatory for the coronavirus and from official publications of the Cuban Ministry of Health (https://salud.msp.gob.cu/) as well as scientific observatories https://temas.sld.cu/coronavirus/covid-19/observatorio-cientifico/) to obtain statistics and behavior for COVID-19 in Cuba. We also used data and metrics obtained in the Coronavirus metric observatory of the University of Pinar del Rio.

2.2. Scientific databases review

To obtain reliable information and to verify the few scientific publications on this subject, the literature published in Scopus and the Science databases were analyzed: The following three search equations were generated on the subject: 1) “land-use planning” OR “territorial ordering” OR “beach management” AND Covid*; 2) “beach management” OR “territorial planning” OR “marine spatial planning” AND Covid* and, 3) “land-use planning” OR “beach management” OR “territorial planning” OR “territorial ordering” AND Covid* OR pandemic.

The first search equation only generated two articles published in Scopus (Zielinski and Botero, 2020; Lal et al., 2020) with only the first one pertinent to our study. The second equation produced the same findings. Search of the Science website, yielded about 55,000 results. However, many of these articles were not relevant since they associated COVID-19 with health issues, tracking and tracing tourists and not focusing on the planning and management of beaches. In this case, some articles published in the International Journal of E-Planning Research (Graziano, 2021; Doyle et al., 2021) stood out for analyzing post-COVID city planning scenarios, with a special emphasis on Italy and without specifically considering beaches.

In the case of Cuba, no scientific articles were found about planning and managing beaches during the pandemic by COVID-19. Additionally, found coastal management protocols didn't include sanitary hygiene or biosecurity issues for the prevention of contagion of diseases in the mentioned spaces. Therefore, the analysis done in this article is the first on these themes.

2.3. Selection of experts and survey application

To generate informed opinion on the impact of COVID-19 we surveyed experts in the fields of coastal planning and beach management during the third week of August until October 17, 2020. We used the structured questionnaire technique. The questionnaire was divided into four blocks with 17 questions. The electronic tool QuestionPro® www.questionpro.com was used in the design of the survey. The survey was applied in Spanish. The link was distributed in a personalized way via email and WhatsApp ©.

We applied inferential statistics to determine the sample size and the minimum number of experts, (Ostle, 2012). This constitutes an effective technique for calculating a sample of experts in a previously established universe. Following the qualitative methodology of (Sampieri 2014), a trial sampling was applied. Experts were selected following the authors' criteria based on knowledge of the target population. We considered the qualitative variables related to a) the level of knowledge and expertise that individuals have on issues related to beach planning, zoning, and management; b) the years of work on the subject and 3) the quality and quantity of scientific publications of the experts on the subject. This yielded 60 national and international experts. Valid sample size criteria required a minimum of 48 experts responding of the 60 considered as a universe.

The selected experts are part of three major international knowledge networks. The first one known by its acronym PROPLAYAS is made up of a solid group of representatives from academia, civil society, scientists, activists, officials, and businessmen, who work only on beach issues (www.proplayas.org). The second network is called IBERMAR. It has been active since 2008. Its members are experts in Integrated Coastal Zone Management (ICZM) from a complex and integrated perspective (www.gestioncostera.es/ibermar). We also included the Stephen Olsen (ICZM International Chair). The network constitutes an initiative between Ibero-American Universities interested in the theoretical-methodological development of coastal governance and the four orders (Enabling framework, Changes in behavior, Practice results, and benefits, Sustainable Development) of the ICZM (UNEP/MAP/PAP 2015). The experts from this network work on the systematization of learning from cases and experiences of coastal and beach management at the local level and their interrelation with other levels.

Despite the unprecedented pandemic, these experts carry out their activities under the ICZM perspective. This approach guides coastal management according to the precautionary principle. Therefore, new scientific findings to be included can be applied for coastal management in this case, using variables, such as biosecurity and sanitary hygiene, physical distancing, beach zoning, facilities, and monitoring, among others. The experts do not create the policy for confronting COVID-19, but they are responsible for implementing the measures that each country's policy dictates.

Given the interest in delving into the measures adopted for the management and regulating of beaches in the island states, with special emphasis on the case of Cuba, a subset of 36 Cuban specialists were selected from the universe of experts. These include 19 professionals linked to two of the three scientific nodes of the Proplayas de Cuba Network. The Cuban nodes consulted were: 1) Node 14 and 2) Node 44.

After identifying the most significant variables using the international literature, we developed a questionnaire for the selected experts. We chose the recommendations based upon the scores given in their responses.

To test the recommendations made by experts, it was also considered pertinent to include Cuban decision-makers who, at the time of the pandemic, held responsibilities associated with regulating the beaches. Therefore, the survey was also applied to a large group of experts representing the Institute of Physical Planning, the Ministry of Science, Technology, and the Environment (www.citma.gob.cu) and their provincial agencies. The survey had response effectiveness of 97%. The average time for completing the questionnaire was 16 min. Of all participants in the survey, 68% were women and 32% men. The total of respondents, 93% were university graduates. The sample taken was multidisciplinary, having representation of the social, natural, technical, and environmental sciences. Most (88%) of the participants have a working or research relationship with issues concerning beach and/or coastal zone planning and management. Survey was based on the opinions of 62% Cuban experts and 38% International experts.

Of the experts, 36% have the category of professor and 31% researchers. In the case of the Cuban experts, there was also representation of authorities from three universities (Oriente, Matanzas and Las Villas) as well as from the research centers (Center for Environmental Studies Sp. CEA and Eastern Center of Ecosystems and Biodiversity Sp. BIOECO). In the case of international experts, universities from Colombia, Puerto Rico, Mexico, Uruguay, Italy, and Argentina were represented. The Network with the highest representation in the research was Proplayas with 60% of experts.

2.4. Case study of nation of islands

Given the particularities described above regarding Caribbean insular states and especially Cuba, it was considered appropriate to be the case study analyzed. The final purpose of this selection is to visualize and project into the immediate future, the recommendations for beach planning and coastal management proposed during the pandemic period, the new normality, and in post-pandemic scenarios. Finally, Cuba more than most island nations features a highly developed infrastructure that links science, policy, social need, concern for the environment, education, and economic development.

Cuba is a nation of islands. The Cuban Archipelago is contained in the Caribbean basin and is made up of more than 1600 islands, islets, and cays, of which the island of Cuba is the largest. The plan to deal with Covid-19 in Cuba has among its priorities the strengthening of national epidemiological surveillance for early identification of cases and their timely treatment (OPS, 2020). Beach closure in the confinement period and the reinforcement of sanitary organizational and hygienic measures in the plan's later stages were effective in avoiding the spread of the disease (Prensa Latina, 2020a,b; Granma, 2020). However, despite these social advances, there is no visualization of a beach management model in the country that guarantees such measures over time, or once the crisis is over. The implementation of functional zoning and beach management measures in Cuba will prove to be very complex.

Flexibility in the beach opening measures allowed Cubans to return to them after their confinement. However, the influx of people on these beaches has not been comparable to other countries in Latin America and the Caribbean, due to the concern of the health authorities that infections could increase (Rodríguez, 2020). This could occur through the social behavior of Cubans in these spaces, characterized by group games, drinking from the same glass or bottle, and not using protective measures, among others. This sociocultural behavior is widespread in many Latin American countries.

In Cuba, the existence of well-managed beaches by tourist companies such as in Varadero and those of the keys in the north of the Island, among others (Fig. 3 -A-B), puts them in better position to implement an effective plan in the post-COVID-19 opening stage. These beaches have strong infrastructure, materials, and financial resources, generated by their own tourist activity. Therefore, they can adopt higher standards in the quality of their services. The second and most common scenario of the urban and remote Cuban beaches of the Southeast is very different (Fig. 3-C-D). These beaches, which are heavily populated and hugely enjoyed by the local population, lack equipment, infrastructure, and furniture, meaning they will require different actions regarding management and regulatory schemes.

Fig. 3.

(a) (b) Photos of the beaches in the north of Cuba with optimal land use-planning (Source; Cabrera, 2020). (c) (d) Current photos in two urban beaches named La Estrella and Siboney in Santiago de Cuba. It shows a lack of furniture and poor land-use planning (Source: Velázquez, 2020).

The marine-coastal zone of the Cuban archipelago constitutes a unique class resource. Its coastal planning and ICZM have a strategic nature, constituting a magnificent opportunity and a great challenge for its sustainable development. In this context, tourism activity in Cuba has been growing and has its greatest expression in tourism associated with beaches. Before COVID-19, Cuba received more than 4 million foreign tourists annually (Diario, 6124, 2021). The main motivations for the arrival of tourists to Cuba are its beaches, its cultural heritage, wealth, history, people, and security (Mintur, 2021). We used these scenarios in conjunction with the results of literature and expert surveys to model recommendations. SketchUp, Lumion, Photoshop and, CorelDRAW Graphics Suite 2020 software helped illustrate the model.

3. Results and discussion

This section is presented in three-steps. We combine the presentation of results with their interpretation and discussion of attendant implications. In this research, we use two important terms “beach management” and “beach planning". Beach management can be considered as a subset of coastal zone management (Foreword p. Xix, wrote by Finkl, 2009 in Williams and Micallef, 2009). Some authors use the term “beach management” when referring to aspects related to the evaluation of the beach at a landscape scale, recreational use, ecosystem conservation, studies of environmental degradation, identification of conflicts, recreational opportunities, tourism and/or exploitation, scenario analysis to design beach management strategies, and more (Villares et al., 2006; Cervantes et al., 2008; Amyot and Grant, 2014).

In this research, “beach planning” refers to measures typical of the planning, zoning, and land and sea uses of the beach. These measures and actions were compared between countries to design recommendations that contribute to decision-making processes for better information and adaptive management services that the new model of beaches must assume in the face of the COVID-19 pandemic.

3.1. The practices and actions published in the literature

Experiences of more developed countries (APA 2020; Garófano, 2020; Muñoz, 2020; Info Praia, 2020a, Info Praia, 2020b Medio ambiente, 2020a, Medio ambiente, 2020b; IMPLAN. 2020) differ in content and scope from those of less developed countries (El Cacho, 2020; Granma, 2020; MondoBalneare.com; Resolución 1538 del 2020). Those with the greatest economic development show greater use of technologies based on management (camera systems, digital monitoring signals, early warning systems, digital signage, traffic lights among others), as well as in the use of materials to implement equipment for physical distancing on the beaches. Practices and actions of less developed countries with fewer economic resources make use of indigenous materials and low-cost local solutions (Milanes et al., 2020; Pereira et al., 2019).

The initiator of management practices varies in accordance with economic considerations. In coastal zones with consolidated tourism, tourism companies, and private businesses are those directly engaged in economic activity related to beaches and therefore play a more active role in structuring policy and management (Garófano, 2020; APA 2020; Gorrey, 2020; Medio ambiente 2020 a,b; IMPLAN, 2020). The local population, volunteers and local governments dominate management in areas with less tourism activity (Zuñiga 2020; Resolución 1538 del 2020; La Capital, 2020; El Cacho, 2020).

Initially, the most relevant examples observed in the international literature regarding beach planning and coastal management during the pandemic were described in Appendix 1. These practices and actions were the support for designing of the recommendations and have been classified into 6 variables. A treatment of the 6 variables follows.

3.1.1. Practices and actions regarding equipment and facilities

Beachgoers complain about the absence of beach huts is (Milanes et al., 2020; www.elpais.com). Many visitors consider such structures a necessity, particularly in the COVID-19 era. The beach huts are in high demand in countries like Spain, Italy, and Cuba. However, in the insular country, beach huts are restricted to the service area above the beach proper Decree Law 212 (GORC, 2000; Milanes et al., 2019; Batista, 2018a,b).

In Spain, beachgoers ignored the wooden structures installed to maintain social distance between groups of different families (Xavi, 2020). Visitors instead crowd the shore without making use of these demarcated spaces (see Fig. 4 a and b). But the action, which could be classified as “a good practice,” has been characterized as “negative” by some authors (Milanes et al., 2020; Botero et al., 2017; Botero et al., 2020a). The main negative problem is the affectation of these structures on the landscape of the beach. Other similar practices include the design of spaces with social distancing rules. The Fig. 4 c-d shows the minimum distances of 1.5 m between people and 3 m between awnings applied in Portugal in the CoVID-19 era.

Fig. 4.

(a) (b) Silgar Beach, Sanxenxo. The first weekend of July 2020. The bathers ignore the plots installed by the City Council to prevent the spread of coronavirus and settle in other areas of the beach. (Source: Freixes, 2020; Twitter @ JavierG59076934). (c) (d) California Beach, Sesimbra, Portugal c. Date: photo taken on August 14, 2019, without closure by COVID-19 d: photo taken on August 16, 2020, with closure by COVID-19 (Source: courtesy of Pereira da Silva, 2019; 2020).

3.1.2. Practices and actions regarding biosafety and hygiene measures

The proliferation of personal protective equipment deployed during the Covid-19 epidemic means the accumulation of discarded masks and gloves on beaches. They wash ashore from the sea, are left behind by visitors, and are carried in by the wind and nest-building animals (Milanes et al., 2020). Gloves, face masks, among other solid waste are present and poorly managed in island states such as Hong Kong and elsewhere (El Cacho 2020; Reuters, 2020). In Mexico, the Federal Maritime Terrestrial Zone (Sp. Zofemat) applied the sanitary protocol “Everyone against Covid 19″, which includes social distancing and groups of no more than five people. To enter the beaches, it is necessary to use a mask and antibacterial gel. Also prohibited are alcoholic beverages and contact sports (www.excelsior.com.mx). Similar measures were also tested in Pozos Colorados, Santa Marta (see Fig. 5 ).

Fig. 5.

(a) Beach cleaning modes (b) (c) Distance between facilities during COVID-19. Beach “Pozos Colorados”, Colombia (Sourse photos taken by Milanes et al., 2020).

3.1.3. Reports on practices and actions regarding beach acces and reopenings

Attempts to reopen beaches in an organized way that includes protective measures are sometimes successful, as for the cities of San Antero and Bajo Sinu in Córdoba, Colombia (www.elheraldo.co). Nevertheless, in other regions such as Buenaventura and Puerto Colombia, return to the beaches meant unruly crowds that violated biosafety standards (www.lafm.com.co).

Columbia restricted beachgoing to between the hours of 9 a.m. and 5 pm to take advantage of the sterilizing effect of intense solar radiation (www.ideam.gov.co; Resolution 1538 of 2020). They also issued ID numbers for beach access. However, the numbering scheme failed to account for families. Members of the same family often received numbers incompatible with simultaneous attendance. (www.eltiempo.com; Resolution 1538 of 2020. Mexico took a more lenient approach, restricting beach access in Acapulco to the hours between 7 a.m. and 7 p.m. (Government of Mexico 2020a.b).

3.1.4. Practices and actions regarding level of occupancy and beach monitoring

Beach Apps such as Info Praia, 2020a, Info Praia, 2020b and “Nik Hondartzak” (Medio Ambiente 2020 a, b.), are highly valued to analyze occupancy level and monitoring of beaches. Both Apps allow users to check occupancy levels prior to arrival. The Nik Hondartzak App uses the traffic light system and sends information to beach managers using images. This is a free App that is updated every 15 min, and for regulating the beach, it establishes physical distancing under the geographical criteria of each beach. However, both applications are limited to Gipuzkoa and Portuguese beaches at this time. Similar systems could be developed for Cuba and other insular nations.

3.1.5. Practices and actions regarding reorganization of spaces, and signage

Practices for reorganizing beaches during Covid times include posted norms on websites and platforms (APA 2020; Mar à Vista, 2020), and traffic lightmaps (IMPLAN, 2020). However, some of these tools still need improvements to show reliable data and other information options, such as their application on a greater number of beaches. Some actions, such as those used in APA (2020); Info Praia, 2020b, Info Praia, 2020a; Medio Ambiente (2020a,b) and, Garófano, 2020, cannot be used in underdeveloped and blocked countries, like Cuba, due to limited access to 4G telephony. The high costs for use of mobile phones are another limitation in Cuba. However, despite financial constraints, these actions lead to a change in the Cuban beach management model, contributing also to the design of smart beaches and cities with the potential given by technology (Ravelo and Milanes, 2018; Graziano, 2021).

An excellent action initiated by the academy is Mar à Vista (Mar à Vista, 2020), designed as a university extension project between the Department of Geography and the Marine Geography Laboratory of the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro. The initiative is powered by a network of users from various social categories, such as bathers, surfers, and vendors. They monitor currents, wave heights, load capacity, pollution, and beach morphology. Its application has been strengthened during the pandemic, using a data collection form called Vicon SAGA mobile, which is very similar to KoBoCollect. Collaborators include the Blue Fag of Praia do Peró (a citizen advocacy organization for the ocean) and the Prainha Municipal Park. Despite its local impact, it is evident that this type of good practice needs to be disseminated more to the scientific community and the Brazilian population in general to replicate its use. This would also promote the emerging movement of citizen scientists (Bonney et al., 2014).

Reservation of plots through web platforms for choosing specific times and locations on beaches (www.benidormbeachsafety.es), as well as the sale of a kit to build “anti-coronavirus plots” (www.antena3. com), are other good measures. Some of the proposed actions, as well as the strategies developed in different countries to deal with Covid-19, tend to be short-term local solutions and are not evidence-based policies (Kreiner and Ram, 2020).

3.2. Recommendations for coastal planning and beach management during the pandemic and in a post-pandemic scenario

The crisis caused by the pandemic highlights the interconnection between nature and the vulnerabilities of society. COVID-19 provides an ideal opportunity to demonstrate how changes in beach planning and management are possible. The rapid changes produced by this pandemic sparked the debate on how to build more resilient societies and the role of planning to promote a fair and sustainable recovery (Doyle et al., 2021). The analysis and assessment of international practices in the management of beaches during the pandemic, as well as the interpretation of two chapters (Milanés et al., 2020; Bianchi et al., 2020) published by (Botero et al., 2020a), allows the authors to propose 27 recommendations (Table 1 ).

Table 1.

Recommendations for the planning and management of beaches.

| Category for beach management and coastal planning | Recommendations |

|---|---|

| Instruments of coastal planning |

|

| |

| |

| |

| |

| Use of space |

|

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| Beach access |

|

| Beach occupancy |

|

| |

| Hours of beach use by the visitors |

|

| Hygiene and biosafety on the beach |

|

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| Signage on beaches |

|

|

Before proceeding to endorse the recommendations, information was obtained on the effectiveness of the government measures to protect the population associated with beach closures and their impact on these ecosystems. At the same time, data on the transformations observed in these ecosystems, as well as other aspects related to the actions and innovations designed in the period of closure, were supported by the experts.

The experts agree with the closure of beaches, within the plan of measures to combat Covid-19. In this period, experts observed significant changes in these ecosystems. The most significant changes noted by the experts and percent who indicated such are as follows: Decrease in solid waste pollution (18%), decrease in population and tourists who attend the beaches for fear of contagion (14%), restoration of the beach's natural vegetation (13%), return of birds to the beach environment (12%), the appearance of fish in the bathing area (11%). The data obtained coincide with other authors who record positive modifications in coastal ecosystems and beaches, due to the absence or reduction of humans in these places (Mukherjee et al., 2020; Zambrano-Monserrate et al., 2020; Zielinski and Botero, 2020).

Before the appearance of Covid-19, experts assessed the management and coastal planning of beach ecosystems as being between fair 47% and good 37%. They recommended that in the post-pandemic period the following aspects should be reviewed: a) Normative, zoning, and coastal planning frameworks regarding beach use (15%), b) Coastal policy related to human and ecosystem health (14%), c) Coastal marine planning of beaches (14%), d) Communication and promotional policies for these spaces (12%).

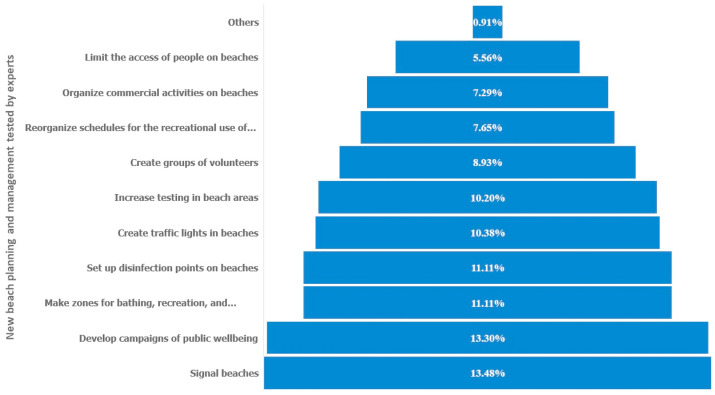

According to the experts, the new post-pandemic scenario requires new measures related to coastal planning in beach management. The experts considered the following actions: a) Signposting beaches with the allowed carrying capacity to avoid contagion (13%), b) Developing a public welfare campaign for the education of people post-COVID-19 (13%), c) Zoning the bathing area, recreational and sunbathing zones (11%), d) Setting disinfection points on the beaches (11%), d) Traffic lights that give information to bathers on the load level on the beach (10%), Increase testing in the beach area (10%) (Fig. 6 ).

Fig. 6.

Beach planning and management measures to be applied in the post-COVID-19 era. The bars refer to management measures tested and reported by experts. Caption: Organize commercial activities on beaches diversifying the point of sale (7.29%); Create groups of volunteers to organize recreational activities on beaches that comply with social distancing (8.93%), Create traffic lights in beaches that give information to bathers about load levels in real-time (10.38%), Develop campaigns of public wellbeing to educate people post-COVID (13,30%), Signal beaches with the admitted load capacity to avoid contagions (13,48%).

Isolation and physical distancing measures to avoid contagion demand, according to the experts, new actions to organize and manage beaches previously not considered for these spaces. Some of the proposals refer to (with % of experts recommending such): the use of traffic lights to indicate beach occupancy rates (27%), the use of surveillance videos using cameras with 4G mobile phone connectivity (20%), regulating, and marking beaches via traffic light colors regarding strong currents (19%), restricting beach spaces using ropes for family groups (17%).

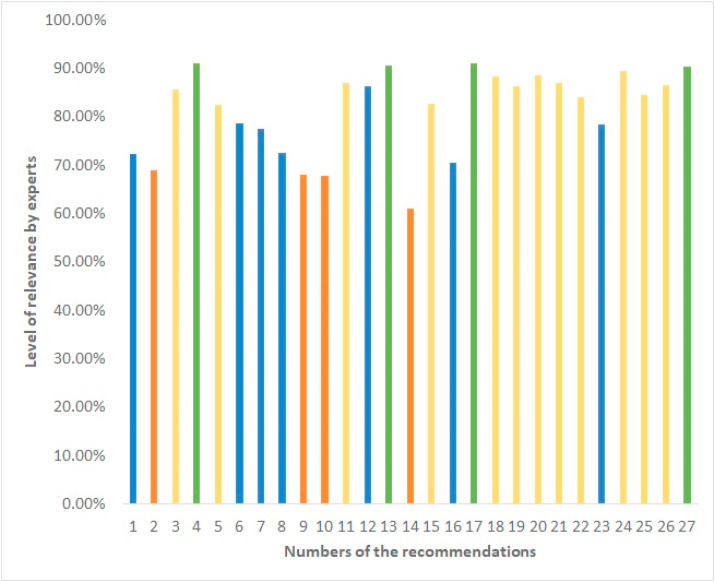

Most of the experts accepted all (61%) while (91%) accept some of the 27 recommendations for the management and coastal planning of beaches in the post-COVID-19 stage (Fig. 7 ).

Fig. 7.

Percentage of recommendations accepted according to experts. Red columns: recommendations with percentages less than 70% accepting a recommendation; blue columns: accepted a recommendation between 70-80%, yellow columns: accepted a recommendation between 80 and 90%; green columns: accepted a recommendation over 90%. The numbers along the X-axis refer to the recommendations presented in Table 1. For example, 70%–80% of the experts accepted the first recommendation in the table.

The proposed recommendations provide an opportunity to reconsider the necessary transformation of the global beach tourism system improving planning and management capacity better aligned with sustainable development goals as mentioned Lancet Public Health (2020). The recommendations could also be incorporated into national tourism strategies during the Covid-19 pandemic (Kreiner and Ram 2020). This will mean better planning and management of the visitors and tourism in the beach context (Gössling2020).

The experts also evaluated the applicability of these recommendations in their area of work or scientific research, considering the 27 recommendations appropriate and useful for post-pandemic beach management in their coastal environments. This allows a more detailed case study analysis for insular states, and in particular the case of Cuba.

3.3. Applicability of the recommendations at insular states: Cuba as study case

Despite progress in some Caribbean island states, the paradox is evident that, with beaches being the fundamental axis of tourist activity and a deep-rooted cultural-recreational tradition for the local population, these venues experienced a general physical-natural and environmental deterioration in recent years, reducing their commercialization potential (Cabrera et al., 2019a,b; Juanes et al., 2003).

In the Caribbean islands, lack of economic resources, such as fuel and minerals, and scarce availability of freshwater resources, cause several health problems for communities at risk (Perez and Milanés 2020; Milanes et al., 2020; Juanes et al., 2003; (Batista, 2018a,b). Sun, sea, and sand tourism become a fundamental economic activity (Botero et al., 2020b, Botero et al., 2020a).

Caribbean insular states have a set of local characteristics in which the recommendations proposed are especially suitable for them, among which it is worth highlighting: a) High dependence on tourist activity on beaches and coastal zones b) Frequent excesses in the density of users, c) Failure to comply with proper functional zoning, which indicates serious deficiencies in beach planning and management due to tourist uses, d) Several erosion processes and environmental degradation with high occupancy by different types of facilities, buildings, and infrastructures, e) Lack of an integrated vision of beach and coastal zone management, for addressing in a holistic way a set of problems and key issues that currently affect these sites, as well as the human activities developed in them, f) Several limitations for funding and technical resource-materials to implement response measures to the aforementioned problems. Especially under the new conditions imposed by the Covid 19 pandemic.

Management and coastal planning for Cuban urban beaches focused on erosion, pollution, and loss of resources rather than infrastructure, facilities, and coastal landscape value (Fig. 8 ). The economic-financial approach in most of the urban and tourist beaches in the southeastern region of Cuba predominates over environmental sustainability (Cabrera et al., 2009 a.b.).

Fig. 8.

(a). Abandoned structures and dilapidated umbrellas. (b). Users must create their own facilities on beaches to protect themselves from the sun. (c). Presence of transportation equipment on the beach dune, such as motorcycles, due to the absence of beach inspectors (Source: Velázquez, 2020; Infante, 2020).

In the current context, where the unexpected and abrupt outbreak of the pandemic associated with COVID-19 occurs, the profound economic repercussions for coastal and insular states of the Caribbean are evident, not only from the epidemiological perspective but also from the economic, social, and environmental dimensions. The pandemic reveals the absence of measures in coastal management and beach planning of insular states focused on the risks and threats associated with climate change. There is no complex and preventive vision for these issues associated with risks of a biological origin, which, in spatial and temporal terms, have their own characteristics and requires their own responses.

More control over anthropogenic and epidemiological alterations of coasts and beaches is required. Before, and during Covid-19 Cuban beaches suffered from constructions on the coastline, hard and damaging infrastructure, pollution of water and sand. These reduce biodiversity and the sustainable bearing capacity. This entails, as 90% of the experts surveyed responded, moving towards new policies and regulatory frameworks for planning and management in the post-pandemic phase.

Of the experts surveyed, 76% point out the need to create and put into operation committees or other forms of collective bodies for the management and regulation of beaches. This speaks to the importance of entities such as the Local Committees for the Organization of Beaches (CLOP in Spanish) in force in Colombia (Decreto, 1766 of 2013), known in Mexico as Clean Beaches Committees (SEMARNAT, 2020), and in Cuba as MIZC-GIP Coordination Boards, (Juanes et al., 2003; Cabrera et al., 2009). This similar organization, under name of Beach Management Bodies (Órganos de Gestión de playas -OGP in Spanish), has also been proposed in Spain since the 90s by Yepes et al. (1999).

The practice of CLOP has been tried with few effective results in island states such as Haiti (Juanes et al., 2003); the Dominican Republic (Cabrera et al., 2009), and Puerto Rico. For the last island, a project of law and a norm were formulated (Personal communication Barreto, 2020). Both are still without approval.

Encouragingly, in Cuba these bodies exist for the beaches of Varadero, Habana del Este, and some areas under the island's integrated coastal management regime (Cabrera et al., 2019; Lozoya et al., 2019). However, despite some successes, most of the Cuba's beaches do not have these structures in place. The greatest absence of these committees can be seen for the beaches located in the eastern and central regions of the country. Thus, recommendations must quickly be extended as an effective mechanism of coordination and dialogue for beach planning and organizing actions during the pandemic.

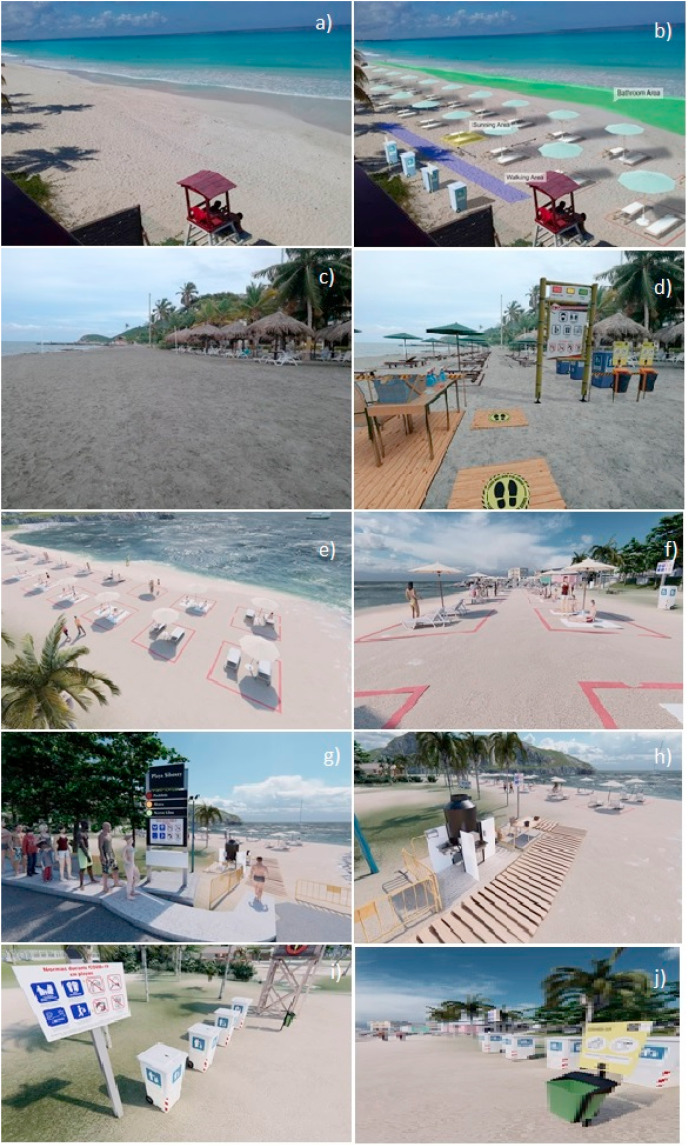

Also widely supported by the experts surveyed, with 81% for the post-pandemic phase, was the need to apply rigorous zoning for beaches, establishing active areas, rest areas, and services for bathers, requiring a control in the density of users to avoid crowding and risks of contagion. The need to incorporate traffic light access in relation to the load capacity of the beach and implement biosafety standards at its access points was raised. The emphasis by 81% of those surveyed stands out regarding the need for signage measures as both informative and regulatory, and above all, for education regarding the behavior of visitors and waste collection derived from the pandemic. Fig. 9 a–j illustrate those recommendations that garnered 70 or more percent of favorable consideration from the experts. It was modeled using the software 3D, Sketchup.

Fig. 9.

(a) Varadero Beach, Cuba, without zoning and facilities located on the beach before and during COVID-19 lockdown (Source: Cabrera, 2020). (b) The same beach with proposed zoning in a post-pandemic era. (c) Baconao Beach in Santiago de Cuba without coastal planning in COVID-19 lockdown (Source: Milanes 2020). (d) The same beach with organizational, biosecurity, and sanitary measures to avoid contagion of COVID-19. (e–j). Modelling carried out for Siboney beach in Santiago de Cuba, showing how access to this beach should be with biosecurity measures as well as, for the management and classification of waste derived from the pandemic.

Considering the analysis from the responses, in a general sense, the experts suggest that visual changes or phenosystemic signals should not be trusted absolutely. This is due to there being “invisible” structural and functional aspects. Of those surveyed, 83% insist on the need to record changes and monitor each physical, chemical, and biological variable closely to understand deeply the ecological and environmental panorama left behind by the pandemic. This should be the starting baseline to learn and improve beach planning and management in the post-pandemic phase.

Some of the recommendations are already being tested in Cuba by a group of competent institutions and entities, headed by the Directorates of Physical Planning (Sp. IPF) and. Science, Technology, and Environment (Sp. CITMA) in coordination with local government authorities and social organizations. Recommendations put forward can be extrapolated to other insular contexts depending on policies and capacities of the response of the corresponding governments, as well as of the human and financial resources.

Regardless of the validity of these recommendations, there is the full conviction that the management of beaches and coasts continues to be a conceptual-methodological model under construction and development, which must be based on an ecosystem approach. Feedback on implementation experiences is needed. Systems of monitoring and periodic assessments of beaches increasingly play a decisive role.

The results obtained might lead to future research, using additional techniques to examine other aspects of beach management and planning. The main limitation of the present research work is the fact that the COVID-19 pandemic is still a recent threat. Therefore, relevant published research about that topic is limited, (Severyn & Botero, 2020). This suggests the timeliness of this research.

3.4. Operational details and relevant factors to consider for beach planning and management

For environmental sustainability managers of the beaches should give importance to a set of factors and operational variables that allow progress for solutions to remedy erosion, pollution, and habitat loss. This must be done with a holistic approach in the context of tourism and sustainable economic development.

Recommendations include: 1) Prohibiting the construction of buildings on the coastline, as well as the use of hard works that cause erosion, 2) To control the discharge of different types of waste, which translate into high levels of pollution of water, sand and air, to avoid affecting native vegetation and biodiversity, 3) To apply rigorous zoning on the beaches, clearly establishing the active, rest, and service areas, 4) To establish measures to control the density of users, in order to avoid crowds and dangers of contagion, ensuring respect for the carrying capacity of the beach and implementing biosecurity standards at its entrances, 5)To prioritize specific signalling actions, both informative and regulatory, and above all educational activities regarding visitor behaviours, 6) To work together to establish a permanent monitoring system, periodically evaluating the results, and, finally, 7) To review critically new policies and regulatory frameworks for ordering and managing beaches and coasts in the post-pandemic phase to advance in its improvement.

This research proposes operational aspects for beach managers, associated with rethinking seven categories into which the 27 recommendations provided were divided. These recommendations respond to the economic and cultural conditions of each island region, and of each beach in a more specific way. The results and recommendations of this work have a high theoretical-methodological implication for beach and/or coastal planning and management. Working with experts who are directly involved in these issues, ensures the objectivity and possible implementation of the 27 proposed recommendations.

4. Conclusions

COVID-19 showed the need to integrate physical distancing, biosecurity and sanitary hygiene measures into beach planning and management programs. Diversity of management practices, analyzed by the authors in different contexts around the world revealed that the relationship of COVID-19 with beach management is clearly expressed in six variables: equipment and facilities, biosafety and hygiene measures, reorganization of spaces, beach access, level of occupancy and beach monitoring, and signage. Practices observed in developed countries include responses with greater use of technologies, while those in less developed countries offer lower-cost solutions.

The 27 recommendations provided in this study are valid and very operational for beach managers. The recommendations proposed were grouped into seven categories 1) Instruments of coastal planning, 2) Use of space, 3) Beach access, 4) Beach occupancy, 5) Hours of beach use by the visitors, 6) Hygiene and biosafety on the beach, and 7) Signage on beaches. These must be adjusted to the political, economic, environmental, and cultural conditions of its management scope, according to the strategies and conditions of each island state to face the pandemic.

Some existing Apps for beaches can be relevant for coastal planning and beach management. New Apps need to be developed for insular nations. Forty-three practices and/or actions for planning and management of beaches during COVID-19 have been identified. While twelve were taken for biosecurity and hygiene measures, nine have been considered for occupancy levels, beach monitoring, and space reorganization. Finally, six of them were directed to the categories of equipment and furniture, five for beach access, and two for signage.

It has been difficult to define a universal confinement period, a post-pandemic scenario, and restrictions to beach access. In most island countries, as in the case of Puerto Rico, and Cozumel in Mexico, the beaches have opened and closed on several occasions due to new outbreaks. The situation of Cuba has been different. At the most famous tourist beaches in Cuba, some recommendations are being implemented. As the largest island of the Caribbean, Cuba has particular characteristics and represents more than 900 Caribbean region islands. The 27 recommendations provide answers to operational aspects of coastal management and are valid for the islands of the Caribbean. The proposed recommendations include measures for the protection and confrontation of the pandemic universally accepted by the WHO, with the particularities of the activities and uses that take place in coastal zones.

Funding

Partial financial support for this research was provided to the first authors by Universidad de la Costa [grant numbers INV.1106-01-002-15] by the project named “Cultural practices and environmental certification of beaches: a contribution for the sustainable development in the insular states. Other funding were provided by the Cuban projects named in Spanish “Tarea Vida”, Code.10523, and "Monitoreo y manejo integrado de ecosistemas costeros ante el cambio climático en la región oriental de Cuba. (ECOS)", Code. PS223LH001-016. Both coordinated by Universidad de Oriente, Cuba.

Author contributions

CBM conceived the article; CBM, OP, and JAC designed, applicated and analyzed the results of the survey; CBM, OP, JAC, and BC analyzed the data and discussed the results; CBM, OP, JAC, BC, wrote the manuscript; CBM designed all the figures and the questionnaire using the online platform.

Impact statement

This research contributes to beach planning and coastal management in insular countries. The 27 recommendations proposed being suitable to be used during the pandemic period, the new normality, and in other post-pandemic scenarios. All the recommendations are designed to seek safe and sustainable tourism on urban and touristic beaches. Governments and decision-makers can help to test this proposal during and after the pandemic. The recommendations were validated by international experts from an Ibero-American network and by Cuban experts that research and work in beaches. The article seeks to open a discussion about beach planning and coastal management. The designed recommendations are expected to be carried out in other insular states.

Ethical statement

The present manuscript has never been published before, and it is not under consideration by any other publisher. Its publication has been approved by all authors and, if accepted, it will not be published by other editors, nor in other languages without written authorization by the holder of the author's rights.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

The authors want to express gratitude to the members of the three Cuban nodes of PROPLAYAS Network. Fifteen professionals from the Physical Planning Institute and the Environmental Ministry in Cuba, as well as some international experts from “Proplayas”, “IBERMAR”, and Cathedra “Stephen Olsen”, are also recognized. These experts answered the questionnaire. Our acknowledgments to Professor Jose R. Souza Filho and Paloma Arias, from Brazil, Gabriel Sánchez Mexico, Aurea, Puerto Rico, Prof. Carlos Pereira, Portugal and Enzo Pranzini, Italy. All of them gave different photographs allowing us could observe changes on the beach during COVID 19 lockdown.

Footnotes

Porto da Barra, Brazil is an internationally recognized tourist beach. Chosen by The Guardian newspaper as the second most important beach in the world.

Appendix 1. Practices and actions of beach planning and management during the COVID-19 lockdown

| Variables analyzed | Practices and actions proposed | Countrie/source |

|---|---|---|

| Equipment and facilities |

|

Sigar, Galicia, Spain Xavi (2020) |

|

Spain (https://elpais.com) |

|

|

Italy (www.elcorreo.com) |

|

|

Island “Padre Sur” and Island “Mujeres”, Mexico www.telemundo51.com |

|

|

Chipiona, Cádiz Spain (Garófano, 2020) |

|

| Biosafety and hygiene measures |

|

Portugal APA (2020) |

|

Island “Padre Sur” and Island “Mujeres”, Mexico www.telemundo51.com |

|

|

Mar del Plata, Argentina La Capital (2020) |

|

|

Chile, Cuba island; Colombia (www.cooperativa.cl; Granma (2020); (Resolución 1538 del 2020) |

|

|

Bournemouth, UK Noticias (2020) |

|

|

Soko Archipelago (El Cacho, 2020) www.lavanguardia.com/ |

|

|

Barú island, Colombia www.eltiempo.com |

|

|

Island “Grande”, Colombia www.eltiempo.com |

|

|

Island Anguila, in the Caribben Region www.elpais.com.uy/ |

|

|

Cuba island (Granma, 2020) | |

| Reorganization of spaces |

|

Benidorm, Spain www.visitbenidorm.es/ver/5668.html |

|

Gandia town hall, Valencia, Spain (https://www.antena3.com) |

|

|

Bondi beach, Australia (The Sidney morning Herald, 2020) (Gorrey, 2020) | |

|

Beaches “Levante” and “Poniente”, Spain (www.benidormbeachsafety.es) |

|

|

Portugal APA (2020) |

|

|

Mujeres island, Mexico www.telemundo51.com | |

|

Chipiona, Cádiz Spain (Garófano, 2020) |

|

| Beach access |

|

Varadero, Cuba. (MondoBalneare.com) |

|

DIMAR, Colombia, (Zuñiga 2020). (https://www.eltiempo.com/colombia/barranquilla/ |

|

|

(Resolución 1538 del 2020) Colombia www.telemundo51.com Mexico |

|

|

(Resolución 1538 del 2020) Colombia | |

|

Benidorm, Spain www.visitbenidorm.es/ver/5668/.html |

|

| Level of occupancy and beach monitoring |

|

Town councils of Spain (Muñoz, 2020) El País (https://elpais.com/) |

|

Portugal and the Autonomous Regions (APA, 2020) (Info Praia, 2020a.b.) |

|

|

Portugal, Island “Madeira” and “Azores” (https://play.google.com/store/apps/) |

|

|

Beaches of Gipuzkoa, Spain (Medio ambiente 2020 a,b.) |

|

|

Beaches of Chipiona https://m.facebook.com/playaschipiona/photos/ |

|

|

Chipiona, Cádiz Spain (Garófano, 2020) |

|

|

Beaches of the municipalities of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil (Vicon SAGA mobile, 2020; Mar à Vista, 2020) | |

| Signage |

|

Department of the Environment Provincial Council of Gipuzkoa in collaboration with Azti (Medio ambiente, 2020b, Medio ambiente, 2020a.) |

|

Rosarito municipality, Mexico (IMPLAN, 2020). |

References

- Acn Karla Castillo Moret, La Biomodulina T y su empleo positivo en la lucha contra la COVID-19. 2020. http://www.acn.cu/salud/65798-la-biomodulina-t-y-su-empleo-positivo-en-la-lucha-contra-la-covid-19?fbclid=IwAR0iM5NiTT--1HoZtXlUDoDPt2Ty3vxn_l9ovZaqvo9DfOKzogxdX0Umgm8 Available in.

- Amyot J., Grant J. Environmental Function Analysis: a decision support tool for integrated sandy beach planning. Ocean Coast Manag. 2014;102(PA):317–327. [Google Scholar]

- APA (Agencia Portuguesa do Ambiente) MANUAL | Linhas Orientadoras. Regime excecional e temporário para a ocupação e utilização das praias, no contexto da pandemia COVID-19. 2020. https://sniambgeoviewer.apambiente.pt/GeoDocs/geoportaldocs/Docs/Manual_EpocaBalnear2020_vf.pdf ÉPOCA BALNEA. “IR À PRAIA EM SEGURANÇA” Available in. accessed 24 october 2020.

- Bates A.E., Primack R., Moraga P., Duarte C. COVID-19 pandemic and associated lockdown as a “Global Human Confinement Experiment” to investigate biodiversity conservation. Biol. Conserv. 2020;248:108665. doi: 10.1016/j.biocon.2020.108665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batista Milanes C. In: 2nd edition. FINKL C.W., MAKOWSKI C., editors. Vol. 1. Springer Nature; Cham, Switzerland: 2018. Coastal risk; pp. 524–534.https://link.springer.com/referenceworkentry/10.1007%2F978-3-319-48657-4_408-1 (Encyclopedia of Coastal Science). Disponible en. Consultado el 24 de octubre de 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Batista Milanes C. In: 2nd edition. FINKL C.W., MAKOWSKI C., editors. Vol. 1. Springer Nature; Cham, Switzerland: 2018. Coastal flood hazard mapping; pp. 471–479. (Encyclopedia of Coastal Science). Disponible en. Consultado el 18 de diciembre de 2018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bianchi F., Funari E., Lami G., Pezzini G., Pranzini E. In: EL TURISMO DE SOL Y PLAYA EN EL CONTEXTO DE LA COVID-19. ESCENARIOS Y RECOMENDACIONES. Publicación en el marco de la Red Iberoamericana de Gestión y Certificación de Playas – PROPLAYAS. 2020. Botero C.M., Mercadé S., Cabrera J.A., Bombana B., editors. 2020. Contribución Especial. Propuestas de la Sociedad Nacional de Salvamento de Italia para la gestión de playas en la temporada 2020 en relación con el riesgo de contagio de COVID; p. 120. Santa Marta (Colombia) [Google Scholar]

- Bonney R., Shirk J., Phillips T., Wiggins A., Ballard H., Miller-Rushing A., Parrish J. Next steps for citizen science. Science. 2014;343(6178):1436–1437. doi: 10.1126/science.1251554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Botero C.M., Arrizabalaga M., Milanés C., Vivas O. Revista Luna Azul. Vol. 45. Disponible; en: 2017. Indicadores de gobernabilidad para la gestión del riesgo costero en Colombia; pp. 227–251.http://200.21.104.25/lunazul/downloads/Lunazul45_12.pdf [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Botero C.M., Cabrera J.A., Zielinski S. In: Encyclopedia of Coastal Science. Finkl C.W., Makowski C., editors. Springer International Publishing; 2018. Tourist beaches. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Botero C.M., Mercadé S., Cabrera J.A., Bombana B., edit . ESCENARIOS Y RECOMENDACIONES. Publicación en el marco de la Red Iberoamericana de Gestión y Certificación de Playas – PROPLAYAS.2020. 2020. EL turismo de sol Y playa en el contexto de la COVID-19; pp. 118–125. Santa Marta (Colombia). Páginas. [Google Scholar]

- Botero C.M., Mercadé S., Cabrera J.A., Bombana B., edit . ESCENARIOS Y RECOMENDACIONES. Publicación en el marco de la Red Iberoamericana de Gestión y Certificación de Playas – PROPLAYAS. 2020. 2020. ELTURISMO de sol Y playa en el contexto de la COVID-19; pp. 49–52. Santa Marta (Colombia). Páginas. [Google Scholar]

- Cabrera H.J.A., et al. Manejo integrado costero en Iberoamérica. Un diagnóstico. Necesidad del cambio” editado por la Red MCI-IBERMAR a través del Servicio de Publicaciones del Programa. CYTED; Spain: 2009. El Manejo integrado costero en Cuba: un camino, grandes retos” En: barragán Muñoz, J.M. (coord.) [Google Scholar]

- Cabrera J.A., et al. Revista de Medio Ambiente, Turismo y Sostenibilidad. Universidad del Caribe y Dirección de Medio Ambiente del Ayuntamiento de Solidaridad (Quintana Roo, México); 2009 b. Evaluación del programa de manejo integrado de la playa de Varadero (Cuba): 7 años de experiencias y retos. ISSN 1870-1515. [Google Scholar]

- Cabrera H.J.A., Conde D. In: Ciencias marino-costeras en el umbral del siglo XXI: desafíos en Latinoamérica y el Caribe. Muñiz Pablo, et al., editors. AGT; S. A. México: 2019. Experiencias y retos del manejo costero integrado a nivel local en Iberoamérica. ISBN: 978-607. [Google Scholar]

- Cepal . Naciones Unidas CEPAL; 2020. Dimensionar los efectos del Covid-19 para pensar en la reactivación; p. 21p. Informe especial no.2 Covid-19. [Google Scholar]

- Cervantes O., Espejel I., Arellano E., et al. Users' perception as a tool to improve urban beach planning and management. Environ. Manag. 2008;42:249. doi: 10.1007/s00267-008-9104-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chakraborty M.D.N. The COVID‐19 pandemic and its impact on mental health. Prog. Neurol. Psychiatr. 2020;24(2):21–24. doi: 10.1002/pnp.666. April/May/June 2020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cubadebate La industria farmacéutica cubana garantiza la producción de fármacos con alta eficacia para el tratamiento de la COVID-19. 2020. https://www.facebook.com/cubadebate/posts/10157873607578515 Available in. accessed 9 jun 2020.

- Daza S. Newspaper “El Tiempo”. Algunos comportamientos que alimentan la indisciplina ante el covid-19. Autojustificación y negación, mecanismos que hacen que terminemos afectando a los demás. 2020. https://www.eltiempo.com/vida/coronavirus-hoy-algunos-comportamientos-que-alimentan-la-indisciplina-ante-el-covid-19-534878 Avalilable in. accessed 20 august 2020.

- Decreto 2013. Por el cual se reglamenta el funcionamiento de los Comités Locales para la Organización de las Playas de que trata el artículo 12 de la Ley 1558 de 2012. 1766. https://www.dimar.mil.co/node/524 Available in. accessed 15 september 2020.

- Departamento de Salud Euskadi, 2020. Transparencia sobre el nuevo coronavirus (COVID-19). Normativa de medidas excepcionales adoptadas en Euskadi. 2020. https://www.euskadi.eus/normativa-de-medidas-excepcionales-adoptadas-por-el-nuevo-coronavirus-covid-19/web01-a2korona/es/ Available in. accessed 10 October 2020.

- Diario 6124 Cuba cerrará el año con 4,3 millones de turistas, un 8,5% menos. 2021. Available in https://www.hosteltur.com/130649_cuba-cerrara-el-ano-con-43-millones-de-turistas-un-85-menos.html.

- Díaz-Canel M., Núñez J. Government management and Cuban science in the confrontation with COVID-19. Anales de la Academia de Ciencias de Cuba. 2020;10(2) https://bit.ly/2ZfspYx [Google Scholar]

- Doyle A., Hynes W., Purcell S.M. Building resilient, smart communities in a post-COVID era: insights from Ireland. Int. J. E Plann. Res. 2021;10(2):18–26. doi: 10.4018/IJEPR.20210401.oa2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ehrenberg J.P., Utzinger J., Fontes G., et al. Efforts to mitigate the economic impact of the COVID-19 pandemic: potential entry points for neglected tropical diseases. Infect Dis Poverty. 2021;10:2. doi: 10.1186/s40249-020-00790-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El Cacho, Joaquim Descubren miles de mascarillas convertidas en residuos en islas deshabitadas. 2020. https://www.lavanguardia.com/natural/20200313/474107668765/impacto-ambiental-coronavirus-covid-mascarillas-residuos-contaminacion-playas-china.html Available in. accessed 4 november 2020.

- El Heraldo Poca afluencia de visitantes a las playas del departamento. Control de aforo y distanciamiento social se cumplió en los sitios turísticos. 2020 https://www.elheraldo.co/playas?utm_source=ELHERALDO&utm_medium=articulo&utm_campaign=recirculacion&utm_term=temas-tratados Available in. [Google Scholar]

- El Heraldo Playas de Puerto Colombia, sin control en puente festivo. 2020. https://www.elheraldo.co/atlantico/playas-de-puerto-colombia-sin-control-en-puente-festivo-765345 Available in.

- El Correo Diseñan cubículos de plástico para playas y restaurantes. 2020. https://www.elcorreo.com/tecnologia/emprendedores/cubiculos-playa-restaurantes-coronavirus-20200415130842-nt.html Published by EFE Available in. accessed 25 october 2020.

- Eyawo O., Viens A.M., Ugoji U.C. Lockdowns and low- and middle-income countries: building a feasible, effective, and ethical COVID-19 response strategy. Glob. Health. 2021;17:13. doi: 10.1186/s12992-021-00662-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galib B. SARS-CoV-2(COVID-19) J. Fac. Med. Baghdad. 2020 http://iqjmc.uobaghdad.edu.iq/index.php/19JFacMedBaghdad36/article/view/1737 [Internet]. 15Apr.2020 [cited 8May2020];61(3,4). Available from. accessed 14 november 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Garófano, L., 2020. Así diseñó Chipiona el ordenamiento de su playa que la ha hecho famosa en Reino Unido. Available in https://www.elmundo.es/andalucia/2020/08/03/5f2831d9fc6c836a348b4599.html (accessed 30 august 2020).

- Gerhartz-Abraham A., Fanning L.M., Angulo-Valdés J. ICZM in Cuba: challenges and opportunities in a changing economic context. Mar. Pol. 2016;73:69–76. [Google Scholar]

- Gobierno de México Lineamiento general para la mitigación y prevención de COVID-19 en espacios públicos abiertos. 2020. https://coronavirus.gob.mx/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/Lineamiento_Espacios_Abiertos_07042020.pdf Versión 2020.4.7. 22pp. Available in. accessed 25 october 2020.

- Gobierno de México, 2020b. “Lineamiento Nacional para la reapertura del Sector Turístico” 129 p. Available in https://coronavirus.gob.mx/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/Lineamiento_nacional_reapertura_turismo_20052020.pdf (accessed 12 september2020).

- Gobierno de México Protocolo de atención para personas de nacionalidad mexicana y extranjera que se encuentran en territorio nacional mexicano en centros de hospedaje durante la cuarentena obligatoria por COVID-19. 2020. https://coronavirus.gob.mx/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/Protocolo_Hoteles_COVID-19.pdf 6 p. Available in. accessed 18 november 2020.

- Gobierno Vasco . Departamento de Salud; Vitoria Gasteiz: 2020. Criterios sanitarios para la apertura y uso de las playas y zonas de baño de la cav en situación de pandemia por SARS-CoV-2.https://www.euskadi.eus/contenidos/informacion/playas_covid/es_def/adjuntos/Criterios-sanitarios-playas-COVID19.pdf 28 de julio de2020. 8pp. Available in. accessed 10 september 2020. [Google Scholar]

- GORC [Official gazette of the republic of Cuba]. Decree law number 212 coastal zone managament. Cuba, 14 de august 2000. 2000. http://www.gacetaoficial.cu/ 1373, 1378. Available in. Accessed 12 February 2020.

- Gorrey M. Newspaper the Sidney morning Herald, bringing Italy to sydney: 'euro beach chic' bar proposed for bondi. 2020. https://www.smh.com.au/national/nsw/bringing-italy-to-sydney-euro-beach-chic-bar-proposed-for-bondi-20201007-p562zp.html available in. accessed 26 october 2020.

- Gössling S., Scott D., Hall C.M. Pandemics, tourismand global change: a rapid assessment of COVID-19. Journal of Sustainable Tourism To link to this article. 2020 doi: 10.1080/09669582.2020.1758708. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Granma COVID-19: ¿Cómo protegerse en temporada de playa? 2020. http://www.granma.cu/cuba-covid-19/2020-07-14/covid-19-como-protegerse-en-temporada-de-playa-14-07-2020-23-07-54 Disponible en. accessed 8 november 2020.

- Graziano T. Smart technologies, back-to-the-village rhetoric, and tactical urbanism: post-COVID planning scenarios in Italy. Int. J. E Plann. Res. 2021;10(2) doi: 10.4018/IJEPR.20210401.oa7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hsiang, S., Allen, D., Annan-Phan, S. et al. 2020. The effect of large-scale anti-contagion policies on the COVID-19 pandemic. Nature 584, 262–267 (2020). 10.1038/s41586-020-2404-8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Hsieh H., Shannon S. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual. Health Res. 2005;15(9):1277–1288. doi: 10.1177/1049732305276687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- IMPLAN, 2020. Normas para el uso de las playas covid-19/semáforo naranja Available in https://www.arcgis.com/apps/MapJournal/index.html?appid=49b64093b8a64e548fe37634902f9d39 (accessed 10 october 2020).

- Info Praia, 2020a. Available in https://apambiente.maps.arcgis.com/apps/opsdashboard/index.html#/a0b2369c54a04c6395b73bd2541b8004 (accessed 12 august 2020).

- Info Praia, 2020b. Available in https://play.google.com/store/apps/details?id=pt.apambiente.info_praia&hl=es (accessed 22 jun 2002).

- Juanes J.L., et al. UNEP/ROLAC GPA. Agencia de Medio ambiente; La Habana, Cuba: 2003. Diagnóstico de los Procesos de Erosión en las Playas Arenosas del Caribe. [Google Scholar]

- Kock F., Nørfelt A., Josiassen A., Assaf A.G., Tsionas M.G. Understanding the COVID-19 tourist psyche: the evolutionary tourism paradigm. Ann. Tourism Res. 2020;85 doi: 10.1016/j.annals.2020.103053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreiner N.C., Ram Y. National tourism strategies during the Covid-19 pandemic. Ann. Tourism Res. 2020;18:103076. doi: 10.1016/j.annals.2020.103076. Oct 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- La Capital Para veranear en Mar del Plata habrá que hacerse un hisopado. 2020. https://www.lacapitalmdp.com/para-veranear-en-mar-del-plata-habra-que-hacerse-un-hisopado/ Available in. Mar del Plata, Argentina. accessed 30 august 2020.

- Lal R., Brevik E.C., Dawson L., Field D., Glaser B., Hartemink A.E., Hatano R., Lascelles B., Monger C., Scholten T., Singh B.R., Spiegel H., Terribile F., Basile A., Zhang Y., Horn R., Kosaki T., Sánchez L.B.R. Managing soils for recovering from the COVID-19 pandemic. Soil Syst. 2020;4:46. [Google Scholar]

- Lancet Public Health Will the COVID-19 pandemic threaten the SDGs? 2020. volume 5, issue 9, e460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Lee-Peng F., Mui-Yin C., Kim-Leng T., Kit-Teng P. The impact of COVID-19 on tourism industry in Malaysia. Curr. Issues Tourism. 2020 doi: 10.1080/13683500.2020.1777951. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Hai, YueManzoorAqsaWang, Cang Yu, Zhang Lei, Manzoor Zaira. The COVID-19 Outbreak and Affected Countries Stock Markets Response. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2020;17(8):2800. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17082800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lozoya J.P.J., Cabrera A., Botero C., Polette M., y Cervantes O. In: Ciencias marino-costeras en el umbral del siglo XXI: desafíos en Latinoamérica y el Caribe. Muñiz Pablo, et al., editors. 2019. Gestión integrada de playas en América Latina: servicios ecosistémicos y nuevos enfoques. 2019 AGT Editor, S. A. México, ISBN: 978-607. [Google Scholar]

- Mar à Vista, 2020. Avilable in https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCqKed5Iwizu_jl-fZilzCQw (accessed 9 july 2020).

- Medio ambiente Casi el doble de usuarios ha podido disfrutar de los arenales gracias a las medidas de control de aforos que se han llevado a cabo por la COVID-19. 2020. https://www.gipuzkoa.eus/es/web/ingurumena/-/erabiltzaile-kopuru-bikoitzak-gozatu-ahal-izan-du-hareatzez-covid-19-dela-eta-hartu-diren-aforo-neurriei-esker accessed 25 september 2020.

- Medio ambiente La App de playas “Nik Hondartzak” supera las 30.000 descargas en una semana. 2020. https://www.gipuzkoa.eus/es/web/ingurumena/-/-nik-hondartzak-aplikazioak-30-000-deskarga-baino-gehiago-lortu-ditu-astebetean Disponible en. accessed 12 october 2002.

- Milanes Celene B, et al. Pereira, Cristina y Botero Camilo Mateo. Improving a decree law about coastal zone management in a small island developing state: The case of Cuba. Marine Policy. 2019;101:93–107. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2018.12.030. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Milanes Batista CM, Planas JA, R Pelot, JR Núñez (2020). A new methodology incorporating public participation within Cuba's ICZM program. Ocean & Coastal Management, V. 186, p. 105101. 10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2020.105101. [DOI]

- Milanés B.C. In: El turismo de sol y playa en el contexto de la covid-19. Escenarios y recomendaciones. Botero C.M., Mercadé S., Cabrera J.A., Bombana B., editors. Publicación en el marco de la Red Iberoamericana de Gestión y Certificación de Playas – PROPLAYAS; Santa Marta (Colombia: 2020. Repensando la planificación y gestión del riesgo en playas tras un escenario post-pandemia COVID-19; pp. 49–52. [Google Scholar]

- Ministerio de Salud Costa Rica. LS-PG-013. Lineamientos generales para el uso de playas ante el Coronavirus (COVID-19) 2020. https://www.ministeriodesalud.go.cr/sobre_ministerio/prensa/docs/ls_pg_013_playas_28072020.pdf 16 p. Available in. accessed 12 september 2002.

- Minrex Cuba. Informe de Cuba sobre la resolución 73/8 de la asamblea general de las naciones unidas. “necesidad de poner fin al bloqueo económico, comercial y financiero impuesto por los estados unidos de américa contra Cuba”. 2019. http://www.cubaminrex.cu/sites/default/files/2019-09/Cuba%20vs%20Bloqueo.pdf accessed 13 jun 2020.

- Mintur Turismo Seguro en Cuba. Protocolos y medidas que todo turista debe conocer. 2021. https://www.mintur.gob.cu/turismo-seguro-en-cuba-protocolos-y-medidas-que-todo-turista-debe-conocer/ Available in. acceced 09 february 2021.

- Mukherjee M., Chatterjee R., Khanna B.K., Prakash A., Shaw R. Ecosystem-centric business continuity planning (eco-centric BCP): a post COVID19 new normal. Progress in Disaster Science. 2020;7:100117. doi: 10.1016/j.pdisas.2020.100117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muñoz R. El País. Videovigilancia automática para controlar el aforo de las playas. 2020. https://elpais.com/economia/2020-06-05/videovigilancia-automatica-para-controlar-el-aforo-de-las-playas.html?utm_source=Facebook&ssm=FB_CM#Echobox=1591463685 Available in. accessed 23 jun 2020.

- Noticias El medio 'The Telegraph' alaba la gestión de la playa de Benidorm tras el caos en las playas británicas. 2020. https://www.antena3.com/noticias/mundo/el-medio-the-telegraph-alaba-la-gestion-de-la-playa-de-benidorm-tras-el-caos-en-las-playas-britanicas_202006285ef8ce59f9cab90001757544.html Available in. accessed 25 october 2020.

- Niusdiario.es / Agencias. 2020. Desalojan de madrugada a 200 jóvenes en la playa https://www.niusdiario.es/sociedad/sanidad/desalojan-madrugada-200-jovenes-playa-postiguet-alicante-cadena-humana-policias_18_3002745056.html (accessed 23 october 2020).

- ONU La Asamblea General reitera con 187 votos su posición contra el embargo a Cuba. 2019. https://news.un.org/es/story/2019/11/1465061 7 Available in. accessed 28 jun 2020.

- ONU News united nations. Asuntos económicos. 2019. https://news.un.org/es/story/2019/11/146506 Available in. accessed 24 jun 2020.

- OPS Cuba frente a la COVID-19 andar la salud. 2020. https://iris.paho.org/bitstream/handle/10665.2/52514/v24n2.pdf.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y checked 46 vol.24 no.2 available in. accessed 28 november 2020.

- Ostle B. Editorial: Literary Licensing; 2012. Statistics in Research: Basic Concepts and Techniques for Research Workers; p. 500. 10 : 1258401649. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez M.O., Milanés B.C. Social perception of coastal risk in the face of hurricanes in the southeastern region of Cuba. Ocean Coast Manag. 2020;184(1):105010. doi: 10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2019.105010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]