Abstract

Social media has been increasingly utilized as an effective avenue for individuals to obtain needed social support and health-related information, especially during the on-going global COVID-19 pandemic. However, surprisingly few empirical studies have concentrated on the detrimental impact of social media adoption on young adults’ psychosocial well-being and mental health. Drawing upon previous stressor-strain-outcome theoretical paradigm (SSO), the present research investigates how psychosocial well-being assessments, especially compulsive WeChat use and information overload could trigger social media fatigue and, furthermore, how social media fatigue would ultimately result in emotional stress and social anxiety. This article utilized the cross-sectional design whereby statistical data were collected from 566 young people to test the conceptual research model. This research results demonstrate that perceived information overload through WeChat could significantly trigger social media fatigue among young people. Moreover, perceived information overload could indirectly predict emotional stress and social anxiety through the mediation of social media fatigue. This present work has vital theoretical and practical implications for widespread adoption of newly emerging communication technologies to enhance mental health and well-being among younger generation during recent public health crises.

Keywords: Compulsive WeChat use, Information overload, Emotional stress, Social anxiety, Social media fatigue

1. Introduction

As a global health emergency, the unexpected outbreak of the novel coronavirus pneumonia (COVID-19) has brought tremendous effects on various aspects of individual’s everyday routines (Liu et al., 2021a, Liu et al., 2021b, Soroya et al., 2021, Teng et al., 2021). In response to such surge crisis, a series of significant preventative measures were implemented by many countries to avoid the rapid transmission of coronavirus. These measures have immediately led to the temporary cancellations of conferences and events, closure of educational institutions, commercial spaces, as well as public areas (Ares et al., 2021, Islam et al., 2020), along with suggestions of keeping social distance (Nabity-Grover et al., 2020, Zhang et al., 2021). As more social activities move online, social networking sites (SNSs) have currently became the effective and essential avenue for users to acquire reliable information and health recommendations about this unprecedented global pandemic (Ares et al., 2021, Mamun et al., 2021). Despite considerable exploratory studies have concentrated on the possible benefits of adopting SNSs such as improved social capital, social support, and relationship sustainment (Hu et al., 2017, Munzel et al., 2018, Nabity-Grover et al., 2020), comparatively few systematic investigations have quantitatively explored the potential detrimental psychological effects of SNSs on users’ well-being and mental health during the ongoing coronavirus pandemic, especially among younger generations.

Some survey-based work has identified that the possible linkages between social media interaction and young people’s declined mental state in the pandemic outbreak, such as society anxiety, fear of missing out, and depressive moods (Ares et al., 2021, Pang, 2020, Zhong et al., 2021). According to the recently available data, approximately three fifths of youth adults are disturbed by COVID-19 and majority of them suffer from anxious and depressive symptoms (Liu et al., 2021a, Liu et al., 2021b, Ngien and Jiang, 2021). Mental well-being and health problems have been closely related to young people’s SNS adoption (Pang, 2021b, Akbay, 2019, Xie et al., 2018). More importantly, enormous health-related content from SNS platforms might amplify perceived risk or fears and adversely impacting individuals’ mental health and psychological status (Fu et al., 2020, Mamun et al., 2021, Soroya et al., 2021, Yang et al., 2019). As a generation of “digital natives”, tech-savvy youth adults have constituted the majority of social media users, but they normally experience greater information overload in this ubiquitous digital media environment (Liu et al., 2021a, Liu et al., 2021b). Nevertheless, there is currently limited knowledge regarding the psychological mechanisms of how COVID-19 information overload associated with social media fatigue and its potential implications on young people’s psychological development.

Past studies demonstrated increased SNS use among young people could be attributed to the worldwide social distancing directives and lockdowns at the early stage of the epidemic (Liu et al., 2021a, Liu et al., 2021b, Zhong et al., 2021). However, after undergoing diverse technological, informative or communicative overloads via their engagement and communication on SNSs, individuals are escaping from participation on these communication services due to suffering social media fatigue (Benson et al., 2019, Whelan et al., 2020). Younger generations’ SNS disengagement desire enhanced during this initial lockdown period and was illustrated in the declined SNS use in the later phases (Islam et al., 2020). Some pieces of verifiable evidence uncovered that the key determinants of social media fatigue could be derived from specific psychosocial and behavioural factors, mainly consisting of information overload, connection overload, and social interactive activities (Teng et al., 2021, Zhang et al., 2021). Additionally, from an individual level, social media fatigue would result in deterioration in young adults’ spiritual and physiological issues whereby they incline to cultivate unhealthy behaviours (Dhir et al., 2018, Liu et al., 2021a, Liu et al., 2021b). Recently, WeChat users appear to express negative feelings about social media because boredom and exhaustion with a wealth of COVID-19 information and excessive requirements from friends for “reposts,” “likes,” and “comments” (Guo et al., 2020, Pang, 2019, Teng et al., 2021). A growing body of recent evidence also indicates that WeChat has currently become one of the most influential sources of information on this novel coronavirus (Ngien and Jiang, 2021, Zhang et al., 2021). Although such emerging phenomenon has recently drawn attention from scholars and researchers, empirical studies on the association between WeChat use behaviors and well-being development of young people remain scarce during the COVID-19 pandemic. Furthermore, little is known about the underlying mechanisms of how perceived information overload and compulsive WeChat use could cause young adults’ social media fatigue and negative psychological consequences.

To fulfil the above-mentioned existing research gaps, this article adopted the influential stressor–strain–outcome (SSO) theoretical framework to systematically uncover whether compulsive WeChat use and COVID-19 information overload could trigger young people’s social media fatigue in mainland China. Further, whether social media fatigue would ultimately lead to increased emotional stress and social anxiety among them during this current public health emergency. More specifically, the study conceptualized COVID-19 information overload and compulsive WeChat use as stress-related factors, social media fatigue as a strain factor, and emotional stress and society anxiety as consequence factors, and explored the intricate interrelationships between these main factors. By doing so, this work may offer a significant extension of present studies in the pattern of a detailed theoretical comprehending of the psychosocial mechanisms underlying newly emerging technology use and related health outcomes.

2. Theoretical foundation and hypothesis development

2.1. Linking compulsive WeChat use to social media fatigue

Compulsive use underlines an individual’s aberrant behavior of being unable to rationally control or regulate his own routine performances (Gámez-Guadix et al., 2012, Zhang et al., 2020a, Zhang et al., 2020b). The term is typically more closely related to its causal linkages with online addiction disorder in the investigations of new media adoption and network service. Along with SNSs continue to pervasively penetrate into various aspects of our daily lives while also gradually optimizing characteristics and functionality, compulsive use has become an extremely significant issue, especially among young people (Benson et al., 2019, Fox and Moreland, 2015, Akbay, 2019). Compulsive use has been mainly explored in a series of unhealthy physiological behaviors, consisting of cigarettes or alcohol abuse, gaming addiction, as well as excessive specific SNS usage (Klobas et al., 2018, Soroya et al., 2021). Notably, irregular and uncontrollable activities of utilizing internet-based applications would lead to an adverse cognitive state, thereby impacting individuals’ psychological and mental well-being and behavioral intentions. A handful of researchers have associated compulsive use with diverse detrimental psychiatric and physical illnesses, such as emotional disturbance, social isolation, and impairment of academic achievement (Baker and Algorta, 2016, Chow and Wan, 2017, Akbay, 2019).

Although compulsive use behaviour has attracted the extensive attention of considerable researchers, few studies have concentrated on the antecedents and consequences of compulsive SNS use. Only recent efforts devoted to empirically assess the implications for compulsive use of SNS and other interactive spaces, such as online games (Benson et al., 2019, Yang et al., 2020). As research continues developing, empirical evidence suggests that compulsive media use is positively associated with social media fatigue (Dhir et al., 2018, Islam et al., 2020, Mamun et al., 2021). Some medical investigations argued that by definition, fatigue is a multifaceted phenomenon that reflects a series of self-evaluated and overwhelming sense (Pang, 2021a, Wijesuriya et al., 2007). From the clinical and occupational perspectives, social media fatigue refers to the self-regulated and adverse emotional experience that includes feelings of tiredness, disappointment, boredom, burnout, loss of interest, or declined usage of SNSs and decreased motivation (Teng et al., 2021, Zhang et al., 2016). Essentially, social media fatigue may occur when users feel tired of numerous functions and fragmented information on SNSs services and attempt to escape (Whelan et al., 2020). The growing pervasiveness of SNSs leads to problematic use, which would have some harmful consequences, such as social network fatigue and stress (Ngien and Jiang, 2021, Swar et al., 2017).

Social media fatigue is recognized as the consequence of overload, and some studies have probed the potential linkage between compulsive use and social media fatigue. For instance, Brand, et al. identified that excessive and problematic involvement in Internet-related behaviors would result in negative attitudes and cognitive processes which finally impact mental and psychological functions and motivations (Brand et al., 2016). Likewise, Pontes discovered that compulsive SNS use could exacerbate young people’s emotional disturbance, ultimately leading to negative use intention toward new communication technologies (Pontes, 2017). Later, Dhir, et al. found that compulsive mobile SNS use could positively predict tendency to suffer fatigue among North Indian participants (Dhir et al., 2018). A recent study by Y. Zhang, Liu, et al. confirmed that compulsive use is one of the key stressors of social media fatigue (Zhang et al., 2020a, Zhang et al., 2020b). According to these above-mentioned conclusions, it is possible that compulsive WeChat use may also negatively impact the cognitive performances and lead to social media fatigue. Extending from the literature, the study predicts:

H1: Compulsive WeChat use is positively associated with social media fatigue among young people.

2.2. Linking information overload to social media fatigue

Information overload is defined as a situation that large amounts of input information exceed an individual’s cognitive capacity for information processing (Guo et al., 2020, Islam et al., 2020). Humans normally have limited information processing abilities, and ultimately, when they are confronting with too much contents, the quality of decision-making suffers (Teng et al., 2021, Yang et al., 2018). Information overload occurs when information-processing needs exceed one’s capacity to effectively deal with the information within the time available (Pennington and Tuttle, 2007, Zhang et al., 2021). Once experiencing information overload, people tend to feel overwhelmed and even sense of psychological stress and other emotional states. With the fast progress of communication technology, people have multiple channels to access massive amount of data, which would lead to information overload. Given tremendous information could be instantly generated and transmitted through SNSs, information overload is regarded as a side impact of the digital era (Liu et al., 2021a, Liu et al., 2021b, Pang, 2018).

The negative influence of information overload has caused widespread concern over researchers. In recent years, information overload has been extensively explored in different settings such as social media platforms, web-based health information searches, and mobile social apps (Fu et al., 2020, Ngien and Jiang, 2021, Whelan et al., 2020). Scholars claimed that information overload would influence people’s execution and decision-making capability (Li and Chan, 2021, Swar et al., 2017). Especially technological, information and interaction overloads via SNS users’ engagement and communication on diverse applicants will lead to fatigue and stress (Fu et al., 2020). Moreover, information overload has become the primary source of psychological stress impact social media fatigue (Li and Chan, 2021, Liu et al., 2021a, Liu et al., 2021b). In the context of COVID-19, diverse SNSs as the principal information resource of crisis events and updates, were utilized to convey huge quantities of information about this global public health emergency (Islam et al., 2020). Meanwhile, young people frequently and excessively involved in social media activities and constantly obtained a variety of COVID-19 messages, which may potentially result in the perception of pandemic-related information overload and elicit adverse psychological outcomes (Liu et al., 2021a, Liu et al., 2021b, Soroya et al., 2021).

Previous studies have clearly demonstrated that perceived high level of information overload exerts the significant and positive relationship with SNS users’ psychological and physiological well-being (Swar et al., 2017, Teng et al., 2021, Zhang et al., 2021). The fundamental cause is that individuals’ ability for handling information can not keep up with the growth rate of information on social media (Islam et al., 2020, Li and Chan, 2021). During the period of this current global pandemic, massive amounts of information, pictures, videos, and related online opinions forwarded by users through SNSs are increasing dramatically, but the capability to process this information is comparatively limited (Liu et al., 2021a, Liu et al., 2021b). Bombarded with information from social media devices, WeChat users have to process these massive amounts of irrelevant information day-to-day. Thus, COVID-19 information overloading on WeChat may cause users’ negative psychological responses related to the coronavirus information. Furthermore, youth adults’ increased usage of SNS during the crisis promoted COVID-19 information overload, which also caused them to feel of cognitive strain and stress (Soroya et al., 2021, Zhang et al., 2016). Consequently, this research hypothesises that perceived pandemic information overload may result in social media fatigue.

H2:Information overload is positively associated with social media fatigue among young people.

2.3. Linking social media fatigue to emotional stress

Emotional stress is conceptualized as a variety of uncomfortable affective, cognitive, as well as somatic symptoms of depression because of perceived threatening, detrimental, or challenging circumstance (Pate et al., 2017). The term was recognized as one of the most related stressors in those who had experienced inner disturbances under the COVID-19 pandemic (Li and Chan, 2021, Primack et al., 2017). Perceived emotional stress underlines a subjective assessment of the stress degree suffered by individuals to an objective issue and subjective appraisal to it (Chen and Lee, 2013, Keles et al., 2020). Numerous researchers have linked high perceived emotional stress not only to psychological symptoms such as social strains, depressive mood, as well as secondary trauma (Baker and Algorta, 2016, Zhong et al., 2021), but also to negative mental and physical health including greater disease burden or even severe neurologic damage (Fox and Moreland, 2015, Levy et al., 2009). Individuals with high scores on the social media fatigue scale were likely to indicate diminished enthusiasm and motivation, increased fear of the disease, and even reduced physical actions and behaviors (Benson et al., 2019, Chow and Wan, 2017, Liu et al., 2021a, Liu et al., 2021b).

In the past few decades, emotional stress has drawn broad attention from all over the world and numerous researchers have implemented empirical investigations exploring the causations and outcomes of it in the new media environment. For instance, Maier, et al. illustrated that Facebook users who are encountered with social media fatigue prone to alter their current state and existing unhealthy status (Maier et al., 2015). Based on a survey of 413 young people, Ophir discovered that individuals with stressful feelings associated with social strain, greater anticipations and issues are more willing to employ SNSs for mitigating these adverse moods (Ophir 2017). Similarity, Lin, et al. demonstrated that Chinese adults have been discovered to withstand deterioration in mental and psychological well-being because of passive SNS use (Lin et al., 2021). Recent studies suggested that experiencing emotional stress could cause negative affect and health-related problems, such as psychological and behavioural regulations (Apaolaza et al., 2019; Tunc-Aksan & Akbay, 2019). As a result, emotional stress depression may render individuals susceptible to psychosocial, physiological and relational dilemmas. More recently, some empirical investigations demonstrate that intensive involvement in the online applicants or social media usage lead to emotional stress (Ngien and Jiang, 2021, Zhang et al., 2020a, Zhang et al., 2020b). Moreover, uncontrollability and disengagement of social media would lead to negative emotional response to the demanding situation (Li and Chan, 2021, Malik et al., 2020). Consequently, it is possible that users’ negative feelings of tiredness, boredom, and burnout WeChat activities have become a factor triggering emotional stress. Thus, the article hypothesise that:

H3: Social media fatigue is positively associated with emotional stress among young people.

2.4. Linking social media fatigue to social anxiety

Conceptually, social anxiety refers to the prevalent and debilitating experience of discomfort and avoid interpersonal interactions due to concern about being negatively assessed, refused or embarrassed (Islam et al., 2020, Panayiotou et al., 2020). Social anxiety is a pattern of anxiety-related issue originating from prospect or presence of interpersonal judgement in real-word and imagined situations (Zhang et al., 2020a, Zhang et al., 2020b). Previous literature indicates that anxious individual tends to perceive themselves as suffering from diverse perceptive and appraisal disorders, such as inaccurate cognition of objective environments, and sending untrue alarms, and participating in unreasonable estimation making and incomplete information processing (Brand et al., 2016, Keles et al., 2020, Ophir, 2017). Social anxiety represents affective features and is considered as a negative response, sentiment, and certain anxious disorder involving cognitive, mental, and behavioral dimensions (Steimer, 2002, Tian, 2013). Researchers asserted that in expected and realistic social settings, people may suffer from social anxiety owing to various variables including discomfort, self-consciousness, awkwardness, and insecure (Dhir et al., 2018, Shaw et al., 2015). Additionally, they incline to intentionally avoid such circumstances, in order to not acquire detrimental assessments from others (Fox and Moreland, 2015, Tian, 2013). Furthermore, anxious persons incline to grumble about weary, exhaustion, incomplete performance, and physical illnesses (Ngien and Jiang, 2021, Pate et al., 2017).

Prior research has identified multiple antecedents and consequences of social anxiety, consisting of psychiatric and physiological pain, substance abusing, dysfunctional cognition, exhaustion, and even self-destructive tendency (Keles et al., 2020, Steimer, 2002, Whelan et al., 2020). With the profound expansion of social media, researchers have began to explore the phenomenon of social anxiety among SNS users (Fox and Moreland, 2015, Grieve et al., 2013, Zhang et al., 2020a, Zhang et al., 2020b). For instance, Grieve, et al. found that social connectedness derived from Facebook communication was negatively associated with anxious state (Grieve et al., 2013). Based on data from 174 college students in Turkey, Alkis, et al. discovered that students from ICT-focused programs utilize new media platforms more intensively and report higher degrees of social anxiety on SNS services (Alkis et al., 2017). Similarity, Primack et al. determined that anxious users prone to employ diverse coping strategies on various social media platforms so as to mitigate unfavourable feelings (Primack et al., 2017). Later, Apaolaza, et al. confirmed that compulsive mobile SNS usage is related to distraction and mitigation of psychosocial suffering and mental stress and attention deficiency (Apaolaza et al., 2019). However, few studies explored the linkage between perceived social media fatigue related to the current pandemic and social anxiety. Only several scholars suggested that social media use would result in fatigue and declined cognitive capabilities, which subsequently render users incline to manage and control emotion and attention (Klobas et al., 2018, Zhang et al., 2021). Thus, it is possible that on experiencing fatigue, individuals prone to suffer from social anxiety. Accordingly, the study poises that:

H4: Social media fatigue is positively associated with social anxiety among young people.

3. Research method

3.1. Conceptual model

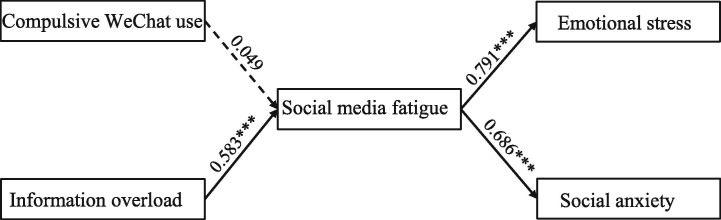

In this current study, the article used the stressor-strain-outcome (SSO) framework for better comprehending the underlying association between social media fatigue and mental health in the WeChat context. Building upon the stressor-strain-outcome theoretical framework, the study theorizes that young people’s compulsive WeChat use and perceptions of information overload are positively correlated with social network fatigue. Moreover, the association between compulsive WeChat use and related psychological well-being is anticipated to be positively moderated by social network fatigue. Fig. 1 illustrates the conceptual model adopted in the research, which reflects the hypothetical relationship among the main variables.

Fig. 1.

The conceptual research model.

3.2. Study participants and data collection

The survey questionnaires were gathered through a web-based survey during April 2020. This current study maily invited young people to engage in this survey during the COVID-19 pandemic, since they constitute the largest portion of SNS users and represent the most active users in contemporary social media age (Ngien and Jiang, 2021, Pang, 2021b). Therefore, the age of most participants ranged from 18 to 30 years. An incentive of 5 RMB was provided to all participants who engaged in this survey. This research selected such online sampling strategy, because it was widely considered to be one of the most effective and efficient ways for researchers to capture a large amount of SNS users (Gong et al., 2020, Langston, 2003). Before the actual research, all participants were informed about the proposed study objectives, related questions, expected benefits and study process. This research involvement was kept voluntary and anonymous, respondents had freedom to withdraw engagement anytime during this investigation and informed oral consent was acquired. A total of 42 invalid questionnaires were removed due to missing data. Hence, the final sample consisted of 566 young people.

3.3. Measurements

3.3.1. Compulsive WeChat use

Compulsive social media use was gauged by four statements adapted from previous research (Andreassen et al., 2012). Participants were required to identify to what degree they agree or disagree with these items. Example items conclude “spent a lot of time thinking about WeChat or planned use of WeChat ?” and “felt an urge to utilize WeChat more and more?”. These responses were based on a five-point Likert scale where 1 = strongly disagree and 5 = strongly agree.

3.3.2. Information overload

The assessment for COVID-19 information overload on WeChat was adapted from Swar et al. (2017). A representative item is “I cannot cope with all the COVID-19-related information on WeChat effectively.” All participants were required to indicate how they feel during the past week using a 5-point-Likert rating scale from“strongly disagree” to “strongly agree”. A total score could be acquired by summing the statements’ scores, with higher total scores indicating higher perceived COVID-19 information overload(M = 2.91, SD = 0.76, Cronbach’s α = 0.71).

3.3.3. Social media fatigue

Social media fatigue was assessed by three statements adapted from previous studies (Malik et al., 2020). Sample items include “I feel frustrated when utilizing WeChat these days” and “I feel emotionally drained after utilizing WeChat these days.” All questions are gauged on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree and 5 = strongly agree), and raw scores are utilized to compute the four subscale scores. Total scores were calculated to indicate the degree of social media fatigue (Cronbach’s a = 0.89).

3.3.4. Emotional stress

The study assessed participants’ self-reported perceptions of their own emotional stress related to the COVID-19 pandemic with all four items from the emotional stress scale (Wiernik et al., 2016). The scale was originally compiled as a global measure of individuals’ perceived emotional stress and the modified version had been confirmed to have good reliability and validity (Fabris et al., 2020). Statements are rated from 1 (not at all) to 5 (very much). The respondents were required to report according to their feelings or thoughts of the COVID-19 in the past month. A total score can be obtained by summing these items’ scores, with higher total scores suggesting more stressful the participants. The scale demonstrated good internal consistency (α = 0.81) in this present sample.

3.3.5. Social anxiety

The scale of social anxiety was adopted and revised from prior studies (Alabdulkareem, 2015). Three statements were used to measure social anxiety in 5-point Likert-type graded responses (1 = strongly disagree and 5 = strongly agree). Sample items include “After browsing WeChat, I am easily annoyed or cranky” and “I am worried about how other people judge me”. The scores on these three questions were averaged to create social anxiety index with a high degree of internal consistency (M = 2.73, SD = 0.78, Cronbach’s α = 0.85).

3.3.6. Socio-demographic variables

The study included the main socio-demographic measures of age, gender, educational background, and WeChat using experience as control variables.

4. Data analysis strategy

The research utilized IBM SPSS 24.0 and IBM AMOS 24.0 for data analysis. First, in order to examine the characteristics of WeChat users in the sample, the study carried out preliminary analyses to gain greater insight into the demographic features and WeChat usage statistics of young people. Second, as a preliminary test of this hypothesis, a series of zero-order correlations was employed to assess the intricate assocations among the scaled variables. Finally, to further identify the associations among the main factors, the study conducted SEM to test the conceptual model and answer the distinct research hypotheses.

5. Results

5.1. Preliminary analyses

Before probing the study questions, this article initially implemented preliminary analyses to get descriptive statistics on the users and usage of WeChat among the survey sample. Descriptive analyses revealed that, among the 566 respondents, 58.8% of them were females. The age of the respondents ranged from 18 to 32 years old, with the majority of them (75.9%) aged between 18 and 23 years (SD = 0.87). Generally, the demographic information of participants in the current study is consistent with that of WeChat users in mainland China, of which the majority users are younger generation (Gong et al., 2020, Pang, 2021b). Regarding educational background, the respondents were well-educated: 54.9% had a bachelor degree and 37.8% had a graduate degree. In addition, roughly 74.2% of the participants spent more than three hours on WeChat per day and 77.9% of them have used WeChat for more than five years. Table 1 illustrates the summary of demographic statistics of participants.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of participants (N = 566).

| Items | Category | Distribution | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 233 | 41.2 |

| Female | 333 | 58.8 | |

| Age | 18–20 years old | 118 | 20.8 |

| 21–23 years old | 312 | 55.1 | |

| 24–26 years old | 85 | 15.0 | |

| 27–29 years old | 44 | 7.8 | |

| 30–32 years old | 7 | 1.2 | |

| Educationa level | High school or below | 24 | 4.2 |

| Undergraduate degree students 228 55.9 | 311 | 54.9 | |

| Postgraduate degree | 213 | 37.6 | |

| Doctoral degree | 18 | 3.2 | |

| WeChat using experience | <1 year | 4 | 0.7 |

| 1–2 years | 11 | 1.9 | |

| 3–4 years | 110 | 19.4 | |

| Above 5 years | 441 | 77.9 | |

| WeChat use per day | <1 h | 47 | 8.3 |

| 1–2 h | 97 | 17.1 | |

| 3–4 h | 158 | 27.9 | |

| Above 5 h | 264 | 46.6 |

5.2. Intercorrelations among key constructs

As displayed in Table 2 , participants’ compulsive WeChat use is positively correlated with their social media fatigue (r = 0.099, p < 0.05). The results imply individuals who mainly used WeChat compulsively tended to experience more social media fatigue. Likewise, social media fatigue is a significant predictor of emotional stress (r = 0.357, p < 0.01) and social anxiety (r = 0.686, p < 0.01). This denotes that young people who experienced greater social media fatigue reported more perceived emotional distress and social anxiety about the COVID-19 pandemic. Additionally, information overload is positively related to social media fatigue (r = 0.596, p < 0.01).

Table 2.

Zero-order correlations among main variables (N = 566).

| Main variables | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Compulsive WeChat use | 1 | ||||

| 2. Information overload | 0.176** | 1 | |||

| 3. Social media fatigue | 0.099* | 0.596** | 1 | ||

| 4. Emotional stress | 0.262** | 0.462** | 0.357** | 1 | |

| 5. Social anxiety | 0.327** | 0.419** | 0.686** | 0.377** | 1 |

Note. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01.

5.3. Structural model assessment

In order to examine the structural model and corresponding hypotheses, structural equation modelling (SEM) was implemented. The study selected SEM for its ability to simultaneously assess both model parameters and structural path coefficients while controlling for other relevant variables (McCright et al., 2013). This path model generated a very good fit to the data (X2/df = 0.804 with p = 0.37 and df = 1, RMSEA = 0.003, CFI = 1.000, AGFI = 0.991, IFI = 0.999; TLI = 1.002). Information overload (b = 0.583, p < 0.001) is discovered to have a significant and positive influence on social media fatigue indicating it is the important predictor of social media fatigue. Thus, hypothesis 2 is statistically verified. Social media fatigue significantly influence emotional stress (b = 0.791, p < 0.001) and social anxiety (b = 0.686, p < 0.001). Thus, hypotheses 3 and 4 are statistically supported. Unexpected, compulsive WeChat use is not positively linked with social media fatigue (b = 0.049, p > 0.05). Accordingly, H1 is refused. Fig. 2 indicates the outcomes of hypotheses testing and path coefficients. Furthermore, this research also examines how social media fatigue could mediate the association between information overload and related psychological outcomes. More specifically, the effect of information overload on emotional stress becomes not significant when social media fatigue (mediating variable) is added to the analysis. These findings confirm that social media fatigue exerts a mediating effect on the association between information overload and emotional stress. Similarity, when the linkages between social media fatigue and social anxiety were considered, the association between information overload and social anxiety became insignificant. This significance testing result also verifies that social media fatigue could play a mediating role in the relationship between information overload and social anxiety.

Fig. 2.

The structural model test results Notes: *** p < 0.001.

6. Discussion

6.1. Summary of the key results

Building on previous literature on social media and the stressor-strain-outcome (SSO) framework, this article strives to unpack the mechanism of the effects of compulsive WeChat use and information overload on young people’s social media fatigue, emotional distress and social anxiety during the global coronavirus pandemic. More specifically, this paper explored a theoretical model and emphasized the mediating role of social media fatigue in the association between the COVID-19 information overload and psychological outcomes. The research results have validated that the conceptual model has an excellent explanatory power in predicting youth adults’ psychological state.

First, the research study presents new outcomes on the influence of perceived information overload on social media fatigue. As anticipated, obtained results suggest that information overload directly impacts individuals’ social media fatigue. The result is consistent with prior empirical studies on social media use that claims perception of COVID-19 information overload on computer-mediated communication services would lead to social media fatigue and exhaustion (Fu et al., 2020, Liu et al., 2021a, Liu et al., 2021b). In the epidemic period, young people encountered massive amount of pandemic information on WeChat, such information overload might exceed their processing capabilities and trigger psychological discomfort. This is again in line with previous studies and underlines the adverse consequences of pandemic information overload on individuals’ mental health during a global public health crisis (Ngien and Jiang, 2021, Whelan et al., 2020, Zhang et al., 2016). Contrary to the anticipation, compulsive use of WeChat is not positively related to social media fatigue. It should be noted that compulsive WeChat use is not a vital predictor of social media fatigue among young people. The reason may be that compulsive use behaviour on WeChat may involve various social and psychological activities which probably needs complex cognitive processing and which will not directly result in mental exhaustion or fatigue (Benson et al., 2019).

Second, the findings demonstrate that social media fatigue is positively associated with young people’s emotional stress. Consistent with previous literature, technical adoption could generate cognitive pressure, mental stress or costs for individuals, which would enhance relevant psychological risks (Ngien and Jiang, 2021, Pang, 2021b, Zhang et al., 2020a, Zhang et al., 2020b). Moreover, the psychological consequences of social media fatigue could be mental health problems for younger person (Pate et al., 2017, Zhang et al., 2020a, Zhang et al., 2020b). Furthermore, in order to deal with perceived emotional stress, users tend to involve in SNS activities, which subsequently lead to depletion of psychological strength and, thereby, render them susceptible to mental ill-being, such as emotional stress and exhaustion (Primack et al., 2017, Swar et al., 2017, Teng et al., 2021). Thus, in light of the results of prior literature and the current research findings, it seems that feelings of fatigue might act as a significant predictor for emotional stress in the WeChat context. The obtained findings provide evidence for the emerging phenomenon of “feature exhaustion” in the digital age (Whelan et al., 2020).

Third, social media fatigue is also discovered to associate with young people’s sense of social anxiety. In other words, social media fatigue may result in elevation of social anxiety degree among WeChat users. The result is consistent with prior studies, which notes that, on experiencing social media fatigue, young people tend to undergo decrease in cognitive abilities and feel of social anxious (Ngien and Jiang, 2021, Teng et al., 2021). Furthermore, based on the mediation analysis, social media fatigue may play a mediating role in the negative influence of information overload on young people’s social anxiety and emotional distress. This results again strengthens the mediating role of psychological strain between stressors and negative consequences (Liu et al., 2021a, Liu et al., 2021b, Whelan et al., 2020).

6.2. Theoretical and practical implications

The findings of this current article have several important theoretical implications. First, despite prior studies have revealed that the COVID-19 pandemic outbreak result in individual’s mental health (Islam et al., 2020, Liu et al., 2021a, Liu et al., 2021b), the underlying mechanisms among compulsive WeChat use, pandemic related information overload, social media fatigue and of related adverse psychological well-being have not been sufficiently probed. Therefore, the current research is probably the initial empirical work that has investigated them, thereby significantly contributing to theory advancement and building the body of knowledge in this emerging research field. Second, the present study demonstrates the mediating role of social media fatigue in the negative influences of information overload on emotional distress and social anxiety. Although previous studies have investigated how information overload, communication overload, and SNS use influence social media fatigue (Dhir et al., 2018, Fox and Moreland, 2015, Whelan et al., 2020), it remains unclear whether social media fatigue would influence young adults’ mental health in mainland China. Therefore, the article may contribute to social media fatigue literature by demonstrating its mediating role in the association between information overload and negative psychological consequences during a global health emergencies. Third, informed by the stressor–strain–outcome framework (Apaolaza et al., 2019, Zhang et al., 2021), the study designed a conceptual research model uncovering how two types of stressors, especially information overload and WeChat compulsive use could trigger individuals’ psychological states during the ongoing public health crisis. On the basis of existing research, the article paper proposes a new analytical perspective, which makes contribution to the literature by enriching the line of the research on WeChat user behavior and mental health.

Practically, the results can provide vital inspirations for social media users, service providers, and managers. First, service providers need comprehensive that information overload may affect social media fatigue in the WeChat setting. Ultimately, it becomes significant for service designers and managers to intentionly devise and design characteristics and functional services which would reduce social media fatigue and discomfort to users (Fu et al., 2020, Zhang et al., 2020a, Zhang et al., 2020b). Moreover, service providers should check the released excessive information from the source to control the quantity and quality of the information. Second, according to obtained outcomes of this article, social media fatigue exert significant impact on psychological well-being, i.e., it could lead to emotional stress and social anxiety. As such, some strategies might include optimizing the system functions to alleviate the risk possibilities of young adults’ encountering psychological problems and satisfaction concerns in today’s digital media age (Fu et al., 2020, Pang, 2021b, Yang and Jansz, 2021). Third, the study model may be a guide for more researchers and academics who are interested in further exploring various dimensions of social media fatigue by utilizing additional exploratory factors.

6.3. Limitations and suggestions for future research

This present work also has several important research limitations. First, all participants were recruited from one certain country, which was a unique setting with its cultural backgrounds, and hence, scholars should to be cautious not to overgeneralize the current findings to other age groups. To address such limitation, this, future studies could investigate a similar conceptual model with a broader diversity of samples. Second, the current study merely concentrated on one certain domestic social media service in mainland China, i.e., WeChat. Ultimately, there is a necessary for scholars to verify results of this work in the setting of other popular services, including Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and YouTube. Third, the study used self-reported data which would have been subject to social desirability and recall methodological biases. Therefore, following studies could incorporate other study methodologies, such as in depth interview and observation, and probe another antecedents and outcomes of social media fatigue.

7. Conclusion

The present article has investigated the association between social media fatigue and mental health by using diverse factors, namely compulsive WeChat usage, information overload, social anxiety, and emotional stress during the pandemic, which have not been considered together in prior literature. Using the SSO framework, these findings provide unique and original evidence suggesting that information overload on WeChat could actually trigger social media fatigue behavior while the impact of compulsive use was not significant. Additionally, the results also confirm that individuals’ perceived social media fatigue could result in emotional stress and social anxiety. The findings are beneficial not only for comprehending the psychological mechanism associated with younger generations’ WeChat use during epidemic period, but also offer valuable insights for researchers and practitioners to further explore more detrimental possibilities related to social media fatigue in the digitally connected world.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgement

This work was supported by the National Social Science Fund of China (Grant No. 19CXW035).

References

- Akbay S.E. Smartphone addiction, fear of missing out, and perceived competence as predictors of social media addiction of adolescents. Eur. J. Educ. Res. 2019;8(2):559–566. [Google Scholar]

- Alabdulkareem S.A. Exploring the use and the impacts of social media on teaching and learning science in saudi. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015;182:213–224. [Google Scholar]

- Alkis Y., Kadirhan Z., Sat M. Development and validation of social anxiety scale for social media users. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2017;72:296–303. [Google Scholar]

- Andreassen C.S., Torsheim T., Brunborg G.S., Pallesen S. Development of a facebook addiction scale. Psychol. Rep. 2012;110(2):501–517. doi: 10.2466/02.09.18.PR0.110.2.501-517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Apaolaza V., Hartmann P., D'Souza C., Gilsanz A. Mindfulness, compulsive mobile social media use, and derived stress: The mediating roles of self-esteem and social anxiety. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Network. 2019;22(6):388–396. doi: 10.1089/cyber.2018.0681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ares G., Bove I., Vidal L., Brunet G., Fuletti D., Arroyo Á., Blanc M.V. The experience of social distancing for families with children and adolescents during the coronavirus (covid-19) pandemic in uruguay: Difficulties and opportunities. Children and Youth Services Review. 2021;121:105906. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.105906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker D.A., Algorta G.P. The relationship between online social networking and depression: A systematic review of quantitative studies. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Network. 2016;19(11):638–648. doi: 10.1089/cyber.2016.0206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benson V., Hand C., Hartshorne R. How compulsive use of social media affects performance: Insights from the uk by purpose of use. Behav. Inform. Technol. 2019;38(6):549–563. [Google Scholar]

- Brand M., Young K.S., Laier C., Wölfling K., Potenza M.N. Integrating psychological and neurobiological considerations regarding the development and maintenance of specific internet-use disorders: An interaction of person-affect-cognition-execution (i-pace) model. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2016;71:252–266. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2016.08.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen W., Lee K.-H. Sharing, liking, commenting, and distressed? The pathway between facebook interaction and psychological distress. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Network. 2013;16(10):728–734. doi: 10.1089/cyber.2012.0272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chow T.S., Wan H.Y. Is there any ‘facebook depression’? Exploring the moderating roles of neuroticism, facebook social comparison and envy. Personality Individ. Differ. 2017;119:277–282. [Google Scholar]

- Dhir A., Yossatorn Y., Kaur P., Chen S. Online social media fatigue and psychological wellbeing—a study of compulsive use, fear of missing out, fatigue, anxiety and depression. Int. J. Inf. Manage. 2018;40:141–152. [Google Scholar]

- Fabris M.A., Marengo D., Longobardi C., Settanni M. Investigating the links between fear of missing out, social media addiction, and emotional symptoms in adolescence: The role of stress associated with neglect and negative reactions on social media. Addict. Behav. 2020;106:106364. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2020.106364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox J., Moreland J.J. The dark side of social networking sites: An exploration of the relational and psychological stressors associated with facebook use and affordances. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2015;45:168–176. [Google Scholar]

- Fu S., Li H., Liu Y., Pirkkalainen H., Salo M. Social media overload, exhaustion, and use discontinuance: Examining the effects of information overload, system feature overload, and social overload. Inf. Process. Manage. 2020;57(6):102307. doi: 10.1016/j.ipm.2020.102307. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gámez-Guadix M., Villa-George F.I., Calvete E. Measurement and analysis of the cognitive-behavioral model of generalized problematic internet use among mexican adolescents. Journal of adolescence. 2012;35(6):1581–1591. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2012.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong M., Yu L., Luqman A. Understanding the formation mechanism of mobile social networking site addiction: Evidence from wechat users. Behav. Inform. Technol. 2020;39(11):1176–1191. [Google Scholar]

- Grieve R., Indian M., Witteveen K., Anne Tolan G., Marrington J. Face-to-face or facebook: Can social connectedness be derived online? Comput. Hum. Behav. 2013;29(3):604–609. [Google Scholar]

- Guo Y., Lu Z., Kuang H., Wang C. Information avoidance behavior on social network sites: Information irrelevance, overload, and the moderating role of time pressure. Int. J. Inf. Manage. 2020;52:102067. doi: 10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2020.102067. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hu X., Kim A., Siwek N., Wilder D. The facebook paradox: Effects of facebooking on individuals’ social relationships and psychological well-being. Front. Psychol. 2017;8:1–8. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Islam A.K.M.N., Laato S., Talukder S., Sutinen E. Misinformation sharing and social media fatigue during covid-19: An affordance and cognitive load perspective. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2020;159:120201. doi: 10.1016/j.techfore.2020.120201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keles B., McCrae N., Grealish A. A systematic review: The influence of social media on depression, anxiety and psychological distress in adolescents. Int. J. Adolescence Youth. 2020;25(1):79–93. [Google Scholar]

- Klobas J.E., McGill T.J., Moghavvemi S., Paramanathan T. Compulsive youtube usage: A comparison of use motivation and personality effects. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2018;87:129–139. [Google Scholar]

- Langston M. The california state university e-book pilot project: Implications for cooperative collection development. Library Collections Acquisitions Technical Services. 2003;27:19–32. [Google Scholar]

- Levy B., Stephansky M.R., Dobie K.C., Monzani B.A., Medina A.M., Weiss R.D. The duration of inpatient admission predicts cognitive functioning at discharge in patients with bipolar disorder. Compr. Psychiatry. 2009;50(4):322–326. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2008.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X., Chan M. Smartphone uses and emotional and psychological well-being in china: The attenuating role of perceived information overload. Behav. Inform. Technol. 2021:1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Lin S., Liu D., Liu W., Hui Q.i., Cortina K.S., You X. Mediating effects of self-concept clarity on the relationship between passive social network sites use and subjective well-being. Curr. Psychol. 2021;40(3):1348–1355. [Google Scholar]

- Liu H., Liu W., Yoganathan V., Osburg V.-S. Covid-19 information overload and generation z’s social media discontinuance intention during the pandemic lockdown. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2021;166:120600. doi: 10.1016/j.techfore.2021.120600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu W., Xu W.(., John B. Organizational disaster communication ecology: Examining interagency coordination on social media during the onset of the covid-19 pandemic. Am. Behav. Scientist. 2021;65(7):914–933. [Google Scholar]

- Maier C., Laumer S., Weinert C., Weitzel T. The effects of technostress and switching stress on discontinued use of social networking services: A study of facebook use. Inform. Syst. J. 2015;25:275–308. [Google Scholar]

- A. Malik A. Dhir P. Kaur A. Johri Correlates of social media fatigue and academic performance decrement Information Technology & People 34 2 2020 2021 557 580.

- Mamun M.A., Sakib N., Gozal D., Bhuiyan AKM.I., Hossain S., Bodrud-Doza M.d., Al Mamun F., Hosen I., Safiq M.B., Abdullah A.H., Sarker M.A., Rayhan I., Sikder M.T., Muhit M., Lin C.-Y., Griffiths M.D., Pakpour A.H. The covid-19 pandemic and serious psychological consequences in bangladesh: A population-based nationwide study. J. Affect. Disord. 2021;279:462–472. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.10.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCright A.M., Dunlap R.E., Xiao C. Perceived scientific agreement and support for government action on climate change in the USA. Clim. Change. 2013;119(2):511–518. [Google Scholar]

- Munzel A., Galan J.-P., Meyer-Waarden L. Getting by or getting ahead on social networking sites? The role of social capital in happiness and well-being. Int. J. Electr. Commerce. 2018;22(2):232–257. [Google Scholar]

- Nabity-Grover, T., Cheung, C. M. K., & Thatcher, J. B., 2020. Inside out and outside in: How the covid-19 pandemic affects self-disclosure on social media. International Journal of Information Management 55, 102188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Ngien A., Jiang S. The effect of social media on stress among young adults during covid-19 pandemic: Taking into account fatalism and social media exhaustion. Health Commun. 2021:1–8. doi: 10.1080/10410236.2021.1888438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ophir Y. Sos on sns: Adolescent distress on social network sites. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2017;68:51–55. [Google Scholar]

- Panayiotou G., Leonidou C., Constantinou E., Michaelides M.P. Self-awareness in alexithymia and associations with social anxiety. Curr. Psychol. 2020;39(5):1600–1609. [Google Scholar]

- Pang H. How does time spent on wechat bolster subjective well-being through social integration and social capital? Telemat. Inform. 2018;35(8):2147–2156. [Google Scholar]

- Pang H. How can wechat contribute to psychosocial benefits? Unpacking mechanisms underlying network size, social capital and life satisfaction among sojourners. Online Inform. Rev. 2019;43(7):1362–1378. [Google Scholar]

- Pang H. Identifying associations between mobile social media users’ perceived values, attitude, satisfaction, and ewom engagement: The moderating role of affective factors. Telemat. Inform. 2021;59:101561. doi: 10.1016/j.tele.2020.101561. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pang H. Unraveling the influence of passive and active wechat interactions on upward social comparison and negative psychological consequences among university students. Telemat. Inform. 2021;57:101510. doi: 10.1016/j.tele.2020.101510. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- H. Pang Examining associations between university students' mobile social media use, online self-presentation, social support and sense of belonging Aslib Journal of Information Management 72 3 2020 2020 321 338.

- Pate C.M., Maras M.A., Whitney S.D., Bradshaw C.P. Exploring psychosocial mechanisms and interactions: Links between adolescent emotional distress, school connectedness, and educational achievement. School Mental Health. 2017;9(1):28–43. doi: 10.1007/s12310-016-9202-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pennington R., Tuttle B. The effects of information overload on software project risk assessment. Decision Sci. 2007;38(3):489–526. [Google Scholar]

- Pontes H.M. Investigating the differential effects of social networking site addiction and internet gaming disorder on psychological health. J. Behav. Addict. 2017;6(4):601–610. doi: 10.1556/2006.6.2017.075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Primack B.A., Shensa A., Escobar-Viera C.G., Barrett E.L., Sidani J.E., Colditz J.B., James A.E. Use of multiple social media platforms and symptoms of depression and anxiety: A nationally-representative study among us young adults. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2017;69:1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Shaw A.M., Timpano K.R., Tran T.B., Joormann J. Correlates of facebook usage patterns: The relationship between passive facebook use, social anxiety symptoms, and brooding. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2015;48:575–580. [Google Scholar]

- Soroya S.H., Farooq A., Mahmood K., Isoaho J., Zara S.-e. From information seeking to information avoidance: Understanding the health information behavior during a global health crisis. Inf. Process. Manage. 2021;58(2):102440. doi: 10.1016/j.ipm.2020.102440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steimer T. The biology of fear-and anxiety-related behaviors. Dialogues Clin. Neurosci. 2002;4:231–249. doi: 10.31887/DCNS.2002.4.3/tsteimer. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swar B., Hameed T., Reychav I. Information overload, psychological ill-being, and behavioral intention to continue online healthcare information search. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2017;70:416–425. [Google Scholar]

- Teng L., Liu D., Luo J. Explicating user negative behavior toward social media: An exploratory examination based on stressor–strain–outcome model. Cogn. Technol. Work. 2021:1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Tian Q. Social anxiety, motivation, self-disclosure, and computer-mediated friendship: A path analysis of the social interaction in the blogosphere. Commun. Res. 2013;40(2):237–260. [Google Scholar]

- E. Whelan A.K.M. Najmul Islam S. Brooks Is boredom proneness related to social media overload and fatigue? A stress–strain–outcome approach Internet Research 30 3 2020 2020 869 887.

- Wiernik E., Lemogne C., Thomas F., Perier M.-C., Guibout C., Nabi H., Laurent S., Pannier B., Boutouyrie P., Jouven X., Empana J.-P. Perceived stress, common carotid intima media thickness and occupational status: The paris prospective study iii. Int. J. Cardiol. 2016;221:1025–1030. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2016.07.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wijesuriya N., Tran Y., Craig A. The psychophysiological determinants of fatigue. Int. J. Psychophysiol. 2007;63(1):77–86. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2006.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie X., Wang X., Zhao F., Lei L.i., Niu G., Wang P. Online real-self presentation and depression among chinese teens: Mediating role of social support and moderating role of dispositional optimism. Child Indicat. Res. 2018;11(5):1531–1544. [Google Scholar]

- Yang C.-C., Carter M.D.K., Webb J.J., Holden S.M. Developmentally salient psychosocial characteristics, rumination, and compulsive social media use during the transition to college. Addict. Res. Theory. 2020;28(5):433–442. [Google Scholar]

- Yang L., Jansz J. Health information related to cardiovascular diseases broadcast on chinese television health programs. Healthcare. 2021;9(7):802. doi: 10.3390/healthcare9070802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang L., Mao Y., Jansz J. Chinese urban hui muslims’ access to and evaluation of cardiovascular diseases-related health information from different sources. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2018;15(9):2021. doi: 10.3390/ijerph15092021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang L., Mao Y., Jansz J. Understanding the chinese hui ethnic minority’s information seeking on cardiovascular diseases: A focus group study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2019;16(15):2784. doi: 10.3390/ijerph16152784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y., He W., Peng L. How perceived pressure affects users' social media fatigue behavior: A case on wechat. J. Comput. Inform. Syst. 2020:1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y., Liu Y., Li W., Peng L., Yuan C. A study of the influencing factors of mobile social media fatigue behavior based on the grounded theory. Inform. Discov. Deliv. 2020;48(2):91–102. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z., Zhang L.i., Xiao H., Zheng J. Information quality, media richness, and negative coping: A daily research during the covid-19 pandemic. Personality Individ. Differ. 2021;176:110774. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2021.110774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang S., Zhao L., Lu Y., Yang J. Do you get tired of socializing? An empirical explanation of discontinuous usage behaviour in social network services. Inform. Manage. 2016;53(7):904–914. [Google Scholar]

- Zhong B.u., Huang Y., Liu Q. Mental health toll from the coronavirus: Social media usage reveals wuhan residents’ depression and secondary trauma in the covid-19 outbreak. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2021;114:106524. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2020.106524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]